Abstract

Ordinary concrete is an indispensable construction material of modern society which is used for everything from mundane road pavements to building structures. However, it is often used for non-load-bearing applications (for instance, insulating lightweight building units) where mechanical strength is not a priority. This leads to an avoidable depletion of natural aggregates which could instead be replaced by alternative waste materials capable of conferring to the material the desired performance while ensuring a “green” route for their disposal. Furthermore, the automation of production processes via 3D printing can further assist in the achievement of a more advanced and sustainable scenario in the construction sector. In this work, performance and environmental analyses were conducted on a 3D-printable cementitious mix engineered with ground waste tire rubber aggregates. The research proposed a comparative study between rubberized concrete mixes obtained by 3D printing and traditional mold-casting methods to achieve a comprehensive analysis in terms of the mix design and manufacturing process. To evaluate the environmental performance (global warming potential and cumulative energy demand) of the investigated samples, Life Cycle Assessment models were built by using the SimaPro software and the Ecoinvent database. The Empathetic Added Sustainability Index, which includes mechanical strength, durability, thermo-acoustic insulation, and environmental indicators, was defined to quantify the overall performance of the samples in relation to their engineering properties and eco-footprint.

1. Introduction

3D concrete printing is a new and advanced manufacturing paradigm for the construction industry. While the technology is still more expensive than the traditional building fabrication method, the additive manufacturing (AM) of concrete brings a lot of notable advantages and potentials [1]: (a) the ability to manufacture structures with minimal human input (automation) and in relatively short times; (b) the unique capability to manufacture complex designs and structures in a manner that is on-demand, on-site or off-site, customized, and, especially, automated; (c) the possibility of exploiting the design of the freedom of the additive fabrication to ensure an optimized material usage (therefore saving raw materials and leading to environmental advantages) while conferring to the printed structure multifunctionality in terms of mechanical properties, thermo-acoustic insulation, and aesthetic features. With the growing attention to the sustainable development goals identified by the United Nations in the Agenda 2030 [2], investigations on the environmental impact and sustainability of digital manufacturing in construction have intensified. Kaszyńska et al. [3] stated that 3D concrete printing technology consumes almost exactly as much material as is needed to produce a given structure, which results in a significant reduction in waste production and material consumption. Following an appropriate optimization of the printing process, the wastage reduction may be 60% greater than that of the ordinary production methods. In addition, the automation of construction would contribute to the reduction in the labor burden. According to Yang et al. [4], 3D concrete printing would shorten the construction time by 50–70%, while the labor cost could be lowered by about 50–80%.

3D-printable concretes require special characteristics to be properly used in additive fabrication. These mixtures are designed based on four primary printing parameters, namely, pumpability, extrudability, buildability, and inter-layer bond strength [5,6]. Pumpability is the ability of the material to be extruded without phase separation under the application of pressure [5]. Extrudability refers to the material’s ability to be extruded without discontinuity or deformation [6]. Buildability refers to the ability of the printed concrete layer to hold the layers above other layers without failure. Inter-layer bond strength represents the adhesion force between the printed filaments affecting the hardened-state properties of the concrete (mechanical strength and durability) [6]. Such properties are governed by the rheological characteristics of the cementitious mix as well as the curing conditions, the printing time gap, the layer geometry, and the environmental conditions influencing the surface properties [5]. Due to such challenging printing requirements, large amounts of binder (especially Portland cement) and fine natural aggregates are used in printable concrete, promoting the well-known environmental criticalities already encountered in the production of traditional cementitious mixtures, i.e., greenhouse emissions, energy consumption, and the depletion of natural resources [7]. In this sense, the latest efforts on 3D concrete printing technology are focused on designing “greener” cementitious mixtures, following two possible routes: (1) implementing low-carbon binders, including alkali-activated cements (AACs) [8], sulfoaluminate cements (SACs) [9], and magnesium potassium phosphate cements (MPPCs) [10], or (2) using recycled aggregates or selected waste materials in place of ordinary natural aggregates, providing valuable opportunities for a circular economy while improving the sustainability and functionality of 3D-printable mixtures [5,11,12].

Ground tire rubber derived from end-of-life tires (ELTs), also recognized as ground waste tire rubber (GWTR), demonstrated a huge potential for its use as an alternative aggregate in non-structural cementitious mixes. GWTR can be used to produce lightweight and ecological concretes for specific applications and tailorable properties if a proper selection of the number and shape of tire particles is performed [13]. Thirty-year studies on rubberized concrete technology highlighted that the replacement of ordinary aggregates with GWTR leads to a reduction in the concrete’s brittleness, adding various engineering benefits, such as a higher ductility and energy-dissipative performance, improved impact strength, freeze/thaw protection, greater vibro-acoustic damping, and higher heat insulation properties [13,14,15]. While dramatically sacrificing mechanical strength, the rubberized concrete was found to be a good candidate for a wide range of low-strength applications, including highway shock absorbers, sound barriers, Jersey barriers, sidewalk panels, non-load-bearing walls, insulating facades, and precast roofs for “green” buildings [16]. A further aspect motivating the use of recycled tire rubber as an alternative aggregate is its considerable availability, which is capable of potentially supporting the need for the mineral aggregate required in traditional cement mixtures. A report by the European Tire and Rubber Manufacturers Association (ETRMA) estimated that around 30 Mt of ELTs were generated globally in the last 4 years. In Europe, the ELT market recognizes material recycling as the primary handling route for waste tire management (50%) [17].

While the knowledge and peculiarities of “traditional” rubberized concrete mixes are well known and consolidated among the scientific community, the latest efforts have focused on designing and optimizing these mixtures for AM processes. In recent works [18,19,20], the authors integrated GWTR particles into printable cementitious mortars in the total replacement of sand, demonstrating interesting effects on the fresh and hardened properties. Over the “plain” printable material (0% v/v rubber), an increase in fluidity without affecting the water content [18,19], improved layer-by-layer adhesion [18,19], higher mechanical isotropy counteracting the influence of inter-filament defects on the strength behavior [18,19], a reduction in pore size distribution [19], a superior acoustic insulation performance [19,20], and a greater thermal resistance [20] were verified. Additionally, the appropriate optimization of the mix design and printing characteristics led to “fully-rubberized” materials with a mechanical strength performance that satisfies the requirements for RILEM class I lightweight structural concretes [20]. From these pioneering studies, other researchers approached the implementation of rubberized concrete mixes in digital fabrication. Ye et al. [21] developed and characterized a novel ultra-high ductile concrete (UHDC) for 3D printing modified with crumb rubber in the partial replacement of sand (40 v/v%) to attain a high ductility performance. Liu et al. [22] studied the effect of cement-coated GWTR aggregates (15% w/w replacement of river sand) in 3D-printed rubberized mortar investing by microstructural and mechanical analysis, along with the influence of the coating quality on the interfacial bonding between the rubber and cement matrix. Aslani et al. [23] incorporated waste crumb tire rubber aggregates in fiber-reinforced cementitious composites manufactured through 3D concrete printing. The developed composites satisfied the compressive strength requirements of 25 MPa for lightweight structural applications.

Aim of the Work

Although the implementation of GWTR in 3D concrete printing would seem promising in developing lightweight, energy-effective, and mechanically performing structures, the current literature shows a scarcity of studies providing information about the quality and eco-impact of the AM process when waste materials are employed as concrete aggregates. Motivated by the modern environmental considerations regarding materials and production processes, this work proposes a quantitative analysis via life cycle assessment (LCA) on Portland-based mixtures designed for extrusion-based 3D printing process that incorporate GWTR in the total replacement of the mineral aggregate. A comparative analysis was performed with similar cementitious mixes obtained by a traditional mold-casting method to carry out an environmental and performance assay including the influence of different fabrication processes (mold-casting and 3D printing) and mix designs (cast and printed). The Empathetic Added Sustainability Index (EASI), which takes into consideration design engineering properties, durability, and sustainability issues of the developed materials and processes, was proposed as a performance indicator in the comparison. Innovatively, the present research explores, by a combined environmental-performance analysis, the viability of integrating, in the construction industry, greener alternative materials and digital manufacturing processes aimed at minimizing the ecological damage and promoting the sustainable management of waste and efficient natural resource utilization.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Performance Characterization of Materials

The performance indicators of 3D-printed and mold-casted CTR and RuC samples are listed in Table 1. The majority of values were taken from previous research works conducted by the authors. Specifically, the literature sources for printed samples are Refs. [18,19,20]. For mold-casted mixtures, the values of Rc, Φ, and SRI were collected by Refs. [24,25]. The k-values, instead, were specially determined for this manuscript.

Table 1.

Performance indicators of 3D-printed and mold-casted samples.

2.1.1. Mechanical Strength Indicator

The Rc results revealed a clear difference in the mechanical performance between 3D-printed and casted mixtures. As expected, replacing sand with GWTR reduced the mechanical strength of concrete. The 3D-printed samples exhibited the best compression loading capacity compared to mold-casted counterparts. Possible explanations for this evident divergence can be traced back to three factors:

- Mix design. Printable mix designs are technologically advanced formulations and well optimized for extrusion-based AM, which necessarily involves a certain content of chemical admixtures and fillers (generally not required in traditional mixes for casting) aimed at ensuring adequate rheology for 3D printing, reduced w/c ratios (less than ordinary values for casting), and the enhanced strength and microstructural development of concrete [26].

- GWTR and cement contents. The special rheology of the printable mixtures would limit the use of high contents of GWTR aggregates. Due to their hydrophobicity and pozzolanic inertia, a higher rubber content drastically reduces the workability of the fresh concrete paste requiring a high dosage of mixing water [27], which is not suitable in terms of fluidity requirements for the extrudability and buildability in AM processes. By comparing the mix designs in below, it can be observed that, with the same volume (1 m3), the rubber content incorporated in the 3D-printable rubberized formulation is about 44% lower than that in the c-RuC mix. As can be expected, a low content of GWTR would imply the preservation of a good mechanical performance. As also confirmed by the literature on 3D concrete printing technology, a higher binder dosage is used in printable cementitious mixtures compared to conventional concrete [28]. In addition to providing adequate printability properties, high cement amount over aggregate content improves the load-bearing capacity of concrete. However, the performance improvement led to clashes with the environmental criticality resulting from the use of high rates of the binding material (Portland cement).

- Manufacturing method. As pointed out by several authors [29,30], rubberized concretes made by mold-casting process could suffer from an inhomogeneous distribution of polymer particles into the matrix. Due to their low unit weight and poor bonding with the cement, there is a tendency for the tire aggregates to move upwards during the vibration, promoting a greater concentration of rubber particles in the upper layer of the molded samples. The non-uniformity in the hardened material is detrimental to the mechanical properties. On the other hand, extrusion-based 3D printing production allows for a more homogeneous dispersion and the alignment of the rubber aggregates due to both the layer-by-layer deposition technology and the rheology of the material, which is designed to ensure rapid mixture hardening after deposition and, consequently, better stabilization of the GWTR inside the cement matrix. This enhanced distribution of rubber aggregates would lead to a superior mechanical performance of the printed specimens compared to that of the mold-cast ones [31]. In addition, the better mechanical behavior of the printed mixes compared to that of the casted ones can be traced by the contribution of the pumping system in the 3D printing process to the material’s compaction. The application of high pressure during the extrusion would ensure a greater densification of the 3D-printed parts compared to that of their molded counterpart [26], with a consequent improvement in the mechanical performance and microstructural quality (fewer voids and less porosity).

2.1.2. Durability Indicator

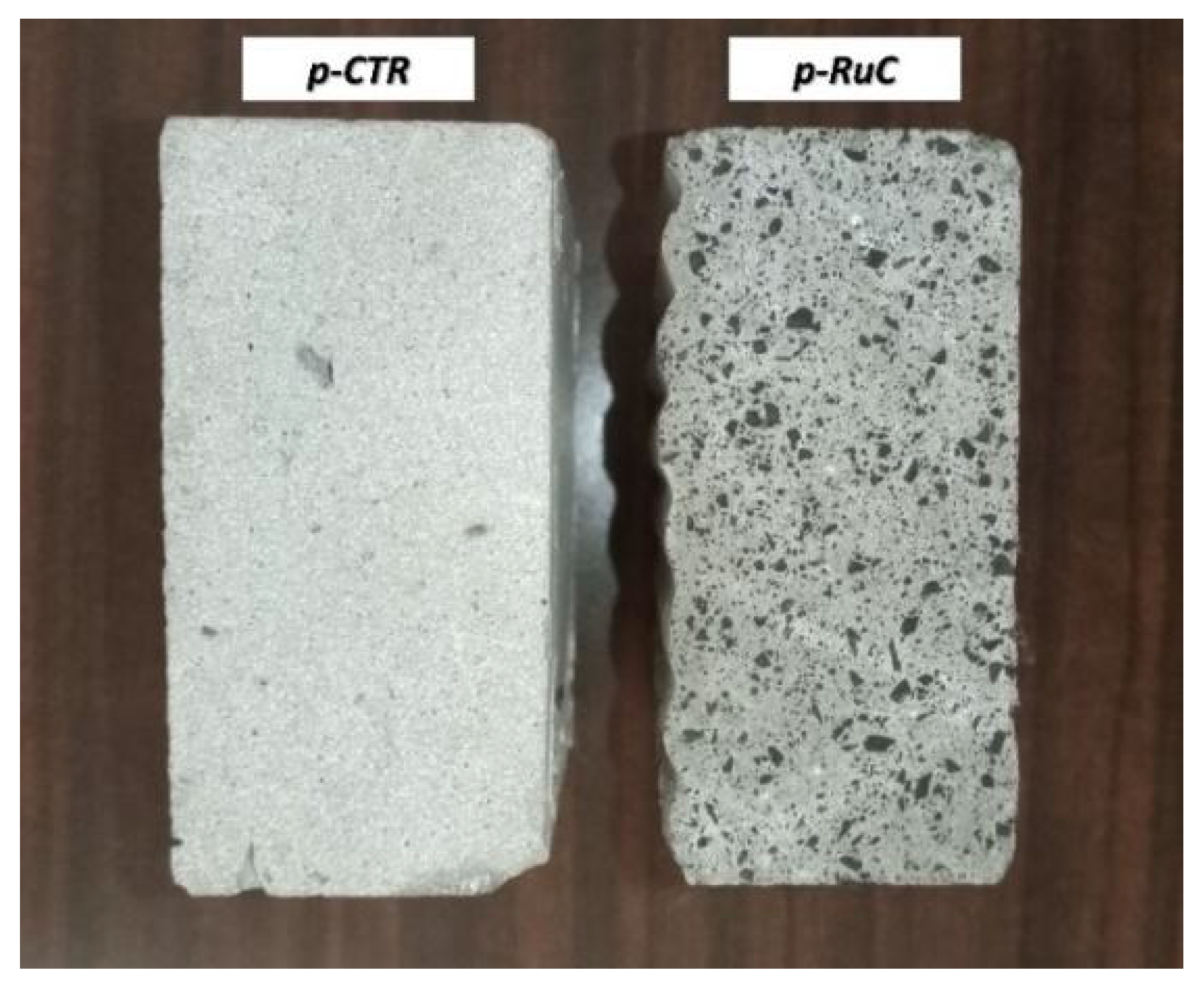

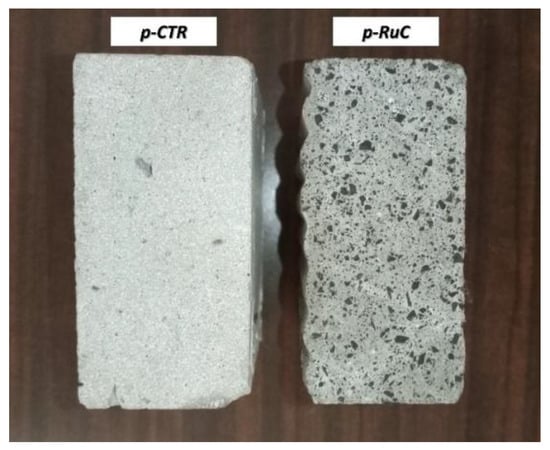

The Φ results show that the permeable porosity slightly increases with the addition of rubber regardless of the type of manufacturing process. GWTR worked as an air-entraining agent which can enhance the porosity of concrete. Furthermore, the weak cohesion between the rubber and cement matrix leads to interfacial gaps, promoting the material’s permeability [32]. Based on such evidence, the better behavior of the rubberized mixtures obtained by AM is mainly to be attributed to the lower content by weight of the GWTR incorporated. The densification implemented by the extrusion process and the lower w/c ratios involved in the 3D-printable mix designs are factors contributing to the lower porosity of the printed samples. Figure 1 shows the cross-section of the p-CTR and p-RuC samples. It can be verified that the printed parts exhibited a bulk-like microstructure where no inter-filament voids and inter-layer defects were detected, indicating printing process parameters and printable mix designs that are well optimized for AM. Avoiding the occurrence of stacking voids is a desirable requirement in 3D concrete printing technology for increasing the mechanical stability of printed structures and minimizing their vulnerability against environmental deterioration effects [33].

