Adaptive Normalization Enhances the Generalization of Deep Learning Model in Chest X-Ray Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- It establishes a controlled cross-dataset and cross-architecture evaluation framework for comparing normalization strategies;

- (2)

- It quantifies the impact of normalization choices on cross-domain generalization, training stability, and performance consistency, with particular emphasis on lightweight architectures such as MobileNetV2; and

- (3)

- It provides a statistically grounded comparison using Friedman–Nemenyi and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to clarify when adaptive normalization yields meaningful performance gains over conventional approaches.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. ChestX-ray14

2.1.2. CheXpert

2.1.3. MIMIC-CXR

2.1.4. Pediatric Chest X-Ray (Kermany Dataset)

2.2. Preprocessing Techniques

2.2.1. Normalization

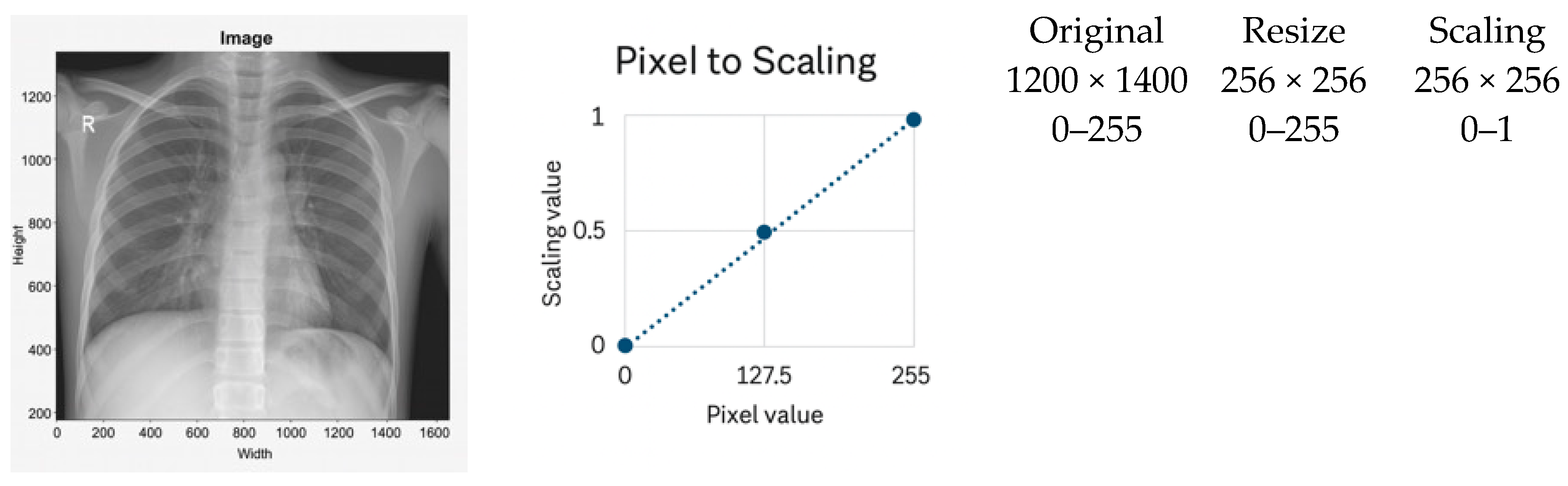

2.2.2. Min–Max Scaling as a Baseline

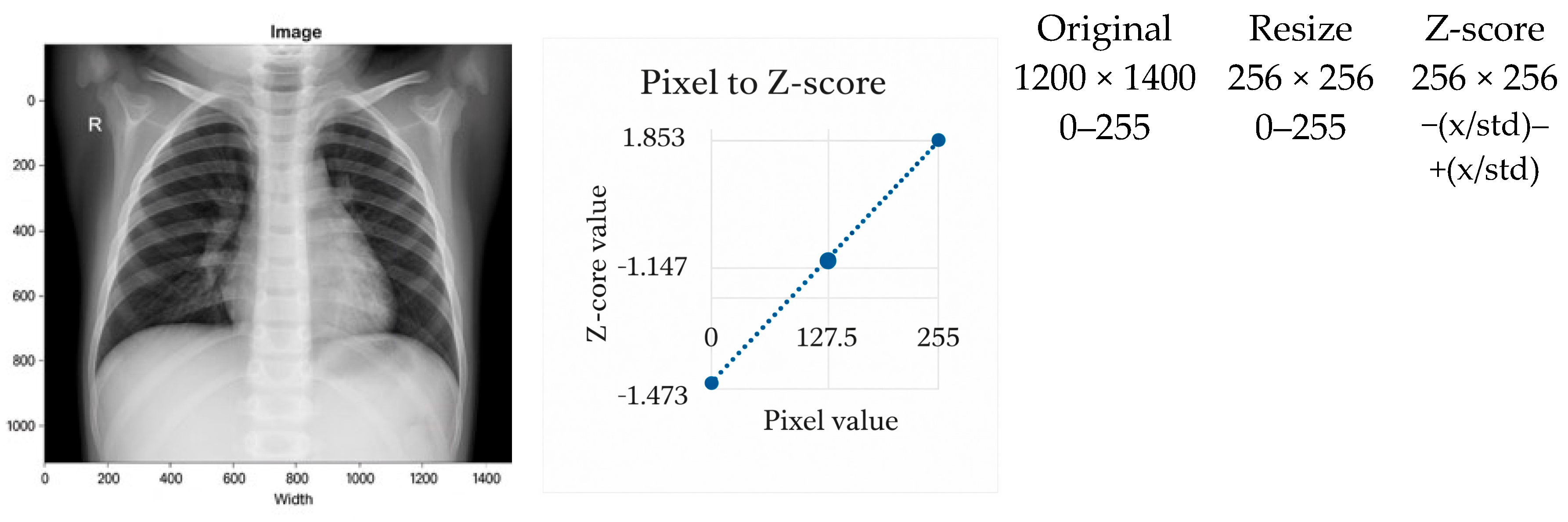

2.2.3. Z-Score Normalization as a Standard Baseline

2.3. Model Architectures

2.4. Region of Interest and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

2.5. Domain Adaptation and Histogram Standardization

2.6. Comparative Analysis of Related Work

2.7. Transformer and Foundation Model Approaches

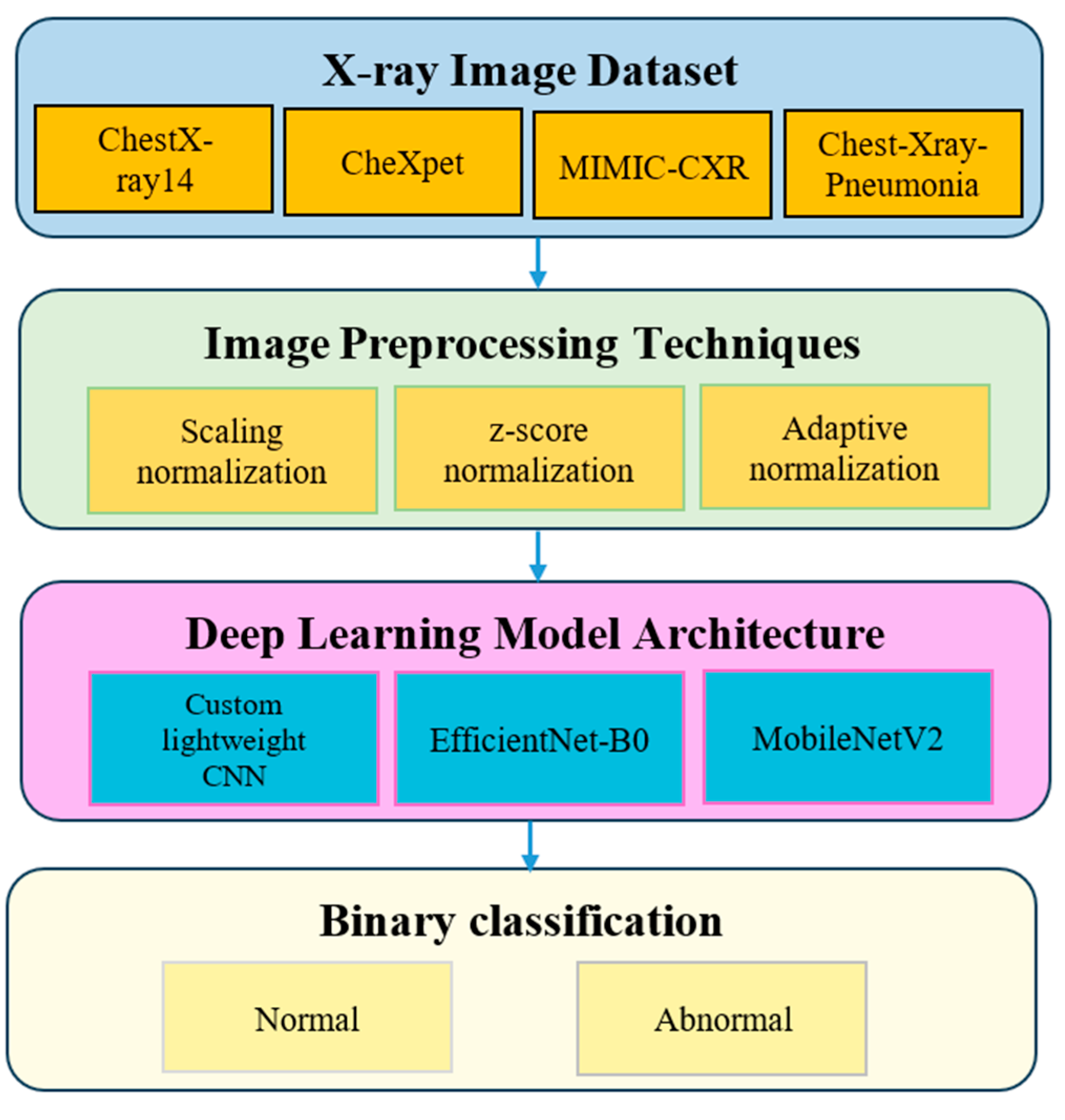

3. Methodology

3.1. Dataset Description

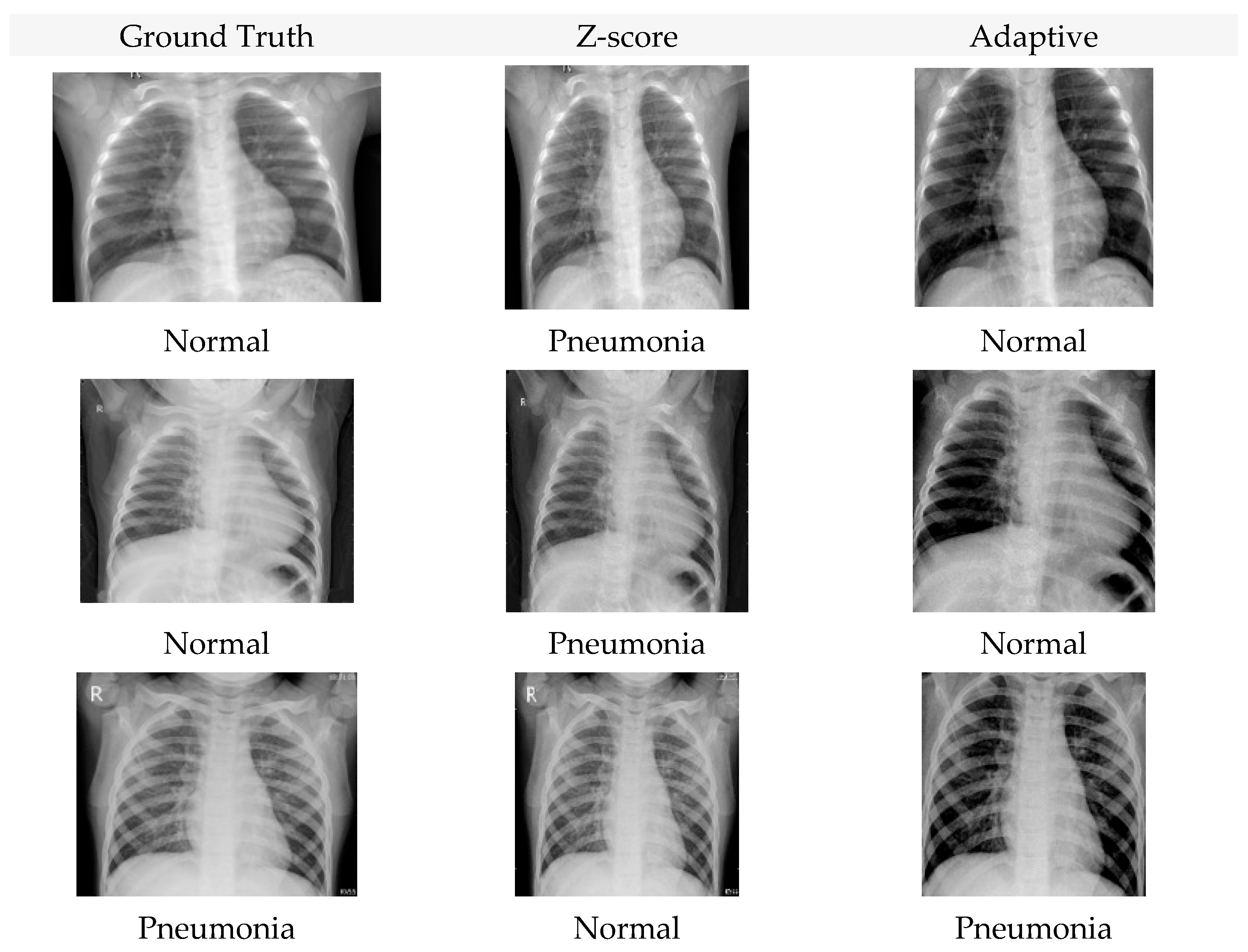

3.2. Image Preprocessing Techniques

3.2.1. Scaling Normalization

- It does not correct local contrast variations and is sensitive to outliers caused by acquisition artifacts or metallic implants.

