A Study on the Factors Affecting Safety Behaviors and Safety Performance in the Manufacturing Sector: Job Demands-Resources Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Subjects

2.2. Measurement and Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Measurement Instrument

2.2.2. Research Hypothesis

- H1: Job demands will negatively impact workers’ safety behavior and organizational safety outcomes.

- H1a: Workers’ safety behavior will decrease as environmental, physical, and psychological hazards (job demands) increase.

- H1b: The incidence of occupational accidents and diseases will increase as environmental, physical, and psychological hazards (job demands) increase.

- H2: Safety attitude of top management, the culture and systems oriented toward safety, and competency of middle managers regarding safety (job resources) will have a moderating effect on the relationship among job demands, workers’ safety behavior, and organizational safety outcomes.

- H2a: The negative relationship between job demands and workers’ safety behavior will be weakened as job resources increase.

- H2b: The positive relationship between job demands and the incidences of occupational accidents and diseases will be weakened as job resources increase.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability, Validity, and Correlation Between Variables

3.2. Hypothesis Verification of the Main Effect of Job Demands

3.3. Hypothesis Verification of the Moderating Effect of Job Resources

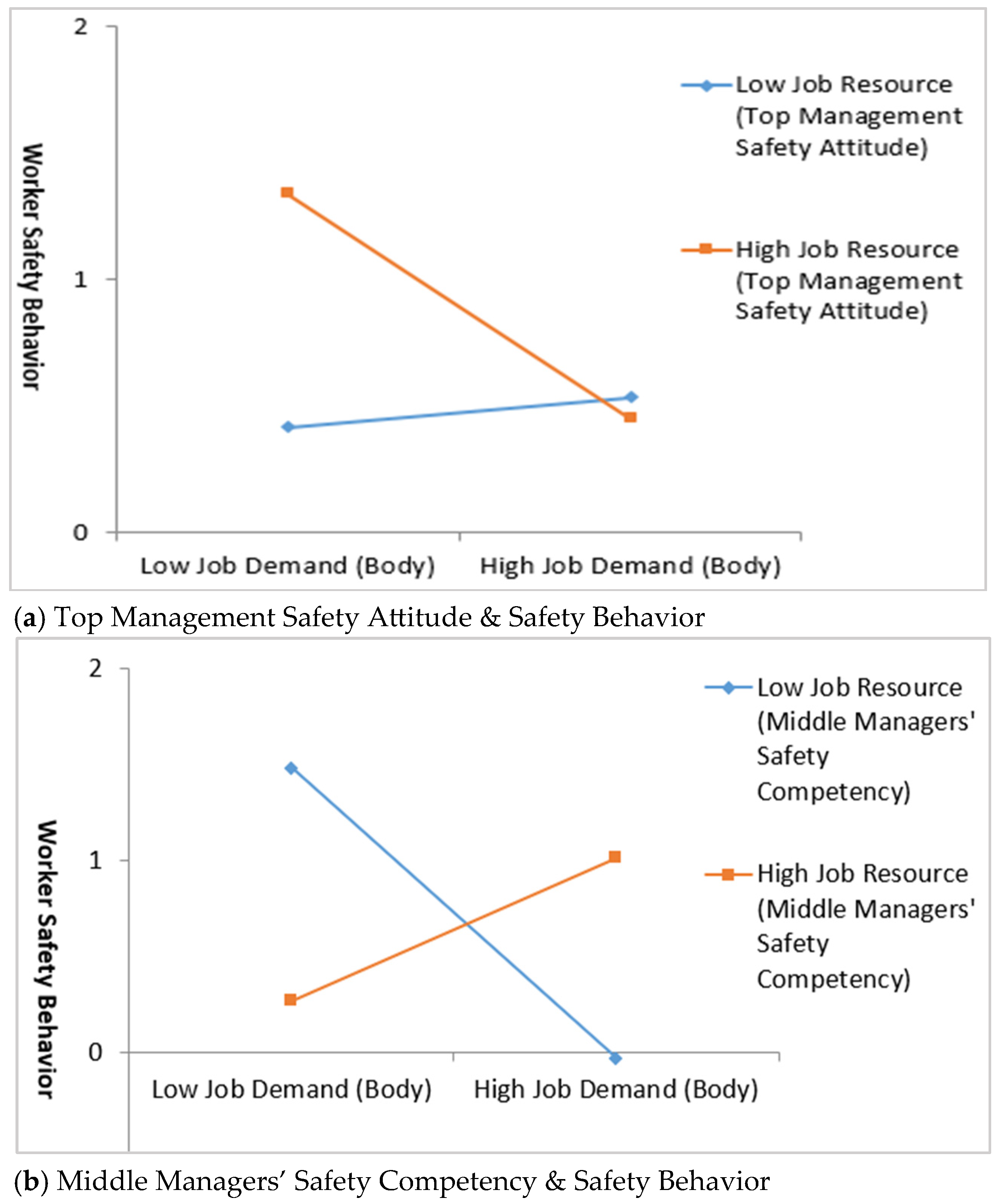

3.3.1. Relationship Between Job Demands, Job Resources, and Safety Behaviors

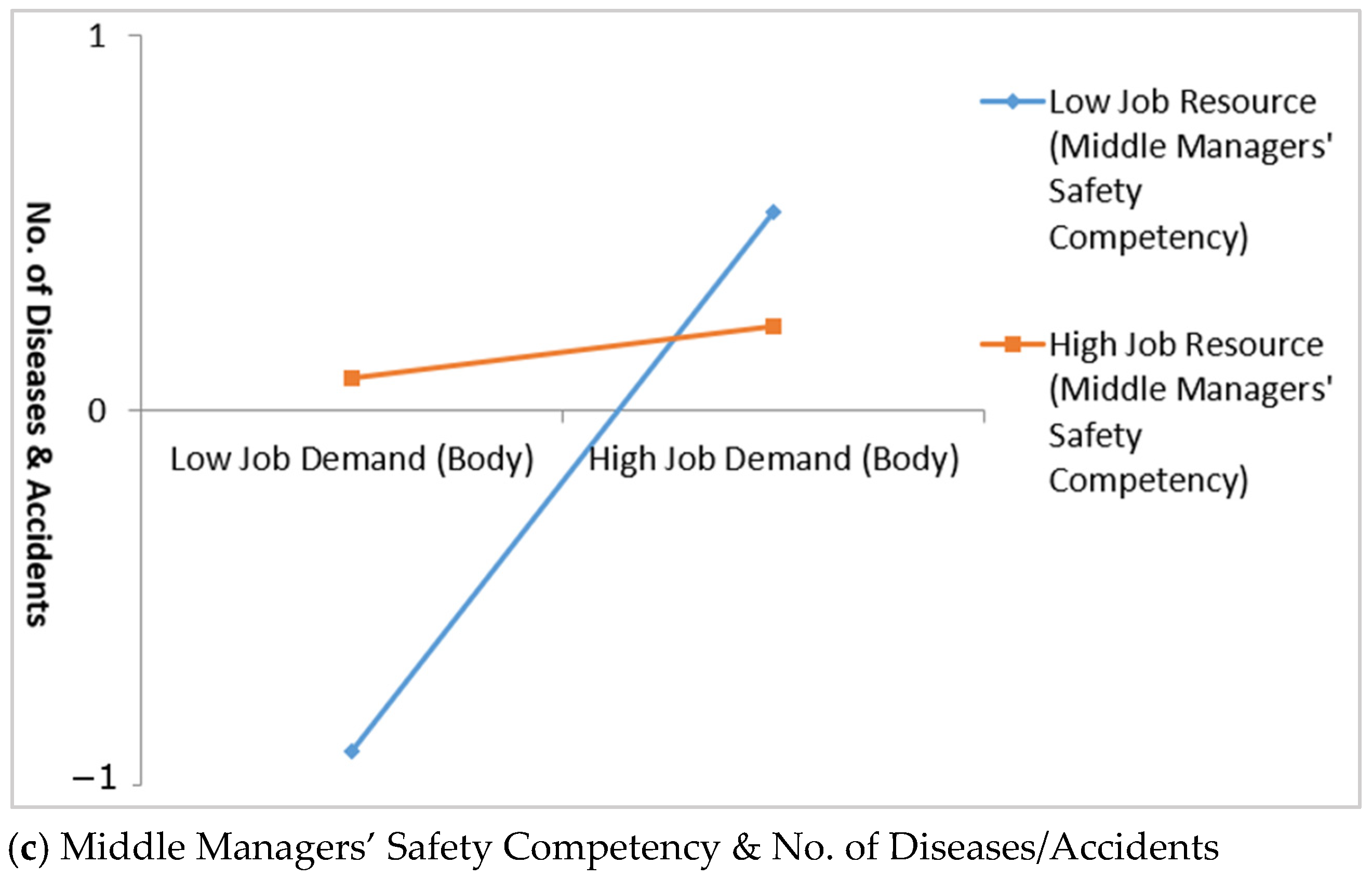

3.3.2. Relationship Between Job Demands, Job Resources, and Number of Occupational Accidents and Diseases

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhandari, S.; Hallowell, M.R.; Correll, J. Making construction safety training interesting: A field-based quasi-experiment to test the relationship between emotional arousal and situational interest among adult learners. Saf. Sci. 2019, 117, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, J.; Chmiel, N.; Hansez, I. Jobs and safety: A social exchange perspective in explaining safety citizenship behaviors and safety violations. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110 Pt A, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripamonti, S.; Giuseppe, S. Weak knowledge for strengthening competences: A practice-based approach in assessment management. Manag. Learn. 