Occupational Health Risks at Truck Stops: Evaluating Service Gaps and Safety Needs for Long-Haul Drivers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Team

2.2. Design of the Study

2.2.1. Direct Observation

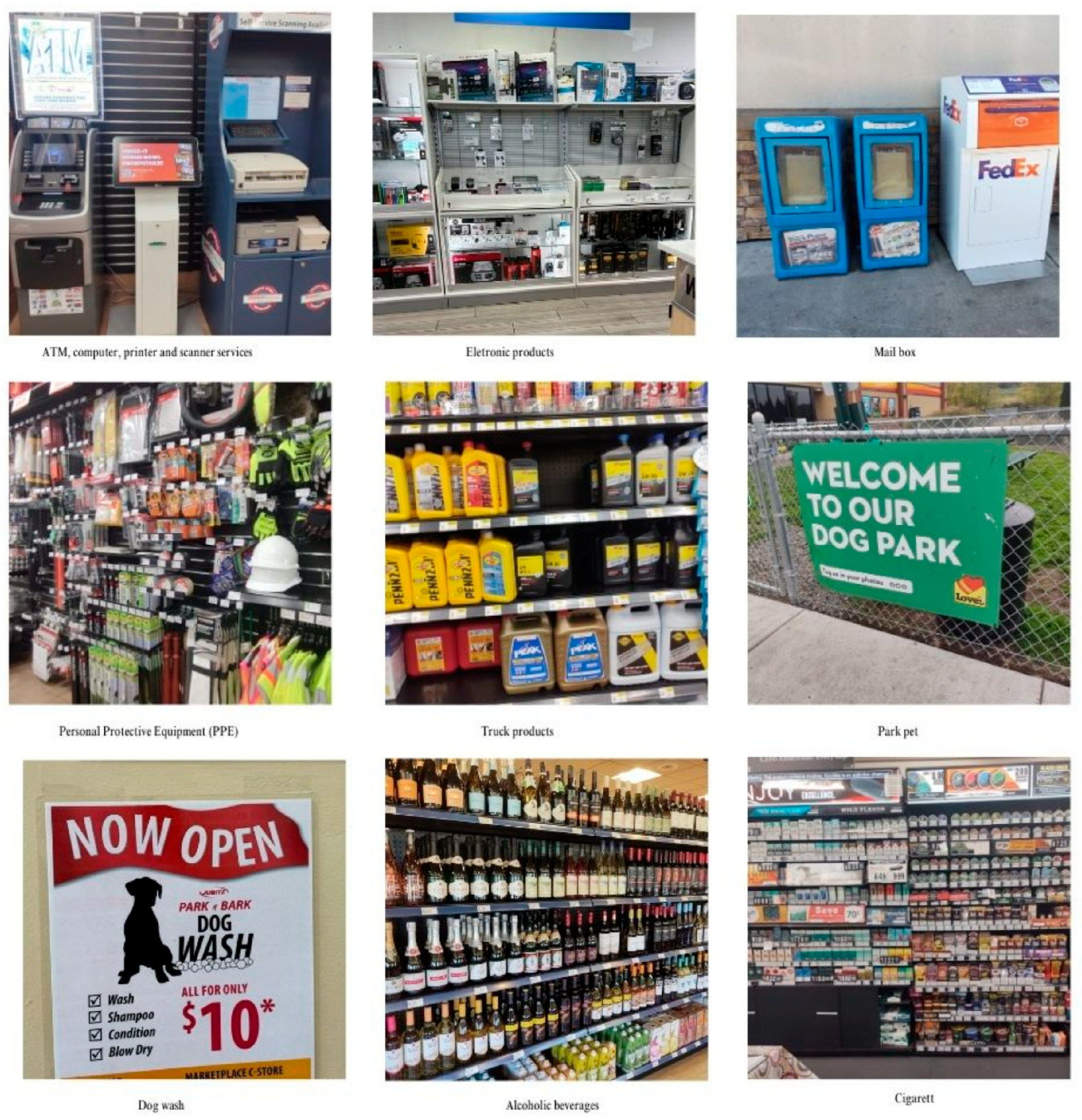

2.2.2. Photography

2.3. Study Setting and Period

2.4. Literature Review and Conceptual Definitions

2.5. Instruments and Procedures for Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Food

3.2. Physical Activity

3.3. Personal Hygiene and Health

3.4. Rest

3.5. Safety

3.6. Other Services

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LHTD | Long-Haul Truck Driver |

