Effective Interprofessional Communication for Patient Safety in Low-Resource Settings: A Concept Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

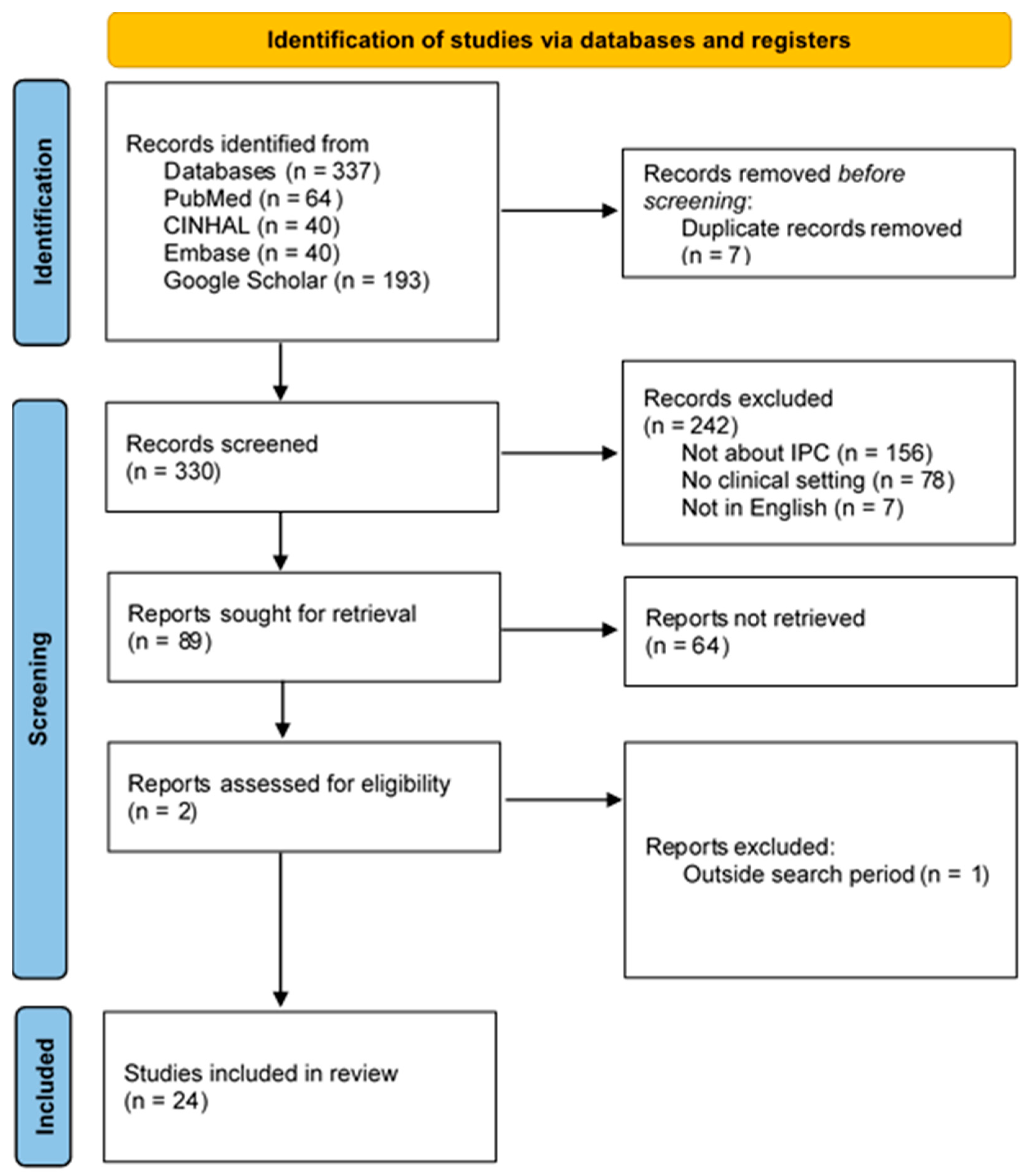

2.2. Literature Search

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Defining the Concept of Effective Interprofessional Communication and Related Definitions