Figure 1.

Cross-section of the 3D-printed slabs: p-CTR (left) and p-RuC (right).

2.1.3. Energy-Efficiency Indicators

Regardless of the production process (3D printing and mold-casting), the full replacement of sand with GTWR enhanced the thermo-acoustic insulation properties of concrete by means of a decrease in the k-value and an increase in the SRI. The use of tire rubber aggregates has a broad prospect in “green” building for applications in which thermal resistance and noise insulation are primary requirements (e.g., building partition walls) [34]. However, by comparing printed and mold-casted samples, different amounts of improvements in thermo-acoustic insulations were observed. With respect to the p-CTR mix, the rubberized sample (p-RuC) led to a decrease in the k-value of 36% and an increase in the SRI of only 2%. Conversely, the mold-casted sample performed better in terms of thermal and acoustic insulation properties, showing a decrease in the k-value of 79% and an increase in the SRI of 28%. This result is not related to the type of manufacturing process but rather to the mix compositions of the samples under investigation. A higher GWTR content per unit volume incorporated in the mold-casted formulations, although drastically reducing the mechanical strength of the material, significantly improved its insulation performance. In this context, one can see the benefit of the design flexibility of 3D printing in building complex concrete structures (which are challenging to create with conventional manufacturing methods) with functional geometries in terms of thermo-acoustic damping. For instance, different cavity patterns in wall elements can be easily implemented by additive fabrication to improve the thermal and noise insulation performance while reducing the energy consumption within the life cycle of the concrete structure [35].

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Results

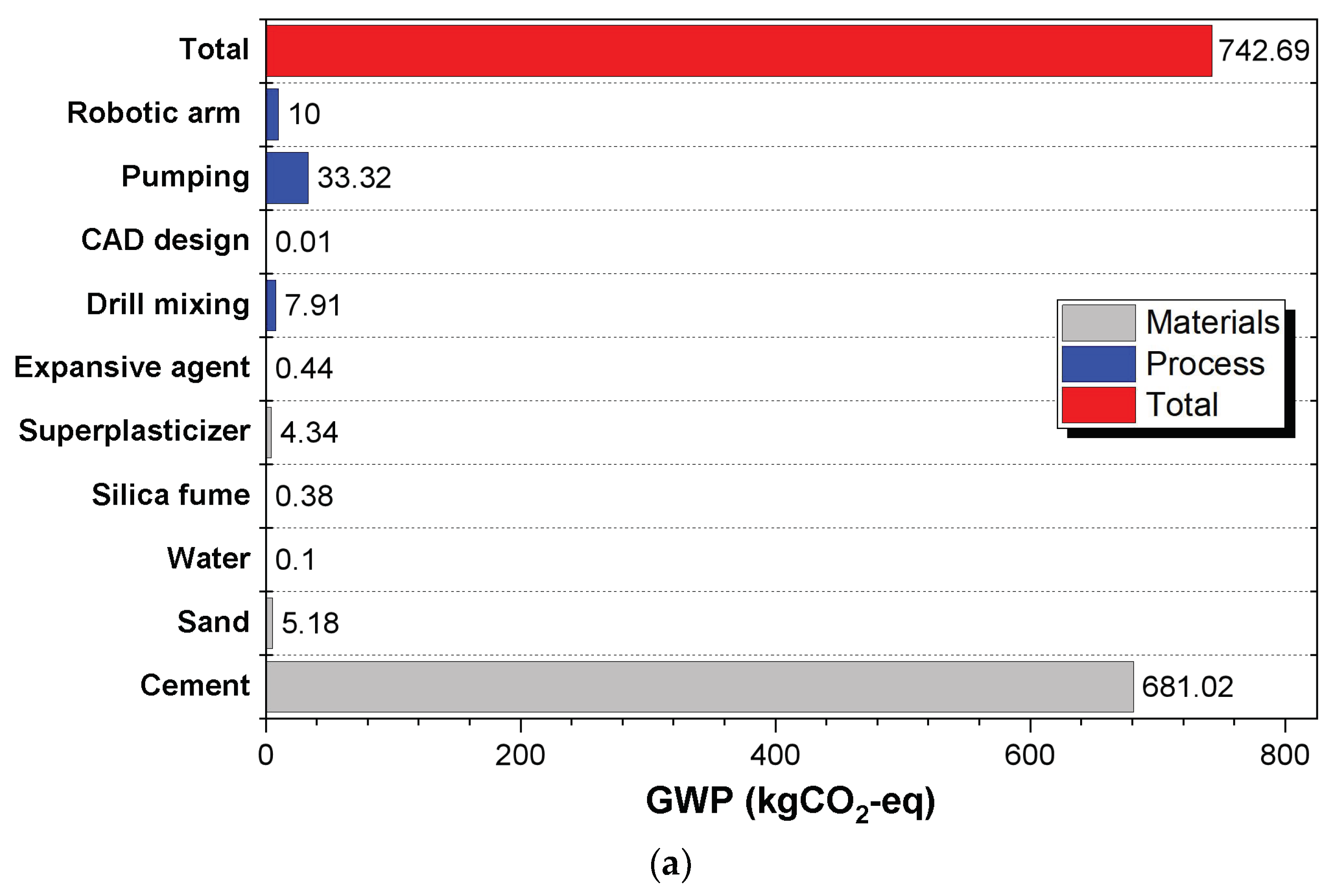

2.2.1. Global Warming Potential (GWP) Analysis

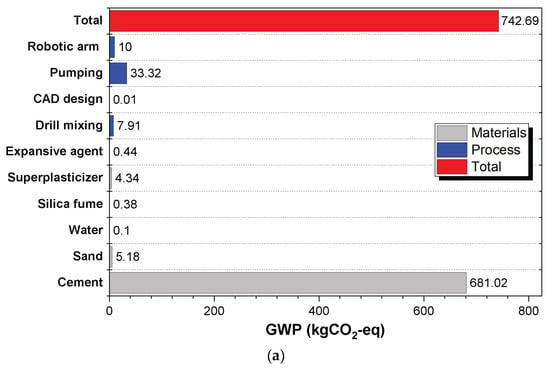

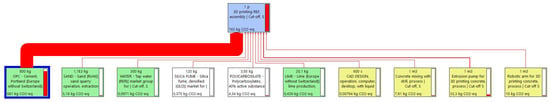

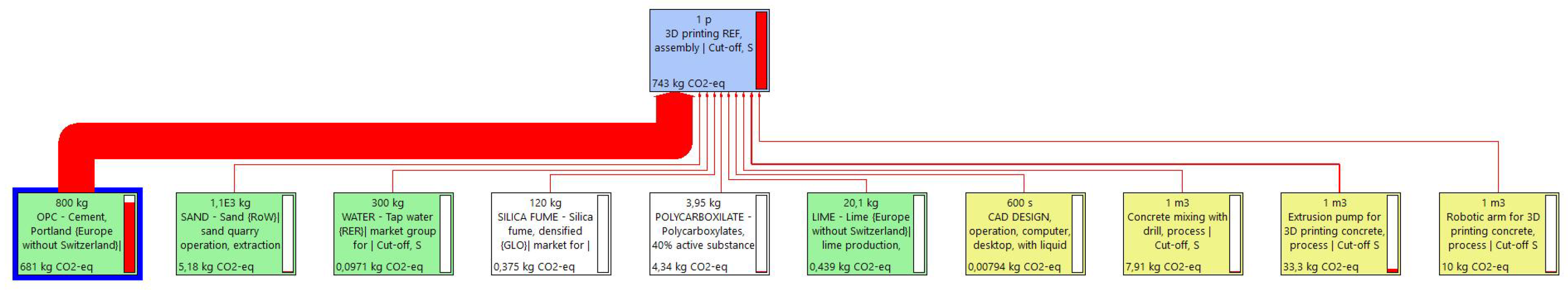

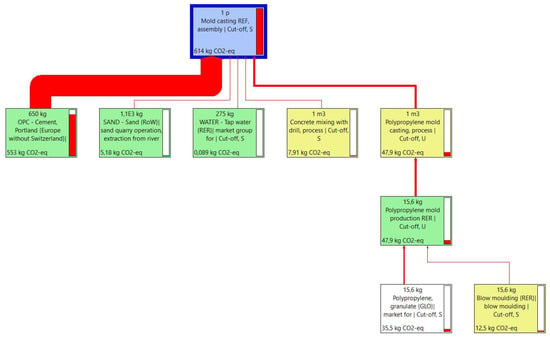

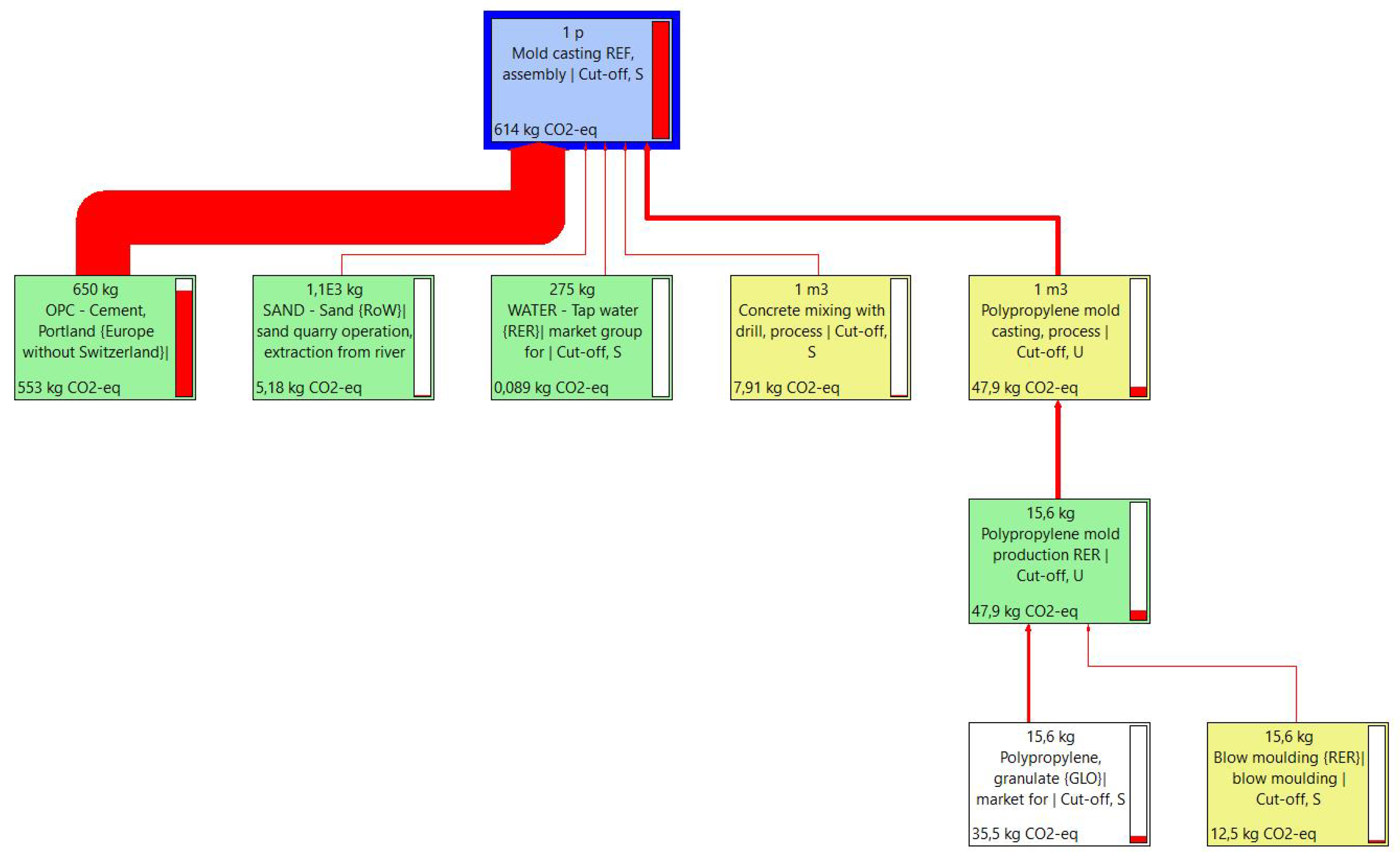

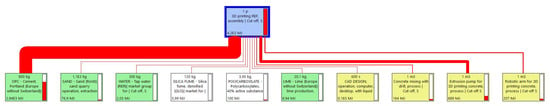

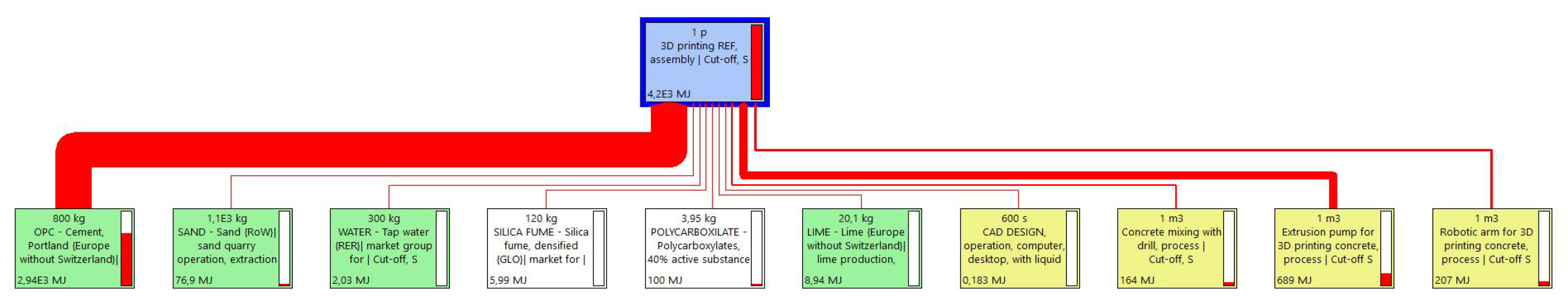

The graphs in Figure 2 compare the overall GWP values of 3D printing (Figure 2a) and mold-casting (Figure 2b) processes with respect to the CTR mix, highlighting the eco-impact contribution of mix design ingredients and the phases of the manufacturing processes. The SimaPro networks of these processes are detailed in Appendix A (Figure A1 and Figure A2, respectively). For both processes, the most significant impact was due to the binding material (Portland cement), contributing about 90% of the overall GWP. This result agrees with those found in others research works [36,37]. The higher content of the cementitious binder used in the p-CTR mix, in addition to the minor impact induced by the chemical admixtures (0.7% of the overall carbon footprint), resulted in a higher GWP value compared to that of the c-CTR mix. On the side of the manufacturing process, excluding the drill mixing operation, which is considered similar for both mixtures, it was noticeable that the production of plastic mold for concrete casting (47.91 kgCO2-eq) exceeded the 3D-printing line (43.33 kgCO2-eq), which included the CAD design, pumping, and robotic arm motion, in terms of environmental impact. This finding demonstrates that the adoption of formworks or molds in a traditional manufacturing approach accounts for a considerable rate of eco-impact and energy consumption in concrete processing. A comparative study between extrusion-based 3D concrete printing construction and the precast technique conducted by Weng et al. [38] ascertained that formwork-free manufacturing, provided by AM, outperformed ordinary fabrication concerning the economic cost, sustainability, and productivity. This was ascribed to the heavy expenses and environmental burdens associated with the manufacturing of formworks used in the mold-casting approach. In our research, the reduction in the GWP value was about 9.5% when the 3D-printing production chain was considered in place of mold fabrication. Further benefits that AM can bring in terms of customized design and optimized material usage must be addressed.

Figure 2.

GWP results: (a) p-CTR and (b) c-CTR.

