1. Introduction

Intercountry adoption (ICA) from Guatemala ceased at the end of 2007 after years of practices that were very often unethical, at the least, and at the worst were riddled with corruption and human rights abuses (

Nolan 2024;

Bunkers et al. 2009;

Bunkers and Groza 2012;

Monico et al. 2022). ICA began during the civil war years (1960–1996) (

Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica [REMHI] [Recovery of the Historical Memory] 1999); it was seen at the time as a humanitarian solution for orphans of the civil war, which then turned into an aggressive ICA system in the post-conflict years (

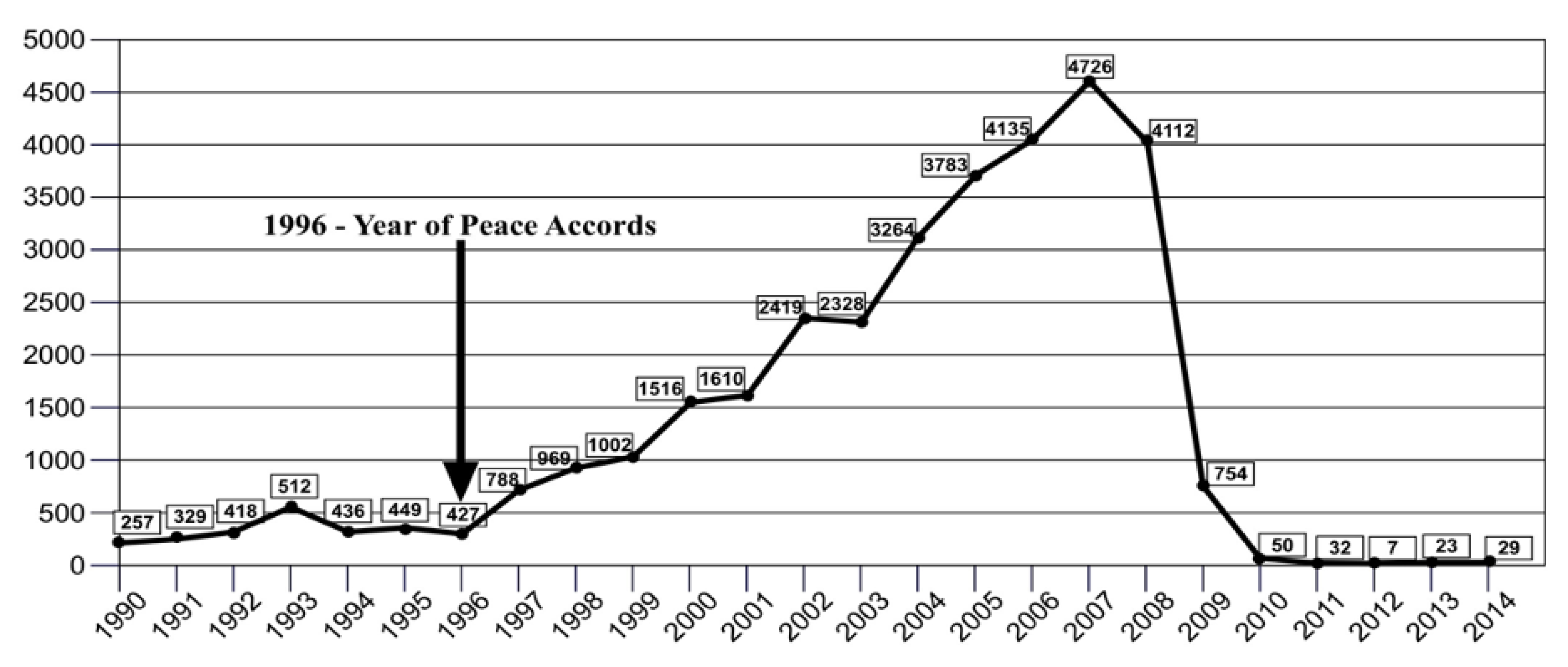

Dubinsky 2010). Eventually, a surge in ICAs resulted in the placement of 1516 children with families in the United States (U.S.) in 2000. This number grew to a peak of 4726 children being placed with families from the U.S. in 2006 before the system went into a steep decline due to a self-imposed moratorium to reform the system (

Monico 2013). In sum, 27,893 Guatemalan children were placed into ICA with U.S. families from 2000 to 2008. This era has been characterized as the millennium adoption surge (

Rotabi and Bromfield 2017). What began as war years “orphan rescue”—when there were already child rights concerns—became an even more questionable and dubious system in time. This was especially true after the turn of the millennium with thousands of Guatemalan children being adopted internationally on an annual basis (

Dubinsky 2010).

