LLM-Based Pose Normalization and Multimodal Fusion for Facial Expression Recognition in Extreme Poses

Abstract

1. Introduction

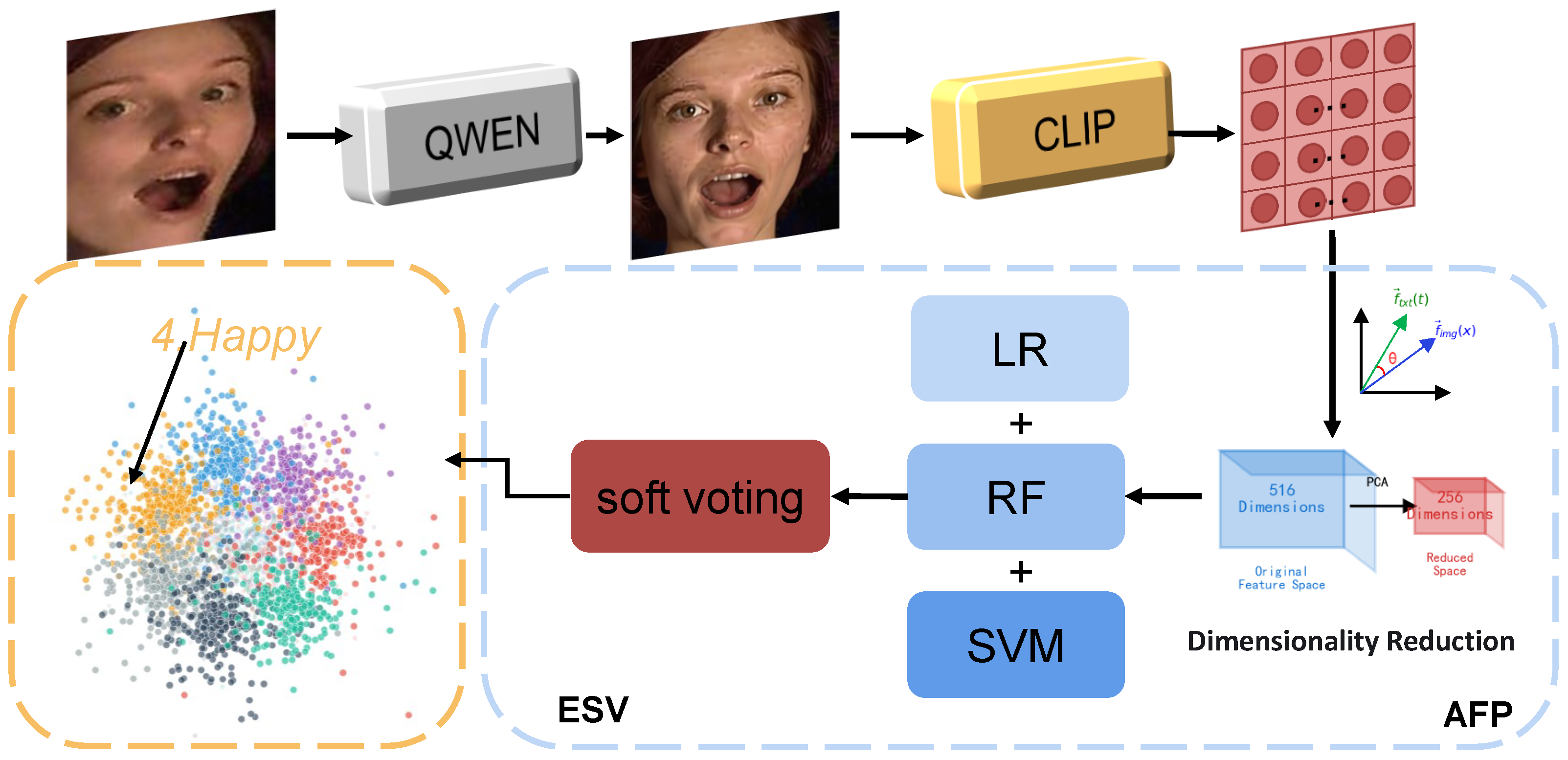

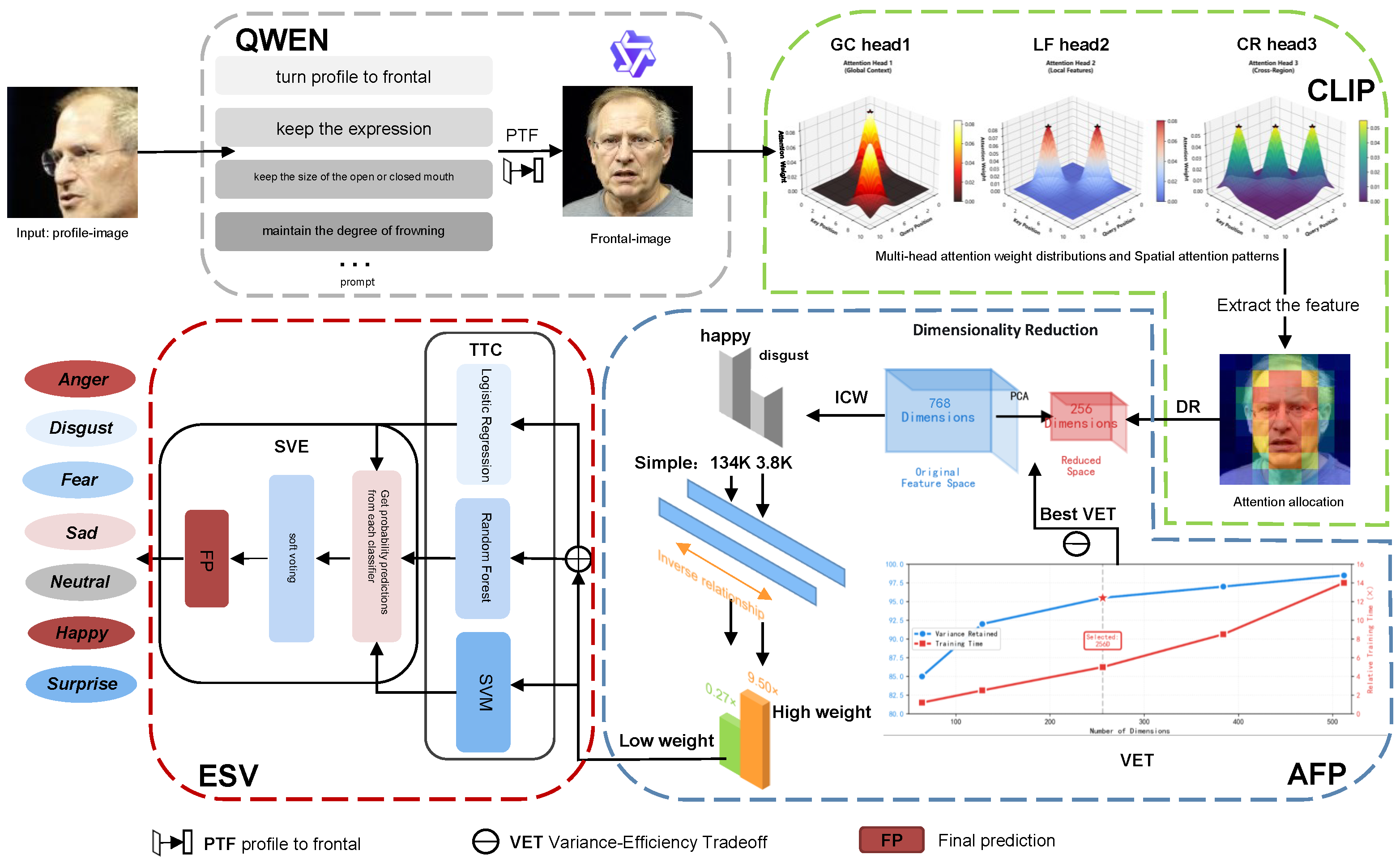

- We leverage the powerful visual understanding and generation capabilities of the Qwen-Image-Edit large model (https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen-Image-Edit accessed on 25 December 2025) to achieve high-quality profile-to-frontal transformation. Compared to traditional GAN methods, large models possess stronger prior knowledge and generation capability, enabling more accurate inference of expression details in occluded regions and generating more natural frontal face images that better conform to expression semantics.

