Coupling Model and Early-Stage Internal Short Circuits Fault Diagnosis for Gel Electrolyte Lithium-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Because of the difference in ion transport and thermal performance between gel-electrolyte battery and liquid battery, there is still a gap in the research of internal short circuit safety of gel-state lithium-ion batteries.

- (2)

- The traditional methods require the establishment of modified pseudo two-dimensional models, three-dimensional electrochemical thermal internal short circuit coupling models, or equivalent circuit models. Algorithms also require complex methods such as recursive least squares, which have complex models, large computational complexity, and high practical application thresholds.

- (3)

- The traditional method is relatively simple, relying on threshold values and other judgment criteria. However, in actual situations, determining the parameter threshold is challenging as it requires consideration of multiple factors, resulting in low accuracy. Meanwhile, the diagnostic method based on ISC mechanisms and models involves complicated calculations, making it difficult to apply in practice.

- (4)

- Data-driven diagnostic methods require extensive ISC data, but conducting a large number of battery ISC experiments poses certain safety risks, and these experiments exhibit poor repeatability and controllability.

- (1)

- This study focuses on analyzing the thermal runaway process and mechanism of ISC in gel-electrolyte lithium-ion batteries. It provides a detailed analysis of the unique ISC mechanism in gel-electrolytes, highlighting the differences between gel-electrolyte batteries and liquid-electrolyte batteries in terms of ion transport and thermal performance. The research results can provide theoretical support for the safety design of battery cells and systems.

- (2)

- A battery electrochemical–thermal–ISC coupling model for lithium-ion batteries is established, which effectively addresses the challenge of acquiring ISC data by replacing physical ISC tests with simulation methods. Through the combination of model simulation and experimental testing, this approach solves the problem of poor controllability and repeatability in internal short circuit testing.

- (3)

- ISC prediction model grounded in deep learning was established. Deep learning model with both simplicity and accuracy and great application potential is established. Reduce complexity and improve accuracy through optimizer selection, learning rate strategy and architecture optimization.

