1. Introduction

In November 1880, John William Colenso, the first Bishop of Natal, travelled with his daughter Harriette to ‘the Castle’, a colonial fortification in Cape Town, South Africa, where the Zulu king, Cetshwayo

1, was imprisoned after his defeat during Anglo–Zulu War of 1879.

We … went to the “Castle”, a large stone building surrounded by ramparts within the city boundaries …. [and were led] up and down stone staircases past a sentinel, and through a stone passage… [We then entered a room with] three bare old wooden chairs in the further corner, on one of which sat the King in European clothing, waiting for us and eagerly looking at the door. He rose to welcome us, and clasped the Bishop’s hand as if he could not let it go.

The demonstrative greeting between the two men was pivotal in affirming the relationship between the family of Bishop Colenso and the family of Cetswayo. The handshake was important because it was a demonstration of solidarity and equality between two figures, each a leader or prominent figure in their respective communities, which, though adjacent to one another, were grossly unequal in power. The kingdom of Zululand was situated in Southern Africa, a region in which black populations had been intruded upon by white settlers. As in many other non-European areas of the globe, white settlers were established in enclaves which, if formalised as British Crown colonies, enjoyed the backing of the power and resources of the British Empire. The imbalance of power between the British colonists in Natal and the Zulu nation, economically, politically and, as it would turn out, militarily, was starkly symbolised by the stone walls and ramparts of the castle in Cape Town in which Cetshwayo was imprisoned.

Two years later, in 1882, Cetshwayo was to travel to England, where he was granted an audience with Queen Victoria. Just as Cetshwayo considered himself to be in a reciprocal and equal relationship with Bishop Colenso, so too was this reception of the Zulu King by the queen seen by him as a recognition of his close and special relationship with the queen. The occasion was seen by subsequent generations of Zulu as evidence of the continuing and meaningful relationship between the British and Zulu royal families.

Using primary sources, including letters, photographs, and colonial records, as well as secondary accounts, this study explores the relationship between the Colenso family and the Zulu royal family and the part played by the Colenso family in the struggle to defend Zulu sovereignty in the face of a colonial government intent on undermining the integrity of the Zulu nation by diminishing the authority of the Zulu King.

Cetshwayo had succeeded to the position as Zulu King in 1872 after the death of his father, Mpande, the former Zulu King and a brother of Shaka, the founder of the Zulu nation. Members of the families of Colenso and Cetshwayo came to consider themselves to be related by kinship. These relations, mutually acknowledged by the reciprocal use of kinship terms, were intertwined with, and overlaid by, a network of political relations which, this article will argue, amounted to an alliance between the two families, an alliance which was to endure for three generations of the Zulu royal family. After Bishop Colenso died in 1883, the leadership of the Colenso family in Natal devolved to his eldest daughter, Harriette, who, with the help of her siblings and their mother, was to continue her father’s campaigning work. She was also to use her kinship position within the Zulu royal family to endorse and facilitate the Zulu royal family’s claim to parity with the British royal family. And, although she was to become a persona non grata among the officials in Natal, in Britain, her status as a white person in colonial society was to gain her limited access to the corridors of power through sympathetic ministers and officials.

The claim by the Zulu royal family to be recognised by the British royal family as equals was underpinned by the weight attributed to the principle of heredity. This principle was held to be of paramount importance by the Zulu royal family and was recognised by them as the means of determining succession to legitimate power, as it was by the British royal family. The principle was deployed by Harriette, who was to emphasise it in demonstrating the endurance of the Zulu royal family over generations in her endeavour to help rescue the Zulu kingship from the destruction wished upon it by the colonial authorities. It was, therefore, a theme underlying her relationship with the Zulu royal family and her choice of campaigning tactics employed in their defence.

2. The Colenso Family’s Missionary Beginnings

In 1843, the territory situated on the southeastern seaboard of Africa, later to be named Natal, was proclaimed a British Colony through the annexation of the short-lived Boer Republic of Natalia. To the northeast, the new colony was bounded by the independent black kingdom of Zululand and to the southeast by the then uncolonized territory known as Kaffraria, beyond which was Cape Colony, first established several decades earlier in 1795. At the time of its inception, therefore, Natal was a relatively new colony in the region, distinguished from its older neighbour by being much smaller and by having a far greater proportion of Black Africans than the Cape Colony. Bishop Colenso was later to describe its size as “one third of the extent of England and Wales with a population of 6000 Europeans and 100,000 natives”. He describes its African population as “commonly called by the general name of Zulus” (

J. W. Colenso [1982] 1854, p. 1). The Colony’s first Lt. Governor was appointed in 1845 (

Guy 1983, p. 38).

The annexation of Natal presented an opportunity for Bishop Robert Gray, the Bishop of Cape Town, to sub-divide his diocese and elevate his status to that of “Metropolitan”, with authority over the newly created diocese of Natal, along with that of Grahamstown, resulting from the expansion of Cape Colony itself. In 1852, Gray returned to Britain, partly in order to recruit bishops for these new dioceses. At that time, the reverend John William Colenso was rector of a country parish in Norfolk. He took a strong interest in missionary work overseas, acting as the local organising secretary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Overseas (SPG), whose secretary was godfather to his eldest son, and editing the Society’s two principal journals:

The Church in the Colonies and

The Monthly Record (

Rees 1958, p. 33;

Hinchliff 1964, p. 50). Bishop Gray heard of Colenso and his interest in missionary work and invited him to take up the position in the new diocese. Colenso accepted, and he was consecrated in 1853 as the first Bishop of Natal (

Hinchliff 1964, pp. 50, 51;

Rees 1958, pp. 29–32). After a brief sojourn to the colony in 1854 (

J. W. Colenso 1855), in 1855, Colenso went to Natal to establish himself there with his wife and their four children: their two daughters, Harriette and Frances, and their two sons, Francis (later known as Frank) and Robert. Their third daughter, Agnes, was born in Natal in 1855. The children grew up alongside Zulu children at the mission station and learned the Zulu language from an early age.

Colenso saw missionary work among the Zulu as his priority and did not want this work to be confined within the borders of the Natal diocese. Instead, he wanted to see his mission include those “within and on the borders of the diocese” (

J. W. Colenso [1982] 1854, p. 1). However, it is likely that what he intended his missionary work to include was not just those “on” the borders, but to those beyond the borders. He wanted to distance himself from the centre of white settler society in Natal. He, therefore, chose a location a few miles outside the colony’s capital, Pietermaritzburg, to establish a homestead for himself and his family, a mission station, and a mission school. The homestead was called Bishopstowe. The mission school established later was called Ekukanyeni (“Place of Light’”) (

Rees 1958, pp. 39–41;

Cox 1888, pp. 76–80;

Guy 1983, pp. 62–64). Bishop Colenso was given the Zulu name, Sobantu, meaning “father of the people”. In Colenso’s own account, this was one of two names which, “according to the usual practice, they have given to the Bishop, to sufficiently indicate what they expect of him and show a very just appreciation of his office. These are,

Sokululeka, “Father of the raising-up”, and

Sobantu, “Father of the people”. The names are entirely of their own invention, and constructed out of notions which they have formed of the bishop’s duties from what they are told about them” (

J. W. Colenso [1982] 1854, p. 6). Of these two names, it was “Sobantu” which took hold.

From the time of his arrival in Natal, Colenso established close and cooperative working relations with the Natal authorities, especially with the Secretary for Native Affairs, Theophilus Shepstone, who had proved helpful to the bishop by introducing him to prominent Natal chiefs and in recruiting Zulu children as pupils for his mission school (

Guy 1983, p. 64). The working partnership between Shepstone and Colenso was to continue for twenty years until it broke down as a result of what Colenso considered to be the miscarriage of justice in the trial, by the Natal government, of the Natal Zulu chief, Langalibalele. In the bishop’s view, the way in which the trial was conducted revealed the underhanded methods used by Shepstone to control the African population of Natal. The bishop broke off relations with Shepstone and was to become the colony’s foremost critic of the Natal government’s policy towards the Zulu populations of Natal and, subsequently, of Zululand.

3Bishop Colenso began seriously campaigning in defence of the Zulu people from the mid-1870s, deploying his whole family as a campaigning resource. By then, his five children were in their twenties. His two sons, Frank and Robert, had moved to live in England to pursue their careers there, while his eldest and youngest daughters, Harriette and Agnes, remained in Natal with their parents. The bishop’s second daughter, Frances, divided her time between Natal and England until her death from tuberculosis in 1887 at the tragically young age of 37 (

Merrett 1980, p. 58).