- We introduce the CLIP model to map expression visual features into semantic space through “vision-text” alignment learning. This cross-modal learning not only enhances the interpretability of expression features but also improves the model’s generalization capability for unseen expression categories. We design expression-related text prompts (such as “a happy face,” “an angry face”) to guide CLIP in extracting discriminative expression features.

- We conducted extensive validation on three real-world facial expression recognition (FER) datasets and several FER-specific datasets under different conditions, achieving state-of-the-art performance improvements. For example, we achieved a 1.45% improvement on AffectNet and a 1.14% improvement on ExpW.

2. Related Work

2.1. Facial Expression Recognition (FER)

2.2. Profile Expression Recognition

2.3. Multimodal Model Image Generation

2.4. CLIP-Related Methods

3. Method

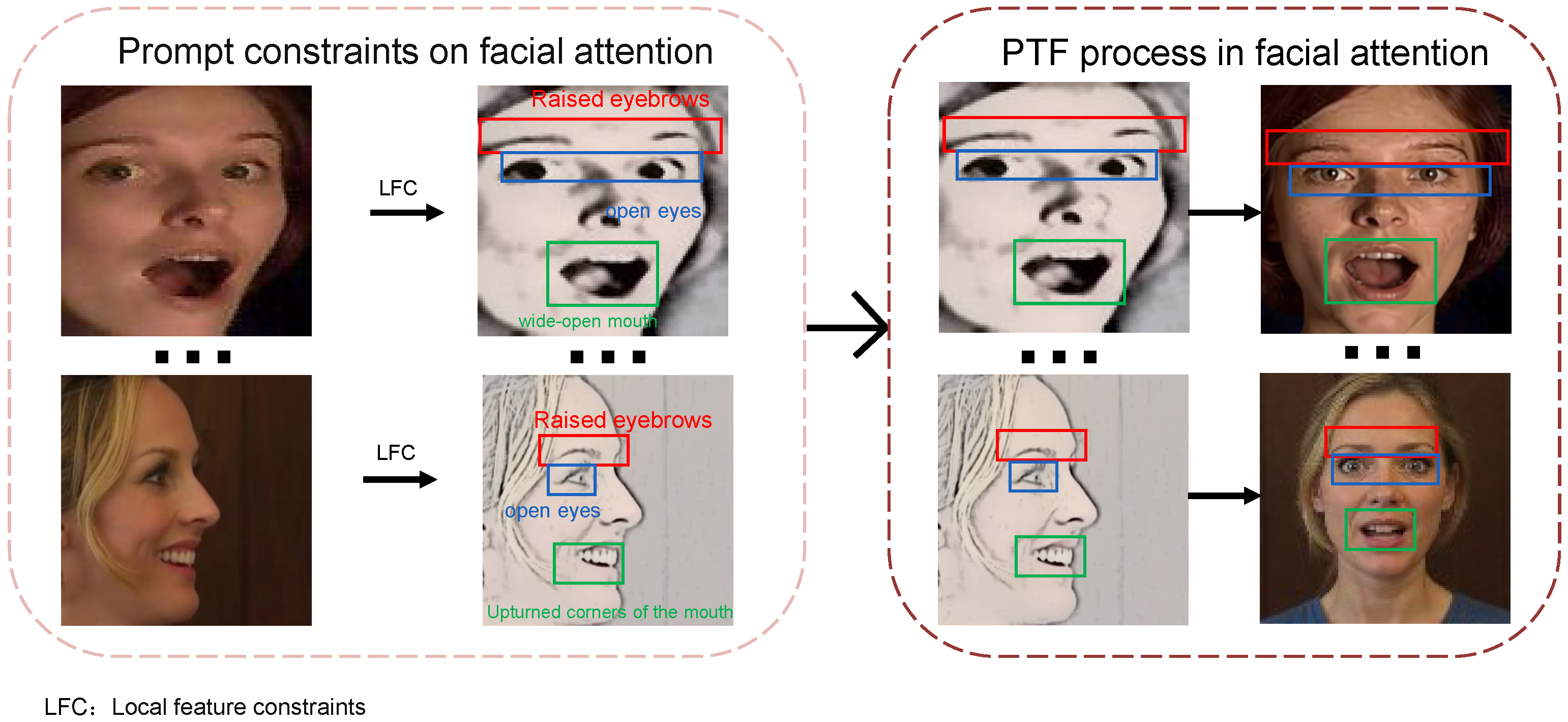

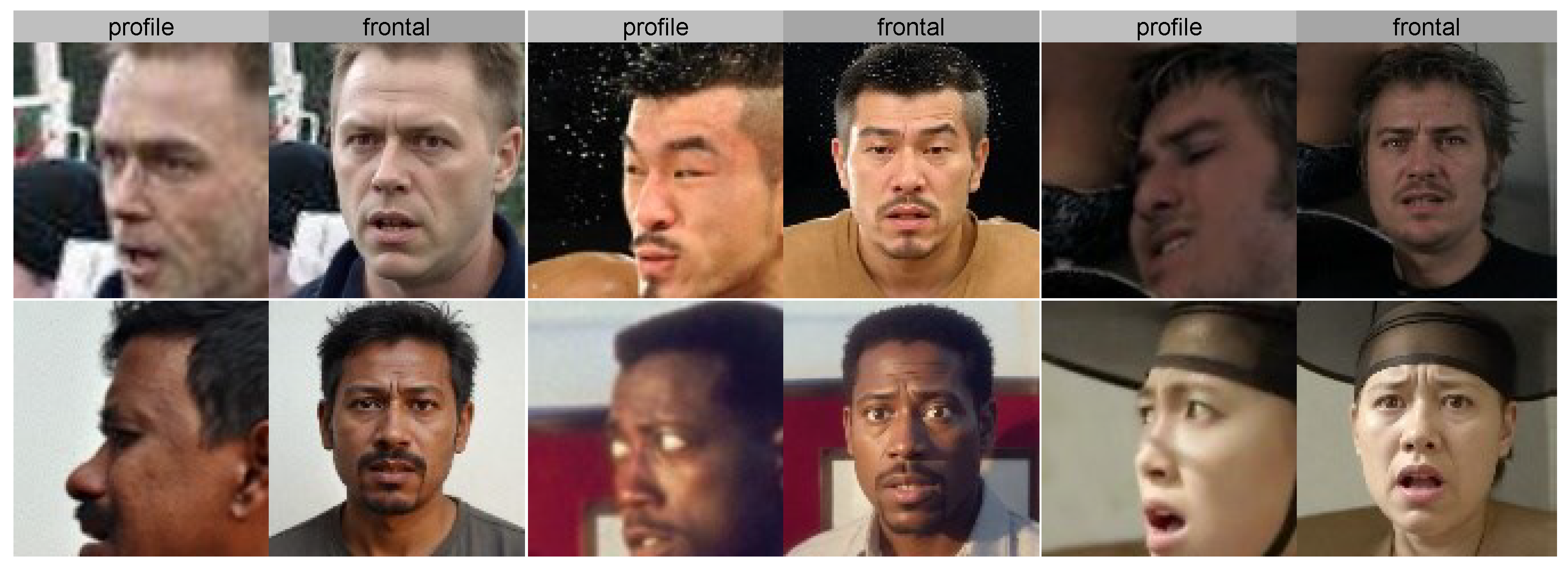

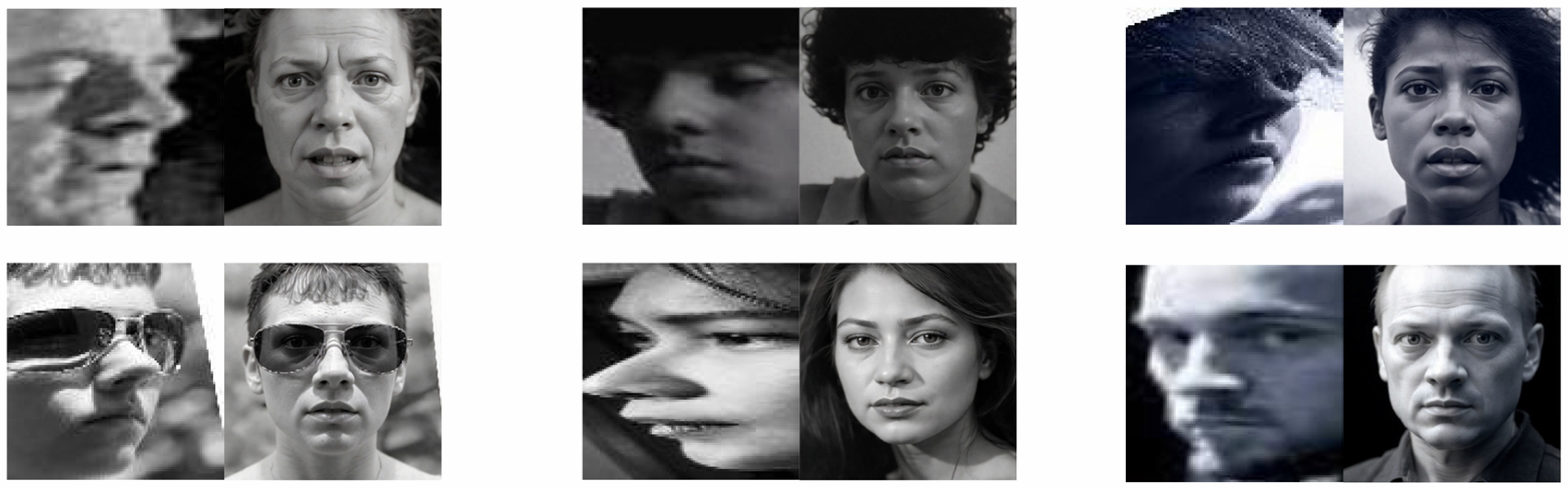

3.1. Profile-to-Frontal Normalization Module

- Prompt Template:

- Turn profile to frontal,

- keep the expression unchanged,

- keep the size of the open or closed mouth,

- maintain the degree of frowning,

- keep the size of the open or closed eyes,

- preserve facial identity.