2. Methodology

2.1. Principle

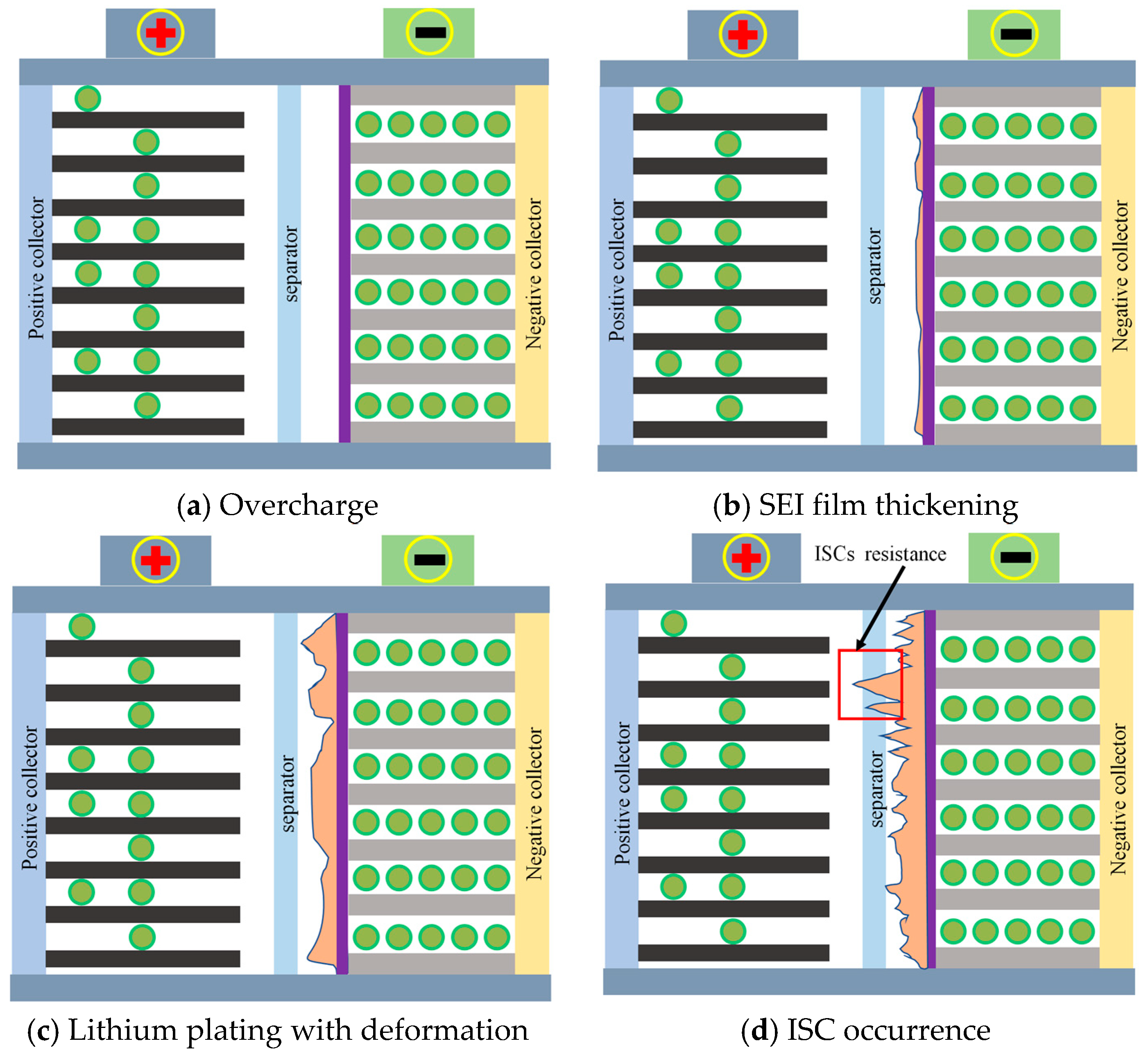

2.2. Mechanism Analysis of ISCs

2.3. Analysis of the ISC Process Principle

3. Coupling Model

3.1. Electrochemical Model

- (1)

- Solid phase and liquid phase lithium ion diffusion process

- (2)

- Solid phase and liquid phase electric potential distribution

- (3)

- Solid phase and liquid phase interface reaction

- (4)

