Abstract

Although rules support people while executing tasks, they are not the same as work-as-done. It can be impossible to follow the rules and finish the job at the same time. In this study, the objective is to better understand the stakes and interests that lie behind retaining gaps between work-as-prescribed and work-as-done, mapping the benefits and fears of noncompliance. The study was conducted along the vertical hierarchy of an operational flight squadron of the Royal Netherlands Air Force. We applied a qualitative survey research methodology using semi-structured interviews, complemented by an investigation of relevant documents. We found a public and political commitment to compliance made by the Dutch Department of Defence, which reinforces a cycle of issuing promises followed by pressure to keep the promise. This contradicts the found need for adaptation and freedom to use expertise. The official safety narrative seems to convey a hidden message—bad things happen to bad people, reminiscent of a bogeyman. One opportunity to resolve the situation is a doctrine change, changing prescriptive rules to guidelines.

1. Introduction

Rules and procedures help people to remember steps in a task under varying circumstances, ensure that people can work together effectively, function as organisational memory to indicate how processes work and as a means of identifying deviations that might be problematic [1]. Some rules and procedures are based on previous experiences that operators have not encountered themselves. However, rules and procedures are not the same as work-as-done [2]. Work takes place in a context of limited resources and multiple goals and pressures as well as surprises, constraints and novelty. In many cases, it can be impossible to follow the rules and finish the job at the same time [3,4]. Work as actually done is often more complex than that which can ever be captured in rules and procedures [5,6]. Referring to these as “workarounds” [7] or “violations” [8] is judgemental and misguided. Realising that there is a push–pull between centralising (through procedural compliance and top-down control) and decentralising is not new (cf. [9]). Leaning toward decentralisation, for instance, 19th century Prussian military commanders were urged to not order more supplies than absolutely necessary, and not plan beyond the situations they could foresee, thus empowering their subordinates to deviate and adapt, as long as it helped meet the organisation’s or mission’s intent [10].

In modern military organisations, particularly those held to the rule of law, media scrutiny and democratic parliamentary accountability, the push–pull can be intense between upholding an image of strict, law-abiding compliance while retaining flexible, adaptive capacity. The conflict is typically pushed down into local operating units on the various operational frontlines, with stakeholders up and down the hierarchy silently hoping nothing will happen to blow the conflict into full view (and if it does, blaming individual operator error or violations is still a convenient way out [11,12]). In recent work, we described the necessary adaptations to work-as-prescribed—the description and formalisation of work in rules and procedures [13]—as “local ingenuity”. These can congeal into routines that are part of the regular (though “hidden curriculum”) repertoire of operators. They remain relatively invisible to management, were not originally intended and are not included in any existing rule base [14] even though they are part of the informal work system (including informal instruction to novices) (see [15,16]). Local ingenuity is an expression of care, commitment, expertise and experience, as well as professionalism and judgement. All are necessary to accomplish a task when rules and procedures are insufficient or actively hostile to achieving goals and completing the mission [17,18,19].

Picking up where our recent work on local ingenuity [14] left off, in this present paper we dig more deeply into the interests that lie behind retaining the status quo. There is a gap between work-as-prescribed and work-as-done—the way work is actually done [13]. In our approach, the objective is to better understand (if not eventually offer stakeholders the means with which to breach) the stalemate by mapping the benefits and fears of noncompliance and the stakes and interests that lie behind both such noncompliance and its denial.

1.1. Conflicting Paradigms

Two paradigms regarding rules and compliance can be distinguished. In the top-down classical, rational approach to rules, rules and procedures are seen as desirable, necessary and unavoidable ways to direct and control human behaviour. Violating these rules and procedures is seen as negative behaviour that needs to be understood in order to be suppressed, as every violation means a first step towards causing an accident [1]. An alternative approach is constructivist, viewing rules as dynamic, local, situated constructions of operators as experts [1]. In this paradigm, the reason for violating procedures is found in that multiple, conflicting and implicit goals must be reached [20]. A difference between the way work is assumed or imagined to be done and the way it is actually done is unavoidable [21]. Translation and adaptation are inevitable, and violations are necessary when rules and reality do not match [1]. Furthermore, rules and procedures can lead to diminishing expertise and even to the situation where people stop thinking all together [22]. Under the duress of conflicting goals, employees can do their work because they can innovate and improvise outside the rules and procedures [21]. We conducted this study from the constructivist paradigm regarding rules and compliance, because research shows that the classical paradigm does not solve the gaps between work as done and prescribed. Rules and procedures can never fully describe all possible situations employees will encounter nor fully describe exactly how the work should be done [23]. Expecting people to adhere to rules that do not match practice does not add to safety; adaptation, even if this means non-adherence, can add to safety [24]. The classical paradigm therefore seems to result in a stalemate. Since less is known about the constructivist paradigm, it seems worthwhile to study whether or not it resolves the gaps between work as done and prescribed.

1.2. Population of Interest

The study was conducted along the vertical hierarchy, starting in a flight squadron and ending with the commander of the Dutch air force, the RNLAF. Within a hierarchal organisation such as the RNLAF, what is deemed acceptable and unacceptable (what is needed and allowed) is conveyed through the chain of command. On studying the enduring difference between the way work is done and prescribed, it makes sense to expand the original study [14] to include the entire chain of command.

The flight squadron was originally sought out to study how two conflicting paradigms regarding rule perception and management affect goal realisation in an operational setting through the identification of local ingenuity [14]. To understand why the difference between the way work is done and prescribed or is intended to remain as a status quo despite the undesirability, we focused on the same squadron. This required us to include the vertical hierarchy of the RNLAF in our scope, up to and including the commander. We also included the Military Aviation Authority (MAA) in our study, as many rules that govern this squadron’s operational activities derive from there. The expansion resulted in three focus groups: operators, senior management (the chain of command) and rule maker/enforcers (the MAA).

The flight squadron is an operational unit containing 55 male employees, aged between 22 and 45, and some 30 aircraft. The squadron activities include flight planning, briefing, debriefing, line maintenance, and ancillary support activities. The squadron’s home base is one of the Dutch airfields, but it is also active in other North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries for joint exercises, and on deployment missions elsewhere. The goals of the squadron under study are to maximise the individual’s potential by developing their skills and building expertise, executing the missions assigned to the squadron by the air force commander and their delegates within the appropriate budget, and performing this safely. An overall RNLAF goal is being compliant with existing regulations, rules, and procedures.

From strict to less strict, the RNLAF has to deal with laws, such as the Aviation Act, and with civil regulations from the International Civil Aviation Organisation, the Joint Aviation Authorities and the European Aviation Safety Agency. Furthermore, the RNLAF is impacted by rules from the European Defence Agency and NATO standardisation agreements (STANAG) and rules from the MAA such as the military aviation regulations, acceptable means of compliance and guidance materials. Finally, there are RNLAF rules regarding the operation of the aircraft, flight operations as well as the exceptions or temporary rules, standard operating procedures, guidelines and checklists.

The RNLAF is part of the Dutch Department of Defence (DoD). The DoD is a political instrument that has suffered from a decade of budget cuts, while political ambition and the expected output have remained the same. This has created tension within the DoD: budget cuts led to downsizing—which subsequently led to reduced inflow and many vacancies—and an increasing pressure to deliver the expected output with a reduced work force.

