1. Introduction

The social representations of mixed racial and ethnic identities around the world vary widely, and provide a fascinating window into contextually specific understandings of what it means to be mixed. As a theoretical lens, social representations allow us to study how “everyday” explanations and understandings come to be, a way for researchers to explore the constructions and histories behind the taken-for-granted aspects of social groupings, interactions and meanings (

Aspinall 2015;

Lorenzi-Cioldi and Clémence 2010). “Mixedness”, as describing mixed racial and ethnic identity, presents a key case study into the way meanings are ascribed and constructed, both individually and socially, and how these meanings shape and change identities.

As a scaffolding for both social action and analysis, social representations theory helps to make sense of social structures and relations (

Jodelet 1991;

Howarth 2002,

2006). While not simple to define (see

Howarth 2006), social representations can be seen as “…images that condense manifold meanings that allow people to interpret what is happening; categories which serve to classify circumstances, phenomena and individuals with whom we deal, theories which permit us to establish facts about them” (

Jodelet 1991, p. 14). Representations thus intertwine across micro and macro levels, reflecting and creating what we perceive as real: a way of understanding our world. However, social representations are not straightforward or uncontested. The tensions within and between representations mean that “[i]t is not that social representations simply reflect or inform our reality, but that in doing so they become what reality is inter-subjectively agreed to be. What is critically significant here is that different representations compete in their claims to reality, and so defend, limit and exclude other realities” (

Howarth 2006, p. 69). The multiplicity and dissonances inherent in social representations theory thus lend themselves to research into mixedness and mixed racial/ethnic identities. Questions of mixedness and belonging, a sense of community, identity negotiation and boundary crossing can be illuminated by such a scaffolding.

This paper explores the interactions between historical and contemporary state representations of mixedness and popular representations of Eurasians as a mixed racial/ethnic group in the diverse and racialized context of Singapore. By tracing the genealogy of Eurasian identity, it contributes to the theoretical development around social representations of mixedness, and how the constructed realities of singular and/or mixed identities interact and develop over time and across space. Social representations theory provides us with a unique way to approach what it means to be mixed, unravelling how social (and cultural) representations of mixedness have come to constitute the reality of claiming and existing within a mixed identity in the contemporary world.

Singapore’s history of British colonialism, and the long history of migration and intermixing that predates this colonialism, have powerful impacts on contemporary representations of belonging and mixedness. The nation’s colonial history and post-colonial state development provide a crucial context and “symbolic resources for the positioning of identity” (

Liu et al. 2002, p. 5). Mixedness is most commonly understood in Singapore through the lens of the Eurasian community, historically seen as the intersection of the colonizer and the colonized (

Stoler 1991). As a multigenerationally mixed and complex community, a consideration of Eurasian identity highlights the overlaps and dissonances between colonial and post-colonial identities, histories of migration, and current understandings of what it means to be mixed. The Eurasian community challenges the state narrative of the Chinese, Malay, Indian and Other (CMIO) racial framework, a largely hegemonic representation (

Moscovici 1988) shared by the majority of the population and which is central to the carefully constructed and portrayed symbolism and tradition defining the nation-state (

Liu et al. 2002). Each CMIO group is officially sanctioned and promoted by the state, and race is assigned at birth (historically along patrilineal lines), with ethnic boundary crossing not easily recognized in heritage, representation, categorization and identification (

Chua 2003). Within this state-sanctioned multiracial framework based around singular, bounded racial identifications (

Benjamin 1976;

Chua 1995;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019), Eurasian identity, and the mixedness it represents, remain difficult to pigeonhole.

Eurasian identity in Singapore, and how it has changed against colonial and post-colonial backgrounds, is thus a particularly useful case study in analyzing social representations of mixedness. Crucially, this paper explores the representations of mixedness through changing terminology, from self-identification and popular social labels through to official and state-sanctioned bounding of communities. Tracing developments in terminology highlights how groups can be created, defined and delimited, and how “Eurasian” has been understood in different ways (and to different ends) over time. Stereotypes and genealogies of stereotypical representations are linked to these developments, as the position of the Eurasian community has shifted in the Singaporean context. This paper draws out these contrasting, and sometimes overlapping, personal, social, institutional and state representations of Eurasian-ness, looking at how these representations provide a window into the construction of mixedness against a singularly racialized state background.

Exploring how mixedness is defined and bounded, the paper highlights the practical role played by the Eurasian Association, the administrative body for the Eurasian community and an organization with significant definitional power in mediating between the state and the Eurasian community. This paper brings together a combination of historical literature and research on the history of the Eurasian community in Singapore and the development of the Eurasian Association with a series of 30 detailed, narrative interviews with Eurasian individuals. These 30 interviews were conducted as part of a 2017 research project on ‘Changing Ethnicities’, which explored personal narratives of mixedness for self-identified Eurasians: involving 30 participants across three generations, ranging from 20 to 80 years old, with roughly equal numbers of male and female participants. It is interesting to note that more male than female participants spoke at length about the Eurasian Association and definitions of Eurasian identity, and this is reflected in the quotes used in this paper. Potentially, this difference relates to the historical definition of race in Singapore along patrilineal lines, and the colonial history of male membership in associations such as the EA. Reflecting the centrality of the EA in everyday life, the Association was a key contact point for research, and participants were recruited through convenience sampling techniques, while also snowballing beyond EA members to reach a more diverse population of Eurasians.

The interviews themselves were in-depth, lasting up to two hours, and designed to elicit detailed narratives around their lives and identities, and allowing for interviewees to direct the line of questioning. Interviews covered a range of topics: from family histories and personal feelings of identity, to representations of mixedness in present-day Singapore. Interviewees were able to direct the line of questioning, bringing up what they felt was most salient in their life experiences. Some of the interviewers were from mixed backgrounds themselves, and this was frequently discussed within the interviews as a point of commonality, openly positioning the research and the researchers. These interviews provided a valuable source of data, illustrating how state, social and individual representations of mixedness interact to (re)create different versions of reality, and how/where these representations overlap and diverge. Quotations from the interviews have been used throughout the paper to illustrate key theoretical points, with some providing unique and selective points of view, and others used as examples of wider community sentiments.

After a selective review of social representations theory as applied to mixedness in the next section, the paper turns to the complex genealogy of the term “Eurasian” as a social category of mixed identity in Singapore. Questions of exclusion and belonging are then followed up in a discussion of the Eurasian Association, and its dual role as a community group and an agent of the state, drawing together state and social representations of identity. The penultimate section of the paper examines some of the contradictions and dilemmas confronting the Eurasian community in conforming to Singapore’s racially structured identity framework, with the concluding section summing up our key arguments on the social representations of mixedness.

