1. Introduction

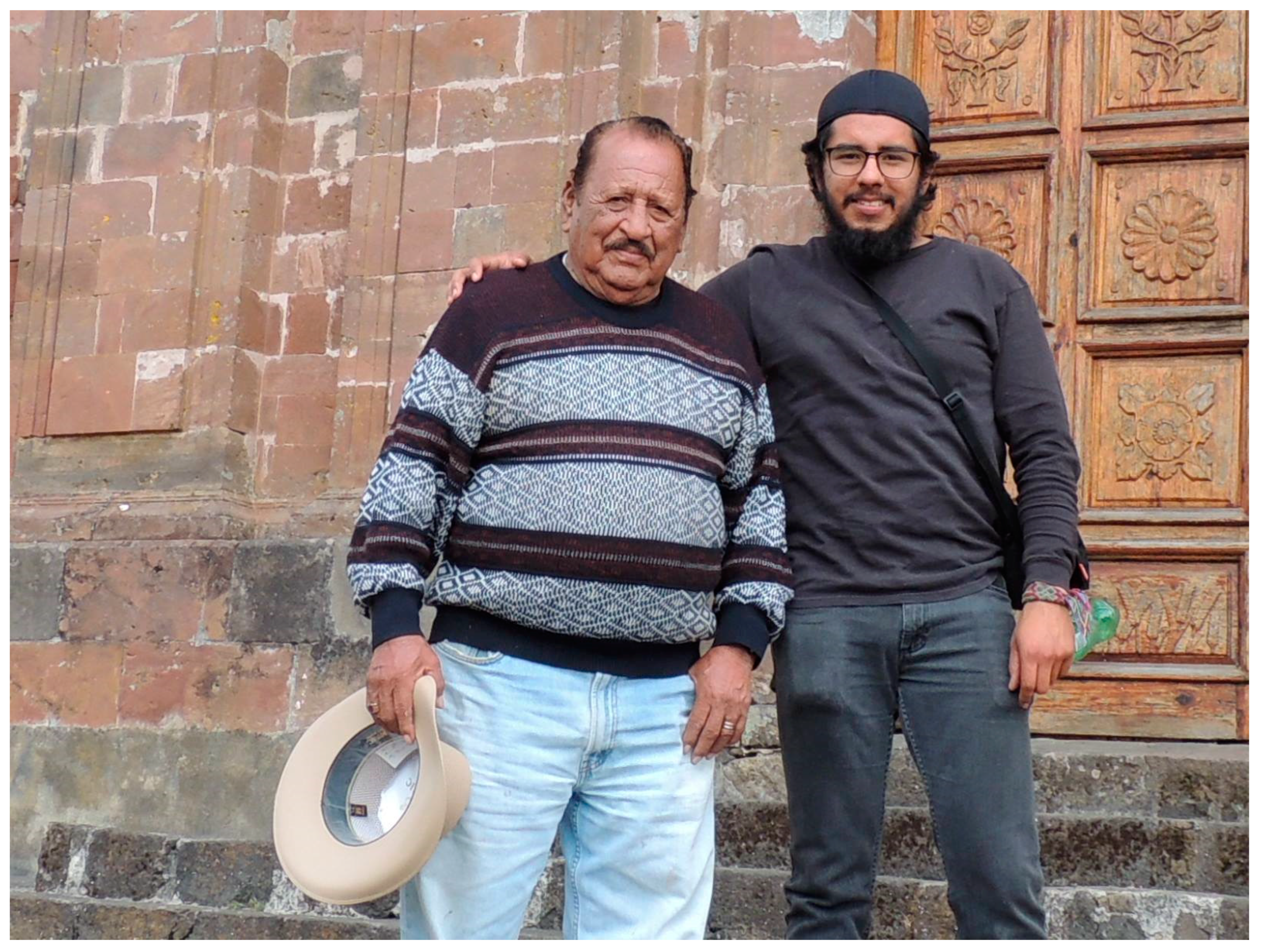

I grew up in an Indigenous P’urhépecha and mestiza family in Tangancícuaro (the son of a mestiza mother and a P’urhépecha father), a town in the northwest region of the state of Michoacán, México (see

Figure 1). Because I grew up with my grandparents, I listened to elders’ stories since I was a child. This experience not only influenced my interest in histories about the past of my family and

pueblo (town), but also, years later, determined my approach to researching queer Indigenous histories. Among the histories I listed as a child, I do not remember learning even one history about a queer person who was recalled with dignity and love. In my social context, queer people were named with derogatory terms, and the local memories about them were tied to violence, homophobia, and suicide, which affected the way I grew up as a queer child who tried to fit into the normative structures of my family and community. For my P’urhépecha

abuelo (grandfather) Enrique Gómez Montelongo, or

Papá Quique, as I called him, the ways of living in the past seemed to be better than the ways we live in the present. In the past, my abuelo recalled, queer P’urhépechas either did not exist or were portrayed as a speculation of the “chaos” that modernization would one day “cure”. The local fear of queerness made me feel contradicted about my P’urhépecha identity since, as a queer person, I might not be able to honor all the histories and traditions that my Papá Quique passed to me.

In this essay, I rely on Indigenous methodologies of storytelling (

Miranda 2013;

Kovach 2021;

Smith 2012;

Simpson 2017) and the ways that my Papá Quique taught me to connect with the histories of our ancestors, including the Mountains. He always advised me to walk this life with a purpose and humbleness. Like other local Indigenous elders, he would rely on the landscape to pass to me our histories and Indigenous cosmogonies.

1 I remember some days, we stood outside of the house to talk and appreciate a big field that separated our house from the town; this was a land where locals used to plant corn or sorghum before international agricultural companies invaded our community in the early 2000s. With his right hand, he would point in the direction of that field, a field that was just in front of the Mountain we call

La Beata. He would tell me that, in life, it is important to follow a

surco (a furrow) like the ones in the big field; those surcos had a start and an end, and their

tierra (soil) provided food to our town. According to Papá Quique, following my surco would allow me to walk

una vida derecha (a straight life). He also believed that the seeds we plant in these surcos are the human relations we develop in life, and that the memories we build with others are the only things that last after we pass. Although all the histories and analogies he passed to me have illuminated my path, I knew I would not be able to walk that straight surco. As I started to embrace my queerness, my surco went in all directions but never straight. I got lost multiple times, trying to find my path, until I realized that it was okay not to follow a straight surco and that I would still honor my ancestors as long as I walked with a purpose in life, and I served my family and community.

