Abstract

Three different methods were used to produce α-Ni(OH)2 with higher discharge capacities than the conventional β-Ni(OH)2, specifically a batch process of co-precipitation, a continuous process of co-precipitation with a phase transformation step (initial cycling), and an overcharge at low temperature. All three methods can produce α-Ni(OH)2 or α/β mixed-Ni(OH)2 with capacities higher than that of conventional β-Ni(OH)2 and a stable cycle performance. The second method produces a special core–shell β-Ni(OH)2/α-Ni(OH)2 structure with an excellent cycle stability in the flooded half-cell configuration, is innovative and also already mass-production ready. The core–shell structure has been investigated by both scanning and transmission electron microscopies. The shell portion of the particle is composed of α-Ni(OH)2 nano-crystals embedded in a β-Ni(OH)2 matrix, which helps to reduce the stress originating from the lattice expansion in the β-α transformation. A review on the research regarding α-Ni(OH)2 is also included in the paper.

1. Introduction

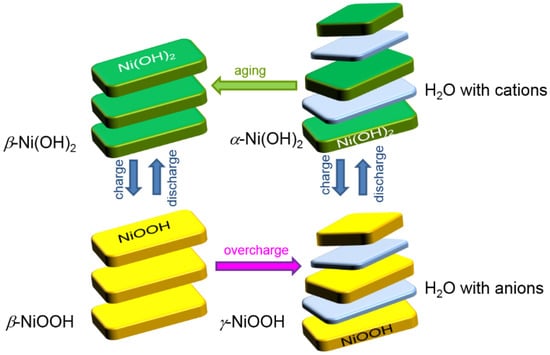

Nickel hydroxide has been used as the positive electrode for various rechargeable alkaline batteries for a long time. The history extends from Ni-Fe [1] and Ni-Cd [2], which were invented over 100 years ago, to Ni-H, Ni-Zn, and the current Ni/metal hydride (MH) batteries. The advantages of using nickel hydroxide include relatively low cost, adequate redox voltage (close to the oxygen gas evolution potential to maximize the operation voltage), good high-rate dischargeability (HRD) performance, and wide operation and storage temperature ranges. US Patents [3] and Japanese Patent Applications [4] for nickel hydroxide as a positive electrode active material were previously reported by our group. While the conventional nickel hydroxide used in the battery went through a β-Ni(OH)2-Ni(II)/β-NiOOH-Ni(III) redox electrochemical reaction, Bode et al. demonstrated another redox reaction between α-Ni(OH)2-Ni(II)/γ-NiOOH-Ni(III) [5]. The α–γ transformation may involve more than one electron transfer per Ni atom (up to 1.6 to 1.67 electrons [6,7]) due to the non-integral average oxidation states of the α and γ phases that occur because of the presence of anions (NO3−, CO32−, SO42−, Cl−, etc.) and cations (Li+, Na+, K+, etc.) in the water layers in α-Ni(OH)2 and γ-NiOOH, respectively [8,9,10] (see Bode’s diagram in Figure 1). The relatively large theoretic capacity of α–γ transformation (462–480 mAh·g−1), compared to that in the β(II)–β(III) transformation (289 mAh·g−1), makes it a very attractive research topic for electrochemical material scientists. These efforts are summarized in Table 1. The most common preparation methods involve co-precipitations using metal nitrates or sulfates. Since the beginning, pure α-Ni(OH)2 was found to be unstable and will convert to β-Ni(OH)2 through a slow aging process [11]. Trivalent elements, such as Al, Y, and La, have been added to stabilize the α-Ni(OH)2 phase. Other elements, such as Mg, Fe, Co, Cu, Zn, Ce, Nd, and Yb, have also been previously reported. In the case of battery operation using the β–β one-electron transition, the α-Ni(OH)2 phase formed during accidental overcharge will cause the early failure of the battery [12] and, thus, Zn is co-precipitated in commercial Ni(OH)2 batteries to suppress the formation of α-Ni(OH)2 [13,14]. The research target of α-Ni(OH)2 switched from capacity and cycle stability in the early days, to HRD, then to tap density, which are all important criteria for a suitable battery material. With research funding from the U.S. Department of Energy [15], we were able to further investigate the feasibility of mass production, in particular integration of β-Ni(OH)2 with the currently used fabrication method.

Figure 1.

Bode’s diagram showing the relationship among various hydroxides and oxyhydroxides of Ni. The lattice constants c in α-Ni(OH)2 and γ-NiOOH are larger than those in β-Ni(OH)2 and β-NiOOH, due to the insertion of an extra layer of water between the two Ni-containing sheets.

Table 1.

Summaries of prior works on producing α-Ni(OH)2 and mixed α/β-Ni(OH)2 for electrochemical applications. EP, CP, and ECI denote electrochemical precipitation, chemical precipitation, and electrochemical impregnation, respectively. In addition, α-Ni(OH)2 and β-Ni(OH)2 are represented by α and β, respectively. The concentration of the main dopant in molar percentage is listed in the Main Dopant column.

2. Experimental Setup

Three α-Ni(OH)2 fabrication methods were adopted in this research: a batch process designed for small-scale laboratory implementation and benchmark sample preparation; a continuous process with the identical design principle to our mass-production equipment; and a low-temperature formation process for converting β-Ni(OH)2 into α-Ni(OH)2 material. The sample names, compositions, and fabrication methods are summarized in Table 2. The batch process was composed of the following steps. First, 11.6 g (0.063 mol) of Ni(NO3)2 and 3 g (0.014 mol) of Al(NO3)3 were dissolved in 500 mL distilled water and the solution was denoted as Solution 1. Next, 60 g (0.075 mol) of NaOH and 15.6 g (0.15 mol) of Na2CO3 were dissolved in 500 mL distilled water and called Solution 2. Finally, 6.4 g (0.12 mol) of NH4Cl was dissolved in 100 mL distilled water, and NH3·H2O was added until the pH value reached 10, which formed Solution 3. Solutions 1 and 2 were gradually pumped into Solution 3 while maintaining a pH value in a range of 10–10.2. The color of the mixture solution was purple. After Solution 1 was exhausted, Solution 2 was constantly pumped into the mixed solution to increase the pH value to a range of 11.0–11.2. During this process, the solution color changed from purple to blue-green. This mixture was stirred for 5 h at room temperature. The final mixture was aged at 60 °C for 8 h, and then filtered and washed with deionized water. The obtained solid was dried at 60 °C in air for 5 h and used as the Ni-2 sample in this experiment. The Ni-1 sample was fabricated in the same way, except for the sole 14.7 g (0.077 mol) Ni(NO3)2 used in Solution 1.

