1. Introduction

The origin of the “Castilla” surname has been a subject of debate among genealogists for many years. Males bearing the “Castilla” surname (referred to as Castilla men in this article) have been part of the Spanish royal family. This was the case for Pedro I de Castilla, el Cruel, and Isabel de Castilla (Isabel La Católica). Currently, there are different theories regarding the origin of this surname, which are not exclusive.

Documentary sources indicate that the origin of this surname was King Pedro I de Castilla, el Cruel, born in Burgos (north of Spain) in 1334 and died in Montiel, Valladolid (central Spain) in 1369. The son of Alfonso XI and María de Portugal, Pedro I was king in 1350. He had nine children, two of whom were males with offspring: Juan de Castilla y de Castro (1355–1405) and Diego de Castilla y de Sandoval (?–1458). Other documents indicate that the first male to bear this surname was Tello, the first count of Vizcaya. Tello was an illegitimate son of the king Alfonso XI and Leonor de Guzmán. Thus, the two men had a common ancestor, Alfonso XI.

Another possibility is that the surname refers to a specific place. The County of Castilla was one of the medieval counties of the Kingdom of León (850–1035), and the Kingdom of Castilla was one of the medieval kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (1035–1230). With the promulgation of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, two autonomous communities were recognized: Castilla-La Mancha and Castilla y León. According to some specialists, 77% of Spanish surnames are toponyms (

Álvarez 1968).

The third possibility is that some Castilla men bear the surname because of modifications to the other surnames. For instance, there are documents about a family that changed the surname Ruiz Castilla to Castilla (

Lucas 2008).

The study of different documents (civil records, parish records, etc.) has allowed the compilation of hundreds of genealogies. Generally, these genealogies indicate that there are, at least, three lineages (

Lucas 2008;

López-Parra et al. 2005).

- (1)

Lineage of descendants of Pedro I el Cruel.

- (2)

Lineage of Vadocondes (southern Burgos). These Castilla men have a common antecessor, Juan de Castilla de Vadocondes, born about 1550.

- (3)

Lineage of Rubena (northern Burgos). Castilla men have two possible antecessors: Pedro de Castilla de Rubena (1510) and Blas de Castilla de Rubena (1580).

Moreover, this surname is present in South America: in “Catálogo de Pasajeros a Indias”, there is a reference to Don Pedro de Castilla in 1560.

At present, this surname is widely represented in Spain (15,255 people with the first surname Castilla reported by the Spanish National Statistical Institute 1 January 2021), although it is not among the 100 most frequent surnames in Spain; there are 26,223 surnames with more than 100 bearers, men and women living in Spain, and the Castilla surname is in position 336. Nowadays, in the Iberian Peninsula, the largest number of people whose first surname is Castilla is located in Huelva (2.51%).

Although the Romans brought surnames to the Iberian Peninsula, they were not used until the end of the 9th century. Patronymics were the most used surnames, and the nobles were the only ones to use them. In documents from the end of the 12th century CE, surnames related to place of origin can be found (Salazar and Acha 1991). In the 15th century, hereditary surnames were relatively consolidated, mainly due to the initiative of Cardinal Cisneros, who made it mandatory to register in the parishes the marriages, births, and deaths of all the inhabitants, with information of their parents.

In most European and Hispano-American societies, surnames pass from generation to generation, from fathers to children, as the Y chromosome does. Males who share the same surname can be expected to belong to the same Y-chromosome haplogroup (

Jobling and Tyler-Smith 2003). Therefore, the comparison of DNA results and data in archives can, in theory, be useful for solving problems in the reconstruction of genealogies. However, this correlation only holds true if specific assumptions are made, namely: the surname has a unique origin, there were no illegitimacies (or adoptions), there were no deliberate surname changes responsible for the introduction of new Y-chromosome types, belonging to another surname group, and finally, Y chromosomes associated with different surnames must have been unrelated at the time of surname establishment (

Jobling 2001;

King and Jobling 2009). Mutations and genetic drift are also factors that need to be considered (

King and Jobling 2009). Mutations change the alleles of a haplotype of the Y chromosome in rapidly mutating markers (

Gusmão et al. 2005). Changes in the frequencies of the haplotypes by chance (genetic drift), together with the type of surname, for example, from a region or a profession, could favor the phenomena of associations of different haplotypes/haplogroups with the same surname.

Few molecular studies have been published on the analysis of a specific surname and its relationship with Y-chromosome haplotypes. The study of the surname Jefferson in a case of paternity of Thomas Jefferson (

King et al. 2007), the research regarding four microsatellites of Y chromosomes in 48 men bearing the surname Sykes (

Sykes and Irven 2000), surname Ye in China (

Zeng et al. 2019), and the case of the surname Colom in Spain are some examples (

Martínez-González et al. 2012).