2. Theoretical Background: Social Representations of Mixedness

The social representations of mixedness provide a fruitful area for research, inviting practical engagement and analysis, rather than simple description of the complexities within racial and ethnic identities and identifications around the world (see

Moscovici 1988;

Howarth 2006). This approach highlights how the social order can be both created and questioned by differing representations of the same phenomena, and how mixedness itself can be conceptualized and redefined in different ways. Social representation, as a socio-cognitive practice (

Jodelet 1991), highlights the linkages between macro and micro levels of perception. Representations allow individuals, groups and states to create and utilize frameworks of understanding, linked to versions of social reality that fit with particular perspectives around belonging (

Howarth 2006).

At the level of the state, hierarchies of power are key in determining which narratives and representations become dominant. Such hegemonic social representations gather particular strength and have an important impact on “reality”—that is, they “not only influence people’s daily practices—but constitute these practices” (

Howarth 2006, p. 74). In Singapore, clear state narratives around racial belonging, as defined by the CMIO groupings, highlight how this particular social representation of race and racial belonging constitutes the “reality” of race. Racial singularity is accepted as an accurate representation of reality, and this social construction reinforces and maintains relations of power in the social order, while naturalizing this particular racial narrative (Augoustinos and Walker 1995; cited in

Howarth 2006).

Moving to the individual level, Stuart Hall’s interest in representations of racial and ethnic identity led him to focus on cultural representations and negotiations, and how identity is shaped by representations of race, ethnicity and gender: “both ascribing meaning and constructing meaning, which in turn shapes human identity” (

Aspinall 2015, p. 1070). Hall highlights how representations do not only describe reality, but in fact establish what is real, connecting meaning and language to culture (

Hall 1997). This emphasis on cultural representations allows us to situate identity at the center of the analysis, with identities seen as constructed through discourse, and situated within particular cultural contexts and time periods (

Hall 1996a). Mixed identities are no exception. With studies of mixed ethnic and racial identity pushing at the borders of sociological theory around race, ethnicity and belonging, analyzing cultural representations of mixedness allows us to unpick the personal, social, political and historical aspects of mixed identities, and communities based around mixedness.

Hall (

1990,

1992) further explores this complex relationship between the narratives of the nation and the social representations of identities. According to

Hall (

1992, p. 293), there exists a “narrative of the nation, as it is told and retold in national histories, literatures, the media and popular culture… we see ourselves in our mind’s eye sharing in this narrative”. Hall refocuses the emphasis of social representations on identities, and the cultural embedding of these identities, which intersect with social boundaries (

Hall 1992). In this sense, identities, and particularly mixed ethnic/racial identities are never simplistic or final, but rather continuously (re-)constituted within cultural representations of what it means to belong (

Hall 1990). Genealogies (of mixedness in this case) can then provide a useful way to move past essentialist ideas of race, ethnicity and belonging (

Hall 1992;

Tyler 2005). Representations of mixedness as an identity are always changing, juxtaposed against the background of contextual history and the shifting narratives of past and present, while interacting with state representations of mixedness and racial singularity in Singapore.

Crucially, representations at macro and micro levels have tangible structures and consequences, and particularly so for the tangled issues around race and belonging (

Hall 1996b). As described by Aspinall, identity, categorization and representation are closely intertwined: “All ethnic/racial terminology may be seen as a form of representation, whereby meanings are generated by a range of social categorizers in settings of popular culture, political discourse, and statistical governmentality” (

Aspinall 2020, p. 1). The singular racial framework in Singapore highlights the power of this hegemonic representation and categorization, and limits the options around racial identification in the Singaporean context. As

Howarth (

2002) finds in other contexts, categorization is not always optional, and may be imposed on a person or a group: (mixed) racial and ethnic identities are constructed through and against representations, highlighting the possibility of dissonance between how we see ourselves, how others see us, and in this case, how the state chooses to classify us (see

Howarth 2002).

Terminology and the history of terminology are closely related to the structures and reach of systems of categorization. Terminology plays a key role in representations of identity, reflecting dominant and minority labels, and the ways in which a single group can have multiple names. This complexity illustrates the complicated lived experiences of mixed (and all) identities, and the ways in which labels function to give voice to different representations of reality. Terminology may not always match across representations, however, giving rise to possibilities for disagreement and mislabeling between self-descriptors and external categorizations (

Aspinall 2020). Mixedness in Singapore provides an important example of terminology creating a “new” ethnic group/category of Eurasian, but also highlights how singular terminology masks mixedness to a significant degree, hidden behind the single races of the CMIO framework. As in Aspinall’s 2015 UK study, the representations of mixedness in the Singaporean context highlight the breaks between state and individual understandings of being mixed, with the shared social reality underpinned by dominant representations which are “strongly connected to processes of stereotyping, loaded with preferences, and aligned with positive or negative ‘naturalized’ characteristics” (

Aspinall 2015, p. 1080).

3. Shifting Representations of Eurasian Identity in Singapore

Social representations of mixedness in Singapore center around the complex genealogy of the term “Eurasian”. The social and cultural significance of this term has changed over time, and the boundaries of Eurasianness have expanded and contracted across colonial and post-colonial timelines, carrying echoes of individual and collective histories (see

Howarth 2006). Race is a key point of representation in contemporary Singapore, with the CMIO framework as a well-accepted and historically grounded framework for making sense of diversity, both at state and social levels. Race is a key identifier, a quotidian identity marker in the Singaporean context, not just implicitly and socially, but openly and institutionally. Race is noted on identity cards, medical records and school registrations, classified in the national census, mentioned in apartment rental listings, and frequently brought up in everyday discussions (

Rocha and Yeoh 2019;

PuruShotam 1998;

Rocha 2016;

Siddique 1990). Against this racialized scaffolding, identifying as Eurasian has historically fallen into the “Other” category, alongside Peranakan and other groups which do not fit neatly into Chinese, Malay or Indian. Mixed identities are therefore not allocated named institutional space within the CMIO framework. This has had important social and administrative consequences for the Eurasian community, given the far-reaching nature of the CMIO framework in terms of population management and social policy.

There are many key examples which illustrate the reach and power of the CMIO categories in daily life, from languages taught at school and eligibility for public housing to social welfare. In terms of the latter, as the Singaporean state does not provide universal social welfare, organizations known as community “self-help” groups have been designated the task of providing welfare assistance. These groups are structured along CMIO racial lines, based on the premise that each separate racial group has issues, priorities and needs that are best addressed by their “racial peers” (

Kong and Yeoh 2003). Each of the main CMIO categories thus has a corresponding self-help group: the CDAC (the Chinese Development Assistance Council), MENDAKI (

Majlis Pendidikan Anak-Anak Islam), SINDA (the Singapore Indian Development Agency) (

Chua 1998;

Lai 1995), and more recently, the Eurasian Association (EA) for the Eurasians within the “Other” grouping (

Pereira 1997,

2017;

Rocha 2011). These groups act a social safety net for each racial group, providing financial and social assistance, and are funded by the community through opt-out tax contributions as well as through government assistance. Unusually, racial identification in Singapore therefore determines the organization to which an individual could apply for social assistance.

