1. Introduction

Air traffic control is considered one of the most demanding and safety-critical occupations in modern transport systems. The role of an Air Traffic Controller (ATCO) is ranked first in the aviation industry in terms of mental workload [

1]. The job itself entails a complex set of tasks requiring high cognitive skills, adaptability according to differing circumstances, multitasking under time pressure, and continuous communication across different operational interfaces [

2,

3,

4]. In the context of air traffic control, “safety” extends beyond general Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) definitions, which typically emphasize the prevention of physical harm and workplace hazards. In air traffic control, safety is operationally understood as the uninterrupted and precise management of aircraft separation and the anticipation of system-level risks in real-time, under high cognitive demand and dynamic environments. This distinguishes it from general OHS by embedding safety directly within the functional performance of the controller [

3]. Contrary to many traditionally studied sectors where safety and operational efficiency may be in conflict, in air traffic control, safety is inherently intertwined with operational performance. This unique integration makes safety a critical component of job performance [

5]. Moreover, the OHS conditions of ATCOs are becoming increasingly acknowledged as strategic enablers of quality and resilience in air navigation services [

6].

Safety culture, while generally understood in OHS as a shared mindset and set of practices that promote workplace safety, is applied more explicitly and operationally in the ATC environment. In particular, it is not only a value system but also a component of the organizational framework embedded in standard operating procedures, controller behaviors, and operational control mechanisms. According to Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO), safety culture reflects individual, group, and organizational attitudes, norms, and behaviors related to the safe provision of air navigation services [

7]. Translating this into the OHS context of ATCOs means fostering a work environment where psychological safety, open communication, and non-punitive reporting (as promoted by the principles of Just Culture) are encouraged, and where human limitations such as fatigue and mental strain are actively managed [

7]. A mature safety culture in ATC is therefore not limited to procedural compliance but extends to the organizational systems that support controllers’ health, well-being, and resilience under pressure. It is manifested through procedural compliance, vigilant monitoring of airspace dynamics, adherence to standardized phraseology, and real-time adaptation to disruptions. Such features are fundamental to sustaining the safety of air operations [

3].

In recent years, research and industry attention have focused on how workplace conditions, ranging from safety culture, fatigue management, and social support, can impact ATCO mental health and performance [

2,

3,

5,

8]. Findings can be synthesized across key dimensions that emerge as critical to the occupational health, safety, and performance of ATCOs. Perceived workplace safety is foundational, influencing not only compliance with industry standards but also employees’ psychological well-being [

5,

6]. Occupational stress, mental workload, and strain are dominant themes in the literature, evidently because they are associated with the high cognitive demands required by ATC tasks and with the constant vigilance accompanying ATC operations [

2,

8,

9,

10]. Training, either technical or non-technical (stress/fatigue coping), has been recognized as a significant factor in shaping job performance but also in buffering against strain and dissatisfaction [

11,

12]. Supervisor behavior and leadership qualities have also emerged as a “visible” expression of organizational safety culture, with participatory leadership and peer support being identified as protective factors for mental health and job satisfaction [

5,

13,

14]. Improved working conditions, including role clarity, a level of decision latitude, and workload management practices, complete the picture of the multi-layered influences that shape well-being and safety in the ATCO environment [

2,

9,

12].

In this regard, it is important to note that certain concepts, such as role clarity, may carry a more precise meaning within the ATC context than in the general OHS literature. ATCO roles are dictated by standardized procedures, regulatory guidelines, and strict operational responsibilities. Therefore, any reference to role clarity in this paper reflects its use as a formal, highly structured construct that encompasses delineated task demands, expected actions, and communication protocols.

According to EUROCONTROL’s latest forecast [

15], air traffic in Europe is expected to continue growing, with an average annual increase of 2.5% between 2024 and 2030, eventually surpassing the pre-pandemic levels prior to 2019. This expected growth reflects the rising operational demand placed on the job of ATCOs. The mental workload, if excessive, would be a significant risk factor for increased cognitive strain and an increased risk of human error.

This study aims to explore the impact of occupational health and safety (OHS) systems on the well-being and performance of air traffic controllers (ATCOs) of the Hellenic Air Navigation Services Provider. Specifically, it investigates how perceptions of structured OHS frameworks relate to job satisfaction, perceived safety, stress, and mental strain. The study also examines how workplace factors such as training, autonomy, and role clarity interact with employee well-being.

Based on this aim, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ1: How does the reported presence of an OHS system influence ATCOs’ perceptions of workplace safety?

RQ2: Is the presence of an OHS system associated with differences in ATCOs’ stress levels and job satisfaction?

RQ3: How are job resources, specifically training, role clarity, and autonomy, associated with psychological outcomes such as stress, exhaustion, and satisfaction?

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

This section outlines the theoretical underpinnings and key concepts relevant to the study. It includes the structure of the Air Navigation Services (ANS), international Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) standards, mental workload in ATCOs, and the role of leadership and safety culture in high-reliability aviation environments.