The main goal of this study was to shed some light on the origin of the surname Castilla and to investigate the possible co-ancestry behind the living carriers of this surname. Genetic markers located in the Y chromosome-specific region were used to characterize the male lineages present in a sample of individuals whose paternal surname was Castilla. Thus, we pretended to establish the minimum number of founders and the expansion time of the lineages in our sample.

2. Results

Haplotype, haplogroup, and geographic origin for each individual can be found in

Table S1 and

Table 1. By analyzing Y-STRs, 55 different haplotypes were identified in the overall sample of 102 individuals. Of these, 71% were unique. This value is much lower than that of a general series of Spaniards in which 125 haplotypes were found in 148 individuals (91.2%).

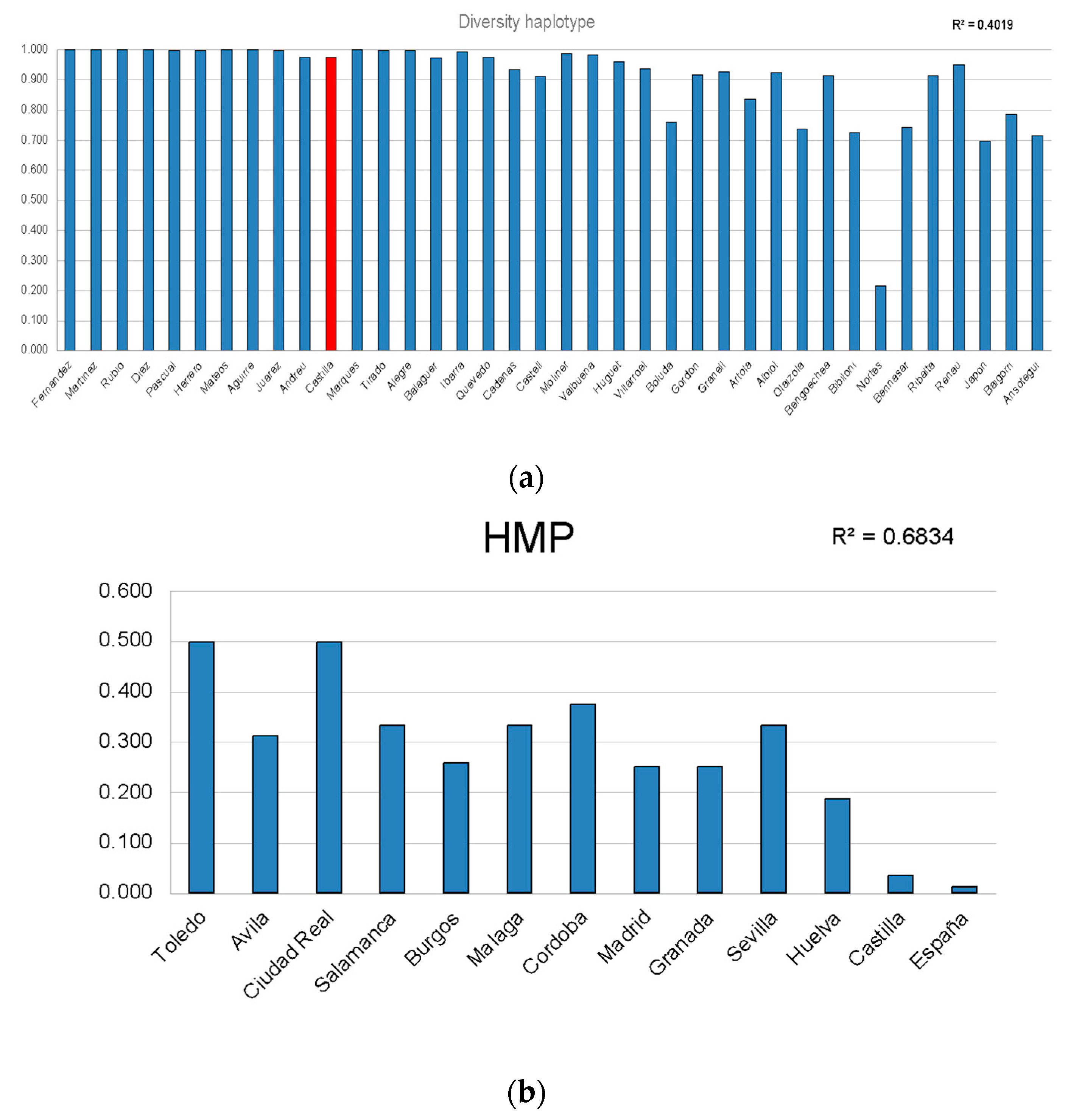

The Castilla groups, according to their origin, presented HD values similar to those observed in Spanish populations (

Martin et al. 2004) (

Table S1). The lowest values were observed for Burgos, Avila, Salamanca, and Granada. However, HMP in Castilla as a group was more than double that in the Spanish population (

Table S1).

