Abstract

Cultural identity and participation play a critical role in understanding culture and its influence on different cultural groups. The Carpatho-Rusyns originate in the Carpathian Rus, which is in the Carpathian Mountains. The Carpatho-Rusyns are a stateless group, and many historically immigrated to other countries. This mixed-method study examines cultural participation and identity among Carpatho-Rusyn descendants (n = 51). Data collection comprised both open-ended and closed-ended survey questions. A link to the survey was shared in Facebook groups that relate to Carpatho-Rusyn culture, genealogy, and history. Closed-ended survey items were analyzed using descriptive statistics, while open-ended items were thematically coded. The findings indicate that most participants do not align with particular Carpatho-Rusyn groups, yet many still uphold cultural traditions, especially related to food and holidays. Qualitative insights emphasize the significance of cultural pride and distinction. Ultimately, this study highlights unique facets of Carpatho-Rusyn heritage and its lasting importance for descendants living in various countries, especially the United States. Finally, this paper concludes with practical implications that center on the importance of developing educational programs, community engagement strategies, and cultural awareness initiatives to preserve and promote the culture.

1. Introduction

The Carpatho-Rusyns are a Slavic-speaking people who originate in Carpathian Rus along the hills of the Carpathian Mountains in Europe (Magocsi 1994, 1995, 2001). In modern times, they primarily occupy the Lemko region in the southeastern area of Poland, northeastern Slovakia, the western, Transcarpathian portion of Ukraine, the Maramures region of north-central Romania (Magocsi 2015), Hungary, Serbia (Földvári 2014), and Croatia (Kokaisl et al. 2023). Additionally, Carpatho-Rusyn land has been under the control of various nations throughout history including Hungary, Poland, the Habsburg monarchy, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union (Michna 2010). As a stateless group, it is difficult to know the exact number of Rusyns (Kokaisl et al. 2023; Magocsi 1995). In addition, some may be uncertain of which ethnicity to indicate on national censuses (Kokaisl et al. 2023). Descendants may be even more uncertain of their ethnicity. For example, in the United States, many Rusyns were officially registered based on citizenship rather than ethnicity (Kokaisl et al. 2023). The Carpatho-Rusyns are also identified by other terminology including Rusnaks, Ruthenians, Lemkos, Carpatho-Russians, Carpatho-Ukrainians (Magocsi 2001), Ruthenes, Uhro-Rusyns, and Podkarpats’ki Rusyny (Carpatho-Rusyn Society n.d.). Additionally, some scholars indicate that there are different Carpatho-Rusyn subgroups including the Lemko, Boyko, Hutsul, and Dolinyan, each with its own cultural identity, dialects, and historical background (Kokaisl et al. 2023). From the mid-19th century until World War I, many Rusyns left their country to seek opportunities abroad (Magocsi 1995). The descendants of the Rusyn ethnic group are dispersed in many countries, with a large proportion living in the United States, Canada (Magocsi 2001), Brazil (Kokaisl et al. 2023), and Australia (Földvári 2014).

There is a paucity of recent research on the cultural participation and identity of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. Most of the publications (e.g., Magocsi 1994, 2001) on the Carpatho-Rusyn people do not include empirical data and focus significantly on the history of the Carpathian Mountain region (e.g., Magocsi 1994, 1995, 2001, 2015; Magocsi and Pop 2005; Michna 2010; Rusinko 2010; Smith 1997), autonomy and identity (e.g., Han 2023; Magocsi 2018), culture (e.g., Best 1990; Boudovskaia 2020, 2021; Cantin 2012; Csernicskó and Ferenc 2018; Pasieka 2021), language (e.g., Koporova 2016; Pugh 2009), and immigration (e.g., Crispin 2006). Rosko (2017) provided valuable insights into the impact of Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants and their descendants on the United States, but the study was not grounded in empirical data. Examining the cultural participation and identity of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants can help promote cultural heritage awareness and traditions in diaspora communities. Moreover, this research underscores the significance of recognizing the diversity and similarities among Carpatho-Rusyn descendants in the broader context of multicultural societies, including the United States and Canada, where individuals may hold several ethnicities. Finally, by exploring how Carpatho-Rusyn descendants maintain connections to their cultural heritage across modern national boundaries, this research can inform discussions and policy on multiculturalism. The purpose of this mixed-method study is to explore the cultural participation and identity of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. The following research questions guided this study:

- How do Carpatho-Rusyn descendants describe their Carpatho-Rusyn cultural participation?

- How do Carpatho-Rusyn descendants describe their Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity?

- What do Carpatho-Rusyn descendants value about Carpatho-Rusyn culture?

- What Carpatho-Rusyn cultural activities do Carpatho-Rusyn descendants participate in?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Carpatho-Rusyn Culture and History

The Carpathian-Rusyn people predominantly live in the Carpathian Mountains where they first settled in the sixth and seventh centuries (Magocsi 2001). They often reside in small villages with just a few hundred people. Their livelihood centers on herding sheep, logging, and agricultural practices. Due to its geographic location in the center of Europe, the Carpatho-Rusyn culture has been influenced by Western (e.g., the Roman Catholic Church) and Eastern European cultures (e.g., the Eastern Orthodox Church). According to Magocsi (2001),

To be so affected by various political and cultural influences is common for a national or ethnic minority living in a borderland region. In this sense, Carpatho-Rusyns know very well the feeling of anguish and diminished identity that accompanies the cultural and historical partitioning that has been the fate of so many European national or ethnic minorities. For Carpatho-Rusyns however, who have not been united in a single province, kingdom, or country for nearly a thousand years, the sense of being at the mercy of others is more acute. (p. 19)

The Carpatho-Rusyn people have endured centuries of cultural and historical divisions that helped to forge a unique cultural identity that has been influenced by its culturally and linguistically diverse neighbors. It is important to note that some Slavic nations have aimed to assimilate Rusyns into the dominant national culture (Kokaisl et al. 2023). Carpatho-Rusyn culture is largely influenced by Christianity with many Greek Catholic and Orthodox adherents. Carpatho-Rusyn Christian traditions originate from the Byzantine Empire and share some similarities with the Christian traditions of Hungary, Poland, and the former Czechoslovakia (Magocsi 2001). The Byzantine Empire largely shaped the Christian traditions of Eastern Europe through its liturgical practices, iconography, and ecclesiastical organization.

Ukraine and Russia, which primarily follow the Orthodox Christian faith, have also influenced the Carpatho-Rusyns through language and religious customs (Magocsi 2001). Although Russia does not directly border Rusyn territory, Russian culture impacted the Carpatho-Rusyn culture through historical and regional interactions. According to John Righetti, President Emeritus of the Carpatho-Rusyn Society, the culture has also been heavily impacted by paganism, folk culture, and superstitions (as cited in Mihalasky n.d.).

