Long-Term Prognostic Value in Nuclear Cardiology: Expert Scoring Combined with Automated Measurements vs. Angiographic Score

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Stress Testing

2.3. Angiographic Findings and Score

- -

- Normal study: 0;

- -

- One-vessel disease: 1;

- -

- Two-vessel disease: 2;

- -

- Three-vessel disease: 3.

2.4. SPECT MPI and Scintigraphic Findings

2.5. Follow-Up

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hansen, C.L. The prognosis for prognosis remains excellent. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2013, 20, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandrian, A.S.; Chae, S.C.; Heo, J.; Stanberry, C.D.; Wasserleben, V.; Cave, V. Independent and incremental prognostic value of exercise single-photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT) thallium imaging in coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993, 22, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Berman, D.S.; Lewin, H.C.; Cohen, I.; Friedman, J.D.; Germano, G.; Hachamovitch, R.; Shaw, L.J. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: Differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998, 97, 535–543. [Google Scholar]

- Hachamovitch, R.; Berman, D.S.; Kiat, H.; Cohen, I.; Cabico, J.A.; Friedman, J.; Diamond, G.A. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: Incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation 1996, 93, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.J.; Iskandrian, A.E. Prognostic value of gated myocardial perfusion SPECT. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2004, 11, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, G.; Valotassiou, V.; Tsougos, I.; Tzavara, C.; Psimadas, D.; Theodorou, E.; Ziaka, A.; Giannakou, S.; Ziangas, C.; Skoularigis, J.; et al. Automated Analysis vs. Expert reading in nuclear cardiology: Correlations with the angiographic score. Medicina 2022, 58, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelidis, G.; Giannakou, S.; Valotassiou, V.; Tsougos, I.; Tzavara, C.; Psimadas, D.; Theodorou, E.; Ziaka, A.; Ziangas, C.; Skoularigis, J.; et al. Long-term prognostic value of automated measurements in nuclear cardiology: Comparisons with expert scoring. Medicina 2023, 59, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, B.; Tägil, K.; Cuocolo, A.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Bardiés, M.; Bax, J.; Bengel, F.; Busemann Sokole, E.; Davies, G.; Dondi, M.; et al. EANM/ESC procedural guidelines for myocardial perfusion imaging in nuclear cardiology. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2005, 32, 855–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberne, H.J.; Acampa, W.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Ballinger, J.; Bengel, F.; De Bondt, P.; Buechel, R.R.; Cuocolo, A.; van Eck-Smit, B.L.F.; Flotats, A.; et al. EANM procedural guidelines for radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging with SPECT and SPECT/CT: 2015 revision. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 42, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, A.; Latus, K.A.; Davies, G.; Dhawan, R.T.; Eastick, S.; Jarritt, P.H.; Roussakis, G.; Young, M.C.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Bomanji, J.; et al. A comparison of three radionuclide myocardial perfusion tracers in clinical practice: The ROBUST study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2002, 29, 1608–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.V.; Cerqueira, M.D.; Weissman, N.J.; Dilsizian, V.; Jacobs, A.K.; Kaul, S.; Laskey, W.K.; Pennell, D.J.; Rumberger, J.A.; Ryan, T.; et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2002, 9, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgoulias, P.; Demakopoulos, N.; Orfanakis, A.; Xydis, K.; Xaplanteris, P.; Vardas, P.; Fezoulidis, I. Evaluation of abnormal heart-rate recovery after exercise testing in patients with diabetes mellitus: Correlation with myocardial SPECT and chronotropic parameters. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2007, 28, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germano, G. Quantitative measurements of myocardial perfusion and function from SPECT (and PET) studies depend on the method used to perform those measurements. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Carver, C.; Foley, J.R.; Fent, G.J.; Garg, P.; Ripley, D.P. Cardiovascular imaging techniques for the assessment of coronary artery disease. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2022, 83, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonino, P.A.; De Bruyne, B.; Pijls, N.H.; Siebert, U.; Ikeno, F.; van’t Veer, M.; Klauss, V.; Manoharan, G.; Engstrøm, T.; Oldroyd, K.G.; et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, D.J.; Hochman, J.S.; Reynolds, H.R.; Bangalore, S.; O’Brien, S.M.; Boden, W.E.; Chaitman, B.R.; Senior, R.; López-Sendón, J.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarins, C.K.; Taylor, C.A.; Min, J.K. Computed Fractional Flow Reserve (FFTCT) derived from coronary CT angiography. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2013, 6, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, T.M.; Prvulovich, E. Assessment of prognosis in chronic coronary artery disease. Heart 2004, 90, v10–v15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.D.; Askew, J.W.; Herrmann, J. Assessing clinical impact of myocardial perfusion studies: Ischemia or other prognostic indicators? Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2014, 16, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, T.; Kasama, S.; Sato, M.; Sano, H.; Ueda, T.; Sasaki, T.; Nakahara, T.; Higuchi, T.; Tsushima, Y.; Kurabayashi, M. A 2-year prospective study on the differences in prognostic factors for major adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and renal events between patients with mild and severe chronic kidney disease. Ann. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 7, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kawano, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Hase, H.; Joki, N.; Hatta, T.; Nishimura, S.; Moroi, M.; Nakagawa, S.; Kasai, T.; et al. Prognostic study of cardiac events in Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease using ECG-gated myocardial perfusion imaging: Final 3-year report of the J-ACCESS 3 study. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucerius, J.; Joe, A.Y.; Herder, E.; Brockmann, H.; Biermann, K.; Palmedo, H.; Tiemann, K.; Biersack, H.-J. Pathological 99mTc-sestamibi myocardial perfusion scintigraphy is independently associated with emerging cardiac events in elderly patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Acta Radiol. 2011, 52, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, C.; Çınaral, F.; Karagöz, A.; Bayram, Z.; Onal, S.C.; Candan, O.; Acar, R.D.; Cap, M.; Erdogan, E.; Hakgor, A.; et al. Comparison of automated quantification and semiquantitative visual analysis findings of IQ SPECT MPI with conventional coronary angiography in patients with stable angina. Turk Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2019, 47, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momose, Μ.; Nakajima, Κ.; Nishimura, Τ. Prognostic significance of stress myocardial gated SPECT among Japanese patients referred for coronary angiography: A study of data from the J-ACCESS database. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2009, 36, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; He, Z.X.; Shi, R.; Yang, M.; Gao, R.; Chen, J.; Fang, W. Long-term prognostic value of exercise 99mTc-MIBI SPET myocardial perfusion imaging in patients after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2004, 31, 655–662. [Google Scholar]