When the distribution of haplogroups in the Castilla sample was considered, it was similar to that of the Spanish population (

Flores et al. 2004) (

Table 1). The R1b haplogroup was present in 49% of men with the surname Castilla; however, the frequency of the E1b1-M81 haplogroup (13.9%) was much higher than that found in the Iberian Peninsula population (4.03%) (

López-Parra 2008). Haplogroups O1b1 and Q-M346 were more frequent in the Asian and American populations. These haplogroups were present among the samples collected in this study, although at a low frequency, similar to the general Spanish population (

Flores et al. 2004).

The surname Castilla can be considered a frequent surname, with a number of bearers of 15,255 individuals in the Spanish population (INE 2021). Haplotype diversity was compared with the frequency of the surname. When considering other Spanish surnames for which information is available for the same markers (

Martínez-Cadenas et al. 2016), the pattern resembles that of frequent surnames (R

2:0.402) (

Figure 1a). In addition, when representing the distribution of the samples collected according to their province of origin, a strong correlation was observed (R

2:0.683) (

Figure 1b). This shows that areas where Castilla is less frequent have higher HMP values.

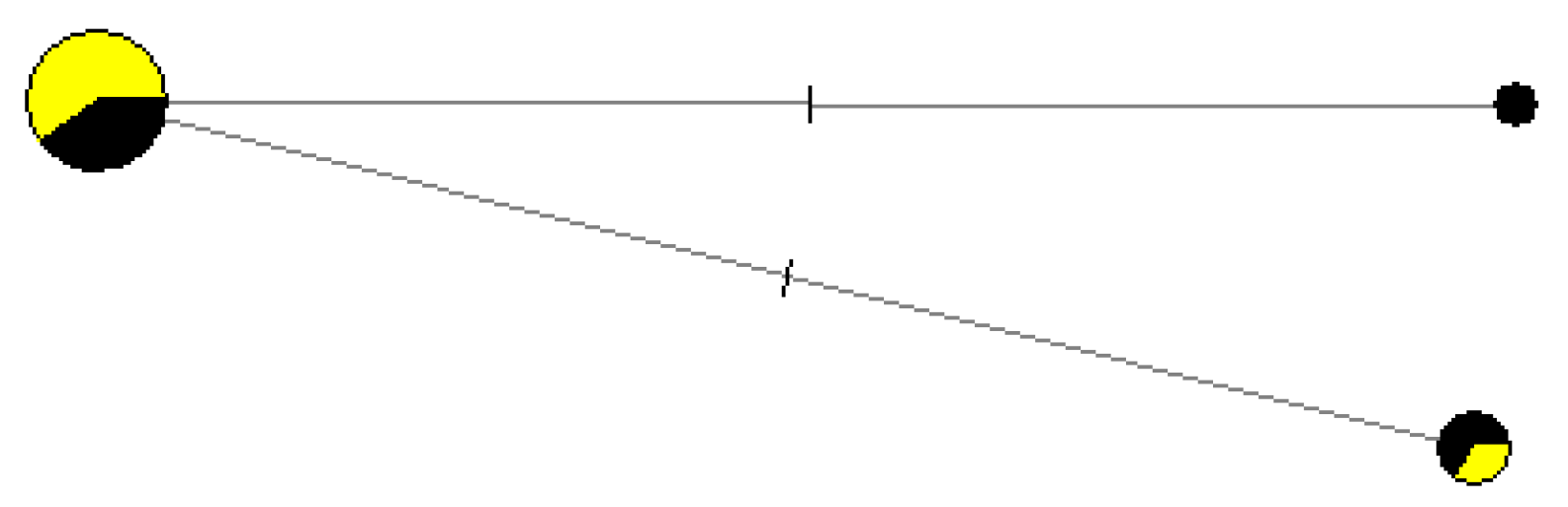

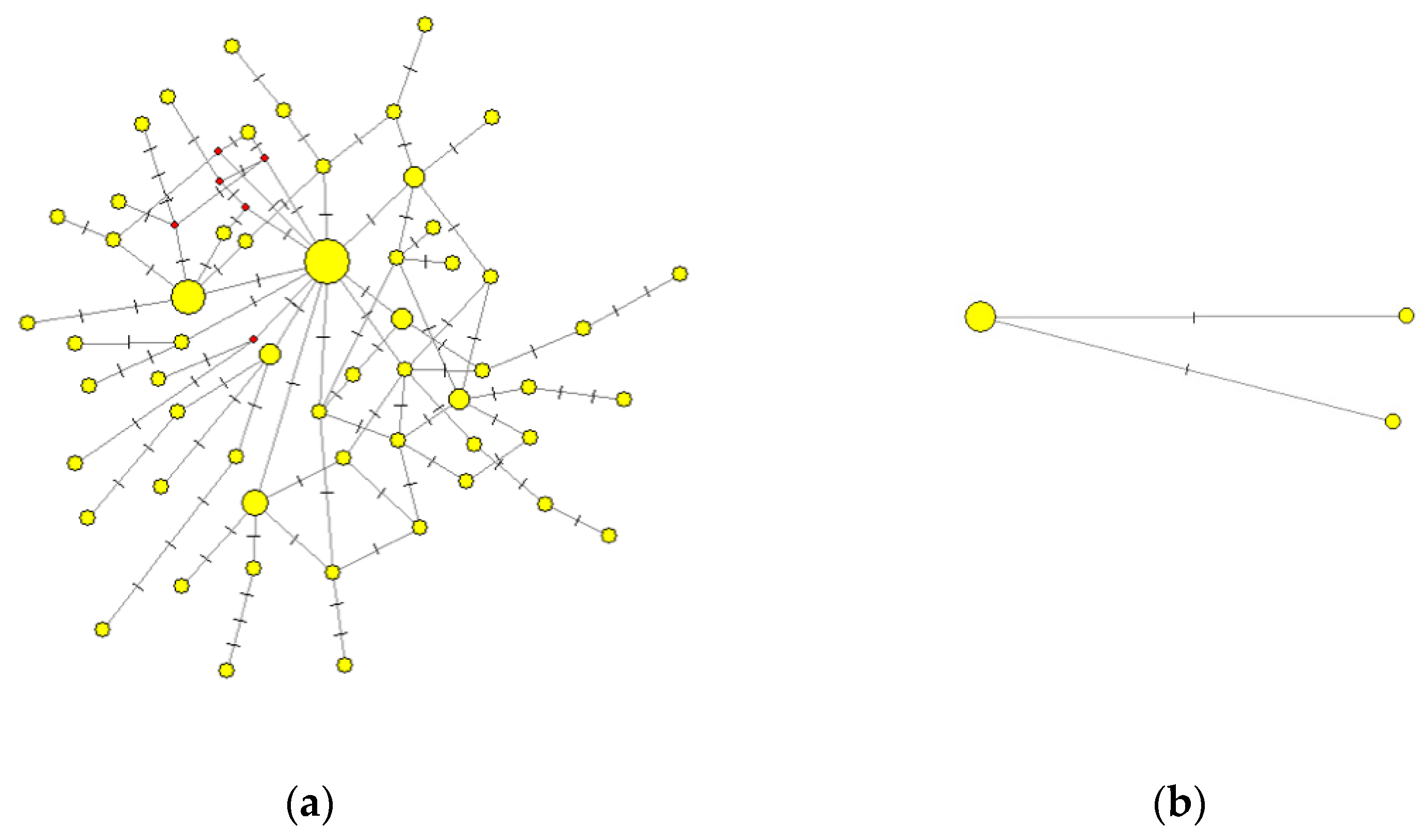

It was only possible to create networks for the haplotypes of the R1b and E-M81 haplogroups, as the other haplogroups did not meet the criteria for performing the network since there were not at least three different haplotypes. Regarding the E-M81 haplogroup, it was observed that 50% of the haplotypes corresponded to individuals from Burgos, and that all but one belonged to the same cluster. The two haplotypes that presented a lower frequency were only one step away, in one case in DYS389I and in the other DYS389II (

Figure 2).