The lack of queer histories in my family and pueblo mobilized my spirit and body to seek those histories and bring them to the surco of my life to illuminate not only my

camino (path), but also the surcos of other queer Indigenous people who want to learn about queer histories from Indigenous perspectives. Like my queer spirit, my research has been in movement, in connection with people and more-than-humans. Because there is not a research method in my community or in Western academia that encapsulates the spirit of my research approach, I resolved to coin my own term, talking-while-walking, which reminds me of the long conversations I had with my Papá Quique in the house or while moving through the caminos in the P’urhépecha Mountains we walked together. To support my methodological analysis, I borrow Indigenous Mississauga Nishnaabeg artist and scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s approach to Indigenous methods, alluding to her experience as

kwe2 and within her people who “always generated knowledge within kinetics of our placed-based practices, as mitigated through our bodies, minds, and spirits” (

Simpson 2017, pp. 29–30). Talking-while-walking also refers to those critical moments in which queer Indigenous individuals use any resource available to survive and make sense of their lives in a socio-cultural environment infested by gender binary traditions and heteronormativity.

Through my academic and community work, I honor my abuelo’s traditions and his knowledge while I bring to life the histories of queer P’urhépechas. This essay is about queer histories, the histories I did not get to learn from the voice of my ancestors. The histories they hid from me and others like me. To claim these histories, I used any available resources, including oral histories, archival records, information in the media, and interviews. The settler colonial system played a critical role in burying queerness from archival records and collective memory, which guaranteed the Spanish colonizers the control of Indigenous lands and the cultural assimilation of Indigenous people in different parts of the hemisphere (

Wolfe 2006;

Tortorici 2007;

Miranda 2010;

Zaragocin 2020). I argue that queer histories are unstable; they arise from death and the hope of a queer future, a future stolen by the colonizers more than five hundred years ago. As the reader will notice, I relied on any historical source available to fit the surco my abuelo asked me to honor. I did this because this is my service to my community and because queer histories also deserve to live with dignity and love, like any other living being.

2. An Entry to Queer P’urhépecha Studies

In the growing field of P’urhépecha studies, most of the scholarship has overlooked the histories of queer P’urhépechas and how the gender spectrum displaces queer P’urhépechas from Indigenous traditions (

Jacinto Zavala 1988,

1995;

Franco Mendoza 1994;

Cortés Máximo 2019;

Lucas Hernández 2019;

Márquez Joaquín 2023). There are few academic accounts preoccupied with issues related to queer P’urhépechas and gender binary issues conducted by queer P’urhépecha scholars. Examples include the work of poet–scholar

Fabian Romero (

Forthcoming), who examines P’urhépecha migration, diaspora, kinship, and queerness’ embodiment, and the poet–scholar Gabriela Spears-Rico, who explores issues related to Indigenous P’urhépecha/Pirinda and Chicana motherhood, and systemic violence against Indigenous women (

Spears-Rico 2019,

2021). Nevertheless, the path to decentralizing colonial narratives of queer Indigenous people is still

aspero/rough, in particular because of the lack of records about queer histories and the fact that P’urhépecha and non-P’urhépecha scholars center their investigations on historical records that highlight P’urhépecha patriarchy and the gender binary, paying less attention to the complexities of these practices.

I drew this essay from previous historical accounts of the early colonial history of the P’urhépecha people and the colonization of Indigenous gender and sexualities, such as the works of North American historian

Zeb Tortorici (

2007,

2018) and Mexican American historian

Daniel Santana (

2019). Santana’s contributions to the study of the “androcentric narratives” of P’urhépecha people in the 16th century via historical texts like the

Relación de Michoacán (1539–1541) and the

Relaciones Geográficas (1575–1585) is essential for my analyses on the early colonial construction of the gender binary. As best described by Santana, hypermasculinity performed in colonial records helped Spanish and P’urhépecha men in positions of authority to define the limits of the Purhépecha territory and the “borderlands of gender” (p. 4). I also rely on the paleographic work of Nicolaíta

Armando Mauricio Escobar Olmedo (

1997) on the text “Proceso contra Tzintzincha Tanganxoan, el Caltzontzin, formado por Nuño de Guzman. Año de 1530”. This document describes a trial started by the Spanish conquistador Nuño de Guzman in January of 1530 against the last P’urhépecha Cazonzi (

Irecha/Governor) Tzintzincha Tanganxoan (Don Francisco is his Christian name). The main accusations against the Cazonzi were “holding the payment of tribute of P’urhépecha communities to the Spanish people; the robbery of tribute from P’urhépecha towns; of hiding the gold and silver; of killing many Spanish people, of being a sodomite and suborn the justice” (p. 26). In this case, I focus on the accusation of sodomy against the Cazonzi and his romantic relationship with two P’urhépecha men called Juanico (pp. 31, 90) and Guysacaro (pp. 90, 159).

3 Although the charge for sodomy could have been a lie made up by Guzmán to execute Tzintzincha Tanganxoan and take control of the P’urhépecha territories, the historical records still suggest homoerotic practices and public romances between P’urhépecha men before and during the first years of the Spanish invasion in Michoacán. Tzintzincha Tanganxoan was tortured and sentenced to death in Conguripo, Michoacán, on 14 February 1530: “he was covered with a

petate and tied from his feet to a horse and dragged across the camp, after, when he was moribund, he was tied to a tree surrounded by undergrowth and burned alive” (p. 31).

