Abstract

Sustainable consumer behavior refers to any behavior that benefits environmental protection and social justice. Previous research has shown that sustainable consumer behavior is positively associated with consumer wellbeing. Recycling behavior is a type of sustainable behavior that has been studied extensively. However, research on behavior change in recycling is limited. The purpose of this study is to identify the change stages for recycling behavior among American consumers. Using national data collected in the U.S. and under the guidance of the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM), the results showed that most Americans engage in recycling behavior, but a minority of them do not. Among them, 13% have never considered recycling in the near future. We also identified the differences in behavior change stages in terms of psychological, cognitive, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. The findings have implications for policy makers, business professionals, and consumer educators to develop strategies to encourage consumer recycling behavior.

1. Introduction

Sustainable consumer behavior refers to any behavior that benefits environmental protection and social justice [1,2]. Research shows that sustainable consumer behavior is positively associated with life satisfaction [3,4]. Recycling behavior is one type of sustainable behavior which has been studied extensively [5,6,7,8,9]. Being willing to recycle and recycling appropriately require certain levels of knowledge and willpower to enact. How to recycle waste appropriately is a challenge to many people since different types of waste need to be recycled differently [10]. Many previous studies have applied the theory of planned behavior to identifying the factors associated with behavior intensions related to recycling [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, research on recycling behavior that focuses on behavior change stages is limited.

The purpose of this study, which is part of a larger study, is to identify the behavior change stages in consumer recycling behavior based on the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM) and to examine consumer group differences between these change stages using national data in the U.S.

The TTM is a theory for identifying factors that facilitate individuals to change their behaviors [22,23]. Unlike other behavior science theories, it defines behavior changes using five stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance). It identifies ten change processes that can be considered potential intervention strategies used by helping professionals, which are consciousness-raising, dramatic relief, social liberation, environmental reevaluation, self-reevaluation, self-liberation, counter-conditioning, stimulus control, reinforcement management, and helping relationships. These change processes are abstracted from major psychological theories [23]. Based on the predication of the TTM, when consumers develop a new desirable behavior or eliminate an old undesirable behavior, they show several outcomes such as decisional balance (measured by the pros and cons of the target behavior) and confidence. From the earlier stages to the later stages of behavior change, the pros and confidence levels increase while the cons decrease. The most unique feature of the TTM is that for effective behavior change, different change processes should match the different change stages [23]. The TTM has been widely used in health, finance, and other domains [23,24]. However, research on recycling behavior using the TTM is limited. In this study, under the guidelines of this theory and the associated literature, research questions were developed, and a national survey was conducted. We attempted to answer the following research questions:

- What is the status of consumer recycling behavior by behavior change stage?

- What psychological, cognitive, socioeconomic, and environmental factors associated with consumer recycling behavior differ by behavior change stage?

These research questions aim to address a research gap in the literature. Most empirical studies on consumer recycling behavior have applied the theory of planned behavior, in which the factors associated with recycling behavior are identified [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, little research has examined the change stages for recycling behavior. Using the lens of the TTM, we are able to examine the factors associated with the behavior change stages in consumer recycling, contributing to the literature on recycling behavior.

To answer these questions, we test the validity of the TTM regarding behavior change stages in the context of recycling. In addition, we also test whether the TTM’s predictions of the associations between behavior change stages and outcomes (measured using a set of psychological factors) are valid. This study has both theoretical and practical significance. Theoretically, this study examines the factors associated with recycling behaviors, which enriches the literature on sustainable consumer behavior and confirms or disconfirms previous research on the factors associated with recycling behavior in other contexts. The results also test the validity of the theory, the TTM, and contribute to the theory-building in the literature on sustainable consumer behavior. From a public policy perspective, the results provide information for policy makers when they develop and implement environmental management and education programs. The results show the status of recycling behavior by behavior change stage among American consumers. They also show the differences in the psychological, cognitive, socioeconomic, and environmental factors between behavior change stages, which have implications for developing interventions to encourage consumer recycling behavior.

Compared to the previous research, this study has three innovations. First, it is theory-based, namely using the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM). Second, it is a joint project between researchers and practitioners. The university researchers worked with the practitioners in a state environment protection agency and a resource recovery corporation to develop and design this study. With this unique cooperation, the project is theoretically sound and practically meaningful. Third, this study examines the psychological and cognitive factors associated with recycling behavior between behavior change stages. It provides insights on behavioral change processes and has implications for developing interventions to encourage consumers to engage in recycling behavior. Its findings are informative for professionals in waste management and recycling policy and education.

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Statistics on the Behavior Change Stages

Based on the weighted sample, as shown in Table 1, 12.8% of consumers are still at the precontemplation stage in terms of their recycling behavior; 7.6% are in the contemplation stage and are considering recycling in the next three months; and 3.1% of them are in the preparation stage and are considering recycling in the next 30 days. Among the consumers who recycle now, 7.9% are at the action stage, having started recycling fewer than 6 months ago, and 13.2% are at the maintenance stage, having participated in recycling for more than 6 months but fewer than 18 months. Over half of the sample (55.5%) reported that they had recycled for over 18 months, suggesting that recycling is a habit in their daily life.

Table 1.

Recycling behavior by behavior change stages (N = 1321).