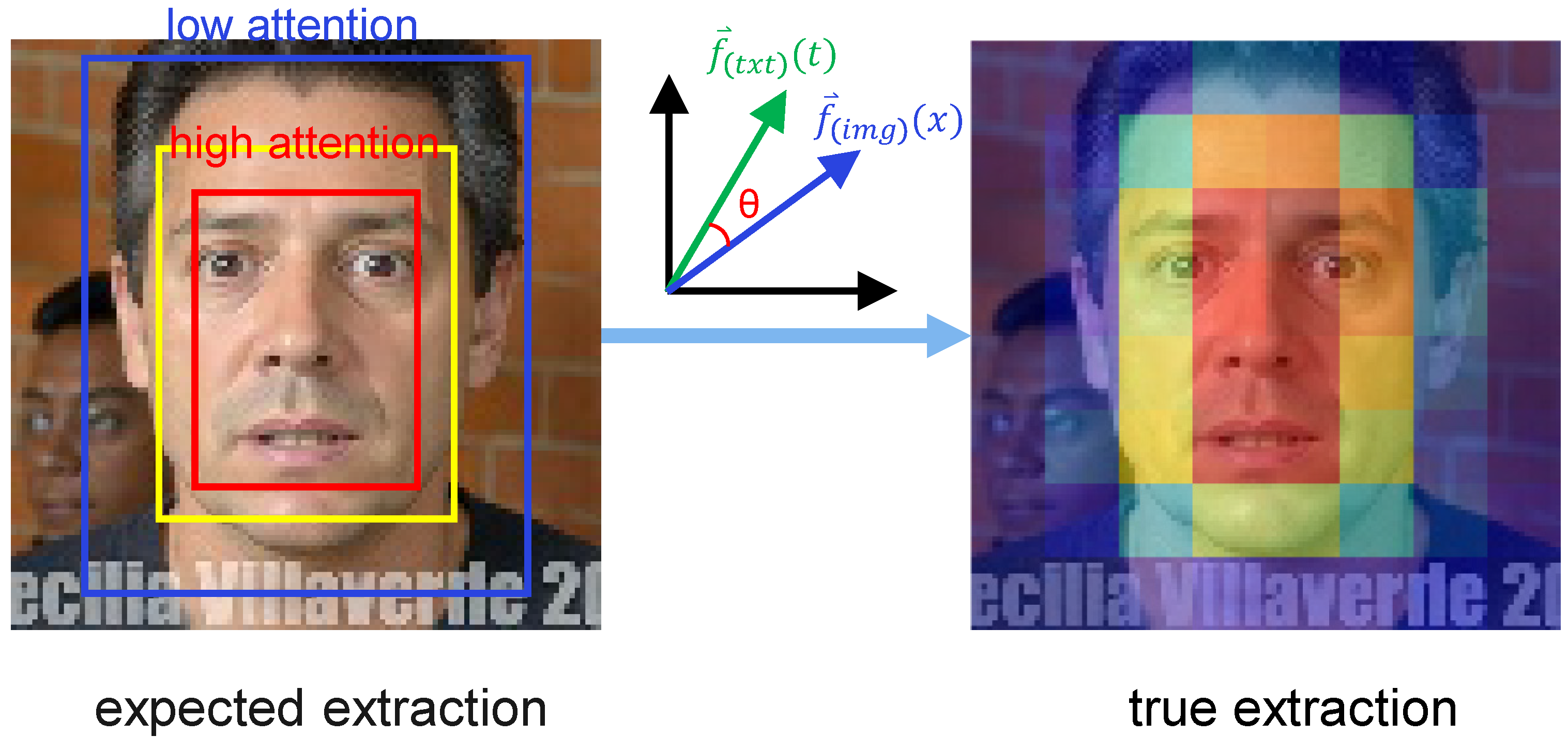

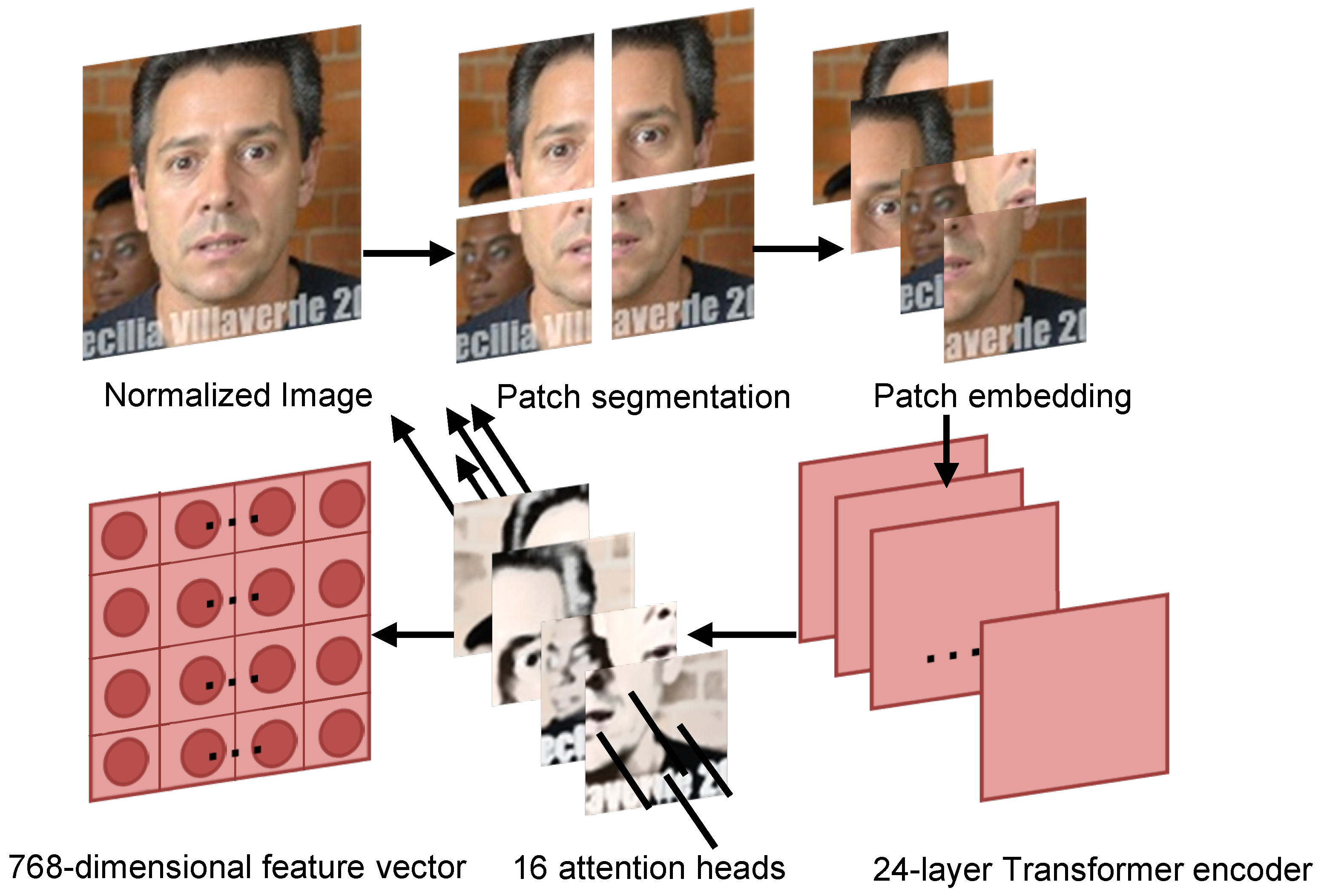

3.2. CLIP-Based Deep Feature Extraction Module

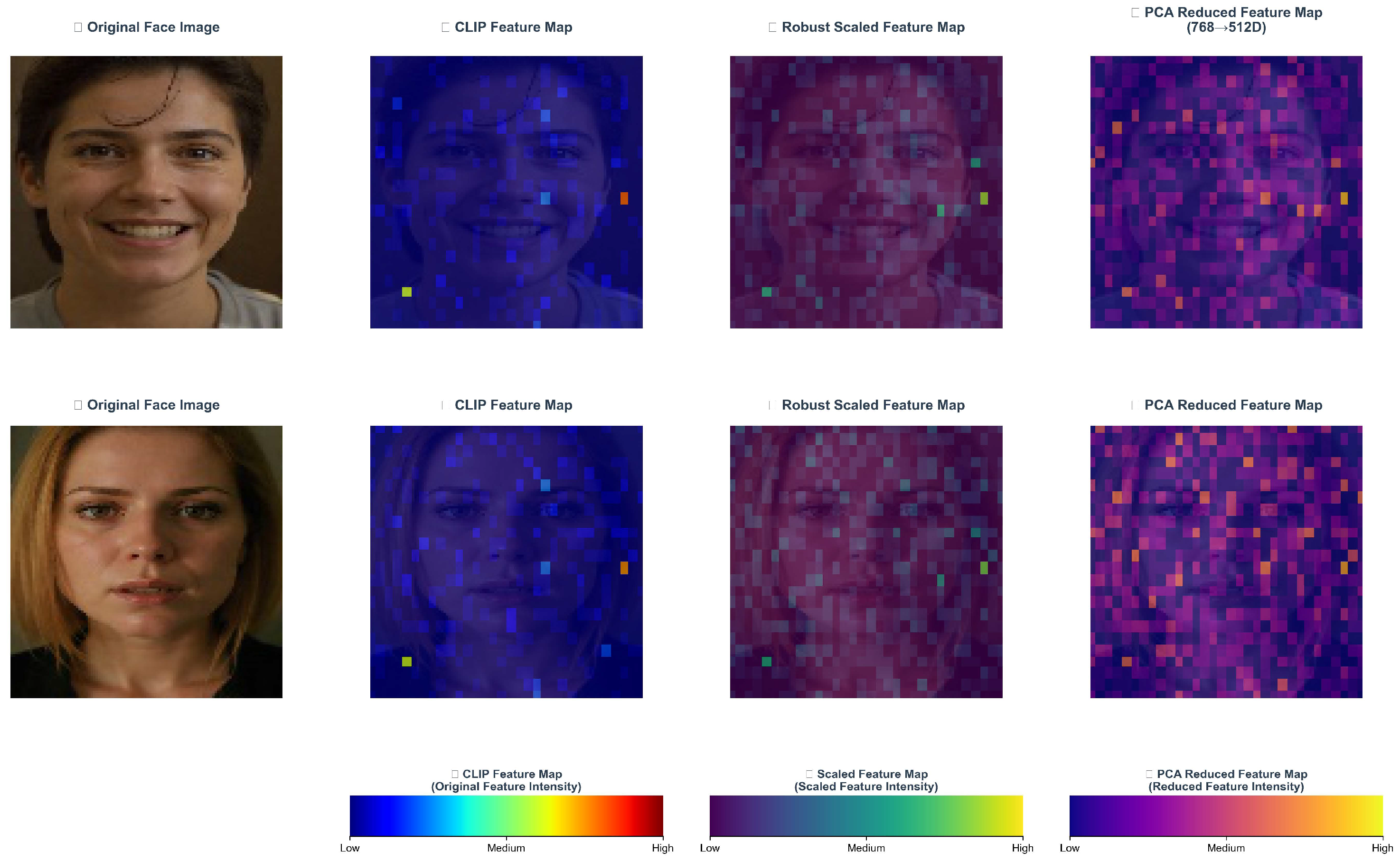

3.3. Adaptive Feature Preprocessing, AFP

3.4. Ensemble Soft Voting Classification Module (ESV)

3.5. Availability and Version Control

4. Experiment

4.1. FER In-the-Wild Datasets

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Comparison with Existing Methods