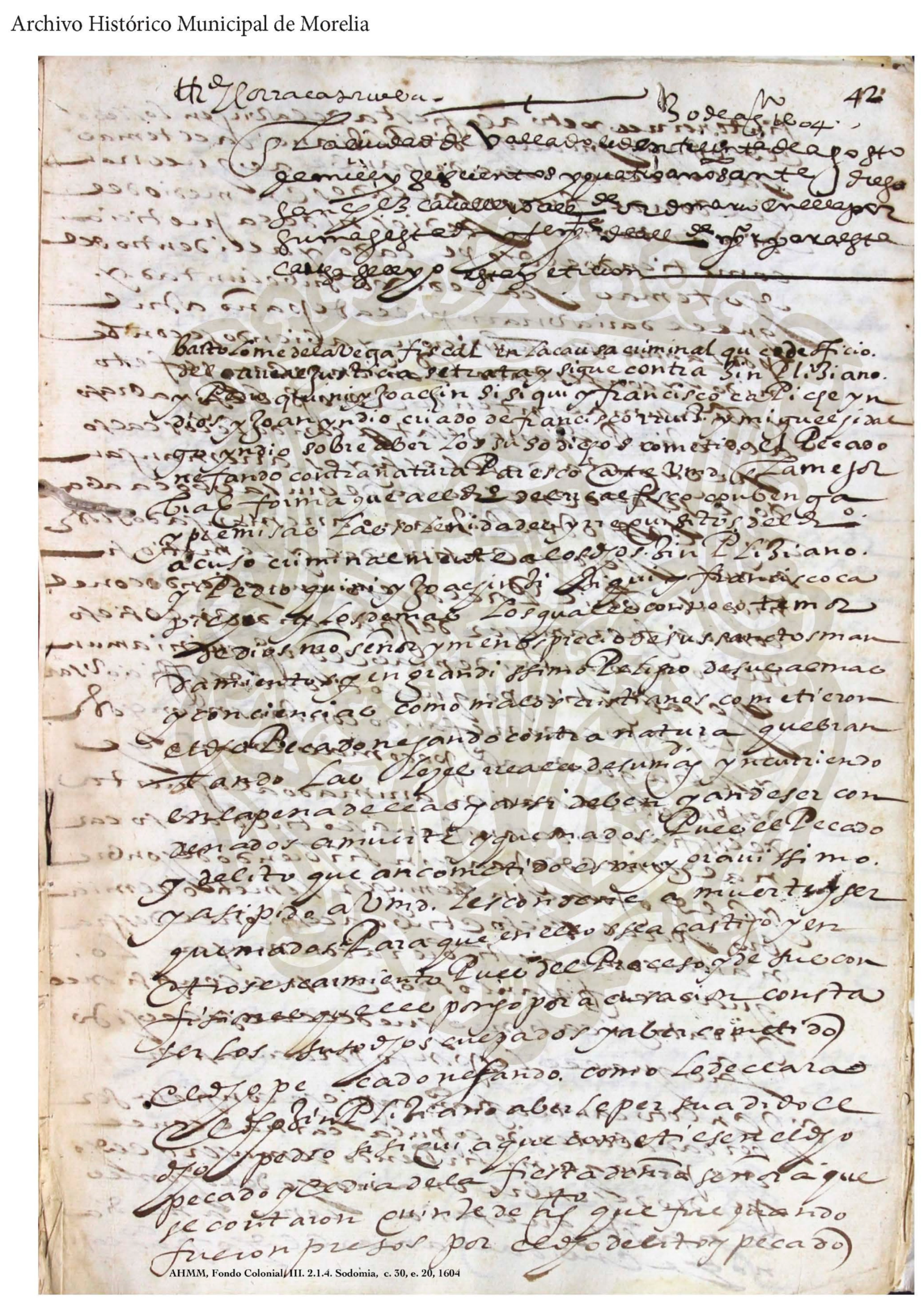

Like a fractal system of images of genocide, the violence from the past travels across time, manifested in different moments in the history of P’urhépecha communities, like Tortorici demonstrates in the cases he analyzed about queer P’urhépechas in the Michoacán of 1604 (

Tortorici 2007,

2018). In the spring of 2020, in my search for historical accounts about queer P’urhépecha histories, I first found the work of Tortorici, who became a critical interlocutor for my examination of criminal trials related to sodomy committed by queer P’urhépechas in the early colonial Michoacán. Tortorici’s archival references guided my path when I arrived at the Archivo Histórico Municipal de Morelia (AHMM) in Michoacán in the fall of 2022, where Tortorici encountered the file that preserves the history

4 of Simpliciano Cuyne, Pedro Quini, and other queer P’urhépechas accused of sodomy in Valladolid (Morelia), Michoacán, in 1604. Contrary to Tortorici, my intention in accessing the archives was not to produce a historiographic account of queerness, voyeurism, or sexual desires. I recollect their histories and compare them with the violence queer P’urhépechas experience in the present and the lack of records related to this violence, like the case of a queer P’urhépecha man who was killed by community members in Santa Fe de la Laguna (a town in the Lake region) in the fall of 2021, and whose body was found in the community by street dogs who pulled out corpses from the ground. This history was preserved only among the community and was not documented by the government or the media.

Notably, I do not attempt to map historical trials, nor the different mechanisms that colonial institutions used to torture queer Indigenous people in Michoacán. First, because these mechanisms fluctuated across time, the death penalty was a common punishment for those committing sodomy “between the early sixteen century and late seventeenth” (

Tortorici 2018, p. 70). Colonizers used the “medieval law on sodomy”, the “

Siete Partidas” (p. 72), which decreed the death penalty for those committing it. The second reason is because of the lack of written records about queer P’urhépechas not only in the colonial Michoacán but also during the independent period. In this case, I rely on the trials against the last P’urhépecha Cazonzi, Simpliciano, and Pedro as my only written historical references about P’urhépecha queerness to shed light on how violence against queer individuals was used as a mechanism to create a homogenous P’urhépecha identity based on the colonial gender binary and “hypermasculinity” narratives (

Santana 2019, p. 14). This violence not only promoted heterosexuality but also limited the possibility of love and homoerotic relations beyond the norms. A scholar on queer Indigenous gender and sexuality, Mark Rifkin, suggests that “queerness necessarily exists outside of dynamics that could be understood as kinship” (

Rifkin 2011, p. 28). Since queerness did not favor the colonial project of settler gender, it was (and is still) constantly persecuted. I do not assume that other cases of persecution against queer P’urhépechas did not happen in the early colonial Michoacán. As I signaled in the introduction, most of the P’urhépecha history and traditions have been passed via orality through the voices of elders (

Franco Mendoza 1994, p. 212), which makes it difficult to find written records about queerness. By considering these limitations, I seek queer histories and the enforcement of the gender binary through other archives, such as the voice of my abuelo and the histories I have learned about the P’urhépecha landscape while have I talked and walked with the people.

2.1. Theoretical Conceptualizations and Family Research Methodologies

In my intent to recover queer histories, I seek clues about the current persecution and murders against queer P’urhépechas in Michoacán because death is always present in the few narratives about queer people in Michoacán. While I recognize the relevance of institutional archives as repositories for the preservation of the past, I also explore alternative historical accounts beyond the institutions. This includes my abuelo’s oral traditions and more-than-humans such as the P’urhépecha Mountains, who are also part of my family lineage and with whom I interacted while growing up. As a teenager, I always ran to the Mountains and the Lake in my community when I needed to escape from the social constraints and wanted to talk to someone who would not judge my queer spirit—in those moments when I just wanted to be. Indigenous Ho-Chunk feminist anthropologist Renya Ramirez, in the context of Indigenous intersectionalities, considers more-than-humans those living beings interrelated to “other than humans–animals, fish, bees, water, plants, and land–without creating a hierarchy, but rather points to how humans and more-than-humans are intertwined and connected” (

Ramirez 2023, p. 186). For Papá Quique, the landscape, particularly the Mountains, had a voice, a history that my abuelo knew and honored as much as he honored the voices of his human ancestors. The way he talked made me believe that he was a messenger of the history of the Mountains, those who are also family to us.

