Exploring Health, Safety, and Mental Health Practices in the Saudi Construction Sector—Knowledge, Awareness, and Interventions: A Semi-Structured Interview

Abstract

1. Introduction

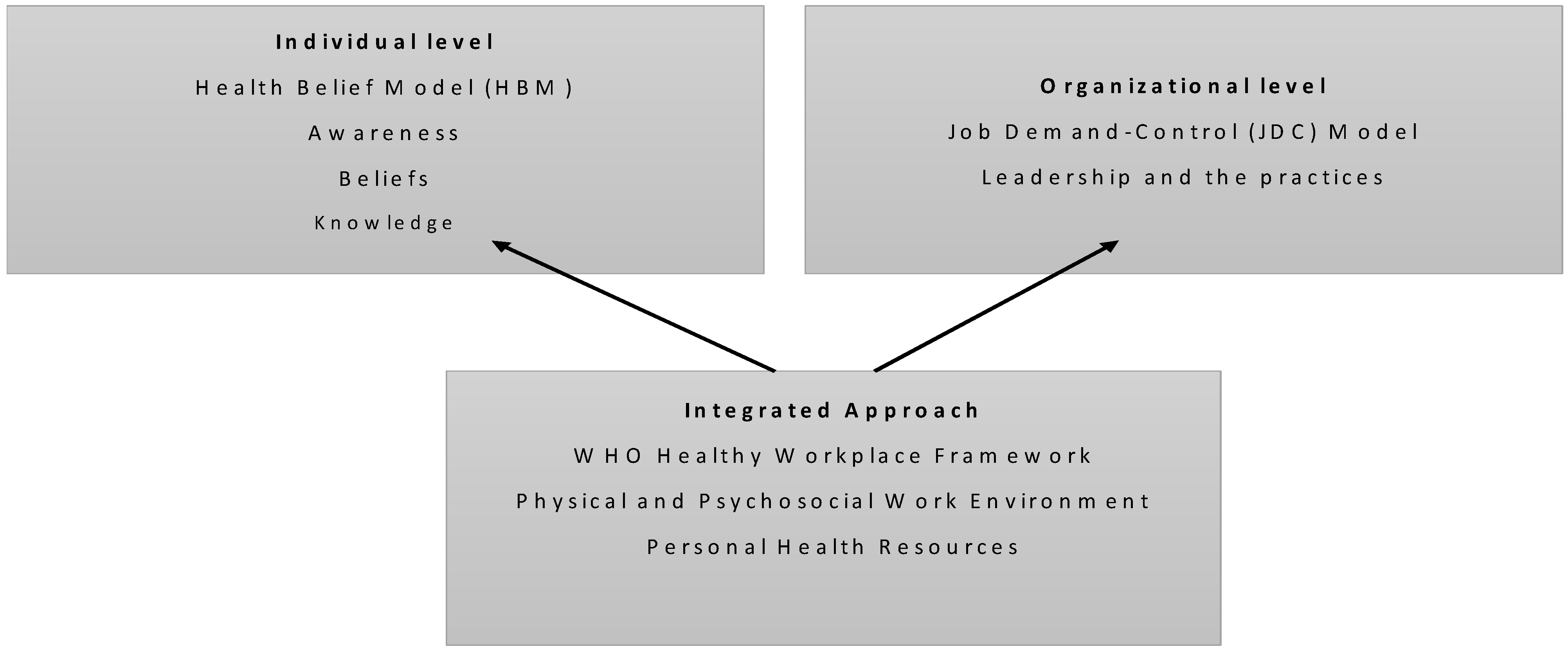

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection

- Background: Focused on demographic and professional data.

- Knowledge: Participants’ understanding of mental health and safety measures to address RQ1. This theme aligns with the Capability component of the COM-B model

- Beliefs: Perceptions of mental health prevalence, potential reasons for these and attitudes toward interventions, addressing RQ1 and RQ3. This theme aligns with Motivation in the COM-B model.

- Awareness: Perceived awareness of mental health and safety and leadership efforts to address RQ1 and RQ4. This theme reflects Capability and Opportunity.

- Practices: Explored existing health and mental health programmes, initiatives, and resources within the organizations. It focused on identifying the protocols and routines in place to address both physical and mental well-being to address RQ2. This theme aligns with Capability and Opportunity.