At its peak, Guatemala was estimated to be sending one child in every one hundred live births abroad as adoptees; most of those children were sent to the U.S. (

Selman 2012). The U.S. received the majority of the children, primarily infants and toddlers, as a number of countries like Canada and Spain eventually refused these adoptions due to evidence of and fears related to corruption/illicit practices (

Dubinsky 2010). These moratoria were an early warning of what was to come, not only in Guatemala, but globally, as the practice of ICA has declined over 90% since its peak in 2004 (

Neville and Rotabi 2020).

In the case of Guatemala, the ICA moratorium came after years of international pressure and just over ten years after the 1996 peace accords were realized (see

Figure 1) (

Dubinsky 2010). With fears about violations of child rights, the international human rights community first stepped in with U.N. Special Rapporteur Calcetas-Santos’ fact finding trip resulting in a report in 2000 (

United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights [ECOSOC] 2000). Among the findings were adoptions occurring in contexts of extreme poverty that often entrapped young women and their infants and very young children in a system driven by money (

Bunkers et al. 2009). The problems were characterized by desperation of Guatemalan families intersecting with the privilege of prospective adoptive parents in a post-conflict environment that had limited social welfare services and legal frameworks, policies and procedures in place to protect Guatemalan women and children (

Dubinsky 2010;

Rotabi et al. 2008;

Bunkers and Groza 2012).

In research that involved interviews with lawyers, social workers and adoptees,

Nolan (

2024) connected the genocide of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war with the contemporary forced disappearance and coercive adoptions of indigenous peoples. Nolan notably connected the neocolonial relations of power and inequality with the “orphanhood” phenomena thus leading to the creation of a complex infrastructure of adoption-related crimes that sustained illicit and illegal adoptions prior to the ICA moratorium.

substantive irregularities, some of which may indicate the commission of a crime: medical birth certificates issued prior to the birth; the photograph of the child does not match those found in different files … lack of DNA testing or negative DNA test. Failure by the birthmother to ratify her consent; false birthmothers; the mother is a minor; the mother does not speak Spanish [however, relinquishment documents were in Spanish]. Inconsistencies in the file and/or the mother’s statements. For example, the mother does not know where her child was born. Forged documents. The mother changes her mind about giving up her child for adoption.

The above observations about birthmothers are largely ignored. The report refers to a woman posing as a birthmother to carry out the paperwork process. This falsehood was thought to be a common occurrence during the peak years when illicit practices were particularly marked and active. This included circumventing the required DNA procedures that were eventually put in place to curb child sales and especially child abduction.

Nolan (

2024) illustrates these instances of fraud through case narratives. Alberto Zune was born to birth parents who lived in a small town near the Guatemala–Mexico border. A Belgian family adopted Zune as a baby through Hacer Puentes, an adoption agency under investigation. As an adult, he decided to travel and live in Guatemala to inquire about his birth origins. Zune does not know if and how he was stolen and from where; as he had chosen to believe that he was given voluntarily, he committed to the search for his birth parents. Mostly through his own investigations, he confirmed that his presumed birthmother (Zune’s mother on his birth certificate) was pressured by a “powerful neighbor” (Zune’s father on his birth certificate) who brought a lawyer for her to sign the birth certificate. His presumed birth father was rumored to be a child trafficker; in fact, his wife had been involved in the adoption business. Both finally admitted to Zune of being involved in the falsification of documents related to his relinquishment. By 2024, he had not found his authentic birth parents, but he learned through adoptee support groups in Guatemala that other Guatemalan adoptees had the same experience in their own searches (

Nolan 2024).

The

Hague Conference on International Private Law (

2007) also found irregularities and illicit practices, some of which were aligned with organized crime techniques (see

Loibl and Mackenzie (

2023)). They reported that vulnerable indigenous communities were disproportionately affected, highlighting the need for significant reforms to ensure ethical and transparent adoption procedures in the country. For instance, the

United Nations (

2000) reported on illicit practices, the grounds for this investigation as well as the above 2007 and 2010 reports. Human rights abuses and most particularly violations of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) include the disregard of the best interests of the child principle (

Roby and Maskew 2012). The following articles of the CRC are most related to intercountry adoption (

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner 1989) These rights include the right of a child to be cared for by their own parents whenever possible (Article 7); to not be separated from their parents against their will, except by a competent authority who deems it in the child’s best interests (Article 9); to be protected by their government against international trafficking (Article 11); to receive care that pays due regard to their cultural background (Article 20); to not be sold, kidnapped, or adopted in a way that violates the laws of their country (Article 21); and to not be adopted internationally when there is suitable care for them available within their own country (Article 21). Essential to complying with international standards contained in the 1993 Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect to Intercountry Adoption (henceforth simply referred to as the Hague Convention) is to observe these CRC articles (

Roby and Maskew 2012).