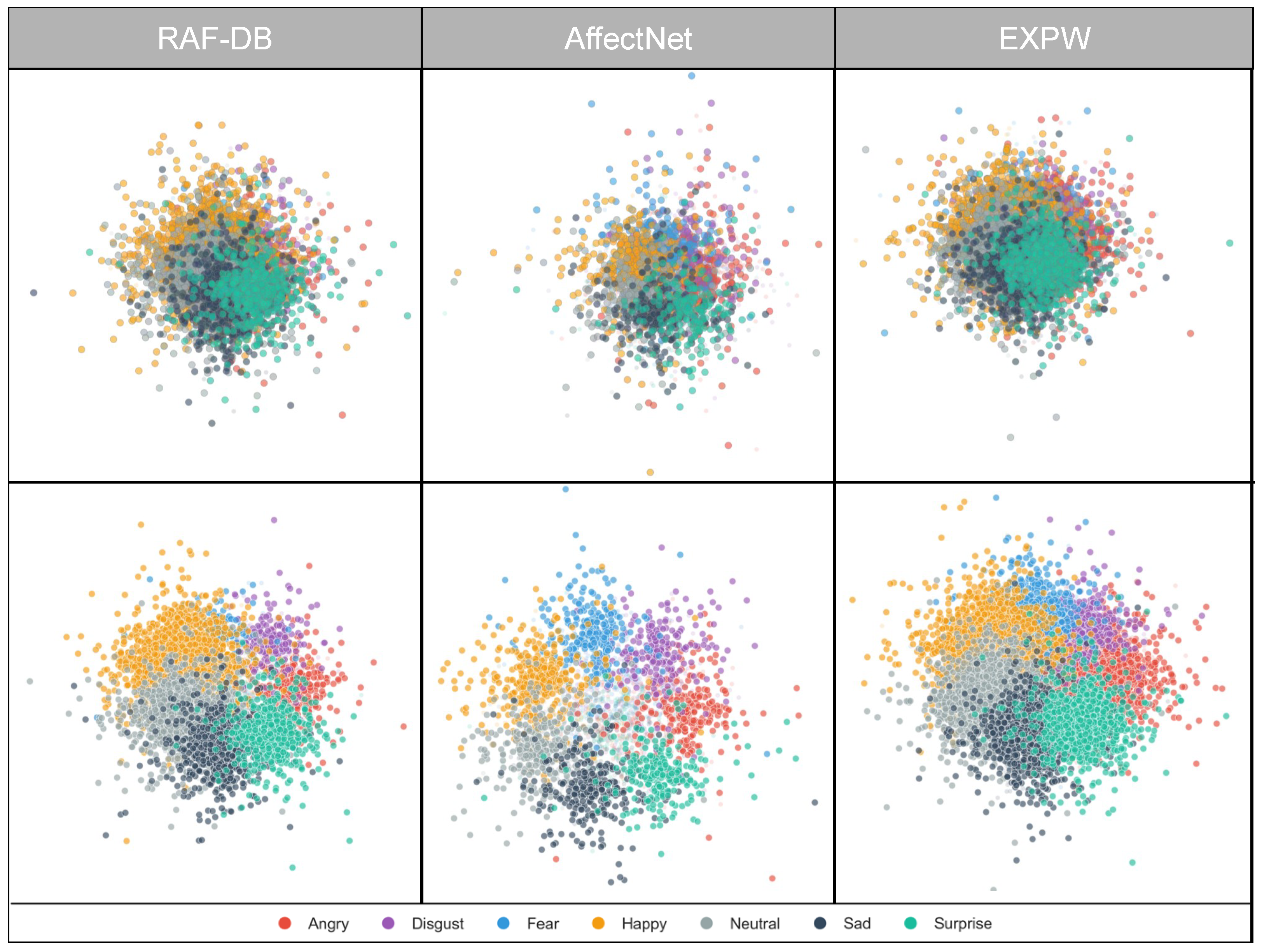

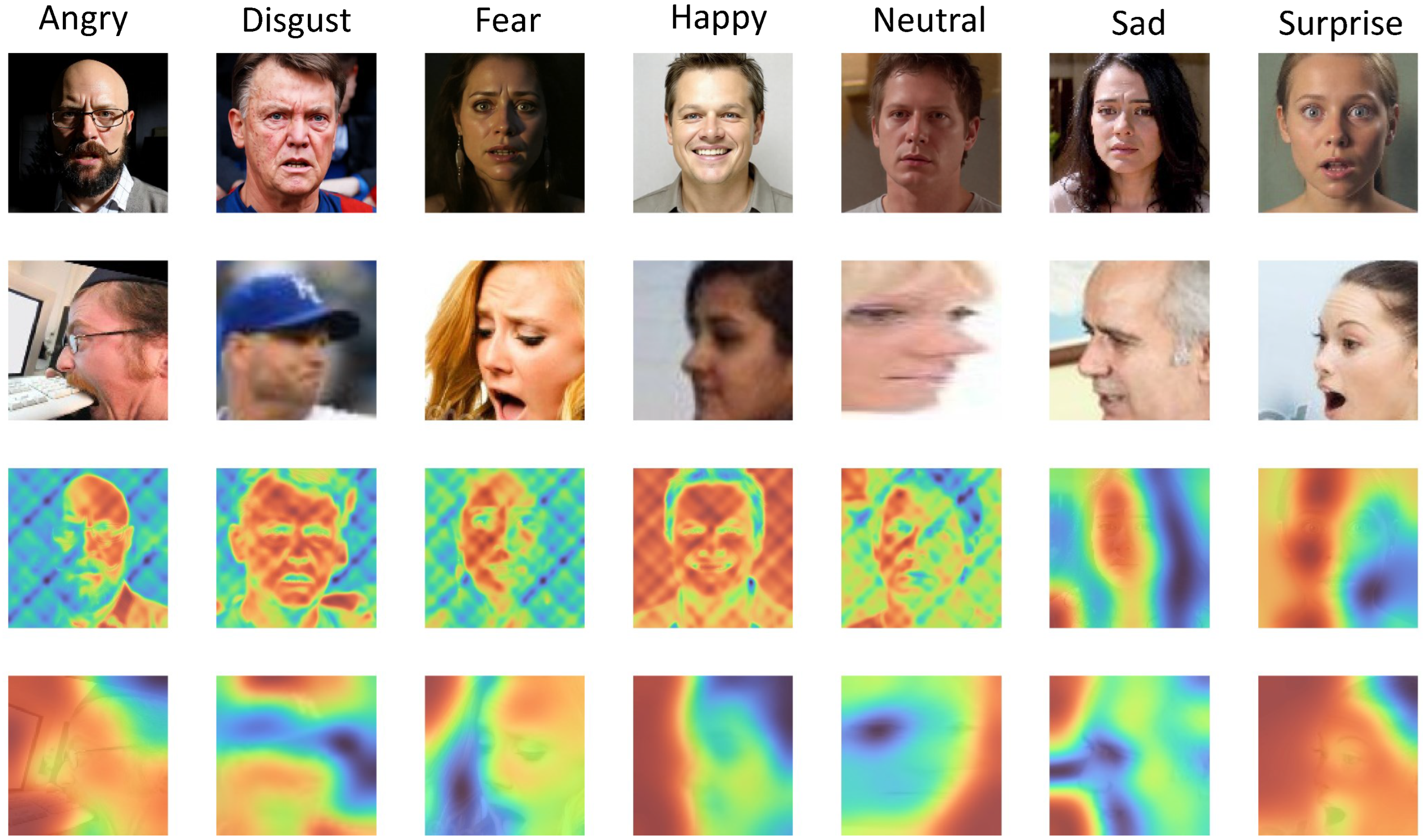

4.4. Feature Space and Decision Boundary Analysis

4.5. Ablation Studies

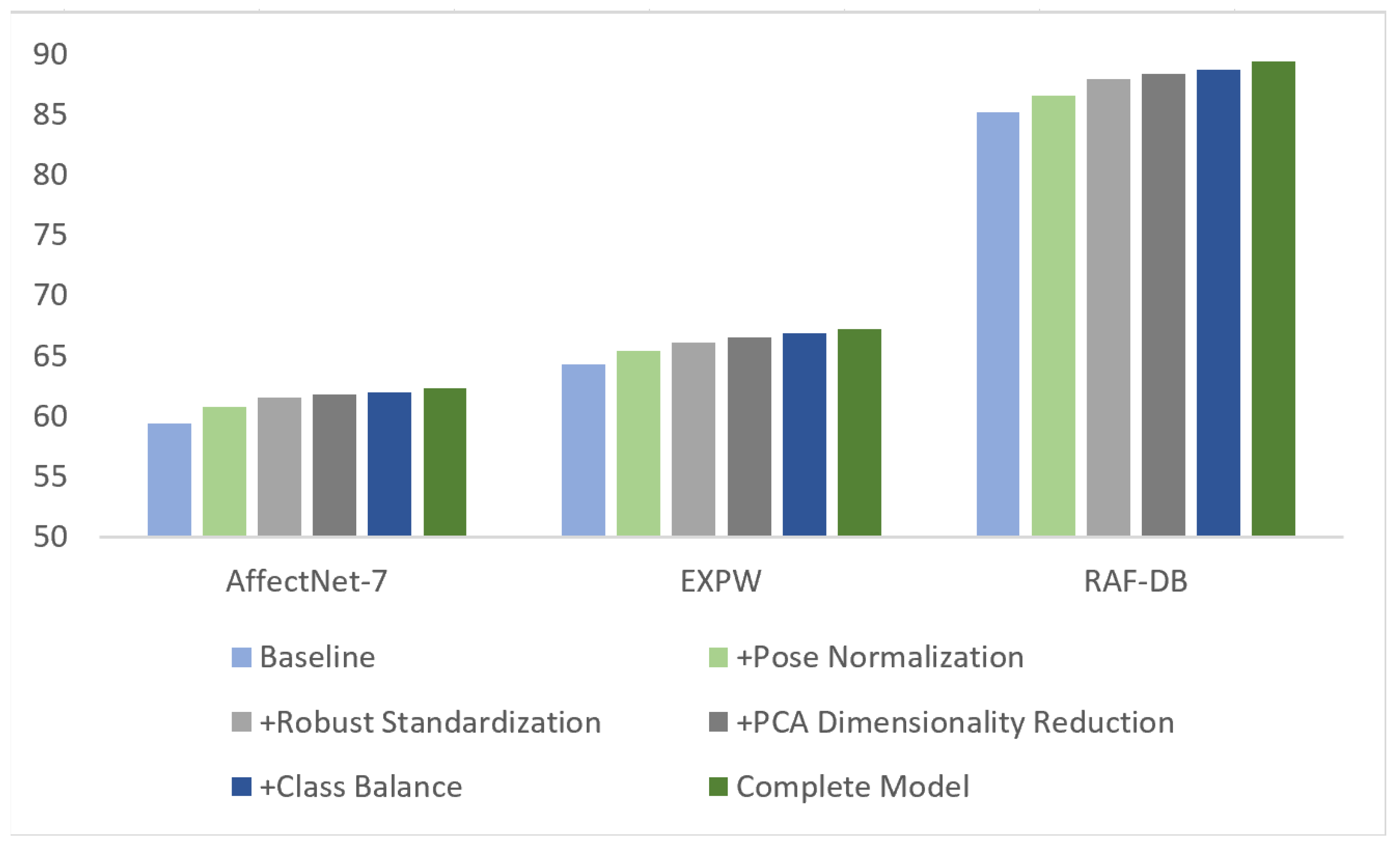

4.5.1. Module-Level Compositional Ablation

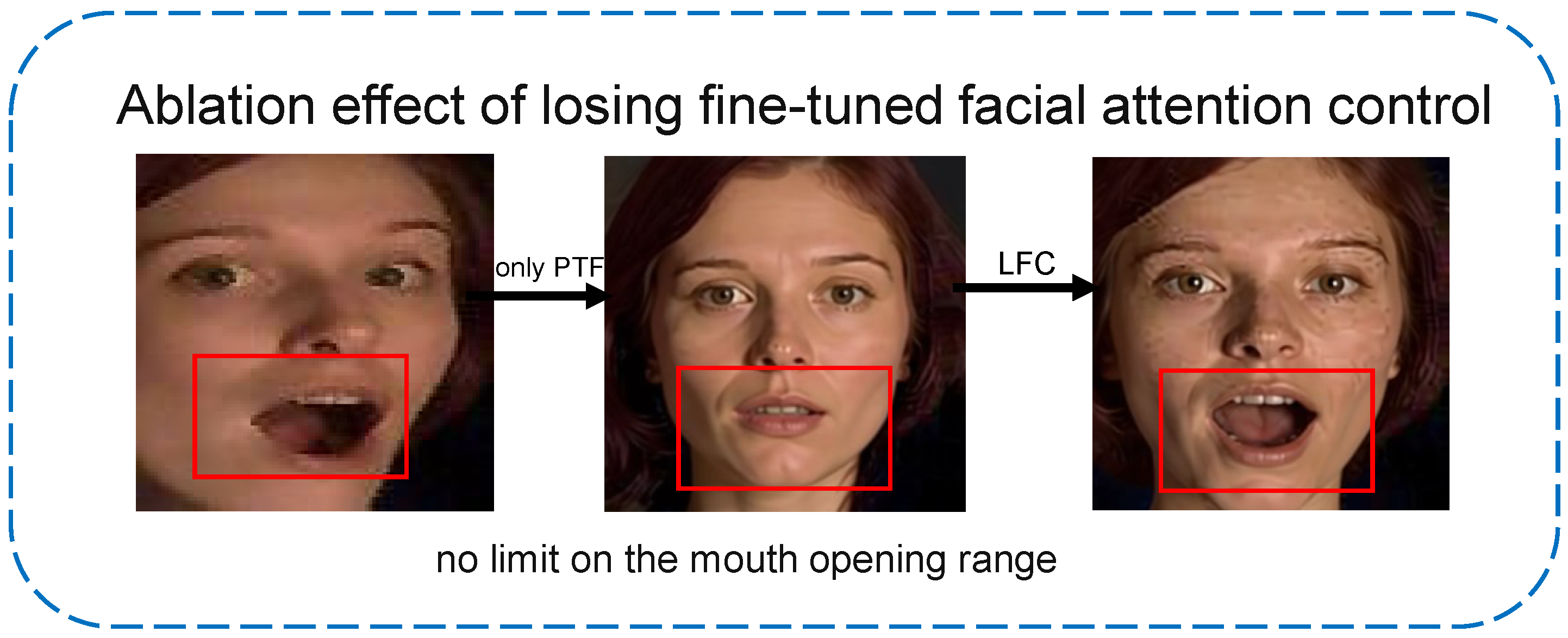

4.5.2. Ablation of Core Components

4.5.3. Comparison of Feature Extractors

4.5.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameter Settings

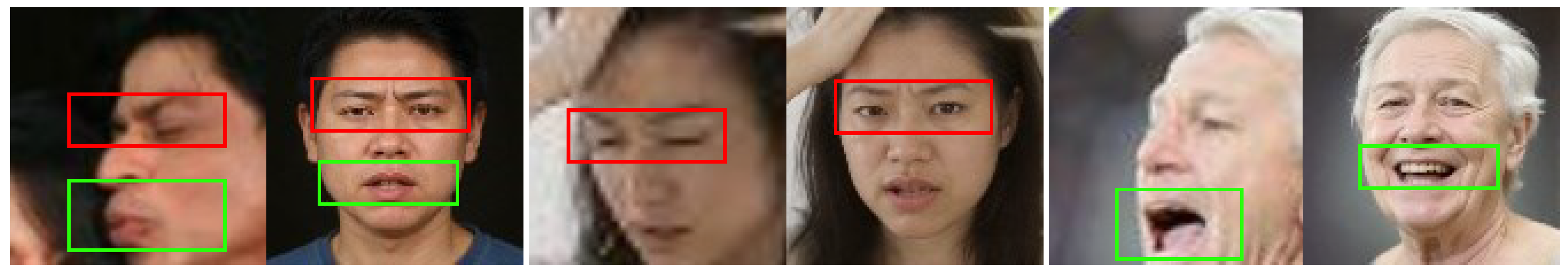

4.5.5. Effectiveness of Pose Normalization

4.5.6. Cross-Dataset Generalization Evaluation

4.5.7. Complexity and Efficiency Analysis

4.5.8. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Lu, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. Facial expression recognition in the wild using multi-level features and attention mechanisms. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2020, 14, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhao, N. A Facial Expression Recognition Algorithm based on CNN and LBP Feature. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020; Volume 1, pp. 2304–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, H. FACEMUG: A Multimodal Generative and Fusion Framework for Local Facial Editing. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 5130–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Sun, B.; Li, S. Facial expression recognition with visual transformers and attentional selective fusion. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 14, 1236–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shen, H.T. Region attention enhanced unsupervised cross-domain facial emotion recognition. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 35, 4190–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowrishankar, J.; Deepak, S.; Srivastava, M. Countering the Rise of AI-Generated Content with Innovative Detection Strategies and Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Computing Research on Science Engineering and Technology (ACROSET), Indore, India, 27–28 September 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, H.; Zhou, K.; Xu, W.; Yu, X. Text-Guided 3D Face Synthesis—From Generation to Editing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 1260–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Shu, Z. Design of Facial Expression Recognition Algorithm Based on CNN Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Power, Electronics and Computer Applications (ICPECA), Shenyang, China, 29–31 January 2023; pp. 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Wang, K.; Yamauchi, T. Face Expression Recognition With Vision Transformer and Local Mutual Information Maximization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 169263–169276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Facial Expression Recognition Using Multi-Branch Attention Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 1244–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Hu, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, J.; Shen, Q.; Mei, T. Dive into ambiguity: Latent distribution mining and pairwise uncertainty estimation for facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 6248–6257. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, N.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, X. Unconstrained Facial Expression Recognition with No-Reference De-Elements Learning. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2023, 15, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Deng, W. Relative uncertainty learning for facial expression recognition. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 17616–17627. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L.P.; Abdelkawy, H.; Othmani, A. Emomamba: Advancing Dynamic Facial Expression Recognition with Visual and Textual Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Anchorage, AK, USA, 14–17 September 2025; pp. 