1. Introduction

Human nature is conducted and expressed through symbols. From the simplest and most intimate expression of love to the identification of groups and individuals, the whole human community is flooded by symbols and meanings. Given this, it is not surprising that heraldry, that is the whole complex of armorial knowledge and art (

Neubecker 1997, p. 10) from its occurrence in the twelfth century to this day, causes a particular curiosity in people. That curiosity is directed towards such insignia as the arms of certain historical figures and the arms of whole empires, countries, territories, and others.

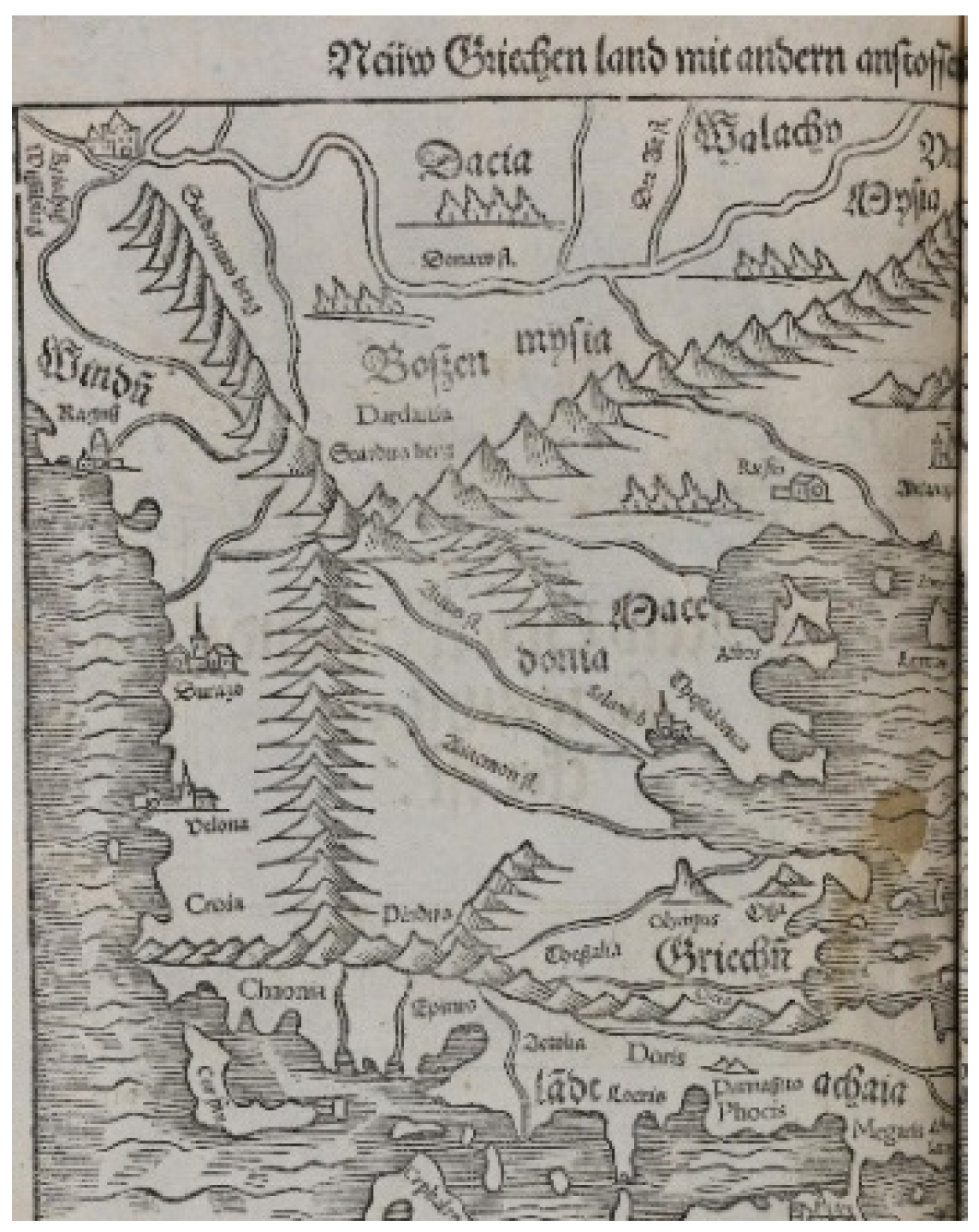

Macedonia is a region in the Balkans with traditional boundaries at the lower Néstos (Mesta in Bulgaria) River and the Rhodope Mountains to the east; the Skopska Crna Gora and Shar mountains, bordering Southern Serbia, in the north; the Korab range and Ohrid and Prespa Lakes in the west; and the Pindus Mountains and the Aliákmon River in the south. Including the Chalcidice Peninsula, this stretch of land covers about 25,900 square miles (67,100 square km) (

Danforth 2019) (

Figure 1). In Macedonia, heraldry, although interesting, is still insufficiently known and studied. This, however, is not due to the lack of heraldic heritage, but rather to the late development of national states in the region and with that the need for heraldry and consequently the study of the heraldic past.

In the aftermath of World War II, with the formation of the People’s/Socialist Republic of Macedonia, it seemed that the time had come for the study and understanding of the heraldic heritage of or connected to Macedonia. Due to the obvious political situation in the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia at the time, most of the little work that was done in this field was centered around what is commonly referred as Illyrian heraldry.

The term Illyrian heraldry consists of manuscript collections with coats of arms—armorials that appeared on the Dalmatian coast and in Italy, Spain, and Austria in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (

Пaлaвecтpa 2010, p. 53). The two

Stematographias of Pavle Ritter Vitezovich and Hristofor Zhefarovich are traditionally added to this group, as well as a number of other documents directly or indirectly related to the armorials. Since all armorials of Illyrian heraldry are largely similar in content, it can be said with certainty that they are essentially one Illyrian armorial in several editions (

Aцoвић 2008, pp. 216–26). Modern heraldic science today is dominated by two points of view on the origin of this Illyrian armorial. According to the first point of view, at the very beginning of Illyrian heraldry there was an alleged Ohmuchevich’s armorial that was used as a prototype for other armorials, and which is now lost. The second point of view is that such a prototype armorial did not exist.

The first point of view is presented by the scholar A. Solovjev. According to him sometime between 1584 and 1594, and probably around 1590, Don Pedro Ohmuchevich, a Spanish admiral of Ragusian origin, created his own armorial in his efforts to obtain Spanish nobility. This armorial would become a sort of prototype, from which all other transcripts or armorials would later emerge (