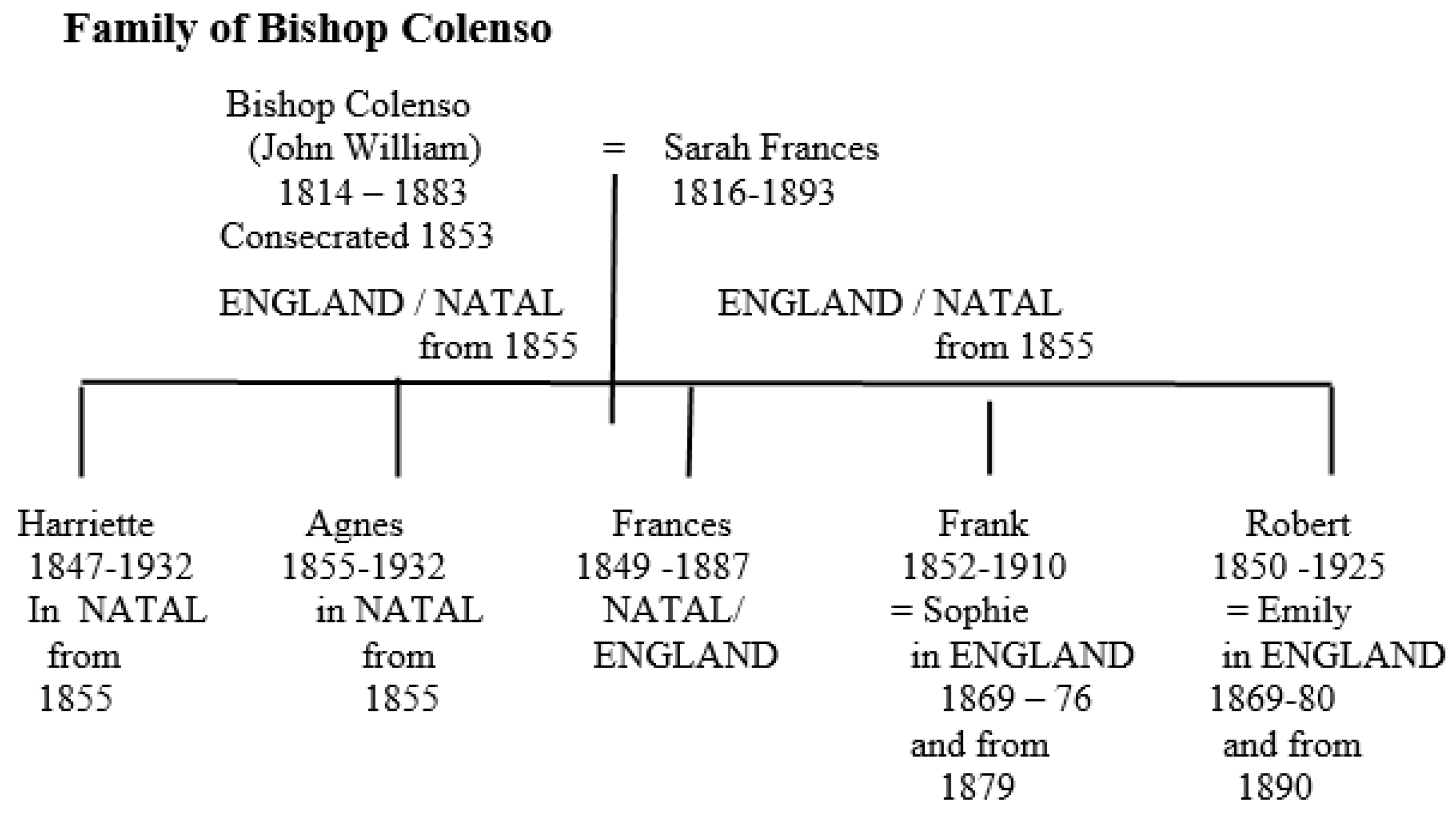

Figure 1 indicates the primary country of residence of the bishop and his wife after their move to Natal in 1855, and of their children in their adult lives. The whole family moved to live in England in 1862 and remained there until 1865, when they returned to Natal.

The geographical separation of family members was a crucial factor in relation to the tactics employed by the Colenso family in their campaigning work, and it was something that Bishop Colenso made use of from the start in operating “an extensive chain of influence” from Zululand to Britain.

4 This comprised collecting information from contacts or informants in Zululand and transmitting this information to his sons or other contacts in England for use to be made of it to bring pressure to bear on the Colonial Office, or to influence public opinion. In England, apart from his sons, another major contact of the bishop’s was Frederick Chesson, Secretary of the Aborigines’ Protection Society (APS).

In Natal, Harriette and Agnes provided support for their father’s campaigning work in a variety of ways, including the preparation of newspaper cuttings or other material to be sent to England and by copying out letters sent by the bishop to the Natal governor or government officials, copies of which were to be sent enclosed with the bishop’s covering letters to England. But his daughters did not only act as secretaries and scribes for the bishop. When he wrote to the APS on a particular issue, for example, Harriette might send a parallel letter to Frank asking him to take up the issue in England by writing to the papers or liaising with Chesson on the matter. But Bishop Colenso would check the letters from Harriette and confirm his approval before they were sent, with the aim of ensuring that the family maintained a united front on every issue they took a stand on. This appeared to Bishop Colenso to be crucial, as once engaged in campaigning for the cause of the Zulu people, the family came under enormous pressure and was vulnerable to severe criticism from a largely hostile press in Natal and from a settler community who saw the Colenso family as potentially undermining their prospects, which hinged on maintaining the dominance of the colonists in Natal over the Zulu population of the colony and, later, of Zululand (

G. Colenso 2011, pp. 3–8).

During the bishop’s lifetime, the key relationship in regard to the family’s campaigning work was that between the bishop and his eldest daughter, Harriette, whose Zulu name was Udlwedlwe, meaning “her father’s staff and guide” (

Guy 2002, p. 63). She acted both as his secretary and his interpreter, her fluency with Zulu being greater than his (

Merrett 1980, p. 261).

Matters came to a head with the invasion of Zululand in January 1879 by British and colonial forces, which suffered a catastrophic defeat in the battle of Isandlwana, after which Colenso preached a sermon in the cathedral in Pietermaritzburg. In the sermon, he was expected by the settler congregation to mourn the loss of life of colonists in the disastrous battle. Instead, he mourned the loss of life among both Zulu and British and colonial soldiers, condemned the invasion, and warned against a further invasion (

J. W. Colenso 1879). But the bishop’s admonition was ignored, and Zululand was invaded for the second time in July of the same year at the cost of great loss of life among the Zulu defenders.

Following the defeat of the Zulu army and the capture and imprisonment of Cetshwayo, a destructive postwar settlement was imposed on Zululand by the newly appointed High Commissioner for South East Africa, Sir Garnet Wolseley. The country was divided into thirteen “chiefdoms”, each under the authority of a chief appointed by Wolseley in consultation with Natal officials but in disregard of many Zulu of great standing under the old Zulu order (

Guy 1994, chps. 5 and 6, pp. 69–97). With the support of his adult daughters in Natal and his two sons, by then in England, Bishop Colenso mounted a sustained critique of colonial and imperial policy in regard to Zululand. Bishopstowe became a symbol and centre of opposition to the approach adopted by the Natal government to control the Zulu population (

Guy 1994, pp. 98–101;

Rees 1958, p. 399).

After the death of the bishop in 1883, the relationship that there had been between him and Harriette came to be replicated by the relationship between Harriette and her younger sister, Agnes, who acted as her elder sister’s assistant, providing her support as Harriette had done for her father, the two having an almost mother–daughter relationship. Writing to Agnes when they were separated (as for example in the 1890s, when Harriette was in England and Agnes in Natal—see below), Harriette invariably began her letters, “My darling child” or “My own child” (Archive reference [hereafter Arch ref] a). While Agnes was to remain in the background (

Nicholls 1997, p. 10), Harriette in effect became head of household as far as the campaigning work at Bishopstowe was concerned (

Merrett 1980, p. 261). Her main family contact in England was her brother, Frank. She took the lead in that relationship, gently but constantly pressing him to “

Go on working for the Zulu”, adding that “unless we do so humanly speaking, Papa’s work for the Natal natives as well as the Zulus is lost, wasted” (Arch ref b). She also recruited Frank’s wife, Sophie, to the cause, sometimes having little compunction in pressing her to encourage her husband in this work. Writing to both Sophie and Frank in March 1881, Harriette ended her letter appealing to Sophie to help the Zulu cause, “by Keeping Frank, and every one all around you up to the mark…” (Arch ref c).

After Frank’s death in 1910, Sophie was to continue her husband’s work on Zulu affairs. She was to become Harriette’s main contact in England, and her home near Amersham, with the Zulu name Elangeni (“where the sun shines through”), was to become a centre for Africans visiting England as members of deputations from South Africa (

G. Colenso 2013b, section IX, ‘Connecting places and people’).

3. Forging Kinship Across the Colonial Divide

Before going any further, it is important to clarify the use of the word “family” as it applies to Western and African kinship systems in the nineteenth century. Although I refer to the “family” of Cetshwayo throughout this article, I do not intend the term, when applied to Zulu kinship relations, to correspond exactly to its meaning in its common usage in the West—that is, as referring to the “nuclear family”.

In nineteenth-century Zulu society, life was based around the homestead (

imizi), which comprised the male head of the homestead and his wives, housed separately with their children. Kinship was organised around lineages (groups of kin related by descent), which were patrilineal (descent being traced through the male line). Lineages were segmented as the sons matured and married, establishing their own homesteads separately (

Guy 1994, pp. 22/23). Lineages were usually residential units, with several segments of a lineage living within one neighbourhood forming a recognised group (

Umdeni) (

Gluckman 1950, p. 169). The homestead, or royal residence, of the Zulu king was obviously greater and grander than the homesteads of commoners, and the king also benefited from various forms of tribute from his subjects. Nevertheless, similar principles applied, as in the case of commoners outlined above.

I suggest that, for the purposes of this article, the term “family” can be loosely employed to refer to Cetshwayo’s close kin. The fact that the organisation of Zulu society was according to lineages based on patrilineal descent, and the lineages, or segments within them, were grouped around residential units, provides enough of a parallel to the western concept of family to allow for close kin within Zulu lineages to be referred to as “family” members. Therefore, it can be considered that there is sufficient correspondence between groups of immediate kin in British and Zulu society for them both to be referred to as “family”.

Cetshwayo referred to Bishop Colenso as his “father” as early as 1874 when, on hearing that the bishop had gone to England to plead the case for Langalibalele, he sent a note saying, “Cetshwayo rejoices exceedingly to hear that you have gone to the great Indunas [advisors] of the Queen to tell them all the story about the treatment of black people in Natal and prays that you would fight with all your might … about the matter of Langalibalele …. In all this Cetshwayo’s heart watches over you; he has held up his finger continually that you are his father” (

Cox 1888, vol. ii, p. 453).

5As we have seen, in November 1880, Bishop Colenso and his eldest daughter, Harriette, visited the “ex King” (as Cetshwayo was now referred to by the colonial authorities) in prison in Cape Town. When asking to see him, the bishop was told that he could not do so unless he himself (the king) desired it. The bishop replied, “Cetshwayo regards me as his “father” and would joyfully welcome everyone I brought or sent to see him” (

Cox 1888, vol. II, p. 553). At the last of their several meetings with the king in Cape Town, Harriette and the bishop discussed with Cetshwayo the prospect of his travelling to England as a step towards pleading for his release from prison and return to Zululand, and for his restoration as King of Zululand. Though initially distressed at the idea that “he thought the sea would kill him”, he eventually acquiesced and, invoking his relationship to the bishop and affirming his trust in him, said “Yes, I will certainly go to England at once if I am asked, since you advise it; and there is nothing that I will not do if

my father Sobantu wishes it” [emphasis added] (

F. E. Colenso 1884, p. 67).

In 1882, Cetshwayo travelled to England in the hope of being restored as King of Zululand. But, in 1883, bitterly disappointed, he was returned to Zululand in greatly reduced circumstances. After his return to Zululand, Cetshwayo evoked his filial relationship with the bishop when describing the degradation of his position in Zululand because of the partition of the country (which I refer to below). Seeing him as a lifeline, in February and March 1883, Cetshwayo wrote to the bishop in desperation, “You alone are my father in whom I trust to help me”. In a postscript, Cetshwayo adds, “My father, here is another matter …” (Cetshwayo to Bp Colenso, 26 February 1883, quoted in Cox 1888, vol. II, p. 617). Then, later, in March 1883, continuing to report on the dire situation in Zululand, Cetshwayo wites to Bishop Colenso, “My father…” [asking him to] “inform the English govt. … Lord Kimberley … that he should inform Mr. Gladstone. I repeat that I report my distress to you, my father, in order that you may report it to these great men …” (Cetshwayo to Bp Colenso 26 March 1883 quoted in

Guy 1983, p. 340).

