Understanding Demographic and Behavioral Determinants of Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction: Behavior, Support, and Price Sensitivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

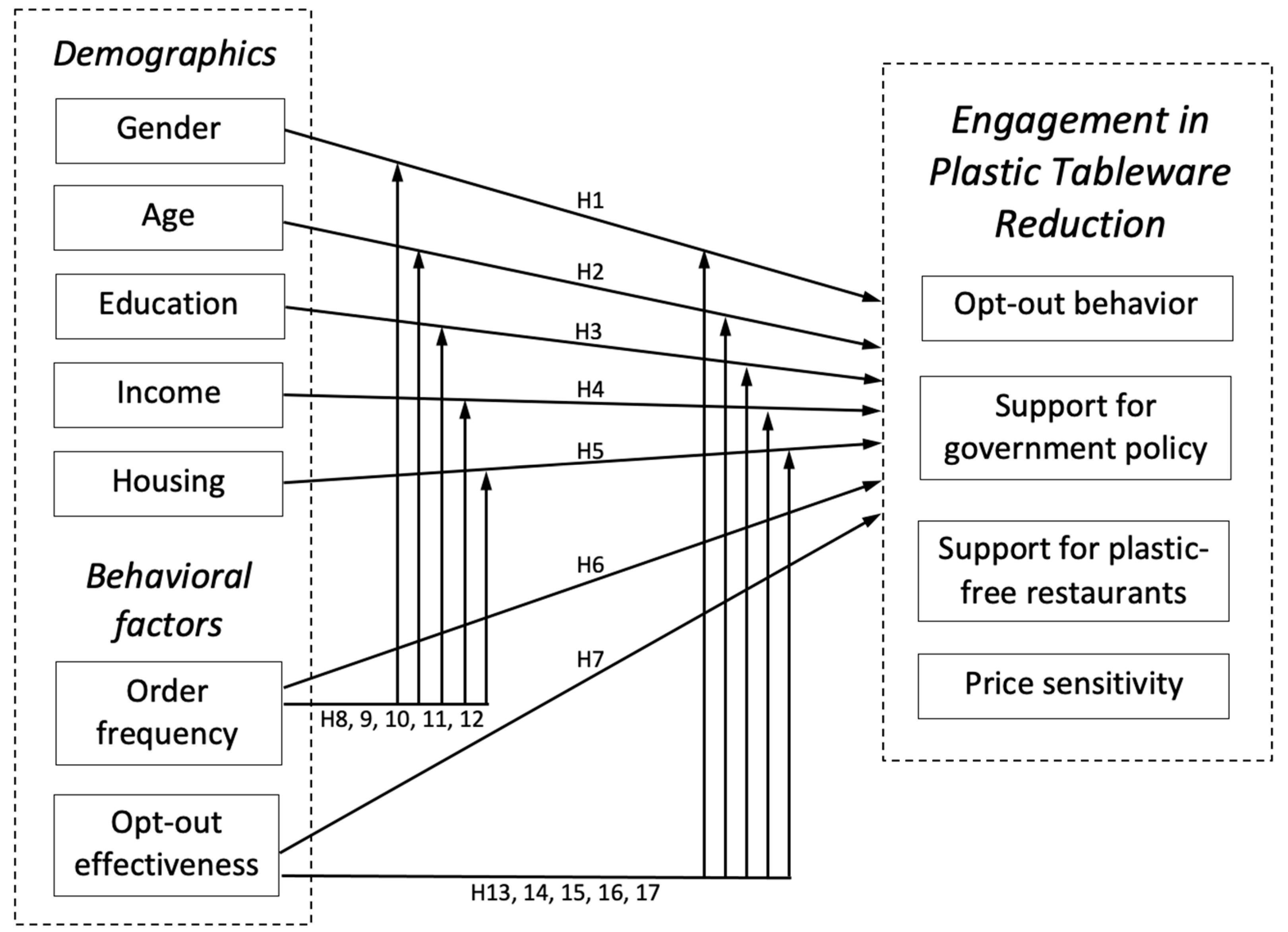

- Do demographic factors (i.e., age, gender, income, education, housing type) influence consumer engagement in plastic tableware reduction?