Among the histories Papá Quique shared with me, there is one that was particularly difficult to listen to, or at least it was for me. However, this history was crucial for the foundation of this paper since it relates to queer silences and local speculations about queerness as a reference to social chaos that will arrive in the future, challenging the gender spectrum and even the traditional family organization. This history also reflects the intergenerational Indigenous methodology passed among my family talking-while-walking. The first time he shared the history with me, I remember being a teenager, the time I faced the guilt of my secret queerness. The second time, I was already an adult, and I was open about my queerness with most of my close friends and some family members, but not with my abuelo.

Papá Quique recalled that in the early 1940s, when he was a chamaco (teenager), one of those days while walking through the P’urhépecha Mountains in Michoacán carrying artisanal products for his mother from Patamban to his hometown Paracho, he stopped to rest in Santa Cruz Tanaco, one of the localities in the heart of the P’urhépecha Mountains. While sitting outside a small grocery store and providing water to his horse, he spoke to an elder in the town. The elder shared with my abuelo that “one day, planes, like those big things flying in the sky, would destroy towns, and that men would try to be women, and women would try to be men”. The elder’s premonition coming from the voice of my abuelo sounded like an apocalyptic end for the world. The most interesting part was when my abuelo said, “Look mijito (my kid), those things are already happening, look how the raza (people) act; we don’t even know what is going on and who is who”. Papá Quique referred to queer people in our community who challenged the gender binary by wearing clothes that, in the eyes of my abuelo, did not correspond to the social expectation for “biological” women and men and who were contesting the traditional order.

Both times Papá Quique shared the history with me, it made me feel ashamed and anxious. My body experienced a heat that ran from my head to my hands uncountable times while he was talking. I felt head pressure and my heartbeat. Although I was close to having a panic attack, I saw and listened to him with attention, trying to make sure he did not realize my body was sweating and shaking. Not breaking my silence and contradicting his history was difficult since I wanted to tell him that this premonition was not true, that his mijito was queer, and that I was not a representation of the chaos he illustrated. But it was even more difficult to understand myself in the complexity of the P’urhépecha identity as a queer person who navigates a tradition that rejects queerness.

2.2. Knitting Research Methodologies from Indigenous Perspectives

Moving through the P’urhépecha landscape with my abuelo was an epiphany; I learned about his Indigenous roots, the ways in which he learned to cultivate the land without machinery, and the transformation of the landscape “from rural into modern” due to the construction of highways and the introduction of other modern devices. While we walked or drove through the P’urhépecha landscape, my abuelo shared with me the names of the P’urhépechas

Cerros (Mountains) and the hidden routes to access to P’urhépecha pueblos through the Mountains’

senderos (paths) he transited as a child (see

Figure 2). Exhausted with having to prove my queer Indigenous research methodologies to colonial and Western research approaches, I introduce my queer research methodology, talking-while-walking, bringing the P’urhépecha approaches of building collective knowledge and cracking the archives from my queer experience.

In the case of the P’urhépecha landscape, I recognize that most of the Mountains have gender binary names, many of which have been adapted into the Spanish language and allude to a Catholic saint, a P’urhépecha animal, or the name of one of the closest towns. In my hometown in Michoacán, I interact daily with the magnificent landscape of El Cerro de Patamban, Las Tres Marías, La Beata, El Cerro de San Ignacio, and El Cerro del Tecolote. The names of these Mountains are preceded by the article la/las (she/they) for “female” Mountains and el (he) for “male” Mountains. Considering that the P’urhépecha language does not have a gender binary as Spanish does, it is significant to question the necessity of P’urhépechas for gender binary terms and how colonization influenced the transition into the gender binary. Some of the Mountains maintain a symbiotic relationship with the local towns, in which the male Mountain is often understood as a provider of water or other natural resources for the town surrounded by a female Mountain. For the locals, the gender binary organization of the landscape explains why some P’urhépecha towns have more economic prosperity than others. While I recognize that academic spaces have influenced my critical analysis of the gender binary and colonization, and have given me access to academic resources, I also preserve the foundation of my ways to conduct oral histories based on my abuelo’s ways of engaging with the landscape and my queer awareness of the relation between humans and more-than-humans. Thus, I bring to life my abuelo’s capacity to compare the past and present, as well as his preoccupation with the social and cultural transformations that affect the collective. In contrast to my abuelo, I claim the queer P’urhépecha histories that can help others to inspire their own caminos, since many of us do not have others to follow.

Moreover, the inspiration for my work comes from my close connection with queer P’urhépecha histories and the preservation of oral histories (and my commitment to collect them not only with a critical eye but also with caring and love, as Esselen and Chumash Indigenous scholar

Deborah Miranda (

2010,

2013) and P’urhépecha scholar Luis Urrieta (

Urrieta 2019) do in their work. Writing this essay involved multiple emotions, since I relate to the histories I collected with my interlocutors and, with some of them, became friends. Also, as a scholar of color who researches my communities, I feel the obligation to acknowledge how community support is influential in my research approaches; this is not only because my family and community connect me with potential interlocutors, but also because my research agendas reflect the insights of the communities I work with. North American historian Jeffrey Erbig uses a mapmaking approach and geographic information systems (GIS) to trace colonial borders in Río de la Plata via archival records (

Erbig 2020). My work takes inspiration from Erbig’s border-marking project to track queer histories through the colonial archive. But I instead engage with speculative histories and orality to build a queer P’urhépecha archive. Now that my abuelo is on a different plane, my mother, father, aunts, and uncles have become my storytellers and cartographers.

