Abstract

Understanding the composition of disposed municipal solid waste (MSW) and recyclables can lead to better waste management. New York State (United States) has never had a state-wide waste characterization sorting program. In 2021, sampling was conducted at 11 locations, representing 25% of the state population outside of New York City. Twenty-three tonnes from 173 discrete samples were sorted into 41 categories. The resulting data were analyzed by single constituent approaches and more novel multivariate distance techniques. The analyses found that disposed MSW was 22.8% paper, 20.5% food, and 16.8% plastics. Recyclable paper and glass–metal–plastic containers were 18.2% (11.7% paper, 6.5% containers) and yard waste was 6.5%, meaning about 25% of the disposed MSW could have been recovered. Multivariate analysis determined that the disposed MSW was similar to that from other United States jurisdictions such as Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, New York City, and Syracuse (NY), and different from California and United States Environmental Protection Agency model data. Recyclables composition was different from disposed MSW composition. Dual-stream recyclables were sorted better than single-stream recyclables. Corrugated cardboard was the most common paper recyclable and plastics were the most common container recyclable. The data are being used to help guide planning for an expected packaging extended producer responsibility law for the State.

1. Introduction

Information about the composition of solid waste is useful to determine better management strategies [1,2,3]. Counting and defining the content of municipal solid waste (MSW) are surprisingly difficult tasks for something that is tangible and is created and managed by almost everyone every day [4].

In the 1970s the United States (US) Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decided that the most practical means to count the amount of garbage in the US would be to model it using an “input-output” model because there were too many disposal sites to survey and because many of the disposal sites did not measure what they disposed [5]. An input-output model determines the product of a system by carefully measuring what goes into the system and estimating how long it remains there [6]. EPA modelers used data on the production of physical goods in the country, subtracted exports, and added imports to create the model input, assigned all the goods a lifespan (distinguishing between durable and non-durable products), used a limited set of materials to describe all of the goods, and thereby produced as outputs of the model a waste stream size and associated composition. Therefore, a byproduct of counting discards for a particular year was that the model also determined the composition of those wastes [5,7] (latest output [3]). However, it has been shown that the EPA model almost certainly did not count the US waste stream accurately [4] (the State of Garbage reports by BioCycle and the Themelis research group, last example [8]) [9,10]. Because the base tonnage is incorrect, it follows that perhaps the waste composition data are not accurate as well. Researchers studying food [11,12], plastics [13], and paper [14] have found different amounts and/or percentages than EPA for these individual constituents. A more comprehensive assessment that evaluated six waste stream components found differences in the amount of paper in the discarded waste stream as reported by EPA, but the five other constituents (glass, metal, plastics, food, and yard wastes) were determined to be approximately the same [15]. Another recent evaluation of New York City (NYC) waste composition conducted by many of the researchers of this study, which compared the NYC data to other data sets, including EPA data, found that EPA data for disposed paper and plastics percentages were not similar to regressions on the other 88 data sets, although there was some reasonable agreement on food waste percentages [16].

Most of these studies that conflict with EPA have compared the EPA model output to physical analyses of waste streams (waste sorts); there have been at least 215 such studies conducted at the state, county, and municipality scale across the US since 1987 [16]. There is standard guidance on how to conduct waste sort studies [17] but the methods sections of the waste characterization sort study reports reveal that all vary from the guidance in some ways. The diversity of methods can become an issue in the comparability of these studies. They are also particular to the time and place they were conducted, and the waste system processes under which the wastes are managed are understood to affect the composition of the resulting waste stream. These elements limit their generality and the value of the generated data for projections or other forecasts.

There are other ways to measure waste stream composition. Hall et al. [12] used food production data and then subtracted food consumed through metabolic processes, stored in weight gain, and managed as sewage to determine the balance (which must have been disposed of or perhaps fed to animals). Often base generation data are determined through composition studies or surveys, and then relevant unit generation data are used to create estimates of waste creation (commonly used units are sales, floor area, and the number of employees for businesses, or populations or household counts for residential wastes) [18,19]. The state of Florida developed a baseline measure of its counties’ waste streams by modifying EPA data [20] and then used its own modeling approach based on some econometric, population change, recycling, and disposal data to project how the generated and disposed waste streams have changed over time [21]. Recently there have been some artificial intelligence (machine learning) modeling endeavors that generate waste stream composition and size estimates [22,23].

In 2018, we were approached by New York State (NYS) regulators to help understand the composition of the New York waste stream. These regulators had created an estimator of waste composition for rural, suburban, and urban regions by combining waste characterization sort data from studies they believed were relevant for New York state conditions but understood that other approaches might be useful. NYS is the fourth largest state (by population) and never had a state-wide waste composition sampling program. We proposed to sort wastes at various locations around the state. We began in fall 2019 with a small survey of recycling facilities in response to worries generated by the National Sword recyclables ban in China [24]; then, the program went on hiatus in 2020 through May 2021 due to the COVID pandemic. Here, we report on the first year’s state-wide sampling effort from the summer and fall of 2021. We use a novel multivariate approach to generate wholistic comparisons across sampling sites and to other data sets [16] and use standard single-parameter analyses to understand the system similarities and differences more carefully. We found that NYS MSW (that is, disposed MSW) is generally similar in composition to two of three state-wide composition studies made in 2020–2021 but is different from EPA model estimates, and that the disposed MSW can be distinguished from recyclables separated for recovery. Major drivers of the differences and similarities were corrugated cardboard and recyclable paper percentages, along with recyclable plastics and food waste percentages. A closer examination of disposed MSW composition differences distinguished particular systems within NYS from each other and from data selected for comparison purposes.

2. Results and Discussion

Raw data (weight and percentage data) were stored and are available in [25]. Percentage data converted into the 16-variable data sets are available in the Supplementary Materials: disposed MSW (Table S1), dual-stream container recyclables (Table S2), dual-stream paper recyclables (Table S3), and single-stream recyclables (Table S4). In New York State (and in the US, generally) curbside recyclables collection follows two general models: separate collection of paper recyclables and glass–metal–plastic container recyclables, most often by different trucks and on different days, which is called “dual-stream” recycling; or, collection of commingled paper and container recyclables, called “single-stream” recycling (see [26] for more details). Comparison and NYS aggregated recyclables data are presented in the recyclables Tables S2–S4; comparison and NYS aggregated data are presented in Table S5 for the disposed MSW data.

2.1. Multivariate Results

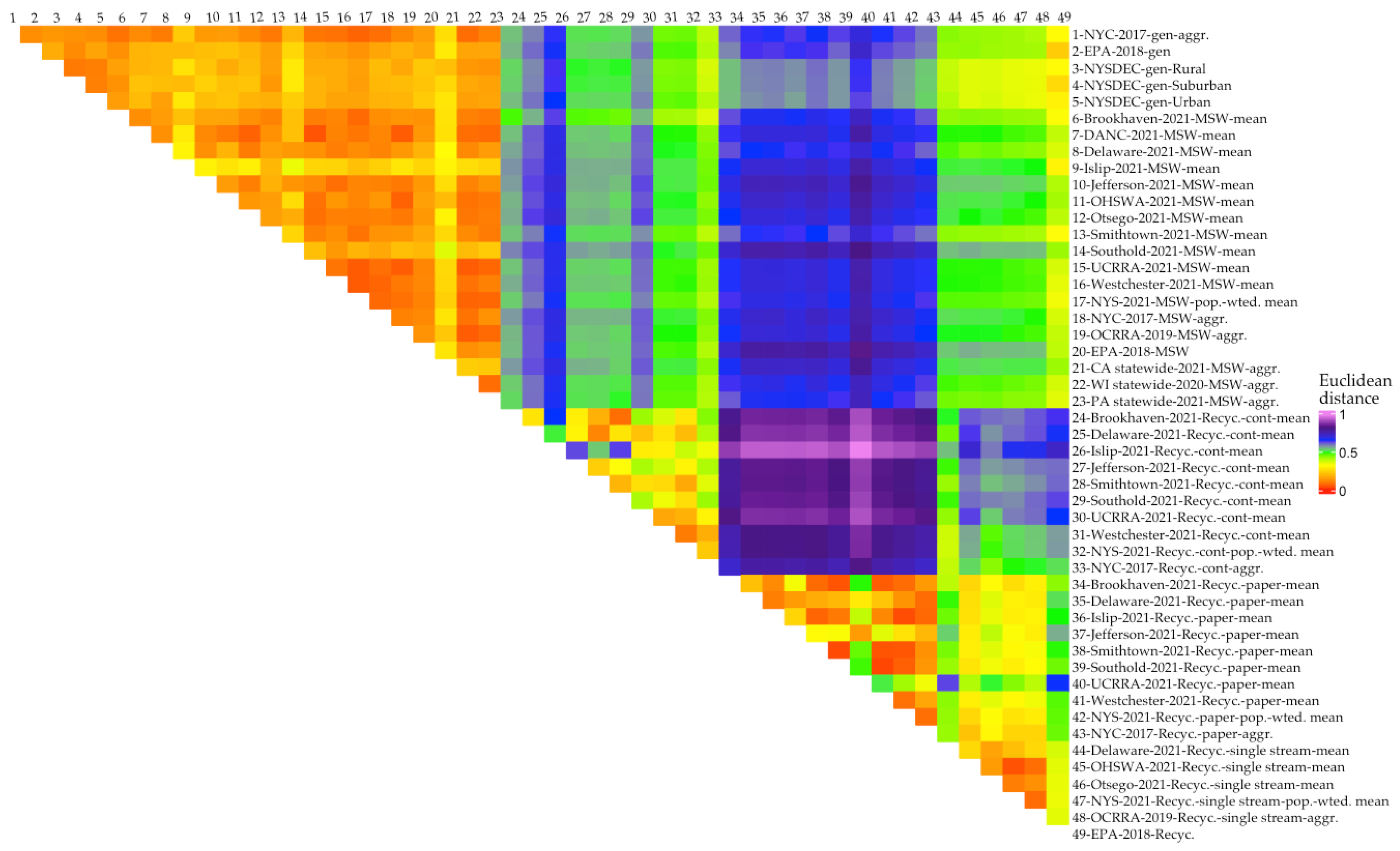

The systems’ multivariate Euclidean distances from each other were determined and organized into a 49 × 49 triangular matrix. In the matrix, moving from top to bottom and left to right, the first five elements (rows and columns 1–5) are “total waste stream” depictions distances (from comparison data groups). The next 11 elements are the distances associated with the disposed MSW sample data from the 2021 NYS sampling effort (columns and rows 6–16). Column and row 17 hold the mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW data distances. The next six elements are distances associated with the comparison disposed MSW data sets (columns and rows 18–23). The next eight elements are the distances for the 2021 NYS data from dual-stream container recyclables samples (columns and rows 24–31); column and row 32 contain the distances for the mean 2021 NYS dual-stream container recyclables data, and column and row 33 are the distances for the comparison data set (2017 NYC dual-stream container recyclables data). The next eight elements are distance data for 2021 NYS dual-stream paper recyclables data (columns and rows 34–41); column and row 42 are the distance data for the mean 2021 NYS dual-stream paper recyclables data, and column and row 43 are the distance data for the comparison data set (2017 NYC dual-stream paper recyclables data). Columns and rows 44–46 are the 2021 NYS single-stream recyclables data sets distance data and column and row 47 contain the distances associated with the mean 2021 NYS single-stream recyclables data set. The final two rows and columns hold distance data from the comparison data sets for single-stream recyclables.

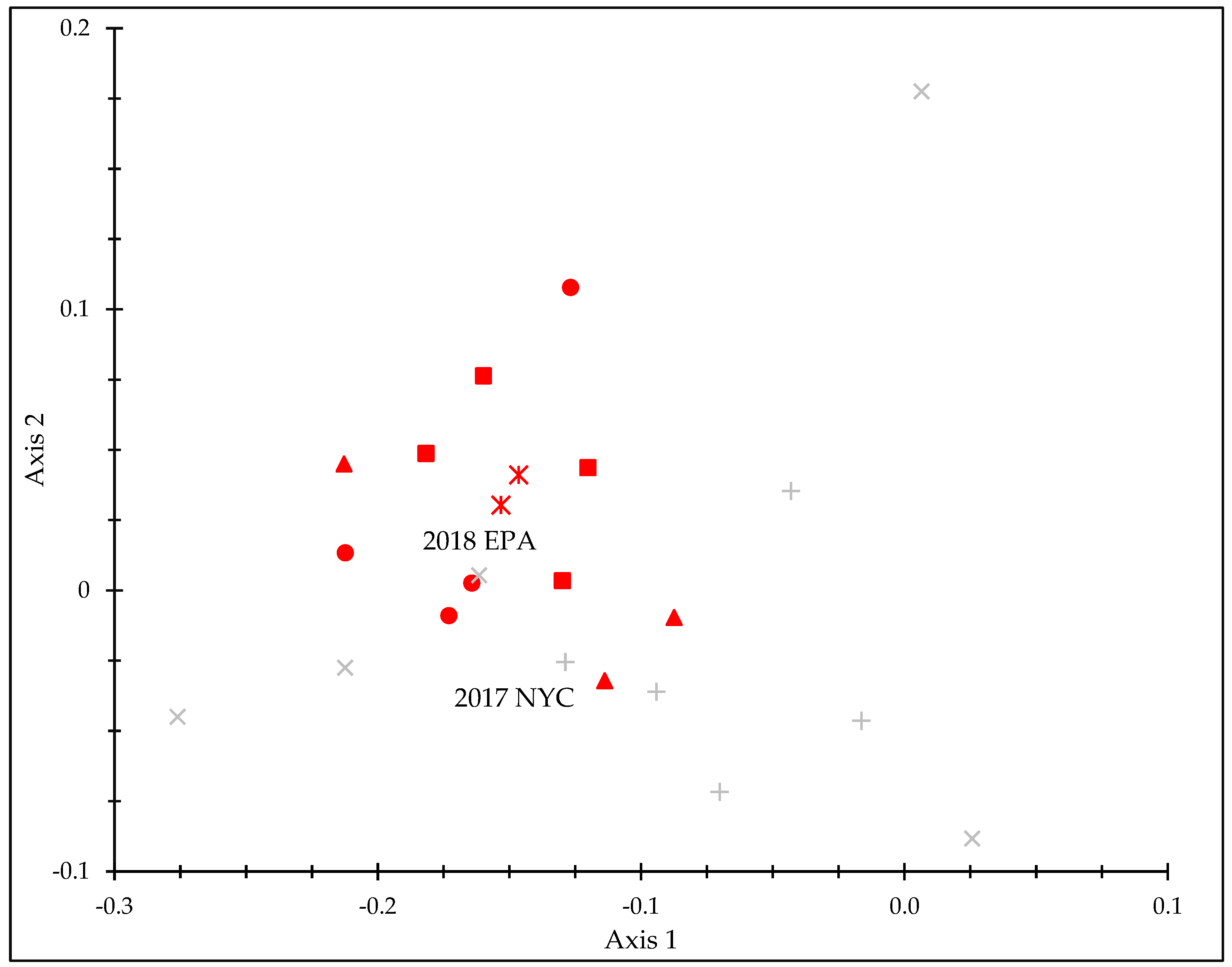

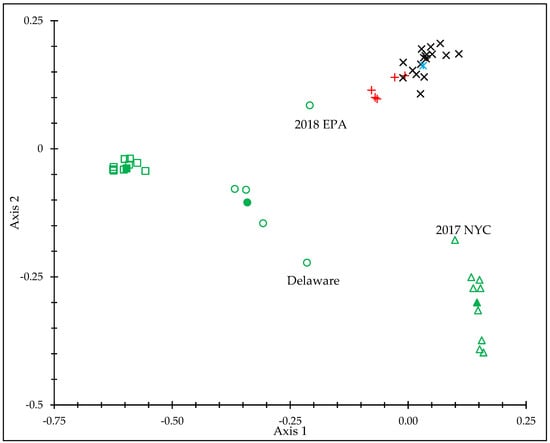

The triangular matrix distances were visualized in a heat map (Figure 1) where colors range from red to violet, with the closest distances in red and farthest distances in violet (analogous to the wavelengths of the visual spectrum). The notable features of Figure 1 are triangular and rectilinear blocks of similar color, indicating that the types of samples established an ordering on the multivariate distance relationships. The color distributions for the triangles and rectangles in the distance heat map are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Heat map of the Euclidean distances between system sample types.

Table 1.

Color distributions for the triangles and rectangles in Figure 1.

2.1.1. Qualitative Analysis of Multivariate Similarities and Differences

Similar Waste Composition Results

There is a large red-orange triangle, with 253 elements of which 236 are red or orange, formed by the intersection of rows-columns 1–23. This conforms to distances among total waste stream and disposed MSW results. The immediate interpretation is the composition of the total waste stream and disposed MSW were all similar for 2021 NYS data and comparison sites.

This triangle can also be interpreted as two smaller triangles and a rectangle. One of the smaller triangles is formed by the intersection of rows-columns 1–5 which conforms to the total waste stream distance measures. All ten of the squares in this triangle were orange (bordering on red). This means they were all similarly close to each other, sharing a common waste composition.

The second smaller triangle is formed by the intersection of rows and columns 6–23, which conforms to the disposed MSW distance measures. There are 153 squares in this triangle; 17 of the squares are red, 126 are orange, and 10 are yellow. The yellow squares, along with lighter orange squares, are associated with the Town of Islip, the Town of Southold, and especially 2021 California data (CA). This indicates they are somewhat farther away from other disposed MSW data sets but that all of these data are generally similar overall.

The rectangle is the intersection of rows 1–5 and columns 6–23. This is the distance relations between the total waste stream data and the disposed MSW data; 83 of the 90 squares are shades of orange, with seven yellow squares. This means that the composition of the total waste stream data sets and disposed MSW data sets are mostly similar.

There is a more mixed red-orange and yellow-green triangle defined by the intersection of rows-columns 34–43, which conforms to distances among dual-stream paper recyclables, and supports an interpretation that the composition of dual-stream paper recyclables data sets is similar to each other. All of the squares are red, orange, or yellow except for four green squares out of a total of nine comparisons involving Ulster County. 16% of the squares were red. Therefore, dual-stream paper recyclables data have good similarities to each other in their overall composition, with the exception of the Ulster County data.

There is a small orange-red triangle defined by the intersection of rows-columns 44–48, which conforms to the distances among the single-stream recyclables 2021 sampling data with one of the two comparison data sets. The interpretation is that the composition of single-stream recyclables are all similar to each other. This group has two red squares, six orange squares, and two yellow squares. All five 2018 EPA recyclables (row-column 49) comparisons are yellow, indicating that the 2018 EPA recyclables were somewhat different in composition from the standard single-stream data sets.

A much less homogenous triangle is defined by the intersection of rows-columns 24–33, which conforms to the distances among the dual-stream container recyclables. Two-thirds of the squares are red or orange, indicating that the composition of some of the dual-stream container data sets is very similar, but other green and blue squares in the triangle determine that some of the data sets are not very similar. Town of Islip dual-stream containers are farthest away overall, with six of nine comparisons being green or blue; Town of Islip is most different from the Town of Brookhaven, Jefferson County, and Town of Southold. Town of Brookhaven, Jefferson County, and 2017 NYC data all have four comparisons that are green or blue. Town of Smithtown has a greater degree of similarity to the other data sets, with only one green comparison, and the 2021 NYS data also only has one green comparison (both to Town of Islip data). Town of Brookhaven-Town of Southold, Delaware County-Town of Smithtown, and Westchester County-2021 NYS data are all closest to each other (red squares).

Dissimilar Waste Composition Results

In Figure 1, there is a violet rectangle defined by the intersection of rows 24–33 and columns 34–43. This rectangle is defined by the distances among the dual-stream container recyclables data sets and the dual-stream paper recyclables data sets, and it shows that the composition of these two recyclables data sets are very different from each other.

There is a mostly blue rectangle (194 blue squares and 35 green squares), defined by the intersection of rows 1–23 and columns 34–43. This rectangle is defined by the distances among the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets and the dual-stream paper recyclables data sets. In fact, all of the disposed MSW-dual-stream paper recyclables distances are blue squares. The colors indicate that the composition of these data types is different from each other. Jefferson County, Town of Southold, and 2018 EPA disposed MSW data are farthest away from the dual-stream paper recyclables data, while the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) planning total waste stream data are a little bit closer (but still are far away). The dual-stream paper recyclables data are farther away (more dissimilar) from the total waste stream and disposed MSW data than the dual-stream container recyclables data, especially for the Ulster County data.