2015, 43, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, A.; Hallowell, M.R. Revamping occupational safety and health training: Integrating andragogical principles for the adult learner. Australas. J. Constr. Econ. Build. 2013, 13, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslen, S.; Hopkins, A. Do incentives work? A qualitative study of managers’ motivations in hazardous industries. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Stylianou, M.S.; Nikolaou, I.E. Evaluating the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of occupational health and safety disclosures. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembe, A.E. The social consequences of occupational injuries and illnesses. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2001, 40, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, D.P.; Richardson, D.B.; Wolf, S.H.; Runyan, C.W.; Butts, J.D. Fatal occupational injuries in a southern state. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 145, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, K.Y.; Spitzmueller, C.; Cigularov, K.; Thomas, C.L. Linking safety knowledge to safety behaviours: A moderated mediation of supervisor and worker safety attitudes. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, M.; Malouf, M. Safety training and positive safety attitude formation in the Australian construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2019, 113, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugheri, S.; Cappelli, G.; Trevisani, L.; Kemble, S.; Paone, F.; Rigacci, M.; Bucaletti, E.; Squillaci, D.; Mucci, N.; Arcangeli, G. A Qualitative and Quantitative Occupational Exposure Risk Assessment to Hazardous Substances during Powder-Bed Fusion Processes in Metal-Additive Manufacturing. Safety 2022, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Alam, M.R.; Abdullah, S.M.; Mamun, A.L.; Hossain, M.S. Occupational safety practice among metal workers in Bangladesh: A community-level study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2022, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronkhorst, B. Behaving safely under pressure: The effects of job demands, resources, and safety climate on employee physical and psychosocial safety behavior. J. Saf. Res. 2015, 55, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, L.; Yao, X.; Li, Y. Job demands, job resources and safety outcomes: The roles of emotional exhaustion and safety compliance. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 51, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.J.; Kim, N.K.; Son, M.; Hong, A.J. A study on the influence of electronic construction site safety managers’ job resources, job demands, and organizational commitment. J. Korean Soc. Saf. 2021, 36, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Oh, S.; Lim, S. A study of improvement on Accident Rate Index of construction industry. Korean J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 17, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 45001; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Korea Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (KOSHA). Final Report of the 10th Industrial Safety and Health Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www.kosha.or.kr/oshri/researchField/downTrendsSurvey.do (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Enshassi, A.; El-Rayyes, Y.; Alkilani, S. Job Stress, Job Burnout and Safety Performance in the Palestinian Construction Industry. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2015, 20, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The Impact of Organizational Climate on Safety Climate and Individual Behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, N.; Fang, D.; Wu, H. Supervisor-focused Behavior-based Safety Method for the Construction Industry: Case Study in Hong Kong. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 05017009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Hyun, E.-J.; Yoon, Y.-G. The Impact of Physical Hazards on Workers’ Job Satisfaction in the Construction Industry: A Case Study of Korea. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.J.; Do, B. Effects of Organizational Psychological Safety Climate on Safety Behavior in the Contexts of Construction Workers—Multiple Additive Moderation Effects of Job Stressors and Physical Hazard Factors. J. Korean Soc. Constr. 2024, 36, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Migliaccio, G.C.; Lin, K.-Y.; Seto, E.Y.W. Workforce Development: Understanding Task-Level Job Demands-Resources, Burnout, and Performance in Unskilled Construction Workers. Saf. Sci. 2020, 123, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, K.; Bowen, P.; Edwards, P. Stress Among South African Construction Professionals: A Job Demand-Control-Support Survey. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2016, 34, 700–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at Work: A Meta-Analytic Investigation of the Link Between Job Demands, Job Resources, Burnout, Engagement, and Safety Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company Size by Number of Employees | No. of Companies | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 20~49 | 2273 | 69.8 |