2.1. Air Navigation Services (ANS) and Occupational Health and Safety Standards

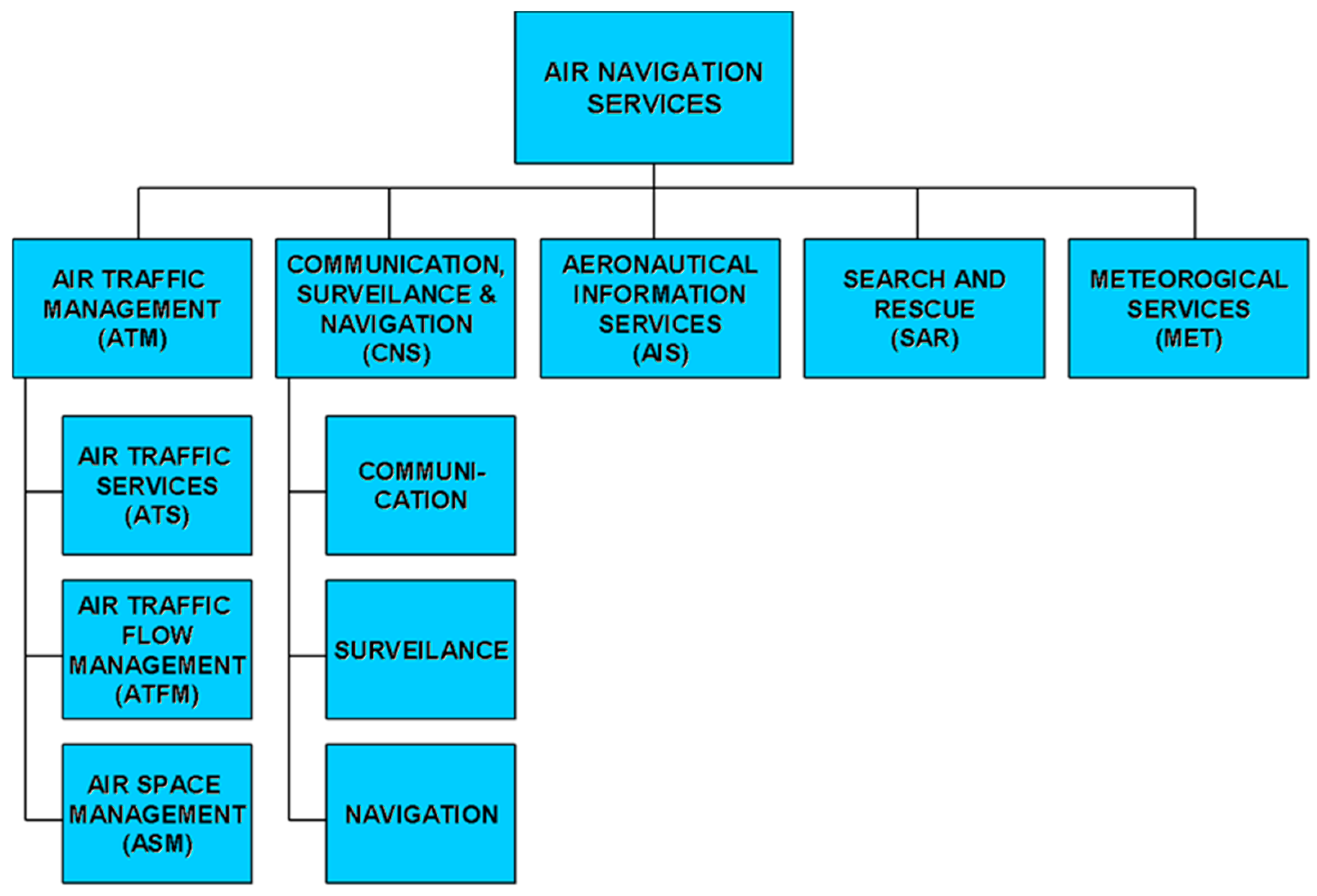

ANS is the term applied to the bundle of services provided to aircraft to enable safe and efficient flights from one destination to another. According to the ICAO (Doc 9734) [

16] and Eurocontrol (ATM Lexicon) [

17], Air Navigation Services (ANSs) are “services provided to air traffic during all phases of operations including air traffic management, communication, navigation and surveillance, meteorological services for air navigation, search and rescue and aeronautical information services”. ANS comprises ground-based radio navigation aids and precision approach and landing systems. The implementation of Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) will add satellite constellations, providing the standard signal positioning service and the associated augmentation systems required, i.e., satellite-based (wide area) and ground-based (local area) augmentations [

16,

17].

Air Traffic Management (ATM), which consists of:

Air Traffic Services (ATSs);

Air Traffic Flow Management (ATFM);

Air Space Management (ASM).

Communication, Navigation, and Surveillance and Air Navigation Systems (CNSs).

Aeronautical Information Services (AISs);

Search and Rescue (SAR);

Meteorological Services (METs).

Air Traffic Service is a service provided by licensed ATCOs for the purpose of preventing midair collisions and collisions in the maneuvering area between aircraft and obstructions, while also expediting and maintaining an orderly flow of air traffic. According to ICAO Doc 9885 [

18], Air Navigation Services are provided by Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs), which may be public or private legal entities. ANSPs manage air traffic on behalf of a company, region, or country. Depending on the specific mandate, an ANSP provides one or more of the above services to airspace users [

18].

OHS standards—encompassing laws, risk governance policies, and day-to-day practices—are designed to protect the health, safety, and overall well-being of employees in the workplace. Their core function is to anticipate, assess, and control work-related hazards so as to prevent workplace illnesses and injuries, fostering a secure working environment within organizations. Over time, national and international organizations have established comprehensive frameworks, enabling companies to implement effective safety management systems, meet legal requirements, and embed safety values into everyday operations.

ISO 45001:2018 is a leading international management system standard for OHSs, requiring organizations to establish a Plan–Do–Check–Act system that emphasizes proactive risk management, worker engagement and participation, and ongoing improvement as critical factors to achieve a safer work environment [

19]. The standard adopts a risk-based orientation, mandating processes to identify hazards, analyze risk determinants, and implement controls to eliminate danger factors or reduce risks to acceptable levels. It also embeds ongoing worker participation in governance and day-to-day practices, ensuring that employees’ concerns and requirements are incorporated into objectives, policies, and procedures across the organization.

Complementing this, ISO 6385:2016—ergonomic principles in the design of work systems—provides foundational guidelines for designing work systems with an integrated focus on human, technical, and social requirements [

20]. Unlike ISO 45001, which focuses on safety management systems, ISO 6385 emphasizes the ergonomics of work system design across the full lifecycle of operations. It is particularly relevant in complex, high-risk environments such as ATC, where the interaction between humans and technical systems must be optimized to ensure performance, well-being, and safety.

In addition, ISO 10075-1:2017—ergonomic principles related to mental workload—offers a conceptual framework to support the design of working conditions that account for psychological load [

21]. In the context of ATC, where sustained attention and decision-making are central, applying ISO 10075-1 helps clarify the distinction between mentally sustainable workloads and those likely to cause fatigue or burnout, thereby supporting safer and healthier work system design.

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) plays a central regulatory role in establishing and enforcing workplace safety standards. OSHA issues legally binding directives that address a broad range of industry-specific hazards. Examples of these standards encompass protocols, such as, for example, requirements for communicating hazards, implementing fall-prevention measures, guarding machinery, and safely handling and disposing of hazardous chemicals [

22]. Adhering to such regulations not only minimizes the risk of occupational injuries and illnesses but also reinforces organizational accountability and ensures alignment with legal obligations.

Beyond ISO 45001 and OSHA, the International Labour Organization (ILO) provides foundational instruments that address critical dimensions of workplace safety and health. Notably, ILO Convention No. 155 advocates for the development of coherent national policies on occupational safety and health, while Convention No. 187 advances a promotional framework aimed at cultivating a preventive safety culture [

4,

23]. Together, such conventions reflect the global consensus on the significance of OHS and serve as a model for harmonization across nations. Alongside international standards, countries enact domestic legislation tailored to their unique legal, economic, and cultural contexts. For instance, within the European Union, Framework Directive 89/391/EEC requires employers to safeguard workers’ security and welfare across all aspects of employment. This directive promotes a proactive approach to workplace safety, emphasizing hazard identification and risk assessment, worker information and training, and the establishment of a structured operation of safety and health committees [

24].