Cultural customs and traditions, including food, song, arts, and dance, play a critical role in the lives of the Carpatho-Rusyn people (Magocsi 2001). Popular Rusyn dishes include stuffed cabbage, stuffed peppers, homemade noodles, and pirohi (pierogies); these dishes are common among other eastern Slavic groups (Magocsi 2001). In the Carpatho-Rusyn culture, there are specific foods eaten and traditions practiced during holidays, especially Easter. Hand-painted Easter eggs called pysanky and krashanky with beautiful designs are a major part of Carpatho-Rusyn Easter traditions. The Carpatho-Rusyn Easter eggs with small line strokes or images of human and animal designs can be distinguished from Ukrainian eggs which have shapes all around them (Magocsi 2001). Music also plays an important role among Carpatho-Rusyns. Church services use basic folk songs that are sung by the congregation, which differs from the worship style of Russians and Ukrainians. The latter tend to have more robust arrangements that are led by a choir (Magocsi 2001). Music outside of church and folk dance are also popular, and folk ensembles still perform at special cultural events.

Language is a major facet of Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity. The Carpatho-Rusyn vocabulary shares many similarities with Polish, Slovak, and Hungarian. According to Magocsi (1995), “The very language or series of dialects that Rusyns speak reflect the influences of both cultural spheres. Thus, while their speech clearly belongs to the realm of East Slavic languages, much of their vocabulary, pronunciational stress, and even syntax is [sic] West Slavic” (para. 12). Despite its East Slavic origins, the Carpatho-Rusyn language exhibits a blend of linguistic features that are native to both East and West Slavic languages. Moreover, there are linguistic variations within the Rusyn language, especially in terms of dialect, which differs across Carpatho-Rusyn communities and groups.

The Carpatho-Rusyns lack their own nation and as a result, have experienced many challenges (Magocsi 2001). The Carpatho-Rusyn people have been ruled by different powers throughout history. Under the rule of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, many Carpatho-Rusyns struggled with food insecurity, prompting many to consider options overseas, with the United States and Canada being popular destinations. By World War I, roughly 150,000 Carpatho-Rusyns were living in the United States (Magocsi 2001). However, many ship records and government documents did not list these people as Carpatho-Rusyns but rather as Austrians or Hungarians or the later rulers, which included Czechoslovakia and Poland. This can be problematic for future generations of Carpatho-Rusyns who may not be familiar with their cultural roots due to the different classifications that were used depending on the period.

2.2. Cultural Participation

Cultural participation can be defined as “participation in any activity that, for individuals, represented a way of increasing their own cultural and informational capacity and capital, which helps define their identity, and/or allows for personal expression” (UNESCO 2012, p. 51). Cultural participation provides a wide range of benefits and exposes people to new ideas and beliefs (Stanley 2006). It can also lead to the development of shared values (Council of Europe 2017). There are myriad examples of cultural participation, which can include active forms of participation as well as more passive types (UNESCO 2012). Some specific examples defined by the Eurobarometer (2013) include dancing, music, singing, painting, and theater. There are various forms of cultural participation beyond these examples, and the consumption or enjoyment of culture can also be considered cultural participation (Council of Europe 2017). Nevertheless, defining cultural participation can be problematic since there may not be agreement on the activities to include (Murray 2005).

Morrone (2006) provides a deeper understanding of cultural participation and the measurement of this participation in his guide for the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Morrone highlights the need for cultural participation surveys that are culturally relevant; questions need to be carefully formulated based on the unique features of each culture or country. Examples of cultural participation surveys are included in the guide for the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (Morrone 2006). For example, a survey on Maori cultural participation includes questions on topics such as cultural event participation, learning cultural activities, preserving cultural sites, and promoting culture; additionally, culturally specific terminology is also in the construction of the questions to ensure that the survey is specific to the target cultural group (Morrone 2006). Thus, when constructing cultural participation surveys, the questions need to focus on elements of that particular culture, which may differ from others. For the present study, research experts on Carpatho-Rusyn culture were contacted to get input on the questions.

2.3. Cultural Identity

Cultural identity largely centers on cultural values and practices and how individuals perceive their role in a particular cultural group (Schwartz et al. 2008). Schwartz et al. provide some examples of cultural identity components including acculturation, ethnic identity, roles of individualism versus collectivism, independence and interdependence, familism, filial piety, and communalism. Cultural identity can refer to an aspect of self-identity as well as group identity (Dien 2000). Heritage can also play a critical role in the formation of cultural identity (Segall 1986). Cultural identity has been examined in some geographic contexts; for example, Holliday (2010) examined cultural identity among people of diverse nationalities.

Cultural identity can be complex for Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. For example, when discussing nationalities, it is common for Carpatho-Rusyn Americans to make connections to a specific country such as Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, or Poland, rather than labeling themselves as Carpatho-Rusyn (Magocsi 2001). In the United States, immigration from southern and eastern Europe began to decrease in the 1920s with quotas that restricted people coming from specific areas (Magocsi 2001). Thus, Carpatho-Rusyn immigration began to decline at this time.

Historically, the term Rusyn or Rusniak was used to describe the Carpatho-Rusyn people (Magocsi 1995). During the 1900s, the Rusyns of Ukraine generally referred to themselves as Ukrainian, while the Rusyns of the Presov region of Slovakia typically used the term Lemko (Magocsi 1995). It also became common to identify with the major cultural group of the nation; for example, Carpatho-Rusyns in Poland may identify as Polish and those in Slovakia may identify as Slovaks (Magocsi 1995). There is also disagreement on the designation of these terms (Magocsi 1995), making it difficult to have a clear and specific definition of Carpatho-Rusyns. Magocsi (1995) states that some individuals may use the terms Rusyn, Rusniak, Lemko, or Ukrainian as synonyms, while others perceive them as distinct groups. For this paper, the Carpatho-Rusyn homeland will refer to areas of the Transcarpathian Mountains with historical Carpatho-Rusyn communities. Among the Carpatho-Rusyn descendants in other countries, a wide range of complexities may exist including a lack of awareness of their heritage, a disinterest in cultural participation or identity, and having various ethnic backgrounds, especially among the third and further generations of descendants.

3. Theoretical Framework

Ethnic identity theory proposes that there are different forms of ethnic identity formation. Ethnic identity encompasses many facets of culture and heritage and can evolve (Phinney and Ong 2007). There are three primary stages involved in the ethnic identity theory, which include the following: (1) unexamined ethnic identity, where individuals have not explored their ethnicity; (2) the ethnic identity search, where ethnic identity development begins to form through cultural exploration; (3) ethnic identity achievement, where individuals start to accept and understand their ethnicity (Phinney 1989).

In the first stage, individuals have not explored their ethnicity extensively (Phinney 1989). They may not be aware of their cultural background or its significance in shaping their ethnic identity. For example, a young Carpatho-Rusyn descendant raised in a predominantly mainstream culture may not have consciously considered their Rusyn heritage or its implications for their sense of self. During the second stage, individuals begin to examine and question their ethnic identity. This might involve engaging in cultural exploration and seeking to understand their heritage and cultural traditions on a deeper level (Phinney 1989). For example, a Carpatho-Rusyn descendant might actively seek out information about their cultural heritage, participate in Rusyn cultural events, or engage in discussions with family members about their family history and heritage. In the last stage, individuals have a more solidified and accepting sense of their ethnic identity, integrating their ethnic heritage into their self-identity (Phinney 1989). For example, an adult Carpatho-Rusyn descendant who has actively explored their cultural background and embraced their Carpatho-Rusyn identity may feel a strong connection to their heritage and actively engage in Rusyn cultural activities, celebrations, and community events.