2.2. Change Processes by Behavior Change Stage

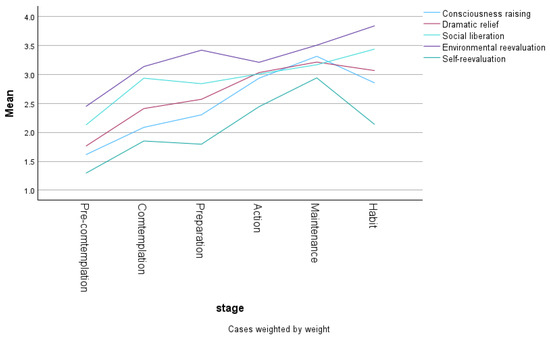

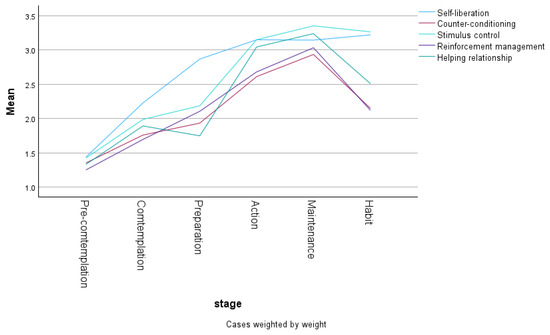

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to test the differences in the behavior change processes by behavior change stage. The results show differences in ten change process scores by the six change stages. For example, for “consciousness-raising” (F(5, 1279) = 7.919, p < 0.001), the post hoc tests showed four distinct groups: pre-contemplation; contemplation and preparation; action and habit; and maintenance. Detailed statistics for the group differences in the other change process scores are presented in Appendix B. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the change processes by change stage. It is interesting to contrast these findings with the theoretical predictions of the TTM. The TTM assumes that the change processes used by consumers who are at different stages are different. The findings supported the TTM’s predictions in certain ways. For example, among the ten change processes, all of the test results were statistically different, suggesting consumers may use these processes differently at various behavior change stages. Figure 1 presents the mean scores of each of the first five change processes by the behavior change stages, and Figure 2 presents the mean scores of each of the last five change processes by the behavior change stages. The patterns are not totally consistent with the predictions of the TTM, but the results are interesting. Two major patterns emerge: some process scores increase from an earlier stage to a later stage continuously, while other process scores reach a peak until the second last stage and then decline. For example, environmental reevaluation (Figure 1) demonstrates the first pattern, with its score continuously increasing from the earliest stage to the latest stage. For reinforcement management (Figure 2), this suggests that its score may increase from the earliest stage to a peak score at the maintenance stage and then decrease. These patterns have implications for developing targeted intervention programs.

Figure 1.

Behavioral change processes by behavioral change stage, Part I.

Figure 2.

Behavioral change processes by behavioral change stage, Part II.

2.3. Psychological Factors by Behavior Change Stage

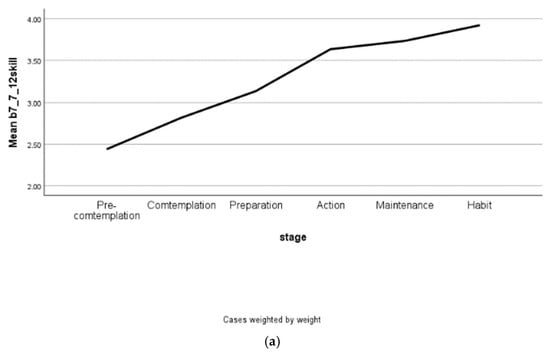

The TTM specifies several outcome variables, such as confidence and decisional balance. Confidence is a factor similar to self-efficacy. In this study, it is called behavioral skill, following previous research [15]. Figure 3a suggests that confidence levels may increase by behavior change stage. The confidence level is lower at earlier stages but higher at later stages, which is consistent with the theoretical prediction. Decisional balance has two components, the pros and cons of the target behavior. The variable used in this study is called perceived cost, which is similar to the concept of cons since its two items have negative connotations regarding recycling behavior (recycling is unnecessary; recycling has few benefits for individuals). The pattern in Figure 3c shows that from the earlier to the later stages, the perceived cost changes from high to low but with some fluctuations, which is partially consistent with the theoretical prediction. This study used two variables to measure the pros of recycling behavior. One is social motivation, which is a concept similar to a subjective norm in the theory of planned behavior [25]. The pattern in Figure 3b suggests that this factor may be positively associated with behavior change stages, implying that social supports are helpful in encouraging consumer recycling behavior. Figure 3d shows the pattern for attitude over the behavior change stages, which shows a broad trend from low to high but with fluctuation, suggesting that one’s attitude may become more positive at later behavior change stages, which is partially consistent with the theoretical prediction. The one-way ANOVA tests showed that all of the psychological factors differed by behavior change stage. For behavioral skill (F(5, 1296) = 3.686, p = 0.003), the post hoc tests identified four distinct groups, in which the first three stages differed from each other and the last three stages formed a group that differed from the other groups. For perceived cost (F(5, 1298) = 4.601, p < 0.001), the post hoc test showed two groups, “habit” and all other stages. For social motivation (F(5, 1297) = 4.184, p < 0.001), the post hoc test showed four groups. Finally, for attitude (F(5, 1291) = 9.425, p < 0.001), the post hoc test showed three groups. See the detailed statistics presented in Appendix B.

Figure 3.

Psychological variables by behavior change stage. (a) Behavioral skill, (b) social motivation, (c) perceived cost, and (d) attitude.