Table 2.

List of samples used in this study. WSU and SZHP are abbreviations for Wayne State University (Detroit, MI, USA) and Shenzhen Highpower Technology Co. (Shenzhen, China).

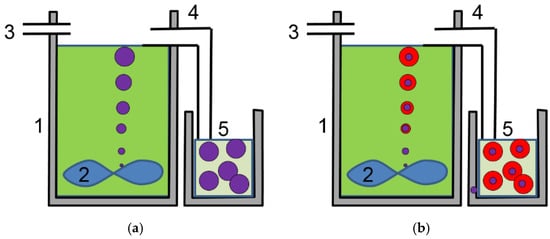

The second method used the same continuous stirring tank reactor (CSTR) technique that we developed to mass-produce NiCoZn hydroxide (for cathode active material in Ni/MH battery) and NiMnCo hydroxide (for precursor of NiMnCo (NMC) cathode material used in Li-ion battery) spherical particles [76]. The prototype of the equipment is installed in Troy, MI, USA and is capable of producing 1 ton of powder per day. A smaller version of the CSTR, capable of producing 1 kg of powder per day, was used for this experiment. In a CSTR, reactants in solution, sulfates and NaOH, and ammonia buffer solution were pumped into a reactor at different rates (three in Figure 2), while maintaining a constant reactor temperature (70 °C) and pH value. Small sized crystallites nucleated at the bottom of the reactor (1) and brought up to the top of the liquid surface by a stirring blade (2) at the bottom of the reactor. During the moving from the lower part to the higher part of the reactor, the hydroxide plates conglomerated into spherical shapes and were carried out by the overflow (4) into a storage container (5). At the end of each run, the solid product in the container was rinsed with deionized water and then dried to powder in hot air. Two controls used in BASF (AP50) and Shenzhen HighPower Co. (YRM3) were made by the commercial scale of CSTR process (Figure 2a). In preparation for WM02 (lower Co-content) and WM12 (higher Co-content), an addition Al source from Al(NO3)3 solution was added in the feed-in solution throughout the entire process. With a higher Co-level, core–shell structured spherical particles can be produced with a higher Al-content in the shell than in the core (WM12). The core–shell structure is formed by the different solubility of Al at different stages of particle growth (Figure 2b). This is very different from another core (Ni(OH)2)-shell (Ni0.5Mn0.5(OH)2) material prepared by a two-step method (core first and followed by the precipitation of shell with different composition solution) reported by Camardese et al. [77]. When the Co-content is lower, the differential solubility of Al disappears and the distribution of Al is uniform throughout the particle (Figure 2a, WM02). The full-cell testing of WM12 was done in a pouch-cell [15]. The negative electrode used here was a dry-compacted AB5 (La10.5Ce4.3Pr0.5Nd1.4Ni60.0Co12.7Mn5.9Al4.7) MH alloy electrode with a 20% increase in capacity (an negative/positive (N/P) design of 1.2). The electrolyte used was the standard 30% KOH and the separator was a grafted polyethylene (PE)/polypropylene (PP). The cell construction was electrolyte-flooded.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of (a) a continuous stirring tank reactor (CSTR) used to co-precipitate hydroxides of metals with similar solubilities, such as Co, Ni, and Zn, and a consistent composition throughout the spherical particles; and (b) a CSTR to incorporate larger atoms, such as Al and Y, which have lower precipitation rates at initial nucleation stage (purple core) and higher precipitation rates at the growth stage (red shell). 1: stainless-steel vessel; 2: mixer blade; 3: raw material inlet; 4: product overflow; and 5: product container.

The third method is to convert β-Ni(OH)2 into α-Ni(OH)2 in a sealed cell by using a low-temperature formation scheme. AA-sized Ni/MH cells with a nominal capacity of 1200 mAh were made using a standard commercially available AB5 (La10.5Ce4.3Pr0.5Nd1.4Ni60.0Co12.7Mn5.9Al4.7) paste negative electrode, co-precipitated YRM3 (Ni0.93Co0.02Al0.05(OH)2) paste positive electrode, a grafted polypropylene (PP)/polyethylene (PE) separator, and 30% KOH as the electrolyte. After being filled with electrolyte and sealed, cells underwent a standard three-cycle electrical formation process performed at room temperature. For capacity measurements before the low-temperature treatment, these cells were charged at 120 mA (C/10 rate) for 16 h (160% state of charge, SOC) at 20 °C and put to rest for 4 h at the same temperature. Cells were then discharged with 240 mA (C/5 rate) at 20 °C until a cut-off voltage of 1 V was reached, following which the discharge capacities were recorded. The cells were cooled to 10 °C and then overcharged with a current of 120 mA (C/10) for 30 days at that temperature. Cells were discharged with 240 mA (C/5) at 10 °C until a cut-off voltage of 1 V was reached and capacities were recorded. Cells were then brought back to 20 °C and charged with 120 mA for 16 h, followed by a 4 h rest, and discharged with 240 mA until 1 V was reached and the capacities were recorded.

For electrochemical testing of the powder, carbon black and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were used in the preparation of the positive electrode to enhance conductivity and electrode integrity. To this end, 100 mg of active material was first stir-mixed thoroughly with carbon black and PVDF in a weight ratio of 3:2:1 and applied onto a 0.5 × 0.5 in2 nickel mesh with a nickel mesh tab leading out of the square substrate for the electrical connection. The electrode was then pressed under three tons of pressure for 5 s. The negative counter electrode used was a dry-compacted AB5 type alloy. The positive and negative electrodes were sandwiched together with a polypropylene/polyethylene separator in a flooded half-cell configuration. The capacity of the negative electrode was significantly more than that of the positive electrode, resulting in a positive limited design. Electrochemical testing was performed with an Arbin electrochemical testing station (Arbin Instrument, College Station, TX, USA). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed with a Philips X’Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and the generated patterns were fitted and peaks indexed by the Jade 9 software (Jade Software Corp. Ltd., Christchurch, New Zealand). A JEOL-JSM6320F scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was applied in investigating the phase distributions and compositions of the powders. An FEI Titan 80–300 (scanning) transmission electron microscope (TEM/STEM, Hillsboro, OR, USA) was employed to study the microstructure of the core–shell structure of the α/β mixture from the continuous process. For TEM characterization, mechanical polishing was used to thin samples, followed by ion milling.