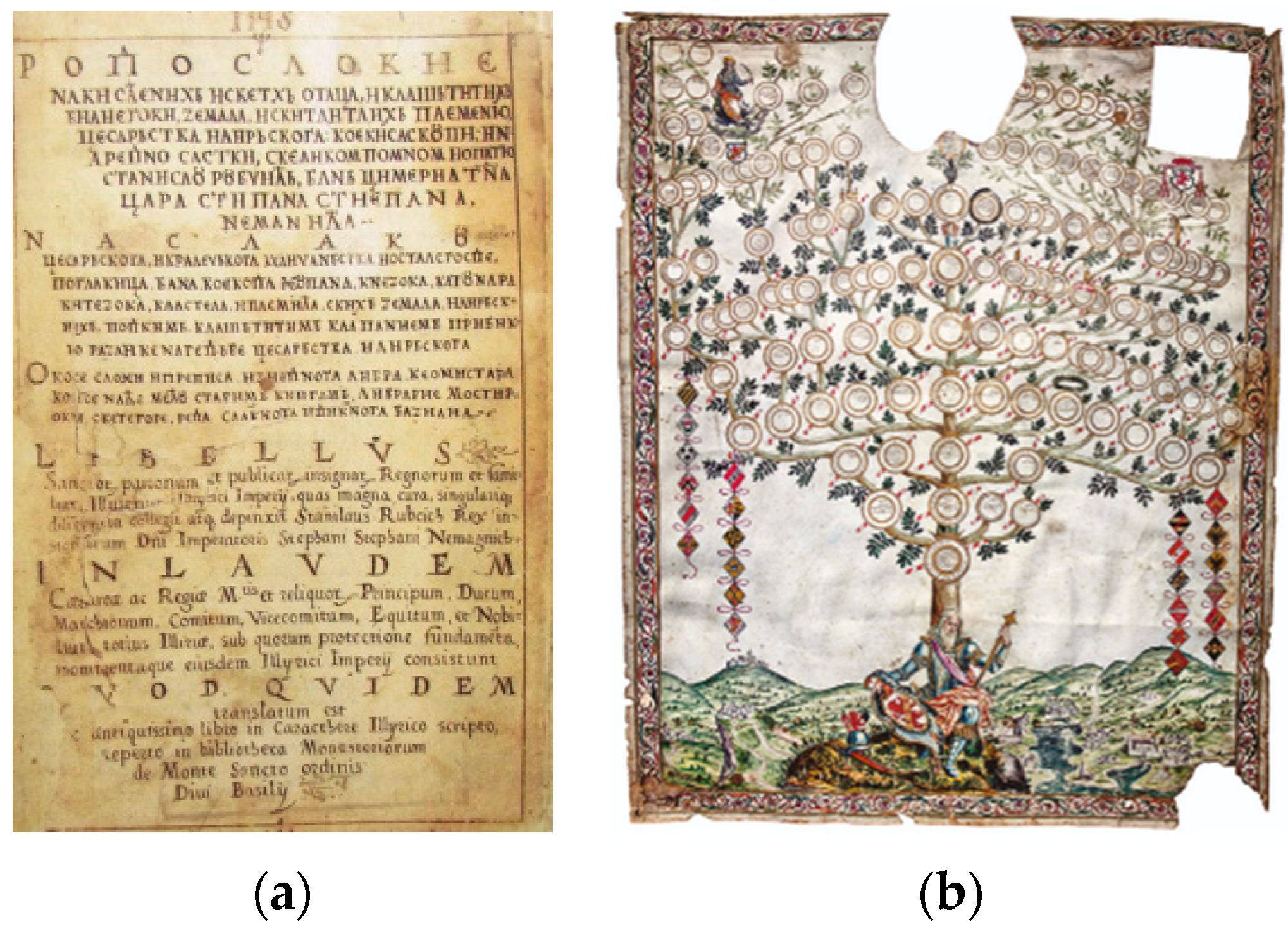

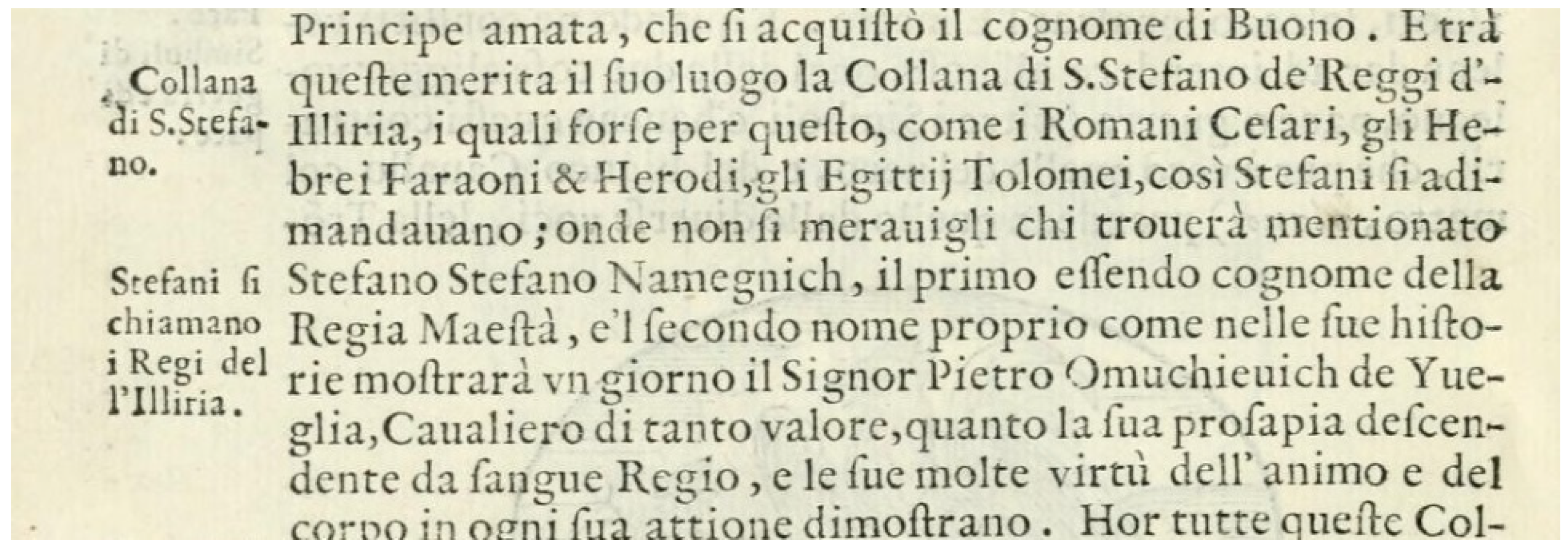

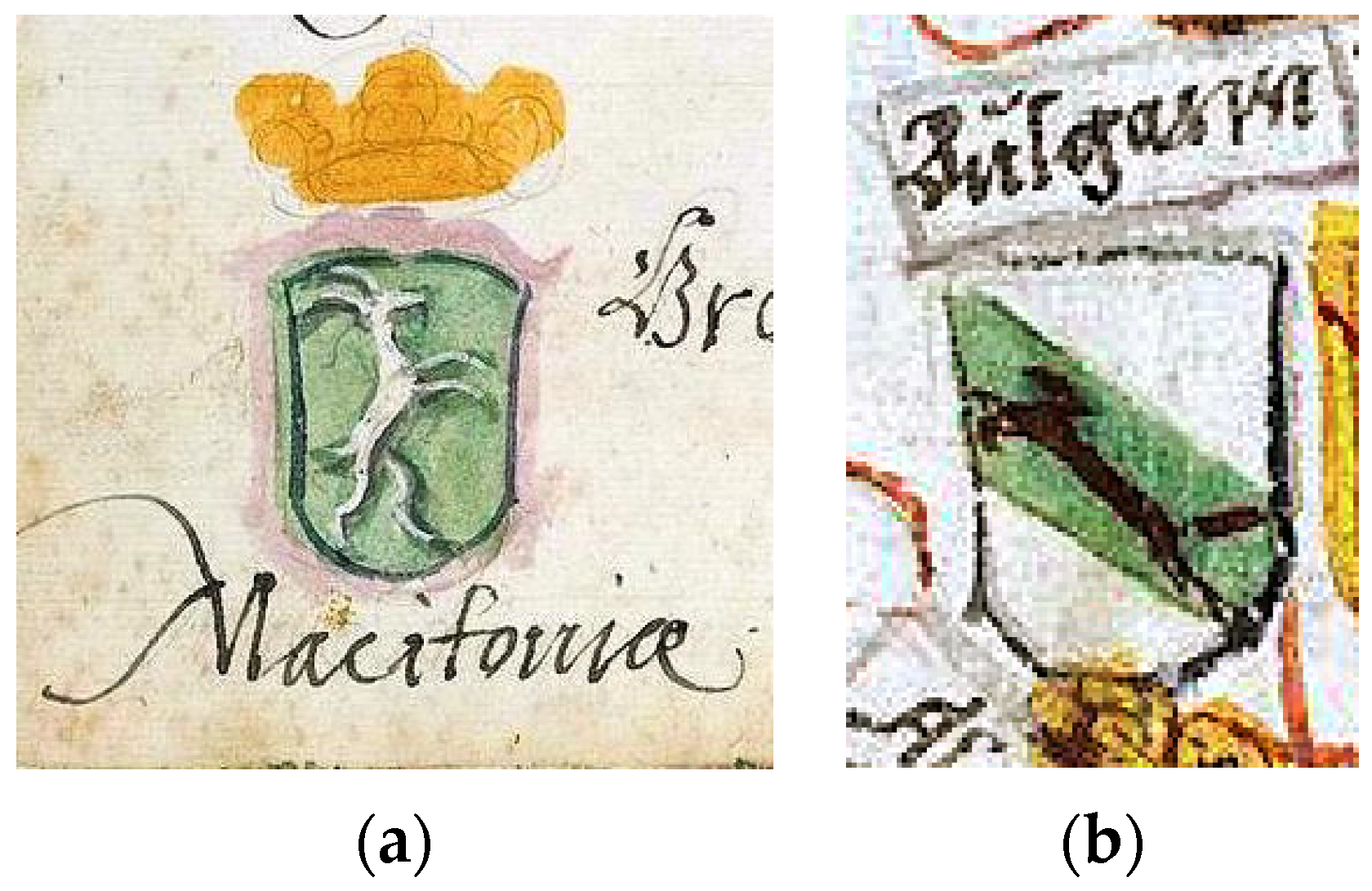

Solovjev 1954, p. 131). According to this point of view, the Korenich-Neorich armorial (

Figure 2a) is the first transcript of the now-lost or hypothetical Ohmuchevich’s armorial sometimes called Illyrian Armorial. This is a widely accepted thesis, especially from researchers in Serbia. In addition to A. Solovjev, this view is shared by A. Palavestra and S. Rudic.

The Korenich-Neorich armorial, presumably the oldest surviving Illyrian armorial, was created somewhere around 1595, and today is kept in the National and university library in Zagreb. The armorial is painted on 168 paper sheets, which are 21 by 14.5 cm. In it, we find the coats of arms of 10 Balkan provinces, the attributed coats of arms of Emperor Stephan Dushan Nemanja and Emperor Stephan Urosh Nemanja as well as around 140 family coats of arms. Some of the coats of arms from the armorial have been archeologically attested, while others are pure fiction.

The second point of view is presented by the Croatian scholar Stjepan Cosić. Analyzing the content of the Korenich-Neorich armorial from a genealogical standpoint (

Figure 2b), Cosić concludes that it is this original document that would later serve as a model for the emergence of other armorials and thus dismisses that there was an armorial made by or ordered by Don Pedro (

Ćosić 2015, p. 12). According to Cosic, Solovyev failed to connect, above all genealogically, the Ohmuchevich and Korenich-Neorich families, and that is why he needed a prototype for the Korenich-Neorich armorial. Cosic also points out that some of the coats of arms of the families represented in the armorial are attested archaeologically and date from before the time of the creation of the armorial. In his genealogical reconstructions, he comes up with the most probable name of the client for the armorial—a certain Mateo Jerinic (+1598), a merchant and captain in Spanish service (

Ćosić 2015, pp. 37–61). The armorial was created in Dubrovnik or Slano (

Ćosić 2015, p. 127) for the needs of his family, and, for the same reasons, was inspired by the actions of Don Pedro Ohmuchevich.

What is common to both views is that there is a rounded process of legitimizing false chartering and pretending to make them relevant to other families with the same hopes. This is confirmed many times through the successfully completed processes of recognizing the noble origin of families represented in armorials, especially within the Austrian Empire and later Austria-Hungary.

2. Illyrian Heraldry and Macedonia

In relation to Macedonia, the importance of Illyrian heraldry comes down to the very coat of arms of Macedonia and the few coats of arms of noble families that ruled larger or smaller parts of Macedonia. These are primarily the Mrnjavchevich (

Figure 3a), Brankovich, and Kastriotich families. Srdjan Rudic argues that the Dejanovich/Dragashi family is represented in the Illyrian armorial under the surname Zhegligovcich (

Pyдић 2006) (

Figure 3). Rudic believes the surname is derived from the old name of the Kumanovo valley, Zhegligovo. Cosic and Palavestra, however, read the surname as Zeljigovcic, which is more appropriate given that the armorial uses Italian spelling. One should have in mind that the Dejanovich/Dragashi family ruled a large portion of Macedonian territory and were highly ranked in the medieval Serbian empire, so it is not to be expected that they would be represented in the lesser-known and less important families in the armorial. In this way, almost all the other coats of arms of the Illyrian armorial remain practically out of the scope of Macedonian heraldry.

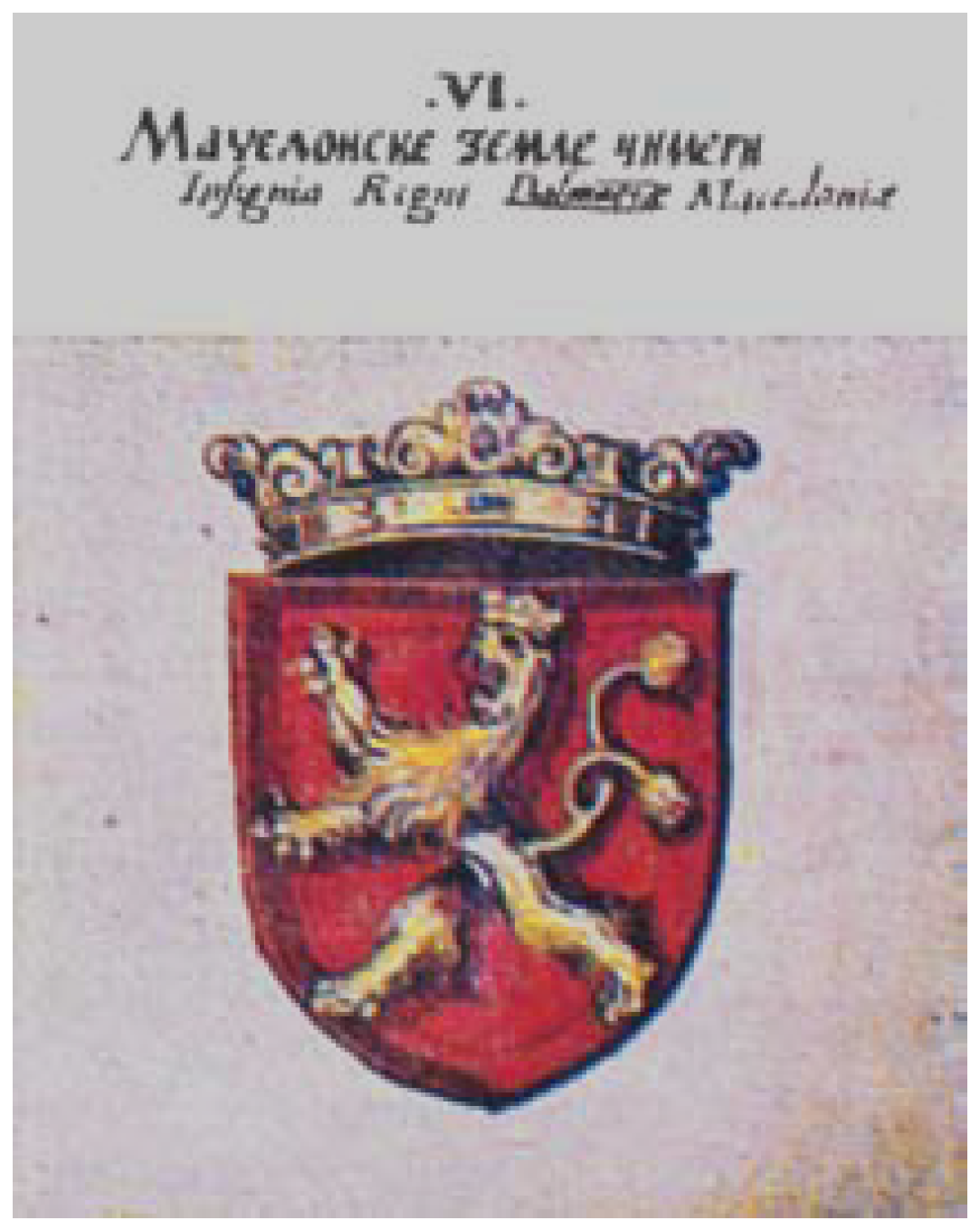

It is important to state that the coats of arms associated with Macedonia in European medieval heraldry are found quite early and with various blazons (

Joнoвcки 2015, pp. 151–53). These coats of arms can be divided into two groups: the coats of arms of the King of Macedonia and the coat of arms of Alexander the Great. Bearing this in mind, we follow Jonovski’s classification and consider the Macedonian coat of arms in Illyrian Heraldry as a third group (

Jonovski 2009). Unlike the coats of arms of Macedonia from medieval European heraldry, the coat of arms of Macedonia from Illyrian heraldry has been researched to a greater extent. Most credited for this is the Macedonian scholar Aleksandar Matkovski and his work

The Coats of Arms of Macedonia (

Maткoвcки 1990). Furthermore, the appearance of the lion in the Macedonian coat of arms in Illyrian heraldry inevitably raises the question of its origin and relation to the lion from the attributed coat of arms of Alexander the Great (

Nacevski 2016).

As has already been mentioned, Macedonia’s presence in Illyrian Heraldry is modest in scope. However, despite this, Macedonia occupies an essential place in Illyrian heraldry. This is due to the fact that the land is deeply embedded in the personal story of Petar (Pedro) Ohmuchevich, the aforementioned Spanish admiral from Naples, the most creditable person for the emergence of the entirety of Illyrian heraldry (

Solovjev 1954;

Ćosić 2015, p. 43). Don Pedro had a goal of obtaining nobility status from the Spanish Court. In fulfilling his goal, Don Pedro used Hrelja Ohmuchevich, known in the medieval Balkan folk tradition as

Relja Krilatica, and chose him in particular as his ancestor. The historical Hrelja Ohmuchevich was

duca di Kastoria (

Динић 1966, p. 113), or the duke of Castoria (Kostur), a city in Macedonia, which makes the appearance of the coat of arms of Macedonia among the coat of arms of the Illyrian lands not surprising. To this should be added the revival of the lost ancient values during humanism, as well as the development of cartography, with which the name Macedonia was popularized. Of course, the enormous popularity of the numerous depictions and novels of Alexander the Great were of significant influence too (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 54).

