1. Introduction

Some of the most information-rich images are the results of processing of satellite data obtained by scanning the Earth’s underlying surface. In this case, the color formula for each pixel embodies the result of a complex transformation of remote sensing spectral data. The standard approach to processing such information includes various procedures. These include primary geometric and radiometric correction procedures necessary to ensure data comparability [

1]. For example, the calculation of physical reflectivity of the underlying surface in selected spectral bands [

2], as well as the transformation procedures themselves, of calibrated spectral data, carried out within various types of thematic processing.

The long-term operation of natural resource satellite systems for monitoring the Earth’s surface has allowed the accumulation of large series of remote sensing data. Currently, information describing periods of several decades is available, for example, the EOS MODIS archives (since 1999) [

3] or LANDSAT (since 1987) [

4]. Thus, it has become possible to obtain robust, long-term estimates of the spectral characteristics of the Earth’s surface and parameters associated with them, including characteristics of long-term change trends [

5]. The availability of long-term estimates, which can be components of the analyzed images, has complicated thematic processing due to the ability to solve more complex problems, thereby increasing the need for the development of new image processing algorithms.

The list of mathematical methods for analyzing the spectral characteristics of the underlying surface, applied within the framework of thematic analysis, is quite extensive. It is possible to only note certain areas of this diversity. For example, the calculation of spectral indices, which are understood as the arithmetic of individual spectral bands, which allows us to identify and quantitatively describe many types of characteristic objects on the underlying surface. For example: vegetation indices [

6]; water indices [

7], soil indices [

8]; mineralogical indices [

9]. More complex mathematical approaches are used to assess changes in the underlying surface, which may be associated with the presence of long-term trends [

10] or seasonal cycles [

11]. In all these cases, additional clustering procedures for spectral data sets can be applied for deeper analysis [

12]. The development of computing power in recent years has facilitated significant progress in intelligent analysis methods, such as machine learning [

13] and AI [

14].

The goal of thematic processing of spectral remote sensing data is always to reduce the dimensionality of the analyzed phase space by identifying internal patterns. Ideally, the dimensionality of such a phase space should be reduced to one as a result of processing, which best quantitatively describes the target thematic feature. The resulting image represents a final map of the spatial distribution of the thematic feature.

In practically important cases, the nature of the thematic feature is complex and multifaceted and often cannot be simply described. These may include, for example, the degree of desertification [

15] or the stages of land degradation [

16], land cover forecasts [

17], including agricultural land status [

18], and many others. In this case, multivariate models based on wide sets of external parameters can be used to determine the mathematical relationships between the original spectral characteristics and the thematic feature. For example, the WOFOST model, used to describe the growth and development of agricultural crops [

19]. Such models typically have many input parameters, only some of which represent information associated with remote sensing data. When considered at a regional scale, information on many parameters becomes less accessible and is replaced by expert assessments, which makes the modeling results partly subjective and reduces their accuracy. The new algorithm proposed in this study, which aims to identify gradient patterns within analyzed images, enables empirically expanded thematic interpretation capabilities, which is particularly significant for pseudocolor composite images generated from remote sensing spectral data and their processed products. This new strategy, based on detecting the actual presence of gradient structures in analyzed images and describing them within a rank scale, allows for the identification of additional relationships existing in the phase feature space, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of remote sensing data thematic interpretation.

In fact, the new approach to thematic processing enables the construction of empirical equations for the relationship between the initial spectral parameters used to construct the analyzed image and the recorded textural features of the image, representing gradient structures. It also allows for varying the spectral parameters during image generation to obtain more pronounced gradient structures. This methodology is somewhat similar to spectral indices. However, unlike the fixed ratio of spectral bands, which typically describe physically clear properties of the underlying surface, spectral indices use arbitrary sets of spectral information that can describe complex characteristics of spatially distributed structures.

Similar approaches can be used not only for the analysis of remote sensing data, but also for solving other problems related to automated image analysis, for example, problems of analyzing data obtained using meteorological radars [

20,

21,

22] or problems of image analysis in medicine [

23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Principles of Recalculation of the Results of Clustering of Remote Sensing Data into Ranking Scales

Remote sensing data, including satellite images, require preliminary processing before its practical use, for which there is a set of methods and techniques [

24]. The depth of remote sensing data processing is associated with the type of scales used to describe the results obtained. The simplest is the nominal scale, which is a simple list of the present independent spectral classes, in which the order of the relative positions of the classes in the scale does not matter. A more complex case arises when there are significant relationships between spectral classes. The description of such situations can be based on rank scales. The presence of a rank order allows sorting and assigning ranks (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.) to the available spectral classes and thus obtaining deeper estimates of the structure of the results of thematic processing. The possibility of quantitatively accounting for the differences between spectral classes of different ranks leads to the use of interval scales or coefficient scales. The last two cases are variants of the most widely used types of quantitative scales of spectral classes used in the quantitative processing of remote sensing data [

25].