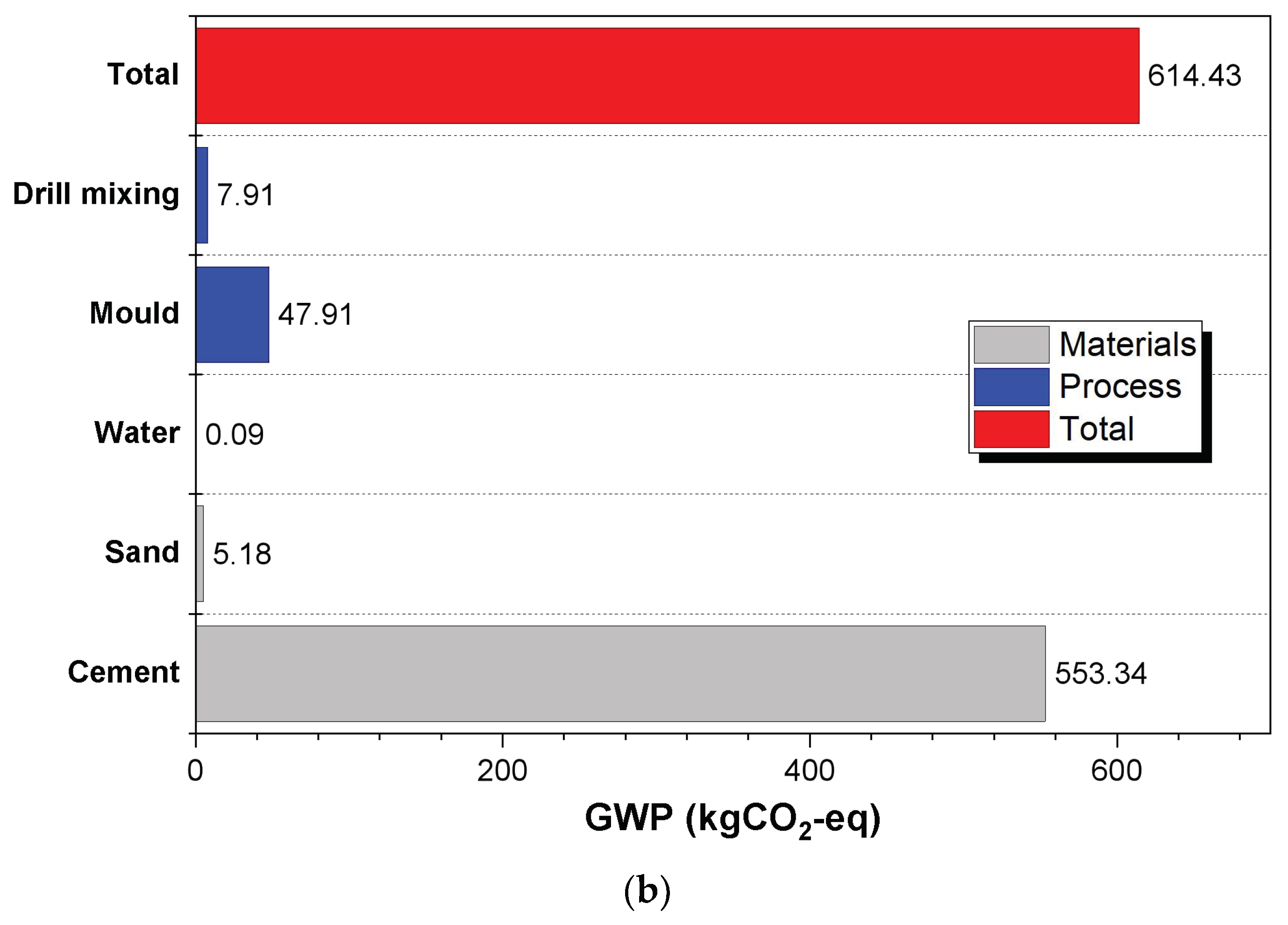

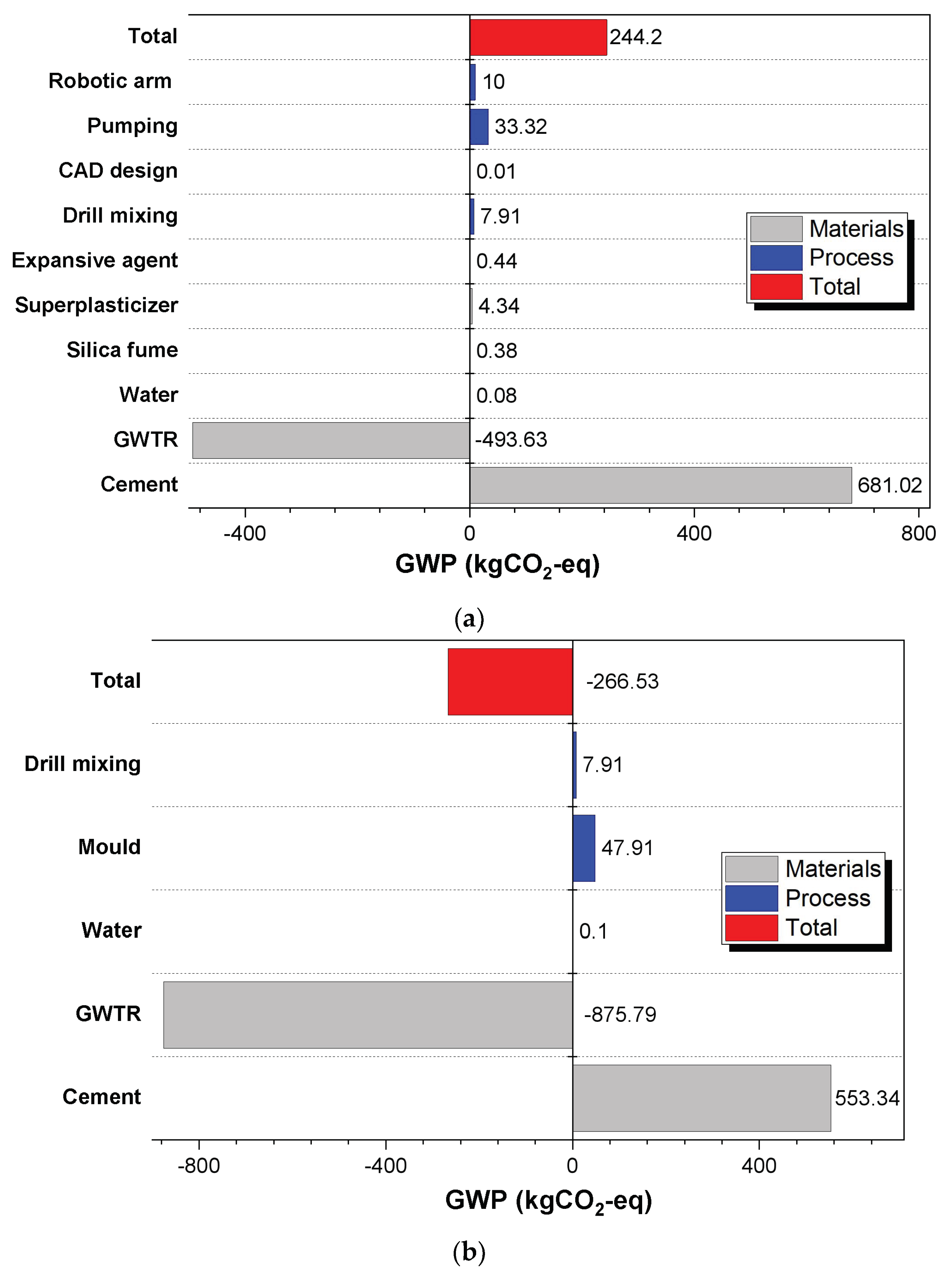

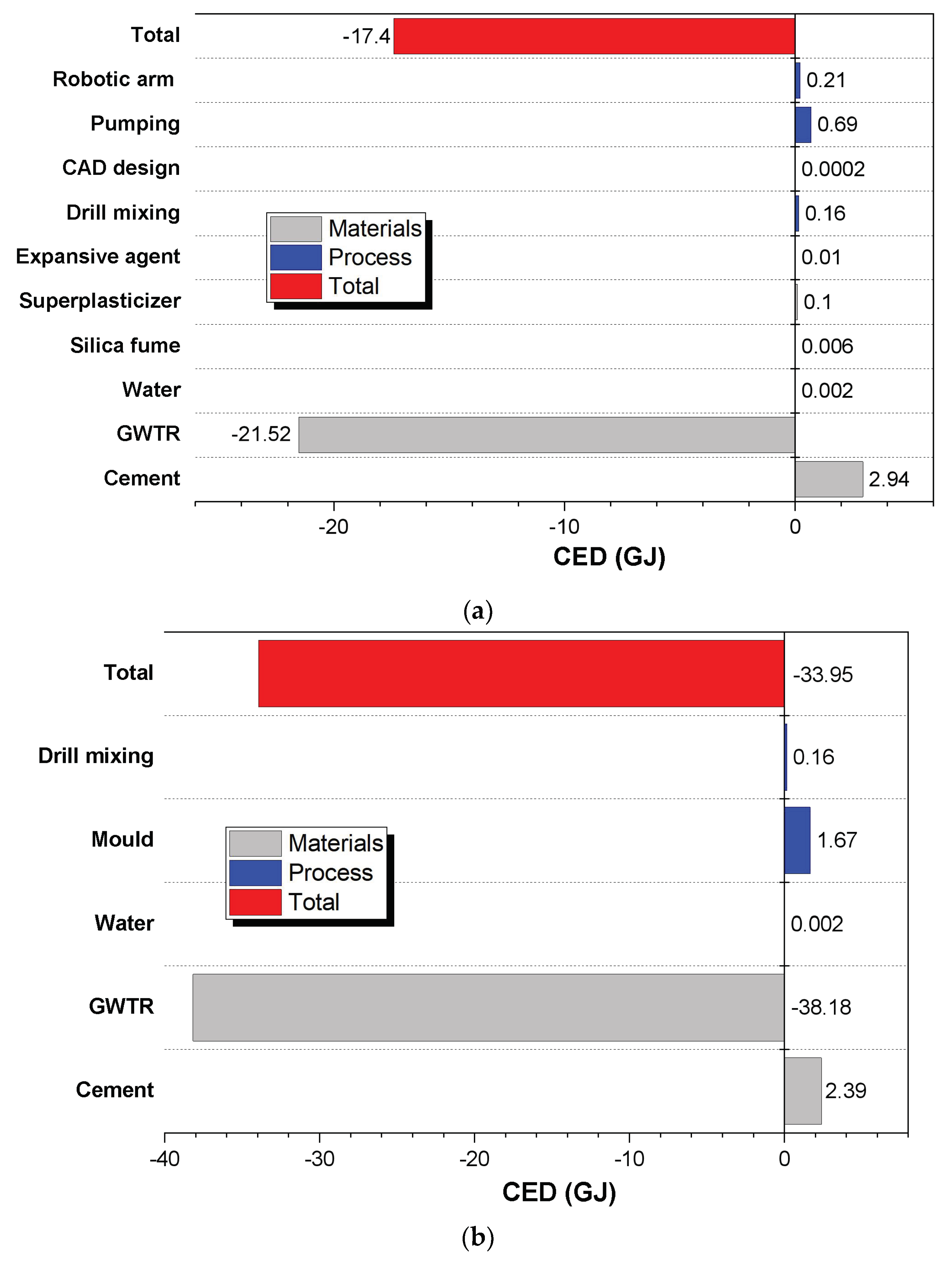

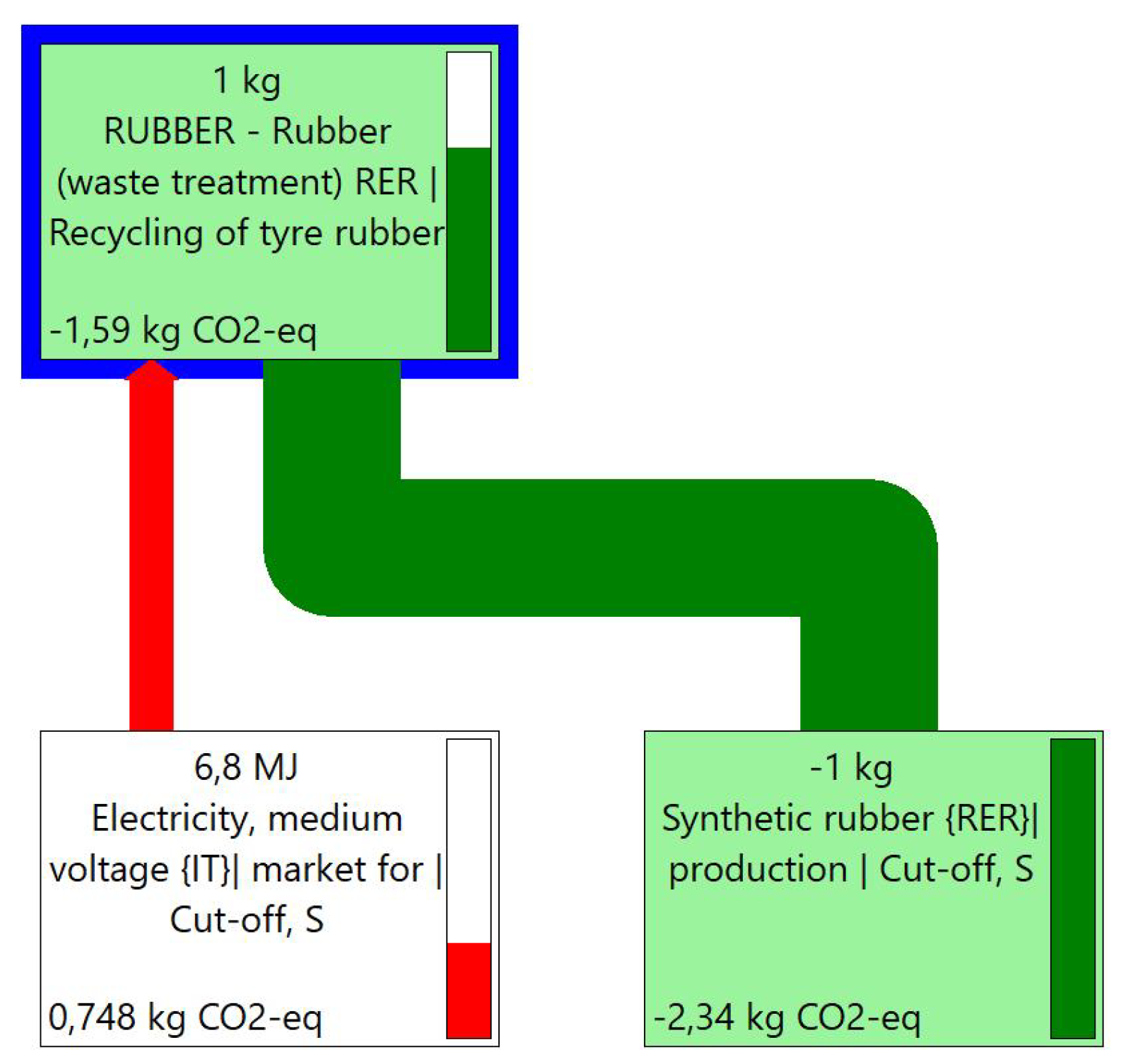

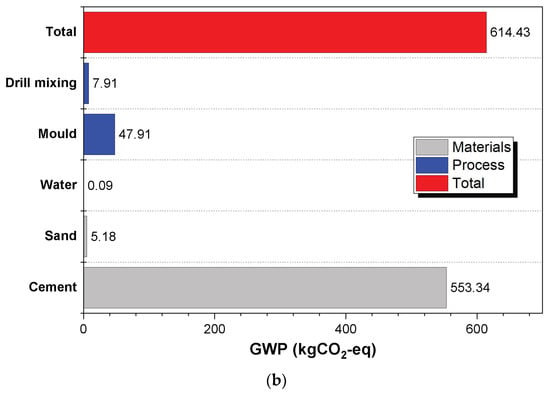

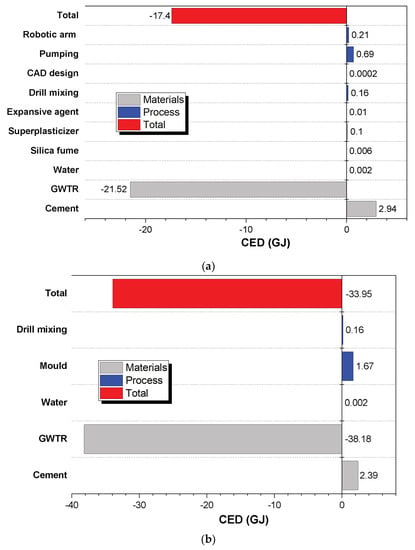

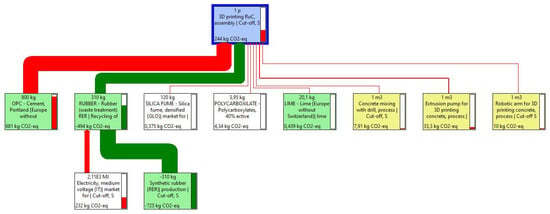

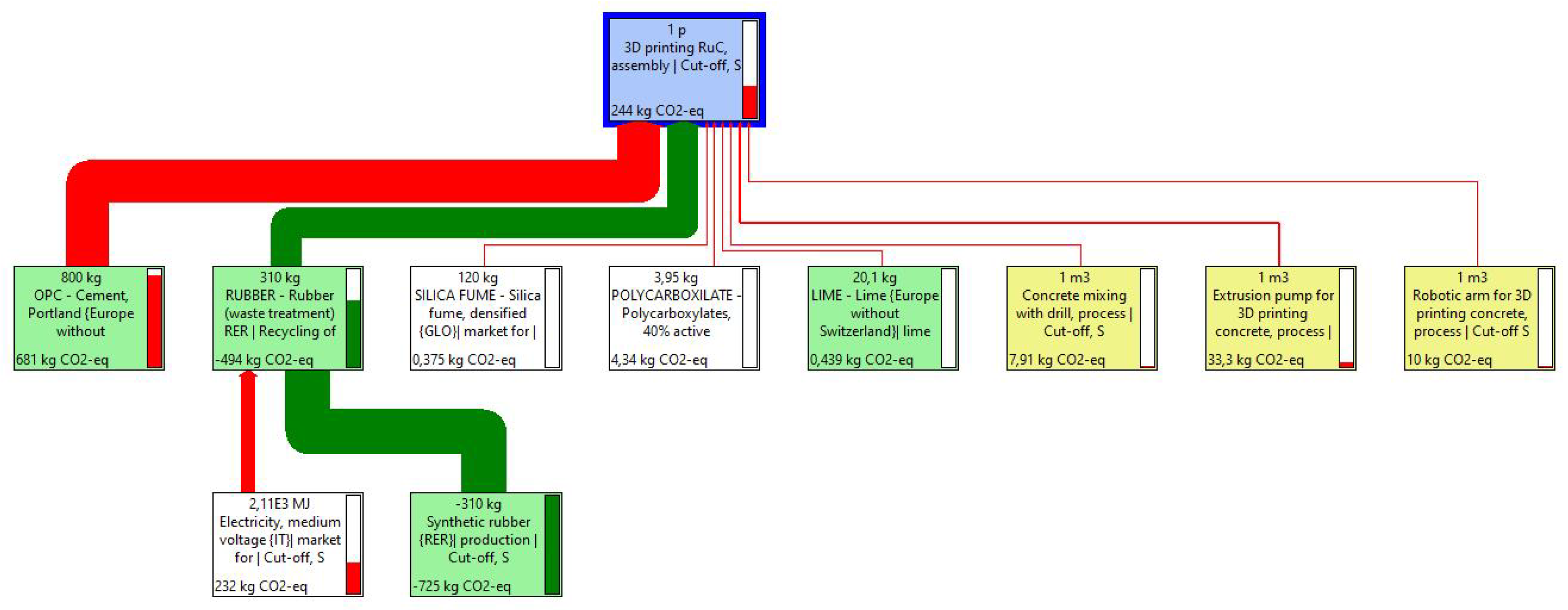

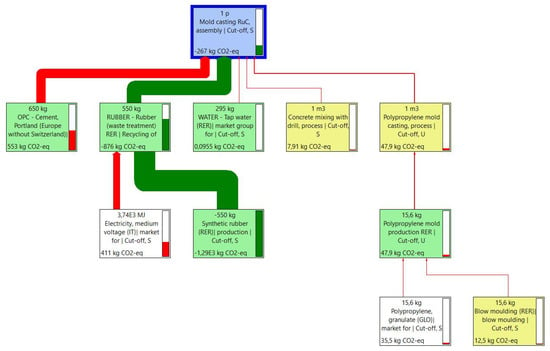

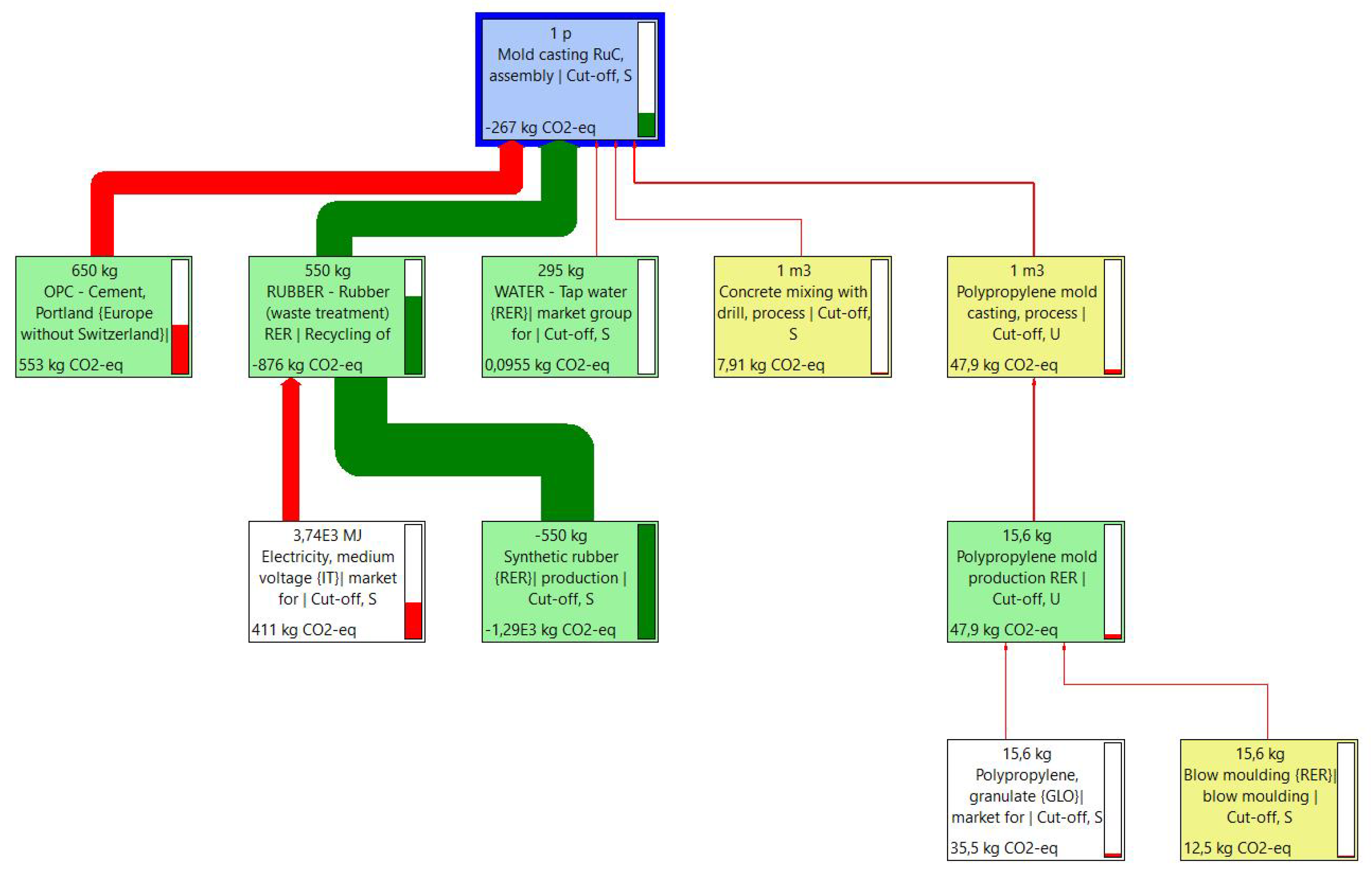

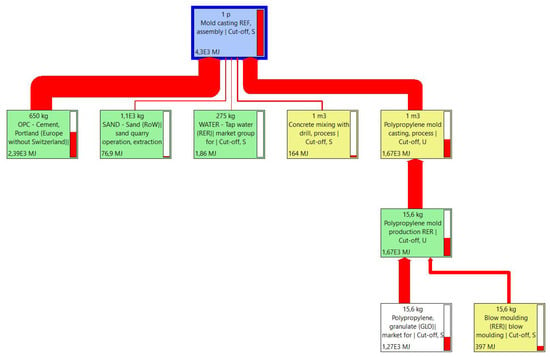

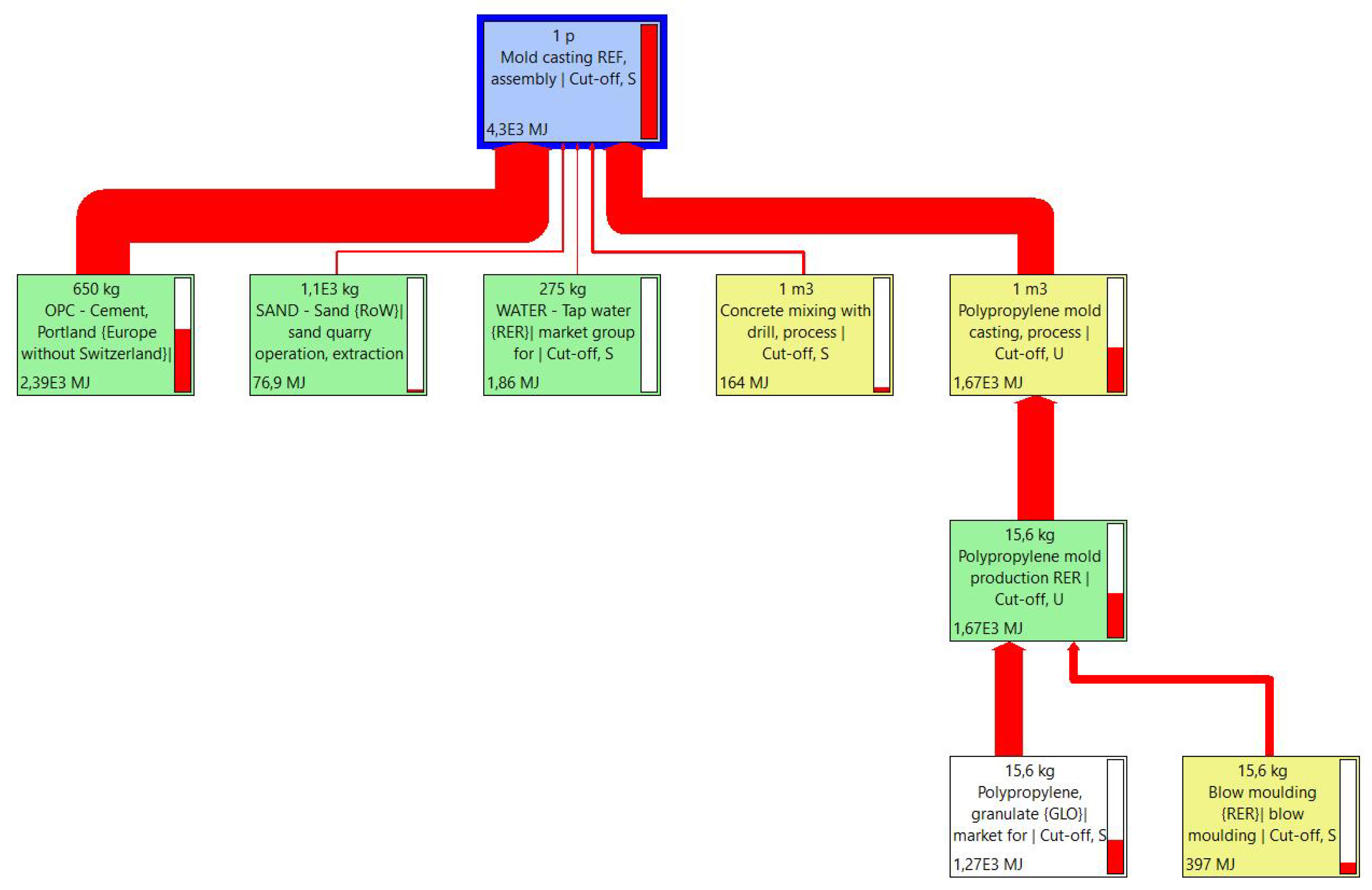

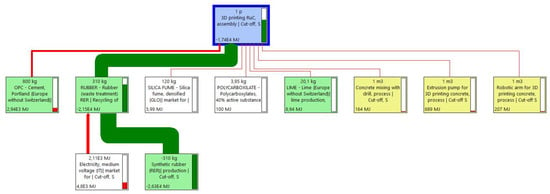

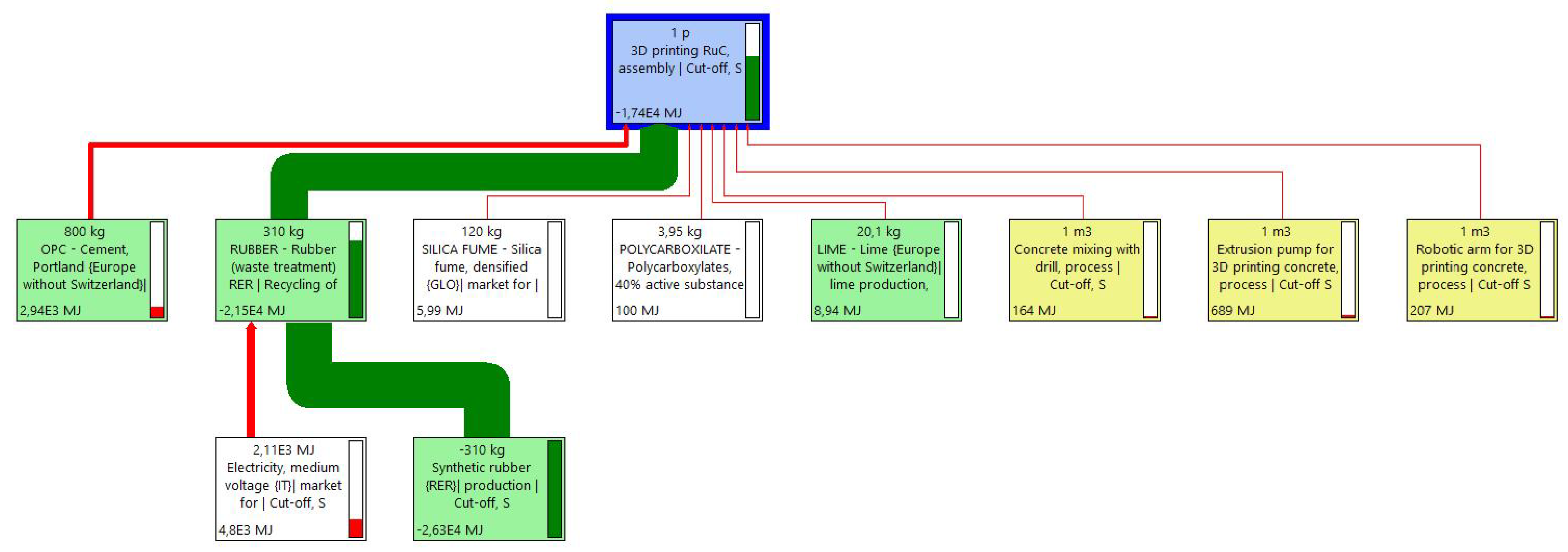

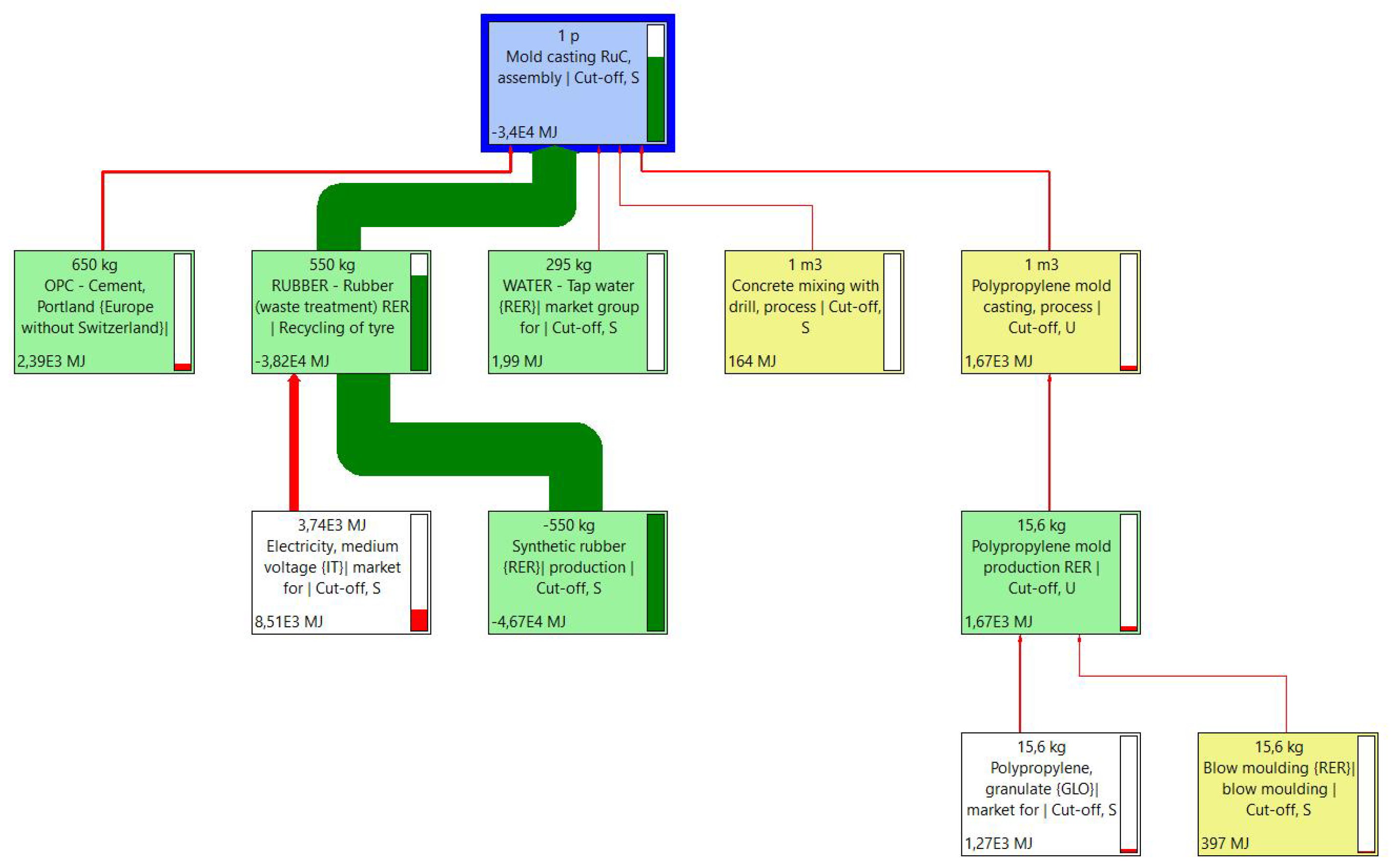

Replacing sand with GWTR remarkably changed the GWP scenario. Figure 3a,b show the carbon footprint impact of the rubberized concrete mixes obtained by 3D printing and mold-casting, respectively. SimaPro GWP networks are illustrated in Appendix A (Figure A3 and Figure A4, respectively) Recycling waste rubber as a concrete aggregate caused environmental benefits for both processes. Negative values of GWP, related to the implementation of GWTR in the mixes, indicated a credit for the environmental system (environmental benefit) [39], as the recovered tire materials replaced the virgin aggregates derived from a complete supply chain that is environmentally burdensome. As will be elucidated later, the overall “negative” impact value of GWTR stems from the net sum between the positive contribution of the waste tire grinding process and the negative contribution of obtaining the synthetic rubber. This means that the recovered material