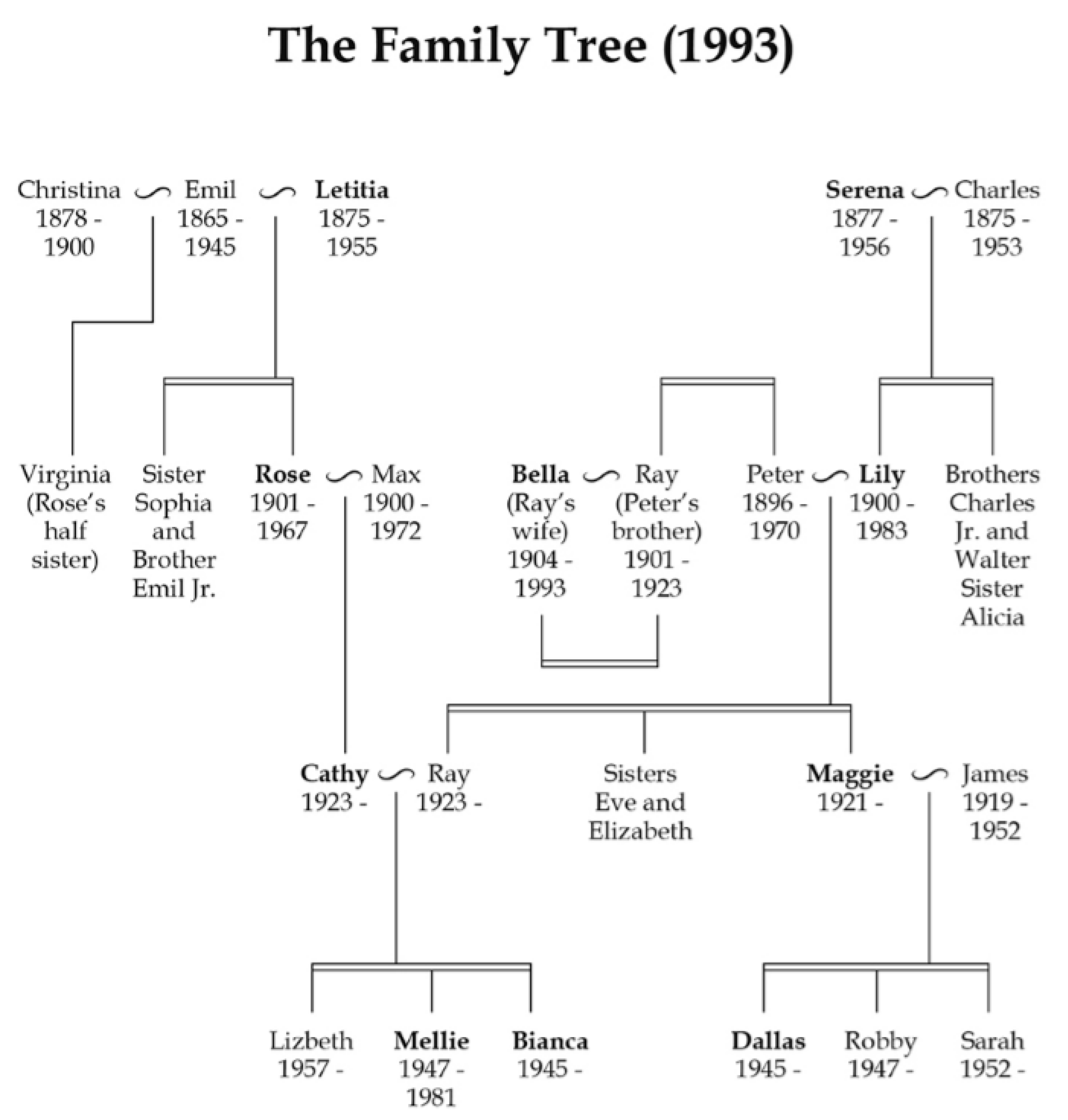

Bella’s Legacy is a fictional family saga, covering four generations in Midwestern America from the late 19th to the late 20th centuries (see

Figure 1). Geography was a defining feature in their lives as emphasized by (

Nash 2017) in her discussion of the profound impact that places have on family history. As she points out, whether staying or moving between places, these locations are as important to family history as dates. The first generation in the book is based on the lives of my great-grandparents, all either immigrants or the children of immigrants originating in Germany, Prussia, Belgium, and Britain. It appears these ancestors all continued traveling without interruption after their arrival on the East Coast, heading to what later became Wisconsin, Michigan (following some years in Canada), Dakota, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania. By the end of the 19th century, when my novel begins, my father’s side of this generation had settled in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and my grandparents moved from there to rural Northern Wisconsin. They essentially followed opportunities for work with the Soo Line Railroad, where my grandfather, his father, and his father’s younger brother were all railroad men.