- Intervention: Examined perceived barriers to implementing effective mental health interventions, such as stigma, lack of resources, or insufficient training. The interview questions also explored suggestions for improving support systems to address RQ3 and RQ4. This theme relates to Opportunity and Motivation.

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Demographics

4.2. Results of Qualitative Interviews

4.2.1. Health, Safety, and Mental Health: Knowledge, Beliefs, and Awareness

- Knowledge:

- Beliefs:

- Awareness:

4.2.2. Existing Health, Safety, and Mental Health Initiative, Programmes, and Resources

4.2.3. Health, Safety, and Mental Health Interventions

5. Discussion

5.1. Stigma and Cultural Barriers to Mental Health Knowledge and Beliefs

5.2. The Role of Companies in Addressing Both Safety and Mental Health

5.3. Need for Awareness Campaigns

5.4. Integrating Mental Health into Safety and Resource Access

5.5. The Need for Proactive and Inclusive Interventions

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

8. Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Codebook

| Name | Participant | Code References (Frequency) | Worker Type |

| Awareness—management ask about mental health | 4 | 6 | National |

| Awareness—awareness high | 20 | 28 | National |

| Awareness—awareness is moderate | 9 | 9 | Migrant |

| Awareness—low awareness on mental health | 23 | 38 | Migrant |

| Awareness—management should provide training and support | 3 | 4 | National |

| Awareness—management take effort to educate on mental health | 5 | 6 | National |

| Belief—people from poor countries more affected | 2 | 3 | National |

| Belief—management raise awareness about mental health and safety | 2 | 3 | National |

| Belief—management recognizes importance of metal health | 2 | 2 | National |

| Belief—management should actively promote mental health | 3 | 3 | National |

| Belief—people have negative view of mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Belief—poor mental health prevalent | 22 | 38 | Migrant |

| Belief—poor training on mental health | 10 | 19 | National |

| Belief—young people most affected by mental health | 7 | 7 | National |

| Belief migrant workers have more mental health due they are away from family | 23 | 17 | Migrant |

| Belief—colleagues work hard to complain about it | 1 | 1 | National |

| Employees should be treated fairly | 2 | 2 | National |

| Familiar with indoor heat stress | 24 | 24 | National |

| Familiar with outdoor heat stress | 24 | 24 | National |

| Health and safety training provided | 23 | 29 | Migrant |

| Heat stress affect negatively | 27 | 28 | Migrant |

| Intervention—training provided | 5 | 5 | National |

| Intervention—awareness needs to be increased | 11 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—intervention provided at all times | 11 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be conducted when convenient | 1 | 1 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be conducted during work hour | 2 | 2 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be given when the need arises | 7 | 7 | National |

| Intervention—management are supportive | 14 | 15 | National |

| Intervention—management not supportive | 2 | 2 | National |

| Intervention—managers need training too | 18 | 19 | Migrant |

| Intervention—toolbox made available | 3 | 3 | National |

| Intervention—training not yet provided | 8 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—workers should be educated about mental health | 7 | 7 | National |

| Management plays key roles in promoting mental health | 17 | 23 | National |

| Management should listen to employees | 5 | 6 | National |

| Management should take active part in promoting safety | 15 | 18 | |

| Medical treatment provided for mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Medication can help cure mental health | 4 | 4 | National |

| Mental health can have negative effect | 12 | 12 | Migrant |

| Mental health not talked about enough | 4 | 4 | National |

| Mental health training not received | 18 | 23 | Migrant |

| Mental health training provided | 2 | 3 | National |

| Mental health training should be provided | 3 | 3 | National |

| Mental health people suffer from life and work | 9 | 34 | Migrant |

| Medication prescribed by a mental health professional | 28 | 31 | Migrant |

| Knowing the problem of mental health is a good solution | 3 | 35 | National |

| Migrants more likely affected by mental health | 12 | 12 | Migrant |

| Not familiar with indoor heat stress | 5 | 5 | National |

| Overworking and stress cause poor mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Poor mental medium but higher in summer | 1 | 1 | National |

| Practice—information gained from experience | 1 | 1 | National |

| Practice—health and safety programs available | 15 | 21 | National |

| Practice—mental health resources and support available | 11 | 21 | National |

| Practice—health and safe programs and resources available | 17 | 28 | National |