This article analyzes critically the end of an old adoption system prior to the moratorium of Guatemala’s ICA and a relatively new domestic adoption system; it also aims at providing a detailed look at child welfare systems and specifically the interface with the United States. To do that we apply a welfare systems framework for analysis while considering the law and policy context. Specifically, we look at the models of social welfare

Midgley (

2017) developed for different welfare systems in the global context. Methodically speaking, we include the stories adoptees to provide important illustrations. Drawing upon the work of others, our presentation is a synthesis and the result of a deep literature review rather than original case studies. This article is primarily a historical and policy analysis, which includes an examination of the pre-reform era (prior to the beginning of 2008) and the period of post-reform, that is, the 20 years since the legal framework was changed for child adoption. The authors undertake this analysis after their own engagement in advocacy for change and hands-on knowledge of the human rights reports and other documentation that have been produced over the past two decades.

2. The Policy Context and Midgley’s Framework

The history of ICA in Guatemala is framed within the Hague Convention. The fundamental principle of the Hague Convention is the best interests of the child (

Roby 2007;

Roby and Maskew 2012;

Yemm 2010) and it requires that signatory countries develop a central authority to carry out major adoption-related tasks and oversight as well as development of a legal framework, policy and procedures to prevent child sales and/or abduction into ICA (

Rotabi and Monico 2016). The major premise of the Hague Convention is that child adoption must first be oriented to domestic adoptions, and only when there are no options locally could an ICA be deemed to be appropriate (

Roby 2007;

Rotabi and Gibbons 2012). This continuum of care is called the principle of subsidiarity. The challenge to implement such a system, attendant to a continuum of care, requires the development of domestic adoption systems in Guatemala (

Rotabi and Gibbons 2012), and other forms of care for children unable to stay at home. Although reforming the adoption system does not lead to the full protection of child rights or a complete revamp of the social welfare system of any country, the principle of subsidiarity was a significant undertaking in terms of child welfare systems development (

Monico et al. 2022).

We will also consider a brief legal history. Specifically, after years of legal battle, eventually reaching the Guatemalan Supreme Court, Guatemala finally ratified the Hague Convention in 2007 and passed a new and congruent adoption law that same year (

Rotabi and Monico 2016). These were the first and earliest steps in the development of a new domestic adoption system, consistent with international norms and standards (

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner 1989). In November 2009, the U.S. Central Authority withdrew interest in participating in a pilot to reinitiate adoptions that the Consejo Nacional de Adopción (National Council of Adoption, CNA) proposed (

U.S. Department of State 2024). To close the “grandfathered children” adoption, in January 2017, the U.S. Department of State (

Rotabi and Bromfield 2017) reported that the CNA requested missing post-adoption reports of adopted children. The painful truth of some unknown number of the over 30,000 now adult Guatemalan adoptees is that their adoption was fraudulent (

Acevedo 2019). This policy context, anchored by the Hague Convention shaping the local/domestic law, is essential to understand the scenario in Guatemala.

While academics are most often concerned with the statutory aspects of social welfare, practitioners are more oriented to the specific social welfare interventions that are congruent with the legal framework (

Midgley 2017). Midgley’s framework for international social welfare policy and practice helps to bridge both perspectives because it offers a way of thinking about social welfare and systems of care in the policy context with practice implications. As discussed in the next section, using the social welfare models Midgley developed is critical to greater insights into the theory and practice of adoption systems in Guatemala.

3. Midgley’s Framework for Systems Analysis for Pre-Reform Guatemala

Midgley’s social welfare framework is instrumental in understanding the role of welfare institutions in designing, implementing and evaluating policy. For our purposes here, we will explore four models of social welfare as set forth by Midgley: (1) non-formal welfare institutions, whereby families and communities are at the driving seat of service provision (2) market-based welfare services, where the market privatizes services, is in charge of contracting, and is responsible for innovation, (3) non-profit and faith-based services, which emphasize the role of the voluntary sector in service delivery, and (4) government-based welfare services, which implies the direct state intervention in enacting social policy and running state-funded programs and projects (

Midgley 2017). Each of these models has its strengths and limitations, and a combination of models is more commonly found.

