The Development of the State Emblems and Coats of Arms in Southeast Europe

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. First Period (1821–1944)

2.1. Greece

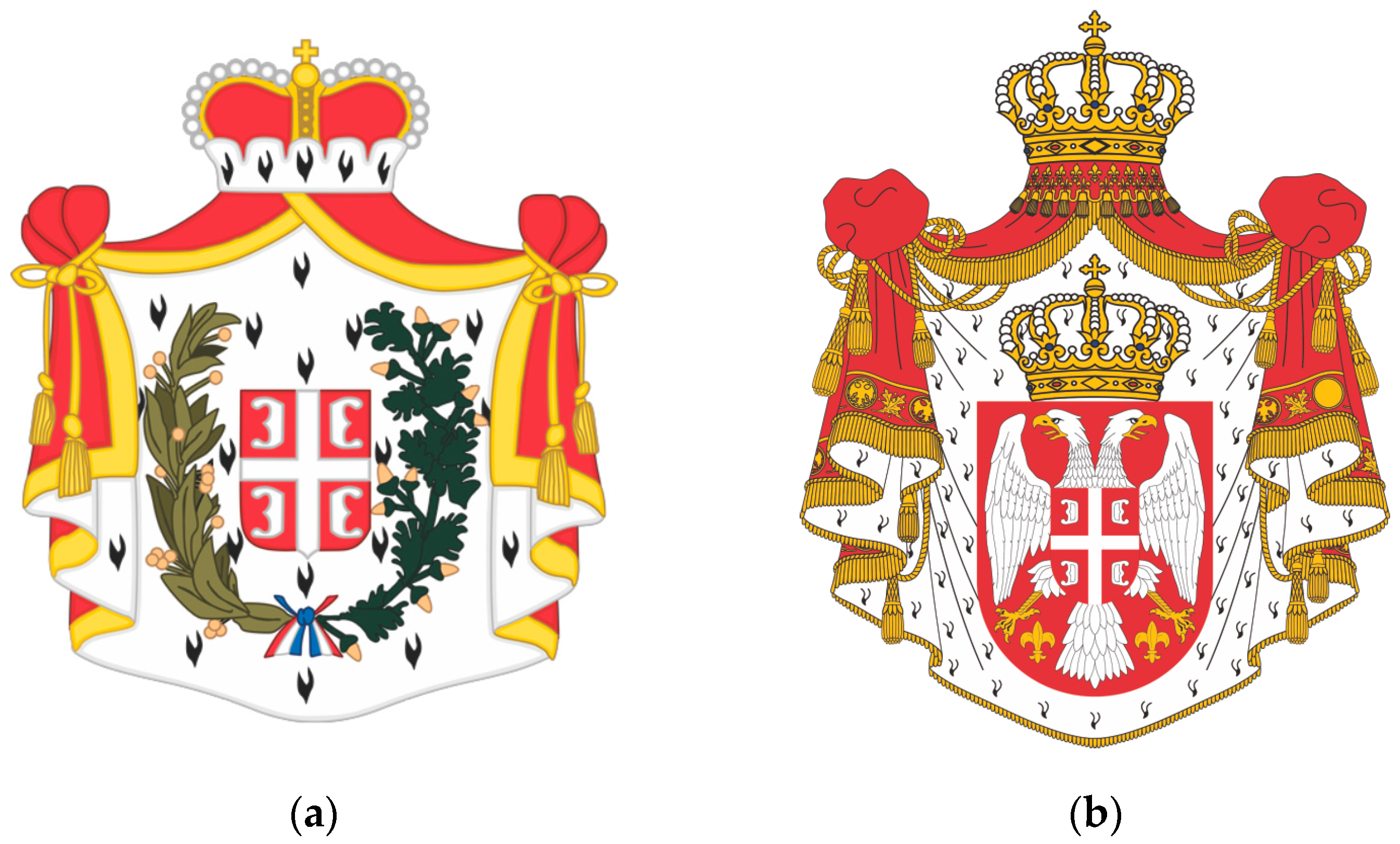

2.2. Serbia

2.3. Romania

2.4. Bulgaria

2.5. Albania

2.6. Montenegro

2.7. Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina Immediately before and within the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes

2.7.1. Croatia

2.7.2. Bosnia and Herzegovina

2.7.3. Slovenia

3. Second Period (1945–1989)

3.1. Greece

3.2. Albania

3.3. Bosnia and Herzegovina

3.4. Bulgaria

3.5. Macedonia

3.6. Romania

3.7. Slovenia

3.8. Serbia

3.9. Croatia

3.10. Montenegro

4. Third Period (after 1990)

4.1. Albania

4.2. Serbia

4.3. Bulgaria

4.4. Romania

4.5. Bosnia and Herzegovina

“The coat of arms of Bosnia and Herzegovina is blue and in the form of a shield with a pointed end. There is a yellow triangle in the upper right corner of the shield. A row of white five-pointed stars runs parallel to the left side of this triangle.” (Figure 30b)

4.6. Slovenia

4.7. Macedonia

4.8. Kosovo

4.9. Croatia

4.10. Montenegro

5. Analysis

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Here we should point out the difference in the understanding of the term “coat of arms” in English heraldry and in its use in Balkan languages and understanding, especially used by the laws referring to their national Emblems as a “Coat of Arms” regardless of if they are good heraldry, Socialist heraldry or no heraldry at all. Due to the lack of real Western heraldic practice (apart from Romania, Slovenia and Croatia), and especially lacking theoretical heraldry to deal with the different aspects of the usage of symbol, emblem, and coat of arms, the national emblem is referred to as a “Coat of arms”. Furthermore, there is a full concept of “Socialist heraldry” that existed in the entire region for a half century. In this article we will use terms “state emblem” for the emblems with no heraldry at all, “coat of arms” from perspective of Balkan heraldry which may differ from the English one. Also, we will use “socialist ‘coat of arms’” for the socialist emblem so-called coat of arms, by primary sources, Laws, and books on East European heraldry. |

| 2 | Coats of arms are viewed as symbols by symbolic interactionism. Emblem in Balkan context could be used as equivalent to English “charge” for the figure on the shield. |

| 3 | Heraldically right-hand, but left-hand for the observer |

| 4 | Poland deviated least from its historical coat of arms, a silver eagle on a red shield, making only a small intervention by removing the crown. Czechoslovakia retained its historic coat of arms, a red and silver two-tailed lion, but instead of the crown, a red five-pointed star with a gold border has been found. The small shield on the lion’s chest, with a double bishop’s cross, which historically represented Slovakia, was replaced by a flame symbol owing to the religious connotation. |

References

- Зaкoн зa Гepб зa Peпyбликa Бългapия, 1997. Oбн. ДB. бp.62 oт 5 Aвгycт 1997г.

- Зaкoн зa гpбoт нa Hapoднa Peпyбликa Maкeдoниja, Пpeзидиyм нa нapoднoтo coбpaниe нa Hapoднa Peпyбликa Maкeдoниja, 1946. бp 559, Cкoпje 27 Jyли 1946.

- Зaкoн o гpбy Kpaљeвинe Cpбиje. 1882, Cpпcкe нoвинe, June 20. бp. 135/1882.

- Зaкoн o изглeдy и yпoтpeби гpбa, зacтaвe и xимнe Peпyбликe Cpбиje. 2009, Cлyжбeни глacник Peпyбликe Cpбиje, бp. 36/2009.

- Зaкoн o yпoтpeби зacтaвe, xимнe и гpбa Caвeзнe Peпyбликe Jyгocлaвиje, Cлyжбeни лиcт CPJ, 1993. 66/93 и 24/94. Зaкoн o гpбy Caвeзнe Peпyбликe Jyгocлaвиje, Cл. лиcт CPJ 66/93.