On 20 June 1883, Bishop Colenso died. Harriette arranged for a Zulu messenger to take a letter to Cetshwayo after viewing her father’s body. She explained in the letter to Cetshwayo that this was, “… to see, as your eyes, as you too are

Sobantu’s son. Listen well to these words of mine,

my brother, knowing that I come from him, that it is not I, but Sobantu who speaks to you saying ‘Do not despair

my son’” [emphases added] (

Guy 2002, pp. 78, 79).

I suggest that we can deduce from this letter a number of important points.

The letter reassures Cetshwayo of the continued support from the Colenso (Sobantu’s) family and, hence, has the form of a pledge of loyalty to Cetshwayo’s family. And, by referring to Cetshwayo as Sobantu’s son, and to him as her brother, Harriette reaffirms the kinship relations between members of the houses of Sobantu and Cetshwayo.

In affirming these kin relations, the statement by Harriette necessarily implies equality between the members of the two families, something that was then contrary to the norm for relations between white settlers and Africans in the colony, across the colonial divide. As was the case with all white settler colonies, Natal was a highly stratified society with a rigid demarcation between black and white, in terms of social status and economically and politically. Such division within the society would normally preclude intimate personal relations between the races, let alone the kind of relations that would normally subsist between members of the same family. The implications of there being a single family with members on both sides of the racial divide are of major significance in a society organised around the principle of a clear separation of social status, economic function, and political power between black and white people.

Harriette’s letter also worked to confirm her position as leader of the Colenso family, as she is speaking in Sobantu’s words. And it affirms, by implication, in the Colenso family, the importance of the principle of heredity in determining succession to her father’s position in the family. In this brief letter, Harriette conveys emphatically that she has inherited from her father his position as head of the house of Sobantu and his role in ministering to the Zulu people. I will suggest that this is parallel to the importance of heredity and succession in the Zulu royal family, which will be explored further below. Bishop Colenso‘s continued presence, even after his death, was evoked by Harriette when addressing Cetshwayo and other Zulu chiefs in the message referred to above: “It is not I, but Sobantu who speaks to you …” (

Guy 2002, p. 78).

Cetshwayo replied to Harriette’s letter asking “that a stone be bought in my name, which shall be set over the grave of my Father” (

Guy 1983, p. 345), and he addresses Harriette as his “sister”, thus accepting her reference to him as her “brother”. In his reply, Cetshwayo also provided a heartfelt justification for regarding Bishop Colenso as his father. He compared the effect on him of the death of Bishop Colenso to the loss of his father, Mpande. “You see the death of my Father Mpande was a great distress to me. But there remained to me Sobantu who gave me courage, and spoke for me, setting things straight. And now it is Mpande’s death over again”. Cetshwayo continues, asking Harriette to “report … our distress for the loss of

our Father” [emphasis added] (

Guy 2002, p. 79). When addressing Harriette, he refers to her and himself as sharing the same father, thus including himself in her family (or her in his family), by virtue of sharing the same father and, as her sibling, just as she refers to him as her sibling.

As well as affirming her kinship relations with the Zulu royal family, Harriette also considered herself absorbed within the Zulu people, claiming Zulu identity for herself. In March 1881, writing to her sister-in-law, she urged her, “Sophie dear … to show your sympathy for

us poor Zulus” [emphasis added] (Arch ref d). Even when writing to the Colonial Office. Harriette referred to ‘we Zulu’. In other letters of Harriette’s, the phrase “We Zulus” frequently occurs (

Marks 1963, p. 409). In July 1897, in an emotional address to the Zulu people, Harriette used her Zulu names and referred to herself as a Zulu. She wrote from London with the news of the settlement that had been made to secure the return of Dinuzulu and the chiefs, then in exile on St. Helena, to Zululand. She explained that this involved “a division of the land” which, she emphasised, “is shameful for me since I am too a white-person”. “Nevertheless”, she continued, “(here speaks Inkansi [the stubborn one]

who is a Zulu) …

we Zulus may ourselves buy the land, in the future”. She ends her letter, “I am Matotoba, Mandizi [the one who flies] Daughter of Sobantu” [emphases added] (

Guy 2002, pp. 426–27). Thus, as well as merging her family with that of the Zulu royal family in terms of their mutual kinship relations, Harriette also merged her cultural and social identity with that of the Zulu people.

Harriette was later to confirm her kin relationship with Cetshwayo’s son, Dinuzulu, explicitly and specifically as being his

paternal aunt. In 1897, assuring her sister, Agnes, of the propriety of their sleeping arrangements when she stayed overnight at Dinuzulu’s house in St. Helena (see below), Harriette referred to, “My position towards him being that of a paternal aunt the arrangement is strictly proper” (

Guy 2002, p. 429). Later, in correspondence, Dinuzulu was to write to Harriette referring to her as “his aunt” (

Marks 1970, p. 289). Thus, even at a time of heightened conflict and tension between white colonists and the colonial government of Natal, on the one hand, and the Zulu populations of Zululand and Natal, on the other hand (or perhaps

because of these antagonistic relations), we can see the links between the two families as examples of kinship relationships extending across the colonial divide.

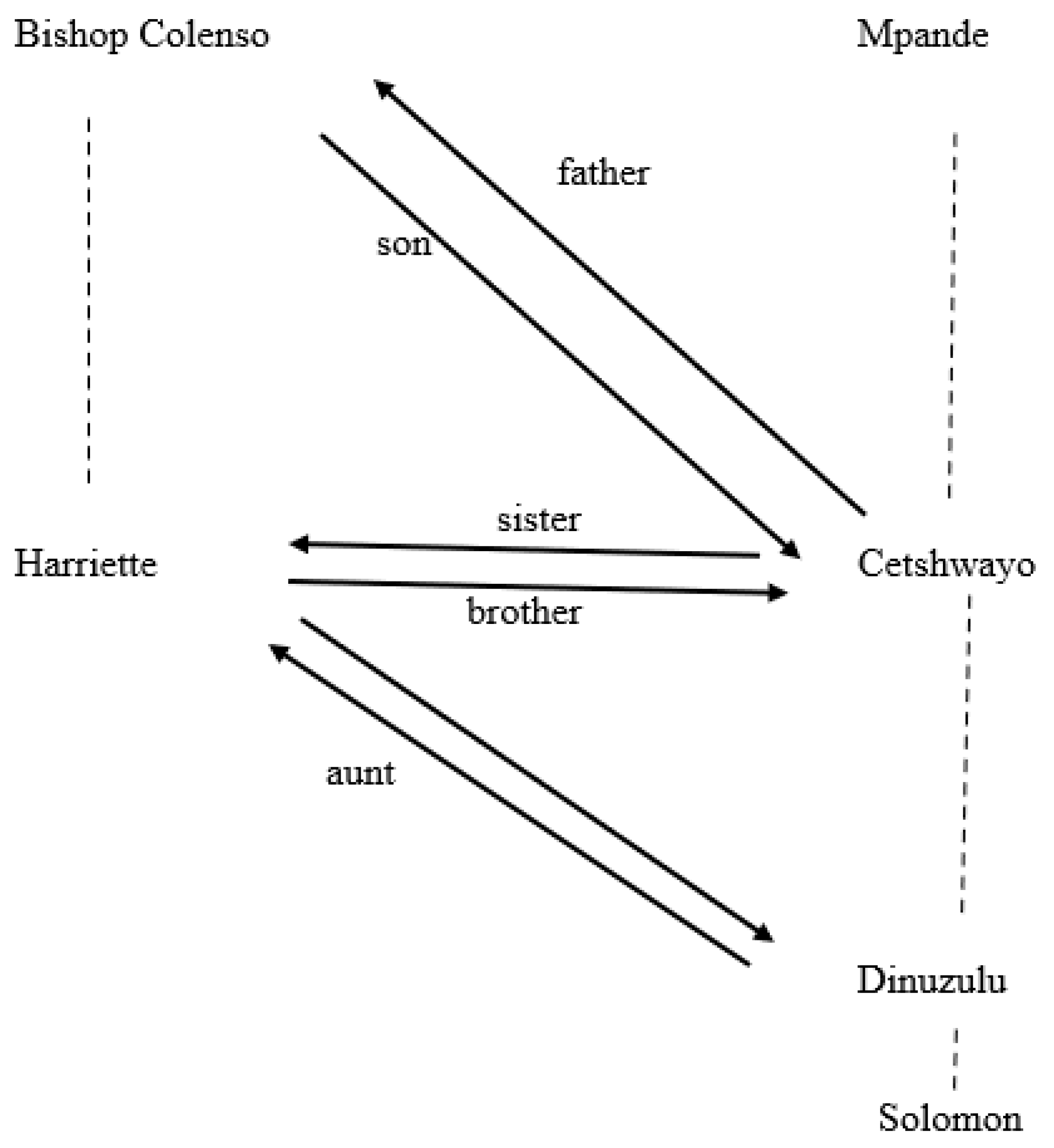

The relationship between the families, represented as bonds of kinship, can be set out as shown in

Figure 2.

It is necessary here to note the need for caution to be exercised over the use of the term “father”, as the term could be used as one of respect or to acknowledge an imbalance of power in a relationship, rather than one of filiation. At his final interview with Lord Kimberley in the Colonial Office in London, when Cetshwayo responded negatively to being told he would have to accept the partition of his kingdom, a Zulu advisor who had accompanied the king to the meeting explained to Lord Kimberley that Cetshwayo expressed his feelings to him as that of a child who “has simply spoken to its father” (

Guy 1994, p. 155). However, the suggested relationship to Lord Kimberley was clearly figurative and more one of deference, or even obeisance, than a putative kinship tie. There are also occasions when an indigenous person might use the term “father” to indicate respect when addressing a colonial official or a man in a position of power. This was the case when Cetshwayo addressed Shepstone as “my Father” (

R. Cope 1999, p. 133). Here, Cetshwayo knew he was dealing with a person who could wield great power, either for or against him, but whom he saw as a wily negotiator whom he could not trust. I suggest that this would be the equivalent, in white society, to calling him “sir”. However, when Cetshwayo used the term in reference to Bishop Colenso, he did not use it purely as a sign of respect or deference towards the bishop. But, rather, as indicated above, because he saw himself as a member of the Colenso family, with further lateral kinship ties which recognised the bishop’s children as his siblings.