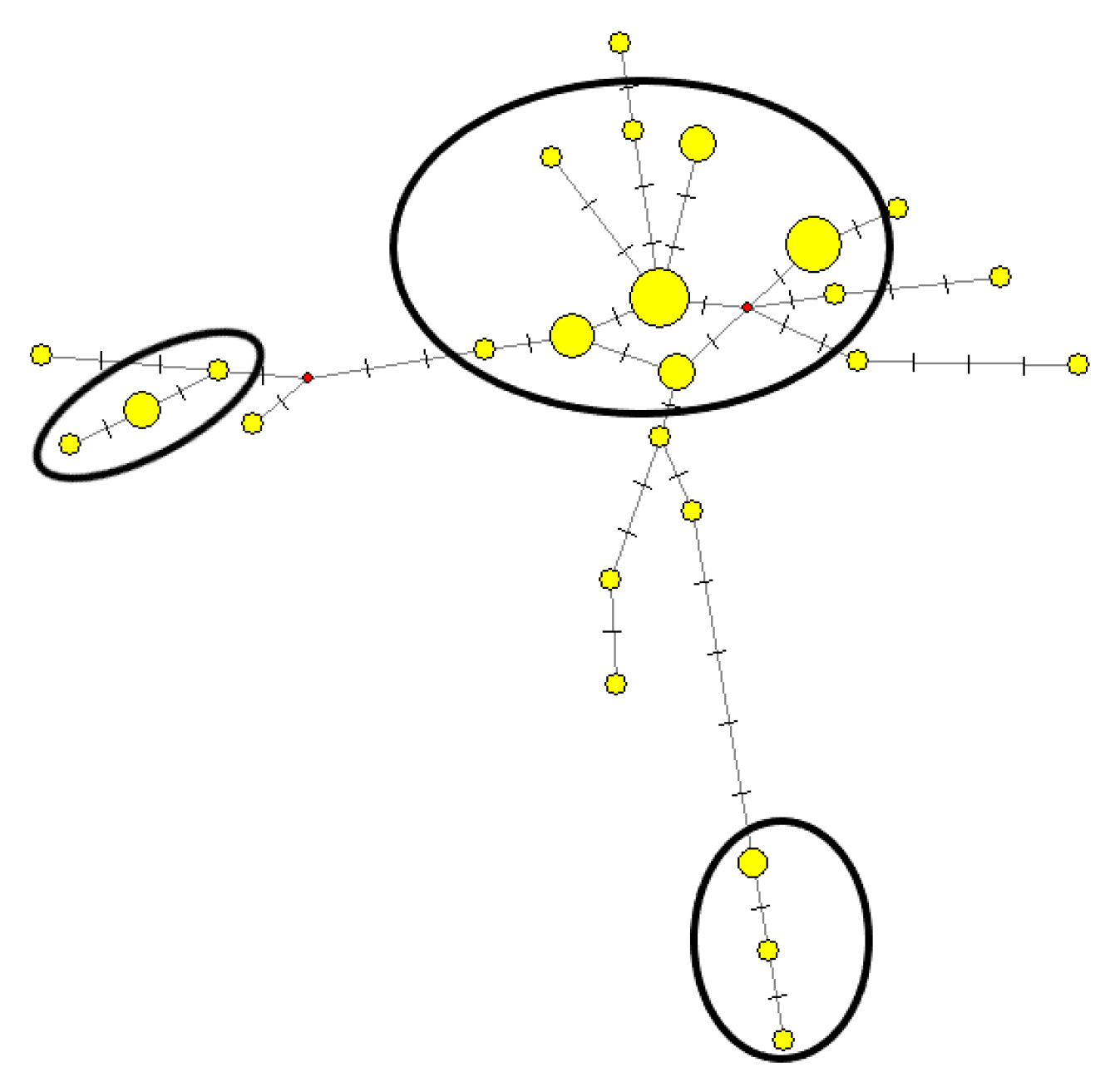

Regarding the network of the R1b haplogroup, one possible ancestral descent cluster was observed, which comprised 58% of the total Castilla R1b population (

Figure 3). This descent cluster was compatible with the founder effect. It is also characterized by individuals whose origin is in the north of the Iberian Peninsula (

Figure 4), specifically in Ávila, Salamanca, and Burgos. Since two smaller descent clusters were observed, grouping five and four haplotypes, more than 77% of the haplotypes R1b obtained were within these three main clusters or in descent clusters.

