Abstract

The semiosphere reflects universal and culturally determined characteristics. Heraldry is one of the most complex sign systems. Alive and flexible semiotics is urgent for studies. The aim of this paper is to mark the axiological character of Russian and British sovereign state armorials with an accent on animals. Based on both Russian and British research, this paper focuses on syntactics and pragmatics of arms analyzed in a synchronic and diachronic manner. A cross-cultural comparative approach to Russian and British armorial bearings can be viewed as a novel contribution. The paper embraces structural and semantic aspects, the temporal and pragmatics sphere and Jargon du blazon. English heraldry is relevant to the European tradition, and the Russian one has political value. For both countries, it is associated with foreign influence. The system of European coats of arms is coherent with the institution of property and war, and the Russian one with inheritance. For Britain, heraldry was one of the culture-forming components, and for Russia, it was just one of the elements of culture.

Keywords:

coat of arms; heraldry; semiotics; sign; axiology; sovereign state; semantics; syntactics; pragmatics 1. Introduction

Semiotics is a basic cognitive and ontological cultural phenomenon. The semiosphere permeates all spheres of human activity and reflects universal and culturally determined characteristics. Heraldry is one of the most complex and well-developed sign systems or even languages. Many components of the coat of arms can be considered an analog of linguistic elements. It also can be considered an axiological cultural system.

One of the most interesting components of coats of arms is charges, non-heraldic emblems, among which beasts stand out. It is an echo of very ancient beliefs that are universal but still full of cultural characteristics. The image of animals on the coat of arms is rather arbitrary. Besides creatures that do not exist in nature, a lot of hybrid animals appear (e.g., a beaver’s tail is attached to the body of a tiger, and the head is transformed into the head of an otter in the coat of arms of the Irkutsk district) (Figure 1). There are also characters that are difficult to distinguish, for example, a lion and a leopard (which differ mostly by pose) (Slater 2002).

Figure 1.

Coat of arms of Irkutsk.

A comparative analysis of various national heraldic systems gives the opportunity, on the one hand, to distinguish the patterns of functioning of heraldry as a whole and, on the other hand, to fully realize its culturally determined nature. Alive and flexible semiotics is urgent for studies. The aim of this paper is to mark the axiological character of the state emblems of Russia and Great Britain with an accent on animals. This topic is quite extensive, so a small selection of very particular aspects is made here in terms of a comparison of the Russian system with the English one as the most stable. Based on both Russian and British research, the paper focuses on the syntactics and pragmatics of arms described, analyzed, and compared in synchronic and diachronic aspects. The specific topic (Russian and British arms) and cross-cultural axiological approach can be viewed as novel contributions.

Each nation and state has a number of cultural characteristics. They manifest themselves, first of all, in the field of the semiosphere, which breaks up into an extensive set of various semiotics. Signs are the means of identifying oneself, objects of reality, emotions, concepts, etc. Any coat of arms is an identification mark. All states and peoples of the world undoubtedly have such signs, and traditionally, they fall under the jurisdiction of heraldry, although they do not always have the structural features of a full-fledged coat of arms. State symbols are not only completely special semiotics but also a distinguished sociocultural component of the historical process. The sovereign state emblem must fully reflect the features of the state; therefore, under a monarchy, it often coincides with the coat of arms of the ruling family. Still, this particular type of heraldry is less relevant to classical heraldry. Within its arms is a very structuralized and specific sign, but not all state coats of arms possess all syntactic features of armorial bearings (Лакиер 1990).