2.4. Cognitive Factors by Behavior Change Stage

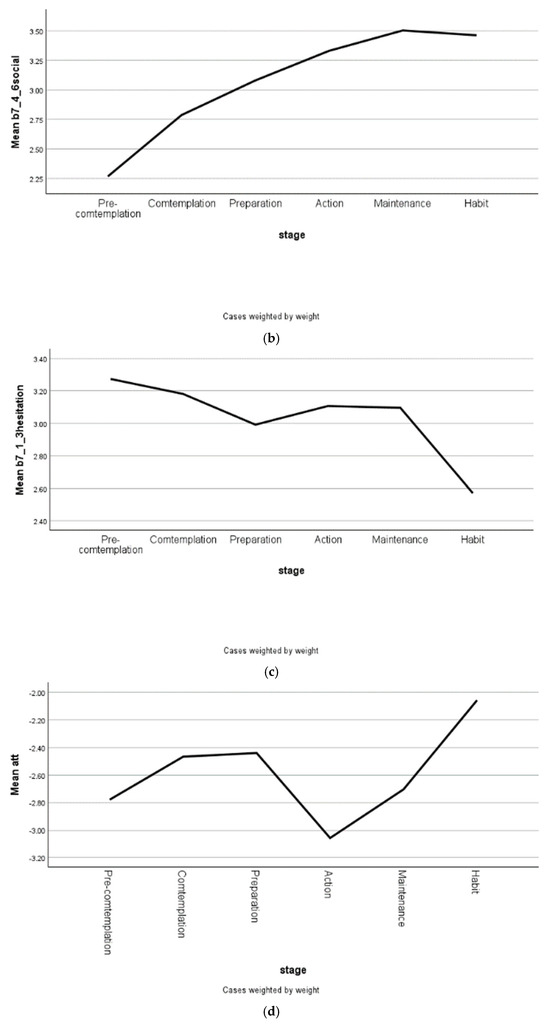

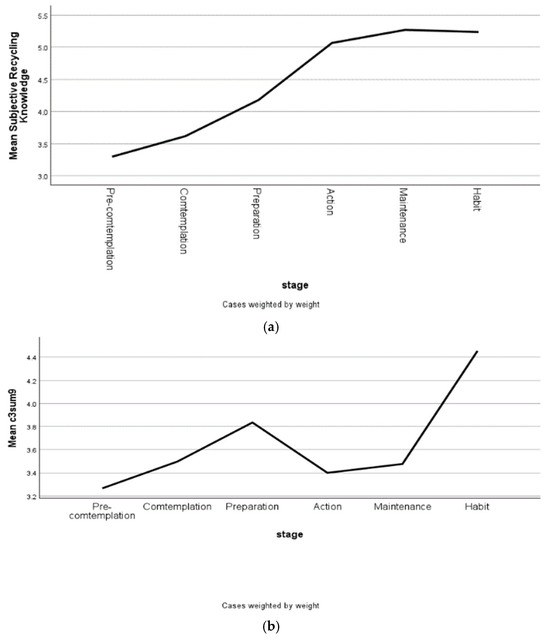

Figure 4a,b show the patterns of subjective and objective recycling knowledge over the behavior change stages. The one-way ANOVA tests showed that there were differences in both the subjective recycling knowledge (F(5, 1285) = 26.925, p < 0.001) and objective recycling knowledge variables (F(5, 1313) = 8.751, p < 0.001). The post hoc tests showed that the scores for subjective knowledge were statistically higher at the last three stages than those at the earlier three stages. For objective knowledge, the score for the last stage “habit” was statistically higher than those for all previous stages except for “preparation.” Both figures show an upward pattern in which the pattern for subjective recycling knowledge demonstrated almost perfect positive correlations, while objective recycling knowledge showed a fluctuating pattern, first from low to high, then to low, and then to high. These findings suggest that subjective knowledge and objective knowledge may play different roles in shaping recycling behavior.

Figure 4.

Recycling knowledge by behavior change stage. (a) Subjective knowledge and (b) objective knowledge.

2.5. Socioeconmic and Environmental Factors by Behavior Change Stages

Table 2 presents the Chi-square test results for the socioeconomic and environmental factors by the behavior change stages. The results show that female respondents were more likely to be at the pre-contemplation stage, while male respondents were more likely to be at the habit stage. Age showed an interesting pattern: both being at the pre-contemplation stage and the habit stage was positively associated with age. In terms of region, respondents in the Midwest and the South were more likely to be at the pre-contemplation stage, while respondents in the Northeast were more likely to be at the habit stage. Income showed a consistent pattern: lower-income respondents were more likely to be at the pre-contemplation stage, and higher-income respondents were more likely to be at the habit stage. Regarding the environmental factors, respondents who reported having a recycling facility in their neighborhood were the least likely to be at the pre-complementation stage and most likely to be at the habit stage, while the respondents who provided the answer “don’t know” to this question reported the opposite answers at these stages. We used distance to a recycling facility to measure convenience, and the results did not show clear patterns. The respondents who lived the shortest distances from a facility were most likely to be at the pre-contemplation stage, while they were the second least likely to be at the habit stage.

Table 2.

Socioeconomic and environmental factors by behavior change stages: Chi-square test results.

3. Discussions, Limitations, and Implications

3.1. Discussions

This study used data collected from the U.S. to describe the status of and the factors associated with behavior change stages under the guidance of the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM). The results show interesting patterns regarding the two research questions asked.