4. A Political Alliance

The kinship relationships between members of the Cetshwayo and Colenso families were overlaid by, and formed a framework for, a network of political relations between their individual members, which amounted to a political alliance between the two families. As we identify further examples of the relationship between the two families, it will become apparent that the two types of relationship are closely intertwined, one with the other. I shall explore further relations between members of the two families primarily by following the campaigning work of Bishop Colenso’s eldest daughter, Harriette, in so far as this related to her dealings with Cetshwayo’s family members.

Bishop Colenso’s relationship with Cetshwayo got off to a shaky start. Colenso had included among his mission school pupils, Mkhungo, a son of Mpande, the Zulu king, apparently in the expectation that he (Colenso) could educate the future king of Zululand as a Christian and, hence, facilitate the Christianisation of the people of Zululand. However, when, in 1859, Colenso travelled into Zululand to meet Mpande, this notion was quickly dispelled as it became apparent that Cetshwayo, another son of Mpande (by a different wife), had been identified as the likely successor to Mpande. This was the occasion of Bishop Colenso’s first meeting with Cetshwayo, whom he estimated to be aged 29 or 30 years at the time. Their meeting was cordial (

Edgecombe 1982, pp. xxii–xxx). They were not to meet again for over 20 years, by which time Bishop Colenso had undergone a transformation in his attitude towards the Government of Natal.

Harriette’s first meeting with members of the Zulu royal family was in May 1880, when a deputation of 200 Zulu, including chiefs and members of the royal family and royal household, arrived at Bishopstowe from Zululand. They were on their way back from Pietermaritzburg after petitioning for the release from prison and return of their king, Cetshwayo. The deputation was led by close relatives of Cetshwayo, including his brothers, Ndabuko and Shingana, with whom Harriette was to become lifelong friends. This meeting with Cetshwayo’s brothers could be seen as the beginning of an enduring alliance between Harriette and Cetshwayo’s family. Harriette was then 33 years old (

Guy 2002, p. 61).

It was later that year that Harriette accompanied her father to visit Cetshwayo in prison in Cape Town. At their meeting, the energetic handshake between the King and the bishop could be regarded as cementing the kinship and political alliance between the house of Cetshwayo and the house of Sobantu, which was to continue for three decades. This was Harriette’s first meeting with Cetshwayo, and it was crucial in reaffirming her relationship with the Zulu royal family, which had begun with her meeting his brothers earlier that year. From this point on, Harriette’s life was to become interwoven with that of the members of the Zulu royal family and their followers, known as the Usuthu and later referred to by Harriette as the “Zulu National Party” (

Guy 2002, p. 150). Shepstone and other officials, attempting to dilute the centralising power of the Zulu royal house, had argued that historically the Zulu people had consisted of a conglomerate of separate groups, some dating back to pre-Shakan times. In contrast, following her father’s view, Harriette had maintained that the royal house was the integrating principle for the Zulu people and that it was their loyalty to the Zulu royal house that gave the Zulu people a corporate identity (

Nicholls 1995, pp. 3/4). She saw the Usuthu as core to this identity, rather than their being followers of just one among a number of different chiefs.

6After protracted negotiations with the British government and colonial officials in Southern Africa, it was eventually agreed that Cetshwayo would travel to England. He did so in July 1882. Ironically, though at the time technically a prisoner of war, Cetshwayo was met with great enthusiasm by the British public and graciously received by Queen Victoria and by her son and daughter-in-law, the Prince and Princess of Wales. But Natal officials intervened in the political negotiations over Cetshwayo’s future and the future of Zululand (

G. Colenso 2017, pp. 8–12). Returned to Zululand, Cetshwayo was installed on 28 January 1883, but only as chief of the central territory of Zululand rather than as the Zulu King. He was to rule over only a portion of his former kingdom, another part of the country being allocated to his enemies in a way guaranteed to foment civil war (

Guy 1994, pp. 172–73).

It was only five months after the return of Cetshwayo to Zululand that, in June 1883, Bishop Colenso was taken ill and died (

Guy 1983, p. 344). Cetshwayo was devastated to hear of the bishop’s death. Continuing conflict in Zululand had led him to seek refuge in the Reserve—that part of the partitioned country which had been placed under the authority of a Natal appointed ‘Resident’. However, in February 1884, Cetshwayo was found dead in circumstances that were to be the subject of controversy. The Usuthu alleged that he had been poisoned (

Binns 1968, pp. 259–60). In a statement by him, read out three days after his death, Cetshwayo said, “I, Cetshwayo, leave the country to my son Dinuzulu for him to have when I am no longer here …and when I die, I shall not be altogether dead, as my son Dinuzulu will live” (

Guy 1994, pp. 206–8;

2002, p. 6).

The death of Cetshwayo was followed by years of turmoil in Zululand during which time Dinuzulu became embroiled in conflict with a number of different adversaries: with Zibhebhu, the government-sponsored chief of the Mandlakazi who had been largely responsible for his father’s death; with the Transvaal Boers who were seeking land and cattle in Zululand; and with Natal and Natal-inspired officialdom seeking to break Dinuzulu’s power in order to hasten the breakup of the Zulu nation and, thus, allow the penetration of Zululand by white settlers from Natal seeking land (

Marks 1963, p. 407). Dinuzulu was deemed by the authorities to have taken part in a “rebellion” and a warrant for his arrest was issued by the Governor of Natal (

Guy 2002, p. 259).

After her father’s death, in correspondence with Zulu chiefs, Harriette continued to emphasise her place in the Colenso family but, more importantly, her legitimacy to speak as the daughter of her father, and in his name, rather than purporting to speak with his words, as she did shortly after his death in 1883. In May 1888, in a message addressed to the “heads of the Zulu people” to urge them to adopt peaceful negotiations with the authorities, she began, “It is I Dlwedhlwe, daughter of Sobantu, who am now sending to you … in the name of my Father Sobantu” (

Guy 2002, p. 221). In a very few words, Harriette twice stresses that she is her father’s daughter and that she speaks

in his name. Harriette makes use of her legitimacy to speak as the daughter of her father, repeatedly invoking the principle of heredity.

Again, using the legitimacy of her father’s name, in July 1888, Harriette wrote to Dinuzulu and the Zulu chiefs, counselling them to surrender. Her letter was addressed to the “HEADS of the ZULU PEOPLE, to DINUZULU, and to NDABUKO, and to SHINGANA, princes of the Zulus, and cared for of SOBANTU”.

It ended “Be well assured that whatever happens, I and all Sobantu’s family, still grieve for you and protest for you also, [emphasis added]. She signed it: It is I who write, Dlwedhlwe, daughter of Sobantu” [emphasis added] (

Guy 2002, pp. 243–46).

We note that she signs herself as her father’s daughter (using her Zulu name referring to her relationship with her father) and pledges support for the chiefs from “all Sobantu’s family”. We may, therefore, also note the reaffirmation, by Harriette, of the enduring tie of loyalty between the two families. This letter also displays a strong emotional content and intensity of feeling that is apparent in Harriette’s other communications with the Zulu leaders.

In August 1888, the Usuthu leaders began to surrender. In November, Dinuzulu surrendered but did so by going to Bishopstowe (

Binns 1968, p. 135;

Guy 2002, p. 260–61). He and his uncles, Ndabuko and Shingana, and other Zulu chiefs were charged with high treason, rebellion, and public violence (

Guy 2002, p. 282). The trial was held in Eshowe in Zululand. It was the first of two treason trials that Dinuzulu was to be subjected to. Harriette spent six months there organising and overseeing the defence of the chiefs. After the trial, those convicted avoided the gallows but were sentenced to ten years or more in prison (

Guy 2002, pp. 290–92). However, rather than imprison Dinuzulu and his uncles anywhere in Southern Africa on the mainland, it was decided to exile the chiefs to a remote location to avoid the danger that Harriette might “intrigue with them” (

Guy 2002, p. 308). Dinuzulu and his uncles were, therefore, exiled to the island of St. Helena.

Harriette spent most of the 1890s campaigning for the release from exile of Dinuzulu and the chiefs and for their return to Zululand, which did not take place until nearly the end of the decade. During this period, she visited Britain twice and St. Helena twice. In January 1890, she embarked on the first of her visits to Britain in that decade. It was not until January 1898, eight years later, after her second visit to Britain and St. Helena, that she was to arrive back in Natal with the chiefs on their return from exile.