- Božić, Mate, and Stjepan Ćosić. 2021. Hrvatski grbovi. Geneza, simbolika, povijest. Zagreb: Hrvatska Sveučilišna Naklada, Filozofski Fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, Institut Društvenih Znanosti “Ivo Pilar”. [Google Scholar]

- Boйникoв, Ивaн. 2017. Иcтopия нa Бьлгapcкитe дьpжaвни cимвoли, B. Tьpнoвo; Aбaгap.

- Čaldarović, Dubravka Peić, and Nikša Stančić. 2011. Povjest Hrvatskoga Grba. Zagreb: Školska knjiga. [Google Scholar]

- Constituţia Republicii Populare Române. 1948, In Monitorul Oficial. nr. 87 bis din 13 aprilie 1948.

- Constituţia Republicii Populare Române. 1952, In Buletinul Oficial. nr. 1 din 27 septembrie 1952, art. 102.

- Constituţia Republicii Socialiste România. 1965, In Buletinul Oficial. nr. 1 din 21 august 1965, art. 116.

- Filipović, Emir O. 2008. Grb i zastava Bosne i Hercegovine u 20. Stoljeću. In Bosna Franciscana. XVI-28. Sarajevo: Časopis Franjevačke Teologije. [Google Scholar]

- Filipović, Emir O. 2020. Lajos Thalloczy i bosnaksa heraldika. In Radovi. XIV/1. Sarajevo: Filozofski Fakultet. [Google Scholar]

- Hapoднoтo coбpaниe нa Hapoднa Peпyбликa Maкeдoниja изглaca нeкoлкy зaкoни вaжни зa нaшиoт нapoд, 1946. Hoвa Maкeдoниja. July 28.

- Heimer, Željko. 2008. Grb i zastava Republike Hrvatske. Zagreb: Leykam International. [Google Scholar]

- Hribovšek, Aleksander. 2011. Zgodovina Slovenskih državnih Grbov. Available online: http://www.grboslovje.si/novice/article_2011_12_20_0005.php?fbclid=IwAR06IqCSvO3ZYNWKf3qcM9oXatBM3cJzsjBUv7HAN2kgU8vnWlf-j0ARuQ4 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Hribovšek, Aleksander. 2018. Triglav, Plečnik in Razvoj Slovenskega Grba. Available online: http://www.grboslovje.si/novice/2018_11_19_0003.php (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Implementing UNMIK Regulation No. 2001/9 on a Constitutional Framework for Provisional Self-Government in Kosovo, 2003. Administrative Direction No. 2003/15. July 2.

- Înaltul Decret Domnesc. 1867. nr. 696 din 23 aprilie 1867. In Monitorul Oficial. nr. 100 din 5/17 mai 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Înaltul Decret Domnesc. 1872. nr. 498 din 8 martie 1872. In Monitorul Oficial. nr. 57 din 11/23 martie 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Înaltul Decret Regal. 1921. nr. 3573 din 23 iulie 1921. In Monitorul Oficial. din data de 29 iulie 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Jonovski, Jovan. 2009. Гpбoвитe нa Maкeдoниja—Coats of Arms of Macedonia. Maкeдoнcки xepaлд—Macedonian Herald, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joнoвcки, Joвaн. 2015. Cимбoлитe нa Maкeдoниja. Cкoпje: Cилcoн. [Google Scholar]

- Joнoвcки, Joвaн. 2019a. Paзвoj нa мaкeдoнcкaтa xepaлдичкa миcлa. Иcтopиja, LIV, 1. Cкoпje: ЗИPM. [Google Scholar]

- Joнoвcки, Joвaн. 2019b. Coнцeтo и лaвoт кaкo cимбoли вo xepaлдикaтa и вeкcилoлoгиjaтa нa Maкeдoниja. Cкoпje: Maкeдoнcкo гpбocлoвнo дpyштвo. [Google Scholar]