To address industry-specific risks, tailored standards have been established across various sectors with distinctive hazard profiles. In the UK, for example, the 2015 Construction (Design and Management) Regulations clearly outline the duties and responsibilities of individuals involved in construction, spanning designers, contractors, and workers across the project lifecycle. Similarly, the mining industry adheres to specialized safety frameworks, including the Health and Safety Principles set forth by the International Council for Mining and Metals (ICMM), which are intended to prevent fatalities and injuries in high-risk settings [

25]. However, air traffic control presents a different kind of risk profile. As part of High-Reliability Organizations, Air traffic control operations are characterized not by high physical risk to workers, but by the potential for critical system-level failures if human performance is compromised. In this context, managing psychosocial risks, such as stress, cognitive overload, and fatigue, becomes paramount. ISO 45003:2021—psychological health and safety at work—provides essential guidance for addressing such risks, complementing standards like ISO 45001 by focusing specifically on mental well-being in complex, safety-critical environments [

26]. While adherence to OHS standards is a legal requirement, its ethical significance is equally important. Moral responsibility often extends beyond mere legal compliance, emphasizing a company’s role in safeguarding the lives and well-being of its workforce. Thus, conformity should not be treated as a strategy to avoid penalties or fulfill regulatory obligations; it should reflect a deeper commitment to upholding employees’ right to a safe and healthy workplace [

24,

27]. Fostering ethical leadership and encouraging participatory management practices are essential for cultivating a safety culture that places employee welfare above short-term financial gain [

28].

The moral stakes are especially heightened in high-risk sectors, where safety failures carry profound moral consequences [

25,

29,

30]. Incidents underscore the imperative for robust safety measures, adequate training, and clear accountability across all levels of management [

27,

31]. Despite the existence of general OHS standards, organizations may struggle to implement them effectively. Among the main challenges are limited financial and human resources, weak leadership commitment, and resistance to change. In developing economies, these issues are exacerbated by poor compliance and limited awareness of OHS requirements [

32]. To address such challenges, companies must embed ethical principles into their safety management systems, aligning incentives, clarifying roles, and establishing learning and accountability processes.

2.2. The Link Between OHS and Well-Being

OHS plays a pivotal role in shaping workers’ well-being and productivity. A robust OHS framework not only safeguards employees from hazards in the workplace but also significantly contributes to reducing absenteeism and enhancing overall welfare [

33,

34,

35]. A substantial body of evidence demonstrates the intricate link between absenteeism, OHS, and welfare; organizations that cultivate a strong safety culture report better overall health, higher job satisfaction, and lower rates of work-related absenteeism [

36]. Employee absenteeism typically arises from illness, occupational injuries, or personal matters, and can impose a significant financial and operational burden on an organization [

37]. Empirical evidence has linked poor working conditions—such as inadequate ergonomics, exposure to harmful substances, excessive noise, and psychological stress—and workplace incidents with elevated levels of absenteeism [

38]. An effective OHS system, encompassing systematic hazard assessment, targeted training, and health monitoring, can effectively mitigate risks and reduce absenteeism. Evidence has shown that organizations with well-developed OHS practices typically exhibit lower levels of absenteeism than those with weaker safety interventions [

39].

Employee well-being is a multidimensional construct encompassing physical and mental health, as well as job satisfaction. Effective OHS systems enhance well-being by reducing workplace stress and burnout and by fostering a sense of safety and trust among employees [

40]. A strong safety culture signals that workers are valued and protected, boosting motivation and reinforcing their drive to perform [

41,

42]. The Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) Model [

43] clarifies these dynamics: increased job demands (like a heavy workload or hazardous conditions) can lead to strain and burnout. Nevertheless, adequate job resources (e.g., supportive policies, ergonomic design, training, participation mechanisms) act as a buffer against stress and promote resilience and sustained well-being. Organizations that prioritize OHS, therefore, cultivate environments characterized by lower strain, greater vigor, and higher job satisfaction.

Beyond its influence on absenteeism and well-being, a robust OHS system is integral to organizational performance. Workers who feel safer and supported tend to be more productive, engaged, and committed to achieving workplace goals. Empirical research associates investment in OHS with improved retention, higher morale, and greater operational efficiency [

44]. Strong safety environments also correlate with fewer compensation claims, lower medical expenditures, and reduced turnover, thus yielding significant cost savings for firms [

45].

2.3. Occupational Stress and Mental Strain Among ATCOs

The role of the ATCO is frequently listed among the most stressful occupations, and research in the past decade continues to explore the sources and impacts of this stress. The reasons behind high stress lie both in the nature of the work and in organizational factors. On the operational side, common stressors include traffic density, time pressure, workload dynamics, and complexity of tasks [

3,

9,

26]. On the organizational side, stressors often relate to workplace conditions like shift schedules, rostering practices, role ambiguity, poor support structures, organizational climate, and unfavorable working conditions [

3,

8,

10,

14]. Job insecurity is another stressor that has gained attention. A recent study has uncovered that, although ATCOs work under intense stress, they are unlikely to seek medical or psychological treatment for issues, possibly fearing losing their qualification [

46,

47].

A major component of mental strain is exhaustion—a state of physical and mental fatigue that can progress to burnout if chronic. A 2021 cross-sectional study comparing ATCOs to other high-stress professionals found notable levels of burnout syndrome among controllers [

48]. The EASA Study [

2] showed that prolonged duty periods without breaks and consecutive working days are factors associated with increased fatigue risk, and it discussed the promise of Fatigue Risk Management Systems (FRMS) in reducing or preventing fatigue and improving safety outcomes.

2.4. The Role of Leadership and the Organizational Safety Culture

Embedding OHS systems within a broader quality management framework enhances both employee satisfaction and operational efficiency, particularly when leadership actively promotes and reinforces the system’s principles and goals, when procedures are well communicated and understood, and the system is institutionalized into the organizational culture [

6]. Across high-risk sectors, including aviation, a leader’s visible engagement with safety can increase motivation and trust, further supporting safety outcomes and well-being [

49]. Recent studies revealed that a supportive and safety-oriented leadership influences safety citizenship behavior [

5,

50]. Employees’ psychological capital can also strengthen their perception of the safety climate, reinforcing the idea that both individual and organizational-level resources play critical roles in fostering safety behaviors [

51].