There is a blue with green highlights rectangle defined by the intersection of rows 24–33 and columns 44–49. This rectangle is defined by the distances among the dual-stream container recyclables and the single-stream recyclables data sets and indicates that the composition of these two data types is different from one another. Delaware County single-stream data were a little more similar in composition to the dual-stream container recyclables data sets, and OHSWA single-stream and 2018 EPA recyclables data were farther away from the dual-stream container recyclables data and therefore more different.

A more green-than-blue rectangle is defined by rows 1–23 and columns 24–33; this rectangle is determined by the distances among the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets and the dual-stream container recyclables. The colors indicate that the composition of these data is different from each other, although other comparisons have greater overall differences. The composition of Delaware County, Town of Islip, and Ulster County dual-stream containers is less similar to the total waste stream and disposed MSW data. The NYSDEC planning total waste stream data sets, Town of Brookhaven, and Town of Smithtown MSW data are somewhat more similar to the dual-stream container data, and Town of Southold, 2017 NYC, and 2021 California data are somewhat more different. The 2017 NYC dual-stream container data are about the same distance from the total waste stream and MSW data sets as the single-stream sample data, as are the Westchester container data and the mean 2021 NYS data for dual-stream containers, meaning they have the same overall degree of similarity. However, they are similar in different ways, because the comparison of single-stream recyclables to dual-stream container recyclables (the rectangle below the total waste stream-MSW comparison to single-stream recyclables) is largely blue and violet, indicating these data points are far away from each other and therefore dissimilar in the overall composition.

There is also a green-with-yellow and blue highlights rectangle determined by rows 1–23 and columns 44–49. This rectangle shows the distance relations among the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets with the single-stream recyclable data sets. It suggests that their overall waste composition is different, but not as different as some of the other major waste type comparisons. This is especially true for the 2018 EPA recyclables comparison data. The NYSDEC land use-based total waste stream data are also closer and therefore more similar to the single-stream data sets than other total waste stream and MSW data sets. Jefferson County, Town of Southold, and 2018 EPA disposed MSW data tend to be farther away and therefore more different from the single-stream data sets; overall, the disposed MSW data sets are farther away from the single-stream recyclables data sets than the total waste data sets are.

Lastly, there is a heterogeneously colored rectangle defined by rows 34–43 and columns 43–49. This is defined by the distances among the dual-stream paper recyclables and the single-stream recyclables data sets. 2018 EPA recyclables are not yellow (eight green squares, two blue squares) and Delaware County single-stream recyclables also have eight green squares (plus two blue squares). Blue squares are associated with Ulster County dual-stream paper comparisons to the Delaware County single-stream recyclables and 2018 EPA recyclables, and Ulster County dual-stream paper recyclables are green in relation to OHSWA and Otsego County single-stream recyclables, the mean 2021 NYS data for single-stream recyclables, and the comparison data set of 2019 OCRRA single-stream recyclables. Otsego County single-stream recyclables data share green squares with Delaware County, Jefferson County, the Town of Smithtown, and Ulster County dual-stream paper data. These results are thus dissimilar. All other comparisons are coded as yellow or orange, indicating a degree of waste composition similarity.

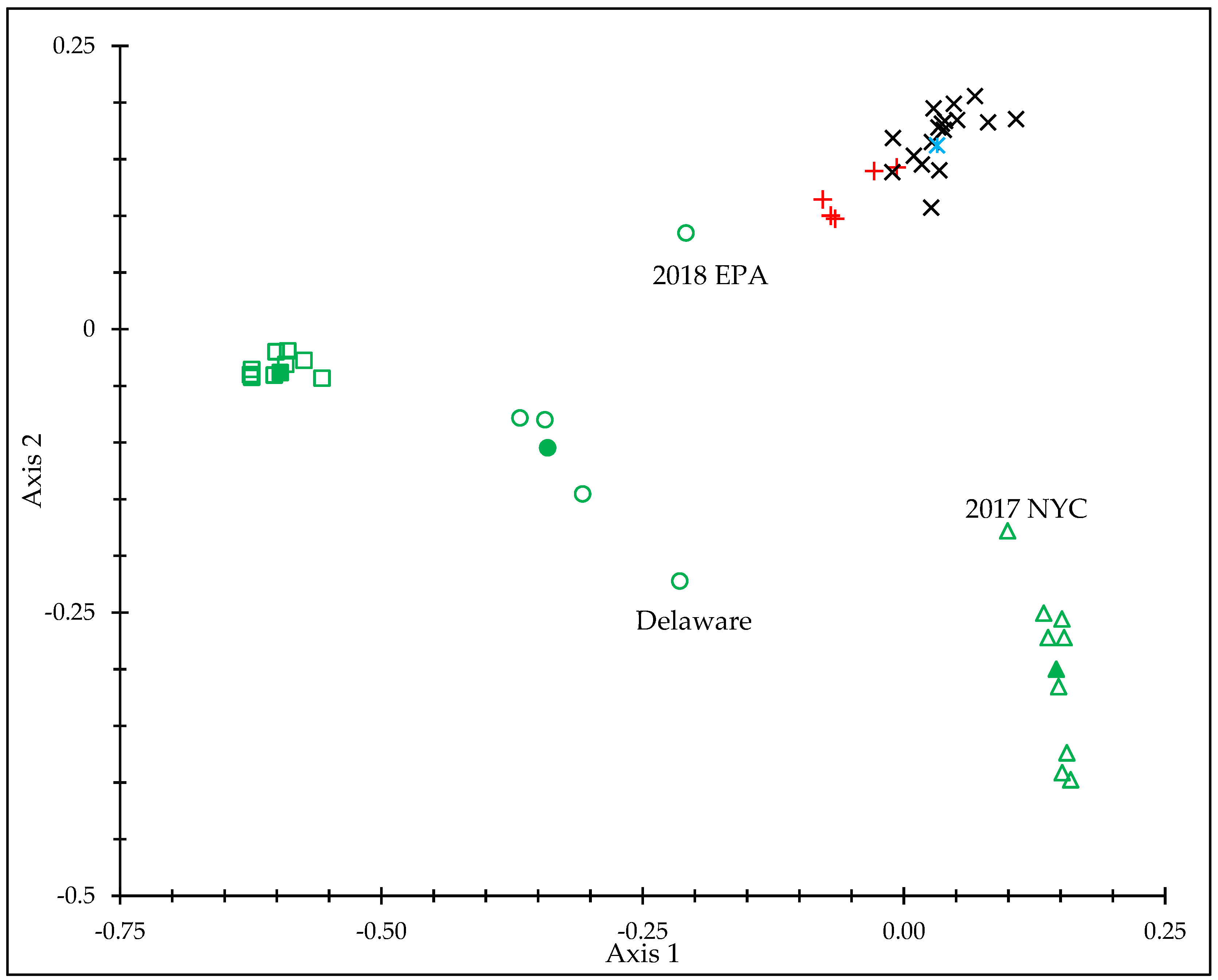

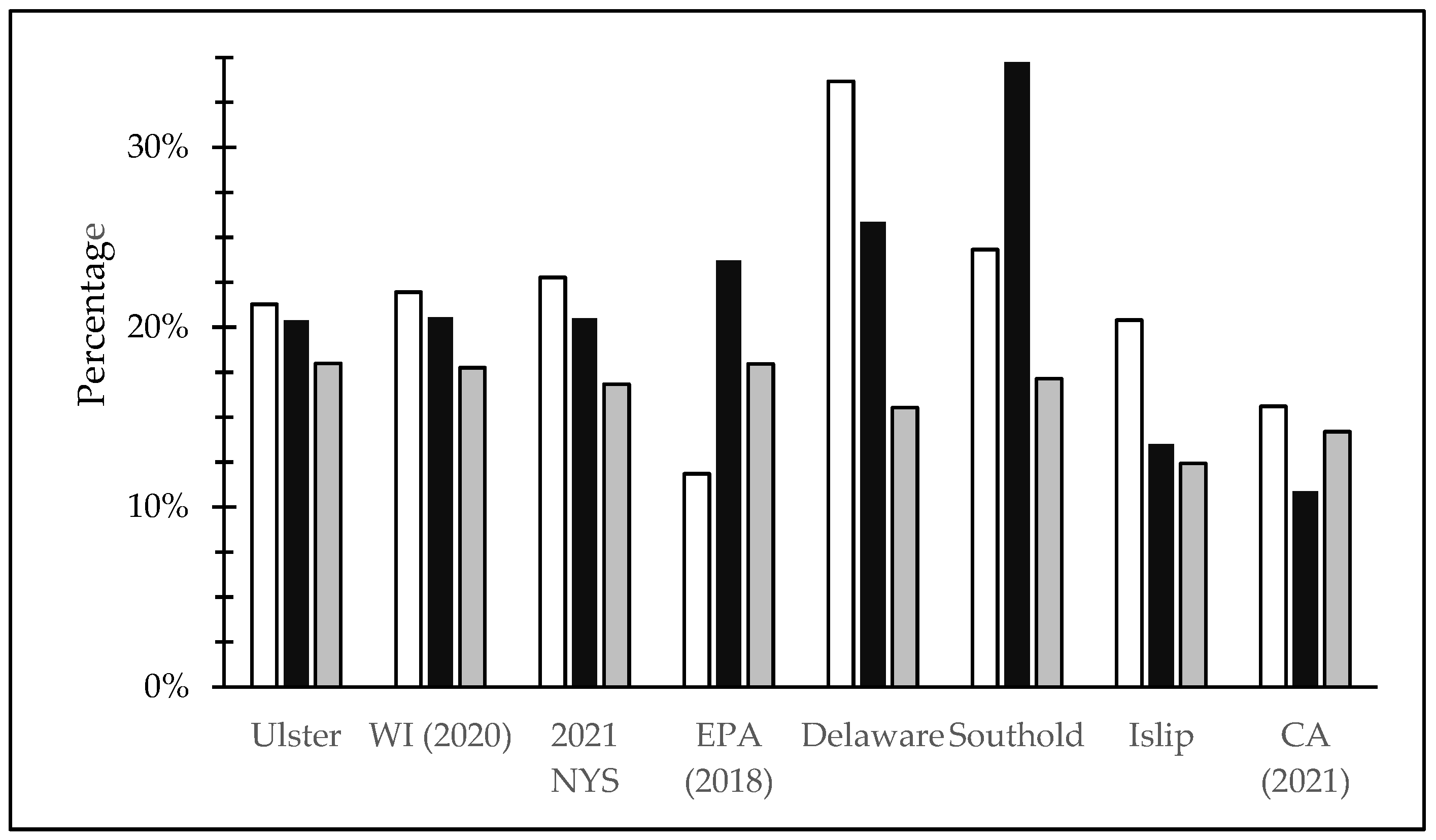

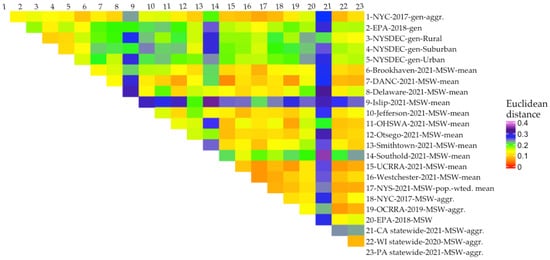

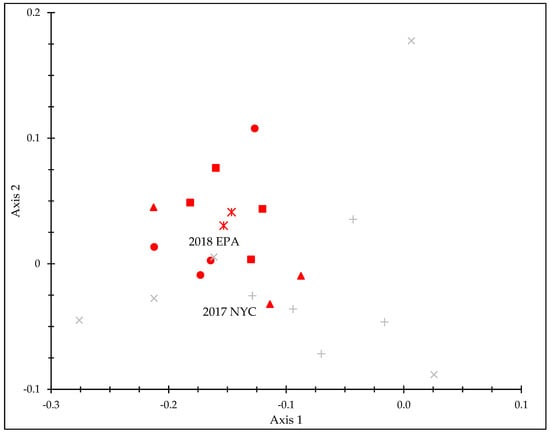

Principal component analysis (PCA) mostly confirms the Euclidean distance relationships and makes them easier to visualize. In Figure 2 the general relationships among the major clusters are easily determined. Total waste and disposed MSW data map close to each other. Dual-stream container recyclables and dual-stream paper recyclables map farther away from the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets, and farthest of all from each other. The dual-stream paper recyclables data set is compact and the dual-stream container recyclables data set is relatively dispersed. The single-stream recyclables data lie between the dual-stream container recyclables and dual-stream paper recyclables data sets. The single-stream data set is shown as being fairly dispersed due to two outlier data points, which were not reflected in the distance data. The first two axes of this PCA account for 83% of the variance, which means it reflects the distance data relations fairly well but not completely so.

Figure 2.

PCA of the 2021 data sets. (+ = total waste stream; x = disposed MSW; * = mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW; Δ = dual-stream container recyclables; ▲ = mean 2021 NYS dual-stream container recyclables; □ = dual-stream paper recyclables; ■ = mean 2021 NYS dual-stream paper recyclables; ○ = single-stream recyclables; ● = mean 2021 NYS single-stream recyclables).

Waste Composition Similarities and Differences among Total Waste Stream and Disposed MSW Data Sets

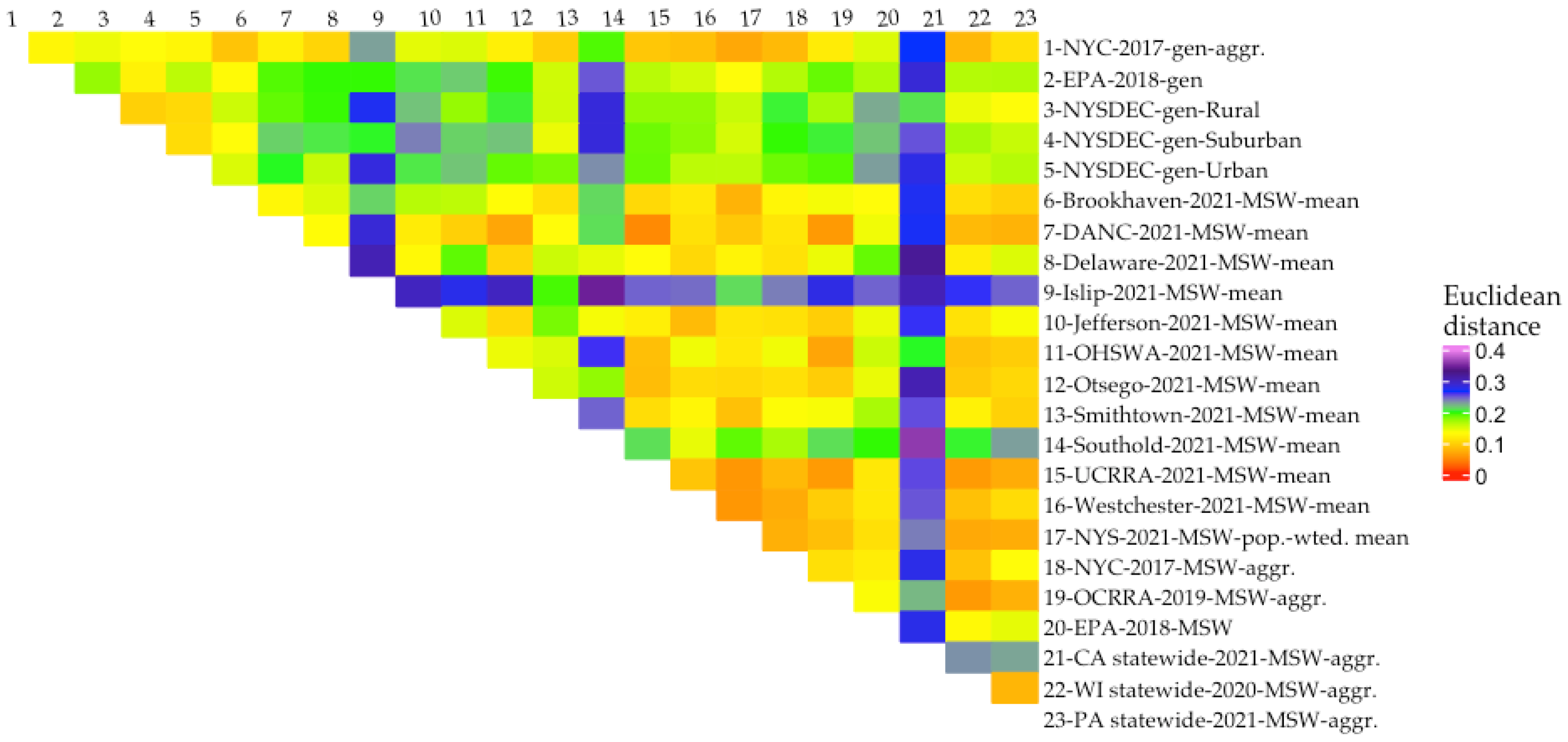

It is possible to change the scale of analysis to look within one of the major data clusters to further explain similarities and differences in waste composition using the multivariate distance data. The first 23 rows and columns of the triangular matrix can be used to examine the total waste stream data sets (rows-columns 1–5) and the disposed MSW data sets (rows-columns 6–23). Figure 3 is the heat map representation: notice the scale for the heat map colors has changed The three discrete data groupings seen also in Figure 1 are (1) the heterogenous orange-yellow-green triangle from the intersection of rows-columns 1–5, which is the distance relationships among the total waste data sets (10 squares in total); (2) the 153 square triangle formed by the intersection of rows-columns 6–23 which is the distance relationships among the disposed MSW data sets, and which is predominantly orange with interspersed lines of green and blue-violet; and (3) the predominantly green rectangle formed by the intersection of rows 1–5 and columns 6–23 (90 squares in total) which represents the distance relations among the total waste data sets and the disposed MSW data sets.

Figure 3.

Heat map of the Euclidean distances between the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets.

In Figure 3, the total waste stream triangle is composed of three orange squares, five yellow squares, and two green squares. The orange squares are associated with the three NYSDEC planning data sets, meaning they map closer together and have a more similar overall waste composition. The two green squares are associated with the 2018 EPA data in relation to the urban and rural NYSDEC planning data sets, meaning they map farther away and are less similar in composition.

104 of the 153 disposed MSW triangle squares are orange or yellow: these two colors dominate the triangle. 14 of the 17 Town of Islip squares are blue or violet, and 15 of the 17 2021 California squares are blue or violet, meaning that these two data sets create strongly colored lines across the triangle and account for 28 of the 31 blue or violet squares. These two data sets are clearly farther from the other disposed MSW data sets, meaning they are less similar in composition. The Town of Southold shares blue squares with Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority (OHSWA), the Town of Smithtown, and 2021 Pennsylvania, meaning it is farther from those data sets, but is also violet with the Town of Islip and 2021 California, meaning it maps away from those two data sets, and therefore is different in overall waste composition from these data sets. All of the data sets except for the Town of Islip, the Town of Southold, and 2021 California have 13–15 orange and yellow squares, showing they all map generally close to each other and have similar waste composition. The Town of Islip and 2021 California also share a blue square, meaning that they map differently from each other and most of the data sets and have distinctly different waste compositions.

The rectangular overlap between the waste generation data and the disposed MSW data shows that the 2017 NYC waste generation maps closest of the five waste generation data sets to the disposed MSW data and that the Town of Islip, Town of Southold, and 2021 California map away from the waste generation data sets, and are less similar in waste composition. The Town of Brookhaven, the Town of Smithtown, and the NYS population-weighted data sets map closest of the MSW data sets to the total waste data sets and so are more like the waste composition of the total waste stream data sets.