has more environmental benefits than the energy effort used for its processing (grinding). The GWTR contribution significantly lowered the total GWP values of the two processes under investigation proportionally to the number of rubber aggregates incorporated in the mix designs. Interestingly, the GWTR content in the c-RuC sample reduced the GWP index to a negative value. This result follows the same conceptual implications discussed above and finds agreement with the results of previous authors’ work [40].

Figure 3.

GWP results: (a) p-RuC and (b) c-RuC.

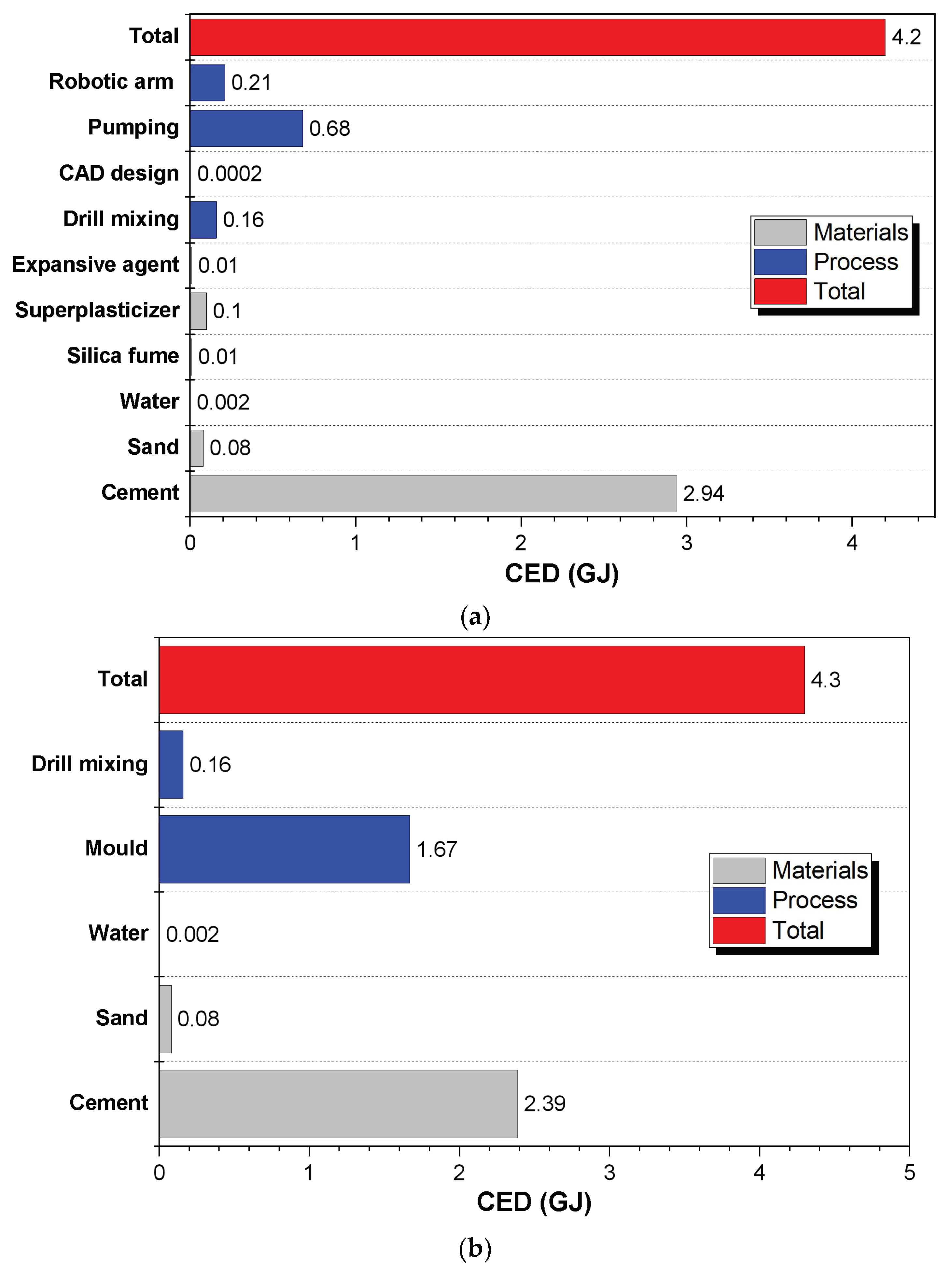

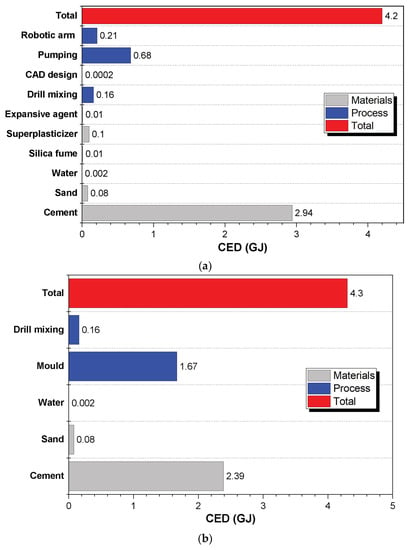

2.2.2. Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) Analysis

The CED values for the CTR mix processed via 3D printing and mold-casting methods are shown in Figure 4a,b, respectively. Figure A5 and Figure A6 in the Appendix A section display the relative LCA-CED networks of the two processes. Even in terms of energy demand, it was observed that the predominant contribution is given by cement, covering a total energetic requirement of 70% for the 3D-printed sample and 55% for the mold-casted one. In contrast to the GWP scenario above, there are no significant differences in CED between the two processes. Indeed, 3D printing appears slightly more advantageous in terms of energy consumption, especially regarding the “process” side. Regarding the net of drill mixing, the 3D printing line (CAD design + pumping + robotic arm) reduces the energy burden by about 46% compared to the production of the plastic mold