Since 2018, all DoD incidents and accidents that are classified as “big” in terms of consequences (damage to people, environment and/or equipment) are investigated by the Defence Safety Inspectorate. These investigation reports, as well as the formal response of the DoD to the House of Representatives, are made public. The recommendations made by the Inspectorate are translated by Central Staff (Central Staff is the upper layer of the Dutch Department of Defence, responsible for policy. It directs the ministry’s activities, allocates the defence budget and monitors defence spending.) of the DoD into rules, policy and safety measures for the armed forces investigated. Since its establishment, the Inspectorate has conducted five investigations regarding RNLAF incidents and accidents.

The RNLAF has the ambition to improve its competitive advantage under the umbrella term “fifth-generation air force” (5GAF). This means the RNLAF embraces terms such as ownership, continuous learning and reflection, adaptability, resilience, agility and flexibility. In a time when the opponent has access to the same technology and equipment, the RNLAF considers the air force employee key in making the difference [25].

2. Methodology

We applied a qualitative survey research methodology complemented by an investigation of relevant documents. We conducted qualitative thematic analysis and triangulation based on the gathered interview and document data, focussed on exnovation [26] to ensure an accurate description of the way operators perform day-to-day work. Because only the first author (LB), an inside researcher, conducted the interviews, specific attention was given to the concept of “researcher-as-instrument” [27]. As the co-authors were external researchers and would also be involved in data analysis, it made sense to first consider the impact of the concept on categorisation, analysis and interpretation of the data [28]. Beforehand, the authors agreed on the interview questions and decided that the interviews would be transcribed to exclude subjective representation. Previous studies show that a researcher must be both reflective and reflexive to build trust with the interviewees and ensure they provide detailed information [29]. A trusting relationship was ensured as LB was familiar with the population of interest and knew all the interviewees. LB has worked for the RNLAF for over 23 years, including 17 years as an aviation psychologist. RNLAF operators are used to openly discussing all sorts of topics, including non-adherence to rules, with aviation psychologists.

2.1. Interviews

To collect data, we held semi-structured interviews with twelve people, ranging from pilots of the squadron to the RNLAF commander. All interviewees have a prominent role in the fulfilment of airpower, although the upper ranks have not been active operators for at least 10–15 years. All interviewees are male. The age range is 30–44 years for the operational unit and 45–59 years among the remaining eight interviewees.

Four of the 12 interviewees were identified by their involvement in the previous investigation. These four represent the ranks that can be obtained in the operational unit. We identified the consecutive commanding officers up to the RNLAF commander as eight additional interviewees for the four primary interviewees. All interviewees were specifically chosen because of their knowledge of enduring differences between the way work is done and prescribed and/or ability to influence these differences. The interviewees are divided into three groups, rule users (interviewees 1 to 4), leaders (interviewees 5 to 9) and rule makers/enforcers (interviewees 10 to 12). To ensure anonymity, all participants are referred to by code (i.e., interviewee 1, etc.).

We approached the interviewees by email, explaining the study objective and the relevance to the organisation. Participation was voluntary and the participants signed an informed consent form attesting to their understanding and approval of the study. The semi-structured interviews lasted approximately one hour and were recorded and transcribed to provide accurate records for analysis. Recordings were deleted and only the anonymised transcriptions were stored.

The interview guide included four main questions as discussion topics:

- Do the interviewees recognise a difference between the way work is done and the way work is prescribed in their own work experience?

- Is a difference between work-as-done and work-as-prescribed considered undesirable?

- Why is the difference between the way work is done and prescribed not solved?

- Can the current set of rules and procedures match the dynamic complexity of flight operations?

Examples of follow-up questions are:

- Can you give an example of a difference between the way work is done and prescribed?

- Is a 100% compliance attainable considering the goals that need to be attained?

- Are operators allowed to adapt rules to a situation they encounter?

- Why are operators reluctant to use their discretionary space?

- How can rules and procedures be aligned with the dynamic complexity of flight operations?

During the interview, we presented three examples of goal conflicts between compliance and executing the flight mission and asked interviewees for their opinion and advice. Taken from our past research, the three examples are:

- When fire fighter capacity is low, airport regulations state that large passenger-carrying helicopters are not allowed to take off or land at the airbase. In this case, the helicopters land and pick up passengers at a suitable spot outside the airbase, where airport regulations do not apply.

- Due to budget cuts one airbase is active only three days a week. The area is often used for training purposes. If a pilot needs a precautionary landing on one of this airbase’s inactive days, airport regulations state that the helicopter will not be able to take off after repairs are finished. A precautionary landing outside this airbase does not meet these restrictions, hence taking off is allowed.

- Out on a training exercise a helicopter needed repairs. Since it was not stationed at home base, the equipment needed to comply with the regulations for “working at heights” was not, and could not be made, available. The crew chose not to comply and did the repairs without being secured. This resulted in an operational helicopter and a successful training exercise.

2.2. Document Study

We studied five incident/accident investigation reports and the formal responses of the Department of Defence to the House of Representatives. These investigation reports are:

- Self-shooting: on 21 January 2019, an F-16, the follow-on aircraft in a formation of two, conducted a shooting session over the Vliehors. During the flight, the F-16 fired its on-board gun at a practice target [30].

- Dangerous goods: on 24 February 2016, officers from the Military Hazardous Substances Control Corps found an oxygen cylinder violation regarding its testing, labelling and release for road transport. The investigation committee made six recommendations. During a debate in the House of Representatives, a request was made to the government to commission an independent investigation into the implementation of the recommendations [31].

- Risks identified: from 17 to 19 June 2019, 14 students were on professional practice training at Woensdrecht Air Base and the nearby Ossendrecht military training ground. At 08.29 a.m. Wednesday morning, while preparing the assignment for the day, the group was unexpectedly caught in a thunderstorm. Some students were struck by lightning and one of them was seriously injured [32].

- Weak signals: the Defence Safety Inspectorate announced a study at the end of 2019 to gain insight into the handling of minor incidents at Defence and thereby strengthen the learning capability of the organisation. The research focuses on the function of signalling of minor incidents and the influencing factors [33].

- NH-90 helicopter crash: on Sunday 19 July 2020, an NH-90 maritime helicopter with a four-man crew practised both approaches and deck landings on the patrol ship Zr. Ms Groningen. During the execution of a deck landing circuit, the helicopter hit the water. The two crew members in the cockpit did not survive the accident [34].

These investigation reports are publicly available. The document study was enriched by the long experience of the first author (LB), who has spent years as an aviation psychologist working with and observing the population of interest.

2.3. Data Analysis

LB conducted and transcribed the interviews, RB and VS read the transcriptions. LB used NVivo software to code and analyse the transcripts. The first level of analysis consisted of coding relevant sections line by line [35], resulting in categories of data called nodes. Using inductive open coding, nodes were created bottom-up, emerging from the data rather than by applying a theoretical framework from the literature, although some nodes could refer to concepts found in the literature. Theoretical saturation was reached as the final three interviews generated no new information regarding our research questions [36]. The transcripts were coded using the previously created nodes. No new nodes were needed.

A total of 93 nodes were created. LB revised these twice to minimise overlap, to confirm a label accurately represented the findings and to make sure they contained a meaningful amount of data. This work led to the removal of 27 nodes. A third revision combined the various nodes pertaining to the three example cases. Then, overly sensitive findings were excluded due to security reasons, resulting in the removal of another 13 nodes. This left 53 nodes for use in the analysis, which LB discussed with RB and VS.