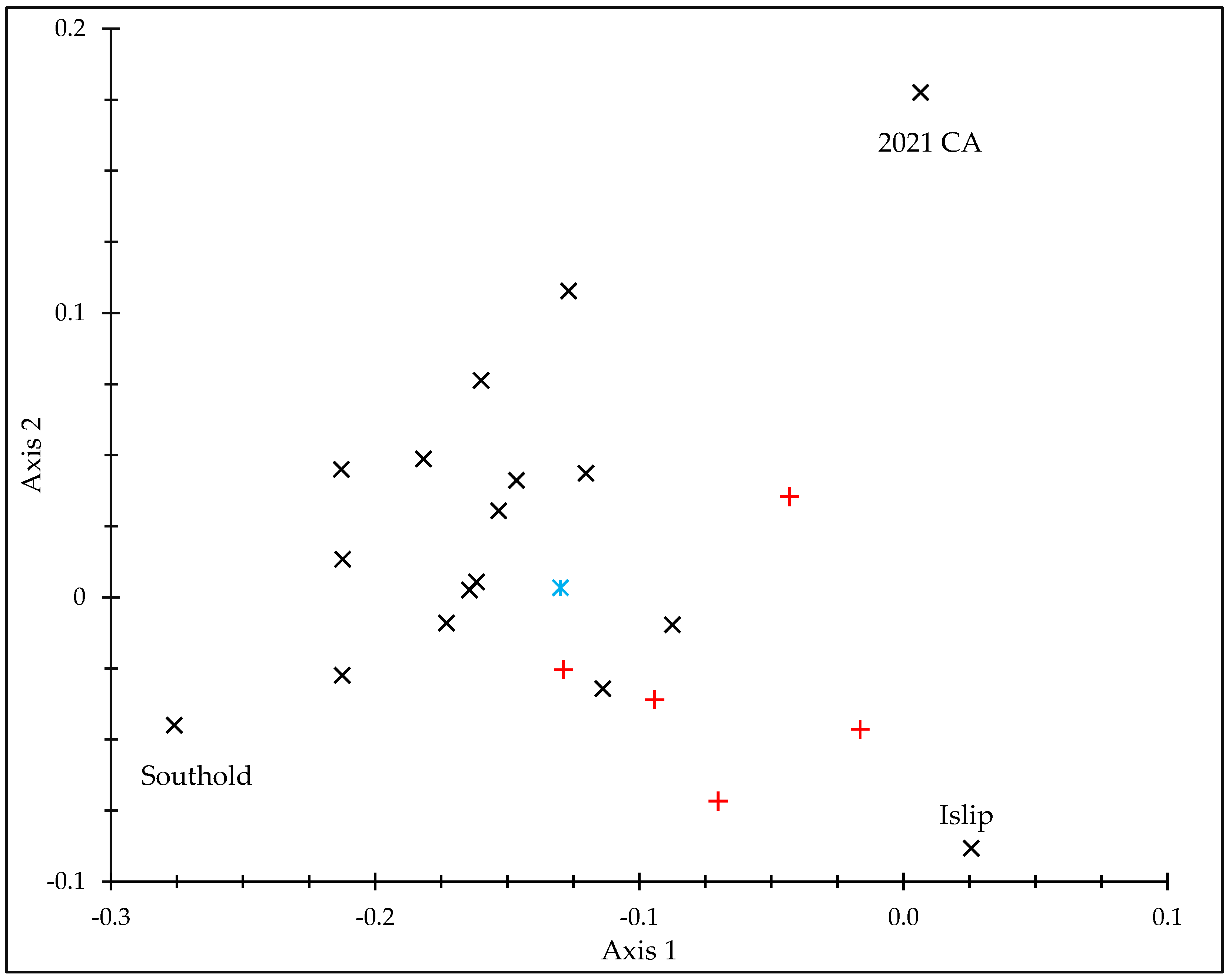

A second PCA of only the total waste stream and disposed MSW data (Figure 4) enables another visualization of the similarities and differences among the total waste stream and disposed data waste compositions, although the first two axes of the PCA only account for 59% of the overall variance. Generally, total waste stream data are distinct from the disposed MSW points, although not entirely so. The 2021 California, Town of Islip, and Town of Southold disposed MSW data are different in composition (farther away) from the total MSW data points according to the distance mapping, and this is seen in the PCA. Some of the disposed MSW data points are found to be close to total waste stream data (similar in composition), and there is an overlap in the PCA between the two sets of data.

Figure 4.

PCA of the 2021 total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets. (+ = total waste stream; x = disposed MSW; * = mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW data point).

The 2021 California, Town of Islip, and Town of Southold data are depicted as having dissimilar overall waste composition from other disposed MSW data (being farther away), and this too is seen in the PCA. Most of the disposed MSW data points are found to plot close to each other in multivariate space (to have similar overall waste composition) and in general in the PCA the disposed MSW points plot close to each other.

2.1.2. More Quantitative Analyses of the Multivariate Distance Measures

The mean distances within each waste type (total waste, disposed MSW, dual-stream container, paper recyclables, and single-stream recyclables) were calculated and compared to the distances from those points to the other waste types (Table 2). The within-group distances are all less than the distances to the other groups, suggesting the within-group data form a data cluster, and the mean distances from the within-group to the other data types are significantly different (Table 3). This shows that the within-group waste compositions are more similar than the waste composition comparisons outside of the groups.

Table 2.

Group mean Euclidean distance relations (MSW = disposed MSW; DS = dual-stream).

Table 3.

t-tests results for mean group distances (MSW = disposed MSW; DS = dual-stream).

The total waste category is closest to the disposed MSW group (the distance data implies some overlap between them), meaning that the total waste stream data are most similar to each other, but also are similar to the disposed MSW waste composition. The total waste stream data are farthest from the dual-stream paper recyclables data. The total waste data points are closer to the single-stream recyclables data points than the dual-stream container recyclables data.

Conceptually, the total waste stream is the disposed MSW plus recyclables. Given NYS source separation rates of typically less than 20%, recyclables are 20% or less of total wastes and disposed MSW are typically 80% or more of total wastes. Therefore, it makes good sense that the total waste stream and disposed MSW are found to be similar in the overall composition, as they share 80% or more of components. Targeted single-stream recyclables are a mixture of paper and containers and therefore more like the overall waste stream than the more segregated materials types of dual-stream paper recyclables and dual-stream container recyclables. Therefore, single-stream recyclables should map closer to the total waste stream than the dual-stream recyclables types.

The disposed MSW data has a slightly larger within-group average distance than the total waste data, meaning it is a more dispersed cluster. Similarly, the disposed MSW data points have a smaller distance to the single-stream recyclables data points than the dual-stream container recyclables and the dual-stream paper recyclables data, as with the total waste stream data, and for the same conceptual reason.

The dual-stream container recyclables are fairly dispersed with a mean within-group distance of 0.32, suggesting that there is some degree of variability in overall waste composition across this data set. They are nearly equal in distance from total waste data (0.52), MSW data (0.54), and single-stream recyclables data (0.56) but much farther away from dual-stream paper data (0.83). This underscores that dual-stream container recyclables share very few overall waste composition characteristics with dual-stream paper recyclables.

The dual-stream paper data has a larger average within-group distance, partially because the Ulster County data are different in overall composition from other elements of the group. In general, the dual-stream paper recyclables are not very close to any of the other data groups, meaning this group is most different in composition in comparison to the other data types. However, it is closer to the single-stream recyclables (0.37) than to the total waste stream (0.60) to MSW data (0.69), and farthest from the dual-stream container data (0.83).

The single-stream recyclables data have a moderate within-group average distance, partially because the EPA data are different from other elements of this data set. Single-stream recyclables waste composition is distinctly different from both total waste and dual-stream paper recyclables (0.37) and farther away from the MSW (0.47) and dual-stream container data (0.56).

All of these differences were statistically significant, which implies that within-group waste composition is much more similar than waste composition comparisons to the other waste types.

2.1.3. Quantitative Waste Composition Comparisons within the Disposed MSW Data Group

Within the disposed MSW data group, the Town of Islip and 2021 California data are farther away (on average) than other data points (0.27) (Table 4). The Town of Southold data also tend to be farther away (0.21). In fact, the closest that the 2021 California data are to any other data point (0.20) is greater than the mean distance for the other data except for the Town of Southold and Town of Islip data. The closest that Town of Islip data were to any other data set is also greater than the mean distances for the data sets other than Town of Southold and 2021 California. The 2021 California data point is farthest away from the Town of Southold data point. The Town of Islip data point is farthest away from the Town of Southold data point, as well. The overall waste composition for these three data sets is different from other disposed MSW data sets.

Table 4.

Within-disposed MSW data cluster distance data.

Not surprisingly, the mean 2021 NYS data point is closest on average to all the other data points. The Development Authority of the North Country (DANC) and Ulster County data are closest to each other (most similar). Ulster County data are relatively similar (<0.10) to a total of nine locations, as is the mean 2021 NYS data point and the 2020 Wisconsin data point. The difference in mean distances for each of 2021 California, Town of Islip, and Town of Southold compared to the mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW data point distances are significant (p << 0.001). There is no significant difference in the mean distances for the 2020 Wisconsin (WI) (p = 0.36) and 2021 Pennsylvania (PA) (p = 0.21) and the mean 2021 NYS MSW data point distances. This shows that the 2021 California, Town of Islip, and Town of Southold disposed MSW waste composition are different from other disposed MSW data sets. It shows that the mean 2021 NYS overall waste composition is similar to the 2020 Wisconsin and 2021 Pennsylvania waste composition results.

2.1.4. PCA as an Analysis Tool

The PCA for the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets (Figure 4) only represented 59% of the total variance in its first two axes. Some aspects of its depiction of the data set capture important distance relationships. The closest point to the 2021 California data set is OHSWA, and the closest point to the Town of Islip is the Town of Smithtown, as in the quantitative distance measures. However, the closest point to the Town of Southold is not Jefferson County, as in the quantitative measures. The close association of the three NYSDEC total waste steam planning data points to each other is not captured, and a number of the quantitative relations discussed above are also not found in the PCA. The two closest data points are not DANC and Ulster County, but rather Westchester County and 2018 EPA, which are relatively not very close (0.12) in the quantitative distance measures. The closest point to Ulster County in the PCA is the 2020 Wisconsin data point, which maps close to Ulster County (0.06) in the quantitative distance measures, but not as close as DANC. In the PCA DANC is relatively isolated from other points, although, in the quantitative distance measures, it is a more central point (seven other data points within 0.10). Most importantly, the mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW data point is not centrally located and is closer to more other MSW data points than any other data point, as is described in the quantitative measures. Since these distance relationships reflect overall similarities and differences in waste composition, the PCA therefore does not capture some of the details of waste composition relationships, although as a visualization tool, it creates easy-to-interpret figures.

These caveats aside, some aspects of PCA support further data analysis. Using the Eigenvalues for each axis as a weight, the relative effect of each of the 16 variables on the overall differences among the data sets can be explored. Each variable factor was multiplied by the axis Eigenvalue for the two axes and then the absolute values were added, and the percentage of the variance accounted for by each factor for the graphs was then determined (Table 5).

Table 5.

Weighted factors for the PCAs (wted factors = weighted factors).

For the PCA for all data (Figure 2), OCC, other recycled paper, #1 (PETE)/#2 (HDPE) plastics, food, and recycled glass are the data that are most important to determine similarities and differences among the data. Recyclables in general account for 56% of the overall differences and similarities. All paper accounts for 38%, and all plastics are 20%.

For the total waste-disposed MSW PCA (Figure 4), food, yard wastes, and other inorganics are the dominant factors, along with other organics. While each paper category is only 6%, the sum of the three paper categories is 18%. Other inorganics comprise the sort categories of other inorganics, electronics, rechargeable batteries, household hazardous waste (HHW), and NYSDEC other materials. For most samples, this was mostly other inorganics, which are primarily construction and demolition debris (C&D) materials and ceramics, plus rocks and dirt. The other organics category includes the sort categories of rubber-leather, wood, other organics, and EPA other materials. The sort category of other organics is largely diapers, pet wastes, and other sanitary-related materials.

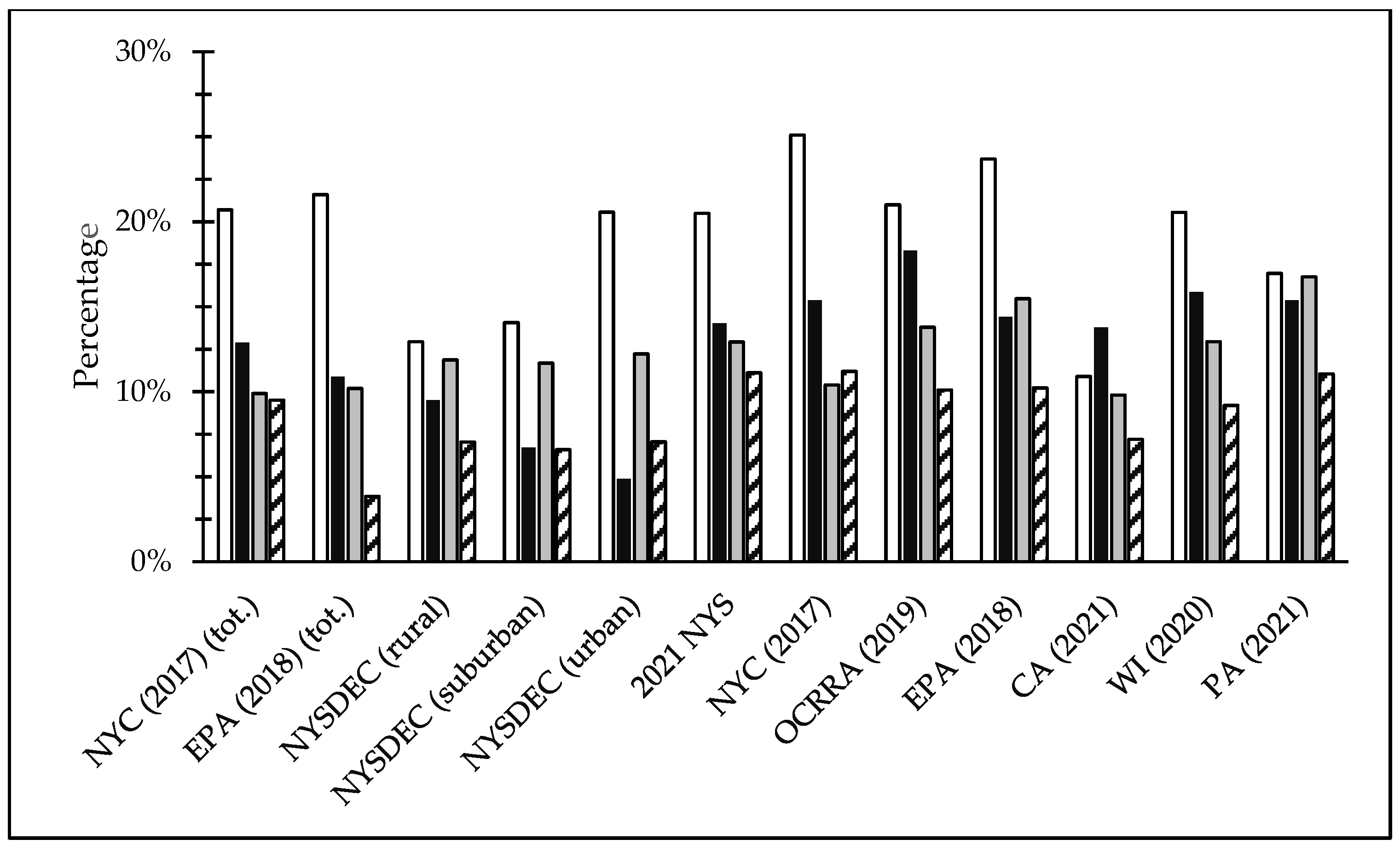

2.2. Standard Univariate Analyses

The major components found for NYS waste streams are presented here graphically and compared to total waste stream data sets (2017 NYS, 2018 EPA, and NYSDEC planning sectors) and to certain disposed MSW waste composition reports from other jurisdictions, either within NYS or contemporaneous with this sampling work (2017 NYC, 2018 EPA, 2019 OCRRA, 2020 Wisconsin, 2021 California, and 2021 Pennsylvania data sets). Waste composition sort studies rarely include recyclables collections, so the NYS recyclables data are presented in conjunction with the 2021 sorting data and are compared to 2017 NYC data for dual-stream recyclables and to 2019 OCRRA data and data for 2018 total EPA recyclables.