| AED | Automatic External Defibrillator |

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| DECS | Descriptors in Health Sciences |

| MESH | Medical Subject Headings |

| ODOT | Oregon Department of Transportation |

| US | United States |

References

- International Labor Organization. Safe and Healthy Working Environments for All. Realizing the Fundamental Right to a Safe and Healthy Working Environment Worldwide. 2023. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@safework/documents/publication/wcms_906187.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Sendall, M.C.; McCosker, L.K.; Ahmed, R.; Crane, P. Truckies’ nutrition and physical activity: A cross-sectional survey in Queensland, Australia. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 10, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J.; Vos, A.G.; Lalla-Edward, S.T.; Venter, W.D.F.; Scheuermaier, K. Relationship between sleep disorders, HIV status and cardiovascular risk: Cross-sectional study of long-haul truck drivers from Southern Africa. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 78, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeown, M.L.; Crizzle, A.M. Examining Long-Haul Truck Driver Needs and Preferences to Improve the Truck Stop Environment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2025, 67, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.C.; Hernandez, S.; Jessup, E.L.; North, E. Perceived safe and adequate truck parking: A random parameters binary logit analysis of truck driver opinions in the Pacific Northwest. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, C.; Brewster, R.A. comparative analysis of truck parking travel diary data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M.K.; Houghtaling, B.; Winkler, M.R.; Hege, A. Rethinking efforts to improve dietary patterns among long-haul truck drivers: Transforming truck stop retail food environments through upstream change. Am. J. Health Promot. 2023, 37, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, P.J.W.; Prawitz, A.D.; Lukaszuk, J.M. Long-haul truck drivers want healthful meal options at truck-stop restaurants. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 2125–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lise, F.; Shattell, M.; Garcia, R.P.; Rodrigues, K.C.; Ávila, W.T.; Garcia, F.L.; Schwartz, E. Long-Haul Truck Drivers Perceptions of Truck Stops and Rest Areas: Focusing on Health and Wellness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, L.H.; Lichtenstein, B.; St Lawrence, J.S.; Murray, M.; Russell, G.B.; Hook III, E.W. Health risks of American long-haul truckers: Results from a multi-site assessment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, e349–e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hege, A.; Lemke, M.K.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. The impact of work organization, job stress, and sleep on the health behaviors and outcomes of US long-haul truck drivers. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, S.A.; Alonso, F.; Cendales, B.; Llamazares, J. More than just “stressful”? Testing the mediating role of fatigue on the relationship between job stress and occupational crashes of long-haul truck drivers. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, M.K.; Oberlin, D.J.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Hege, A.; Sönmez, S.; Wideman, L. Work, physical activity, and metabolic health: Understanding insulin sensitivity of long-haul truck drivers. Work 2021, 69, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bschaden, A.; Rothe, S.; Schöner, A.; Pijahn, N.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. Food choice patterns of long-haul truck drivers driving through Germany, a cross sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorafi, K.J.; Evans, B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. HERD 2016, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.J.; Peres, J.A.S.; Wanderley, J.C.V.; Correia, L.M.; Peres, M.H.M. Pesquisa Social: Métodos e Técnicas, 1st ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, M.R. Testimonio y poder de la imagen. In Etnografia: Metodología Cualitativa en la Investigación Sociocultural, 1st ed.; Baztán, A.A., Ed.; Boixareu Universitaria/Marcombo: Barcelona, Spain, 1995; pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D. The role of photograpy in organization research: A reengineering case illustration. J. Manag. Inq. 2001, 10, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechenberg, F. Notas etnográficas sobre o retrato: Repensando as práticas de documentação fotográfica em uma experiência de produção compartilhada das imagens. CadernosAA. 2014, 3, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasniuk, S.; Lemke, M.K.; Hassoun, A.; Hege, A.; Crizzle, A.M. Improving truck stop environments to support long-haul truck driver safety and health: A scoping review. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 185, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT). Oregon Commercial Truck Parking Study. 2019. Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/ODOT/Projects/Project%20Documents/TM4_Truck%20Parking%20Inventory_draft_final.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT). Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/odot/mct/pages/oregon-truck-stops.aspx (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Lincoln, J.E.; Birdsey, J.; Sieber, W.K.; Chen, G.X.; Hitchcock, E.M.; Nakata, A.; Robinson, C.F. A pilot study of healthy living options at 16 truck stops across the United States. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S.; Shattell, M.; Strack, R.; Haldeman, L.; Jones, V. Barriers to truck drivers’ healthy eating: Environmental influences and health promotion strategies. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2011, 26, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hege, A.; Lemke, M.K.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. Occupational health disparities among US long-haul truck drivers: The influence of work organization and sleep on cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crizzle, A.M.; Mclean, M.; Malkin, J. Risk factors for depressive symptoms in long-haul truck drivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.K.; Vingilis, E.; Terry, A.L. Qualitative study of long-haul truck drivers’ health and healthcare experiences. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Health Ministery. GM/MS Ordinance No. 1,884, of 9 August 2021. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-gm/ms-n-1.884-de-9-de-agosto-de-2021-337521478 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