A 2024 study of over 300 ATCOs demonstrated that, when controllers perceive high levels of job support from colleagues and leaders, the harmful impact of mental workload on their job performance is significantly reduced [

8].

Job satisfaction among air traffic controllers is a crucial outcome and a mediator between stressors and other consequences (like turnover). Multiple studies in recent years have sought to identify what factors most influence ATCOs’ satisfaction at work. A literature analysis in 2022 distilled five predominant factors driving ATCO job satisfaction:

Ambiguity of job functions—unclear roles or procedures can frustrate controllers;

Overwhelming workload—consistently high traffic and task load reduces satisfaction;

Complex task demands and uncertainty—the inherent complexity and unpredictability of traffic can be a source of stress that lowers satisfaction;

Job fatigue—persistent tiredness from schedules or workload drains morale;

Work–family conflict—irregular hours and relocation needs disrupt personal life balance.

The interaction among these variables is evident in the research. For example, a study of ATCOs in Taiwan [

52] found that job satisfaction mediates the relationship between stress and turnover intention, meaning high stress leads to lower satisfaction, which in turn drives people to consider leaving. Conversely, improving satisfaction can buffer the negative effects of stress on retention.

One important driver of job satisfaction is the degree of job autonomy and control a controller feels they have. ATC is highly procedural, and controllers operate within tight regulatory constraints for safety reasons. This often means limited autonomy—the work pace is dictated by air traffic flow, and breaks or shifts are scheduled by management or union rules rather than at the controller’s discretion. In fact, the literature review above identified that scheduling “regular breaks between shifts” was an effective method to improve ATCO jobs [

14]. When controllers know they will have a chance to rest and reset, their ability to handle stress and their overall job contentment improve.

3. Methodological Framework

To address the study’s research question, a cross-sectional quantitative survey was conducted. A custom-made questionnaire was used, which consisted of five parts and 106 multiple-choice and closed-type questions (5-point Likert-type scale) on personal data, occupational status, workplace conditions, and the OHS system. The survey was appropriate for the diverse group of controllers distributed across different units and with a broad background and experience level.

As presented in

Table 1, the questionnaire is structured into six main sections, each addressing a specific aspect of the respondent’s professional and personal background, workplace conditions, and perceptions. Section A: Personal Information gathers demographic data such as gender, age, marital status, number of children, educational level, and foreign language proficiency. Section B: Employment Status focuses on professional details, including year of hire, operational role, type of organizational unit, position held, and work schedule.

Section C: Working Conditions is the most extensive section, exploring factors such as leave balance, staffing, workload, suitability of training, autonomy, clarity of objectives, workplace fairness, support from colleagues and supervisors, training adequacy, and overall work environment. Section D: Occupational Well-being and Mental Strain addresses emotional and psychological states like stress, job insecurity, exhaustion, and mental strain indicators. Section E: Occupational Health and Safety System assesses the presence, implementation, and effectiveness of health and safety policies, infrastructure, and training in the workplace. Finally, Section F concludes with a single item evaluating the respondent’s overall job satisfaction. Across all sections, response formats include multiple-choice options, Likert scales, checklists, and short text or numeric entries. This comprehensive structure enables a multifaceted understanding of employees’ experiences and conditions in the workplace.

The population of the research project was all Air Traffic Controllers (ATCOs) of the Hellenic Air Navigation Service Provider (HANSP), whose number at the period of the research was 580, and had operational, administrative, and managerial positions at five (5) different directorates of HANSP. The questionnaire was sent to the e-mails of all 580 ATCOs through the use of the platform of Google Forms. The questionnaire and the software platform were properly structured to ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of the responders. The questionnaire was accompanied by a letter to the participant explaining the research project objective, the context of the project, the confidentiality of the answers and anonymity assurance, the period of the research, and the use and publicity/dissemination of the results. It is noted that the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave their informed consent before participation.

Essentially, the questionnaire was sent to all ATCOs of the General Directorate of Air Navigation Services (GDANS) during the reference period of the study, including those working in operational environments (whether radar or procedural airport and/or approach control), as well as in administrative/support units related to air traffic services. The population of the study consisted of the 580 Air Traffic Controllers (ATCOs) belonging to the official ATCO units and specifically the departments of the seven (7) Directorates and their respective Divisions of the GDANS of the Hellenic Civil Aviation Authority (HCAA), where operational and/or administrative ATCOs were employed. Upon completion of the study period, 307 questionnaire responses were collected, corresponding to 52.93% of the total number of questionnaires distributed.

This response rate falls within the range commonly reported in ATCO-related studies. For example, Schopf et al. [

5] reported 17.1%, Makara-Studzińska et al. [

44] reported 18–56%, EASA [

2] noted 33% from national authorities and 78% from service providers, and Bergheim et al. [

47] reported 65%. Due to the anonymous nature of data collection, a formal non-response analysis was not feasible. Therefore, the possibility of self-selection bias cannot be excluded—for instance, individuals experiencing higher levels of stress or dissatisfaction with their work environment may have chosen not to participate. Nonetheless, the professional profile of the respondents strengthens the relevance of the sample to the study’s objectives. Among the 307 participants, the vast majority held operational ATCO roles, worked in radar-based units, and were on a 24 h rotating shift schedule—a profile described in detail in the Results section. These characteristics align with the subset of the ATCO population most exposed to psychosocial and occupational health and safety risks.

Instrument Reliability and Validity Testing

A pilot survey was carried out with 18 Air Traffic Controllers (ATCOs) carrying out various operational and administrative activities. During the initial testing, the main target was to validate the clarity, understanding, and relevance of the questions, as well as the total response burden. According to the data, several changes were made to improve the wording of the items, as well as ensure logical consistency, thus allowing for better interpretability of the responses for a diverse set of respondents. Additionally, apart from the information gained through the piloting exercise, the tool was tested for content validity through consultations with three experts, two with expertise in occupational health and safety, and the other with expertise in the management of transport infrastructure, who reviewed the instrument to validate the relevance, comprehensiveness, and appropriateness of the instrument for the constructs measured.