- Battery terminal voltage

3.2. Thermal Model

3.3. ISC Model

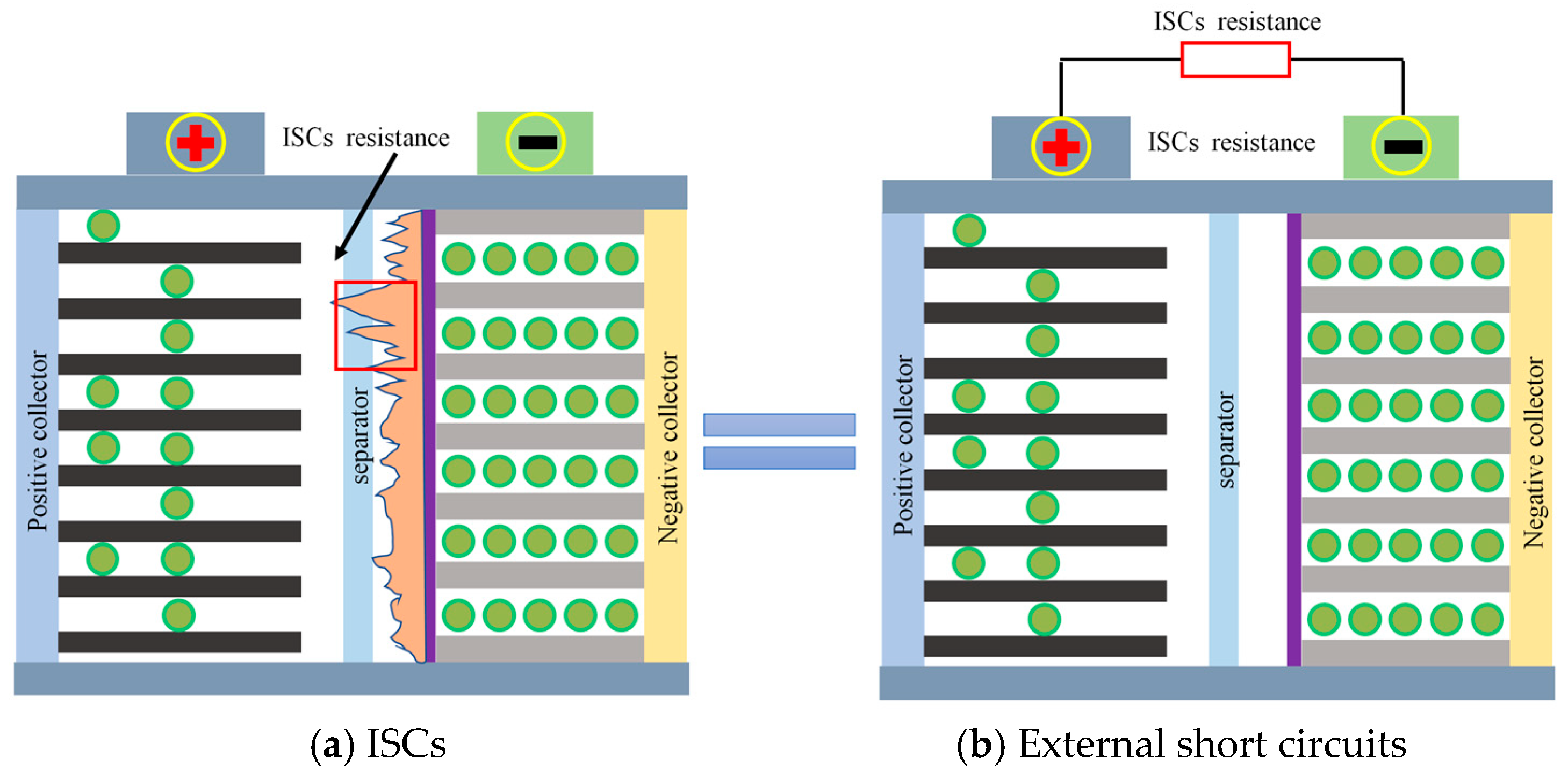

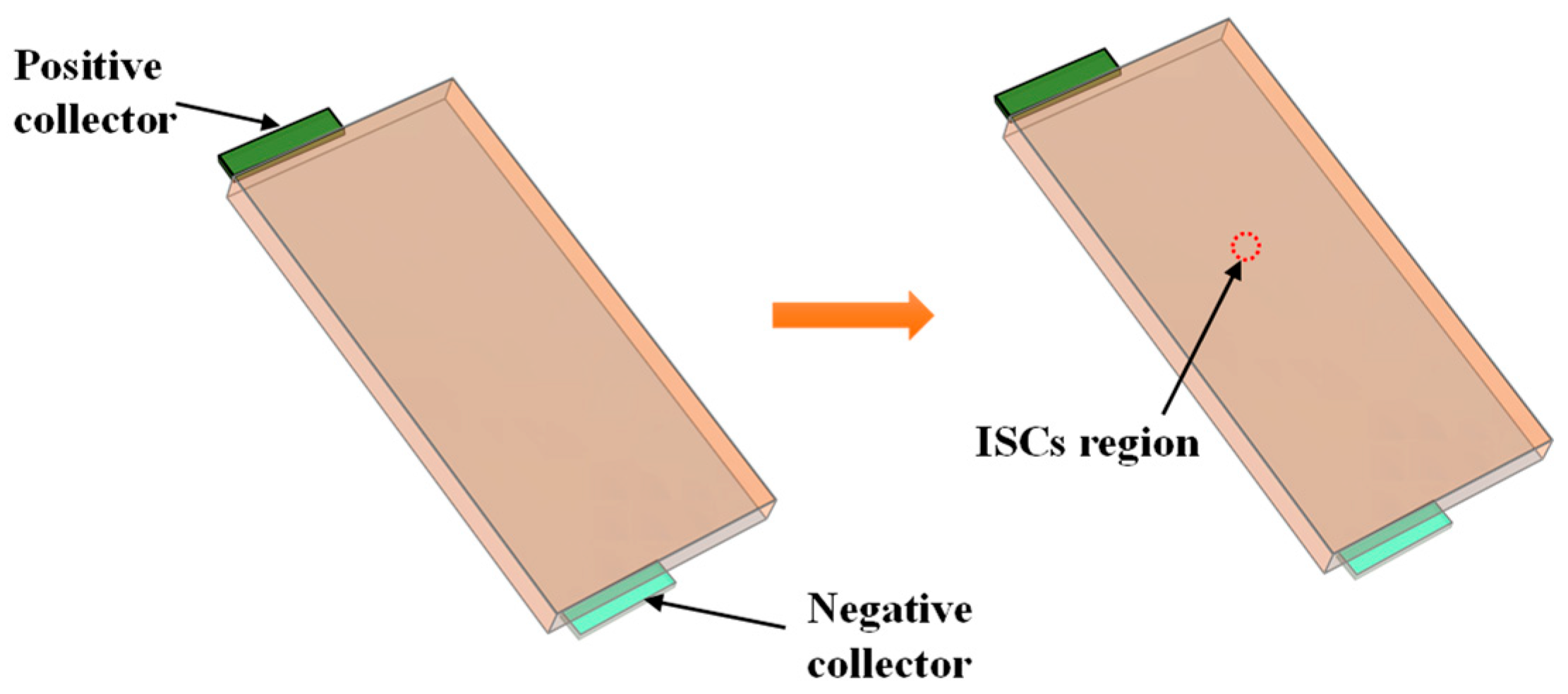

3.4. Electrochemical–Thermal–ISC Coupling Model

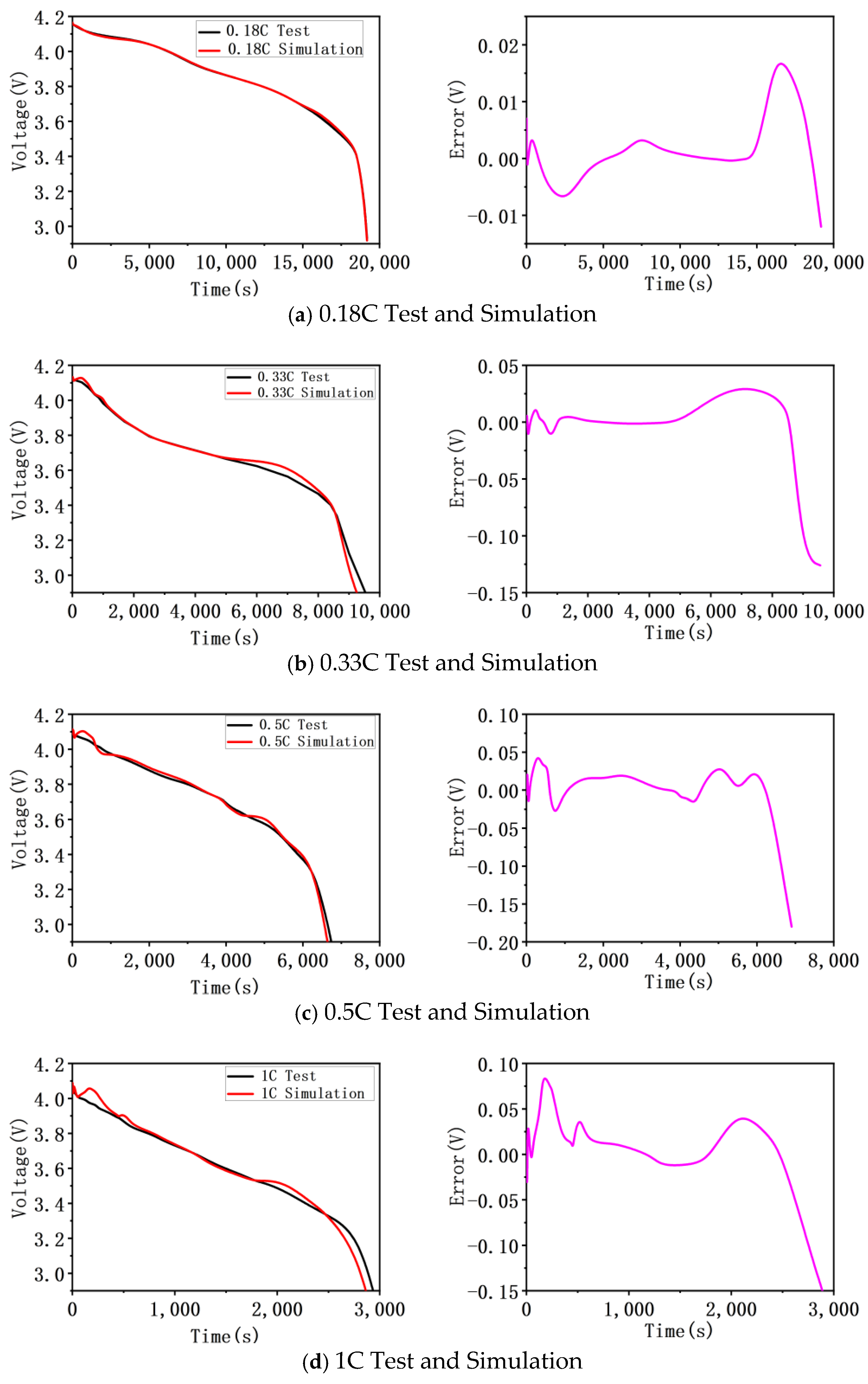

