Abstract

Thomas Laqueur argues that the work of the dead is carried out through the living and through those who remember, honour, and mourn. Further, he maintains that the brutal or careless disposal of the corpse “is an attack of extreme violence”. To treat the dead body as if it does not matter or as if it were ordinary organic matter would be to deny its humanity. From Laqueur’s point of view, it is inferred that the dead are believed to have rights and dignities that are upheld through the rituals, practices, and beliefs of the living. The dead have always held a place in the space of the living, whether that space has been material and visible, or intangible and out of sight. This paper considers ossuaries as a key site for investigating the relationships between the living and dead. Holding the bones of hundreds or even thousands of bodies, ossuaries represent an important tradition in the cultural history of the dead. Ossuaries are culturally constituted and have taken many forms across the globe, although this research focuses predominantly on Western European ossuary practices and North American Indigenous ossuaries. This paper will examine two case studies, the Sedlec Ossuary (Kutna Hora, Czech Republic) and Taber Hill Ossuary (Toronto, ON, Canada), to think through the rights of the dead at heritage sites.

1. Introduction

“We endlessly invest the dead body with meaning because, through it, the human past somehow speaks to us.”1—Thomas Laqueur

In The Work of the Dead, Thomas Laqueur opens with a recount of Diogenes the Cynic who, during Greek times, had ordered that his body be carelessly thrown away after his death and left unburied. Diogenes’ rationale was that he would be gone and his dead body would not have the capacity to care what happened to it. Laqueur counters this by asking, do the dead matter? Does the dead body matter? He argues yes.

Laqueur argues that the work of the dead is carried out through the living and through those who remember, honour, and mourn. Further, he maintains that the brutal or careless disposal of the corpse “is an attack of extreme violence”.3 To treat the dead body as if it does not matter or as if it were ordinary organic matter would be to deny its humanity. From Laqueur’s point of view it is inferred that the dead are believed to have rights and dignities that are upheld through the rituals, practices, and beliefs of the living.It matters in disparate religious and ideological circumstances; it matters even in the absence of any particular belief about a soul or how long it might linger around its former body or about what might become of it after death; it matters across all sorts of beliefs about an afterlife or God. It matters in the absence of such beliefs. It matters because the living need the dead far more than the dead need the living. It matters because the dead make social worlds. It matters because we cannot bear to live at the borders of our mortality.2

The dead have always held a place in the space of the living, whether that space has been material and visible, or intangible and out of sight. This paper considers ossuaries as a key site for investigating the relationships between the living and dead. Holding the bones of hundreds or even thousands of bodies, ossuaries represent an important tradition in the cultural history of the dead. Ossuaries are culturally constituted and have taken many forms across the globe, although this research will focus predominantly on Western European ossuary practices and North American Indigenous ossuaries. This paper will examine two case studies, the Sedlec Ossuary (Kutna Hora, Czech Republic) and Taber Hill Ossuary (Toronto, ON, Canada), to think through the rights of the dead at heritage sites. What is it that draws tourists to burial grounds, and how do heritage sites negotiate visitor experiences? What are the ethical boundaries when a final resting place with bodies on display is also marketed as a tourist site? Do the dead have human rights, and how are the living responsible for preserving those rights?

