1. Introduction

Oily sludge is a complex emulsified waste primarily composed of water, oil, and solid particles, generated during oil exploitation, transportation, storage, and refining processes [

1]. With the rapid development of the global oil industry, more than 10 million tons of oily sludge are produced annually worldwide [

2]. Oily sludge contains toxic and harmful substances, such as crude oil, benzene series compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and heavy metals [

3]. If improperly managed or leaked during disposal, these pollutants can enter the surrounding environment through soil infiltration and aqueous diffusion, leading to severe consequences for the ecosystem. As reported by Johnston et al. [

4], persistent organic pollutants and bioaccumulative heavy metals from oily sludge can accumulate in the human body via the food chain, posing irreversible health risks upon long-term exposure. Therefore, environmentally sustainable, safe, and non-polluting treatment technologies are essential for the disposal of oily sludge.

Oily sludge contains large amounts of surfactants, colloidal asphaltenes, and fine particles, which contribute to the formation of highly stable emulsions and render efficient treatment difficult using a single technology [

5]. Integrated approaches combining physical, chemical, and biological methods are commonly used to treat oil sludge in engineering, including conventional techniques such as solvent extraction, thermal decomposition, biological treatment, ultrasonic deoiling, and chemical thermal washing [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The three phases of water, oil, and solid in oily sludge are tightly bound through emulsification, forming interfacial films with high mechanical strength that are resistant to disruption. These highly stable oil-bearing interfacial structures significantly hinder effective separation, leading to high energy consumption, low treatment efficiency, and severe secondary pollution in the current treatment process [

3,

10]. Therefore, effectively destabilizing the emulsified structure of oily sludge interface films is critical for achieving optimal separation of the oil–water–solid three-phase system and has become the primary, crucial step in oily sludge disposal. Recently, chemical demulsifiers and high-temperature heating have been utilized to demulsify oily sludge in engineering [

7,

11]. These methods exhibit low efficiency in removing oil films from the surfaces of solid particles, leading to high residual oil content in subsequent processes, along with substantial consumption of chemicals and energy. Meanwhile, residual chemicals may induce secondary pollution in subsequent treatments [

12]. Therefore, improving the demulsification efficiency of oily sludge is crucial for developing new green and efficient technologies for its harmless disposal.

Micro–nanobubbles (MNBs) are bubbles with diameters ranging from several hundred nanometers to several tens of micrometers, characterized by high mass transfer efficiency, high surface potential, and the ability to generate hydroxyl radicals (·OH). It is worth noting that in practical engineering applications, the existing MNB generation technology usually generates a bubble system in which microbubbles (MBs) and nanobubbles (NBs) coexist, making it difficult to achieve size separation [

13]. Moreover, bubbles within this size range exhibit good dynamic stability. In addition, bubbles of different sizes possess their unique advantages and play different roles. Specifically, NBs have long residence times and large specific surface areas, which can significantly enhance gas dissolution, mass transfer, and interfacial reactions, leading to increased ·OH production [

14,

15]. MBs can produce intense physical disturbances of strong pressure waves and high-speed microjets through their collapse behavior during their ascent [

16].

In the ozone micro–nanobubble (O

3MNB) system, the high specific surface area and prolonged residence time of MNBs promote contact between ozone and aromatic hydrocarbons, which significantly improve the oxidative degradation process of aromatic hydrocarbons in crude oil. Within just 30 min of reaction time, the degradation rates of toluene, ethylbenzene, o-xylene, and p-xylene in crude oil by O

3MNBs reached 55.8%, 60.6%, 63.7%, and 64.7%, respectively [

17]. In addition, O

3MBs generate more ·OH than air and oxygen MBs. During the flotation process of coking wastewater, the removal rate of oil in water by O

3MBs can reach up to 99% [

18]. These facts demonstrate that MNB technology can not only prolong the contact time and adhesion probability between bubbles and pollutants but also promote the generation of ·OH to facilitate the decomposition of organic chemicals, which makes MNB technology widely applicable in the field of oily wastewater treatment.

MNB technology has also been applied in the field of oil pollution. It has been found that self-collapsing air–MBs (d

p < 50 μm) can form a high-pressure point at the end of the collapse process, thereby generating pressure waves [

19]. These pressure waves are helpful for removing oil from the surface of sand particles, and the oil removal rate can reach 95% with the combined treatment of mechanical stirring. In addition, MBs can be used as a substitute for locating oil leakage, providing a stable simulation target for acoustic detection [

20]. Because MBs have similar buoyancy and aggregation characteristics to oil droplets, a low rising rate, and good acoustic scattering performance. When MBs are released, they form a plume similar to that produced during an oil leakage.

Although MNB technology has demonstrated good potential in the field of oily wastewater treatment and oil pollution remediation, the physical morphology, interface structure, and pollution occurrence state of oily sludge as a highly stable oil–water–solid three-phase emulsification system are essentially different from those of oily wastewater. As a result, there are only a few reports regarding the application of MNB technology to oily sludge demulsification. Therefore, it is of great significance to systematically explore the operating conditions and demulsification mechanisms of MNBs in the oily sludge systems for the development of efficient, green, and harmless oily sludge treatment technologies.

