FluoNeRF: Fluorescent Novel-View Synthesis Under Novel Light Source Colors and Spectra †

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We address a novel problem of fluorescent novel-view synthesis under novel lighting colors and spectra.

- We propose a novel NeRF-based method by incorporating the superposition principle of light without explicitly modeling the geometric and photometric models of a scene of interest.

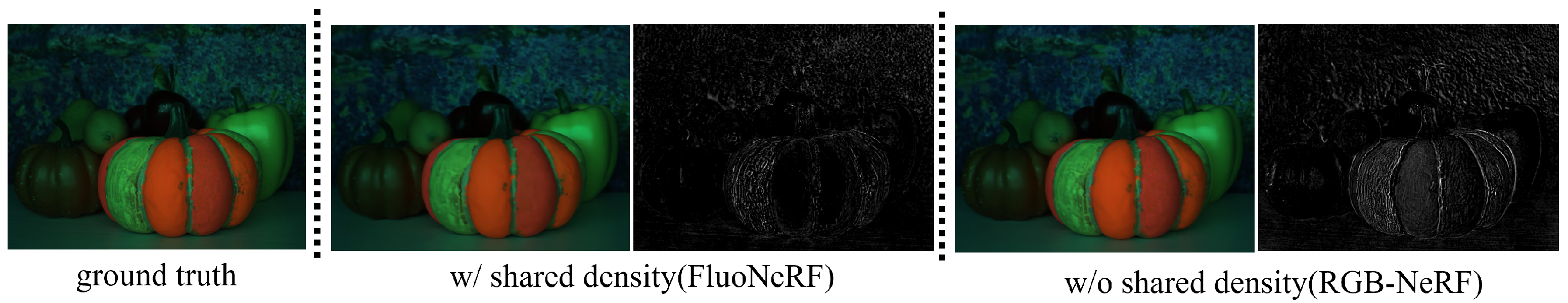

- Through a number of experiments with a color display, we confirm the effectiveness of our proposed method with shared volume densities.

- We show that our method performs better than the methods using the white balance adjustment, not only for fluorescent objects but also for reflective objects.

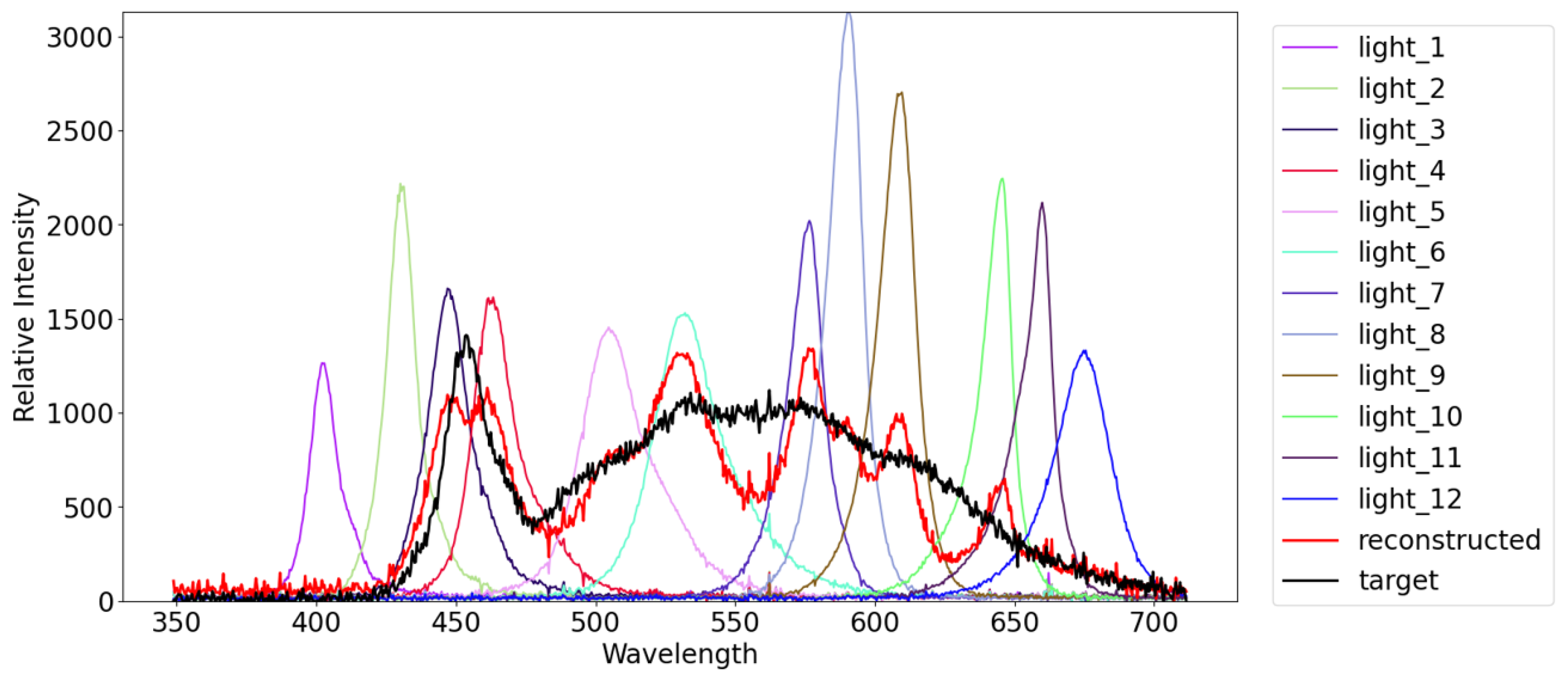

- In order to improve the resolution and range of light source spectra, we extend our method by leveraging more than three primary light source colors.

- Through a number of experiments with a multi-spectral light stage, we show the effectiveness of the extension using more than three primary colors.