2. Sedlec Ossuary

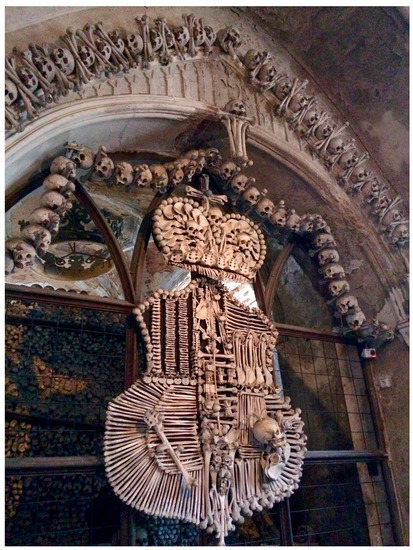

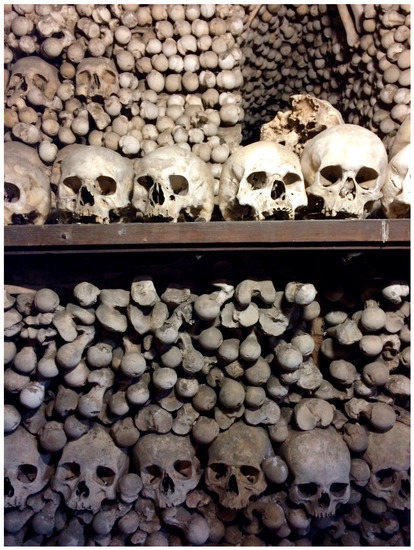

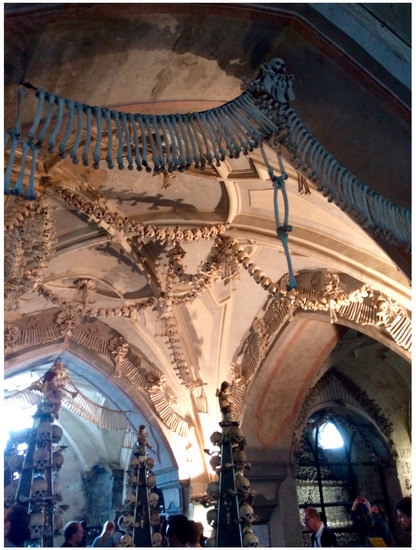

The Sedlec Ossuary, more commonly referred to as the bone church, is located just outside of Prague, Czech Republic. After a research trip to Poland in the spring of 2016, I was backpacking through Eastern Europe and found myself at Sedlec. It’s famous among tourists and locals, and numerous tours leave Prague every day to the small city of Kutna Hora, where the church is located. The bone church contains the bones of approximately 40,000 people who were originally buried on church grounds between the 14th to 17th century, a large number of whom died from the plague which devastated the town in 1378. The gothic church on site was built in 1400, and the bones buried on the church grounds were exhumed and installed in the interior in 1870 by Frantisek Rindt, a local woodworker.4 Elizabeth Hallam notes that “in Europe, ossuaries have acted as repositories of bones since the 13th century in Catholic contexts, developing where the dead are given a temporary burial after which, once the flesh has decomposed, the skeleton is exhumed and placed in a dedicated building to communally house the remains, often in a graveyard or near a church.”5 The uncanny compilation of human bones in the form of crests, chandeliers, and sculptures at Sedlec has made the bone encrusted church particularly popular among modern tourists (see Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Sedlec Ossuary, crest of bones, interior, May 2016. Kelsey Perreault.

Figure 2.

Sedlec Ossuary, stacks of bones (close up), interior, May 2016. Kelsey Perreault.

Figure 3.

Sedlec Ossuary, bone memorial display, interior, May 2016. Kelsey Perreault.

Figure 4.

Sedlec Ossuary, ceiling decoration, and tourists, interior, May 2016. Kelsey Perreault.

Initially, my first task is to understand the phenomenon of dark tourism, and how ossuaries fall both inside and outside of its scope. Dark tourism is a term coined by John Lennon and Malcolm Foley that describes a (perceived) recent rise in tourist pilgrimage to sites of death, disaster, and atrocity in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.6 In Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster, Lennon and Foley use case studies of the sites of dead presidents, the death camps of Poland, war sites of the first and second world wars, and the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, to think through what it is that attracts tourists to these modern pilgrimage sites. They argue that “the politics, economies, sociologies, and technologies of the contemporary world are as much important factors in the events upon which dark tourism is focused as they are central to the selection and interpretation of sites and events which become tourist products.”7 Dark tourist sites have similarly been broken down by Stone and Sharpley to describe a number of modern tourist experiences, including the witnessing of re-enactments of death, and pilgrimage to all sites of death, internment, and memorial.8

Evidently, ossuaries, charnel houses, and catacombs can be enveloped under this umbrella of dark tourism that encompasses a range of experiences and representations of death. However, I would like to unpack the notion of “dark” within dark tourism a bit further and question if the representations of death at ossuaries are in fact “dark”. In this, my line of questioning aligns with Bowman and Pezzullo’s arguments in their article “What’s so ‘Dark’ about ‘Dark Tourism’?” They take issue with Lennon and Foley’s nomenclature, considering the unmistakable negative valence attached to the term “dark” in Western cultures. Bowman and Pezzullo posit that:

Further, they argue that to accept Lennon and Foley’s naming of certain destinations as dark, and others as heritage, would mean accepting a binary distinction between tragedy and heritage.10 However, the two are not mutually exclusive categories and to name a site as one or the other risks undermining important histories and cultural values.11the trope of “dark” works to create the reality it purports merely to describe. In refusing to interrogate the term, scholars have also refused to identify and to interrogate the assumptions such language entails. By labeling certain tourists and tourist sites “dark”, an implicit claim is made that there is something disturbing, troubling, suspicious, weird, morbid, or perverse about them, but what exactly that may be remain elusive and ill-defined because no one has assumed the burden of proving it.9

So how are we to interpret ossuaries? They have commonly been described as memento mori, (reminders of death) that force their spectators to reflect on their own mortality. Paul Koudounaris notes however that to understand them as memento mori may no longer apply, since the context in which we understand death has shifted significantly and has altered their message.12 He suggests that:

The sacred nature of ossuaries and their message of hope is often difficult to grasp for the modern visitor. Koudounaris points to the post-Enlightenment era as a significant paradigm shift. A heightened preoccupation with hygiene and transmission of disease resulted in efforts to clean up churchyards and cemeteries and to keep a safe distance between the living and the dead. There was a new understanding of the dead as highly contaminated and their presence inside sacred sites such as churches was mostly abandoned.15 Thus, the proliferation of ossuaries at its peak was understood as a symbol of hope and as spaces of purity. Post-enlightenment and in our contemporary context, these displays of bones inside churches and chapels are more often viewed as strange, dark, and disturbing.What we call memento mori is perhaps something more along the lines of timor mortis13: instead of simply reminding us of our own mortality, death tends to provoke fear. We should understand that the bone houses of centuries past were sacred sites, and many incorporated chapels for worship, making them places not of fear, but of eschatological hope.14

However, many ossuaries actually served as early memorials and sites of commemoration. Again, this is difficult for the modern viewer to understand, because Western contemporary memorial practices most often render bodies invisible. Koudounaris reveals that “the first structures to be decorated with human remains were, in fact, military tributes, and the desire to create a memorial from the bones of those who have been massacred has continued into the modern era.” One recent example given is the Cambodian genocide memorial which features 5000 skulls that were recovered from the killing fields. Regardless, the draw for contemporary tourists to ossuaries has little to do with memorialization or remembrance of the dead. Western cultural norms prescribe that corpses and bones should not be looked at, and moreover, cultural taboos keep dead bodies out of the public sphere. Cultural taboos around not looking at dead bodies are what make looking at the bones of ossuaries such a spectacle for tourists. They are called to look at exactly what they are not supposed to look at.

Jessica Auchter explains this further in her article “On looking: the politics of looking at the corpse”. Auchter describes,

I know from my own experience visiting Sedlec that visitors are faced with a similar paradox inside the bone church. I had come to Sedlec after a two-week intensive research trip in Poland visiting Holocaust memorials and death camps. In Poland, the bodies are concealed; they are ashes buried underground and beneath the memorials, except at Majdanek Concentration Camp, where the ashes are piled high under a massive obelisk and to look upon the ashes makes visible the magnitude of loss in a way that overshadows all the other monuments. To look at ashes is still a remarkably different experience than to look at bones which are materially and visually more human, which is why the bone church was so troubling to me as a researcher. I walked around Sedlec and was caught off guard by the number of human bones on display; human bones that were close enough to touch, human bones that tourists could take selfies with, human bones that had been commoditized as memorabilia in the entrance gift shop. I could understand the appeal to witness a place like Sedlec. After all, I had been drawn there as a tourist as well. The irony is not lost on me that, as I snapped photographs on my phone, I was a participant in the very thing that I sought to critique. This begins to drive home the point that it is difficult to grasp the real intentions, thoughts, and feelings of the visitors to these spaces. From the outside, I looked just like every other tourist; however, as a researcher invested in memory and memorial practices, there were pertinent ethical questions that I had to ask to begin to untangle this uncertain relationship between the living and dead.When I visited the genocide memorials in Rwanda several years ago, I traveled to multiple memorial sites where bones and bodies were on display. When you see these bodies and bones, you don’t know if you should look. You are there to look, indeed these sites are designed to be visually and physically engaged with, as you traverse rooms full of mummified corpses. But somehow it seems shameful to just look.16