Ethnic identity theory can be applied to this study to better understand how cultural identity is passed down through generations. Through the lens of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants’ experiences and perceptions, deeper insights can be uncovered about their ethnic identity and participation. Moreover, Phinney and Ong (2007) indicate that to deeply understand ethnic identity, it is important to explore one’s ethnic identity in relation to the dominant, mainstream culture. For example, this might involve Carpatho-Rusyn descendants in Canada, the United States, or Australia defining their identity in light of the mainstream national culture and their distinct ethnic identity or identities.

Another theory that is connected to this study is Gans’ (1979) theory of symbolic ethnicity. Gans’ theory, which was developed decades ago, still holds value in the modern discussion of ethnic identity and participation. Symbolic ethnicity centers on the concept of pride or affection for a particular culture without necessarily being directly involved in the culture on a daily basis. According to Gans (1979), “While ethnic ties continue to wane for the third generation, people of this generation continue to perceive themselves as ethnics, whether they define ethnicity in sacred or secular terms” (p. 7). In this study, the authors were interested in exploring potential differences in ethnic identity and participation based on generational differences, especially now with fourth and fifth generation participation among Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. In the past, ethnic identity was often taken for granted, with people generally living in ethnic neighborhoods and working with people of similar ethnicities. With third and future generations, these direct connections to the culture may have diminished over time.

4. Methodology

Permission was first obtained from the authors’ university institutional review board to conduct the study. A brief overview of the study’s purpose and a link to the informed consent form and survey were posted on relevant Facebook groups pertaining to Carpatho-Rusyn culture, history, and genealogy. The consent form and survey were linked through Google Forms. A brief overview of the study was provided as well as a link to the informed consent form and survey. Those who agreed to participate in the study signed the informed consent form through JotForm and completed the survey. The study commenced in June 2022 and continued until the last week of August 2022. Information about the study was posted a total of three times at monthly intervals.

The population included Carpatho-Rusyn descendants who were at least 18 years of age and identified as a Carpatho-Rusyn descendant. Purposive sampling (Creswell and Creswell 2017) was used to select participants who identified as Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. Participants were identified, approached, and recruited based on membership in a Carpatho-Rusyn Facebook group on Carpatho-Rusyn culture, genealogy, or history. Additionally, snowball sampling was used to recruit additional participants who may or may not have belonged to the Facebook groups.

This study employed a convergent mixed-method design in which qualitative and quantitative data were examined simultaneously (Creswell and Plano Clark 2017). Closed- and open-ended survey questions relate to Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity and cultural participation (see the Appendix A). The closed-ended survey questions collected information on participants’ backgrounds, including their citizenship, residency, and generational status as Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. Closed-ended survey questions also addressed aspects of Carpatho-Rusyn identity, Rusyn language proficiency, and engagement in cultural activities (e.g., attending Rusyn church, participating in cultural organizations, and celebrating traditional customs). Participants could also provide additional comments about their Carpatho-Rusyn cultural participation and identity through open-ended survey questions. The survey was adapted from similar cultural participation and identity surveys (e.g., Eurobarometer 2013; Morrone 2006). In addition, input was obtained from a leading Carpatho-Rusyn expert and a statistician. Several modifications were made to ensure that the most distinct aspects of Carpatho-Rusyn culture were addressed in the survey. Additionally, the wording of several questions was changed, examples for several questions were provided in parentheses, and clarification was provided on questions related to generational classifications. Ethical considerations were also considered to ensure the wording of the questions was respectful and sensitive. Questions were written in English, which is the global language. In addition, many Carpatho-Rusyn descendants live in dominant English-speaking countries such as the United States and Canada.

5. Reflexivity

The first author of this paper identifies as an ethnic Carpatho-Rusyn descendant and had some exposure to Carpatho-Rusyn traditions, especially through attendance at a Rusyn church in the United States. As a fourth-generation Carpatho-Rusyn American, the first author did not have strong ties to the Carpatho-Rusyn homeland but learned about some of the traditions that had been passed down through the generations. The first author also spent a significant amount of time studying family history, which involved learning more about the Rusyn people. The generational distance from the Carpatho-Rusyn homeland further influences cultural practices and identity interpretation. Reflexivity was a continual process as the first author reflected on how her personal background and experiences could impact the development of research questions, data collection, and thematic analysis. The additional authors of the paper do not have any personal ties to the Carpatho-Rusyn culture, which helped to provide a more objective interpretation of the data.

6. Participants

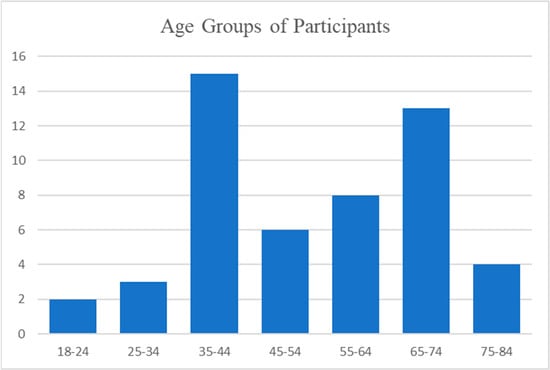

In terms of country of citizenship, participants were from Australia (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Croatia (n = 1), the Philippines (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), and the United States (n = 43). Two participants did not respond to the citizenship question. Countries of residency were reported as the same as countries of citizenship. Although there were only 51 participants in this study, the survey was posted several times in major groups on social media pertaining to Carpatho-Rusyn culture. Snowball sampling was also used. The research team had hoped to obtain a larger sample; however, we understood that many descendants of Carpatho-Rusyns may not even be aware of their ethnic identities. Moreover, finding participants outside of social media groups would be difficult to identify. Figure 1 displays the age groups of participants.

Figure 1.

Age groups of participants.

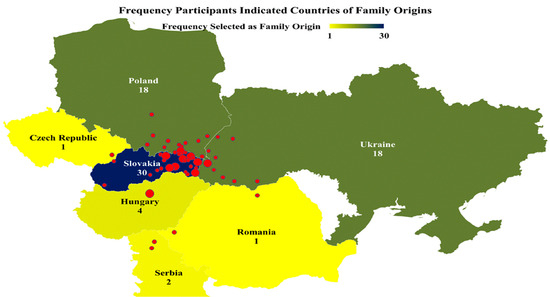

Additionally, 70% (n = 36) of participants identified as female and 30% (n = 15) identified as male. In terms of Carpatho-Rusyn generational identification, 4% (n = 2) of participants classified themselves as fifth-generation Carpatho-Rusyns, while 44% (n = 22) of participants classified themselves as fourth-generation descendants, 32% (n = 16) as third generation, 14% (n = 7) as second generation, and 2% (n = 1) as first generation. In addition, 4% (n = 2) stated that they did not know their generation level. The question was defined for participants and stated that first generation means you are a Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant living in another country, while second generation means you are the son or daughter of a Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant living in another country. All but one participant (n = 50) listed the origins of their Carpatho-Rusyn family, with some giving vague responses and others giving more specific locations. The participants were asked to provide the locations based on the current map of Europe. Figure 2 includes the locations indicated by the participants. Some participants provided several locations in more than one present-day country.