For the first research question, this study identified the behavior change stages in consumer recycling. The results show that most of the consumers (76.5%) engaged in recycling behavior at various behavior change stages, while a minority of consumers (23.5%) were still not engaging in recycling behavior. Among them, 12.8% never considered recycling. It is a challenge to motivate consumers who never consider recycling in the near future.

The second research question asked what factors were associated with the behavior change stages among American consumers. The one-way ANOVA results show that consumer change processes that can be considered change strategies used by consumers to change their behavior are different from the earlier stages to the later stages. Two patterns are shown: one pattern is an upward pattern, from low to high over the behavior change stages, and the other is an upward pattern until the stage before the last stage that then declines. These findings are not consistent with the theoretical predictions of the TTM, in which change processes and change stages are matched in a specific way. Based on the TTM’s predictions, change processes are more effective across certain change stages. For example, consciousness-raising, environmental reevaluation, and dramatic relief are more effective between pre-contemplation and contemplation; self-reevaluation is more effective between contemplation and preparation; self-liberation is more effective between preparation and action; helping relationships, reinforcement management, counter-conditioning, and stimulus control are more effective between action and maintenance; and social liberation is effective for transitioning between all change stages [22]. Our findings do not show these patterns exactly. We did not find other studies that had applied the TTM to examining recycling behavior. We did find a study that had applied the TTM to examining pro-environmental behavior [26], in which the factors were not compared across behavior change stages. One study that applied TTM to financial behavior showed patterns that were not exactly consistent with the TTM’s predictions but were broadly consistent [24]. Many published studies have applied the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to recycling behavior, based on a review [9]. The TPB is an ideal theoretical framework for understanding the factors associated with a target behavior, including recycling behavior [25]. However, it is not designed to examine the various change stages for a target behavior. To understand the process of behavior change, the TTM is an appropriate theoretical framework. Even though the findings are inconsistent with the TTM’s predictions, the unique patterns found in this study are still informative for the development of interventions. The results suggest that for the goal of encouraging consumer recycling behavior, certain change processes may be used for all stages, and others may be effective from the earliest stage to the penultimate stage.

The results of the bivariate analysis also show patterns of outcomes over the behavior change stages. Behavioral skill, also called confidence or self-efficacy by different researchers, is positively associated with the behavior change stages. In addition, perceived cons are negatively associated, and perceived pros are positively associated, with the behavior change stages, in which some patterns are more consistent than others. These findings echo the results of other studies that have used similar factors to predict consumer recycling behavior [20,27].

The results also suggest that recycling knowledge may play a role in encouraging recycling behavior. Generally speaking, subjective knowledge shows an upward pattern across the behavior change stages, and objective knowledge’s pattern moves in a broad upward direction with a fluctuation. These results suggest that subjective knowledge and objective knowledge may play different roles in encouraging recycling behavior. Previous research shows similar patterns for recycling knowledge’s relation to recycling behavior [5,28].

The findings show gender, age, region, and income differences in terms of the behavior change stages. Compared to their counterparts, respondents who are male, older, and living in the Northeast and have a higher income are more likely to be at the habit stage. Also, knowing about the existence of a recycling facility in one’s neighborhood is also important in terms of the behavior change stages. The respondents who report having recycling facilities in their neighborhoods are more likely to be at the habit stage, while respondents who do not know whether neighborhood recycling facilities exist are most likely to be at the pre-contemplation stage. These findings are consistent with previous research that has shown gender, age, and income differences in recycling behavior [29].

3.2. Limitations

Behavior change is a dynamic process in nature, but the data collected here are cross-sectional. This is the major limitation of this study. The results of this study are only suggestive instead of conclusive. The TTM provides a theoretical framework for testing the effectiveness of interventions across behavior change stages. To observe people’s behavior changes across the stages regarding recycling behavior and to test the effectiveness of interventions, longitudinal data are needed. For example, if researchers want to test the effectiveness of self-reevaluation between contemplation and preparation, respondents across the two stages during a given time period need to be identified, and panel data need to be collected to achieve this goal. If the research needs to test the effectiveness of all change processes as potential interventions, a group of respondents needs to be followed for at least 18 months, based on the standard in clinical psychology [22]. Another limitation is the limited measures of the pros of recycling behavior. Potential pros of recycling behavior include environmental concerns, personal values, and financial incentives, besides those used in this study. These topics could be considered in future research when a new survey is designed.

3.3. Implications

These results have theoretical implications for understanding the consumer behavior change stages in recycling better. Even though the TTM-predicted patterns are not found in our findings, it has theoretical foundations that are helpful for developing intervention strategies due to its effectiveness, as verified by many empirical studies in other domains. The TTM suggests that three strategies are effective for transitioning consumers from pre-contemplation to contemplation: consciousness-raising, environmental reevaluation, and dramatic relief. To draw the attention of consumers who are not considering recycling, education programs and public advertisements should focus on the importance of recycling to society and individual wellbeing and make the presentation of information dramatic to impress consumers. If consumers begin to recycle, policy makers could provide them with tools to help them recycle appropriately. Based on the TTM, effective strategies for moving consumers from the action stage to the maintenance stage include helping relationships, reinforcement management, counter-conditioning, and stimulus control. Intervention programs may help consumers to form community groups to support each other in recycling, create recycling facilities in neighborhoods to provide convenience for consumer recycling, provide financial and non-financial incentives for recycling, and provide consumers with detailed instructions on recycling appropriately. These findings are informative for future theory-building on the consumer behavior change processes in recycling.