- Do behavioral factors (i.e., order frequency, opt-out effectiveness) influence consumer engagement in plastic tableware reduction?

- Do behavioral factors (i.e., order frequency, opt-out effectiveness) moderate the relationship between demographics and engagement in plastic tableware reduction?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction

- Plastic tableware opt-out behavior, referring to the active decision to refuse single-use plastic tableware when ordering food.

- Support for government policy, reflecting individuals’ attitudes toward regulations restricting or banning disposable plastic tableware [15].

- Support for plastic-free restaurants, indicating consumer preference for restaurants and food vendors that voluntarily eliminate plastic tableware from their orders [21].

- Price sensitivity, capturing the extent to which individuals are financially motivated to support plastic-free takeaways [22].

2.2. Demographic Factors Influencing Plastic Tableware Reduction Engagement

- H1(a; b; c; d; e): Gender has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H2(a; b; c; d; e): Age has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H3(a; b; c; d; e): Educational has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H4(a; b; c; d; e): Income has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H5(a; b; c; d; e): Housing type has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

2.3. Behavioral Factors Influencing Plastic Tableware Reduction Engagement

- H6(a; b; c; d; e): Order frequency has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H7(a; b; c; d; e): Opt-out effectiveness has a significant effect on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

2.4. Moderating Effects of Order Frequency and Opt-Out Effectiveness

- H8(a; b; c; d; e): Order frequency moderates the effect of gender on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H9(a; b; c; d; e): Order frequency moderates the effect of age on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H10(a; b; c; d; e): Order frequency moderates the effect of education on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H11(a; b; c; d; e): Order frequency moderates the effect of income on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H12(a; b; c; d; e): Order frequency moderates the effect of housing type on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H13(a; b; c; d; e): Opt-out effectiveness moderates the effect of gender on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H14(a; b; c; d; e): Opt-out effectiveness moderates the effect of age on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H15(a; b; c; d; e): Opt-out effectiveness moderates the effect of education on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H16(a; b; c; d; e): Opt-out effectiveness moderates the effect of income on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

- H17(a; b; c; d; e): Opt-out effectiveness moderates the effect of housing type on (a/overall engagement in plastic tableware reduction; b/opt-out behavior; c/support for government plastic opt-out policy; d/support for plastic-free restaurants; e/price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways).

2.5. Theoretical Framework of This Study

3. Results

3.1. Profile of the Respondents

3.2. ANOVA

3.3. Welch’s MANOVA

3.3.1. Influences of Demographic Variables on Plastic Tableware Reduction Engagement

3.3.2. Influences of Interactions on Plastic Tableware Reduction Engagement

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effects of Demographic Determinants on the Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction

4.1.1. Overall Engagement

4.1.2. Four Dimensions of Engagement

4.2. Implications for Theory and Policy

4.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Methodology

5.1. Instruments

- Plastic tableware opt-out behavior: “How often do you choose to opt out of plastic tableware when ordering takeaway or delivery foods?” (a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always)).

- Support for government policy: “To what extent do you agree with the statement: ‘I support the government policy prohibiting restaurants from providing disposable plastic tableware for free.’” (a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree)).

- Support for plastic-free restaurants: “To what extent do you agree with the statement: ‘I prefer to order takeaway or delivery foods from restaurants that have adopted plastic-free tableware.’” (a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree)).

- Price sensitivity of plastic-free takeaways: “What is the minimum discount that would encourage you to choose plastic-free takeaway or delivery?” (open-ended response indicating the amount of money).

- Order frequency: “On average, how many times per week do you order takeaway or delivery food?” (open-ended response; respondents ordering ≤ 1 time per week were classified as infrequent consumers, while those ordering ≥ 1 time per week were classified as frequent consumers).

- Opt-out effectiveness: “When you opt out of plastic tableware, how effective is it?” (ineffective/effective).

- Gender (male/female).

- Age (15–24/24–34/35–44/45 or older).

- Education level (secondary or below/post-secondary diploma or certificate/college, university, or post-graduate).

- Monthly income (less than HKD 9999/HKD 10,000–19,999/HKD 20,000–29,999/HKD 30,000 or more).