Figure 2.

Origins of Carpatho-Rusyn family based on the modern map of Europe. The numbers below each country represent the number of identified origins of Carpatho-Rusyns. Some participants only indicated countries rather than cities, towns, or villages based on the modern map of Europe. Larger circles represent a larger number of responses for a particular location.

7. Data Analysis

Closed-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Thematic coding procedures were employed to analyze the qualitative data (Braun and Clarke 2019). The researchers systematically coded the open-ended question responses and identified recurring themes and subthemes that holistically represented the essence of the data. Manual coding was initially conducted, followed by the use of the Dedoose software program, which was used to refine codes further. The qualitative results complemented the quantitative data, providing a deeper awareness of the experiences and perceptions of the participants.

8. Quantitative Results

8.1. Carpatho-Rusyn Cultural Identity

In terms of cultural identity, participants were asked if they identified with any specific Carpatho-Rusyn group (e.g., Dolinyans, Boykos, Hutsuls, Lemkos, etc.). Among participants, 64.7% (n = 33) do not identify with a specific group, while 33.4% (n = 18) identify with a specific Carpatho-Rusyn group; 10 participants stated that they identify as Lemko, one as Hutsul and Lemko, one as Lemko and Boyko, two as Presov region Rusyn, two as just Carpatho-Rusyn, and one as Zamieszancy (people living in the Carpatho-Rusyn region). Participants were also asked if anyone in their immediate family (parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and great-grandparents) identified as Carpatho-Rusyn; 82.4% (n = 42) stated yes and 17.6% (n = 9) responded no.

8.2. Carpatho-Rusyn Cultural Participation

Participants were asked about their language abilities in speaking Rusyn as well as reading Cyrillic and Latinika. Among participants, 80.4% (n = 41) do not speak Rusyn and 19.6% (n = 10) do. Of the ten who speak Rusyn, two indicated that they are native-like, four are intermediate level, and six are beginner level. In terms of reading abilities, 54.9% (n = 28) indicated that they could read Cyrillic and 29.4% (n = 15) could read Latinika.

In terms of having contact with Rusyn friends or family in European countries (e.g., Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Czechia/Czech Republic, etc.) that have a high number of Rusyn people, 54.9% (n = 28) stated that they do, and 45.1% (n = 23) indicated that they grew up in a Rusyn community outside of the Rusyn homeland.

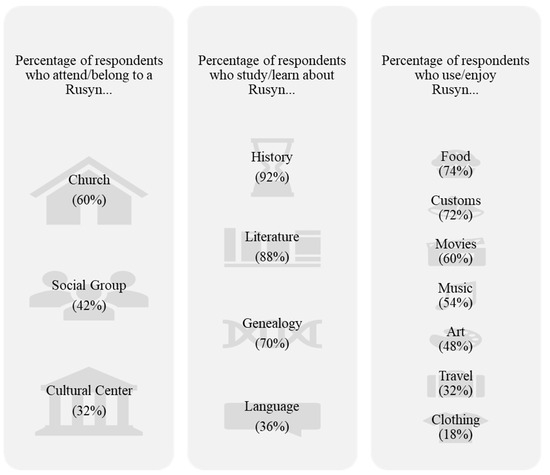

Figure 3 and Table 1 provide cultural participation data among Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. Figure 3 centers on the results of the question: Which of these activities have you participated in? Table 1 displays the results of the question: Which of these activities do you participate in at least a few times annually?

Figure 3.

Cultural activity participation.

Table 1.

Cultural participation activities that take place at least a few times annually.

Table 1 includes the same items as indicated in Figure 3. However, the survey question asked the participants to mark the activities that are performed at least a few times annually. The activities that at least half of the participants reported doing at least a few times annually include reading books or articles about Rusyn culture (69.4%), keeping Rusyn holiday customs (65.3%), cooking Rusyn food (67.3%), learning about Rusyn history (53.1%), and studying Rusyn genealogy (53.1%).

9. Qualitative Results

9.1. Ancestral Connection and Cultural Practice

The proceeding section reports the qualitative findings of the study. The first significant theme is ancestral connection and cultural practice, with the following subthemes representing cultural identity: ancestry and traditions, cultural pride and distinction, and cultural cuisine as heritage.

Ancestry and Traditions. In terms of what Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity means to the participants, a dominant subtheme is having a connection to ancestry and traditions. Exploring Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity indicates a passion for cultural practices, family connections, and discovering ancestral roots. For example, one participant noted, “Being part of a minority ethnicity which never had a country except for 1-day. It’s the connection to my ancestors. It’s having things in common with people currently living in Eastern Europe” (fifth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). Another participant elaborated on the importance of her Carpatho-Rusyn heritage. She stated,

It means I have a heritage of strong people and a strong ethnic heritage. From what I can tell, my mom’s side is 100% Carpathian Rusyn and my dad’s is at least partly. They both grew up in the Pittsburgh area, but I did not. I called my mom’s parents baba and dzedo. My parents and I planned to take a trip to visit Slovakia, Ukraine, and Poland in May 2020, but then COVID happened and now a war. (Fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident)

Participants expressed a sense of identity through their heritage by connecting their cultural practices and family histories to broader themes of resilience and continuity amidst historical and contemporary challenges.

Participants also indicated that they grew up thinking that they were other ethnicities. For example, one stated that she had been told she was Slovak rather than Rusyn. “Learning the truth made me feel like I finally KNOW who I am” (second generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). Another participant highlighted the importance of learning about her ethnic identity: “For me it means connection to those who came before me and learning about and respecting their past experience. I didn’t grow up knowing I was Carpatho-Rusyn so learning this has been an ongoing educational journey” (fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident).

Cultural Pride and Distinction. Another subtheme that was extrapolated from the data is cultural pride and distinction. Participants discussed the need to distinguish Rusyns from Russians. For example, one participant (second generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident) stated, “I find it exhausting to find so many Rusyns who identify as Russians... Somehow the Rusyn community has no pride in itself.” Another participant expanded on the historical issues that have permeated the Rusyn culture, which has led to problems in defining Rusyn identity:

To retain the cultural identity and traditional rituals and most importantly the language as throughout the centuries of oppression, repression and attempted assimilation have many Rusyns not aware or knowing who they are. (Second generation, female, country of citizenship/residency not identified)

Another participant (fourth generation, male, U.S. citizen/resident) indicated that “Rusyn culture is priceless because it is a traditional culture centered around faith and family.” He also indicated that the culture is distinct but mentioned the cultural connections to Ukraine.

A similar response was reiterated by a fourth-generation male who identifies as a U.S. citizen/resident: “This is something that I have learned about over the course of the last decade... When someone asks me about my heritage, I will often answer Ukrainian if a quick, simple answer is required, but I am always happy to talk about the intricacies with someone if they are interested.”