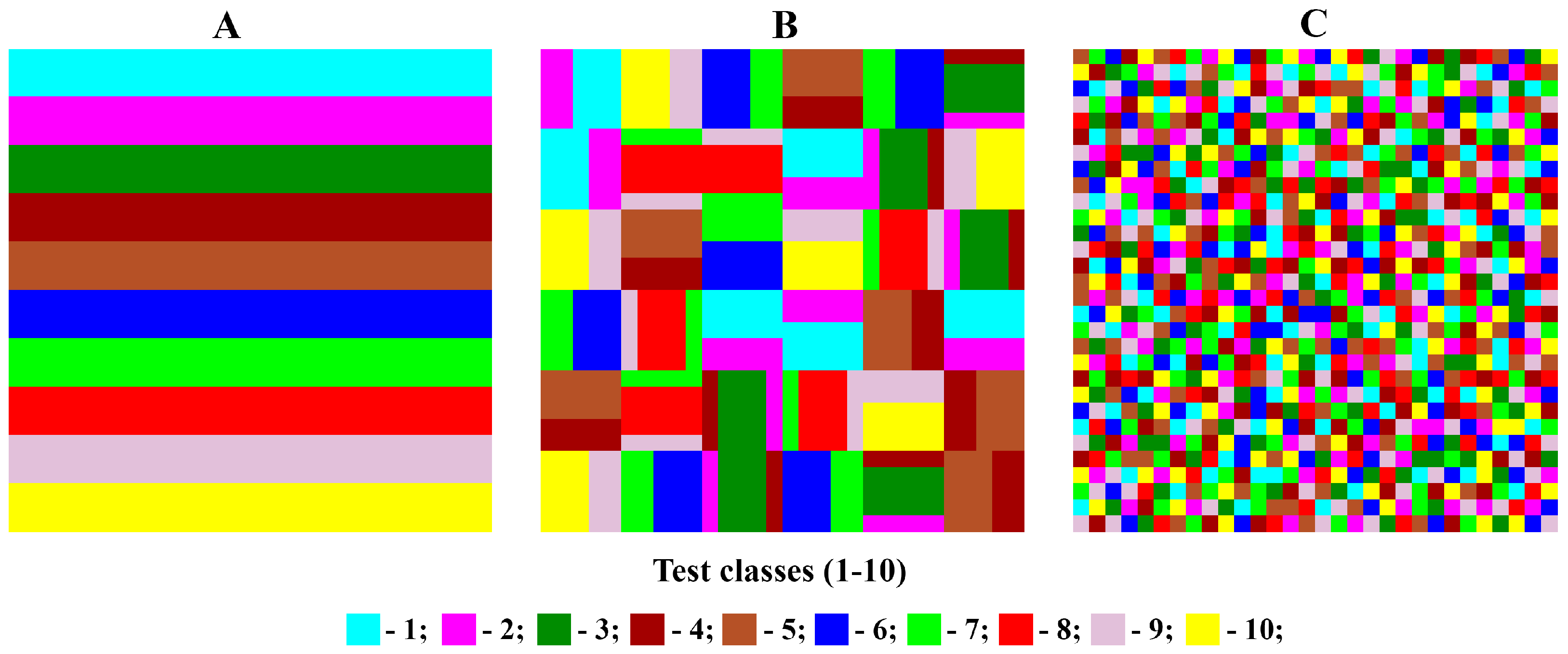

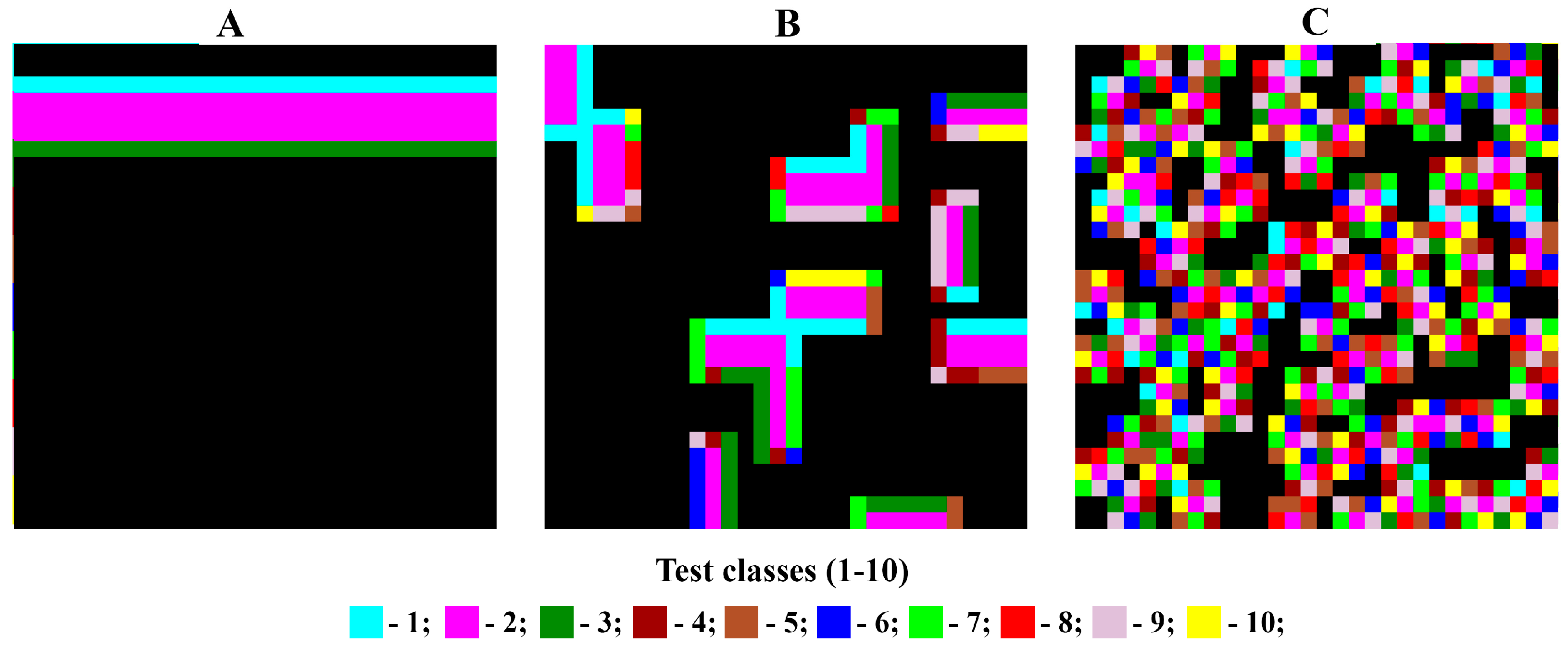

The result of a standard unsupervised classification/clustering procedure for remote sensing data is described by a nominal scale, i.e., a set of individual independent spectral classes. However, in reality, certain types of relationships may still be present in the final results. For example, if the analyzed spectral image of the underlying surface was closely related to territorial properties that can be described within the concept of gradient, the texture of the images obtained through clustering may contain information that allows for further ordering of the spectral classes within the rank order of gradient structures. Identifying the presence of such capabilities represents a new and important task, the solution of which could significantly improve the information content of thematic image analysis based on remote sensing data obtained after unsupervised clustering.

The presence of a gradient order in the clustering results implies the existence of an ordinal scale (K1, K2, K3, …, Kn) for spectral classes applicable to the entire analyzed image, which imposes certain restrictions on the spatial mutual arrangement of pixels of different spectral classes. Any spectral class within the ordinal scale (Km), with the exception of marginal ones (the first and last), should ideally be adjacent to only two classes adjacent to it on the scale, i.e., km-1 and Km+1. This state corresponds to the presence of a gradient structure described by a series consisting of classes K1, K2, K3, …, Kn. For example, in a thermal image of a monotonic gradient temperature field in the temperature range from 0 to +30 °C, with a