The first being, what is the role of the tourist in all of this? It seems modern tour groups to sites of death inevitably require far less extensive planning, time, and commitment than pilgrimages to similar sites in the past. Inevitably this has led to a bad rapport with tourists, and Lennon and Foley come to understand this as evidence of the intense commodification of dark tourist destinations. Alternatively, Bowman and Pezzullo caution against what can only be described as ‘tourist shaming’ that results from misunderstanding other people’s attitudes, behaviour, or motives for visiting sites of death.17 Research among scholars has made clear that tourist motives and responses are widely varied. “Some wish to mourn for ancestors lost in what they would consider to be a sacred site, some pay for a guide to learn about what they perceive to be a telling moment in history, and some remain unmoved due to boredom, antipathy, apathy, or preoccupation with someone or something else. Some visit memorials weekly, annually, once in a lifetime, or never at all.”18 Ethical debates over the proper way to mourn, learn, or engage with these sites ignore the reality that “responses to death are culturally bound and historically variable.”19

The mass attraction of tourists to these sites of death reaffirms Thomas Laqueur’s argument that the dead do indeed matter, but how they matter is more difficult to unravel. How and if the dead matter at Sedlec is made even more precarious as an increasing number of tourists enter their space of rest. Are these bones seen as a reminder of the visitors’ own mortality? Are they mourned or simply propped up as a spectacle of macabre display? Are they made invisible through their abstraction in the form of decoration and sculpture? While I cannot attempt to know the possible reasons and interpretations of all tourists who pass through Sedlec, I do raise a moral question over whether this site and others like it should be open to the public, or if access should be further mediated. To resist a narrative of tourist shaming, instead, I ask: what ethics are at stake when places of death become enmeshed in commodities of global tourism? Should certain sites, specifically resting places for the dead, be off limits? Do the dead have human rights, and what constitutes a violation of those rights?

3. Human Rights of the Dead

The concept of the human rights of the dead is highly contested and debated. Arguments for the rights of the dead are most often situated in the fields of law and medical ethics, but are gaining traction in the field of forensic humanitarianism. I would like to focus my attention on forensic humanitarianism because it deals more closely with the rights of the dead post-burial and post-trauma. International humanitarian law (IHL) emerged concurrently with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the post-1945 international legal regime. IHL, and human rights and refugee law, affirm and activate the rights of peoples affected by disaster and conflict, as well as the responsibilities of humanitarian workers who seek to intervene. Forensic humanitarianism merges the fields of scientific forensics and humanitarianism.20

There are two objectives of this work. First, forensic humanitarians work to identify human remains and determine the cause of their death, sometimes to serve as evidence in legal cases of violence and crime. Secondly, to fulfil humanitarian potential by ‘“protecting the dignity of the dead” and “addressing the needs of the bereaved”.’21 Claire Moon details how the use of DNA and skeletal analysis have been used by forensic anthropologists to establish the identities of victims of atrocities, and reconnect their remains to their families. Moon cites the International Commission on Missing Persons in Bosnia, as well as truth commissions in South Africa and Argentina as just a few of the organizations undertaking this type of humanitarian work globally.22 The desire to identify the dead and protect their dignity can be seen as a way that the living act as though the dead have human rights.

Moon posits that,

Evidently, the dead cannot be rights holders or claimers in the same sense as the living. They do not have inalienable human rights in the traditional sense that is outlined for the living in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Rather, Moon argues that the dead are rights holders insofar as the living treat them as though they have rights and dignity. The dead are reliant on the living to uphold the care and respect of their corpses. Adam Rosenblatt agrees in his stance that “dead bodies can ‘speak’ to us, but cannot really contest the choices we make for them. The dead body’s agency is a shadow of our agency: not only weaker, but also entirely subject to our visions and our actions.”24we can assert that the dead have human rights insofar as people act as though they have rights. That is to say that insofar as there are social conventions and customs that confer rights (and human rights) upon the dead, and insofar as these conventions shape social practices, then the claim can be sustained. After all, human rights is as much a practical activity as it is one of principle and we can argue that human rights “exist” in the world insofar as people behave in accordance, and can be observed to behave in accordance, with the principles it sets out.23

