The Rise and Fall of BritainsDNA: A Tale of Misleading Claims, Media Manipulation and Threats to Academic Freedom

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genetic Ancestry Testing

2.1. Ancestry Inference

2.2. BritainsDNA Company History

2.3. BritainsDNA’s Tests

“… your YDNA marker is HUNTER-GATHERER and your earliest ancestors reached Britain some time between 4000BC and 3000BC.

Your Y chromosome group, which tracks your paternal lineage, is R1b-M269. It is very common in Western Europe and also has outliers as far east as the Uigher peoples of Western China and in India and Russia.

Your Hunter-Gatherer ancestors crossed from Europe to Britain after the end of the last ice age but long before that they had undertaken a much more hazardous journey from Africa across the Red Sea into the Middle East. From there people fanned out east into Asia and Australasia and west into Europe …

When the development of farming began to spread, R1b-M269 multiplied and moved into every corner of Europe. By c3000BC it had certainly reached Britain and Ireland. And what directly caused populations to expand rapidly was the invention of porridge”.

3. Our Interactions with BritainsDNA

- That any statement, written or otherwise, which you make in relation to our client’s organisation will not suggest that their work, or the statements and opinions of Mr Moffat, are in any way fraudulent, dishonest or disingenuous.

- That you will not report or state as a matter of undisputed fact that our clients’ science is ‘wrong’ or untrue. Clearly you disagree with their approach but the basis of that disagreement is a matter of interpretation. Our clients accept that change and reinterpretation are part of the nature of scientific enquiry. But the issues of which you complain are currently issues of opinion and not matters of absolute fact, correct or incorrect.

- That you will not report anything inaccurate or misleading in relation to the funding of our client’s business, when you have no basis or knowledge of how the business was started or has been funded historically.

“The remark in the interview about a subsidy … The sentiment was that many people were working for free to get the effort off the ground and had made investments from our own funds. There is no further subsidy”.