| Practice—health and safety program not available | 3 | 3 | National |

| Practice—health and safety program should be made available | 1 | 1 | National |

| Practice—mental health programs not available | 16 | 18 | Migrant |

| Practice—mental health support and resources not available | 16 | 21 | Migrant |

| Therapy can curb mental health issues | 5 | 5 | National |

| Toolbox and protection equipment should be provided | 2 | 2 | National |

| Training on hazard management at workplace | 1 | 1 | National |

| treatment of mental health varies | 1 | 1 | National |

| Well-being programmes from top management to employees | 3 | 3 | National |

Appendix A.2. Themes

| Name | Participant | Code References (Frequency) | |

| Awareness | |||

| Awareness on health and safety | |||

| Awareness—awareness high | 20 | 28 | National |

| Awareness—awareness is moderate | 9 | 9 | Migrant |

| Awareness on mental health | |||

| Awareness—management ask about mental health | 4 | 6 | National |

| Awareness—low awareness on mental health | 23 | 38 | Migrant |

| Awareness—management should provide training and support | 3 | 4 | National |

| Awareness—management take effort to educate on mental health | 5 | 6 | National |

| Beliefs | |||

| Prevalence of mental health | |||

| belief—people from poor counries more affected | 2 | 3 | National |

| Belief—poor mental health prevalent | 22 | 38 | Migrant |

| Belief—young people most affected by mental health | 7 | 7 | National |

| Migrants more like affected by mental health | 12 | 12 | Migrant |

| Views on mental health | |||

| Belief—management raise awareness about mental health and safety | 2 | 3 | National |

| Belief—management recognizes importance of mental health | 2 | 2 | National |

| Belief—management should actively promote mental health | 3 | 3 | National |

| Belief—people have negative view of mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Belief—poor training on mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Belief-colleagues work hard to complain about it | 1 | 1 | National |

| Interventions | |||

| Management support of intervention | |||

| Intervention—management are supportive | 14 | 15 | National |

| Intervention—management not supportive | 2 | 2 | National |

| Need for awareness | |||

| Intervention—awareness needs to be increased | 11 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—workers should be educated about mental health | 7 | 7 | National |

| Need for management training | |||

| Intervention—managers need training too | 18 | 19 | Migrant |

| Provision of intervention | |||

| Intervention—training provided | 5 | 5 | National |

| Intervention—intervention always provided | 11 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be conducted when convenient | 1 | 1 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be conducted during work hour | 2 | 2 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be given when the need arises | 7 | 7 | National |

| Intervention—toolbox made available | 3 | 3 | National |

| Intervention—training not yet provided | 8 | 12 | National |

| Knowledge | |||

| Health and safety | |||

| Health and safety training provided | 24 | 29 | National |

| Training on hazard management at workplace | 1 | 1 | National |

| Unsafe act linked to mental health issues | 25 | 56 | Migrant |

| Health and safety training | 12 | 45 | Migrant |

| Heat stress | |||

| Familiar with outdoor heat stress | 24 | 24 | National |

| Heat stress affect negatively | 27 | 28 | Migrant |

| Not familiar with indoor heat stress | 5 | 5 | |

| Mental health | |||

| Medical treatment provided for mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Medication can help cure mental health | 4 | 4 | National |

| Mental health can have negative effect | 12 | 12 | Migrant |

| Mental health not talked about enough | 4 | 4 | National |

| Mental health training not received | 18 | 23 | Migrant |

| Mental health training provided | 2 | 3 | National |

| Overworking and stress cause poor mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Poor mental medium but higher in summer | 1 | 1 | National |

| Therapy can curb mental health issues | 5 | 5 | National |

| treatment of mental health varies | 1 | 1 | National |

| Role of management | National | ||

| Employees should be treated fairly | 2 | 2 | National |

| Management plays key roles in promoting mental health | 17 | 23 | National |

| Management should listen to employees | 5 | 6 | National |

| Management should take active part in promtoing safety | 15 | 18 | National |

| mental health training should be provided | 3 | 3 | National |

| Toolbox and protection equipment should be provided | 2 | 2 | National |

| Well being programmes from top management to employees | 3 | 3 | National |

| Practices | |||

| Health and safety practices | |||

| Practice—information gained from experience | 1 | 1 | National |

| Practice—health and safety programs available | 15 | 21 | National |

| Practice—health and safe programs and resources available | 17 | 28 | National |

| Practice—health and safety program not available | 3 | 3 | National |

| Practice—health and safety program should be made available | 1 | 1 | National |

| Mental health practices | |||

| Practice—mental health resources and support available | 11 | 21 | National |

| Practice—mental health programs not available | 16 | 18 | Migrant |

| Practice—mental health support and resources not available | 16 | 21 | Migrant |