3.2.2. Z-Score Normalization

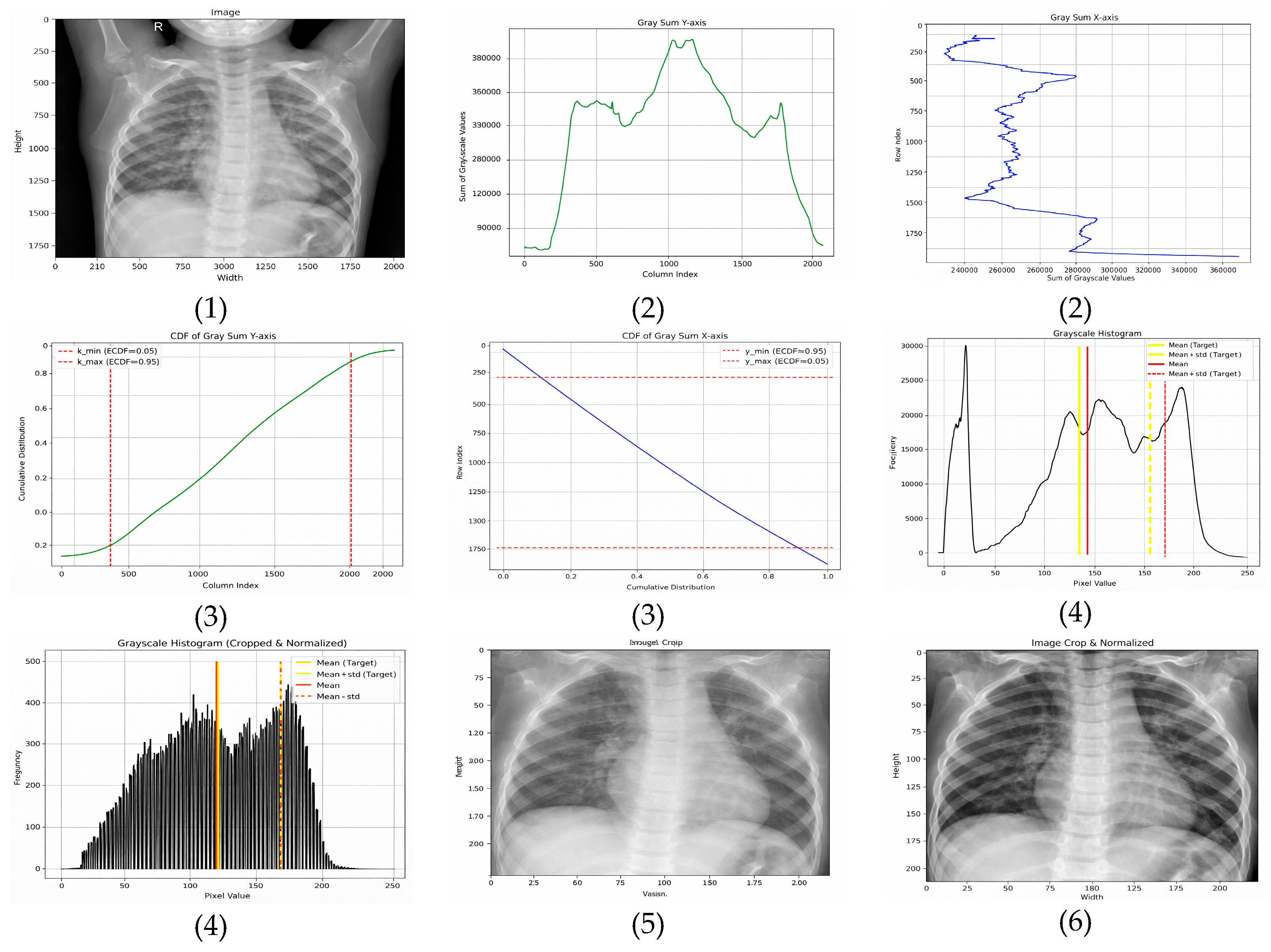

3.2.3. Adaptive Normalization (Proposed Method)

- Horizontal (x-axis)—The ROI is extracted between the 5th and 95th percentiles, removing low-density lateral regions that predominantly contain background. This range is selected based on empirical consistency across adult and pediatric CXRs and aligns with findings that lateral regions contribute minimal diagnostic information.

- Vertical (y-axis)—The ROI is retained between the 15th and 95th percentiles, which excludes anatomical noise above the clavicle and reduces variability caused by neck and shoulder structures.

- Target mean: μtarget = 0.4776 × 255 ≈ 121.8;

- Target standard deviation: σtarget = 0.2238 × 255 ≈ 57.1.