4. Model Validation

5. Datasets Acquisition

6. Methods for ISC Prediction and Results

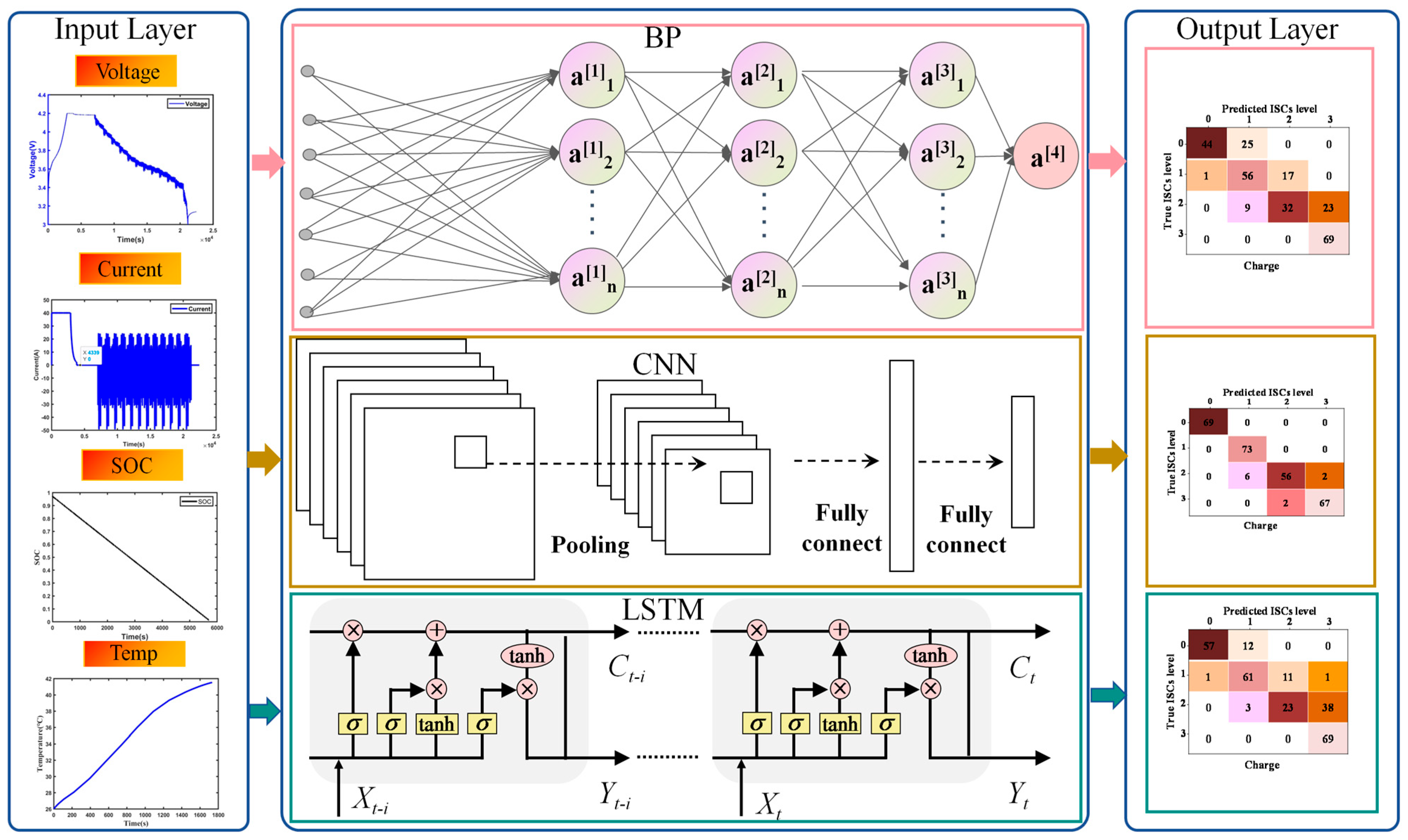

6.1. BP-CNN-LSTM ISC Prediction Model

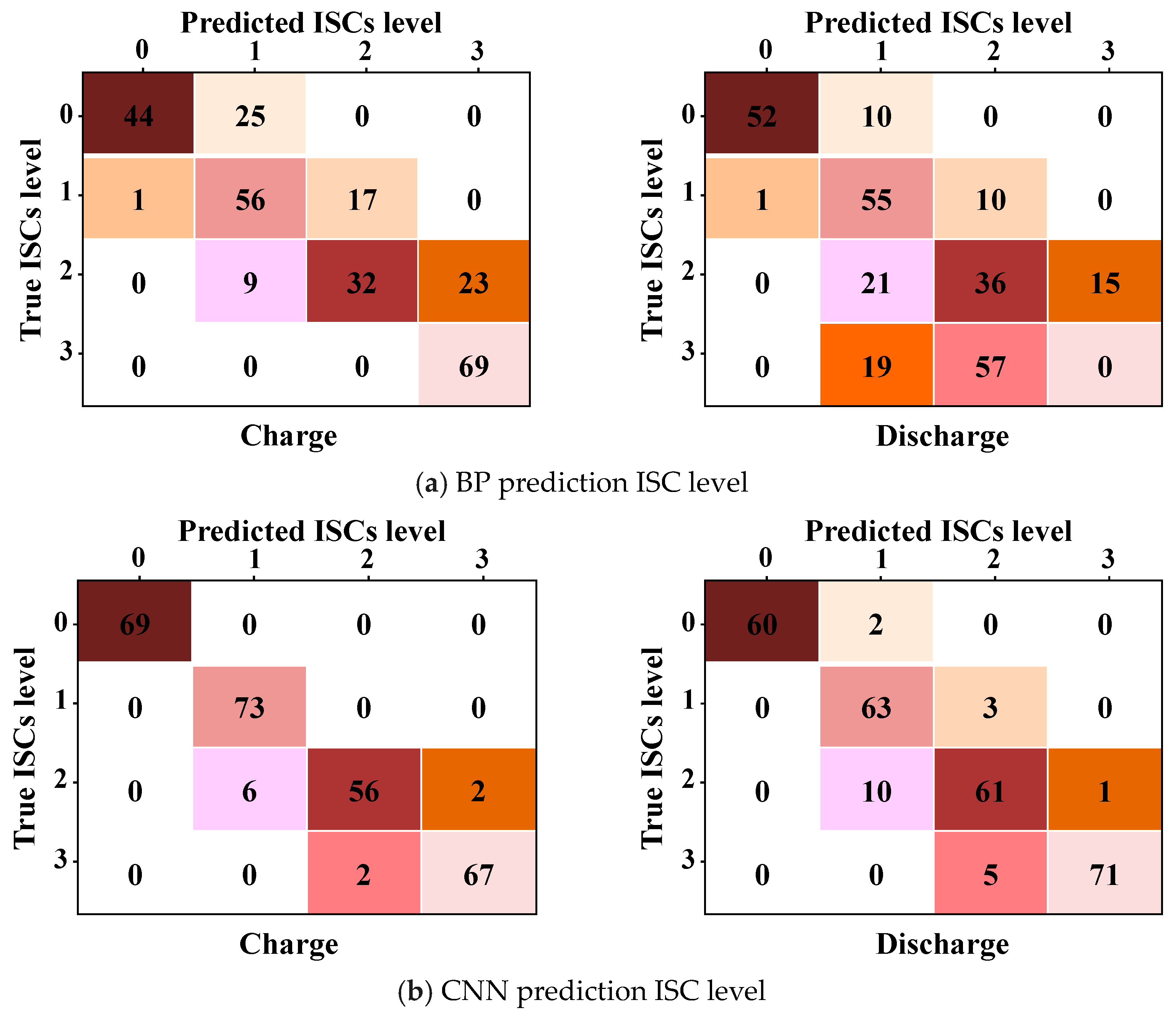