The findings also have implications for public policies. Enhancing confidence in recycling is important to enhancing consumer recycling behavior since the evidence shows that consumers’ confidence levels are higher at later behavior change stages. Policy makers may mobilize resources to assist consumers who are willing to recycle and inform them promptly that their behaviors have positive impacts on environmental protection and social justice. To encourage consumer confidence in recycling, policy makers may encourage recycling training through various contexts such as schools, workplaces, and communities. Resources may be allocated to informing consumers who are willing to recycle how to appropriately recycle different types of waste. Some consumers with advanced recycling skills may serve as opinion leaders to help other consumers obtain the skills needed to recycle waste appropriately.

The findings also suggest that recycling knowledge, especially subjective recycling knowledge, has an upward pattern over the behavior change stages. The findings imply that recycling education may be helpful for encouraging consumer recycling behavior. Based on these findings, subjective recycling knowledge seems to be more important than objective recycling knowledge in encouraging recycling behavior, which suggests that the purpose of recycling education may be focused on enhancing consumer confidence and basic skills and less on the technical details of recycling. Education programs may be more effective when they are combined with incentive programs. Previous research shows that both incentive and information programs are helpful for encouraging consumers to engage in recycling behavior [30]. Incentive programs (financial vs. non-financial) may have different effects on consumers with different recycling knowledge levels [27]. Recycling programs may be more effective if multiple measures are used together, such as monetary incentives, tax incentives, subsidization, the dissemination of information, awareness campaigns, training, and technical assistance [31]. To enhance consumer knowledge of recycling, these factors should be considered in developing consumer recycling education programs.

Policy makers should beware of the socioeconomic and environmental differences in the behavior change stages and use this information to create effective social programs for encouraging consumer recycling. To make consumers aware of the importance of recycling, efforts should focus on female, younger, and lower-income consumers. To encourage consumers to engage in recycling, information about recycling facilities should be provided to consumers through all forms of communication channels.

4. Method

4.1. Data

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the researchers’ university before the survey was conducted. The survey was presented in Qualtrics (an online survey platform commonly used in the U.S. and other countries) and pre-tested by a sample of faculty and students at a public university in fall 2023. The data collection was conducted from January to March 2024. An online platform, CloudResearch, was used to collect the data. CloudResearch, formerly named TurkPrime, is a crowdsourcing platform that connects researchers with participants who are willing to take part in online surveys. The platform has a large and diverse pool of participants, which makes it ideal for collecting data that are representative of the general population in the U.S. [32].

The data were cleaned, and the sample was selected with the following criteria: (1) the survey duration should be between 5 and 20 min, and (2) the respondents should be 18 or older. The final, clean dataset included 1343 observations. After removing observations with missing values for behavior-change-stage-related variables, the sample size used in the analyses was 1321.

A weight variable was constructed using the inverse of the selection probabilities combined with the post-stratification approach [33]. Based on the design of the survey, the sampling probabilities were determined by sampling strata, defined by region, gender, and age. Each stratum contained at least 30 sample units [34]. For each sampling stratum, the selection probability was calculated by the ratio between the total number of respondents in the stratum and the total number of subjects in the corresponding stratum of the census data. The weight variable was then normalized such that the sum of the weights equaled the total number of respondents.

4.2. Variables

Behavior change stages. The behavior change stage variable was constructed based on three survey questions: (1) Do you recycle (yes or no)? (2) If you do recycle, how long have you been doing it (fewer than 6 months, between 6 and 18 months, or more than 18 months)? (3) If you do not recycle, when do you plan to (within the next 30 days, within the next 3 months, or never)? This new variable had the following attributes: (1) Pre-contemplation: never; (2) contemplation: will do it in the next 3 months; (3) preparation: will do it in the next 30 days; (4) action: have been doing it for fewer than 6 months, (5) maintenance: have been doing it for 6–19 months; and (6) habit: doing it for more than 18 months.

Behavior change processes. Based on the TTM, ten change process variables were included that were measured using scales of 1 (never) to 5 (repeatedly). These process variables were consciousness-raising (actively seeking relevant information); dramatic relief (experiencing negative emotions around undesirable behavior); social liberation (realizing a change in social norms); environmental reevaluation (realizing the impact of behavior changes on one’s environment); self-reevaluation (realizing a new identify after a behavior change); self-liberation (make a firm commitment to change); counter-conditioning (substituting undesirable behavior with desirable behavior); stimulus control (adding cues to encourage desirable behavior); reinforcement management (rewarding desirable behavior); and helping relationships (using social supports for behavior change). Their meanings can be found in previous research [23,24]. These change processes can be viewed as strategies that consumers use during a behavior change.

Psychological factors. The TTM also specified several outcome variables, such as perceived cons, perceived pros, and confidence. We used two variables as a proxy for perceived pros: social motivation and attitude. Perceived cons were measured using a variable labeled perceived cost. Confidence was measured using a variable called behavioral skill. All of these psychological variables were evaluated on 5-point Likert scales, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Exploratory factor analyses were employed, and these variables were finalized based on their loadings. Detailed results on the factor analyses are presented in Appendix A.