Composite variables were created by averaging conceptually related questionnaire items, each measured on a Likert scale. The training construct was composed of three items assessing the adequacy of training in technical skills, occupational health and safety (OHS), and quality/safety of services (Cronbach’s α = 0.65). The clarity of role and objectives construct was derived from two items evaluating understanding of team goals and personal contribution (Cronbach’s α = 0.71). The work autonomy index was calculated by averaging two items measuring control over work pace and timing of breaks (Cronbach’s α = 0.60). Despite Cronbach’s alpha values for two-item scales tending to be lower due to their limited length, the observed reliability coefficients indicate acceptable internal consistency for exploratory analysis. The conceptual coherence of each combination further supports the use of these composite measures.

To assess the internal consistency of the “Working Conditions” part of the questionnaire, a Cronbach’s alpha reliability analysis was conducted on all 5-point Likert scales ranging from “Not at all” to “Very much.” The analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.84, indicating good internal consistency among the items. This suggests that the selected items reliably measure the underlying construct of perceived working conditions within the organization. Second, a Perceived Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) scale was formed using four items from Section E. These items assessed the perceived sufficiency of health and safety training, the general sense of safety in the workplace, the implementation of OHS measures, and compliance with health and safety standards. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82, demonstrating high internal consistency and suggesting that these items reliably capture employee perceptions of occupational health and safety practices within their organizational unit.

Additionally, three items from Section D were examined as a potential short scale that assessed psychological strain at work. These items addressed emotional exhaustion, work-related stress, and job insecurity. While theoretically related, the internal consistency was relatively low (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.54), indicating limited internal coherence among the items. This result suggests that the three items may be tapping into related but distinct constructs of occupational well-being. In particular, job insecurity may represent a structurally different domain of psychological risk compared to emotional fatigue and stress. Given this, the items were analyzed individually rather than on a composite scale. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the distinct dimensions of employee psychological experiences.

In order to improve the exploration of construct validity, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal axis factoring augmented by a Varimax rotation, as a feature of the four-item OHS implementation construct. The appropriateness of the sample was ascertained through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure, which returned 0.79, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (p < 0.001) and hence confirmed the dataset appropriateness for factor analysis. From the analysis, a single factor emerged, with an eigenvalue of over one, indicating 58.2% of total variance, which explained the data. Each of the four items had strong significant loadings to the factor, with values over 0.65, thus supporting the unidimensionality of the OHS construct. As a result of the inadequacy of the number of items possessed by other constructs, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was not conducted. However, inter-item correlations and corrected item–total correlations were investigated and found to stay within acceptable ranges, thus further supporting the internal consistency of the constructs used.

Considering the set as a whole, these results provide empirical proof that supports the reliability and preliminary validity of the measurement tool. The use of an inclusive strategy consisting of expert judgment, a pilot study, tests of internal consistency, and factor analysis fortifies the case for the survey as a methodologically advanced tool for the assessment of occupational health, safety systems, and psychosocial endpoints relevant to air traffic control. Each measure reinforces the accuracy of the results, as well as the general conclusion reached during the current study.

4. Key Results

This section presents the primary findings of the study, organized around the three research questions presented in

Section 1. Using both inferential and correlational analyses, we address: (RQ1) the relationship between OHS system presence and perceived workplace safety; (RQ2) how OHS system presence relates to stress and job satisfaction; and (RQ3) how job resources such as training, autonomy, and role clarity are associated with key psychological and organizational outcomes. Collectively, these findings highlight the impact of workplace structures and support mechanisms on the psychological and operational experiences of ATCOs, underscoring the significance of formal health and safety frameworks in high-stakes aviation environments.

Table 2 and

Table 3 provide a detailed overview of the demographic and professional characteristics of the 307 participants in the study. As shown in

Table 2, the sample consisted of slightly more males (55.4%) than females (44.6%). Most participants were between 36 and 55 years old, with the highest representation in the 41–45 age group (22.1%). A notable 21.5% did not disclose their age. The majority were married and had children, with 42.7% reporting two children. In terms of education, 59.6% held undergraduate degrees, while 37.5% had postgraduate qualifications and 2.9% held a PhD. Regarding multilingualism beyond English, 59.9% reported knowledge of one additional foreign language, and 22.5% knew two or more, highlighting a relatively high degree of language proficiency among the participants.

Table 3 outlines the participants’ professional roles and organizational contexts. Most participants (97.1%) reported having operational specialties, and 72.3% worked in operational units equipped with radar. The majority held operational roles (87.0%), with a smaller proportion in supervisory or administrative positions. In terms of scheduling, a substantial 74.9% followed a 24 h rotating shift pattern, reflecting the demanding nature of air traffic control work. These demographic and job-related profiles provide critical context for interpreting the study’s findings on occupational health, job satisfaction, and workplace well-being.

On what concerns the participants’ responses for the workplace climate, the majority of participants described their workplace climate as friendly/familial (35.5%), relaxed/comfortable (31.6%), or encouraging/supportive (17.3%), while only 15.3% reported a rigid environment with strict rules. The most frequently reported emotional states experienced during work were irritation (150 reports), anger (138), nervousness (131), and fatigue (121), followed closely by burnout (102). Less commonly, participants mentioned difficulty concentrating, overstimulation, despair, isolation, and depression, while only a small minority (18) indicated experiencing none of these symptoms. Staff recruitment emerged as the most frequently mentioned measure, followed by the provision of more training and an objective staff evaluation. Other frequent, yet slightly less-cited, suggestions included improvement of workplace health and safety conditions, addition or renewal of equipment, redesign of service delivery processes, and fair distribution of workload.