change step of 1 °C, pixels characterizing +20 °C will border only each other or with pixels displaying a temperature of +19 °C or +21 °C. Gradient textures of any kind present in the analyzed graphic scene will also be organized similarly. However, of course, certain adjacency rules may not be strict, but rather expressed only as statistically expressed preferences.

If the spatial scale of class gradients within an ordinal scale is comparable to the spatial resolution of remote sensing data, or neighborhood rules are not strict, then strict adherence to such a rank order in the immediate neighborhood becomes impossible, and the ranking order may be distorted. In fact, the process of unsupervised clustering of remote sensing data can lead to extremely diverse results, organized in various ways: from truly independent classes forming a texture of random mosaic contrast to ensuring a strictly observed gradient structure.

Therefore, a specialized texture analysis of the results of unsupervised clustering of satellite data, which involves considering the immediate neighborhoods of each pixel, can provide the necessary information for assessing the feasibility of ordering a nominal set of spectral classes within a rank scale. The algorithm developed in this study is designed to evaluate all possible rank ordering options existing in an image of spectral classes and select the best rule that ensures the greatest degree of gradient consistency in pixel arrangement.

2.2. Algorithm for Texture Analysis of Spectral Classes on a Regular Lattice

The idea of nearest neighbor analysis for each pixel of the analyzed image is well known and is often used in various image processing methods [

26,

27,

28].