- Housing type (public housing/private housing and others).

5.2. Data Collection and Sample

5.3. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Independent Variable | Wilks’ Lambda | F | Prob. | Partial η2 | Non- Centrality Parameter | Observed Power | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.985 | 1.109 | 0.352 | 0.015 | 4.438 | 0.348 | Reject H1a |

| Age | 0.925 | 1.982 | 0.023 * | 0.026 | 20.942 | 0.879 | Accept H2a |

| Educational level | 0.951 | 1.891 | 0.059 | 0.025 | 15.129 | 0.797 | Reject H3a |

| Monthly income | 0.966 | 0.874 | 0.574 | 0.012 | 9.240 | 0.460 | Reject H4a |

| Housing type | 0.991 | 0.643 | 0.632 | 0.009 | 2.571 | 0.209 | Reject H5a |

| Order frequency | 0.992 | 0.602 | 0.662 | 0.008 | 2.406 | 0.198 | Reject H6a |

| Opt-out effectiveness | 0.969 | 2.357 | 0.054 | 0.031 | 9.426 | 0.679 | Reject H7a |

| Gender × order frequency | 0.981 | 1.451 | 0.217 | 0.019 | 5.803 | 0.449 | Reject H8a |

| Age × order frequency | 0.910 | 2.394 | 0.005 ** | 0.031 | 25.283 | 0.941 | Accept H9a |

| Educational level × order frequency | 0.977 | 0.882 | 0.532 | 0.012 | 7.053 | 0.415 | Reject H10a |

| Monthly income × order frequency | 0.946 | 1.411 | 0.155 | 0.018 | 14.916 | 0.714 | Reject H11a |

| Housing type × order frequency | 0.986 | 1.029 | 0.392 | 0.014 | 4.118 | 0.324 | Reject H12a |

| Gender × opt-out effectiveness | 0.988 | 0.871 | 0.482 | 0.012 | 3.485 | 0.277 | Reject H13a |

| Age × opt-out effectiveness | 0.894 | 2.848 | 0.001 ** | 0.037 | 30.066 | 0.975 | Accept H14a |

| Educational level × opt-out effectiveness | 0.946 | 2.114 | 0.033 * | 0.028 | 16.915 | 0.848 | Accept H15a |

| Monthly income × opt-out effectiveness | 0.951 | 1.278 | 0.226 | 0.017 | 13.506 | 0.659 | Reject H16a |

| Housing type × opt-out effectiveness | 0.012 | 0.879 | 0.477 | 0.012 | 3.516 | 0.279 | Reject H17a |

Appendix B

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | F | Prob. | Partial η2 | Non- Centrality Parameter | Observed Power | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Opt-out behavior | 1.703 | 0.193 | 0.006 | 1.703 | 0.255 | Reject H1b |

| Support for government policy | 0.123 | 0.726 | 0.000 | 0.123 | 0.064 | Reject H1c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 1.895 | 0.170 | 0.006 | 1.895 | 0.279 | Reject H1d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.822 | 0.365 | 0.003 | 0.822 | 0.148 | Reject H1e | |

| Age | Opt-out behavior | 2.439 | 0.065 | 0.024 | 7.317 | 0.605 | Reject H2b |

| Support for government policy | 2.014 | 0.112 | 0.020 | 6.041 | 0.515 | Reject H2c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 2.721 | 0.045 * | 0.026 | 8.162 | 0.658 | Accept H2d | |

| Price sensitivity | 1.337 | 0.263 | 0.013 | 4.010 | 0.355 | Reject H2e | |

| Educational level | Opt-out behavior | 6.650 | 0.001 ** | 0.042 | 13.300 | 0.912 | Accept H3b |

| Support for government policy | 0.983 | 0.375 | 0.006 | 1.966 | 0.220 | Reject H3c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 1.603 | 0.203 | 0.011 | 3.206 | 0.338 | Reject H3d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.276 | 0.759 | 0.002 | 0.553 | 0.094 | Reject H3e | |

| Monthly income | Opt-out behavior | 0.743 | 0.527 | 0.007 | 2.230 | 0.209 | Reject H4b |