| Hard Cardiac Events | Soft Cardiac Events |

|---|---|

|

|

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Females | 144 (38.1) |

| Males | 234 (61.9) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.8 (9.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.5 (5.4) |

| Symptoms | 272 (72) |

| Angina | 94 (24.9) |

| Angina-like symptoms | 104 (27.5) |

| Dyspnea | 86 (22.8) |

| Palpitations | 74 (19.6) |

| Fatigue | 72 (19) |

| Number of risk factors, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| Smoking | 148 (39.2) |

| Hypertension | 282 (74.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 130 (34.4) |

| Lipid disorders | 300 (79.4) |

| Obesity | 158 (41.8) |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 152 (40.2) |

| Comorbidities | 86 (22.8) |

| Peripheral angiopathy | 22 (5.8) |

| Stroke | 28 (7.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 50 (13.2) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (SD) | 0.58 (0.05) |

| Coronary angiography | 378 (100) |

| Left main artery | 0 (0) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 128 (33.9) |

| Left circumflex artery | 86 (22.8) |

| Right coronary artery | 128 (33.9) |

| Angiographic Score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

| Cardioactive agents | 272 (72) |

| Bruce protocol | 154 (44) |

| Pharmacologic stress | 196 (56) |

| Hard events | 44 (11.6) |

| All-cause death | 24 (6.3) |

| Cardiovascular death | 14 (3.7) |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction (post-MPI) | 18 (4.8) |

| Soft events | 120 (31.7) |

| Stroke (post-MPI) | 20 (5.3) |

| Hospitalization due to cardiac disorder (post-MPI) | 104 (27.5) |

| Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (post-MPI) | 46 (12.2) |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting (post-MPI) | 8 (2.1) |

| Any cardiac event | 138 (36.5) |

| Method | Index | AUC | 95% CI | p | Optimal Cut-Off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any cardiac event | ECTb | SSS | 0.59 | 0.53–0.65 | 0.003 | 11.5 | 53.6 | 65.8 |