The multiracial framework is thus central to institutional, organizational and social life in Singapore (see

Hill and Lian 1995). It is unusual for a citizen to be thought of as “just” Singaporean: within this system, race provides an additional qualifier, creating complex civic-racial identities, such as Singaporean Chinese (

Chua 2003;

Barr and Skrbis 2008). However, given Singapore’s status as a desirable country for immigration, growing levels of migration and intermarriage have meant that this singular racial system has become increasingly strained. As a concession to this growing diversity at the level of the state, from 2011, children of mixed heritage were provided the option of registering at birth as having a ‘double-barrelled race’, such as Chinese-Indian, in addition to the more general option of “Eurasian”. However, to prevent disruption to the CMIO framework and any practical advantages that could come from identifying with two races, it was also specified that all individuals must also select a primary race—the race before the hyphen (

Rocha 2014) (Statistics are not currently available for numbers of individuals who are registered with double-barrelled races.). Mixedness is thus officially acknowledged, but cannot be operationalized to make use of multiple racial identifications within Singapore’s singular racial framework.

The shifting state and social representations of the Eurasian community complicate the dynamics of how mixedness came to define an ethnic group, and the hierarchies and distinctions that exist within these varied representations. The distinctions within “Eurasian” illustrate the peculiar positioning of a mixed community which was defined and bounded under colonial rule, and the colonial/post-colonial continuities and breaks in terms of what is valued and what is hidden when it comes to mixed identities. This has important implications in the Singaporean context, with high levels of immigration and cross-cultural marriage and partnering—with over 20% of all marriages in Singapore now classified as inter-ethnic (

Singapore Department of Statistics 2015). In this context, shifting representations of Eurasian identity in Singapore highlight, in particular, the complexities of mixedness across generations. While much of the rapidly increasing body of literature on mixed race identities around the world explores mixedness across a single generation (based on parents of different racial groups), Eurasian identity in Singapore illustrates how being mixed can be multigenerational, encompassing varying types and understandings of hybridity, while drawing together colonial resonances of belonging with contemporary forms of nation building (see

Yeoh et al. 2019;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019).

The Eurasian population includes those who have a mix of European (often Dutch, Portuguese and British) and Asian ancestry, with a long history in Singapore prior to British colonial rule (

Braga-Blake 1992;

Rappa 2000;

Yeoh et al. 2019). Under the British, the population increased through both migration and intermixing between the colonizers and the colonized, and the community found itself positioned in between ethnic groups, in terms of education, occupation and socio-economic class (

Braga-Blake 1992;

Pereira 1997). Associations with European heritage bestowed a level of privilege on the population, although this declined after the mid-1860s, as the European population increased and race/class lines were more firmly established (

Braga-Blake 1992;

Rocha 2011).

The term Eurasian in the Singaporean context then literally refers to those of mixed European and Asian origin, or in geographical terms, where Europe joins Asia (

Braga-Blake 1992;

Siddique 1989). However, its everyday meanings change over time and space: with gendered implications under colonial rule, most frequently referring to the children of European fathers and Asian mothers; having different histories and definitions in India, Myanmar, Malaysia and Singapore; and in contemporary Singapore, describing both those with historical mixed ancestry

and the children of one Asian and one European parent (

Matthews 2007;

Rappa 2000;

Rocha 2011) (Unlike in other contexts, “Eurasian” in contemporary Singapore is not pejorative and is widely accepted as a racial group.). These ideas of both division and mixture highlight the colonial, top-down origins of the term, with significant diversity and difference being bundled into a broad, all-encompassing label for administrative convenience (much like “Other”, as in

Anderson 1991).

Participants in this study often spoke about the term Eurasian and its various meanings, for them on a personal level, and what the term represents in wider Singaporean society. One participant described the contemporary community as “amorphous”, illustrating the links between heritage, phenotype and assumed race:

As you know, the Eurasian community is quite amorphous. There are Eurasians of various descents. In terms of skin tone, some are fair, darker, others are more fair, fairer ones tend to be misidentified as being European...

(Gene, male, 40) (All names are pseudonyms.)

The Eurasian community and their identifications in Singapore remain under-researched areas (

Lowe and Mac an Ghaill 2015;

Rappa 2016): they are a numerically small, historically prominent, yet frequently overlooked group based around mixedness. Eurasians are often described as quintessentially Singaporean by Eurasians themselves, in terms of their boundary crossing, hybrid cultural practices and historical links to Singapore, yet they are not administratively easy to locate in contemporary Singapore (

Ackermann 1997;

Braga-Blake 1992). Within the CMIO framework of hyphenated civic-racial identities, Eurasians are recognized as a fixed, defined group (of mixed European and Asian origin, rather than necessarily parentage), yet also subsumed under the amorphous “Others” (

Siddique 1990;

Hill and Lian 1995;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019). Despite official recognition, social representations are another story, with mixedness not always seen as a legitimate representation of identity within popular understandings of the CMIO framework:

[I was] trying to navigate or try to find my place in this whole Singapore country, like when we started and I was young and I was mixed and I was like going to school with people who were pure Chinese and pure Indians and pure Malays and I was the only kid on the block who was… I was just like what the hell am I and who the hell am I?

(Pamela, female, 20s)

However, in practice, the definition of Eurasian retains some flexibility: from the perspectives of those being labelled (individuals of mixed heritage who can choose whether or not to identify with Eurasian, or with one of the other categories in their heritage), and those doing the labelling: as described by

Braga-Blake (

1992), final decisions about unclear categories are often dependent on the mood of the administrator on duty. Increasingly blurred boundaries mean that categorization of mixedness can be complex, at individual and institutional levels:

I guess for the majority races it’s very easy to sort of delineate the boundaries, right? But as you move towards the peripheries it gets harder and harder to say where’s the boundary, is there a boundary? Um, I have friends who have like, a Malay father and a Chinese mother, and the Chinese mother had an Indian father—so what is that, right? You ask Singaporeans. Let’s not try so hard.

(Kenneth, male, 24)

The mixed heritage of the Eurasian community thus illuminates the different representations of mixing within mixedness, new and old, visible and invisible, which make up the community today.