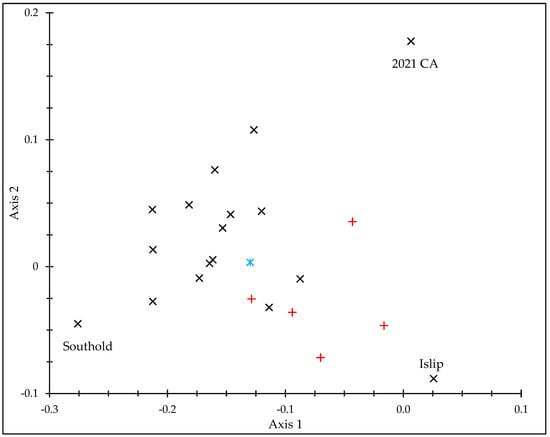

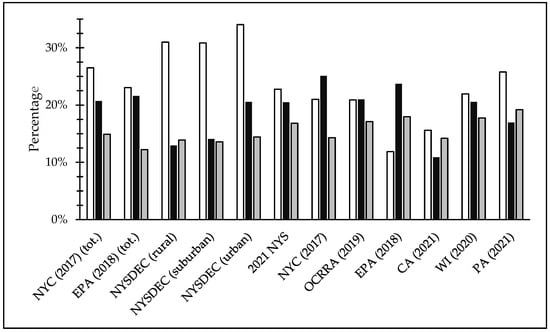

2.2.1. Overall Disposed MSW Composition

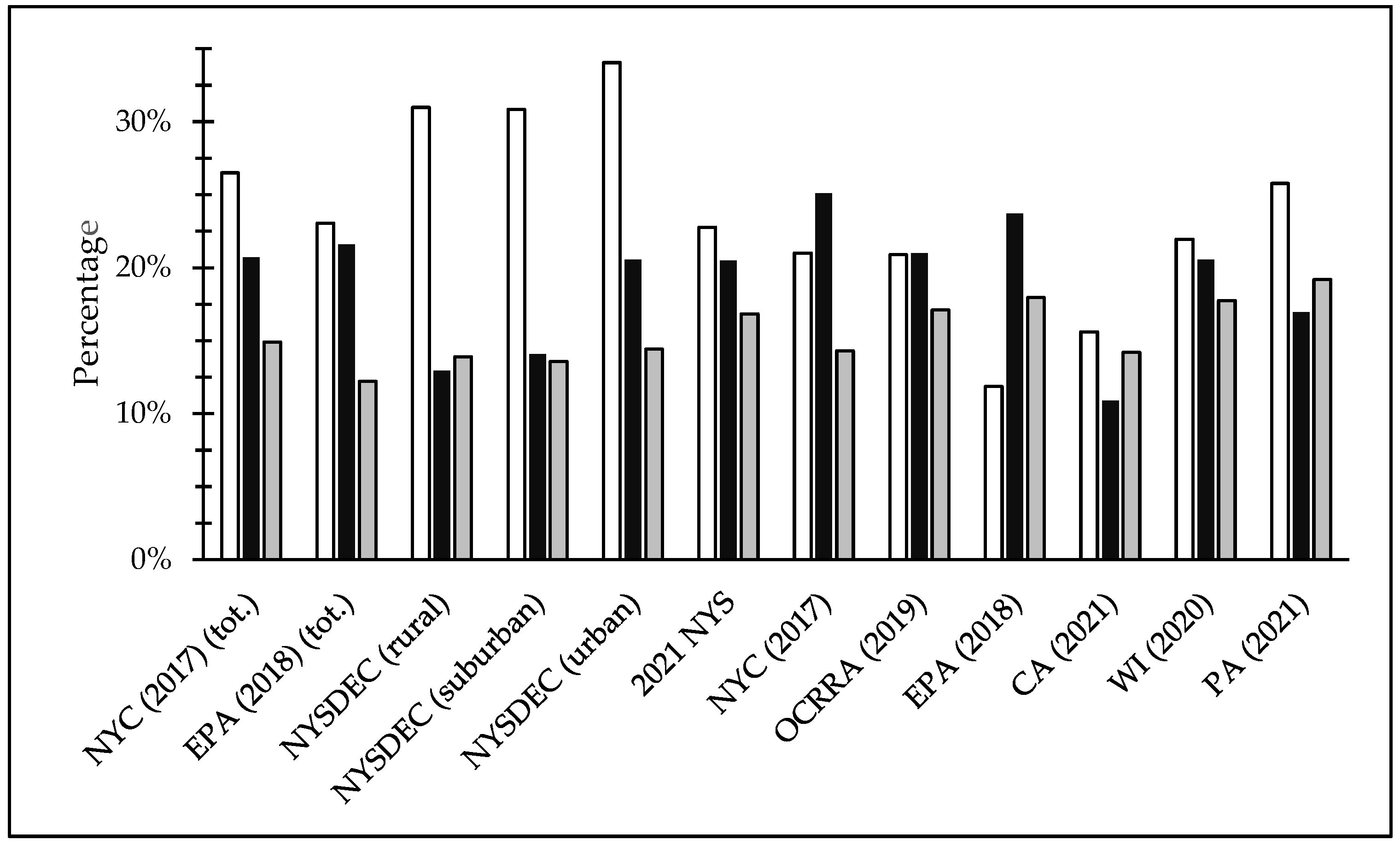

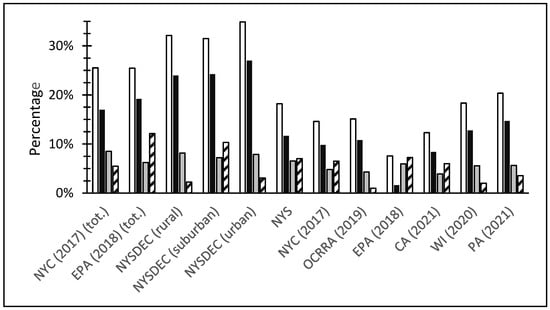

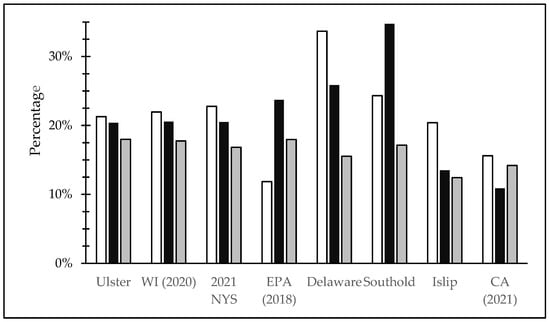

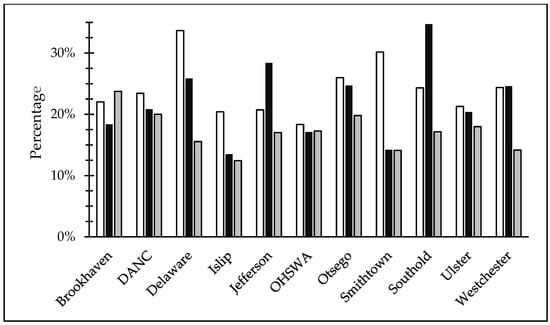

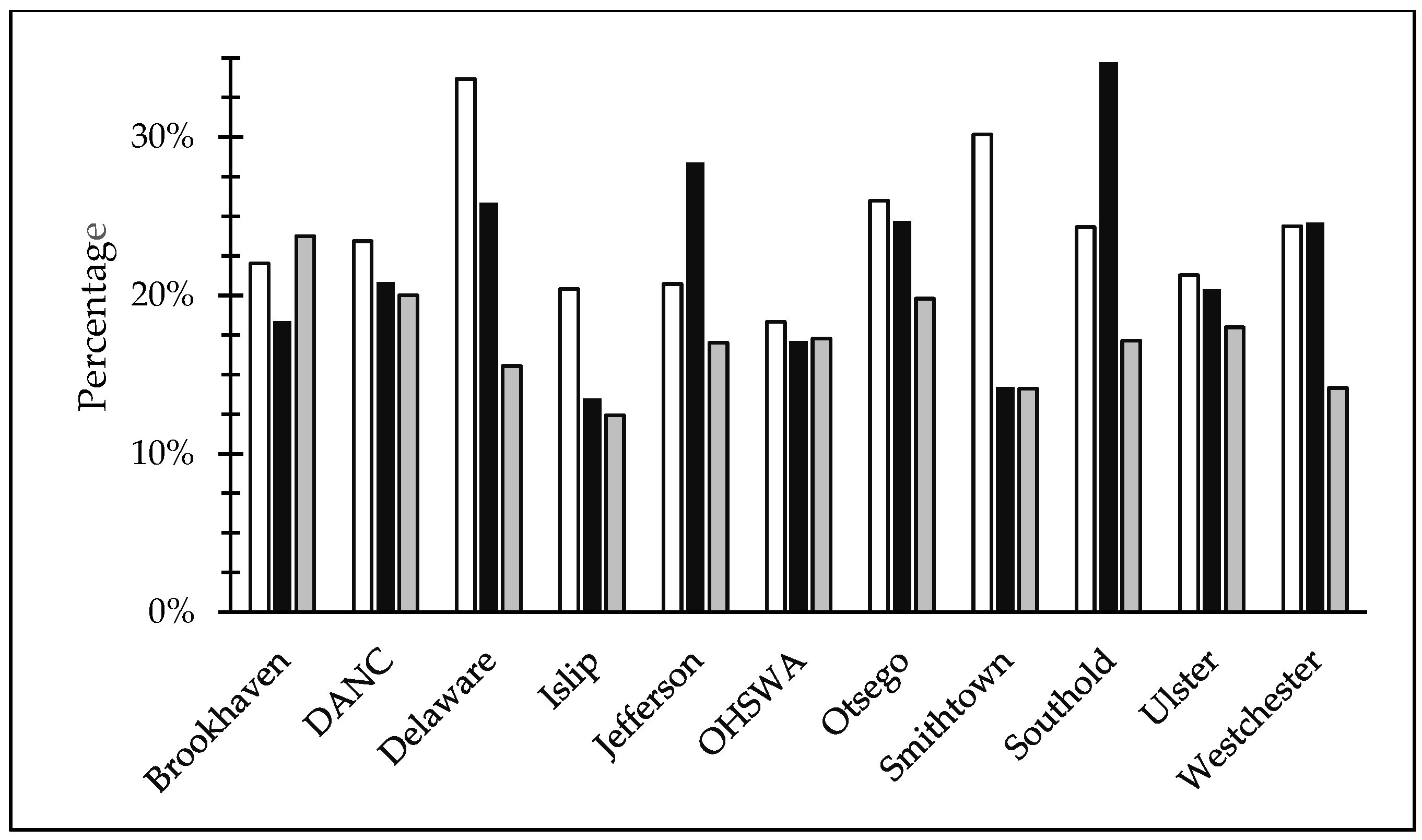

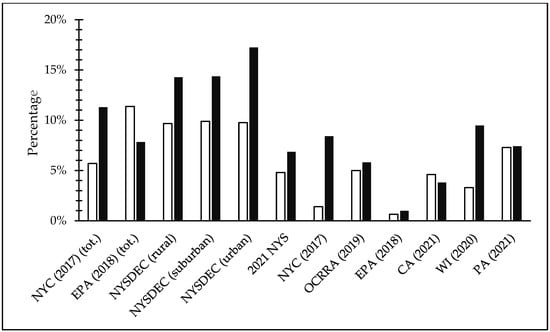

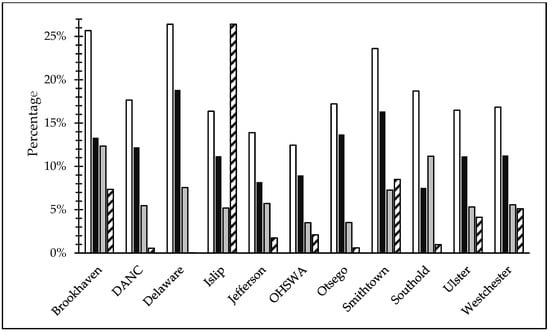

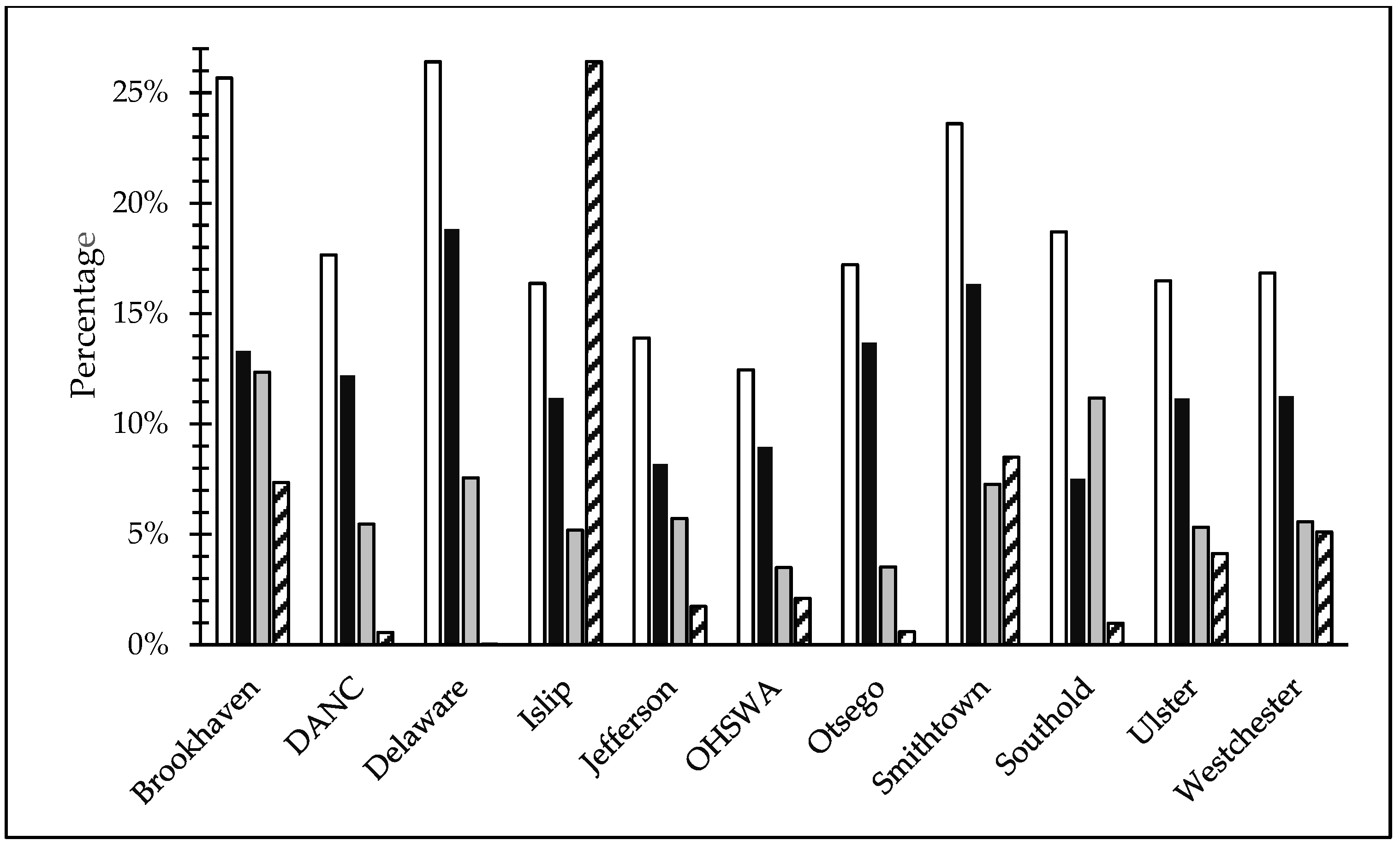

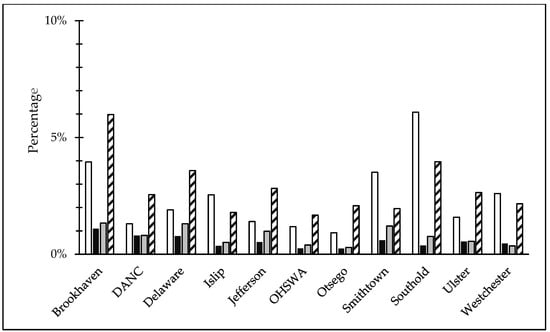

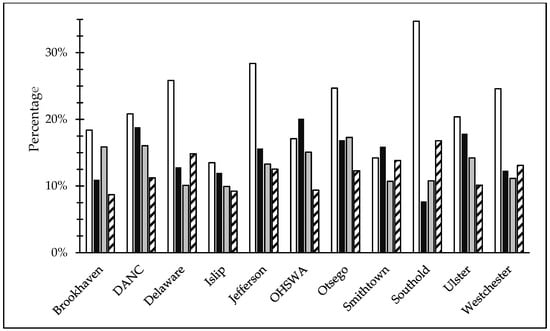

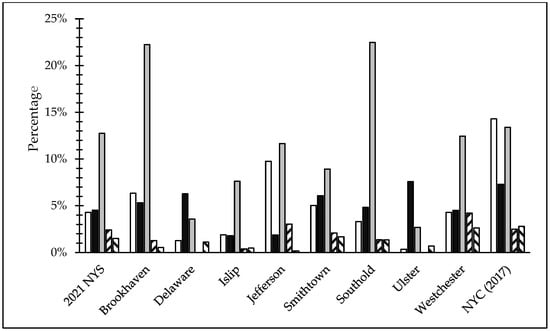

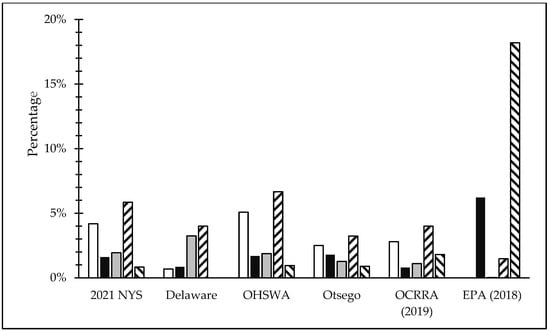

Paper was the single largest constituent in the mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW (22.8%), slightly more than food (20.5%) (Figure 5). Plastics were 16.8% of the disposed MSW stream. The percentages and patterns similar to this distribution were found for 2020 Wisconsin, the total 2017 NYC and 2018 EPA waste streams, and somewhat similarly for 2019 OCRRA. The NYSDEC planning estimates had much more paper; 2021 California data had lower percentages for paper and food; EPA (2018) disposed MSW had much less paper, and 2021 Pennsylvania data had more plastics than food. Individual system results (11 sampling sites) largely reflected this state-wide description (Figure A1). For the four systems, paper was the largest constituent. Food waste was the largest constituent in two systems (Jefferson County, Town of Southold). Plastics represented the largest constituent in the Town of Brookhaven. Paper and food were essentially indistinguishable in four systems.

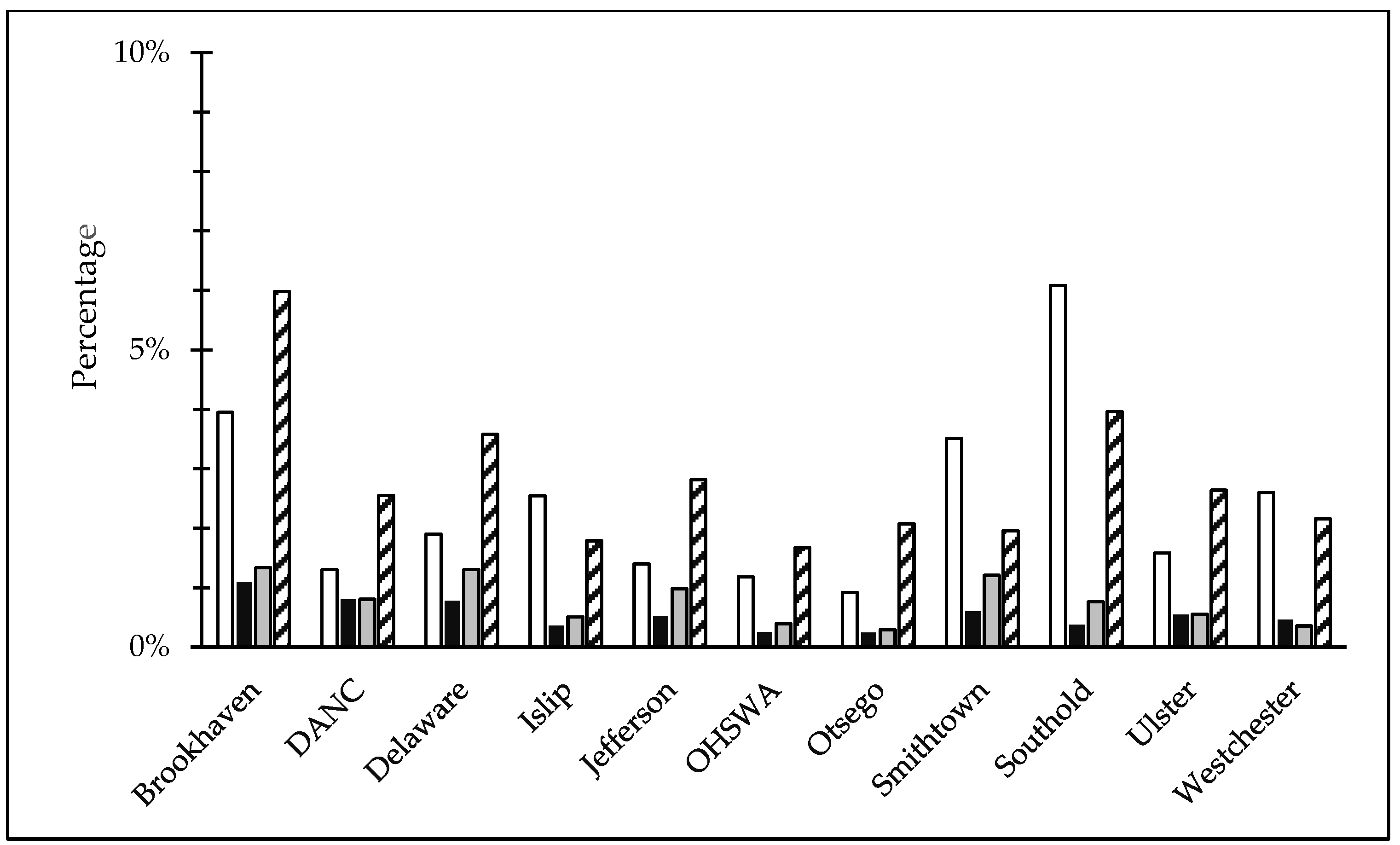

Figure 5.

Major constituents of 2021 NYS disposed MSW. (clear = paper; solid = food; gray = plastics).