On the second level of analysis, the co-authors (LB, RB and VS) identified relationships formed between the nodes, creating underlying themes that each contained several nodes. This analysis produced a total of 14 themes that seemed most pressing and/or promising regarding the difference between the way work is done and prescribed. The 14 themes were subsequently categorised in three overall themes used to describe the research.

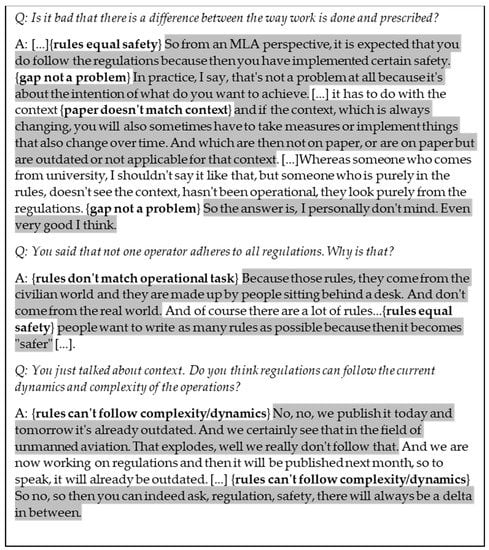

As an example of the coding process, Figure 1 presents an excerpt of the transcription of interview 11. Nodes are set in {brackets} with the highlighted sentences that led to the node following the label. Three nodes {paper doesn’t match context}, {rules don’t match operational task} and {rules can’t follow complexity/dynamics} resulted in the sub-theme of “rules cannot keep up with the complex, dynamic nature” that subsequently became part of the overall theme “need for adaptation in work”.

Figure 1.

A sample of a coded interview from interviewee 11 depicting the coded sentences (highlights) and accompanying nodes (in {brackets}).

Closely examining the data-based findings in two rounds of discussion, the co-authors debated the findings until consensus and compared the analysis with the literature.

3. Findings and Interpretations

The findings are divided into three sections. Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 describe findings related to the importance of compliance and the need for adaptation in work. Section 3.3, enduring tension, describes the findings related to the tension resulting from the contradiction between the importance of compliance and the need for adaptation.

3.1. Importance of Compliance

The current study finds that adherence to rules and procedures is considered important in the population of interest. Rules are seen as the most important means to achieve safety and compliance. Each interviewee stated that compliance is motivated by the conviction that rules are important to safety:

I think rules are very important. They exist for a reason. We say rules are written in blood.(Interviewee 4)

Senior management and rule makers/enforcers regard noncompliance (the difference between how work is done and prescribed) as undesirable because rules and compliance function as a safeguard:

A difference between an official regulation that says you’re not allowed to fly when drunk on alcohol, for instance, and the way work is done is unacceptable.(Interviewee 1)

These findings match the theory espoused by Rasmussen [37], who states that the work space is defined by rules forthcoming from different domains, creating both safe and unsafe zones. Safety rules serve to define boundaries to prevent accidents [38]. Rules and procedures enhance safety in some instances [4].

According to the interviewees, compliance in the RNLAF is also motivated by a fear of the consequences of noncompliance, meaning fear of personal liability and accountability.

We have these rule books with important rules, and if I break them, I will personally be held accountable, legally accountable.(Interviewee 2)

The interviewees report that this fear of the consequences can lead to situations where safety concerns are diminished in favour of compliance.

So, I’m allowed to put the helicopter down on the other side of the airport fence, which is potentially far more dangerous because it’s an uncontrolled area. […] But inside the airport fence, which is controlled terrain, we have rules that don’t let [us put the helicopter down without sufficient firefighters].(Interviewee 3)

If you return to base early because of a technical problem, you’re not allowed to land. I’d have to deviate to an alternate [landing spot] until the fire department has finished monitoring the refuelling of other helicopters. […] But the airfield is right there!(Interviewee 2)

In other words, compliance with rules and procedures is a way to manage the liability and accountability of an organisation [39].

Senior management reports compliance is an important goal in itself, particularly with regard to laws (rather than rules made by the organisation):

When it comes to compliance, it’s about hard law, the bottom line. It doesn’t mean you can’t deviate, but [the deviation] has to be written down.(Interviewee 7)

Additional data confirming that adherence to rules and procedures is considered important in the population of interest come from the five incident investigation reports. These reports focus on how work should have been performed and how work-as-done deviated from how work is prescribed in rules and procedures. Differences between the way work is done and prescribed are in all five of these reports causally related to the occurrence. For instance:

When he was talking to air traffic control he declared an emergency but didn’t make a PAN or mayday call and he didn’t select the SSR 7700 code as prescribed by regulation.(document case study 1)

Amidst perceived continuing pressure to validate her existence, the RNLAF is adapts her processes to the circumstances so that she can do with less.(document case study 5)

People external to the organisation also see rules as the most important means to achieve safety and compliance. After an incident, the RNLAF promises the regulator, politics and public to implement new rules, procedures and instructions aimed at preventing a similar occurrence. With each new incident, the media questions this commitment and the resulting public debate puts pressure on the DoD to reconfirm and adhere to its own statements.

Why are things difficult? Because we live in the Netherlands, with crowded air space and politicians who will not accept that every now and then we’ll drop an aircraft on a school playground.(Interviewee 12)

This pressure can become so great that noncompliance is expected to have personal consequences such as the resignation for the minister of defence and chief of defence [40,41]. Compliance, in other words, is a tool needed to control untrustworthy humans who inevitably make mistakes [39].

From a leader’s perspective, high levels of compliance (and therefore a small number of exceptions) are more manageable. Compliance with formal rules results in standardisation, transparency, predictability and control [42,43]:

The certificate means that the organisation is compliant with rules and so has assured safety to a certain extent.(Interviewee 11)

The only side note rule makers/enforcers make on the ease of the compliance paradigm is the fact that knowledge of the rules is a prerequisite. However, rule makers/enforcers believe that knowledge of the existing rule base needs improvement.

No, we just put a person in [a] position because his career needs a post as commanding officer. Yes, of course, he’s incredibly good at counting stuff, but he doesn’t know [much] about military aviation regulations.(Interviewee 11)

On the other hand, chances are that general knowledge of the rules has declined because so many rules are (too) detailed [44], or the notion that experience spreads the detailed knowledge of rules abundantly [45].

3.2. Need for Adaptation in Work

According to the interviewees, the number of rules is ever increasing, especially after an incident or accident. This matches the literature as advocated by Antonsen et al. [46]: new rules created after an occurrence provide an opportunity for an organisation to show they take safety seriously and try to prevent similar occurrences. The result is an increasing bureaucratisation of safety [39,42].

My brain is like an iceberg that holds lots of penguins. And with each new rule a new penguin appears. At some point the iceberg is full, no room for more penguin-rules. And as I get older, the iceberg starts to melt. In other words, with new rules, penguins fall off the iceberg. I’m just hoping it will be a penguin-rule about an area I need to avoid, because my map will show that too [to remind me], and not a the penguin-rule about the emergency procedure in case of an engine fire.(Interviewee 2)

I don’t think we should have a rule for everything. We just need a general set of rules that we can use to make the right decisions in situations we haven’t [dealt with] before. But, take a look at our operations manual. […] As a pilot you can’t know [all] these rules by heart. It’s just too many, with 50 exceptions for every rule in the book.(Interviewee 5)

Reducing the number of rules is seen as a necessity. However, some interviewees are very sceptical about the feasibility as they expect politicians and society will not accept the deletion of rules.