4. Defining and Representing Identity: The Eurasian Association

The Eurasian Association (EA) plays a key role in defining and representing Eurasian identities and interests in Singapore. Membership of the EA does not always correlate with Eurasian ancestry, which in turn does not necessarily lead to personal identification as Eurasian: not all those who are members are recognized as Eurasian by the community, while many of those who qualify as Eurasians choose not to become members. As described by

Siddique (

1990), the institutionalization of ethnicity has led to a heightened racial awareness in the Singaporean context. Racially based organizations, such as the EA, are important in underpinning this awareness: acting as state-sanctioned community regulators of hyphenated racial-Singaporean identities through definition, boundary-making and providing a place to belong.

Racialized belonging in community organizations first developed under British colonial rule, with groups being allocated physical and social space along racial and strictly hierarchical lines, creating and reproducing a defined colonial order of things (

Stoler 1995). For the Eurasians, a growing sense of separation from the ruling European class led them to consolidate as a distinct community, forming specifically Eurasian associations and clubs. The largest of these were the Singapore Recreation Club, the EA, the Girls’ Sports Club and the Singapore Volunteer Corps (

Barth 2017).

The EA itself was formed in 1919, growing out of what was the Eurasian Literary Association, and its initial objectives were to promote the interests and advancement of all Eurasian-British subjects, while keeping its members actively interested in the political situation in Malaya (

Barth 2017;

Rappa 2000). Eurasian identity thus became more deliberately defined, with the formation of the EA, seeking to consolidate a community around a particular representation of mixedness and positioned in-between the European and Asian populations, the colonizers and the colonized (

Stoler 1991). Being Eurasian in colonial Singapore was closely associated with key markers of what they saw as unique to the community: being of mixed European/Asian descent, having etymologically European surnames, belonging to the middle class, identifying as Christian and speaking English (

Braga-Blake 1992;

Pereira 1997;

Rocha 2016). Membership in the EA was voluntary and initially social, but the Association’s reach and scope broadened as numbers increased.

Throughout the 1960s, the role and prominence of the EA and the Eurasian community in post-colonial Singapore shifted dramatically once again. With the CMIO categories utilized as a framework to shape and manage the diversity of independent Singapore, Eurasian as an identity lost its privileged status as linked to the former colonizers, and was instead classified under the general category of “Other” (

Pereira 1997;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019). Social, cultural and economic markers which had previously been seen as unique became more general features within the Singaporean population, and identifying as Eurasian meant exclusion from representations of belonging in Singapore, centered on the Chinese, Malay and Indian populations (

Pereira 1997,

2006;

Rocha 2016;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019). The size of the community and the numbers of those choosing to identify as Eurasian had been declining from World War II onwards due to a variety of social and economic factors. Many Eurasians left Singapore from the 1940s to the 1980s, seeking better opportunities post-war and within the new independent nation, while others chose to identify instead with one of the major racial groups in the newly independent nation, reshaping representations of mixedness into singularity. Reflecting this, membership of the EA fell from 770 prior to the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1942, to 400 in 1963, continuing to decline in post-colonial Singapore to only 240 in 1988 (

Barth 2017;

Braga-Blake 1992).

By the 1980s, the Eurasian community, and the mixedness it encompassed, were all but rendered invisible in the multiracial Singaporean nation. The community remained conspicuously absent from the racialized representations of nationhood portrayed by the state, with hybrid roots not fitting easily into the multiracial model, and the European roots of Eurasian identity seen as distant from the resurgent Asian values of the country (

Pereira 1997,

2006;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019). The EA fell out of favor, seen as not relevant to the new nation, or to the younger generation of Eurasians. However, in the latter half of the decade, a small but vocal group sought to re-establish Eurasian identity, using the EA as way to consolidate the community, to promote representations of mixedness as a legitimate identity claim, and to establish Eurasian as recognized “race” at the government level. By 1989, aggressive campaigning and publicity resulted in an increased membership of 800, rising to 1300 by 1992 (

Barth 2017).

The community, led by the Association, began a process of re-representation, revitalization and resurgence, by formalizing and promoting a distinctly “Eurasian” culture, and by transforming the EA into the “self-help” (social welfare) group for the community, and thus the official representative institution of the Eurasian “racial” group (

Pereira 2017). To fit more easily into the CMIO framework as an established and unique racial group, Eurasian identity needed to be more clearly conceptualized: to be an official race, there needed to be an official language, religion, cuisine and culture. A unique mélange of characteristics was chosen to make up this new representation of authentic mixedness—drawn from local history, borrowed from other groups in the region and even invented to fit the new narrative of belonging. Selecting which forms of mixedness to include and which to overlook, the EA made a break from their colonial history, and opted to promote aspects which were largely linked to Portuguese (rather than British) heritages:

Kristang (a patois of Portuguese and Malay originating in Malacca), the

branyo (a traditional dance), Catholicism, and foods such as

sugee and devil’s curry (

Pereira 1997,

2006;

Rocha 2011). One participant highlighted this bricolage of identity, and how difficult it is to create something distinct from hybrid roots:

Maybe that’s what Eurasian means: everything is kind of like, a bit similar to what other people do, but different.

(Molly, female, 22)

Parallel to this cultural distillation and consolidation, the EA assumed institutional prominence as a result of its shift to fit as a community “self-help” group. The Eurasian Community Fund was set up in 1994, and the EA was accorded official community self-help group status, to act on behalf of the Eurasian community (

Pereira 2006,

2017). The reach of the EA extends far beyond that of the other self-help groups however, as its mandate includes both welfare and cultural functions: providing social assistance and “…community development, maintaining and promoting Eurasian culture, as well as representing the community at national levels” (

Pereira 2017, p. 388). Importantly, through this recognition, the government officially accepted the organizing role of the EA, and allowed the Eurasian community official space as a self-defined racial group in multiracial Singapore—as a named, legitimate group with state recognition. (

Pereira 1997;

Rocha 2011). More concessions were made as Eurasian identity became more widely acknowledged, including allowing “Eurasian” as an option on national identity cards, providing cultural representation in national events such as the National Day Parade, and in 2003, the opening of the government-subsidized Eurasian Community House, where the EA now operates (

Pereira 2017).

As a community group, the EA has shifted from a small-scale social club, to the official curator of representations of Eurasian culture in Singapore. With over 2000 current members, the Association has been highly successful in promoting, and in some cases, (re)creating and representing what it means to be Eurasian within the multiracial framework (

Pereira 2017). For some in the community, this role is a source of great pride: “It has rekindled among Singapore Eurasians a sense of pride in their uniqueness and a desire to preserve their cultural identity. The fact that we can call ourselves Eurasians once again and are no longer assigned to that nebulous group of “Others” is symbolic of the importance that Eurasians place on being perceived and accepted as a small but significant component of Singapore’s multi-ethnic community” (

Barth 2017, p. 157).