Cognitive factors. Two variables were used to measure cognitive factors: objective recycling knowledge and subjective recycling knowledge. Objective recycling knowledge was the sum of correct answers to nine true/false questions, which were used in the state survey regarding recycling behavior. Subjective recycling knowledge was assessed using a question asking the respondents what their self-assessed level of recycling knowledge was, ranging from low (1) to high (10).

Socioeconomic and environmental factors. Four variables were used for socioeconomic factors: gender (male vs. female), age (aged 18–35, 36–64, and 65 or older), region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and household income, with three groups. Two environmental were used: whether there was a recycling facility in the neighborhood (yes, no, don’t know) and distance to a recycling facility, with four groups.

4.3. Analyses

A one-way ANOVA was used to examine differences in the behavior change stages in terms of the variables related to the consumers’ characteristics. The figures are used to demonstrate the patterns in the psychological and knowledge factors across various behavior change stages. Tables of the one-way ANOVA results showing the specific group differences are presented in Appendix B. Chi-square tests were used to examine the socioeconomic and environmental factor differences by behavior change stage. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29.

5. Conclusions

This study identified the behavior change stages in recycling behavior among American consumers based on a national survey. Its findings suggest that over half of American consumers indicate that recycling is a habit, but a small portion (about one out of eight) of American consumers still never consider recycling. The findings also show group differences in psychological, cognitive, socioeconomic, and environmental factors by behavior change stage. These findings could be used to develop intervention strategies encouraging consumer recycling. The unique contributions of this study are to apply behavior change theory to recycling and identify the factors associated with consumers at various stages of behavior change. This study identified the status of the behavioral change stages regarding recycling and identified psychological and cognitive factors associated with each specific behavior change stage using national data collected in the U.S. This approach may be utilized in other countries in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.X.; methodology, J.J.X.; formal analysis, J.J.X.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J.X.; writing—review and editing, J.J.X. and F.X.; funding acquisition, J.J.X. and F.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data collection of this project was funded by U.S. NOAA # NA22NOS4690221.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this article is available from the authors upon requests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Results of the Factor Analyses on Psychological Factors

Table A1 presents the factor loadings for the consumer perception variables. Based on the results, five factors are identified, which are personal motivation (B7_1 to B7_3), social motivation (B7_4 to B7_6), behavioral skills (B7_7 to B7_12), ascription of responsibility (B7_13 and B7_14), and attitude (B7_16 and B7_18). Most of these items are loaded based on the conceptual definitions from the literature, except for the ascription of responsibility, in which B7_12 is loaded on behavioral skills instead of ascription to responsibility. In addition, two variables (B7_15 and B7_17) could not be loaded onto one factor and were removed from the analyses. These variables were used to create factor scores by averaging the scores, which were used in later analyses. In this manuscript, ascription of responsibility is not used in the later analyses.

Table A1.

Factor analysis results for consumer perceptions on recycling.

Table A1.

Factor analysis results for consumer perceptions on recycling.

| Rotated Component Matrix a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| B7_8. I have plenty of opportunities to recycle. | 0.824 | 0.184 | 0.135 | −0.114 | −0.028 |

| B7_7. I can recycle easily. | 0.805 | 0.198 | 0.090 | −0.191 | −0.050 |

| B7_11. I know when and where I can recycle materials/products. | 0.801 | 0.247 | 0.104 | −0.090 | −0.043 |

| B7_9. I have been provided satisfactory resources to recycle properly. | 0.799 | 0.244 | 0.054 | 0130 | 0.091 |

| B7_12. I am responsible for recycling properly. | 0.732 | 0.202 | 0.236 | −0.053 | −0.082 |

| B7_10. I know which materials/products are recyclable. | 0.634 | 0.161 | 0.245 | −0.094 | −0.129 |

| B7_6. My friends/colleagues think I should recycle. | 0.318 | 0.859 | 0.156 | −0.037 | −0.020 |

| B7_4. Most people who are important to me think I should recycle. | 0.290 | 0.842 | 0.077 | 0.024 | −0.031 |

| B7_5. My household/family members think I should recycle. | 0.359 | 0.824 | 0.150 | −0.045 | −0.090 |

| B7_13. Government should be responsible for recycling properly. | 0.121 | 0.036 | 0.855 | 0.030 | 0.077 |

| B7_14. Producers should be responsible for recycling properly. | 0.176 | 0.151 | 0.848 | −0.026 | 0.037 |

| B7_17. Recycling is benefiting society. | 0.434 | 0.166 | 0.524 | 0.012 | −0.419 |

| B7_15. Recycling is a desirable behavior. | 0.446 | 0.221 | 0.513 | −0.047 | −0.234 |

| B7_1. Finding room to store recyclable materials is a problem. | −0.189 | 0.014 | 0.035 | 0.804 | 0.003 |

| B7_3. Storing recycling materials at home is unsanitary. | −0.090 | −0.071 | −0.011 | 0.785 | 0.155 |

| B7_2. The problem with recycling is finding time to do it. | −0.108 | 0.012 | −0.037 | 0.773 | 0.212 |

| B7_16. Recycling is not necessary. | −0.055 | −0.041 | −0.061 | 0.185 | 0.857 |

| B7_18. Recycling has little benefit for individuals. | −0.027 | −0.031 | 0.066 | 0.167 | 0.854 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization. a. Rotation converged in 6 iterations.

