The Genealogical Message of Beatrix Frangepán †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Background Concepts

3.1. Numbering the Ascendants in Table 1

3.2. Archaeogenetics

4. Data Acquisition

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LM | Last modified |

| CH | Checked (by the Authors) |

References

Primary Sources

Schwennicke, Detlev (Hrsg). 1981/1984/1985/1989/1992/1995. Europäische Stammtafeln, Neue Folge. 1981: Bd. IV., 1984: Bd. II., Bd. III/1., 1985: Bd. III/3., 1989: Bd. III/4., 1992: Bd. XII., 1995: Bd. XVI. Marburg: J. A. Stargardt. (Indicated in the text as ES.II.T., ES.III/1.T., ES.III/3.T., ES.III/4.T., ES.IV.T., ES.XII.T., ES.XVI.T. plus the actual Table number).Schwennicke, Detlev. 1989/1999/2010. Europäische Stammtafeln, Neue Folge. Bd. I/1., Bd. I/2., Bd. XXVII. Frankfurt am Main: V. Klostermann. (Indicated in the text as ES.I/1.T., ES.I/2.T., ES.XXVII.T. plus the actual Table number).Secondary Sources

- Andreeva, Tatiana, Andrey Manakhov, Svetlana Kunizheva, and Evgeny Rogaev. 2021. Genetic evidence of authenticity of a hair shaft relic from the portrait of Tsarevits Alexi, son of the last Russian Emperor. Biochemistry (Moscow) 86: 1572–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsma, Hartmut, ed. 1989. La Neustrie. Les Pays au Nord de la Loire de 650–850. Sigmaringen: Thorbecke. [Google Scholar]

- Bánfai, Zsolt, Erzsébet Kövesdi, Gergely Büki, András Szabó, Lili Magyari, Valerián Ádám, Ferenc Pálos, Attila Miseta, Miklós Kásler, and Béla Melegh. 2023. Characterization of Danube Swabian population samples on a high-resolution genome-wide basis. BMC Genomics 24: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bárány, Attila, Máté Kavecsánszki, László Pósán, and Levente Takács. 2019. Hunyadi Mátyás és kora [Mátyás/Matthias Hunyadi and his age, in Hung.]. Debrecen: MTA-Debreceni Egyetem Magyarország a Középkori Európában Lendület Kutatócsoport. [Google Scholar]

- Bogucki, Mateusz. 2016. Intercultural relations of the inhabitants of Polish territory in the 9th and 10th centuries. In The Past Societies. Polish Lands from the First Evidence of Human Presence to Early Middle Ages, 500 AD–1000 AD. Edited by Przemyslav Urbanczyk and Maciej Trzeciecki. Warszawa: Polish Academy of Sciences, pp. 223–76, particularly: 256. [Google Scholar]

- Borbély, Noémi, Orsolya Székely, Bea Szeifert, Dániel Gerber, István Máthé, Elek Benkő, Balázs Gusztáv Mende, Balázs Egyed, Horolma Panjav, and Anna Szécsényi-Nagy. 2023. High coverage mitogenomes and Y Chromosomal typing reveal ancient lineages in the modern-day Székely population in Romania. Genes 14: 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bord, Lucien-Jean, and Hervé Pinoteau. 1980. Généalogie Commentée des rois de France. Chiré-en-Montreuil: Éditions de Chiré. [Google Scholar]

- Braamcamp, Anselmo. 1921. Livro primeiro dos Brasöes da Sala Sintra. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, Guido, Anna Szécsényi-Nagy, Christina Roth, Kurt Werner Alt, and Wolfgang Haak. 2014. Human palaeogenetics of Europe–the known knowns and the known unknowns. Journal of Human Evolution 79: 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, Maria Concetta. 2018. L’epoca dei Ruffo di Sicilia. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Caramelli, David. 2009. Antropologia Molecolare: Manual di Base. Firenze: Firenze University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ciorciari, Vincenzo. 2011. Storie dei Sanseverino Nella Storia del Meridione. Sala Consiliana: Arti Grafiche Lapelosa. [Google Scholar]

- d’Abdal de Vinyals, Ramon. 1991. Els Primers Comtes Catalan, 1st ed. Barcelona: Teide Editorial, Reprint: [2nd ed.] Barcelona: Vicens-Vives/El Observador. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]

