A Hierarchical Multi-Resolution Self-Supervised Framework for High-Fidelity 3D Face Reconstruction Using Learnable Gabor-Aware Texture Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose to model multi-level geometric facial features in the hierarchical mode using the hierarchical multi-resolution framework based on self-supervised learning (HMR-Framework).

- A learnable Gabor-aware texture enhancement module can be proposed to enhance fine-scale detail reconstruction by a joint spatial-frequency decoupling. This module constitutes the first incorporation of a learnable Gabor-based convolutional layer into the 3D face reconstruction pipeline to enable adaptive learning of high-frequency detail parameters.

- Global and local Markov random field loss (GL-MRFLoss) and detail perception loss (DPLoss) are proposed to deliver the global–local perceptual guidance and to ensure the structural properties of fine-scale facial features.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Morphable Model-Based 3D Face Reconstruction (3DMM)

2.2. Gabor Filter

3. Proposed Frameworks

3.1. Overview

3.2. Large-Resolution Geometry Prior Reconstruction

3.3. Medium-Resolution Geometry Detail Reconstruction

3.4. Fine-Resolution Geometry Detail Reconstruction

3.4.1. Gabor-Aware Texture Enhancement

3.4.2. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

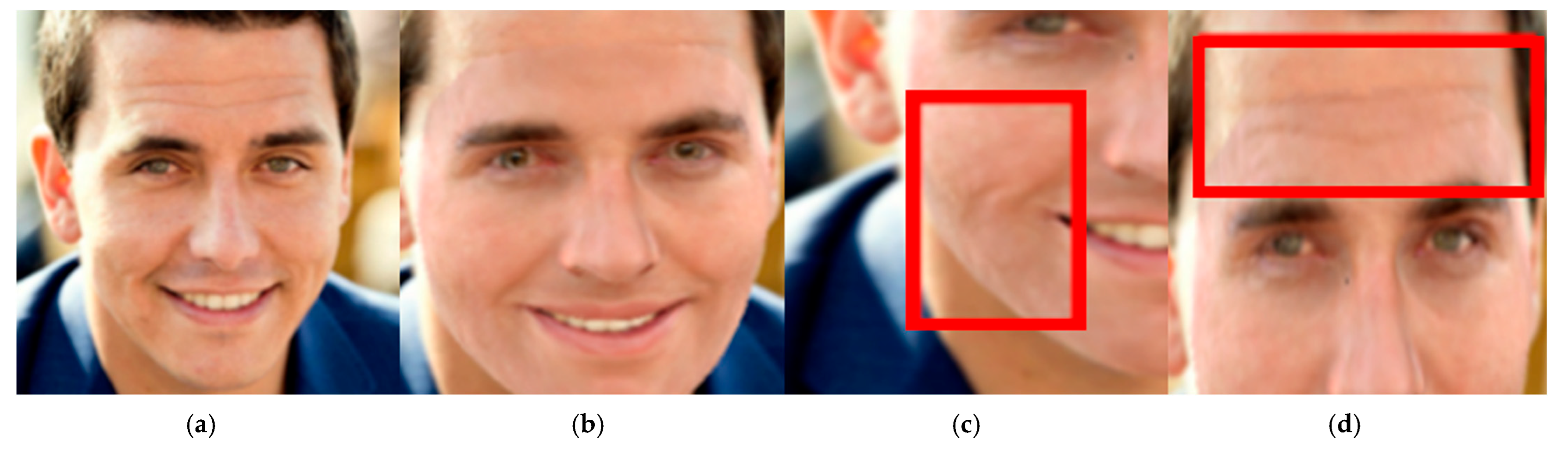

4.2. Qualitative Comparative Analysis

4.3. Comparison with Other Geometric Reconstruction Methods

4.4. Ablation Study

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Large-Pose Degradation

5.2. Computational Efficiency and Trade-Offs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, C. Enhancing 3D Face Recognition: Achieving Significant Gains by Leveraging Widely Available Face Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; An, B. S.; Lee, E.C. Comparative Analysis of AI-Based Facial Identification and Expression Recognition Using Upper and Lower Facial Regions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Zhou, M.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Ding, Y. LighterFace Model for Community Face Detection and Recognition. Information 2024, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fadel, N. Facial Recognition Algorithms: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, K.; Huang, Q.; Jiang, S.; Pan, Y. Human–Computer Interaction in Healthcare: A Bibliometric and Visual Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 15, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; An, B.S.; Lee, E.C. Exploring Technology Acceptance of Healthcare Devices: The Moderating Role of Device Type and Generation. Sensors 2024, 24, 7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Chang, J.; You, L.; Bian, S.; Kosk, R.; Maguire, G. Audio-Driven Facial Animation with Deep Learning: A Survey. Information 2024, 15, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Yan, F.; Zhao, G. Multimodal Feature-Guided Audio-Driven Emotional Facial Animation for Talking-Face Generation. Electronics 2025, 14, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanz, V.; Vetter, T. A morphable model for the synthesis of 3-D faces. In Seminal Graphics Papers: Pushing the Boundaries; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Chen, G.; Wong, K.-Y.K. Deep face video inpainting via UV mapping. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Cai, X.; Dong, J.; Yu, H. Real-time 3-D facial tracking via cascaded compositional learning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 3844–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, S.; Chen, D.; Jia, Y.; Tong, X. Accurate 3-D face reconstruction with weakly supervised learning: From single image to image set. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Bolkart, T.; Feng, H.; Black, M.J. Learning to regress 3-D face shape and expression from an image without 3-D supervision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 7763–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z.; Song, Y.; Ling, Y.; Bao, L. Self-supervised learning of detailed 3-D face reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 8696–8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Yang, H.