2. Related Work

2.1. Non-Reflective Materials

2.2. Varying Lighting Environment

3. Proposed Method

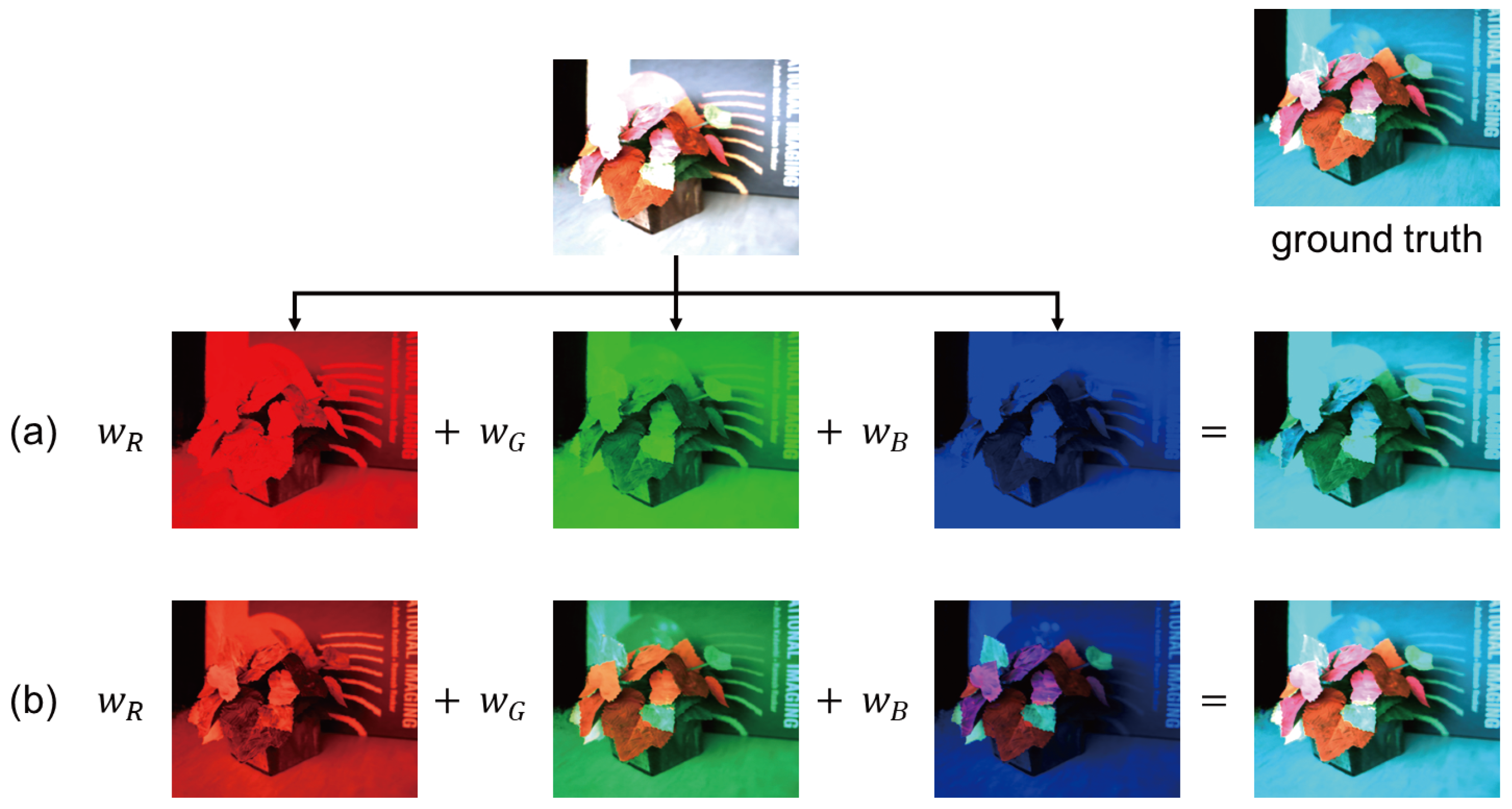

3.1. Superposition Principle

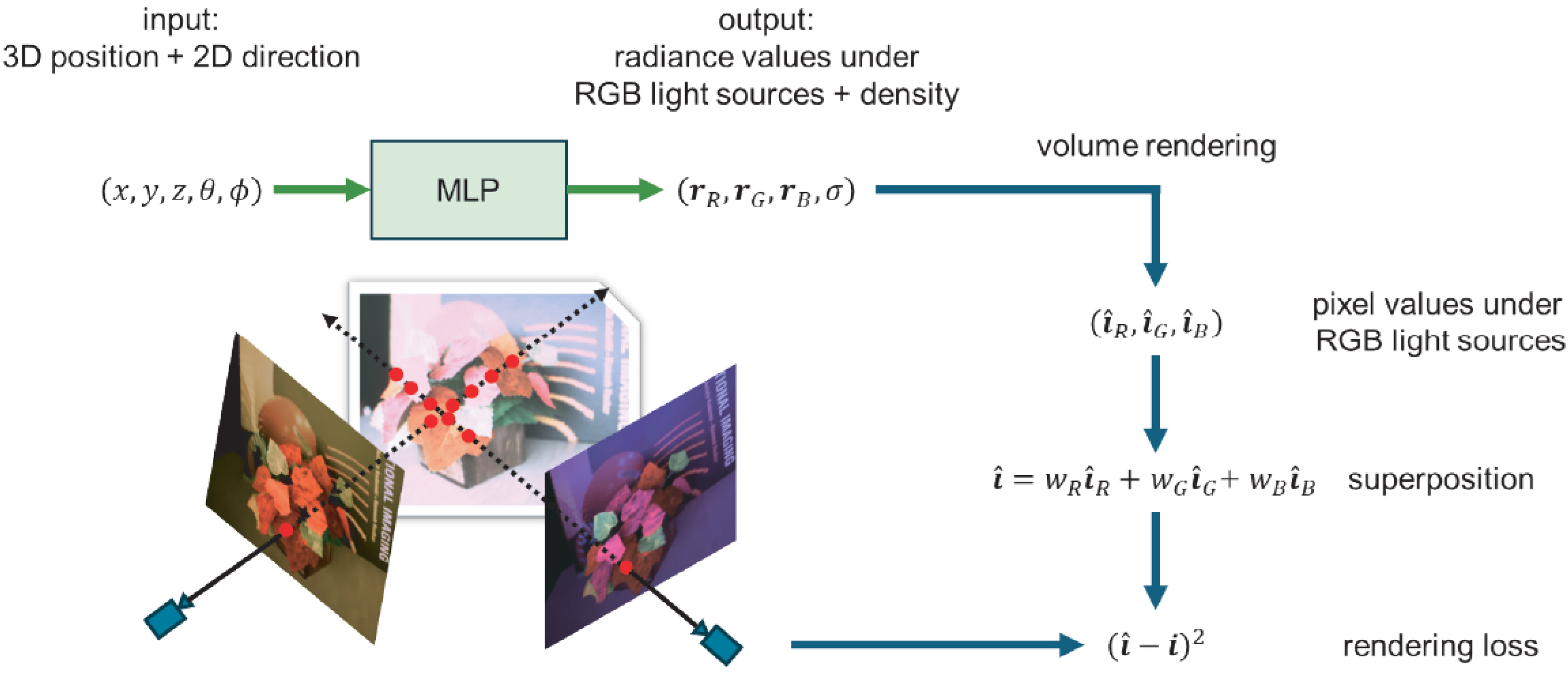

3.2. Pipeline

- A.