- de Sosa, (Fra) Jerónimo. 1676. Noticia de la Gran Casa de los Marqueses de Villafranca y su Parentesco con las Mayores de Europe. Nápoles [Napoli]: Novelo de Bonis (Impresor arzobispal de Nápoles). [Google Scholar]

- Del Regno, Massimo. 1991. I Sanseverino Nella Storia d’Italia. Cronologia Storica Comparata. Mercato San Severino: Italia Nostra. [Google Scholar]

- Della Monica, Nicola. 1998. Le Grandi Famiglie di Napoli. Roma: Newton & Compton. [Google Scholar]

- Di Muro, Alessandro. 2010. Le contoee longobarde e l’origine delle signorie territoriali nel Mezzogiorno. Archivio Storico per le Province Napoletane 128: 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Doubleday, Simon R. 2004. Los Lara. Madrid: Ed. Turner. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, Pál. 1996. Magyarország világi archontológiája [Secular archontology of Hungary, in Hung.]. Budapest: História—MTA Történettudományi Intézet, vols. I–II. [Google Scholar]

- Eytzinger, Michael. 1590. Thesaurus Principium Hac Aetate in Europa Viventium. Colonia [Köln]: God. Kempensis. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Michal, Guido A. Gnecchi-Ruscone, Thiesas C. Lamnidis, and Cosimo Posth. 2021. Where Asia meets Europe–Recent insights from ancient human genomics. Annals of Human Biology 48: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Xesta y Vázquez, Ernesto. 2001. Relaciones del Condado del Urgel con Castilla y Leon. Madrid: E y P Libros Antiguos S. L. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, John V. A. 2006. When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans. Appendix: Simplified Genealogy of the Frankopans, Šubićs and Zrinskis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankopan_family_tree (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Fleckenstein, Josef. 1957. Über die Herkunft der Welfen und ihre Anfänge in Süddeutschland. In Studien und Vorarbeiten zur Geschichte des großfränkischen und frühdeutschen Adels (Gerd Tellenbach, Hrsg). Freiburg: Albert, pp. 71–136. [Google Scholar]

- Frangipane, Doimo. 1975. L’Archivio Frangipane. Udine: Accademia di Scienze, Lettere e Arti di Udine. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparri, Stefano. 2012. Italia Longobarda. Bari: Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, Marc-Édouard. 2008. Mille ans D’histoire de L’arbre Généalogique en France. Rennes: Éditions Quest-France, Edilarge. [Google Scholar]

- Gioffrè, Domenico. 2010. La Gran Casa dei Ruffo di Bagnara. Reggio Calabria: Equilibri. [Google Scholar]

- Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto, Anna Szécsényi-Nagy, István Koncz, Gergely Csíky, Zsófia Rácz, Adam Benjamin Rohrlach, Guido Brandt, Nadin Rohland, and Veronika Csáky. 2022. Ancient genomes reveal origin and rapid trans-Eurasian migration of 7th century Avar elites. Cell 185: 1402–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