Besides signalling the plethora of rules, the current study has identified that the population of interest often finds it necessary to adapt rules in the execution of a task.

The world is changing much faster than rules of any kind can follow. We cannot even think that fast.(Interviewee 6)

Every day we feel the tension between trying to fully comply with the rules and doing our job.(Interviewee 5)

These are examples that no one thought of when writing the rules.(Interviewee 8)

These results match the research by Damoiseaux-Volman et al. [5], which shows that the difference between rules and the complex nature of work can be substantial. When comparing the way work is done to the way it is prescribed in guidelines for two tasks in a medical setting, they found ten and 16 new functions or changes, respectively, indicating that work-as-done is far more complex than the rules convey.

Most interviewees were adamant: rules cannot keep up with the complex, dynamic nature of military operations in training situations or mission deployment. When it comes to less strict rules, most interviewees state that rules can never fully describe every situation encountered and that it is up to the operators to finish the job. Additionally, in some cases, it is permissible to deviate:

We have standard operating procedures, but if before a flight you decide to do things differently, that’s fine, as long as you let your colleagues know.(Interviewee 7)

These results fit the work of Carim et al. [47], who found that dealing with ill-suited procedures led pilots to use fragments of different checklists to cope with an emergency situation, therefore adapting the rules that could not follow the far more complicated situations they encountered.

The interviewees state that one reason rules cannot follow the complexity of daily work is that they are sometimes outdated and no longer match the context. Operators introduce a mismatch because they were not involved in writing the rules. Senior management as well as rule makers/enforcers agree that rules are written by people who do not perform the tasks themselves.

Policy makers at Central Staff who produce new rules and agreements with politicians stand too far away from the work actually done. They get so wrapped up in their own policy world and political climate that they have no idea what is needed at the operator level.(Interviewee 10)

These results agree with the work by Carvalho et al. [48], who found that rules written by officers who do not do the work themselves led to rules unsuitable for dealing with emergency response situations in firefighter organisations.

Every interviewee said that rules actively hamper task execution. According to operators, in some cases it would be simply easier and more convenient to not follow the rules.

I have a perfectly functioning aircraft out in the field after a precautionary landing which turned out to be a false alarm. Now I can’t get the aircraft off the ground because there’s a rule on it somewhere, that [even if] it’s safe to go […] And that hampers task execution, because now the aircraft stays in the field unsheltered from weather, and maintenance and security [crew] need to [get to it] there. It just hampers us.(Interviewee 3)

Some interviewees found not being able to finish the job frustrating.

If we have to attend a forest fire [somewhere], I hope the rules will let us. That we won’t have to ask [if] we are allowed to do this outside airbase opening hours […] or will we just put out the fire?(Interviewee 3)

As another example, in January 2022 the Minister of Defence stated in an interview that rules and procedures hamper defence against cyber-attacks and that laws and rules need to be changed [49].

The literature confirms this perception. For instance, Tucker [50] describes how disruption and errors in information hamper employees in doing their job. These “operational failures” [50] result in necessary workarounds [18,19].

The need for adaptation in work is evident in that operational pressure takes precedence over compliance. Most interviewees report on air power receiving first priority, which makes sense to them, since this is this is the actual output of the RNLAF.

Mission first. We must have air power, that’s the first priority […]. We’re in a military world, which we sometimes forget.(Interviewee 11)

Most interviewees refer to the drive to finish the job as a can-do mentality. They see it as a positive aspect of the RNLAF identity, even though it can on occasion have a negative aspect.

The drive that people have to get it done, it’s part of our DNA and undeniably has a lot of good in it […] but sometime a little dark edge to it.(Interviewee 9)

As this quote demonstrates, the focus on operational output can result in a dark side to can-do behaviour. Especially rule makers/enforcers warn against this negative effect as they think can-do behaviour comes from employees looking for the loopholes.

We [they] are more ‘can-do’ than we dare realise. Of course, we [they] do ‘plan-do-check-act’, but we [they] also do ‘can-do-react’. It takes us[them] a long way, but it can also make us [them] fall flat on our face. […] We [they] don’t solve the problem, we [they] just try to figure out how we [they] can proceed as planned.(Interviewee 12)

It’s even about simple things, like driving regulations. Every truck driver is obliged to take a 30-min break every three hours of driving. But when we [they] are on exercise in another country and need to move equipment, we [they] pay our drivers an exercise fee [..] so the rules don’t apply to military drivers.(Interviewee 10)

Rule makers/enforcers report that it is not always right to give first priority to air power, even though this is the desired output.

Not everything legal is smart to do. Not everything allowed is the sensible thing to do. I can get my neighbour pregnant, no law that prohibits that, but it’s not smart. It’ll give [me] so much trouble.(Interviewee 12)

On the other hand, Morrison [39] and Dahling et al. [40] have documented the positive side of noncompliance in favour of organisational goals, using the term “pro-social rule breaking” to describe noncompliant behaviour benefitting the organisation, for instance, when employees need to choose between compliance or adaptability in the interest of task execution [51]. Letting operational tasks take precedence benefits the organisation, and so this is considered constructive [52].

Finally, in the view of every single interviewee, changing rules that the RNLAF has no authority over is nearly impossible.

That’s part of the rule base we, like every other ministry, have to comply with. […] There is no way to sugar-coat that.(Interviewee 9)

The other day I was in a working group […] to see what is possible. Immediately someone said that it will be impossible to change the airbase into a stage field, like the Americans have.(Interviewee 1)

Being able to change the airbase into a stage field means that after a precautionary landing, a pilot is allowed to take off when the necessary repairs have been done, even if the airbase is not active.

When it comes to changing rules that the RNLAF does have authority over, the process is not widely known, as the interviewees indicated.

I don’t know if we have a procedure for adapting or changing rules. I hope so, but I’m not sure. I should know, but I don’t.(Interviewee 8)

Changing rules is a long, painstaking process. One reason is the lack of capacity for ongoing review and change, and as operators point out, the RNLAF imposes restrictions upon itself. For instance, applicability to all operators takes precedence over rules matching tasks, which requires exceptions. Senior management agree that it takes a lot of effort to have a rule changed.

[It takes great force] to try to change the most important things, and that’s nearly impossible.(Interviewee 5)

According to half of the interviewees, it will need reassessment of the existing rule base and being able to adapt in work situations to resolve this tension.

We continuously need to assess our rule base with a plan-do-check-act loop. Are the rules still valid?(Interviewee 4)

3.3. Enduring Tension

The contradiction between commitment to rules and compliance on the one hand and the need for adaptation and freedom to use expertise on the other hand is apparent in an enduring tension within the RNLAF.

This tension is evident in examples where compliance prevails even if it leads to a riskier situation. For instance, because of airport regulations, a certain number of fire fighters must be on hand when large aircraft with more than two passengers need to land or take off. Large helicopters, however, are allowed to land outside airports, without fire fighters present, due to a distinct set of rules. When not enough fire fighters are available, helicopters will land outside the perimeter of the airport to pick up passengers because the regulations prevent them from executing this task.

Being compliant does not necessarily mean being safe. […] The airport rules do not apply to areas outside airports, but then situation becomes less safe because you move from a bit of fire fighter capacity to none at all.(Interviewee 4)

The tension is also visible in examples in which compliance actually stifles operations. As the interviewees explain, in some instances being compliant means the work is just not finished.