| Service | MeSH Term | Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Food | Diet (diet) | Regular method of eating food and drink adopted by a person or animal. |

| Personal hygiene and health | Hygiene | Science that deals with the implementation and maintenance of health of the individual and the group. It includes procedures, conditions, and practices that lead to health. |

| Occupational Health | Promotion and maintenance in the highest degree of the physical, mental, and social well-being of workers in all occupations; prevention among workers of occupational diseases caused by their working conditions; protection of workers in their labors, from the risks resulting from adverse health factors; placement and conservation of workers in occupational environments adapted to their physiological and psychological skills. | |

| Physical activity | Exercise | Usually regular physical activity, performed with the intention of improving or maintaining physical fitness or health. It is different from physical exertion and is focused mainly on physiological and metabolic responses to energy use. |

| Rest | Rest | Freedom of activity. |

| Safety | Safety | No exposure to danger and protection against the occurrence or risk of injury or loss. It suggests optimal precautions in the workplace, in the street, in the home, etc., and includes personal safety as well as property safety. |

| Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Food | ||

| 1- Healthy foods (fresh fruits, vegetables and salads, boiled eggs, and chilled natural sandwiches) | 11 | 85 |

| 2- Healthy drinks (water, natural juice, milk, tea, coffee, yogurts) | 11 | 85 |

| 3- On-site restaurant with tables and chairs | 11 | 85 |

| 4- Restaurant nearby | 11 | 85 |

| 5- Availability of public space for meals with tables and chairs | 03 | 23 |

| Physical activity | ||

| 1- Availability of gym for physical exercise | 00 | 00 |

| 2- Space for hiking | 00 | 00 |

| Rest | ||

| 1- Internet access | 12 | 92 |

| 2- Rest area with sofa and TV (lounge) | 07 | 54 |

| 3- Hotels on site or nearby | 07 | 54 |

| 4- Green area with benches, chair for rest, and/or tables | 02 | 15 |

| Personal hygiene and health | ||

| 1- Bathroom equipped with toilet, sink, soap, paper, and mirror | 11 | 85 |

| 2- Bathroom with shower | 11 | 85 |

| 3- Commercialization of products for personal hygiene and or pharmaceuticals | 11 | 85 |

| 4- Public laundry service | 09 | 69 |

| 5- External cardiac defibrillator | 01 | 8.0 |

| 6- Health services | 01 | 8.0 |

| Security | ||

| 1- Road with signs informing the stopping place | 13 | 100 |

| 2- There is a parking area with lighting | 13 | 100 |

| 3- Paved parking lot | 13 | 100 |

| 4- Exclusive fueling station for trucks | 12 | 92 |

| 5- Parking for the truck separated from the passenger cars | 12 | 92 |

| 6- Fire extinguishers | 12 | 92 |

| 7- Full-time operation (24 h/7 days of the week) | 11 | 85 |

| 8- Parking with ramp for accessibility | 11 | 85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lise, F.; Garcia, F.L.; Shattell, M.; Kincl, L. Occupational Health Risks at Truck Stops: Evaluating Service Gaps and Safety Needs for Long-Haul Drivers. Safety 2025, 11, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030087

Lise F, Garcia FL, Shattell M, Kincl L. Occupational Health Risks at Truck Stops: Evaluating Service Gaps and Safety Needs for Long-Haul Drivers. Safety. 2025; 11(3):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030087

Chicago/Turabian StyleLise, Fernanda, Flávia Lise Garcia, Mona Shattell, and Laurel Kincl. 2025. "Occupational Health Risks at Truck Stops: Evaluating Service Gaps and Safety Needs for Long-Haul Drivers" Safety 11, no. 3: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030087

APA StyleLise, F., Garcia, F. L., Shattell, M., & Kincl, L. (2025). Occupational Health Risks at Truck Stops: Evaluating Service Gaps and Safety Needs for Long-Haul Drivers. Safety, 11(3), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11030087