Currently, research on the demulsification mechanisms and pathways of oily sludge mainly focuses on the chemical demulsification process. Upon addition of a demulsifier to the emulsion, the demulsifier increases the probability of droplet collision and aggregation by eliminating the oil films on the water–oil interface and acting as a bridge between droplets, thereby causing emulsion instability and achieving demulsification [

21]. Polyethyleneimine (PEI), a nonionic demulsifier, can replace the natural surfactants in polymer flooding wastewater to form a new “oil–PEI–water” emulsion. When the temperature increases to the phase transition temperature, the stability of the emulsion decreases, and emulsion demulsification can be achieved by simple stirring [

22]. In addition, certain oxidative surfactants can not only increase the solubility of oil but also in situ oxidize complex organic substances in water to achieve demulsification of oily sludge. For instance, ·OH and ·SO

4− generated in situ after activation of persulfate can degrade complex organic compounds into shorter molecules, achieving an oil removal rate of 94.6% [

23]. From the above demulsification process of the chemical demulsifiers, it is clear that current demulsification approaches rely on the addition of chemical agents into the oily sludge system. Although these methods can achieve effective demulsification, the non-recyclable nature of the agents complicates subsequent treatment processes and may lead to secondary pollution. Therefore, it is essential to explore the demulsification mechanism of MNB technology to address the above problems, providing a foundation and reference to the demulsification mechanism of MNBs.

In recent years, with growing global emphasis on environmental protection and the circular economy, the demand for green, low-carbon, and efficient oily sludge treatment technology has become increasingly urgent. Traditional chemical demulsification methods are gradually limited due to secondary pollution and high resource consumption. MNB technology, as a physical–chemical synergistic method without the addition of chemicals, conforms to the development trend of carbon neutralization. However, the current research on MNBs in oily sludge treatment is still in its infancy, and there is a lack of systematic research on its demulsification mechanisms and operating conditions, which limits its promotion in engineering. In the future, the combination of MNBs with other green technologies may further improve the treatment efficiency and resource recovery rate of oily sludge.

Based on the above, this study independently built an MNB demulsification system for oily sludge, using ozone and nitrogen as gas sources. By measuring the oil distribution characteristics in oily sludge and the water quality indices before and after demulsification, the effects of MNBs were obtained. Furthermore, by analyzing the variations in oily sludge components before and after demulsification, the study focused on elucidating the role of O3MNBs in strengthening water–oil–solid separation, as well as the stability mechanism of ozone within MNB aqueous and its demulsification pathway. Therefore, this study aims to promote the development of a new green and efficient oily sludge demulsification technology, providing technical support to reduce dependence on and secondary pollution related to chemical demulsification. By strengthening the three-phase separation of oily sludge, the proposed approach promotes the recovery and utilization efficiency of both oil and solid phases, thereby promoting the upgrade and development of the oil sludge treatment process and facilitating resource recovery and the circular economy.

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of MNBs Under Different Gas Source Conditions

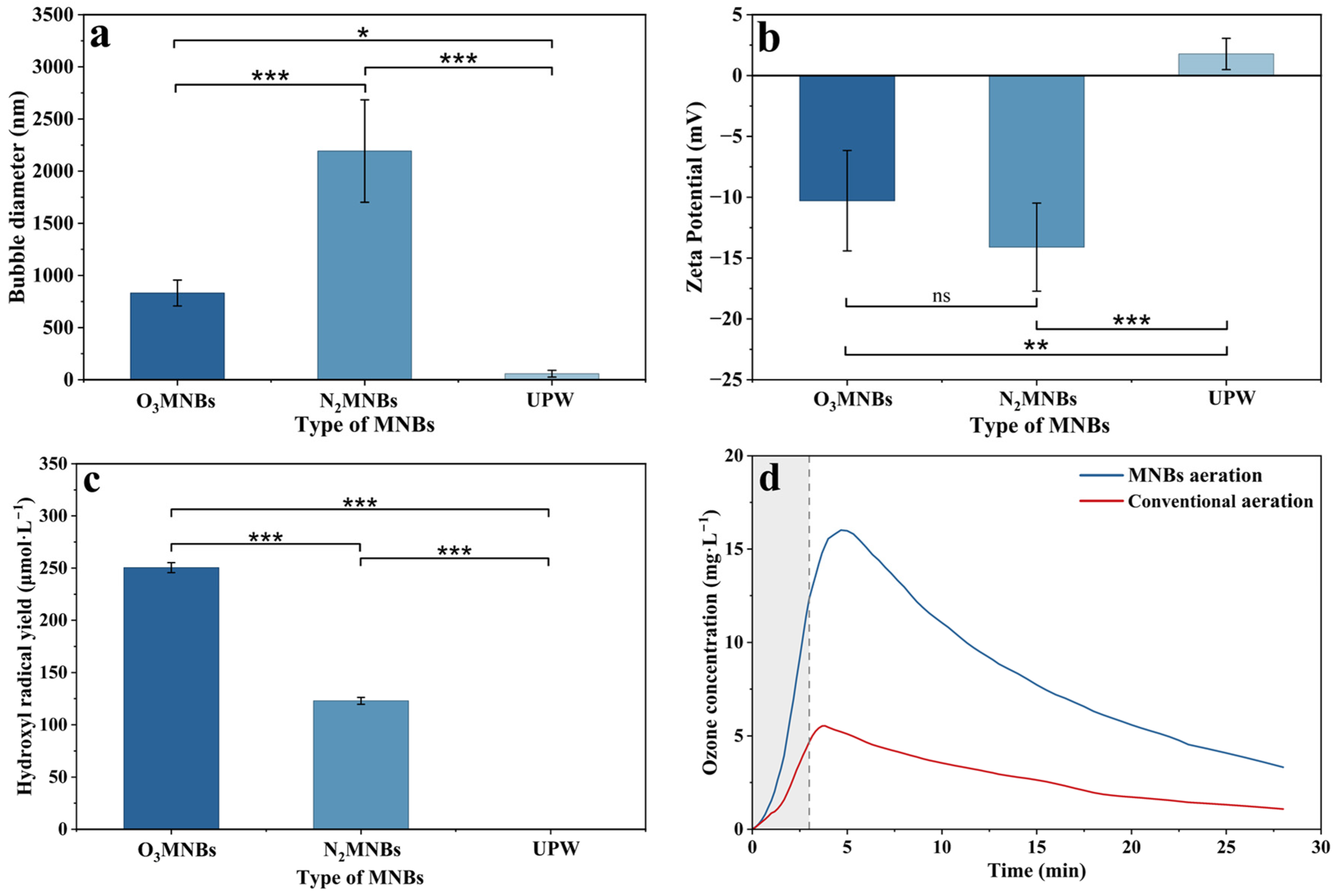

In water, this study, MNBs were generated in situ by different gas sources, and their effects were analyzed after 3 min of bubble generation. As shown in