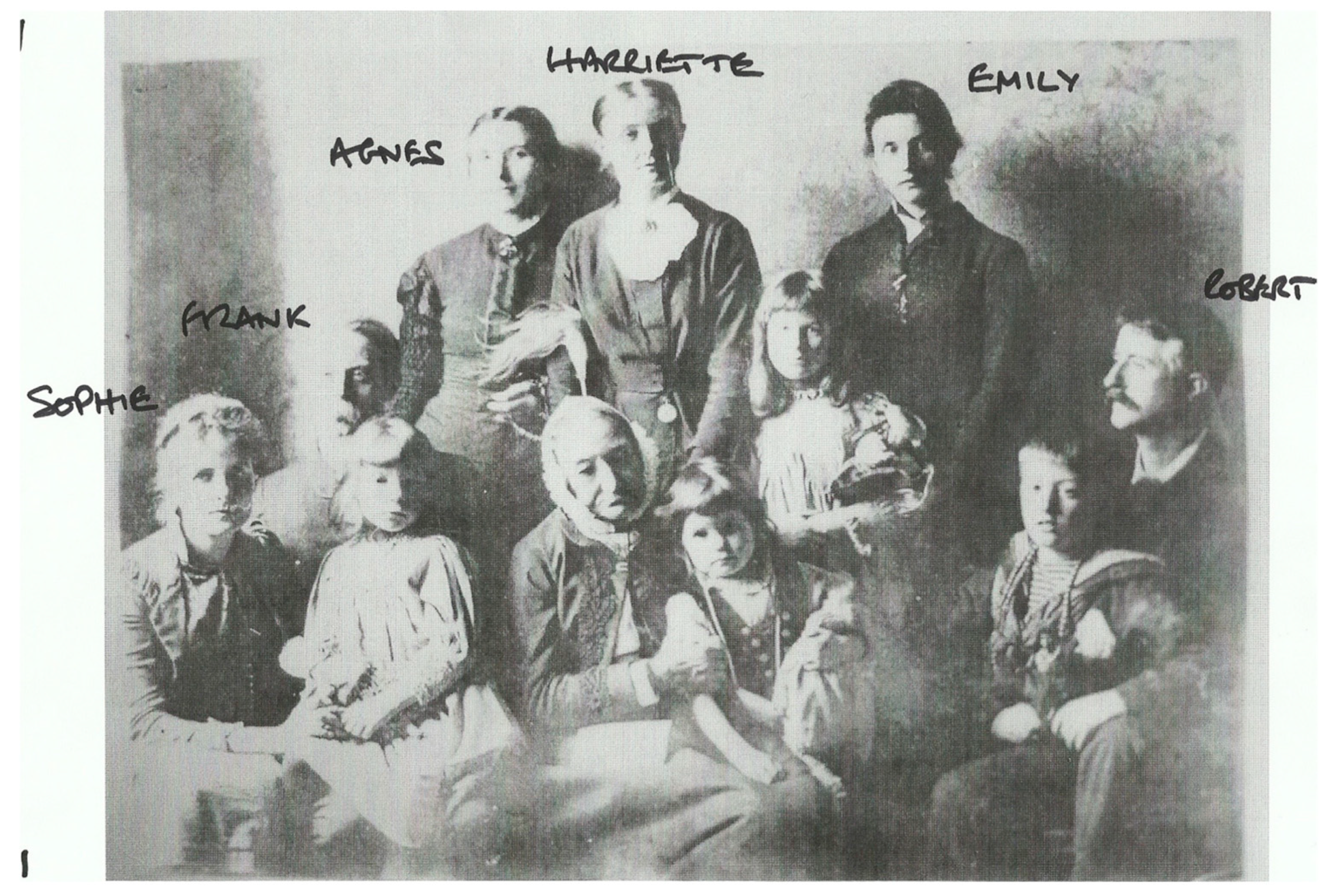

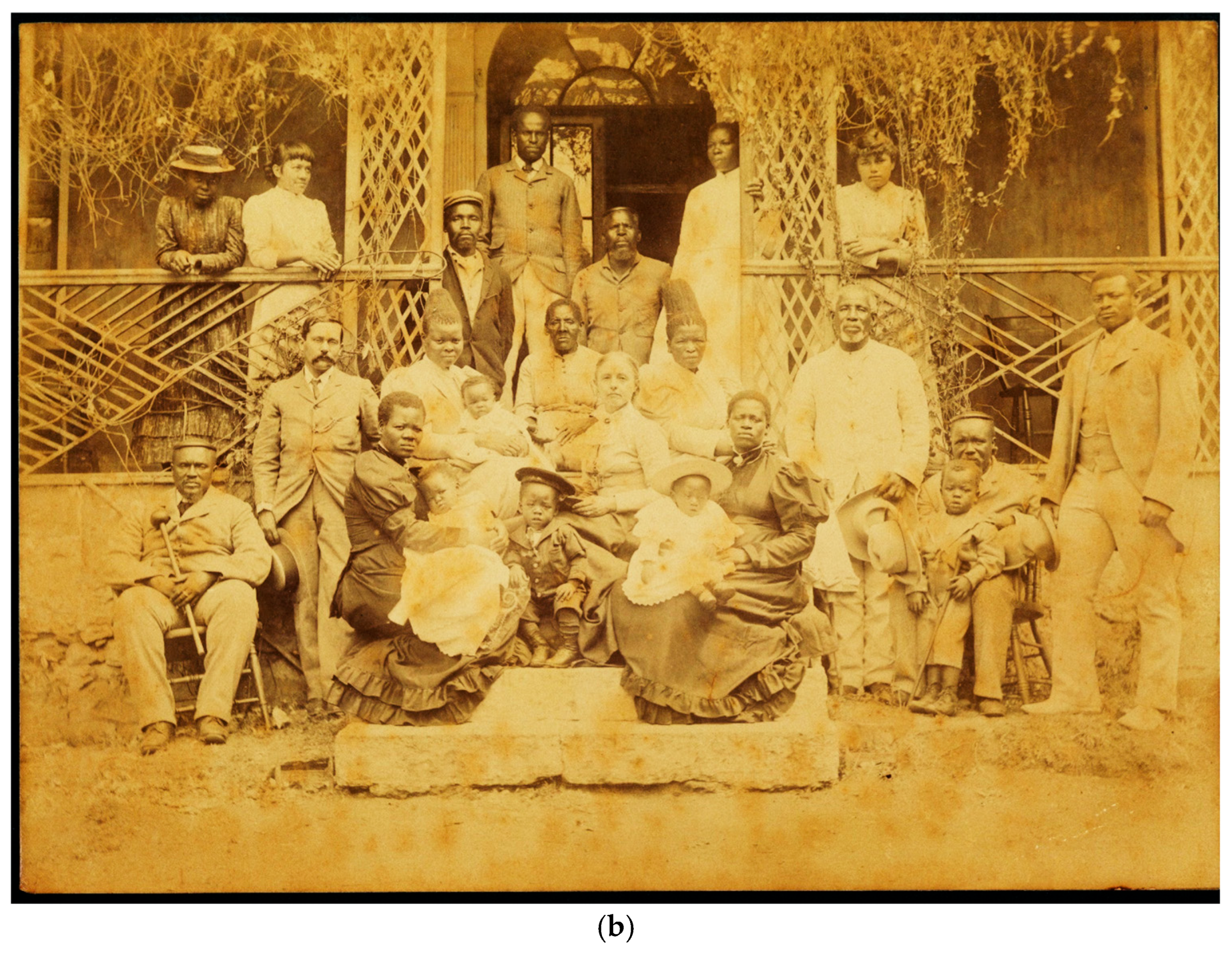

In January 1890, Harriette travelled to Britain accompanied by her mother and her younger sister, Agnes (

Guy 2002, p. 307). This led to the reuniting in Britain of the branches of the bishop’s family who had been divided between Natal and Britain. A family photo taken in the early 1890s during the visit to England by Harriette, Agnes, and their mother can be used to assess the dynamics within the family. See

Figure 3.

There are a number of key things that this photo tells us.

In the centre is the widow of Bishop Colenso. If we look at the younger adults in the photo, it is the women who come across as the stronger characters and perhaps more focused than the two men (Harriette’s two brothers), who are looking sideways or away from the camera. It can be seen that the person with the overall commanding position in the group is Harriette. She is at the centre of the top of the picture. To her left is her sister-in-law, Emily, and in the bottom–left of the photo is her sister-in-law, Sophie (seated next to her husband, Frank). Leading the Natal branch of the family, as the person most dedicated to pursuing her father’s course in defending the Zulu people, Harriette is, I suggest, substituting for her father as head of family, in both Natal and England. Agnes, who is positioned just behind Harriette, occupies a slightly background position, which reflects her deference towards, and her supporting role to, her older sister. Finally, as far as Harriette is concerned, the reason for her being in England (apart from family reunion) can be seen from what she is holding. She is displaying the white cow’s tail, a symbol of Usuthu followers of Cetshwayo and, therefore, in Harriette’s view, of Zulu nationalism. Harriette has, therefore, made this photo a statement of the Colenso family’s support for the cause of the Zulu and, therefore, of the exiled Zulu chiefs (

Guy 2002, p. 333).