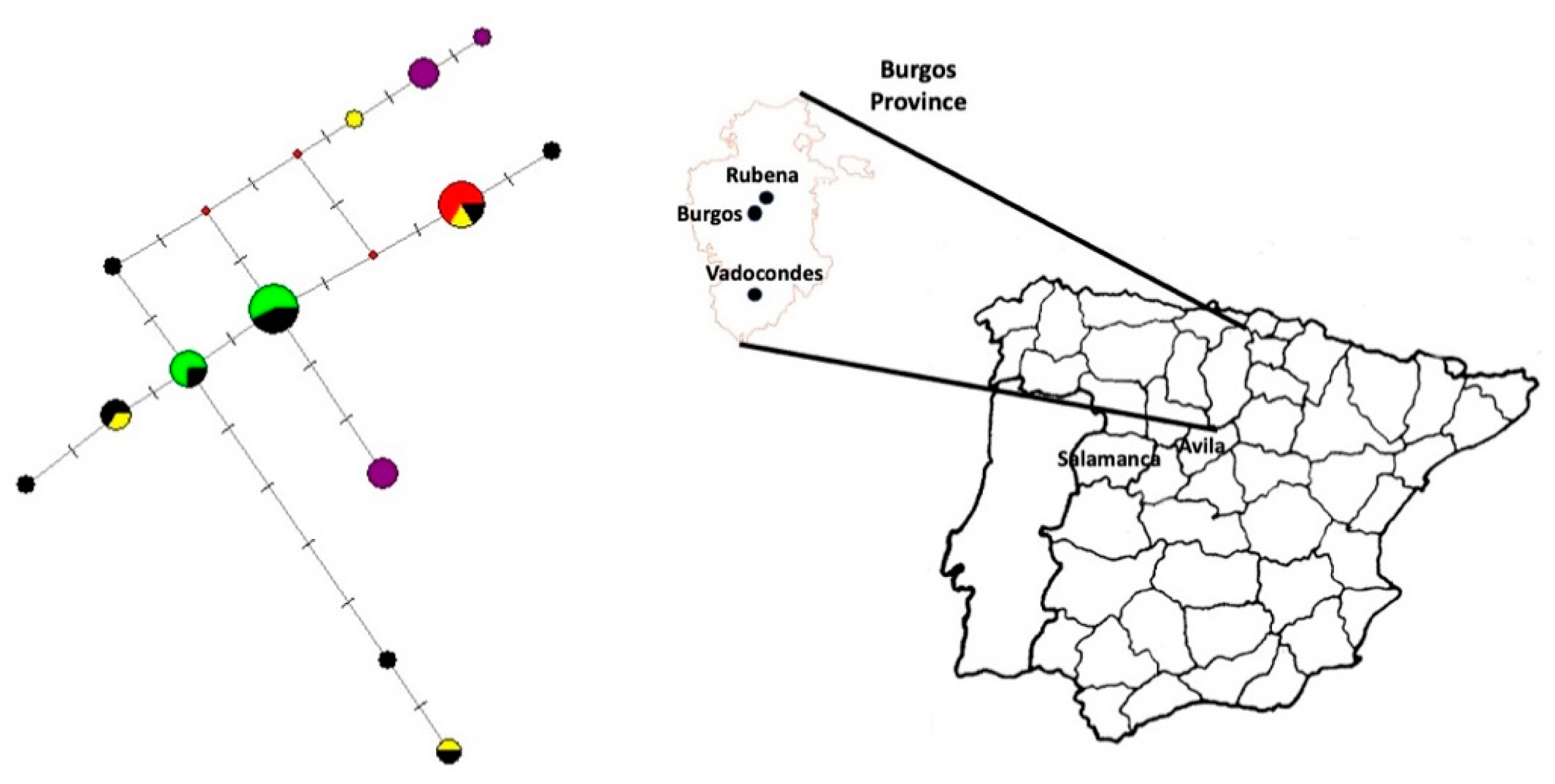

To test the hypothesis of an alleged origin of the Castilla surname in Burgos (see introduction), a network was performed with haplotypes whose origin was in Burgos and haplotypes of people who were not from Burgos but coincided with the previous ones or were at 1–2 mutation steps (

Figure 4). Haplotypes that were within one or two mutational steps were also included.

Among the samples whose origin was Burgos, three haplogroups were identified: R1b, E1b1b-M81, and G. Regarding haplogroup G, there was only one individual with that haplogroup among all the samples from Castilla. In the case of the E1b1b-M81 haplogroup, the obtained haplogroup coincides with the one that corresponds to all Castilla, since 7 out of the 14 samples come from South Burgos.

Regarding the R1b-M269 haplogroup, 34 individuals were included. Practically, all the haplotypes whose origin is Salamanca and Avila are integrated into the network, seven out of eight in both cases. It is observed that the samples that correspond to individuals from Burgos are grouped into four clusters located in remote positions in the network (

Figure 4). The clusters that relate to two of the four clusters fundamentally correspond to individuals from Salamanca. The third cluster constituted a descent cluster of individuals from Avila.

At a comparative level, networks corresponding to the R1b and E-M81 haplogroups with haplotypes from Spain were built (

Figure 5). In network R1b, a majority cluster was identified. The descent cluster was integrated into 54% of the R1b haplotypes. Similarly, the network obtained in the E-M81 haplogroup presented a figure identical to that of Castilla, although with a lower number of haplotypes. In the series from Spain, six E-M81 haplotypes were identified, and in the case of Castilla, 14 E-M81.

The ages of the clusters corresponding to haplogroups E1b1b-M81 and R1b-M269 were calculated. A cluster with a greater number of individuals was considered an ancestral cluster (

Table 2).