In 1944, just before the end of World War II and after their oldest daughter and only son (my father) had left home as adults, these grandparents followed opportunities on the railroad once again. This time they moved with their two youngest daughters to Schiller Park, Illinois, which is a suburb of Chicago adjacent to O’Hare Airport and a major hub for Soo Line operations. My travels included visiting their former home in Schiller Park to find it completely remodeled (including my grandfather’s unfinished basement workshop now an apartment occupied by extended family) and the neighborhood transformed with a first generation of new immigrants from Poland. With their move to Chicago, my grandmother began 17 years employed as office staff by Sears Roebuck in downtown Chicago. There had been no real opportunities for her to work outside the home in rural Northern Wisconsin, and there were no family stories regarding whether this might have been one of the reasons they moved to what must have been a challenging new environment. Without knowing the true history, I could nevertheless use fiction to paint a picture of a woman wanting a better future for her and her daughters, something that might be possible only by moving to the big city.

4.1. The Men and Their Work

My father’s autobiography was about a man who was in the first generation of his family to attend college, graduate with a degree, and/or complete a professional qualification. Interestingly, his children—me and my siblings—had always been told that my paternal grandfather was the only one of our four grandparents to graduate from high school. That turned out to not be true—both of my father’s parents finished high school, and I found the graduation records to prove it. Why, I wondered, was this story repeated so many times over the years? Why did the family erase from memory the fact that his mother—my grandmother—had also received her high school diploma? One explanation could be that the stories in my father’s family history truly centered on the men, their working lives, their struggles to make a better life for their families, and their accomplishments. Another explanation could be sourced from the common American myth of a self-made man who rises from humble beginnings and makes something of himself: that was the way my father saw himself. He had risen above the status of his family background to become a college graduate and a professional man, and I never seriously questioned his conviction that this was primarily through his own motivation and hard work rather than reflecting parental expectations. Only years later did I give some thought to the fact that not only he, but his three sisters as well achieved higher education qualifications: surely, their parents had something to do with this? It was not my father alone who was the first to go to college—it was his entire generation, men and women alike. Interestingly, Argonne claimed to be the first school district consolidated in Wisconsin in 1907, suggesting education was considered important in this community.

The character based on my father’s father Peter (1896–1970) was still working as a laborer at the plywood veneer mill in Gladstone at age 25 when the first daughter was born to him and his wife Lily, as is documented on her birth certificate. Interestingly, two years later when my father was born, Gladstone birth certificates no longer listed parental occupations but continued to list their birthplaces. Their third baby either miscarried or died at birth at which time they had moved south to tiny Argonne, Wisconsin. As noted above, the next daughter was born in Gladstone once again and the youngest daughter was born in Argonne. At the time, Argonne comprised about fifty families, a large three-story brick school house in the center of town, a hardware store, two general stores, a meat market, the post office, three hotels, a garage, two filling stations, about fifteen taverns, a barber shop, a cheese factory, three churches (Catholic, Lutheran, and Methodist), and the town hall. There were three telephones in town, one of which was located at the railroad depot, hence providing my grandfather with some access to that luxury. Fifteen seems a lot of taverns for such a small community, but in a letter to his sister, my father noted that in one of those, the only stock was one bottle of whisky and one case of beer—perhaps “tavern” was quite different from the larger beer halls of later years. Argonne was said to be well known for its moonshine stills during the prohibition years, hence the nickname Whiskey Northern was given to the Chicago North Western Train that passed through this little community (

Youth Community Conservation Improvement Program 1980).

Peter’s father, my great grandfather, was a railroad man who had risen to roundhouse foreman and mechanic in Gladstone, so when there was an opening for a roundhouse foreman in Argonne, it may be that family influence was responsible for his promotion from laborer at a plywood factory to take up the railroad job. Argonne was the connection for Soo Line Railroad supply lines of timber and goods—from Minneapolis in the West, Gladstone in the Northeast, and Chicago in the South—and while an important transfer point, it was tiny and there really was no “roundhouse” but rather a circular area where it was my grandfather’s job to turn the engine to face its next destination. Working for the railroad was difficult and dangerous in the late 19th and early 20th century: Peter worked 16-hour days, six days a week, with no sick leave; the telegrapher was the only other employee of the Argonne station. Working conditions in many jobs were grim and dangerous during those years, and the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated annual workplace injury deaths at more than 30,000 fatalities in the early 1920s, and 75,000 workers died in the 25 years before World War I. One of those deaths was my father’s uncle, his namesake and Peter’s younger brother, killed in a switching accident on the tracks at age 22. The Great Railroad Strike of 1922 was launched by seven of the sixteen railroad labor organizations, and the collective action of 400,000 railroad workers in the summer of 1922 was provoked by deep cuts to wages. Armed company guards shot and killed a dozen workers and bystanders including a woman and two boys (

Wikipedia 2016). Years passed before conditions working on the railroads were substantively improved, however, and Peter’s job in Argonne must have been both arduous and lonely.