required in the casting method. The result is supported again by Weng et al. [38], who proved that the manufacturing and adoption of formworks concerning the construction of precast units is quite an energy-intensive process, leading to a 10-fold increment in energy consumption with respect to the free-form manufacturing of 3D printing.

Figure 4.

CED results: (a) p-CTR and (b) c-CTR.

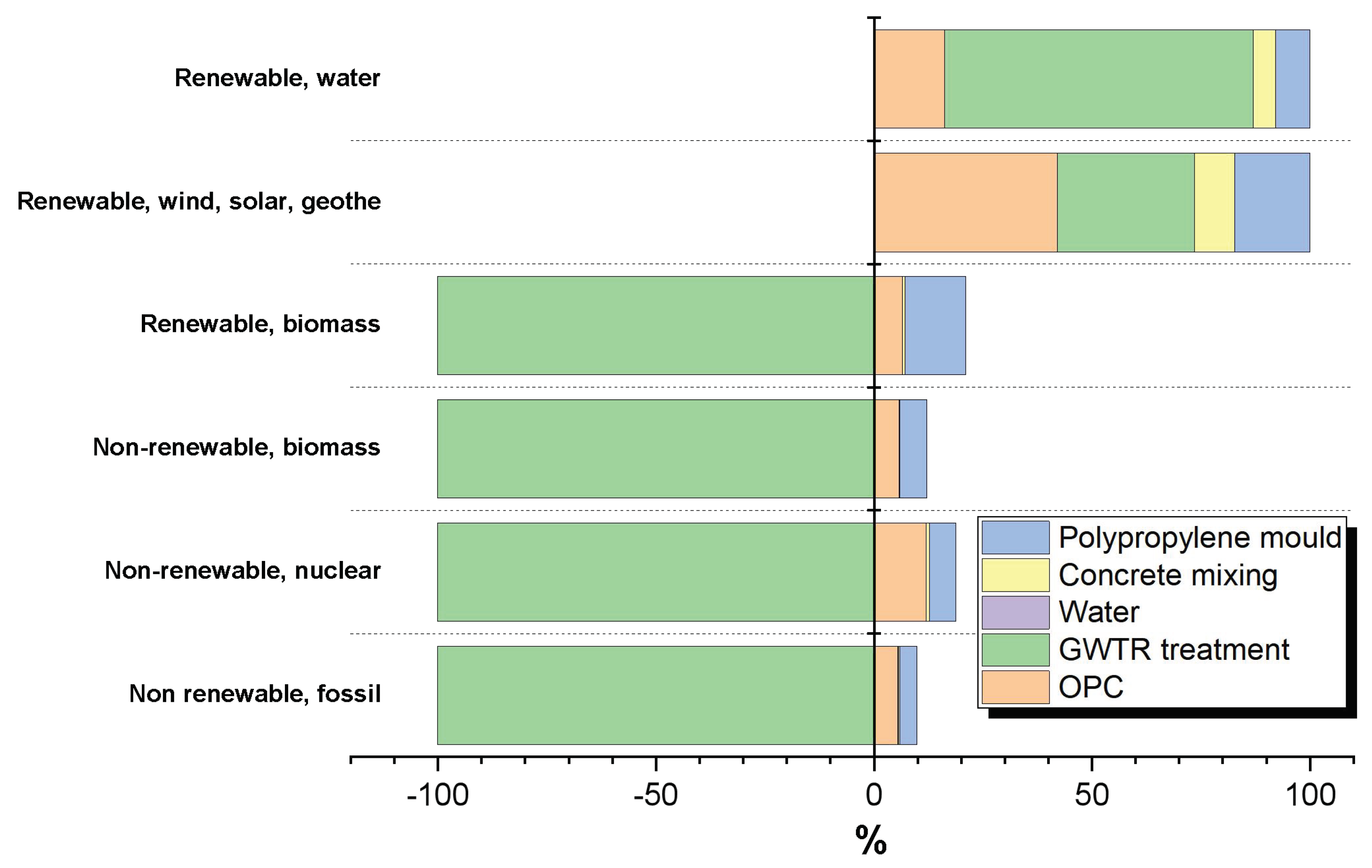

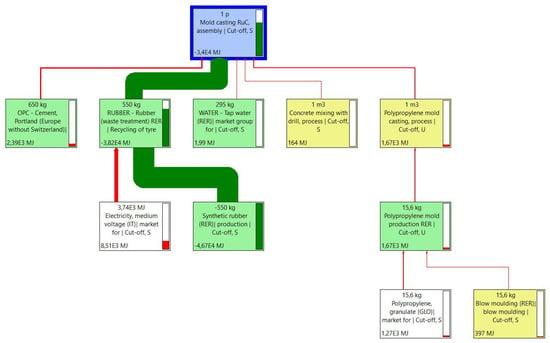

Using GWTR as an aggregate in place of sand also provided a significant benefit in terms of energy savings. The CED charts for p-RuC and c-RuC mixes are reported in Figure 5a,b, respectively. LCA-CED networks of the two processes are shown in Figure A7 and Figure A8 (Appendix A section). Regardless of the manufacturing process, the waste rubber addition lowered the total CED index to negative values. A negative value of this indicator means that the sequence of processes implemented to manufacture GWTR requires much less energy with respect to the energy requirements for the supply of the virgin resource (sand), implying potential advantages resulting from the emissions saved in the production of energy and primary raw materials that are displaced by those derived from waste [41]. The lowest (i.e., more energy-saving and benign) CED indicator was achieved by the c-RuC mixture (about twice as high as that of the 3D-printed mixture counterpart) as a result of the greater content of recycled aggregate incorporated into the mix design.

Figure 5.

CED results: (a) p-RuC and (b) c-RuC.

