Abstract

This critical family history explores a common script about undocumented immigration: that undocumented immigrants unfairly have refused to “stand in line” for official, sanctioned immigration and instead have broken rules that the rest of “our” families have followed. Noting a hole in her knowledge base, the author put herself on a steep learning curve to “clean her lenses”—to learn more information about opportunities past and present, so she could see and discuss the issue more clearly. The author sought new and forgotten information about immigration history, new information about her own family, and details about actual immigration policy. She wrote this piece to share a few script-flipping realizations, in case they can shortcut this journey for others.

Introduction

On 5 September 2017, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions first announced Trump’s revocation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) federal policy, which offered a temporary reprieve from deportation for a subset of undocumented young adults brought as children. The same day, the Superintendent of the San Diego Unified School District emailed all families. She promised to keep young people safe—and she reminded readers of the Supreme Court’s Plyler v Doe decision that by law, schools must educate undocumented children.

“I wanted to personally assure you the San Diego Unified School District remains committed to protecting the right of every child to an education. All children are welcome in our school community”, she wrote, in bold. “San Diego Unified will maintain its commitment to providing ALL students with an education in a safe, productive learning environment. This has been the law of the land since 1982…”.

She quickly received angry personal emails from multiple parents complaining of her “left-wing agenda”. Most of the angry emails ignored the legal realities of her point and argued that undocumented children took up resources they did not deserve as non-“Americans”.

We have heard this basic idea repeated continually in Trumpian efforts to expel immigrants. It is the idea that new immigrants, and undocumented immigrants specifically, “take resources” undeservedly. We will hear it more as national leaders decide immigrants’ fates.

It took this era of vitriolic anti-immigrant rhetoric for me to recognize how deeply this same basic idea was ingrained in me.

It is a moment for each of us to clarify our take on undocumented immigration. Undocumented immigrants are our neighbors everywhere. In San Diego, according to immigration lawyers, we have long had proportionately more undocumented immigrants, DACA recipients, and refugees alike, relative to other cities.

As a San Diego resident, I knew as soon as Trump was elected that I needed to decide how much I would stand up to defend people in the U.S. without documentation. As a professor, would I sign public petitions in support of undocumented immigrants? (I have done so, most recently a petition to support a UC San Diego DACA student detained at the border after taking a wrong turn from the mall). As a supporter of many local schools serving undocumented immigrants, would I stand in front of the door of a K12 school if ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) tried to enter? Would I protest ICE vans grabbing students’ relatives outside a school building, as educator colleagues in LA have done? Or would I allow my own gut thinking about “legal” immigration and who “deserves” to be here, to keep me passive and silent as students and families got hauled away?

So, just after the installation of an explicitly anti-immigrant administration, I sat quietly for just a minute and asked myself whether I would stand up publicly or physically to protect undocumented immigrants in my town. I was surprised that my gut said “not sure”—and I quickly realized that I had a common script in my head about that lack of documentation. This script said that undocumented immigrants unfairly have refused to “stand in line” for official, sanctioned immigration and instead have broken rules that the rest of “our” families have followed. My script told me that “we”—my family, and “documented” immigrants—waited patiently in line, while undocumented people jumped that line and somehow exploited the system and so, the rest of “us”.

I then realized that there was not much information undergirding this script—just reactions in my gut. And I then acknowledged that even as a professor who studies race and education in the United States, undocumented immigration has been a pretty gaping hole in my knowledge base. I was repeating that script to fill the hole.

So, I put myself on a steep learning curve to fill it with facts. I followed my own advice (see Schooltalk) and started to clean my lenses—to learn more information about opportunities past and present, so I could see and discuss the issue more clearly in time to make a decision. I sought new and forgotten information about immigration history, new information about my own family, and details about actual immigration policy. I have written this piece to share a few script-flipping realizations, in case they can shortcut this journey for others – particularly, “white” people like me.

Script Flip 1: Many Ancestors of Today’s “White” Americans Never Really “Stood in Line”. They—for Many Readers, “We”—Actually Benefited from Lax and Preferential Immigration Policy

Here is the punchline: many ancestors of today’s “white” Americans got an easy, preferential path to citizenship.

Historian Mae Ngai’s short piece “How Grandma Got Legal” (2006) shows that throughout much of U.S. history, European immigrants deemed “white” poured through open doors. They just came and became citizens later. Very few were turned away. For example, as Ngai writes in her book Impossible Subjects (2004), “the Immigration Service excluded only 1 percent of the 25 million immigrants from Europe who arrived in the United States from 1880 to World War I” (p. 18). (See also Jennings 2018.) For Europeans, “There were so few restrictions on immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries that there was no such thing as ‘illegal immigration’”. After 1920s-era immigration restrictions, policies for “illegal” European immigrants’ inclusion still “recognized that once a person settled here, had a family, a job and a home, he or she became a part of society” and should not be deported (Ngai 2006).

Here is the most shocking part: for most of U.S. history, an immigrant had to be considered “white” to become a naturalized U.S. citizen at all.

A Gallop through Recent Immigration History

I keep reminding myself of the following fact, because it startles me each time: The Naturalization Act of 1790 explicitly reserved U.S. citizenship and its benefits to “free white persons”. This racial restriction of the ability to become a citizen once in the U.S. (to “naturalize”) was not fully rescinded until 1952. Ian Haney Lopez (1997) sums it up in White By Law: “From the earliest years of this country until just a generation ago, being a ‘white person’ was a condition for acquiring citizenship” (p. 1).