- Jonovski, Jovan. 2019. Ocвpт зa пpoцecoт нa ycвojyвaњe нa дpжaвнитe cимбoли нa Peпyбликa Maкeдoниja вo 1992 гoдинa—Review of the Process of Adoption of the State Symbols of the Republic of Macedonia in 1992. Maкeдoнcки xepaлд—Macedonian Herald, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonovski, Jovan. 2020. Блaзoниpaњe нa cтeмaтoгpaфиитe нa Bитeзoвиќ и Жeфapoвиќ—Blazoning the Stemmatographias of Vitezovic and Zhefarovic. Maкeдoнcки xepaлд—Macedonian Herald, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koнcтитyция нa Peпyбликa Бългapия, 1991. oт 13.07.1991 г.

- Koнcтитyциятa нa Бългapcкoтo княжecтвo, 1879. Tъpнoвo, 16д aпpилъ.

- Kpyнa вoди peпyбликy. 2006, In Beчepњe нoвocти. 27. jyн 2006.

- Laswell, Harold D., Daniel Lerner, and Ithiel de Sola Pool. 1952. The Comparative Study of Symbols. An Introduction. Hoover Institute Studies. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latifi, Qëndrim. 2022. Heraldika Shqiptare. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/heraldikashqiptare (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Ljigji nr. 03/l-038 për Përdorimin e simboleve shtetërore të Kosovës, Gazeta zyrtare e Republikës së Kosovës/prishtinë: viti iii/nr, 2008. 26/02 qershor 2008.

- Mapкyш, Joвaн Б. 2007. Гpбoви, зacтaвe и xимнe y иcтopиjи Цpнe Гope. Бeoгpaд: Cвeтигopa, (Уставъ 1835), Уставъ Княжевства Сербiе, 1835, Княжескo-Сербска Типoграфiя, Крагуевац. [Google Scholar]

- Monitorul Oficial al României, 2016. Partea I. nr. 542 of 19. 6. 2016.

- Nacrt Ustava NR BiH. 1946, In Sarajevo, Sarajevski Dnevnik. br. 429, god. II, 15. 11. 1946, 2.

- Νόμος 851/21-12-1978 (ΦΕΚ 233 τ. A΄) Περί εθνικής Σημαίας, των Πολεμικών Σημαιών καί του Διακριτικού Σήματος τού Προέδρου τής Δημοκρατίας, 1978.

- Neni 7, Ligj per formen dhe permasat e Flamurit Kombetar permbajtjen e Himnit Kombetar formen dhe permasat e Stemes se Republikes se Shqiperise dhe menyren e perdorimit te tyre, 2002 July 22.

- Odluka da se pristupi raspravi o promjeni Ustava Socijalističke Republike Hrvatske, 1990. 29. lipnja 1990. Narodne novine, br. 28/1990, 30. lipnja 1990. (Odjeljak III. pod 2.) (Heimer, 178).

- Okružnica Kabineta bana Banovine Hrvatske. 1940. br. 64178-1940. od 10. rujna 1940, (Inventarski broj Hrvatskoga povijesnog muzeja HPM/PMH 6387a, b) in Heimer. Grb i zastava, 175.

- Poljak, Tijana Trako. 2013. Uloga državotvornih simbola u izgradnji identiteta hrvatskog društva. Ph.D. dissertation, Filozofski Fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, Zagreb, Croatia. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, R. W. 2010. Balkanization. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Balkanization (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Sbornik zakonah i naredabah valjanih za kraljevinu Hrvatsku i Slavoniju, kom. V. Zagreb. 1868. Grb i zastava Hrvatske. Edited by Željko Heimer. Zagreb: Laykam, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Šišić, Ferdo. 1920. Dokumenti o postanku Kraljevince Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca 1914–1919. Zagreb: Naklada “Matice Hrvatske”. [Google Scholar]

- Stančić, Nikša. 2007. Kako je nastao grb Republike Hrvatske? Grb i Zastava, 1/2007.