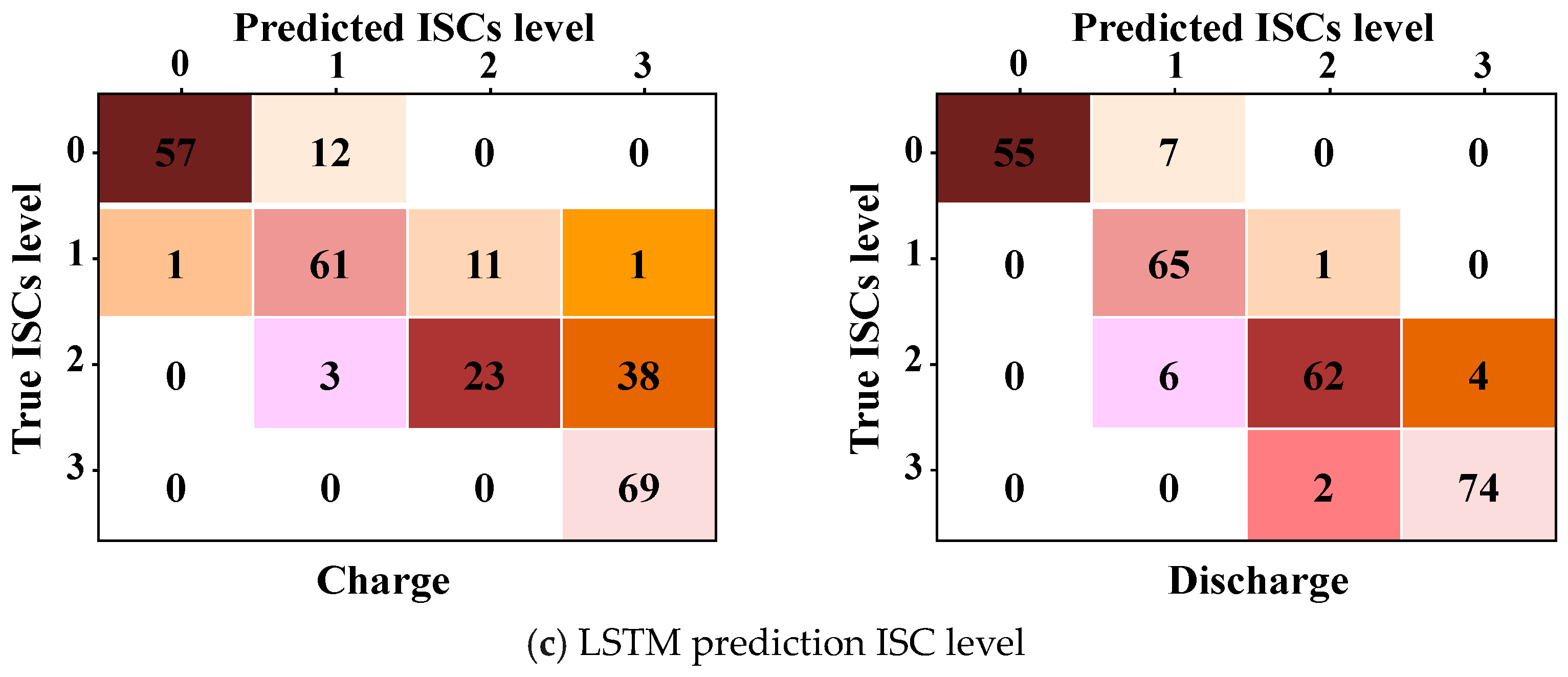

6.2. Prediction Results

6.3. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The transport mechanism of lithium ions in gelled electrolytes was analyzed. Lithium ions combine with the polymer matrix, and under external force, the polymer chains move. The mutual movement between chains facilitates the directional transport of lithium ions, enabling the normal operation of lithium batteries.