3. Results

3.1. Batch Process

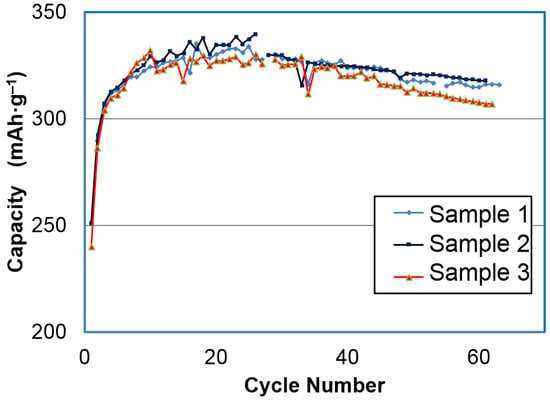

Two different conditions (Ni-1 and Ni-2) were employed in the batch process [15]. While Ni-1 has a composition that incorporates pure Ni as the cation source, which exhibits an exclusively β-Ni(OH)2 structure, Ni-2 is doped with 14 at % Al and show a typical α-Ni(OH)2 structure. The discharge capacities for the three samples from the Ni-2 process are shown in Figure 3. It took approximately 15 cycles to stabilize the capacity. The highest discharge capacity obtained with a 25 mA·g−1 rate was 346 mAh·g−1 at the 25th cycle.

Figure 3.

Half-cell capacity measurement of three α-Ni(OH)2 samples prepared by the batch process Ni-2 with charge and discharge currents at 25 mA·g‒1 (charged for 18.5 h). Capacity calculations are based on the weight of the active material.

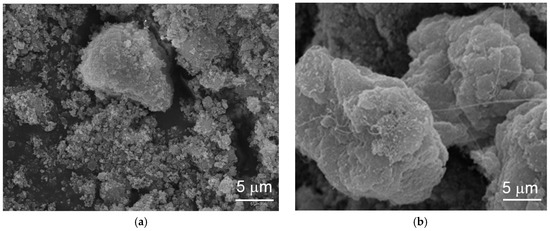

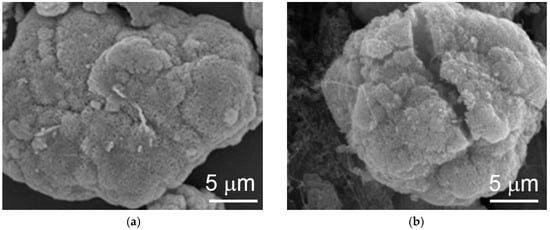

The topologies of the particles before and after electrochemical cycling were studied by SEM and the corresponding micrographs are shown in Figure 4. The pristine material shows a granular structure and conglomerates into larger particles with cycling. The growth in size with cycling retards cracking of the particle, due to the lattice expansion from β-Ni(OH)2 to α-Ni(OH)2, which is a common failure mode for capacity degradation in α-Ni(OH)2 [12,78]. Small amounts of capacity degradation can be seen after 25 cycles due to partial electrode disintegration in the flooded-configuration.

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of α-Ni(OH)2 prepared by the Ni-2 batch process (a) before and (b) after the flooded half-cell electrochemical capacity measurements.

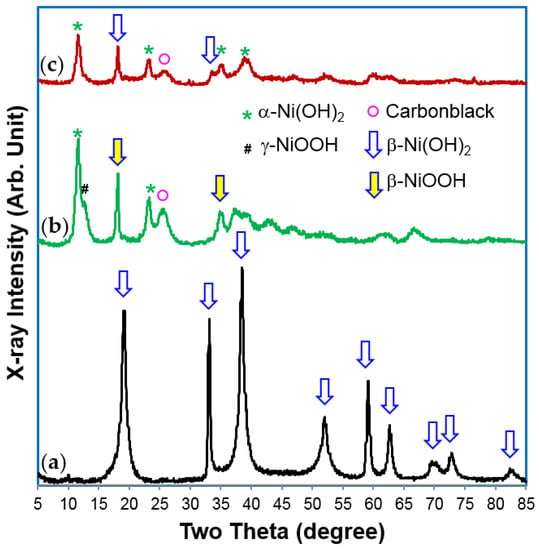

XRD analysis results indicate a β-Ni(OH)2 structure for the material before cycling, which turned into an α-Ni(OH)2–predominant structure after cycling (Figure 5). The different peak widths of the XRD patterns (especially in Figure 5a) are the products of preferential growth of Ni(OH)2 flakes on the ab-plane and various stacking faults [79]. The product may be further improved (especially the cycle stability) for battery applications, but the process itself is complicated and currently limited to a laboratory scale. Mass production of the batch process will not be cost-effective.

Figure 5.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, using Cu-Kα as the radiation source, for α-Ni(OH)2 samples prepared by the Ni-2 batch process in the (a) pristine; (b) charge; and (c) discharge state. After formation, the material changes in structure from a β-Ni(OH)2 to an α-Ni(OH)2–predominant phase. During charge, α-Ni(OH)2 was converted into a γ-NiOOH structure.

3.2. Continuous Production

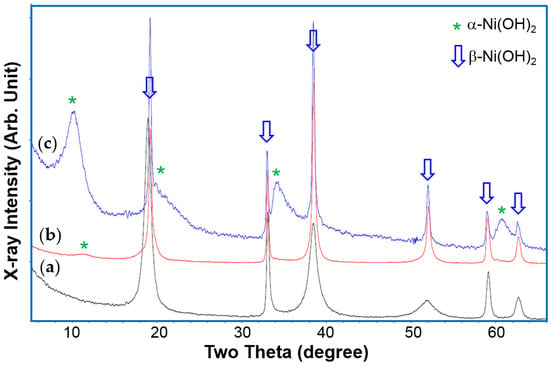

In the Robust Affordable Next Generation Energy Storage System (RANGE) program funded by the US Department of Energy, a series of research efforts were dedicated to the synthesis of a durable and high capacity nickel hydroxide using the CSTR method [15]. We first confirmed that Al is effective in promoting nucleation of the α-Ni(OH)2 phase. The XRD patterns from three samples with 0, 4, and 20 at % Al are shown in Figure 6. While the pristine Al-free sample shows a pure β-Ni(OH)2 structure (Figure 6a), the sample with 4% Al shows a small hint of α-Ni(OH)2, and the third sample, with 20% Al-content, is dominated by the α-Ni(OH)2 structure even without electrochemical cycling. For the rest of the materials, two chemistries were chosen for comparison: WM02 and WM12 (compositions listed in Table 3). Their preparation parameters and key performances are also listed in Table 3.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns, using Cu-Kα as the radiation source, from Ni(OH)2 samples prepared by the CSTR process with (a) 0; (b) 4; and (c) 20 at % Al in the pristine stage.

Table 3.

Parameter differences between WM02 and WM12.