5. The Zulu Royal Family: Heredity, Succession, and Legitimacy

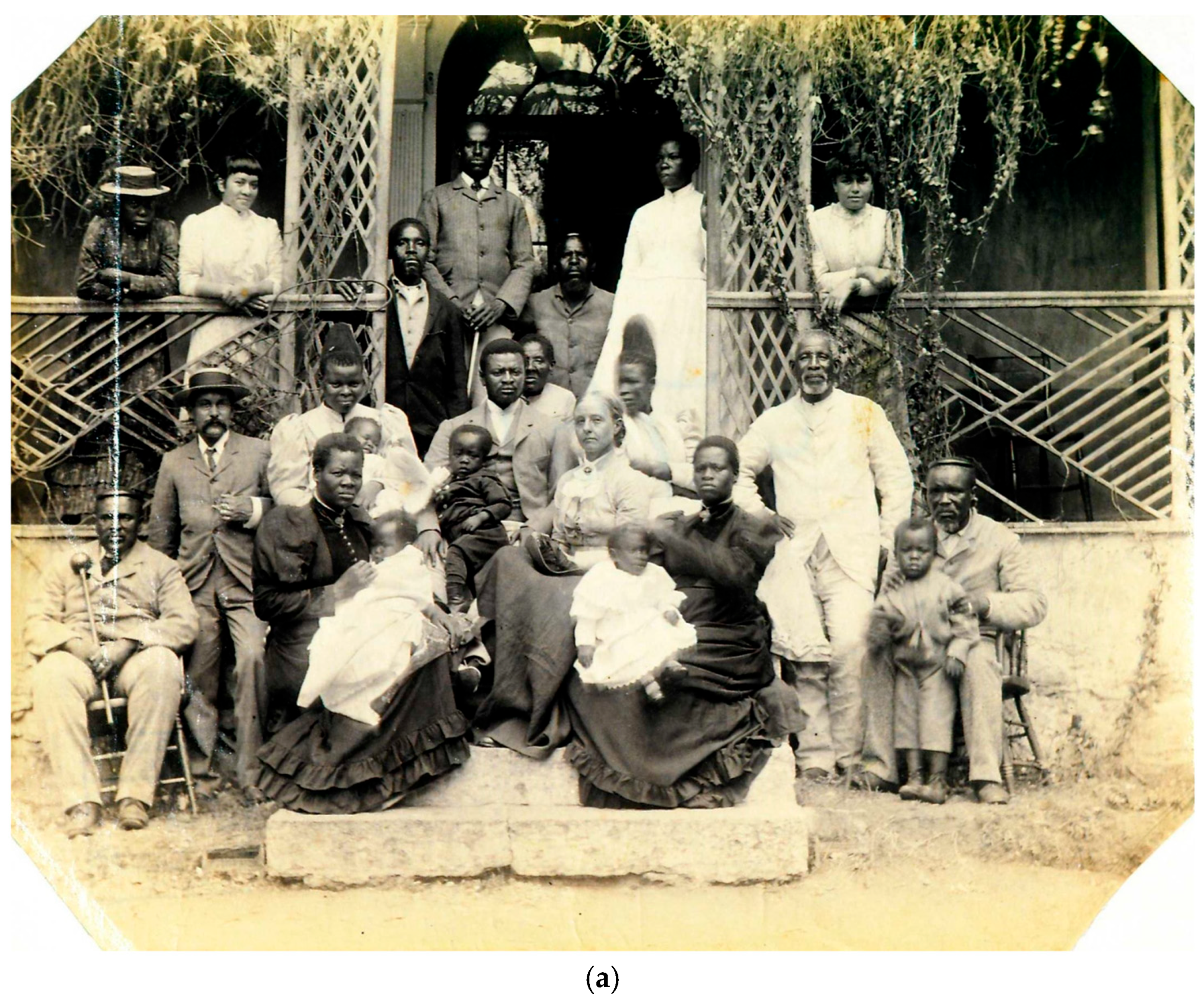

Harriette’s second visit to Britain in the 1890s was in 1895, when she travelled there by herself. Her mother had died in 1893, and Agnes remained in Natal. Harriette stopped at St. Helena on the way to Britain and again on the way back in 1897—on the latter occasion, sailing with Dinuzulu and the chiefs accompanying them on their return to Zululand after their release from exile. On her visit to St. Helena in February and March 1895, she was photographed with Dinuzulu and his uncles, wives, and children (

Guy 2002, p. 383).

In

Figure 4a, the central group is Dinuzulu and Harriette, with Dinuzulu’s two wives and their daughter and two sons. They are flanked by Dinuzulu’s uncles, Ndabuko on the left of the picture and Shingana on the right, both seated, who are, therefore, persons of Cetshwayo’s generation. So, we have three generations in this photograph, including the generation with the future heirs to the throne.

However, another photo was taken, probably on the same occasion. In this second photo, shown in

Figure 4b, the central group has Harriette in central position without Dinuzulu, who is standing to one side, but with the wives, heirs, and uncles of Dinuzulu in much the same positions as in the previous photo.

In both photos, the three infants are the children of Dinuzulu by his two wives. Taking the photo shown in

Figure 4b, in the central group, from left to right, are his daughter, Victoria (on her mother’s knee); in the middle, his older son, David (standing against Harriette’s knees in this photo); and, on the right, Dinuzulu’s youngest son, Solomon (on his mother’s knee).

It seems that more than one attempt was made to get pictures of the family group that satisfied Harriette. Writing to Agnes from Maldivia, the residence of the exiled chiefs on the island, Harriette told her sister, “… in the photo we have sent you the uncles are the only failures but we have got what I believe will be an excellent one of each of them there this morning & I am to carry off the negative” (Arch ref e). The photos that we see here were probably taken on the steps to the veranda of Maldivia. We can only speculate that Harriette was unable to dissuade onlookers who were not part of the family group from posing on the veranda behind the family members that were meant to be the subject of the photos. Harriette was obviously concerned to have copies of these photos, or at least one of them—most likely to be the one shown in

Figure 4b. After stopping at St. Helena in 1895, Harriette went to England, where she spent two years lobbying the colonial office for the return of the exiled chiefs before returning to Natal via St. Helena in 1897. While in England, she left with her brother, Frank, negatives of photographs taken in St. Helena. Writing to Frank onboard ship returning from St. Helena to Durban, she asked, “Have you got the St Helena’s negatives safe? I left them for you … and please, I want a copy of the large group with me in the middle, sent to this address—as soon as you conveniently can” (Arch ref f).

There are two key points to be made about these photos.

Both photos are about affirming the royal status of Cetshwayo’s dynastic line by presenting the grouping around Dinuzulu and Harriette as if it were an upper-class English Victorian family. And not just any Victorian family, but one looking like the family of Queen Victoria. Photographs of Dinuzulu taken over the six-year period before this photo was taken, and which there is not room to show here, trace a gradual transition in the presentation of himself from wearing traditional Zulu dress to formal Western attire until, in the photos shown in

Figure 4a,b, he, and all the members of his family, are dressed in a way that could be considered respectable and “civilised” by European standards. It was said of Dinuzulu that visitors came to the island expecting to see a half-naked Zulu savage and instead they saw a “an intelligent looking negro gentleman” (

Guy 2002, p. 384). Patronising though this statement is, it perhaps illustrates the effect that Dinuzulu intended to create. The intention behind the photos, I suggest, is to provide a portrait of the family, presenting them as worthy to be regarded as a royal family from a Western, European, viewpoint and so deserving of a dignified resolution to their situation—ideally to be restored as the royal family in Zululand.

But what is Harriette’s role in the second photo (

Figure 4b)? As a respectable-looking middle-aged white woman, Harriette’s central position might be considered to enhance the credibility of the family as being comparable to an English upper-class Victorian family. In this photo, we see that Harriette is in the centre of the group and Dinuzulu is standing to one side. Why has Dinuzulu withdrawn in this photo, leaving Harriette to take up the central position without him? In endeavouring to address this question, I will return to the meeting between Dinuzulu’s father, Cetshwayo, and Queen Victoria in 1882—an event which was to be of crucial importance in the Zulu view of the history of their relations with the British crown and the British people.

There had been a perception by Cetshwayo of equality between the Zulu and British royal families, and of the equivalence of his position and status in Zululand to that of Queen Victoria in her realm. This impression seemed to him to be endorsed by his experience when he visited Britain in 1882. He was received by the Queen and regarded by both the public and British press as if he were a visiting royal. In a previous publication, I provided a description, drawn from contemporary press reports, of the “ceremony and regal trappings” surrounding Cetshwayo’s “gracious” reception by Queen Victoria, and his reaction to it, as follows:

“When Cetshwayo arrived at Portsmouth to go by yacht to see the Queen at Osborne House, “crimson-covered steps were placed up to the door of his carriage”, he was saluted by an Admiral, a Rear Admiral, and “other officers of the British service”, before ascending to the yacht along “The crimson-covered gangways generally used on the occasion of the visits of royalty”. “On arriving at Cowes the ex-king was driven in a Royal carriage to Osborne … the crew of the Royal yacht Victoria and Albert forming a guard of honour”. Cetshwayo appeared to accept the attribution of shared royal status when, after his interview with the Queen, he said of her, “She, like myself, was born to rule men. We are alike”. It is also significant that he made a separate visit to the Prince and Princess of Wales in their residence, Marlborough House. After this visit, Cetshwayo reciprocated the perception of shared noble rank with the Prince when he said of him, “Yes, he is indeed a nobleman”. “The pomp and pageantry of Cetshwayo’s progress to his reception with the Queen might have been that [provided for] … a visiting foreign monarch”.

The press supported the view of Cetshwayo’s noble, and even royal, status, commenting on his “dignified deportment” and asserting that, “The King himself is every inch a King … and he has all the dignity and urbanity that becomes his position” (

G. Colenso 2013a, p. 40, n. 47); ‘Cetshwayo interviewed’, The Leeds Mercury, 21 Aug 1882; Aberdeen Weekly Journal, 19 Aug 1882; Pall Mall Gazette, 21 Aug 1882, 1, 2).

7We should also note the change in Cetshwayo’s view of his relationship with Queen Victoria as a result of his meeting with her in 1882. Cetshwayo had referred to Victoria before travelling to England, in a way consistent with the view, widely held among colonised people, of Queen Victoria as a “mother”, or “Great White Mother”, of all “her” people across the empire.

8 But,

after their meeting in 1882, the position had changed. Cetshwayo considered that, as a result of their meeting, he had established a strong personal relationship with the Queen. When he was returned to Zululand in January 1883, his chief minister, Mnyamana, said of Cetshwayo, “He comes today from his mother and is now the son of the Queen” (

Guy 1994, p. 173) This claim was to be repeated by Cetshwayo himself just before he died, as related by his brother Shingana, who reported Cetshwayo’s words to a colonial official: “I have become the son of the Queen …” (

Guy 2002, p. 6). It is clear that these statements by Mnyamana and Cetshwayo indicate their belief in something fundamental and new about the nature of the relationship between Cetshwayo and Queen Victoria. It had become a personal relationship between them

as individuals: from the Zulu point of view, that of mother–son.

Cetshwayo’s view of his shared royal status with Queen Victoria may have been passed down to his son and the royal family and household, and more broadly among the Zulu people. Hence, in the Zulu imaginary, there may have been a view that the Zulu and British royal families were

comparable in the legitimacy of their royal status, each within their own country. Could Harriette be seen as playing a part in this purported equivalence, in acting as a white matriarch occupying a central position in the Zulu royal family equivalent to the position of Queen Victoria in the British Royal family? The intention to enhance the standing of the Zulu royal family to stand comparison with that of European royal families can, perhaps, go some way to explaining the transformation in the demeanour and dress of the Zulu chiefs and their family members while on St. Helena. The photos of 1895 were possibly intended to present the Zulu royal family as eligible to join the club of European royal families. Could there have been some modelling of the Zulu royal family on Queen Victoria’s family—in terms of dress and the configuration of the group, as seen, for example, in the photo in

Figure 5 taken two years previously?

To provide reassurance of the long-term viability of the Zulu royal family, there was a need to ensure its succession and to demonstrate that this succession was secured. This brings us to the second important function of the photos taken on St. Helena. The photographs show us three generations of the Zulu royal family: Dinuzulu, the incumbent to the Zulu kingship (in the Zulu perception); the generation above Dinuzulu, represented by Shingana and Ndabuko, the brothers of Cetshwayo, his father; and the generation beneath Dinuzulu, represented by his sons and daughter. This visual presentation of the royal family is about affirming a continuation of the Zulu royal dynasty by demonstrating, visibly and concretely, the viability of succession to it in the form of Dinuzulu’s two sons and heirs to the throne (with Harriette substituting for Dinuzulu in one of the photos—as discussed above). Again, the comparison with the British monarchy is appropriate. In this connection, it is very relevant that a biographer of Dinuzulu’s son, heir, and successor, Solomon, has pointed out that “The British monarchy appealed to the sentiment so ingrained in the tribal world-view, at the heart of which was the notion that political legitimacy was in the first instance

imputed by birth” [emphasis added] (

N. Cope 1993, p. 133). That is, the line of succession to the throne is determined by the principle of heredity.

However, it is important to note that, although political legitimacy was conditioned by birth, in a polygamous society, such as Zulu society, this is ‘in the first instance’. The principle of heredity, though paramount, was not sufficient to fully determine succession due to the possibility of different heirs by different wives of the incumbent. Birth set the parameters of succession and, within these parameters, the actual succession was to be determined by other means, as was to be the case between Dinuzulu’s two sons, as we shall see. Nevertheless, allowing for this qualification to the principle of heredity, the photos taken on St. Helena present to the viewer the male heirs of Dinuzulu. Harriette could be seen as playing a part in this as a matriarch in the family. Perhaps she had already been accredited with a sort of authority to endorse the line of succession to Dinuzulu through David or Solomon (see below).