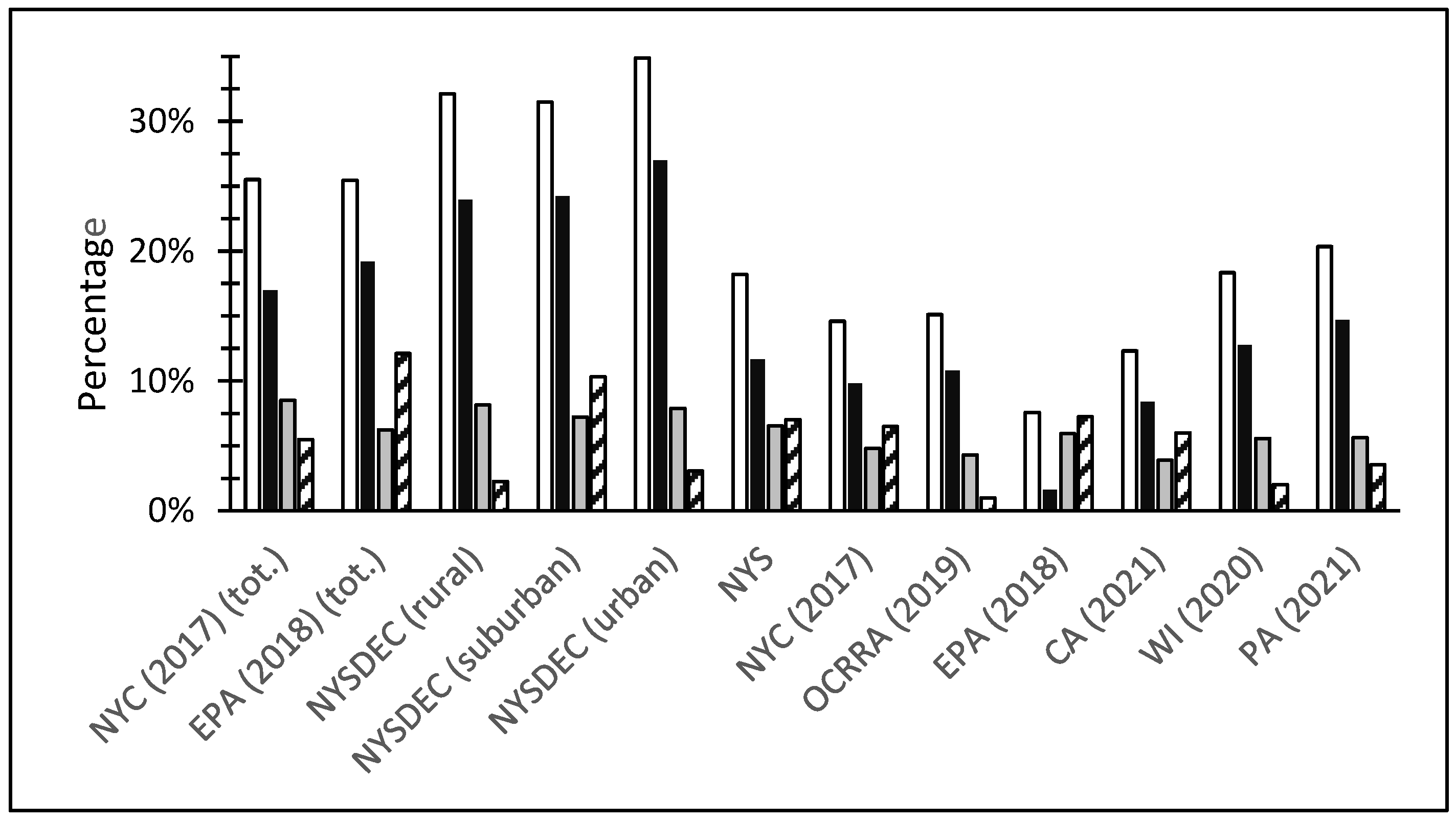

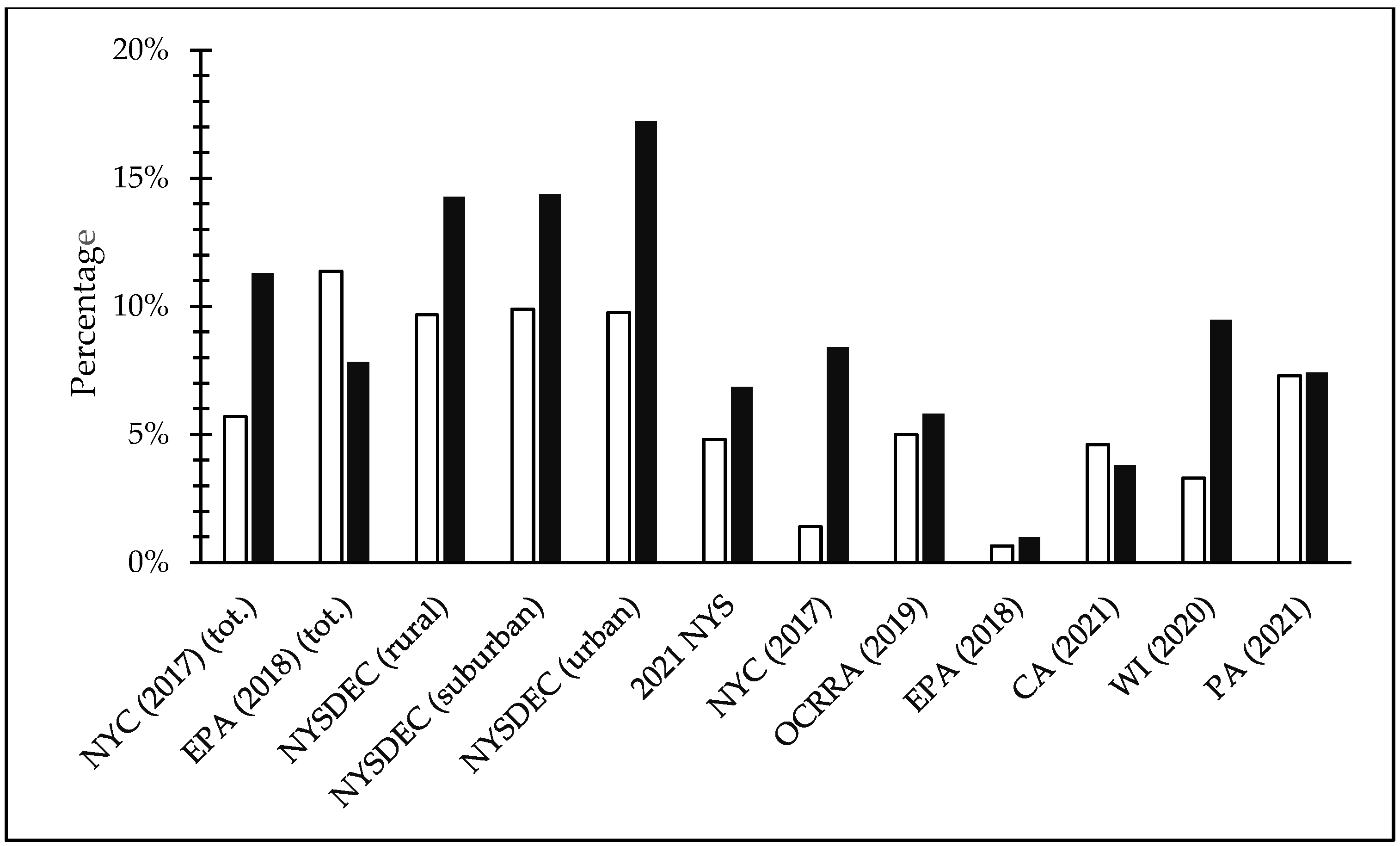

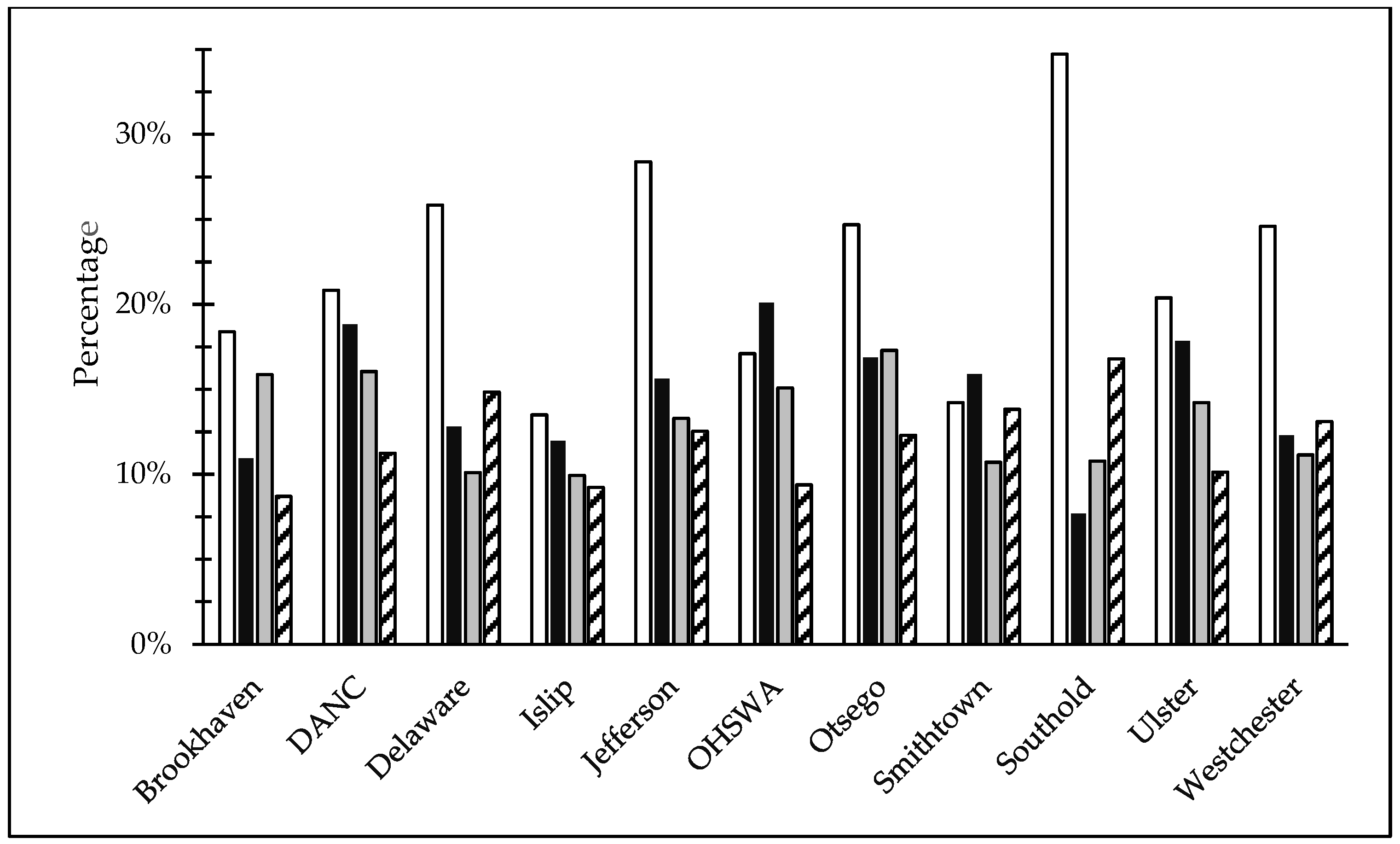

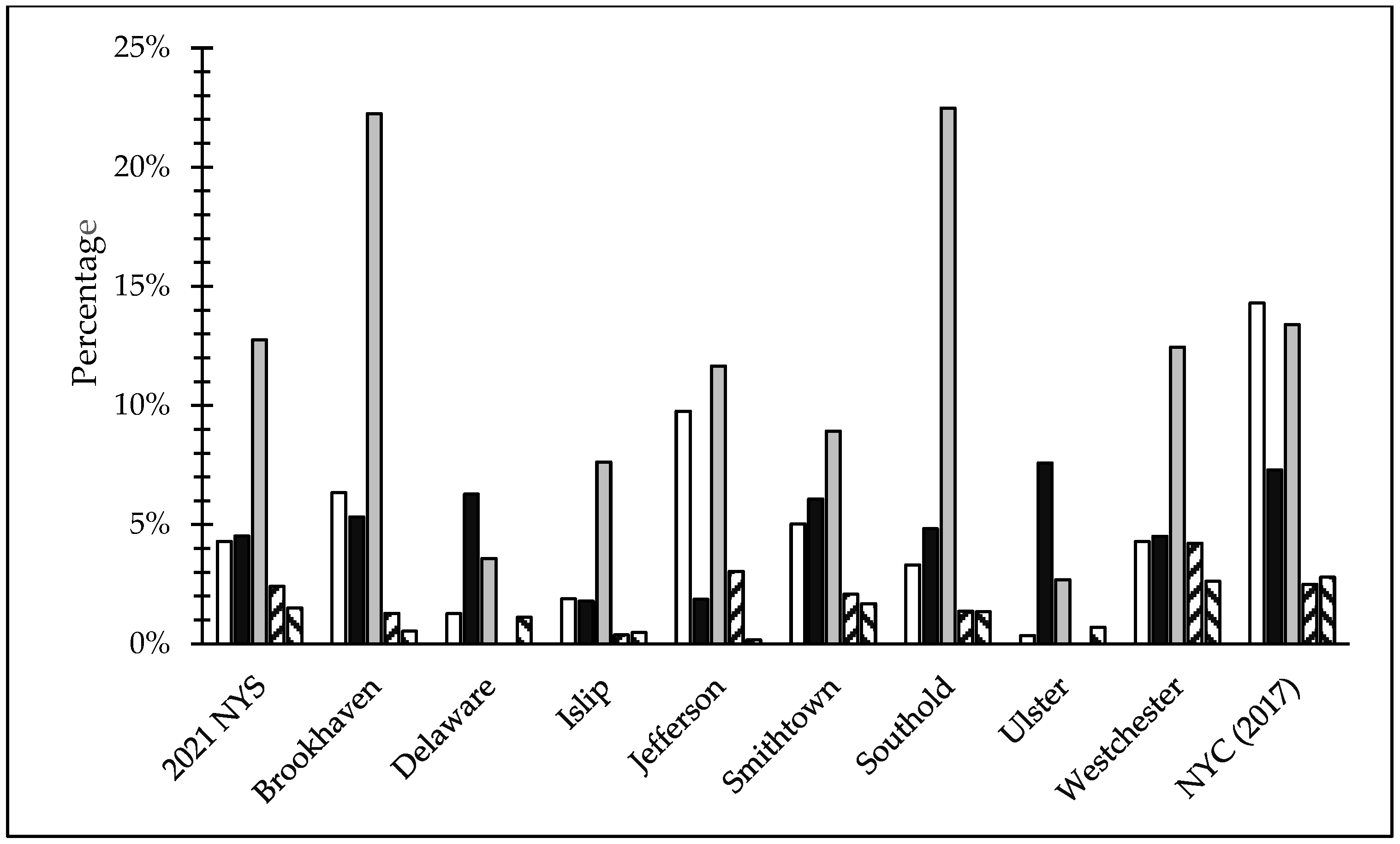

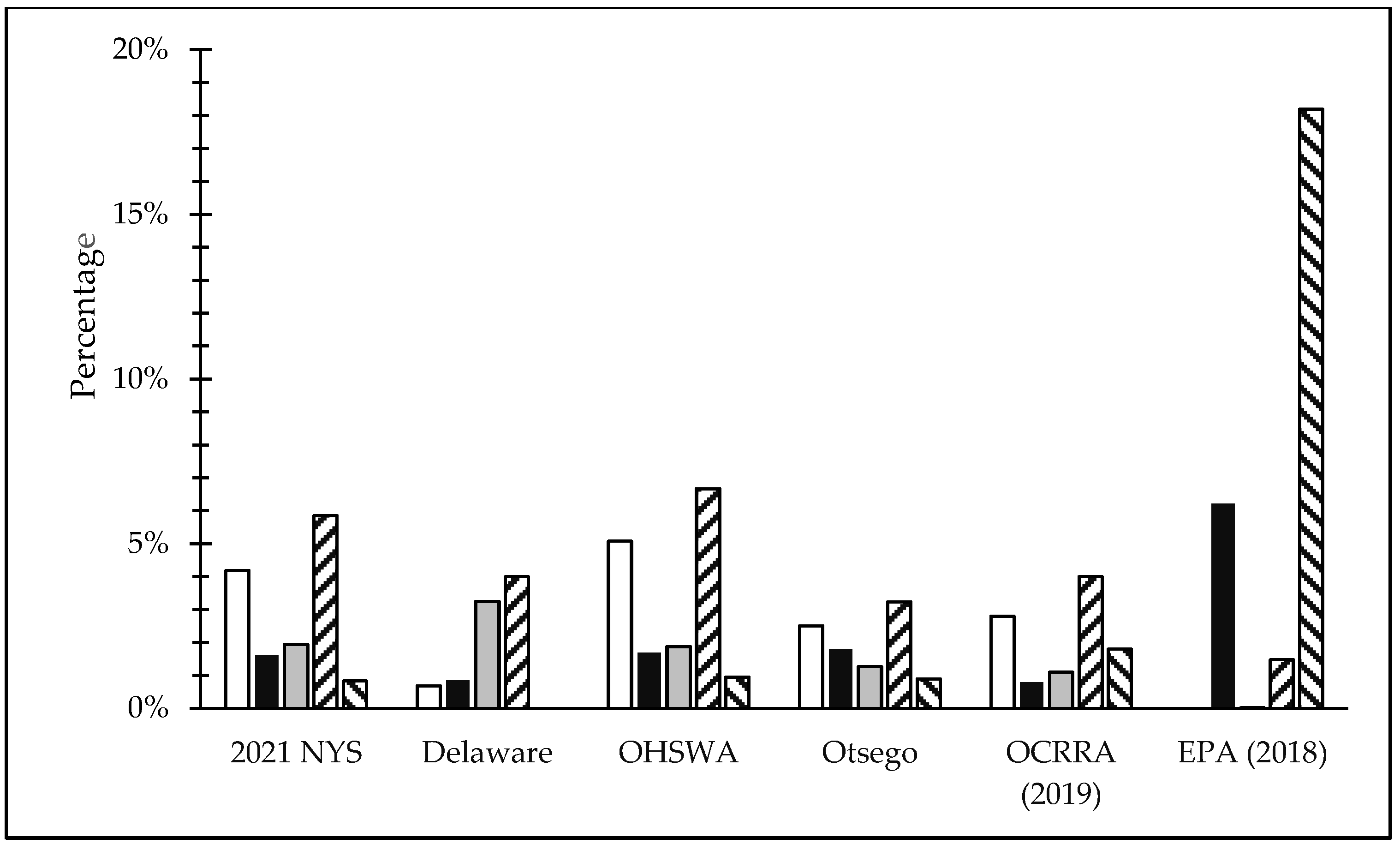

Determining targets for greater recycling efforts was an important goal of the sampling program. “Curbside” recyclables, here defined as recyclable paper (OCC and mixed recyclable paper) and standard container recyclables (glass containers, ferrous containers, aluminum containers plus foil, and #1 PETE and #2 HDPE plastic containers) were 18.2% of 2021 NYS disposed MSW (Figure 6). Yard waste is banned from disposal in NYS because it can be composted; it was an additional 7.0% of disposed MSW. About two-thirds of the curbside recyclables were paper, split between 5% OCC and more mixed recyclable paper (Figure A2). Container recyclables were composed of nearly equal proportions of glass and plastics in 2021 NYS disposed MSW but recyclable metals summed to only 1.3% of all disposed MSW (Figure A3). The overall distribution of recyclables in 2021 NYS disposed MSW was most similar to that found in 2017 NYC disposed MSW data. The 2021 Pennsylvania data were similar except that the percentage of disposed yard waste was less than the percentage of container recyclables.

Figure 6.

Recyclables in disposed MSW. (clear = curbside recyclables; solid = paper recyclables; gray = container recyclables; left-striped = yard waste).

The sampling locations show variability in the percentage of recyclables in disposed MSW, ranging from 12.5% at OHSWA to 26.4% in Delaware County. Recycled paper ranged from 7.5% in the Town of Southold to 18.8% in Delaware County. The Town of Brookhaven (12.4%) and the Town of Southold (11.2%) both had more than 10% container recyclables in disposed MSW. The Town of Islip had 26.4% yard waste, but Delaware County essentially had none (Figure A4). All of the sampling jurisdictions except DANC had more mixed recyclable paper than OCC (at DANC they were about the same) (Figure A5). Seven of the eleven sampling locations had more recyclable plastics than recyclable glass (Figure A6). The four that did not were the Town of Southold, the Town of Islip, the Town of Smithtown, and Westchester County. The town of Smithtown and the Town of Brookhaven (3.9% glass in MSW) did not collect glass in their recycling programs.

Four of the 16 variables consistently measured above 10% for 2021 NYS disposed MSW: food (20.5%), other organics (which includes the sampling categories of rubber-leather, wood, and other organics) (14.0%), other plastics (black plastics, rigid plastics, other plastic film, and other plastics) (12.9%), and other paper (non-recyclable paper and gable-top containers) (11.1%) (Figure A7). 2020 Wisconsin and 2019 OCRRA matched this overall pattern. The sampled systems were not consistent across these four categories, although the results from DANC, Town of Islip, and Ulster County were consistent with the overall 2021 NYS pattern (Figure A8).