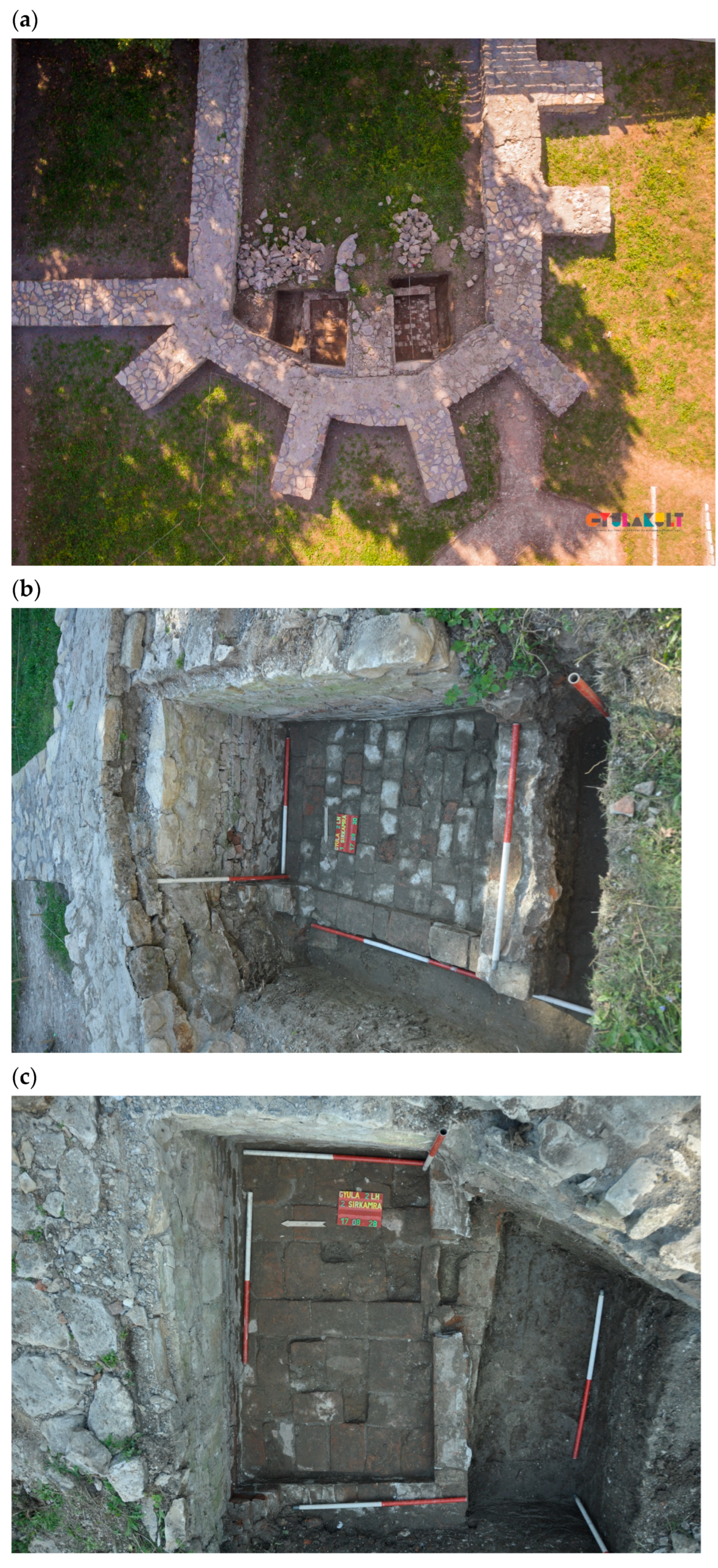

- Halmágyi, Miklós. 2020. A Ferences Kolostor Romjai. Gyula, Epreskert Utca 19. [Ruins of the Franciscan Monastery. Gyula, Epreskert utca 19. in Hung]; (LM 2020.11.17./CH 2023.03.07) [Miklós Halmágyi] . Gyula: Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Békés Vármegyei Levéltára. Available online: https://mnl.gov.hu/mnl/beml/hirek/a_ferences_kolostor_romjai_gyula_epreskert_utca_19 (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- Hartung, Wolfgang. 1998. Die Herkunft der Welfen aus Alamanien. In Die Welfen. Landesgeschichliche Aspekte ihrer Herrschaft (Karl-Ludwig Ay, Lorenz Maier, Joachim Jahn, Hrsg). Konstanz: UVK, pp. 23–55. [Google Scholar]

- Holjevac, Željko. 2005. Frankopani. Meridijani Broj 91: 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hóman, Bálint, and Gyula Szekfü. 1934. Magyar történet [Hungarian history, in Hung.]. Budapest: Királyi Magyar Egyetemi Nyomda, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Indelli, Tommaso. 2017. Gastaldati nel Lazio meridionale. Felix Terra 2017: 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Karácsonyi, János. 2004. A Magyar Nemzetségek a XIV Század Közepéig [The Hungarian clans/families to the middle of the XIVth Century, in Hung], 1st ed. Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, Reprint: Budapest: Nap Kiadó. pp. 436–46, 886–95. First published 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Kekulé von Stradonitz, Stephan. 1904. Ahnentafel-Atlas: Ahnentafeln zu 32 Ahnen der Regnenten Europas und ihrer Gemahlinen. Berlin: J. A. Stargardt Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- King, Turi E., Gloria Gonzalez-Fortes, Patricia Balaresque, Mark G. Thomas, David Balding, Pierpaolo Maisano Delser, Rita Neumann, Walter Parson, Michael Knapp, Susan Walsh, and et al. 2014. Identification of the remains of King Richard III. Nature Communication 5: 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaić, Vjekoslav. 1991. Krćki knezovi Frankopani, I. Od najstarjih vremena do gubitka Otoka Krka (od god. 1118, do god 1480), 1st ed. Zagreb: Izdanje “Matice Hrvatske”, [Reprint] Rijeka: Croatia Izdavčki Centar. First published 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Péter. 1990. Matthias Corvinus. Budapest: Officina Nova. [Google Scholar]