3.2.4. Summary

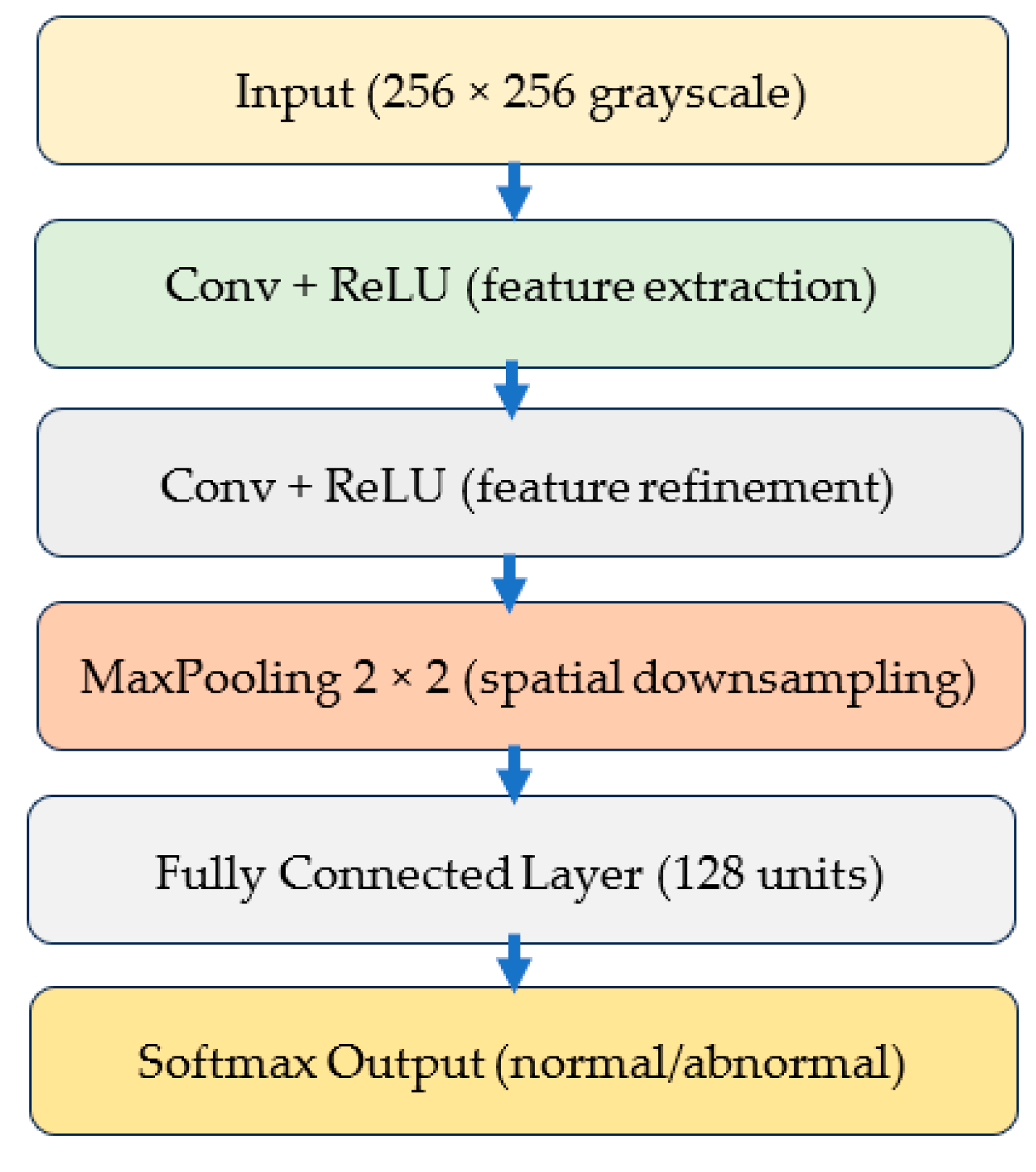

3.3. Deep Learning Model Architecture

3.3.1. Custom Lightweight CNN

3.3.2. EfficientNet-B0

3.3.3. MobileNetV2

3.3.4. Model Training Framework

3.4. Experimental Design

3.4.1. Training Hyperparameters

3.4.2. Data Augmentation

3.4.3. Training Workflow Pseudocode

| Algorithm 1. Training Workflow for CXR Classification | ||

| Input | ||

| Preprocessed training images | ||

| Preprocessed validation images | ||

| Neural network model M | ||

| Hyperparameters from Table 3 | ||

| Output | ||

| Trained model parameters | ||

| Procedure | ||

| Initialize model M with random weights | ||

| For each epoch in the allowed maximum number of epochs | ||

| Set model M to training mode | ||

| For each batch in the training dataset | ||

| Load batch images and labels | ||

| Perform forward pass to obtain predictions | ||

| Compute cross entropy loss | ||

| Compute gradients through backpropagation | ||

| Update model parameters using the Adam optimizer | ||

| End batch loop | ||

| Set model M to evaluation mode | ||

| Compute accuracy and F1 score on the validation dataset | ||

| End epoch loop | ||

| Return | ||

| The final trained model M | ||

3.5. Evaluation Metrics and Performance Formulas

3.5.1. Accuracy

3.5.2. F1-Score

3.5.3. Sensitivity and Specificity

3.6. Statistical Significance Testing

4. Experimental Results

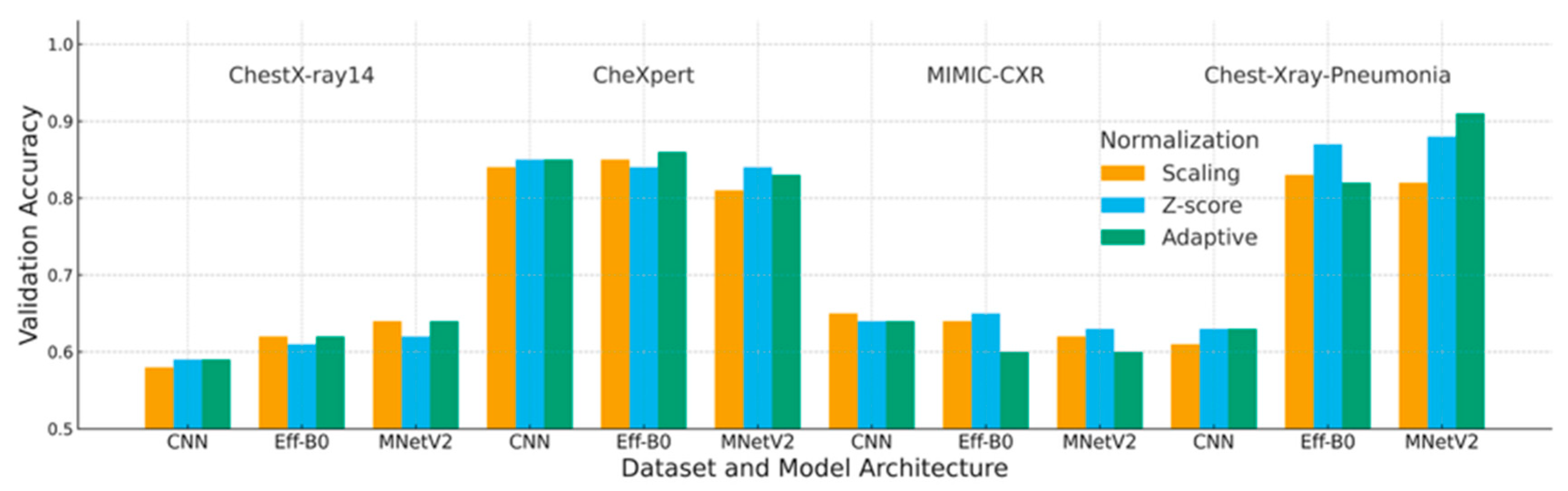

4.1. Accuracy Analysis

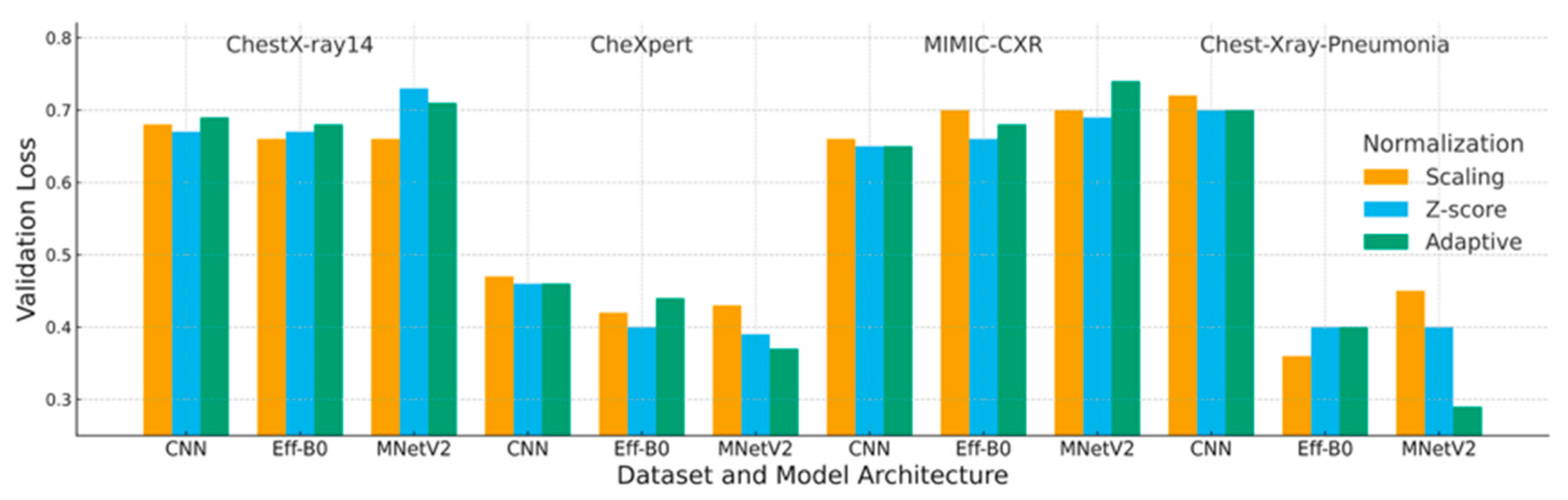

4.2. Loss Analysis

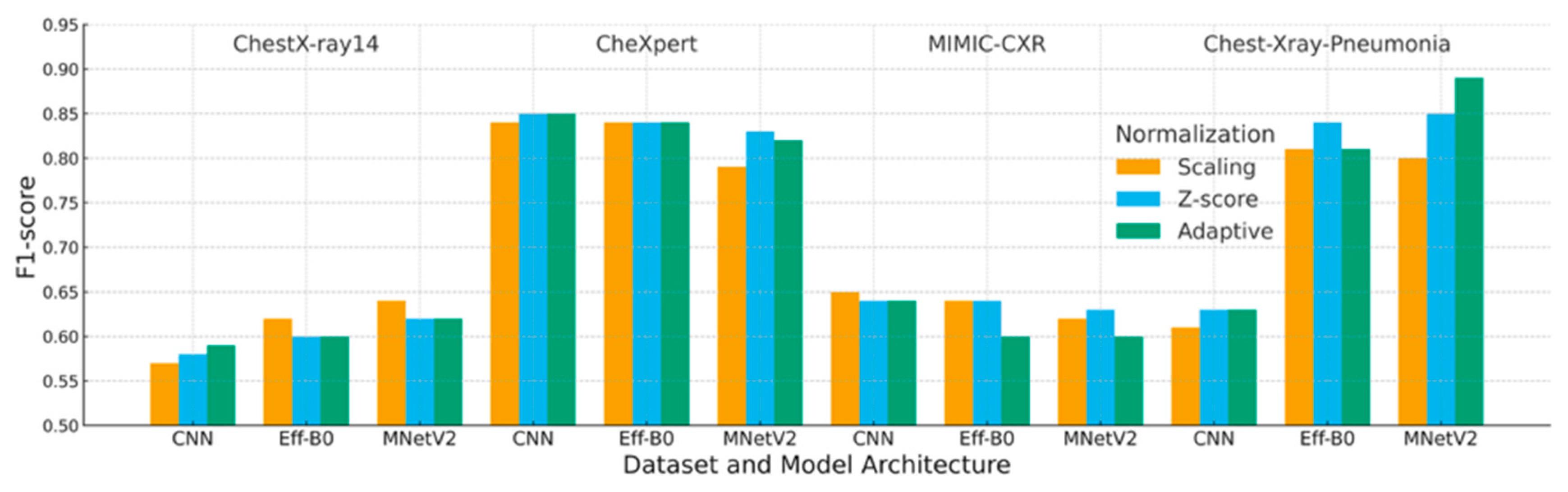

4.3. F1-Score Analysis

4.4. Ablation Study: Effect of Cropping and Histogram Standardization

4.5. Interaction Between Architecture and Normalization

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

References

- Oh, Y.; Park, S.; Ye, J.C. Deep Learning COVID-19 Features on CXR Using Limited Training Data Sets. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 2688–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmavathi, V.; Ganesan, K. Metaheuristic Optimizers Integrated with Vision Transformer Model for Severity Detection and Classification via Multimodal COVID-19 Images. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, B.; Salman, O.K.M. Detection of COVID-19 Disease in Chest X-Ray Images with Capsul Networks: Application with Cloud Computing. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2021, 33, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, S.H.; Saif, M.; Batool, A.; Sohail, A.; Khan, M.W. A Survey of Deep Learning Techniques for the Analysis of COVID-19 and Their Usability for Detecting Omicron. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2024, 36, 1779–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marikkar, U.; Atito, S.; Awais, M.; Mahdi, A. LT-ViT: A Vision Transformer for Multi-Label Chest X-Ray Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; pp. 2565–2569. [Google Scholar]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Irvin, J.; Zhu, K.; Yang, B.; Mehta, H.; Duan, T.; Ding, D.; Bagul, A.; Ball, R.L.; Langlotz, C.; et al. CheXNet: Radiologist-Level Pneumonia Detection on Chest X-Rays with Deep Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioğlu, A. The Effect of Feature Normalization Methods in Radiomics. Insights Imaging 2024, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayed, M.E.; Islam, S.M.S.; Niha, S.I.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. Deep Learning for Medical Image Segmentation: State-of-the-Art Advancements and Challenges. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 47, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Bai, H.; Sun, J.; Cheng, C.; Li, X. LPAdaIN: Light Progressive Attention Adaptive Instance Normalization Model for Style Transfer. Electronics 2022, 11, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuKaraki, A.; Alrawashdeh, T.; Abusaleh, S.; Alksasbeh, M.Z.; Alqudah, B.; Alemerien, K.; Alshamaseen, H. Pulmonary Edema and Pleural Effusion Detection Using EfficientNet-V1-B4 Architecture and AdamW Optimizer from Chest X-Rays Images. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 80, 1055–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, T.; Park, J.; Raj, H.; Jabbar, M.S.; Abebaw, Z.D.; Lee, J.; Van, C.C.; Kim, H.; Shin, D. Pulmonary Abnormality Screening on Chest X-Rays from Different Machine Specifications: A Generalized AI-Based Image Manipulation Pipeline. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2023, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangkhamhan, T. Adaptive Chaotic Satin Bowerbird Optimisation Algorithm for Numerical Function Optimisation. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2021, 33, 719–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.-P.; Zhou, T.; Ji, G.-P.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Shao, L. Inf-Net: Automatic COVID-19 Lung Infection Segmentation From CT Images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 2626–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, D.; Lortkipanidze, M.; Vray, G.; Bozorgtabar, B.; Thiran, J.-P. Self-Attentive Spatial Adaptive Normalization for Cross-Modality Domain Adaptation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 40, 2926–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Luo, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, G. An Uncertainty-Guided Tiered Self-Training Framework for Active Source-Free Domain Adaptation in Prostate Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.02893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, S.; Devi, R.; Mat Isa, N.A. Optimized Exposer Region-Based Modified Adaptive Histogram Equalization Method for Contrast Enhancement in CXR Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin, J.