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, M.; Wu, M.; Shen, Q.; Yang, R.; Cao, X. FaceScape: 3D Facial Dataset and Benchmark for Single-View 3D Face Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 14528–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Feng, H.; Black, M.J.; Bolkart, T. Learning an animatable detailed 3-D face model from in-the-wild images. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.-Y.; Wu, T.-C.; Phothong, W.; Wang, D.W.; Liao, C.-Y.; Lee, J.-Y. A High-Resolution Texture Mapping Technique for 3D Textured Model. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Chen, T.; Yin, J.; See, S.; Liu, J. Learning Gabor texture features for fine-grained recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 1621–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaraj, H.; Muneeswaran, V. Image compression using Haar discrete wavelet transform. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICDCS), Coimbatore, India, 5–6 March 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Dong, J.; Wang, F.-Y. Local and global perception generative adversarial network for facial expression synthesis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tao, X.; Qi, X.; Shen, X.; Jia, J. Image inpainting via generative multi-column convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, N.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Gao, C.; Wang, X. Deep Learning and Face Recognition: Face Recognition Approach Based on the DS-CDCN Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genova, K.; Cole, F.; Maschinot, A.; Sarna, A.; Vlasic, D.; Freeman, W.T. Unsupervised training for 3D morphable model regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 8377–8386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jang, S.; Bae, H.; Jeon, T.; Lee, S. Multitask Learning Strategy with Pseudo-Labeling: Face Recognition, Facial Landmark Detection, and Head Pose Estimation. Sensors 2024, 24, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Fang, L.; Hu, S. TED-Face: Texture-Enhanced Deep Face Reconstruction in the Wild. Sensors 2023, 23, 6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, P.; Shah, S.K.; Kakadiaris, I.A. End-to-end 3D face reconstruction with deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5908–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hao, Q.; Hu, J.; Pan, X.; Li, Z.; Cui, Z. 3D3M: 3D modulated morphable model for monocular face reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 2022, 25, 6642–6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Zhao, J.; Xie, M.; Jiang, Z.; Balamurugan, A.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; He, L.; Ma, Z.; Feng, J. 3D face reconstruction from a single image assisted by 2D face images in the wild. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 23, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, B.; Shen, J. Learning 3D face reconstruction from the cycle-consistency of dynamic faces. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 3663–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Chen, J.; Liang, C.; Xu, D.; Lin, C.-W. Expression-aware face reconstruction via a dual-stream network. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 23, 2998–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathallah, M.; Eletriby, S.; Alsabaan, M.; Ibrahem, M.I.; Farok, G. Advanced 3D Face Reconstruction from Single 2D Images Using Enhanced Adversarial Neural Networks and Graph Neural Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dib, A.; Ahn, J.; Thebault, C.; Gosselin, P.-H.; Chevallier, L. S2F2: Self-supervised high fidelity face reconstruction from monocular image. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG), Waikoloa Beach, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkov, N. Biologically motivated computationally intensive approaches to image pattern recognition. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 1995, 11, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Silva, J.S.; Bernardino, A. Fingerprint Recognition in Forensic Scenarios. Sensors 2024, 24, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, B.-S.; Toh, K.-A.; Teoh, A.B.J.; Lin, Z. An analytic Gabor feedforward network for single-sample and pose-invariant face recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 2791–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Cho, N.I. GF-CapsNet: Using Gabor jet and capsule networks for facial age, gender, and expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2019), Lille, France, 14–18 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Lee, S.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Koo, H.I.; Cho, N.I. Age and gender classification using wide convolutional neural network and Gabor filter. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Workshop on Advanced Image Technology (IWAIT), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 7–9 January 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-D.; Wang, X.-Q.; Meng, F.-J.; Hua, X.; Yan, Y.-J.; Li, Y.-Y.; Huang, J.; Jiang, X.-L. Gabor-CNN for object detection based on small samples. Defence Technol. 2020, 16, 1116–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.-N.; Zhong, G.; Gao, W.; Jiao, W.; Dong, J.; Shen, B.; Xia, D.; Xiang, W. Adaptive Gabor convolutional networks. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 124, 108495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tao, R.; Li, W.; Philips, W.; Liao, W. Fractional Gabor convolutional network for multisource remote sensing data classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.; Phung, S.L.; Chapple, P.B.; Bouzerdoum, A.; Ritz, C.H.; Tran, L.C. Deep Gabor neural network for automatic detection of mine-like objects in sonar imagery. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 94126–94139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhi, O.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep face recognition. In Proceedings of the BMVC 2015—British Machine Vision Conference, Swansea, UK, 7–10 September 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, P.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Efros, A.A. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shao, M.; Meng, D.; Zuo, W. Dual-pyramidal image inpainting with dynamic normalization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 5975–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Yin, H.; Luo, J. CAST: Learning both geometric and texture style transfers for effective caricature generation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 3347–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Chen, J. M2GF: Multi-Scale and Multi-Directional Gabor Filters for Image Edge Detection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Gao, Z.; Gong, H.; Li, S. DeFFace: Deep Face Recognition Unlocked by Illumination Attributes. Electronics 2024, 13, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Yu, T.; Ma, C.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. FaceVerse: A fine-grained and detail-controllable 3D face morphable model from a hybrid dataset. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 20333–20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneček, R.; Black, M.J.; Bolkart, T. EMOCA: Emotion-driven monocular face capture and animation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 8–24 June 2022; pp. 20311–20322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Ren, J.; Feng, M.; Cui, M.; Xie, X. A hierarchical representation network for accurate and detailed face reconstruction from in-the-wild images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Wang, Z.; Lu, M.; Wang, Q.; Qian, C.; Xu, F. Structure-aware editable morphable model for 3D facial detail animation and manipulation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | 0–5° | 5–30° | 30–60° | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | MNE | CD | MNE | CD | MNE | |