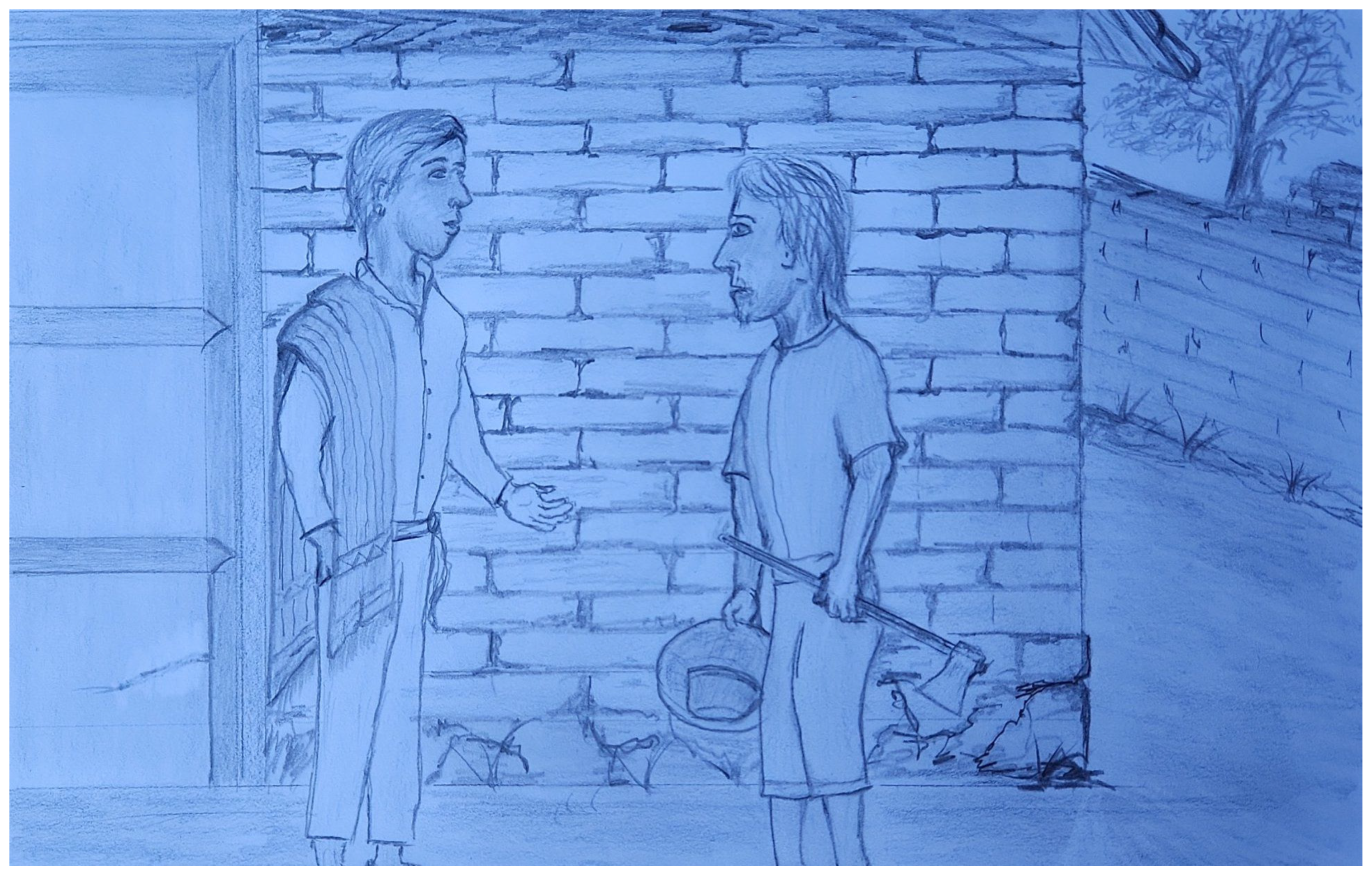

I have included my father’s art to perpetuate his knowledge in a creative and accessible way for future P’urhépecha generations. He was excited to collaborate with my work with his knowledge about the P’urhépecha landscape via the creation of a map of the P’urhépecha regions in Michoacán, a landscape he transited for over three decades when he worked painting small grocery stores in the region. Also, via a drawing, he helped to illustrate the two queer P’urhépecha characters persecuted in 1604. My father’s creation of the drawings is crucial in my work for two reasons. First, he provided his Indigenous knowledge and art to my work to re/create queer histories. Second, I was able to talk to him about the histories of other queer P’urhépechas and explain to him why their histories are important to me; I told him why it was crucial for me and probably for others to know that we have queer P’urhépecha ancestors and queer histories. By talking to my father, I experienced queer joy because he responded positively to my drawing request, unlike when I was a child and I was scared to tell him I am queer. So much has happened in my surco since then.

3. My Journey Back to Michoacán and My Ethnography in the AHMM

I traveled from California to Michoacán in early September of 2022 to conduct archival research in the AHMM and collect testimonies and oral histories about queer P’urhépechas in the P’urhépecha region. This time, my abuelo was not there to guide my journey collecting histories, but his voice echoed in the back of my head whenever I hesitated about my research and the reasons that took me back to Michoacán, a place that brings me sweet and bitter memories. I remembered my abuelo saying, “just look ahead mijito, don’t look back, not even to take an impulse, put a clear line on the tierra, very clear, like a surco, and follow that line, you will see how you get very far, but please never forget your people, and who you are”. Paradoxically, my abuelo’s memory has been crucial for my queer and academic journey. Every step I have moved forward has taken me closer to what he asked me to do, and it has helped me to find myself in the process. Visiting the archive was a challenge since, this time, I directly read the history of Simpliciano and Pedro. Returning to Michoacán and finally touching with my own hands the documents that preserve the history of Simpliciano and Pedro was a big responsibility as a queer P’urhépecha and scholar.

As I prepared for my research in the AHMM, I talked to two P’urhépecha historians, Amaruc Lucas Hernández and Juan Carlos Cortés Máximo from the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, located in Morelia, Michoacán, where I completed my master’s in teaching history. I asked them if they knew other historical documents I must consider for my work about queer P’urhépechas. When I asked historians at the Universidad Michoacana about queer P’urhépecha records, I felt that I violated a tabu and that I may be exiled from the P’urhépecha academy. The historians did not know about the history of Simpliciano and Pedro, which did not surprise me; queer histories often live as ghosts in the memories of communities, and due to the stigma that precedes queerness, P’urhépechas do not preserve them as they do with other oral histories that reinforce gender binary identities. Invoking the work of Avery Gordon on haunting and ghosts, Canadian scholar Ann Cvetkovich reflects, “Representing ghost requires a language of graphic and affective specificity, yet because ghosts are both visible and invisible, the local evidence they produce is not just empirical” (

Cvetkovich 2003, p. 44). Although queer P’urhépechas exist in the life of contemporary P’urhépecha communities, our existence seems remote, too far away in the past or too far away in the future.

5 We, queer people, often do not have a recognized and dignified identity, making us “the ghosts” of the towns. The P’urhépecha communities include queer P’urhépechas in the collective when they need their bodies for certain labors or performances in festivals. However, they are not always part of the socio-cultural and historical landscape because of the social normativity and the traditions of the communities that favor rituals led by cisgender–heterosexual couples.

When I think about the memory my abuelo collected with the elder in Tanaco, I find that queer bodies have been the ones suffering the “destruction” my abuelo worried would make the communities disappear. My return to Michoacán in 2022 was definitely emotional since, as a queer P’urhépecha, I embodied the fear of experiencing homophobia and physical violence. I questioned whether something tragic would happen to me, whether my history would make it into the archival records, or whether I would be just another body whose history would be erased from the memories of the communities in Michoacán, just for being queer.