This is also the direction of Cellular Automata, in which dynamic structures are formed by a set of rules for the analysis and transformation of the immediate environment of each cell on regular grids, at each step of discrete time [

29]. Also, the literature describes many methods for searching and evaluating various patterns in analyzed images [

27,

30,

31,

32]. At the same time, based on the use of similar principles, the solution to a number of specific problems of thematic decoding of remote sensing data is described, for example [

33,

34,

35,

36], including the broad field of computer vision [

37], or more complex rules for analyzing image texture [

38,

39,

40].

In this study, we describe a new version of an image texture analysis algorithm based on nearest-neighbor statistics for the detection of gradient patterns. Although only the immediate neighborhood of each pixel is analyzed, the results are statistically expressed, describing the presence of preferences for certain types of nearest-neighbor relationships between spectral classes. We also analyze the extent to which these textural features can be described within a rank scale, i.e., consistent with the gradient structure. The gradient structure implies not only the presence of statistically identified types of preferential neighborhoods between spectral classes, but also their consistency and the possibility of ordering them within a rank scale: first, second, third, and so on.

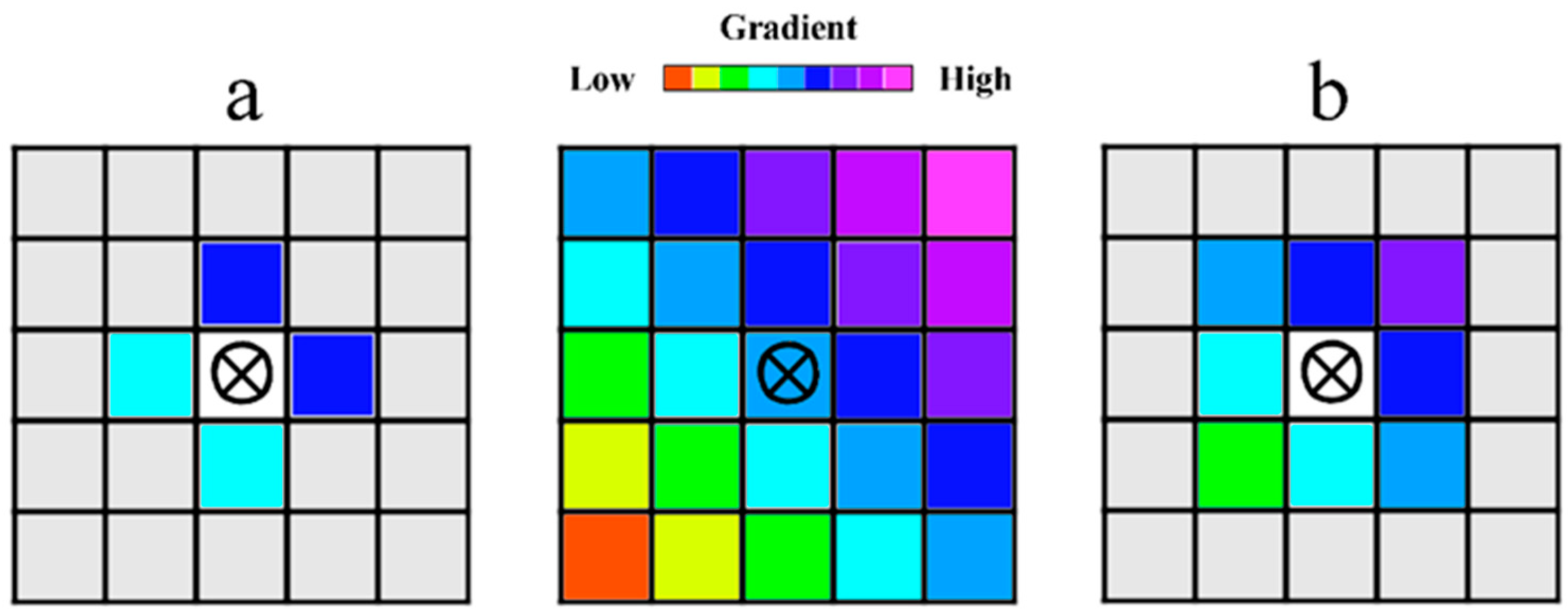

The analysis of the relative positions of pixels of different spectral classes in an image is based on the statistics of the immediate neighborhoods of each pixel. There are two possibilities. First, the Von Neumann neighborhood, which is four adjacent cells on a square grid (

Figure 1a). Thus, for a cell [i, j] on a two-dimensional square grid, these are the cells with coordinates: [i + 1, j]; [i − 1, j]; [i, j + 1]; [i, j − 1]. Another option is the Moore neighborhood, consisting of 8 cells, which are the von Neumann neighborhood with the addition of four more diagonal cells: [i + 1, j]; [i − 1, j]; [i, j + 1]; [i, j − 1]; [i + 1, j + 1]; [i − 1, j − 1]; [i − 1, j + 1]; [i + 1, j − 1] (

Figure 1b) [

41]. The Moore neighborhood provides a somewhat larger statistical sample, which makes it preferable, especially in the case of relatively small matrices (

Figure 2), but there are no fundamental differences between these options.