Agency given to the dead is also culturally bound and is not always an outcome of respect for the dead. Rosenblatt elaborates,

With this in mind, I would like to return to my first case study of Sedlec Ossuary and think through cultural customs of the dead in European ossuaries more broadly.Anthropological evidence does clearly show that every culture has a set of customs for the dead. But in some societies these customs may be conducted out of respect for many things besides the dead: reverence for tradition—the sense that a particular practice is “what our people have always done”—or even out of fear (which can be a special form of respect) that the improperly buried dead would haunt their descendants and disorder the world. It is far more difficult to see all of these motives emanating from a shared concept of dignity.25

Ossuaries and catacombs were often constructed when burial space was scarce or limited. In Sedlec, the town of Kutna Hora now sits on much of what was originally the burial grounds of those who are now placed inside the church. The graves that were exhumed spanned over three centuries, which makes it difficult to discern what their final wishes were and what they would have consented to. Their exhumation, unlike the digging conducted by modern forensic anthropologists, was a practical procedure, and often disregarded the need to identify individual bones or keep them separate.26 I have to imagine that these people would have never imagined that their bones would end up decorating the inside of the church, drawing in thousands of tourists per year. Similarly, the roughly six million people who rest in the Paris Catacombs likely never imagined their final burial location as a tourist attraction that conjures up lines nearly two hours long. Regardless, these locations exist out of both practicality and cultural customs of the period, and we are left to grapple with their presence and meaning. The popularity of ossuaries and catacombs across Europe as alternative or dark tourist experiences raises the question of whether these sites educate or desensitize the visitor. Is the humanity of these individuals lost in the mass scale of these piles of bones?

Following Laqueur’s argument that the dead do work through the living, I ask, what is the relationship between the living and the dead at ossuaries? As these individuals have passed from living to historical memory, we can assume that they are no longer being mourned by the living. At Sedlec, people arrive on buses from tour groups but their visits to the ossuary are largely unmediated. They pay a small entrance fee and are free to roam the space. They are also invited to purchase bone memorabilia (skull cups, mugs, shot glasses) from a gift shop at the door or from the small tourist store across the street. The dead are not only on display as objects of the tourist gaze, but they are commoditized and sold through cheap souvenirs. Jane Brown notes in her essay on dark tourism shops that because dark tourism sites display difficult subject matter, they have often been accused of trading off the memory of death and disaster. Further, “The perennial presence of gift shops, be they staid, educationally focused bookshops or lavish retail meccas to the macabre, compounds this accusation. There is a generalized distaste that surrounds the criticism of such shops.”27 I posit that the root of these critiques stems from more than just general distaste, and can be connected to cultural values of treatment and care for the dead. The presence of commercial gift shops at dark tourism sites is viewed as distasteful because it contradicts the sanctity of space which we reserve and attach to spaces of the dead.

At some point, the need to draw in tourists to Kutna Hora was seen as a greater priority than the preservation of the sanctity of the Church of All Saints which houses Sedlec Ossuary. If Moon and Rosenblatt place the defense of rights and dignities of the dead in the hands of the living, does the disruption of this sacred space disregard the rights of the dead? Similarly, is the presence of a gift shop a violation of their dignity? Although these dark tourist sites have been operating for decades and their supply and demand continues to grow, I suggest that we take a step back to more carefully consider the implications of access to these locations. This line of questioning led me to search for ossuaries that mediated the interaction between the living and dead in more explicit forms, installing more distance between the visitor and the bodies put to rest. I stumbled upon a site much closer to home in Scarborough, Ontario (Canada) that garnered significant attention when it was unearthed by a construction crew in the 1950s.