4. The Role of the Universities

5. The Role of the Media

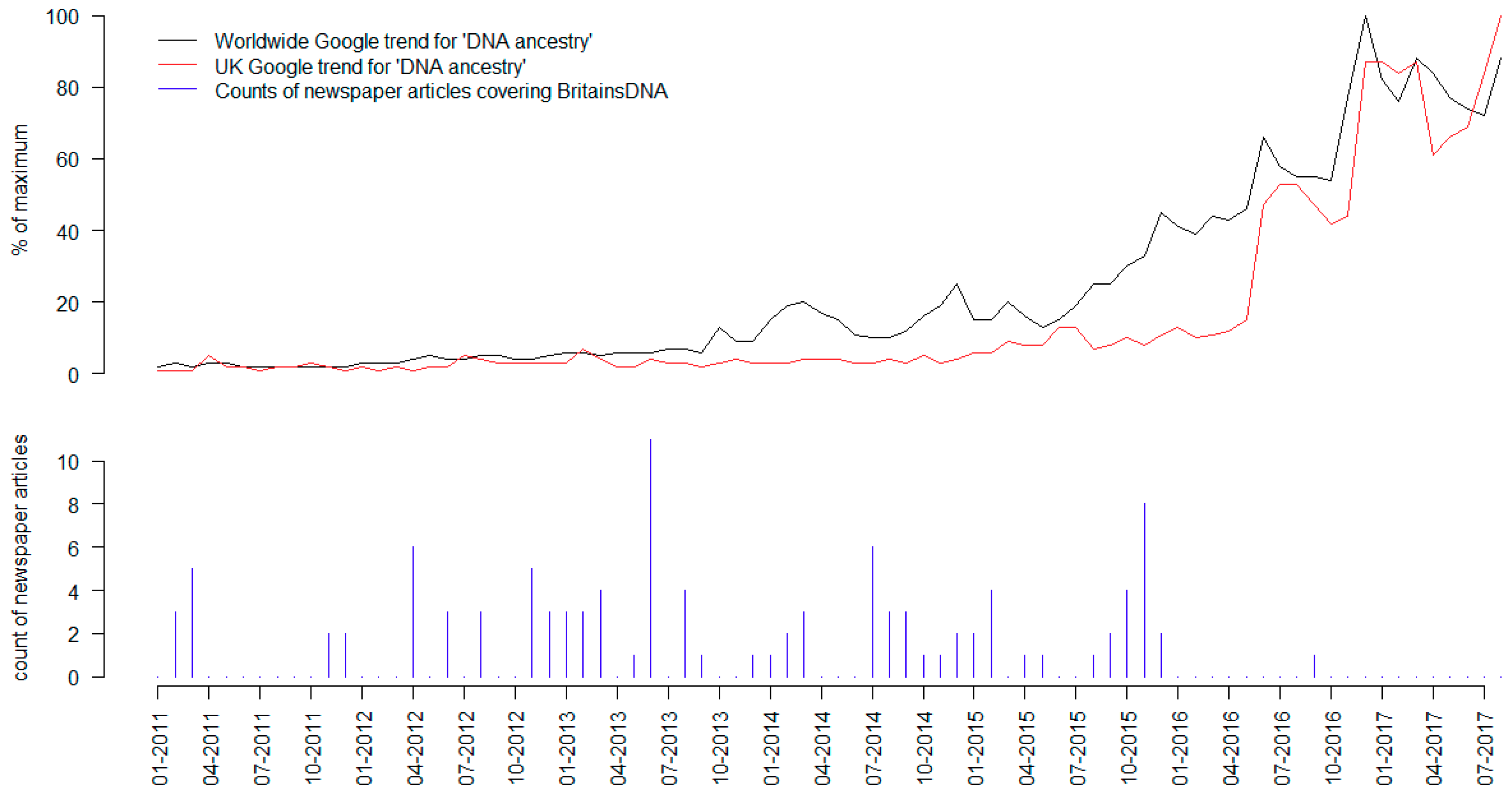

5.1. Newspaper, Broadcast and Online Coverage

“According to Moffat, Conti’s DNA marker reveals his male lineage is Saracen in origin. His ancestors settled in Italy around the 10th century before one of them, Giovanni Buonaparte, settled in Corsica and founded the family branch that produced Napoleon … He [Conti] is clearly a close relative of Napoleon. Only DNA could have told that story”.

5.2. Analysis of the Press Coverage

5.3. TV and Radio Coverage

The S4C series DNA Cymru will set out to answer the questions by using DNA samples from the people of Wales today. The series is part of an exciting project Cymru DNA Wales set up in a partnership between S4C, CymruDNAWales, Trinity Mirror—publishers of the Western Mail and the Daily Post—and production company Green Bay Media.

6. Countering the Bad Science

“…the choice of guests is a matter of editorial discretion and does not fall within the remit of the ECU. In practice that means I can consider whether what was said during the broadcast met the BBC’s editorial standards but not whether the programme ought to have invited him [Alistair Moffat] to participate.

You have also raised the issue of Mr Moffat’s appearances across the BBC over a number of years. Again, this falls outside our remit—we are limited to considering specific items broadcast or published by the BBC and are not able to investigate claims of editorial breaches over time and across output”.

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AJT | Adrian Timpson |

| DAK | Debbie Kennett |

| DJB | David Balding |

| MGT | Mark Thomas |

| MC1R | melanocortin 1 receptor |

| MRCA | most recent common ancestor |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| SNP | single nucleotide polymorphism |

| STR | short tandem repeat |

| UCL | University College London |

| Y-chr | Y-chromosome |

| Y-DNA | Y-chromosome DNA |

Appendix A. Websites

References

- Ahlstrom, Dick. 2012. Discover Your Genetic Ancestors. The Irish Times. May 3. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/discover-your-genetic-ancestors-1.513669 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Balanovsky, Oleg. 2017. Toward a Consensus on SNP and STR Mutation Rates on the Human Y-Chromosome. Human Genetics 136: 575–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balloux, François. 2010. The Worm in the Fruit of the Mitochondrial DNA Tree. Heredity 104: 419–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen, Yong-Gang Yao, Martin B. Richards, and Antonio Salas. 2008. The Brave New Era of Human Genetic Testing. BioEssays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology 30: 1246–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BBC Cymru Fyw editorial staff. 2015. Profion Rhaglen DNA Yn “Embaras”? [DNA Tests on S4C’s Program “Embarrassing Science”?]. BBC Cymru Fyw. March 9. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/cymrufyw/31708205 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BBC Editorial Complaints Unit. 2014. Today, Radio 4, 9 July 2012: Finding by the Editorial Complaints Unit. BBC Complaints. April 15. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/complaints/comp-reports/ecu/today9july2012radio4 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BBC Editorial Guidelines. n.d. BBC Editorial Guidelines. Section 4: Impartiality. BBC. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidelines/impartiality/breadth-diversity-opinion (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BBC Editorial Staff. 2012. Study Reveals “Extraordinary” DNA. BBC News Scotland. April 17. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-17740638 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BBC Help and Feedback. 2014. Corrections and Clarifications (April 2014). BBC. April 15. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/helpandfeedback/corrections_clarifications/corrections_april2014.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BBC News. 2013. Defamation Act 2013 Aims to Improve Libel Laws. BBC News. December 31. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-25551640 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BBC reporter. 2011. St Andrews Uni Chooses New Rector. BBC News. October 28. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-15502914 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Beauchamp, Rosie. 2011. Book Review: The Scots—A Genetic Journey. BioNews. June 6. Available online: http://www.bionews.org.uk/page_94283.asp (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Bevan, Nathan. 2014. S4C’s CEO Ian Jones Discovers His Ancestral Secrets. WalesOnline. November 15. Available online: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/s4cs-ceo-ian-jones-discovers-8112289 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Bolnick, Deborah A., Duana Fullwiley, Troy Duster, Richard S. Cooper, Joan H. Fujimura, Jonathan Kahn, Jay S. Kaufman, and et al. 2007. Genetics. The Science and Business of Genetic Ancestry Testing. Science 318: 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borders Book Festival. 2018. Who’s Who. Borders Book Festival. Available online: http://www.bordersbookfestival.org/whos-who/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Boseley, Sarah. 2008. Matthias Rath: Fall of the Doctor Who Said His Vitamins Would Cure Aids. The Guardian. September 12. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/sep/12/matthiasrath.aids2 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- BritainsDNA. 2014. Discover the Genetics of Your Eye Colour. Customer newsletter. August 21. Available online: https://us4.campaign-archive.com/?u=5994c989fda69d9d61b462a5f&id=241e3d0765 (accessed on 26 September 2018). Archived at http://archive.is/8nsrv.