Appendix A.3. Sub-Themes

| Name | Participant | Code References (Frequency) | |

| Awareness on health and safety | |||

| Awareness—awareness high | 20 | 28 | National |

| Awareness—awareness is moderate | 9 | 9 | Migrant |

| Awareness on mental health | |||

| Awareness—management ask about mental health | 4 | 6 | National |

| Awareness—low awareness on mental health | 23 | 38 | Migrant |

| Awareness—management should provide training and support | 3 | 4 | National |

| Awareness—management take effort to educate on mental health | 5 | 6 | National |

| Health and safety | |||

| Health and safety training provided | 23 | 29 | Migrant |

| Training on hazard management at workplace | 1 | 1 | National |

| Health and safety practices | |||

| Practice _-information gained from experience | 1 | 1 | National |

| Practice -health and safety programs available | 15 | 21 | National |

| Practice—health and safe programs and resources available | 17 | 28 | National |

| Practice—health and safety program not available | 3 | 3 | National |

| Practice—health and safety program should be made available | 1 | 1 | National |

| Heat stress | |||

| Familiar with outdoor heat stress | 24 | 24 | National |

| Heat stress affect negatively | 27 | 28 | Migrant |

| Not familiar with indoor heat stress | 5 | 5 | National |

| Management support of intervention | |||

| Intervention—management are supportive | 14 | 15 | National |

| Intervention—management not supportive | 2 | 2 | National |

| Mental health | |||

| Medical treatment provided for mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Medication can help cure mental health | 4 | 4 | National |

| Mental health can have negative effect | 12 | 12 | Migrant |

| Mental health not talked about enough | 4 | 4 | National |

| Mental health training not received | 18 | 23 | Migrant |

| Mental health training provided | 2 | 3 | National |

| Overworking and stress cause poor mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Poor mental medium but higher in summer | 1 | 1 | National |

| Therapy can curb mental health issues | 5 | 5 | National |

| treatment of mental health varies | 1 | 1 | National |

| Mental health practices | |||

| Practice—mental health resources and support available | 11 | 21 | National |

| Practice—mental health programs not available | 16 | 18 | Migrant |

| Practice—mental health support and resources not available | 16 | 21 | Migrant |

| Need for awareness | |||

| Intervention—awareness needs to be increased | 11 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—workers should be educated about mental health | 7 | 7 | National |

| Need for management training | |||

| Intervention—managers need training too | 18 | 19 | Migrant |

| Prevalence of mental health | 25 | 60 | Migrant |

| belief—people from poor countries more affected | 2 | 3 | National |

| Belief—poor mental health prevalent | 22 | 38 | Migrant |

| Belief—young people most affected by mental health | 7 | 7 | National |

| Migrants more likely affected by mental health | 12 | 12 | Migrant |

| Provision of intervention | |||

| Intervention—training provided | 5 | 5 | National |

| Intervention—intervention always provided | 11 | 12 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be conducted when convenient | 1 | 1 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be conducted during work hour | 2 | 2 | National |

| Intervention—intervention should be given when the need arises | 7 | 7 | National |

| Intervention—toolbox made available | 3 | 3 | National |

| Intervention—training not yet provided | 8 | 12 | National |

| Role of management | |||

| Employees should be treated fairly | 2 | 2 | National |

| Health and safety training | 12 | 45 | Migrant |

| Management plays key roles in promoting mental health | 17 | 23 | National |

| Management should listen to employees | 5 | 6 | National |

| Management should take active part in promoting safety | 15 | 18 | National |

| mental health training should be provided | 3 | 3 | National |

| Toolbox and protection equipment should be provided | 2 | 2 | National |

| Well-being programmes from top management to employees | 3 | 3 | National |

| Views on mental health | |||

| Belief—management raise awareness about mental health and safety | 2 | 3 | National |

| Belief—management recognizes importance of mental health | 2 | 2 | National |

| Belief—management should actively promote mental health | 3 | 3 | National |

| Belief—people have negative view of mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Belief—poor training on mental health | 1 | 1 | National |

| Belief -colleagues work hard to complain about it | 1 | 1 | National |

Appendix B

Interview Questions

- Background: position and experience

- What is your gender?