Visiting the Institutional Archives

As an ethnographer and oral historian, visiting an institutional archive made me feel uncomfortable because my research tends to happen in the streets while I talk and walk with people, and in their houses while we share a meal, a drink, or a dance. Also, I am a person who is usually loud and who needs to move my body even if I am sitting. For example, right now, while I write this essay from a coffee shop in Santa Cruz, California, I am dancing in my seat to some 1990s pop music the barista is playing in the speaker. Accessing a governmental space that requires silence as a norm triggered my body’s capacity to “act” quietly. I did not know how I would manage reading about the torture and murder of my queer P’urhépecha ancestors without interrupting the normativity of the archival reading room with my body expressions. In this section, I dive into the relation of my body to the archives, and I trace the colonial discourses to justify the violence against queer P’urhépecha bodies in 1604. Moreover, I trace the relationship of these events with the ongoing violence against queer P’urhépechas and the institutionalization of heterosexuality, or “hegemonic straightness” in the words of

Rifkin (

2011, p. 10).

In the trial against Tzintzincha Tanganxoan, sodomy was raised as one of the causes of his persecution. However, there is no clear sign of relating this practice to occupying women’s roles or challenging the gender spectrum in the Michoacán of 1530, unlike the case of Simpliciano and Pedro, which clearly describes gender roles during the sexual encounter. The violent control of Indigenous sexuality and the imposition of the gender binary seem to have been more dramatic in the early 17th century. I demonstrate that the erasure of queerness in the history of Indigenous communities in México has functioned as a weapon in the creation of a homogenous nation, in which often humans and more-than-human entities, socially identified as “female” or “male”, are assigned to specific gender roles in the Indigenous family and community. These phenomena increase the lack of recovery projects on queer histories since queer individuals are preconceived as a disruption to the hegemonic normativity and are often socially dehumanized. This might not be the case for every Indigenous community in the Américas, but in the case of P’urhépechas, the gender binary roles are crucial to keeping the Indigenous traditions alive.

One of the methods I have found to explain the erasure of queer histories and the stigmatization of queer people among P’urhépechas is analyzing the violence applied to control and eradicate queerness during the early colonial Michoacán. While Papá Quique connected queerness with a chaotic social transformation, I argue that queerness opens the possibility for social heterogeneity, and it has the potential to challenge the ongoing colonization of gender (

Rifkin 2011). Nevertheless, the violent extermination of queer Indigenous people in the early years of the colonization contributed to the oppression of gender and sexual heterogeneity, or at least this is what the ecclesiastical and secular colonial institutions tried to achieve in Michoacán and other regions in the Américas (

Garza 2003;

Horswell 2005;

Miranda 2010;

Driskill et al. 2011;

Sigal 2011).

The scholar of American Literature Rodrigo Lazo reflects on the history of the “national archive” as a space that helps the state to build legitimization. “Archive and nation came together to grant each other authority and credibility: the archive contained documents and records that supposedly spoke to and about the state, while the nation granted a certain cachet to an archive, elevating it above its local and regional counterparts” (

Lazo 2009, p. 36). In my scholarship, I rely on the records found in the institutional archive as a source to learn about the violence committed against queer P’urhépechas in the early colonial Michoacán, but I also recognize that, most of the time, queer histories do not make their way to the local or national archives, like the case I mentioned earlier that occurred in the Lake region. The contemporary cases of homophobia and murders against queer P’urhépechas that I have collected I learned via orality from my P’urhépecha informants in Michoacán, with whom I share similar stories and struggles, and many of whom I consider my queer family. Being vulnerable was crucial to develop a rapport with them as a local researcher. Mexican–Filipino American anthropologist

Jason De León (

2024) talks about the significance of trust in conducting ethnography, in which the process of claiming human voices requires the researcher to be vulnerable to understand the complexities of the humanity of their interlocutors. Because I echo with most of the histories I collected, my heart and empathy were in the field, even if I did not want it.

In the Justice Records of the AHMM, the file “Contra Simpliciano, y Pedro Indio por el pecado Nefando” is stored in box 30, file 20. I memorized the file’s location the first time I read Tortorici’s work in 2020. I feel like something that is part of my memory is stored beyond my body in a place encrypted under several passwords and protected by a guardian who doubts my purpose in the archives. Previous to starting my visits to the institutional archive, I had to prove to the director of the AHMM why I was there and how I would use the documents I wanted to revise. When I navigate bureaucratic protocols, I experience emotional discomfort since what are apparently “public sources” do not seem that way when there are steps that require some level of literacy. These formalities limit the public’s access to these spaces. I thought about my abuelo and the rest of my P’urhépecha interlocutors, who most likely would not have been able to access the “archives” because they did not have the level of “knowledge” required to navigate these institutional protocols. After Diana Huerta Piña, responsible for the consultation room in the AHMM, handled the file, and before I opened it, desde mi corazón, I asked Simpliciano and Pedro for permission to read their history, and Papá Quique for the wisdom and strength to process the document.

4. Knitting a History of P’urhépecha Queerness

Simpliciano and Pedro met in Valladolid, now Morelia, Michoacán’s capital. Apparently, they met for the first time on 15 August 1604, the day of the celebration of the Virgen in Valladolid. Their history intersects with another eleven queer P’urhépecha men who were implicated in a trial conducted by the Catholic Church and the Spanish government. Simpliciano and Pedro’s history arrived at the archives because they were caught having sex in a temazcal (a steam bath that people of several Indigenous Mesoamerican communities used for religious rituals and spiritual and healing purposes) located on the property of the priest Juan Velázquez Rangel. As a queer P’urhépecha, I felt conflicted about the many details that the archive contains about the sexual intimacy of the queer P’urhépechas implicated in the 17th-century trial. Because of this discomfort, I decided only to mention what I considered necessary to dive into the enforcement of the gender binary and the eradication of queerness, especially because, in the decade of 2020, queer P’urhépechas are still being morally judged by the Catholic Church, and society persecutes and kills queer individuals within and outside P’urhépecha communities. Moreover, my queer P’urhépecha interlocutors expressed feeling discomfort when locals, out of curiosity, asked them about their sexual roles during sexual encounters, so this made me ask myself how much I would like others to say about my sexual intimacy if I was the one everyone observed wearing only the vulnerability of my already-sensitive skin. I will engage with these issues in the following paragraphs.