| 50~99 | 572 | 17.6 |

| 100~299 | 301 | 9.3 |

| 300~ | 109 | 3.3 |

| Total | 3255 | 100 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Size 20~49 | 0.70 | 0.46 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Size 50~99 | 0.18 | 0.38 | −0.70 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Size 100~299 | 0.09 | 0.29 | −0.49 | −0.15 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Safety Dept. | 0.11 | 0.32 | −0.36 | 0.05 | 0.24 | |||||||||

| 5 | ISO 45001 | 0.25 | 0.43 | −0.16 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| 6 | JD (Environment) | 10.73 | 0.59 | −0.18 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.00 | (0.91) | ||||||

| 7 | JD (Body) | 20.08 | 0.78 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.71 | (0.86) | |||||

| 8 | JD (Stress) | 10.70 | 0.56 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.49 | 0.48 | (0.84) | ||||

| 9 | JR (Top Management Safety Attitude) | 40.54 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.27 | (0.89) | |||

| 10 | JR (Safety Systems & Culture) | 40.23 | 0.60 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.21 | −0.24 | −0.32 | 0.71 | (0.92) | ||

| 11 | JR (Middle Manager Safety Competency) | 40.21 | 0.66 | 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.24 | −0.25 | −0.32 | 0.58 | 0.70 | (0.92) | |

| 12 | Safety Behavior | 40.23 | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.28 | −0.30 | −0.33 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.66 | (0.83) |

| 13 | No. of Diseases & Accidents | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.06 |

| Variables | Safety Behavior | No. of Diseases/Accidents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

| Control Variable | Size 20~49 | 0.166 *** | 0.008 | −0.024 | −0.040 |

| Size 50~99 | 0.139 *** | 0.006 | −0.044 | −0.055 | |

| Size 100~299 | 0.090 *** | 0.000 | −0.014 | −0.024 | |

| Safety Department | 0.034 | −0.019 | −0.030 | −0.034 | |

| ISO 45001 | 0.055 *** | −0.014 | −0.018 | −0.019 | |

| Independent Variable | Environment (JD) | −0.287 *** | −0.164 † | 0.135 *** | 0.348 ** |

| Moderator | Top Management Safety Attitude (JR) (A) | 0.211 *** | 0.128 | ||

| Safety Systems & Culture (JR) (B) | 0.604 *** | −0.171 † | |||

| Middle Manager Safety Competency (JR) (C) | −0.031 | 0.194 ** | |||

| Interaction | Environment (JD) × (A) | −0.239 † | −0.170 | ||

| Environment (JD) × (B) | −0.177 | 0.300 | |||

| Environment (JD) × (C) | 0.484 *** | −0.338 † | |||

| R2 | 0.091 | 0.641 | 0.018 | 0.023 | |

| ΔR2 | 0.550 *** | 0.005 † | |||

| F | 44.469 *** | 394.976 *** | 8.143 *** | 5.075 *** | |

| Variables | Safety Behavior | No. of Diseases/Accidents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