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ko, M.; Yu, Y.; Ciurea-Ilcus, S.; Chute, C.; Marklund, H.; Haghgoo, B.; Ball, R.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. CheXpert: A Large Chest Radiograph Dataset with Uncertainty Labels and Expert Comparison. In Proceedings of the 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2019), Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 590–597. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; Deng, C.; Mark, R.G.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR, a de-Identified Publicly Available Database of Chest Radiographs with Free-Text Reports. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Khandakar, A.; Islam, K.R.; Islam, K.F.; Mahbub, Z.B.; Kadir, M.A.; Kashem, S. Transfer Learning with Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for Pneumonia Detection Using Chest X-Ray. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lin, Z.Q.; Wong, A. COVID-Net: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases from Chest X-Ray Images. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazda, M.; Plavka, J.; Gazda, J.; Drotár, P. Self-Supervised Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Chest X-Ray Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 151972–151982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ş.; Turalı, M.Y.; Çukur, T. HydraViT: Adaptive Multi-Branch Transformer for Multi-Label Disease Classification from Chest X-Ray Images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2025, 100, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, A.; Nunoo-Mensah, H.; Tchao, E.T.; Agbemenu, A.S.; Adjei, P.E.; Acheampong, F.A.; Kponyo, J.J. Deep Learning for Efficient High-Resolution Image Processing: A Systematic Review. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermany, D.S.; Goldbaum, M.; Cai, W.; Valentim, C.C.S.; Liang, H.; Baxter, S.L.; McKeown, A.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Identifying Medical Diagnoses and Treatable Diseases by Image-Based Deep Learning. Cell 2018, 172, 1122.e9–1131.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.S.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Liu, X.; Dai, J.; Chan, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J.; Kong, W.; Lu, Z.; et al. COVID-19 Detection via Ultra-Low-Dose X-Ray Images Enabled by Deep Learning. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oltu, B.; Güney, S.; Yuksel, S.E.; Dengiz, B. Automated Classification of Chest X-Rays: A Deep Learning Approach with Attention Mechanisms. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, M.M.; Rehmani, M.H.; O’Reilly, R. Addressing the Intra-Class Mode Collapse Problem Using Adaptive Input Image Normalization in GAN-Based X-Ray Images. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, Scotland, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 2049–2052. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, T.; Hafiz, M.S.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. A Systematic Review of Deep Learning Data Augmentation in Medical Imaging: Recent Advances and Future Research Directions. Healthc. Anal. 2024, 5, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, J.C.; Dewey, B.E.; Carass, A.; Prince, J.L. Evaluating the Impact of Intensity Normalization on MR Image Synthesis. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2019: Image Processing, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–21 February 2019; Angelini, E.D., Landman, B.A., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; Volume 10949, p. 109493H. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Belongie, S. Arbitrary Style Transfer in Real-Time with Adaptive Instance Normalization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1510–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Waisy, A.S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Al-Fahdawi, S.; Maashi, M.S.; Garcia-Zapirain, B.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Mostafa, S.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Le, D.-N. COVID-DeepNet: Hybrid Multimodal Deep Learning System for Improving COVID-19 Pneumonia Detection in Chest X-Ray Images. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 67, 2409–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bin Azhar, A.N.; Sani, N.S.; Wei, L.L.X. Enhancing COVID-19 Detection in X-Ray Images Through Deep Learning Models with Different Image Preprocessing Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2025, 16, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toğaçar, M.; Ergen, B.; Cömert, Z. COVID-19 Detection Using Deep Learning Models to Exploit Social Mimic Optimization and Structured Chest X-Ray Images Using Fuzzy Color and Stacking Approaches. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 121, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanida, T.; Dasygenis, M. A Novel Lightweight CNN for Chest X-Ray-Based Lung Disease Identification on Heterogeneous Embedded System. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 4756–4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Wichtmann, B.D.; Zhao, W.; Maurer, A.; Hesser, J.; Attenberger, U.I.; Schad, L.R.; Zöllner, F.G. Comparison of Image Normalization Methods for Multi-Site Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani Baker, Q.; Hammad, M.; Al-Smadi, M.; Al-Jarrah, H.; Al-Hamouri, R.; Al-Zboon, S.A. Enhanced COVID-19 Detection from X-Ray Images with Convolutional Neural Network and Transfer Learning. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. V EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. arXiv 2011, arXiv:2104.00298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.; Terhljan, N.; Chung, A.G.; Zhao, A.; Surana, S.; Aboutalebi, H.; Gunraj, H.; Sabri, A.; Alaref, A.; Wong, A. COVID-Net CXR-2: An Enhanced Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases from Chest X-Ray Images. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 861680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipsen, R.H.H.M.; Maduskar, P.; Hogeweg, L.; Melendez, J.; Sánchez, C.I.; van Ginneken, B. Localized Energy-Based Normalization of Medical Images: Application to Chest Radiography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunraj, H.; Wang, L.; Wong, A. COVIDNet-CT: A Tailored Deep Convolutional Neural Network Design for Detection of COVID-19 Cases From Chest CT Images. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 608525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwiboon, N. Efficient and Lightweight CNN Model for COVID-19 Diagnosis from CT and X-Ray Images Using Customized Pruning and Quantization Techniques. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 13059–13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, T.; Talo, M.; Yildirim, E.A.; Baloglu, U.B.; Yildirim, O.; Rajendra Acharya, U. Automated Detection of COVID-19 Cases Using Deep Neural Networks with X-Ray Images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 121, 103792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-T.; Tsao, C.-Y. Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network for Chest X-Ray Images Classification. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage Chehade, A.; Abdallah, N.; Marion, J.-M.; Hatt, M.; Oueidat, M.; Chauvet, P. Reconstruction-Based Approach for Chest X-Ray Image Segmentation and Enhanced Multi-Label Chest Disease Classification. Artif. Intell. Med. 2025, 165, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Lin, R.; Du, W.; Tavares, A.; Liang, Y. Explainable Hybrid Transformer for Multi-Classification of Lung Disease Using Chest X-Rays. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Gao, J.; Carey, K.A.; Edelson, D.P.; Afshar, A.; Garrett, J.W.; Chen, G.; Afshar, M.; Churpek, M.M. Comparison of Deep Learning Approaches Using Chest Radiographs for Predicting Clinical Deterioration: Retrospective Observational Study. JMIR AI 2025, 4, e67144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirugwe, A.; Tamale, L.; Nyirenda, J. Improving Tuberculosis Detection in Chest X-Ray Images Through Transfer Learning and Deep Learning: Comparative Study of Convolutional Neural Network Architectures. JMIRx Med 2025, 6, e66029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boecking, B.; Usuyama, N.; Bannur, S.; Castro, D.C.; Schwaighofer, A.; Hyland, S.; Wetscherek, M.; Naumann, T.; Nori, A.; Alvarez-Valle, J.; et al. Making the Most of Text Semantics to Improve Biomedical Vision–Language Processing. In Proceedings of the ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Pang, J.; Gotway, M.B.; Liang, J. A Fully Open AI Foundation Model Applied to Chest Radiography. Nature 2025, 643, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Agarwal, D.; Sun, J. MedCLIP: Contrastive Learning from Unpaired Medical Images and Text. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; Goldberg, Y., Kozareva, Z., Zhang, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 3876–3887. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Miura, Y.; Manning, C.D.; Langlotz, C. Contrastive Learning of Medical Visual Representations from Paired Images and Text. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning in Health Care, Virtual, 7–8 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, H.; Khan, A.; Nepal, N.; Khan, F.; Moon, Y.-K. Deep Learning Approaches for Chest Radiograph Interpretation: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Kabir, M.A. PDCOVIDNet: A Parallel-Dilated Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Detecting COVID-19 from Chest X-Ray Images. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 2020, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, P.; Majumder, R.; Mandal, A.; Dey, S.; Mandal, M. A Computational Study to Assess the Polymorphic Landscape of Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 Promoter and Its Effects on Transcriptional Activity. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 145, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Bougourzi, F.; Dornaika, F.; Distante, C.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. D-TrAttUnet: Toward Hybrid CNN-Transformer Architecture for Generic and Subtle Segmentation in Medical Images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 176, 108590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A Survey on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sodha, V.; Pang, J.; Gotway, M.B.; Liang, J. Models Genesis. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 67, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zuo, W.; Shan, S. Shift-Net: Image Inpainting via Deep Feature Rearrangement. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2018), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Matsushita, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chicco, D.; Jurman, G. The Advantages of the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) over F1 Score and Accuracy in Binary Classification Evaluation. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demšar, J. Statistical Comparisons of Classifiers over Multiple Data Sets. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2006, 7, 1–30. Available online: https://www.jmlr.org/papers/v7/demsar06a.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