| SRS | 0.54 | 0.48–0.60 | 0.241 | - | - | - | ||

| SDS | 0.60 | 0.55–0.66 | 0.001 | 5.5 | 63.8 | 58.3 | ||

| MYO | SSS | 0.67 | 0.61–0.73 | <0.001 | 10.5 | 68.1 | 63.3 | |

| SRS | 0.65 | 0.59–0.71 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 69.6 | 53.3 | ||

| SDS | 0.60 | 0.54–0.66 | 0.001 | 4.5 | 62.3 | 54.2 | ||

| QPS | SSS | 0.65 | 0.6–0.71 | <0.001 | 6.5 | 66.7 | 59.2 | |

| SRS | 0.56 | 0.5–0.62 | 0.063 | - | - | - | ||

| SDS | 0.66 | 0.6–0.71 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 75.4 | 54.2 | ||

| Expert score | SSS | 0.88 | 0.84–0.91 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 89.9 | 75.8 | |

| SRS | 0.72 | 0.67–0.77 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 60.9 | 75.8 | ||

| SDS | 0.87 | 0.83–0.91 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 84.1 | 79.2 | ||

| Expert score–all indexes combined | 0.88 | 0.84–0.91 | <0.001 | |||||

| Angiographic score | 0.71 | 0.65–0.76 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 76.8 | 52.5 | ||

| Hard events | ECTb | SSS | 0.63 | 0.54–0.73 | 0.004 | 11.5 | 68.2 | 62.3 |

| SRS | 0.51 | 0.42–0.61 | 0.780 | - | - | - | ||

| SDS | 0.67 | 0.59–0.76 | <0.001 | 5.5 | 72.7 | 53.3 | ||

| MYO | SSS | 0.69 | 0.61–0.78 | <0.001 | 10.5 | 77.3 | 55.7 | |

| SRS | 0.67 | 0.59–0.74 | <0.001 | 5.5 | 68.2 | 58.1 | ||

| SDS | 0.65 | 0.56–0.74 | 0.001 | 6.5 | 54.5 | 69.5 | ||

| QPS | SSS | 0.66 | 0.59–0.74 | <0.001 | 7.5 | 77.3 | 59.3 | |

| SRS | 0.54 | 0.45–0.62 | 0.447 | - | - | - | ||

| SDS | 0.67 | 0.59–0.75 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 81.8 | 46.7 | ||

| Expert score | SSS | 0.81 | 0.74–0.88 | <0.001 | 6.5 | 86.4 | 69.5 | |

| SRS | 0.68 | 0.59–0.76 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 63.6 | 65.9 | ||

| SDS | 0.82 | 0.76–0.88 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 90.9 | 62.3 | ||