- How old are you?

- What is your job title?

- What is the highest educational qualification you have related to construction?

- … Certificate/Diploma … Bachelor degree … Postgraduate degree … Others (pls. specify)

- Which construction sector do you work for?

- … Government employer … Private employer

- How long have you dealt with/worked in the Saudi construction industry?

- … Less than 1 year … 1 to 3 years … 3 to 5 years … 5 to 10 years … More than 10 years 10 years of experience

- Size of the company: Small = fewer than 50 employees; Medium = 50–249 employees; Large = more than 250 employees.

- Interview question

Section 1

Knowledge1. Tell me what you know about mental health (prompts: what is it? How does it affect people? What are the treatments for it?)

2. Tell me about any health and safety training or education you have received with your current company (prompt: what about any other construction company you might have worked for?)

3. Have you had any training or education on mental health provided by your current construction company? (Prompt: if yes, tell me about what was covered? How did you review this information? If not, would you like have had some education and training? If yes, how would you have liked to have received this training or education and when?)

4. What role do you think managers and supervisors have in promoting health and safety at work? (How do they do this/How could they do this? What about in addressing any issues—how do they/could they do this?)

5. What role do you think managers and supervisors have in promoting good mental health in the workplace? (How do they do this/How could they do this? What about in addressing any issues—how do they/could they do this?)

6. What do you know about indoor heat stress? And what about outdoor heat stress? How do you think heat stress affects people (a) emotionally, (b) physically?Section 2:

Beliefs1. From your point of view, how prevalent is poor mental health in your company? (Prompt: Why do you think that is the case? What could be causing it (further prompt: what about the working conditions causing stress?) What type of people do you think are more likely to experience poor mental health in the construction industry e.g., migrants, those without family etc.?)

2. What is the general view of others in the construction company toward mental health? (Prompts: Is it taken seriously by (a) colleagues, (b) supervisors (c) senior staff?—can you tell me more about why you think this? For example, has there been anything said about it by senior leaders etc.)

3. Do you know of anyone in your company that has poor mental health? (Prompt: How do you know this? How have they been treated by the company (supervisor, colleagues, and senior leaders)? Any support given to them by the company? What sort of support?).Section 3:

Awareness1. In your company out of 10, where 10 is excellent and 1 is extremely poor, how well do you think the level of awareness on health and safety is among your employees? Can you tell me why you gave that rating?

2. In your company out of 10, where 10 is excellent and 1 is extremely poor, how well do you think the level of awareness of mental health is among your employees? Can you tell me why you gave that rating?

3. What are the efforts made by the senior leaders in your company to raise awareness and educate employees on health, safety? (Prompts: how are they doing this? How often? What else do you think they could be doing? How and how often?)

4. What are the efforts made by the senior leaders in your company to raise awareness and educate employees on mental health? (Prompts: how are they doing this? How often? What else do you think they could be doing? How and how often?)Section 4:

Practices1. Is there any mental health programs or initiatives that are currently in place in your organization?

2. Is there any health and safety programs or initiatives that are currently in place in your organization?

3. Is there any step(s) taken to promote health, safety in the workplace?

4. Is there any step(s) taken to promote mental health well-being in the workplace?

5. Do health and safety resources and support available for employees?

6. Do mental health resources and support available for employees?Section 5:

Intervention1. What are the steps taken to stay updated on the latest developments and best practices in health, safety, and mental health intervention? (Prompt: did you receive any training related to safety issues? Do managers need training?)

2. How should the workplace be made aware of the working conditions that cause poor mental health? (Prompt: Which working conditions could be addressed? What would be the barriers and facilitators?)

3. When and where does the health, safety, and mental health intervention given? (Prompt: Does the participants complete interventions in the workplace, their own time, providing a flexible timeline for completion, assisted scheduling?)

4. Do leadership and management support the intervention? (Prompt: Does leaders disclose their own experience of mental health or use of interventions and endorsing intervention activities to be completed in work time? Does safety and health interventions mandatory or voluntary? Does the intervention sufficiently individualized or specifically relevant to their different workplaces, preferring interventions that were practical and relevant to workers?)