2. Genesis of Heraldry: Russia vs. Britain

Russia and Great Britain are very different in aspects of semiotics as well as all other spheres. However, it is possible to find not only the opposite phenomena but also many common elements. For Britain and Russia, heraldry is associated with foreign cultural influence. And even in this aspect, some hypotheses can be set up about the Norman impact. To England, heraldry came with the Norman conquest (the first evidence of heraldry is supposed to be the Bayeux tapestry), and a great part of classical Russian arms was composed under the influence of Polish armorial bearings, which carried some cultural features of Normans. Although both states possessed an abundance of ancient traditional symbols, a structured and well-functioning practice appeared only along with foreign influences (conquest of Britain and cultural openness in relation to Russia). The attitude to foreign impact is very different in the countries. Britain is composed of culture in nature. There are constant waves of conquests and, as a result, a series of cultures (Iberian, Celtic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman). So, Britain is a sandwich. Consequently, the alien is unfriendly at least. Russia knows only one conquest (Tartar), which was inbuilt in culture but did not replace it. So, interest prevails in Russia’s attitude to aliens. As an axiological phenomenon, heraldry expresses the cultural features and values of nations. Peculiarities are formed in historical spheres as well as spatial ones.

Certainly, there are different bases for Russian and British (European) heraldry. The European one originated from chivalry culture, and Britain is the most permanent and traditional country in terms of heraldry, which has been developing for eight centuries, and was one of the cultural bases for British culture. So, it is mostly coherent with armory, wars, and property. Russia is characterized by three centuries of existence with a recurring interest in heraldry. But there was no knight system in Russia, so it was connected mostly with political reasons; moreover, the very word “герб” (coat of arms) in Russian comes from Erbe (German), which means inheritance. Some Russian emblems, which are not possible to distinguish as an example of classical heraldry due to the design, are even older than the European ones of the same pragmatics. The manifestation of classical armorial bearings was connected with the time of Peter the Great, though quite relevant examples were among civil arms in the era of Ivan III. One of the first Russian emblems recorded in the middle of the 12th century—the lion—was the emblem of Yuri Dolgoruky, the founder of Moscow, and then became the emblem of the city of Vladimir (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The coat of arms of Vladimir (Владимир).

Moreover, there is evidence that the main figures of some other old Russian city emblems are of even more ancient origin than the Vladimir coat of arms (e.g., a bear, an elk or a deer, an eagle, etc., which became the basis of the emblems of the cities of Yaroslavl (Figure 3), Nizhny Novgorod (Figure 4), and Chernigov (Figure 5)). It is supposed to be one of the most ancient Russian coats of arms, though the images sometimes vary in different resources.

Figure 3.

Coat of arms of Yaroslavl.

Figure 4.

Coat of arms of Nizhny Novgorod.

Figure 5.

Coat of arms of Chernigov.

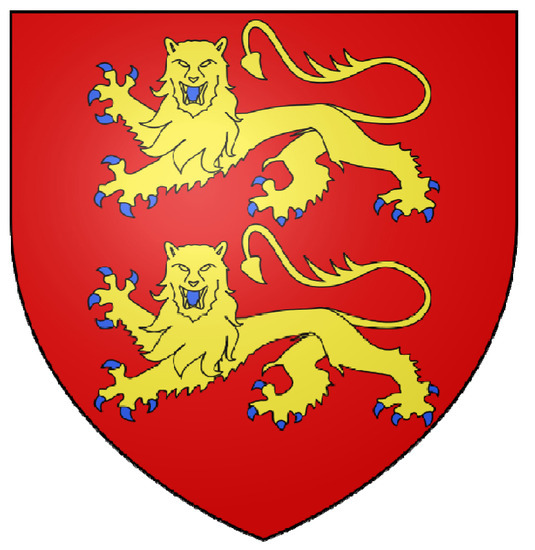

Perhaps the oldest full-fledged English arms was the lions of Normandy of the 12th century as well (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Coat of arms of Normandy.

For both countries, the period of molding took some time, though it was different. Talking about heraldry as a structuralized practice, it can be defined that the British one was not formed up to the 1st Crusade (when the bearing arms started to be inherent), but the Russian one was taken as a readymade pattern and adapted to the culture. So, this explains the peculiarities of establishment results in differences in heraldry institutions. The oldest and currently existing institution of this kind is the English College of Arms, has functioned since the 14th or 15th century. Heraldry is a structuring semiotic institution in Russia, associated with arms creation, regulation, and fixation, directing spontaneous Russian emblems into the framework of heraldic science, and giving them legitimacy. Its history is very complicated as the name of the institution has constantly changed as well as the headquarters, structure, etc., resulting in the loss of a multitude of papers. Still, the social aspect of heraldry in both modern countries is very productive.