5. Social Representations of Mixedness: Divisions and Dissonance in the Eurasian Community

The Eurasian community in Singapore is particularly diverse, both along generational (old and new) lines, and in terms of the inclusion of a wide range of cultures and heritages. In (re)defining what it meant to be Eurasian, the EA relied on the distinctive nature of Portuguese representations, simplifying much complexity into a simpler “mixed” package and reinforcing a particular version of mixedness (

Pereira 1997,

2006;

Lowe and Mac an Ghaill 2015). This definitional choice was itself underpinned by colonial hierarchies and valuations of mixedness in Southeast Asia. The Eurasian community in Singapore has historically been divided into hierarchies based on heritage, race and notions of “better” forms of mixedness, and participants in this study echoed how these divisions have carried over into independent Singapore, and are still very much felt today.

Across Southeast Asia, shifts in understandings around mixedness and Eurasian identity highlight parallel colonial histories and post-colonial changes. Interesting links can be seen between Singapore and Malaysia, as representations of “true” Eurasian identities shifted and were valued differently over time. In Malacca, the early twentieth century colonial Eurasian population had similar social characteristics to that of Singapore. Part of the Straits Settlements under British colonial rule, Eurasians were positioned in-between the colonizer and the colonized, and British heritage and custom were highly valued. The Eurasian community was divided into two distinct groups: “Eurasians”, or “Upper Tens”, were upper class, well-educated and employed in civil service; and the “Portuguese”, or “Lower Six”, were lower class and often illiterate, frequently working as fishermen (

Sarkassian 1997). Interestingly, heritage could be trumped by class, as some families of Portuguese descent chose to distance themselves from the “Portuguese” group, referring to themselves as “Eurasian”, with significant value being placed on lighter skin (ibid.)

In Singapore, a similar hierarchy existed: there were “Eurasians… and EURASIANS” (

Braga-Blake 2017). Under British colonial rule, Eurasians were divided into “Upper Ten”/“Lower Six” groupings as in Malacca, with the terms likely referring to socio-economic status and educational rank (

Braga-Blake 2017;

Rappa 2000). Whatever their origins, the community distinctions were very real, dividing the elite from the lower class in terms of cultural affiliation, employment, socio-economic opportunities and education.

An important cultural shift occurred in Malacca when the Japanese invaded Malaya in 1941, and the British lost their position as colonial rulers. As the British returned in 1945, calls for independence and shifting social currents meant that association with British culture and rule was no longer the powerful asset that it had once been. The Upper Ten population were under threat, and sought to “reinvent” themselves, to find a way of being Eurasian that was not associated with the ex-colonizer. In an interesting turn, the Upper Tens (whether of Portuguese descent or not) chose to associate themselves with the Lower Six population, the Portuguese Eurasians, in a strategic move to define and maintain identity (

Sarkassian 1997):

“The initial embracing of Portuguese folk music and dance by upper-class Eurasians was thus purely strategic. In a pragmatic attempt to disassociate themselves socially and culturally from the British, the Upper Tens found a cultural way to melt, like chameleons, into the non-colonial environment. It was an ideal compromise—a ready-made “tradition” that was recognizably European, but not British. The historical link with Portugal generated status and legitimacy (not to mention adding a certain swashbuckling romance), but did not awaken recent colonial memories. The most distant of all colonial intruders, Portugal was by then little more than a downtrodden second-rate European nation. Finally, it linked them (cosmetically) with a disadvantaged local group, the “Portuguese” fisherfolk.” (

Sarkassian 1997, p. 254).

As

Pereira (

1997,

2006) described for the Singapore context, the Eurasian population deliberately picked and developed customs based on a particular heritage, overturning the class distinctions of the British, and re-creating Eurasian identity as authentically Portuguese. This created a more easily defined group, but excluded other ways to be mixed:

But you know, because Singapore is like kind of categoriz[ing], you’re Chinese means you’re Chinese, you’re Indian means you’re Indian but they don’t see it as, oh I’m from a Northern Indian side, I have different ethnicities, different mixtures. And for the Eurasians, somehow everybody is kind of cuckolded in that whole, like…you know there’s this whole Eurasian culture that stems from part of England, that kind of feel and [also a] Portuguese feel. But the thing is that, Eurasians are so diverse that I may not even have Portuguese in my blood and I still identify as Eurasian because you know, down the lines, I’ve been…my parents, my grandparents have been married to different mixtures, but I don’t necessarily identify as Portuguese?

(Gabriel, male, age unknown)

In both Malacca and in Singapore, markers of Eurasian identity today have created a “traditional” image, based on traditions that never existed, as a way for the community to be accorded recognition and status at an official level. Thus, mixedness can be invented and inherited simultaneously, drawing together ideas of biology, culture, ancestry and heritage (see

Tyler 2005).

As an institution, the EA then functions at individual, community and state levels, in order to create and consolidate a representation of identity which is of practical use in post-colonial Singapore. Official recognition has been paramount in this identity building process, essentializing and making strategic use out of the historical and cultural resources available (

Pereira 2006;

Yeoh et al. 2019). The development of a state-sanctioned Eurasian-ness can be seen as the logical outcome of what

Siddique (

1990) refers to as the “bureaucratization of ethnicity”, where government policy and everyday life identities intertwine to create meanings for multiracialism, and in particular for those racial building blocks which make up the multiracial framework. The institutional re-defining of “Eurasian” illustrates this, as the official EA definition was broadened to include all those with Asian/European heritage, vastly increasing the potential pool of members for the Association, while simultaneously calling into question which “reality” was represented by the label Eurasian (

Pereira 1997;

Choo 2007). One participant commented:

…maybe being Eurasian is actually a mindset. Because I think that there are also, are Eurasian people who trend the other way, you know. Who actually see themselves as not being Eurasian. I know of quite a few, with Eurasian surnames, not even like a half Asian surname like mine. Totally Eurasian surnames, either Portuguese surname or Spanish type surname, Chinese friends throughout their whole life, speak fluent Mandarin or even learned higher Chinese in school, cannot even speak good English sometimes.

(Gene, male, 40)

Previous studies show a divide between traditional and new Eurasians, or “true” Eurasians and “technical” Eurasians (

Rappa 2000), with even the EA acknowledging that more inclusive representations may make ethnic boundaries more difficult to demarcate:

The community can be more disparate and divided than others which are more clearly defined by common cultures, languages or religion. And when a new wave of immigrants means more people of mixed marriages coming into the country, even existing Eurasians might fear being swamped by new additions to the community.