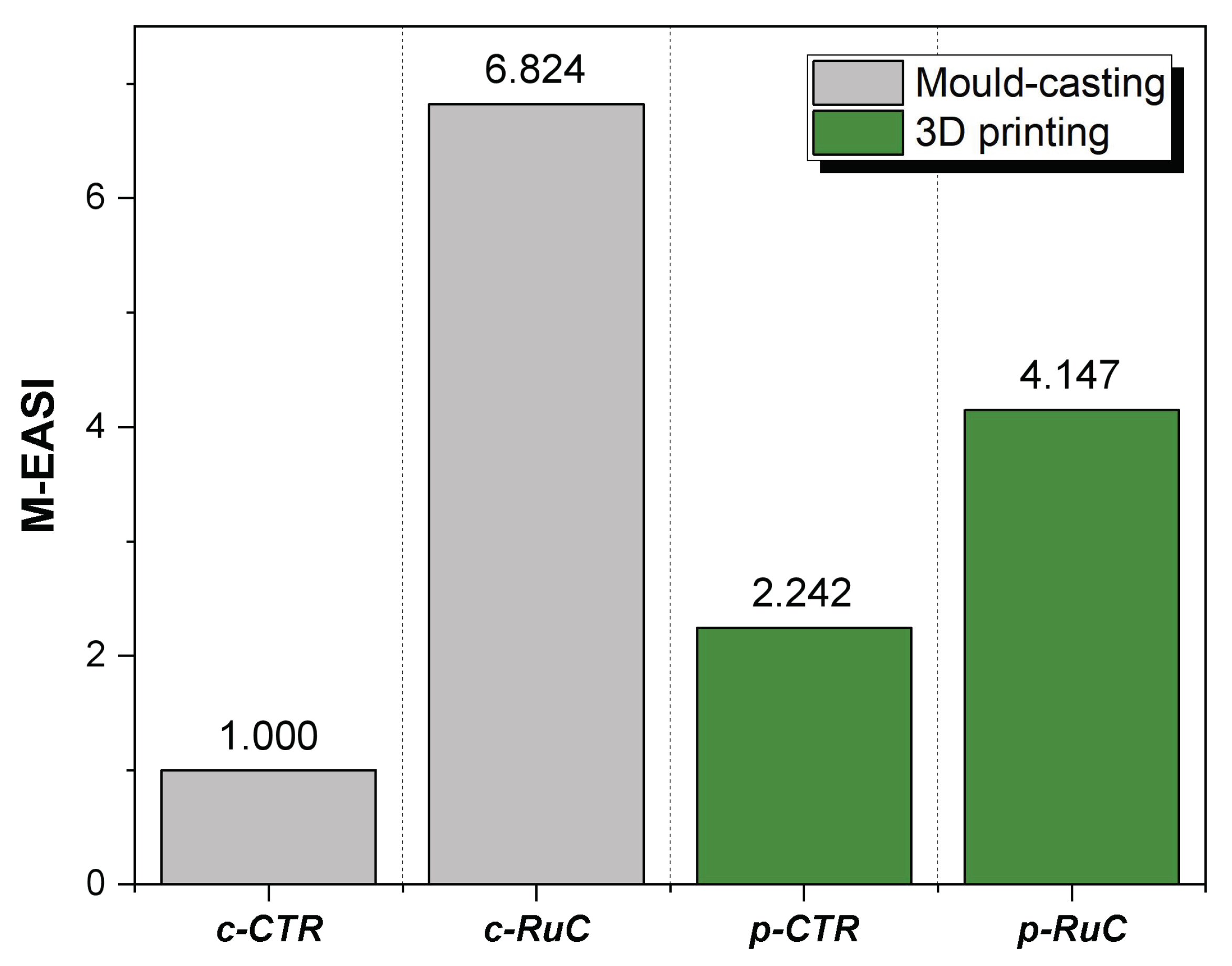

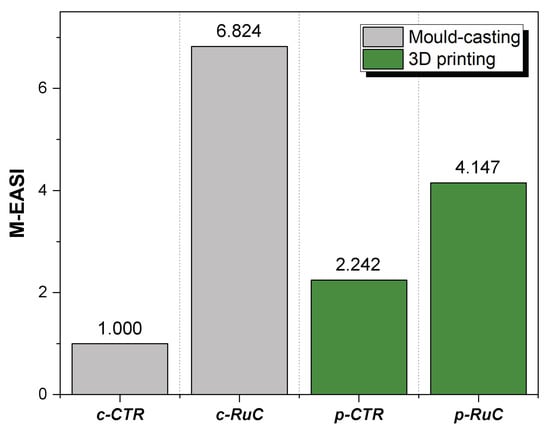

2.3. M-EASI Results

The M-EASI results are plotted in Figure 6. Compared to the c-CTR sample, taken as a “reference” in the analysis (M-EASI = 1), as it was considered “conventional” in terms of the mix design and production process, a significant increase in the M-EASI value was noted for all the other investigated samples. In accordance with the achieved results, the use of GWTR as an alternative concrete aggregate as well as the implementation of AM technology would represent environmentally and technologically advantageous approaches in construction, at least limited to the scope addressed in this work. The M-EASI proposed in the present research aimed to quantify the eco-sustainability and engineering properties of rubberized mixtures, favoring possible applications (non-structural) in which tire rubber aggregates can bring added values including being lightweight, heat insulation, and noise abatement. As claimed by Coffetti et al. [42], the M-EASI, by combining both the sustainability and engineering performance of concrete materials, would support stakeholders in the construction sector in selecting more eco-friendly building materials, improving the education of designers, researchers, and contractors to share the acquired knowledge about the latest technologies in concrete and their good practice in processing.

Figure 6.

M-EASI analysis results.

Some noteworthy conclusions can be drawn from the M-EASI data. The c-RuC sample is the best among those investigated. Although this mixture was characterized by the worst mechanical performance, it considerably gains in terms of thermo-acoustic insulation capability and eco-functionality (reduced GWP and CED) resulting from the higher amount of GWTR it incorporates. On the other hand, the printed counterpart (i.e., p-RuC mix) provided higher mechanical strength and durability properties, which are potentially scalable for practical applications in construction (lightweight structural concrete class) but lower the M-EASI value. From the previously discussed LCA results, it was ascertained that the main criticality of the 3D-printable mixtures concerns the higher content of the binder (Portland cement) and the unviability of integrating high rates of recycled rubber aggregates to meet suitable printability characteristics. Mathematically, there is an exponential relationship between the proposed M-EASI and the environmental indicators (GWP and CED), which then provide a more significant contribution to the overall performance of the material. Although AM offers design flexibility benefits, resource saving, and greater eco-friendliness on the “process” side than the mold-casting method, many efforts will be needed on the “material” side to smooth out the M-EASI gap with the traditional mixtures. In this sense, the implementation of alternative low-carbon binders (alkali-activated materials, geopolymers, limestone cements, earth-based materials) or the partial replacement of cement by pozzolanic fillers (fly ash, nano-silica, calcined clay, rice ash husk) appear to be promising strategies for obtaining more eco-sustainable concretes with adequate rheological properties for printing [7].

3. Materials, Methodology, and Setup of the Study

3.1. Materials

First, the objective of the study was to evaluate the interplay and sensitivity of LCA for two mix designs tailored for 3D printing and mold-casting manufacturing processes. In each type of mix design (printed and mold-casted), the influence of GWTR as a total concrete aggregate will be investigated and compared with the ordinary mortar formulations incorporating sand as an aggregate.

3.1.1. 3D Printing

The 3D-printable concrete formulations, examined by LCA, were designed and extensively characterized by the authors in previous research works [18,19,20]. Two types of mix designs were examined:

- Printable control mixture (p-CTR) incorporating fine mineral aggregates (sand) in the mix design

- Printable rubberized mixture (p-RuC) incorporating GWTR in two different particle size gradations, i.e., 0–1 mm rubber powder (fine fraction) and 1–3 mm rubber granules (coarse fraction), as a total replacement (100% v/v) of sand. The polymer aggregate blend included an equal proportion of fine and coarse fractions (50% v/v–50% v/v). This type of mix design was selected in the present investigation, as, from the results of the studies above, it was the “best” in terms of mechanical performance.

Table 2 details the mix compositions of the printable formulations under examination.

Table 2.

Mix proportions of printable formulations: p-CTR and p-RuC.

In addition to the conventional ingredients commonly used in traditional cementitious mixes, the printable mix designs featured a well-tailored blend of chemical admixtures, including superplasticizers, expansive agents, and pozzolanic fillers (silica fume), to control and improve the rheology, printability, and buildability of the fresh-state mixtures [43]. The mix designs of printable mixtures were set because of an optimization experimentation in which the fresh requirements of concrete samples (extrudability and buildability) were assessed [18,19]. The optimum mix was considered the one with the lowest content of water and a suitable proportion between GWTR and cement, achieving the “target” printability properties.

3.1.2. Mold-Casting

For comparison purposes, LCA analysis was performed on control and rubberized concrete samples obtained by the traditional mold-casting method, labeled as c-CTR and c-RuC, respectively. The mold-casted mixes included the same type of binder (Portland cement), mineral fraction (fine sand), and rubber aggregates used in designing the 3D-printed mortars. However, as highlighted in Table 3, the mix constituent proportion is significantly different. The mold-casted cementitious formulations were implemented by the authors in previous research where lightweight rubber-concrete hollow bricks were investigated [24].

Table 3.

Mix proportions of mold-casted formulations: c-CTR and c-RuC.

With regard to the mix proportion of the mold-casted mixtures, it was started with the preparation of the c-CTR mix, using a w/c of 0.42, which is technically considered as the optimal value for ordinary concrete mix, ensuring the complete and proper hydration of the cementitious system. By replacing the sand with GWTR, the water content was slightly increased to make up for the loss of workability following the effect of the polymer aggregate, ensuring suitable rheological conditions for casting. The w/c of the mold-casted concrete mixes was higher than that of the printable mixtures due to the higher dosage of the binder used in 3D printing processing. However, concerning the p-RuC mix, the implementation of chemical admixtures resulted in the use of less water without compromising the workability and printability of the mixture. Indeed, low water–cement ratios are desired requirements for obtaining the optimal buildability requirements of the printing mixtures.

3.2. Manufacturing Processes

To include in the LCA study the influence of manufacturing processes in terms of carbon footprint and embodied energy, in this section, 3D printing and mold-casting workflows, implemented to process the investigated control (p-CTR and c-CTR), and rubberized (p-RuC and c-RuC) mixes were compared. Energy requirements and emissions were evaluated considering the processing stages for each manufacturing method leading to 1 m3 of the concrete product (functional unit).