In explicit contrast to “whites”, for example, “Asians” were long formally excluded from both entry and citizenship. In 1882, the bluntly named “Chinese Exclusion Act,” intended to restrict U.S. jobs to “whites”, barred “Chinese” immigrants from migrating to the U.S. at all (some found loopholes and came anyway, at great personal cost). This law was not repealed until 1943—and, as Ngai documents (2004), a quota then restricted annual “Chinese” immigration to 105 “Chinese” from anywhere in the world (p. 203). Exclusionary laws and court decisions also long deemed “Asians” already in the U.S. “racially ineligible for naturalization” as citizens. These laws framed “Asians” as “permanent foreigners” for a century (Ngai 2004, p. 18).

Others deemed “non-white” in the U.S. experienced reduced forms of inclusion and citizenship—even if they lived here before many Europeans. African Americans laboring involuntarily as slaves were literally considered 3/5 of “persons” in the Constitution, and non-citizens in the famous Dred Scott case. If you were a “Person of African nativity and descent” in the U.S., Ngai writes (2004), you were not granted a collective path to citizenship until after the Civil War—and other than the brief window of Reconstruction, African Americans still were not actually afforded the basic rights that came with that term, like the right to vote, which was stolen via Jim Crow laws and practices (p. 38). After the ravages of European colonization, Native Americans were legally granted U.S. citizenship in 1924, while remaining citizens of sovereign nations within the nation (Ongtooguk and Dybdahl 2008)—but they were also denied ancestral lands and forced to attend schools dedicated to eradicating their cultural practices. And, as historians note, people of Mexican descent in the U.S. have experienced a particularly schizophrenic offering of “citizenship” for generations: Tomas Almaguer explains that after the U.S. incorporated much of Mexico in 1848 as California and the Southwestern states, laws offered formal U.S. citizenship rights to the region’s “White male citizen[s] of Mexico”, but lower class, often darker-skinned Mexican Americans were typically not offered such rights in practice (Almaguer 1994). And subsequently, as David Gutiérrez demonstrates, for a century and a half until now, people from Mexico were deemed quintessential “aliens” to be both invited and employed when “needed,” and deported (Gutiérrez 2016). Sometimes invited openly through programs and sometimes surreptitiously employed, “Mexicans” were tagged always potential “aliens” and “criminals”, as employers invited and profited from both “unauthorized” and “authorized” immigrant labor for generations (Ngai 2004, p. 151). The same Mexican workers were sometimes repeatedly invited over the border by employers and then deported. Depression-era sweeps erroneously and viciously deported even many American citizens of Mexican descent.

In contrast, Ngai notes, even after 1920s-era restrictions, many European immigrants who now entered or remained in the U.S. “illegally” were shepherded through processes to get approved paperwork. As Ngai puts it, even the so-called “lower races of Europe” were deemed assimilable Americans for whom deportation would be unfair. So, administrative actions—like allowing immigrants to formally exit and enter again via Canada—were devised to “unmake the illegality” of “European illegal immigrants” (Ngai 2004, pp. 58, 75–89).

The “white” story was indeed quite different: it was overall a trajectory toward inclusion.

As Ngai documents, after Europeans streamed in through open doors for centuries, stricter immigration laws in the 1920s limited migration by Southern and Eastern Europeans, deemed inferior to Northern and Western ones. “The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 marked both the end of one era, that of open immigration from Europe, and the beginning of a new one, the era of immigration restriction. The law placed numerical limits on immigration and established a quota system that classified the world’s population according to nationality and race, ranking them in a hierarchy of desirability for admission into the United States” (Ngai 2004, p. 17). Yet U.S. immigration policy still continued to invite even less-desirable Europeans into a “white” race that could become U.S. citizens eventually. While numerically preferring Western and Northern Europeans over villified Southern and Eastern ones, that is, “the quota system distinguished persons of the ‘colored races’ from ‘white’ persons from ‘white’ countries” still more welcomed overall. By excluding “nonwhite people residing in the US” from calculations determining next arrivals, “The national origins quota system proceeded from the conviction that the American nation was, and should remain, a white nation descended from Europe” (pp. 26–27).

The new laws limiting immigration, of course, created the phenomenon of “illegal immigration”. People worldwide kept moving to seek better lives and just entered the U.S. without formal visas or inspections (Ngai 2004, pp. 17, 19). Yet while many European migrants continued to enter the U.S. via Canada, for example, it was only the patrolling of the Mexican border that became particularly militarized and aggressive. “Mexicans” were framed suspiciously as quintessential immigration lawbreakers even as Mexican (and Filipino) laborers “became the mainstay of migratory agricultural labor” at employers’ invitation (Ngai 2004, pp. 66–71, 103–4).

As Ngai documents, immigration law updates in 1952 next imposed quotas on “the migration of black people” to the U.S., and continued to restrict “Asian immigration” while still numerically prioritizing Western and Northern European immigration. Even as 1950s-era policy finally “eliminated the racial bar to citizenship” via naturalization once immigrants were legally admitted to the U.S., it also restricted that initial immigration more to people with specialized skills and family ties (Ngai 2004, p. 238). Only in 1965 did our policies open up immigration to the U.S. from many different parts of the world, including many new people of color (Keating and Fischer-Baum 2018). Yet, Ngai writes (2004) that while new quotas finally replaced Western and Northern European preferences with “equal” immigration from each country in Europe, Asia, and Africa alike, they also enforced a severe reduction in Latin American immigration (p. 258). The 1960s policies also prioritized higher skills along with family reunification; such laws particularly brought more educated “Asians” to the U.S., with longstanding consequences for how we compare immigrant groups. New laws now disproportionately created “illegal immigration from Mexico and Central America” (Ngai 2006). By 1976, new immigration laws specifically imposed annual quotas on Mexico, allowing just a fraction of its annual actual immigrants lawful entry. These new quotas made a disproportionate number of Mexican immigrants formally “illegal,” and disproportionate expulsions of Mexicans reinforced the mental association of “illegality” with Mexicans even while employers continued to invite their low-cost labor (Ngai 2004, p. 261). This racialized association persists despite the broad diversity of undocumented immigrants: David Gutiérrez noted recently that “although illegal immigration has come to be perceived primarily as a ‘Mexican problem,’” almost half of unauthorized immigrants have “overstayed valid tourist, student, or other visas” and come “from virtually every other nation in the world” (Gutiérrez 2016).