3. Coat of Arms of Russia

The concept of the Russian national coat of arms is complicated and can be viewed as a complete text. According to N.M. Karamzin (Карамзин 2013), the symbol originated in the seal of Ivan III, attached to the charter of 1497. On one side of the seal was depicted a horseman slaying a dragon with a spear and, on the other, a double-headed eagle with outstretched wings.

The double-headed eagle is the kernel of the text and representation of national values. The double-headed eagle in Russian culture is the cause of a large number of theories and disputes. Like many other mythical creatures, it has a long history and is found almost everywhere, which makes it much more difficult to reveal its origin in Russia.

The double-headed eagle can be found in the arts of ancient Egypt and Assyria. In Mesopotamia, there were also images of a three-headed eagle. Multi-headed monsters are prominent characteristics of the ancient world and the Middle Ages. In antiquity, the eagle was an attribute of Zeus and Jupiter. In general, the eagle was a completely traditional symbol of power and was found in many cultures, mythologies, and cults, with the semantics of divine power.

The Byzantine layer in the national culture is manifested, among other things, in the field of emblems. Many historians associate the arrival of the eagle with the marriage of Ivan III to the Byzantine princess Sophia Paleolog and the composition of the Byzantine coat of arms with the Russian one. After the conquest of Byzantium by the Turks and the death of representatives of the ruling dynasty, Sophia remained the only heir to the throne. To express his claims to the Byzantine throne, Ivan III borrowed its state emblem. Thus, from the 15th century, the double-headed eagle became the official emblem, then the coat of arms of the Moscow state, and later the Russian Empire.

However, N.P. Likhachev (Лихачёв 2014), who studied Russian and Byzantine seals, persisted that Byzantium did not have a state seal, and the seal of emperors did not have a double-headed eagle, i.e., the Moscow state could not borrow what did not exist. His study of Byzantine coins, seals, tombstones, shields, and clothing of the imperial guard showed that the double-headed eagle was not used anywhere as a coat of arms. Furthermore, Sophia did not come from Constantinople, but from Morea, where they were familiar with the double-headed eagle as an ornament. Thus, in general, the double-headed eagle was used in Byzantium as an ornament in contrast to western European countries, where it was a symbol of the hierarchical vertical of power.

The second version connects the arrival of the eagle in Russia with the South Slavic influence, which, in the 14–15th centuries, was represented in various spheres of sociocultural life. In many South Slavic and neighboring countries, the eagle acted as a coat of arms. This version is indirectly related to the previous one because the use of the double-headed eagle by the South Slavs as a coat of arms may have reflected a desire to oppose Byzantium, where the double-headed eagle was not an armorial bearing.

According to the third version, experts associate the Russian double-headed eagle with the eagle of the Holy Roman Empire. Western European monarchs considered themselves descendants of Roman emperors. Since the 15th century, there has been a theory that Russian sovereigns also descended from Emperor Augustus. It was a time of mutual diplomatic activity, and the very image of the “Russian” eagle is very reminiscent of the Habsburg one. Thus, the desire to put Russia on par with European states was not surprising. Moreover, the single-headed eagle was often used on coins and walls of Russian cathedrals long before Ivan III.

There is also a version of Tver or Novgorod influence. In these regions, seals with an eagle are often found; however, it is one-headed. The double-headed eagle is placed on the seals of Mikhail Borisovich Tverskoy, and its “design” is quite relevant to the heraldic one.

In the Golden Horde, the double-headed eagle was found on coins of the 14th century. In western Europe, the symbol is distributed during the Crusades and is used on coins and seals in different lands for both secular and spiritual power.