- BritainsDNA. 2015a. February News: The Baldness Test. Customer newsletter. February 22. Available online: https://us4.campaign-archive.com/?u=5994c989fda69d9d61b462a5f&id=a0e2135e2a (accessed on 26 September 2018). Archived at http://archive.is/v9e2o.

- BritainsDNA. 2015b. BritainsDNA Reveals All for Hairy Bikers. BritainsDNA Facebook Page. October 6. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/britainsdna/photos/a.367560660018036.84193.231629543611149/868907606550003/?type=3&theater (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Brown, David. 2013a. Doomed Indian Love Story Had Happy End for the Daughter Who Sailed to a Better Life. The Times. June 14. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/doomed-indian-love-story-had-happy-end-for-the-daughter-who-sailed-to-a-better-life-7gmb7bldb7q (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Brown, David. 2013b. How a Retired Writer Found out That He Was within Spitting Distance of Royalty. The Times. June 14. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/how-a-retired-writer-found-out-that-he-was-within-spitting-distance-of-royalty-f7m8nk9p09q (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Brown, David. 2013c. Revealed: The Indian Ancestry of William. The Times. June 14. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/revealed-the-indian-ancestry-of-william-ldvsjmc9w59 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Bucks, Jonathan. 2013a. Rector Assessed: Moffat Blasted over “Laughable” Scientific Claims. The Saint. March 7. Available online: http://www.thesaint-online.com/2013/03/rector-assessed-moffat-blasted-over-laughable-scientific-claims/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Bucks, Jonathan. 2013b. University Slams Moffat for Stifling Debate. The Saint. April 11. Available online: http://www.thesaint-online.com/2013/04/university-slams-moffat-for-stifling-debate/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Bucks, Jonathan. 2014. Moffat Not Nominated for Honorary Degree. The Saint. November 27. Available online: http://www.thesaint-online.com/2014/11/moffat-not-nominated-for-honorary-degree (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Calafell, Francesc, and Maarten H. D. Larmuseau. 2017. The Y Chromosome as the Most Popular Marker in Genetic Genealogy Benefits Interdisciplinary Research. Human Genetics 136: 559–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca, P. Menozzi, and A. Piazza. 1993. Demic Expansions and Human Evolution. Science 259: 639–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca, Paolo Menozzi, and Alberto Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Abridged Paperback Edition with a New Preface. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chikhi, Lounès. 2009. Update to Chikhi et Al.’s “Clinal Variation in the Nuclear DNA of Europeans” (1998): Genetic Data and Storytelling–from Archaeogenetics to Astrologenetics? Human Biology 81: 639–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chivers, Tom. 2016. This DNA Ancestry Company Is Telling Its Customers “Mostly Total Bollocks” About Their Ancestors. BuzzFeed. December 4. Available online: https://www.buzzfeed.com/tomchivers/this-dna-ancestry-company-is-telling-its-customers-mostly-to (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Collins, Nick. 2013. DNA Ancestry Tests Branded “Meaningless”. The Telegraph. March 7. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/science/science-news/9912822/DNA-ancestry-tests-branded-meaningless.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Colquhoun, David. 2012. Abuses of Genomic Screening, Advertising on the BBC and a Shocking Legal Threat. DC’s Improbable Science. December 20. Available online: http://www.dcscience.net/2012/12/20/abuses-of-genomic-screening-advertising-on-the-bbc-and-a-shocking-legal-threat/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Companies House. 2012. Annual return made up to 9 November 2012 with full list of directors’ for the Moffat Partnership (now Source BioScience Scotland Ltd). Companies House (Beta Website). Available online: https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/SC201430 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Cooper, Rob. 2012. DNA Reveals Shirley Valentine Star Tom Conti Is Directly Related to Napoleon. Mail Online. April 15. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2130052/Shirley-Valentine-star-Tom-Conti-directly-related-Napoleon-DNA-reveals.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Cramb, Auslan. 2012. DNA Reveals the Truth about Bonnie Prince Charlie. The Telegraph. April 18. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/9211247/DNA-reveals-the-truth-about-Bonnie-Prince-Charlie.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Cressey, Daniel. 2010. “People Work All Their Lives and Never Get a Judgment like That”. Nature News. April 20. Available online: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/news.2010.192 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Cressey, Daniel. 2013. England’s Libel Laws Reformed in a Victory for Science Campaigners. Nature News, April 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cule, Erika. 2013. Are the Geeks Coming? Scientists Find Their Voice. The Guardian: Occam’s Corner. March 13. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/science/occams-corner/2013/mar/13/are-the-geeks-coming-scientists (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Davies, Elliot. 