We have an exercise planned which requires me to have an emergency radio. So, I call the responsible department to ask for one. But I won’t get this radio because it was not requested on the right form, even though they have them in stock. After filling out the proper form I do get the radio, but it hasn’t been prepared. I have to load the settings myself, even though that’s the job of the support department. The paperwork is more important than the operational tasks I have to do.(Interviewee 2)

These findings are substantiated by the literature on “malicious compliance”, which is defined as following the rules to the letter resulting in work not being finished or being finished unexpectedly [21].

In other instances, compliance can lead to unintended consequences, but because the rules are adhered to and output is realised, according to the interviewees, unintended consequences are not discussed. For instance, in the Netherlands, rules dictate how often a helicopter is allowed to land at designated helicopter landing spots:

When they get to that number, landing is no longer allowed. This rule is intended to minimise the sound burden for these areas as much as possible. However, the surroundings of these helicopter landing spots fall outside the extent of this rule. That means that helicopters are still allowed to land within as little as a couple of metres of a landing spot, because this falls under the rules of field landings. Obviously, this workaround makes it hard to meet the intent of minimising the sound burden.(Interviewee 10)

Becoming compliant with the intent of this rule would mean hampering task execution, so the unintended consequences are ignored and will not be discussed since literal compliance is realised.

Added to this is the limited interest senior management shows in the challenges posed by rules for daily operation. Senior management is aware of complex situations, but shows no desire to understand or resolve the actual dynamics.

[When discussing complex situations with commanding officers] I have no idea why they don’t. It’s probably human behaviour, [them thinking] I’ve resolved the situation in the easiest way for myself, so why choose the hard way?(Interviewee 8)

Research by Tucker et al. [53] and Morrison [7] seems to substantiate this finding. They found that the short-term success of problem-solving behaviours of operators diminishes the necessity for more structural changes in the organisation.

Senior management sees change in the management of rules as a solution to the enduring tension. Accepting an ill-functioning rule is not an option:

If a rule hampers job execution, then together with rule makers/enforcers you try to find an alternative means of compliance that lets us continue our operation, or [find] a way to deviate from the rules. But the answer can never be ‘No that’s impossible and that’s the end of it’. Not changing a rule is a joint decision, with the operator involved.(Interviewee 6)

Considering the difficulties operators encounter when trying to change rules, it seems as if senior management underestimates how much effort it takes and how unsuccessful these attempts are.

The tension between committing to compliance and the need for adaptation is also seen in the way the RNLAF deals with instances in which operators use their own discretion to decide whether or not to be compliant. Of 12 interviewees, ten explicitly state that choosing to use your own discretion means justifying the course of action afterwards, but having to explain their choice seems contradictory.

Operators don’t cross safety lines […]. You won’t risk your life on a simple training flight.(Interviewee 3)

If they make a decision and can explain it afterwards […] they will be supported.(Interviewee 9)

I am allowed to deviate if it means enhancing the safety of the flight. But I have to prove that safety was enhanced. But that is rather impossible, since I can’t prove what would have happened had I not deviated. However, I have to explain in writing why I deviated from my flight authorisation. If [the explanation] is not accepted I have to go up one level and explain it to the next commanding officer.(Interviewee 2)

The interviewees signal a need for discretionary space, defined by basic rules, in which they can exercise their expertise and judgement as to how to execute the task [54].

According to most interviewees common sense is vital to safety.

Undeniably, every now and then, including deployments, one has to land aircraft in unregulated places. […] We need to train [pilots] and give them the discretionary space to become and stay smart operators.(Interviewee 10)

However, it seems that in some cases, the more rules there are, the less common sense is used, until operators “stop thinking” altogether.

I had this situation where pilots would fly back to the airbase when something was wrong with the aircraft, instead of making a precautionary landing as prescribed in the checklists. So, I addressed this situation and what I saw next was pilots always making a precautionary landing, even when flying back was the more sensible and practical course of action. In other words, they stopped thinking for themselves and simply followed what they saw was an order.(Interviewee 4)

This assertion is supported by Klein [22], who found that becoming comfortable with procedures leads to eroding expertise and the necessity to develop more skills seems to cease.

The tension between compliance and adaptation is exacerbated by the operators’ lack of trust, which inhibits those involved from addressing the fact that the way work is done differs from the way work is prescribed. An explanation for this distrust is the perceived lack of a just culture:

It shows up the just culture, so to speak […] and it does harm, especially when [distrust] is directed at the employees involved. Personally, I think Central Staff and the Inspectorate seem to have an urge to jump at the chance to […] press charges, whatever. That doesn’t help.(Interviewee 12)

Research by Milliken et al. [55], Tucker and Edmondson [56] and Manapragada and Bruk-Lee [57] finds that behaviour of management is related to keeping quiet about safety issues. Previous research shows that even closed accident investigations perceived as judgemental leads to the perception of diminishing social safety [58]. Therefore, the way findings and conclusions are portrayed has an impact beyond the scope of an accident investigation [59], possibly adding to the fear of consequences for being noncompliant.

A recent investigation [60] showed that the RNLAF has a rather judgemental and retributive climate.

Every CO has a CO who also has a CO. Sometimes your CO simply demands you punish someone [after noncompliance], regardless of what you think the best response might be. Especially when something gets picked up by the media or politicians. Then the highest level of our organisation, the secretary and minister of defence exert pressure to respond retributively and this flows through the organisation down to our level.(Supervisor 1 in [60])

Upper management uses what we call a long screwdriver to turn every CO in the hierarchy to the same position, so to speak. This is how they micromanage a situation deep in the capillaries of our organisation. It’s a lack of trust and a refusal to let things go and be dealt with at the appropriate level(Supervisor 7 in [60]).

This same study [60] showed that fear of personal consequences resulted in punishment for noncompliance, even if it was just for show.

His CO said to him: ‘Okay, listen. Remember that incident last year? When the Commission of Inquiry comes, just bend over and take one for the team.’(Focus group 1 in [60])

Previous research [14] shows that if noncompliance is necessary to achieve goals, it is only visible if there is no personal risk involved or if it can be kept hidden from RNLAF senior management.

However, when it comes to safety, operators consider trust a priority. They have no intention to put themselves in danger by crossing safety lines. They do not need rules to tell them to stay safe.

That’s one of the biggest issues in this organisation, the underlying problem, the lack of trust. Trusting the operator to make a decision. This professional knows best. Trust another, [trust] everything we do.(Interviewee 3)

Rule makers/enforcers acknowledge that the organisation sometimes uses rules as a way to “cover its ass”, enabling the appointment of blame if something goes wrong, a finding substantiated by Bye and Aalberg [61].

4. Discussion

The current study has identified that the population of interest considers adherence to rules and procedures important, as our examples have shown. Rules are seen as vital to achieving safety and compliance. This is hardly surprising given the importance many organisations project onto rules [1].

However, the existing rule base does not match the complex and dynamic nature of the work to be done, resulting in a need for adaptation of these rules. Since it is difficult to change rules, employees call on local ingenuity to achieve their goals despite the hampering rules [14].