The final result of the statistical neighborhood analysis can be represented as a neighborhood matrix. This matrix contains complete information on the number and types of spectral classes present in the vicinity of Moore, for all spectral classes formed by clustering the satellite data. The proposed algorithm uses an exhaustive search for all possible rank scale variants to find the best one based on the criterion of the largest proportion of image pixels whose spatial arrangement is consistent with the gradient concept. The flowchart of the proposed algorithm is shown in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

The above-described algorithm for texture image processing for gradient pattern detection expands the capabilities of spectral information processing by incorporating certain morphological features of the analyzed image. Analysis of the spectral characteristics of pixels in their immediate vicinity provides information on the presence of certain types of preferential neighborhoods (binary patterns), which serves as the basis for diagnosing the presence of gradient patterns and the significance of these morphological features for the entire graphic scene or its individual key areas. The methodology proposed in this study is adapted for the analysis of remote sensing data, including satellite imagery and products based on them, but is not limited to this range of tasks.

Recording and describing gradient patterns in the analyzed graphic scene, such as a pseudocolor composite image, using an appropriate scale can significantly enhance the thematic processing of satellite data. This requires solving two problems. First, recognizing the presence and composition of a gradient. Which spectral classes present in the image, and in what order, form a property gradient. Second, expert determination of the physical meaning of the gradient. The gradient of underlying surface properties is recorded through the identified rank order of spectral classes. This significantly simplifies subsequent thematic interpretation of the obtained clustering results. Expert interpretation of each spectral class becomes unnecessary, only their ensemble within the rank scale describing the gradient structure. It is also desirable to understand the physical meaning of the detected gradient, initially constructing qualitative and, subsequently, possibly quantitative rank estimates.

Geographically distributed objects, including various natural and anthropogenic ones, such as soil or vegetation cover, agricultural land, etc., can be described by various thematic maps using parameters that allow for dependencies expressed as gradients. A new strategy for processing remote sensing data is emerging for such objects. This strategy is based on feedback and optimization. A specific set of initial remote sensing data can provide some description of the gradient structure of the Earth’s underlying surface, serving as the basis for thematic analysis. Consequently, the researcher has the opportunity to vary the initial data to obtain more meaningful gradient patterns. This allows for an empirical search for the most informative remote sensing sources. This innovation is particularly valuable for describing complex processes, including long-term territorial changes, for which the principles of description are unclear and the parameters used can be complex. For example, the degree of desertification, degradation of the underlying surface, or long-term trends in agricultural land characteristics. The morphological features of images containing gradient patterns are quite distinctive. In the case of a linear trend, a key region of the image will have a certain isopotential direction along which spectral classes are quasi-stable. A perpendicular direction will also be present, with a wide variety of spectral class types. The proposed texture processing algorithm provides a metric for the significance of gradient patterns and the composition of the ranking scale for the best description, eliminating the need for purely expert assessments.