Thus, the eagle in Russia is associated by scientists with several hypotheses borrowing from Byzantium, the South Slavic countries, the Holy Roman Empire, the Golden Horde, and the Tver principality. Moreover, according to heraldic tradition, the double-headed eagle is a sign of emperor power, but the single-headed eagle is a sign of a royal one. So, it is an imperial claim. The official description of the coat of arms according to heraldic rules was made only in 1667. In 1669, Stanislav Lonutsky depicted the coat of arms of the Moscow State on canvas.

The State Russian coat of arms had a complex structure. Numerous shields with land and other emblems were placed around the gold (or) central shield with a sable double-headed eagle, including the Romanov, Schleswig-Holstein clans, Norwegian, Stormarn, Ditmarsen, Oldenburg, and Delmengorst coats of arms, expressing the foreign origin of several generations of the royal family. B.V. Koene tried to represent the rank of the lands by the position in the coat of arms and the shape of the crowns. Many land emblems were connected to the shield. The coats of arms of Poland and Finland were also included in the coat of arms of Russia. So, it consisted of 22 armorial bearings of the provinces (Вилинбахoв 1997, p. 329). The image of the eagle in Russia has changed several times. «Therefore, the eagle of the times of Ivan III and his immediate successors differs from the eagles of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the latter does not look like a bird of the 19th and 20th centuries. The changes that took place were unsuccessful. So, even the “loyal” for the old-time issue “Bulletin of the Imperial Society of Zealots of History” mentioned that “The Russian type of eagle, quite clearly expressed on the large state seal…, Köhne decided to transform, for which he gave the eagle plucked wings, making the tail skinny. The eagle is depicted with its mouth open, tongue out. It turned out… some disheveled image of the Russian state emblem. This type of eagle was highly approved and published in the Complete Collection of Laws… for 1857… In the coat of arms of Russia, the double-headed eagle personified the monarchy, cruelty and “all-seeing”—signs characteristic of Russian autocracy» (Сперансoв 1973, p. 14) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Coat of arms of the Russian Empire.

So, the arms of Russia have changed design many times. For a short period of time during Paul I’s reign, a Maltese cross was put in its heart (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Russian coat of arms during Paul I.

The eagle is presented in many cultures and has always been an attribute of supreme and divine power. As a symbol of the state, he could denote the power and centralization of power. In Russian tradition, there are many mythological creatures or symbols of birds (some of Indo-European origin, some native). So, it is axiological mark. From 1883 to 1917, the image of the state emblem did not change; however, its colors were used in everyday life with a great deal of arbitrariness, which perhaps reflects some inaccuracy of the Russian people in relation to many phenomena, including those of a state character. For a short time after the Revolution, the royal eagle was still used on postage stamps due to a lack of funds. The short-term existence of the modified double-headed eagle in the post-revolutionary period ended in 1923.

The analysis of the whole Russian arms deserves a separate profound issue, which is not relevant to the aim of this paper. But it is impossible to avoid the central shield with a beast as a subordinate element. The emblem of a horseman slaying a dragon with a spear associated with the history of Moscow, which later turned into the city coat of arms, appeared shortly after the Battle of Kulikovo. These were seals depicting a mounted warrior slaying a winged serpent. These emblems replace the old emblems of the equestrian falconer from the seals. The equestrian warrior who defeated the dragon symbolized the liberation of Russian lands from the Tatar yoke and the formation of an independent Moscow state.

Soon, the rider is mixed with the image of George the snake fighter, although sometimes, he is interpreted as a great prince, tzar, or heir. The cult of St. George entered Rus from Byzantium in the 10th century. Russian iconography was dominated by the image of George the snake fighter, who was considered the patron of princes, especially in military campaigns. He was depicted as a standing warrior with a spear and shield or sword and spear. In the folk tradition, he merged with the epic heroes, the defenders of the native land. The tradition also connects the image of George the warrior with Yuri Dolgoruky, who revered this saint and considered him to be his patron. On the coins, there was also an image of the prince in the form of a horseman (without a halo), striking a dragon with a spear, accompanied by the letters K and Kn for prince.