Table 1 below summarizes Midgley’s social welfare framework and is later applied to ICA in Guatemala.

Before we turn to the present and future of intercountry adoption in Guatemala, it is important to identify how the system was functioning, prior to reform, using a systems analysis approach.

3.1. Non-Formal Welfare Service Model

The key idea here is that welfare is provided through informal networks, such as families, neighbors, mutual aid groups, or cultural associations. In the case of care for children, the main idea is “kinship care.” This form of care is particularly relevant in areas far from Guatemala City and/or smaller municipalities and villages where traditional family life—especially among the indigenous peoples—is the norm. The authority of government simply is different in these collectivist communities, particularly indigenous communities, where government authority is largely avoided due to dynamics of oppression, discrimination, and racism dating back the earliest history of Guatemala (

Rotabi et al. 2008). Traditional leaders often play a key role in decision-making and continuation of social norms and many of the outcomes may be considered non-formal social welfare.

One example is when a teen mother, in Guatemala, gave birth with the assistance of a midwife at home. Her parents rejected the addition of another child to the already struggling and impoverished family. The midwife promised to take the child to a family that had the means and desire to care for the infant—a family living in the same community so that the birthmother would not feel like the child was too far away. The birthmother teen or her own parents agreed without any family court or other oversight. The process is non-formal and often the ‘adopting’ family asks the clerk of the local municipality to register the birth (provide a birth certificate) in the names of the adopting parents as if they are the biological mother and father.

An additional example is another pathway in which the child is informally placed with a family member like an aunt of the teen mother. Again, there is no family court oversight or adoption decree. And, like the above example, a birth certificate may be produced to make the aunt appear to be the biological mother. Or not—there are many children in Guatemala that are not registered at birth. Nonetheless, this is a non-formal adoption in which families circulate children as needed for their care. This is a classic example of kinship care. During the ICA boom, these non-formal care practices were exploited and distorted.

3.2. Market-Based Welfare Service Model

The key idea here is that welfare is best delivered through the market system, and the role of government is minimal—the state encourages private enterprise and does not directly intervene in a significant manner. In Guatemala, there was a powerful group of adoption attorneys (numbering in the hundreds) that carried out the practice under which a “notarial procedure” was utilized. In this process, and with only a cursory involvement of a family court, lawyers carried out adoptions as an entrepreneurial endeavor (

United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights [ECOSOC] 2000). They charged thousands of dollars for the adoptions, in a low-resource country, often called a ‘dollar a day’ economy at this juncture. In this environment, it was clear that some women were being paid for their relinquishment signatures as discussed above in

Bunkers et al. (

2009), possibly out of desperation. While prospective adoptive parents were not told of this practice—most were unaware of the corruption of paying birthmothers—the entrepreneurial model was a reality.

Private attorneys wielded a great deal of power—most often representing both the prospective adoptive parents and the birth/first mother (

United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights [ECOSOC] 2000). Further, it was stated

the only other professional who may safeguard the process is a social worker who officially verifies the circumstances of abandonment or makes a socio-economic assessment of the birth family for relinquishment purposes… Adoption through this route needs no resolution from a competent judge. The family court’s only action is that of soliciting the social worker, under oath, to execute the respective socioeconomic investigation of the family.

In practice, this meant that an impartial family court judge had no means to directly question the grounds for relinquishment—it was simply documented in a report submitted to the court.

Furthermore, people who called themselves “social workers” could carry out this sensitive work—there is/was no title protection in Guatemala and inevitably simply taking on the professional title occurred out of convenience. In other words, those who were unscrupulous could easily take the title of social worker to carry out their illicit activities. Essentially none of this work was conducted in the government social services setting—it was quite simply opportunistic, entrepreneurial and largely unregulated (

United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights [ECOSOC] 2000).

During the peak Guatemalan adoption years, there were also paid private foster families for many of the cases as the child waited for the adoption to be completed (

Bunkers 2005;

Gibbons et al. 2009). Private foster care was particularly attractive to those adopting, as children were well cared for and avoided being placed in an institution. However, others took exception, calling these homes “fattening houses” for the adoption system (

United Nations Economic and Social Council Commission on Human Rights [ECOSOC] 2000). Prospective parents/adoption agencies paid the foster families directly, and not through an official government system. Thereby, the lack of government oversight was part of the market-based welfare services.