3.2. Illustration of Defining Attributes, Antecedents, and Consequences

3.3. Defining Attributes of the Concept

3.3.1. Clarity

3.3.2. Completeness

3.3.3. Accuracy

3.3.4. Timeliness

3.3.5. Consistency

3.3.6. Openness

3.3.7. Collaboration

3.3.8. Information Sharing

3.4. Construction of Model, Borderline, Relative, and Contrary Cases

3.4.1. Model Case

Analysis

3.4.2. Borderline Case

Analysis

3.4.3. Contrary Case

Analysis

3.4.4. A Related Case

Analysis

3.5. Antecedents of Effective Interprofessional Communication

3.5.1. A Strong Leadership Commitment

3.5.2. Positive Teamwork Among Health Professionals

3.5.3. Mutual Trust

3.5.4. Education and Training

3.6. The Consequences of Effective Interprofessional Communication

3.7. Operational Definition of Effective Interprofessional Communication

4. Discussion

4.1. Empirical Referents

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSQHC | Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care |

| AE | Adverse Event |

| AHRQ | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

| COHSASA | Council of Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa |

| CPD | Continuous Professional Development |

| HER | Electronic Health Record |

| HCP | Healthcare professionals |

| IPC | interprofessional communication |

| IPSG | International Patient Safety Goals |

| JCI | Joint Commission International |

| LIC | Low-income country |

| LRS | Low-resource settings |

| PEWS | Pediatric Early Warning Score |

| PS | Patient Safety |

| SBAR | Situation-Background-Assessment- Recommendation |

| TeamSTEPPS | Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Alhur, A.; Alhur, A.A.; Al-Rowais, D.; Asiri, S.; Muslim, H.; Alotaibi, D.; Al-Rowais, B.; Alotaibi, F.; Al-Hussayein, S.; Alamri, A.; et al. Enhancing Patient Safety Through Effective Interprofessional Communication: A Focus on Medication Error Prevention. Cureus 2024, 16, e57991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chance, E.A.; Florence, D.; Abdoul, I.S. The effectiveness of checklists and error reporting systems in enhancing patient safety and reducing medical errors in hospital settings: A narrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2024, 11, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietl, J.E.; Derksen, C.; Keller, F.M.; Lippke, S. Interdisciplinary and interprofessional communication intervention: How psychological safety fosters communication and increases patient safety. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1164288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, L.; Hoffman, K.; Levett-Jones, T.; Gilligan, C. “They have no idea of what we do or what we know”: Australian graduates’ perceptions of working in a health care team. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2014, 14, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Commission International. International Patient Safety Goals. Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/en/standards/international-patient-safety-goals (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Tiwary, A.; Rimal, A.; Paudyal, B.; Sigdel, K.R.; Basnyat, B. Poor communication by health care professionals may lead to life-threatening complications: Examples from two case reports. Wellcome Open Res. 2019, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/policy/global-patient-safety-action-plan (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Kumah, A. Poor quality care in healthcare settings: An overlooked epidemic. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1504172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveling, E.-L.; Kayonga, Y.; Nega, A.; Dixon-Woods, M. Why is patient safety so hard in low-income countries? A qualitative study of healthcare workers’ views in two African hospitals. Glob. Health 2015, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masefield, S.C.; Msosa, A.; Grugel, J. Challenges to effective governance in a low income healthcare system: A qualitative study of stakeholder perceptions in Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, C.; Ng, C.H.; Koh, J.W.H.; Ong, Z.H.; Ghazali, H.Z.B.; Tan, L.H.E.; Ong, Y.T.; Cheong, C.W.S.; Chin, A.M.C.; Mason, S.; et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; van Diggele, C.; Roberts, C.; Mellis, C. Teaching clinical handover with ISBAR. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.L.; Brown, M. SBAR as a Standardized Communication Tool for Medical Laboratory Science Students. Lab. Med. 2021, 52, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Commission International. Communicating Clearly and Effectively to Patients. Available online: https://store.jointcommissioninternational.org/assets/3/7/jci-wp-communicating-clearly-final_(1).pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Madula, P.; Kalembo, F.W.; Yu, H.; Kaminga, A.C. Healthcare provider-patient communication: A qualitative study of women’s perceptions during childbirth. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosman, S.L.; Daneau Briscoe, C.; Rutare, S.; McCall, N.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Unyuzumutima, J.; Uwamaliya, A.; Hitayezu, J. The impact of pediatric early warning score and rapid response algorithm training and implementation on interprofessional collaboration in a resource-limited setting. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyoni, C.N.; Grobler, C.; Botma, Y. Towards Continuing Interprofessional Education: Interaction patterns of health professionals in a resource-limited setting. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeney, E.A.R.; Chu, F.; White, A.A.; Smith, G.R., Jr.; Woodward, K.; Lavallee, D.C.; Salas, R.M.E.; Beaird, G.; Willgerodt, M.A.; Dang, D.; et al. A scoping review of new implementations of interprofessional bedside rounding models to improve teamwork, care, and outcomes in hospitals. J. Interprof. Care 2024, 38, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Fund. Audit Report Global Fund Grants to the Republic of Malawi. GF-OIG-16-024, Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/2665/oig_gf-oig-16-024_report_en.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Barpanda, S.; Saraswathy, G. The Impact of Excessive Workload on Job Performance of Healthcare Workers during Pandemic: A Conceptual Mediation—Moderation Model. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Res. 2023, 10, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.J.; Slade, D.; Dahm, M.R.; Brady, B.; Roberts, E.; Goncharov, L.; Taylor, J.; Eggins, S.; Thornton, A. Improving patient-centred care through a tailored intervention addressing nursing clinical handover communication in its organizational and cultural context. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Francisco, D.H.; Duarte-Clíments, G.; del Rosario-Melián, J.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Romero-Martín, M.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B. Influence of Workload on Primary Care Nurses’ Health and Burnout, Patients’ Safety, and Quality of Care: Integrative Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittalis, C.; Brugha, R.; Bijlmakers, L.; Cunningham, F.; Mwapasa, G.; Clarke, M.; Broekhuizen, H.; Ifeanyichi, M.; Borgstein, E.; Gajewski, J. Using Network and Complexity Theories to Understand the Functionality of Referral Systems for Surgical Patients in Resource-Limited Settings, the Case of Malawi. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 11, 2502–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moureaud, C.; Hertig, J.B.; Weber, R.J. Guidelines for Leading a Safe Medication Error Reporting Culture. Hosp. Pharm. 2020, 56, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, M.; Harrison, M.C. The structured communication tool SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation) improves communication in neonatology: Forum—Clinical practice. S. Afr. Med. J. 2014, 104, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyan, A.; Kinkler, G.; Cidav, Z.; Kang-Yi, C.; Eiraldi, R.; Salas, E.; Wolk, C.B. Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) to Improve Collaboration in School Mental Health: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Hybrid Effectiveness-Implementation Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e26567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arteaga, G.M.; Bacu, L.; Franco, P.M.; Arteaga, G.M.; Bacu, L.; Franco, P.M. Patient Safety in the Critical Care Setting: Common Risks and Review of Evidence-Based Mitigation Strategies. In Contemporary Topics in Patient Safety—Volume 2; IntechOpen: London. UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/84237 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Anderson, H.M. ScholarWorks Effective Communication and Teamwork Improve Patient Safety. Doctoral Dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2017. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/4196 (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing, 6th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA; Boston, MA, USA, 2019; 262p. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Thinking with Concepts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970; 186p. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford English Dictionary. Available online: https://www.oed.com/?tl=true (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Cambridge English Dictionary—APK Download for Android. Available online: https://dictionary-cambridge-learning-cambridge-university-press.en.aptoide.com/app (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Collins English Dictionary|Latest New Word Suggestions. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/submissions/latest/2024 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, B.U.; Neuspiel, D.R.; Fisher, E.R.S.; Franklin, W.; Adirim, C.T.; Bundy, D.G.; Ferguson, L.E.; Gleeson, S.P.; Leu, M.; Mueller, B.U.; et al. Principles of pediatric patient safety: Reducing harm due to medical care. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atinga, R.A.; Gmaligan, M.N.; Ayawine, A.; Yambah, J.K. “It’s the patient that suffers from poor communication”: Analyzing communication gaps and associated consequences in handover events from nurses’ experiences. SSM—Qual. Res. Health 2024, 6, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Veenstra, J.; Yoon, S. Improving interprofessional communication: Conceptualizing, operationalizing and testing a healthcare improvisation communication workshop. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 119, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, M.d.A.; Carneiro, C.T.; Bezerra, M.A.R.; Rocha, R.C.; da Rocha, S.S. Effective Communication Strategies Among Health Professionals in Neonatology: An Integrative Review—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/378d9161e2fd5c4d0f5d79235e403ab6/1?cbl=2035786&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Campbell, D.P.; Torrens, C.; Pollock, D.A.; Maxwell, P.M. A Scoping Review of Evidence Relating to Communication Failures that Lead to Patient Harm; Glasglow Caledonia Univeristy: Glasglow, Scotland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Etherington, C.; Wu, M.; Cheng-Boivin, O.; Larrigan, S.; Boet, S. Interprofessional communication in the operating room: A narrative review to advance research and practice. Can. J. Anaesth. J. Can. Anesth. 