Participants had mixed feelings about the division between “new” and “old” Eurasians, and how they were represented as part of (or apart from) the historical community. One participant felt that first-generation Eurasians should not be included in the community:

Yah we will not identify these. They are Eurasians yes but not our kind of… What we think of Eurasians. Our really born and bred here Eurasians… It’s a lot of mix. Pure Eurasians no more.

(Gavin, male, 62)

Interestingly, Gavin’s understanding of legitimate mixing meant that first-generation Eurasians were excluded: too mixed for a community based upon mixedness. Another participant saw the widening community as an acceptance of reality, but drew out key cleavages within the community itself:

These fairer or New Eurasians, if you like, are here to stay and are part of the social tapestry and by the way, using the word New Eurasians, is a word coined by the Eurasian Association. So, if you go into the newsletters and speeches or whatever documentation you can get out of the Eurasian Association, over the last five years, there’s been this explicit reference to New Eurasians… And the Eurasian Association is now seeking to recruit into the association people with a, first generation Eurasians, if you like, people who have one fully Asian parent and one fully Western parent, who don’t fall into the typical Eurasian mold or being a second or third or fourth generation Eurasian, multi-heritage Eurasian, if you like. So, they’ve identified this new subcategory, if you like. But my experience tells me that they’re not, they don’t know where to place New Eurasians. And the traditional Portuguese Eurasians find it hard to fully accept them as well. Because the core base of the Eurasian Association are still your tanned, dark skinned Portuguese Eurasians. So, having been there, I felt, I felt the fault line of differences, if you like.

(Gene, male, 40)

These sentiments were echoed by a number of participants in this study, who commented on the twin processes of broadening and solidifying definitions for the community. One participant felt that the label of Eurasian had become too inclusive, to the extent of diluting and even eliminating the unique aspects of the culture:

…so the initial drive to broaden the definition of Eurasian was good, but I think they went overboard—they went to the other extreme. The definition itself was lost, so… so while I’m proud to be Eurasian and all that, I do think we’re a dying breed.

(Wayne, male, age unknown)

Gene, quoted earlier, felt that this inclusive representation was merely a symptom of a wider confusion, a more deeply felt lack of clarity in terms of what it means to be Eurasian:

But still, we can’t come to some sort of common position as who we are, we can’t boil it down to a set of first principles as what Eurasian community is. Which is why the Eurasian Association to me is quite messy in that sense. People just can’t come to an agreement. We constantly, whenever we have annual conferences about being Eurasian, we can never come down to any kind of resolution or clarity as to who we are. And we think that’s okay.

(Gene, male, 40)

This lack of resolution was seen as a key weakness, set alongside what he saw as clearly defined, easily bounded Chinese, Malay and Indian communities. Another participant envisaged the community gradually dying out over the years, as a result of this ambiguity and a lack of community will:

That’s what I mean when I say that we have failed the community—because we have not grown the community. The government has given us enough of funds and opportunities, but we still have not grown the community... This race of Eurasians will trickle out, maybe 10, 15 years. This is the issue we’re facing. The whole community just dying off. Not because of genocide but just because we didn’t think hard enough about how to maintain it.

(Victor, male, 61)

In his view, the EA and the community have failed to clearly define and maintain a viable representation of identity within the Singaporean context, despite (or perhaps as a result of) efforts to establish and promote an inclusive form of belonging.

In addition to the Old/New differences, previous research highlights the historical Upper Ten/Lower Six divisions as a curious part of the history of the Eurasians in Singapore, indicating that contemporary representations of mixedness are less contested (see

Braga-Blake 1992;

Rappa 2000). While socio-economic statuses have shifted for much of Singapore, and the associations between occupations, ethnic identities and socio-economic status have become less stark, hierarchies of mixedness continue to exist. In an interesting dichotomy, Portuguese Eurasian identity is firmly institutionalized and reinforced by the EA as authentic, yet British Eurasian identity continues to retain social and cultural value within the community.

One participant in this study described a hierarchy within the community that echoes colonial notions of worth and racialized ranking: a “caste system”, where some representations of Eurasian identity are seen as better than others, and those of lower socio-economic status are excluded from membership of the elite. Another elaborated on the exclusivity of the Upper Tens, illustrating an understanding of Eurasian identity as insular and set apart, and not necessarily connected with the EA’s portrayal of what it means to be Eurasian.

They have the, they call them the Upper Ten Eurasians. That means they’re a bit more snobbish (laughs). And they feel they’re so special, that they only mix around with certain people. So, those are the Eurasians, those are the ones who live away from the rest of the community so they grew up amongst Eurasians and they felt they were so special that the others were all below them. That kind of thing. So, they only mix around with their own Eurasian community group. So, we call them the class-conscious Eurasians, we use the word ‘Upper Ten’, I don’t know why Upper Ten but my dad used to tell me that. So anyway, they…whereas we grew up outside with the other races. We mixed around so we were every comfortable with other races.

(Chad, male, 65)

The colonial perceptions of Eurasians as linked to the British colonizers strongly influenced how they were positioned in terms of race and class in Singapore. This has shifted significantly over time, illustrating the institutional swing back towards Portuguese culture as a marker of Eurasian identity (as in Malacca), and interestingly, the socio-economic assumptions that accompanied this. Eurasians are no longer seen as part of the upper class, reflecting processes of decolonization and the consolidation of power and resources with the Chinese population, as well as shifting valuations of mixedness in post-colonial Singapore.

Thus, while the EA provides official representation for the Eurasian racial group in Singapore, the Association itself does not necessarily represent the diversity of the Eurasian populations within the country.

Rappa (

2000) estimates that less than one-tenth of those who identify themselves as Eurasian or as having Eurasian ancestry are members of the EA, although statistics are not easily obtainable. As found by

Yeoh et al. (

2019), identifying as Eurasian in official documentation does not always translate to membership of the EA, or identification with the carefully curated cultural practices which have come to represent Eurasian-ness. This study also found that while many participants were active in EA activities, a large number also chose not to be involved. For some, it was just a matter of the time pressures and priorities of everyday life:

I’ve got nothing against the EA. It’s just I don’t think I have the time for that kind of—for me it’s just work and my family and church and all that. Previously I was very involved. Yeah. It’s more than enough to keep me busy.

(Brian, male, 54)

For others, the EA was a symbolic figurehead, without a meaningful tie to the community:

The EA has symbolic power. But it doesn’t have—like, you can’t expect the EA to say everyone learn Kristang now, and everybody—nobody’s going to listen to them. They won’t care. So, the EA is becoming “figureheady” I think. They have the money, but I don’t think they have the network.

(Kenneth, male, 24)

The EA was seen by this participant as an abstract institution: overseeing administrative representation, but not capturing the heart of the community, and dispensable to being Eurasian in Singapore.