- Krisztik, János. 1891. A békésvármegyei régi kolostorok. [Ancient cloisters in Province Békés, Hung]. A Békésvármegyei Régészeti és Művelődéstörténeti Társulat Évkönyve 15: 70–77. First published 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Kubinyi, András. 2001. Mátyás király [King Mátyás/Matthias, in Hung.]. Budapest: Vincze Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle, Pierre. 2004. L’Occitanie, Histoire Politique et Culturelle. Toulouse: Puylaurens/Institut d’Études Occitans. [Google Scholar]

- Liska, András. 2013. Ősi romok–A gyulai ferencesek hagyatéka. [Ancient ruins–Legacy of the Franciscans of Gyula, in Hung]. Gyulai Hírlap, December 20, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Liska, András. 2015. Középkori régészeti adatok Gyula város belterületéről [Medieval archaeological data from the inner range of town Gyula, in Hung]. In Gyula város történetének kezdetei [Beginnings of the history of town Gyula, in Hung]. Gyula: Gyulai Önkormányzat [Municipality of Gyula]. [Google Scholar]

- Liska, András. 2017. Jelentés régészeti megfigyelés elvégzéséről a Gyula 2. sz. régészeti lelőhely (Ferences rendház) területén [Relation on the accomplishment of archaeological observation at the archaeological site Gyula no. 2. (Franciscan convent), in Hung]. Gyula: Relation for the Municipality of Gyula. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, Fernāo. 1735. Cronica del Rey D. Pedro I deste Nombre e dos Reys de Portugal o oitavo, Cognominando o Justiciero. Lisboa: Officina de Manoel Fernandes da Costa. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, Miroslav. 2002. Bellonides. Available online: http://w.genealogy.euweb.cz/barcelona/barcelona1.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Maróti, Zoltán, Endre Neparáczki, Oszkár Schütz, Kitti Maár, Gergely I. B. Varga, Bence Kovács, Tibor Kalmár, Emil Nyerki, István Nagy, Dóra Latinovics, and et al. 2022. The genetic origin of Huns, Avars and conquering Hungarians. Current Biology 32: 2858–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastronardi, Maria Aurelia. 1986. The Sanseverino dynasty of Salerno. Quaderni Medievali 21: 296–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mende, Balázs Gusztáv. 2017. Unpublished results.

- Mizuno, Fuzuki, Koji Ishiya, Masami Matsushita, Takayuki Matsushita, Katherine Hampson, Michiko Hayashi, Fuyuki Tokani, Kunihiko Kurosaki, and Shintaroh Ueda. 2020. A biomolecular anthropological investigation of William Adams, the first SAMURAI from England. Scientific Reports 10: 11651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozova, Irina, Pavel Flegontov, Alexander S. Mikheyev, Sergey Bruskin, Hosseinali Asgharian, Petr Ponomarenko, Vladimir Klyuchnikov, Ganesh Prasad ArunKumar, Egor Prokhortchouk, Yuriy Gankin, and et al. 2016. (Invited Review) Toward high resolution population genomics using archaeological samples. DNA Research 23: 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Péter L., Judit Olasz, Endre Neparáczki, Nicholas Rouse, Karan Kapuria, Samantha Cano, Huije Chen, Julie Di Cristofaro, Goran Runfeldt, Natalia Ekomasova, and et al. 2021. Determination of the phylogenetic origins of the Árpád Dynasty based on Y Chromosome sequencing of Béla the Third. European Journal of Human Genetics 29: 164–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neparáczki, Endre, Luca Kis, Zoltán Maróti, Bence Kovács, Gergely I. B. Varga, Miklós Makoldi, Pamjav Horolma, Éva Teiszler, Balázs Tihanyi, Péter L. Nagy, and et al. 2022. The genetic legacy of the Hunyadi descendants. Heliyon 8: E11731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Tibor. 2015. Mátyás herceg. (Szerény adalék a Hunyadi családhoz) [Prince Mátyás. A modest contribution to the Hunyadi family, in Hung]. Turul 88: 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nyerki, Emil, Tibor Kalmár, Oszkár Schütz, Rui M. Lima, Endre Neparáczki, Tibor Török, and Zoltán Maróti. 2023. correctKin: An optimized method to infer relatedness up to the 4th degree from low-coverage ancient human genomes. Genome Biology 24: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasz, Judit, Verena Seidenberg, Susanne Hummel, Zoltán Szentirmay, György Szabados, Béla Melegh, and Miklós Kásler. 2019. DNA profiling of Hungarian King Béla III and other skeletal remains originating from the Royal Basilica of Székesfehérvár. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11: 1345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, Ludovic, Robin Allaby, Pontus Skoglund, Clio Der Sarkissian, Philipp W. Stockhammer, Maria C. Avila-Arcos, Qiaomei Fu, Johannes Krause, Eske Willerslev, Anne C. Stone, and et al. 2021. Ancient DNA analysis. Nature Reviews, Methods, Primers 1: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pályi, Gyula, Klára Berzeviczy, and Zoltán Frenyó. 2021. Aquinói Szent Tamás Magyar Rokonai [Hungarian relatives of Saint Thomas of Aquin, in Hung]. Budapest: Szent István Társulat. [Google Scholar]