| Expert score—all indexes combined | 0.82 | 0.75–0.89 | <0.001 | |||||

| Angiographic score | 0.65 | 0.57–0.73 | 0.001 | 0.5 | 81.8 | 44.9 | ||

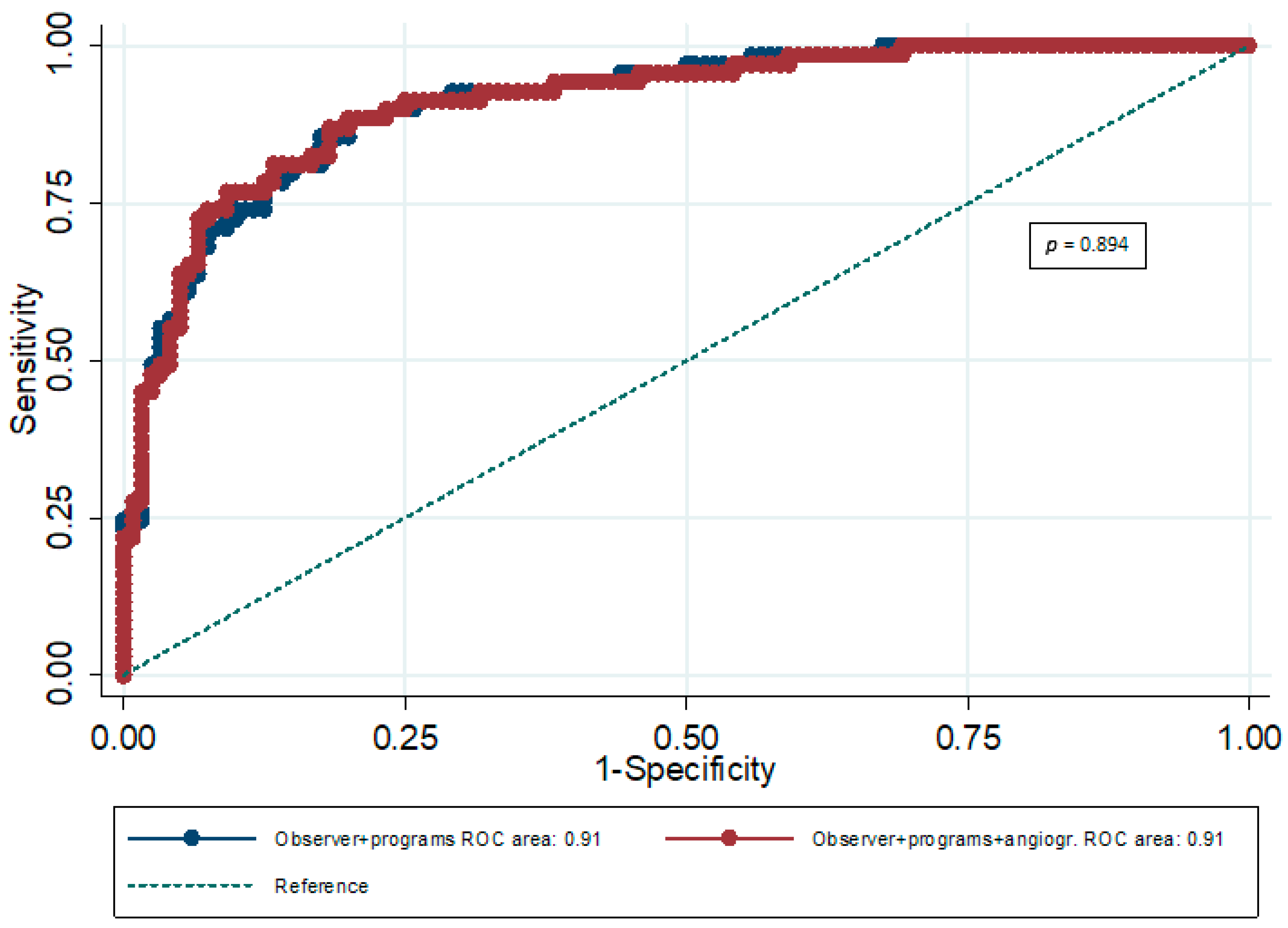

| AUC | 95% CI | p | P for Comparison Between AUCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES plus 3 software packages combined | 0.91 | 0.88–0.94 | <0.001 | 0.894 |