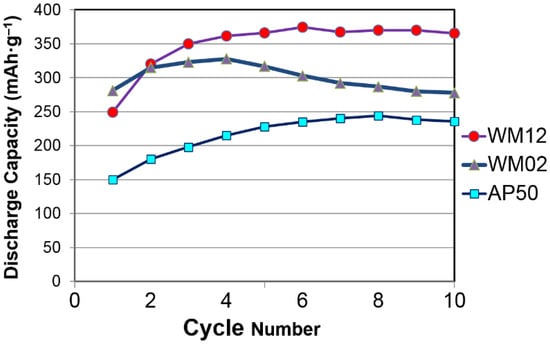

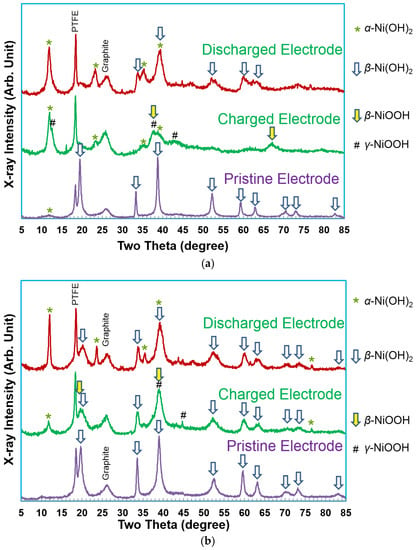

The results from the capacity measurement of WM02, WM12, and AP50 (a control sample of β-Ni(OH)2 with a cation composition of Ni0.91Zn0.045Co0.045) are presented in Figure 7. Both WM02 and WM12 show a higher discharge capacity than AP50. WM02 has a higher initial capacity, but also a more severe degradation in capacity. The XRD patterns of WM02 and WM12 in pristine, charged, and discharged states are compared in Figure 8. According to the XRD results, both WM02 and WM12 started with a pure β-Ni(OH)2 structure and are converted into α-Ni(OH)2-predominated and α/β mixed Ni(OH)2 state, respectively. The XRD peaks in the pristine WM12 are broader than those in the pristine WM02, indicating a smaller crystallite (platelet) in WM12, which is confirmed by the TEM work showed later in this session.

Figure 7.

Half-cell capacity measurements for α/β Ni(OH)2 (WM12), α-Ni(OH)2 (WM02), and β-Ni(OH)2 (AP50 with a cation composition of Ni91Co4.5Zn4.5) prepared by the CSTR process with charge and discharge currents at 25 mA·g‒1 (charge for 18.5 h). Capacity calculations are based on the weight of the active material.

Figure 8.

XRD patterns, using Cu-Kα as the radiation source, of (a) α-Ni(OH)2 (WM02) and (b) αβ-Ni(OH)2 (WM12) prepared by the CSTR process at three different stages.

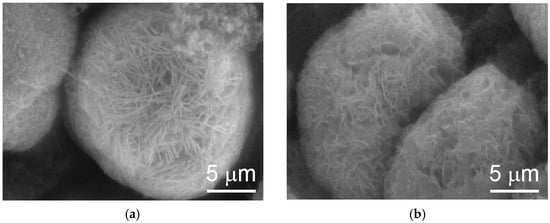

SEM analysis results show that cracking in the cycled WM02 spherical particles is due to swelling caused by the β-to-α transition (Figure 9b) and that WM12 maintained the same shape after 20 cycles (Figure 10). In addition, the surface morphologies of the two materials are different. While WM02 spherical particles have a more compact surface with a granular texture, WM12 spherical particles have a less dense surface with crystallite plates aligning perpendicular to the surface. The surface area and pore density of WM02 are smaller than those of WM12 with the same average pore diameter (Table 3).

Figure 9.

SEM micrographs of α-Ni(OH)2 (WM02) prepared by the CSTR process (a) before and (b) after 20 cycles.

Figure 10.

SEM micrographs of α/β-Ni(OH)2 (WM12) prepared by the CSTR process (a) before and (b) after 20 cycles.

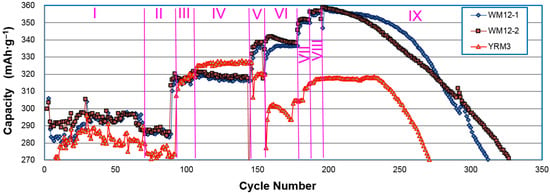

In another comparison test, three samples (two WM12 and one control β-Ni(OH)2) (YRM3: Ni0.93Co0.02Al0.05(OH)2) underwent nine different charge/discharge conditions (Table 4) and the obtained capacities are plotted in Figure 11. While the increases in charge current density from 50 to 75 and 125 mA·g‒1 in stages III and IV boosted capacities for both WM12 and β-Ni(OH)2, further increase in the charge current density (stage V) improved the capacity of WM12, but not β-Ni(OH)2. It seems that WM12 benefits, but β-Ni(OH)2 deteriorates with faster charge. From this comparison, the superiorities in the discharge capacity and cycle stability of WM12, compared to the regular material, are validated. The final failure mechanisms for both materials (WM12 and the β-Ni(OH)2) are the same: electrode disintegration due to particle pulverization.

Table 4.

Various test conditions for the half-cell capacity measurements of two α/β core–shell samples from the continuous process (WM12-1 and WM12-2) and a control β-Ni(OH)2 sample (YRM3). Charge and discharge currents are in mA·g−1 units and time is in h. Total amount of charge-in is in mAh·g−1.

Figure 11.

Half-cell capacity measurements of two α/β Ni(OH)2 (WM12-1 and WM12-2) and one β-Ni(OH)2 (YRM3 with a cation composition of N93Zn5Co2) samples prepared by the CSTR. The charge and discharge current densities for each stage are listed in Table 4. Capacity calculations are based on the weight of the active material.