Figure 1, the particle size distribution of MNBs (

Figure S1) in water ranged from 752 to 2760 nm, indicating that MNBs can be generated using different gas sources. The particle size of O

3MNBs (831 ± 124 nm) was the smallest, which was 62.1% smaller than that of N

2MNBs (2193 ± 491 nm). The zeta potential of MNBs ranged from −17.9 to −5.6 mV, and the absolute zeta potential of N

2MNBs (−14.1 ± 3.6 mV) was the highest, which was 27.07% higher than that of O

3MNBs (−10.3 ± 4.1 mV).

The concentration of ·OH in water ranged from 121.1 μmol·L−1 to 253.2 μmol·L−1, and the ·OH concentration of O3MNBs (250.4 ± 4.8 μmol·L−1) was 104% higher than that of N2MNBs (122.9 ± 3.3 μmol·L−1). This study investigated the concentration of ozone dissolved in water under both MNB aeration and conventional aeration. It was found that after 3 min of aeration, the concentration of ozone dissolved in water under MNB aeration reached 16.4 mg·L−1, which was 192% higher than that under conventional aeration (5.6 mg·L−1). After 25 min of stopping aeration, the concentration of ozone dissolved in the water under MNB aeration still achieved 3.4 mg·L−1, which was 213% higher than that of traditional aeration (1.1 mg·L−1).

2.2. Effects of MNBs on the Distribution Characteristics of Oil and Water Quality After Demulsification

The effects of MNBs on the distribution characteristics of oil and water quality after demulsification, as shown in

Figure 2, reveal a gradual decrease in the oil content of the solid phase from 29.7% to 18.4%, indicating a decrease of 11.3% (

Figure 2a,b). Meanwhile, the oil content in the liquid phase exhibited slight fluctuations and was consistently maintained at a very low level, accounting for approximately 0.3%. This result indicates that the demulsification process can significantly reduce the oil content in the solid phase of the oily sludge. In addition, the oil removal rate of MNBs (41.1%) was 28.7% higher than that of the CK group (31.9%). Among different gas sources, the oil removal rate of O

3MNBs (41.5%) was the highest, which was 2.1% higher than that of N

2MNBs (40.7%).

The demulsification process of oily sludge by MNBs caused a significant increase in COD and TOC concentrations in the aqueous phase. As shown in

Figure 2c,d, the average values of COD and TOC after demulsification of MNBs were 298.2 ± 46.9 mg·L

−1 and 167.5 ± 15.6 mg·L

−1, which were 101% and 51% higher than those of the CK group (COD = 148.1 ± 16.9 mg·L

−1, TOC = 110.9 ± 10.6 mg·L

−1), respectively. This result shows that MNBs can promote the transfer of organic matter from the solid phase to the aqueous phase. For different gas sources, the COD after O

3MNB treatment (287.0 ± 33.5 mg·L

−1) was 7.2% lower than that of N

2MNBs (309.4 ± 57.6 mg·L

−1), while the TOC of O

3MNBs (179.0 ± 8.4 mg·L

−1) was 14.7% higher than that of N

2MNBs (156.0 ± 12.3 mg·L

−1), which may be related to the characteristics of ozone itself. In addition, different environmental conditions had no significant effects on ORP and pH values of the aqueous phase during demulsification.

It is worth noting that the demulsification effects were optimal when the demulsification time lasted for 15 to 20 min (with the lowest solid-phase oil content). Therefore, to shorten the experimental duration and reduce human error, this study selected the test sample of demulsification time of 15 min to analyze the morphology, composition, thermogravimetric characteristics, and other indicators of the solid-phase oily sludge after demulsification and to deeply analyze the demulsification mechanism of MNBs on oily sludge.

2.3. Effects of MNBs on the Surface Morphology Characteristics of Oily Sludge

After demulsification treatment, the oily sludge formed a distinct three-layer mixture of oil, water, and solid (

Figure S2). The stratification phenomenon after O

3MNB treatment was the clearest, with the oil phase floating up, the aqueous phase being transparent, and the solid phase settling at the bottom with clearly defined interfaces. This indicates that the demulsification performance of O

3MNBs was significantly better than that of tap water and N

2MNBs. To deeply explore the demulsification effects on the structure of oily sludge, the surface morphology of solid-phase oily sludge before and after demulsification was analyzed by SEM, as shown in

Figure 3a–d.

As shown in

Figure 3a, the original oily sludge exhibited strong viscosity, with particles interconnecting with each other. The structure was relatively dense, characterized by few pores and cracks, and the surface was covered with reflective oil films, forming a tightly bound oil–solid aggregate. After demulsification treatment, the agglomeration structure of the oily sludge particles was disrupted, the dispersion of particles was improved, the surface oil substances were reduced, and the whole tended to be loose. Among the treatments, the demulsification effect of O

3MNBs was the best. As shown in

Figure 3c, oily sludge particles were significantly dispersed after O

3MNB treatment, aggregates were dissociated, and only minimal oil film residues remained on the surface. After N

2MNB treatment, although the oily sludge particles were slightly dispersed, there were still large aggregates, and a small amount of oil residue could be seen on the surface (

Figure 3d). In contrast, the dispersion degree of oily sludge particles was the lowest after the CK group, with large aggregates and thick oil films on the surface, resulting in the poorest demulsification effect (

Figure 3b).