However, several people had more specific reasons behind their non-participation, describing how the EA’s focus on Portuguese Eurasian identity did not resonate with their own representations of Eurasian-ness, the representations of mixedness which they felt were more important. One interviewee saw this through a religious lens, linking Catholicism, Portuguese heritage and the role of the EA:

But Eurasian Association again is…the problem is that it began very much as a church organization, you know? The Portuguese Eurasians were very Catholic… So, a kind of an elitism, (laughs), divide within what they call the Eurasian community. They saw that they were the sole Eurasians of the day. And I know, it just happened recently, that… within the Eurasian Association, those who are not Portuguese descent, not clicking. They’re not clicking.

(Daniel, male, 80)

Others went further, finding the political role of the EA, and the internal politics around identity definitions and membership to be overwhelming. This participant identified as Eurasian, contributing to the Eurasian self-help group fund, but chooses not to be involved with the EA itself due to the “political wrangling” involved:

Originally, I didn’t join as a member because of this thing [the EA]. And eventually I didn’t feel the need to join. That’s why, ya, so. I don’t identify as Eurasian to them. I don’t know why. But I’ve never had the yearning to go and join them. We get the magazines because we get to contribute because you know, the Eurasian fund, the Indians to SINDA, the Malays to MENDAKI. There’s a lot of political wrangling you can see until today in the Eurasian Association… I don’t feel Eurasian. It’s very political, it’s very—everybody has got the one-upper agenda, somehow.

(Wayne, male, age unknown)

Saying “I don’t feel Eurasian” illustrates how conflicting representations of mixedness exist within the community, and the contradictory position of the EA for some: both representing what it means to be Eurasian politically and culturally, while also drawing boundaries around what counts as authentically Eurasian. The power of state categorization and EA definitions thus had significant impacts on personal feelings of identity and belonging. Nonetheless, the term Eurasian, and membership in the EA, have administrative and welfare benefits which remain attractive to some, illustrating Aspinall’s point that even when communities define themselves differently to external categorizations, they may still choose to use these accepted categories situationally regardless of the extent to which they are personally meaningful (

Aspinall 2020).

I will identify whenever it’s convenient for me. So, I will identify as Chinese if I am hanging out with Chinese people… And it’s convenient, to my advantage, yes, I identify to whichever side based on the situation.

(Charlene, female, 30s)

Most interestingly, parallel processes of identity representations can be seen over the years, as the EA has simultaneously sought to broaden membership while distilling a recognizable (and politically useful) form of identity based around Portuguese heritage. This dual opening up and solidifying of boundaries was particularly prominent in 2011, with the shift to allowing double-barrelled racial identifications on official documents. This change put the label of “Eurasian” in the spotlight, as parents of different races could choose to select single races, hyphenated racial identities

or “Eurasian” for their children, using Eurasian as a synonym for mixedness of all kinds (

Rocha 2014). The EA noted that this would likely increase the numbers of “new” Eurasians in the community, and suggested that cultural dilution could be avoided by reinforcing the existing “traditional” community culture (

Eurasian Association 2010): in effect, passing on an essentialized version of Eurasian culture to all those labelled as Eurasian, regardless of heritage (

Rocha 2011). Many participants spoke of the tension between new and old Eurasian identities as a struggle between old and new representations of the reality of mixedness, with one saying:

So, the new Eurasian thing is sort of the tension, I feel. Because the EA is trying to—the EA wants to have their cake, eat it and then have some more cake and then eat it as well. So they want to grab the Portuguese Eurasians back, they want to hold on to their English and Dutch-ness, and they want the new Eurasians in, right.

(Kenneth, male, 24)

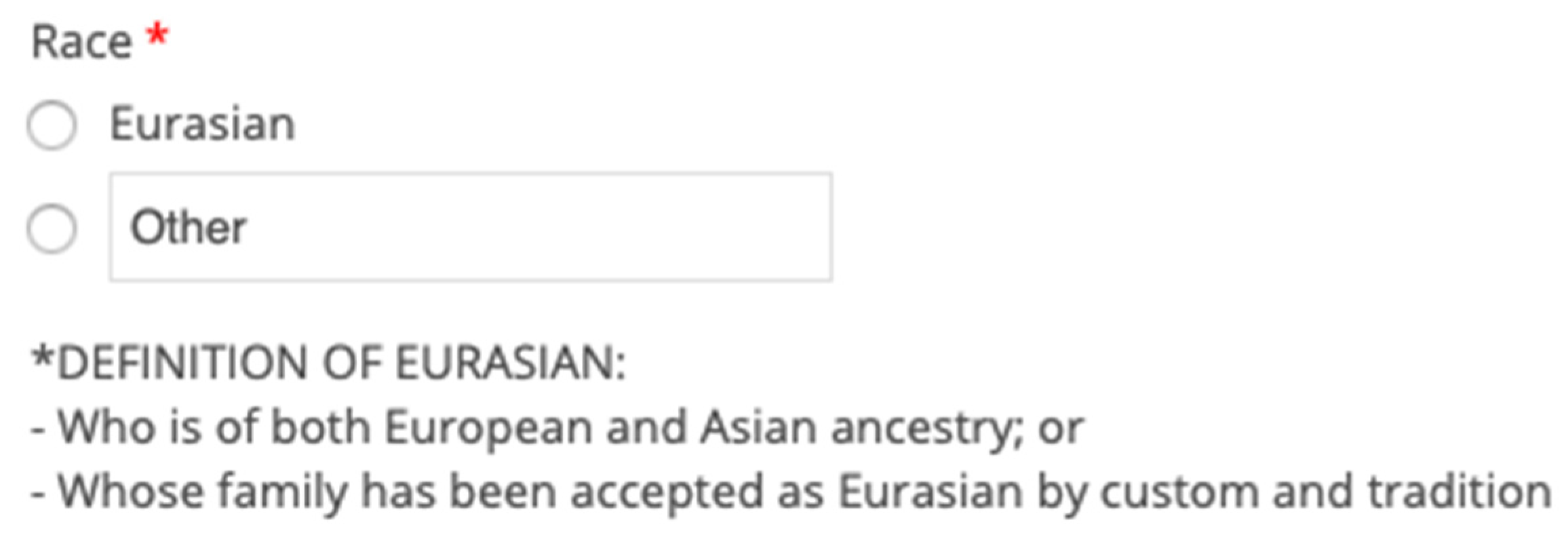

The current website of Eurasian Association is a good example of the pressure to be both well-defined and inclusive. With the slogan: “To Enrich the legacy of our Cohesive and Vibrant Eurasian Community that is integrated with and Contributing to a Multi-ethnic, Multi-religious and Multi-cultural Singapore”, the previous online membership form for the EA asked for race, providing a very particular, and notably broad, definition (see

Figure 1).