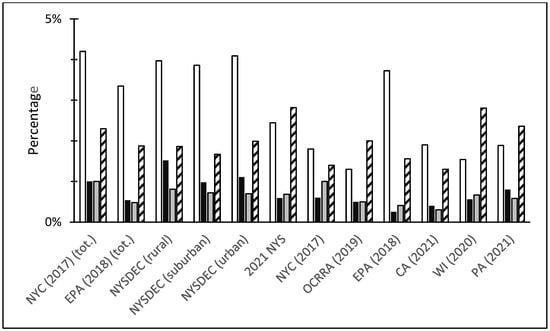

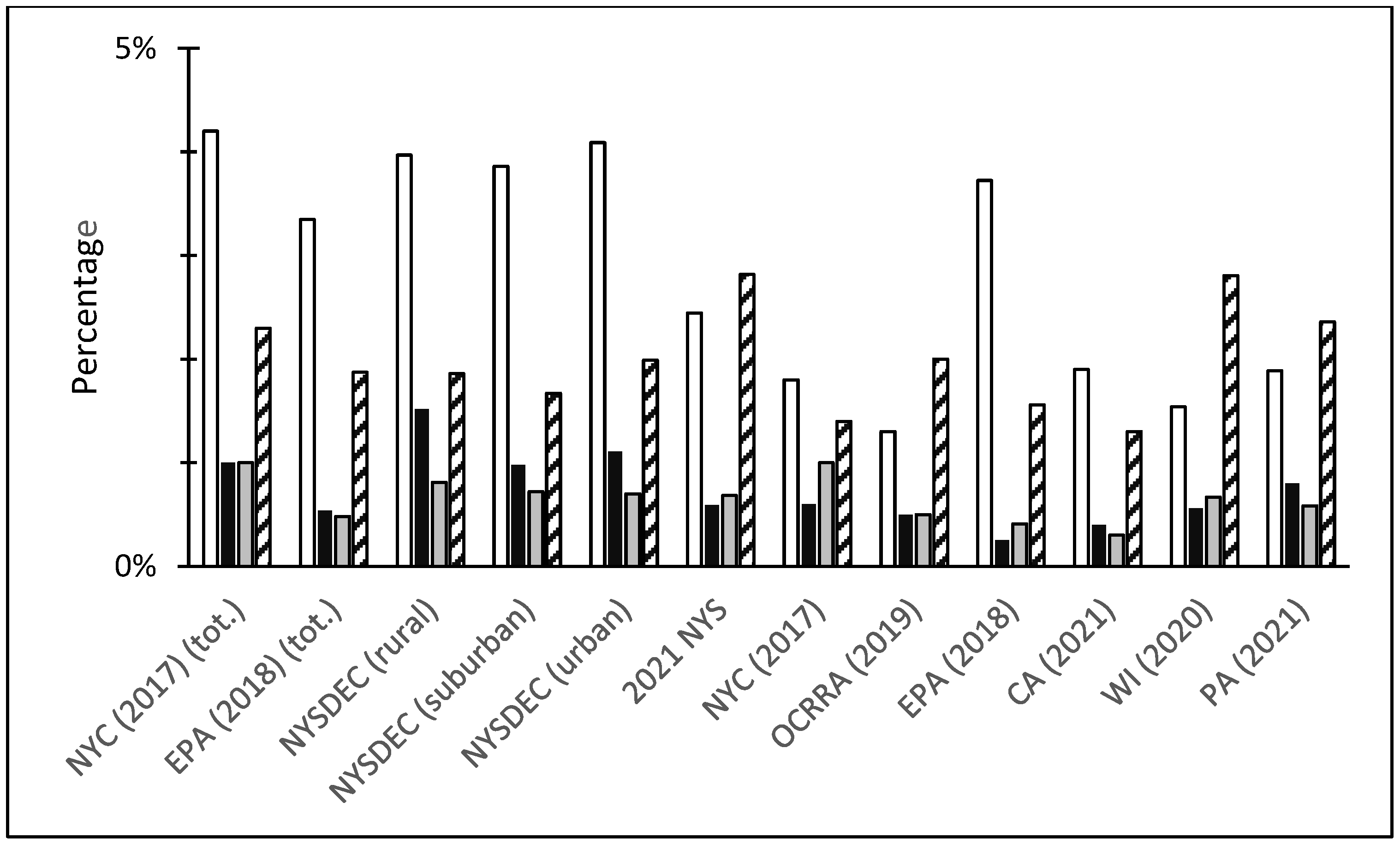

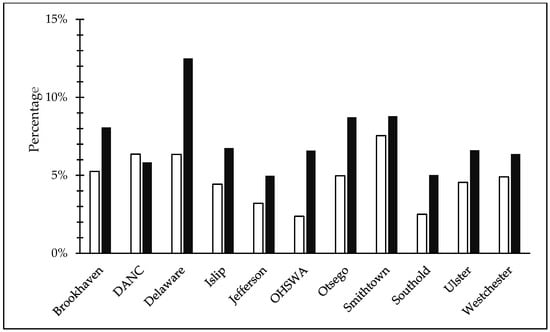

2.2.2. Standard Univariate Analyses of Recyclables Sampling

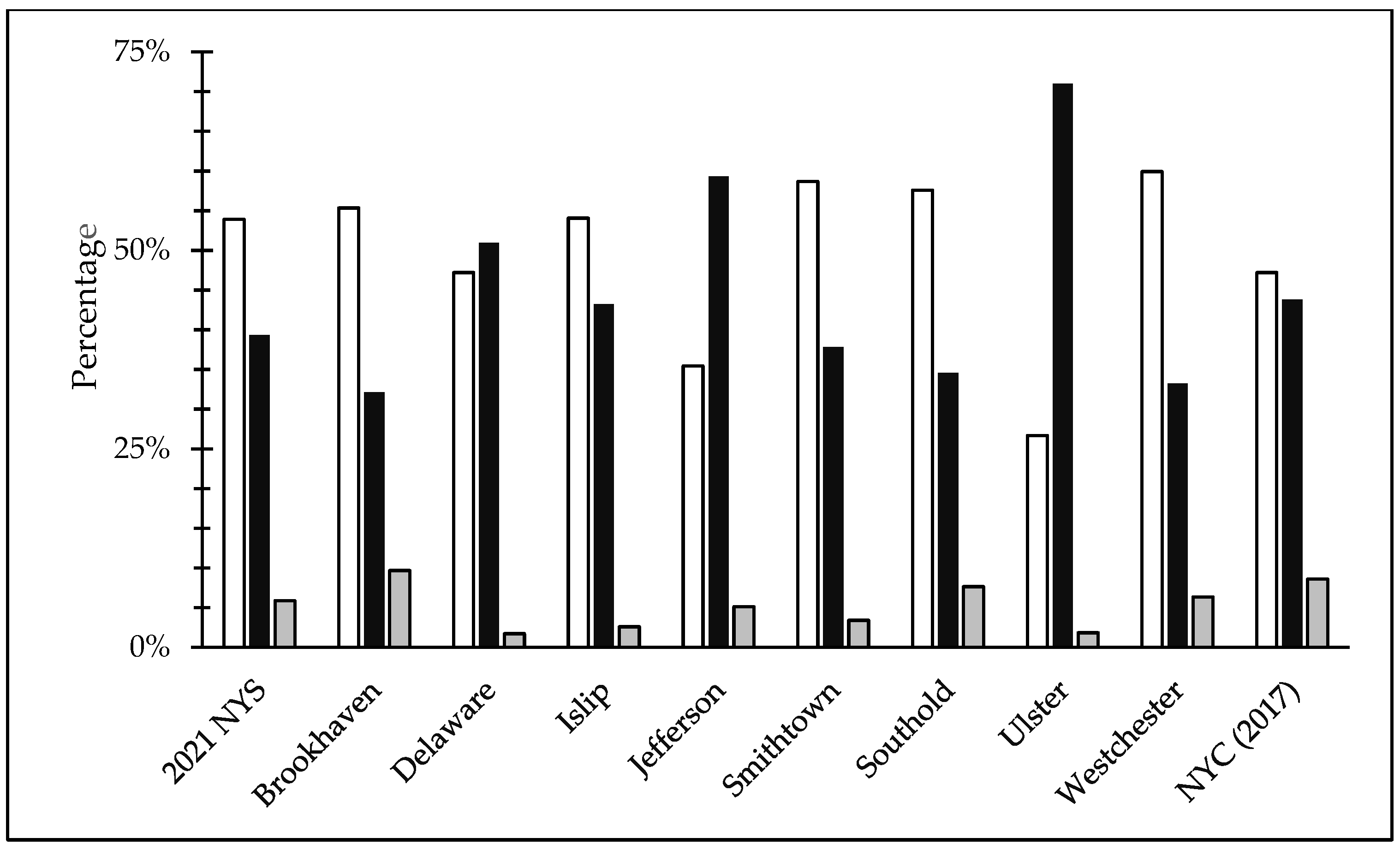

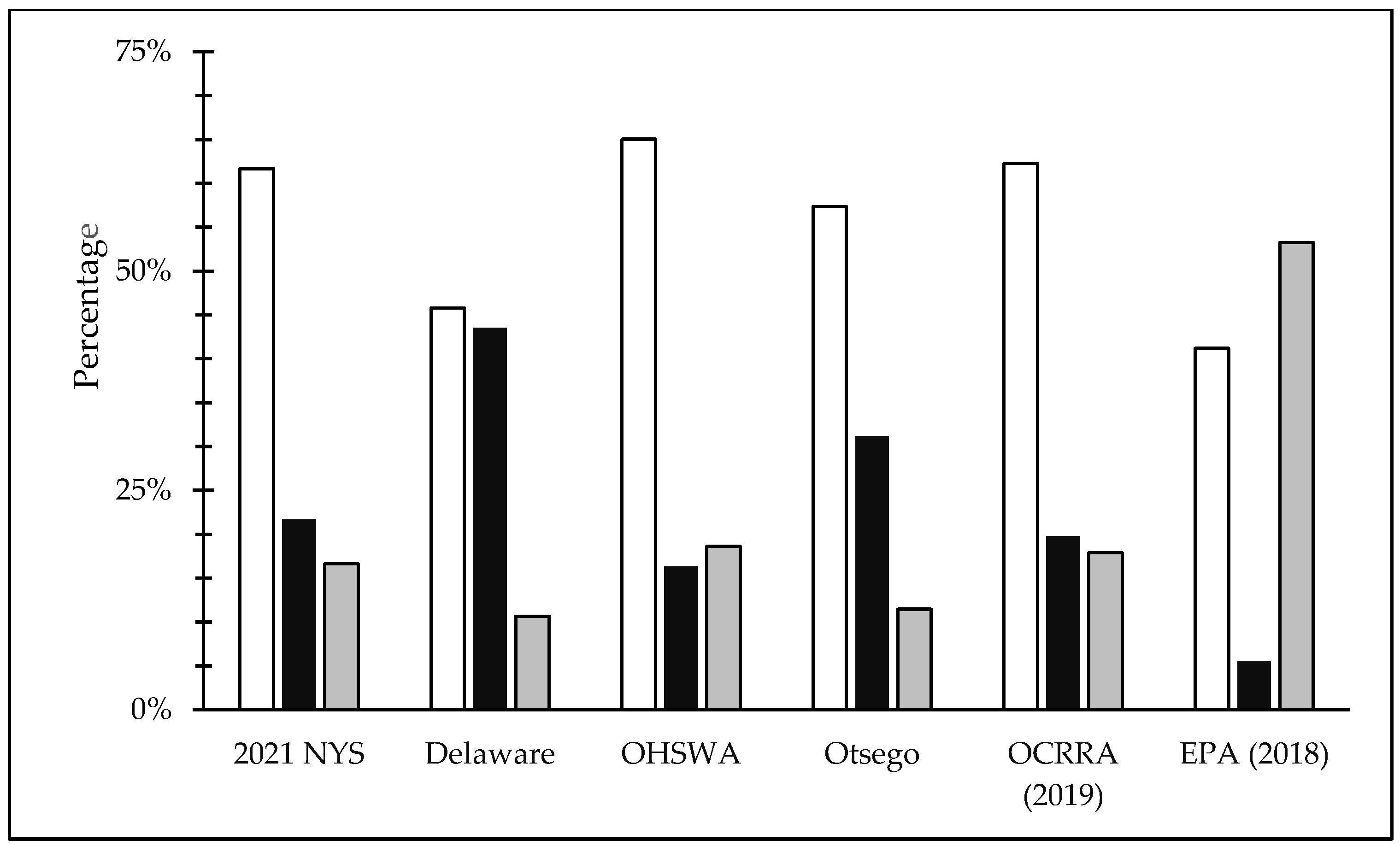

In New York State, recyclables are collected in three ways: separated or partially separated materials (nearly always at drop-of locations), such as OCC, glass, mixed recyclable paper, metals, or plastics; dual-stream recycling, where paper materials and containers are collected separately; or single-stream recycling, where paper and container recyclables are collected together. We collected seven separately recyclable samples (one glass, two metals, three OCC, and a boxboard sample), with not enough repetitions to report on 2021 State mean values. These data will not be reported beyond the data in Table S6. We collected samples from eight systems for dual-stream recyclables (25 paper samples, 24 container samples). We collected 12 single-stream samples from three systems, although 11 of the samples were from OHSWA and Otsego County and only one from Delaware County, and judged that sufficient to make some tentative generalizations.

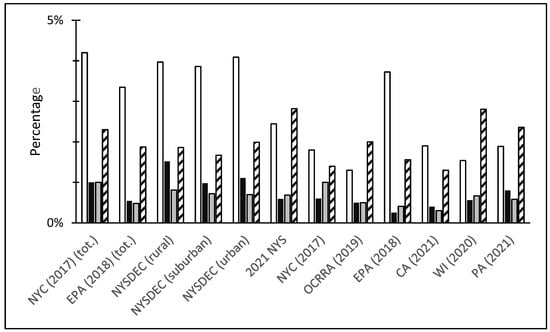

Dual-stream paper recyclables were sorted well (the mean 2021 NYS value was 93.3% recyclable paper, meaning only 6.7% were non-target materials) (Figure A9). The reduced data set reported corrugated cardboard (OCC) and mixed recyclable paper as the two categories of recyclable paper, as those are the two major marketing categories used in NYS. Particular systems had greater than 90% recyclable paper content, except at the Town of Brookhaven where the mean was a little below 90% (two of the samples appeared to have been scraped off the tipping floor, leading to the inclusion of 12% to 15% fines). OCC (54.9%) tended to be found in greater amounts than mixed recyclable paper (39.3%) although that varied tremendously across the systems. Westchester County, for instance, collected about twice as much OCC as mixed recyclable paper while Ulster County collected almost three times as much mixed recyclable paper compared to OCC.

Dual-stream recyclable containers had higher levels of what we deemed non-recyclable materials, with 70.8% of the materials being target compounds of glass containers, ferrous containers, aluminum containers and foil, and #1 PETE or #2 HDPE plastic containers (Figure 7). The presentation here is not entirely consistent. The Town of Brookhaven and the Town of Smithtown do not collect glass curbside (they have drop-off glass collection only) and the Town of Southold and Jefferson County have separate glass collections in their drop-off programs. Delaware County, Jefferson County, Ulster County, Westchester County, and NYC all collect all numbered plastic containers as recyclables, and NYC specifically targets small appliances and other metal items in its curbside recyclable collection (other programs often informally recycle these materials); NYC also targets bulk plastics. Therefore, the definition of dual-stream container recyclables used here overcounts recyclables for two programs and undercounts them for at least five. Programs with higher conformance (lower “non-target materials” percentages) were Delaware County and Ulster County. 2017 NYC is listed with lower conformance to the dual-stream target materials, but on average collections there included over 14% metals (not included in the definition of dual-stream recyclables used here), and about 5% bulk plastics, also a target material in NYC recyclables set-outs.

Figure 7.

Dual-stream container recyclables. (clear = glass containers; solid = ferrous containers; gray = aluminum containers + foil; left-striped = #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics; right-striped = non-target materials).

Historically (1985–2010) glass had been the major portion of dual-stream container collections in the US, usually comprising 50% of the containers marketed from recycling facilities [27]. Glass was the greatest container constituent for only two of the systems reported on here: Town of Islip and 2017 NYC. A transition to plastics was especially notable in Delaware County. Lower glass percentages are at least partially due to programmatic differences for the Town of Brookhaven and the Town of Smithtown where glass containers are not included in the curbside program and at Jefferson County and the Town of Southold where the drop-off program collects them separately. Metal containers were collected at about the same rate as plastics in Jefferson County, but otherwise were not as important in the other seven systems.

In the 2021 NYS sample data, non-target plastics accounted for 46% of the mis-separated materials, although there was a great deal of variability in the data sets (Figure A10). Non-target plastics were also the greatest single element of non-target materials in the 2017 NYC data set, although this is somewhat misleading, because NYC includes bulk plastics in its MGP collection, and bulk plastics were 5% of NYC container recyclables. Bulk plastics are recovered by some of the other recycling programs informally, where facility operators process them and sell them, although they are not officially part of the recycling programs.

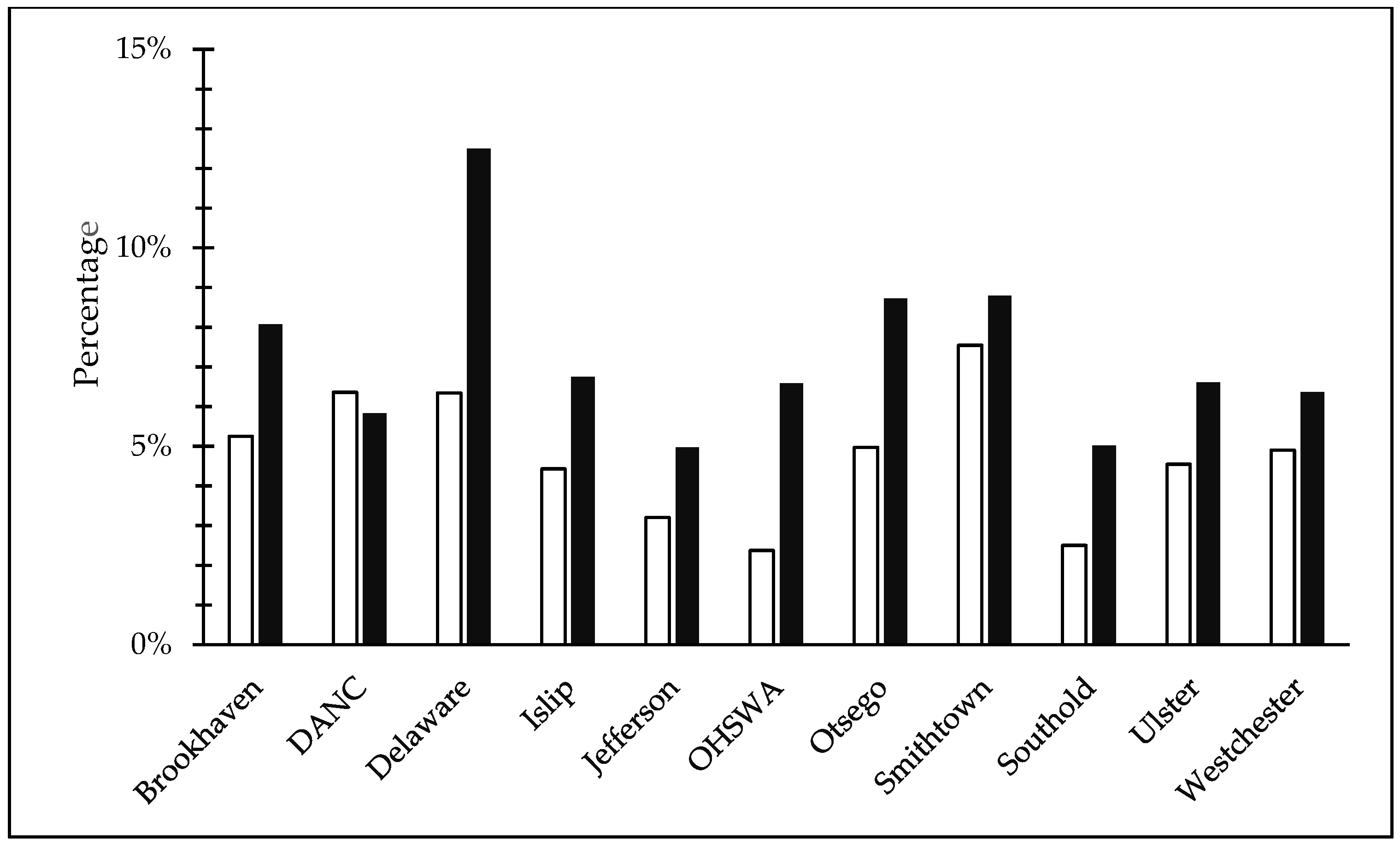

Two of the eleven systems exclusively collect recyclables in a single-stream collection program: OHSWA and Otsego County (both for drop-off and collection). Delaware County carters collect recyclables as a single stream (and so a sample from Delaware County is included here), but the Delaware County transfer station drop-off areas require residents to accomplish greater amounts of separation and so are included in the dual-stream recyclables discussion.

Single-stream data show that for 2021 NYS data 83.6% of the collection are targeted materials (Figure A11). Paper tended to dominate the collections (2:1 to 3:1 ratio for paper-to-containers for Otsego County and OHSWA) at 61.7% of the single-stream collections, although in Delaware County containers were collected as much as paper was 2019 OCRRA data, using a derived aggregate value for single-family and multi-family samples, were similar to OHSWA; 2018 EPA data, which were based on all recycling for 2018, were differently distributed because EPA counted other than curbside collections and also used net recycling data by material so there were no “non-target materials” in its recyclables assessments.