For centuries, then, European “whites”—and Western and Northern European “whites” particularly—were both invited and allowed “in” more than everybody else, and then proactively offered an invitation to the benefits of full, “legal” citizenship. Restrictions on everyone else meant, in part, more “illegal” entry by those restricted, because humans kept seeking opportunity and employers kept employing. As Ngai puts it, “illegal migration would rise as legal avenues for immigration were shut off”. And throughout American history, people of color—including people there before Europeans—were often denied any citizenship “line” to stand in.

Cleaning our lenses about our own families’ migration histories is a crucial part of understanding our opportunity circumstances relative to others’. Kevin Kumashiro and John Lee invite students to consider factors pushing their own families out of home countries, pulling them into the U.S., and then providing advantage or disadvantage once here (Lee 2013). Christine Sleeter (2015) suggests similarly that we investigate our own “critical family histories” through family interviews or review of secondary sources. The goal is to clean our lenses on how we got where we are—to understand ourselves, as well as others, as people shaped by opportunity contexts (see Pollock 2017, chp. 2). Notably, one journalist calls her work on this #resistancegeneology (Ghert-Zand 2018).

So, I next asked my parents about our own family’s migration experiences—and our experiences with citizenship.

Script Flip 2: After Immigrating Freely, Many “White” Ancestors Got Citizenship Pretty Easily—Because the Government Just Decided They Could

I already knew that my paternal grandfather came to the U.S. just before World War I in 1914, via England, as a Jewish immigrant toddler with family escaping violence and poverty in Lithuania. Putting his story on the history timeline above, I realized consciously for the first time that Grandpa benefitted from laws that privileged European immigration through an open door. Grandpa came before laws restricted migration by Eastern Europeans and Jews like him.

I also realized that I had never asked about Grandpa’s actual citizenship: I had assumed without asking that he had always “had it.”

So, I asked my dad, who clarified that Grandpa did not get official citizenship until he was drafted into the Army at age 30 to fight in World War II. “When he was drafted and required to take some sort of oath of allegiance, he told the Army he wasn’t a citizen”, my dad said. “They told him, ‘You are now.’”

Grandpa was one of those white ancestors who showed up in a pre-World War I time without restrictions on Europeans—and he was later given citizenship easily, because the U.S. wanted him to have it. In a quick review on Ancestry.com, we found my grandfather’s U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records from when he was drafted in 1942. Yes indeed: his “race” was listed matter-of-factly as “white, not yet a citizen”. In a 1940 census, at age 28, he had been deemed “White” and “Alien”. His parents were both still listed as “Alien” too, with his younger sister (born in England) in progress, “having first papers”. Other siblings had since been born in the United States. (A 1930 census [age 18] also listed Grandpa as “Alien” in a field labeled “naturalization”. A 1920 census had listed his eight-year-old “race” as “white” with language “Yiddish.”).

This meant my own grandfather went to public school and worked a job without citizenship—something I had never considered. Until his early 30s, my own grandfather was, as Marcelo and Carola Suarez-Orozco have put it, “a citizen in everything but paper”—and, like Dreamers, brought involuntarily, in the arms of parents seeking survival. Unlike Dreamers, Grandpa was simply recorded matter-of-factly on official immigration lists because there were no restrictions on his European entry. Paperwork missing for other Europeans was not a problem: as Ngai (2006) notes, “The Registry Act of 1929 allowed immigrants who arrived before 1921 but had no record of their admission to register retroactively, for a $20 fee”.

Grandpa’s situation begged another question I had never asked myself. Was Grandpa less of an “American” all those days before his citizenship paperwork?

My gut supplied the answer immediately: of course not. He was the same person before his citizenship paperwork as the day after it, contributing his labor and then risking his very life for the country. The citizenship paperwork just gave a stamp of approval to a circumstance he already had. And notably, the government let him have that paperwork without any problem at all: he was deemed an “Alien” eligible for citizenship. In contrast, the U.S. government in World War II would be interning 120,000 Japanese Americans, “two thirds of them citizens”, in an extreme application of what Ngai (2004) calls “alien citizenship”: citizens were treated like “aliens” (p. 175).

Grandpa was an “alien” treated like a citizen. Throughout U.S. history, the U.S. government let folks have citizenship when it wanted to. And “white” people benefited disproportionately.

“White” people benefited further once citizens, too. After the war, when Grandpa had no family wealth to buy a home and little high school education, he benefited from the GI Bill. The GI Bill at the time extended affordable home loans, employment training and benefits, and educational subsidies disproportionately to white veterans—particularly because white-run banks and loan programs made it disproportionately hard for people of color to qualify for mortgages, while local officials blocked access to other benefits (as did employers and segregated colleges). Like other Cleveland Jews newly treated socially as “white”, Grandpa and Grandma used his VA credit to buy their first house in an all-white, segregated neighborhood—one literally colored blue on a map I found, meaning it was notated as a neighborhood without “Negroes”. (Check your family’s housing history at Mapping Inequality (n.d.): https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58) They soon sold that first house at a profit, moving to a bigger house in a neighborhood that, before the war, had typically excluded Jews like them. By the time I bought my first house circa 2000, two generations of accumulated housing and employment wealth—plus property taxes supporting well-funded neighborhood schools—had supported my father’s college education, my own, and then a down payment on my house (see Pollock 2017, chp. 2).