| Support for government policy | 0.279 | 0.840 | 0.003 | 0.838 | 0.103 | Reject H4c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 0.667 | 0.573 | 0.007 | 2.000 | 0.190 | Reject H4d | |

| Price sensitivity | 1.099 | 0.350 | 0.011 | 3.296 | 0.296 | Reject H4e | |

| Housing type | Opt-out behavior | 1.778 | 0.183 | 0.006 | 1.778 | 0.265 | Reject H5b |

| Support for government policy | 0.002 | 0.966 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.050 | Reject H5c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 0.406 | 0.524 | 0.001 | 0.406 | 0.097 | Reject H5d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.192 | 0.661 | 0.001 | 0.192 | 0.072 | Reject H5e | |

| Order frequency | Opt-out behavior | 0.334 | 0.564 | 0.001 | 0.334 | 0.089 | Reject H6b |

| Support for government policy | 2.270 | 0.133 | 0.007 | 2.270 | 0.324 | Reject H6c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 0.988 | 0.321 | 0.003 | 0.988 | 0.168 | Reject H6d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.337 | 0.562 | 0.001 | 0.337 | 0.089 | Reject H6e | |

| Opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | 3.685 | 0.056 | 0.012 | 3.685 | 0.482 | Reject H7b |

| Support for government policy | 0.016 | 0.900 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.052 | Reject H7c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 2.575 | 0.110 | 0.008 | 2.575 | 0.360 | Reject H7d | |

| Price sensitivity | 4.712 | 0.031 * | 0.015 | 4.712 | 0.581 | Accept H7e | |

| Gender × order frequency | Opt-out behavior | 1.777 | 0.183 | 0.006 | 1.777 | 0.265 | Reject H8b |

| Support for government policy | 0.008 | 0.928 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.051 | Reject H8c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 0.049 | 0.825 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.056 | Reject H8d | |

| Price sensitivity | 2.568 | 0.110 | 0.008 | 2.568 | 0.359 | Reject H8e | |

| Age × order frequency | Opt-out behavior | 4.380 | 0.005 ** | 0.042 | 13.140 | 0.870 | Accept H9b |

| Support for government policy | 2.185 | 0.090 | 0.021 | 6.554 | 0.553 | Reject H9c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 5.122 | 0.002 ** | 0.048 | 15.367 | 0.920 | Accept H9d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.340 | 0.797 | 0.003 | 1.019 | 0.116 | Reject H9e | |

| Educational level × order frequency | Opt-out behavior | 2.171 | 0.116 | 0.014 | 4.342 | 0.443 | Reject H10b |

| Support for government policy | 0.605 | 0.547 | 0.004 | 1.210 | 0.151 | Reject H10c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 1.459 | 0.234 | 0.010 | 2.918 | 0.311 | Reject H10d | |

| Price sensitivity | 1.017 | 0.363 | 0.007 | 2.034 | 0.227 | Reject H10e | |

| Monthly income × order frequency | Opt-out behavior | 1.047 | 0.372 | 0.010 | 3.141 | 0.283 | Reject H11b |

| Support for government policy | 1.691 | 0.169 | 0.017 | 5.074 | 0.441 | Reject H11c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 3.133 | 0.026 * | 0.030 | 9.398 | 0.726 | Accept H11d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.812 | 0.488 | 0.008 | 2.435 | 0.225 | Reject H11e | |

| Housing type × order frequency | Opt-out behavior | 0.396 | 0.530 | 0.001 | 0.396 | 0.096 | Reject H12b |

| Support for government policy | 0.085 | 0.771 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.060 | Reject H12c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 3.069 | 0.081 | 0.010 | 3.069 | 0.416 | Reject H12d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.125 | 0.724 | 0.000 | 0.125 | 0.064 | Reject H12e | |

| Gender × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | 0.805 | 0.370 | 0.003 | 0.805 | 0.145 | Reject H13b |

| Support for government policy | 0.170 | 0.681 | 0.001 | 0.170 | 0.070 | Reject H13c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 0.642 | 0.424 | 0.002 | 0.642 | 0.126 | Reject H13d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.937 | 0.334 | 0.003 | 0.937 | 0.162 | Reject H13e | |