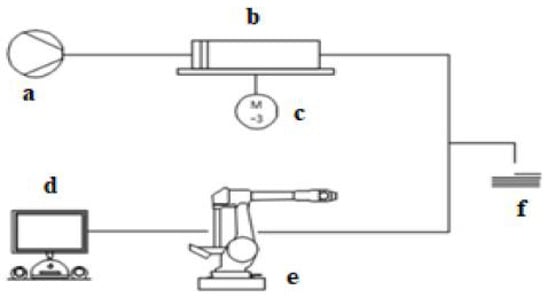

3.2.1. 3D Printing

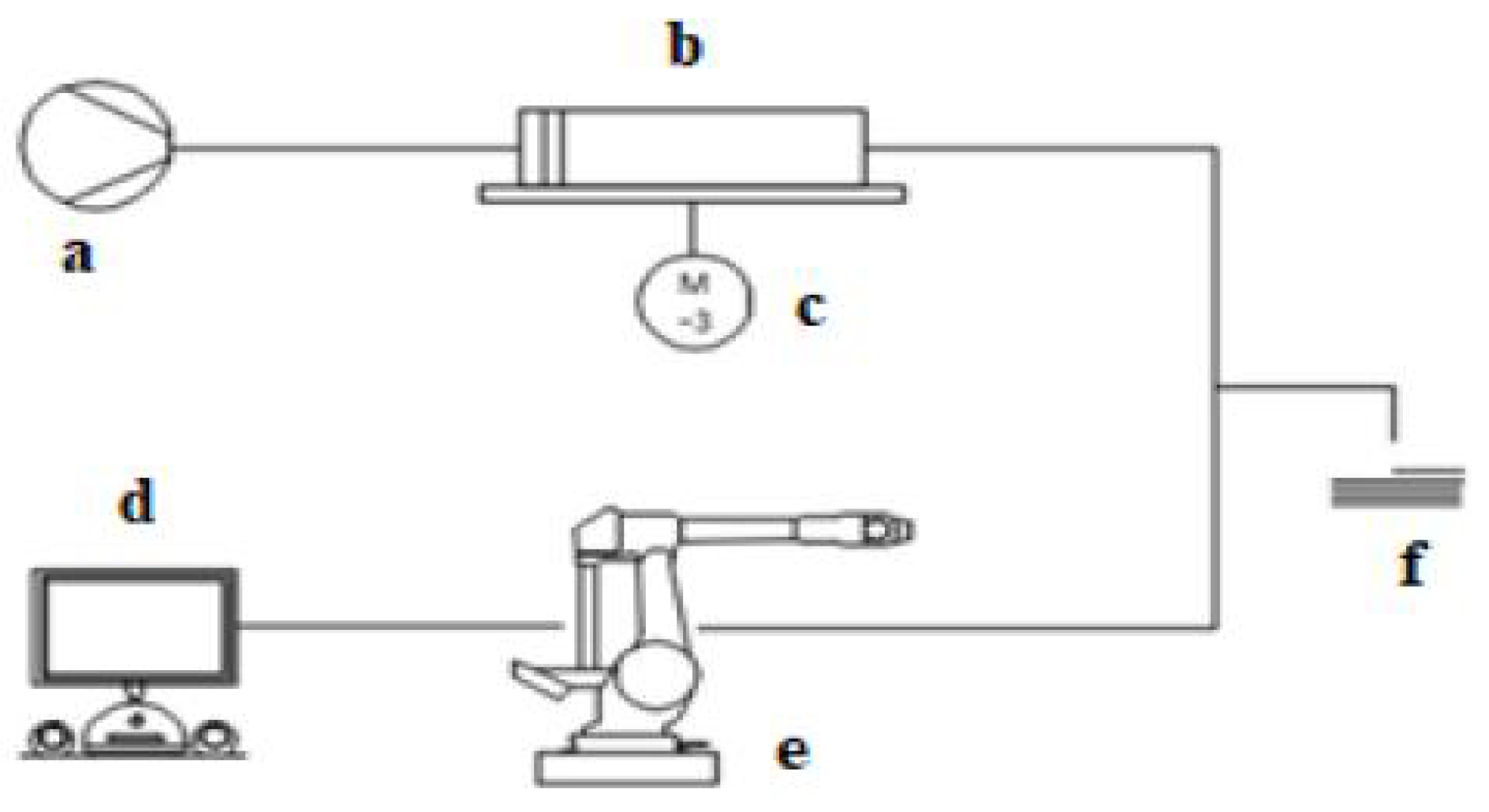

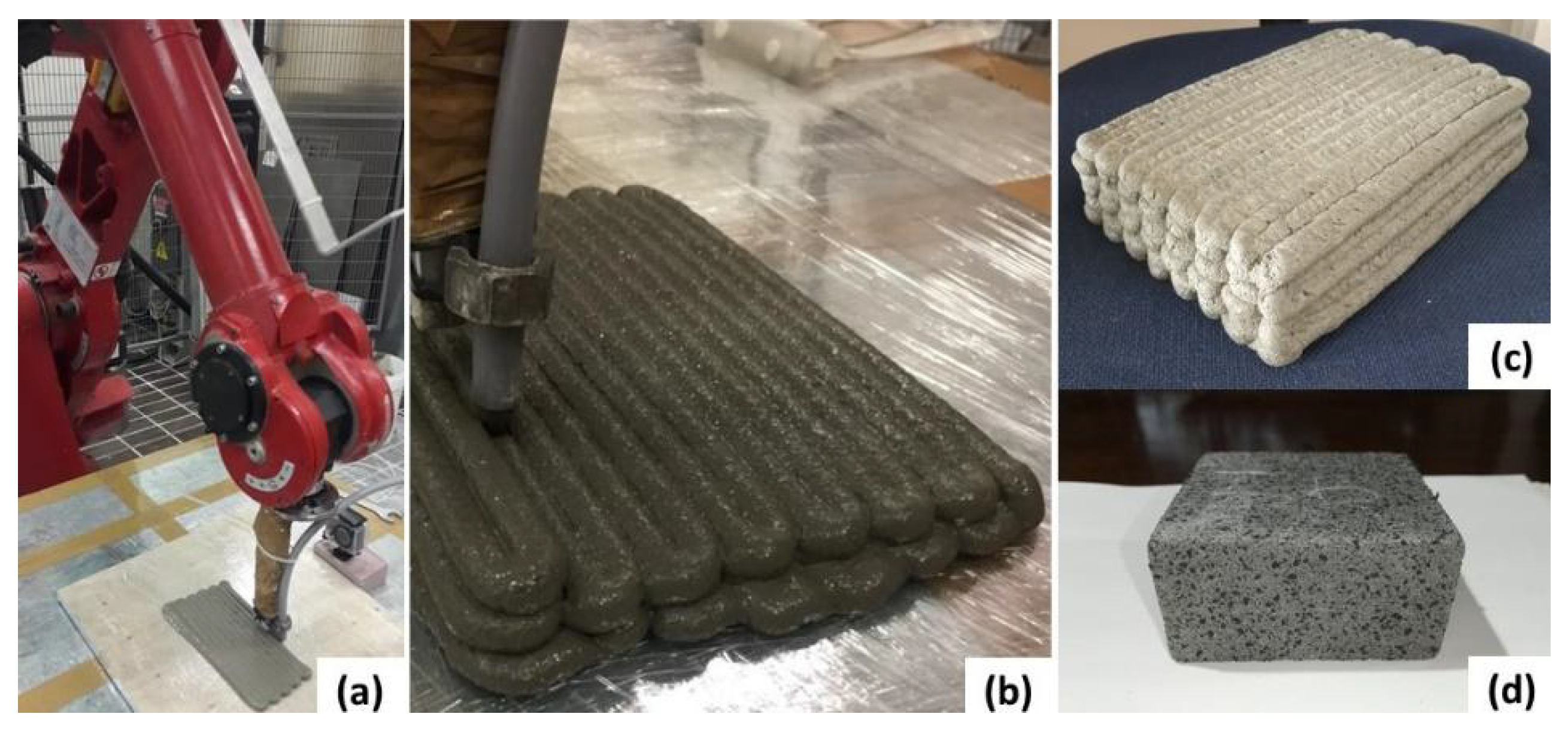

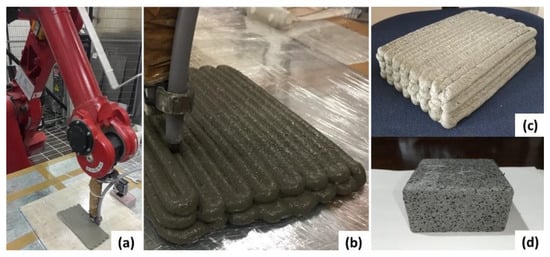

An extrusion-based 3D printing system was designed and utilized to print the p-CTR and p-RuC mixtures. The extrusion system involved a three-axis robotic arm (Comau, Turin, Italy) equipped with a PVC circular hose (Ø = 10 mm) acting as an extrusion nozzle. The hose was connected to a cylindrical Aluminum tank (mixing unit), which was able to contain 3 L of the fresh mix. The tank was connected to a four-bar compressor which pressurized the mixing unit, pushing the concrete mix towards the extrusion hose by a Nylon piston. In addition, the mixing unit was placed on the vibrating plate to preserve the adequate workability of the mix during the whole printing process. The controls relating to robotic arm motion (printing path) and the setting of the printing parameters (printing speed, infill, layer thickness) were monitored by a control software unit based on Cura software (Ultimaker, Utrecht, the Netherlands). A schematic of the 3D printing system [44] is illustrated in Figure 7:

Figure 7.

Schematic of the printing system: (a) compressor, (b) mixing unit, (c) vibrating plate, (d) software control unit, (e) robotic arm + extrusion hose, (f) printing platform (reprinted with permission from [44]).

Before printing, the preparation of the fresh mix involved three steps: (a) the hand mixing of dry constituents for 45 s, (b) the addition of water, and (c) the mixing of fresh paste for 12 min by an electronic driller. Then, the fresh concrete was manually added to the mixing unit. Starting from the 3D-CAD file of the object to be printed, the Cura software enabled the kinematics of the robotic arm, extruding the printable mix by a layer-by-layer deposition until the completion of the final structure. One 3D-printing cycle involved the manufacturing of a six-layer slab (225 mm 150 mm 60 mm) following an optimized print speed of 33 mm/s. This geometry was a reasonable choice for assessing the printability requirements of the concrete mixture (extrudability and buildability) following well-established criteria in 3DCP technology [18,19], as well as for having a printed sample of adequate dimensions to extract specimens for the physical-mechanical characterization of the hard-state material. Some stages of the printing process are displayed in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Phases of the 3D-printing manufacturing process: (a) robotic arm operation, (b) layer-by-layer deposition of the cementitious mix, (c) hard-state printed slab, and (d) internal structure of the p-RuC sample.

It is worth considering that the slab production did not require the use of molds or formworks, enhancing the free-form fabrication characteristic of the 3DCP approach [45]. After 28 days of ambient curing (20 °C), the slabs were cut with a diamond saw to extract specimens intended for the material’s characterization.

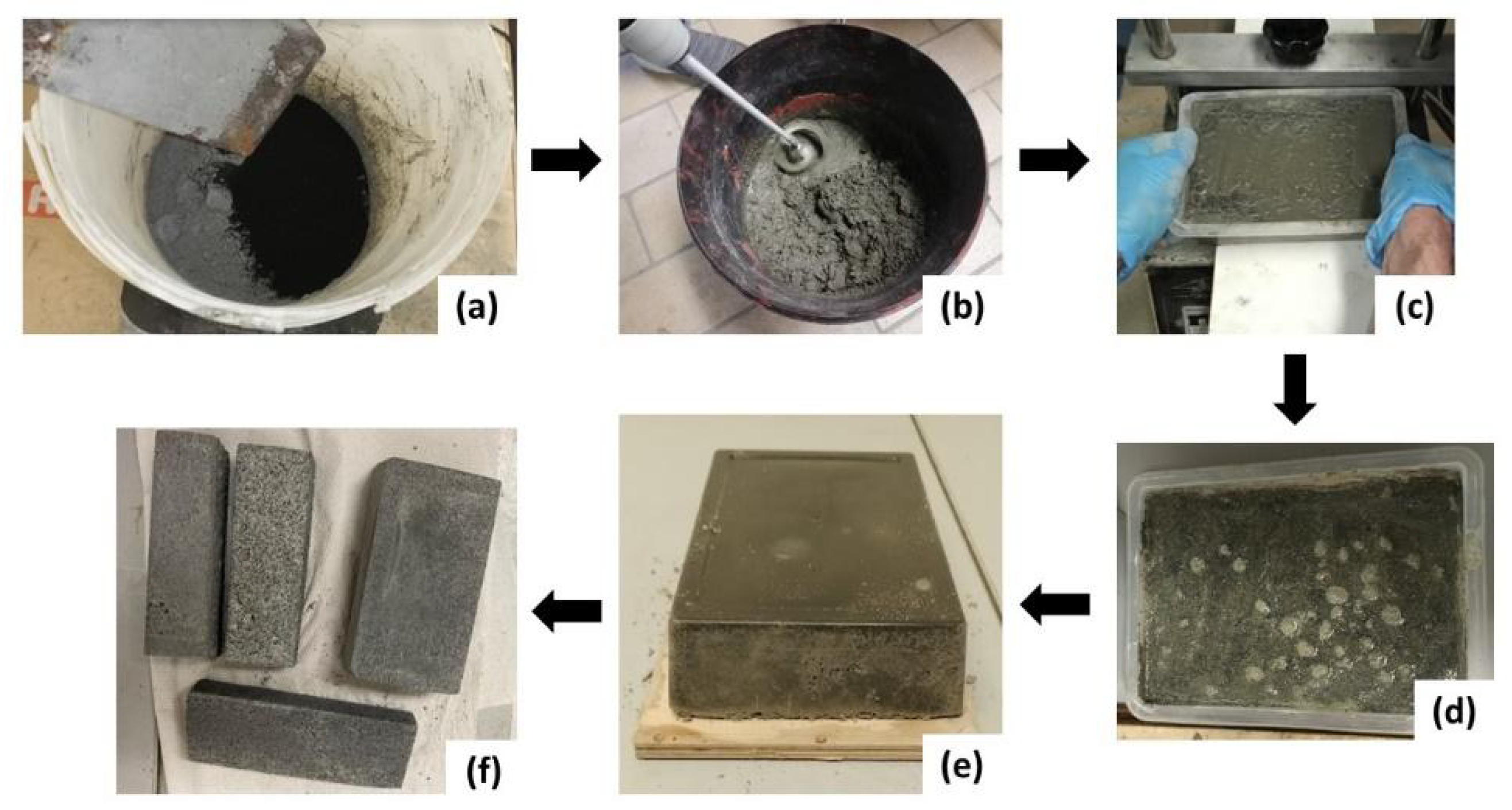

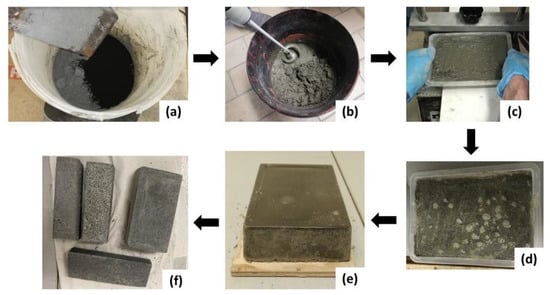

3.2.2. Mold-Casting

Mold-casting manufacturing, implemented for c-CTR and c-RuC mixes, turned out to be less sophisticated than digital additive fabrication. The process flow is illustrated in Figure 9. As for the 3D-printing process, the fresh mix preparation involved the hand mixing of dry constituents for 45 s (Figure 9a) and the drill mixing of the fresh paste (12 min) after the addition of water (Figure 9b). Then, the cementitious paste was cast in a polypropylene (PP) mold with dimensions comparable with those of the 3D-printed slab, and it was subjected to vibrating cycles on a vibrating plate (Figure 9c) to expel the air bubbles embedded during the mixing and casting phases. The curing was conducted in ambient conditions at 20 °C for 28 days (Figure 9d). Then, the hardened slab was de-molded (Figure 9e), and, by diamond saw cutting, specimens for the material’s characterization were produced (Figure 9f).

Figure 9.

Phases of the mold-casting manufacturing process: (a) dry constituents mixing, (b) drill mixing of the fresh paste, (c) pouring in the polypropylene mold and vibrating cycles, (d) curing, (e) de-molding of the hard-state slab, and (f) cutting of the specimens for the material’s characterization.

Although the fresh mix preparation, the vibrating stages, and the curing can be considered equivalent to the 3D printing process, mold-casting required the use of a mold for the manufacturing of the final concrete product (slab). This will inevitably be considered in the assessment of the global energy and environmental impact of the process.

3.3. Performance Characterization of Materials

To evaluate the influence of the mix designs and manufacturing processes on the engineering properties of rubberized concrete samples (and their respective CTR counterparts), a comprehensive physical-mechanical characterization was conducted. Specifically, four types of performance indicators were experimentally assessed and included in the EASI computation to consider the engineering performances of the designed cementitious mixes as well as their environmental impact. The performance indicators are listed below:

- Mechanical strength indicator. Compressive strength (Rc) is recognized as the major indicator of concrete quality. It provides a performance index useful for classifying concrete in agreement with its mechanical strength class and therefore the application field [46]. The ASTM C109/C109M-20a test method [47] was used to examine the Rc differences between printed and mold-casted concrete samples. In the case of 3D-printed samples, where the compressive strength performance was determined as a function of the printing direction for anisotropy reasons [18,19], an average value of Rc obtained in the two directions will be considered to have a unique value for the comparison with the casted samples.

- Durability indicator. The permeable porosity (Φ) was selected as a durability indicator of the investigated mixes, reflecting the resistance of the concrete against the permeation of deteriorating chemical-physical agents [48]. Experimentally, Φ was assessed by the vacuum saturation method, following the ASTM C1202 standard method [49].

- Energy-efficiency indicators. Th energy efficiency of buildings is one of the basic requirements of current architectural engineering. To minimize energy consumption and improve occupant comfort, thermal and acoustic insulation are considered key requirements for the construction materials selected in the building design [50]. Lightweight rubber-concrete mixes may be good candidates for thermal insulation and noise reduction applications due to the low heat conductivity and enhanced damping properties provided by the tire rubber aggregates [51]. In this work, thermal conductivity (k) and the sound reduction index (SRI) were used as energy-efficiency indicators to evaluate the thermo-acoustic performance of CTR and RuC samples, respectively. The ASTM D7984 test method [52] was employed to analyze the k-values of the specimens. SRI was determined by impedance tube measurements, following the experimental procedure described in Refs. [19,25].

3.4. Modified Empathetic Added Sustainability Index (M-EASI)

The technological aspects described above make it possible to compare the four types of cement considered in this work: c-CTR, c-RuC, p-CTR, and p-RuC. The approach used for this analysis is holistic, that is, the performance of the materials, their durability, and the environmental impact relating to the respective production processes were considered simultaneously. These properties are elegantly related to each other in the M-EASI indicator proposed by Coffetti et al. [42], whose mathematical form is shown below (Equation (1)):

where Gross Energy Requirement (GER), Global Warming Potential (GWP), and Natural Raw Materials Consumption (NRMC) are considered indicators of environmental impact. All parameters are normalized to a reference cement, which, in this case, is the c-CTR (M-EASI = 1); therefore, M-EASI values greater than 1 correspond to greater sustainability with respect to the reference taken.

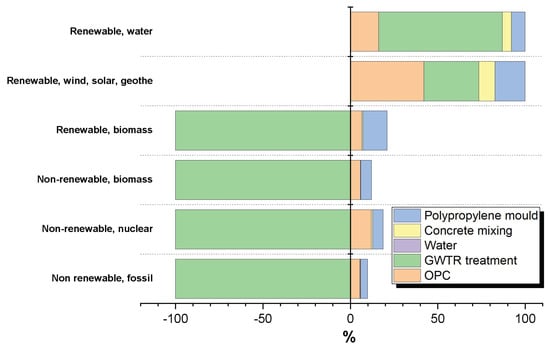

In this work, the performances in terms of Rc, SRI, and thermal resistance, defined as the inverse of k, were considered. The durability indicator was defined as the inverse of Φ, which expresses the cement’s resistance to permeation and, therefore, the possibility of its deterioration over time. The environmental parameters were obtained quantitatively with the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology in accordance with the UNI EN ISO 14040 standard [53], which, by the most recent methods, provides the possibility of calculating, for each product and process, the GWP value (expressed in kg CO2-eq) with the IPCC 2021 GWP100 method and the value of the Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) with the homonymous method, which represents the gross energy contribution necessary for the entire production process. The indicator that expresses the use of natural resources, corresponding to the NRMC, was not calculated. As shown in Figure 10, the total CED value is determined by energy contributions that already consider the renewable and non-renewable resources involved in the examined processes.

Figure 10.

Graph of the CED contributions referred to in the production process of the c-RuC mix. The histograms refer to the contributions of non-renewable (fossil, nuclear, and biomass) and renewable (biomass, wind, solar, geothermal, and water) energy resources.

The calculations of the environmental indicator values were carried out using the SimaPro software (PRé Sustainability, Utrecht, The Netherlands), which includes the Ecoinvent 3.9 database, containing the processes and methods necessary for the analysis. For this analysis, the M-EASI indicator has therefore been adapted as follows (Equation (2)):

where the coefficient has been reduced from 3 to 2 due to the absence of an exponential contribution to the denominator. In the M-EASI proposed here, the performance indicators take into account, in addition to the mechanical strength property, the thermo-insulating peculiarities (heat resistivity and SRI) of materials, considering the potential of the rubberized mixtures for civil and architectural applications where heat and noise insulation efficiencies are primarily required.

3.4.1. Goals and Scope of the LCA

The goal of the analysis carried out on the four types of concrete samples described is the comparison in terms of sustainability. A cradle-to-gate approach was used for the evaluation of the environmental parameters, i.e., the steps of the production process of the materials were considered, starting from the procurement of raw materials, their transformation into the constituent components of the cement mixture, and the processes for their assembly and implementation. Since this was a comparison, the vibration processes of the fresh mixture and the curing, which are equivalent for all four types of cement considered, were neglected. In the case of the two mold-casted cementitious mixes, the processes considered are: (1) the mixing by a drill mixer and (2) the implementation of a PP mold usable for a single casting operation. In the case of 3D printing, following the mixing of the components, the CAD design process through software was considered using a desktop computer with a liquid crystal display (LCD). After this, the pumping operation for the extrusion of the mixture and the use of an automated robotic arm that deals with the deposition of the extruded material according to the geometric specifications defined in the design phase were considered. The functional unit to which the comparison refers is 1 m3 of the final product. The analysis was carried out by the LCA methodology, neglecting the temporal variable and regarding processes that, on average, describe the current technological level in Europe. In the case of the two mixtures in which GWTR was used to replace sand as an aggregate, a cut-off type allocation was considered, whereby the environmental impacts of recycling a given material are attributed to the purchaser of waste that processes it. However, this life-cycle phase is also attributed to the environmental advantages derived from the recovery of semi-finished material, which can be reinserted into a new life cycle as an input material from the techno-sphere.