| A. Deep Learning Architectures for CXR/CT Classification. | ||||||||||

| Authors | Model/Architecture | Technique/Approach | Dataset | Metrics | Key Highlights | |||||

| [13] | Inf-Net | Semi-supervised infection segmentation with reverse and edge attention | COVID-SemiSeg | Dice, Sens., Spec. | First semi-supervised CT infection segmentation dataset and model | |||||

| [1] | ResNet-18 + CAM | Patch-based semi-supervised CXR learning | COVIDx, RSNA | Accuracy, AUC | Strong performance with limited labeled CXRs | |||||

| [19] | VGG19, DenseNet, Inception | Transfer learning with augmentation | Chest X-ray Pneumonia | Accuracy, F1 | Demonstrated impact of augmentation and TL | |||||

| [40] | COVIDNet-CT | COVID-specific CNN | COVIDx-CT | Accuracy, Sens. | High-performing CT-based classifier | |||||

| [42] | DarkCOVIDNet | CNN for binary/multi-class COVID-19 detection | COVID-19 X-ray | Accuracy, F1 | Early high-performing CXR classifier | |||||

| [33] | MobileNetV2 + SqueezeNet | Fuzzy preprocessing with metaheuristic optimization | COVID (Cohen) | Accuracy, F1 | Fusion of deep and fuzzy features | |||||

| [20] | COVID-Net | Machine-designed CNN | COVIDx | Accuracy, Sens. | Transparent, explainable CNN design | |||||

| [31] | InceptionResNetV2 + BiLSTM | Hybrid deep features (GLCM/LBP + CNN) | COVIDx | Accuracy, AUC | Outperformed CNN-only baselines | |||||

| [5] | LT-ViT | Label-token vision transformer | CheXpert, CXR14 | AUC | Interpretable ViT via explicit label tokens | |||||