3.3. Non-Profit and Faith-Based Welfare Service Model

The key idea here is that social welfare is delivered by non-profit, voluntary, or faith-based organizations. The role of government is often to regulate these organizations but not supplant with government services. In low-resource contexts, like Guatemala, these organizations often play a significant role in direct services and they are largely unregulated—many are not even registered with details of their work being collated by the government social welfare authority.

At its peak, well over one hundred U.S.-based adoption agencies were operating with Guatemalan adoption programs. These organizations in the U.S. were qualified as non-profit organizations (for U.S. Internal Revenue Service tax purposes). One non-profit agency, Holt International, is a good example of a long-standing faith-based agency involved in the earliest adoptions into the 2000s. It is an adoption agency with a considerable history of the practice globally, dating back to the mid-1950s when the practice of ICA first opened up in earnest in South Korea (

Bergquist et al. 2007).

Holt, a historical as well as current leader in adoption, not only continues to place internationally adopted children but today, on a smaller scale, helps to strengthen and support domestic or in-country adoptions in a handful of countries (

Holt International Children’s Services n.d.). Their support for domestic adoptions in low-resource countries today illustrates how they have shifted to be more inclusive of adoption practices moving beyond intercountry adoption, including important in-country services to support and strengthen families before domestic adoption (or ICA) are used as an alternative to biological and kinship family life. The commitment to domestic adoptions requires aiding in the development of adoption systems, such as pilot testing adoption services in a localized context, as is the case in Cambodia today (

Holt International Children’s Services n.d.).

That which is also notable about Holt International in its founding was a faith-based vision for adopting children, rescuing and “saving” children as envisioned by Evangelical Christian founders, Henry and Bertha Holt (

Bergquist et al. 2007). While the agency remains committed to faith (see their mission statement), today one does not need to subscribe to, or commit to, salvation and Christianity in order to adopt a child. Another faith-based agency that operated in Guatemala was All Blessings International. This Kentucky-based agency is one example of a small faith-based organization that processed many Guatemalan cases during the millennium adoption surge, processing those cases until the very end in the final days of December 2007 as well as into 2008 and beyond for unresolved cases that met criteria to be grandfathered in (personal communication, agency executive director Lucy Armistead (2012).

During the most problematic years when corruption undeniably emerged as a concern, Holt International closed adoptions from Guatemala much earlier than 2007. This was due, in part, to fears about child rights and corruption interfacing with their own international leadership (and reputation) in ICAs. Holt was a large agency that had other adoption programs internationally to shift their focus (like to African countries and elsewhere). However, many adoption agencies, too numerous to count, continued to function in Guatemala even after serious warnings of corruption, such as the early U.N. report that we have previously discussed (

Dubinsky 2010). History showed us that there were many faith-based residential care institutions (also called “orphanages”) that operated during this era with a non-profit status that should not be forgotten.

In sum, an unknown number of those residential care institutions were involved in the ICA system, identifying children within their homes and housing children. These children were not in the private foster care system, although some were identified at the institution and then sent to foster care. The lack of oversight and data collection produced limited evidence on this aspect of privately paid-for service of foster care or residential care of children in the pre-reform system (

Gibbons et al. 2009). With USAID operations and funding being compromised under the Trump Administration 2.0 for all overseas programs, including the ones described above, the prospects of children transitioning out from institutional care are winding down, unfortunately. This new policy change is beyond the scope of this article, but worth mentioning in the current political context.

3.4. Government-Based Welfare Service Model

The key idea here is that the state plays the primary role in providing welfare services, most often guided by legal frameworks. During the peak intercountry adoption years, there was a Guatemalan law for child adoption. However, as a legal framework it lacked the strength to withstand the insatiable drive for children; simply, it was not a law prepared for ICA, as it was written for domestic practices and was limited in scope (

Rotabi et al. 2008). Other than the attorney general’s office and cursory family court involvement, which had roles in the paperwork process, the Government of Guatemala was largely absent in the direct practices and services; they were certainly ineffective in safeguarding women and children’s rights within the scheme.