2019, 66, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüner, B.; Derksen, C.; Schmiedhofer, M.; Lippke, S.; Riedmüller, S.; Janni, W.; Reister, F.; Scholz, C. Reducing preventable adverse events in obstetrics by improving interprofessional communication skills—Results of an intervention study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepkosgei, J.; English, M.; Adam, M.B.; Nzinga, J. Understanding intra- and interprofessional team and teamwork processes by exploring facility-based neonatal care in kenyan hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, E.; Bucknall, T.; Woodward-Kron, R.; Hughes, C.; Jorm, C.; Ozavci, G.; Joseph, K. Interprofessional and Intraprofessional Communication about Older People’s Medications across Transitions of Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistri, I.U.; Badge, A.; Shahu, S. Enhancing Patient Safety Culture in Hospitals. Cureus 2023, 15, e51159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Couper, I. Preparing Graduates for Interprofessional Practice in South Africa: The Dissonance Between Learning and Practice. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 594894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olino, L.; Gonçalves, A.d.C.; Strada, J.K.R.; Vieira, L.B.; Machado, M.L.P.; Molina, K.L.; Cogo, A.L.P. Effective communication for patient safety: Transfer note and Modified Early Warning Score. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2019, 40, e20180341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornrattanakavee, P.; Srichan, T.; Seetalarom, K.; Saichaemchan, S.; Oer-areemitr, N.; Prasongsook, N. Impact of interprofessional collaborative practice in palliative care on outcomes for advanced cancer inpatients in a resource-limited setting. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, F.; Lu, F.; Gustafsson, L.; MacArthur, C.; Cummins, C.; Coker, I.; Wilson, A.; Mane, K.; Manneh, K.; Manaseki-Holland, S. Clinical handover communication at maternity shift changes and women’s safety in Banjul, the Gambia: A mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.; Snowden, V. Promoting Communication and Safety Through Clear and Concise Discharge Orders. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toumi, D.; Dhouib, W.; Zouari, I.; Ghadhab, I.; Gara, M.; Zoukar, O. The SBAR tool for communication and patient safety in gynaecology and obstetrics: A Tunisian pilot study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiya, M.N.; Sibiya, M.N. Effective Communication in Nursing. In Nursing; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Thomas, S. Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) Communication Tool for Handoff in Health Care—A Narrative Review. Saf. Health 2018, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amore, J.D.; Mccrary, L.K.; Denson, J.; Li, C.; Vitale, C.J.; Tokachichu, P.; Sittig, D.F.; Mccoy, A.B.; Wright, A. Clinical data sharing improves quality measurement and patient safety. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musheke, M.M.; Phiri, J. The Effects of Effective Communication on Organizational Performance Based on the Systems Theory. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 9, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.; Edwards, A.; Williams, H.; Evans, H.P.; Avery, A.; Hibbert, P.; Makeham, M.; Sheikh, A.; Donaldson, L.J.; Carson-Stevens, A. Sources of unsafe primary care for older adults: A mixed-methods analysis of patient safety incident reports. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulfiyanti, D.; Satriana, A. The Correlation between the use of the SBAR Effective Communication Method and the Handover Implementation of Nurses on Patient Safety. Int. J. Public Health Excell. IJPHE 2022, 2, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Whittam, S.; Thornton, A.; Goncharov, L.; Slade, D.; McElduff, B.; Kelly, P.; Law, C.K.; Walsh, S.; Pollnow, V.; et al. The ACCELERATE Plus (assessment and communication excellence for safe patient outcomes) Trial Protocol: A stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial, cost-benefit analysis, and process evaluation. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaelber, D.C.; Bates, D.W. Health information exchange and patient safety. J. Biomed. Inform. 2007, 40, S40–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-La-Riva, M.E.; Fernández-Bedoya, V.H.; Suyo-Vega, J.A.; Ocupa-Cabrera, H.G.; Grijalva-Salazar, R.V.; Ocupa-Meneses, G.D.D. Enhancing Healthcare Efficiency: The Relationship Between Effective Communication and Teamwork Among Nurses in Peru. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulińska, J.; Rypicz, Ł.; Zatońska, K. The Impact of Effective Communication on Perceptions of Patient Safety—A Prospective Study in Selected Polish Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.P.; Mitchell, S.A.; Weston, J.; Dragon, C.; Luthra, M.; Kim, J.; Stoddard, H.A.; Ander, D.S. SBAR-LA: SBAR Brief Assessment Rubric for Learner Assessment. MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2021, 17, 11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgener, A.M. Enhancing Communication to Improve Patient Safety and to Increase Patient Satisfaction. Health Care Manag. 2017, 36, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Authors & Year | Country | Study Title | Attributes | Antecedents | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alhur et al. (2024) [1] | Saudi Arabia | Enhancing Patient Safety Through Effective Interprofessional Communication: A Focus on Medication Error Prevention | The accuracy of information exchanged is vital. | Standardized communication protocols and interprofessional meetings have improved healthcare discussions. Targeted training programs focus on skill development, while technology boosts communication effectiveness. | Structured communication platforms can significantly reduce medication errors in hospitals. Workload and time constraints often compromise care quality. |