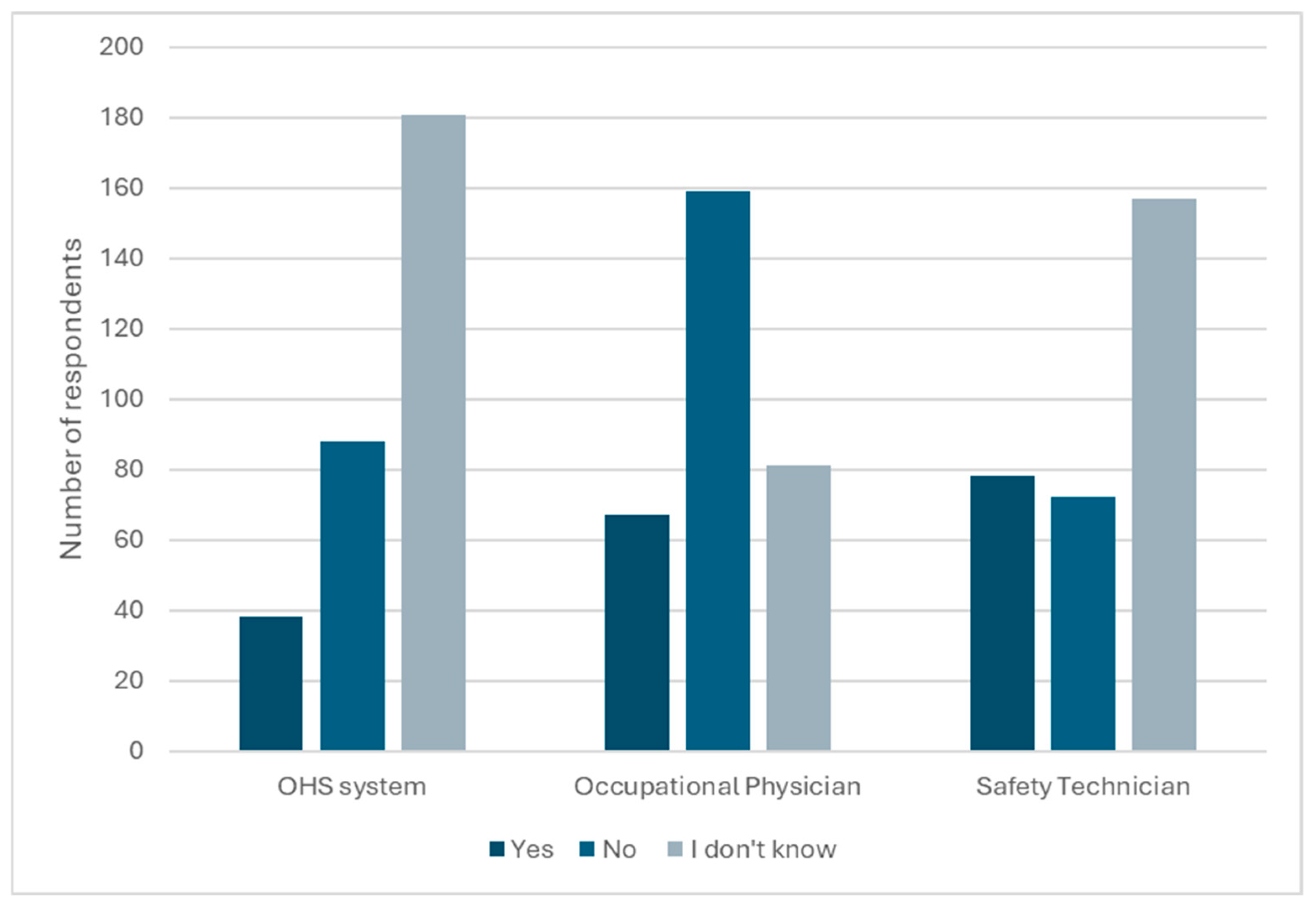

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in perceived workplace safety based on the presence of an occupational health and safety system in the respondent’s organizational unit (

Figure 2). The results revealed a significant difference between the groups, F (2, 304) = 5.48,

p = 0.0046. Post hoc comparisons using independent-sample

t-tests indicated that participants who reported the presence of a health and safety system (mean = 3.13, SD = 0.66) perceived their workplace as significantly safer than those who reported no such system (mean = 2.65, SD = 0.96), t(124) = 2.83,

p = 0.005. However, there was no significant difference between the participants who were aware of the presence of a system and those who did not know whether there was a system or not.