Furthermore, the interfacing government of the U.S. simply processed paperwork in the consular office of the embassy in Guatemala City. While U.S. consular officers had the right to investigate individual cases for irregularities and illicit practices, on the whole this was not done. The consular officers were simply overwhelmed with the sheer volume of children being processed during the peak years of ICA. Thus, there was little external government (such as the U.S. Embassy) involvement/oversight with the cases of intercountry adoption during the millennium adoption surge (

Rotabi and Bromfield 2017). And, when the U.S. Embassy appeared to be tightening down on the processes these steps, they were met with extraordinary pressure from politicians in the U.S. whose constituents were highly vocal, critical and demanding of expedient processes as they saw ‘their’ child being held up in unfair bureaucracy.

4. Midgley’s Framework Today, Domestic Adoption, and the Future of Guatemalan ICAs

We have presented a historical overview of the profound problems in Guatemala’s past as a source of children adopted internationally, specifically to the U.S. The moratorium implemented by the Government of Guatemala at the end of 2007 persists. Today, Guatemala has developed a central adoption authority as a child welfare office of the Government of Guatemala; this office oversees domestic adoptions as well as ICAs should the system ever reopen. The CNA fills this role according to the Hague Convention, as it employs both administrators and lawyers that help families with adoption processes, as well as psychologists and social workers who support the implementation of the Hague Convention standards by ensuring the best interest of the child. This progress is not to be underestimated, as there is a concerted effort to socially market adoption as a family-formation option and the obligation of a society that has a commitment to child rights. Additionally, the recruitment of foster families is an important element of this social marketing; there have been many foster-to-adoption cases in Guatemala as a result.

4.1. Non-Formal Welfare Service Model

Non-formal welfare inevitably still exists as families ‘take in’ orphaned and vulnerable children and they do not go through formal adoption systems (with an adoption decree) to care for the child in the long term. Kinship care is common amongst all Guatemalans and a millennial practice inherent in the Mayan cosmovision of caring for those within their ethnic group; it plays a key role in social organization and succession in Mayan communities throughout Mexico and Central America, as it is part of their identity, linked to property, and to personal and social networks (

Carrasco 2001). Considering that 42% of the Guatemalan population is of Mayan origin, these practices will prevail regardless of public regulations or market-based dynamics. This was confirmed when training on family negotiations for the care of orphaned and vulnerable children (family group conferencing) as

Rotabi et al. (

2012) found that family meetings about the well-being of children were taking place in the collectivist society of Guatemala.

As we explored above, in Guatemala, informal care is a customary method among families and within communities; for instance, children may live with relatives like aunts, uncles, or grandparents, especially when biological parents are not available to care for them. Although this is a common practice, formal adoption seems more challenging for Guatemalan families. Thus, informal care of children becomes more appealing to extended families and ethnic groups, and cultural traits provide the assurances necessary to believe that informal care will continue to be available to children in need regardless of regulation.

In sum, informal child welfare solutions in Guatemala are important to consider as informal solutions are most commonly exercised, especially in rural areas, where extended family networks and community care are critical in problem solving. Honoring these informal dynamics is necessary for real and meaningful intervention that honors family and kinship networks.

4.2. Market-Based Welfare Service Model

The entrepreneurial aspects, market-based services, of the previous Guatemala adoption system have ceased in terms of direct practice of child adoption. For instance, there is no longer a cadre of private adoption attorneys engaged in the ‘services’ of adoption, nor birthmother recruiters or foster families operating specifically for ICA (

Gibbons et al. 2009). Ceasing these entrepreneurial activities was essential to stop the sale and abduction of children into ICA, as per international standards. Under the 2007 adoption law, there simply is no place for paid services for adoption on the Guatemalan side of the equation today. All services fall under the government’s structure of the CNA as per the Hague Convention and Decree 77-2007. Fundamentally, government welfare services shape all aspects of child adoption today in Guatemala, but the collaboration or interface with the business and voluntary sectors continues.

For-profit activities include birthmother searchers as well as homeland tours, which are quite profitable activities for those who were adopted from Guatemala. Entrepreneurial (market-based) services continued to be unregulated and the fees for service are inevitably considerable, as is often the case of services shaped by a free market economy.

To address the wrongdoings of the past, a model that Guatemala can learn from is that of South Korea, where a Truth and Reconciliation process addressed past practices of illegal adoptions (

Associated Press n.d.). Also, Samoa had a process of restitution as well as reunion for children that desired to do so (

Fronek et al. 2021;

Roby and Maskew 2012). Another strategy for justice and reparation, and to address the unresolved grief that adult adoptees born in Guatemala face 20–30 years plus after having been adopted, is the use of international mechanisms, such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR).