2013. Edit War Erupts on Moffat’s Wikipedia Page. The Saint. May 18. Available online: http://www.thesaint-online.com/2013/05/edit-war-erupts-on-moffats-wikipedia-page/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Downes, Michelle. 2013. Genetic Test for Ginger Hair? BioNews. February 4. Available online: http://www.bionews.org.uk/page_248739.asp (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Edmonds, Christopher A., Anita S. Lillie, and L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza. 2004. Mutations Arising in the Wave Front of an Expanding Population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 975–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epperson, Amanda E. 2011a. The Scots: A Genetic Journey—History Program from BBC Scotland. The Scottish Emigration Blog. February 24. Available online: http://scottishemigration.blogspot.com/2011/02/scots-genetic-journey-history-program.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Epperson, Amanda E. 2011b. Looking for the English in Scotland’s Genetic Past. The Scottish Emigration Blog. March 11. Available online: http://scottishemigration.blogspot.com/2011/03/looking-for-english-in-scotlands.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Epperson, Amanda E. 2011c. Viking or Gael? Episode 5 of the Scots: A Genetic Journey. The Scottish Emigration Blog. March 17. Available online: http://scottishemigration.blogspot.com/2011/03/viking-or-gael-episode-5-of-scots.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Epperson, Amanda E. 2011d. The Scots: A Genetic Journey—The 6th and Final Episode. The Scottish Emigration Blog. March 26. Available online: http://scottishemigration.blogspot.com/2011/03/scots-genetic-journey-6th-and-final.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Eriksson, Anders, Lia Betti, Andrew D. Friend, Stephen J. Lycett, Joy S. Singarayer, Noreen von Cramon-Taubadel, Paul J. Valdes, Francois Balloux, and Andrea Manica. 2012. Late Pleistocene Climate Change and the Global Expansion of Anatomically Modern Humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 16089–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, Olivier, Mathias Currat, Nicolas Ray, Eunjung Han, Laurent Excoffier, and John Novembre. 2010. Principal Component Analysis under Population Genetic Models of Range Expansion and Admixture. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27: 1257–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbault, Pascale, Robin G. Allaby, Nicole Boivin, Anna Rudzinski, Ilaria M. Grimaldi, J. Chris Pires, Cynthia Climer Vigueira, and et al. 2014. Storytelling and Story Testing in Domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111: 6159–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, Pallab. 2013. Some DNA ancestry services akin to “genetic astrology”. BBC News: Science and Environment. March 7. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-21687013 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Gibbons, Katie. 2014. Blue Eyes Are Peeping across Britain. The Times. August 30. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/blue-eyes-are-peeping-across-britain-zjfglr3l32b (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Gillespie, James. 2012. If That’s Genetics, Then I’m the Queen of Sheba. The Sunday Times. December 23. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/if-thats-genetics-then-im-the-queen-of-sheba-c6z6v889mvm (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Gillespie, James. 2014. Auntie Tells off Naughty Naughtie. The Sunday Times. March 9. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/auntie-tells-off-naughty-naughtie-7trtrmxckgl (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Goldacre, Ben. 2008. Ben Goldacre: The Food Supplement Industry’s Stifling of Debate Is Far from Democratic. The Guardian. September 12. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2008/sep/12/matthiasrath.aids (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Greenslade, Roy. 2013. The Times’s Prince William Splash Linked to Readers’ Offer. The Guardian. June 14. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/media/greenslade/2013/jun/14/thetimes-johnwitherow (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Hale, Thomas, and Gonzalo Viña. 2016. University Challenge: The Race for Money, Students and Status. Financial Times. June 23. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/c662168a-38c5-11e6-a780-b48ed7b6126f (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Harsanyi, Rozalia. 2014. Rectorial Review: Alistair Moffat’s Term Comes to an End. The Saint. October 26. Available online: http://www.thesaint-online.com/2014/10/rectorial-review-alistair-moffats-term-comes-to-an-end/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- HeraldScotland Editorial Staff. 1999. TV Executive’s £25,000 Defamation Action Fails “In-House Bully” Remark Not a Slur on Ex-Scottish Media Group Director. HeraldScotland. October 13. Available online: http://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12211094.TV_executive_apos_s__25_000_defamation_action_fails__apos_In_house_bully_apos__remark_not_a_slur_on_ex_Scottish_Media_Group_director/ (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Hern. 2013. Are There Ethical Lapses in the Times’ Story on William’s “Indian Ancestry”? New Statesman. June 14. Available online: http://www.newstatesman.com/media/2013/06/are-there-ethical-lapses-times-story-williams-indian-ancestry (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG). 2018. Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree. Version: 13.132. Available online: https://isogg.org/tree (accessed on 30 May 2018).