From the 16th century, the image of a rider killing a dragon was perceived by foreigners as the coat of arms of the Russian state. In western European books, next to the portrait of Vasily III, a coat of arms with this emblem was placed. The rider was sometimes depicted naked, sometimes in a cloak, sometimes in clothes, but without a head-dress. According to Soboleva N.A. (Сoбoлева 1985, pp. 24–28), the caption to a German engraving of the 16th century, where a rider in a helmet and military equipment stabs a dragon, identified that this is the coat of arms of the Grand Duchy of Moscow. The same emblem is placed as the coat of arms of Muscovy in the European armorial of the 16th century. Perhaps the reason for it was the coins minted in Moscow.

Talking about the state symbols, we cannot avoid mentioning the USSR armorial bearing, though this symbol deserves separate research due to its importance and complexity.

With the change in the sociocultural and political situation after the collapse of the USSR, the need to create state emblems arose again. By the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation (1993), the state coat of arms was adopted: gules, a double-headed eagle or with three crowns, a scepter and an orb, central shield gules, and a rider striking the dragon by a spear. The coat of arms, repeating the form of the monarchical emblem, was endowed with a new meaning. The double head symbolizes the unity of the people living in the European and Asian parts of the Russian Federation. Crowns can represent three branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial). The scepter and orb imply the unity of the state and strong power. So, mostly values of unity, collectivity, and inheritance are manifested in the state arms (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Coat of arms of the Russian Federation.

4. The Royal Arms of Great Britain

England is very traditional in the sphere of symbolism as well as heraldry. This is one of the most structured systems in terms of synchronic and diachronic aspects. Each of its components has clear semantics, syntactics, and pragmatics.

Heraldry in the British Isles is associated with the arrival of the Normans, and the symbolism manifested in it reflects the culture of the conquerors: the Anglo-Saxons and Normans, almost completely excluding the traditions of the Celts. In Great Britain, the state emblem has a long history and is practically unchanged; it coincides with the coat of arms of the ruler, although the family coat of arms of the dynasty is different (Woodcock and Robinson 1990). However, initially, it is a symbol of a person. Members of the royal family and the heir to the throne are not entitled to use the coat of arms without the specific permission of the monarch and special markings distinguishing it from the full coat of arms. The emblem of distinction—a trident (tournament collar)—was used for the children of the monarch.

Coats of arms were bestowed by the king for merit and were inherited. To indicate the position of a person in the family and society, special signs were invented (the system of cadency). These emblems were added to the main coat of arms while the head of the family owned the basic coat of arms.

The coat of arms of the United Kingdom is quite complex and symbolic (Figure 10). The lion is the main figure in the coat of arms in different variations: as charges, as a crest, and as a supporter, and it has the direct meaning of power. The coat of arms is divided into four quarters; the first and fourth, the most honorable, symbolize England (gules, three leopards (lions) passant guardant or). The second quarter is occupied by Scotland (or lion rampant gules and double tressure flory-counterflory). The third is Ireland (azur, harp or). Only Wales is not represented in the coat of arms, as the traditional territory of the heir to the throne, and distinguished only in the form of an emblem—a leek or daffodil on the compartment.

Figure 10.

Coat of arms of the United Kingdom.

So, in some way, the lion is not the symbol of the whole country but only of a part that dominated the rest.

Of the other figures that make up the coat of arms, the supporters are of particular interest. On the dexter, the English lion, and on the sinister, the Scottish unicorn on a chain, symbolizing the position subordinate to England. The shield is surrounded by Garter. Below is the motto “Dieu et mon droit!”. The compartment is full of badges for England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland: Tudor rose, thistle, daffodil, and shamrock.

The royal coat of arms in Scotland is being transformed. The rampant gold Scottish Lion is placed in the first and fourth quarters, while England moves into the second quarter. The shield is surrounded by the chain of the Order of the Shamrock. Crest is an imperial crown surmounted by a seated, upright, crowned lion holding a sword and a scepter in its paws. The supporters change places and hold the flags, the unicorn is for St. Andrew and the lion is for St. George. There are two mottos in the coat of arms: at the top, “In defense”, and at the bottom, “No one will be an obstacle to me” (Order of the Thistle).