Peter was entrepreneurial, however, and managed to be elected to the highest paid part-time position with the district school board as District Clerk, for successive three-year terms at a salary of USD 200 per year in the 1930s. I found his handwritten school board minutes from 1935 to 1940 at a time when the school principal and the math teacher were being paid USD 210 per month and USD 110 per month, respectively. These minutes provide a window into how a small-town school in Northern Wisconsin functioned at the time, as is illustrated by the following excerpts:

A discussion was had concerning Mr. X as bus driver. Complaints being received that he did not report sub-ordinate children to the principal and to the parents but spanked and cuffed them himself when not necessary. The clerk reported that after talking with witnesses, that Mr. X did not overdo it and that in order to maintain discipline on the bus it was necessary to use strict measures. (26 February 1937)

Motion made and seconded that the clerk write a letter to Senator LaFollette asking him to do all he can in putting through the Education Bill whereby the Federal Government appropriate funds to the states to be distributed to schools throughout the state. (15 June 1937)

The Board called Miss R in for an interview. She was informed her work in her classroom was not what was expected of her and that the Board wanted to see a big improvement by Xmas or else they would have to get another teacher in her place. (1 December 1938)

The clerk informed the Board that the small S. girl was attending school in the first grade. After a discussion, it was decided to let the girl attend school but that the clerk notify Miss W [the teacher] not to give her a report card. (18 March 1940)

Motion made, seconded, and carried that the Board hold back the wages of the teachers until they have filed their affidavits showing that they have had a skin test for tuberculosis. (27 September 1940)

There are several aspects of these entries into the minutes that reveal interesting historical facts. The community was engaged in political petitioning to increase school funding, questions were raised regarding appropriate discipline of students and whether a child with disabilities could attend school (and under what circumstances), teacher performance was subjected to some sort of review process (and that teacher submitted her resignation two weeks later), and, finally, there were consequences to not providing evidence of testing for tuberculosis. This latter entry was intriguing especially as a close family relative—the father of two young children—had died in his late 20s of tuberculosis within this timeframe.

Ray (1923–2012) is the character based on my father’s stories (

Meyer 2011). In his autobiography, he describes how he realized at a young age that the dentist, the physician, and the attorney were the elite class of nearby Crandon, and he “wanted some of that” deciding then he would become a dentist and move south to Oshkosh “where it was warm” (

Meyer 2011, p. 20). He finished his professional degree in dentistry, one sister finished nursing school, and the two youngest sisters completed master’s degrees. The stories of Ray’s childhood in a tiny village in Northern Wisconsin are perhaps the most authentic in the book, and my roots tourism took me to Argonne, Wisconsin, to visit his places and interview people there who knew the family and the history of the town. Ray’s family home did indeed lack indoor plumbing and his father Peter (1896–1970) was a railroad man all his life, as was his father before him and the young uncle killed in a tragic accident while working on the tracks. Peter’s wife Lily is one of the women who is a major character in the book, and her life is largely painted based on facts discovered in records, archives, and other sources in addition to family stories and my having known her as a child. Lily’s mother Serena and her father Charles (1875–1953) were the family branch still living in Gladstone on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The character Charles—like the man he was based on—was first employed as a laborer in a plywood factory but soon became a cooper then a filer based on his skills.

It was, more than anything else, the occupations of the men and the location of their work that set the stage for their children to finish high school and then, in turn, for their children to go to college. There was a determination to develop professional skills and escape the bleak poverty of rural Northern Wisconsin, but it was the cheap land taken from Native Americans that gave all of them their fresh start.