- Paviano, Onofrio. n.d. ([Onofrius Pavinius Veronensis], 23. 02. 1529.–27. 04. 1568). In De Gente Frangepania, Libri Quator. Città Stato Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Barb. Lat. 2481.

- Pfister, Christian. 1911. Neustria. In Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed. Edited by Hugh Chisholm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 19, p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- Pinoteau, Hervé. 1982. Les origines de la maison Capétienne. In Vingt-Cinq ans D’études Dynastiques. Edited by Hervé Pinoteau. Paris: Éditions Christian, pp. 141–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstetter, Monica D., Thomas D. Dyer, Donna M. Lehman, Joanne E. Curran, Ravindranath Duggirala, John Blangero, Jason G. Mezey, and Amy L. Williams. 2017. Benchmarking relatedness inference methods with genome-wide data from thousands of relatives. Genetics 207: 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renfrew, A. Colin, and Katie V. Boyle, eds. 2000. Archaeogenetics: DNA and the Population Prehistory of Europe. Cambridge: McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Martin B., Pedro Soares, and Antonio Torroni. 2016. Palaeogenomics: Mitogenomes and migrations in Europe’s past. Current Biology 26: R229–R246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogaev, Evgeny I., Anastasia P. Grigorenko, Yuri K. Moliaka, Gulaz Faskhutdinova, Andrey Golotsov, Arlene Lahti, Curtis Hildebrandt, Ellen L. W. Kittler, and Irina Morozova. 2009. Genomic identification in the historical case of the Nicholas II royal family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106: 5258–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, Giovanni. 2016. Note Riassuntive Sulla Famiglia Ruffo di Calabria. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20121026032022/http://www.bibliotelematica.org/Arch-Ruffo-Note_riassuntive_premessa.htm (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Salazar y Acha, Jaime de. 2008. La nobleza titulada medieval en la Corona de Castilla. Anales de la Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogia 11: 7–94. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar y Castro, Luis. 1697. Historia Genealógica de la casa de Lara. Cuatro Volumes. Madrid: Imprenta Real (Mateo de Llanos y Guzman). First published 1694. [Google Scholar]

- Scandone, Francesco. 1908. Il gastaldato di Aquino dalla metá del IX secolo alla fine del X. Archivio Storico per le Province Napoletane 32: 49–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schneidmüller, Bernd. 2000. Die Welfen. Herrschaft und Erinnerung (819–1252). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Settipani, Christian, and Patrick van Kerrebrouck. 1993. La préhistoire des Capétiens, 481–987. Premiere partie: Merovingiens, Carolingiens, Robertiens. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Patrick van Kerrebrouck Éd. [Google Scholar]

- Shama, Davide, and Pasquale Elia. 2020. Genealogia della famiglia Sanseverino (Ceglie). Available online: http://www.ideanews.it/antologia/elia/sanseverino%20genealogia.htm (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Sokcsevits, Dlnes. 2004. A magyar múlt horvát szemmel. [Hungarian Past with Croatian Eyes. in Hung.]. Budapest: Magyar a Magyarért Alapítvány. [Google Scholar]

- Sokcsevits, Dénes. 2007. Horvátország Közép-Európa és a Balkán között. [Croatia between Central Europe and the Balkans, in Hung.]. Budapest: Keateka Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Sokcsevits, Dénes. 2011. Horvátország. A 7. századtól napjainking. [Croatia. From the 7th century to our days, in Hung.]. Érd: Mundus Novus. [Google Scholar]