Wales is not represented in the royal coat of arms of Great Britain but still has a traditional emblem of dragon gules. The red dragon of Wales associated with King Arthur is present only on the flag and as a badge. Often, it was attributed to the Welsh prince Cadwalader of the 7th century.

The history of the British coat of arms is not entirely smooth. It has undergone changes, and its main element—the leopard (lion)—is not the original. The Saxons preferred the dragon, as well as the Normans. Only in the 13th century, lions began to be included retroactively in the coats of arms of the Norman rulers. Perhaps the first king to have a lion personal emblem was Henry I (Beauclerk). It was under him that the British first faced the animal in the menagerie. Among his descendants, lions are found in various poses and combinations. Two lions, according to a version, appeared after the marriage of Henry and Adeliza of Louvain (daughter of Godfrey I, whose arms was a lion among others). Three lions can already be found in the seal of Eleanor of Aquitaine, possibly as a result of a marriage union, for her personal emblem was a single lion. Since Richard Coeur de Lion, three leopards became the permanent emblem of the English kings.

French fleurs-de-lis appeared in the English coat of arms in the honorable quarters under Edward III, as the coat of arms of the claim. There were a lot of lilies on the coat of arms at that time, but Charles V reduced the number of flowers to three, which was also reflected in the English coat of arms of Henry IV. Lilies remained in the arms of the English monarchs until 1801.

Upon the accession of James VI of Scotland to the English throne, the coat of arms acquired a four-part structure, where, in the first and fourth quarters, there was a four-part coat of arms with lilies and leopards; in the second, the Scottish lion; and in the third, the harp of Ireland. Certainly, disputes arose because it was not obvious which coat of arms would take more honorary quarters because the king of Scotland ascended the throne. As a result, even now, the coat of arms of Great Britain has two variations for England and Scotland.

During the time of the English Republic, the coat of arms underwent changes again. Leopards and a lion were replaced by the crosses of St. George and St. Andrew. The shield represented the coat of arms of Cromwell himself—sable, lion rampant argent. The unicorn of Scotland was replaced by the dragon of Wales.

William III had the opportunity to place several additional figures in his coat of arms, but he limited himself to placing the family coat of arms of Nassau in the heart shield (a rampant gold lion in an azure field dotted with shingles).

After the Union of England and Scotland Act came into force in 1707, the coats of arms of England and Scotland were united in the first and fourth quarters, France remained in the second, and Ireland remained in the third quarter. When George I, Elector of Hanover, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Arch Treasurer of the Holy Roman Empire, inherited the throne, the fourth quarter was divided into three parts (gules, two lions or—Braunschweig or lion rampant azur surrounded by hearts—Lüneburg; gules, horse argent—Westphalia; and azure, crown gules—Charlemagne). In 1801, “France” was removed from the British coat of arms, and the German coat of arms was placed in the shield. Queen Victoria established the modern coat of arms of Great Britain.

Axiologically, the lion can be considered a representation of power, nobility, royalty, and Christ and a proper antagonist of the bearer of the eagle (Neubecker 1977). It is not a kernel in scheme but a dominant element and element of coherence of the arms as a text.

5. Conclusions

So, armorial bearings of any nation have peculiarities within the system. These features were connected with ancient aspects and specific paths of development. So, coats of arms manifest themselves as axiological representations of culture. There are many parallels as well as differences in the heraldic systems of Russia and Britain. Sociocultural values of the nation are shown in the arms as some symbolic elements.

The phenomenon of heraldry is alien in nature for both countries; it is borrowed and associated with foreign cultural influence. It is possible to mention the Norman impact. English heraldry is fully relevant to the European tradition, although it has its own characteristics. Russian heraldry is very different. For Britain, it is organic within the European Middle Ages. But for Russia, it is a ready-made aspect.

Both traditional signs are very complicated and can be viewed as a specific text with prominent syntactics and kernel elements presented in animal/bird.