The public and political commitment to compliance that the DoD leadership makes reinforces a cycle of issuing promises followed by pressure to keep the promise. Formally acknowledging the hindrance of rules and reassessing, possibly deleting, some rules go against the promise to align the way work is done to the way work is prescribed. This limits the freedom of employees to act according to their judgement. The interviewees recognise the importance of rules and procedures. However, they are frequently confronted by rules that hamper task execution or reduce safety and that are hard to change. As research shows, this freedom, and in some cases accompanying non-adherence, may be necessary to resolve an unworkable situation [22]. An accurate perception of this unworkable situation is required [24]. The examples in Section 3 show that operators are very well aware of the hampering aspect of rules and procedures and equally aware of the fact that, in some cases, solutions that adhere to the rules actually reduce safety. They recognise safer ways to perform, yet the rules do not allow this and changing them is too hard. Given the findings by Antonsen et al. [46], what is seen as a safety measure—rules and compliance—might become the opposite.

The crucial pressure on enforcing compliance on the one hand and the need for adaptation and freedom to use expertise on the other creates tension throughout the DoD. This tension is seen in malicious compliance resulting in riskier or stifled operations.

This tension is also seen in expecting an operator to justify, after the act, a deviation carried out for safety reasons and based on expert knowledge, which is a fallacy in itself. Presented as the freedom to deviate from rules in case safety is judged by the expert to be at risk, the expectation of justification shows this as an illusion. If other experts, in hindsight, consider the deviation unnecessary, this use of expert knowledge is relabelled as a violation and the pressure to be compliant intensifies.

Finally, the tension is seen in the unwillingness to challenge the belief in compliance because there is no need for it. As a result of previously discovered local ingenuity [14], the work is finished in spite of hampering rules. Because local ingenuity is non-transparent, the fact that operators have to choose between adherence and performing remains invisible. Hence, there is no incentive to take on the difficult task of trying to change the existing rule base. Overcoming this lack of curiosity in how work is completed would obtain insight into the complexities of daily work as well as the difficulties employees encounter when they try to change rules. Because the belief in compliance is not challenged, operators are left with the tension between having to finish the job while hampered by rules and procedures.

These interpretations might explain the status quo of the differences between procedures and practice and the difficulties encountered when trying to adapt the existing rule base to match work situations. In the DoD’s official safety narrative, compliance with rules is the (one and only) way to achieve safety. This contrasts with the need and desire for freedom, espoused not only by the interviewees, but also in the literature [1,4,22,23], to exploit experience and expertise where rules provide insufficient support to the situation. However, the pressure to sustain this belief after embracing it so widely is simply too large to expect a shift in the compliance paradigm [62].

These findings and interpretations do not, however, seem to tell the whole story. Understanding the remaining of the gaps between work-as-done and work-as-prescribed requires an understanding of the differing interests and focus of the diverse levels. If these are too far apart, every effort undertaken to align procedures and practice is likely to fail.

Perceived at the top of the population of interest, the DoD is a political instrument that makes political promises that require political support. The press and budgetary debates are among its biggest threats. Regarding the latter, the DoD has suffered from a decade of budget cuts, while the political ambition and expected output have remained the same. Making sure nothing jeopardises the received budget seems a good motivation to stick to promises as much as possible. The DoD often acts as a social role model, as demonstrated by its recruitment advertising. This leads to a kind of moral superiority, expected by both politicians and society: soldiers are outstanding, moral, compliant citizens who represent an organisation that goes by the book. Compliance in itself is not that important; it is the promise of compliance that is vital.

For RNLAF senior management, the interests are a little different. Adhering to the compliance narrative is important because they feel political pressure at their level as well. Breaking the political promise with noncompliance might have negative consequences, especially when the RNLAF needs to compete with other military forces for its annual budget. However, it is still expected to produce output (airpower). To achieve this, the RNLAF needs to be able to train-as-you-fight, preferably without the hindrance of rules and procedures. This means that, while appearing to be compliant, senior management needs either to condone noncompliance or not be curious as to how work is done, leading to a two-faced Janus situation; senior management expresses both the need for compliance as well as the need to do what is necessary to finish the job, without reflecting on or even recognising the contradiction. It seems that holding two contradicting views has become a subconscious routine. This results in the difference found between what is carried out within the RNLAF and what it promises the outside world: constant compliance.

At the operator level, the DoD/RNLAF is a military organisation with violence, i.e., airpower, as one of the most important means. Here, the focus is on well-trained employees who can be deployed in any situation. Training-as-they-fight is the interest found at this level. Finishing the job needs adaptation, as seen in the local ingenuity adopted [14]. Compliance is important in situations where adhering to rules avoids serious physical risks for aircrew. More important, however, is avoiding personal liability or accountability. The fear of personal liability is aggravated by the perceived lack of a just culture. Combined, these findings provide a reason to refrain from transparency regarding the differences between practice and paper. Political support and the media are not the concern of operators. The division between budget and societal expectations are of some concern.

Every level of the RNLAF considers compliance important. However, our data suggests that, when going “down” the hierarchy from the political top to senior management to operator, there is a gradient in the explicit nature of our informants’ willingness and ability to acknowledge this. Conceding that compliance is secondary to resolving things increases closer to operational levels. For senior management, the interest in retaining an image of a smaller distance between the way work is carried out and prescribed seems governed by political pressure; for operators “getting stuff done” [21] may even be a source of professional pride of their workmanship [14,63,64].

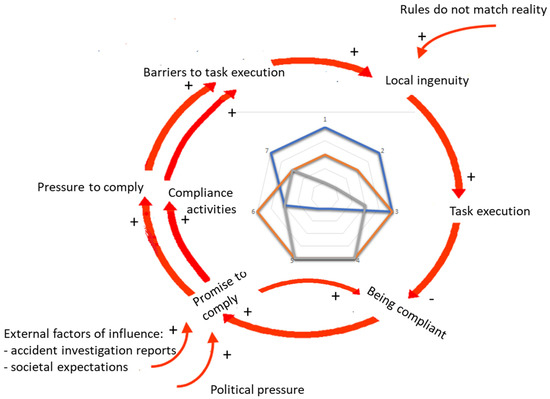

Visually depicting the emergence of differing interests (Figure 1) shows how the levels diverge in their focus.

Figure 2 was created to model the differences in focus, showing a framework of interests. It is not underpinned by a quantitative analysis. The figure shows that the need for adaptation demands local ingenuity in task execution, which means, however, less compliance. External evaluations combined with pressure from the political top results in the dual promise not only to be compliant but also to enhance compliance. This leads to more acts of compliance and increasing pressure to adhere to these promises, thus hindering task execution since rules and procedures often do not match the practice. Hence, local ingenuity is needed again to finish the job. Looking at the seven themes arising from this research—political support, press, budget, train-as-you-fight, personal liability, compliance, and societal expectations—we can map the differing interests and focus in a spider diagram. As depicted, there is considerable difference between the focus of the levels, with RNLAF senior management functioning as a buffer between the political top and the operators with regard to political support and train-as-you-fight.

Figure 2.

Different interests explaining the enduring differences between the way work is done and prescribed. The outer circle shows the emergence and reinforcing of the two contradictory views regarding compliance/adaptation. The spider diagram the middle shows the different interests of the political top in blue, the senior management of the RNLAF in orange and the operators in grey on seven themes: 1 = political support; 2 = press; 3 = budget; 4 = train-as-you-fight; 5 = personal liability; 6 = compliance; 7 = societal expectations.

Reflecting on these findings and interpretations pinpoints a fear underscoring the interest in maintaining the difference between the way work is done and prescribed. The official safety narrative seems to convey a hidden message—bad things happen to bad people; in other words, if you do not obey (comply), you face bad things (personal consequences or accidents). This fear, arising from the threat of punishment, is reminiscent of a bogeyman, which provides an excellent metaphor. The idea of a bogeyman is eerily consistent with humanity’s deference throughout the Common Era to some mythical functionary appointed to help govern the system, to ensure “good behaviour”, specifically to monitor and test human beings in it [65].