Appendix B. Homogeneous Subsets Based on the One-Way ANOVA

The following tables demonstrate the results of the post hoc tests (Tukey’s HSD) in the one-way ANOVA specifying the group differences by the behavior change stages at a significance level of 5%. For all of the results below, the sample is weighted, and the means for groups in homogeneous subsets are displayed. The relevant line charts are displayed in the main manuscript.

- Change Processes

| 1.1. Consciousness raising | ||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 164 | 1.61 | |||

| Contemplation | 100 | 2.11 | ||||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.30 | ||||

| Habit | 722 | 2.85 | ||||

| Action | 100 | 2.89 | ||||

| Maintenance | 164 | 3.32 | ||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.766 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 1.2. Dramatic relief | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 164 | 1.77 | ||

| Contemplation | 100 | 2.42 | |||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.57 | |||

| Action | 98 | 3.03 | |||

| Habit | 721 | 3.06 | |||

| Maintenance | 164 | 3.21 | |||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.933 | 0.867 | ||

| 1.3. Social liberation | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 165 | 2.12 | ||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.84 | |||

| Contemplation | 100 | 2.93 | |||

| Action | 98 | 3.00 | |||

| Maintenance | 164 | 3.14 | 3.14 | ||

| Habit | 720 | 3.44 | |||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.317 | 0.373 | ||

| 1.4. Environmental reevaluation | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 165 | 2.44 | ||

| Contemplation | 100 | 3.13 | |||

| Action | 98 | 3.20 | |||

| Preparation | 41 | 3.42 | 3.42 | ||

| Maintenance | 161 | 3.50 | 3.50 | ||

| Habit | 717 | 3.83 | |||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.159 | 0.078 | ||

| 1.5. Self-reevaluation | ||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 164 | 1.29 | |||

| Preparation | 41 | 1.79 | ||||

| Contemplation | 97 | 1.85 | ||||

| Habit | 718 | 2.15 | 2.15 | |||

| Action | 98 | 2.44 | ||||

| Maintenance | 164 | 2.92 | ||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.239 | 0.453 | 1.000 | ||

| 1.6. Self-liberation | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 165 | 1.44 | ||

| Contemplation | 96 | 2.23 | |||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.87 | |||

| Maintenance | 164 | 3.14 | |||

| Action | 96 | 3.15 | |||

| Habit | 720 | 3.22 | |||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.303 | ||

| 1.7 Counter-conditioning | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 165 | 1.35 | ||

| Contemplation | 100 | 1.76 | 1.76 | ||

| Preparation | 41 | 1.94 | |||

| Habit | 719 | 2.16 | |||

| Action | 98 | 2.65 | |||

| Maintenance | 164 | 2.87 | |||

| Sig. | 0.103 | 0.115 | 0.743 | ||

| 1.8 Stimulus control | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 164 | 1.43 | ||

| Contemplation | 100 | 1.98 | |||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.19 | |||

| Action | 98 | 3.17 | |||

| Habit | 721 | 3.26 | |||

| Maintenance | 162 | 3.34 | |||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.757 | 0.869 | ||

| 1.9 Reinforcement management | |||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 165 | 1.25 | ||

| Contemplation | 100 | 1.67 | 1.67 | ||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.11 | |||

| Habit | 722 | 2.13 | |||

| Action | 98 | 2.74 | |||

| Maintenance | 160 | 3.00 | |||

| Sig. | 0.101 | 0.054 | 0.599 | ||

| 1.10. Helping relationships | ||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 165 | 1.33 | |||

| Preparation | 41 | 1.75 | 1.75 | |||

| Contemplation | 100 | 1.86 | ||||

| Habit | 719 | 2.51 | ||||

| Action | 98 | 3.04 | ||||

| Maintenance | 163 | 3.20 | ||||

| Sig. | 0.109 | 0.982 | 1.000 | 0.931 | ||

- 2.

- Psychological Factors

| 2.1. Behavioral skill | ||||||||||||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 168 | 2.4402 | |||||||||||||

| Contemplation | 100 | 2.8160 | ||||||||||||||

| Preparation | 41 | 3.1347 | ||||||||||||||

| Action | 99 | 3.6350 | ||||||||||||||

| Maintenance | 171 | 3.7348 | ||||||||||||||

| Habit | 724 | 3.9213 | ||||||||||||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.071 | ||||||||||||

| 2.2. Social motivation | ||||||||||||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 168 | 2.2686 | |||||||||||||

| Contemplation | 100 | 2.7882 | ||||||||||||||

| Preparation | 41 | 3.0809 | 3.0809 | |||||||||||||

| Action | 99 | 3.3317 | 3.3317 | |||||||||||||

| Habit | 724 | 3.4635 | ||||||||||||||

| Maintenance | 171 | 3.5044 | ||||||||||||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.214 | 0.383 | 0.768 | ||||||||||||

| 2.3 Perceived cost | ||||||||||||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Tukey’s HSD | Habit | 724 | 2.5715 | |||||||||||||

| Preparation | 41 | 2.9919 | ||||||||||||||

| Maintenance | 171 | 3.0960 | ||||||||||||||

| Action | 101 | 3.1068 | ||||||||||||||

| Contemplation | 100 | 3.1813 | ||||||||||||||

| Pre-contemplation | 168 | 3.2734 | ||||||||||||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 0.206 | ||||||||||||||

| 2.4 Attitude | ||||||||||||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Tukey’s HSD | Action | 99 | −3.0570 | |||||||||||||

| Pre-contemplation | 167 | −2.7790 | −2.7790 | |||||||||||||

| Maintenance | 171 | −2.7043 | −2.7043 | |||||||||||||

| Contemplation | 100 | −2.4676 | ||||||||||||||

| Preparation | 41 | −2.4411 | −2.4411 | |||||||||||||

| Habit | 720 | −2.0587 | ||||||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.135 | 0.170 | 0.081 | |||||||||||||

- 3.