- Jac o’ the North. 2015. Are You Welsh? I’ll Tell You For £250! Jac o’ the North. March 9. Available online: http://jacothenorth.net/blog/are-you-welsh-ill-tell-you-for-250 (accessed on 30 May 2018).

- Jansen, Sue Curry, and Brian Martin. 2015. The Streisand Effect and Censorship Backfire. International Journal of Communication 9: 16. [Google Scholar]

- Jobling, Mark A., Rita Rasteiro, and Jon H. Wetton. 2016. In the Blood: The Myth and Reality of Genetic Markers of Identity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 142–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobling, Mark A., and Chris Tyler-Smith. 2017. Human Y-Chromosome Variation in the Genome-Sequencing Era. Nature Reviews. Genetics 18: 485–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Bobbie. 2013. How a Spit of Royal DNA Makes Money for Rupert Murdoch. Medium. June 14. Available online: https://medium.com/@bobbie/how-a-spit-of-royal-dna-makes-money-for-rupert-murdoch-f1d3fd6508bc (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennedy, Donald, and Geneva Overholser, eds. 2010. Science and the Media. Cambridge: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kennett, Debbie. 2013a. A First Look at the BritainsDNA Chromo2 Y-DNA and MtDNA Tests. Cruwys News. December 20. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2013/12/a-first-look-at-britainsdna-chromo-2-y.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2013b. A First Look at the Chromo2 All My Ancestry Test from BritainsDNA. Cruwys News. December 20. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2013/12/a-first-look-at-chromo-2-all-my.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2013c. Who Do You Think You Are? Live Day 3: Alistair Moffat on How DNA Is Rewriting British History. Cruwys News. March 1. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2013/03/who-do-you-think-you-are-live-day-3.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2013d. BritainsDNA, The Times and Prince William—The Perils of Publication by Press Release. June 19. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2013/06/britainsdna-times-and-prince-william.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2013e. Sense about Genealogical DNA Testing’. Sense about Science Blog. March 15. Available online: http://archive.senseaboutscience.org/blog.php/41/sense-about-genealogical-dna-testing.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2014. BritainsDNA, the BBC and Eddie Izzard. Cruwys News. January 11. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2014/01/britainsdna-bbc-and-eddie-izzard.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2015a. More on the S4C DNA Cymru Controversy and My Review of “Who Are the Welsh?”. Cruwys News. March 7. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2015/03/more-on-s4c-dna-cymru-controversy-and.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2015b. My Review of DNA Cymru Part 2—The Controversy Continues. Cruwys News. November 26. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2015/11/my-review-of-dna-cymru-part-2.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Kennett, Debbie. 2015c. My Thoughts on DNA Cymru Part 3 and the Significance (or Lack Thereof) of Large Genetic Clusters. Cruwys News. December 5. Available online: https://cruwys.blogspot.com/2015/12/my-thoughts-on-dna-cymru-part-3-and.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- King, Turi E., Gloria Gonzalez Fortes, Patricia Balaresque, Mark G. Thomas, David Balding, Pierpaolo Maisano Delser, Rita Neumann, and et al. 2014. Identification of the Remains of King Richard III. Nature Communications 5: ncomms6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivisild, Toomas. 2015. Maternal Ancestry and Population History from Whole Mitochondrial Genomes. Investigative Genetics 6: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klopfstein, Seraina, Mathias Currat, and Laurent Excoffier. 2006. The Fate of Mutations Surfing on the Wave of a Range Expansion. Molecular Biology and Evolution 23: 482–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, Ewan. 2015. Another DNA Controversy Facing Borders-Based Partnership. Not Just Sheep and Rugby. November 30. Available online: http://notjustsheepandrugby.blogspot.com/2015/11/another-dna-controversy-facing-borders.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Lamb, Ewan. 2017. Britain’sDNA—A Thing of the Past! Not Just Sheep and Rugby. July 21. Available online: http://notjustsheepandrugby.blogspot.com/2017/07/britainsdna-thing-of-past.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Langley, Chris, and Stuart Parkinson. 2009. Science and the Corporate Agenda; Lancaster: Scientists for Global Responsibility. Available online: http://www.sgr.org.uk/publications/science-and-corporate-agenda (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Lucotte, Gerard, Thierry Thomasset, and Peter Hrechdakian. 2011. Haplogroup of the Y Chromosome of Napoléon the First. Journal of Molecular Biology Research 1: 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, Fiona. 2013. Expensive Tests Claiming to Trace Person’s Ancestry Are as Dubious as Astrology, Warn Scientists. Mail Online. March 7. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2289400/Expensive-tests-claiming-trace-persons-ancestry-dubious-astrology-warn-scientists.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- McGinty, Stephen. 