- Data Acquisition

- B.

- Preprocessing

- C.

- Training

- D.

- Image Synthesis

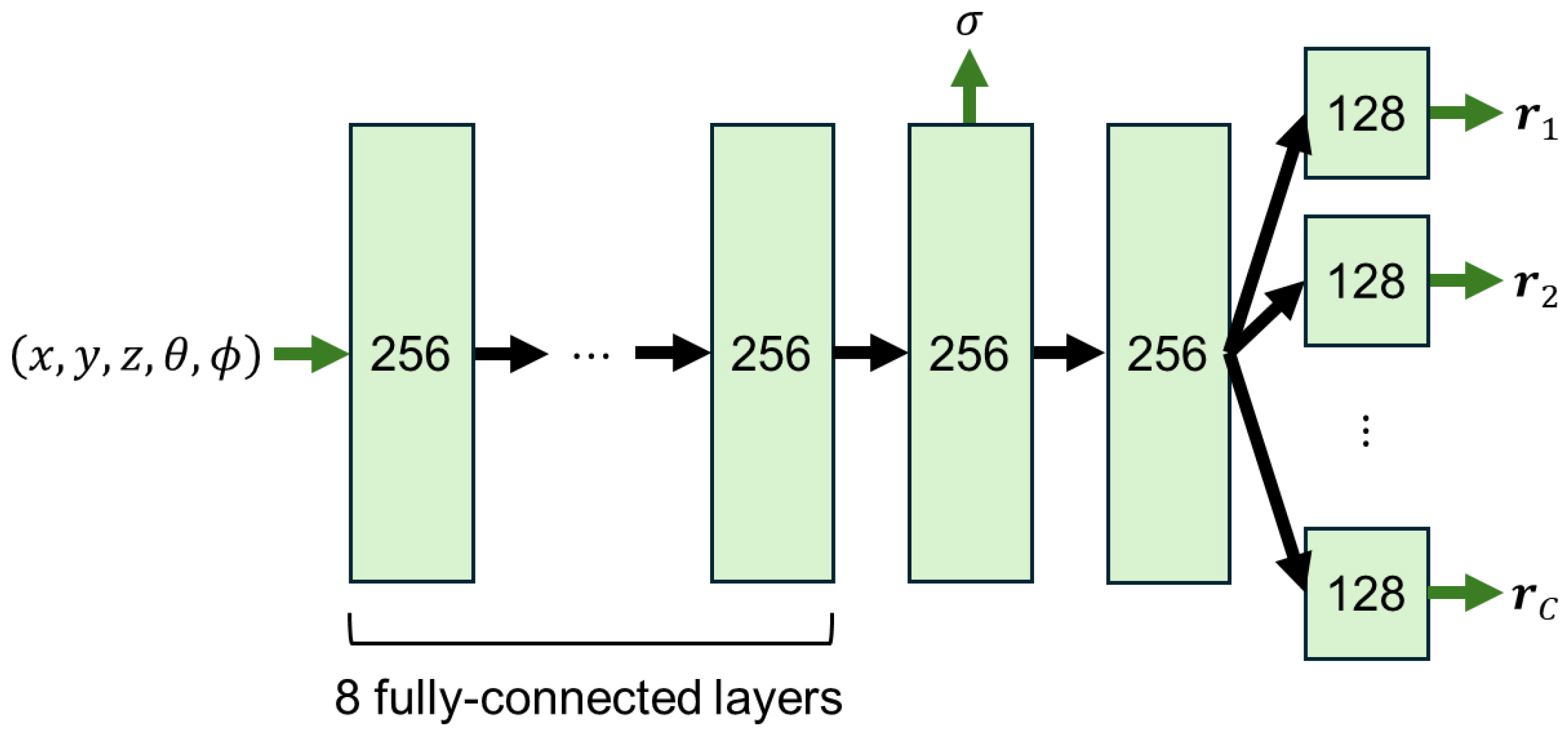

3.3. Network

- Architecture:

- Training:

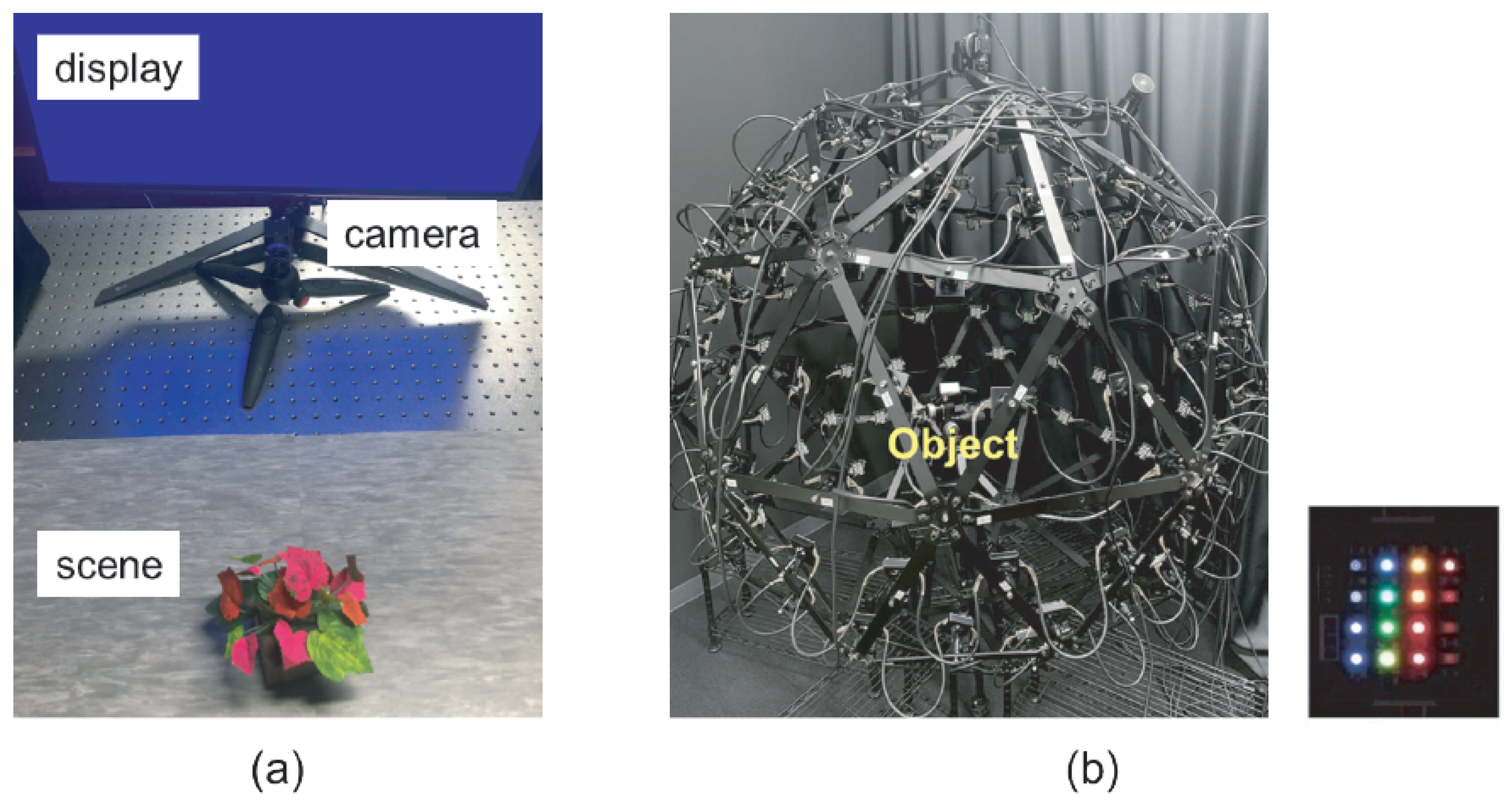

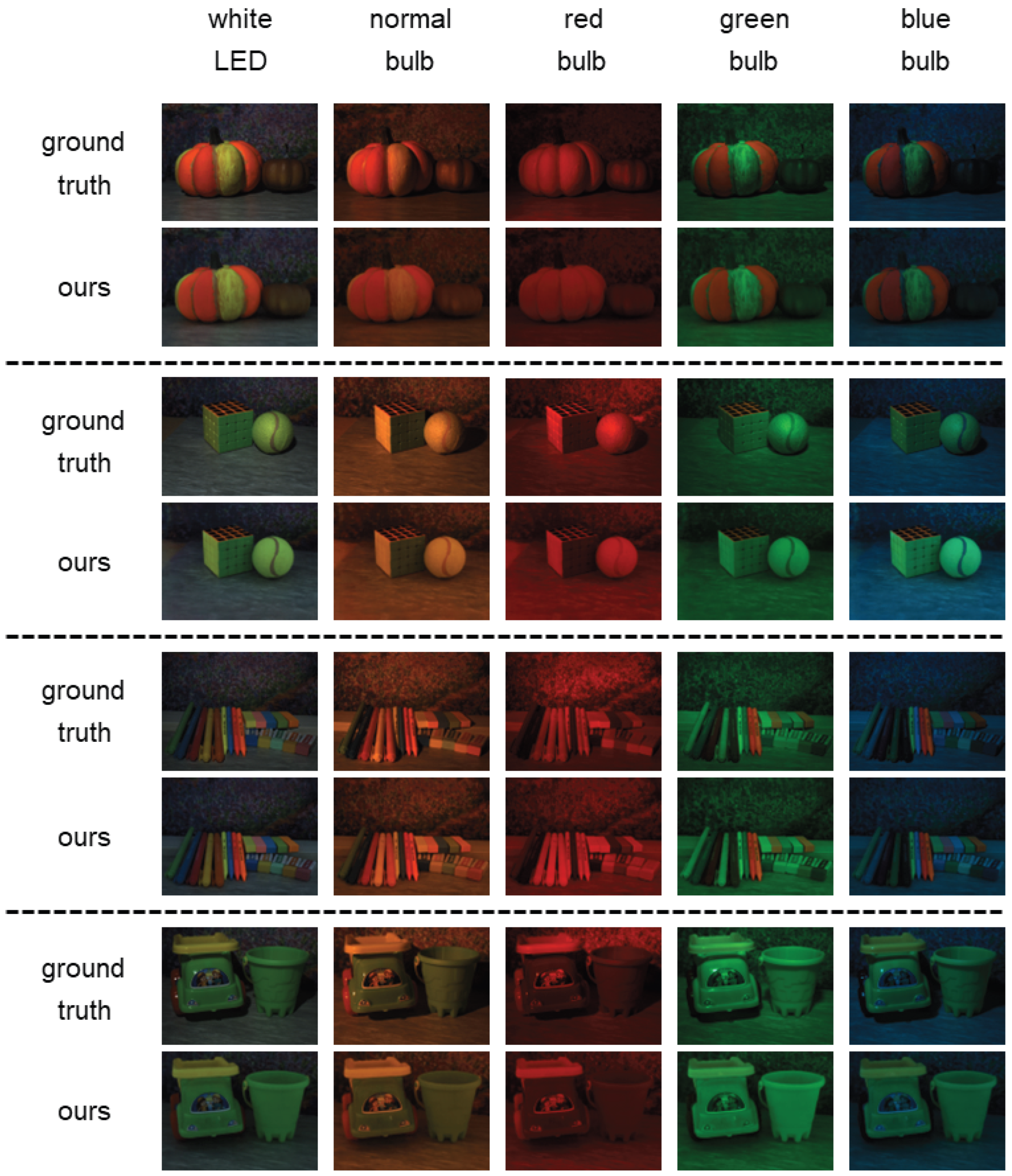

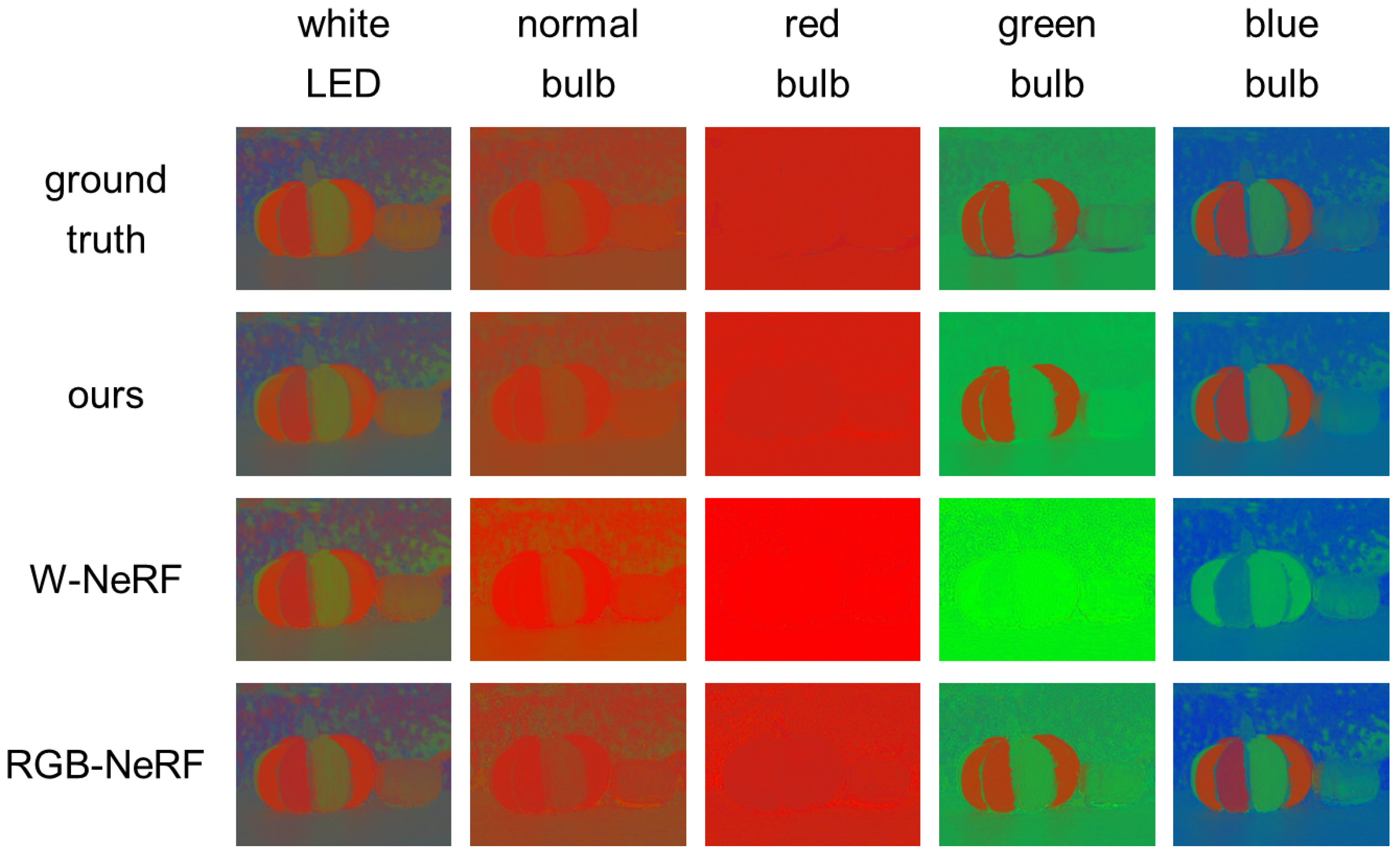

4. Experiments with Three Primary Colors

4.1. Setup

4.2. Results

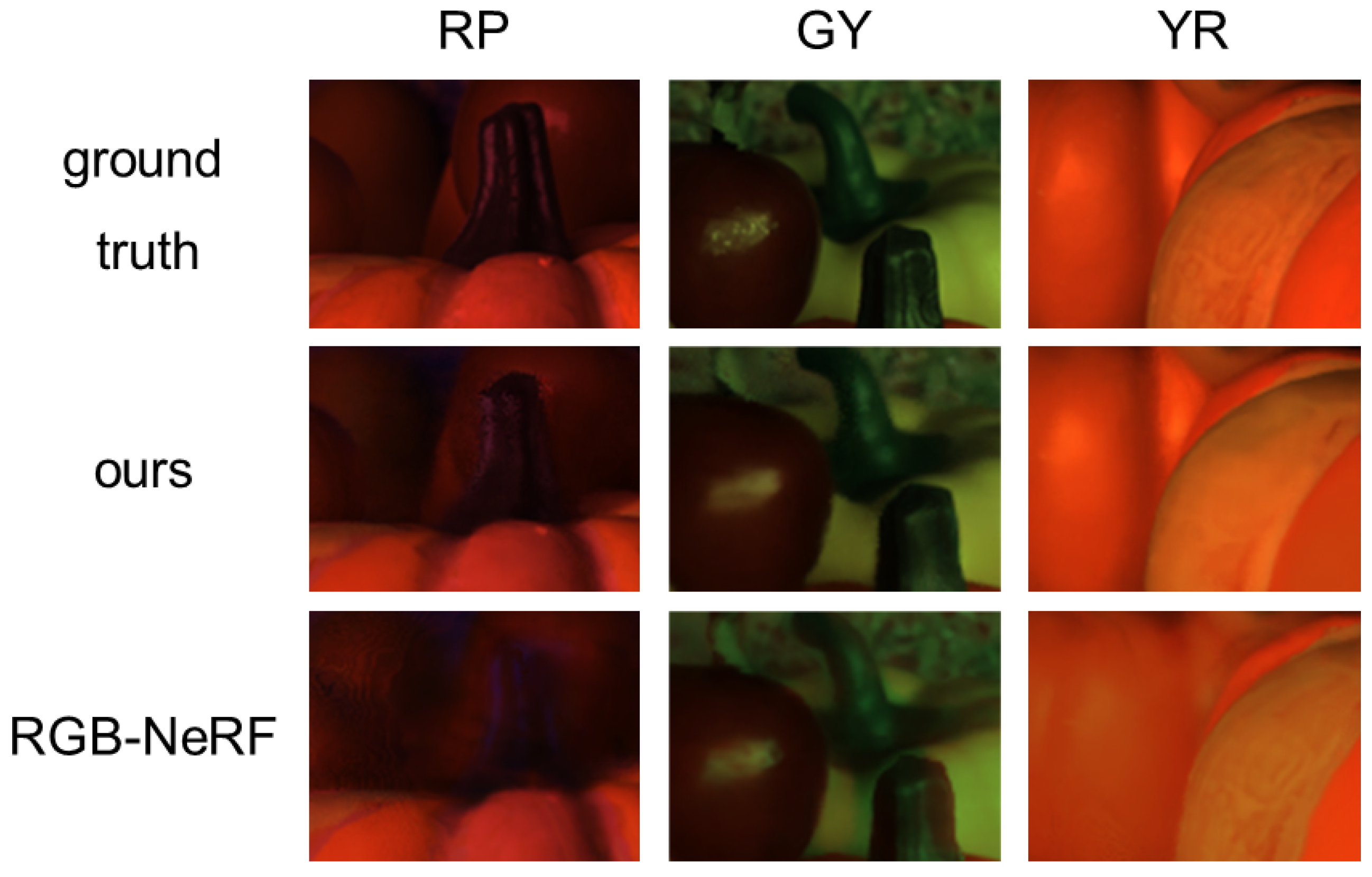

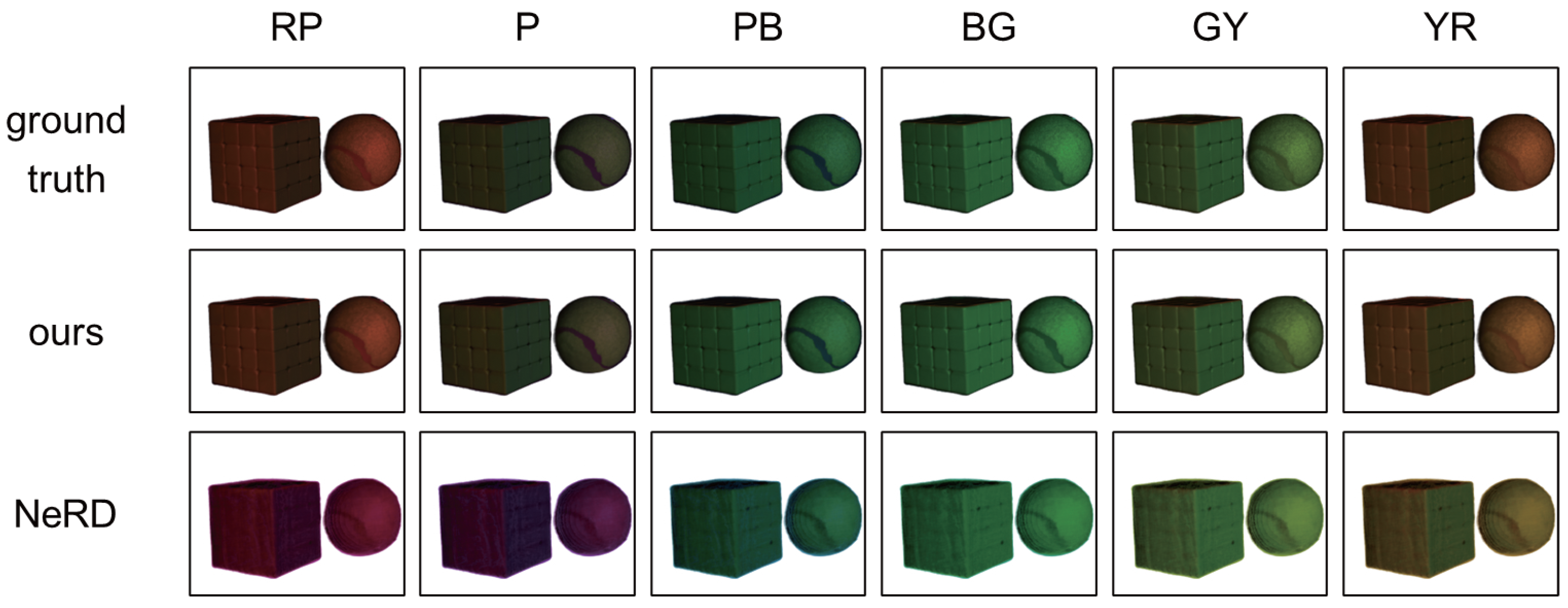

4.3. Comparison

- W-NeRF: the combination of the original NeRF [3] and the white balance adjustment. Specifically, an image from a novel viewpoint under white light source is synthesized by using the original NeRF, and then the color of the image is changed according to a novel light source color via the white balance adjustment.

- RGB-NeRF: three NeRFs, each of which is trained by using the images taken from varying viewpoints but under a fixed light source color (R, G, or B). Specifically, the three images from a novel viewpoint and under the three light source colors are separately synthesized by using the three NeRFs, and then the image under a novel light source color is synthesized by linearly combining the three images.

- NeRD [16]: one of the state-of-the-art techniques for scene recovery, i.e., for decomposing a scene into its shape, reflectance (BRDF), and illumination. We can synthesize the images of the scene from novel viewpoints under novel lighting environments by using those properties of the scene.

- Our method vs. W-NeRF:

- Our method vs. RGB-NeRF:

- Our method vs. NeRD:

- Reflective objects:

5. Experiments with More than Three Primary Colors

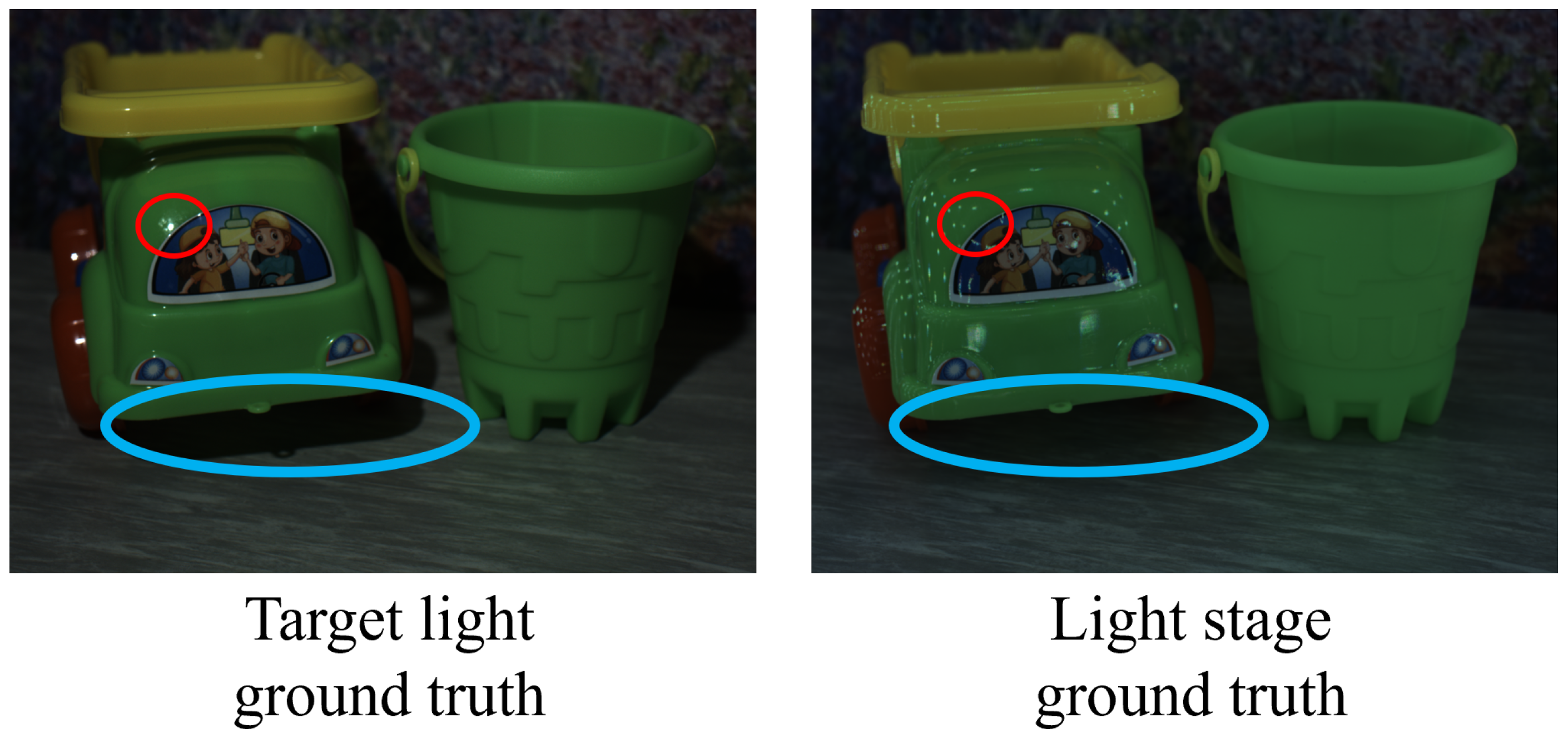

5.1. Setup

5.2. Results

5.3. Comparison

- Our method vs. W-NeRF:

- Our method vs. RGB-NeRF:

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Colors of Reflective Components

Appendix B. Colors of Fluorescent Components

References

- Barnard, K. Color constancy with fluorescent surfaces. Color Imaging Conf. 1999, 7, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sato, I. Separating reflective and fluorescent components of an image. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2011, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Feng, W.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Neural surface reconstruction of dynamic scenes with monocular rgb-d camera. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 967–981. [Google Scholar]

- Ost, J.; Mannan, F.; Thuerey, N.; Knodt, J.; Heide, F. Neural scene graphs for dynamic scenes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 2856–2865. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Florence, P.; Straub, J.; Newcombe, R.; Lovegrove, S. Deepsdf: Learning continuous signed distance functions for shape representation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Sinha, U.; Barron, J.; Bouaziz, S.; Goldman, D.; Seitz, S.; Martin-Brualla, R. Nerfies: Deformable neural radiance fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV2021), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 5865–5874. [Google Scholar]

- Pumarola, A.; Corona, E.; Pons-Moll, G.; Moreno-Noguer, F. D-nerf: Neural radiance fields for dynamic scenes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 10318–10327. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnev, V.; Elgharib, M.; Smith, W.; Liu, L.; Golyanik, V.; Theobalt, C. Nerf for outdoor scene relighting. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 615–631. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Guibas, L.; Wu, J. Unsupervised discovery of object radiance fields. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2022, Online, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Duisterhof, B.; Mao, Y.; Teng, S.; Ichnowski, J. Residual-nerf: Learning residual nerfs for transparent object manipulation. In InProceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ichnowski, J.; Avigal, Y.; Kerr, J.; Goldberg, K. Dex-NeRF: Using a neural radiance field to grasp transparent objects. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2110.14217. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.; Peleg, A.; Pearl, N.; Rosenbaum, D.; Akkaynak, D.; Korman, S.; Treibitz, T. Seathru-nerf: Neural radiance fields in scattering media. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman, A.; Ramanagopal, M.; Skinner, K. Waternerf: Neural radiance fields for underwater scenes. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2023—MTS/IEEE U.S. Gulf Coast, Biloxi, MS, USA, 25–28 September 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Cao, J.; Hu, Q.; Xu, L.; Yu, J.; Yu, J. Neref: Neural refractive field for fluid surface reconstruction and rendering. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computational Photography (ICCP), Madison, WI, USA, 28–30 July 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, M.; Braun, R.; Jampani, V.; Barron, J.; Liu, C.; Lensch, H. NeRD: Neural reflectance decomposition from image collections. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV2021), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12684–12694. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, M.; Jampani, V.; Braun, R.; Liu, C.; Barron, J.; Lensch, H. Neural-PIL: Neural pre-integrated lighting for reflectance decomposition. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS2021), Online, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 10691–10704. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Kang, D.; Bao, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, S. Nerfren: Neural radiance fields with reflections. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 18409–18418. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselgren, J.; Hofmann, N.; Munkberg, J. Shape, light, and material decomposition from images using monte carlo rendering and denoising. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 22856–22869. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, C.; Long, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Komura, T.; Wang, W. Nero: Neural geometry and brdf reconstruction of reflective objects from multiview images. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2023, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Brualla, R.; Radwan, N.; Sajjadi, M.; Barron, J.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Duckworth, D. Nerf in the wild: Neural radiance fields for unconstrained photo collections. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7210–7219. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Theobalt, C.; Komura, T.; Wang, W. Neus: Learning neural implicit surfaces by volume rendering for multi-view reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Online, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 27171–27183. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zoss, G.; Chandran, P.; Gross, M.; Bradley, D.; Gotardo, P. Renerf: Relightable neural radiance fields with nearfield lighting. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 22581–22591. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Qu, Y.; Fang, T.; McKinnon, D.; Tsin, Y.; Quan, L. Neilf: Neural incident light field for physically-based material estimation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 700–716. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Luan, F.; Wang, Q.; Bala, K.; Snavely, N. Physg: Inverse rendering with spherical gaussians for physics-based material editing and relighting. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 5453–5462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Fanello, S.; Tsai, Y.; Sun, T.; Xue, T.; Pandey, R.; Orts-Escolano, S.; Davidson, P.; Rhemann, C.; Debevec, P. Neural light transport for relighting and view synthesis. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2021, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Srinivasan, P.; Deng, B.; Debevec, P.; Freeman, W.; Barron, J. Nerfactor: Neural factorization of shape and reflectance under an unknown illumination. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2021, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; He, X.; Fu, H.; Jia, R.; Zhou, X. Modeling indirect illumination for inverse rendering. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 18643–18652. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, J.; Mildenhall, B.; Verbin, D.; Srinivasan, P.; Hedman, P. Zip-NeRF: Anti-aliased grid-based neural radiance fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV2023), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 19697–19705. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, J.; Mildenhall, B.; Tancik, M.; Hedman, P.; Martin-Brualla, R.; Srinivasan, P. Mip-NeRF: A multiscale representation for anti-aliasing neural radiance fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV2021), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 5855–5864. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Song, L.; Chen, L.; Yu, J.; Yuan, J.; Xu, Y. NeuRBF: A neural fields representation with adaptive radial basis functions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV2023), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 4182–4194. [Google Scholar]