| [11] | ResNet-based | Style and histogram normalization pipeline | Multi-hospital CXR | AUC, Accuracy | Cross-device robust AI pipeline | |||||

| [10] | EfficientNet-B4 | CLAHE + augmentation | CXR14, PadChest | F1, AUC | High robustness with strong AUC | |||||

| [34] | Lightweight CNN | Embedded-optimized CNN | CXR14 | Accuracy, Sens. | Real-time classification on heterogeneous devices | |||||

| [43] | Lightweight CNN | Edge-oriented deployment | CXR14 | Accuracy, Precision, Sens. | Ultra-light model with near-ResNet performance | |||||

| [44] | Reconstruction-based CNN + XGBoost | GAN reconstruction, segmentation + radiomics | CXR14 | AUC, Accuracy | Pathology-aware reconstruction and classification | |||||

| [45] | EHTNet (Hybrid CNN–Transformer) | Explainable hybrid transformer for lung diseases | CXR14 | Accuracy, AUC | Hybrid CNN–ViT architecture with attention-based explanations | |||||

| [2] | ViT + Metaheuristics | ViT optimized with PSO/GWO for severity and multimodal fusion | CXR + CT | Accuracy, Sens. | ViT tuned via metaheuristic optimizers | |||||

| This Study | CNN, EfficientNet-B0, MobileNetV2 | Adaptive normalization (CDF cropping + histogram standardization) | CXR14, CheXpert, MIMIC-CXR, Pediatric | Accuracy, F1 | A systematic cross-dataset, cross-architecture benchmarking of normalization strategies under controlled sampling. | |||||

| B. Normalization and Preprocessing Approaches | ||||||||||

| Authors | Method | Dataset | Metrics | Key Highlights | ||||||

| [39] | Localized energy-based normalization | Chest radiography | Sens., Spec. | Foundational localized contrast standardization for CXRs | ||||||

| [30] | Adaptive Instance Normalization (AdaIN) | Natural + style datasets | Style metrics | Basis for modern adaptive, style-aware normalization | ||||||

| [14] | Self-attentive spatial adaptive normalization | Radiography/CT | Dice, IoU | Spatially adaptive normalization for cross-modality DA | ||||||

| [11] | Histogram + style normalization pipeline | Multi-hospital CXR | Accuracy, AUC | Reduced device-driven variation across machines | ||||||

| [16] | Exposure-region adaptive histogram equalization | CXR | PSNR, entropy | Modern exposure-region contrast enhancement method | ||||||

| This Study | CDF-guided cropping + histogram standardization | CXR14, CheXpert, MIMIC-CXR | Accuracy, F1 | Joint ROI and intensity standardization for multi-source CXRs | ||||||

| C. Data Augmentation and Transferability Studies | ||||||||||

| Authors | Focus | Dataset(s) | Metrics | Key Highlights | ||||||

| [28] | Systematic review of data augmentation in medical imaging | Multi-modal medical | Narrative | Identified geometric transforms as backbone of medical DL augmentation | ||||||

| [46] | Augmentation for clinical deterioration prediction | CXR | Accuracy, AUC | Showed rotation and flipping improve robustness in clinical prediction | ||||||

| [47] | Augmentation for TB/COVID robustness | Multiple CXR datasets | AUC, Precision | Brightness and gamma augmentations improve cross-dataset transferability | ||||||

| [33] | Fuzzy preprocessing + augmentation | CXR (COVID) | Accuracy, F1 | Demonstrated that fuzzy preprocessing with augmentation enhances performance | ||||||

| Dataset | Image Count | Images Used | Patients | Original Labels/Classes | Classes Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChestX-ray14 | 112,120 | 16,000 | 30,805 | 14 | 2 |

| CheXpert | 224,316 | 16,000 | 65,240 | 14 | 2 |

| MIMIC-CXR | 377,110 | 16,000 | 227,827 | 14 | 2 |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | 5863 | 5863 | Pediatric only | 3 | 2 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning rate | 1 × 10−4 |

| Batch size | 100 |

| Maximum epochs | 20 |

| Weight decay | 1 × 10−5 |

| Train validation split | 80%/20% |

| Random seeds | 42, 123, 456 |

| Loss function | Cross entropy |

| Comparison | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive vs. Z-score | 0.0078 | Significant (p < 0.01) |

| Adaptive vs. Scaling | 0.0039 | Significant (p < 0.01) |

| Z-score vs. Scaling | 0.0781 | Not significant (p > 0.05) |

| Dataset | Deep Learning | Scaling | Z-Score | Adaptive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChestX-ray14 | CNN | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.62 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.64 | |

| CheXpert | CNN | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.86 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.83 | |

| MIMIC-CXR | CNN | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.60 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.60 | |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | CNN | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.82 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.91 |

| Dataset | Preprocessing | Scaling | Z-Score | Adaptive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChestX-ray14 | CNN | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.68 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.71 | |

| CheXpert | CNN | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.44 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.37 | |

| MIMIC-CXR | CNN | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.68 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.74 | |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | CNN | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.40 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.29 |

| Dataset | Preprocessing | Scaling | Z-Score | Adaptive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChestX-ray14 | CNN | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.59 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.60 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.62 | |

| CheXpert | CNN | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.82 | |

| MIMIC-CXR | CNN | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.60 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.60 | |

| Chest-Xray-Pneumonia | CNN | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.81 | |

| MobileNetV2 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.89 |

| Method | Cropping | Histogram | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-score | ✗ | ✗ | 0.85 |

| Cropping only | ✓ | ✗ | 0.86 |

| Histogram only | ✗ | ✓ | 0.88 |

| Adaptive | ✓ | ✓ | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Singthongchai, J.; Wangkhamhan, T. Adaptive Normalization Enhances the Generalization of Deep Learning Model in Chest X-Ray Classification. J. Imaging 2026, 12, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010014

Singthongchai J, Wangkhamhan T. Adaptive Normalization Enhances the Generalization of Deep Learning Model in Chest X-Ray Classification. Journal of Imaging. 2026; 12(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingthongchai, Jatsada, and Tanachapong Wangkhamhan. 2026. "Adaptive Normalization Enhances the Generalization of Deep Learning Model in Chest X-Ray Classification" Journal of Imaging 12, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010014

APA StyleSingthongchai, J., & Wangkhamhan, T. (2026). Adaptive Normalization Enhances the Generalization of Deep Learning Model in Chest X-Ray Classification. Journal of Imaging, 12(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging12010014