- (2)

- To address the difficulty of developing and implementing a large number of internal short circuit experiments due to the poor repeatability and controllability of traditional battery internal short circuit experiments, a three-dimensional finite element electrochemical–thermal–internal short circuit coupling model for lithium-ion batteries was established. This model replaces real internal short circuit experiments through simulation testing.

- (3)

- ISC prediction model for lithium-ion batteries has been established. The classification level of the severity of internal short circuits in batteries has been defined. ISC prediction model can provide unique insights that traditional simulations find difficult to capture, especially when dealing with complex, dynamic, or high-dimensional problems. It can detect a simulated fault and this modeling approach could be applied to empirical data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, S.; Guo, W.; Fu, Y. Advances in composite polymer electrolytes for lithium batteries and beyond. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2000802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wei, X.; Fan, W.; Jiang, B.; Lai, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tang, X.; Dai, H. Toward safe carbon-neutral transportation: Battery internal short circuit diagnosis based on cloud data for electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2022, 317, 119168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L. Voltage fault diagnosis and prognosis of battery systems based on entropy and Z-score for electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2017, 196, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Brancato, L.; Giglio, M.; Cadini, F. Temperature enhanced early detection of internal short circuits in lithium-ion batteries using an extended Kalman filter. J. Power Sources 2024, 591, 233874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, G.; Younes, H.; Hong, H.; Widener, C.; Hrabe, R.H.; Wu, J.J. Nanofluids as media for high capacity anodes of lithium-ion battery—A review. J. Nanofluids 2019, 8, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Kim, J.; Shen, W.; Lv, C.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, W.; Gao, B.; Guo, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Key technologies for electric vehicles. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2022, 1, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, W.; Lou, J. Carboxymethylated nanocellulose-based gel polymer electrolyte with a high lithium ion transfer number for flexible lithium-ion batteries application. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 132604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S.; Hamrahjoo, M.; Dehghani, E.; Salami-Kalajahi, M.; Eliseeva, S.N.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H. Semi-interpenetrated polymer networks based on modified cellulose and starch as gel polymer electrolytes for high performance lithium ion batteries. Cellulose 2022, 29, 3423–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, B.; Liu, B.; Sun, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, N. Single-Ion Gel Polymer Electrolyte Based on Poly (ether sulfone) for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yi, L.; Zou, C.; Liu, J.; Yu, J.; Zang, Z.; Tao, X.; Luo, Z.; Guo, X.; Chen, G. High-Performance Gel Polymer Electrolyte with Self-Healing Capability for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 5267–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Gong, X.; Mi, C.C.; Sun, F. A robust state-of-charge estimator for multiple types of lithium-ion batteries using adaptive extended Kalman filter. J. Power Sources 2013, 243, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; Weng, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Influence of current rate on the degradation behavior of lithium-ion battery under overcharge condition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Xie, S.; Ping, X.; Li, G.; He, J. The influence of overcharge and discharge rate on the thermal safety performance of lithium-ion battery under low air pressure. Ionics 2022, 28, 4653–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; Weng, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Sensitivities of lithium-ion batteries with different capacities to overcharge/over-discharge. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzweil, P.; Frenzel, B.; Scheuerpflug, W. A Novel Evaluation Criterion for the Rapid Estimation of the Overcharge and Deep Discharge of Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Differential Capacity. Batteries 2022, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wei, X.; Jiang, B.; Fan, W.; Lai, X.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, H. Quantitative Diagnosis of Internal Short Circuit for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Relaxation Voltage. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 13201–13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Seah, C.E. A Survey of Fault Detection, Isolation, and Reconfiguration Methods. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2010, 18, 636–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Plett, G.L.; Trimboli, M.S.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, T.; Zheng, Y. Pseudo-two-dimensional model and impedance diagnosis of micro internal short circuit in lithium-ion cells. J. Energy Storage 2020, 27, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.; Elmarakbi, A.; Elkady, M. Thermal runaway detection of cylindrical 18650 lithium-ion battery under quasi-static loading conditions. J. Power Sources 2017, 370, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Pan, Y.; He, X.; Wang, L.; Ouyang, M. Detecting the internal short circuit in large-format lithium-ion battery using model-based fault-diagnosis algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2018, 18, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.; Lang, H.; Kim, Y.; Hu, X.; Mu, B.; Lin, X. A Neural Network Based Method for Thermal Fault Detection in Lithium-Ion Batteries. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 4068–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Chowdhuri, S.; Williamson, S.S. Machine learning-based data-driven fault detection/diagnosis of lithium-ion battery: A critical review. Electronics 2021, 10, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghib, K.; Dubé, J.; Dallaire, A.; Galoustov, K.; Guerfi, A.; Ramanathan, M.; Benmayza, A.; Prakash, J.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C. Enhanced thermal safety and high power performance of carbon-coated LiFePO4 olivine cathode for Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2012, 219, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Jin, C.; Yi, W.; Han, X.; Feng, X.; Zheng, Y.; Ouyang, M. Mechanism, modelling, detection, and prevention of the internal short circuit in lithium-ion batteries: Recent advances and perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35, 470–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wei, X.; Tang, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Dai, H. Internal short circuit mechanisms, experimental approaches and detection methods of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 141, 110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Li, X.; Ma, M.N.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Mi, C. Case study of an electric vehicle battery thermal runaway and online internal short-circuit detection. IEEE Trans. Power Electron 2021, 36, 2452–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Khosravinia, K.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Lu, W. Lithium Plating Mechanism, Detection, and Mitigation in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2021, 87, 100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Gao, F.; Bu, X.-Y.; Chen, H.-S.; Quan, T.; Xu, Y.-B.; Jiao, Q.-J. Internal short circuit and thermal runaway evolution mechanism of fresh and retired lithium-ion batteries with LiFePO4 cathode during overcharge. Appl. Energy 2022, 328, 120224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez-Robles, D.; Azam, S.; Jeevarajan, J.A.; Mukherjee, P.P. Degradation-Safety Analytics in Lithium-Ion Cells and Modules Part II. Overcharge and External Short Circuit Scenarios. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 050535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wei, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Han, G.; Dai, H. Revealing the failure mechanisms of lithium-ion batteries during dynamic overcharge. J. Power Sources 2022, 543, 231867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Sun, W.; Yu, Q.; Sun, F. Research progress, challenges and prospects of fault diagnosis on battery system of electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, X.; Zhang, M.; Lu, L.; Han, X.; He, X.; Ouyang, M. Comparative study on substitute triggering approaches for internal short circuit in lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Charge/0.18 C | Charge/0.33 C | Charge/0.5 C | Charge/1 C | Temperature/1 C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | 0.0034 V | 0.018 V | 0.021 V | 0.025 V | 0.22 °C |