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Meng, Z.; Khan, A.S.; Li, Z.; O’Reilly, J.; Tong, Y. Probabilistic attribute tree structured convolutional neural networks for facial expression recognition in the wild. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022, 14, 1927–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Pu, T.; Wu, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, L.; Lin, L. Cross-domain facial expression recognition: A unified evaluation benchmark and adversarial graph learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 9887–9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Jia, G.; Jiang, N.; Wu, H.; Yang, J. Ease: Robust facial expression recognition via emotion ambiguity-sensitive cooperative networks. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 218–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Sun, B.; Li, S. Transformer-augmented network with online label correction for facial expression recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2023, 15, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Hirota, K.; Dai, Y.; Jia, Z.; Shao, S.; She, J. Learning Sequential Variation Information for Dynamic Facial Expression Recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 9946–9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dordinejad, G.G.; Çevikalp, H. Face Frontalization for Image Set Based Face Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU), Safranbolu, Turkey, 15–18 May 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhanov, N.; Amirgaliyev, B.; Islamgozhayev, T.; Yedilkhan, D. Federated Self-Supervised Few-Shot Face Recognition. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Mo, R.; Yan, Y.; Chen, S.; Xue, J.H.; Wang, H. Adaptive Deep Disturbance-Disentangled Learning for Facial Expression Recognition. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S. Learning deep global multi-scale and local attention features for facial expression recognition in the wild. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 6544–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezerceli, Ö.; Eskil, M.T. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Algorithm Based Facial Emotion Recognition (FER) System for FER-2013 Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), Male, Maldives, 16–18 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Meila, M., Zhang, T., Eds.; PMLR—Proceedings of Machine Learning Research: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021; Volume 139, pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Gong, W.; Xiao, R.; Zhou, Z. Face Frontalization Method with 3D Technology and a Side-Face-Alignment Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 12th International Conference on Information, Communication and Networks (ICICN), Guilin, China, 21–24 August 2024; pp. 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Liang, R.; Shi, W. A Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network for Real-Time Facial Expression Detection. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 5573–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lin, J.; Chen, T. Learning consistent global-local representation for cross-domain facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–25 August 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 2489–2495. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, H.; Raie, A.A. HistNet: Histogram-based convolutional neural network with Chi-squared deep metric learning for facial expression recognition. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Facial expression recognition with inconsistently annotated datasets. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 222–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Gao, K.; Yan, K.; Yin, S.; Bai, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Qwen-Image Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cai, H.; Lin, Q.; Li, X.; Xiao, H. Adaptive multilayer perceptual attention network for facial expression recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6253–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wen, G.; Li, H.; Chen, R.; Li, C. Multi-relations aware network for in-the-wild facial expression recognition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 3848–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, E.; Appati, J.K.; Okae, P. Robust facial expression recognition system in higher poses. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2022, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kauttonen, J.; Zhao, G. Uncertain facial expression recognition via multi-task assisted correction. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 2531–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, F. Robust lightweight facial expression recognition network with label distribution training. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 19–21 May 2021; Volume 35, pp. 3510–3519. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Ren, F. Toward facial expression recognition in the wild via noise-tolerant network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 2033–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Cao, Z.; Wang, J.; Jordan, M.I. Conditional adversarial domain adaptation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, J.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Occlusion aware facial expression recognition using CNN with attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 28, 2439–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Batra, T.; Baig, M.H.; Ulbricht, D. Sliced wasserstein discrepancy for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 10285–10295. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Xu, M.; Xu, C. Weakly-supervised facial expression recognition in the wild with noisy data. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 24, 1800–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, X.; Yang, J.; Meng, D.; Qiao, Y. Region attention networks for pose and occlusion robust facial expression recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 4057–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, P.; Loy, C.C.; Tang, X. From Facial Expression Recognition to Interpersonal Relation Prediction. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2018, 126, 550–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, X.; Yang, J.; Lu, S.; Qiao, Y. Suppressing Uncertainties for Large-Scale Facial Expression Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Li, G.; Yang, J.; Lin, L. Larger norm more transferable: An adaptive feature norm approach for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019; pp. 1426–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J.; Wu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S.; Pu, X.; Ren, Y. Self-paced label distribution learning for in-the-wild facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisboa, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Jin, X. VaBTFER: An Effective Variant Binary Transformer for Facial Expression Recognition. Sensors 2024, 24, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S. ViLBERT: Pretraining Task-Agnostic Visiolinguistic Representations for Vision-and-Language Tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Wallach, H., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Method | Accuracy | Database | Method | Accuracy | Database | Method | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >RAF-DB | EfficientFace [36] | 88.36% | AffectNet | IPA2LT [37] | 55.11% | EXPW | CADA [38] | 59.40% |