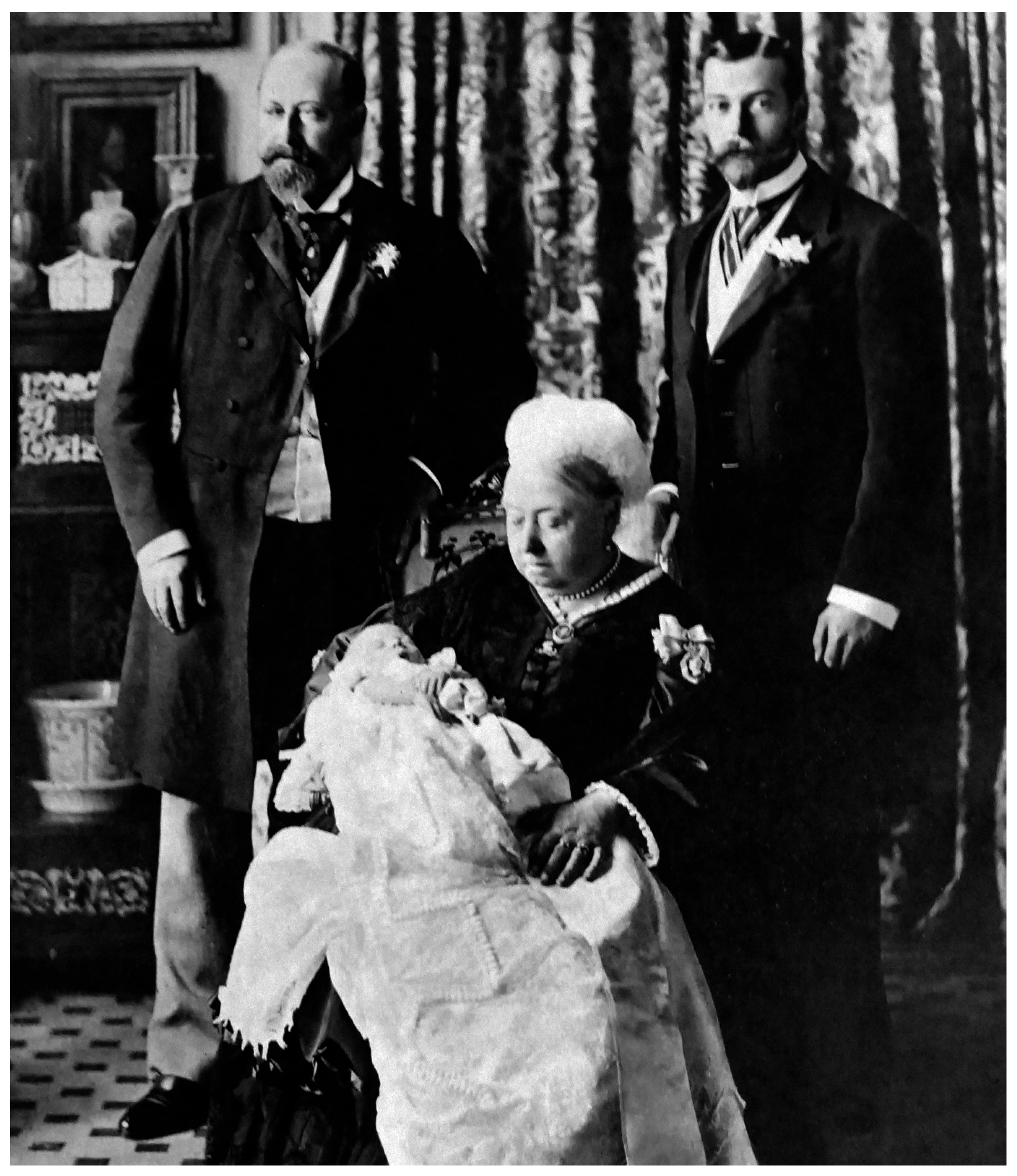

In this connection, I want to make a comparison with representations of the British royal family in a photo taken not too distant in time from when the St. Helena photos were taken of the Zulu royal family.

Figure 6 is a photo of the British royal family, also demonstrating the line of succession by heredity, in this case, over four generations, and featuring (as the baby) the future King Edward VIII. With future kings Edward VII and George V, first and second in line to the throne, standing behind her, Queen Victoria, seated, holds the future King Edward VIII. The date of his birth in June 1894 dates this photo to only a few months before the photos on St. Helena were taken. But it is not known if Harriette would have seen it.

Another example is the portrait by Holbein of Henry VIII with his queen, Jane Seymour, and his heir, the future Edward VI, in the foreground. Interestingly, in the background, we see King Henry’s parents, even though, at the time of painting, they would have been deceased. However, their inclusion illustrates the need to show the

vertical continuity between generations, just as is shown in the St. Helena photos, which include Dinuzulu’s uncles, who represent his father’s generation. See

Figure 7.

In October 2013 a series of photographs was released to mark the christening of Prince George, then the latest addition to the British royal family. These photos, captioned in the press as portraits that show the future of the British monarchy, present the late Queen Elizabeth II and her late consort husband as one of the four generations of the British royal family shown in the photographs. Of this series of photos of the royal family, the Telegraph says, “their message is clear:

the monarchy is here to stay” [emphasis added]. One picture, says the Telegraph, “sums up

the continuity which is the monarchy’s greatest strength” [emphasis added] (Telegraph, 23 October 2013). This picture, which for copyright reasons cannot be reproduced here, shows the late Queen posing with the next three heirs to the throne: her son, then Prince Charles; grandson, Prince William; and great grandson (the recently christened Prince George). We may compare this with

Figure 6, which shows Queen Victoria in 1894 with her next three heirs. In each, the monarch is seen with her next three heirs to the throne in almost identical groupings—in photos taken over 100 years apart.

It appears that there is a formula that is common to portraits of both the Zulu and British royal families. This is to assemble living members (and, if need be, deceased members) of the dynasty together, arranged in a reasonable order, and have the baby, or latest in the line of descent, in the middle, and at, or near, the front. These photos confirm both the strength and endurance of the dynasty and that the succession is guaranteed by heredity for at least as many generations as are on display. The message is as suggested by the Telegraph article accompanying Prince George’s christening photo—that “the monarchy is here to stay”.

The St. Helena photos proclaim the same message. We do not have Cetshwayo painted in. But we have the equivalent, which is Cetshwayo’s brothers, Ndabuko and Shingana, to stand in for him, representing the previous generation. What these photos are emphasising is succession to the royal line by heredity. It can be postulated that Harriette is here using the distribution and containment of power embodied in the British royal family as a template for reviving and re-establishing the locus of power within Zululand by the revival and rebirth of the power of the Zulu royal family and, hence, the revival of the strength, independence, and vitality, of civil society within the Zulu nation.

In her letter of July 1897, referred to above, in which Harriette informed her Zulu contacts of the terms on which Dinuzulu was to be allowed to return to Zululand, she refers to the importance of securing the role of Induna. But, before doing so, she says, “What we bring with us now [on returning to Zululand from St Helena] … [are]

the Princes themselves [i.e., David and Solomon—Dinuzulu’s sons]” [Emphasis added] (

Guy 2002, p. 427).

The group photographs shown in

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b are important, as they provide visible, concrete evidence that the succession is secure, as “imputed by birth”. It has the effect of Harriette saying: “It can be seen that as we’ve

got the princes themselves the royal line can be guaranteed to continue”. The photos taken on St. Helena show that the succession to the Zulu kingship is secure, just as the photos of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II demonstrate the viability of the succession to the throne of the British royal family.

6. Dinuzulu and the Struggle for Recognition in a British Colony

Finally, Dinuzulu’s return from exile was agreed. But, following a settlement between the British and Natal governments, he was returned to Zululand, not as the Zulu King, but only as government “Induna”—i.e., advisor to the government on Zulu affairs. Zululand had been annexed by the British government in 1887, thus bringing the country directly under British rule (

Binns 1968, pp. 96–97;

Brookes and Webb 1965, pp. 154–55). But, a condition of the return of the exiles was the agreement, exacted by Natal, that Zululand should first be annexed to Natal (

Marks 1970, pp. 101–10;

Guy 2002, pp. 402–28). This would mean that Dinuzulu would be subject to direct rule by the Natal government without the possibility of the British government intervening on his behalf. That is, except in one respect. In what was described by Harriette as “a backhander for Natal”, the British authorities had affirmed that Dinuzulu’s position of Induna “will not be withdrawn without the approval of the Secretary of State” (Arch ref g).

Despite all the drawbacks of the terms of the return of Dinuzulu, Harriette concluded that it was “the least of all the evils”, and she sought to emphasise the positive aspects of the arrangement to the Zulu people. In her letter of July 1897 to her Zulu contact, Harriette suggests that the role of “government induna” secured for Dinuzulu should be seen as a positive gain for the Zulu people, as it was to be a position that applied over

all of Zululand (

Guy 2002, pp. 426–27). And, although the Natal government could have wished to reduce the standing of Dinuzulu as much as possible, at the very least, any attempt by them to remove the status of Induna from him had been thwarted by the terms attached by the British government to the agreement on the return of Dinuzulu from exile. The position of Induna was a role, Harriette may have hoped, that could in time be built upon and developed into that of kingship.