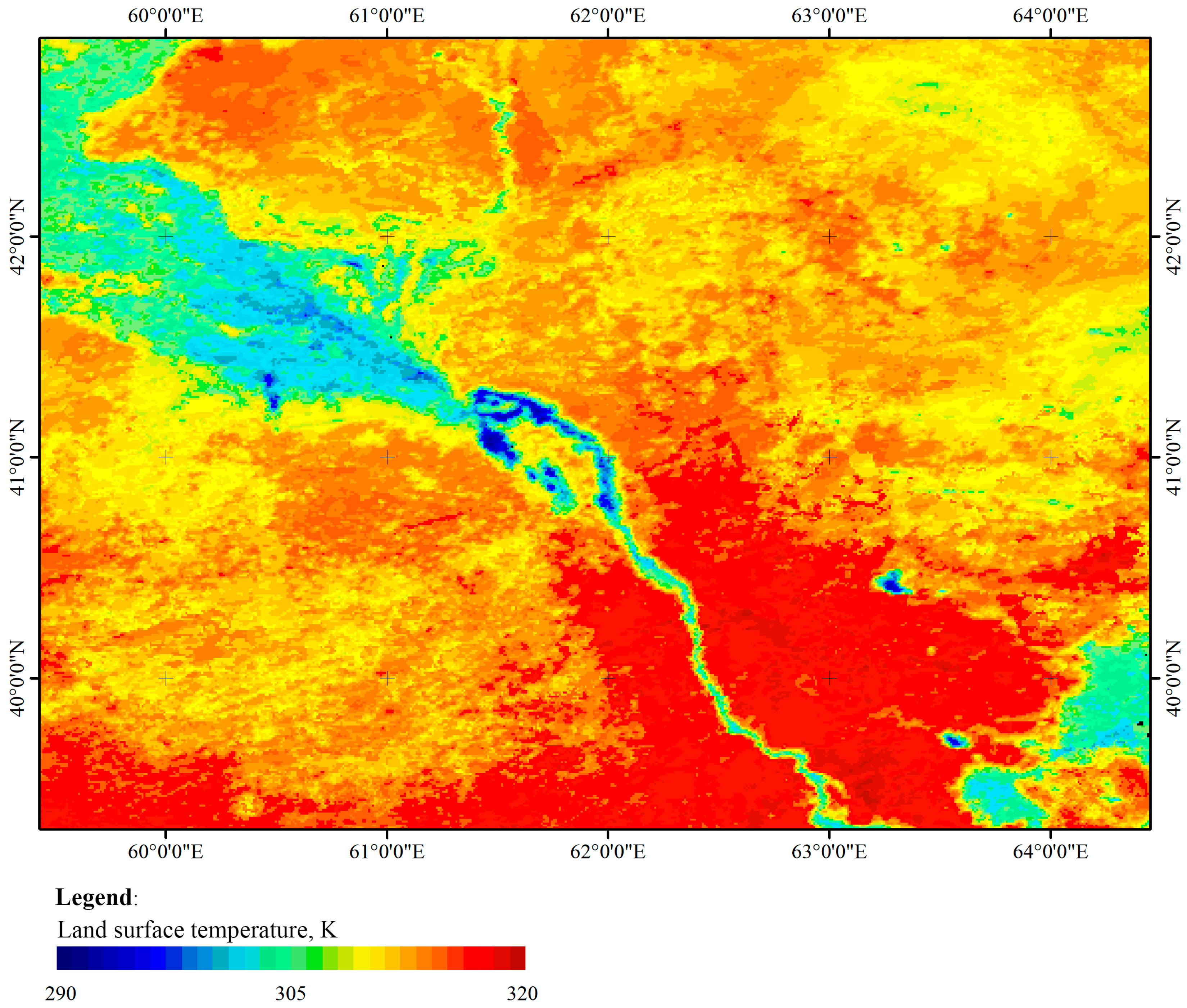

To illustrate the practical significance of the above-described idea of using gradient patterns in processing spectral remote sensing data, we can consider the problem of estimating the average long-term secondary salinity of irrigated arable land in southern Kazakhstan. Secondary salinity of irrigated arable land is a dynamic process with varying time scales [

45]. There are both intra-seasonal and inter-seasonal dynamics. At the beginning of the growing season, the level of secondary salinity is lower. By the end of the season, it increases. Inter-seasonal dynamics are also significant and are related to weather conditions, particularly the availability of water for irrigation. Dry and wet years differ significantly in the water availability of arid areas in southern Kazakhstan. Taken together, all this creates a complex dynamic picture, making it significantly difficult to describe average long-term conditions. However, it is the average long-term conditions that have the highest practical significance, since they serve as the basis for making management decisions in the field of territorial hydrology and the administration of irrigated agriculture.