As I read the history of Pedro and Simpliciano, I imagined they were talking directly to me; their history took the shape of an oral history in my mind and heart. I probably did this exercise “of imagining their bodies and the tone of their voices” because it made the information more human and digestible. They were always present in my mind as narrators, guides, and family. It was like we talked and walked together. Ultimately, this was how Papá Quique taught me to engage with histories. On the day of the celebration of the Virgen in Valladolid, while Simpliciano Cuyne was drinking some pulque near the Valladolid Plaza, Pedro Quini approached him to sell a piece of cloth (see

Figure 3). After they met, they went to the mentioned temazcal because, apparently, Pedro insisted on going there to continue drinking and to sell Simpliciano the piece of cloth. Inside the temazcal, Pedro expressed his sexual desire for Simpliciano. The two P’urhépecha men had sex in the temazcal. However, the fourteen-year-old nephew of Velázquez Rangel heard some sounds coming from the temazcal, which raised his curiosity to verify what was happening. He discovered that Simpliciano and Pedro were having sex, and that one man was on top of the other,

like woman and man. Because he assumed he was the witness of a crime, he called other people to verify whether Simpliciano and Pedro were committing the

nefarious sin against nature. At the temazcal, the young Nahuatl-speaking Gaspar arrived, a servant of Velázquez Rangel, and two Spaniards, García Maldonado and Juan Hernández. When Simpliciano realized they were caught, he ran in the direction of the San Agustín Church, where he worked as a sacristan. However, Pedro was not fast enough to escape, and he was captured and taken to the careo to provide his testimony. The capture of Pedro and Simpliciano opened a criminal trial that lasted from mid-August until mid-October of 1604, when the sentence was finally declared.

Nevertheless, what at first started with “two men in a temascal”, as Tortorici notes, became a “web of sodomy accusations began with Pedro’s second confession” (

Tortorici 2018, p. 58). In this queer web, there were thirteen queer P’urhépecha men involved, and some of them were originally from other P’urhépecha communities, like Tzintzuntzan and Uruapan. Pedro provided the names and locations of the other men with whom he had sex, and he also mentioned the sexual roles he occupied with them. The reference to

serving like a woman appears fairly frequently in the archive of about eighty folios, and it was used by the witnesses and those who committed the “crime” of sodomy. As noticed by Tortorici, “Colonial criminal courts, as we will see almost always understood and (linguistically) represented the act of sodomy in highly gendered terms” (

Tortorici 2018, p. 63). These details are important for my analysis of gender since queer P’urhépechas in the 21st century continue to face uncomfortable questions about who occupies the woman and man roles during sex. Apparently, this information is essential for P’urhépecha communities to categorize a queer couple under the gender spectrum. A queer P’urhépecha man from Santa Fe de la Laguna, a town in the P’urhépecha region of the Lake, expressed that he often deals with this question asked by friends and family members. In July of 2023, when we spoke over the phone, I asked him how he navigates the gender binary and family organization in his community. He shared that one of the challenges he encounters is when locals ask him who occupies the woman role in the festivities or during sexual relations. While he expressed this question, he responded to himself, “we are just a couple of two men, and in the [sexual] intimacy, it is our problem what we do and what roles we occupy. I want to be with a man and not a woman [referring to that he wasn’t interested in dating women]”. He emphasized not feeling the necessity to explain to those who ask how he experiences sexuality.

While in the case of Simpliciano and Pedro, sodomy was related to offenses against Catholic beliefs and was interpreted as a criminal act against the colonial government law, the institutionalization of sodomy via violence deployed hegemonic narratives of normativity. I venture to say that this limited the possibilities of queer love and/or queer romantic relations since the gender binary and heterosexuality were enforced as the only path (surco). In the 1604 queer P’urhépecha trial, six of the thirteen men were captured and treated for sodomy by the criminal court (see

Figure 4). Five of them were publicly tortured, and four were sentenced to death, including Pedro Quini, Joaquín Ziziqui, Francisco Capiche, and Juan Indio. I do not intend to provide an extensive history of the criminal case, since Tortorici has accomplished this task (

Tortorici 2007,

2018). My objective is to analyze the terms used by colonial institutions to name those P’urhépechas who challenged normativity because similar terms are used in the 21st century to categorize and persecute queerness, as I explain in the section that follows.

Reproduction of Colonial Violence in the 21st Century against Queerness

The accusations made against Simpliciano and Pedro, such as being found in flagrante infernal event, committing sins against nature, or serving like a woman, are crucial to understand what queerness means for P’urhépecha communities in the present and its relationship with the chaos my abuelo evoked. For example, in various P’urhépecha communities that still speak the native language, there are forms to refer to those people who act beyond heteronormativity and that allude to Catholic beliefs, social morality, and the gender binary. According to the public teacher and native P’urhépecha speaker Edna Tane Álvarez Cristóbal from Santo Tomás, a town in the Cañada region, “No ambákiti kini paati” refers to “the devil will take you”, which is significant in this case for two reasons. First, ideas about the devil are tied to social constraints read under the lens of Catholicism since it is expected that those who act “good” will go to heaven and those who act “bad” will go to the inferno. In this case, the inferno is the expected punishment that queer individuals will receive after this life. Second, it shows the multilayered system behind the social judgment of queerness in which the Catholic Church, the P’urhépecha family, and other social actors persecute non-normative behaviors and often put into evidence the sexual inclinations of queer individuals. The problem behind these gender binary narratives and accusations against queer people is that, many times, queer individuals face homophobia and direct physical aggression toward their personas.

Most of my queer P’urhépecha interlocutors have experienced verbal and physical aggressions more than one time, and they are concerned about the murders of queer P’urhépechas in their native communities, like the cases of Nahuatzen in the early 2000s and Santa Fe de la Laguna in 2021. According to the non-profit organization Letraese, between 2018 and 2022, in México, 453 violent murders occurred against people with diverse sexual orientations (

Letraese 2022, para. 3). However, trans women from the LGBTQ+ population are the most affected by the violence. In 2022, Letraese registered 87 violent murders against the LGBTQ+ community in México. Among these murders, 48 corresponded to trans women, 22 to gay men, and 11 to lesbians (

Letraese 2022, para. 5). Referring to the fractal system of genocide I mentioned earlier, from the 2022 cases, 27 of the victims “were subjected to multiple violences: blows, sexual violence, torture signs (bodies tied from their feet and hands) and other violent attacks to the corps of the victims” (para. 6). In the case of Michoacán, the activist José Daniel Marín Mercado, during a press conference in Morelia, informed the media that the state accumulated 89 crimes of hate from 1995 to 2018 (

Quadratin 2019, para. 2). In an interview I conducted with Marín Mercado in Morelia, Michoacán, in January of 2024, he stated that, via Responde Diversidad (a non-profit organization where he collaborates supporting LGBTQ+ communities), he has learned about the cases of trans P’urhépecha women who lived for some years in the city but when they went back to reside in their

pueblos, their families did not recognize their gender identities and forced them to occupy a gender role within the biological woman and man body norms.