References

- Jazari, M.D.; Jahangiri, M.; Khaleghi, H.; Abbasi, N.; Hassanipour, S.; Shakerian, M.; Kamalinia, M. Prevalence of self-reported work-related illness and injuries among building construction workers, Shiraz, Iran. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, S.; Li, H.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Wong, A.Y.L. Associations between physical or psychosocial risk factors and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in construction workers based on literature in the last 20 years: A systematic review. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 83, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaskati, D.; Kermanshachi, S.; Pamidimukkala, A. A review on the mental health stressors of construction workers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transportation and Development, Nairobi, Kenya, 9–11 December 2024; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H. Occupational health and safety in the construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takim, R.; Abu Talib, I.F.; Nawawi, A.H. Quality of Life: Psychosocial environment factors in the event of disasters to private construction firms. Asian J. Qual. Life 2018, 3, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Nwaogu, J.M.; Naslund, J.A. Mental ill-health risk factors in the construction industry: Systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Dimoff, J.; Mohr, C.D.; Allen, S.J. A framework for protecting and promoting employee mental health through supervisor supportive behaviors. Occup. Health Sci. 2024, 8, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.C. Measures to Boost Mental Health in the Construction Industry: Lessons from the Nigerian Workplace. In Health and Safety, Workforce, and Education—Selected Papers from Construction Research Congress 2022, Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress, Arlington, VA, USA, 9–12 March 2022; Jazizadeh, F., Shealy, T., Garvin, M.J., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; Volume 4-d, pp. 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.J. Employee well-being outcomes from individual-level mental health interventions: Cross-sectional evidence from the United Kingdom. Ind. Relat. J. 2024, 55, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hon, C.K.H.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B. The relationship between psychosocial hazards and mental health in the construction industry: A meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehorne-Smith, P.; Lalwani, K.; Mitchell, G.; Martin, R.; Milbourn, B.; Abel, W.; Burns, S. Working towards a paradigm shift in mental health: Stakeholder perspectives on improving healthcare access for people with serious mental illnesses and chronic physical illnesses in Jamaica. Discov. Health Syst. 2024, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyllon, M.; Vallas, S.P.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Garverich, S.; Weinstein, D.; Owens, K.; Lincoln, A.K. Mental health stigma and wellbeing among commercial construction workers: A mixed methods study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, e423–e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, S. Mental health prevention and promotion—A narrative review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 898009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Roemer, E.C.; Kent, K.B.; Ballard, D.W.; Goetzel, R.Z. Organizational best practices supporting mental health in the workplace. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e925–e931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrlant, D.; Darandary, A. Economic Diversification Under Saudi Vision; King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havrlant, D.; Soytas, M.A. Saudi Vision 2030 Dynamic Input–Output Table: Combining Macroeconomic Forecasts with the RAS Method; King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Boadu, E.F. Domains of Psychosocial Risk Factors Affecting Young Construction Workers: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, S.; Rustage, K.; Nellums, L.B.; McAlpine, A.; Pocock, N.; Devakumar, D.; Aldridge, R.W.; Abubakar, I.; Kristensen, K.L.; Himmels, J.W.; et al. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e872–e882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulseren, D.B.; Lyubykh, Z. Leadership interventions to foster mental health and work well-being. In The Routledge Companion to Mental Health at Work; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Lorente, L.; Vignoli, M.; Nielsen, K.; Peiró, J.M. Challenges influencing the safety of migrant workers in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Italy, Spain, and the UK. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, A. Improving occupational health and workplace safety in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 3, 261–267. Available online: https://www.isdsnet.com/ijds (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kortum, E. The WHO healthy workplace model. In Contemporary Occupational Health Psychology; Leka, S., Sinclair, R.R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Occupational Health: Health Workers. November 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/occupational-health--health-workers (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Jamshed, S. Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2014, 5, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunwoodie, K.; Macaulay, L.; Newman, A. Qualitative interviewing in the field of work and organisational psychology: Benefits, challenges and guidelines for researchers and reviewers. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 863–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochmiller, C.R. Conducting thematic analysis with qualitative data. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 2029–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damayanthi, S. Thematic analysis of interview data in the context of management controls research. In Thematic Analysis of Interview Data in the Context of Management Controls Research; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, J.B. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| P | Age | Job Title | Highest Academic Qualification | Experience (Years) | Sector Type | Sector Size | Nationality | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 38 | Senior Safety Specialist | Bachelor | 15 | Private | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P2 | 40 | Senior Executive Safety | Postgraduate | 19 | Public | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P3 | 36 | Health and Safety Inspector | Postgraduate | 13 | Private | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P4 | 44 | Chief Safety Officer | Postgraduate | 17 | Private | Large | Saudi | Snowball |