| 2. | Atinga et al. (2024) [36] | Ghana | “It’s the patient that suffers from poor communication”: Analyzing communication gaps and associated consequences in handover events from nurses’ experiences | Incomplete documentation and substandard record-keeping practices were found to delay care | Work ethics, lack of exposure to training on clinical communication skills, absence of formal handover procedures, and environmental hygiene affect communication during clinical shift changes. | Unwanted and unproductive distractions can dramatically increase the risk of medical errors (diagnostic and treatment errors), complications, and extended hospitalizations. |

| 3. | Aveling et al. (2015) [9] | Two East African countries (At the request of study participants, the countries are not named) | Why is patient safety so hard in low-income countries? A qualitative study of healthcare workers’ views in two African hospitals | Although staff felt there was cooperation within professions, weak communication and coordination between professions, teams was frequently described. | Inadequate training and limited opportunities, a Shortage of material resources, cause poor patient care | Lack of materials (including low staffing levels and perceived deficits in the competences of staff) and equipment affected patient safety due to High turnover of staff, associated with staff dissatisfaction, |

| 4. | Bender et al. (2022) [37] | United States of America | Improving interprofessional communication: Conceptualizing, operationalizing, and testing a healthcare improvisation communication workshop | The healthcare improvisation communication workshop, focusing on presence, acceptance, and trust, offers a framework for effective interprofessional communication and collaboration. | The study found that training helps in achieving learning gains and behavior change in interdisciplinary communication and collaboration | When staff receive training, it ensures the delivery of high-quality, patient-centered care. |

| 5. | Blakeney et al. (2024) [18] | United States of America | A scoping review of new implementations of interprofessional bedside rounding models to improve teamwork, care, and outcomes in hospitals | Consistency, Information sharing and collaboration are attributes of effective bedside rounds | Positive teamwork among health professionals can improve patient outcomes | Several articles linked better communication between interprofessional teams and patients or families during rounds to improved patient outcomes. |

| 6. | Brito et al. (2022) [38] | Brazil | Effective communication strategies among health professionals in Neonatology: An integrative review | Communication failures include excessive or reduced information, limited questions, inconsistent or erroneous information, lack of standardization, illegible records, and interruptions. | Care team integration, information verification, computerized systems, systematic handoffs, multidisciplinary rounds, sector transitions, and regular team meetings lead to effective communication | Adoption of the SBAR tool is associated with an improvement in communication among the professionals and in the quality and safety of patient care in Neonatology |