| Age × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | 5.031 | 0.002 ** | 0.048 | 15.092 | 0.915 | Accept H14b |

| Support for government policy | 0.173 | 0.914 | 0.002 | 0.520 | 0.082 | Reject H14c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 2.605 | 0.052 | 0.025 | 7.816 | 0.636 | Reject H14d | |

| Price sensitivity | 3.742 | 0.012 * | 0.036 | 11.227 | 0.807 | Accept H14e | |

| Educational level × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | 3.912 | 0.021 * | 0.025 | 7.824 | 0.703 | Accept H15b |

| Support for government policy | 0.358 | 0.699 | 0.002 | 0.716 | 0.107 | Reject H15c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 2.827 | 0.061 | 0.018 | 5.653 | 0.553 | Reject H15d | |

| Price sensitivity | 1.273 | 0.281 | 0.008 | 2.547 | 0.276 | Reject H15e | |

| Monthly income × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | 0.852 | 0.466 | 0.008 | 2.557 | 0.235 | Reject H16b |

| Support for government policy | 1.979 | 0.117 | 0.019 | 5.937 | 0.508 | Reject H16c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 1.696 | 0.168 | 0.017 | 5.088 | 0.442 | Reject H16d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.647 | 0.585 | 0.006 | 1.941 | 0.185 | Reject H16e | |

| Housing type × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | 2.590 | 0.109 | 0.009 | 2.590 | 0.361 | Reject H17b |

| Support for government policy | 2.239 | 0.136 | 0.007 | 2.239 | 0.320 | Reject H17c | |

| Support for plastic-free restaurants | 1.197 | 0.275 | 0.004 | 1.197 | 0.193 | Reject H17d | |

| Price sensitivity | 0.054 | 0.816 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.056 | Reject H17e |