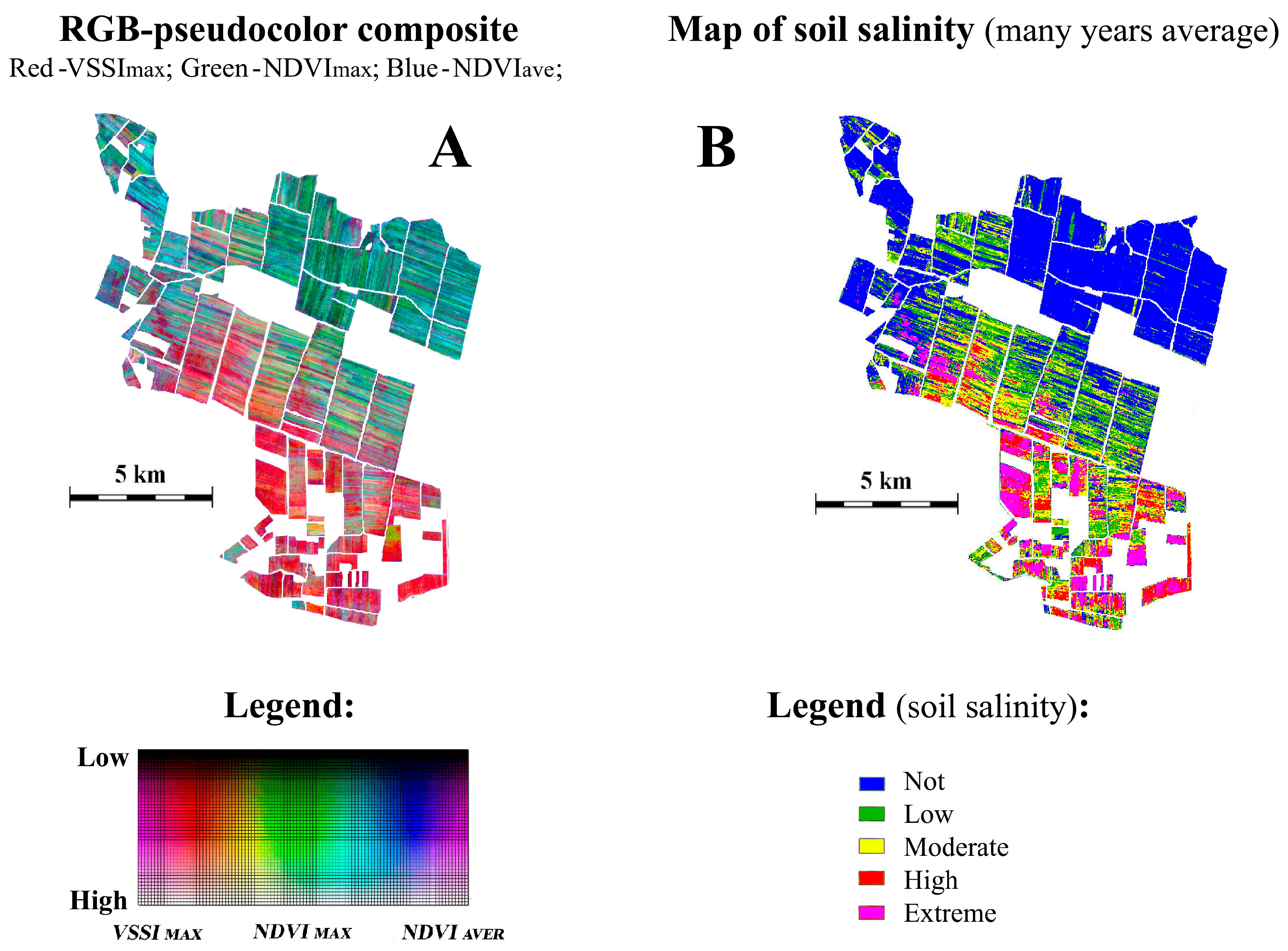

Pseudocolor RGB composite images of the southern Kazakhstan region were constructed using Sentinel-2 satellite data, displaying perennial characteristics of vegetation, including irrigated fields. The spectral channels of the RGB composite were formed by analyzing the Sentinel-2 satellite data archive for the period 2018–2022. The Vegetation Soil Salinity Index (VSSI) was used as the RED channel long-term maximum [

46].