Nevertheless, activist and scholar Itzayana Irán Tarelo Licea from Zamora, Michoacán, affirms that attacks against the LGBTQ+ community might be higher compared to what the authorities say since many crimes are registered under other categories that do not track gender and/or sexual labels. In the first two weeks of January 2024, five trans women were killed in México (

Presentes 2024, para. 1). One of the women was Miriam Nohemi Ríos Ríos, who was shot outside her clothing store in Jacona, Michoacán. Miriam was an activist and coordinator of the LGBTT branch of the political party Movimiento Ciudadano. Before her murder, she had expressed her desire to compete for a councilor position in the next local elections in Jacona.

Miranda follows Maureen S. Heibert to explain the notions of “gendercide”, “an attack on a group of victims based on the victims’s gender/sex” (

Miranda 2010, p. 259). The term gendercide refers to the extermination of Indigenous men called

joyas by Spanish colonizers in the California Missions. According to the Spaniards, these males would not only dress in women’s clothing and perform women’s chores, but they also cohabited or married other men, thereby breaking the gender binary and hegemonic heteronormativity. However, due to the gender spectrum, only men who practiced women’s chores or who were penetrated in a sexual encounter received the name joya. Spanish soldiers found in these practices reasons to justify the execution of joyas, many times feeding their corpses to greyhound dogs. Tortorici affirms that in the 1604 sodomy case, the “punishment had nothing to do with whether these men were top or the bottom, masculine or feminine, ‘active’ or ‘passive,’ married or single, or whether they had committed sodomy once or multiple times” (

Tortorici 2018, p. 69), unlike Miranda, who showed that in the California Missions, the narratives behind the punishment for sodomy were different than those in the case of the colonial Michoacán, which confirms the unpredictability of queer histories across time and geographies. Nevertheless, what is true is that the erasure of queer histories and the violent elimination of queer bodies is an ongoing problem in Michoacán and other regions in México and the rest of the Américas.

Activists and grassroots organizations in Michoacán affirm that, many times, victims decide not to submit a demand to the authorities because of the lack of interest from the governmental institutions to persecute and punish the aggressors (

El Sol de Morelia 2023, para. 3). Marín Mercado states that governmental institutions tend to label crimes against the LGBTQ+ community as “passional crimes”, leaving the victims and their families without justice, as often the aggressors do not receive punishment for their crimes. Many of these institutions reproduce the systemic violence against the LGBTQ+ community, and they enforce androcentric narratives in which minoritized groups do not find an echo to their voices (para. 4). In this sense, I argue that the silence behind queer histories is a common thread in the institutional archives and the oral histories passed by elders to the new generations. Queer histories face a complex socio-cultural system influenced by colonial narratives that dehumanized queer bodies. This has also normalized the elimination of queer people and queer histories, as if our lives have no historical or human value.

5. Final Reflections

In this essay, I demonstrate how, through different narratives and historical accounts, queer histories are erased to enforce straightness and gender binary practices in P’urhépecha communities in Michoacán. Often, queer P’urhépecha histories are tied to social chaos and the violence committed against their bodies. The embracement of queerness by P’urhépecha members is contradictory since the communities tend to silence queer histories, and many times they partner with the state and other local institutions in the extermination of queer people. I also argue that queer histories have been historically unstable in P’urhépecha narratives and in the archival sites. Since national Mexican history centers on androcentric narratives, it is significant to continue exploring how Indigenous queerness disruption can be emancipatory instead of representative of the apocalypse portrayed by my abuelo. Following my ancestors’ ways to preserve knowledge and conduct research was critical for me, since my way of thinking and feeling about life is linked to my connection with my land and the surco of life. The surco I started to walk as a child was guided by the voice of my abuelo, but I recreated it with the force of my queer spirit, where death and hope have become the nutrients of my life (tierra).

Thus, talking-while-walking is not only my research methodology but also a way of living and existing in relation to others, including humans and more-than-humans. I queered my abuelos’ oral history methodologies as I queered my surco, my land. This became my need and is the only way to survive a system that constantly kills and persecutes every living being that challenges the normativity, like the land in my hometown that has been overexploited and converted into a dried landscape by transnational companies. The increment of heat and drastic weather changes in my land is just the response of a queer land that cannot be forced to reproduce only berries and avocados. Queer histories are imperative to weave social transformations for the benefit of everyone and everything. In the summer of 2024, various students of mine in my “Queer Indigenous Histories in the Américas” class at UCSC expressed their discomfort with and pain for not having queer histories in their families and communities; they suffer for always having to start from zero and explain to their families that it is okay to be queer and that they are not committing a “sin”.

I am aware that this paper does not cover every queer experience and that I do not address every temporality and turn in the P’urhépecha history. Like every recollection of history, this is a work in progress, but I want to make sure that the reader remembers that I worked on this paper with slight breaths of histories that my land gave me as gifts. There was not really too much to recollect; the colonial system has done a good job of ensuring the elimination of queer records. I am hopeful that other queer P’urhépecha scholars, activists, and collectors of histories can provide their histories and experiences to the queer P’urhépecha archive so that other queer Indigenous people in the world can find inspiration in our histories to fit the surcos of their lives. To claim the queer P’urhépecha archive, I combined the knowledge of three P’urhépecha generations and put in conversation the ways that Indigenous people connect with collective knowledge, considering a non-linear historical narrative and more-than-human relations as I moved while talking with people and archives. I compared the histories that the archive contains and related them to queer P’urhépechas, and I confirmed what North American oral historian Jamie A. Lee states: “Through archives, the past is controlled. Certain stories are privileged and others marginalized” (Joan M. Schwarts and Terry Cook, 2002, as cited in

Lee 2021, p. 68). My abuelo’s storytelling and his fear about what queerness represented to him showed me that the past, the present, and the future can be controlled by manipulating the content of the archive and by eliminating queer histories from it.

I conclude by reflecting that the lack of queer histories in different cultural groups is not a coincidence. In the case of Michoacán, the fear planted by the colonizers via the persecution and public murder of queer bodies extracted from the land the possibility of homoerotic relations and queer love. Queer P’urhépechas have always existed among P’urhépechas, but they probably do not flourish as shiny flowers in the surco my abuelo referred to. They have been more on the margins of the land, in the shade, like the ghosts of the pueblos. There is a long journey ahead for queer P’urhépecha academics, activists, social organizers, and non-P’urhépecha people compromised with the humanization of LGBTQ2+ P’urhépecha people and their histories. Despite the historical circumstances, some of us are creating/embracing our surcos, and planting seeds in the land, queer seeds, where flowers of many colors can germinate to illuminate the social transformation of P’urhépecha and non-P’urhépecha communities, where everyone can be included, every history can have value, and everyone can be treated with caring and love.