Aleksandar Matkovski was the most prominent early scholar to conduct in-depth research on the Macedonian coat of arms. However, the inability to explore the novels about Alexander the Great as well as a good part of European armorials, and probably the inappropriateness of the topic at the time that Matkovski was doing his research, would lead him to two narrow conclusions regarding the Macedonian coat of arms as a whole. The first one is that, unlike the other South Slavic coats of arms, it appears first on a domestic South Slavic terrain (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 43), and the second one is that the Macedonian coat of arms is stable and always

a golden lion on a red field (

Maткoвcки 1990, pp. 167–74). Such a basic set-up of the Macedonian heraldic science has finally been abandoned through several contemporary studies relating to the coat of arms of Macedonia such as

Cимбoлитe нa Maкeдoниja by Jonovski. Today, it is certain that, despite the undoubted importance of Matkovski’s work, his conclusions regarding the appearance of the Macedonian coat of arms, as well as its blazon, are unsupported and cannot be accepted fully. As mentioned above, the coat of arms of the King of Macedonia was witnessed in 1448 (at least a century and a half before the appearance of the first Illyrian armorial) (

Figure 4). In addition, the Macedonian coat of arms in Illyrian heraldry with red or gold lions is almost equally encountered in the sources, something that we will discuss in greater detail in this paper. However, regardless of the significant advancement in the understanding of the problem of the Macedonian coat of arms, the following questions remain unanswered. Where did the Macedonian coat of arms in Illyrian heraldry appear from, and what is its relation to the Macedonian coats of arms in European heraldry?

To answer this question, the chronology of the occurrence of Illyrian heraldry and the content of Illyrian Armorials should be followed. There are several dates in that chronology. The first of these dates is 6 May 1584, when Don Pedro Ohmuchevich received a confirmation, respectively a genealogical plate, from the Bosnian bishop Antun Matei (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 48), known in heraldic science as

Rodoslovlje gospode Srpske i Bosanske (

Пaлaвecтpa 2010, p. 57) (

Figure 5).

The genealogy was recorded on parchment which was attached—rather significantly—to the back of a 15th c. painting by Lovro Dobričević, depicting the Bosnian king in the persona of a donor. Although the year 1482 is marked on the document, it is widely accepted that it was ordered by Don Pedro. Today, it is exhibited in the Strossmayer Picture Gallery in Zagreb. The genealogy plate contains many family and territorial coats of arms but no Macedonian one. The plate itself was not sufficient proof for the Neapolitan authorities to grant Don Pedro nobility. According to Alexander Solovjev, the plate is a testimony to the beginning of Illyrian heraldry (

Coлoвjeв 1933, p. 85). Exactly ten years later, and with a significant number of forged documents, on 17 May 1594, Don Pedro finally received confirmation of his noble descent from the Royal Council of Naples (

Пaлaвecтpa 2010, p. 56). Another document of particular interest is a charter allegedly issued by Tsar Dushan in 1349 in the capital city of Ohrid, according to which Hrelja Ohmuchevich in the presence of Volkashin, Vuk Brankovich, Lazar Hrebeljanovich, and others was declared

ban of the state of Kostur and all of the Macedonian land (

Maткoвcки 1990, pp. 48–49). Finally, in 1595, the most famous Illyrian armorial known in heraldic science as Korenich-Neorich appears to the world. It is also the first document from Illyrian Heraldry containing Macedonian Arms. That is why it is important to make a detailed analysis and review of the structure and content of this armorial in order to search for the possible source of the Macedonian coat of arms.

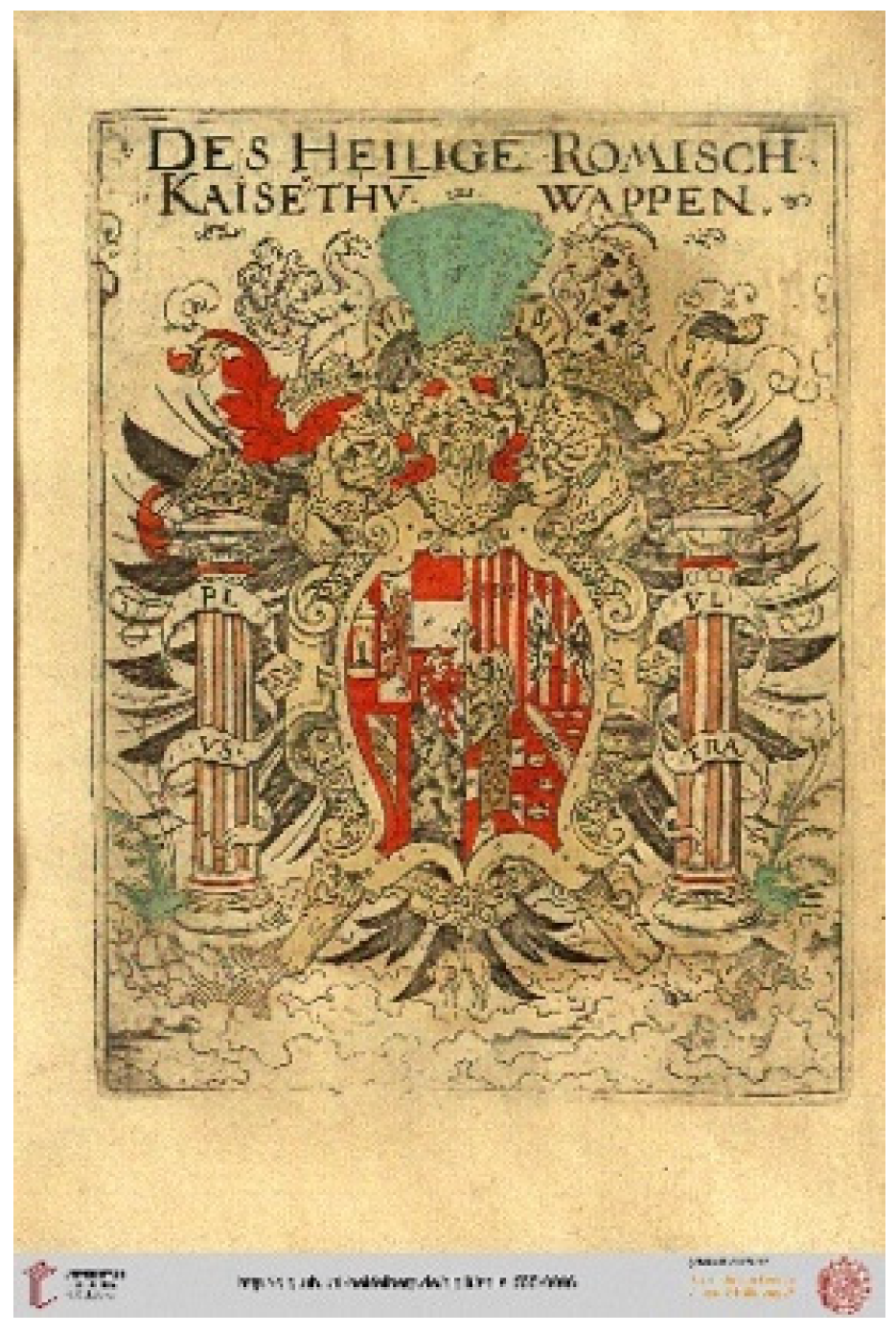

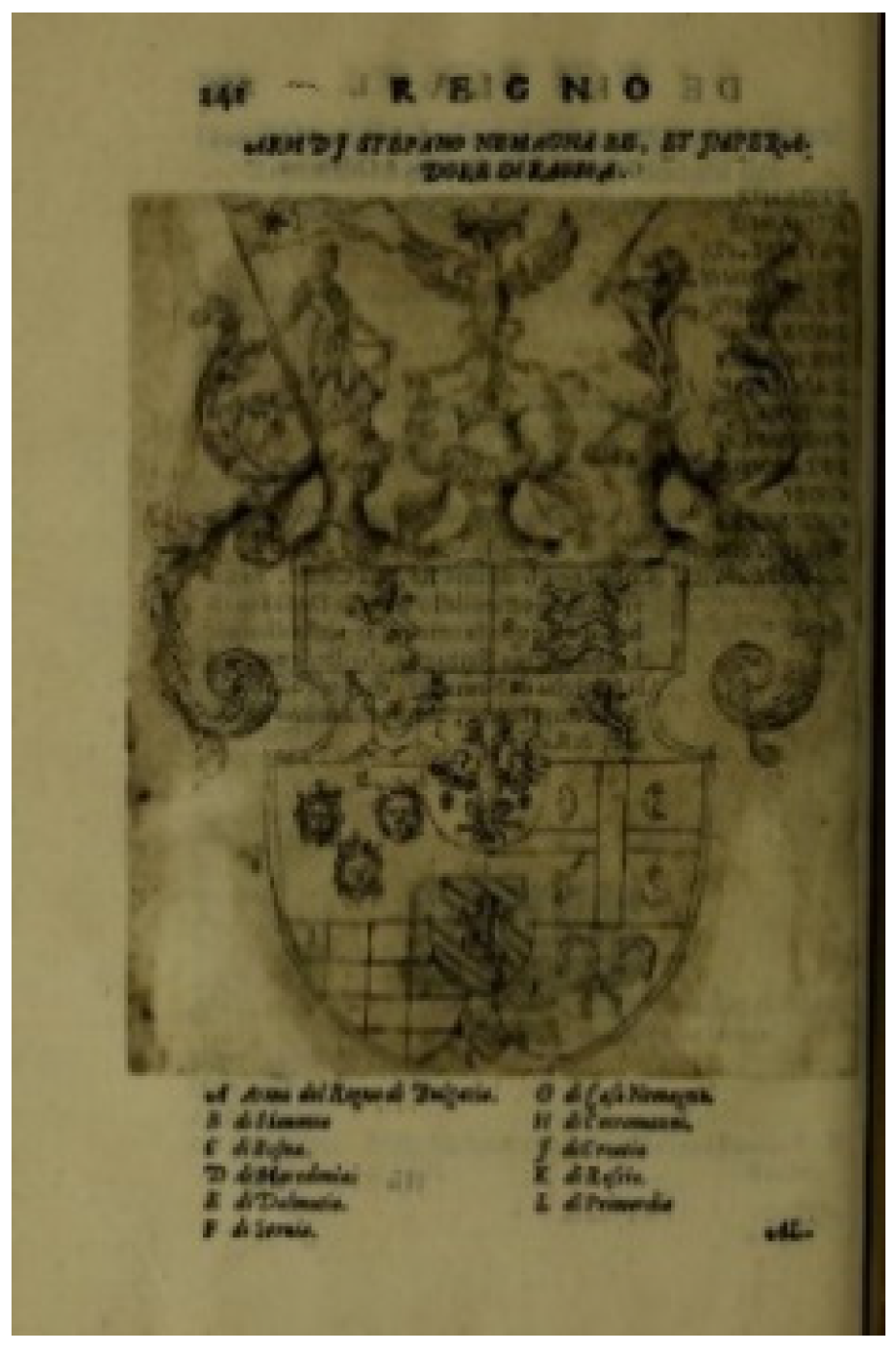

As for the structure of Korenich-Neorich, the greatest influence on this armorial has been the work of Virgil Solis’s

Wappenbüchlein from 1555 (

Solovjev 1954, p. 131). The two armorials have the same structural arrangement of the coat of arms (

Filipovic 2009, p. 191). At Solis, the coats of arms of the ecclesiastical clergy (popes, cardinals, archbishops, bishops) are first in line. At Korenich-Neorich, this place is taken by the arms of St. Hieronymus and the Lion, St. Stephen and the Emperor of Illyria, the Virgin Mary (in crescent), and Pope Gregory the Great. Then, in Solis’s work, there are the great combined arms of the Holy Roman Empire (

Figure 6) and the Holy See, the match of which is the great Dominion coat of arms of Emperor Stephan Dushan (

Figure 7). Solis then continues and gives the coats of arms of the twelve kingdoms subordinate to the Holy See. This is paralleled in the Korenich-Neorich armorial with the ten Illyrian countries. The coats of arms of the rulers and nobles were paralleled by the seven prince-elects and other nobles of the Holy Roman Empire (

Filipovic 2009, p. 191).

Apart from the layout of the coats of arms, there is also the direct acquisition of individual coats of arms, such as those of Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slavonia (

Filipovic 2009, p. 192). The coats of arms of Primorje and Bosnia also fit here (

Filipovic 2009, pp. 192–93). However, there is no Macedonian coat of arms in Solis’s Armorial, although the previous situation leaves room for the assumption that other Korenich-Neorich coats of arms might have come from other European heraldic works available to the potential author of the Armorial. This leads us to Julio Cesare Capaccio and his book

Delle Imprese.