- Cognitive Factors

| 3.1 Subjective Recycling Knowledge | |||||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 168 | 3.30 | ||||||

| Contemplation | 100 | 3.62 | 3.62 | ||||||

| Preparation | 41 | 4.18 | |||||||

| Action | 100 | 5.07 | |||||||

| Habit | 725 | 5.24 | |||||||

| Maintenance | 166 | 5.27 | |||||||

| Sig. | 0.631 | 0.069 | 0.922 | ||||||

| 3.2 Objective Recycling Knowledge | |||||||||

| Stage | N | Subset | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Tukey’s HSD | Pre-contemplation | 169 | 3.27 | ||||||

| Action | 104 | 3.40 | |||||||

| Maintenance | 174 | 3.48 | |||||||

| Contemplation | 100 | 3.50 | |||||||

| Preparation | 41 | 3.83 | 3.83 | ||||||

| Habit | 733 | 4.45 | |||||||

| Sig. | 0.355 | 0.261 | |||||||

References

- Trudel, R. Sustainable consumer behavior. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J. Consumer capability and sustainable consumer behavior: Applying the transtheoretical model of behavior change (TTM). Yamaguchi J. Econ. Bus. Adm. Laws 2022, 70, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.J. Life satisfaction and sustainable consumption. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, 2nd ed.; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Li, H. Sustainable consumption and life satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 323–329. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-010-9746-9 (accessed on 27 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.L.; Steg, L.; Van Der Werff, E.; Ünal, A.B. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, J.; Curtis, J.; Smith, L. Interdisciplinary, systematic review found influences on household recycling behaviour are many and multifaceted, requiring a multi-level approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 18, 200152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulwani, P.R.; Kumar, D.; Goyal, P. A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis of recycling behavior. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIRRC. A Guide to Resource Recovery; RI Resource Recovery Corporation: Johnston, RI, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.rirrc.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/A%20Guide%20to%20Resource%20Recovery_2022_0.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Arı, E.; Yılmaz, V. A proposed structural model for housewives’ recycling behavior: A case study from Turkey. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 129, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fano, D.; Schena, R.; Russo, A. Empowering plastic recycling: Empirical investigation on the influence of social media on consumer behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Salem, N.; Al-Hawari, M.A. Predictors of recycling behavior: The role of self-conscious emotions. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Khan, K.; Waris, I.; Zainab, B. Factors influencing the sustainable consumer behavior concerning the recycling of plastic waste. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2022, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J.Z. Predicting recycling behavior in New York state: An integrated model. Environ. Manag. 2022, 70, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šmaguc, T.; Kuštelega, M.; Kuštelega, M. The determinants of individual’s recycling behavior with an investigation into the possibility of expanding the deposit refund system in glass waste management in Croatia. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2023, 28, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, W.F. Applying the theory of planned behavior to recycling behavior in South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoo, A.C.; Tee, S.J.; Huam, H.T.; Mas’od, A. Determinants of recycling behavior in higher education institution. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1660–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Tseng, M.-L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Intention in use recyclable express packaging in consumers’ behavior: An empirical study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Rafiee, P.; Xia, F.; Wu, J. Consumer sustainability: Is knowledge linked to behavior in recycling? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, V.; Arı, E. Investigation of attitudes and behaviors towards recycling with theory planned behavior. J. Econ. Cult. Soc. 2022, 66, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Redding, C.A.; Evers, K.E. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Glanz, K., Lewis, F.M., Rimer, B.K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C.; Norcross, J.C. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Newman, B.M.; Prochaska, J.M.; Leon, B.; Bassett, R.; Johnson, J.L. Applying the transtheoretical model of change to consumer debt behavior. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2004, 15, 89–100. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/56698662.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulick, P.; Girish, B.; Chandradeo, B.; Devi Beeharry, Y. Investigating pro-environmental behaviour among students: Towards an integrated framework based on the transtheoretical model of behaviour change. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 6751–6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Motivating recycling behavior—Which incentives work, and why? Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.R.; Bui, D.P.; Chau, H.; Wang, K.; Trevisi, L.M.; Jerdy AC, R.; Lobban, L.; Crossley, S.; Feltz, A. Development of an objective measure of knowledge of plastic recycling: The outcomes of plastic recycling knowledge scale (OPRKS). J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 91, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidou, A.; Ioannou, K.; Tsantopoulos, G.; Arabatzis, G. Citizens’ attitudes and practices towards waste reduction, separation, and recycling: A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Consumer recycling: Role of incentives, information, and social class. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2007, 6, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttibak, S.; Nitivattananon, V. Assessment of factors influencing the performance of solid waste recycling programs. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 53, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Rosenzweig, C.; Moss, A.J.; Robinson, J.; Litman, L. Online panels in social science research: Expanding sampling methods beyond Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 2022–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.; Smith TM, F. Post stratification. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1979, 142, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, S. Sampling: Design and Analysis; Duxbury Press: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).