Cultural Cuisine as Heritage. In addition to broad connections to cultural identity, a major focus of responses was on the importance of Carpatho-Rusyn food. A specific emphasis was placed on the importance of holiday foods, particularly Easter foods. For example, one participant highlighted the significance of Easter foods:

Rusyn cultural identity is rooted in American Russian Orthodoxy, but more cultural than religious. Easter food traditions like a butter lamb, hrudka in cheesecloth hanging over the sink to drain, red-dyed eggs, and my grandfather’s handmade wooden mold for sirnaya paska. red dyed eggs… Getting the Easter basket blessed. Slicing off the four corners of the pascha bread (even though the bread is round). (Fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident)

Other examples provided included general foods customarily made by Carpatho-Rusyns including pierogies (with different variations of the spelling provided) and halupki (stuffed cabbage). The food traditions highlight specific examples of cultural transmission with more recent generations of Carpatho-Rusyns having familiarity with the food culture. Passing down recipes and traditions surrounding food helps to preserve a distinct and important component of Carpatho-Rusyn culture.

9.2. Exploring Ancestral Heritage and Experiences

The next section thematically examines the primary results related to the participants’ awareness of their Carpatho-Rusyn ancestors. The following subthemes will be discussed: ancestral journeys and origins: hard work, resilience, and religion; and challenges in ancestral knowledge.

Ancestral Journeys and Origins: Hard Work, Resilience, and Religion. Participants mentioned knowing about their ancestors’ migration stories and learning about the homelands of their ancestors. They discussed their ancestors leaving the homeland to escape poverty and immigrating to the United States for a better life. The term “peasant” was used in some responses to discuss their ancestors’ social position in the homeland. Another common term used to describe ancestors was “hard-working.” For example, one participant stated, “They [her ancestors] were very hard-working and came to this country to escape the extreme poverty of Eastern Europe at the time” (fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). Other participants provided specific accounts of what they learned about their ancestors’ journeys to the United States. For example, one participant indicated,

All four great-grandparents on my mom’s side emigrated to the U.S.A. in the early 20th century (between 1907 and 1912). I’ve found some information online (Ellis Island records, a couple Ancestry.com documents). I have family anecdotes from my mom and her sister. We have a good amount of photos and stories from more recent years than the initial emigration.

Participants expanded on their knowledge of their ancestors’ lives, with accounts of stories of immigration to the United States being highlighted. For some, this knowledge was passed down through the generations, and for others, they learned about their ancestors’ lives in the United States through genealogical research. One participant stated, “What I know has been learned through my own research. I know which villages they are from, what their religion was in the homeland and in the U.S.” (Fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). Another had a similar response: “I know approximately when they [his ancestors] came to the U.S. and what kind of jobs they worked. I know where they worshipped. Mom collected all sorts of stuff.” A fourth-generation, male, U.S. citizen/resident indicated that per his baba (grandmother), they were to identify as American first and then Rusyn or other ethnicities, which caused some of the culture to disappear over the generations. Some participants mentioned that their ancestors worked in the coal mines in the United States. A participant (fourth generation, male, U.S. citizen/resident) elaborated on what he knew about his Carpatho-Rusyn family. He stated, “My family knows our history very well. My great-grandfather came to America and very quickly decided the coal mines of Pennsylvania were not for him. He got a job unloading ships in Connecticut and became a founder of a Rusyn church.”

Participants also discussed the role of religion in the lives of their Carpatho-Rusyn ancestors. For example, one participant mentioned that his great grandfather co-founded an Orthodox church in Pennsylvania. Another participant stated that her paternal grandfather was a proud Lemko and helped other Lemkos, especially during the Great Depression. She said that he was very religious and helped found a local church in the U.S. and in Poland. Participants discussed the importance of Orthodox and Greek Catholic Christian traditions in their ancestors’ daily lives and the connections to holiday traditions, especially during Easter and Christmas.

Finally, participants also provided general details on where their family members originated and how they got to the United States. Some participants indicated that they had visited their ancestors’ homelands or intended to. For example, one stated, “I’ve been researching this (her Rusyn ancestors) for years now. I visited the villages of both grandparents in Ukraine in September 2021” (third generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). Participants reflected on what they had learned about their ancestors’ difficult migration to other countries, with most representation coming from the United States, and some indicated a desire to return to their ancestors’ homeland to further enrich their understanding of Carpatho-Rusyn culture.

Challenges in Ancestral Knowledge. Although participants provided insights into what they knew about their Carpatho-Rusyn ancestors, a common theme was a lack of ancestral knowledge among the participants. One mentioned hiring a translator 20 years ago who helped him learn more about his ancestors. Another participant (third generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident) indicated that she learned the term “Po Nashomu” or “people like us.” She said that the older generation is gone and that her generation is elderly. She said, “Family customs were lost due to poverty. My grandfather was a coal miner in Pennsylvania. 11 kids, 22 grandchildren.” Another participant indicated, “At this point, it [Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity] means very little. I was placed in foster care/adopted and just recently discovered my maternal roots.” (Second generation, male, U.S. citizen/resident). A more detailed account was provided by a fifth-generation male who is a U.S. citizen/resident. When asked about what he knows about his Carpatho-Rusyn ancestors, he stated,

Not much, thanks to time passing, poor record keeping, and century-old family conflicts. My Roman Catholic Slovak great-great grandma and her sisters were both married off to older Greek Catholic Rusyn men in Pittsburgh in the late 19th Century. My great-great-grandpa soon abandoned his new family, and disappeared, becoming nothing more than a faceless, half-remembered name, as everyone knew him was dead by the 70s. I’ve managed to find out more about his life, find his home village, siblings, parents, cousins, etc. but it’s all still pretty vague.

Participants also mentioned a lack of interest among other family members in learning about their Carpatho-Rusyn heritage. For example, one participant (fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident) stated, “Many of my cousins are not interested in our Carpatho-Rusyn heritage. One of my cousins identifies as Slovak because our distant relatives from Slovakia visited; she does not seem to understand the difference between citizenship (or nationality) and ethnicity.” The discussion of challenges in ancestral knowledge among Carpatho-Rusyn participants indicates several significant obstacles in fully understanding and preserving their cultural heritage. This especially stems from a lack of access to reliable and detailed information about the participants’ Carpatho-Rusyn ancestors.

9.3. Preserving Carpatho-Rusyn Culture: Heritage, Resilience, and Faith

Participants were asked to discuss what they value about Carpatho-Rusyn culture. The responses centered on heritage, resilience, and faith. The following subthemes pertain to valuing Carpatho-Rusyn culture: cultural identity and customs, resilience through identity, and religious heritage and traditions.

Cultural Identity and Customs. The following section highlights the role of cultural identity and customs in the lives of the participants. Participants discussed core values and traits, connections with heritage and identity, the value of the community, and the desire for recognition and a stronger understanding of the culture. Various values and traits that embody the Carpatho-Rusyn culture mentioned include diligence, honesty, integrity, frugality, acceptance, and artistic qualities. One participant indicated that she claimed Carpatho-Rusyn ancestry on the U.S. 2020 Census and was curious if other descendants did.