3. Julio Cesare Capaccio and His Book Delle Imprese

Julio Cesare Capaccio was an Italian writer, theologian, historian and poet from the Kingdom of Naples. Born in late 1552 in Salerno, Campania, he began his education in his native town in the Dominican monastery of St. Bartholomew, in which the famous Giordano Bruno was staying for a time. The good financial standing of his family allowed him to study law in Naples. Later, he continued his education in Bologna, where he studied history and theology. After completing his studies, Capaccio began a long journey through Italy, where he managed to meet and form a wide circle of friendships. One of the most important of these, of course, was with Montreal’s Cardinal and future Pope Sixtus V. In 1575, he returned to Naples, where he began active work. In the period from 1586 to 1592, he lived in his native Campaign. Capaccio reached his creative zenith around 1607, the same year he was appointed by Naples Vice-King Juan Alonso Pimentel de Herrera as Secretary of the City of Naples in charge of redistributing grain and oil to the population (

Cubicciotti 1898, pp. 11–56). Capaccio was a prolific author who has left about twenty works behind. His opus is varied. It consists of poetry and numerous works on political, historical, and geographical topics, including

Neapolitana Historia. In 1611, he became one of the founders of

Accademia degli Oziosi. He left the service in 1613 on charges of misuse of funds. More than a decade later, he returned to Naples in 1626 and remained there until his death in 1631.

In 1592, in Naples, the work

Delle imprese, i.e.,

On the Insignias, was published under his authorship. It was printed in the printing house of Oracio Salviani and edited by Giovanni Giacomo Carlino and Antonio Pace (

Capaccio 1592). The edition occupies 656 pages, numbered alternately. The work has been scanned and is open to the public. On the front page, we read that the tract consists of three books. The first one is entitled:

modo di far l’impresa dal qualsiuoglia oggetto …, translated as “how to create insignias out of any object”. The second one is titled

Tutti ieroglifici, symboli, e cose mistiche in lettere sacre, o profane si scuoprono, translated loosely as “all hieroglyphs, symbols and mystical things in scripture and worldly books”. The third book is titled

nel figurar degli emblemi di molte cose naturali per l’imprese si tratta, or, in general translation, “for understanding the emblems of various natural things in the labels”.

Delle Imprese is a heraldic ordinary. This means that the work deals with the postulates of the Italian heraldry of its time. It depicts various heraldic charges through blazons and emblazons on many and various coats of arms, followed by a theoretical discussion of the insignias. This is particularly important because the data presented in the ordinaries are often based on other armorials or another source (

Clemmensen 2017, pp. 3–6). The breadth of the processed material makes the work

Delle Imprese important for European heraldry as well. However, the reason why it is so important to us is its overlapping with Illyrian heraldry both in terms of content and time. This is especially true of the coat of arms of Macedonia, but also of others.

Capaccio begins the second book of his work by elaborating on the lion’s figure as a coat of arms. After a thorough introduction to the lion as a symbol through a historical perspective in the third chapter of the book, entitled

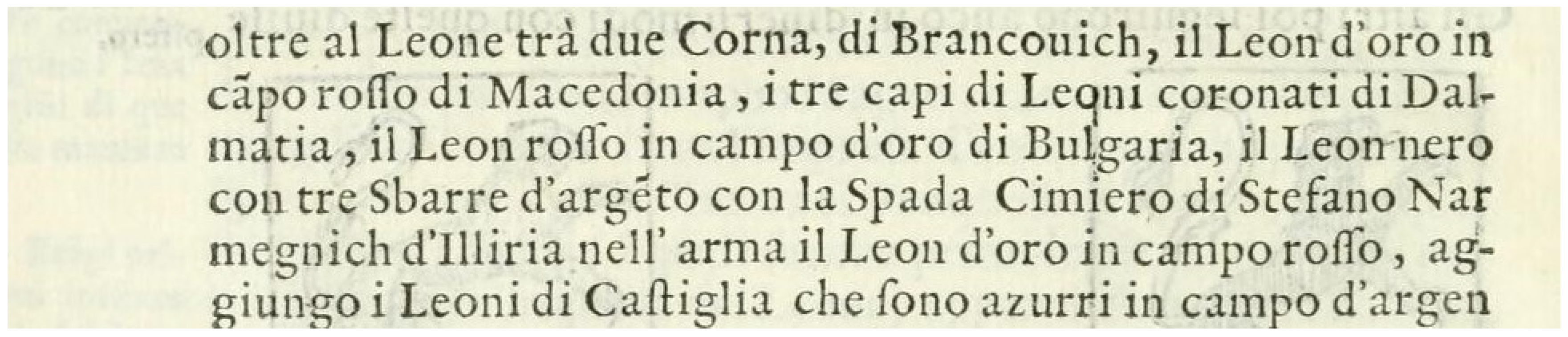

Come dal Leone cauar si ponno l’imprese, freely translated as “how to make lion insignias”, Capaccio turns to specific heraldic lion blazons. Thus, among others, we find the blazons of England, Denmark, and Aragon (

Capaccio 1592, II 10), followed by those of Brankovich, Macedonia, Dalmatia, Bulgaria, and Nemanjich. What sets this work apart and what makes it especially interesting to us is that all of these coats of arms are given in the context of real political actors from the time it was created. Four of the five blazons mentioned, namely those of Macedonia, Brankovich, Dalmatia, and Bulgaria, also find their place in the Korenich-Neorich coat of arms. The blazon of Macedonia reads:

il Leon d’oro in campo rosso di Macedonia (

Capaccio 1592, II 11), i.e., “Macedonia’s golden lion on a red field” (

Figure 8). This is by far the only and oldest Western European source with such a blazon for the coat of arms of Macedonia. It is also important to emphasize that most of the other currently known Western European coats of arms of Macedonia are in German and English. Brankovich’s blazon reads:

Leone tra due Corna, or translated, “a lion between two horns”. It must be noted that, despite the absence of colors in the description of Brankovich’s coat of arms, this blazon is archaeologically attested and has been repeatedly proven on seals and coins (

Aцoвић 2008, p. 168). The Dalmatia blazon reads:

I tre capi de Leoni coronati, i.e., three crowned lion heads. The colors are again missing here, but this blazon is identical to the blazon given in Virgil Solis’s

Wappenbüchlein.

The blazon of Bulgaria reads:

il Leon rosso in campo d’oro di Bulgaria, or, translated, “Bulgaria’s red lion on a golden field” (

Figure 8). Just as in the case of Macedonia, this is by far the oldest Western European source with such a blazon for Bulgaria. In practice, this means that between the

Wappenbüchlein and the

Delle imprese, seven of the ten coats of arms of the Illyrian lands come from these two works. Accordingly, this includes the coat of arms of Brankovich. The coats of arms of Raska and Illyria are found in

Rodoslovlje gospode Srpske i Bosanske. Thus, the only coat of arms that remains unwitnessed in another heraldic source is the coat of arms of Serbia. Nevertheless, the motif of this coat of arms has an artefact confirmation. The earliest one is from 1397, in the Decani Monastery (

Aцoвић 2008, pp 103–5). Regarding the above, it follows that whether the thesis of the origin of the Korenich-Neorich armorial as a copy or an original is true, what we know for certain is that in the same period in Naples we have Don Pedro Ohmuchevich, Capaccio, and Mateo Jerinic. All the more so because we know that Ohmuchevich and Capaccio had been in correspondence since 1582 (

Ceлoвcки 2016). Specifically, as Selovski notes in the work

Life of Torquato Tasso (La vita di Torquato Tasso) (

Serassi 1785, p. 545), there is information regarding a letter from Capaccio to Ohmuchevich. The quote in the work reveals little about the content of the otherwise long letter, yet one becomes quite certain that the two men knew each other. The exact contents of the letter certainly conceal important data about the relationship between the two. Researching and finding this letter, as well as the response of Ohmuchevich or some other letters, should therefore be a new goal in exploring the development of Illyrian heraldry.

If one accepts the theory of A. Solovyev that there is a lost

Ohmuchevich’s armorial, which was finally prepared around 1590, then we should check the possibility of Capaccio using that armorial or other of Ohmuchevich’s documents as sources for his work. Given the year of the correspondence indicated between the two, this, of course, is possible. However, it is not then clear why Capaccio mentions a blazon for the crest of Stefan Nemanjich as follows:

il Leon nero con tre sbarre d’argento con la spada cimiero di Stefano d’Ilyria, or “a black lion with three silver belts with sword, the crest of Stefan of Illyria” (

Capaccio 1592, II 11) (

Figure 8). All other examples that Capaccio mentions are coats of arms. On the other hand, he does not mention Kotromanich’s coat of arms, which also displays a lion. Of course, the use of the term

cimiero is symptomatic; it means crest in Italian. According to Matkovski, in Hungarian this word means coat of arms (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 37). Goodall says the Hungarian influence on Illyrian heraldry is also reflected in the fact that the word

cimer, which in French means crest, and, in Hungarian, coat of arms, is used in the Illyrian armorial. Finally, there is also the question of why Capaccio decided to change the color of the lion from the crest if he changed it at all. Specifically, from all the colored armorials that we have available, none have Capaccio’s colors in the blazon for the crest. It must be mentioned that Nemanjich’s coat of arms has a very stable and permanent blazon both in the Illyrian armorial and in the

Stomatographies, read as gules, a two-headed eagle argent.

Here, it should be borne in mind that at the time when

Delle Imprese was created it was common to print works a decade after they were written (

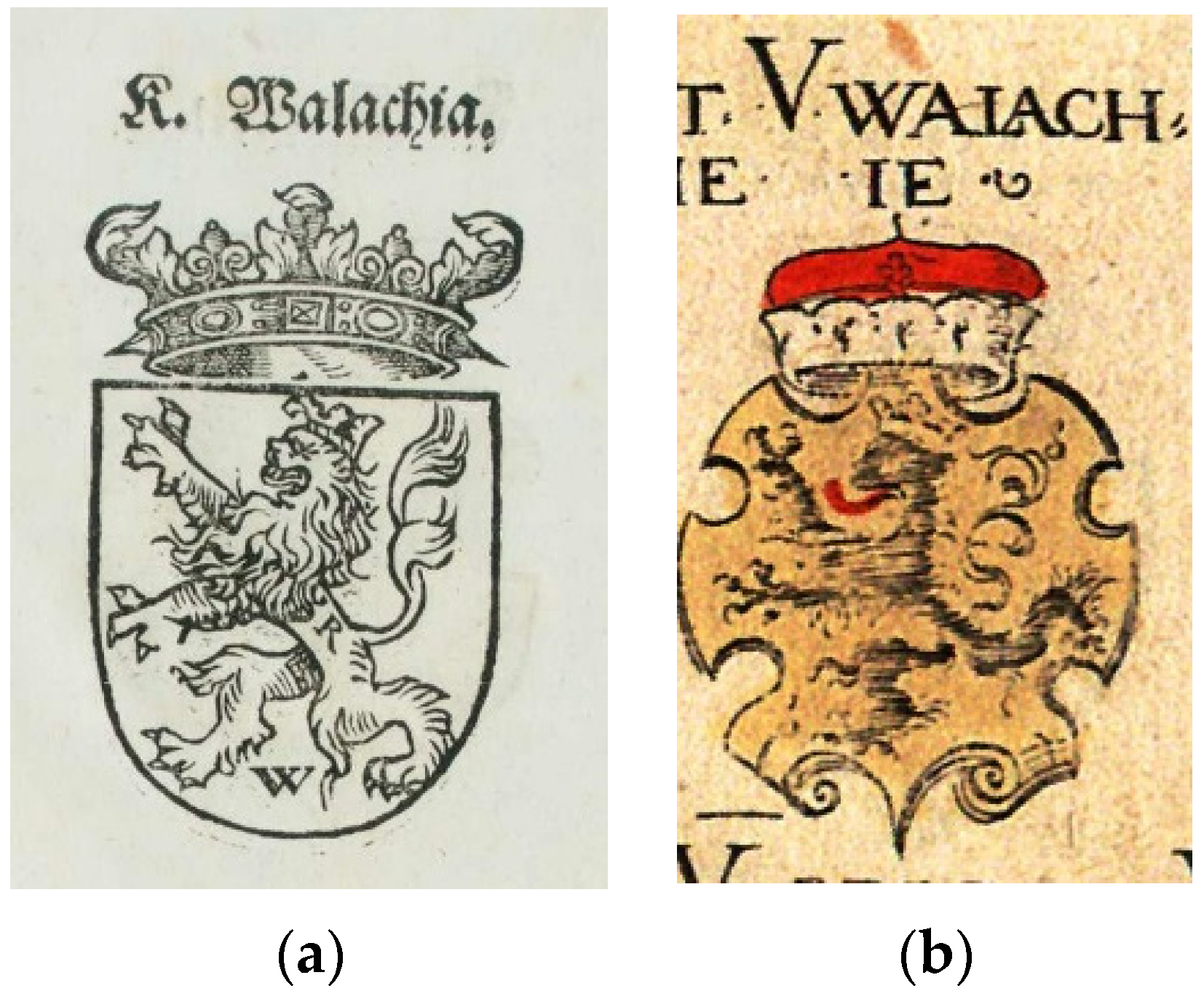

Nacevski 2019). We must also mention the need for Ohmuchevich to create a document that would be grounded on a verifiable base, which means that he could have been familiar with Capaccio’s handwriting before its official publication. If, however, Ohmuchevich’s armorial still existed, then it can be said with great certainty that Capaccio and/or other Neapolitan intellectuals took part in its creation, especially since we know for sure that Ohmuchevich and Capaccio knew each other. This is evidenced in Capaccio’s work itself—at the beginning he informs us about the struggle of Petar Ivelya Ohmuchevich to prove his origin from the famous dynasty. Specifically, in one paragraph, Capaccio points out that the Nemanjich used the name Stephen as “

cognome della Regia Maestra” in a similar fashion to the Caesars in Rome, Herodotus among the Jews, and Ptolemy in Egypt (

Capaccio 1592, p. 10) (

Figure 9). There is a similar sentence in the

Rodoslovlje and in Mavro Orbini, who states that he took it from the comments of Giovanni Gobelin on the memoirs of Pope Pius II (

Pyдић 2006, p. 45;

Orbini 1601, p. 369). These memoirs were published in Rome in 1584, and Solovyev would use them to date the origin of the

Rodoslovlje. Pope Pius II also wrote on this subject in his

History of Europe from 1490 (

Pyдић 2006, p. 279).