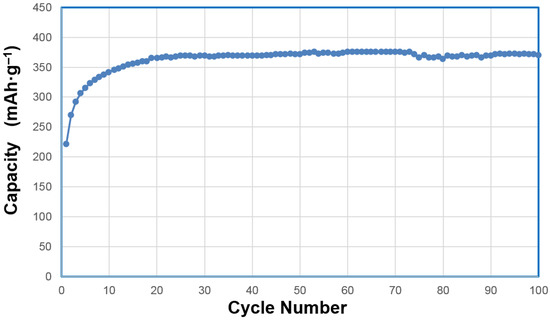

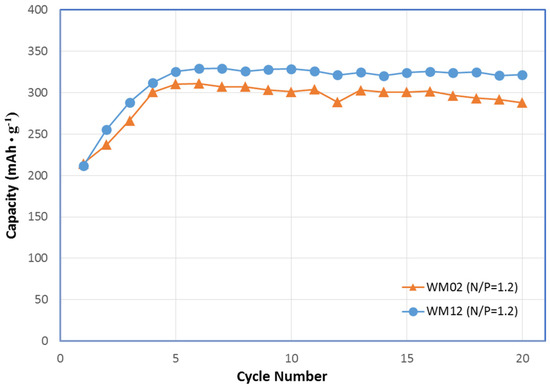

In a separate cycle life experiment, we performed a 100 mA·g‒1 rate charge for 5.5 h and discharged at the same rate. Results are shown in Figure 12. The highest capacity of 376 mAh·g‒1 was obtained during the 61th cycle and the capacity at the 100th cycle was 371 mAh·g‒1. With the success in the half-cell experiment (with 50% additional binder and electrical conduction enhancer), we began the full-cell measurement of WM12 and WM12 in the newly developed pouch-type Ni/MH battery [15]. Only 10% binder and electrical conduction enhancer were added in the positive electrode and the capacity results, based on the total material weight (active plus additives), are plotted in Figure 13. Discharge capacities of 329 mAh·g‒1 and 311 mAh·g‒1 were obtained for the positive electrodes of the WM12 and WM02 full cells, respectively. From this point, further tests on the full cells are planned and more results will be reported in the future, especially for the phase stability under storage condition since α-Ni(OH)2 is known to have an aging issue when stored in an alkaline solution [30]. It is obvious that the same WM12 material required less activation cycles and achieved a lower capacity in the sealed-cell configuration than that in the half-cell (6 versus 20). This is due to the reliance of the β–NiOOH to γ–NiOOH transition on the amount of over-charge. In the half-cell operated in the open atmosphere, the over-charging process has to compete with oxygen gas evolution and thus is less effective, compared to reactions operated in the sealed-cell configuration (more activation cycle is needed). The difference in the maximum capacities between two measurements is related to the expansion of unit cell that occurs in the β–NiOOH to γ–NiOOH transition. In the half-cell testing, the electrode was allowed to expand and, therefore, more NiOOH was converted, which differs from the limited space available in the sealed-cell.

Figure 12.

Half-cell capacity measurement of α/β Ni(OH)2 WM12 prepared by the CSTR process with charge and discharge currents at 100 mA·g‒1 (charge for 5.5 h). Capacity calculations are based on the weight of active material. The highest capacity of 376 mAh·g‒1 was obtained at the 61th cycle and the capacity at 100th cycle is 371 mAh·g‒1.

Figure 13.

Full-cell capacity measurement of α Ni(OH)2 WM02 and α/β Ni(OH)2 WM12 prepared by the CSTR process with charge and discharge currents at 100 mA·g‒1 (charge for 5.5 h). Capacity calculations are based on the weight of active material. The active material loading was increased from 50 wt % in the half-cell to 90 wt % in the full-cell with a 120% capacity AB5 dry-compacted negative electrode (negative/positive (N/P) = 1.2).

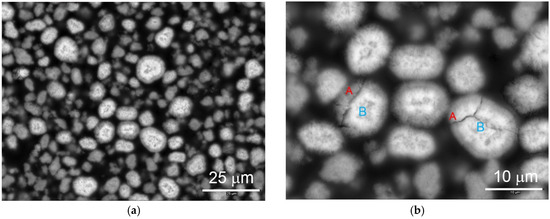

The microstructure of WM12 was studied by both SEM and TEM. Cross-section SEM backscattering electron images of activated WM12 at different magnifications are shown in Figure 14. Different contrasts can be observed in the shell (A, darker) and core (B, lighter). EDS analysis results show that the surface region has a higher Al-content (ca. 4 at %) than the core region (ca. 1.5 at %) [15]. The core–shell structure was produced in the CSTR with a differential precipitation of Al in the tank (Figure 2b). In the nucleation stage, near the bottom of the tank, less Al becomes crystallite due to its relatively large size and, thus, an Al-lean core forms. As the particles are moved into the upper portion of the reactor by the stirring blade, they grow in size with a higher Al-content in the shell part of the particle. Materials produced at this stage are still β-Ni(OH)2. Later, during electrochemical formation, the shell, with a relatively higher Al-content, develops a β-Ni(OH)2 structure.

Figure 14.

Cross-section SEM micrographs at different magnifications with scale bars indicating (a) 25 and (b) 10 µm. of α/β-Ni(OH)2 (WM12) prepared by the CSTR process showing a core (B)/shell (A) structure. After activation, the Al-rich A region (shell) becomes α-Ni(OH)2, while the Al-lean B region (core) remains β-Ni(OH)2.

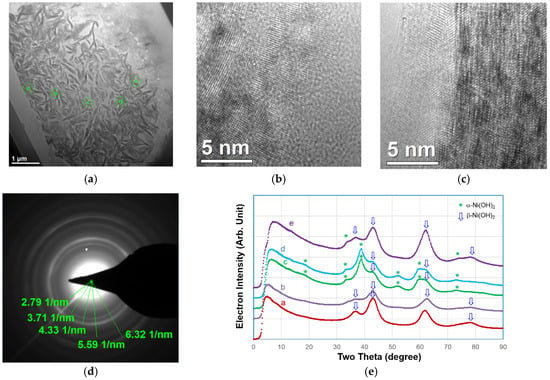

The microstructure of WM12 particle’s shell was further investigated by TEM. A representative TEM micrograph is shown in Figure 15a. The high-resolution TEM images taken from areas ⓑ (brighter) and ⓒ (darker) are shown in Figure 15b,c, respectively. Area ⓑ has a smaller inter-planar distance is β-Ni(OH)2, while area ⓒ, which has a larger inter-planar discharge, is α-Ni(OH)2. The electron diffraction from a representative selective 10-μm region, which covers the most of the particle shown in Figure 15a, is shown in Figure 15d. The integrated electron diffraction intensities were collected from the diffraction pattern for areas ⓐ‒ⓔ. For the convenience of comparison between the TEM and XRD results, the distance in reciprocal space obtained from TEM electron diffraction has been converted to a degree based system on the wave length of a Cu Kα X-ray and the results are shown in Figure 15e with the conversion to the standard XRD suing Cu Kα as the radiation source. Although the electron density plot is not identical to the XRD pattern, due to different scattering factors between X-rays and electron beams, the main features from a and b can still be distinguished and areas ⓐ‒ⓔ have been identified as β, β, β, β, and mixed α/β structures, respectively. Therefore, we conclude that the shell region of WM12 is composed of nano-sized α-Ni(OH)2 imbedded in a β-Ni(OH)2 matrix, which helps to distribute the stress from the lattice expansion during the α-β transition. The broader XRD peaks in the pristine WM12 indicate a small crystallite form, even before the α-β transition occurs.