- Špoljarić, Luka. 2016. Hrvatski renesansi velikaši mitovi o rimskom porijeklu [Croatian renaissance lords and the myths of Roman origin]. Modruški Zbornik 26: 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Szatmári, Imre. 1994. Gyula középkori ferences temploma és kolostora. [Medieval Franciscan church and cloister of Gyula, in Hung.]. In Koldulórendi építészet a középkori Magyarországon. Tanulmányok. [Architecture of Medicant Orders in Medieval Hungary. Studies., in Hung]. Edited by Andrea Haris. Budapest: Országos Műemlékvédelmi Hivatal, pp. 409–35. [Google Scholar]

- Szeifert, Bea, Dániel Gerber, Veronika Csáky, Péter Langó, Dimitrii A. Stashenkov, Aleksandr A. Khokhlov, Ayrat G. Stidikov, Ilgizar R. Gazimzyanov, Elizaveta V. Volkova, Natalia P. Matveeva, and et al. 2022. Tracing genetic connections of ancient Hungarians to the 6th–14th century populations of the Volga-Ural region. Human Molecular Genetics 31: 3266–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szerémi, György. 1857. Epistola de Perdicione regni Hungarorum, 1484–1543. (Lat.) [Emlékirat Magyarország romlásáról, in Hung., Memoir of György Szerémi on the deterioration of Hungary]. Edited by Gusztáv Wenzel. Pest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia. [Google Scholar]

- Thallóczy, Lajos, and Samu Barabás. 1913. A Frangepán család oklevéltára. [Archive of the Frangepán family, in Hung. and Latin]. Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Könyvkiadóhivatala, vols. I and II. First published 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Vajay, Szabolcs. 1943. Spanyol királyok vére a Frangepán leszármazottakban. [Blood of Spanish Kings in the descendants of the Frangepáns, in Hung.]. Turul 57: 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, Gergely I. B., Lilla Alida Kristóf, Kitti Maár, Luca Kis, Oszkár Schütz, Orsolya Váradi, Bence Kovács, Alexandra Ginguta, Balázs Tihanyi, Péter L. Nagy, and et al. 2023. The archaeogenomic validation of Saint Ladislaus’ relic provides new insights into the Árpád Dynasty’s genealogy. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 50: 58–61. Available online: http://www.jgenetgenomics.org/en/article/doi/10.1016/j.jgg2022.06.008 (accessed on 16 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Vogtherr, Thomas. 2014. Die Welfen. Vom Mittelalter zur Gegenwart. München: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chuan-Chao, Cosimo Posth, Anja Furtwängler, Katalin Sümegi, Zsolt Bánfai, Miklós Kásler, Johannes Krause, and Béla Melegh. 2021. Genome-wide autosomal. mtDNA. and Y chromosome analysis of King Béla III of the Hungarian Árpád dynasty. Scientific Reports 11: 19210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Shao-Quing, Pan-Xin Du, Chang Sun, Wei Cui, Yi-Ran Xu, Hai-liang Meng, Mei-Sen Shi, Bo-Feng Zhu, and Hui Li. 2022. Dual origins of the Northwest Chinese Kyrgyz: The admixture of Bronze age Siberian Medieval Niru’un Mongolian Y chromosomes. Journal of Human Genetics 67: 175–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertner, Mór. 1892. I. Az első Kórógyiak [I. The first Kórógyis, in Hung]. Turul 10: 166–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, Chris. 1981. Early Medieval Italy: Central Power and Local Society 400–1000. London: MacMillan Press, pp. 174–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wurst, Christina, Frank Maixner, Vincent Castella, Giovanna Cipollini, Gerhard Hotz, and Albert Zink. 2022. The lady from Basel’s Barfüsserkirche–Molecular confirmation of the mummy’s identity through mitochondrial DNA of living relatives spanning 22 generations. Forensic Science International Genetics 56: 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berzeviczy, K.; Liska, A.; Pályi, G. The Genealogical Message of Beatrix Frangepán. Genealogy 2023, 7, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030053

Berzeviczy K, Liska A, Pályi G. The Genealogical Message of Beatrix Frangepán. Genealogy. 2023; 7(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerzeviczy, Klára, András Liska, and Gyula Pályi. 2023. "The Genealogical Message of Beatrix Frangepán" Genealogy 7, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030053

APA StyleBerzeviczy, K., Liska, A., & Pályi, G. (2023). The Genealogical Message of Beatrix Frangepán. Genealogy, 7(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030053