As is commonly found in bogeyman stories, the personal consequences for being bad (not 100% compliant) remain unclear. In this case, they can be deduced from the occasional sacrifice made to sustain the compliance belief, as seen in the resignation of both the minister of defence and the chief of defence [40,41] as well as lower down the organisation [60]. However, these were personal choices by political and military command to resign and choices within the DoD to punish people. It is unclear what would have happened had those choices not been made, leading to the question of whether the bogeyman’s fear of noncompliance is justified.

One opportunity to resolve the described tension is to embrace the pursuit of a “fifth-generation air force” (5GAF) to counter unrealistic expectations about compliance, and advance the use of expertise, common sense thinking and trust in operators. As Hale and Borys explain, the current aim to form a 5GAF contradicts the commitment to a compliance paradigm [1]. The focus on compliance leaves little room for using expert judgement and hence ownership and agility.

Realising a 5GAF might include a doctrine change, as investigated by Jahn [66]. He reports on a sudden doctrine change at the United States Forest Service where regulations changed overnight from prescriptive rules to guidelines. No extra rules were created, just a different interpretation of the existing rule base. The change gave operators more discretionary space and the professional judgement of the operators actually doing the work takes preference over rules made at a great distance from the place of work. Supportive modifications were also made to the investigation process and leadership training. Jahn’s results [66] are supported by research on the use of professional expertise by forest rangers [Kaufman, 1960 in [39]] and sailors [9].

5. Conclusions

This research shows that—across multiple levels and roles—the RNLAF might desire to align work-as-done with work-as-prescribed and breach the status quo of gaps between the two. Its attempts to do so, however, will likely remain stymied because of a forceful dynamic balance of interests that both produce and retain the status quo, while offering all stakeholders outwardly legitimate ways to elide its existence. We found that the higher-up leaders walk a tightrope, maintaining the opportunity for differences between the way work is done and prescribed, but agreeing superficially with the compliance focus and when undesired results become officially known, as with incidents and accidents. Additionally, although minor attempts are made to gain discretionary space and fewer rules, these are unsuccessful, because the pressure to keep the promise of compliance makes change unlikely. What we found was not only a self-sustaining force field of interests that simultaneously retains and denies noncompliance at almost all hierarchical levels we studied, but also the routine invocation of a nondescript organisational force-to-be-feared—reminiscent of a bogeyman—in case noncompliance was discovered. Efforts to solve the gaps between work as done and prescribed should be directed at this bogeyman: the belief system that compliance equals safety, adhered to by politics and the public and given lip service by military leaders. By pressuring employees into compliance, we keep feeding the bogeyman, until the fear of freedom to exercise professional autonomy stifles the entire organisation. This study shows how the achievement of 5GAF behaviour and culture is hampered due to the enduring differences between the way work is done and prescribed. What could provide a solution is a change in doctrine so that rules as principles become rules as guidelines, embracing the ideals of the 5GAF. Further and deeper ethnographic research will be needed beyond the present paper to form a thorough understanding of the function and role of the “bogeyman” in sustaining concurrent acquiescence and noncompliance.

6. Limitations and Strengths

This study has both strength and limitations to consider. The use of a qualitative thematic analysis with a focus on exnovation enabled us to explain the consequences of two conflicting paradigms held in the same organisation. The qualitative methodology, using transcripts of semi-structured interviews and document analysis, provided a rich data set that shows the complexities and dynamics of everyday work hampered by the compliance paradigm. The official perspective of the DoD/RNLAF substantiated the perceptions of the interviewees.

Our research team, combining one researcher (LB) working for the RNLAF and external researchers, ensured a good mix of thorough knowledge of the DoD and RNLAF cultures and the tension between compliance and need for adaptation on the one hand and critical thinking on the other hand [67]. This ensured both the understanding and theoretical underpinning of the phenomena found.

However, the interviewee sample consisted of employees of a single organisation in the RNLAF and the chain of command following from the population of interest. Of concern are the sample size and representativeness of this sample. The sampling, however, was purposeful [68]. The sample size was deemed acceptable because no new information was provided, indicating a saturation point [36].

The DoD and RNLAF face considerable external pressure to uphold the compliance paradigm. This means that the results of this study might not be generalisable to organisations in a different setting.

Nonetheless, although there is a significantly growing amount of research into the difference between the way work is done and prescribed, less is known about the reasons for maintaining these enduring differences, i.e., the various interests that reside in an organisation, and the resulting tensions. This study contributes to the theory by providing insight into these interests and stakes found in the Dutch DoD to retain these differences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.B.-H., R.J.D.B., V.S. and S.W.A.D.; methodology, L.B.-H., V.S. and R.J.D.B.; validation, L.B.-H., R.J.D.B. and V.S.; formal analysis, L.B.-H., R.J.D.B. and V.S.; investigation, L.B.-H.; resources, L.B.-H.; data curation, L.B.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.-H., R.J.D.B., V.S. and S.W.A.D.; writing—review and editing, L.B.-H., R.J.D.B., V.S. and S.W.A.D.; visualization, L.B.-H. and V.S.; supervision, S.W.A.D.; project administration, L.B.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Technology Delft (date of approval: 22 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All anonymized or aggregated data will be uploaded to 4TU.ResearchData with public access. Due to security/confidentiality reasons only a subset of the generated data will be made available. To access the full data a formal request can be made to the Department of Defence of The Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the employees of the operational flight squadron studied for participating in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hale, A.; Borys, D. Working to rule, or working safely? Part 1: A state of the art review. Saf. Sci. 2013, 55, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. Resilience engineering and the systemic view of safety at work: Why work-as-done is not the same as work-as-imagined. In Proceedings of the Arbeitssysteme, 58. Kongress der Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaft, Kassel, Germany, 22–24 February 2012; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bieder, C.; Bourrier, M. Trapping Safety into Rules: How Desirable or Avoidable Is Proceduralization? Ashgate Publishing Co.: Farnham, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781409452263. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S.W.A. Failure to adapt or adaptations that fail: Contrasting models on procedures and safety. Appl. Ergon. 2003, 34, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoiseaux-Volman, B.A.; Medlock, S.; van der Eijk, M.D.; Romijn, J.A.; Abu-Hanna, A.; van der Velde, N. Falls and delirium in older inpatients: Work-as-imagined, work-as-done and preferences for clinical decision support systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, E.L. Cognition in the Wild; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, B. The problem with workarounds is that they work: The persistence of resource shortages. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 39–40, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rochlin, G.I.; La Porte, T.R.; Roberts, K.H. The Self-Designing High-Reliability Organization: Aircraft Carrier Flight Operations at Sea. Nav. War Coll. Rev. 1987, 40, 75–90. Available online: http://www.caso-db.uvek.admin.ch/Documents/MTh_SM_22.pdf%5Cnpapers3://publication/uuid/62B6CC6F-7E71-4540-94CB-32E1575D24CA (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Woods, D.D.; Shattuck, L.G. Distant Supervision-Local Action Given the Potential for Surprise. Cogn. Technol. Work 2000, 2, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onderzoeksraad voor de Veiligheid. Draadaanvaring Apache-Helikopter Tijdens Nachtvliegen (Wire Strike during Apache-Helicopter Night Flight); Onderzoeksraad voor de Veiligheid: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018.