From the data above, it can be more readily accepted that Ohmuchevich used Capaccio’s work, rather than vice versa. This gives us the opportunity to elaborate on the possible period in which the supposed Ohmuchevich’s lost armorial would have been created. If it had existed, it would have been made between 1592, i.e., after the publication of Delle Imprese and 1594, respectively, before the final confirmation of the recognition of the nobility of Don Pedro Ohmuchevich was received. In any case, the question that inevitably arises here is what other older work was used by Capaccio in the creation of Delle Imprese? The answer to this question will most certainly take us even further in heraldic terms and may finally make the connection between the contributed coat of arms of Alexander the Great and the Macedonian coat of arms, something that is readily apparent from the available heraldic material but has not yet been confirmed.

Delle imprese could answer the question of the source of the Macedonian coat of arms in Illyrian heraldry as well as of the source of the Bulgarian coat of arms. Specifically, this is the first and so far, the only place where the coats of arms of the two countries are the same as in Illyrian heraldry and are so close to each other in a European armorial. The order of the blazons in the

Delle Imprese is as follows: Brankovich, Macedonia, Dalmatia, Bulgaria, Nemanjich; it is clear enough that Capaccio had no pretensions to any connection between these arms, otherwise we would expect this to be reported through some comment. This is important in the context of the later inversion of the two blazons of the Macedonian and Bulgarian arms. In the light of this new insight, it is also worth commenting on Acovic’s baseless interpretation of the dubious authenticity of the Macedonian coat of arms. Acovic quotes Ivo Banac’s unpublished paper as claiming that the Macedonian coat of arms is an inversion of the Bulgarian in the context of a territory with a historical but not a state pedigree (

Aцoвић 2008, p. 172), even though he himself gives three blazons of the coats of arms of the King of Macedonia (

Aцoвић 2008, pp. 268–71) and acknowledges that there is a possibility that the coat of arms of Macedonia may have originated from the contributed coat of arms of Alexander the Great (

Figure 10).

However, he is closer to thinking that the inversion of the two arms is due to an alleged connection of Samuel’s Kingdom in the end of the X and beginning of the XI century or some other unexplained reason. Here, he also makes a chronological mistake. Thus, according to Acovic himself, the lion as a Bulgarian state symbol will be strengthened by the reign of Kaloyan in the end of the XII and beginning of the XIII century (

Aцoвић 2008, p. 166), so it remains unclear what this has to do with Samuel, who lived some two hundred years earlier and in pre-heraldic times. Most probably unconsciously, Acovic put Samuel’s reign in the second Bulgarian empire. However, bearing in mind that at the time of the

Delle imprese and the Korenich-Neorich coat of arms, Alexander the Great, and with him Macedonia, are far more frequent names in European literature and cartography than Bulgaria and, probably, other Balkan countries, such claims are groundless. Moreover, even modern Bulgarian heraldic authors who like to refer to Samuel as an integral part of Bulgarian state traditions do not associate the lion with Samuel (

Boйникoв 2017, p. 43). Acovic’s claim could only be weighted if Bulgaria meant a Byzantine theme covering parts of Macedonia and Serbia. However, this, of course, cannot be accepted again because of Macedonia’s well-known borders, as well as the cities within it (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 54). However, the inversion of the two coats of arms is a fact, and with the reemergence of

Delle Imprese as a heraldic source it seems that the question of the reasons for it by Vitezovich is raised again. This seems to complicate the case to infinity, but we will try to shed some light on it further on in the text.

4. Munster’s Cosmography, Martin Schrot’s Armorial and Parentalia Divo Ferdinando Caesari Augusto

When it comes to the sources for the Illyrian armorial, another important one was Sebastian Munster’s

Cosmography. This work, which describes the world, was first printed in 1544 in Basel. It would subsequently be republished many times and translated into Latin, French, and Italian. Solovjev considers

Cosmography as a source for the creation of the

Rodoslovlje, which in turn influenced the armorial. According to Solovjev, the compiler of the Illyrian armorial used the 1575 Italian edition of the

Cosmography, which was based on an extended French edition (

Solovjev 1954, p. 101). In Munster’s

Cosmography, Macedonia is found quite often. An overview of ancient Macedonian history is given, especially of the reigns of Philip and Alexander, but there is no data on the later history of Macedonia. Despite this widespread representation, there is no display or description of the coat of arms of Macedonia or Alexander. Bulgaria is also widely represented, but it too has no representation of a coat of arms.

Alexander Palavestra, looking at the sources of Illyrian heraldry, deals with the French armorial

Charolais. As the title of the armorial states, it deals with “the coats of arms of the greats of the world, assembled by pais hands by the commendemant of Monsignor the Duke in the year 1425, duplicated on the original, 1658, in the noble city of Brussels”. This armorial contains a huge number of coats of arms from Illyrian heraldry, and even those we find only there. This convergence with Illyrian heraldry rightly led Palavestra to the conclusion that the 17th-century transcriber of the

Charolais enriched this heraldic collection with coats of arms that he had redrawn from an Illyrian armorial (

Пaлaвecтpa 2010, p. 106). The importance of this armorial, according to Palavestra, is that it clearly shows that just as coats of arms from Illyrian heraldry could be transferred to Western Europe, so it can be considered that some of the medieval European armorials, unknown to us, were available to the compiler of the Illyrian armorial (

Пaлaвecтpa 2000, pp. 267–68). This opinion is shared by Vujadin Ivanisevic, who points to numerous similarities between the heraldic insignias of medieval Serbian nobility and the coats of arms of the Zurich roll of 1340 (

Ивaнишeвић 2004, pp. 213–34). The previous assertions suggest that the coats of arms of Macedonia and Bulgaria from the Korenich-Neorich armorial could have originated from some older European manuscripts that were available to the armorial’s author. It should be noted that Ivan Voynikov, a researcher from Bulgaria quoting Goodall, points to Martin Schrot’s armorial, published in Munich in 1580, as the main source for the creation of the Illyrian armorial (

Boйникoв 2011;

Goodall 1995, p. 266). This work, of course, could have been available to the creator of the Illyrian armorial.

From all the notions elaborated until this point in regard to the possible origins of the coats of arms of Macedonia and Bulgaria, two points of view can be formed: the first is that the coats of arms have a common source for the blazon, and the second is that coats of arms have two separate sources of blazons. The thesis of a common older European source is widely explained by Voynikov in an article entitled

Macedonia through the view of heraldry (

Boйникoв 2011). In it, Voynikov writes that the possible inversion of the colors of the arms is laid as a feature in the creation of both coats of arms, i.e., it is “initial” in the sense that it is meant to be a connecting string of the two coats of arms. So, Voynikov is looking for a source for both of them in the coat of arms of Wallachia (

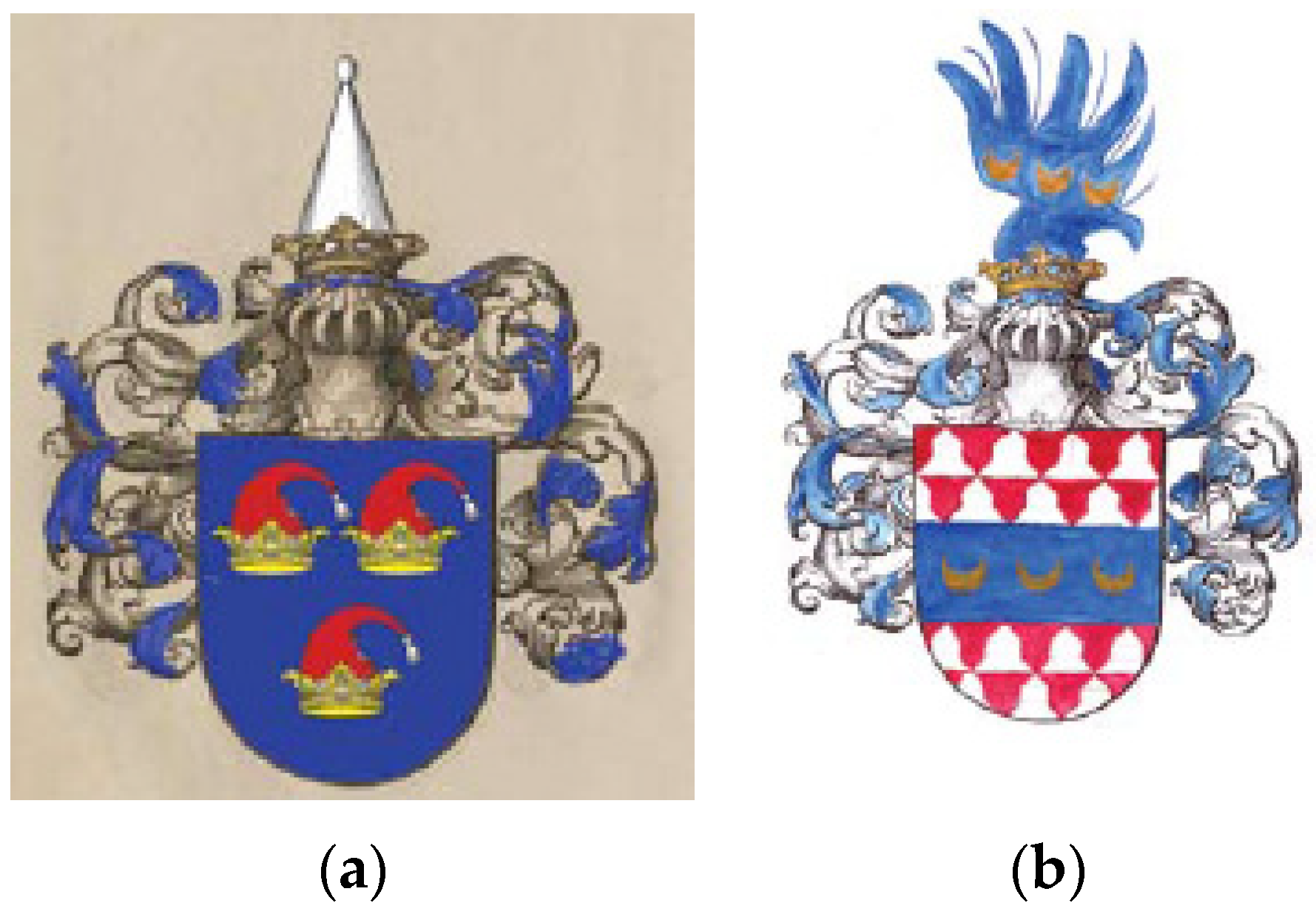

Boйникoв 2011) in the work of Martin Schrot. This is likely the only reason why Voynikov considers this armorial as a source for the Illyrian armorial. However, there is a problem. Specifically, Voynikov himself notes that in addition to the coats of arms of seven other Illyrian countries, the coat of arms of Bulgaria (

Boйникoв 2011) is also found in the Schrot armorial, but in this source, it is identical with the coat of arms of Bosnia from the Illyrian armorial (

Boйникoв 2011) (

Figure 11). Quite expectedly, the creator of the Illyrian armorial would have needed to change the Bulgarian coat of arms. Additionally, in Schrot’s armorial the Bosnian coat of arms is not the same as the one in the Illyrian armorial, but is the same as that of Primorye. Schrot’s armorial also features the coat of arms of Serbia in the form of a shot boar’s head. This blazon is well known and is found in the