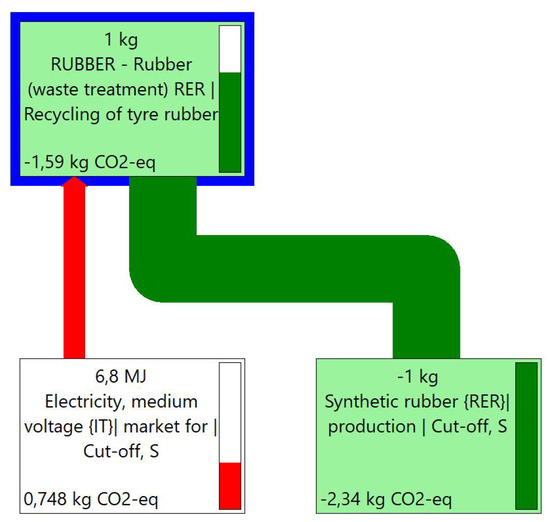

3.4.2. Life Cycle Inventory

To define the life cycle inventory, the most representative processes included in the Ecoinvent 9.3 database were used, containing aggregated and averaged data with a European geographical allocation. The components of the cementitious mixes (Portland cement, tap water, sand, silica fume, polycarboxylate ether-based superplasticizer, and calcium oxide-based expansive agents) are represented by a process already included in the database. For GWTR, an ad hoc process was built, which involves the use of an amount of electrical energy for grinding equal to 6.8 MJ/kg [54] and the generation of 1 kg of synthetic rubber as an avoided product. The latest is defined as a “recovery” in terms of material balance and, correspondingly, also as an environmental benefit guaranteed by the negative sign of the mass value and the environmental impact indicators. Figure 11 illustrates the LCA network referred to in the production of 1 kg of GWTR, extrapolated by SimaPro software.

Figure 11.

SimaPro network of the recycling process of 1 kg of waste tire rubber. The contribution in terms of GWP is expressed at the bottom of each sub-process.

The stages of the assembly and implementation of the components required the modeling of the processes included in the analysis. For the mixing process, the use of an electric drill with a nominal power equal to 1200 W (PD), which takes 10 min (tM) for a mixture volume of 10 L, was considered. Then, the energy required for the drill-mixing operation (EM) is (Equation (3)):

which, scaled to the reference flow of 1 m3 of the mixture, is equivalent to 20 kWh. The mold-casting operation was modeled considering the production of a 31.5 g PP mold in which 2024 cm3 of a cementitious compound was poured, referred proportionally to the production of 1 m3 of concrete. The CAD design process was represented by using, for 10 min, an office desktop with an LCD screen. This process is included in SimaPro’s Ecoinvent 9.3 database.

The modeling of the AM processes related to the extrusion of the mixture and the use of the robotic arm requires knowledge of the usage time of the two respective machines (the compressor and robotic arm). Considering the dimensions of the 3D-printed slab (225 mm 150 mm 60 mm), a printing speed of 33 mm/s, and a nozzle diameter equal to 10 mm, the printing time (tP) is equal to (Equation (4)):

The robotic arm prints 15 filaments of 225 mm for 6 layers, neglecting the changes in direction.

The calculation for the pumping system energy requirement (EP) to extrude a slab sample using a compressor with a nominal power (PP) of 1 kW is (Equation (5)):

corresponding to 84.2 kWh per m3 of the extruded mixture.

Similarly, to model the robotic arm processing, it was considered that, for horizontal trajectories, ignoring the changes in direction, the nominal power supplied by the motor is 300 W (PRA) [55]. For a single sample, the energy expended by the robotic arm (ERA) is (Equation (6)):

which, referring to 1 m3, is 25.3 kWh.

In all the processes described above, an energy supply in the form of low- and medium-voltage electricity supplied by the Italian electricity grid was considered. Table 4 shows the inventory of processes created in SimaPro and modeled according to the hypotheses previously described.

Table 4.

Inventory of the processes defined in this work and not present in the SimaPro database.

4. Conclusions

The utilization of GWTR as aggregates in printable materials for 3D concrete printing demonstrates attractive potential in designing lightweight, eco-sustainable, and thermo-acoustic effective concrete structures. This approach takes the benefit of both the characteristics of the rubberized concrete as well as the technological and environmental peculiarities of additive manufacturing processing. The present research addressed the engineering performance and environmental impact tradeoff between rubber-concrete mixtures via 3D printing and using the conventional mold-casting method. In addition to the materials’ performance, including mechanical strength, porosity, and thermo-acoustic insulation, the related eco-sustainability indicators (GWP and CED) were assessed by LCA methodology, considering the impact of both the mix design and the manufacturing process. The results revealed that, regardless of the type of manufacturing technology, replacing sand with GWTR significantly lowered the overall environmental impact because of the avoided energy/emissions related to the supply chain for virgin aggregates. From the “process” standpoint, 3D printing turned out to be more energy-effective than the mold-casting method. Additive fabrication would seem to be the most viable channel for achieving rubberized concretes with adequate structural performances, as demonstrated by the best properties in terms of mechanical strength and resistance to permeability. On the “material” side, the use of a larger quantity of the cement binder makes the printable mixtures more impactful in terms of carbon footprint. As also demonstrated by the M-EASI indicator, considering both the environmental and engineering performance of the samples, the way to reduce the eco-footprint gap of the printable mixtures is to focus the research efforts on the binding material. Future investigations will be projected to a combined assessment of environmental impact and performance considering greener cementitious matrices compared to traditional Portland ones. Preliminary studies conducted by authors on alkali-activated cements incorporating waste rubber [56] have shown interesting results, which are worthy of further research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and M.V.; methodology, M.S. and I.B.; software, I.B.; validation, M.S., I.B. and M.V.; formal analysis, M.S. and I.B.; investigation, M.S. and I.B.; resources, M.V.; data curation, M.S. and I.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and I.B.; writing—review and editing, M.S., I.B. and M.V.; supervision, M.V.; project administration, M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, M.S.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ettore Musacchi (ETRA) for supplying the rubber aggregates used in this study. The authors recognize Valeria Corinaldesi and Gluaco Merlonetti (Marche Polytechnic University) for the technical support in the 3D-printing processing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

SimaPro GWP network for p-CTR mix processing.

Figure A1.

SimaPro GWP network for p-CTR mix processing.

Figure A2.

SimaPro GWP network for c-CTR mix processing.

Figure A2.

SimaPro GWP network for c-CTR mix processing.

Figure A3.

SimaPro GWP network for p-RuC mix processing.

Figure A3.

SimaPro GWP network for p-RuC mix processing.

Figure A4.

SimaPro GWP network for c-RuC mix processing.

Figure A4.

SimaPro GWP network for c-RuC mix processing.

Figure A5.

SimaPro CED network for p-CTR mix processing.

Figure A5.

SimaPro CED network for p-CTR mix processing.

Figure A6.

SimaPro CED network for c-CTR mix processing.

Figure A6.

SimaPro CED network for c-CTR mix processing.

Figure A7.

SimaPro CED network for p-RuC mix processing.

Figure A7.

SimaPro CED network for p-RuC mix processing.

Figure A8.

SimaPro CED network for c-RuC mix processing.

Figure A8.

SimaPro CED network for c-RuC mix processing.

References

- Du Plessis, A.; Babafemi, A.J.; Paul, S.C.; Panda, B.; Tran, J.P.; Broeckhoven, C. Biomimicry for 3D concrete printing: A review and perspective. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Kaszyńska, M.; Skibicki, S.; Hoffmann, M. 3D Concrete Printing for Sustainable Construction. Energies 2020, 13, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chung, J.K.H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y. The cost calculation method of construction 3D printing aligned with internet of things. J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, S.; Basavaraj, A.S.; Rahul, A.V.; Santhanam, M.; Gettu, R.; Panda, B.; Mechtcherine, V. Sustainable materials for 3D concrete printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Sibai, A.; Sambucci, M. Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing of Concrete Products: Revolutionizing and Remodeling the Construction Industry. J. Compos. Sci. 2019, 3, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, M.P.; de Mendonça, É.M.; Fernandez, L.I.C.; Caldas, L.R.; Reales, O.A.M.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and environmental sustainability of cementitious materials for 3D concrete printing: A systematic literature review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Abdelgader, H.S.; Onaizi, A.M.; Fediuk, R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Rashid, R.S.; Murali, G. 3D-printable alkali-activated concretes for building applications: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Guo, X.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, P.; Lu, L.; Cheng, X. Effect of Tartaric Acid on the Printable, Rheological and Mechanical Properties of 3D Printing Sulphoaluminate Cement Paste. Materials 2018, 11, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Ruan, S.; Li, M.; Mo, L.; Unluer, C.; Tan, M.J.; Qian, S. Feasibility study on sustainable magnesium potassium phosphate cement paste for 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 221, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jin, R.; Xu, Y.; Wanatowski, D.; Li, B.; Yan, L.; Yang, Y. Adopting recycled aggregates as sustainable construction materials: A review of the scientific literature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 218, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, A.V.; Mohan, M.K.; De Schutter, G.; Van Tittelboom, K. 3D printable concrete with natural and recycled coarse aggregates: Rheological, mechanical and shrinkage behaviour. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, D.; Dorigato, A. Novel uses of recycled rubber in civil applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2022, 5, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Burnett, L.; Smith, J.V.; Markovski, S.; Rodwell, G.; Rahman, M.T.; Maghool, F. Recycling waste rubber tyres in construction materials and associated environmental considerations: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambucci, M.; Marini, D.; Valente, M. Tire Recycled Rubber for More Eco-Sustainable Advanced Cementitious Aggregate. Recycling 2020, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, G.B.; Mushule, N.; Lakshmipathy, M. A Review on Construction Technologies that Enables Environmental Protection: Rubberized Concrete. Am. J. Eng. Applied Sci 2008, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulski, M.; Ambrosewicz-Walacik, M.; Hunicz, J.; Nitkiewicz, S. Combustion engine applications of waste tyre pyrolytic oil. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2021, 85, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambucci, M.; Marini, D.; Sibai, A.; Valente, M. Preliminary Mechanical Analysis of Rubber-Cement Composites Suitable for Additive Process Construction. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambucci, M.; Valente, M. Influence of waste tire rubber particles size on the microstructural, mechanical, and acoustic insulation properties of 3D-printable cement mortars. Civ. Eng. J 2021, 7, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambucci, M.; Valente, M.; Sibai, A.; Marini, D.; Quitadamo, A.; Musacchi, E. Rubber-Cement Composites for Additive Manufacturing: Physical, Mechanical and Thermo-Acoustic Characterization. In RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Cui, C.; Yu, J.; Yu, K.; Xiao, J. Fresh and anisotropic-mechanical properties of 3D printable ultra-high ductile concrete with crumb rubber. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 211, 108639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Setunge, S.; Tran, P. 3D concrete printing with cement-coated recycled crumb rubber: Compressive and microstructural properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, F.; Dale, R.; Hamidi, F.; Valizadeh, A. Mechanical and shrinkage performance of 3D-printed rubberised engineered cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 339, 127665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambucci, M.; Sibai, A.; Fattore, L.; Martufi, R.; Lucibello, S.; Valente, M. Finite Element Multi-Physics Analysis and Experimental Testing for Hollow Brick Solutions with Lightweight and Eco-Sustainable Cement Mix. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Sambucci, M.; Sibai, A.; Iannone, A. Novel cement-based sandwich composites engineered with ground waste tire rubber: Design, production, and preliminary results. Mater. Today Sustain. 2022, 20, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougan, M.; Ghaffar, S.H.; Jahanzat, M.; Albar, A.; Mujaddedi, N.; Swash, R. The influence of nano-additives in strengthening mechanical performance of 3D printed multi-binder geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, O.Y.; Soylemez, H.; Kaplan, G.; Benli, A.; Gencel, O.; Turkoglu, M. Effect of cement dosage and waste tire rubber on the mechanical, transport and abrasion characteristics of foam concretes subjected to H2SO4 and freeze–Thaw. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, H.G.; Mardani-Aghabaglou, A. Assessment of materials, design parameters and some properties of 3D printing concrete mixtures; a state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 125865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjian, E.; Khorami, M.; Maghsoudi, A.A. Scrap-tyre-rubber replacement for aggregate and filler in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1828–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.S.; Gupta, R.C. A comprehensive review on the applications of waste tire rubber in cement concrete. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunothayan, A.R.; Nematollahi, B.; Ranade, R.L.; Bong, S.H.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Khayat, K.H. Fiber orientation effects on ultra-high performance concrete formed by 3D printing. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.B.N.; Khitab, A. Enhancing physical, mechanical and thermal properties of rubberized concrete. Eng. Technol. Q. Rev. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Ma, G. Freeze-thaw resistance of 3D-printed composites with desert sand. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Du, B. Experimental studies of thermal and acoustic properties of recycled aggregate crumb rubber concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntharalingam, T.; Gatheeshgar, P.; Upasiri, I.; Poologanathan, K.; Nagaratnam, B.; Rajanayagam, H.; Navaratnam, S. Numerical Study of Fire and Energy Performance of Innovative Light-Weight 3D Printed Concrete Wall Configurations in Modular Building System. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Liew, K.M. Assessing recycling potential of carbon fiber reinforced plastic waste in production of eco-efficient cement-based materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobeiri, V.; Bennett, B.; Xie, T.; Visintin, P. A comprehensive assessment of the global warming potential of geopolymer concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Li, M.; Ruan, S.; Wong, T.N.; Tan, M.J.; Yeong, K.L.O.; Qian, S. Comparative economic, environmental and productivity assessment of a concrete bathroom unit fabricated through 3D printing and a precast approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, O.; Pasqualino, J.C.; Castells, F. Environmental performance of construction waste: Comparing three scenarios from a case study in Catalonia, Spain. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Seidy, E.; Sambucci, M.; Chougan, M.; Al-Kheetan, M.J.; Biblioteca, i.; Valente, M.; Ghaffar, S.H. Mechanical and physical characteristics of alkali-activated mortars incorporated with recycled polyvinyl chloride and rubber aggregates. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 60, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, S.; Giugliano, M.; Massarutto, A.; Ragazzi, M.; Saccani, C. Material and energy recovery in integrated waste management systems: Project overview and main results. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2057–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffetti, D.; Crotti, E.; Gazzaniga, G.; Carrara, M.; Pastore, T.; Coppola, L. Pathways towards sustainable concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 154, 106718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Aslani, F. Development of fibre reinforced engineered cementitious composite using polyvinyl alcohol fibre and activated carbon powder for 3D concrete printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 303, 124453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlonetti, G. Study of Advanced Cement-Based Materials for Additive Manufacturing. Ph.D. Dissertation, Università Politecnica delle Marche—Scuola di Dottorato di Ricerca in Scienza dell’Ingegneria, Ancona, Italy, February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä, M.; Shi, A.; Shirowzhan, S.; Sepasgozar, S.; Liu, C. 3D printing architectural freeform elements: Challenges and opportunities in manufacturing for industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 36th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction (ISARC), Banff, AB, Canada, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 1298–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, A.E. Compressive strength of concrete with polypropylene fibre additions. Struct. Surv. 2006, 24, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C109/C109M-20a; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or [50- mm] Cube Specimens). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Kanellopoulos, A.; Petrou, M.F.; Ioannou, I. Durability performance of self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C 1202; Standard Test Method for Electrical Indication of Concrete’s Ability to Resist Chloride Ion Penetration. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Jedinak, R. Energy efficiency of building envelopes. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 855, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambucci, M.; Valente, M. Ground Waste Tire Rubber as a Total Replacement of Natural Aggregates in Concrete Mixes: Application for Lightweight Paving Blocks. Materials 2021, 14, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7984; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Thermal Effusivity of Fabrics Using a Modified Transient Plane Source (MTPS) Instrument. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Karger-Kocsis, J.; Mészáros, L.; Bárány, T. Ground tyre rubber (GTR) in thermoplastics, thermosets, and rubbers. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemnitz, M.; Schreck, G.; Krüger, J. Analyzing energy consumption of industrial robots. ETFA2011 2011, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Sambucci, M.; Chougan, M.; Ghaffar, S.H. Reducing the emission of climate-altering substances in cementitious materials: A comparison between alkali-activated materials and Portland cement-based composites incorporating recycled tire rubber. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).