This broadening did not go unnoticed by participants, with some seeing the growing openness as contributing to the lack of clarity around what it means to be Eurasian:

I think the term—because of the government’s policies about what constitutes a Eurasian, further complicated by the Eurasian Association’s policy of what constitutes a Eurasian, it’s basically—it comes down to as basic as ‘if you think you’re Eurasian we can accept that, and you can count as Eurasian’.

(Wayne, male, age unknown)

Others felt that this opening up was what was going to keep the community relevant in multicultural Singapore, finding a balance between preserving the cultures of the past and including the contemporary mixedness within the population.

I think paradoxically if the community is going to survive it’s got to move beyond itself, which is really weird. And I don’t know how it’s going to happen. But it’s got to stop being so insular, I think. Because the insularity has sort of paralysed it. And as of right now it’s so fragmented and diffuse that there’s just no sense of Eurasian-ness.

(Kenneth, male, 24)

This push–pull relationship around inclusion, exclusion and definition featured prominently in many narratives, highlighting the competing representations, divisions and hierarchies of worth within the community itself, and underpinned by the definitional role of the EA. Competing representations of authentic Eurasian identity were evident in participants’ narratives, from pure to mixed, new and old, fair and dark. Some described true Eurasians as “pure-bred” while others joked about Eurasians who saw Eurasian-ness as too pure and precious to be touched.

The EA has literally defined and re-defined representations of mixedness and Eurasian identity over the years: culturally and administratively. Eurasian has come to represent a heritage based on mixedness and a solidly defined ethnic group within the CMIO framework; an identity which is both passed down and re-invented every generation, pure and mixed (

Rocha and Yeoh 2019). Eurasian culture is made distinct by markers which are drawn from only one aspect of Eurasian-ness, based around Portuguese descent. This has provided the community with the necessary features to belong as a race within the Singaporean framework, but has also served to distill and exclude other aspects of what it has meant to be Eurasian over the years, with this new representation excluding all others at an official level (

Pereira 1997,

2006;

Rocha and Yeoh 2019). As described by one participant, classification has become more and more difficult:

With the Eurasian community it’s very difficult because what the heck is a Eurasian, right? Who qualifies? So maybe a 100 years ago it was very easy, you had Portuguese and Dutch and British. But now you’ve got new Eurasians, you’ve got people who are - like, a Chinese person who marries a Malay person, and some people call that Eurasian as well and you’re like, why? So a lot of contestation—I think it was a good model starting out, but now it’s probably a bad idea.

(Kenneth, male, 24)

Over the past decades, social representations of mixedness have shifted and changed, with overlapping and sometimes contradicting processes of definition, inclusion and exclusion. Eurasian as a defined label has moved away from colonial patterns of paternal European descent, to a requirement for (at least) one Eurasian parent, and finally to a much broader scope of anyone of mixed European and Asian heritage, across all generations (

Braga-Blake 1992;

Pereira 1997,

2006;

Rocha 2011). Mixing and boundary crossing are very much a part of everyday life for many people in Singapore, and Eurasian identity and the role of the EA illustrate the contradictions and shifting representations that accompany this lived fluidity within a racially structured framework.

6. Conclusions

This paper has explored mixedness from a social representations perspective, drawing out how “everyday” understandings of mixed racial and ethnic identities in Singapore have developed and changed over time. In tracing the genealogy of the term and category of “Eurasian” in the Singaporean context, the study illustrates how the meanings of and borders around mixedness are created and maintained, and how state and social representations of identity and culture interact. Drawing on the work of Hall in particular, this approach draws out the ways in which mixed identities are represented and understood in different ways: by the state, by community groups and by individuals, highlighting how Eurasians in Singapore live with and within these representations. Social and historical context shape contemporary representations of mixedness, and individuals work around these constraints, stitching the subject into the wider social structure (

Hall 1992). Mixed identities and identification are crucial, with inclusion and exclusion being strategic and positional, and identities increasingly recognized as complex and multiple, rather than simple and singular. As Hall describes: “Identity is always in part a narrative, always in part a representation. It is always within representation” (

Hall 1991, p. 49).

Singapore thus provides a unique and important case study when tracing genealogies of mixedness. As this paper has shown, the multiracial state has a strongly racialized system of population management, positioning mixedness in different ways, to different ends, across colonial and post-colonial periods. The complex genealogy of the term “Eurasian” illustrates these shifts, seen in social representations of mixed identity at state and social levels. As an identity which draws on histories and narratives of both mixedness and purity, Eurasian identity emphasizes the constructed yet powerful nature of operationalized ethnicity in Singapore, providing a key example of how identities based around mixedness can be simultaneously fluid and fixed.

Shifting representations of mixedness are seen in the role of the Eurasian Association, which utilizes both state and social representations of identity, and functions as a community group and as an agent of the state in defining and representing the “race”. By locating and defining Eurasians to fit with the CMIO categories, and thus gain state recognition, the EA has repurposed static and monoracial definitions of racial identity to encompass mixedness, leading to a curious state of inclusion and exclusion in terms of who belongs as Eurasian. As described by

Howarth (

2006), the negotiations of the EA and Eurasian individuals illuminate the unexpected ways in which social representations can be used to challenge, resist and reinforce ideologies around race, which “…invade our social relationships and co-constructions of self-identity” (pp. 78–79).

In conclusion, our study has contributed to theoretical development around social representations of mixedness in three ways. First, we have drawn on social representations theory to highlight the dynamism and messiness of identity constructions associated with Eurasian-ness, and the overlaps and disconnects between colonial and post-colonial conceptions of mixedness. Internal distinctions and hierarchies of mixedness/Eurasian-ness are clearly seen in the Upper Ten/Lower Six divisions within the Eurasian community in Singapore, and shifts in definition over time illustrate the amorphous and fluid boundaries around who counts as mixed, and who does not. Second, we have argued that not all social representations are equal and some have more powerful effects than others. In the context of a nation-state where the primary social contract binding the people of the nation is predicated on racialized categories of identity, the role played by the Eurasian Association in reviving, formulating and curating representations of Eurasian-ness is foremost in navigating the multiracial state. Third, we also found that dominant social representations of mixedness are unevenly and often strategically accepted, modulated, deflected and resisted by those whom the representations claim to represent. The multiplicity of identity meanings that emerge among our participants reflects the struggle between old and new representations of the reality of mixedness at “the intersections of social positionings, power relations and hierarchies” (

Erel et al. 2016, p. 1349). By exploring the genealogy of Eurasian identity as mixed and pure (sometimes simultaneously), this paper contributes to the development of theory around the social representations of mixedness, using the unique context of Singapore to highlight the constructed realities of mixed racial and ethnic identities over time and across space.