Stematographias of both Vitezovich and Zhefaroivch as the coat of arms of Tribalia (

Vitezovic-Ritter 1701, p. 52;

Жeφapoвић and Mecмep [1741] 1972, p. 78), but it seems that this blazon too did not find a place in the Illyrian armorial. It must be said that Solis also has the coat of arms of the Herzog of Wallachia (

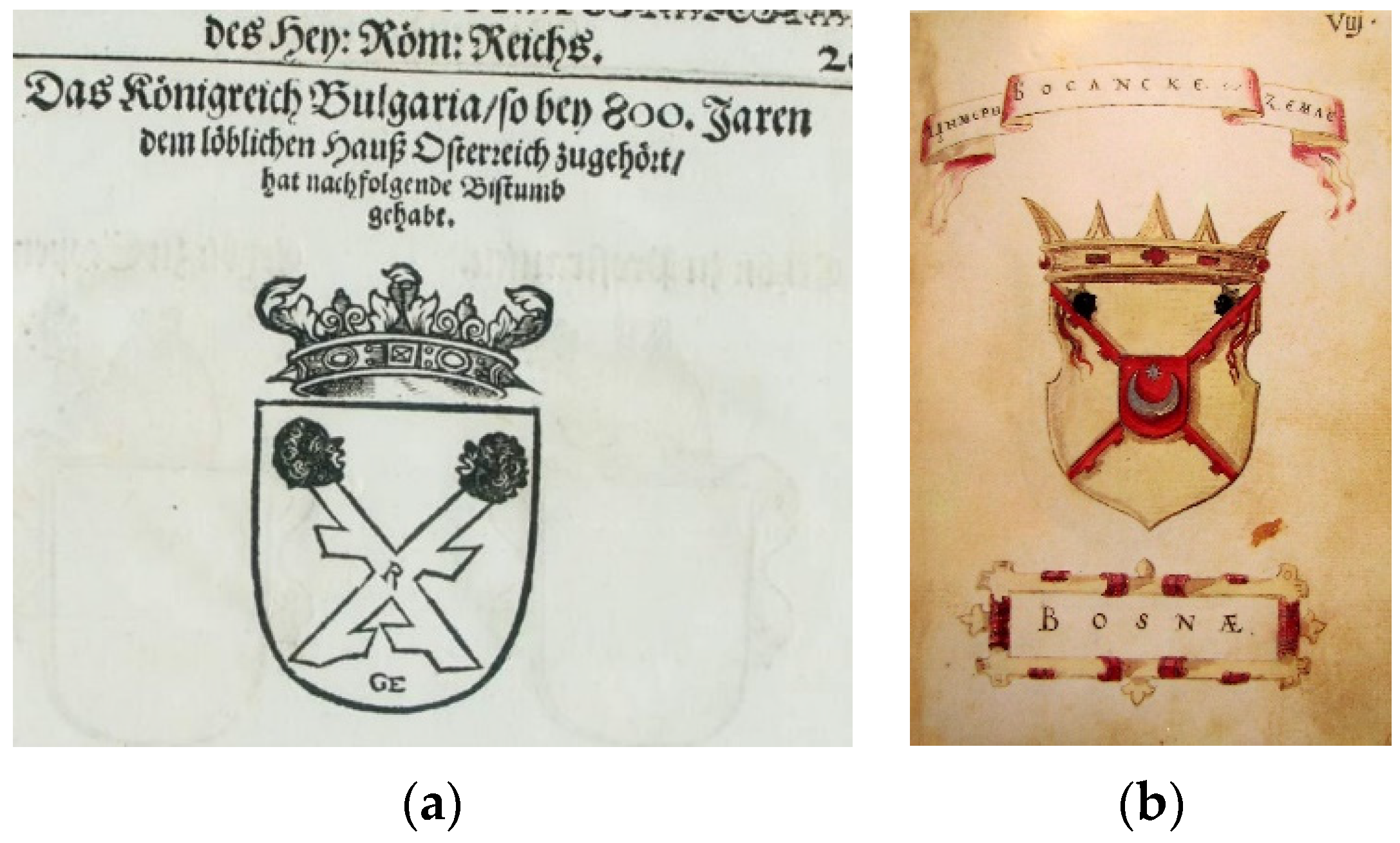

Solis 1555, fol.28). Hence, the question arises: why would the creator of the Illyrian armorial make such large interventions in his basic source?

The coat of arms of Wallachia in Schrot’s armorial has the following blazon: Argent, a Lion Gules crowned Or (

Schrot 1580, p. 19) (

Figure 12). The blazon of the Herzog of Wallachia in Solis’s work is: Or a Lion Sable armed of the first, crowned Gules (

Solis 1555, fol.28) (

Figure 12). Here, it should again be stated that both of these blazons are probably derived from Richental’s coat of arms for the

“herczog dispott in der meren walachy” with the following blazon: Argent, a Lion Sable, crowned of the second. The second blazon is indeed relatively close to the Bulgarian coat of arms of the Illyrian armorial, given the tincture of the shield above all else. Additionally, the similarity between the coats of arms of these two countries is evidenced by the description given in the

Stematographias of both Vitezovic and Zhefarovic (

Vitezovic-Ritter 1701, p. 63;

Жeφapoвић and Mecмep [1741] 1972, p. 90), as will be shown further on in this paper. It must be noted that this is not the only case. Again, Voynikov tells us about such examples in his work

History of the Bulgarian State Symbols (

Boйникoв 2017, p. 55). This relation between Bulgaria and Wallachia is primarily in the context of the Second Bulgarian Empire. However, in the same book, Voynikov revises his initial position regarding the origin of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms and presents a new one. The author now offers the coat of arms of Bulgaria from the work

Parentalia Divo Ferdinando Caesari Augusto … from 1566 as a source for the coats of arms of both of the countries (

Boйникoв 2017, p. 174). The blazon of the coat of arms in this work is: Argent, a Lion Azure crowned of the second. This is certainly possible, at least as far as the Bulgarian coat of arms is concerned, especially because it refers exactly to the coat of arms of Bulgaria. On the other hand, the Wallachian blazon of Solis needs smaller adjustments to reach the Illyrian variant of the Bulgarian coat of arms. In any case, we can accept with a certain amount of reservation that these may be the probable sources for the Bulgarian coat of arms. Then again, the same could be said about any other coat of arms featuring a lion.

However, what about the Macedonian one? The Macedonian coat of arms in the Illyrian armorial occupies the honorable first heraldic place in the coats of arms of Nemanich’s dominion. It should thus be expected that this coat of arms would be the source of some other arms, not the other way around. There is no reasonable explanation for putting in the first place of honor a coat of arms obtained as a secondary product from an inversion of a coat of arms that has nothing to do with the narrative of the work and has nothing to do with the family history of the client or creator of the armorial. The second point of view is based on the fact that at the time of the emergence of the Illyrian armorial, Macedonia was known and often found in European literature (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 54) and cartography, in a sense certainly more often than Bulgaria, and probably the other Balkan countries. Thus, when it comes to Macedonia in the Illyrian armorial, several things should be pointed out.

Firstly, of course, Macedonia, that is, the territory of the legendary ancestor Hrelja Ohmuchevich (

Ćosić 2015, p. 129), represents the oldest historical layer, the deepest genealogical penetration through which the creator of the armorial tries to give legitimacy to its client. This is important for the Ohmuchevich-Grgurich family as much as for the Korenich-Neorich-Jerenich family. Secondly, in the Illyrian armorial, Macedonia is present due to events and personalities from its medieval history. Evidence of this is, of course, the presence of the dynastic coats of arms of the Mrnjavchevich, Brankovich, and Kastriotich families. This is of particular importance because by placing Macedonia in an Illyrian or Slavic context, the creator shows us that he has better familiarity with the reality of the southern Balkans than a good part of his Western European contemporaries. In that sense, the view that the presence of Macedonia in the Illyrian armorial has a basic humanistic reflection is not completely sustained (

Pyдић 2006, pp. 47, 51). In most of the European works of that time, Macedonia is really represented only by its ancient history, and hardly any author points out anything about the contemporary country. On the other hand, however, in European works, the geographical positioning of Macedonia is very precisely determined. For example, the maps in Munster’s

Cosmography show that Macedonia’s borders are as follows: the Aegean Sea to the south, the Pindos-Scardus mountain chain to the west, and Scardus to the north. The micronyms Axius (Vardar), Aliakmon (Bistrica), Thessaloniki, and Athos are also visible (

Münster 1544, p. 91) (

Figure 13).

Paying attention to the fabricated forgery of Pedro Ohmuchevich, in which Macedonia is mentioned, Voynikov points out that in the 14th century (the time when these fictitious documents allegedly originated) the macronym Macedonia did not refer to the region around Castoria (

Boйникoв 2011). It is indisputable that the charters were pure fiction—an illusion, so to say. However, the notion that Castoria was not in Macedonia in the 14th century is incorrect. It is enough to point out the Byzantine chronicler Nicephorus Gregora and his writing to see that despite the creation of the Byzantine theme “Macedonia in Thrace”, the name of the territory of historical Macedonia was maintained. Thus, Gregora describes Castoria, Prespa, Prilep, Veles, and Thessaloniki as cities/fortresses in Macedonia (

Aтaнacoвcки 2000, p. 65;

Gregora 1829, p. 48). All in all, there are sufficient grounds to accept that the Macedonian coat of arms in the Illyrian armorial has its own older European source (

Nacevski 2016, pp. 12–19) recalling Alexander the Great (

Ćosić 2015, p. 129).

Additionally, a source for the Macedonian coat of arms can be found in the coat of arms of the Macedonio family from Naples. According to family tradition, this family originated in the dynasty of the Argeads or from Philip II through his daughter Thessalonica, but also in the Macedonian dynasty in Byzantium (

Boйникoв 2011). The Macedonio family was first mentioned in sources in 1268. In the historical development of the family, two branches with two coats of arms formed. The older branch of the marquise of Oliveto carries a coat of arms with a blazon: Vair, Azure and Argent, a Lion Or (

Petrasancta 1638, p. 312). The branch of the dukes of Campora carries a coat of arms with a blazon: Vair, Azure, and Argent, on a Bend Or a Lion passant Gules (

Figure 14) The vair in the blazons of these coats of arms is somewhat reminiscent of the coat of arms of Macedonia from the Miltenberg armorial, where the blazon of the shield is: Vair, Gules and Argent, on fess Azure three crescents Or (

Joнoвcки 2015, p. 152). It is obvious that the blazon of the older branch is close to the coat of arms of Macedonia from the Illyrian armorial. This is of great importance primarily for the origin of the Macedonian coat of arms because part of the family coats of arms in the Illyrian armorial are directly taken from, and in another part are based on, the example of coats of arms from contemporary Italian heraldry (

Pyдић 2006, p. 55). The coats of arms of Balshich, Voinovich, Deskoevich, and probably others testify to this.

Since both views on the origins of the Macedonian and Bulgarian land coats of arms are not conclusive, there is a possibility of a third: two different sources with relatively similar blazons resulting in simplification and inverse coloring of both of the coats of arms. This would mean that it is quite possible that the Macedonian coat of arms was taken over by Capaccio, who took it from another older source. First of all, the coats of arms with a lion attributed to Alexander the Great should be taken into consideration. In many of the armorials, we find that the coat of arms of a country is presented as the coat of arms of the ruler of that country. Examples of this with Alexander the Great are found in

Silbereisen: Chronicon Helvetiae from 1576. In it, a coat of arms is described as of the king and kingdom in the time of Alexander the Great (

Figure 15). This in turn comes from Richental’s blazon for Macedonia.

The known armorials where Alexander’s arms have lions as charge are almost always from romance-speaking regions, especially France. So far, at least five examples of these armorials are known in which Alexander’s and Macedonia’s blazon from the Illyrian armorial are almost identical. One of them is Spanish, the armorial of Garcia Alonso de Torres Rey de Armas de Aragon, from 1496, whose blazon reads: Gules, a Lion Or. We single this armorial out because of Ohmichevich’s relationship with Naples, which was under Spanish rule at the time. There is a possibility that the source of the Macedonian coat of arms was the armorial of Jerome de Bara (

Jonovski 2009, pp. 3–14) as the only printed coat of arms where there is a coat of arms of Alexander the Great with a simple lion’s blazon (

de Bara 1572, p. 131). Voynikov rejects this possibility, primarily due to the fact that this is the only printed lion’s coat of arms and that there the blazon is identical to the Bulgarian from the Illyrian coat of arms (

Boйникoв 2017, p. 173). However, this is not the only printed source where Alexander has a lion on the arms. For example, on the cover of a printed edition of

Alexander Romance from 1541 by Walter de Castellione, Alexander is depicted riding a horse. In his left hand he holds a shield with a lion, and in his right, he holds a flag with a lion on a spear (

de Castellione 1541, p. 1). Unfortunately, the colors are not indicated. It is quite possible to assume that there are other such examples that remain beyond our reach for now. Of course, the aforementioned coat of arms of the Macedonio family from Naples is also a very probable source, bearing in mind that Cappacio, Ochmuchevich, and Jerenich spent a great deal of their lives in Naples. As we have said, the Bulgarian coat of arms could have been taken over by one of the armorials mentioned by Solis or

Parentalia Divo Ferdinando Caesari Augusto. Basically, neither the Bulgarian nor the Macedonian coat of arms from the Illyrian armorial has been encountered together with those blazons outside Illyrian heraldry, except in

Delle Imprese by Capaccio, so as it is possible to change the colors of the previous sources offered for the Bulgarian coat of arms, as Voynikov believes, so it is possible the same thing happened with the Macedonian one.