Figure 15.

(a) TEM micrograph; (b) high-resolution images from area ⓑ (c) from area ⓒ in (a); (d) selective area diffraction pattern; and (e) integrated diffraction electron intensity (with distance in the reciprocal space obtained from TEM electron diffraction converted to a degree based system on the wavelength of Cu-Kα X-ray) of the shell-portion of a discharged electrode from WM12.

3.3. Low-Temperature Formation

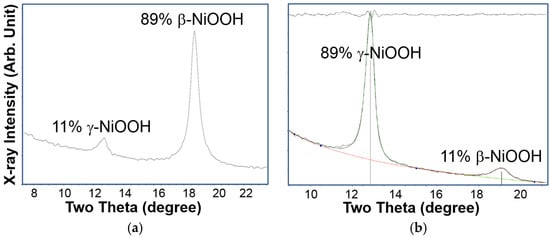

It is well known that applying overcharge to a positive-limited Ni/MH battery will result in oxygen gas evolution. During normal operation of Ni/MH batteries, the produced oxygen gas will recombine with the hydrogen stored in the negative electrode, forming water and generating heat. A charging process in the Ni(OH)2 based rechargeable alkaline battery is always a competition between oxidizing Ni(II) into Ni(III) and oxygen gas evolution. At room temperature, the oxygen evolution potential is raised by the co-precipitation of Co and Zn into spherical particles and, therefore, the charging process can be completed without any oxygen gas generation. At higher temperatures, where the potential of oxygen evolution is significantly reduced, the regular Ni-electrode cannot be charged fully and special high temperature Ni-electrodes have been developed to lower the oxidation potential of the Ni(II)/Ni(III) reaction [80]. When the cell is overcharged, part of its β-NiOOH will be converted into γ-NiOOH (see Bode’s diagram in Figure 1), but the conversion efficiency is low because most of the overcharge is consumed during oxygen gas evolution. If the overcharge is performed at a relative low temperature, then the β–γ conversion happens at a higher rate. This concept initiated the following experiment. Ten AA-cells were made from regular AB5 and YRMS (Ni0.93Co0.02Al0.05(OH)2) as the active materials in the negative and positive electrodes, respectively. These cells were exposed to a low-temperature overcharge process (C/10 rate at 10 °C for 30 days). Their discharge capacities before and after the treatment are listed in Table 5. More than a 15% increase in the discharge capacity was observed. The XRD patterns before and after the low-temperature treatment show a transition from 89% β-NiOOH/11% γ-NiOOH to 11% β-NiOOH/89% γ-NiOOH (Figure 16). This validates the effectiveness of low-temperature formation for α/γ-NiOOH. After disassembling the cell, we found swelling in the positive electrode due to the formation of a α/γ-NiOOH phase with an enlarged unit cell (about 74% [5]) from the insertion of a water layer between the NiOOH layers (Figure 1). The swelling of the positive electrode causes an approximate 8% increase in the internal resistance (Table 5) due to the breakdown in the Co- conductive network [12]. Future work will be focused on a solution that addresses this electrode swelling. For example, swelling could be alleviated through a coating of CoOOH, Yb(OH)3, or both on the spherical particles before electrode fabrication [12].

Table 5.

Capacities (in mAh) and internal resistance (in mΩ) of the AA cells measured at a C/10 rate before and after the overcharge (OC) at 10 °C.

Figure 16.

XRD patterns, using Cu-Kα as the radiation source, of the positive electrode from cells (a) before and (b) after the low-temperature overcharge treatment.

3.4. Comparisons

In order to better compare the three α- (α/β-mixed) Ni(OH)2 fabrication methods, a summary table is present (Table 6). A few key directions for future development are also included for each fabrication method.

Table 6.

Comparison of three fabrication methods for high-capacity Ni(OH)2 powder. DOD denoted degree of disorder in both composition and phase structure.

4. Conclusions

Three different fabrication methods for high-capacity α-Ni(OH)2 were presented. The batch and continuous processes employ an α-Ni(OH)2 promoter, such as Al, and reached stable cycle performance using a unique surface morphology and core–shell structure. While the batch process is currently only suitable for laboratory use, the continuous process with a later β-to-α formation process is much more cost-effective and already used in mass production. The low-temperature overcharge process does not require the Ni(OH)2 promoter. However, the particle size and paste additives require further development to address the increase in internal resistance due to the swollenness of the positive electrode.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy under the RANGE Program (DE-AR0000386).

Author Contributions

Kwo-Hsiung Young was the Principle Investigator of the program, designed the experiments, and organized the test results while Shuli Yan, William Mays, and Xingqun Liao conducted the material preparation in batch, continuous, and low-temperature formation processes, respectively. Lixin Wang and Tiejun Meng performed the electrochemical measurement and Haoting Shen did the TEM analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CP | Co-precipitation |

| CSTR | Continuous stirring tank reactor |

| DOD | Degree of disorder |

| ECI | Electrochemical impregnation |

| EDS | X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| HRD | High-rate dischargeability |