The story of adoptee Osmin Tobar is illustrative, especially the use of international courts for documentation and redress. He was adopted by a U.S. family at age 9 after being removed by government agents on allegations of child abandonment (

Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) 2015). He relocated as an adult to Guatemala to look into his birth origins; he discovered that his “abandonment process was based on anonymous testimonies from neighbors, without proper verification” (

Nolan 2024). He and his birth family brought a legal case with the IACHR in Costa Rica (

Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) 2015), and in 2024, for the first time, the Guatemalan government acknowledged and apologized to him and other victims of illegal adoptions for the wrongdoings of the past (

Abbott 2024).

In sum, recognizing these past abuses is critical, and market-based services were a core problem in the pre-reform system. Today, for-profit services are prohibited, and this is essential to realize the goal of preventing future child sales and abduction into adoption.

4.3. Non-Profit and Faith-Based Welfare Service Model

The non-profit organizational element of adoption agencies, such as those in the U.S., inevitably stand ready to resume adoptions. In fact, the CNA engaged with nongovernmental organizations to carry out a campaign promoting domestic adoption of special-needs children (

Monico et al. 2022). However, under the Guatemala government’s legal framework, there is no statutory role for a non-profit/non-governmental organization entity to engage in international or national adoption procedures in Guatemala. Governments engaging in close monitoring and ongoing supervision is critical to prevent non-profit organizations from engaging in the deception of birth families, fraudulent procedures, legal malpractice, and unprofessional behavior occurring during the commercialization of children prior to the moratorium.

Some of these institutions funded by church donations, including U.S.-based congregations, have continued supporting the deinstitutionalization of children. For instance, Advisory Group members for the Faith to Action Initiative, originally funded by USAID in 2013 “…began to find permanent family care options for children from birth to aged three who were living in residential care… [and] able to safely transition 168 children from the government orphanage into families” (

Faith to Action Initiative 2025, par. 2). Another Advisory Group member was involved in “developing a training curriculum focusing on social work values and family-based alternatives for the Guatemala School of Justice” (

Faith to Action Initiative 2025, para. 3). This type of good practice has been essential to reducing the residential care institutionalized population.

In sum, a non-profit approach is essential for ethical child adoption practices. Faith-based services are often aligned to the non-profit spirit. Partnerships like those described are promising in building capacity in child welfare services today.

4.4. Government-Based Welfare Model

Since the new law was adopted in 2007, Guatemala has experienced much progress. From 2008 to 2024 there were 1635 domestic adoptions processed; most of the children were 1–3 years old. However, four hundred 7–17-year-old children were also adopted; 203 children were part of sibling groups; and 48 children had a disability (

Bunkers and Santos de Ucles 2024). In the last quarter of 2021, “3694 children and adolescents were placed in 150 public and private residential care facilities” (

Monico et al. 2022, p. 12), of which 84% were placed in private residential care facilities. Efforts towards deinstitutionalization mentioned earlier have contributed to reducing the populations in residential care facilities from 5800 in 2013 to 4000 in 2021 (

Better Care Network 2021;

Faith to Action Initiative 2025).

From a practical perspective, the question is how did social service/adoption procedures change (reform) to meet the ends of an effective, ethical, and culturally appropriate government-based system? The

Table 2 below presents key elements which are applied to domestic adoptions and would be applied to ICA, should the system reopen.

The above table is provided to not only indicate the specific system changes, but also to point out the distortions of the various aspects of practices during the millennium adoption surge. An essential component to the reformed system is the government’s institutional will to prosecute those who were involved in the past child abduction for commercialization purposes. The Law Against Sexual Violence, Exploitation, and Trafficking in Persons (VET), adopted in 2009, imposing penalties of 8–18 years of jail and associated fines on traffickers, is part of the new child protection system (

U.S. Department of State 2024). However, only a few cases of illegal/illicit adoption are considered by the courts and considered for years without any justice.

For example, in the case of Loyda, at least 10 people charged for their involvement in her child’s theft have been prosecuted under the anti-trafficking law in Guatemala (

Barrias and Romo 2012), but the search for justice has lasted two decades and Loyda’s hope for reunification with her daughter is remote.