Through EDS analysis, the elemental composition changes in the oily sludge were further analyzed, as shown in

Figure 3e–h. As can be seen in

Figure 4e, the mass fraction of the carbon element in the original oily sludge was as high as 84.96%. While the oxygen element was only 9.73%, the mass fraction of secondary elements such as silicon, magnesium, aluminum, calcium, and iron was relatively low.

After demulsification treatment, the carbon content decreased significantly, while silicon and oxygen exhibited an enrichment trend. The O

3MNB treatment achieved the best demulsification performance. As shown in

Figure 3g, the mass fraction of carbon decreased to 62.48%. In comparison, the mass fraction of oxygen increased to 25.41%, and the mass fractions of silicon, aluminum, and magnesium also increased. Combined with SEM images, these results indicate that a substantial amount of oil was desorbed and decomposed, leading to the exposure of inorganic solid components within the oily sludge. After N

2MNB treatment, the carbon content was 62.9% higher than that of the O

3MNB group, the oxygen content was 27.83%, and the mass fraction of silicon, magnesium, and other elements increased slightly (

Figure 3h), indicating that the oil removal was incomplete and that the residual oil had combined with some impurities. The elemental composition of the CK group was similar to that of the MNB group. However, the carbon content was higher at 66.08%, and the oxygen content was 24.22% (

Figure 3f). Combined with SEM images, the results showed that there was only a small amount of oil removal in the CK group, and the oil–solid structure was not substantially destroyed.

2.4. Effects of MNBs from Different Gas Sources on the Solid-Phase Components of Oily Sludge

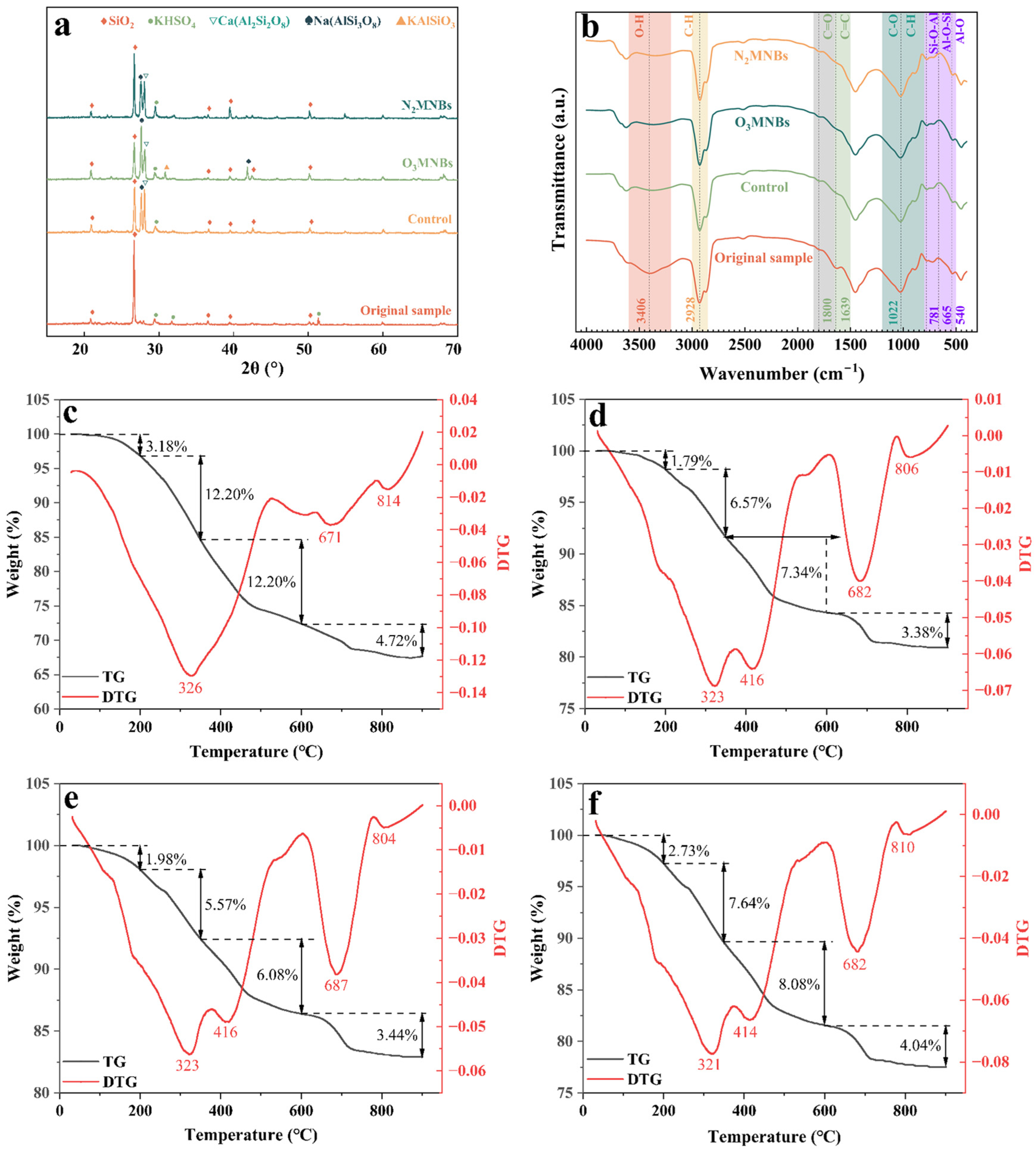

In order to explore the effects of MNBs on the functional groups and mineral phase structure of oily sludge, XRD and FTIR were used to test samples. The results are shown in

Figure 4. By comparing the XRD spectra of

Figure 4a with the standard card, it was found that the XRD spectra of the original oily sludge were dominated by the characteristic peak of quartz (SiO

2), with a strong and sharp diffraction peak. After demulsification treatment of MNBs, distinct peaks of aluminosilicate minerals with potassium bisulfate (KHSO

4), anorthite (CaAl

2Si

2O

8), potassium feldspar (KAlSi

3O

3), and albite (NaAlSi

3O

8) as the main components appeared in the spectrum. The characteristic peak intensities of NaAlSi

3O

8 and CaAl

2Si

2O

8 were significantly enhanced after O

3MNB treatment. After N

2MNB treatment, the SiO

2 characteristic peak was still the most significant, while the three peak intensities of SiO

2, CaAl

2Si

2O

8, and NaAlSi

3O

8 in the CK group were basically the same.