4. Taber Hill Ossuary

While masses of North American tourists flock to ossuaries and catacombs in Europe, there is an extensive history of ossuary practices by First Nations communities on North American soil. On August 17, 1956, while work was being done to level farmland to make way for a new subdivision, a shovel dug into the side of Taber Hill and uncovered a mass burial pit filled with bones. Construction stopped immediately and steps were taken by archaeological experts that inevitably identified the site as a First Nations burial pit. Further examinations of the land also led to the discovery of a second, smaller burial site. Just eleven days after discovering the ossuaries, plans were put in motion to host a large event to rebury the bones according to the traditional Feast of the Dead ceremony.28 This ancient Iroquois burial ceremony had not been performed in Ontario for several hundred years, at least since the early seventeenth-century, likely in response to Canada’s colonization and the condemnation of the ceremony by European settlers.29 In an account of the Taber Hill Feast of the Dead, it is noted that “this was forgotten and the Iroquois were invited to perform the ritual with the support of members of three levels of Canadian Government. The Reeve of Scarboro spoke, almost as presiding master of ceremonies. Officials of the Province of Ontario were present, as well as the Federal Minister of Citizenship and Immigration who spoke in his capacity as the Minister responsible for Indian Affairs.”30 This cooperation between Governmental bodies and the Indigenous communities was unprecedented in many ways, and likely concealed subjugation and genocidal systems across the Nation that were occurring simultaneously.31

Consequently, Taber Hill may indicate how European contact led to changing beliefs and attitudes towards ossuary burials and the resulting disappearance of Indigenous Feasts of the Dead. The heritage site that exists today on Taber Hill does not signpost the conflicting ontologies of mortuary customs that forced Indigenous burial practices to shift under British and French colonization, nor does it make note of the legacy of grave robbing that can account for the collection of Indigenous bones and bodies that found their way into museums, such as the Royal Ontario Museum which collected bones from the Ossossané Ossuary in the 1940s. The Toronto Heritage plaque that marks out the grave today reads:

The plaque is mounted on a large stone that is situated at the top of Taber Hill. The grass on the hill is neatly groomed and appears like a park, while the plaque is the only indication that this hill is, in fact, a mass burial mound. This brief historical description is more political than it may first appear. Its dedication by the township of Scarborough takes agency from the descending Indigenous tribes to whom the bones actually belong. The uncovering of the site by white people rewrites this story as a white savior narrative, one that overrides the Indigenous story of ossuary customs and their cultural beliefs in the afterlife.Taber Hill: Site of an ancient Indian ossuary of the Iroquois Nation. Burials were made about 1250 A.D. This ossuary was uncovered when farmlands were developed into residential properties in 1956. This common grave contains the remains of approximately 472 persons. Dedicated as a historical site by the township of Scarborough 21 October, 1961.32

My initial research of Taber Hill sought out an alternative strategy for mediating the historical sites of ossuaries to that employed at Sedlec and those like it across Europe. I hypothesized that reburying the dead and keeping a distance between the living and the dead might be a more appropriate avenue of honouring the rights of the dead. It appears that whether the bones are on display or not may not be the crux of the problem. The display of bones at Sedlec is a result of the cultural customs at its time of construction in Eastern Europe, just as the burial of the bones at Taber Hill is an indication of Indigenous cultural traditions on Turtle Island. Neither is right or wrong, and removing stigmas of morality around the treatments of bones is the first step in understanding ossuaries and engaging with the dead at these sites in respectful ways. Bones on display can be the object of prayer, or remembrance, fascination, or voyeurism, depending on the visitor. Without a mediating form of education on the cultural customs of the dead and the beliefs that led to their installment, visitors may not see the bones as human at all, which can be problematic. In spaces where the bones are concealed, even more importance falls on mediating forms such as plaques or monuments to pay tribute to the bodies that rest there, especially at mass graves where lives are counted as grand total sums rather than as individuals. In the case of Taber Hill, the plaque reveals very little about the history of the people, the customs of ossuaries or the Feast of the Dead. This is comparably problematic.