| Control Variable | Size 20~49 | 0.158 *** | 0.008 | −00.024 | −0.036 |

| Size 50~99 | 0.144 *** | 0.010 | −0.049 | −0.059 | |

| Size 100~299 | 0.081 ** | −0.002 | −0.014 | −0.019 | |

| Safety Department | 0.012 | −0.028 * | −0.020 | −0.021 | |

| ISO 45001 | 0.049 ** | −0.014 | −0.016 | −0.019 | |

| Independent Variable | Body (JD) | −0.294 *** | −0.192 * | 0.130 *** | 0.394 ** |

| Moderator | Top Management Safety Attitude (JR) (A) | 0.210 *** | 0.057 | ||

| Safety Systems & Culture (JR) (B) | 0.605 *** | −0.067 | |||

| Middle Manager Safety Competency (JR) (C) | −0.043 | 0.171 ** | |||

| Interaction | Body (JD) × (A) | −0.251 † | −0.015 | ||

| Body (JD) × (B) | −0.208 | 0.083 | |||

| Body (JD) × (C) | 0.564 *** | −0.325 † | |||

| R2 | 0.097 | 0.641 | 0.018 | 0.022 | |

| ΔR2 | 0.544 *** | 0.004 † | |||

| F | 47.461 *** | 3940.091 *** | 70.853 *** | 40.857 *** | |

| Variables | Safety Behavior | No. of Diseases/Accidents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

| Control Variable | Size 20~49 | 0.189 *** | 0.027 | −0.063 | −0.078 |

| Size 50~99 | 0.157 *** | 0.018 | −0.068 | −0.079 † | |

| Size 100~299 | 0.098 *** | 0.002 | −0.031 | −0.036 | |

| Safety Department | −0.010 | −0.037 ** | −0.016 | −0.015 | |

| ISO 45001 | 0.057 *** | −0.013 | −0.021 | −0.021 | |

| Independent Variable | Stress (JD) | −0.308 *** | −0.132 | 0.035 † | −0.011 |

| Moderator | Top Management Safety Attitude (JR) (A) | 0.167 ** | 0.058 | ||

| Safety Systems & Culture (JR) (B) | 0.538 *** | −0.158 | |||

| Middle Manager Safety Competency (JR) (C) | 0.096 † | 0.120 | |||

| Interaction | Stress (JD) × (A) | −0.115 | −0.008 | ||

| Stress (JD) × (B) | −0.011 | 0.225 | |||

| Stress (JD) × (C) | 0.205 ** | −0.168 | |||

| R2 | 0.108 | 0.633 | 0.003 | 0.006 | |

| ΔR2 | 0.525 *** | 0.003 | |||

| F | 53.687 *** | 380.762 *** | 1.144 | 1.213 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, H.J.; Rhee, S.-Y.; Kim, N.K. A Study on the Factors Affecting Safety Behaviors and Safety Performance in the Manufacturing Sector: Job Demands-Resources Approach. Safety 2025, 11, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020029

Seo HJ, Rhee S-Y, Kim NK. A Study on the Factors Affecting Safety Behaviors and Safety Performance in the Manufacturing Sector: Job Demands-Resources Approach. Safety. 2025; 11(2):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Hyun Jeong, Seung-Yoon Rhee, and Nam Kyun Kim. 2025. "A Study on the Factors Affecting Safety Behaviors and Safety Performance in the Manufacturing Sector: Job Demands-Resources Approach" Safety 11, no. 2: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020029

APA StyleSeo, H. J., Rhee, S.-Y., & Kim, N. K. (2025). A Study on the Factors Affecting Safety Behaviors and Safety Performance in the Manufacturing Sector: Job Demands-Resources Approach. Safety, 11(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020029