| DFDN | 3.702 | 0.091 | 3.307 | 0.092 | 7.313 | 0.130 |

| DF2Net | 2.953 | 0.122 | 2.441 | 0.129 | 6.625 | 0.159 |

| UDL | 2.353 | 0.092 | 3.287 | 0.094 | 4.294 | 0.109 |

| FaceScape | 2.842 | 0.087 | 3.178 | 0.094 | 4.045 | 0.109 |

| SADRNet | 3.268 | 0.114 | 3.617 | 0.074 | 6.488 | 0.120 |

| LAP | 4.238 | 0.093 | 4.524 | 0.082 | 6.010 | 0.100 |

| DECA | 2.913 | 0.081 | 2.664 | 0.080 | 2.912 | 0.093 |

| EMOCA | 2.709 | 0.090 | 2.714 | 0.099 | 2.943 | 0.101 |

| HRN | 2.529 | 0.086 | 2.612 | 0.115 | 2.15 | 0.080 |

| HMR-Framework | 2.225 | 0.087 | 2.488 | 0.083 | 3.343 | 0.103 |

| Methods | 0° | 30° | 60° | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | MNE | CD | MNE | CD | MNE | |

| DFDN | 5.350 | 0.138 | 8.390 | 0.165 | 29.540 | 0.350 |

| DF2Net | 5.600 | 0.190 | 9.550 | 0.250 | N/A | N/A |

| UDL | 2.760 | 0.115 | 6.680 | 0.154 | 7.040 | 0.209 |

| FaceScape | 4.010 | 0.113 | 6.090 | 0.149 | 5.850 | 0.182 |

| SADRNet | 5.320 | 0.136 | 8.840 | 0.171 | 8.860 | 0.185 |

| LAP | 5.340 | 0.140 | 9.260 | 0.186 | 10.880 | 0.244 |

| DECA | 4.130 | 0.116 | 5.180 | 0.125 | 5.250 | 0.134 |

| EMOCA | 3.090 | 0.108 | 4.060 | 0.117 | 5.380 | 0.124 |

| HRN | 2.950 | 0.106 | 4.700 | 0.118 | 5.290 | 0.118 |

| HMR-Framework | 2.660 | 0.112 | 6.290 | 0.133 | 6.040 | 0.188 |

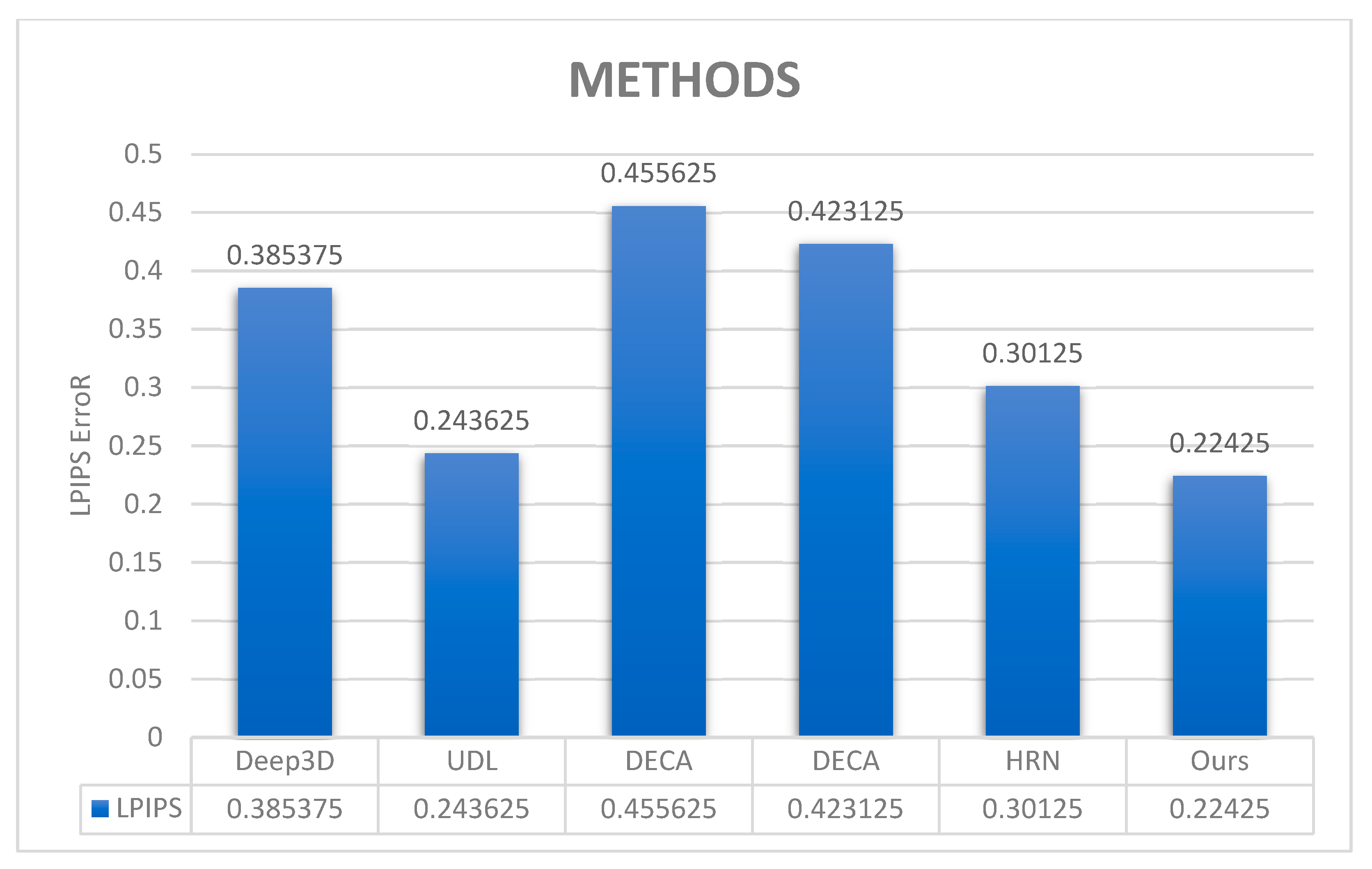

| Methods | Deep3D | UDL | DECA | DECA | HRN | HMR-Framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPIPS | 0.385375 | 0.243625 | 0.455625 | 0.423125 | 0.30125 | 0.22425 |

| Base Model | MulHi | Gabor | LPIPS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| √ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | 0.1037 |