4.2. The Women and Their Aspirations

The main character and narrator of my novel, Bella, is almost entirely fictional. She is, however, based on a young woman described in my father’s book about whom little is known in my family. Her real name was Ruth Herbst, she was born in Gladstone, Michigan, and she married my grandfather’s younger brother who is my father’s namesake. I was able to locate details of the marriage, when they were both very young, in a newspaper clipping including the location of their wedding, names of those in attendance, plans to honeymoon in Chicago, and that they would subsequently live at his parents’ home in Gladstone (

Escanaba Daily Press 1922). The wedding announcement listed his employment by the Northwestern Cooperage & Lumber Company, the largest business in Gladstone at the time covering more than 50 acres and a source of work for over 1000 men working full-time jobs. Ruth’s employment was also noted as being “in charge of the alteration department at the Rosenblum dry goods store, owned by Henry Rosenblum”, with the added comment that she would return to her job after the wedding. Dressmaking was an area where women could work and, apparently, earn a decent living: Willa Cather’s character in her 1918 novel

My Antonia has a successful dressmaking business in Lincoln, Nebraska (

Cather 1918).

At some point, Ruth’s new husband changed employment to work for the railroad—like his father and his brother (my grandfather)—and then was killed in a tragic switching accident only one year after their marriage, at age 22. At the time of his death, my grandmother was several months pregnant with my father, so they decided to name him after this deceased uncle. My father refers to Ruth as “Aunt Billie” in his autobiography and tells of her visiting Argonne, driving a black touring sedan that looked like a 1920 Ford Model T with curtains to hang from the roof down to the car body during cold weather. At the time, the average cost of a new Ford was just under $300, the average annual income was just under $1400, and the average home cost a little over $3000. Ruth gave my father $3.42 in pennies for his first savings account, and he never saw her again: she moved from the area two years after her husband’s death.

Ruth must have been an interesting woman for the 1920s, and in my novel, she ventures to Columbia University to enroll in its journalism program—a pioneer of the times—and then becomes a well-known investigative journalist in the muckraker style. Her character thus enabled two things: (a) opportunities to describe historical context including some of the challenges facing professional women in a man’s world during the 20th century and (b) giving me a narrator for the family saga and a feasible end to the story reflective of women’s struggles. Following Ruth Herbst Meyer’s departure as described in my father’s book, I have been unable to locate any further information about her—not surprisingly given the possibility that she remarried and may have taken another new surname. Perhaps publication of this article will lead to someone recognizing her and the revelation to me of her true story!

Ray’s wife Cathy encapsulates the life of many educated women in the 1950s, not unlike the main character Daisy in

The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields (

Shields 1993). Daisy was never able to achieve what she might have done because she had succumbed to the social and family constraints surrounding her. My character Cathy became the major support person for her ambitious husband Ray’s dentistry practice, working as his office manager rather than returning to teaching, which had always been her dream. Cathy raises three daughters, and her mother Rose admonishes her on her deathbed to try to support the daughters to become who they wanted to be—to try harder than falling into the pattern of becoming props for the men in their lives. My mother courageously returned to college when she was in her sixties and completed her qualifications to teach reading, as she had always wanted to do: it was my younger sister who encouraged and supported our mother emotionally to overcome her hesitation about being the oldest student in class. She then tutored children in reading part time until she and my father retired and moved to a warmer climate. Women in America still struggle with demands to balance career with family, whereas it is assumed almost without question that a man’s career comes first. It is the men who continue to receive a sort of “extra credit” for being the kind of father who also spends some time with the children.

There is one other 1950s woman in my book: Maggie, born in 1921. Aspects of Maggie’s story were based on the life of Peter and Lily’s daughter, who was two years older than their only son Ray. Telling a version of her story enabled me to research some of the challenges faced by women seeking a career in the military and as a nurse, as well as opportunities no longer available to someone once diagnosed with a disability—in her case, epilepsy. Immediately after graduating from high school in Argonne, Maggie enrolled in the Catholic St. Agnes School of Nursing in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. She is listed as one of the fifty freshmen students in the 1939 incoming class in the St. Agnes School of Nursing school newsletter,

The Agnesian. This same issue of the newsletter also reported details of a Big Sister–Little Sister reception held at the school during the first week, naming many of the faculty nuns on hand to greet the new class. Finally, the issue reprinted a letter written by one of the young women to her parents one month after beginning her studies, proving an authentic picture of what nursing school was like at the time for these students, including what it felt like to be away from home for the first time in their lives (

St. Agnes School of Nursing 1939, p. 1).