- Garbin, S.; Kowalski, M.; Johnson, M.; Shotton, J.; Valentin, J. Fastnerf: High-fidelity neural rendering at 200fps. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 14346–14355. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkuehler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3d gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gu, J.; Lin, K.Z.; Chua, T.; Theobalt, C. Neural sparse voxel fields. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 15651–15663. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.; Evans, A.; Schied, C.; Keller, A. Instant neural graphics primitives with a multiresolution hash encoding. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2022, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretschk, E.; Tewari, A.; Golyanik, V.; Zollhöfer, M.; Lassner, C.; Theobalt, C. Non-rigid neural radiance fields: Reconstruction and novel view synthesis of a dynamic scene from monocular video. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12959–12970. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Lam, A.; Sato, I.; Okabe, T.; Sato, Y. Separating reflective and fluorescent components using high frequency illumination in the spectral domain. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Koyamatsu, K.; Hidaka, D.; Okabe, T.; Lensch, H.P.A. Reflective and fluorescent separation under narrow-band illumination. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7577–7585. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Lam, A.; Sato, I.; Okabe, T.; Sato, Y. Reflectance and fluorescence spectral recovery via actively lit rgb images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 38, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treibitz, T.; Murez, Z.; Mitchell, B.; Kriegman, D. Shape from fluorescence. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2012), Florence, Italy, 7–13 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hullin, M.; Hanika, J.; Ajdin, B.; Seidel, H.-P.; Kautz, J.; Lensch, H. Acquisition and analysis of bispectral bidirectional reflectance and reradiation distribution functions. ACM Trans. Graph. 2010, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Tewari, A.; Leimkühler, T.; Habermann, M.; Theobalt, C. Neural radiance transfer fields for relightable novel-view synthesis with global illumination. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Lin, K.; Bi, S.; Xu, Z.; Ramamoorthi, R. Nelf: Neural light-transport field for portrait view synthesis and relighting. In Proceedings of the EGSR2021, Saarbrücken, Germany, 29 June–2 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schechner, Y.; Nayar, S.; Belhumeur, P. A theory of multiplexed illumination. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Ninth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Nice, France, 13–16 October 2003; pp. 808–815. [Google Scholar]

- Ajdin, B.; Finckh, M.; Fuchs, C.; Hanika, J.; Lensch, H. Compressive Higher-Order Sparse and Low-Rank Acquisition with a Hyperspectral Light Stage; Technical Report WSI-2012-01; Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen: Tübingen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Debevec, P. The Light Stages and Their Applications to Photoreal Digital Actors. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia2012, Singapore, 26–27 November 2012. Technical Briefs. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Liu, C. Discriminative illumination: Per-pixel classification of raw materials based on optimal projections of spectral BRDF. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Kurachi, M.; Kawahara, R.; Okabe, T. One-Shot Polarization-Based Material Classification with Optimal Illumination. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications, Porto, Portugal, 26–28 February 2025; pp. 738–745. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Okabe, T. Joint optimization of coded illumination and grayscale conversion for one-shot raw material classification. In Proceedings of the 28th British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC2017), London, UK, 4–7 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.-I.; Lee, M.-H.; Grossberg, M.; Nayar, S. Multispectral imaging using multiplexed illumination. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 11th International Conference on Computer Vision, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–21 October 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schönberger, J.; Frahm, J. Structure-from-motion revisited. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schönberger, J.; Zheng, E.; Pollefeys, M.; Frahm, J. Pixelwise view selection for unstructured multi-view stereo. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diega, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Number of Images |

|---|---|

| Ours | 40 (C) + 40 (M) + 40 (Y) |

| W-NeRF | 120 (W) |

| RGB-NeRF | 40 (R) + 40 (G) + 40 (B) |

| NeRD | 120 (W) |

| Scene | Method | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 35.36 | 0.914 | |

| Painted Pumpkin | W-NeRF | 29.86 | 0.606 |

| RGB-NeRF | 34.28 | 0.878 | |

| Ours | 41.10 | 0.967 | |

| Cube & Ball | W-NeRF | 29.82 | 0.670 |

| RGB-NeRF | 37.48 | 0.960 | |

| Ours | 37.67 | 0.963 | |

| Stationery | W-NeRF | 30.36 | 0.670 |

| RGB-NeRF | 32.87 | 0.875 | |

| Ours | 39.23 | 0.959 | |

| Woodwork | W-NeRF | 31.12 | 0.664 |

| (w/o fluorescence) | RGB-NeRF | 35.13 | 0.854 |

| Scene | Method | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cube & Ball | Ours | 33.04 | 0.984 |

| (foreground only) | NeRD | 24.06 | 0.813 |

| Method | Number of Images |

|---|---|

| 13 (#1) + 13 (#2) + 13 (#3) + 13 (#4) | |

| Ours | + 13 (#5) + 13 (#6) + 12 (#7) + 12 (#8) |

| + 12 (#9) + 12 (#10) + 12 (#11) + 12 (#12) | |

| W-NeRF | 150 (#3 + #6 + #12) |

| RGB-NeRF | 50 (#3) + 50 (#6) + 50 (#12) |

| Scene | Method | PSNR ↑ | SSIM ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | 30.59 | 0.894 | |

| Painted Pumpkin | W-NeRF | 17.69 | 0.495 |

| RGB-NeRF | 28.52 | 0.759 | |

| Ours | 31.24 | 0.904 | |

| Cube & Ball | W-NeRF | 16.41 | 0.501 |

| RGB-NeRF | 26.23 | 0.728 | |

| Ours | 30.67 | 0.869 | |

| Stationery | W-NeRF | 16.53 | 0.446 |

| RGB-NeRF | 28.52 | 0.759 | |

| Ours | 30.88 | 0.905 | |

| Truck & Bucket | W-NeRF | 17.86 | 0.501 |

| RGB-NeRF | 27.31 | 0.728 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shi, L.; Matsufuji, K.; Yoshida, M.; Kawahara, R.; Okabe, T. FluoNeRF: Fluorescent Novel-View Synthesis Under Novel Light Source Colors and Spectra. J. Imaging 2026, 12, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010016

Shi L, Matsufuji K, Yoshida M, Kawahara R, Okabe T. FluoNeRF: Fluorescent Novel-View Synthesis Under Novel Light Source Colors and Spectra. Journal of Imaging. 2026; 12(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Lin, Kengo Matsufuji, Michitaka Yoshida, Ryo Kawahara, and Takahiro Okabe. 2026. "FluoNeRF: Fluorescent Novel-View Synthesis Under Novel Light Source Colors and Spectra" Journal of Imaging 12, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010016

APA StyleShi, L., Matsufuji, K., Yoshida, M., Kawahara, R., & Okabe, T. (2026). FluoNeRF: Fluorescent Novel-View Synthesis Under Novel Light Source Colors and Spectra. Journal of Imaging, 12(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010016