| 7. | Campbell et al. (2018) [39] | United Kingdom | A scoping review of evidence relating to communication failures that lead to patient harm | Timeliness, legibility, content, layout, and ambiguity in hospital letters were believed to increase the risk of prescribing errors in communication between primary and secondary care. | Shared patient care planning and decision-making helped to ensure collective ownership of the patient, bringing members of each team together. In some cases, intensivists assumed ownership and responsibility without further consultation. | The majority of studies in this category were judged to have resulted in severe patient harm, with one study linking communication failures to death |

| 8. | Dietl et al. (2023) [3] | Germany | Interdisciplinary and interprofessional communication intervention: How psychological safety fosters communication and increases patient safety | The study highlighted teamwork as an important aspect of achieving patient safety | Interpersonal and interprofessional training is the foundation of interprofessional communication and collaboration in the context of patient safety | Perceived patient safety risks decreased post-training |

| 9. | Etherington et al. (2019) [40] | Canada | Interprofessional communication in the operating room: a narrative review to advance research and practice | Open communication and teamwork are attributes of interprofessional communication in the operating room. | Structured and standardized communication increases accuracy and understanding between team members. Institutional culture and information sharing by team members are vital for establishing a common understanding of the situation, treatment plan, and individual roles. | A flat hierarchy in institutional culture promotes open communication among team members, improving patient safety. Preoperative briefings with checklists enhance teamwork, identify hazards, and reduce surgical complications. |

| 10. | Huener et al. (2023) [41] | Germany | Reducing preventable adverse events in obstetrics by improving interprofessional communication skills—Results of an intervention study | Problems in administering treatment in time and failure to provide complete information hinder IPC (Timeliness and completeness) | Integration of communication tools into interprofessional training alongside medical emergency training in obstetrics. | Communication training improves patient safety and increases patient satisfaction |

| 11. | Jepkosgei et al. (2022) [42] | Kenya | Understanding intra- and interprofessional team and teamwork processes by exploring facility-based neonatal care in Kenyan hospitals | Openness of communication and a supportive co-existence environment foster effective and timely communication. | Local leadership practices, such as training, coaching, and a positive culture, are essential for enhancing cognitive and behavioral skills, fostering positive team relationships, and effective teamwork. | Professional hierarchies lead to delays in patient care and consequently the persistence of professionals’ silos. Findings suggest that local leadership practices promote shared decision making, coordination of tasks, and building trust. |

| 12. | Manias et al. (2021) [43] | Australia | Interprofessional and Intraprofessional Communication about Older People’s Medications across Transitions of Care | Discharge summaries and accountability transfers to community doctors lacked clarity, and pharmacists were often not updated on changing plans, despite their key role in managing medications during transitions. (lack of clarity, unreliable and incomplete information sharing) | clear processes for disseminating discharge summaries to community doctors, accountability to close the loop with medication management and greater levels of interactions between different health professional disciplines across settings | Medication safety was compromised during care transitions due to unclear discharge information processes and accountability transfer to community doctors. |

| 13. | Mistri et al. (2023) [44] | India | Enhancing patient safety culture in hospitals | Clear, open, and concise communication is necessary to ensure accurate transfer of information between HCPs | Positive organizational culture (Strong and supportive leadership, staff training, and teamwork | Patient safety culture improves health outcomes, encourages incident reporting, builds trust and confidence, and reduces costs. |

| 14. | Mueller et al. (2019) [35] | USA | Principles of Pediatric Patient Safety: Reducing Harm Due to Medical Care (policy statement) | Training of new clinicians and integrating patient safety into ongoing medical education helps the future workforce incorporate all tenets of pediatric patient safety as part of everyday work life. | ||

| 15. | Mueller et al. (2021) [45] | South Africa | Preparing graduates for interprofessional practice | undergraduate training is an integral part of patient care and clinical education | ||

| 16. | Nyoni et al. (2021) [17] | South Africa | Towards Continuing Interprofessional Education: Interaction patterns of health professionals in a resource-limited setting | Working collaboratively | A shared interaction and documentation process that is driven by a common language. | Collaboration of health professionals within the workplace has been linked to improved patient care, patient outcomes, and improved healthcare worker satisfaction |