2012. Scotland’s DNA: Descended from Lost Tribes… and Related to Napoleon. The Scotsman. April 17. Available online: http://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/scotland-s-dna-descended-from-lost-tribes-and-related-to-napoleon-1-2238030 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- McKie, Robin. 2012. DNA Project Reveals Tom Conti’s Napoleonic Blood and Rich Roots of Scotland’s Genetic Legacy. The Observer. April 14. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/apr/14/tom-conti-napoleon-bonaparte-genes (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Menozzi, P., A. Piazza, and L. Cavalli-Sforza. 1978. Synthetic Maps of Human Gene Frequencies in Europeans. Science 201: 786–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, Anna. 2013. Attention The Times: Prince William’s DNA Is Not a Toy. The Conversation. June 14. Available online: http://theconversation.com/attention-the-times-prince-williams-dna-is-not-a-toy-15216 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Moffat, Alistair. 2011a. Scotland’s DNA: In Search of Our Roots. The Scotsman. November 30. Available online: http://www.scotsman.com/news/scotland-s-dna-in-search-of-our-roots-1-1988581 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Moffat, Alistair. 2011b. The Day I Discovered That I’m an Englishman. The Scotsman. November 30. Available online: http://www.scotsman.com/news/the-day-i-discovered-that-i-m-an-englishman-1-1988582 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Moffat, Alistair. 2011c. The Norse Code. The Scotsman, December 3. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, Alistair. 2012. Britain’s Last Frontier: A Journey along the Highland Line. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, Alistair. 2018. Alistair Moffat’s Personal Website. Available online: http://www.alistairmoffat.co.uk (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Moffat, Alistair, and Jim Wilson. 2011. The Scots: A Genetic Journey. Edinburgh: Birlinn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nature editorial. 2012. Time for Libel-Law Reform. Nature 464: 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nature editorial. 2013. The Right to Speak Out. Nature News and Comment 496: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nielsen, Rasmus, and Mark A. Beaumont. 2009. Statistical Inferences in Phylogeography. Molecular Ecology 18: 1034–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novembre, John, and Matthew Stephens. 2008. Interpreting Principal Component Analyses of Spatial Population Genetic Variation’. Nature Genetics 40: 646–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Conor, Lottie. 2015. Retirement? No Thanks. Meet the 60-Something Entrepreneurs. The Guardian. November 2 sec. Guardian Small Business Network. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/small-business-network/2015/nov/02/retirement-meet-the-60-something-entrepreneurs (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Panchal, Mahesh, and Mark A. Beaumont. 2007. The Automation and Evaluation of Nested Clade Phylogeographic Analysis. Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution 61: 1466–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panofsky, Aaron, and Joan Donovan. 2017. When Genetics Challenges a Racist’s Identity: Genetic Ancestry Testing among White Nationalists. SocArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Hans Peter, Dominique Brossard, Suzanne de Cheveigné, Sharon Dunwoody, Monika Kallfass, Steve Miller, and Shoji Tsuchida. 2008. Science Communication. Interactions with the Mass Media. Science 321: 204–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, Hans Peter. 2013. Gap between Science and Media Revisited: Scientists as Public Communicators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences United States of America 110: 14102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, Hans Peter. 2014. Scientists as Public Experts. Expectations and Responsibilities. In Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, 2nd ed. Edited by Massimiano Bucchi and Brian Trench. London: Routledge, pp. 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Petrone, Justin. 2014. ScotlandsDNA Targeting UK, Irish Ancestry Testing Markets with New Array-Based Services. GenomeWeb. January 28. Available online: https://www.genomeweb.com/arrays/scotlandsdna-targeting-uk-irish-ancestry-testing-markets-new-array-based-service (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- PHG Editorial Staff. 2013. Public Invasion of Genetic Privacy for UK Royal Family? PHG Foundation. June 17. Available online: http://www.phgfoundation.org/news/public-invasion-of-genetic-privacy-for-uk-royal-family (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Phillips, Andelka M. 2016. Only a Click Away—DTC Genetics for Ancestry, Health, Love … and More: A View of the Business and Regulatory Landscape. Applied & Translational Genomics 8: 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickrell, Joseph K., and David Reich. 2014. Toward a New History and Geography of Human Genes Informed by Ancient DNA. Trends in Genetics: TIG 30: 377–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plagnol, Vincent. 2012. Exaggerations and Errors in the Promotion of Genetic Ancestry Testing. Genomes Unzipped. December 17. Available online: http://genomesunzipped.org/2012/12/exaggerations-and-errors-in-the-promotion-of-genetic-ancestry-testing.php (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Private Eye Reporter. 2013a. Private Eye Reporter. 2013a. Street of Shame. Private Eye no. 1345 (26 July–8 August): 7. [Google Scholar]