The 2021 NYS data showed an even split between OCC and mixed recyclable paper in single-stream collections, although in Delaware County there was about twice as much OCC as mixed recyclable paper. 2018 EPA data also showed that OCC was about twice as much recycled paper compared to mixed recyclable paper. 2021 NYS data for single-stream containers were split between glass (8.9%) and #1 PETE and #2 HDPE plastics (9.3%) with metals not being a large proportion (3.5%). The distributions of the containers and the percentages associated with glass and plastics varied considerably from system to system. Glass was the dominant container for Otsego County, 2018 EPA, and slightly so for 2019 OCRRA; plastics were the most common container in Delaware County, and a little less so in OHSWA. There was twice as much plastic in Delaware County as elsewhere. Unrecyclable plastics were the largest element of the “non-target materials” materials (Figure A12). Unrecyclable paper was a large component (5.1%) at OHSWA.

2.3. Combining Multivariate and Univariate Analyses

The multivariate analyses support broad categorizations of 2021 NYS waste streams and more targeted understandings of system similarities and differences. The univariate analyses provide particular materials’ similarities and differences but often do not provide a general context for the difference. Using these analytical techniques in concert improves each approach.

2.3.1. Major Waste Categories Differences and Similarities

Most obviously, there were clear differences in the composition of the total waste stream and disposed MSW compared to the three recyclable streams. This is similar to findings about NYC waste composition from 1990 to 2017 [16] where the comparison was to conglomerate recyclables (paper and container collections considered together). That dual-stream paper recyclables (intended to be OCC and mixed recyclable paper only) and dual-stream container recyclables (intended to be glass, metal, and #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastic containers only) are different from general disposed MSW and each other is not a major finding. Single-stream recyclables are essentially the same as the recyclables definition from the NYC study, and so it was good to confirm the results from Tonjes et al. [16] with a 16-variable waste composition data set that disposed MSW and (single-stream) recyclables were different (the NYC study used a seven-variable waste stream description). The results here show that single-stream recyclables are, as expected, akin to a mix of dual-stream paper recyclables and dual-stream container recyclables. They are more similar to disposed MSW waste composition than either dual-stream paper recyclables or dual-stream container recyclables. Dual-stream paper recyclables, being composed of almost entirely paper (95.5%, recyclable plus non-recyclable paper), were the most different of the large composition categories from dual-stream container recyclables, where paper was only a minor contaminant (3.1%).

Thus, it is unusual to find recyclables processing facilities (Materials Recovery Facility or MRF) that use the same processing equipment to manage both dual-stream paper loads and dual-stream container loads, although coincidentally both the Town of Brookhaven and the Town of Islip MRFs are designed to do this. Instead, most dual-stream recyclables systems use separate lines or even separate facilities to manage the different waste streams. Single-stream MRFs usually try to separate paper from containers as an initial processing step and then manage them along separate lines.

The PCA factor weighting implied that nearly 38% of the multivariate distance difference in the samples accrued from the paper composition. The univariate analyses show dual-stream paper was nearly all paper (95.5%). Paper was the single largest element of total wastes and disposed MSW: 23.1% to 34.1% of total wastes, 22.8% for 2021 NYS disposed MSW, and 11.9% to 25.8% for the comparison data sets (note paper was not the largest component for 2019 OCRRA and 2018 EPA disposed MSW). The difference between 95.5% and values in the range of 20% to 25% is large and helps to distinguish dual-stream paper recyclables from disposed MSW-total waste. Similarly, paper was 65.9% of the 2021 NYS single-stream recyclables, different from both the dual-stream paper recyclables paper composition and disposed MSW. In 2021 NYS dual-stream container recyclables, the paper composition was 3.1%, again distinguishing the broad categories clearly. Another important factor in the PCA weighting was #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastic containers (13%). These containers were 31.6% of the 2021 NYS dual-stream container recyclables, 0.4% of the dual-stream paper recyclables, and 9.3% of single-stream recyclables, creating clear differences among the categories. #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics composition did not distinguish between the total waste stream and disposed MSW data, nor were #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics in the total waste stream and disposed MSW data clearly different from dual-stream paper recyclables. #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics were 2.8% of 2021 NYS disposed MSW, 1.7% to 2.3% of total waste stream data sets and 1.3% to 2.8% of the comparison disposed MSW data sets. Food was the other major factor (10%) of the PCA analyses. Food was not a large portion of single-stream recyclables (0.8%), dual-stream paper recyclables (0.4%), and dual-stream container recyclables (2.4%), but it was for the disposed MSW data sets, with the 2021 NYS percentage at 20.5%, the total waste stream data ranging from 13% to 20.1%, and the comparison disposed MSW data ranging from 10.9% to 25.1%. Clearly, paper composition helped define the overall categorical differences, #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics distinguished across the recyclable categories, and food further separated disposed MSW and total waste stream categories from recyclables categories.

2.3.2. Within Category Similarities and Differences

The groups for total waste stream (mean within-group distance = 0.13) and disposed MSW (mean within-group distance = 0.15) were relatively cohesive; the groups for dual-stream paper recyclables (mean within-group distance = 0.21) and single-stream recyclables (mean within-group distance = 0.22) were more dispersed, and the dual-stream container recyclable groups had a larger dispersion (mean within-group distance = 0.32).

Dual-Stream Paper Recyclables

The dual-stream paper recyclables within-group distance was affected by the Ulster County data (mean within-group distance = 0.39), a set of green squares in the heat map, suggesting the data were different from the other system data sets for dual-stream paper recyclables. This is also reflected by being farther from the MSW and total waste stream data in Figure 1 (darker blue and violet squares) and the single-stream data (green and blue squares) and closer to the dual-stream container data (lighter violet squares). The mean sample data show that Ulster County had much less OCC (26.7%) and much more other recyclable paper (71.0%) than the 2021 NYS mean (53.9% OCC, 39.3% other recyclable paper) (see Figure A9). However, the difficulty in translating multidimensional data into two-dimensional data is shown in Figure 2 where the dual-stream paper recyclables are shown as a compact group of data without any outlier.

Single-Stream Recyclables

Similarly, the PCA multidimensional reduction in Figure 2 for the single-stream recyclables does not capture the dynamics of that cluster well. Two clear outliers (Delaware County and 2018 EPA) are apparent in the PCA, and the entire data group is much more dispersed than the dual-stream paper recyclables group, although the Euclidean mean within-group distances were essentially equivalent. 2018 EPA data are clearly distinct from the others (mean within-group distance = 0.36) and essentially equidistant from all of the other five points (minimum 0.35, maximum 0.37). Delaware County is somewhat separated from the other four data points (mean distance = 0.22) but not to the degree shown in Figure 2. 2018 EPA is different from the other single-stream systems because its recycling data include large percentages for yard waste (20.0%) and food (18.2%), which are not recyclables in single-stream recycling programs, and relatively small percentages for other recycled paper (12.4% for 2018 EPA, 29.6% for the 2021 NYS mean), glass (2.7% for 2018 EPA, 8.9% for the 2021 NYS mean) and #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics (1.2% for 2018 EPA, 9.3% for the 2021 NYS mean). Delaware County had less other recycled paper (14.5%), more glass (17.9%), and more #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics (19.2%) than the 2021 NYS mean, but not as dramatically different as the 2018 EPA data. That is why it does not map as far from the other single-stream recyclables systems.

Dual-Stream Container Recyclables

The dual-stream container recyclables data are much more scattered than the other data sets. The heat map shows that the Town of Islip maps far from dual-stream container recyclables data for the Town of Brookhaven, Jefferson County, and the Town of Southold (blue squares), and not especially close to Delaware County and the Town of Smithtown (green squares) and the mean 2021 NYS data (pale green square). The Town of Islip data are farther from the total waste stream and disposed MSW data (dark blue line), and single-stream recyclables (more blue squares) than other dual-stream container system data sets, and closer to dual-stream paper recyclables (paler violet) than the other dual-stream container data. Delaware County and Ulster County dual-stream container data also map farther from the total waste stream and disposed MSW data sets. Within the dual-stream container recyclables group they also have a few more green squares, along with the Jefferson County data. The PCA (Figure 2) does not capture this well, although the group is shown to be more diverse than any other major process cluster.

Instead, in the PCA 2017 NYC is identified as a clear outlier; the distance data shows it is relatively far from Town of Brookhaven (0.44), Town of Southold (0.42), Jefferson County (0.41), and Delaware County (0.40) but somewhat close to Westchester County (0.18); on average, it is only a little farther from other dual-stream container recyclables data points (0.34) as the within-group mean (0.32). 2017 NYC is identified as being closer to the total waste stream and disposed MSW data than other dual-stream container data (it is a paler green line in Figure 1).

In Figure 2 PCA, the Town of Islip is closely grouped with Delaware County and Ulster County (at the bottom of the dual-stream container recyclables cluster). However, the Euclidean distance from the Town of Islip dual-stream container recyclables to the Delaware County data was 0.50, and the distance from the Town of Islip data to Ulster County was 0.29. The distance from Ulster County to Delaware County was 0.22, strongly suggesting these three points nearly form a straight line with Ulster County in between (and none of them particularly close to each other). Town of Islip had a lot more recyclable glass (62.5%) than the 2021 NYS mean (27.6%), less #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics (17.9% compared to the 2021 NYS mean of 31.6%), less recyclable metals (7.6% compared to the 2021 NYS mean of 11.6%), and a smaller proportion of non-target materials (11.8% compared to 27.7%). These make the Town of Islip data different from other dual-stream container recyclables data sets. Ulster County (12.1%) and Delaware County (12.5%) also had low proportions of non-target materials, which may be why they grouped so closely to the Town of Islip in the PCA. 2017 NYC had the greatest amount of “non-target” materials in its data set (46.9%), although as explained earlier, in the NYC recycling program other metals, other plastic containers, and bulk plastics (as part of the classification “other plastics”) are acceptable recyclables (but for our purposes were classified here as “non-target materials”). The large proportion of non-target materials in the 2017 NYC data may be why the PCA sets it so far from the Town of Islip, Delaware County, and Ulster County data, although the weighted factors analysis suggests only food and other organics are important non-target materials in distinguishing programs from one another.

Total Waste Stream and Discarded MSW

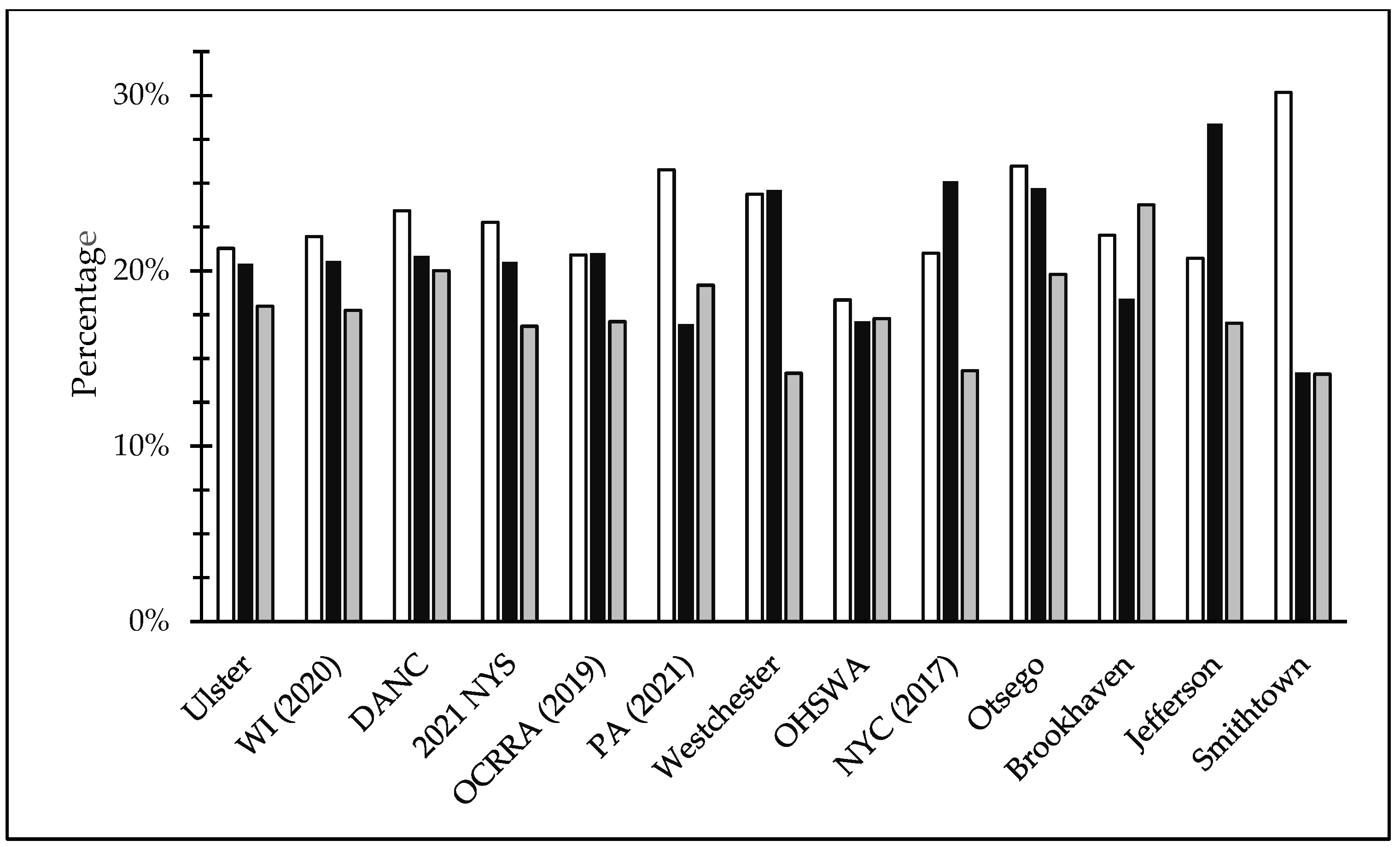

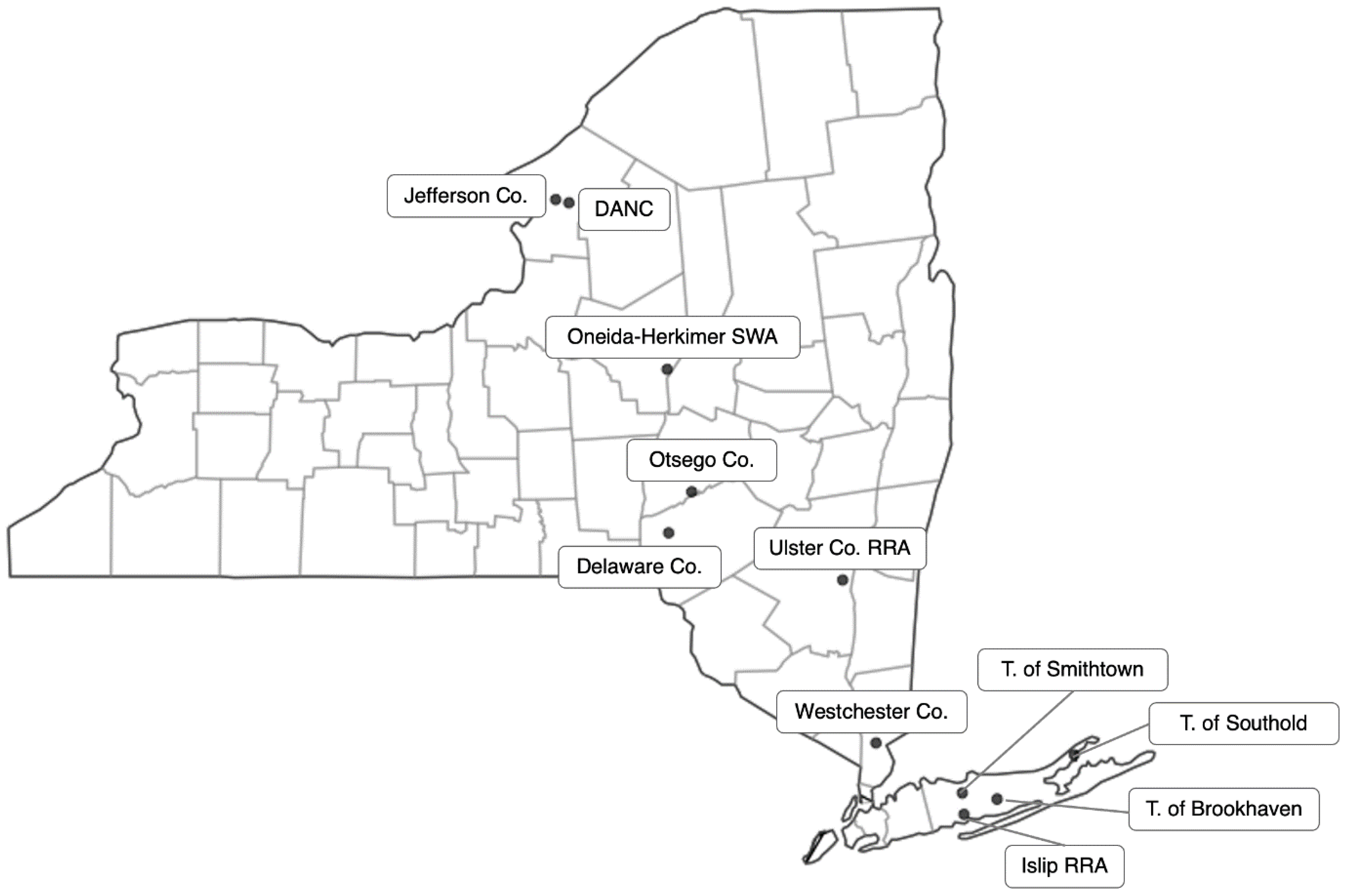

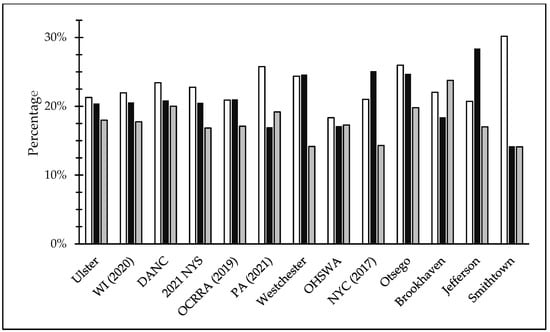

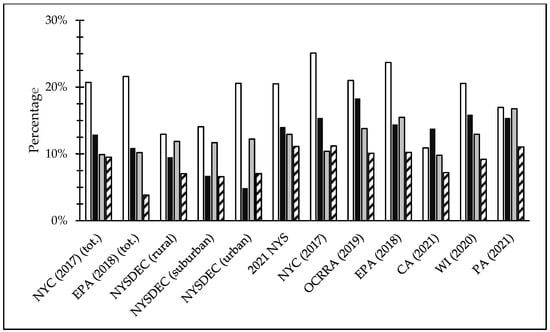

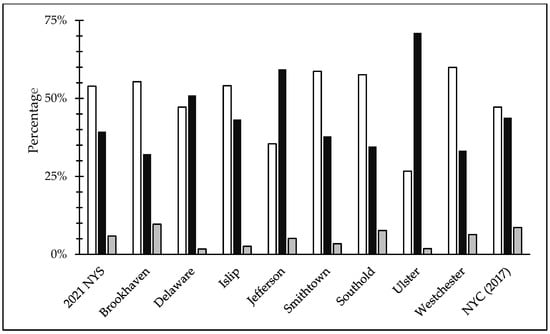

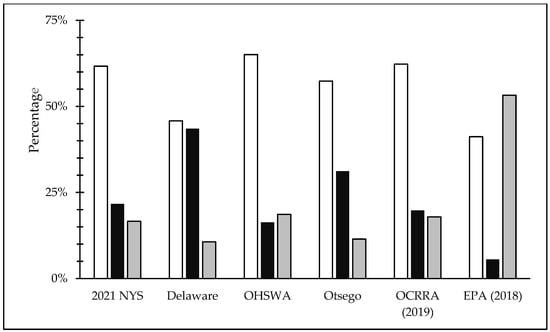

Most waste composition work concerns discards, not recyclables. Figure 3 (heat map of distance data) and Figure 4 (PCA) along with Table 4 represent the disposed MSW data in detail. Because the scales are reduced in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the similarities among different data sets can be harder to understand. However, Ulster County, mean 2021 NYS data, 2019 OCRRA, and 2020 Wisconsin data all have nine other data sets less than 0.10 away, meaning they serve as loci for the disposed MSW data (Table 6). The data sets close to Ulster County and 2020 Wisconsin are the same, meaning all 10 data sets are within 0.10 of each other. The “close to” 2019 OCRRA data set differs by one element, substituting Jefferson County for 2017 NYC, meaning it shares nine elements within 0.10 with Ulster County and 2020 Wisconsin. The mean 2021 NYS data set substitutes the Town of Brookhaven and the Town of Smithtown for OHSWA and Otsego County, meaning it shares eight elements with Ulster County and 2020 Wisconsin and seven elements with 2019 OCRRA. Thus there is a core of similar disposed MSW waste composition data sets in the 16-dimensional multivariate space. Its heart is Ulster County and 2020 Wisconsin, with DANC, mean 2021 NYS data, 2019 OCRRA, and 2021 Pennsylvania in close proximity, Westchester County, OHSWA, 2017 NYC, and Otsego County being very similar, and the Town of Brookhaven, Jefferson County, and Town of Smithtown a little bit on the fringe. This encompasses the darker orange relationships found in rows and columns 6–23 of Figure 3. These data points are not especially close to the total waste generation data, except for the 2017 NYC total waste generation. Excluded from the core data sets are disposed MSW data for Delaware County, Town of Islip, Town of Southold, 2018 EPA, and 2021 California. Figure 8 shows how the pattern associated with the major disposed MSW components (paper-food-plastics) is repeated for the central core data sets; the pattern is not as similar for those systems described as being farther from the core.