FTIR spectra of the original oily sludge showed strong absorption at 3200–3600 cm

−1, 2850–3000 cm

−1, 1500–1650 cm

−1, 1650–1850 cm

−1, 800–200 cm

−1, and 500–800 cm

−1 (

Figure 4b). The region between 3200 and 3600 cm

−1 is the stretching vibration of O-H bonds in water. The broadband between 2850 and 3000 cm

−1 may correspond to the stretching vibration of the C-H bonds in alkanes. The region between 1500 and 1650 cm

−1 is aliphatic and aromatic groups, and the higher wavenumber at 1639 cm

−1 corresponds to the C=C bonds. The region between 1650 and 1850 cm

−1 is the stretching vibration of the C=O double bonds, which usually represents the presence of carbonyl groups in the molecule. The region between 800 and 1200 cm

−1 contains the stretching vibration of C-O bonds and the bending vibration of C-H bonds. Combined with the XRD spectra, the region between 500 and 800 cm

−1 is the bending vibration of Si-O-Al bonds, Al-O-Si bonds, and Al-O bonds of aluminosilicate minerals.

After demulsification treatment with MNBs, the absorption peaks of C-H bonds and C=C bonds were significantly weaker than those of the CK group, and the absorption peak of O-H bonds was narrower than that of the CK group. This finding shows that MNBs simultaneously achieved the oxidation of functional groups in oily sludge during the demulsification process. For different gas sources, the absorption peak of the C-H bonds of alkanes in the N2MNB treatment group decreased to a certain extent, but it was still significantly stronger than that in the O3MNB treatment group; the broadening degree of the O-H bonds absorption peak was also weaker than that of the O3MNB treatment group. The O3MNB treatment group had an obvious C=O bond absorption peak at 1800 cm−1, indicating that oxidation had occurred. Meanwhile, the absorption peaks in the 500–800 cm−1 region of the O3MNB treatment group were significantly enhanced, indicating an increase in the exposure of minerals in the oily sludge.

Further thermodynamic analysis of the solid-phase samples was conducted through quantitative characterization of the oily sludge component content (see

Figure 4). Using the TG profile in the diagram, we observed that the total weight loss rate of the original oily sludge was 32.3%. After demulsification, the weight loss rate of the sample was reduced significantly, with an average reduction of 12.53%. A robust decline in the oily sludge weight loss rate was achieved by the O

3MNB treatment (15.23%), which was 21.84% and 54.93% higher than that of the CK group and the N

2MNB treatment group, respectively. Additionally, the TG analysis of the oily sludge can be divided into four main stages, each corresponding to the volatilization and decomposition of different components.

The first stage, from room temperature to 200 °C, is the loss of water and low-boiling-point volatile components. In this stage, the weight loss of all samples was ambiguous, and the DTG profile was relatively flat.

In the second stage, ranging from 200 to 350 °C, the key processes are the volatilization and cracking of light components such as saturated hydrocarbons and aromatic hydrocarbons. The most significant DTG weight loss peak profile was around 323 °C. The maximum weight loss rate of the original oily sludge was 12.20%, while the lowest was 5.57% in the O3MNB treatment group and 7.64% in the N2MNB treatment group, which was slightly higher than that of the CK group (6.57%).

The third stage, ranging from 350 to 600 °C, corresponded to the pyrolysis of heavy components such as resin and asphaltene. The DTG profile showed an evident weight loss peak at 416 °C. The O3MNB treatment group still had the lowest weight loss rate of 6.08%, which was significantly lower than that of the original sample (12.20%).

The fourth stage of 600–900 °C mainly involves the decomposition of aluminosilicate and the combustion of fixed carbon. After demulsification, the weight loss peak of the samples in this range became more prominent, and the peak temperature also increased. The peak temperature of the O3MNB treatment group was the highest at 687 °C, indicating that the thermal stability of the residual components was enhanced with an effective degradation of heavy oil.

3. Discussion

Previous studies [

13,

15] have demonstrated that MNBs can extend the contact time and enhance the attachment efficiency between bubbles and pollutants while also promoting ·OH generation that facilitates the decomposition of organic compounds. The demulsification mechanism in oily wastewater has been studied. However, oily sludge presents a more complex and stable emulsion structure. Its interfacial films, composed mainly of natural surfactants such as asphaltenes and resins, possess high mechanical strength that hinders droplet coalescence and limits complete separation during demulsification [

5]. Therefore, elucidating the demulsification mechanism of O

3MNBs in oily sludge is essential for developing efficient and sustainable treatment technologies.