| 17. | Olino et al. (2019) [46] | Brazil | Effective communication for patient safety: transfer note and Modified Early Warning Score | Using the protocol enhances timely admission to the ICU | Development of a structured vital sign protocol, staff training on utilization of the tool | Increased adherence to MEWS is linked to improved patient safety and reduced neonatal mortality in hospitals |

| 18. | Pittalis et al. (2021) [23] | Malawi | Using Network and Complexity Theories to Understand the Functionality of Referral Systems for Surgical Patients in Resource-Limited Settings: The Case of Malawi | Collaboration between and a shared objective of care are important in determining the referral network’s overall performance | System functionality impacts the quality, efficiency, and safety of patient referral-related care. (Availability of protocols and standards to guide referrals | |

| 19. | Pornrattanakavee et al. (2022) [47] | Thailand | Impact of interprofessional collaborative practice in palliative care on outcomes for advanced cancer inpatients in a resource-limited setting | Working collaboratively | Co-working and communication between specialist palliative care nurses and medical oncologists are considered key factors for effective interprofessional collaboration in resource-limited settings. | Improved quality of life and significantly reduced readmission rate at 7 days after hospital discharge. |

| 20. | Raymond & Harrison (2014) [25] | South Africa | The structured communication tool SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation) improves communication in neonatology | The use of SBAR enhanced the timeliness and promptness of patient care and senior review. Clarity of instruction resulted from using SBAR | Healthcare worker training in interprofessional communication is important for patient safety | Implementing SBAR enhances communication among professionals and positively impacts perceptions of patient care quality and safety. |

| 21. | Rickard et al. (2022) [48] | Gambia | Clinical handover communication at maternity shift changes and women’s safety in Banjul, the Gambia: a mixed-methods study | Many participants complained that “incomplete notes” coupled with “illegible handwriting” could lead to information lapses regarding patient care. | Absence of standardized guidelines, training, poor organizational culture, and individual factors (challenges with transportation) affect multidisciplinary handover communication | Communication failures had resulted in the omission or duplication of treatments, potentially causing patient harm. |

| 22. | Stewart and Snowden (2021) [49] | Georgia | Promoting Communication and Safety Through Clear and Concise Discharge Orders | Recent improvements in assessment support the idea that clear and concise directives enhance communication. | This project indicates that admission nurse satisfaction and reaction to the tool were affected positively by the addition of the DO to the discharge process. | |

| 23. | Tiwary et al. (2021) [6] | Nepal | Poor communication by health care professionals may lead to life-threatening complications: examples from two case reports | Clear communication is essential for the proper treatment of patients, especially in countries with high rates of illiteracy | Effective communication training for healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, is essential. | Poor communication can lead to life-threatening complications in patients. |

| 24. | Toumi et al. (2024) [50] | Tunisia | The SBAR tool for communication and patient safety in gynecology and obstetrics: a Tunisian pilot study | Positive evaluations concerning clarity, relevance of communication, and time spent on the call underscore the potential effectiveness of structured clinical communication. | Education and training of students and health professionals are vital to ensure good quality standardized communication. | Health workers’ awareness of WHO-recommended structured communication tools like SBAR improved communication, staff satisfaction, and patient safety in the Tunisian healthcare setting. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katantha, M.N.; Strametz, R.; Baluwa, M.A.; Mapulanga, P.; Chirwa, E.M. Effective Interprofessional Communication for Patient Safety in Low-Resource Settings: A Concept Analysis. Safety 2025, 11, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030091

Katantha MN, Strametz R, Baluwa MA, Mapulanga P, Chirwa EM. Effective Interprofessional Communication for Patient Safety in Low-Resource Settings: A Concept Analysis. Safety. 2025; 11(3):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030091

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatantha, Mercy Ngalonde, Reinhard Strametz, Masumbuko Albert Baluwa, Patrick Mapulanga, and Ellen Mbweza Chirwa. 2025. "Effective Interprofessional Communication for Patient Safety in Low-Resource Settings: A Concept Analysis" Safety 11, no. 3: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030091

APA StyleKatantha, M. N., Strametz, R., Baluwa, M. A., Mapulanga, P., & Chirwa, E. M. (2025). Effective Interprofessional Communication for Patient Safety in Low-Resource Settings: A Concept Analysis. Safety, 11(3), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030091