Dinuzulu and the other exiled chiefs and their families arrived in Durban in January 1898, accompanied by Harriette. However, once back in Zululand, Dinuzulu’s requests to be accorded some recognition of his royal status were roundly dismissed by the Natal authorities. Less than a decade after Dinuzulu’s return to Zululand, the Natal government levied a poll tax in Natal and Zululand, which came into effect in 1906. The tax provoked a rebellion, initially in Natal, but then spreading to Zululand. It was known as the Zulu Rebellion of 1906 or Bambatha

9 Rebellion (

Marks 1970, pp. 171–246;

Binns 1968, pp. 177–221). Suspicion was raised that Dinuzulu was behind the rebellion. In April 1906, he sent a message to the Natal government affirming his loyalty and offering to raise a force to fight against the Bambatha (

Marks 1970, p. 209). At the same time, he wrote a letter to the (British) King expressing his loyalty and offering to raise a levy to aid the Natal forces in putting down the rebellion. But the king’s reply was prevented from being delivered to Dinuzulu by the intervention of the Natal Governor (

Marks 1970, p. 252).

In May of the following year, Dinuzulu came under suspicion again for his involvement in the Zulu rebellion. As a result of persuasion by Harriette, he travelled to Natal to meet the outgoing Governor of Natal. His journey took on “the nature of a triumphal progress” attended by crowds giving him the royal salute. On this occasion, he was to stay at Bishopstowe overnight with Harriette and Agnes. This is an indication of the continued informal and intimate relations between the two families at the time. It was also an event which was considered worthy of a news item in the Natal press. The next day, Dinuzulu went to Government House in Pietermaritzburg, accompanied by a bodyguard on horseback. At their meeting, the governor had satisfied himself of Dinuzulu’s innocence (

Marks 1970, p. 296;

Binns 1968, pp. 232–33). But, later in the year (and with a new governor in office), there was a change of mood on the part of the Natal authorities. Martial law was declared, and a warrant was issued for the arrest of Dinuzulu, who, with the help of intervention from Harriette, was persuaded to surrender in December 1907 (

Binns 1968, pp. 235–42). He and many other Zulus were charged with rebellion, treason, and murder (although the murder charges against Dinuzulu were later dropped). Because of the conditions they had attached to the return from exile of Dinuzulu, the British Government was able to exert considerable pressure on Natal to ameliorate the conditions under which the trials were to be conducted. (

Marks 1970, pp. 261–71). The trials went on for two months and had extensive coverage in the Natal press. As with Dinuzulu’s previous treason trial, Harriette again played a major part in organising the defence.

On the first day that Dinuzulu was in court, an incident occurred which was reported in the press. Dinuzulu entered the court room and took his seat in “the box” which was bolted. The Natal Mercury reported that, “Harriette Colenso, who had arrived somewhat early, … went up to the prisoner, cordially shaking hands with him—an incident which apparently highly delighted the son of Cetywayo [sic]” (‘Dinuzulu’s Trial’, Natal Mercury, 27 November 1908). The handshake was between two prominent figures from different races, unequal in power, but who saw each other as equals and as closely related in terms of kinship and political alliance. It was a handshake across the divide. We are reminded of the demonstrative handshake between Harriette’s father and Dinuzulu’s father, described at the beginning of this article, when they had met in 1880 while the latter was in captivity in Cape Town.

But, unlike the handshake in Cape Town, this handshake was in public and was a newsworthy “incident”. It is clear that it was intended by Harriette as a

public avowal or declaration of equality and unity between the races, which was possibly shocking to some white people in the court. As such, the handshake confounded the assumptions prevalent among white colonists concerning the inferior status of Africans in the colony. How much it might have been considered by many whites in Natal to be in breach of the accepted code of practice can be judged from a comment made by the then Prime Minister of Natal on the fact that the Governor of St. Helena was known to have shaken Dinuzulu’s hand. The Natal Prime Minister complained that the handshake was an “

indiscreet indulgence”. It was a “privilege” that should never have been granted (

Guy 2002, p. 403). Such was the colonial divide in Natal, a divide which Harriette’s handshake sought to bridge. In this regard, it is notable that when the Bishop Colenso’s wife, Sarah Colenso, referred to Queen Victoria receiving Cetshwayo when he was in England, she chose to emphasise the queen “

shaking hands with him” as most illustrative of the “kindness” shown by the queen towards Cetshwayo [Emphasis in the original] (Sarah Colenso to Mrs Lyell 8 June 1885, reproduced in

Rees 1958, p. 399).

It was evident that, in South Africa, colonial attitudes towards such interracial contact had only hardened when, in 1947, nearly 40 years after Dinuzulu’s second treason trial, King George VI visited the country as part of a Royal tour. On the eve of the introduction of the formal system of Apartheid in what, by then, had become the Union of South Africa, the King was told that, as a white King, when greeting his African subjects, he was not permitted any physical contact in the form even of a handshake. This prevented him from pinning a medal on the chest of a black ex-serviceman or from shaking his hand. One chief, worried about the rumour that the King would not directly hand specially minted medallions to the chiefs, said that he did not know whether chiefs would accept them if they were not presented by the King himself, rather than by officials. However, though complying with this protocol while in South Africa, the King made it clear that he did not approve of such proscriptions and insisted that these customs not be replicated in the High Commission Territories of Bechuanaland, Basutoland, and Swaziland, which he also visited during the tour (

Sapire 2024, pp. 114, 123, 264).

As a result of his trial, though cleared of most of the charges against him, on 3 March 1909, Dinuzulu, was found guilty of three charges (

Binns 1968, pp. 253/4;

Marks 1970, p. 293) and sentenced to 4 years imprisonment, which was then commuted to exile (

Binns 1968, p. 255). During this period of exile, which was to be served in the Transvaal, it was commented by one sympathetic Natal official that, while Dinuzulu was absent from Zululand, Harriette had acted as a surrogate “father” to his youngest son, Solomon (

N. Cope 1993, p. 268).

In 1913, Dinuzulu died while still in exile. His body was brought from the Transvaal to Zululand. Harriette Colenso was present at the graveside. But the succession, as between Dinuzulu’s sons, David and Solomon, was disputed, and at the end of the first day of Dinuzulu’s funeral, the disputed succession was still unresolved. The next day, we are told, Harriette was asked by the king’s principal headman, Mankulumanu, to resolve the disputed succession. “Discreetly she told the keeper of the royal homesteads … to take Solomon’s hand and let him select a stone to place on Dinuzulu‘s coffin. This symbolic act was carried out in front of the whole assembly … [of approximately 7000 who attended the funeral.] David was then led to the grave to do the same. After him followed all the other men of importance, and the grave was presently filled” (

N. Cope 1993, pp. 40–41). And so, Solomon was confirmed as the heir to Dinuzulu. This act by Harriette represents the culmination of her close relationship with the Zulu royal family dating back for over 30 years, since she first met Cetshwayo’s brothers, Ndabuko and Shingana, at Bishopstowe in 1880 and, later that year, Cetshwayo himself in Cape Town. It was a momentous recognition of the relationship between the two families, bridging across the colonial divide.

7. Conclusions

We have considered the connections made between two families across the colonial divide in Natal and Zululand in the latter half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century.

We have seen that members of the families of Bishop Colenso and the Zulu King, Cetshwayo, came to consider themselves to be related by kinship, using specific kinship terms to address one another. Kinship relations extended between them, such that the two families were merged. In addition, Harriette Colenso considered herself not only a member of the Zulu royal family but also to have been absorbed into the Zulu people.

Kinship relations and political alliance between the two families were intertwined in the struggle for the restoration of the Zulu King and, indeed, of the Zulu kingship. Colenso family members, both in Natal and in England, were deployed in the service of the family’s campaigning work for the Zulu. With contacts from Bishopstowe in Natal into Zululand, family members on two continents played their parts in facilitating “an extensive chain of influence” between Zululand and Britain. On the death of Bishop Colenso in 1883, the leadership of the family’s campaigning work devolved to his eldest daughter, Harriette, whose work for the Zulu cause, after her father’s death, included the leading part she played in organising the defence, in two trials for treason, for Cetshwayo’s son, Dinuzulu.

In fighting to defend their kingly status from being downgraded by the Natal authorities, the Zulu royal family sought to compare their standing as a royal family with that of the British royal family. I have suggested that, while in exile on St. Helena, through adopting Western dress and lifestyle, and possibly modelling his family on the British royal family, Cetshwayo’s son, Dinuzulu, intended to present himself and his family in a way that, he considered, might make them eligible for membership in the club of European royal families. Harriette Colenso played a role in facilitating this image, appearing as if a matriarch of Dinuzulu’s family in photographs, which were perhaps intended to display the family as meriting comparison, in their bearing, to the British royal family. The photographs were also, I suggest, intended to convey a strong message regarding the importance of securing the succession to the kingship by heredity of future heirs. This message bears comparison with that conveyed in representations of the British royal family in ways that have extended from the sixteenth century up to the twenty-first century.

Harriette’s efforts on behalf of the Zulu chiefs reflect a continued attempt by her to do everything that she could to help to recover the wreckage of the Zulu kingdom and nation following the Anglo–Zulu war and to protect it from the attempts by the Natal authorities to erode the credibility and legitimacy of its leadership by diminishing the status and authority of the Zulu royal house. Members of the Zulu royal family sought to rescue their nation by restoring the legitimacy of their King. And central to this effort was the vision of the parallel drawn, by them, between the families of Cetshwayo and Queen Victoria. In endorsing and promoting this principle, Harriette not only drew on her extensive campaigning work on behalf of the Zulu people, but she also made use of her acknowledged kinship position within the Zulu royal family.

After his return from exile in St Helena, Dinuzulu’s attempts to gain some recognition of his royal status were quashed by the Natal authorities who also thwarted his attempted overture to the British royal family. Instead, he was to face trial for treason for a second time, a trial during which Harriette was to unequivocally reaffirm her support for the Zulu royal family and the Zulu people. By shaking hands with Dinuzulu in open court she publicly disavowed the settler taboo on personal or intimate contact across the colonial divide. Recognition of her position within the Zulu royal family was perhaps most fully demonstrated by her involvement in resolving the disputed succession of Dinuzulu at his funeral.

For more than three decades, with an alliance strengthened by bonds of kinship and, in the case of Harriette, by a shared Zulu identity, the Colenso family had maintained their support for the Zulu royal family. This support had extended though three Zulu kingships: from the days of Cetshwayo’s capture and imprisonment, with Bishop Colenso as head of the family; then with the leadership of the family changing to that of Harriette, though the treason trials and the exile of Dinuzulu and his uncles in St. Helena, and their return from exile; through Dinuzulu’s second treason trial and exile; and then, at the funeral of Dinuzulu, to the installation of his son, Solomon.