So, my Grandpa’s “whiteness” undergirded our family’s wealth accumulation even though he was not a citizen for his entire youth. The government decided to give citizenship to him—and benefits followed for our whole family, just like for millions of other “white” people who benefited from similar opportunity patterns.

I investigated the immigration story of the other side of my family next.

Script Flip 3: Many Earlier Generations of European Americans Came Seeking Refuge, Just Like People Today. The Government Just Let Them Take Refuge in America

My mom was born in a displaced persons camp in Germany, just one of multiple refugee camps my grandparents experienced in the painful aftermath of the Holocaust. While my grandparents had served as forced laborers in Stalin’s freezing Gulag in Siberia, their siblings, parents, and extended families had been murdered in Poland by the Nazis and their local helpers. My mother came to the U.S. in 1950 at age three with her emotionally battered parents. She was the first English speaker in the household, with Yiddish the household language (of the multiple European languages my grandparents spoke, they chose to speak Yiddish to their children because, as refugees, they did not know where they would end up). Talking to my aunt, our family historian and my mom’s younger sister, my mom and I put it together that Mom lived with approved “refugee” papers but without formal citizenship until age eight, when she became a naturalized citizen along with her parents and my aunt.

My mom had told me the story of showing up in the citizenship paperwork office again as a high school senior with her younger sister, to get a copy of her individualized paperwork before college at her parents’ insistence. She had hated how she looked in the black and white picture they took there—and it had been an odd reminder that she had an early childhood without U.S. citizenship. She had had childhood nightmares about being taken away by the police, and post-Holocaust family trauma as her parents processed the murder of siblings and parents. But, as a teen, she was also a classic hippie, an artist heading to art school. In my mind as a kid, actually, she was not an “immigrant” at all. Mom now remembered the clerk in the citizenship paperwork office saying, “you speak better than me”. Her answer was classic Mom: “why shouldn’t I?”

In my consciousness, my mom’s adult efforts at caring for our grandmother, the real “immigrant” identity in our lives, was the only “immigrant” remnant she carried with her. My grandparents’ home—with its kosher plates and piles of paperwork related to caring for other elderly Americans in two nursing homes they owned—was, to us, the immigrant home. They had the accents; they told the Old World and Holocaust stories.

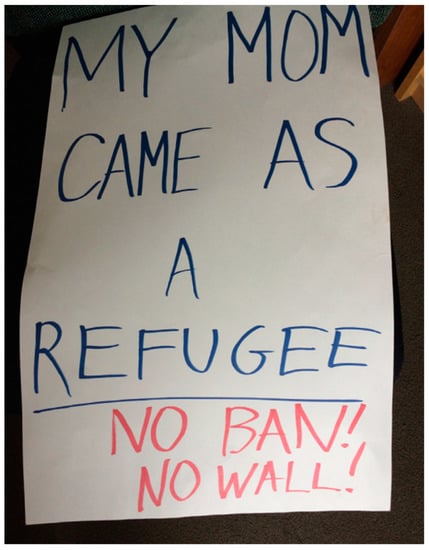

So, what I had never done before the Trump era’s explicitly anti-immigrant stance was to really identify as an immigrant’s daughter—and particularly, to identify with the “refugee” label in my mom’s experience. In spring 2017, I finally saw a photo of the actual yellowed 1950 entry paperwork stamped “refugee”, texted by my aunt now living in Canada. I made a sign noting this reality—“MY MOM CAME AS A REFUGEE”—and carried it at the protest against the Muslim Ban in San Diego (Figure 1). I wanted people to see my “white” face and consider something only now amplified in my consciousness: that refugees exist in all communities. That “They” are all of “Us”.

Figure 1.

Sign carried by author at Muslim ban protest, San Diego, January 2017.

The difference, of course, was that my mother was granted refuge—like so many earlier “white” Americans, who poured through Ellis Island with little restriction. My mother’s family did not arrive so “freely”: they were granted entry after two decades of U.S. antisemitism-fueled, lethal failure to grant entry to “refugees fleeing from fascism’s spread in Europe”. (Ngai notes that only after World War II’s ravages did “addressing the European refugee crisis” become “a geopolitical imperative” with still-limited quotas.) But Ngai (2004) also points out that refugees from elsewhere in the world were still not prioritized at all (p. 35). While my grandparents (unlike earlier open-door travelers) waited for years with great anxiety for that formal refuge opportunity circa 1950, they had nonetheless received it. And notably, they became citizens just three short years after the 1790 Naturalization Act’s racial restriction of naturalized citizenship to “free white persons” was fully rescinded. My aunt showed me the line where someone determined her “complexion” on her 1965 citizenship paperwork. It said “medium”.

Trump advisor Stephen Miller’s own Jewish ancestors came seeking this same refuge circa 1900. Miller has spent his young career crafting exclusions for others seeking the same. He also seems to have forgotten that his own ancestors leveraged the ability to link to family members and neighbors already here, more established residents who could help guide newcomers through finding housing and jobs (Eshman 2016). The manifest from the ship that carried my mother, aunt, and grandparents to the U.S. in 1950 had notated their country of origin (Poland), religion (“Jew”), an organizational sponsor (the “Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society”), and a named relative willing to support, plus a home address offered by another. People like Miller now denigrate this rational pattern of “chain migration” as a selfish opportunity grab, even as so many of “us” followed the same chain links across borders. Ngai noted in 2018 that a particularly restrictive bill introduced by Senator Tom Cotton, Republican of Arkansas, “would reduce legal immigration by 43 percent by eliminating most family preferences” altogether.