| P5 | 33 | Health and Safety Adviser | Bachelor | 10 | Private | Large | Saudi | Snowball |

| P6 | 37 | Safety Officer | Bachelor | 15 | Private | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P7 | 39 | Project Manager | Postgraduate | 18 | Public | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P8 | 42 | Senior Construction Manager | Bachelor | 14 | Private | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P9 | 40 | Construction Worker | Diploma | 17 | Private | Medium | migrant | Snowball |

| P10 | 48 | Director of Occupational Health and Safety | Postgraduate | 19 | Public | Large | Saudi | Direct |

| P11 | 46 | Senior Construction Manager | Postgraduate | 19 | Private | Medium | Saudi | Direct |

| P12 | 31 | Civil Construction Engineer | Postgraduate | 10 | Public | Small | migrant | Snowball |

| P13 | 32 | Safety Specialist | Bachelor | 6 | Public | Small | Saudi | Snowball |

| P14 | 33 | Safety Manager | Bachelor | 10 | Private | Small | Saudi | Direct |

| P15 | 37 | Construction Manager | Bachelor | 12 | Private | Large | Saudi | Snowball |

| P16 | 34 | Construction Technician | Diploma | 13 | Private | Medium | migrant | Direct |

| P17 | 36 | Safety Supervisor | Diploma | 12 | Public | Small | Saudi | Snowball |

| P18 | 42 | Civil Construction Engineer | Bachelor | 10 | Public | Medium | migrant | Snowball |

| P19 | 45 | Electronic Technician | Bachelor | 6 | Public | Small | migrant | Snowball |

| P20 | 32 | Health and Safety Specialist | Bachelor | 12 | Public | Medium | Saudi | Direct |

| P21 | 39 | Environmental Safety Specialist | Bachelor | 12 | Public | Small | Saudi | Direct |

| P22 | 34 | Technician | Diploma | 9 | Private | Small | migrant | Direct |

| P23 | 36 | Safety Manager | Bachelor | 12 | Private | Medium | migrant | |

| P24 | 34 | Safety Engineer | Bachelor | 13 | Private | Small | Saudi | Direct |

| P25 | 45 | Construction Technician | Diploma | 20 | Public | Small | migrant | Direct |

| P26 | 49 | Engineer | Bachelor | 21 | Public | Medium | Saudi | Direct |

| P27 | 26 | Civil Engineer | Bachelor | 4 | Private | Medium | migrant | Snowball |

| P28 | 42 | Technician | Bachelor | 5 | Public | Medium | migrant | Direct |

| P29 | 38 | Civil Engineer | Bachelor | 5 | Public | Medium | Saudi | Snowball |

| P30 | 44 | Construction Technician | Diploma | 10 | Public | Small | Saudi | Direct |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alruwaili, M.M.; Munir, F.; Carrillo, P.; Soetanto, R. Exploring Health, Safety, and Mental Health Practices in the Saudi Construction Sector—Knowledge, Awareness, and Interventions: A Semi-Structured Interview. Safety 2025, 11, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030090

Alruwaili MM, Munir F, Carrillo P, Soetanto R. Exploring Health, Safety, and Mental Health Practices in the Saudi Construction Sector—Knowledge, Awareness, and Interventions: A Semi-Structured Interview. Safety. 2025; 11(3):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030090

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlruwaili, Musaad M., Fehmidah Munir, Patricia Carrillo, and Robby Soetanto. 2025. "Exploring Health, Safety, and Mental Health Practices in the Saudi Construction Sector—Knowledge, Awareness, and Interventions: A Semi-Structured Interview" Safety 11, no. 3: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030090

APA StyleAlruwaili, M. M., Munir, F., Carrillo, P., & Soetanto, R. (2025). Exploring Health, Safety, and Mental Health Practices in the Saudi Construction Sector—Knowledge, Awareness, and Interventions: A Semi-Structured Interview. Safety, 11(3), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030090