Regarding the E1b1b-M81 haplogroup, where all haplotypes have been included, a relatively young date has been obtained, 323+/− 255 years CE. In the case of the R1b-M269 haplogroup, when considering the descent cluster that includes a greater number of individuals, an older age was obtained, 1507+/− 462 years CE. In the network of

Figure 4, corresponding to the individuals from Burgos, and the haplotypes of other origins coinciding with them, or of one or two mutation steps, one large descent cluster was obtained that grouped most of the individuals (31 individuals) and a much smaller one (5 individuals). Regarding the largest descent cluster, the age obtained was slightly younger than that of general R1b, 1411+/− 533 years CE. The minor descending cluster is much younger, 452+/− 320 years CE. If we consider the standard deviation, all descended clusters score older than the established hereditary surnames in Spain.

3. Discussion

3.1. Castilla Surname, Other Spanish Surnames, and Spanish Population

Haplotypes and haplogroups of 102 Castilla Y chromosomes were identified. Due to the low mutation rate of SNPs, it is very improbable that individuals with the same surname and paternal lineage present mutations in the SNPs and yield different haplogroups during the short period after the introduction of surnames. However, it is possible to find different haplotypes in the same haplogroup with low haplotype diversity because the mutation rates of the STRs were comparatively higher. In the present study, when compared with other surnames with frequencies like the Castilla surname, such as the Spanish surnames Juarez or Marques (

Figure 1a), the Castilla surname presents a similar pattern (Spearman’s ρ = 0.010, P = 0.879); therefore, when the number of surname bearers increases, HD increases (

Figure 1a,

Table 1). When compared with Castilla from different geographical origins, when the number of bearers of the surname increases, the HMP decreases (

Figure 1b). That is, the frequency of bearers of the surname is decisive in establishing the degree of co-ancestry, as has already been observed in other studies (

King and Jobling 2009;

Solé-Morata et al. 2015;

Martínez-Cadenas et al. 2016). Surnames with many bearers present many different haplotypes and haplogroups that behave like samples collected from a general population of a specific geographic origin. Although the opposite effect has been observed in the Irish population (

McEvoy and Bradley 2006), this relationship has not been observed in Andalusian surnames (

Calderón et al. 2015).

When comparing the Castilla series with the general series for Spain, it was observed that the HD is similar. However, the Castilla samples had a higher percentage of shared haplotypes. This is consistent with the bottleneck effect when the Castilla surname appears. In addition, the presence of haplotypes belonging to distant haplogroups within the Castilla sample seems to suggest a polyphyletic origin of the surname Castilla. These two scenarios do not exclude the existence of a principal founder haplogroup of the surname, to which other haplogroups are later incorporated as Castilla.

3.2. Founding Haplotypes

The descent clusters identified in the networks were analyzed to identify the founding haplotypes/haplogroups (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). A conventional approach is to consider the most frequent haplogroup in the surname to be the founder lineage. In this case, haplogroups R1b and E1b1b-M81 would be the founding haplogroups. However, other haplogroups, now at low frequencies, cannot be discarded as founders, given that very dramatic and unknown demographic events could have happened in the past.

When the frequency of the R1b haplogroup was compared between Castilla men (0.461) and the Spanish general population (0.601), the obtained values were almost equal (

p = 0.085). The TMRCA calculated for the cluster descent of the R1b haplogroup (1507+/− 462 years CE) seemed to indicate that the use of surnames began long before their mandatory use. Thus, there are sources that report its use in the 9th or 10th century, but at the same time, consider that it was something exceptional. These results raise the possibility that it is more common than previously thought. Nevertheless, it cannot be forgotten that the defined cluster descent depends on the criteria defined by the researcher, in this case, up to two steps. In addition, the mutation rate used (one mutation every 1130 years) favored a greater age of the cluster. A more frequent mutation rate or a more restricted criteria, only haplotypes at 1 step, would give younger clusters. Therefore, these results are compatible with clusters established after obligatory use of the surnames. In the studies of Catalan and Colom surnames, faster mutation rates were used: one mutation every 777 years and every 600 years, respectively. In both cases, TMRCAs were closer to the mandatory period of the surnames. However, when considering the number of haplotypes as a criterion to consider the founder cluster, it can only be assessed as the minimum number of founders. In the simulations carried out by

King and Jobling (

2009), they found that the chance of survival of a lineage from one founder after 20 generations was 9.6%. Because of drift, many founder haplotypes have been lost and do not reach the present. Finally, the possibility of overestimating age should be indicated, as haplotypes of different subhaplogroups may be considered.