Resilience through Identity. This section examines aspects of Carpatho-Rusyn identity and the resilience of the community in maintaining its distinct cultural heritage during historical and political challenges. The need to differentiate between Rusyns and Russians was discussed. One participant indicated that he never uses the term Rusyn but rather Carpathian to distinguish Rusyns from Russians. Participants also mentioned the impact of other cultures and neighboring countries on Carpatho-Rusyn identity and resilience. For example, one participant discussed “the strengths of Rusyns in keeping their identity despite other countries’ constant attempts to assimilate them into their identity” (second generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). A similar response was provided by another participant: “I value the fact that as a people we kept alive our ways in the midst of the surrounding cultures that often had political control of the region” (fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident). Additionally, several participants discussed the impact of the war in Ukraine on visiting their ancestral homeland. Although the paper focuses on Rusyn’s identity, it is worth stating that some participants also expressed support for Ukraine in the context of current events with phrases such as “Slava Ukraini.” Participants highlighted the cultural preservation of the Carpatho-Rusyns and the need to distinguish the Rusyn culture from other cultures, especially Russian.

Religious Heritage and Traditions. Through personal reflections, participants discussed connections to Orthodox Christian and Greek Catholic traditions, from observing holidays such as Good Friday to the practice of exchanging gifts on 7 January. Additionally, these examples emphasize the distinctiveness of Carpatho-Rusyn Christianity, emphasizing the role of community and tradition. One participant discussed the impact of religion on her upbringing in detail and how she celebrated Orthodox Christmas and got married in the Orthodox Church.

I grew up in an area with lots of Greeks, so I never had to explain in depth why I was leaving school early on Orthodox Good Friday. Then responding to “Christos Anesti” with “Voistinu Voskrese” on Bright Monday. Learning to read Church Slavonic so that I could sing in the choir when I was a kid. My mom and I saving [sic] a small gift for each other on 7 January, not 25 December. Getting married in the Orthodox Church and my maid of honor accidentally whacked me in the head with the crown. (Fourth generation, female, U.S. citizen/resident).

Another participant elaborated on the role of Rusyn Christianity and its connections to major cultural traditions. He stated that the religion is not “tainted by nationalism” and heavily focuses on the role of tradition in the church. This concept of tradition in religion was expressed by other participants. One indicated that it “represents a simpler time without modern distractions and is a way of reflecting on everyday life. And awareness and practice of it is becoming increasingly rare which makes it even more valuable to learn and perpetuate” (third generation, male, U.S. citizen/resident).

Overall, the results indicate that Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity is deeply rooted in ancestral connections, cultural practices, and a commitment to preserving heritage. These facets of culture and ancestral connection contribute to a deeper sense of identity among participants, despite generational differences in terms of cultural participation and cultural identity. Some participants indicated challenges, however, especially in terms of awareness of their ancestors and heritage.

10. Discussion

Participants discussed a connection to their Carpatho-Rusyn heritage, and many could identify their ancestors’ origins in different parts of the Carpathian Mountains. Participants also expressed a sense of cultural pride and distinction and emphasized the importance of maintaining Carpatho-Rusyn cultural heritage. This view was more pronounced in terms of participants’ desire to differentiate Rusyn from Russian identity. This could stem from historical misunderstandings since some Rusyns were identified as Russians and other groups (Rosko 2017). Rusyns were also often classified based on citizenship rather than nationality (Kokaisl et al. 2023). In addition, many Rusyns were misidentified in U.S. censuses and were classified as Russian due to the similarity in the sounds of Rusyn and Russian (Center for Public History + Digital Humanities 2024). Some Rusyns also joined Russian Orthodox churches and self-identified as Russians rather than Rusyns. Moreover, resilience was discussed, especially in terms of preserving cultural traditions despite historical challenges. The study revealed diverse forms of cultural participation among Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. These examples range from learning about Carpatho-Rusyn history and genealogy to practicing holiday customs and cooking traditional foods. Additionally, participants shared values related to the Carpatho-Rusyn cultural identity. Cultural participation can have a strong impact on the development of shared cultural values (Council of Europe 2017). Even though language proficiency in Rusyn was relatively low, there was a notable degree of interaction with some cultural activities including attending Rusyn churches, researching genealogy, and preparing Rusyn foods. The findings of this study underscore the importance of maintaining cultural practices in fostering a sense of belonging and ethnic identity among Carpatho-Rusyn descendants.

The qualitative findings underscore the significance of ancestral connections, cultural pride, and traditional practices. Overall, participants expressed a strong sense of connection to their Carpatho-Rusyn roots through explorations of ancestry, traditions, and family narratives, with some degree of cultural continuity across generations. However, first- and second-generation participants indicated a deeper connection to the culture. As Schwartz et al. (2008) indicated, cultural identity largely focuses on cultural values and practices and how individuals perceive their roles concerning the culture. The findings also indicate how third- and fourth-generation Carpatho-Rusyns experience ethnic identity as symbolic by maintaining a sense of connection to their ancestors through traditions, food, and ancestry despite diminished direct cultural practices that first- and second-generation Carpatho-Rusyns may have experienced. This aligns with Gans (1979), who decades ago discussed symbolic cultural identity’s role in more distant generations that are not as directly involved in the culture. Participants exhibited varying levels of awareness regarding their Carpatho-Rusyn ancestors. Some participants provided detailed migration stories, and others mentioned gaps in historical knowledge. Despite challenges such as acculturation into a dominant culture such as U.S. culture and the loss of family traditions over time, participants expressed admiration for their ancestors’ resilience and perseverance in maintaining Carpatho-Rusyn cultural traditions. The concept of historical and cultural resilience emerged in participants’ reflections. Cultural pride emerged as a significant response. Participants mentioned advocating for recognition and distinction from other ethnic groups. Moreover, the importance of Carpatho-Rusyn food, particularly holiday traditions, highlights the role of culinary heritage in shaping ethnic identity. However, a major theme of limited awareness and understanding among some descendants indicates the importance of educational initiatives and community engagement to ensure the preservation and appreciation of Carpatho-Rusyn culture for future generations.

To better understand this study within the context of ethnic identity theory (Phinney 1989; Phinney and Ong 2007), future research might center on the specific experiences and challenges faced by Carpatho-Rusyn descendants at each stage of ethnic identity development. This might entail exploring factors such as the transmission of cultural practices over the generations. In addition, examining the intersectionality of ethnic identity with other aspects of identity, such as ethnic or racial identities (especially for those living in multicultural countries), socioeconomic status, and geographic location, could provide a more holistic understanding of the complexities inherent in the development of cultural maintenance.