5. Future Consideration

The literature on the rights of the dead places the sole responsibility in the hands of the living. A brief look at ossuaries indicates that perhaps we are falling short of making these spaces both sacred and educational. Sedlec Ossuary and Taber Hill offered rich case studies to think through the topics of dark tourism and the human rights of the dead. However, I predict that my initial research here has merely laid the groundwork to examine a range of other controversial dark tourist sites. I have sketched the broad boundaries of what dark tourism encompasses and also challenged the division between what is considered dark and what is heritage. My case studies have called into question how we are caring for and upholding the rights of the dead at dark tourism sites. For future consideration I ask, how can we intervene in these spaces to make visitor interaction with the dead more meaningful, and respectful? How might we look at ossuaries to reconsider our living relationships with the dead and the ontologies of morality?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Auchter, Jessica. 2017. On Viewing: The Politics of Looking at the Corpse. Global Discourse 7: 223–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Michael S., and Phaedra C. Pezzullo. 2009. What’s so ‘Dark’ about ‘Dark Tourism’?: Death, Tours, and Performance. Tourist Studies 9: 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Jane. 2013. Dark Tourism Shops: Selling “Dark” and “Difficult” Products. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research 7: 272–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Alan. 2018. Taber Hill. Toronto’s Historical Plaques. Available online: http://torontoplaques.com/Pages/Taber_Hill.html (accessed on 2 June 2018).

- Hallam, Elizabeth. 2010. Articulating Bones: An Epilogue. Journal of Material Culture 15: 465–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information Gathered on Site and from the Church’s Tourist Website. 2017. Sedlec Ossuary. Available online: https://sedlecossuary.com/ (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Koudounaris, Paul. 2011. The Empire of Death: A Cultural History of Ossuaries and Charnel Houses. New York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Laqueur, Thomas Walter, and ProQuest. 2015. The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, J. John, and Malcolm Foley. 2010. Dark Tourism. New York and London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- McIlwraith, Thomas. F. 1958. Feast of the Dead: Historical Background. Anthropologica 6: 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Claire. 2014. Human Rights, Human Remains: Forensic Humanitarianism and the Human Rights of the Dead. International Social Science Journal 65: 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, Adam. 2010. International Forensic Investigations and the Human Rights of the Dead. Human Rights Quarterly 32: 921–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, Philip, and Richard Sharpley. 2008. Consuming Dark Tourism: A Thanatological Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research 35: 574–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wencer, David. 2015. Historicist: The Tabor Hill Ossuary. Torontoist. February 28. Available online: https://torontoist.com/2015/02/historicist-the-tabor-hill-ossuary/ (accessed on 2 June 2018).

| 1 | (Laqueur and ProQuest 2015, p. 5). |

| 2 | (Laqueur and ProQuest 2015, p. 1). |

| 3 | (Laqueur and ProQuest 2015, p. 4). |

| 4 | (Information Gathered on Site and from the Church’s Tourist Website 2017). |

| 5 | (Hallam 2010, p. 475). |

| 6 | (Lennon and Foley 2010, p. 3). |

| 7 | (Lennon and Foley 2010, p. 3). |

| 8 | (Stone and Sharpley 2008, p. 578). |

| 9 | (Bowman and Pezzullo 2009, p. 190). |

| 10 | Ibid. |

| 11 | I use dark tourism to contextualize Sedlec Ossuary as it is the most commonly accepted category. However, I also note that there may be other more useful terminology to describe the varied experiences at a site like Sedlec. |

| 12 | (Koudounaris 2011, p. 15). |

| 13 | Timor mortis translates to “fear of death disturbs me”. |

| 14 | (Koudounaris 2011, p. 15). |

| 15 | Ibid. |

| 16 | (Auchter 2017, p. 228). |

| 17 | (Bowman and Pezzullo 2009, p. 192). |

| 18 | Ibid. |

| 19 | (Bowman and Pezzullo 2009, p. 192). |

| 20 | (Moon 2014, p. 50). |

| 21 | (Moon 2014, pp. 50–51). |

| 22 | (Moon 2014, p. 51). |

| 23 | (Moon 2014, p. 58). |

| 24 | (Rosenblatt 2010, p. 935). |

| 25 | (Rosenblatt 2010, p. 939). |

| 26 | Hallam notes that some ossuaries did label and give priority to maintaining individual identity of the dead. This wasn’t as common. |

| 27 | (Brown 2013, p. 272). |

| 28 | (Wencer 2015). |

| 29 | (McIlwraith 1958, pp. 83–86). |

| 30 | Ibid, p. 85. |

| 31 | It is critical to note that Indian Residential Schools were still operating during this period and the 60s Scoop of Indigenous children would have been almost concurrent with the unveiling of Taber Hill. |

| 32 | (Brown 2018). |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).