| MH | Metal hydride |

| NMC | NiMnCo |

| N/P | Negative/positive |

| OC | Overcharge |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| RANGE | Robust Affordable Next Generation Energy Storage System |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SOC | State of charge |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Edison, T.A. Reversible Galvanic Battery. U.S. Patent 678,722, 16 July 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Edison, T.A. Reversible Galvanic Battery. U.S. Patent 692,507, 4 February 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.; Young, K.; Nei, J.; Fierro, C. Reviews on the U.S. Patents Regrading nickel/metal hydride batteries. Batteries 2016, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, T.; Young, K. Reviews on the Japanese patent applications Regrading nickel/metal hydride batteries. Batteries 2016, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, H.; Dehmelt, K.; White, J. Zur kenntnis der nickelhydroxidelektrode—I. Über das nickel (II)-hydroxidhydrat. Electrochim. Acta 1966, 11, 1079–1087. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, D.A.; Knight, S.L. Electrochemical and spectroscopic evidence on the participation of quadrivalent nickel in the nickel hydroxide redox reaction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, D.A.; Bendert, R.M. Effect of coprecipitated metal ions on the electrochemistry of nickel hydroxide thin films: cyclic voltammetry in 1 M KOH. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, P.; Leonardi, J.; Laurent, J.F.; Delmad, C.; Braconnier, J.J.; Figlarz, M.; Fievet, F.; Guibert, A. Review of the structure and the electrochemistry of nickel hydroxides and oxy-hydroxides. J. Power Sources 1982, 8, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C.; Braconnier, J.J.; Borthomieu, Y.; Hagenmuller, P. New families of cobalt substituted nickel oxyhydroxides and hydroxides obtained by soft chemistry. Mater. Res. Bull. 1987, 22, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C.; Braconnier, J.J.; Borthomieu, Y. From sodium nickelate to nickel hydroxide. Solid State Ion. 1988, 28–30, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, M.C.; Bernard, P.; Keddam, M.; Senyarich, S.; Takenouti, H. Characterization of new nickel hydroxides during the transformation of α Ni(OH)2 to β Ni(OH)2 by aging. Electrochim. Acta 1996, 41, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.; Yasuoka, S. Capacity degradation mechanisms in nickel/metal hydride batteries. Batteries 2016, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayashree, R.S.; Kamath, P.V. Suppression of the α → β-nickel hydroxide transformation in concentrated alkali: Role of dissolved cations. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2001, 31, 1315–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, C.; Guerlou-Demourgues, L.; Faure, C.; Denage, C.; Delatouche, B.; Delmas, C. Influence of zinc on the stability of the β(II)/β(III) nickel hydroxide system during electrochemical cycling. J. Power Sources 2001, 102, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.; Ng, K.Y.S.; Bendersky, L.A. A technical report of the robust affordable next generation energy storage system-BASF program. Batteries 2016, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.D.; Charles, E.A. Some effects of cobalt hydroxide upon the electrochemical behavior of Nckel hydroxide electrodes. J. Power Sources 1989, 25, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, C.; Delmas, C.; Willmann, P. Electrochemical behavior of α-cobalted nickel hydroxide electrodes. J. Power Sources 1991, 36, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demourgues-Guerlou, L.; Delmas, C. Effect of iron on the electrochemical properties of the nickel hydroxide electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indira, L.; Dixit, M.; Kamath, P.V. Electrosynthesis of layered double hydroxides of nickel with trivalent cations. J. Power Sources 1994, 52, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, P.V.; Dixit, M.; Indira, L.; Shukla, A.K.; Kumar, V.G.; Munichandraiah, N. Stabilized α-Ni(OH)2 as electrode material for alkaline secondary cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1994, 141, 2956–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.G.; Munichandraiah, N.; Kamath, P.V.; Shukla, A.K. On the performance of stabilized α-nickel hydroxide as a nickel-positive electrode in alkaline storage batteries. J. Power Sources 1995, 56, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.; Kamath, P.V.; Munichandraiah, N.; Shukla, A.K. An electrochemically impregnated sintered-nickel electrode. J. Power Sources 1996, 63, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerlou-Demourgues, L.; Delmas, C. Electrochemical behavior of the manganese-substituted nickel hydroxides. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, X.Y.; Yuan, H.T.; Zhang, Y.S.; Song, D.Y.; Zhou, Z.X. Physical and electrochemical characteristics of aluminum-substituted nickel hydroxide. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1999, 29, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Song, D. Cyclic voltammetric studies of stabilized α-nickel hydroxide electrode. J. Power Sources 1999, 79, 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, M.; Jayashree, R.S.; Kamath, P.V.; Shukla, A.K.; Kumar, V.G.; Munichandraiah, N. Electrochemically impregnated aluminum-stabilized α-nickel hydroxide electrode. Electrochem. Solid State Lett. 1999, 2, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, A.; Ishida, S.; Janawa, K. Preparation and characterization of Ni/Al-layered double hydroxide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Li, S.F.Y.; Xiao, T.D.; Wang, D.M.; Reisner, D.E. Structural stability of aluminum stabilized alpha nickel hydroxide as a positive electrode material for alkaline secondary batteries. J. Power Sources 2000, 89, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; We, Y.; Cao, C. Preparation, structure and electrochemical performance of iron-substituted nickel hydroxide. Chin. J. Power Sources 2000, 24, 32–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, M.B.J.G. Nickel hydroxide powder for NiO·OH/Ni(OH)2 electrodes of the alkaline batteries. J. Power Sources 2001, 93, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, G.; Yin, Y.; Chen, H.; Jia, J. Study on the Y-doped α-Ni(OH)2. Chin. J. Appl. Chem. 2001, 18, 689–692. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Zhong, S.; Konstantinov, K.; Walter, G.; Liu, H.K. Structural study of Al-substituted nickel hydroxide. Solid State Ion. 2002, 148, 503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Luo, H.; Parkhutik, P.V.; Millan, A.; Matveeva, E. Studies of the performance of nanostructural multiphase nickel hydroxide. J. Power Sources 2003, 115, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.K.; Noréus, D. Alpha nickel hydroxides as lightweight nickel electrode materials for alkaline rechargeable cells. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Wang, J.M.; Zhao, Y.L.; Chen, H.; Xiao, H.M.; Zhang, J.Q. Al-stabilized α-nickel hydroxide prepared by electrochemical impregnation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003, 78, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lu, T. Solid state synthesis and electrochemical performance of α-Ni(OH)2 including 20% Al. Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 19, 535–538. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Wang, J.M.; Chen, H.; Pan, T.; Zhang, J.Q.; Cao, C.N. Al-substituted α-nickel hydroxide prepared by homogenous precipitation method with urea. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2004, 29, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Wang, J.M.; Chen, H.; Pan, T.; Zhang, J.Q.; Cao, C.N. Different additives-substituted α-nickel hydroxide prepared by urea decomposition. Electrochim. Acta 2004, 50, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, Y. Impedance of Al-substituted α-nickel hydroxide electrodes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2004, 29, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, K.; Sang, S. Preparation and electrochemical performance of lanthanum doping α-Ni(OH)2. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2005, 36, 898–993. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Xiang, L.; Jin, Y. Synthesis and high-temperature performance of Ti substituted α-Ni(OH)2. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2005, 15, 823–827. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Gao, X.; Noréus, D.; Burchardt, T.; Nakstad, N.K. Evaluation of nano-crystal sized α-nickel hydroxides as an electrode material for alkaline rechargeable cells. J. Power Sources 2006, 160, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Chen, Q.; Yin, Z. Electrochemical performance of multiphase nickel hydroxide. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2007, 17, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Xu, P.; Lv, Z.; Liu, X.; Wen, A. Effect of crystallinity on the electrochemical performance of nanometer Al-stabilized α-nickel hydroxide. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 462, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, A. Investigations on structure and proton diffusion coefficient of rare earth ion (Y3+/Nd3+) and aluminum co-doped α-Ni(OH)2. J. Rare Earths 2008, 26, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, C.; Song, S.; Li, G. Structure and electrochemical performances of Y and Al co-doped α-Ni(OH)2 electrode. Chin. J. Rare Met. 2009, 33, 366–370. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, M.; Kakeya, T.; Ochiai, S.; Ozaki, T.; Kawabe, Y.; Watada, M.; Sakai, T. Structural analysis by synchrotron X-ray diffraction, X-ray absorption fine structure and transmission electron microscopy for aluminum-substituted α-type nickel hydroxide electrode. J. Power Sources 2009, 1893, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y. Synthesis and characterization of amorphous α-nickel hydroxide. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 478, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; We, H.; Li, Y. Structure and electrochemical performance of Y(III) and Al(III) co-doped amorphous nickel hydroxide. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2009, 70, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidotti, M.; Salvador, R.P.; Torresi, S.I.C. Synthesis and characterization of stable Co and Cd doped nickel hydroxide nanoparticles for electrochemical applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009, 16, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Song, S.; Liu, A.; Li, G. Electrochemical performance and action mechanism of Ce/Al-codoped α-Ni(OH)2 as electrode material. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2009, 38, 540–543. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.D.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Yan, T.Y.; Gao, X.P. High-temperature electrochemical performance of Al-α-nickel hydroxides modified by metallic cobalt or Y(OH)3. J. Power Sources 2009, 186, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béléké, A.B.; Hosokawa, A.; Mizuhata, M.; Deki, S. Preparation of α-nickel hydroxide/carbon composite by the liquid phase deposition method. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 117, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; Yao, J.H.; Liu, C.J.; Zhao, W.M.; Deng, W.X.; Zhong, S.K. Effect of interlayer anions on the electrochemical performance of Al-substituted α-type nickel hydroxide electrodes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 2539–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L. Electrochemical performance of α-nickel hydroxide co-doped with La and Zn. CIESC J. 2010, 61, 2743–2747. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Chen, S.; Zhao, W.; Liu, C. Electrochemical performance of Mg and Al substituted α-Ni(OH)2. Guangdong Chem. Ind. 2010, 37, 142–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wu, H. Preparation and electrochemical performance of alpha-nickel hydroxide nanowire. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 126, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Zhu, Y.J.; Bao, J.; Lin, X.R.; Zheng, H.Z. Electrochemical performance of multi-element doped α-nickel hydroxide prepared by supersonic co-precipitation method. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 7034–7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, H.; Lin, X. Study on the preparation and electrochemical performance of rare earth doped nano-Ni(OH)2. J. Rare Earths 2011, 29, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, X.; Zheng, H.; Lin, X.; Bao, J. Effect of supersonic power and pH value on the structure and electrochemical performance of Y doped nano-Ni(OH)2. J. Mater. Eng. 2011, 6, 27–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Yao, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z. Homogeneous precipitation of α-phase Co-Ni hydroxides hexagonal platelets. Particuology 2012, 10, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Shen, K.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Kong, X. Electrodeposition of Zn-doped α-nickel hydroxide with flower-like nanostructure for supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 8117–8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Wang, H. Synthesis and electrochemical performance of mixed phase α/β nickel hydroxide. J. Power Sources 2012, 203, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máca, T.; Vondrák, J.; Sedlařiková, M.; Nezgoda, L. Incorporation of multielement doping into LDH structure of alpha nickel hydroxide. ECS Trans. 2012, 40, 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Han, Q. Structure and electrochemical properties of nanometer Cu substituted α-nickel hydroxide. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cao, P.; Lei, T.; Yang, S.; Zhou, X.; Xu, P.; Wang, G. Structural and electrochemical performance of Al-substituted β-Ni(OH)2 nanosheet electrodes for nickel metal hydride battery. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 111, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. Enhanced cycling performance of Al-substituted α-nickel hydroxide by coating with β-nickel hydroxide. J. Power Sources 2013, 224, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.Z.; Zhu, Y.J.; Lin, X.R.; Zhuang, Y.H.; Zhao, R.D.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, S.J. The influence of Na2Co3 content and Ni2+ concentration on the physicochemical properties of nanometer Y-substituted nickel hydroxide. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2013, 178, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shangguan, E.; Guo, D.; Tian, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H. Synthesis, characterization and electrochemical performance of high-density aluminum substituted α-nickel hydroxide cathode material for nickel-based rechargeable batteries. J. Power Sources 2014, 270, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shangguan, E.; Nie, M.; Jin, Q.; Zhao, K.; Chang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H. Enhanced electrochemical performance of high-density Al-substituted α-nickel hydroxide by a novel anion exchange method using NaCl solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 1852–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, E.; Li, J.; Guo, D.; Guo, L.; Nie, M.; Chang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H. A comparative study of structural and electrochemical properties of high-density aluminum substituted α-nickel hydroxide containing different interlayer anions. J. Power Sources 2015, 282, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, T. The relationship between structural stability and electrochemical performance of multi-element doped alpha nickel hydroxide. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Q. High-performance electrode materials of hierarchical mesoporous nickel oxide ultrathin nanosheets derived from self-assembled scroll-like α-nickel hydroxide. J. Power Sources 2015, 273, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Ma, W.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M.; Cui, H. Construction of cobalt substituted α-Ni(OH)2 hierarchical nanostructure from nanofibers on nickel foam and its electrochemical performance. Solid State Ion. 2015, 281, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhao, T. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical performances of alpha nickel hydroxide by coprecipitating Sn2+. Ionics 2015, 21, 2295–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, C.; Fetcenko, M.A.; Young, K.; Ovshinsky, S.R.; Sommers, B.; Harrison, C. Nickel Hydroxide Positive Electrode Material Exhibiting Improved Conductivity and Engineered Activation Energy. U.S. Patent 6,228,535, 8 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Camardese, J.; McCalla, E.; Abarbanel, D.W.; Dahn, J.R. Determination of shell thickness of spherical core-shell NixMn1–x(OH)2 particles via absorption calculations of X-ray diffraction patterns. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, A814–A820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Young, K.; West, J.; Regalado, J.; Cherisol, K. Degradation mechanisms of high-energy bipolar nickel metal hydride battery with AB5 and A2B7 alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 580, S373–S377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.F.; Young, K.; Wang, L.; Nei, J.; Mg, K.Y.S. Evolution of stacking faults in substituted nickel hydroxide spherical powders. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 695, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro, C.; Zallen, A.; Koch, J.; Fetcenko, M.A. The influence of nickel-hydroxide composition and microstructure on the high-temperature performance of nickel metal hydride batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A492–A496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).