| MA-Net [23] | 88.40% | gACNN [39] | 58.78% | ICID [40] | 60.04% | |||

| PAT-ResNet-101 [15] | 88.43% | SPWFA_SE [1] | 59.23% | SWD [16] | 60.64% | |||

| WSFER [41] | 88.89% | RAN [42] | 59.50% | HOG+SVM [43] | 60.66% | |||

| RUL [13] | 88.98% | SCN [44] | 60.23% | SAFN [45] | 61.40% | |||

| SPLDL [46] | 89.08% | FENN [37] | 60.83% | JUMBOT [23] | 63.69% | |||

| TAN [18] | 89.12% | DENet [12] | 60.94% | RANDA [5] | 63.87% | |||

| HistNet [29] | 89.24% | RUL [13] | 61.43% | AGRA [16] | 63.94% | |||

| AMP-Net [32] | 89.25% | MTAC [35] | 61.58% | CGLRL [28] | 64.87% | |||

| ADDL [22] | 89.34% | EASE [34] | 61.82% | Baseline DCN [43] | 65.06% | |||

| DMUE [11] | 89.42% | MRAN [33] | 62.48% | LPL [39] | 66.90% | |||

| QC-FER (our) | 89.39% | QC-FER (our) | 62.66% | QC-FER (our) | 67.17% |

| Emotion | RAF-DB P | RAF-DB R | RAF-DB F1 | AffectNet-7 P | AffectNet-7 R | AffectNet-7 F1 | ExpW P | ExpW R | ExpW F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angry | 80.6 | 86.7 | 83.5 | 64.2 | 52.0 | 57.5 | 65.0 | 66.4 | 65.7 |

| Disgust | 63.0 | 74.2 | 68.1 | 48.6 | 45.0 | 46.7 | 48.0 | 52.7 | 50.2 |

| Fear | 58.5 | 83.1 | 68.7 | 58.3 | 60.0 | 59.1 | 44.0 | 59.3 | 50.5 |

| Happy | 95.1 | 95.2 | 95.2 | 71.0 | 82.0 | 76.1 | 83.0 | 76.9 | 79.8 |

| Neutral | 91.2 | 89.5 | 90.3 | 64.8 | 58.0 | 61.2 | 74.0 | 64.8 | 69.1 |

| Sad | 87.9 | 86.1 | 87.0 | 60.4 | 71.0 | 65.3 | 59.0 | 60.1 | 59.5 |

| Surprise | 79.7 | 91.7 | 85.3 | 67.5 | 50.0 | 57.4 | 69.0 | 68.5 | 68.8 |

| Configuration | PFN | AFP | ESV | RAF-DB | AffectNet-7 | ExpW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP Baseline | No | No | No | 85.20 | 59.34 | 64.28 |

| PFN + CLIP | Yes | No | No | 86.51 | 60.79 | 65.42 |

| PFN + CLIP + AFP | Yes | Yes | No | 88.73 | 61.97 | 66.85 |

| QC-FER (Full Pipeline) | Yes | Yes | Yes | 89.39 | 62.29 | 67.17 |

| Configuration | Pose Norm | Robust Std | PCA DimRed | Class Balance | Ensemble | RAF-DB | AffectNet-7 | EXPW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 85.20 | 59.34 | 64.28 |

| +Pose Normalization | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 86.51 (+1.31) | 60.79 (+1.45) | 65.42 (+1.14) |

| +Robust Standardization | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 87.88 (+1.37) | 61.53 (+0.74) | 66.08 (+0.66) |

| +PCA Dimensionality Reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 88.32 (+0.44) | 61.82 (+0.29) | 66.51 (+0.43) |

| +Class Balance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 88.73 (+0.41) | 61.97 (+0.15) | 66.85 (+0.34) |

| Complete Model | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 89.39 (+0.66) | 62.66 (+0.59) | 67.17 (+0.32) |

| Feature Extractor | Pre-training Data | Feature Dim | RAF-DB | AffectNet-7 | EXPW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 (ImageNet) | 1.2 M images | 2048 | 84.30 | 58.70 | 63.20 |

| ViT-B/16 (ImageNet-21K) | 14 M images | 768 | 85.60 | 59.80 | 64.50 |

| CLIP ViT-B/32 | 400 M image–text pairs | 512 | 87.59 | 61.20 | 65.80 |

| CLIP ViT-L/14 (LAION-2B) | 2 B image–text pairs | 768 | 89.39 | 62.66 | 67.17 |

| PCA Dim. | Explained Variance (%) | Accuracy (%) | Training Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 128 | 83.7 | 84.71 | 8.2 |

| 256 | 91.2 | 86.34 | 12.5 |

| 384 | 95.8 | 87.02 | 18.7 |

| 512 | 98.1 | 88.32 | 25.3 |

| 640 | 99.5 | 88.17 | 34.8 |

| 768 | 100.0 | 87.95 | 45.2 |

| Ensemble Strategy | RAF-DB | AffectNet-7 | EXPW |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single LR | 88.32 | 62.29 | 66.85 |

| Single RF | 85.86 | 58.42 | 63.18 |

| Hard Voting (LR + RF) | 88.85 | 62.05 | 66.92 |

| Soft Voting (LR + RF) | 89.12 | 62.41 | 67.08 |

| Completed Soft Voting | 89.39 | 62.66 | 67.17 |

| Dataset | Profile Samples | Pre-Norm Acc (%) | Post-Norm Acc (%) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AffectNet-7 | 121 | 52.07 | 58.68 | +6.61 |

| RAF-DB | 308 | 74.35 | 81.17 | +6.82 |

| EXPW | 1878 | 48.23 | 54.96 | +6.73 |

| Method | Trainable Parameters | Per-Image Inference Time (ms) | Training Time (per Epoch) | Peak Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMUE (ResNet-50) | 43.2 M | 16.3 | 21.4 h | 10.8 GB |

| MA-Net (ResNet-101) | 55.7 M | 18.9 | 24.7 h | 12.1 GB |

| 3DDFA-V2 + FFGAN | 18.6 M | 21.5 | 26.0 h | 9.6 GB |

| QC-FER (ours) | 1.6 M | 6.8 | 4.2 h | 3.1 GB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, B.; Qu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, H.; Guo, J.; Xian, Y.; Ma, L.; Yu, J.; Chen, J. LLM-Based Pose Normalization and Multimodal Fusion for Facial Expression Recognition in Extreme Poses. J. Imaging 2026, 12, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010024

Chen B, Qu B, Zhou Y, Huang H, Guo J, Xian Y, Ma L, Yu J, Chen J. LLM-Based Pose Normalization and Multimodal Fusion for Facial Expression Recognition in Extreme Poses. Journal of Imaging. 2026; 12(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Bohan, Bowen Qu, Yu Zhou, Han Huang, Jianing Guo, Yanning Xian, Longxiang Ma, Jinxuan Yu, and Jingyu Chen. 2026. "LLM-Based Pose Normalization and Multimodal Fusion for Facial Expression Recognition in Extreme Poses" Journal of Imaging 12, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010024

APA StyleChen, B., Qu, B., Zhou, Y., Huang, H., Guo, J., Xian, Y., Ma, L., Yu, J., & Chen, J. (2026). LLM-Based Pose Normalization and Multimodal Fusion for Facial Expression Recognition in Extreme Poses. Journal of Imaging, 12(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010024