A 2021 report of the Department of Temporary Family Care (Substitute Families) of the Secretaría de Bienestar Social (Social Service Secretary) reported that in Guatemala there are “residential care facilities with over 4000 children and adolescents in more than 120 residential care facilities;” in contrast, there were only 122 accredited foster families reported in 2021 (

Better Care Network 2021, p. 1). This is in spite of the fact that “79% of Guatemalan families would consider temporarily providing care for a child in need… [and] 41% of families… reported that they cared for a child that was not their own” (

Better Care Network 2021, pp. 2–3). These statistics provide an “insight into the socio-cultural threads and traditional values that hold communities together” (

Better Care Network 2021, p. 2) and suggest that formal care has a real potential among families and within communities in Guatemala.

However, family court judges tend to rule favorably for extended family care (familia ampliada) in many cases of abandonment, as opposed to kinship care (familia equiparada), a concept that was legally adopted only in 2010. Even if there may not be any familial bonds with the child, these judges would rule in favor of those who have extensively exercised a parental role, and with whom the child may have established affective ties. Although there may be obvious advantages in formalizing these various forms of formal care, a well-structured legal system for kinship care is still lacking in Guatemala; besides, foster families are still not legally allowed to adopt under current regulations (

Better Care Network 2021).

While it is beyond the scope of this paper, social work as a discipline and related practices were distorted in this era. Today, with greater training and transparency, things have improved in the reformed system with greater role clarity with the ethical paradigm of social work as a profession. Among other things, the CNA has made a commitment to self-determination in child relinquishment, among other ethical principles and ideas of the social work profession (

National Association of Social Workers 2021). For these women/birthmothers, they are now considered to be “in conflict” with their pregnancy and they are offered un-biased counseling today in a supportive manner rather than one that exploits their vulnerability (

Monico et al. 2022).

The searches for birth parents mentioned above are a promising direction for addressing the unresolved grief that illegal/illicit adoption left among adoptees from Guatemala and their quest for resolution. Some of these searches may involve those that served as recruiters of birthmothers during the period of adoption commercialization prior to the moratorium. The construction of transnational families through the adoption triad has the potential to bring about resolution to this painful adoption history of illegal adoptions in Guatemala, and all actors have a role to play—government, non-state actors, birth and adoptive parents, and the international community.

The question of the future of ICA is somewhat difficult to answer. Fundamentally, the country underwent a great shock during the millennium adoption surge. It was a human rights catastrophe (

Rotabi and Bromfield 2017). Reopening in the aftermath of such a period is profoundly complicated (

Monico et al. 2022). At this time, there appears to be no real movement in reopening Guatemala as an ICA location. And, all processes will take place within the government CNA/central authority policies and procedures, as summarized above, that were developed to be transparent and based on sound social service and child welfare practices and ethical procedures, by design (

Monico et al. 2022).

In sum, today child adoptions are governed within a central authority framework that prohibits the practices that led to the human rights catastrophe that we have presented. The development of this government framework for services is ultimately the best outcome of reforms, operationalizing sound policy and child welfare practices as presented above.

5. Conclusions

We have reviewed the history of ICA in Guatemala considering the past, briefly touching on the war years (1960–1996) and then focusing on the millennium adoption surge. This was an era that the New Internationalist (2000) called a “baby snatchers boom” and

The Economist (

2010) questioned “saviors or kidnappers?” while

Lacey (

2006) pointed out, in the New York Times, that there was a great deal of scrutiny.

Larsen (

2007), a journalist and adoptive mother, asked in Mother Jones: “Did I steal my child?”. These are just a few of the provocative articles published by the popular press during this era.

Midgley’s social welfare framework in a global context is utilized to analyze the problems of illicit practices and changes in the reform era are presented. Specific attention has been paid to non-formal systems, market-based or profit-oriented systems, non-profit and faith-based systems, and government-based systems shaping adoptions systems responsible for the permanency of Guatemalan children. Illustrated were the problems, illicit practices, and human rights abuses of the past and the changes that have been made to meet the international criteria and standards of the Hague Convention. While hoping for the continued growth of domestic adoptions in Guatemala, ICAs will not reopen as long as “receiving” countries continue to assess Guatemala as not meeting the Hague Convention standards. It is critical to note that the Hague Convention is not viewed to be a panacea by international law experts (

Loibl 2019); however, critique is beyond the scope of this paper.

Yet, children in residential care facilities, including those with “special needs” (older children, sibling groups, and those with disabilities) continue to be in great need of care and attention in Guatemala and the continued development of domestic child care systems—including domestic adoption—is essential.