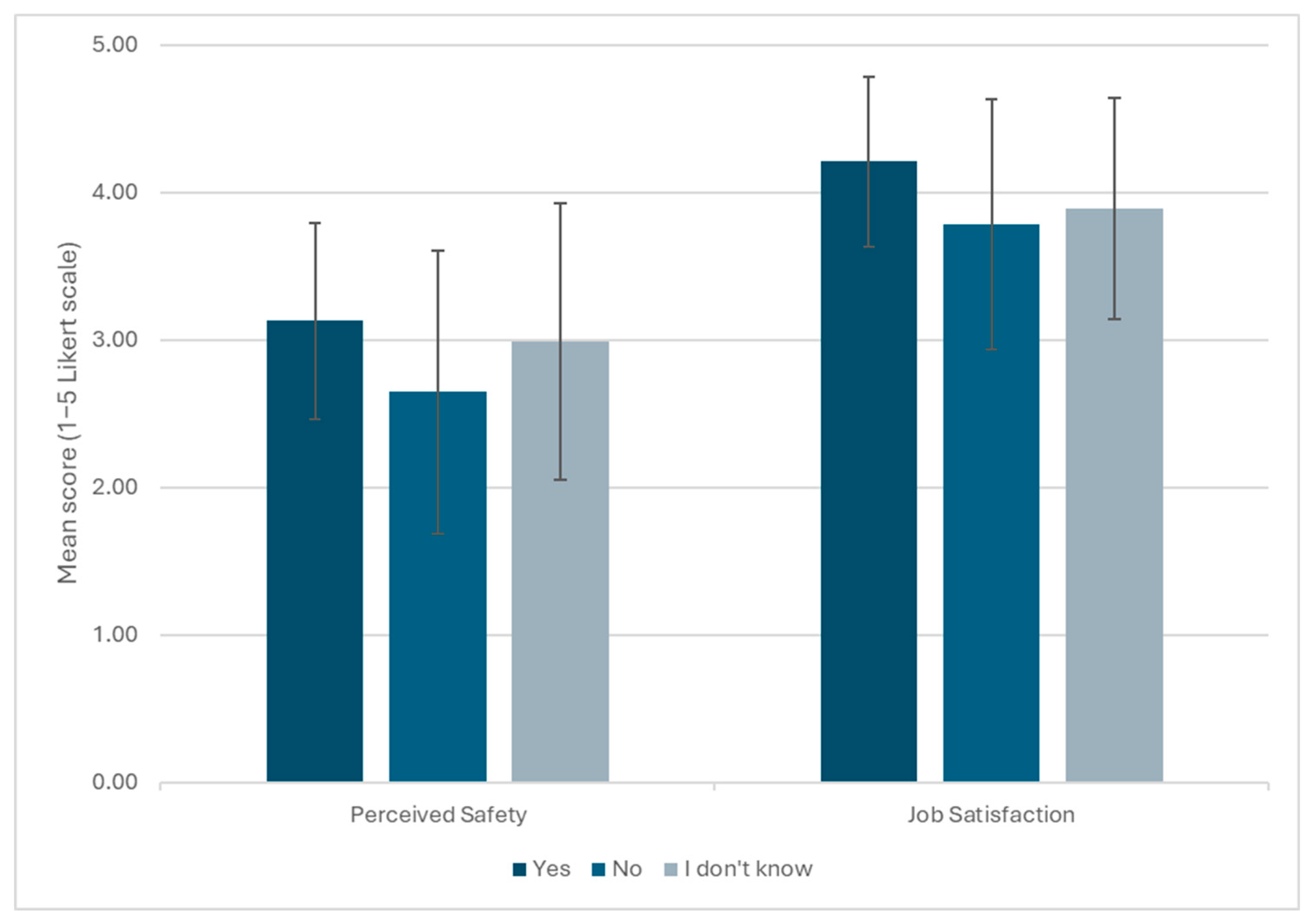

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine whether job satisfaction differs depending on whether the organizational unit has an occupational health and safety system. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in job satisfaction between the three groups (F(2, 304) = 4.18, p = 0.016). Post hoc comparisons using independent-sample t-tests indicated that participants who reported that their unit had an OHS system were significantly more satisfied (mean = 4.21, SD = 0.58) than those who answered No (mean = 3.78, SD = 0.85) and those who answered “I don’t know” (mean = 3.90, SD = 0.75) (p = 0.006 and 0.015, respectively).

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between participants’ perceptions of workplace safety and their overall job satisfaction, categorized by the reported presence of a health and safety (H&S) system in their organizational unit. Participants who confirmed the existence of an H&S system reported the highest mean levels of both perceived safety and job satisfaction. In contrast, those who indicated the absence of such a system reported statistically significantly lower scores on both dimensions. Interestingly, participants who were unsure about the presence of an H&S system tended to report intermediate levels of safety perception and satisfaction. The comparison between participants who reported the presence of an OHS system and those who did not showed a significant difference in job satisfaction (

p = 0.0056) and perceived safety (

p = 0.0058), both below the standard significance threshold of

p < 0.05. The error bars in the chart represent the standard deviations, indicating some variability within each group. These findings suggest that awareness and clarity regarding the presence of structured health and safety protocols may play an important role in shaping both perceived security and satisfaction in the workplace.

Awareness of a health and safety system is further associated with differences in workplace stress. The results of the one-way ANOVA showed that, while there were observable differences in the average stress levels among the groups—“Yes” (mean = 2.68, SD = 1.09), “No” (mean = 2.91, SD = 0.88), and “I don’t know” (mean = 2.64, SD = 0.88)—these differences were not statistically significant, F(2, 304) = 2.72, p = 0.0678. Similarly, no significant impact (p = 0.09) of the reported presence of a health and safety system was found on the level of insecurity felt by ATCOs.

Figure 4 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between key workplace variables. Perception of safety was positively correlated with both the perception of H&S implementation (r = 0.58) and job satisfaction (r = 0.34), indicating that employees who perceive a safer work environment also tend to view health and safety systems more favorably and report higher levels of job satisfaction. Conversely, perception of safety was negatively associated with work stress (r = −0.22), suggesting that greater perceived safety is linked to lower levels of reported stress. Perception of H&S implementation also showed a positive correlation with job satisfaction (r = 0.28) and a very weak correlation with work stress (r = 0.02). Notably, work stress was negatively correlated with job satisfaction (r = −0.27).

The composite measure of average training received was calculated based on the three Likert scale questions (technical, OHS, and quality/safety of services). The results indicate that average training is positively correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.35) and job performance (r = 0.43), suggesting that employees who receive more training tend to report higher levels of satisfaction and higher unit-level problem-solving effectiveness. In contrast, average training was negatively correlated with job insecurity (r = −0.22), implying that employees who receive more training may feel more secure. The correlation between training and work stress was very weak and negative (r = −0.05), indicating essentially no relationship between the two in this dataset.

Clarity of role and objectives were calculated as a composite construct of understanding broader team goals and understanding one’s personal contribution. Role clarity was positively associated with perceptions of unit effectiveness (r = 0.24) and job satisfaction (r = 0.26), indicating that, when employees have a clearer understanding of their goals and what is expected of them, they tend to feel more satisfied and view their unit as more effective. In contrast, role clarity was negatively correlated with feelings of exhaustion (r = −0.20) and showed very weak negative relationships with workplace stress (r = −0.02).

A composite autonomy index was created by averaging the responses to two items assessing the employees’ ability to control their work pace and break timing. The results showed a moderate positive correlation with job satisfaction (r = 0.27), suggesting that employees who have more control over their work pace and break times tend to feel more satisfied with their jobs. In contrast, perceived autonomy was negatively correlated with workplace stress (r = −0.21) and exhaustion (r = −0.31), indicating that greater autonomy is associated with lower stress levels and reduced feelings of burnout.

Workplace stress was also negatively correlated with perceived safety (r = −0.22), suggesting that greater stress levels are associated with lower safety perceptions and reduced satisfaction. No meaningful correlation was observed between stress and the perception of implemented health and safety measures (r = 0.015), implying that stress may not be directly influenced by formal compliance but more by personal or contextual workplace factors. Supervisor encouragement in decision-making correlated negatively with exhaustion (r = −0.33) and positively with job satisfaction (r = 0.33). Additionally, supervisor encouragement and colleague support were also found to be positively correlated (r = 0.036).

5. Discussion

The fundamental role of Air Traffic Controllers in the safety of the aviation industry [

2] makes research on their occupational health and safety conditions and overall well-being essential. While in other researched industries, such as manufacturing, safety and operational performance may be viewed as competing priorities, in ATC, safety behavior is inherently integrated into the operational performance [

5,

10]. The OHS of Air Navigation Services Providers’ operational workplace is a main parameter supporting the quality of services and driving air transport development and sustainable aviation growth [

6].

The complexity and multitasking of air traffic controlling procedures [

3,

6], the fast decision-making processes [

3], the dedicated infrastructures, and the high use of electronic equipment, as well as their communication interrelationship with different functions of airport business [

6], place ATCOs at an increased risk of stress-related outcomes [

2], making the organizational support mechanisms particularly important.

The findings of this study also draw attention to the existence of a sector committed to values of safety and an inability to properly ensure the well-being of the personnel. Air traffic control operates in a highly structured, safety-oriented environment, subject to a thorough set of regulations, standard compliance, and audit procedures. However, the study finds that mental stress, physical decline, and emotional weariness are still common. An explanation for the condition could reside in the history of occupational safety systems, which have commonly been focused on the achievement of a mere technical compliance, accident elimination, and defense against physical hazards. Although such systems (e.g., ISO 45001, ICAO procedures) are indispensable, they all too often overlook the chronic and frequently ignored mental pressures stemming from relentless cognitive demands, temporal pressure, and emotional difficulties. Cultural barriers resistant to the aviation industry, such as mental health-related stigma, reluctance to disclose psychological suffering, and a fear of disciplinary sanctions when raising such issues in the work setting, could impede the adoption of a wider spectrum of well-being approaches. We must recognize and correct such a gap to evolve the culture of safety from a purely procedural system toward the promotion of true performance, as well as individual resilience.