| √ | √ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | 0.0944 |

| √ | √ | √ | ☐ | ☐ | 0.0941 |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | ☐ | 0.0934 |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.0921 |

| Convolution Kernel Size | Number of Gabor Filters | LPIPS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0941 | |||

| 0.0943 | |||

| 0.0938 | |||

| 0.0934 | |||

| ⇨ | 0.0921 | ||

| 0.0925 | |||

| 0.0919 | |||

| 0.0922 | |||

| Methods | UDL | HRN | HMR-Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Times (s) | 5.3808 | 5.8664 | 6.0192 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mareo, P.; Fooprateepsiri, R. A Hierarchical Multi-Resolution Self-Supervised Framework for High-Fidelity 3D Face Reconstruction Using Learnable Gabor-Aware Texture Modeling. J. Imaging 2026, 12, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010026

Mareo P, Fooprateepsiri R. A Hierarchical Multi-Resolution Self-Supervised Framework for High-Fidelity 3D Face Reconstruction Using Learnable Gabor-Aware Texture Modeling. Journal of Imaging. 2026; 12(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleMareo, Pichet, and Rerkchai Fooprateepsiri. 2026. "A Hierarchical Multi-Resolution Self-Supervised Framework for High-Fidelity 3D Face Reconstruction Using Learnable Gabor-Aware Texture Modeling" Journal of Imaging 12, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010026

APA StyleMareo, P., & Fooprateepsiri, R. (2026). A Hierarchical Multi-Resolution Self-Supervised Framework for High-Fidelity 3D Face Reconstruction Using Learnable Gabor-Aware Texture Modeling. Journal of Imaging, 12(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010026