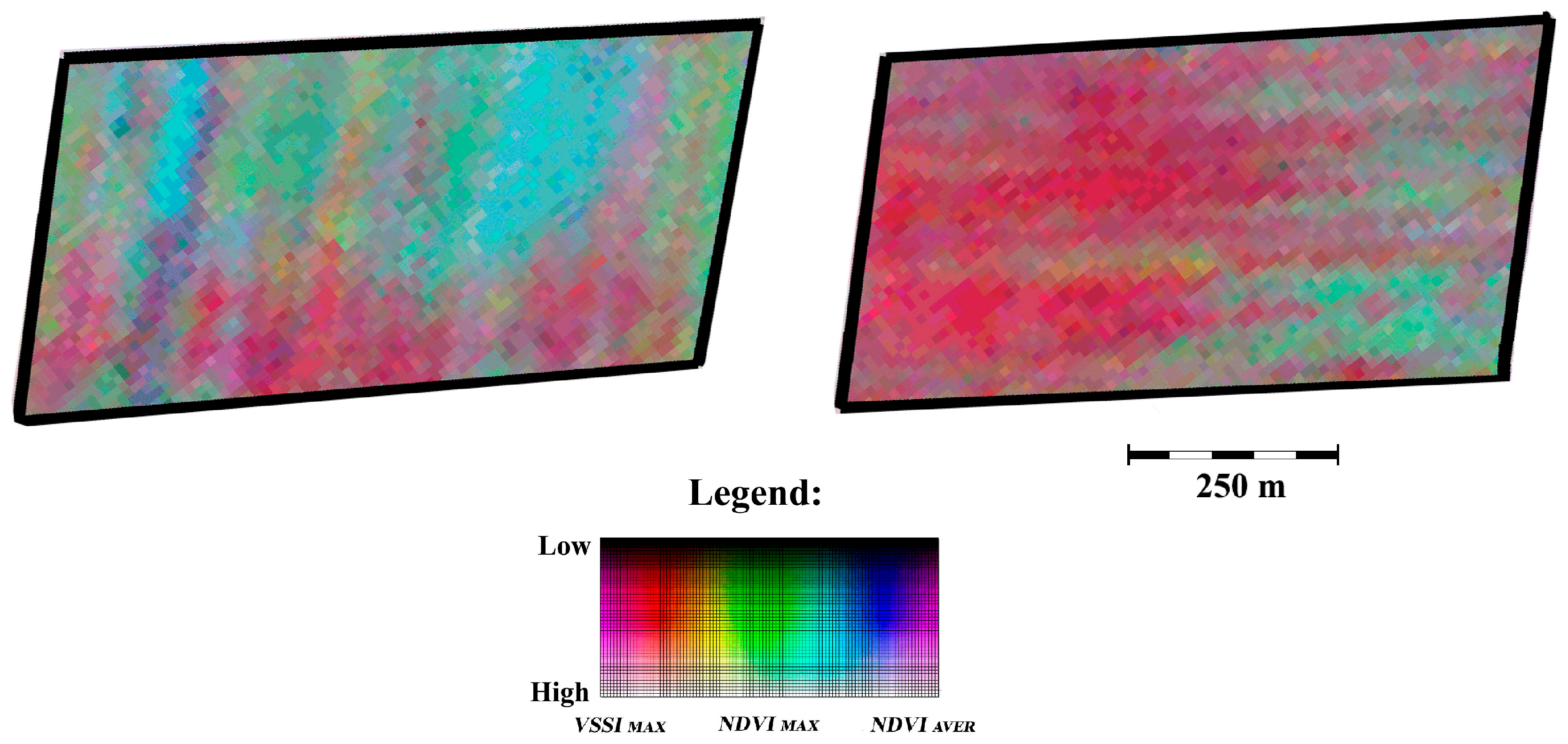

The GREEN channel represented the NDVI vegetation index, in the form of its long-term maximum, and the BLUE channel represented the long-term average NDVI value. In this work, an expert analysis of the RGB composite of the field area with a known gradient structure of the secondary salinity level was carried out,

Figure 12. As a result, the expert interpretation restored the rank order of the spectral classes within the framework of their relationship with the level of secondary salinity of arable land, and based on the resulting legend, the original RGB composite was recalculated into a map of the average long-term secondary salinity level [

47].

The identification and expert analysis of gradient properties in soil salinity (

Figure 12) enabled the conversion of the nominal scale of the RGB pseudocolor composite to a scale of average long-term soil salinity (

Figure 13).

Figure 13 illustrates the importance of morphological analysis based on expert recognition of gradient structures for a more in-depth thematic analysis of the spectral structure of the analyzed graphic scene, for example, in the task of estimating average long-term soil salinity.

Thus, the algorithm described in this paper for converting from a nominal scale of spectral classes to a rank scale expands the capabilities of thematic processing of graphic scenes, including those constructed based on remote sensing or other similar data [

48,

49], replacing complex and subjective expert analysis. This procedure may be of interest as a new, additional feature in the toolbox of thematic processing of satellite information within the framework of relevant specialized software.

The limitations of using the developed image texture analysis procedure are minimal. Analysis of spectral class types in the immediate vicinity of each pixel in an image can, in principle, be performed for any image. However, the presence of a large number of different spectral classes in the analyzed graphic scene makes the mathematical process of finding the most appropriate gradient scale quite cumbersome. The total number of possible gradient scale combinations, including all spectral classes present in the image, is a factorial of the number of spectral classes. This means that the volume of necessary calculations rapidly increases with the number of classes. Another potential problem is the presence of multiple independent gradients in the image, each described by only a subset of the spectral classes present. In this case, a more advanced analysis algorithm than the one described above will be required, which could become the next step in the development of this field.

5. Conclusions

In summary, a new image texture analysis algorithm has been developed based on the statistical analysis of spectral class types in the immediate vicinity of a pixel. The purpose of the analysis was to identify and evaluate the significance of specific morphological image features expressed as gradient patterns. The original spectral classes, initially organized within a nominal scale, are sorted into a rank scale in the gradient legend.

The developed image processing algorithm may be of greatest practical use for thematic analysis of pseudocolor composite images constructed from remote sensing data, including satellite imagery. This opens up new and interesting possibilities for empirically selecting initial remote sensing data that provides better descriptions of territories using gradient patterns.

In the future, this texture analysis algorithm may be further modified to adapt it to specific sets of original data and thematic problems being solved. For example, pseudonearest neighbor analysis is an interesting option. It is also likely that complexly structured pseudocolor images may contain multiple spectrally independent gradient patterns, the analysis of which will enable deeper thematic data processing.

The developed image processing algorithm could form the basis for a separate, additional function in satellite data processing tools within specialized software.