Based on this, this study found that compared with conventional ozone aeration, the ozone concentration and residence time in O

3MNB water both increased. These findings are correlated with the rising velocity of bubbles in water, which follows the Hadamard–Rybczynski equation, where the rising velocity of bubbles increases proportionally to the square of the bubble diameter. According to the calculation of the particle size data (this procedure is detailed in the supplementary document), the rising velocity of O

3MNBs in water was 1.12 μm·s

−1, which is much lower than the reported value (0.21 m·s

−1) of traditional large bubbles (d

p = 1.62 mm) [

24]. This results in a significant extension of MNB residence time in water, creating favorable conditions for the dissolution and mass transfer processes of ozone. Furthermore, it was observed in the experiment that the attenuation rate of dissolved ozone in the O

3MNB solution was significantly lower than that of conventional aerated ozone water, indicating that the presence of MNBs not only prolongs the gas–liquid contact time but may also affect the quality transfer process of ozone through the interface effect. Ozone exists in water in the form of MNBs. According to Henry’s law, when the dissolved ozone in water is decomposed, the concentration equilibrium at the gas–liquid interface is disrupted, which promotes the continuous dissolution of ozone in bubbles [

25].

This study also found that the zeta potential of MNB water was negative (from −17.9 to −5.6 mV), confirming that the bubble surface carries negative charges. This characteristic may be related to the asymmetric distribution of ions at the gas–liquid interface and the structure of the interface double layer [

26]. Furthermore, the experimental observation revealed that the ·OH concentration in O

3MNB water measured in this study is approximately twice that in N

2MNB water, suggesting that ozone micro–nanobubbles may promote the generation of free radicals at the interface through charge effects. Due to the unique spontaneous contraction mechanism of MNBs, the charge density on the surface of the bubble’s double electric layer increases rapidly during this contraction process [

27]. At the moment of bubble collapse, energy is released, resulting in extreme conditions of local high temperature and high pressure, which are sufficient to break the O-H bonds and promote water decomposition to generate large amounts of ·OH [

28]. In addition, ozone molecules exhibit strong oxidizing properties and can directly generate highly reactive oxygen species, such as ·O or ·O

2−, through electron transfer processes. These free radicals can further react with water molecules to generate ·OH radicals [

29].

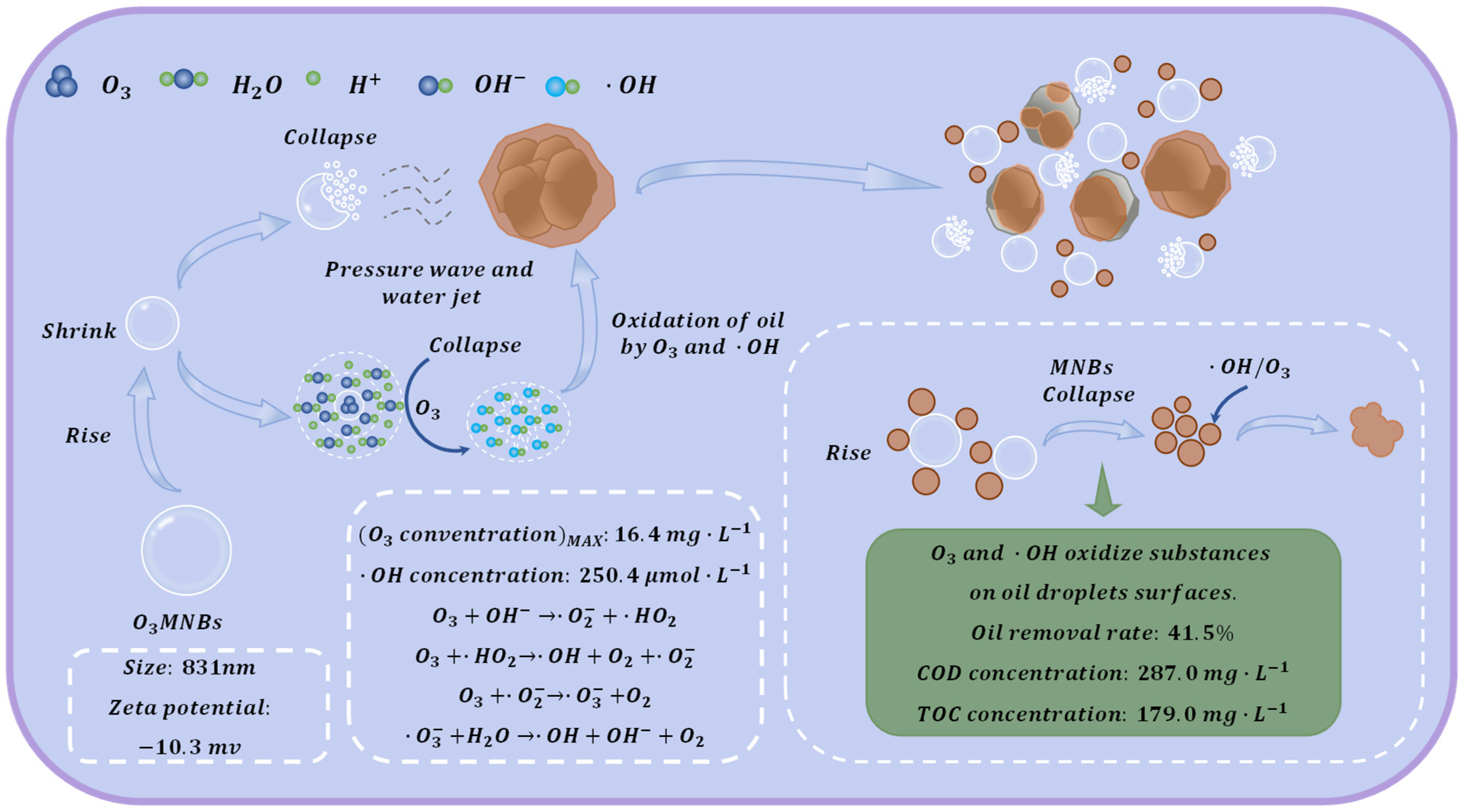

Moreover, O

3MNBs extend ozone residence time and promote the in situ generation of abundant ·OH through bubble collapse and ozone decomposition, offering better conditions for efficient oily sludge demulsification. The results showed that O

3MNB treatment effectively achieved oil–water–solid three-phase separation, with an average oil removal rate of 41.1%. The SEM observations in this study confirmed that after O

3MNB treatment, sludge particles became highly dispersed, aggregates were entirely dissociated, and no evident oil films remained. It is worth noting that the MNBs used in this study are a composite system containing NBs and MBs, which play a synergistic role in the demulsification process. As MBs rise, their diameter gradually decreases, increasing the internal gas pressure and promoting rapid gas diffusion into the surrounding liquid. This process culminates in bubble collapse, generating strong pressure waves and high-speed microjets that physically disrupt sludge aggregates and strip oil films from the particle surface [

30]. The physical dispersion effect of the bubbles provides sufficient interface contact conditions for the subsequent oxidation reaction.