The fact that one of the most frequent haplogroups in Castilla is also the most frequent in the Spanish population makes it difficult to establish this haplogroup as the founder of the surname. The networks obtained for the R1b haplogroup in the Castilla and Spaniards groups indicate that with the present results, it is not possible to determine whether this haplogroup is the founding haplotype/haplogroup of the surname. Other studies of the Spanish general population (

Martínez-Cadenas et al. 2016) and Catalan surnames (

Solé-Morata et al. 2015) seem to be able to define a minimum number of founders in infrequent surnames, although not in Andalusian surnames, where there is a low correlation between surnames and Y chromosome markers (

Calderón et al. 2015) or Italian surnames (

Boattini et al. 2021).

Furthermore, it is known that introgression estimates in other surnames of haplotypes whose coincidence is due to state and not ancestry are between 1–3.4% (

King and Jobling 2009;

Solé-Morata et al. 2015). These rates have been calculated in surnames with low frequencies or those located in a very defined local area. Although this is not the case for the Castilla surname, the results obtained in the R1b haplogroup for the frequent Castilla surname indicate a larger introgression rate.

A special case is the Castilla E1b1b-M81. This haplogroup had higher frequencies in Castilla (13.9%) than that in the Spanish population (4.1%), with a statistically significant difference (

p = 0.005). In addition, this haplogroup presented higher frequencies among the populations of North Africa. This most recent TMRCA (323+/− 255 years CE) could be compatible with the obligation to use surnames, but it would also be compatible with the expulsion of both Jewish and Islamic populations from Spain at the end of the 15th century. Data indicate that those people who wanted to avoid expulsion changed their surnames to more Christian surnames (

Obradó 2006). The very compact descent cluster, with very low haplotype diversity, together with the high frequency of this haplogroup in Castilla, seems to suggest the acquisition of the surname of males whose origin was not Iberian.

3.3. Geographical Hypothesis

When analyzing the samples from Burgos, because the information provided by the analysis of the genealogical trees suggests Burgos as the possible origin, four different haplotypes were obtained with respect to the R1b haplogroup. Two of these four haplotypes differed in two ways. In the network shown in

Figure 2, other haplotypes identical to these four and also those 1–2 steps away were all incorporated, despite having a different origin outside Burgos. Thus, it is observed that a connection is established with three out of the four haplotypes, from those Castilla, whose origin is in Salamanca and Avila, regions that are between 240–265 km away. The incorporation of these haplotypes allows the haplotypes of northern Burgos (Rubena) to move to those from the south (Vadocondes). Again, the TMRCA of the majority-descent cluster presents a value that precedes the introduction of surnames.

In relation to the E1b haplogroup, it was observed that all Castillas with this Burgos haplogroup were from the south.

In general, it can be indicated how a greater diversity of haplogroups and/or haplotypes is observed in the Castillas of southern Burgos than in the Castillas of northern Burgos, which all carry the same haplotype and haplogroup.

3.4. Surname Castilla and Castilla Kingdom

An important difficulty in the study of this surname is its idiosyncrasy. Castilla refers to a large region of Spain, to a historical kingdom, and is therefore an obvious toponymic surname for the time being. On the other hand, its relationship with royalty allowed genealogists to assume that its use was uncommon.

Different genealogical studies suggest that during the Middle Ages, family names were used more than surnames. The family name refers to a family, whereas the surname serves to differentiate individuals according to them belonging to a family (

de Salazar y Acha 1991). For example, the family of the Count of Trastámara was known as the Trastámara, although none of them had the last name Trastámara. During the Reconquest of Spain, many Castilla-Leonese men participated in the repopulation of the rest of the peninsula.

Calderón et al. (

2015) found that the majority of their samples from Andalucia had the Castillian-Leonese surname. Therefore, it would not be strange that people from the kingdom of Castilla acquire the surname “de Castilla” to indicate their origin.

The studies carried out in the documentary sources suggest that the family name has been widely used since the Middle Ages, and it is still used in towns in Spain. These studies suggest that until the Council of Trento (1545–1563), there were many changes in surnames for different reasons (

Salinero and Testón 2010). Sometimes, it was because the last name only passed to the eldest son, in other cases, as a way of indicating the geographical origin (from the region of Castilla), for economic interests or social importance, etc.

Ryskamp (

2012) considers a “circular pedigree model”, where the individual could receive his/her surname from any of his/her relatives, even from those who were several generations away, for example, a grandmother or a grandfather.

According to these studies, it would be very difficult to find some type of relationship between a surname and Y-chromosome haplotype/haplogroup. The analysis of SNPs that allow the subtyping of haplogroups may be of interest in those surnames that have a lower frequency and a lower diversity of haplogroups. RM markers can lead, however, to an individualization of each sample, thus blurring any genetic relation among haplotypes. On the one hand, this would explain the great diversity of haplogroups found among Castilla. In addition, the effect of genetic drift and/or introgression, either due to coincidence by state, non-paternity, and other reasons, must be considered.