So, a question arose for me again. Was my refugee mom far less of an “American” at age eight, pre-citizenship, than at age nine, post-citizenship-ceremony? My gut replied again: of course not. She heard and spoke another language at home; she was even sent to a religious school and afterschool program. But she was no less “American” than anyone in her class. She was simply a pre-citizenship American who had officially been granted refuge.

Why would today’s families seeking refuge while brown-skinned or Muslim not deserve safety and the opportunity to contribute too? What reasons do we have for slamming the door on their own quest for survival, other than their skin color or religion? Is it not the case that the difference between a sanctioned “refugee” and one turned away is just about who the government decides to accept? My mother simply squeezed in when refugees like her were allowed. And like Stephen Miller—and Donald Trump!—I am alive and here just because a prior U.S. government accepted my ancestors.

Today, primarily “white” descendants of earlier families seeking refuge from poverty or violence are politicians in the driver’s seat of deciding who gets refuge now. They seem to forget that families will keep seeking refuge regardless—just like our own desperate families sailing on boats away from horror.

Script Flip 4: Once Here, Today’s Undocumented Immigrants Contribute to and Benefit the United States, Economically and Socially, Just Like Undocumented and Documented Immigrants always Have. The Difference Is that the Government is Deciding Not to Offer Them a Path to Citizenship

The nation has long relied on the labor and contribution of both “authorized” and “unauthorized” immigrants, alongside generations of unpaid slaves and others born here. Some immigrants today, invited “in” openly with advanced degrees and visas, fill the high-skilled jobs employers need filling; many still have arduous paths to stable residency (and some even then become “undocumented”). Andrea Guerrero notes that companies experiencing barriers to hiring needed immigrant labor sometimes move out of the country, losing jobs for everyone (2013). And today, as yesterday, undocumented immigrants from across the globe also serve in jobs that employers want them to fill, including jobs “native” workers do not want (Enchautegui 2015). As with prior generations, that is, immigrants without formal legal status are also here in the U.S. because employers entice and employ them to fill foundational roles in the U.S. economy. David Gutiérrez points out that “the use of unauthorized labor” has been “a systemic feature of the U.S. economy” for generations (Gutiérrez n.d.). It is just that many such immigrants today are offered no “line” to legal immigration—unlike my Grandpa, who delivered ice for years and then easily became a citizen.

Instead, even as their labor is knowingly tapped to stabilize the U.S. economy, these undocumented workers constantly have to hide their immigration status from others—and punishment rains down on them, the workers, alone (Pérez 2009). Meanwhile, as Enrique Murillo points out (Murillo 2002), employers often reap the economic benefits of immigrants’ underpaid labor without contributing money to human social supports like schools (or employee retraining); immigrants themselves are routinely blamed for the imbalance, leaving our nation’s workers fighting each other. While some highly skilled, openly employed immigrants are able to achieve middle-class status immediately (and send their children to well-resourced schools), migrants offering skills for low-wage employment typically arrive to segregated, under-resourced low-income schools and a particularly hostile reception. Indeed, Americans resent them particularly, even as their labor, too, benefits “us” daily: as Patricia Gándara noted to me, two obvious examples are the child care and eldercare workers enabling “our” own careers.

Furthermore, like other Americans’ ancestors, today’s immigrant families often live in the U.S. “undocumented” and still contribute to American taxes, Social Security, communities, and schools, while waiting for pathways to open to become citizens. Research makes clear that undocumented Americans participate eagerly in the economy and in local communities; as Kathleen Coll demonstrates, they, like their neighbors, contribute via jobs but also via schools, religious congregations, community groups, and labor organizations (Coll 2010). Many undocumented high school and college students do disproportionate community service and volunteering, and often excel at their studies with educators’ support, despite attending under-resourced schools (Pérez 2009). Rules barring their legal citizenship essentially limit their further citizenly contributions.

Without legal employment, that is, students simply cannot put their full education to work for the country’s growth, innovations, and economy. “These students are aspiring doctors, lawyers, and teachers”, Peréz notes, but their full contributions are blunted: without some ability to work legally, “the education they receive is [just] useful for personal growth” (Pérez 2009, p. 144, xxxi). Roberto Gonzales noted several years ago that each year, 65,000 undocumented high school graduates (a graduation rate now estimated at 100,000/year; Migration Policy Institute 2019) left the legally protected K12 space for an existence of newly shadowed, stigmatized and restricted “illegality” (Gonzales 2011); they now could not fully contribute economically or educationally, as they lacked Social Security numbers enabling jobs or, often, college aid (Abrego and Gonzales 2010, p. 145). Given “the lack of nine digits”, many later would have “few job choices outside of physical labor”, despite their degrees. As Gonzales stated, “We must ask ourselves if it is good for the health and wealth of this country to keep such a large number of U.S.-raised young adults in the shadows” (Gonzales 2011, pp. 613–5, 617).

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) federal policy attempted to remedy this situation by providing a temporary reprieve from deportation for a subset of undocumented young adults brought as children—“undocumented youth between the ages of 15 and 31 who arrived before age 16, had continuously resided in the United States since June of 2007, had a graduate equivalency diploma or a high school diploma or were enrolled in school, and had not been convicted of felonies or serious misdemeanors” (Yoshikawa et al. 2016, p. 7)—and offering them “temporary Social Security numbers and two-year work permits” (Gonzales et al. 2015, p. 337). Through DACA’s protections (won in part through immigrants’ own advocacy), the nation could more fully benefit from young people’s labor and energy, and not waste this “valuable national resource” (Pérez 2009, p. xxxvii). Indeed, without DACA, states and localities (like San Diego) that have already invested in undocumented children’s education per law are denied the ability to fully benefit economically and socially from former students’ potential contributions—including their power to create new jobs for others (Pérez 2012, p. 147).