- Private Eye Reporter. 2013b. Brittle Myths Moffat. Private Eye no. 1348 (6–19 September): 31. [Google Scholar]

- Private Eye Reporter. 2014. Media News. Private Eye no. 1361 (7–20 March): 13. [Google Scholar]

- Private Eye Reporter. 2015a. Ancestral Vices. Private Eye no. 1387 (6–19 March): 30. [Google Scholar]

- Private Eye Reporter. 2015b. Genealogy. Private Eye no. 1394 (12–25 June): 35. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, John. 2016. Confidence and the Genealogical Proof Standard. Anglo-Celtic Roots Quarterly Chronicle 22: 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Martin. 2003. Beware the Gene Genies. The Guardian. February 21. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/education/2003/feb/21/highereducation.uk (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Richards, Martin, and Vincent Macaulay. 2013. It Is Unfair to Compare Genetic Ancestry Testing to Astrology. The Guardian. April 8. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2013/apr/08/unfair-genetic-ancestry-testing-astrology (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Rogers, A. R., and H. Harpending. 1992. Population Growth Makes Waves in the Distribution of Pairwise Genetic Differences. Molecular Biology and Evolution 9: 552–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rohde, Douglas L. T., Steve Olson, and Joseph T. Chang. 2004. Modelling the Recent Common Ancestry of All Living Humans. Nature 431: 562–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, Tom. 2013. Are You Related to Cleopatra? Or Are Genealogists Fishing in the Nile? The Telegraph. March 8. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/science/9917945/Are-you-related-to-Cleopatra-Or-are-genealogists-fishing-in-the-Nile.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Royal, Charmaine D., John Novembre, Stephanie M. Fullerton, David B. Goldstein, Jeffrey C. Long, Michael J. Bamshad, and Andrew G. Clark. 2010. Inferring Genetic Ancestry: Opportunities, Challenges and Implications. American Journal of Human Genetics 86: 661–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Science and Technology Committee, House of Commons. 2017. Science Communication and Engagement: Eleventh Report of Session 2016–17; London: House of Commons. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmsctech/162/162.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Scottish Tapestry. 2018. Scottish Tapestry: Who’s Involved? Available online: http://scotlandstapestry.com/index.php?s=about (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Scully, Marc, Steven D. Brown, and Turi King. 2016. Becoming a Viking: DNA Testing, Genetic Ancestry and Placeholder Identity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 162–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, Marc, Turi King, and Steven D. Brown. 2013. Remediating Viking Origins: Genetic Code as Archival Memory of the Remote Past. Sociology 47: 921–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sense About Science. 2013. Sense about Genetic Ancestry Testing. Sense About Science. Available online: http://archive.senseaboutscience.org/pages/genetic-ancestry-testing.html (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Shriver, Mark D., and Rick A. Kittles. 2004. Genetic Ancestry and the Search for Personalized Genetic Histories. Nature Reviews. Genetics 5: 611–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Simon. 2010. The Expensive Lessons of Libel. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies 15: 194–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Simon. 2011. How English Libel Law Has a Global Chill on Free Speech. Cortex 47: 643–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Source BioScience 2015. Annual Report and Accounts for the Year Ended 31 December 2015; Nottingham: Source BioScience. Available online: https://www.sourcebioscience.com/media/1020/sbs-annual-report-2015.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Southern Reporter editorial staff. 2012. DNA Project Proves We Are All Jock Tamson’s Bairns Afterall. Southern Reporter. April 24. Available online: http://www.thesouthernreporter.co.uk/news/dna-project-proves-we-are-all-jock-tamson-s-bairns-afterall-1-2252619 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Southern Reporter editorial staff. 2013. Borders-Based DNA Researchers Help Comic Izzard Trace Ancestors. Southern Reporter. February 21. Available online: http://www.thesouthernreporter.co.uk/news/borders-based-dna-researchers-help-comic-izzard-trace-ancestors-1-2801110 (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Speed, Doug, and David J. Balding. 2015. Relatedness in the Post-Genomic Era: Is It Still Useful? Nature Reviews. Genetics 16: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, Alan R., Eric Routman, and Christopher A. Phillips. 1995. Separating Population Structure from Population History: A Cladistic Analysis of the Geographical Distribution of Mitochondrial DNA Haplotypes in the Tiger Salamander, Ambystoma Tigrinum. Genetics 140: 767–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- THE editorial staff. 2014. The Week in Higher Education. Times Higher Education (THE). March 27. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/the-week-in-higher-education-27-march-2014/2012242.article (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Thomas, Mark G. 2013. To Claim Someone Has “Viking Ancestors” Is No Better than Astrology. The Guardian. February 25. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2013/feb/25/viking-ancestors-astrology (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Thomas, Mark G., Toomas Kivisild, Lounes Chikhi, and Joachim Burger. 2013. Europe and Western Asia: Genetics and Population History. In The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. Edited by Immanuel Ness and Peter Bellwood. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/mace-lab/publications/articles/2013/wbeghm818.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Van Oven, Mannis. 2015. PhyloTree Build 17: Growing the Human Mitochondrial DNA Tree. Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series 5: e392–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oven, Mannis, and Manfred Kayser. 2009. Updated Comprehensive Phylogenetic Tree of Global Human Mitochondrial DNA Variation. Human Mutation 30: E386–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oven, Mannis, Anneleen Van Geystelen, Manfred Kayser, Ronny Decorte, and Maarten H. D. Larmuseau. 2014. Seeing the Wood for the Trees: A Minimal Reference Phylogeny for the Human Y Chromosome. Human Mutation 35: 187–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, Harriet. 2011. Unravelling the Genetic Ancestry of the Scots. BioNews. March 7. Available online: http://www.bionews.org.uk/page_90334.asp (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Wilson, Jim. 2013. Response to “Exaggerations and Errors in the Promotion of Genetic Ancestry Testing”. Genomes Unzipped. January 3. Available online: http://genomesunzipped.org/2013/01/response-to-exaggerations-and-errors-in-the-promotion-of-genetic-ancestry-testing.php (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Y Chromosome Consortium. 2002. A Nomenclature System for the Tree of Human Y-Chromosomal Binary Haplogroups. Genome Research 12: 339–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Searched Domain | Online Newspaper | Number of DNA Articles | Number Mentioning BritainsDNA | Number Mentioning any other DNA Ancestry Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| www.telegraph.co.uk | The Telegraph | 241 | 3 | 4 |