Understanding how ATCOs perceive the presence and the impact of OHS systems becomes a key point in assessing not only their individual sense of safety but also their overall satisfaction and psychological well-being. Our analysis indicated that participants who reported the presence of an OHS system perceived their workplace as significantly safer than those who reported no such system. Hence, the existence of structured measures allows ATCOs to feel confident in their work environment. The presence of a formal health and safety system in the organizational unit was also found to be positively associated with employees’ general job satisfaction. Participants who reported being aware of such a system scored higher levels of job satisfaction than both those who reported no such system and also from those who reported not knowing of the presence of a system or not. The results emphasize the role of clearly communicated and implemented protocols for the well-being of the employees in the air traffic control field.

Although knowing about the presence of a health and safety system was not found to statistically affect workplace stress, there was a trend suggesting that further research with a larger sample may be warranted to explore potential relationships. With regards to training, our study showed that employees who perceived their training as adequate across multiple domains (technical, OHS, quality, and safety) were more likely to perceive their organizational units as more capable of solving problems while also expressing higher satisfaction with their job. While training is not the sole source of satisfaction, it appears to be an important contributing factor. This finding underscores the importance of thorough and continuous training, potentially highlighting that well-trained personnel not only feel an adequate level of individual competence but also perceive a higher collective effectiveness and confidence in their organizational units. Indeed, high-quality training is fundamental in the aviation industry, with the competence of ATCOs being critical to ensuring the safety standards that define the air transport industry [

53]. Our results are in alignment with recent research [

11], which revealed that ATCOs consistently identify training as vital for not only enhancing individual skills but also overall operational effectiveness.

The modest positive correlation identified between role clarity and unit performance, as well as job satisfaction, aligns with the JD-R theory. In a recent update of the JD-R theory [

54], it is emphasized that clear role definitions work towards a more motivational environment that enhances job satisfaction. The relationship between role clarity or expectations with satisfaction levels has been well-documented in recent empirical evidence [

55,

56,

57,

58]. Among the published results, it has been shown that clear role definitions reduce work stress. In our study, role clarity was only very weakly negatively correlated (r = −0.02) with stress. This inconsistency may be attributed to the highly procedural and regulated nature of ATCO work, where roles are inherently well-defined, leaving limited variation in perceived clarity across participants. In such contexts, even when roles are clear, other demands—such as time pressure, traffic complexity, or fatigue—may play a more dominant role in generating stress. However, even if clarity alone does not significantly reduce stress, it seems to contribute to a more purposeful work environment, which may, in turn, support individual and organizational outcomes.

While this study offers a valuable empirical contribution grounded in the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, future research could benefit from the application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test more complex theoretical pathways. SEM would allow for a simultaneous estimation of relationships among latent variables, enabling the examination of direct and indirect effects, such as how organizational resources (e.g., training, autonomy, role clarity) buffer the impact of job demands on stress and job satisfaction. Such modeling could further elucidate the underlying structure of employee well-being and safety perceptions within high-risk environments like air traffic control. Implementing SEM would require expanded multi-item measures for each construct, a larger sample size to meet statistical power requirements, and ideally, longitudinal data to test directional hypotheses with greater rigor.

According to the

Fatigue Management Guide for Air Traffic Service Providers, in 2016 [

59], control by ATCOs over shift schedules, break timing, and rest planning is recognized as essential for reducing strain and sustaining performance. In our study, the ability to exercise some level of autonomy in defining the pace of work and breaks was positively related to job satisfaction and negatively related to stress and exhaustion. Despite the strict procedures under which ATCOs operate, a level of autonomy may allow for an adjustment of work pace or a break schedule that can assist in managing pressure. As highlighted by [

3], ATCOs play an active role in regulating their cognitive load by managing traffic flows, coordinating with sectors, and applying procedural flexibility when appropriate. These behaviors, while occurring within a structured operational environment, reflect a form of autonomy in execution that supports performance stability and operational resilience.

A positive safety culture, characterized by open communication, incident reporting, and management commitment to health, safety, and quality, can work as a buffer factor for job-related stress. A strong safety culture has, herein, been correlated with lower stress levels. Supervisor encouragement in decision-making was also moderately supported (r = 0.36), suggesting that leadership engagement may foster an overall more supportive work climate.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence on the importance of occupational health and safety (OHS) systems in shaping workplace experiences, well-being, and performance outcomes among Air Traffic Controllers (ATCOs) in the Hellenic Air Navigation Services Provider. The findings confirm that the perceived presence of an OHS system is strongly associated with increased feelings of safety and significantly higher levels of job satisfaction. While no statistically significant impact was found on workplace stress or job insecurity, the observed trends suggest that the visibility and clarity of health and safety procedures may nonetheless contribute to a psychologically safer work environment. Crucially, this research highlights the broader organizational dynamics that influence ATCOs’ well-being. Adequate and multi-dimensional training, role clarity, and autonomy emerged as significant predictors of job satisfaction and perceived unit effectiveness, while also mitigating exhaustion and stress. The positive correlations among supervisor support, peer relationships, and employee outcomes further underscore the role of leadership and team climate in buffering the demands of high-stress environments.

These findings align with the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) theoretical framework, emphasizing that well-structured organizational resources can protect against burnout and enhance both motivation and performance. As air traffic volumes continue to grow, these insights point to the necessity of investing in robust OHS frameworks, targeted training programs, and participatory leadership practices to support the resilience and effectiveness of the ATCO workforce. In sum, fostering a workplace culture that prioritizes safety, clarity, support, and development is not only ethically imperative but operationally strategic. In addition, future research may adopt advanced modeling techniques such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to validate and extend the theoretical pathways proposed in this study. SEM could clarify the interplay between job demands and resources by modeling latent constructs and mediating variables within the JD-R framework. To support such analyses, further measurement refinement, including validated multi-item scales for all key constructs, and larger, more diverse samples would be essential. Longitudinal designs could also enhance causal inference and shed light on the dynamic evolution of psychological outcomes in relation to organizational interventions.