Table 6.

Concurrence of disposed MSW data sets, Euclidean distance < 10.

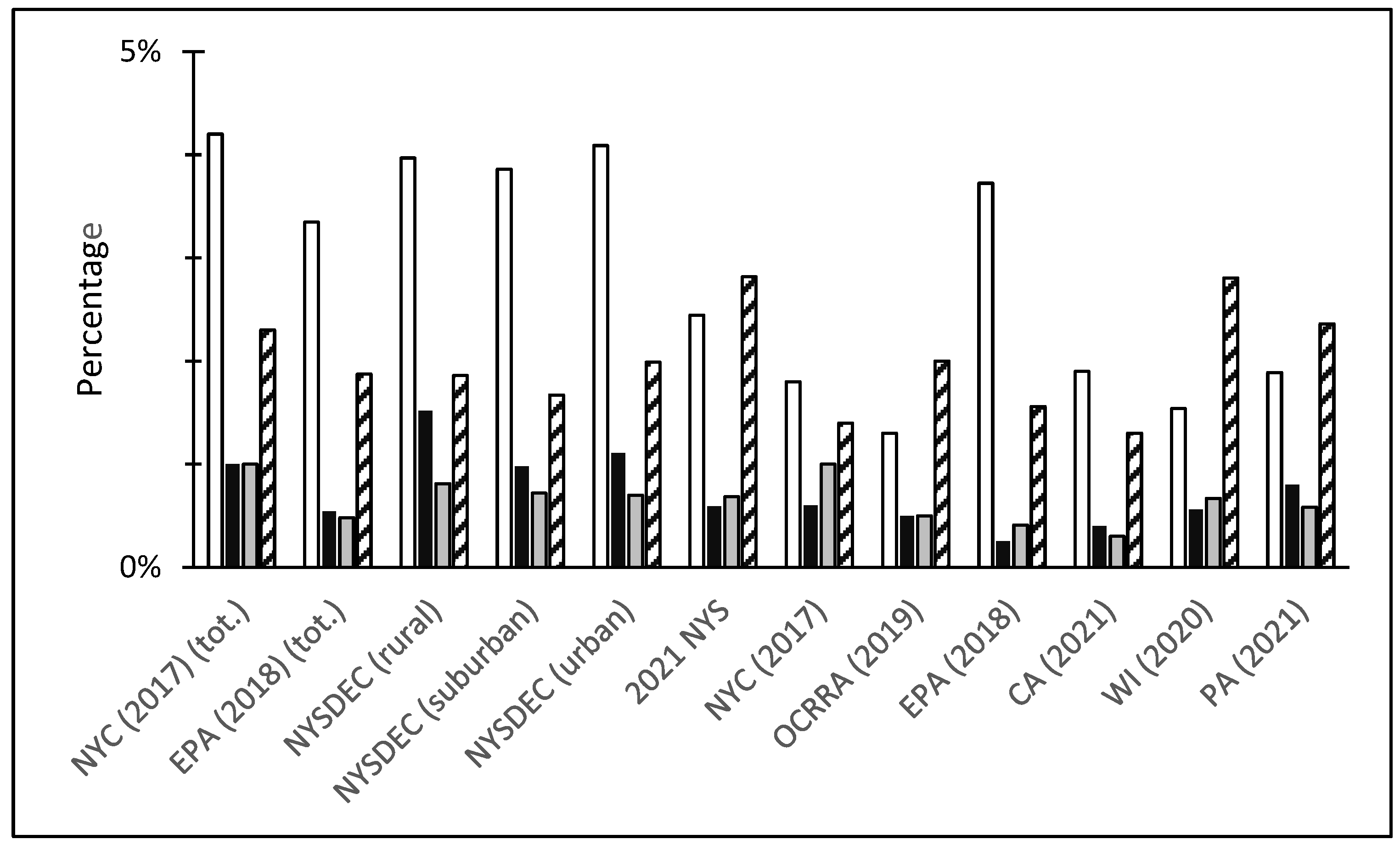

Figure 8.

Paper-food-plastics percentages in core disposed MSW systems. (clear = paper; solid = food; gray = plastics).

The PCA captures most but not all of the dynamics of the disposed MSW similarities (Figure 9). The core two data points (Ulster County and 2020 Wisconsin) are central and are surrounded by ranks of similar data as described above. However, the 2018 EPA disposed MSW data point is misplaced, and the 2017 NYC total waste data point is also too close to the core disposed MSW data points. The core is depicted in the PCA as too dispersed given the small Euclidean distance differences among the 13 more central systems.

Figure 9.

Reconfigured total waste-disposed MSW PCA. (red = core disposed MSW data sets: * = Ulster County, 2020 Wisconsin; ■ = DANC, NYS mean data, 2019 OCCRA, 2021 Pennsylvania; ● = Westchester County, OHSWA, 2017 NYC, Otsego County; ▲ = Town of Brookhaven, Jefferson County, Town of Smithtown; x = other disposed MSW; + = total waste stream).

In Figure 3 there are three notable features: the blue lines generated by the distances among the Town of Southold, Town of Islip, and 2021 California data sets and the other disposed MSW data sets. The blue lines indicate greater Euclidean distances in the comparisons. The Town of Islip and 2021 California data sets have a mean distance of 0.27 from other disposed MSW data sets; the closest either is to another data set is 0.19 (Town of Islip) and 0.20 (2021 California) (Table 4). The Town of Southold has a mean distance from other data points of 0.21. The closest data sets to the Town of Southold are Jefferson County, Westchester County, and 2017 NYC, all 0.14 away. All other Town of Southold distances to other data points are greater than 0.17. These minimum distances (0.17, 0.19, 0.20) are greater than the mean distances associated with all of the other disposed MSW systems. This identifies the Town of Southold, Town of Islip, and 2021 California data as outliers from the other disposed MSW data sets.

The other two data sets that are not in the core disposed MSW results are 2018 EPA and Delaware County. They both have mean distances of 0.16 from other data sets and have no other disposed MSW data point less than 0.10 away; the minimum distance for Delaware County was 0.10 and for 2018 EPA it was 0.11. This is not very different than the data for OHSWA (mean distance = 0.15, minimum distance = 0.07) and the Town of Brookhaven (mean distance = 0.14, minimum distance 0.08). However, OHSWA had five neighbors within 0.10, indicating it was more central in the overall disposed MSW data cluster; the Town of Brookhaven had two data points within 0.10, meaning it is not very close to the center but is on the fringes of the central core. 2018 EPA and Delaware County are not outliers but are not part of the central core of the disposed MSW results.

Differences in the distributions of the major disposed MSW data sets signal part of the differences between the core disposed MSW systems and these other five systems (Figure 10). 2018 EPA lacked paper (11.9% compared to the 2021 NYS mean value of 22.8%); Delaware County had too much paper (33.7%) and food (25.8% compared to the 2021 NYS mean value of 20.5%). Town of Southold data were dominated by food (34.7%). The Town of Islip lacked food (13.5%) and had fewer plastics (12.4%) compared to the mean 2021 NYS value (16.8%); 2021 California was lower in all three major categories: paper (15.6%), food (10.9%), and plastics (14.2%). Note that in the PCA weighted factor analysis for the total waste-disposed MSW PCA (Table 5), food was 19% of the weighting and the sum of the paper elements was 18%. This further supports the concept that the major elements are determinants of overall system differences.

Figure 10.

Paper-food-plastics percentages for core and outlier disposed MSW systems. (clear = paper; solid = food; gray = plastics).

Other important differences exist. The town of Islip had 26.4% yard waste; the 2021 NYS mean was 7.0%. No other 2021 sampled system had as much as 10% yard waste, making the Town of Islip data unique. Yard waste was an important weighting factor in the total waste-disposed MSW PCA (Table 5). The NYSDEC estimate for yard waste generation was 10.3% (suburban systems), meaning the NYS ban on yard waste disposal has had some although not complete effect on waste composition, making a comparison between the mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW value of 7.0% to the NYSDEC suburban generation rate of 10.3% (approximately one-third less).

For 2021 California, the single most anomalous data point was other inorganics, 26.8%. The mean 2021 NYS disposed MSW value was 5.9%. The greatest 2021 sampling value was 11.4% (for OHSWA). In the total waste-disposed MSW PCA weighted factor analysis, other inorganics were the third largest individual factor (Table 5). The consolidated category of other inorganics is the sampling categories of “other inorganics”, rechargeable batteries, and HHW. The sampling category of other inorganics was typically C&D but also included ceramics, dirt, rocks, and stones, among other non-degradable materials. The sampling categories from the 2021 California sort included by us under “other inorganics” covered video display devices, consumer electronics/small equipment, large equipment, concrete, asphalt roofing, gypsum board, rock-soil-fines, remainder-composite inerts/other, paint, used oil, lead batteries, other batteries, propane cylinders (<1 lb.), pharmaceuticals, remainder/composite HHW, bulky items, remainder/composite special wastes, solar panels, miscellaneous inorganics, and mixed residues (see Table A3). Mixed residues were the most troublesome sampling category, as we assume this was what we sorted as “fines”. Fines are the parts of a sample too small to be specifically sorted; they are classified in terms of proportions of other categories, and then the fines are allocated by these proportions into the other sampling categories. Apparently, in 2021, the fines in California were left in a specific category (“Mixed residues”). Mixed residues were 9.5% of all sorted materials in 2021 California. Typically our fines in 2021 included materials such as small pieces of paper (“other paper”), small pieces of plastic (“other plastic”), small pieces of unrecognizable organic materials (“other organics”), food particles, yard waste particles, and small particles of gypsum board or asphalt (C&D, therefore “other inorganics”). However, there was no way to parcel out the 9.5% of unsorted materials into categories absent any specific information; in the 2021 California sorting categories, there was already a designation of “other” materials under organics, and so our decision was to put this large portion of the sampling data into the consolidated category of “other inorganics”. If none of these “residues” were in fact other inorganics, the other inorganic category in 2021 California data would still have been 17.3%, still an anomalously large amount, and potentially a factor that would separate the 2021 California results from the other data sets. However, it is clear that the reporting of sampling data and our decisions regarding the management of that data contributed to the identification of the 2021 California data set as an outlier.

Overall, the PCA dimensional reduction (Figure 4) captures the exceptional nature of the 2021 California, Town of Islip, and Town of Southold data sets. It does not place the 2018 EPA data point well (Figure 9). It puts Delaware County as outside the core area: it is the point closest to the Town of Southold in the PCA, although the Euclidean distance data indicate that Jefferson County and Westchester County are slightly closer to Town of Southold than Delaware County is.

2.4. Summary of the Multivariate Analysis with Univariate Elements

Using a combination of multivariate distance analysis and standard individual waste composition results allows the identification of the 2021 NYS disposed MSW sampling data as being very similar to four comparisons, approximately contemporaneous data sets: 2020 Wisconsin, 2021 Pennsylvania, 2019 OCRRA, and 2017 NYC. The 2021 NYS disposed MSW data are different from the 2021 data from California, and 2018 EPA disposal data. In New York State, certain waste systems share similar overall disposed MSW characteristics. These include Ulster County, DANC, Westchester County, OHSWA, Otsego County, Town of Brookhaven, Jefferson County, and Town of Smithtown, in approximate decreasing order of general similarity to the mean 2021 NYS data. Some of the waste systems sampled in NYS had disposed MSW composition that was notably different from the more self-similar systems. These included the Town of Islip, the Town of Southold, and Delaware County.

Similar analysis showed that collected recyclables differed greatly in composition from disposed MSW, and that recyclables collection systems generated different quality recyclables. Dual-stream paper recyclables were almost all very similar to each other; the only system with very a different paper recyclable composition difference was Ulster County. Non-target materials in the dual-stream paper recyclables collections were 6.7%.

Dual-stream container collections have the greatest distance differences out of all of the collection types, partly because the dual-stream container collections themselves differed from system to system. For instance, the Town of Brookhaven and Town of Smithtown did not collect glass containers curbside, and the Town of Southold and Jefferson County had separate drop-off sites for glass. These affected the composition of container collections for these four systems compared to systems where glass set-outs were encouraged. Partly as a result, #1 PETE/#2 HDPE plastics (31.6%) were found to be more of the set-outs than glass (27.6%). In addition, our strict definition of “recyclable containers”, excluding #3–#7 plastics, which were collected for recycling at Delaware County, Town of Islip, and Ulster County, may have increased the “non-target” materials for those systems although the materials were properly sorted. State-wide, the non-target materials in dual-stream containers were set at 29.2%.

Single-stream waste composition data were fairly consistent across NYS, possibly because only three systems were sampled. Paper dominated single-stream recyclable set-outs (65.9%, 61.7% recyclable). Slightly more plastics (9.3%) than glass (8.9%) were in the container fraction. Non-target materials were found to be 16.6% of the set-outs.

If the mean 2021 NYS single-stream paper set-out rate of 65.9% can be considered as a general indicator of the paper/container recyclables set-outs split, it implies that 34.1% of recyclables set-outs are container recyclables. A blended NYS dual-stream recyclables contamination rate using those set-out values would be 14.3%. This is 14% less than the single-stream contamination rate of 16.6%, confirming the findings of [26] where single-stream recycling was found to increase contamination rates compared to dual-stream recycling (although [26] found single-stream recycling increased set-out amounts).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Collection

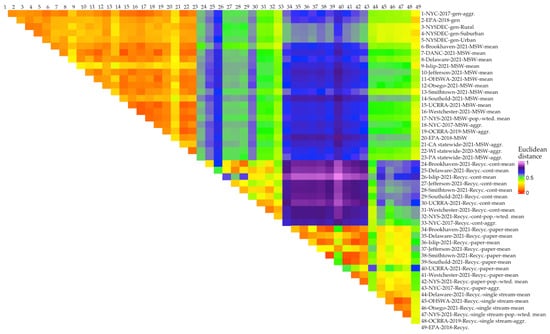

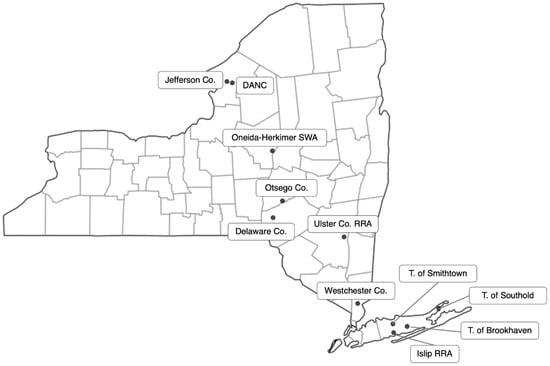

Disposed MSW and recyclables (and some Materials Recovery Facility (MRF) products and residues) were sorted at 11 sites in 2021: the Towns of Brookhaven, Islip, Smithtown, and Southold on Long Island, the New York City suburb of Westchester County, Ulster County in the Hudson Valley, Delaware County and Otsego County on the western portion of the Catskill Mountains, OHSWA in the Mohawk Valley, and Jefferson County and the DANC landfill on the west side of the Adirondack Mountains (Figure 11). The population served by these sites represents approximately 25% of New York State outside of New York City.

Figure 11.

Sampling locations map.

The Town of Brookhaven, the Town of Islip, the Town of Smithtown, Ulster County, and Westchester County were residential curbside collection programs with dual-stream recyclables collections. Sampling at the Town of Brookhaven was at the residential drop-off area (disposed MSW) for wastes from its transfer station and at the back of the Town MRF for recyclables. Sampling at the Town of Islip was in a cordoned-off section of the tipping floor at its waste-to-energy (WTE) plant for disposed MSW and at an outside storage bunker near its MRF for recyclables. Sampling at the Town of Smithtown was at a cordoned-off section of the tipping floor of its WTE plant for disposed MSW and at an isolated section of the tipping floor of its MRF for recyclables. Sampling at Westchester County was in a bay of its transfer station between the tipping floors for disposed MSW and its recyclables tipping floor (Westchester County has an MRF in the same building as its transfer station). Ulster County had curbside disposed MSW and dual-stream recyclables collection and also managed much commercially disposed MSW. Sampling at the Kingston Transfer Station was in a spare building adjacent to its MRF and near the transfer station. Sampling at the Newburgh Transfer Station was in a building bay adjacent to the tipping floor. OHSWA was a residential curbside collection program with single-stream recyclables collection and significant commercial disposed MSW management; OHSWA also gathered wastes from residential drop-off disposed MSW and recyclables transfer stations. Sampling in OHSWA was in an isolated area just outside the transfer station-MRF building. Jefferson County had a central residential drop-off site where residents partially sorted recyclables; some individual deliveries of residential and commercial disposed MSW and some residential and commercial carter routes were also received, as well as partially sorted loads of recyclables. Sampling of disposed MSW and residential drop-off recyclables was just outside of the transfer station; the partially-sorted recyclables were sampled in the processing facility on the tipping floor. Otsego County had two major and 10 minor transfer stations where drop-off disposed MSW and recyclables were brought by residents and businesses; the major sites also received route collections of disposed MSW and single-stream recyclables from carting companies. Sampling at the Oneonta site was just outside the transfer station for disposed MSW and just outside the recyclables transfer station for recyclables. Sampling at the Cooperstown site was in a building bay next to the residential drop-off area. Delaware County was similar to Otsego County except at the central waste site residents were required to partially sort recyclables and pure loads of sorted recyclables from businesses and carters were also received. Sampling of disposed MSW was at a cordoned off section of the tipping floor for the solid waste composting facility. Sampling of recyclables occurred in the receiving area for recyclables in the MRF while the MRF was not operating or receiving materials. DANC was a three-county regional landfill, receiving aggregated wastes from central transfer stations in Jefferson, Lewis, and St. Lawrence Counties and also deliveries from villages, individual businesses, and carting companies. Sampling at DANC occurred in an unused storage building near the major haul road to the landfill. More detailed descriptions of the waste programs at each location are included in Appendix B.

The 2021 sampling schedule is provided in Table A1. Participants were primarily solicited through project administrator contacts, cold calls, and contacts made at state conferences. Several notable organizations declined involvement because they had conducted their own waste categorization efforts (NYC and OCRRA). Liability issues (regarding Stony Brook University’s self-insurance program as a New York State agency and issues regarding graduate students and workman’s compensation) also affected the inclusion of several possible participants.

Specific site sampling protocols were negotiated by Stony Brook project managers and the various site operators. Most work plans called for three samples of disposed MSW and/or recyclables to be processed each day. Each sample was to be on the order of 100–200 kg (approximately 200–400 lbs). Most teams consisted of three to four graduate students with a supervisor, either a full-time professional or a faculty member; several undergraduates participated in summer sampling. Sample sizes were affected by misjudgments of weight-to-volume ratios; in most cases, the entire pile of materials delivered for sampling was sorted. Adverse weather (heat and wind) or lags in deliveries of desired materials could reduce the number of samples that were processed. Some days an extra sample or two were processed. Sample sources were largely selected by site operators; a research intention was to match disposed MSW and recyclables from the same source, and this was most often achieved.