FTIR spectra revealed that the C-H bond absorption peaks were significantly weakened after O

3MNB treatment. EDS confirmed a drop in carbon element and an increase in oxygen content on the solid surface, suggesting effective oxidation of oil films. Due to its large specific surface area and long residence time, NBs can enhance the solubility of ozone in water and promote the formation of ·OH, providing a stable chemical oxidation environment. During demulsification, ozone and ·OH attack C-H bonds, particularly in alkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons, including chain scission and oxidation reactions [

23,

31]. This synergistic mechanism of NB-dominated oxidation and MB-dominated fragmentation makes the MNB system show more comprehensive demulsification ability than single-size bubbles when dealing with complex oil sludge.

Furthermore, ozone and ·OH further attack natural surfactants, stabilizing the emulsion, disrupting their structure, and causing oil droplets to lose stability and coalesce [

32]. The oxidation of hydrophobic substances on oil droplet surfaces into hydrophilic compounds improves oil–water separation. At the same time, ozone and ·OH continuously oxidize dissolved petroleum hydrocarbons, decomposing them into small organic molecules and eventually mineralizing them into CO

2 and H

2O [

33]. These oxidation processes explain the observed increases in TOC and COD values after O

3MNB treatment. The demulsification pathway of O

3MNBs is shown in

Figure 5.

Overall, O3MNBs-based demulsification operates through a synergistic combination of physical disruption and chemical oxidation. This study demonstrates that O3MNBs provide a promising, environmentally friendly strategy for efficient oily sludge treatment and lays a foundation for future research on O3MNB demulsification mechanisms. However, this study has certain limitations. Firstly, the influence of the particle size distribution of MNBs on the demulsification effect has not been systematically explored. Secondly, the quantitative relationship between ozone mass transfer and free radical generation still needs to be further investigated. Moreover, the observed increase in TOC and COD values in the experiment indicates that the accumulation of oxidation intermediate products may affect the subsequent treatment, and the transformation pathway and regulation methods of these products deserve in-depth study. In subsequent studies, we will systematically compare the treatment efficacy of O3MNBs, O2MNBs, and air–MNBs to further elucidate the distinct mechanisms by which ozone promotes demulsification, thereby establishing a more comprehensive foundation for the practical application of this technology.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental System for Demulsification of Oily Sludge by MNBs