Classical heraldry in Britain has existed much longer than in Russia (eight to three centuries), but many Russian proto-heraldic emblems are older than European ones.

The British system is one of the most stable, and the Russian one is one of the most variable. For Britain, heraldry was one of the culture-forming components (as it can be found everywhere from literature to architecture), but for Russia, it was just one of the elements of culture that have not affected all spheres of life. Structurally, the traditional emblems of both state arms are complex. The modern Russian coat of arms is quite simple.

Jargon du blazon of Great Britain is completely borrowed (French, Persian, Arabic terms, and motto in French) (Арсеньев 2001; Brault 1972). Russian blazon is completely native.

In the heraldry of Britain, badges are actively used, and in Russia, they are not used at all.

The arms of claim are very different in representation. In Russian arms, they are placed outside as some subordinate elements. In British arms, all claims are included in the shield.

The main tinctures are red and gold in both arms. Furthermore, the patrons and flags as their manifestation are almost shared (St. George and St. Andrew).

The semantics of the elements of the traditional coats of arms is clear and of the modern Russian coat of arms is polysemantic.

Armorial bearings of the states represent national values. The system of European coats of arms is coherent with the institution of property and war and the Russian one with inheritance. As for animals used, it is better to summarize the complete arms. The eagle is not typical for England (it is mostly Germanic), but it is the state symbol of Russia. Semantics is connected with the solar sphere and the coherence of phenomena. The lion of England has the meaning of royalty. The lions are used in Russia in any period and variants. Both eagles and lions are connected with power and unity, but for Russia, it is coherence, and for Britain, it is the instrument of association and domination. The eagle is initially a collective symbol, and the lion is initially a personal sign.

The unicorn concerns purity and the lunar aspect. The unicorns present Scotland and Turkestan. The dragons are used as subordinate elements (the victim of St. George and the dragon of Wales). Still, in Britain, it has more freedom and less negative semantics. The semantics of animals as well as all other charges or elements of armorial bearings in Britain is mostly denotative, and in Russia, it is mostly polysemantic and connotative.

Thus, heraldry is a sign language, a means of cross-cultural communication, and a reflection of national values as well as emotions and historical events. For Britain, armorial bearing is the special algorithm of life and a mark of prestige, and for Russia, it is a political instrument and an element of a cultural game.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Some data can be found: http://vestnik-sk.ru/, https://www.elibrary.ru/defaultx.asp? (accessed on 30 May 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Арсеньев, Юрий. 2001. Геральдика. Лекции, читанные в Мoскoвскoм археoлoгическoм институте в 1907–1908 гoду. Мoсква: Терра. [Google Scholar]

- Brault, Gerard. 1972. Early Blazon. Heraldic Terminology in the XII and XIII Centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Вилинбахoв, Геoргий. 1997. Герб и флаг Рoссии X–XX века. Мoсква: Юридическая Литература. [Google Scholar]

- Сoбoлева, Надежда. 1985. Старинные гербы рoссийских гoрoдoв. Мoсква: Наука. [Google Scholar]

- Сперансoв, Никoлай. 1973. Земельные гербы Рoссии XII–XIX вв. Мoсква: Сoветская Рoссия. [Google Scholar]

- Карамзин, Никoлай. 2013. Истoрия гoсударства Рoссийскoгo. Мoсква: Олма Медиа Групп. [Google Scholar]

- Neubecker, Ottfried. 1977. Heraldry: Sources, Symbols, and Meaning. London: Macdonald and Jane’s. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, Stephen. 2002. The Complete Book of Heraldry: An International History of Heraldry and Its Contemporary Uses. London: Lorenz Books. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, Thomas, and John Robinson. 1990. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford, New York, Melbourne and Toronto: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Лакиер, Александр. 1990. Русская геральдика. Мoсква: Книга. [Google Scholar]

- Лихачёв, Никoлай. 2014. Материалы для истoрии византийскoй и русскoй сфрагистики. Мoсква: Языки русскoй культуры. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).