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plastic Oceans International. The Facts. 2022. Available online: https://www.plasticoceans.org/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoni, M.D.; Winkenbach, M. Crowdsourced on-demand food delivery: An order batching and assignment algorithm. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 149, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Single-Use Plastics Directive: New Rules to Reduce Marine Litter. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_18_3927 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Xanthos, D.; Walker, T.R. International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordic Council of Ministers. Economic Policy Instruments for Plastic Waste: A Review with Nordic Perspectives (TemaNord 2014:569). Nordic Council of Ministers. 2015. Available online: https://www.norden.org/en/publication/economic-policy-instruments-plastic-waste (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Environmental Protection Department Regulation of Disposable Plastic Tableware. 2021. Available online: https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/sites/default/files/epd/english/environmentinhk/waste/pub_consult/files/tableware-con-doc-en.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Environmental Campaign Committee. “Plastic-Free Takeaway, Use Reusable Tableware” Campaign. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecc.org.hk/en/publicity/plastic-free-takeaway.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Verplanken, B.; Whitmarsh, L. Habit and climate change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Schee, B.A.; Peltier, J.; Dahl, A.J. Antecedent consumer factors, consequential branding outcomes and measures of online consumer engagement: Current research and future directions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2020, 14, 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, R.; Lee, M.; Chen, J. When will consumers be ready? A psychological perspective on consumer engagement in social media brand communities. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk, G.; Dumludag, D. The relationship between consumption of single-use plastic bags, environmental awareness, and socio-demographic factors. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2022, 24, 1494–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Why are energy policies acceptable and effective? Environ. Behavior. 2006, 38, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecha, J.E.; Nikolaev, A.; Walteros, J.L.; Zhu, Z. Scientists wanted? A literature review on incentive programs that promote pro-environmental consumer behavior: Energy, waste, and water. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Gunarathne, N.; Gaskin, J.; Ong, T.S.; Ali, M. Environmental corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior: The effect of green shared vision and personal ties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, M.; Voight, A.; Renshaw, T.L.; Eklund, K. School climate, family structure, and academic achievement: A study of moderation effects. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2015, 30, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to shift consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.B.; Sheng, G.H.; She, S.X.; Xu, J.Q. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.; Klintman, M. Eco-Standards, Product Labelling and Green Consumerism; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behavior: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebreo, A.; Vining, J. How similar are recycling and waste reduction? Future orientation and reasons for reducing waste as predictors of self-reported behavior. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Giorgi, S.; Sharp, V.; Strange, K.; Wilson, D.C.; Blakey, N. Household waste prevention—A review of evidence. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. New ways of thinking about environmentalism: Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Modi, A.; Paul, J. Pro-environmental behavior and socio-demographic factors in an emerging market. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 6, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S.; Kim, S. The role of guilt in influencing sustainable pro-environmental behaviors among shoppers. J. Advert. Res. 2017, 58, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, B.M.; Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Age and environmental sustainability: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 826–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ágoston, C.; Balázs, B.; Mónus, F.; Varga, A. Age differences and profiles in pro-environmental behavior and eco-emotions. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2024, 48, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiry, B.; Nakhaei, A. Consumers’ green purchase decision: An examination of environmental beliefs, environmental literacy and demographics. Int. J. Mark. Technol. 2012, 2, 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Grazhdani, D. Assessing the variables affecting on the rate of solid waste generation and recycling: An empirical analysis in Prespa Park. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekito, T.; Prayogo, T.B.; Dote, Y.; Yoshitake, T.; Bagus, I. Influence of a community-based waste management system on people’s behavior and waste reduction. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 72, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-Levi, N. Do the rich recycle more? Understanding the link between income inequality and separate waste collection within metropolitan areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, R.; Rossouw, A. An evaluation of interventions for improving pro-environmental waste behaviour in social housing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.L. An assessment of multi-family dwelling recycling in Hong Kong: A managerial perspective. Waste Manag. 2019, 89, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, J.; Wagner, C. The effect of housing type on householders’ self-reported participation in recycling. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 9, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: Testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis in a field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, R. Expanding and evaluating motives for environmentally responsible behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity, and environmental preferences, intentions, and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, J.; Alenčikienė, G.; Riipi, I.; Starkutė, U.; Čepytė, K.; Buraitytė, A.; Zabulionė, A.; Šalaševičienė, A. Exploring causes and potential solutions for food waste among young consumers. Foods 2023, 12, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccarroll, D.; Crays, N.; Dunlap, W.P. Sequential ANOVAs and Type I error rates. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1992, 52, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Z. Generational differences in sustainable consumption behavior among Chinese residents: Implications based on perceptions of sustainable consumption and lifestyle. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Meyer, R. Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S.; Lorenzoni, I. Public engagement with climate change: What do we know and where do we go from here? Int. J. Media Cult. Politics 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, H.B.; Parks, C. Perceptions of behaviors that cause and mitigate global warming and intentions to perform these behaviors. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I.; Sun, H.; Mccole, P.; Ramsey, E.; Lim, K.H. Trust, satisfaction, and online repurchase intention: The moderating role of perceived effectiveness of E-commerce institutional mechanisms. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, N.; Shenstone-Harris, S.; Young, N. Using nudges to reduce waste? The case of Toronto’s plastic bag levy. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, C.; Gifford, R. The validity of self-report measures of pro-environmental behavior: A meta-analytic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchegaray, J.M.; Fischer, W.G. Understanding evidence-based research methods: Pilot testing surveys. HERD 2011, 4, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147–158. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/227 (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Characteristic | Category | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 119 (35.5%) |

| Female | 216 (64.5%) | |

| Age | 15–24 | 60 (17.9%) |

| 25–34 | 107 (31.9%) | |

| 35–44 | 82 (24.5%) | |

| ≥45 | 86 (25.7%) | |

| Educational level | Secondary or below | 47 (14.0%) |

| Post-secondary diploma or certificate | 38 (11.3%) | |

| College, university, or postgraduate | 250 (74.6%) | |

| Monthly income (USD 1 = HKD 7.8) | ≤HKD 9999 | 63 (18.8%) |

| HKD 10,000–19,999 | 80 (23.9%) | |

| HKD 20,000–29,999 | 100 (29.9%) | |

| ≥HKD 30,000 | 92 (27.5%) | |

| Housing type | Public housing | 142 (42.4%) |

| Private housing and others | 193 (57.6%) |

| Independent Variable | Opt-Out Behavior | Support for Government Policy | Support for Plastic-Free Restaurants | Price Sensitivity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Prob. | F | Prob. | F | Prob. | F | Prob. | |