| www.independent.co.uk | The Independent | 146 | 0 | 2 |

| www.theguardian.com | The Guardian | 269 | 3 | 12 |

| www.scotsman.com | The Scotsman | 24 | 13 | 1 |

| www.walesonline.co.uk | WalesOnline | 20 | 11 | 1 |

| Date | Radio Station | Programme |

|---|---|---|

| 2 March 2011 | BBC Radio 4 | Today programme with James Naughtie |

| 1 June 2011 | BBC Radio 4 | Today programme with James Naughtie |

| 7 November 2011 | BBC Radio Scotland | Tom Morton |

| 8 December 2011 | BBC Radio Scotland | MacAulay and Co |

| 1 March 2012 | BBC Radio Scotland | MacAulay and Co |

| 17 April 2012 | BBC Radio Scotland | MacAulay and Co |

| 9 July 2012 | BBC Radio 4 | Today programme with James Naughtie |

| 11 July 2012 | BBC Radio Scotland | Tom Morton |

| 30 August 2012 | BBC Radio 2 | Jeremy Vine |

| 26 September 2012 | BBC Radio Scotland | Tom Morton |

| 7 November 2012 | BBC Radio Scotland | Tom Morton |

| 8 November 2012 | BBC Three Counties Radio | Roberto Perrone |

| 9 November 2012 | BBC Radio Scotland | Call Kaye |

| 25 March 2013 | BBC Radio Scotland | John Beattie Programme |

| 6 March 2014 | BBC local radio | Mark Forrest Show |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kennett, D.A.; Timpson, A.; Balding, D.J.; Thomas, M.G. The Rise and Fall of BritainsDNA: A Tale of Misleading Claims, Media Manipulation and Threats to Academic Freedom. Genealogy 2018, 2, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2040047

Kennett DA, Timpson A, Balding DJ, Thomas MG. The Rise and Fall of BritainsDNA: A Tale of Misleading Claims, Media Manipulation and Threats to Academic Freedom. Genealogy. 2018; 2(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2040047

Chicago/Turabian StyleKennett, Debbie A, Adrian Timpson, David J. Balding, and Mark G. Thomas. 2018. "The Rise and Fall of BritainsDNA: A Tale of Misleading Claims, Media Manipulation and Threats to Academic Freedom" Genealogy 2, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2040047

APA StyleKennett, D. A., Timpson, A., Balding, D. J., & Thomas, M. G. (2018). The Rise and Fall of BritainsDNA: A Tale of Misleading Claims, Media Manipulation and Threats to Academic Freedom. Genealogy, 2(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2040047