Meanwhile, as they wait and advocate for citizenship possibilities, “The undocumented actually contribute more to public coffers in taxes than they cost in social services” (Pérez 2009, p. xxi). “Undocumented immigrants are taxpayers too and collectively contribute an estimated $11.74 billion to state and local coffers each year via a combination of sales and excise, personal income, and property taxes”, states a report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. “On average, the nation’s estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants pay 8 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes every year” (Gee et al. 2017). If simply allowed to fully contribute to American profits, “DACA beneficiaries [would] contribute $460.3 billion to the U.S. gross domestic product over the next decade” (Wong et al. 2017). And, notably, “Refugees brought in $63 billion more in government revenues over the past decade than they cost”—a finding that Trump administration officials have apparently sought to bury (Davis and Sengupta 2017).

While undocumented immigrants are already contributing socially through volunteer and personal labor in their communities and neighborhoods, then, as Kathleen Coll notes, they also stimulate local economies and jobs over time (Coll 2010). Meanwhile, “rather than draining state resources, undocumented immigrants are, in some cases, subsidizing services that only documented residents can access” (Pérez 2009, p. xxii). Hiro Yoshikawa notes that “Children and youth with unauthorized status are excluded from the safety net of most means-tested federal and associated state programs” (Yoshikawa et al. 2016, p. 4). Indeed, many undocumented parents never enroll their citizen children in public early childhood programs their children are eligible for, out of fear (Yoshikawa 2011, p. 138). Proposals by the Trump administration would punish even legal immigrants and their families for applying for public benefits they are eligible for (Miroff 2018).

And finally, many of the jobs employers want and get filled by undocumented immigrants offer no paths to legal immigration: there is no “line” to get into. As Yoshikawa demonstrates, this situation keeps undocumented people working overtime and in extremely poor conditions, without protections against exploitative employers who benefit from hiring immigrants cheap—as U.S. employers always have done (Yoshikawa 2011). Meanwhile, “native” workers resent immigrant peers, rather than demanding better from employers.

So, reports continue to show that immigrants of all legal statuses have an overall positive effect on the economy and our communities. But for “undocumented” contributors, the doors to full legal citizenship and maximum contribution just never open. Since Trump’s decision to end DACA, deadlines have passed with Congress unable to decide on new policies clarifying DACA recipients’ fates. Meanwhile, “the courts weigh legal challenges over how the administration went about ending the program”, leaving DACA recipients in ongoing “limbo” (Shoichet 2018).

Meanwhile, today’s undocumented immigrants contribute no less than our ancestors did, or other Americans do. In particular, I am left asking: why should “white” ancestors have merited inclusion more than they do?

Flipping the Script for Good

Recently, my husband and I took our kids to New York City and spent some time exploring the city’s history. At our first stop, the Museum of the City of New York, I started to think of New York as the human Grand Canyon, with layers upon layers of contributors arriving over time. At the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side, we learned how people toting babies like my toddler grandfather came and packed themselves in great numbers into tiny raggedy apartments, layered with predecessors’ wallpaper. They pieced clothes together without lights; they washed diapers on dirty stoves. They lifted weights too, fantasizing about boxing careers; they read hidden romance novels, because they, too, were humans with dreams. They shared bath houses offering short spurts of water down the block and ripped newspapers for toilet paper. The docent said the same kind of apartment, now $3000 a month down the street, packs in new immigrants from China, also laboring, laboring, laboring—some while undocumented.

Through the generations, many also came running from violence. At the Statue of Liberty, we heard Emma Lazarus through the headphones, calling for the U.S. to take the “wretched refuse” of the world, those “yearning to breathe free”. I had not known she was talking about Jews escaping pogroms at the time, like my grandfather’s family from Lithuania. I had actually never associated my family with the statue at all, though now I realized they had seen it in transit (I also did not know that the gorgeous statue is literally hollow and thin-skinned, nor that women were barred from her debut but came, defiantly, in boats to see her unveiling).

Watching a film on Ellis Island, I imagined my grandfather’s parents in the classic “immigrant arrival” footage for the first time—and, for the first time, I noticed how European-dominated it was. Those interviewed spoke in thick European accents of the necessity of escape from jobless countries, from countries where police would “cut your head off” if you were the wrong kind of person. Some cried describing first seeing the beckoning Liberty. Others cried about “becoming human again” after the button-hook eye tests, the final mental exams, the manifests and checks with chalk. They cried about walking, after weeks of seasickness and years of terror, onto a land that shockingly accepted the refuse of Europe.

How quickly we forget. How quickly our gratitude fades.

Checking Facebook in the cracks of our New York trip, I saw a white Facebook friend of mine from San Diego post a cartoon about “the problem with illegal immigration”. The cartoon compared the end of-year income of “legal John” (drawn as a “white” person) vs. that of “illegal Juan”, drawn as a Latino. My friend is not mean-spirited, but the cartoon was. It was filled with the kind of distortions that inflame and mislead our hard conversations about immigration today.

Into the vast echo chamber of Facebook, I tried to repeat some points I had learned to my friend:

- While in the cartoon Juan pays no taxes, undocumented people actually do;

- While in the cartoon Juan gets government welfare, undocumented people actually do not;

- Undocumented people pay taxes, yet cannot access benefits like cash welfare or housing/rent subsidies;

- Undocumented people have been able to use emergency health services, but not because they are unfairly “undeserving”—because public health crises benefit no one;

- Undocumented children by law can access public schools, because they, too, are residents of a shared nation—and because forced inclusion in an uneducated populace benefits no one, and because investment in children’s talent development eventually serves us all.