| Gender | 1.604 | 0.206 | 0.017 | 0.895 | 2.346 | 0.127 | 1.132 | 0.288 |

| Age | 1.913 | 0.127 | 2.834 | 0.038 * | 2.696 | 0.046 * | 0.772 | 0.510 |

| Educational level | 8.557 | 0.000 ** | 0.425 | 0.654 | 4.573 | 0.011 * | 0.800 | 0.450 |

| Monthly income | 3.057 | 0.029 * | 0.924 | 0.429 | 0.479 | 0.697 | 2.003 | 0.113 |

| Housing type | 3.381 | 0.067 | 0.158 | 0.691 | 0.793 | 0.374 | 0.006 | 0.939 |

| Order frequency | 6.089 | 0.014 * | 8.743 | 0.003 ** | 5.321 | 0.022 * | 2.094 | 0.149 |

| Opt-out effectiveness | 2.732 | 0.099 | 0.373 | 0.542 | 0.037 | 0.847 | 3.889 | 0.049 * |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Wilks’ Lambda | F | Prob. | Partial η2 | Non- Centrality | Observed Power | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Overall | 0.925 | 1.982 | 0.023 * | 0.026 | 20.942 | 0.879 | H2a |

| Age | Support for plastic-free restaurants | -- | 2.721 | 0.045 * | 0.026 | 8.162 | 0.658 | H2d |

| Educational level | Opt-out behavior | -- | 6.650 | 0.001 ** | 0.042 | 13.300 | 0.912 | H3b |

| Opt-out effectiveness | Price sensitivity | -- | 4.712 | 0.031 * | 0.015 | 4.712 | 0.581 | H7e |

| Age × order frequency | Overall | 0.910 | 2.394 | 0.005 ** | 0.031 | 25.283 | 0.941 | H9a |

| Age × order frequency | Opt-out behavior | -- | 4.380 | 0.005 ** | 0.042 | 13.140 | 0.870 | H9b |

| Age × order frequency | Support for plastic-free restaurants | -- | 5.122 | 0.002 ** | 0.048 | 15.367 | 0.920 | H9d |

| Monthly income × order frequency | Support for plastic-free restaurants | -- | 3.133 | 0.026 * | 0.030 | 9.398 | 0.726 | H11d |

| Age × opt-out effectiveness | Overall | 0.894 | 2.848 | 0.001 ** | 0.037 | 30.066 | 0.975 | H14a |

| Age × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | -- | 5.031 | 0.002 ** | 0.048 | 15.092 | 0.915 | H14b |

| Age × opt-out effectiveness | Price sensitivity | -- | 3.742 | 0.012 * | 0.036 | 11.227 | 0.807 | H14e |

| Educational level × opt-out effectiveness | Overall | 0.946 | 2.114 | 0.033 * | 0.028 | 16.915 | 0.848 | H15a |

| Educational level × opt-out effectiveness | Opt-out behavior | -- | 3.912 | 0.021 * | 0.025 | 7.824 | 0.703 | H15b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ng, S.-L.; Hsieh, Y.-C. Understanding Demographic and Behavioral Determinants of Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction: Behavior, Support, and Price Sensitivity. Recycling 2025, 10, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030103

Ng S-L, Hsieh Y-C. Understanding Demographic and Behavioral Determinants of Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction: Behavior, Support, and Price Sensitivity. Recycling. 2025; 10(3):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030103

Chicago/Turabian StyleNg, Sai-Leung, and Yu-Chieh Hsieh. 2025. "Understanding Demographic and Behavioral Determinants of Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction: Behavior, Support, and Price Sensitivity" Recycling 10, no. 3: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030103

APA StyleNg, S.-L., & Hsieh, Y.-C. (2025). Understanding Demographic and Behavioral Determinants of Engagement in Plastic Tableware Reduction: Behavior, Support, and Price Sensitivity. Recycling, 10(3), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030103