| ISC Rshort Range (Ω) | Level |

|---|---|

| Up to 315 | L0 |

| 41~315 | L1 |

| 4~41 | L2 |

| 0~4 | L3 |

| BP | Value | CNN | Value | LSTM | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| training dataset | 939 | training dataset | 939 | training dataset | 939 |

| validation dataset | 276 | validation dataset | 276 | validation dataset | 276 |

| layers | 2 | layers | 4 | layers | 5 |

| input neurons | 1836 | input neurons | 1836 | input neurons | 2115 |

| output neurons | 4 | output neurons | 4 | output neurons | 4 |

| Loss function | SCC | Loss function | MSE | Loss function | SCC |

| Optimizer | Adam | Optimizer | Adam | Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning rate | 1 × 10−3 | Learning Rate | 1 × 10−3 | Learning Rate | 1 × 10−4 |

| Batch size | 32 | Batch size | 32 | Batch size | 20 |

| Training cycle | 400 | Training cycle | 400 | Training cycle | 400 |

| BP | CNN | LSTM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH | DIS | CH | DIS | CH | DIS | |

| Accuracy () | 72.8% | 72.5% | 96% | 92.4% | 76.1% | 92.8% |

| Precision () | 74.7% | 84.8% | 98.8% | 97.7% | 76.3% | 95.3% |

| Recall () | 94.1% | 84.1% | 96.9% | 94.8% | 96.3% | 97.2% |

| F-value () | 82.9% | 83.5% | 97.8% | 96.1% | 83.8% | 96.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Ma, C.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Liao, C. Coupling Model and Early-Stage Internal Short Circuits Fault Diagnosis for Gel Electrolyte Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2026, 12, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020045

Wang L, Wu J, Ma C, Sun X, Wang L, Liao C. Coupling Model and Early-Stage Internal Short Circuits Fault Diagnosis for Gel Electrolyte Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries. 2026; 12(2):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020045

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Liye, Jinlong Wu, Chunxiao Ma, Xianzhong Sun, Lifang Wang, and Chenglin Liao. 2026. "Coupling Model and Early-Stage Internal Short Circuits Fault Diagnosis for Gel Electrolyte Lithium-Ion Batteries" Batteries 12, no. 2: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020045

APA StyleWang, L., Wu, J., Ma, C., Sun, X., Wang, L., & Liao, C. (2026). Coupling Model and Early-Stage Internal Short Circuits Fault Diagnosis for Gel Electrolyte Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries, 12(2), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12020045