| ES plus 3 software packages combined plus AS | 0.91 | 0.88–0.94 | <0.001 |

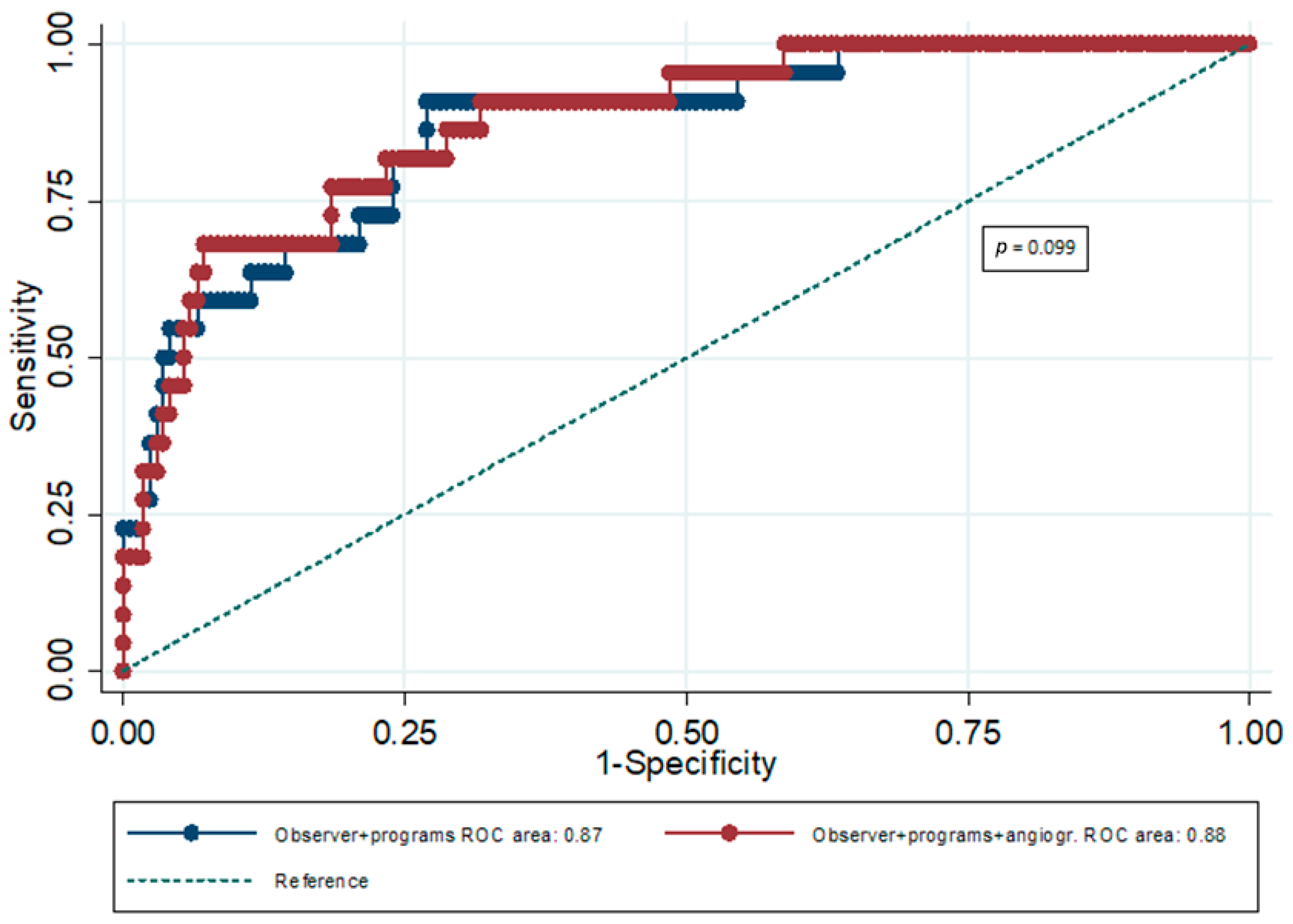

| AUC | 95% CI | p | p for Comparison Between AUCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES plus 3 software packages combined | 0.87 | 0.81–0.92 | <0.001 | 0.099 |

| ES plus 3 software packages combined plus AS | 0.88 | 0.82–0.93 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Angelidis, G.; Giannakou, S.; Valotassiou, V.; Panagiotidis, E.; Tsougos, I.; Tzavara, C.; Psimadas, D.; Theodorou, E.; Ziangas, C.; Skoularigis, J.; et al. Long-Term Prognostic Value in Nuclear Cardiology: Expert Scoring Combined with Automated Measurements vs. Angiographic Score. J. Imaging 2026, 12, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010006

Angelidis G, Giannakou S, Valotassiou V, Panagiotidis E, Tsougos I, Tzavara C, Psimadas D, Theodorou E, Ziangas C, Skoularigis J, et al. Long-Term Prognostic Value in Nuclear Cardiology: Expert Scoring Combined with Automated Measurements vs. Angiographic Score. Journal of Imaging. 2026; 12(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngelidis, George, Stavroula Giannakou, Varvara Valotassiou, Emmanouil Panagiotidis, Ioannis Tsougos, Chara Tzavara, Dimitrios Psimadas, Evdoxia Theodorou, Charalampos Ziangas, John Skoularigis, and et al. 2026. "Long-Term Prognostic Value in Nuclear Cardiology: Expert Scoring Combined with Automated Measurements vs. Angiographic Score" Journal of Imaging 12, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010006

APA StyleAngelidis, G., Giannakou, S., Valotassiou, V., Panagiotidis, E., Tsougos, I., Tzavara, C., Psimadas, D., Theodorou, E., Ziangas, C., Skoularigis, J., Triposkiadis, F., & Georgoulias, P. (2026). Long-Term Prognostic Value in Nuclear Cardiology: Expert Scoring Combined with Automated Measurements vs. Angiographic Score. Journal of Imaging, 12(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010006