5. The Inversion of the Macedonian Coat of Arms

Heraldic inversion is a process of differentiation of arms in which the color of the shield and the color of the heraldic figure are switched in order to obtain another, heraldically different coat of arms, which nonetheless indicates a connection between the two. Early examples of heraldic inversion are found as a mean of cadency, that is, the process of differentiating the coats of arms for younger sons or the collateral branches of a family. At the heart of the process of heraldic inversion is the idea of an initially accepted blazon that is inverted at some later stage. That is, in order to be able to talk about heraldic inversion, it is necessary to know the blazon of a given coat of arms for certain. If the initial blazon is not known for sure, and yet there are two coats of arms that act inversely to one other, then another contextual indicator that would link the two in an inversion process should be sought to determine such a possible relationship. This indicator can be most easily seen through the aforementioned example of inversion as a degree of cadency, that is, as a degree of inheritance. Examples of this practice are found nearly everywhere in Europe, and especially in Germany, the Netherlands, and Britain (

Gayre 1961, pp. 26–32). A possible example of this practice associated with Macedonia is found in the work

Roman de toute chevalerie. This work was created by Thomas de Kent around 1304–1308. It is an adaptation of the novel about Alexander based on the work

Res gestae Alexandri Macedonis by Julius Valerius Alexander Polemius, which in turn is a translation of the author Pseudocalistenus from Old Greek. This work contains a miniature in which the funeral of Philip II of Macedon is depicted, which clearly shows a heraldic composition with a blazon: Or, a lion Gules (

de Kent 1304–1308, fol. 6v) (

Figure 16). Another miniature in the same work shows the coat of arms of Alexander the Great with a blazon: Gules, a lion Or (

de Kent 1304–1308, fol. 30r) (

Figure 17).

From the very beginning of research on the Macedonian coat of arms in the Illyrian heraldry, a similarity with the Bulgarian coat of arms has been observed, and attempts have been made to explain their possible inversion, which undoubtedly enters as a significant point in the study of their development. Important authors such as Aleksandar Matkovski, Dragomir Acovic, Jovan Jonovski, and Ivan Voynikov, who paid attention to the Macedonian coat of arms, dedicate a good part of their work to this issue. Thus, the possible inversion of the Macedonian coat of arms has become an inseparable part of its narrative, and we are obliged to study it as a category and as a process.

The possible inversion of the Macedonian and Bulgarian arms is a trait of Illyrian heraldry, and it cannot be found in works outside this group. In fact, we do not find the two coats of arms with these blazons together in any other work except for the aforementioned

Delle Imprese by Capaccio. The coats of arms of both countries are also found in an armorial entitled

Joloim von Windhag’s Koloriertes Wappenbuch from the 16th century (

von Windhag 1500–1600, p. 2), but the blazons are quite different for both countries. Here, Macedonia has the blazon: Vert, an Ibex Rampant to sinister, Argent; and Bulgaria has a blazon: Argent, on a Bend, Vert, a Hound Courant, Sable (

Figure 18). As previously elaborated, the question of the source of the two arms is crucial in determining whether there is indeed a case of inversion of the two. In essence, this question cannot be answered definitively without a detailed study of the condition of these two coats of arms in Illyrian heraldry and beyond, but it is also necessary to seek a contextual indicator to determine whether there is any inversion of the two coats of arms or if the change in the colors is the result of something else. Thus, in works from Illyrian heraldry, the inversion can be divided into two groups: initial inversion as a characteristic of the arms’ creation and causal inversion as a result of an error or correction in the process of copying or creating other heraldic works (

Nacevski 2020).

The “initial” inversion is a two-phase process that would have occurred in the very creation or upon the entry of the coats of arms into Illyrian heraldry and is potentially developed from gules/or to or/gules and vice versa. This means that in the first phase, one coat of arms was taken, probably from some of the aforementioned older sources, and thus entered the Illyrian armorial, becoming a source for the other coats of arms. In this way, the second coat of arms became an inversion of the first. In the second phase, due to uncertain reasons or needs, the two coats of arms changed their colors again, with the source becoming inverted and the inverse coat of arms becoming the source.

On the other hand, “causal inversion” is a single-phase process that potentially took place in the transition from the Illyrian armorial to Orbini’s Il Regno de gli Slavi and from it to Vitezovich and then to Zhefarovich. In this scenario, both blazons could have entered Illyrian heraldry independently, probably from some older European source. Their subsequent inversion would again be the result of some uncertain cause or need. What unites the two possible types of inversion is the question of a contextual indicator. This is closely related to the sources used in the creation of the works that make up Illyrian heraldry, which in turn is related to the process of its origin and dating.

The first to propose the possible inversion of these two coats of arms was Aleksandar Matkovski in his work

The Coats of Arms of Macedonia. As we mentioned in the beginning of this paper, the inability to research the novels about Alexander the Great as well as a good part of the European armorials, and probably the inadequacy of the subject at the time in which he worked, led Matkovski to two narrow conclusions about the Macedonian coat of arms. The first is that, unlike the other South Slavic coats of arms, it first appears on a domestic South Slavic terrain (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 43). It is interesting that during his research, Matkovski used Western European armorials with the coat of arms of Macedonia on them. Such is the case, for example, with Urlich Richental’s armorial from the Council of Constance (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 42). In it, as a 283rd coat of arms, we find the coat of arms of Alexander the Great’s country with a blazon: Argent, three bells Gules with clasps Or (

Clemmensen 2017, p. 95). This is the same blazon as the one from the aforementioned

Chronicon Helvetiae from 1576. It will remain unknown whether Matkovski did not notice this coat of arms or if it simply did not fit into his expected results.

The second conclusion is that the Macedonian coat of arms has always been: Gules, a lion Or (

Maткoвcки 1990, pp. 167–74). With an analysis of the coats of arms included in

The Coats of Arms of Macedonia, we will clearly show that this is not the case either. As it is, Matkovski does not recognize inversion as an inherent trait in both coats of arms. On the contrary, for him, the two coats of arms underwent different development: the Macedonian—purely Illyrian—and the Bulgarian—older European. Matkovski always attributes the reasons for the consequent inversion to the negligence of the compilers, especially Vitezovich (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 85). Basically, Matkovski records a change in the heraldic places of the coats of arms, and the color change is only a consequence of that condition.

The first source that changed the place of the Macedonian coat of arms, and thus its blazon, was

Il Regno degli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni by Mavro Orbini. Although this work itself is not part of Illyrian heraldry, in terms of it being a history book and not an armorial per se, it contains a number of coats of arms taken from Illyrian heraldry (

Pyдић 2006, p. 61). The work was printed in black and white in 1601. It is generally accepted that Orbini took eleven coats of arms from the Illyrian armorial (

Pyдић 2006, p. 61). Orbini also gives us the coat of arms of Hum (

Orbini 1601, p. 399), which was unknown in Illyrian heraldry before that. There is no data on the colors of the coats of arms in

Il Regno degli Slavi. Here, the Macedonian coat of arms is found only in the dominion coat of arms of Nemanich. As we mentioned, Orbini changed the places of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms, which is indicated only in the index of the dominion coats of arms (

Figure 19). Thus, in Orbini, the Macedonian coat of arms is on the fourth place, and not on the first. This change of places necessarily means a change of colors because in all other dominion coats of arms of Nemanich, the first field is gules with a lion or and the fourth is or with a lion gules. Additionally, the Bulgarian lion is now crowned, and the Macedonian lion is not.

The basic question here concerns the reason for the change in the places of the two coats of arms. Mavro Orbini was a Catholic priest and Dalmatian historian (

Пaнтић 2006, pp. XI–CXV). He is considered one of the founders of Pan-Slavism and Illyrianism. He was dedicated to the affirmation of the Slavic peoples, especially the South Slavic ones. Orbini used numerous sources and largely followed the late Byzantine historical narrative, but often made compilation errors, describing two events completely differently (

Ћиpкoвић 2006, pp. 439–519). In his work, medieval Macedonian history is considered in several separate places. It is basically presented as part of Serbian and Bulgarian history and as part of the history of the Mrnjavchevich family. Macedonia does not get its own chapter despite the author’s unambiguity about the existence and “Slavic” origin of the ancient Macedonians. It is interesting that Orbini uses Nicephorus Gregora as a source in whose work we regularly find Macedonia and Macedonians (

Aтaнacoвcки 2000, p. 62). In any case, by writing a general historical work, Orbini lacked the basic reason of the creator/client relationship of the Illyrian armorial to link his origin with Hrelja Ohmuchevich, that is to say, with Macedonia. On the other hand, Bulgaria, as an affirmative medieval state, according to Orbini, could quite thoroughly occupy the first heraldic field in the dominion coat of arms. Orbini’s move may have been influenced by Nemanich’s kinship with the Shishman and Smilec families. Tsar Stefan Dusan is the eldest son of Stefan of Dechani and Teodora Smilec, daughter of Bulgarian King Smilec. In his father’s line, Stefan Dushan is the grandson of Ana of Bulgaria—daughter of the Bulgarian Tsar George I Terter and wife of Stefan Milutin. Stefan Dusan was married to one of the sisters of Tsar Ivan Alexander—Empress Elena of Bulgaria.

There is another possibility that would have encouraged the change of places. Namely, Orbini may have been acquainted with some of the coats of arms attributed to Alexander the Great, especially those where the lion gules is found, and that could have additionally contributed to the change. In any case, although Orbini does not announce the colors of the coats of arms, he establishes a reverse paradigm from the creator of the Illyrian armorial. As we have mentioned, this is not accidental, but is done with a deep thought that corresponds to the “political” purpose of the author.

The second work in which the possible inversion of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms is observed is the

Stematographia sive armorum Illyricorum delineatio, descriptio et restitutio by Pavle Ritter Vitezovich (

Figure 20). Vitezovich was a Croatian writer, historian, and linguist who was a member of the Illyrian and Pan-Slavic movement (

Kljagić 2013, pp. 141–43). Vitezovic published his

Stematographia in 1701. Due to the huge interest in the work, he would publish a second edition the next year. Unlike the Illyrian armorial, where both territorial and family coats of arms are found, the

Stematographia consists of territorial coats of arms only. Each arm is followed by a description in four verses. At the end of the

Stematographia, comments are placed on each coat of arms in the work. This is probably its greatest value. In these comments, contextual indicators are given for each coat of arms, which in turn gives us insight into the author’s understandings and goals.

What is especially important when studying Vitezovich’s

Stematographia is that he owned two Illyrian armorials: the Olovo armorial and Althan’s armorial. He studied them in his work, and in the Althan armorial he even made corrections the Latin text on the very coat of arms of Macedonia. Namely, above the coat of arms of Macedonia, he crossed out the incorrectly written name Dalmatia and wrote Macedonia (

Пaлaвecтpa 2010, p. 90) (

Figure 21).

Undoubtedly, Vitezovich was familiar with the older European sources where the coats of arms of Macedonia and Bulgaria were found, which is clearly seen in the comments on the coats of arms. In these, the Macedonian coat of arms is described as:

rubeo Leone aureum campus insignivit; quem nonnulli Graeciae stemma fuisse opinion; Quidam rubeum Epiri Molossum ante Alexandri M. tempori, post clavam Herculis inter Buphali Taurive cornua erectam addidit; Nemandae Reges rubeo usi sunt, pro Macedoniae Insignibus, qui eorum proprietatem in procerum suorum & parezciarum scutis diligenter observabant (

Vitezovic-Ritter 1701, p. 69), or, translated: “a red lion on a golden field, which some think as of Greece’s coat of arms; some Epirian dog before the time of Alexander the Great, after Heracles’ club between upright ox horns; the Nemanich emperors use red for the Macedonian insignia, which is carefully observed in their tribal and provincial shields.” The Bulgarian coat of arms is described as follows:

fulvo coronatoque Leone in campo rubeo armatur. In quodam manuscript reperi, Leonem rubrum super aureo campo: qui Macedoniae sencetur. Apostolici Reges nigrum faciunt intra Stellam & Lunam rubeas (quam alii Valachiae appingunt) in campo albo (

Vitezovic-Ritter 1701, p. 63), or, in translation: “a golden crowned lion a red field arms; some manuscripts show a red lion on a golden field; which is considered Macedonian. An Apostolic King, black between a Star and a red Moon (which others attribute to Wallachia) on a white field.” The texts show that the two coats of arms are connected by chance and omission. The mention of Wallachia, as already discussed, is in the context of the Second Bulgarian Empire and more precisely with the ruling house of Asenov (

Boйникoв 2017, p. 55). In the comments on Mizia, Bulgaria is also mentioned, which should be considered in the same regard.