Silently, I wondered about my white friend’s own family history. Did her ancestors come freely through an open door, like my Grandpa? Were they granted refuge, like my mom? Did they live in the U.S. before actually getting citizenship papers, like both sides of my family? And then, did they benefit—like Grandpa and many others—from government programs and private actions that helped “white” people live in segregated neighborhoods, send kids to more-resourced public schools, and disproportionately build their wealth? Or did she truly buy her sunny San Diego home without prior government-offered invitations, acceptances, paperwork, and benefits? Without grateful migration past the golden door?

Along the way, many white Americans’ ancestors took advantage of pathways to safety and citizenship and economic prosperity not made available to fellow humans deemed too brown.

Why would these contributors not be just as valuable?

Today’s federal government leaders and many voters want the US to be largely unavailable to the next contributors—and to people who come in need, just like their families did. These current leaders echo earlier layers of white Americans who also wanted to cruelly slam the door on other people. They echo all the laws saying only “white” men with property could vote, the laws deeming only “white” immigrants able to become citizens, the laws excluding “Chinese” people altogether, the laws and practices denying “Mexicans” and “Negroes” and “Indians” opportunities of all kinds for generations through today. They echo old sentiments prioritizing “whites” over the rest.

Indeed, these exclusionary voices are trying, hard, to hard-wire the very term “American” as “white”. But defining “American” is itself an act of inclusion or exclusion by the describer.

Today’s exclusion comes from “us.”

Over time, in America, many of our own families gained privilege that we no longer recognize. Yes, they worked hard for their gains, too; they were just invited over others to advance. Many of us have lost the ability to recognize others’ human similarity, human needs, and actual contributions. Many people want to slam the door behind them.

The old script in my head had me ready to slam that door as well.

Most immediately targeted for exclusion now, of course, are young immigrants like my grandfather and refugees like my mother—and people like their parents, who came escaping violence and poverty while holding children. None of today’s targeted immigrants are requesting particularly special treatment. Their desire to come, or “stay”, is no different from prior immigrants’ desires. Prior leaders just decided immigrants like my family were “part of society” and should be allowed.

In my family’s experience, being “American” before being formally granted citizenship meant taking refuge here, living here at length, contributing to U.S. communities, and identifying as “American”. Like my family, today there are Americans who are just not yet citizens on paper—either because that process is delayed or because they are in “limbo” situations where no citizenship pathway is made available to them despite their contributions. As Ngai (2018) summarizes,

“Mr. Cotton, Mr. Trump’s policy adviser Stephen Miller and other hard-liners envision a fortress America that welcomes only skilled people from predominantly white countries, people who in general show little interest in moving to America… restrictions on legal immigration will lead to more undocumented immigration from the global south. Idealized immigrants from Europe aren’t going to pick lettuce or wash dishes, just as most native-born white Americans don’t. And the nativists will have nothing more helpful to propose than heartless policing and deportation to discipline an underclass of nonwhite people that their own policies created”.

Immigrant advocates estimate that there are 40 thousand DACA recipients currently laboring in limbo in San Diego alone. And today, our pre-citizenship neighbors live in daily existential terror: as Andrea Guerrero describes, Border Patrol appear at homes and workplaces, on streets and on trains, asking residents for “papers” inside the United States (Guerrero 2013). As my UC San Diego colleague Abigail Andrews put it, today, a San Diegan originally from Mexico “could have lived in the U.S. for 30 years, starting at age 3 or 10 or 15, paid taxes, joined the army, studied and/or worked in the U.S., have U.S. citizen children, and still be deported and spontaneously ripped from their U.S.-born families; these folks literally have no way to become citizens”. Andrews started a project with deportees in Tijuana, a few miles from where we both live and work. “It is unimaginably heartbreaking to see these fathers (most of them are fathers) ripped from their lives, children, and families”, she says. Raids take parents from children at work, outside school, and in the middle of the night— just because today’s government, with the backing of many forgetful citizens, has decided to slam the door. Meanwhile, deportation for some means death (NPR 2020)—while families left waiting at the border are destroyed (Garbus 2019). As Ted Hamann puts it (Hamann and Morgenson 2017), “Trump’s deportations and threats of deportations may not stop the undocumented from looking for and finding work, but it will divide parents from children” (p. 134).

More of us need to check our guts and explore our families. More of us have to remember that our “undocumented” neighbors’ actual lives differ from our “documented” ones only in that the government proactively gave us the privilege of documentation and refuge.

To recapture our shared humanity, it is up to each of us to proactively clean our lenses on the issue of undocumented immigration and decide what we think about it.

Will we distort, exclude, and deport the next layer of the US? Or will we recognize our fellow humans as simply our next layer of contributors?