In terms of implications, this study provides insights into the significance of cultural preservation and, specifically, the Carpatho-Rusyn heritage, especially in diaspora communities and with each generation (e.g., third, fourth, fifth, and beyond) that is more removed from its Carpatho-Rusyn roots. Although this study was open to Carpatho-Rusyn descendants worldwide, most participants were U.S. citizens and residents. In addition, the state of Pennsylvania was mentioned frequently, which is where most Rusyns immigrated to in the United States (Kokaisl et al. 2023). The United States is a highly multicultural country, and Carpatho-Rusyn descendants, especially of the third+, will likely have other ethnic identities. Cultural exploration and immersion may become more time consuming and complex if individuals want to learn about other cultural identities. Furthermore, exploring how Carpatho-Rusyn descendants maintain cultural connections can provide deeper insights into their participation in activities, holidays, and other traditions. This knowledge can be beneficial to local and national cultural organizations that aim to promote and maintain cultural heritage. In the United States, for example, there are local Carpatho-Rusyn cultural chapters as well as larger national organizations. Local and national Carpatho-Rusyn organizations in the United States have hosted events over the last several decades to raise awareness of Carpatho-Rusyn studies (Rusinko and Horbal 2019). Gaining deeper insights into the cultural participation and identity of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants can help inform educational programs and activities. Finally, participants mentioned having either visited their ancestors’ homelands or wanting to in the future. This study could provide suggestions for tourism strategies to attract more visitors to the Carpathian region.

11. Conclusions

This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the enduring legacy of Carpatho-Rusyn culture among diasporic communities, with a large focus on U.S. citizens/residents who identify as ethnically Carpatho-Rusyn. Although this study provides valuable insights into the experiences of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants, it is not without limitations. The stories passed on from generation to generation can sometimes be skewed or completely inaccurate. There are many historical inaccuracies and complexities pertaining to the Carpatho-Rusyn people. The national boundary changes in this territory of Europe in history make it difficult for some Carpatho-Rusyn descendants to even know that they may be Carpatho-Rusyn when their origin may have been listed as Czechoslovakia, Austria-Hungary, Slovakia, or other countries. Additionally, participants were recruited from Carpatho-Rusyn social media groups, which likely do not represent the entire population of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants. Individuals who are not active on social media or are not strongly connected to their Carpatho-Rusyn heritage may not have been included in this research. This study was also conducted in English, which may have made it difficult for non-native English speakers to accurately convey their experiences and perceptions. The structure of the research sample, which includes mostly U.S. residents, reflects the demographic distribution of accessible participants and may be impacted by factors such as language barriers and recruitment methods. Furthermore, qualitative research was limited to open-ended responses, limiting rich data that could be obtained through interviews or focus groups.

Future research should aim to study a larger number of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants to obtain more quantitative data. In addition, in-depth interviews with Carpatho-Rusyn descendants could help to gain more insight into cultural identity and cultural participation. Perhaps, first- and second-generation descendants may be able to provide more detailed stories about their connections to the culture since they may be more likely to know about or have ancestors who grew up in the Carpatho-Rusyn homeland. Furthermore, examining differences among generational degrees could provide valuable insight into whether fourth- or fifth-generation Rusyn descendants share the same degree of participation and identity as first-, second-, or third-generation descendants. It would also be beneficial to explore Rusyn descendants in different geographic regions, especially those with a defined Rusyn community presence. Carpatho-Rusyn Americans dominated this study. Future research could focus more specifically on the experiences of Carpatho-Rusyn Americans. In addition to examining the cultural participation and identity of Carpatho-Rusyn descendants, it is critical to explore the experiences of the Carpatho-Rusyns who live in the traditional homeland area of the Carpathian Mountains. Finally, it would also be valuable to gain insight into the cultural identities and cultural participation of the Carpatho-Rusyn people and examine the intersectionality of national (e.g., Ukrainian, Polish, Slovak) or other cultural identities in their experiences.

Author Contributions

A.R.L. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing (original draft preparation), and writing (reviewing and editing). N.R. contributed to the conceptualization and writing (original draft preparation). P.C.S. contributed to the methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing (original draft preparation), and writing (reviewing and editing). J.R.M.III contributed to the methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing (original draft preparation), and writing (reviewing and editing). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Austin Peay State University (protocol code 22_033, 31 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rich Custer for assisting with survey development and Beata Waluto for providing valuable resources on the Carpatho-Rusyns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Rusyn Cultural Participation and Identity Survey

By completing this survey, I indicate that I identify as an ethnic Rusyn and that I am at least 18 years old.

- Country/Countries of Citizenship: Type in the box (you may leave blank if you prefer not to say)

- Country of Residency: Type in the box (you may leave blank if you prefer not to say)

- What is your age?18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+, Prefer not to say

- Gender: (Open-ended)

- What generation Rusyn are you? In this case, first generation means you are a Rusyn immigrant living in another country; second generation means you are the son or daughter of a Rusyn immigrant living in another country.First generation, Second generation, Third generation, Fourth generation, Fifth generation, Do not know, Prefer not to say

- Where does your Rusyn family originate based on the current map of Europe? You can include villages, towns, or countries (if you are uncertain about the exact location). Do not know, Prefer not to say

- Do you identify as any specific Rusyn group (e.g., Dolinyans, Boykos, Hutsuls, Lemkos, etc.)? No, Yes, Do not know, Prefer not to sayIf so, what group do you identify as?

- Can you speak the Rusyn language? No, Yes, Prefer not to sayIf yes, what is your level? Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, Native-Like, Prefer not to say

- Can you read Cyrillic? No, Yes, Prefer not to say

- Can you read Latinika? No, Yes, Prefer not to say

- Do you have any contact with Rusyn friends or family in European countries (e.g., Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Czechia/Czech Republic, etc.) that have a high number of Rusyn people? No, Yes, Prefer not to say

- Did you grow up in a Rusyn community outside the Rusyn homeland [if in the U.S., Canada, etc.]—e.g., in a Rusyn church community, in a town or area with many other Rusyn Americans, among extended family of Rusyn relatives?

- Does/did anyone in your immediate family (parents, aunts, uncles, grandparents, great-grandparents) identify as Rusyn [e.g., Carpatho-Rusyn, Carpatho-Russian, Lemko, etc.]

The questions below will have an option to not answer.

- 14.

- What does Rusyn cultural identity mean to you?

- 15.

- What do you know about your Rusyn ancestors?

- 16.

- What do you value most about Rusyn culture?

- 17.

- Have you participated in any of the following forms of Rusyn culture?

- Attending a Rusyn church

- Belonging to a Rusyn cultural organization or fraternal organization

- Visiting a Rusyn cultural center

- Learning about Rusyn history

- Reading books or articles about Rusyn culture

- Watching documentaries about Rusyn culture

- Studying Rusyn genealogy

- Visiting areas with significant Rusyn populations in European countries (e.g., Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Czechia/Czech Republic, etc.)

- Cooking Rusyn food

- Listening to Rusyn music, singing in a Rusyn-related church choir or serving as a cantor, performing (singing/dancing) in a Rusyn or other folk ensemble that includes a Rusyn repertoire

- Keeping Rusyn holiday customs

- Learning/using the Rusyn language

- Wearing traditional Rusyn clothing

- Making Rusyn folk art (e.g., pysanky, embroidery, wood carving)

- Other _______ (please indicate)

- 18.