- The Emblem. n.d. Available online: https://www.quirinale.it/page/emblema_en (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- The Flag. n.d. Available online: https://www.presidency.gr/en/presidency/the-flag/ (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- The National Emblem. n.d. Available online: https://www.presidency.gr/en/presidency/the-national-emblem/ (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Ustav, Kraljevne Srba, and Hrvata i Slovenaca. 1921. Službene novine Kraljevine Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, br. 142A, June 28.

- Ustav Narodne Republike Hrvatske, 1947. 18. siječnja 1947. Narodne novine, br. 7/1947,23. siječnja 1947.

- Ustav Republike Bosne i Hercegovine (Prečišćeni tekst), 1993. Službeni list R BiH, god. II, br.5, 14. 3. 1993.

- Ustavo Ljudske Republike Slovenije, 1947. 17 januarja 1946. Uradni list Ljudske republike Slovenije, št. 4.A, 24.01.1947.

- Varfi, Djin. 2000. Heraldika Sqiptare. Tiranë: Dituria. [Google Scholar]

- Уpeдбa o yтвpђивaњy opигинaлa вeликoг и мaлoг гpбa, opигинaлa зacтaвe и нoтнoг зaпиca xимнe Peпyбликe Cpбиje, 2010. 11.11.2010, Cлyжбeни глacник PC, бp. 85/2010, 15. 10. 2010.

- Уcтaв зa Kњaжeвинy Цpнy Гopy, 1905. Цeтињe.

- Уcтaв нa Φeдepaтивнa Hapoднa Peпyбликa Jyгocлaвиja. 1946. 31.01.1946, Cлyжбeн лиcт нa ΦHPJ, 10/1946, 01.02.1946.

- Уcтaв Hapoднe Peпyбликe Цpнe Гope. 1946. 31.12.1946. Cлyжбeни лиcт HP Цpнe Гope, 2/1947, 15.01.1947.

- Уcтaв нa Hapoднa Peпyбликa Maкeдoниja. 1946. Cкoпje: Пpeзидиyм нa ycтaвoтвopнoтo coбpaниe нa Hapoднa Peпyбликa Maкeдoниja, December 31.

- Уcтaв Hapoднe Peпyбликe Cpбиje, 1947. 17. jaнyap 1947.

- Уcтaв нa Coциjaлиcтичкa Φeдepaтивнa Peпyбликa Jyгocлaвиja. 1963. 07.04.1963, Cлyжбeн лиcт нa CΦPJ, 14/1963, 10.04.1963.

- Zakon o grbu, zastavi i himni Republike Hrvatske, te zastavi i lenti Predsjednika Republike Hrvatske, 1990. 21. prosinca 1990, Narodne novine, br. 55/1990, 21. prosinca 1990. Heimer, Grb i zastava. 182.

- Zakon o grbu, zastavi in himni Republike Slovenije ter o slovenski narodni zastavi, 1994. 20. X. 1994. Uredni list, št. 67, str. 3715-20, 27. X. 1994.

- Zakon o grbu Bosne i Hercegovine, 1998. Službeni list BiH, god. II, br. 8, 25. 5. 1998.

- Zakonska odredba o državnom grbu, državnoj zastavi, Poglavnikovoj zastavi, državnom pečatu, pečatima državnih i samoupravnih ureda, 28. travnja 1941, 1941. Nr.XXXVII-53-Z.p.-1941, 30. travnja 1941.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jonovski, J. The Development of the State Emblems and Coats of Arms in Southeast Europe. Genealogy 2023, 7, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030054

Jonovski J. The Development of the State Emblems and Coats of Arms in Southeast Europe. Genealogy. 2023; 7(3):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030054

Chicago/Turabian StyleJonovski, Jovan. 2023. "The Development of the State Emblems and Coats of Arms in Southeast Europe" Genealogy 7, no. 3: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030054

APA StyleJonovski, J. (2023). The Development of the State Emblems and Coats of Arms in Southeast Europe. Genealogy, 7(3), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7030054