It is up to us if Liberty’s torch still burns.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am still on a learning curve on discussing immigration. If you would like to continue the dialogue, contact me at micapollock@ucsd.edu. I am deeply grateful to people who responded to early drafts of this material as I learned. They bear no final responsibility for how this piece turned out: Ted Hamann, Kathy Coll, Roberto Gonzales, Hiro Yoshikawa, Patricia Gándara, Sheldon Pollock, Abigail Andrews, Frances Contreras, Estera Milman, Isa Milman, David Gutiérrez, Vivian Louie and William Pérez. Thanks also to Minhtuyen Mai and Dana Chung for their efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abrego, Leisy J., and Roberto G. Gonzales. 2010. Blocked paths, uncertain futures: The postsecondary education and labor market prospects of undocumented Latino youth. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk 15: 144–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaguer, Tomas. 1994. Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, Kathleen M. 2010. Remaking Citizenship: Latina Immigrants and New American Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Julie Hirschfeld, and Somini Sengupta. 2017. Trump Administration Rejects Study Showing Positive Impact of Refugees. New York Times. September 18. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/18/us/politics/refugees-revenue-cost-report-trump.html (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Enchautegui, Maria E. 2015. Immigrant and native workers compete for different low-skilled jobs. Urban. Available online: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/immigrant-and-native-workers-compete-different-low-skilled-jobs (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Eshman, Rob. 2016. Stephen Miller, meet your immigrant great-grandfather. Jewish Journal. August 10. Available online: https://jewishjournal.com/opinion/rob_eshman/214361/stephen-miller-meet-immigrant-great-grandfather/ (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Garbus, Martin. 2019. What I saw at the Dilley, Texas, immigrant detention center. The Nation. March 26. Available online: https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/dilley-texas-immigration-detention/ (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Gee, Lisa Christensen, Matthew Gardner, Misha E. Hill, and Meg Wiehe. 2017. Undocumented Immigrants’ State & Local Tax Contributions. Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy. Available online: https://itep.org/immigration/ (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Ghert-Zand, Renee. 2018. Using #resistancegenealogy, journalist exposes immigration hardliners’ hypocrisy. Times of Israel. January 24. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/using-resistancegenealogy-journalist-exposes-immigration-hardliners-hypocrisy/?utm_source=The+Times+of+Israel+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=b608987cd5-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_01_24&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_adb46cec92-b608987cd5-55133313 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Gonzales, Roberto G. 2011. Learning to Be Illegal: Undocumented Youth and Shifting Legal Contexts in the Transition to Adulthood. American Sociological Review 76: 602–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Roberto G., Luisa L. Heredia, and Genevieve Negrón-Gonzales. 2015. Untangling Plyler’s legacy: Undocumented students, schools, and citizenship. Harvard Educational Review 85: 318–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, Andrea. 2013. Immigration Reform: A Chance for a Better America: Andrea Guerrero at TEDxNashville. TEDx Talks. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvciFjn2v98 (accessed on 15 May 2013).

- Gutiérrez, David G. 2016. Illegal Immigration and Border Enforcement in Historical Perspective. In Oxford Handbook of the History of Immigration and Ethnicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, David G. n.d. An Historic Overview of Latino Immigration and the Demographic Transformation of the United States. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/heritageinitiatives/latino/latinothemestudy/immigration.htm (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Hamann, Edmund T., and Cara Morgenson. 2017. Dispatches from Flyover Country: Four Appraisals of Impacts of Trump’s Immigration Policy on Families, Schools, and Communities. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 48: 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Kevin. 2018. Yes, your ancestors probably did come here legally — because ‘illegal’ immigration is less than a century old. Los Angeles Times. January 14. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-jennings-legal-illegal-immigration-20180114-story.html (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Keating, Dan, and Reuben Fischer-Baum. 2018. How U.S. immigration has changed. The Washington Post. January 12. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/national/immigration-waves/?utm_term=.202178521ddf (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Lee, John. 2013. The Hidden Four Ps and Immigration. Available online: http://christinesleeter.org/hidden-four-ps/ (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Lopez, Ian Haney. 1997. White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America. n.d. Available online: https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=4/36.71/-96.93&opacity=0.8 (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Migration Policy Institute. 2019. Nearly 100,000 Unauthorized Immigrants Graduate from High School Every Year, New MPI Analysis Finds. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/nearly-100000-unauthorized-immigrants-graduate-high-school-every-year-new-mpi-analysis-finds (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Miroff, Nick. 2018. Trump proposal would penalize immigrants who use tax credits and other benefits. Washington Post. March 29. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/trump-proposal-would-penalize-immigrants-who-use-tax-credits-and-other-benefits/2018/03/28/4c6392e0-2924-11e8-bc72-077aa4dab9ef_story.html (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Murillo, Enrique G., Jr. 2002. How Does it Feel to Be a Problem? ‘Disciplining’ the Transnational Subject in the American South. In Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity. Edited by Stanton Wortham, Enrique G. Murillo, Jr. and Edmund T. Hamann. Westport: Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Mae. 2004. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, Mae. 2006. How Grandma got legal. Los Angeles Times. May 16. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-may-16-oe-ngai16-story.html (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Ngai, Mae. 2018. Immigration’s Border-Enforcement Myth. New York Times. January 28. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/28/opinion/immigrations-border-enforcement-myth.html (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- NPR. 2020. Salvadorans Are In Danger after Deportation from U.S., Report Says. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2020/02/06/803292006/salvadorans-are-in-danger-after-deportation-from-u-s-report-says (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Ongtooguk, Paul, and Claudia S. Dybdahl. 2008. Teaching Facts, Not Myths, About Native Americans. In Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real about Race in School. Edited by Mica Pollock. New York: The New Press, pp. 204–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, William. 2009. We Are Americans: Undocumented Students Pursuing the American Dream. Sterling: Stylus. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, William. 2012. Americans By Heart: Undocumented Students and the Promise of Higher Education. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Mica. 2017. Schooltalk: Rethinking What We Say About—And To—Students Every Day. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shoichet, Catherine. 2018. The DACA deadline that wasn’t. CNN. March 5. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/02/politics/daca-deadline-explainer/index.html (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Sleeter, Christine. 2015. Multicultural Curriculum and Critical Family History. Multicultural Education Review 7: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Tom, Greisa Martinez Rosas, Adam Luna, Henry Manning, Adrian Reyna, Patrick O’Shea, Tom Jawetz, and Philip E. Wolgin. 2017. DACA Recipients’ Economic and Educational Gains Continue to Grow. American Progress. August 28. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2017/08/28/437956/daca-recipients-economic-educational-gains-continue-grow/ (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Yoshikawa, Hirokazu. 2011. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Young Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, Hirokazu, Carola Suarez-Orozco, and Roberto G. Gonzales. 2016. Unauthorized Status and Youth Development in the United States: Consensus Statement of the Society for Research on Adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence 27: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).