The descriptions clearly show that Vitezovich accepted Orbini’s paradigm, and this is not surprising. Vitezovich was a supporter of the Illyrian idea, which is based on the medieval Balkan states, especially the one of the Nemanich family. Vitezovic was strongly influenced by the Illyrianism and Pan-Slavicism of Mavro Orbini and Vinko Priboevich. In that sense, the

Stematographia was a political tool for promoting the author’s ideas. That is why Vitezovich consistently adhered to them and accepted Orbini’s actions as correct, regardless of the fact that he was familiar with a slightly different situation for both coats of arms. However, what entitles us to conclude that Vitezovich consciously carried out the changes on both the coats of arms from the Illyrian armorial is the fact that he removed the shield of Illyria from the coat of arms of Bosnia because the idea of Bosnia as the heart of Illyria did not fit into his Croatian heraldic ideological conception (

Ćosić 2015, p. 128).

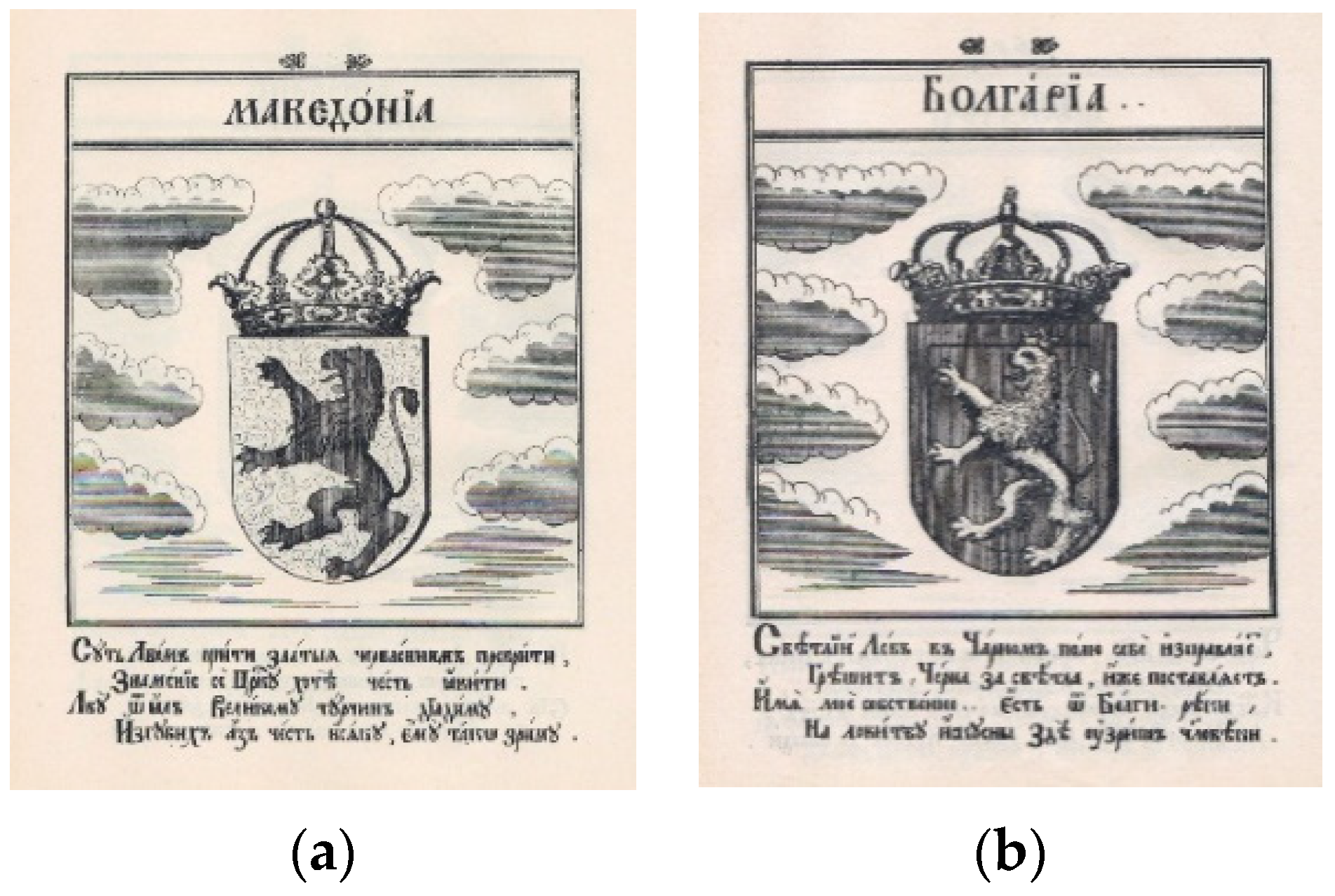

The third work in which a possible inversion of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms is observed is the

Stematographia of Hristofor Zhefarovich (

Figure 22). Zhefarovich (b. 1690–d. 1753) was a famous painter, iconographer, coppersmith, author, merchant, herald, and strong supporter of the “Illyrian Idea” from Ottoman Macedonia (

Gjorgjiev and Sarakinski 2019, p. 5). Hristofor Zhefarovich’s

Stematographia is a printed work from 1741. It is basically a translation of Vitezovich’s

Stematographia (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 123). Here, too, each coat of arms is followed by a description in four verses. The lyrics are partly different from those of Vitezovich. At the end of the

Stematographia, comments on each coat of arms in the work are placed, which are mainly translations of those by Vitezovich. The coats of arms of Macedonia and Bulgaria are inverted in relation to the Illyrian armorial in this

Stematographia as well. Matkovski considers this an omission inherited from Vitezovich (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 129). However, from the verses and descriptions that, as we have said, deviate a little from Vitezovich, it becomes clear that this is not an omission but a conscious act (

Jonovski 2009, p. 8). Zhefarovich’s comment on the description of the Bulgarian coat of arms is completely identical to Vitezovich’s. However, there is a difference in the translation of the comment on the Macedonian coat of arms. Namely, Zhefarovich’s verses that the Nemanjich dinasty in the “знaмeнїe мaкeдoнcкo чepвлeннaгω лвa oyпoтpeблѧxy” (“The Macedonian insignia used red lion”) (

Жeφapoвић and Mecмep [1741] 1972, p. 97) deviates from Vitezovich where it is stated that they use red in the insignia, which clearly refers to the coats of arms of the Illyrian armorials. Zhefarovich, like Vitezovich, was a supporter of the Illyrian idea. However, with the changes he made to the dedication of Patriarch Arsenie IV, as well as his inclusion in the book of Orthodox Rulers and Saints, Zhefarovich changed the character of Vitezovich’s work (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 125). In that sense, the

Stematographia became a political tool for promoting the ideas of Zhefarovich, as well as those of Patriarch Arsenie IV, and the citizens of Vojvodina (

Maткoвcки 1990, p. 125). Zhefarovich’s

Stematographia was a popular work widely read among the Balkan peoples. It would go on to play a major role in changing the meaning of the terminology used in the Illyrian armorial. Thus, the term “land” or territory that has a narrow feudal root in the Illyrian armorial through the popularity of

Stematographia and its influence on the selection and definition of national symbols in the 19th century would gain ethno-national significance (

Ćosić 2015, p. 128). A good part of the Balkan peoples would base their new state coats of arms on the coats of arms of this famous and accessible work. An example of this related to Macedonia can be found in two places: the altar of the Rila Monastery and the flag of the Razlog Uprising. Specifically, the appearance and colors of the lion from this flag are graphically similar to the

Stematographia of Zhefarovich. It should be mentioned that a lion redrawn from the

Stematographia was found among the legacy papers of Dimitrija Pop Georgiev Berovski (

Mиљкoвиќ 2003, p. 24).

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, several points can be made in regard to the Macedonian coat of arms and its emergence and development in Illyrian heraldry. Firstly, we can accept with great certainty that besides Virgil Solis’s Wappenbüchlein, the book Delle imprese by Julio Cesare Carpaccio significantly influenced the creation of the Korjenich-Neorich armorial, and thus the entire Illyrian heraldry. There is a solid basis for considering that the model of the Macedonian coat of arms from the Illyrian heraldry was taken from the Delle imprese. The same applies to the coat of arms of Bulgaria and Brankovich. The way the blazons of these coats of arms are distributed and described gives us the right to consider them to be of different heraldic development, and finding the works that Carpaccio used as sources will unequivocally prove this. In between the Wappenbüchlein and Delle imprese, we find the coats of arms of seven out of ten Illyrian countries. On the other hand, in medieval European heraldry, the coat of arms of Macedonia appears practically simultaneously with the coats of arms of other Balkan countries. In its beginnings, it too has a certain inhomogeneity inherent in the other coats of arms that goes to become permanent later on in Illyrian heraldry. In this context, the Illyrian heraldry, despite its fictitious foundations, contains a sufficient number of coats of arms that have been taken over from the older European Heraldic Corpus.

Furthermore, the thesis of the possible initial inversion of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms is difficult to prove, especially given that the coats of arms of the two countries are known and used in European heraldry. In this sense, there is a sufficient amount of indirect data that leads us to possible prototypes for both of the coats of arms. However, the causal inversion by Orbini, Vitezovich, and Zhefarovich is more acceptable because it does not affect the issue of the origin of the coats of arms, for which there are hints but still no solid evidence. Capaccio’s Delle Imprese from 1592 is the only European work to date with two blazons identical to the Illyrian ones, but, as has been pointed out, it cannot be argued whether or not the lost Ohmuchevich armorial existed solely on this. Thus, the inversion of the two coats of arms is always within the works of Illyrian heraldry and only in the context of the Illyrian armorial towards Orbini and the Stematographias. That is, in all the transcripts of the Illyrian armorials, the two coats of arms have the same blazon as the oldest armorial, the Korenich-Neorich. The change in the places of the two coats of arms, and thus on their blazons, which would be first done by Mavro Orbini, is later followed in both Stematographias. In European heraldry, the coats of arms of both countries have a long and independent development. Practically, their first serious contact took place in Illyrian heraldry. Orbini lacked the main motivation of the author of the Illyrian armorial to position Macedonia in the first heraldic field on the dominion coat of arms of the Nemanjich dynasty. The change of the places of the Macedonian and Bulgarian coats of arms in his work is consistent with its content. In both Stematographias, it is more than clear from the comments on the descriptions of the coats of arms that the coats of arms of European heraldry were known and used as examples, but also for comparison. On the other hand, there is no evidence or hint in them to correct a previous mistake in the position or coloring of the Macedonian and Bulgarian arms in the Illyrian armorial. Commenting on Bulgaria, Vitezovich essentially pointed out the misuse of the two coats of arms in the Illyrian armorial, and, as mentioned, he had two of its transcripts. Additionally, in the comment on Macedonia, Vitezovich informs us that the Nemanjich dynasty used a red insignia for Macedonia. The rest of the comments show that the Macedonian coat of arms is in the context of those of Alexander the Great and Epirus, and the Bulgarian coat of arms is in the context of those arms of Wallachia and Mysia. The connection of Greece to the Macedonian blazon is unclear, as no other known source has indicated such a thing. Zhefarovich, for his part, only continued and revived Vitezovich’s work with a slightly altered goal. In no case can we talk about any unintentional intervention or accidental omission by Vitezovich and Zhefarovich in relation to the blazons of the Macedonian and Bulgarian arms.

The analysis of the sources used by Matkovski in The Coats of Arms of Macedonia indicate clearly that the coat of arms with lion Gules or Or attributed to Macedonia are almost equally found across sources. However, one can also note that from the second half of the XVIII century until the early twentieth century, eight of the ten sources which are mentioned by Matkovski are represented with an Or, a lion gules. This development is probably due to the enormous influence of the printed Stemmatographies, which were much more accessible. If we know that the impact of the Stemmatographies was not only strong and meaningful for the shaping of the idea of the Macedonian coat of arms but also for the arms of other Balkan countries, then it is unavoidable to conclude that the claim that the Or, a lion Gules is alien to the Macedonian heraldic tradition and awareness is historically and factually incorrect. It seems that the time when we should responsibly and consciously accept that there is no clear winner between the two main versions of the Macedonian coats of arms in Illyrian heraldry with lion has come. The proclamation of one as more Macedonian than the other is, from a scientific point of view, impossible.