- Reason, J. The Human Contribution. Unsafe Acts, Accidents and Heroic Recoveries; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moppett, I.K.; Shorrock, S.T. Working out wrong-side blocks. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boskeljon-Horst, L.; De Boer, R.J.; Sillem, S.; Dekker, S.W.A. Goal Conflicts, Classical Management and Constructivism: How Operators Get Things Done. Safety 2022, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsen, S.; Skarholt, K.; Ringstad, A.J. The role of standardization in safety management—A case study of a major oil & gas company. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.; Corrigan, S.; Ward, M. Well-intentioned people in dysfunctional systems. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Human Error, Safety and Systems Development, Newcastle, Australia, 1 January 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, R. Not working to rule: Understanding procedural violations at work. Saf. Sci. 1998, 28, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.B.; Wakefield, D.; Wakefield, B. Work-arounds in health care settings: Literature review and research agenda. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.L.; Zheng, S.; Gardner, J.W.; Bohn, R.E. When do workarounds help or hurt patient outcomes? The moderating role of operational failures. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, S.W.A. Safety Differently. Human Factors for a New Era; Apple Academic Press Inc.: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, S.W.A. The Safety Anarchist; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G. Streetlight and Shadows: Searching for the Keys to Adaptive Decision Making; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Besnard, D.; Hollnagel, E. I want to believe: Some myths about the management of industrial safety. Cogn. Technol. Work 2014, 16, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnard, D.; Greathead, D. A cognitive approach to safe violations. Cogn. Technol. Work 2003, 5, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defensie. 5e Generatie Luchtmacht—Wat Houdt Het in? Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5p9KXOrJbak (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and Safety-II The Past and Future of Safety Management; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, J.R. The researcher as instrument: Learning to conduct qualitative research through analyzing and interpreting a choral rehearsal. Music Educ. Res. 2007, 9, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Uliassi, C. “Researcher-As-Instrument” in Qualitative Research: The Complexities of the Educational Researcher’s Identities. Qual. Rep. 2022, 27, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, S.L.; Lane, J.; Tan, C. Researcher as instrument: A critical reflection using nominal group technique for content development of a new patient-reported outcome measure. Int. Pract. Dev. J. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie. Veiligheid in de Lucht. In Onderzoek naar Een Zelfbeschieting van Een F-16 Boven de Vliehors; Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020. Available online: http://www.ivd.nl (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie. Veilig over Land en Door de Lucht. Onderzoek naar Maatregelen voor Het Vervoer van Gevaarlijke Stoffen Door Defensie; Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020. Available online: http://www.ivd.nl (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie. Risico’s Onderkend? Onderzoek naar Een Blikseminslag op Oefenterrein Ossendrecht 19 Juni 2019; Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021; Available online: http://www.ivd.nl (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie. Sterker Reageren op Zwakke Signalen. Onderzoek naar de Signaalfunctie van Lichte Voorvallen; Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: http://www.ivd.nl (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie. Luchtvaartongeval NH-90. Onderzoek naar Luchtvaartongeval NH-90 Aruba 19 Juli 2020; Inspectie Veiligheid Defensie: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021; Available online: http://www.ivd.nl (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Charmaz, K. A Constructivist Grounded Theory Analysis of Losing and Regaining a Valued Self. In Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis: Phenomenological Psychology, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquirey; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalberti, R.; Vincent, C.; Auroy, Y.; De Saint Maurice, G. Violations and migrations in health care: A framework for understanding and management. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, i66–i71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, S.W.A. Compliance Capitalism: How Free Markets Have Led to Unfree, Overregulated Workers; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keultjes, H. Minister Hennis treedt af om fataal mortierongeval Mali. Het Parool 2017.

- Waarom minister Hennis moet aftreden. Trouw, 3 October 2017.

- Dekker, S.W.A. The bureaucratization of safety. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichbrodt, J. Safety rules as instruments for organizational control, coordination and knowledge: Implications for rules management. Saf. Sci. 2015, 80, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, D. Safety rules and regulations on mine sites—The problem and a solution. J. Saf. Res. 2005, 36, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, Ø. Safety compliance in a highly regulated environment: A case study of workers’ knowledge of rules and procedures within the petroleum industry. Saf. Sci. 2013, 60, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsen, S.; Almklov, P.; Fenstad, J. Reducing the gap between procedures and practice—lessons from a succesful safety intervention. Saf. Sci. Monit. 2008, 12, 1–16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229005586 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Carim, G.C.; Saurin, T.A.; Havinga, J.; Rae, A.; Dekker, S.W.A.; Henriqson, É. Using a procedure doesn’t mean following it: A cognitive systems approach to how a cockpit manages emergencies. Saf. Sci. 2016, 89, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, P.V.R.; Righi, A.W.; Huber, G.J.; de F. Lemos, C.; Jatoba, A.; Gomes, J.O. Reflections on work as done (WAD) and work as imagined (WAI) in an emergency response organization: A study on firefighters training exercises. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 68, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minister van Defensie. Procedures en Regels Bemoeilijken Aanpak Cyberaanvallen; Informatiebeveiliging: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2022.

- Tucker, A.L. The impact of operational failures on hospital nurses and their patients. J. Oper. Manag. 2004, 22, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.G.; Schneider, B. Serving multiple masters: Role conflict experienced by service employees. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Sonenshein, S. Toward the Construct Definition of Positive Deviance. Am. Behav. Sci. 2004, 47, 828–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.L.; Edmondson, A.C.; Spear, S. When problem solving prevents organizational learning. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2002, 15, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iszatt-White, M. Catching them at it: An ethnography of rule violation. Ethnography 2007, 8, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, F.J.; Morrison, E.W.; Hewlin, P.F. An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1453–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, A.L.; Edmondson, A.C. Why Hospitals Don’t Learn from Failures: Organizational and Psychological Dynamics that Inhibit System Change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manapragada, A.; Bruk-Lee, V. Staying silent about safety issues: Conceptualizing and measuring safety silence motives. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 91, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alta, M. Het Effect van Voorvalonderzoek op de Beleving van Sociale Veiligheid van Direct Betrokken Defensiemedewerkers; Nederlandse Defensie Academie: Breda, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alta, M.; Boskeljon-Horst, L. Voorvalonderzoek contraproductief? De negatieve impact op sociale veiligheid en lerend vermogen. Mil. Spect. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Boskeljon-Horst, L.; Snoek, A.; van Baarle, E. Learning fom the complexities of fostering a restorative just culture in practice within the Royal Netherlands Air Force. Saf. Sci. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, R.J.; Aalberg, A.L. Why do they violate the procedures?—An exploratory study within the maritime transportation industry. Saf. Sci. 2020, 123, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, A.; Provan, D. Safety work versus the safety of work. Saf. Sci. 2019, 111, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, W.E. Out of the Crisis; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Morel, G.; Amalberti, R.; Chauvin, C. Articulating the differences between safety and resilience: The decision-making process of professional sea-fishing skippers. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, H.A. Satan: A Biography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, J.L.S. Shifting the safety rules paradigm: Introducing doctrine to US wildland firefighting operations. Saf. Sci. 2019, 115, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden-Biddle, K.; Locke, K. Appealing Work: An Investiation of How Ethnographic Texts Convince. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.K.; Gregory, D.M. EBN users’ guide: Evaluation of qualitative research studies Clinical scenario. Evid.-Based Nurs. 2003, 6, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).