Her plans to become a nurse were cut short by what family members referred to as an “affliction” or “illness”. It was not until several years after her death that it was revealed by one of her children that she had been diagnosed with epilepsy: she had had her first, unexpected tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure as a young adult. Maggie joined the Navy’s WAVES—the acronym used for the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service that was modeled after the Army’s WAAC (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps). These were the first two branches of the military to allow women to serve, achieved through the advocacy of Eleanor Roosevelt, who was First Lady, as well as other prominent women of the times. Mrs. Roosevelt no doubt had a great deal to do with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s order to the Navy in 1944 to admit not just white women but also women who were African American, despite Frank Knox, who was then Secretary of the Navy, stating that they would be allowed in the Navy WAVES “over his dead body” (

MacGregor 2001, p. 87). Not only was it a struggle for both white women and women of color to be allowed to enlist in the military, they faced even more discrimination based on gender. Navy Nurse Corps nurses were not allowed to marry naval men in 1943, hence my fictional character Maggie marries her naval officer, and she must sign the mandatory discharge papers that end her career. The policy changed briefly to allow Navy nurses to marry, but by November 1943, the restriction was reinstated and not changed again for over twenty years.

Even if the prohibition against married nurses in the military had not existed, Maggie’s epilepsy stood in the way of this career choice after her first seizure in 1948. She had been able to maintain her nursing registration despite being prevented from serving in the military for the time being because of her marriage, but the diagnosis meant that too was lost. The real character upon whom Maggie was primarily based did not marry a Navy man, but the man she did marry died of a heart attack shortly after their third child was born in 1956. She attempted to return to college to become a kindergarten teacher, but that opportunity was also prohibitive due to her diagnosis of epilepsy—regardless of whether she had even had a seizure in recent years. Today, epilepsy is no longer a basis for denying either nursing or teaching registration, nor does gender restrict women who marry while placing no such restrictions on the men who do. Women have succeeded in opening doors towards achieving more equal rights in the workplace, but the glass ceiling seems to hold firm even as late as 2020 given the Equal Rights Amendment still had not been passed by the U.S. Congress.

There is one other character in Bella’s Legacy who is not based on anyone in my family, who is entirely fictional, but whose story is reflective of women’s issues in not just the 20th century but continuing into today. My high school class comprised over 500 seniors graduating in 1963, and of that number I knew of three girls who experienced a teen pregnancy. This was before Roe v. Wade became law in 1973, so abortion was not really an option. I also knew a fourth girl just out of high school—the girlfriend of a friend of my boyfriend—who tried unsuccessfully to terminate her own out-of-wedlock pregnancy with a coat hanger and nearly died. As teenagers, no one talked openly about these pregnancies, but we all knew what it meant when a friend went away to “visit her aunt” for several months in the middle of the school year: the girl was going to have a baby, and her baby was being given up for adoption. It was not only shameful to reveal to the world through a pregnancy that a girl engaged in premarital sex, it was inconceivable—particularly in middle class families—to keep the baby and raise him or her in either a teen marriage or as a single mother. Between 1945 and 1973, an estimated one and a half million babies were given up for adoption to unrelated families: having sex was far more prevalent than access to birth control and sex education.

Fifty years later, I learned that one of the three in my class had subsequently searched for her lost daughter and found her. Another girl never talks about that first baby, and I know nothing about the third nor whether there were others. Author Ann Fessler, herself an adoptee, interviewed over 100 women who had surrendered their babies during those decades before the Supreme Court ruled access to abortion under certain conditions would henceforth be legal. (

Fessler 2006)’s stories are heart-wrenching, and they made me determined to include a story about this feature in American history and women’s lives, regardless of whether it happened in my own family. Among my own children, two were adopted at six years of age, so not taken from their mothers at birth. However, we know that many of the stories told to the adopted children and to the adoptive parents about the birth parents were untrue: they were tales created to make everyone feel better, and they certainly de-emphasized the very real possibility that the birth mother was ambivalent or even resistant about giving up her baby. I wonder now whether what we were told about my adoptive children was fabrication, exaggeration, or a downright lie, and I was recently pleased that DNA testing reconnected my son with his birth family siblings. He and I are both celebrating this opportunity to learn more about who he is and where he is from—especially important to him as an African American whose ancestors will forever remain unknown other than the tribal affiliations revealed by the DNA testing.

In

Bella’s Legacy, a fictional character named Mellie (1947–1981) becomes pregnant at 15 following sex in the backseat of a car with a boy from her neighborhood. Mellie is Cathy and Ray’s daughter, and she is terrified as the year is 1961 and she knows her Catholic parents will be furious as well as heartbroken. The fictional Mellie becomes one of

The Girls Who Went Away (

Fessler 2006), and years later the daughter whom she gave away is re-connected with her birth family, giving Cathy the opportunity for redemption for how they had reacted and what they had done all those many years earlier. Her character may be fictional, but what happened to her happened to millions, and these lost connections have major implications for not just genealogical research but for people’s lives (

Clapton 2018;

Patton-Imani 2018;

Sales 2018). (

Hoyle 2018)’s essay “So Many Lovely Girls” tells the painful story of years of silence beautifully.