- For the items checked in #18, which do you do at least a few times annually?

- Attending a Rusyn church

- Belonging to a Rusyn cultural organization or fraternal organization

- Visiting a Rusyn cultural center

- Learning about Rusyn history

- Reading books or articles about Rusyn culture

- Watching documentaries about Rusyn culture

- Studying Rusyn genealogy

- Visiting areas with significant Rusyn populations in European countries (e.g., Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Czechia/Czech Republic, etc.)

- Cooking Rusyn food

- Listening to Rusyn music, singing in a Rusyn-related church choir or serving as a cantor, performing (singing/dancing) in a Rusyn or other folk ensemble that includes a Rusyn repertoire

- Keeping Rusyn holiday customs

- Learning/using the Rusyn language

- Wearing traditional Rusyn clothing

- Making Rusyn folk art (e.g., pysanky, embroidery, wood carving)

- Other _______ (please indicate)

- 19.

- Feel free to write any additional comments you may have related to Rusyn identity or cultural participation.

References

- Best, Paul J. 1990. The Lemkos as an ethnic group. Polish Review 35: 255–60. [Google Scholar]

- Boudovskaia, Elena. 2020. They went to Poland to see wise people: The historical border and magic in stories from a Carpatho-Rusyn village. The Slavic and East European Journal 64: 612–30. [Google Scholar]

- Boudovskaia, Elena. 2021. COVID-19 narratives in a Carpatho-Rusyn village in Transcarpathian Ukraine. Folklorica 24: 51–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantin, Kristina M. 2012. Peak Experiences and Hegemony Resistance: Cultural Models of a Good Life and Group Identity in Carpathian Rus. Ph.D. dissertation, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/e3e18825c29a889b1a9faba3bed41c5f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Carpatho-Rusyn Society. n.d. Who Are the Rusyns? Available online: https://c-rs.org/Who-are-the-Rusyns (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Center for Public History + Digital Humanities. 2024. Russian or Rusyn. Available online: https://clevelandhistorical.org/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Council of Europe. 2017. Cultural Participation and Inclusive Societies: A Thematic Report Based on the Indicator Framework on Culture and Democracy. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/cultural-participation-and-inclusive-societies-a-thematic-report-based/1680711283 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Creswell, John W., and David Creswell. 2017. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crispin, Mercedes Sowko. 2006. The Carpatho-Rusyn Immigrants of Pennsylvania’s Steel Mills. Master’s thesis, Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA, USA. Available online: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/z890rw556 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Csernicskó, István, and Viktória Ferenc. 2018. Hegemonic, regional, minority and language policy in Subcarpathia: A historical overview and the present-day situation. Nationalities Papers 42: 399–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dien, Dora Shu-fang. 2000. The evolving nature of self-identity across four levels of history. Human Development 42: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurobarometer. 2013. Cultural Access and Participation. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1115 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Földvári, Sándor. 2014. Rusyns in the aspect of security politics. Cultural Relations Quarterly Review 1: 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gans, Herbert J. 1979. Symbolic ethnicity: The future of ethnic groups and cultures in America. Ethnic and Racial Studies 2: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Chris. 2023. On history, peoples, and sovereignty. Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 31: 607–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, Adrian. 2010. Complexity in cultural identity. Language and Intercultural Communication 10: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokaisl, Petr, Andrea Štolfová, Pavla Fajfrlíková, Veronika Němcová, Jana Zychová, Irena Cejpová, Tereza Braunsbergerová, Kristýna Došková, Veronika Fučíková, Šárka Hlaváčková, and et al. 2023. In the Footsteps of the Rusyns in Europe: Ukraine, Slovakia, Serbia, Poland, and Hungary. Prague: Nostalgie Praha. [Google Scholar]

- Koporova, Kvetoslava. 2016. Rusyn language on the border of Slovak-Ukrainian linguistic contacts. Typology and Functions of Linguistic Units 2: 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. 1994. Our People: Carpatho-Rusyns and Their Descendants in North America, 3rd ed. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. 1995. The Rusyn Question. Available online: http://litopys.org.ua/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. 2001. The Carpatho-Rusyn Americans. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. 2015. With Their Backs to the Mountains: A History of Carpathian Rus’ and Carpathian-Rusyns. New York: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. 2018. The heritage of autonomy in Carpathian Rus’ and Ukraine’s Transcarpathian region. Nationalities Papers 43: 577–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magocsi, Paul Robert, and Ivan Ivanovich Pop. 2005. Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michna, E. 2010. The Rusyn History Is More Beautiful Than the Ukraianians’:Using History in the Process of Legitimization of National Aspiration by Carpatho-Rusyn Ethnic Leaders in Transcarpathian Ukraine. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/the-rusyns-history-is-more-beautiful-than-the-ukrainians-using-history-in-the-process-of-legitimization-of-national-aspiration-by-carpatho (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Mihalasky, Susyn Y. n.d. The “Second Boat” Docks in Greensburg: Carpatho-Rusyn Conference a Hit. Available online: http://www.carpatho-rusyn.org/crs/gburg.htm (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Morrone, Adolfo. 2006. Guidelines for Measuring Cultural Participation. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/guidelines-for-measuring-cultural-participation-2006-en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Murray, Catherine. 2005. Cultural participation: A fuzzy cultural policy paradigm. In Accounting for Culture: Thinking through Cultural Citizenship. Edited by Caroline Andrew, Monica Gattinger, M. Sharon Jeannotte and Will Straw. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, pp. 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pasieka, Agnieszka. 2021. Making an Ethnic Group: Lemko-Rusyns and the Minority Question in the Second Polish republic. European History Quarterly 51: 386–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, Jean S. 1989. Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence 9: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, Jean S., and Anthony D. Ong. 2007. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54: 271–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, Stefan M. 2009. The Rusyn Language: A Grammar of the Literacy Standard of Slovakia with Reference to Lemko and Subcarpathian Rusyn. Port Moresby: Lincom. [Google Scholar]

- Rosko, Daniel. 2017. The impact of Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants and their descendants on the United States. The Saber and Scroll Journal 6: 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rusinko, Elaine. 2010. Committing Community: Carpatho-Rusyn Studies as an Emerging Scholarly Discipline. Boulder: East European Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Rusinko, Elaine, and Bogdan Horbal. 2019. Carpatho-Rusyn scholarship in America, 1988–2019. Річник Рускoй Бурсы 15: 205–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Seth J., Byron L. Zamboanga, and Rob Weisskirch. 2008. Broadening the study of the self:integrating the study of personal identity and cultural identity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2: 635–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, Marshall H. 1986. Culture and behavior: Psychology in global perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 37: 523–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Raymond A. 1997. Indigenous and diaspora elites and the return of Carpatho-Rusyn nationalism, 1989–1992. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute 21: 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, Dick. 2006. The social effects of culture. Canadian Journal of Communication 31: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2012. Measuring Cultural Participation: 2009 Framework for Cultural Statistics Handbook No. 2. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/measuring-cultural-participation-2009-unesco-framework-for-cultural-statistics-handbook-2-2012-en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).