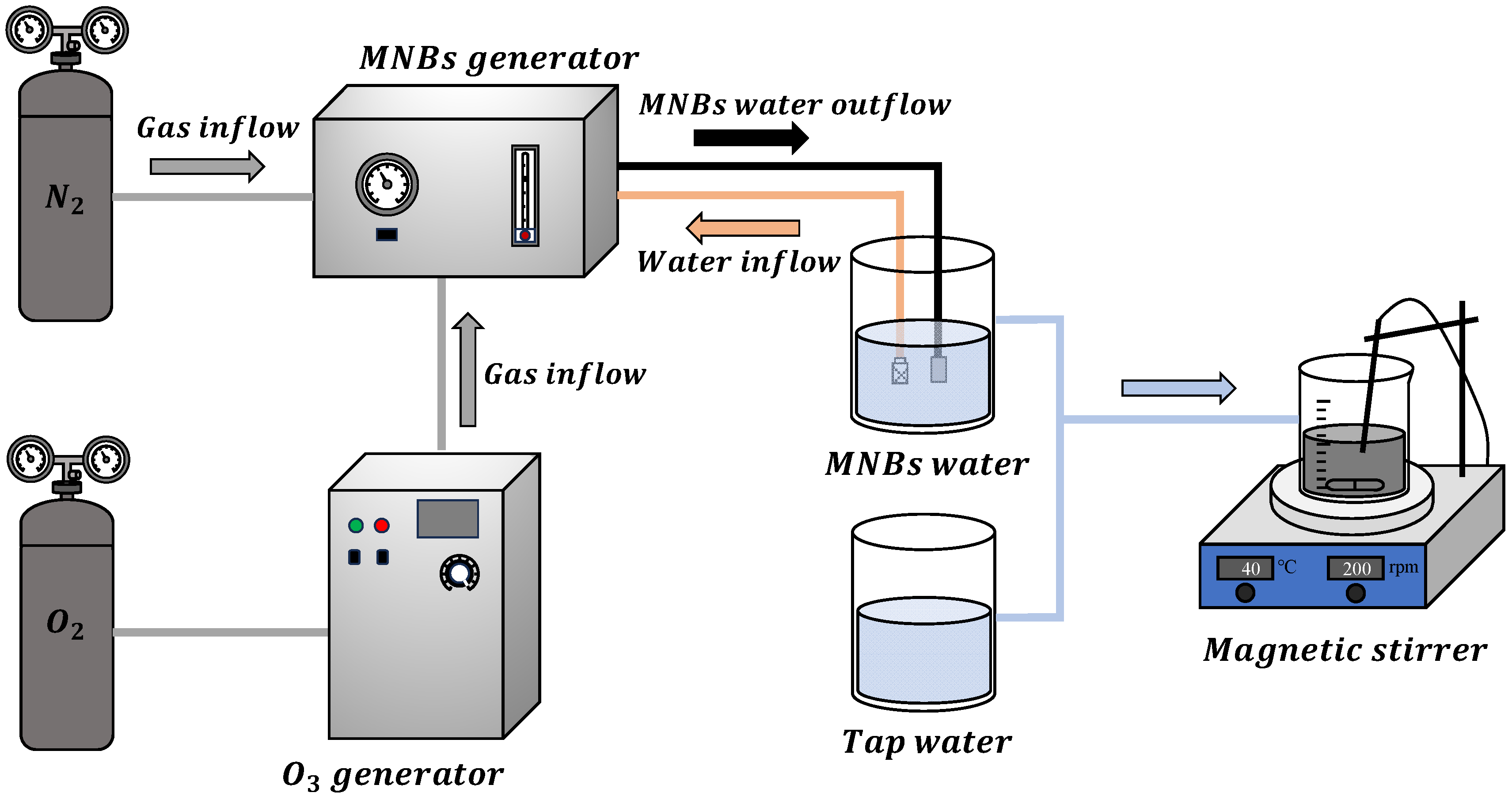

The experimental oily sludge samples were collected from the Dagang Oilfield in Tianjin, China (with an oil content of 29.7%).

Figure 6 shows the proposed experimental system setup. The corona discharge ozone generator was used to generate ozone (10 g·h

−1) with air as the gas source. The MNB generator (RD-NM-200, RuiDe ZhiChuang Innovation Technology (Tianjin) Co., Ltd, Tianjin, China) was used to prepare MNBs with nitrogen and ozone as gas sources, at a working pressure of 0.4 MPa and a gas flow rate controlled at 150 mL·min

−1, with tap water as the medium. In the experiment, tap water was set as the control group (CK group) to evaluate the demulsification effect of physical stirring alone. N

2MNBs were selected to eliminate the interference of the physical properties of MNBs, thereby verifying that the oxidation of ozone plays a role in the demulsification. The specific operation process of the demulsification experiment was as follows: A 30.0 g oily sludge sample was placed in the flask, and 150.0 g of tap water, O

3MNB water, or N

2MNB water was added to the flask according to a solid–liquid mass ratio of 1:5. The magnetic heating stirrer was set at 40 °C and 200 rpm for stirring, and the reaction time was 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. After the reaction, the mixture was centrifuged to obtain three-phase samples (oil, water, and solid), which were used to determine the oil content, COD, TOC, pH, ORP, and other parameters. All the experiments were conducted in three parallel trials.

4.2. Analysis Method

The particle size and zeta potential of the bubbles were measured by a Zetasizer nanoparticle size analyzer (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid (4-HBA) was selected as the ·OH capture agent. The 3,4-DHBA concentration was used to calculate the production of ·OH by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Waters Alliance E2695, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) combined with an ultraviolet detector. The concentration of ozone dissolved in water was monitored by an ozone water concentration detector (PGD3-UV, Shenzhen Xinhairui Technology Development Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The chemical oxygen demand (COD) of water samples was calculated by measuring the absorbance using a rapid digestion spectrophotometric method and a UV spectrophotometer (SH-6600, Jiangsu Sheng’aohua Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China). The total organic carbon (TOC) was analyzed by a total organic carbon analyzer (TOC-L CPN, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). pH and oxidation–reduction potential (ORP) of the aqueous phase were analyzed through a pH meter (PHS-300, Jiangsu Sheng’aohua Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China).

The oil content in water, oil, and solid phases was determined through the ultrasonic extraction gravimetric method. The weight loss of the solid samples was measured by a differential thermal–thermogravimetric synergistic analyzer (TG/DTA, DTG-60A, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) under a nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 20 mL/min. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, IRAffinity-1S, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) was used to characterize the functional groups of the oil contaminants on the solid surface. The mineral composition of the solid was analyzed by the X-ray diffractometer (XRD, MiniFlex 600, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The morphological changes in oily sludge before and after the reaction were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Phenom XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.3. Statistical Analyses

The experimental results are expressed as means and standard deviations. To determine whether there were significant differences between the MNB treatment group and the control group, statistical analysis was conducted. Statistical analyses, calculations, and graph generation were performed using Origin 2025b (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) and Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, DC, USA) software.

5. Conclusions

Based on the characteristics of MNBs generated by different gas sources and their demulsification effects on oily sludge, this study explored and examined the demulsification performance and mechanisms of MNBs. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) O3MNBs have excellent physicochemical properties, with a bubble diameter of 831 nm and a concentration of ·OH in water of 250.4 μmol·L−1. Compared with conventional aeration (5.6 mg·L−1), the ozone concentration in O3MNB water (16.4 mg·L−1) increased by 192%.

(2) MNBs generated from different gas sources can effectively demulsify oily sludge. O3MNBs had the highest oil removal rate of 41.5%. The absorption peak of C-H bonds in alkanes in oily sludge after O3MNB treatment was significantly weakened, the weight loss rate of light and heavy components was the lowest, the content of carbon element decreased, and the content of oxygen element increased.

(3) O3MNBs can effectively demulsify oily sludge through physical–chemical synergistic effects. The mechanism involves shockwaves and microjets generated by bubble collapse, as well as the strong oxidation by ozone and ·OH, which promote the detachment of the oil phase from the surface of the solid phase, induce chain scission and hydrophilization of petroleum hydrocarbons, and enhance the oxidation and degradation of petroleum hydrocarbons. These processes can promote the efficient separation of the oil–water–solid three-phase system, improve the recovery and utilization efficiency of both the oil and solid phases, and support resource recovery and the development of a circular economy.