1. Introduction

MXene represents a novel and rapidly growing family of two-dimensional (2D) transition-metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides [

1,

2], generally expressed by the formula M

n+1X

nT

x, which typically originate from etching processes such as acidic or molten salt treatment [

2]. Since the initial synthesis of layered Ti

3C

2T

x in 2011 through the selective etching of the A-layer element in MAX phases [

1], MXenes have become a research hotspot. The layered structures and the presence of surface terminal groups (T

x, such as –O, –OH, –F, etc.) derived from etching endow these materials with a unique combination of metallic-level conductivity (10

4 S·cm

−1–10

5 S·cm

−1), excellent mechanical flexibility, and intrinsic hydrophilicity [

3]. Compared to other 2D materials such as highly conductive but surface-inert graphene, or semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) with low inherent conductivity, MXenes offer the distinct advantage of combining metallic conductivity with tunable surface chemistry [

4], making them promising candidates for diverse applications. For example, MXenes have demonstrated high specific capacitance and rapid ion transport in supercapacitors and Li/Na ion batteries [

5], served as efficient supports for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution, oxygen reduction, and CO

2 reduction [

6], and acted as effective adsorbents for the removal of heavy metal ions and organic pollutants from water [

7]. Furthermore, their exceptional electromagnetic shielding ability and mechanical flexibility render MXenes particularly attractive for applications in wearable electronics, sensors, and electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding materials [

8].

Among MXenes, Ti

3C

2T

x is the most extensively studied material, particularly for high-power energy storage systems such as supercapacitors. Its structure consists of highly conductive Ti–C layers and hydrophilic surfaces [

2,

3], enabling rapid electron transport and efficient ion diffusion, which leads to a high specific capacitance. The charge storage mechanism of Ti

3C

2T

x often involves intercalation pseudocapacitance, which allows reversible intercalation of various cations (e.g., Li

+, Na

+) accompanied by charge-transfer reactions, significantly enhancing energy storage density [

9] compared to conventional electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs). Aqueous electrolytes (e.g., H

2SO

4, KOH, Na

2SO

4) are widely used due to their high ionic conductivity (>0.1 S·cm

−1) [

10] and power output. In an acidic H

2SO

4 electrolyte, the small, highly mobile hydrated protons reversibly intercalate into the Ti

3C

2T

x interlayers [

11], enabling high volumetric capacitance and excellent rate performance. For instance, Lukatskaya et al. reported a volumetric capacitance of 900 F·cm

−3 for Ti

3C

2T

x with a high retention rate in 1 M H

2SO

4 [

12]. However, acidic environments can lead to surface corrosion and degrade structural integrity after prolonged cycling [

13]. More importantly, despite the promising theoretical prospects, maximizing the performance of MXene, especially at high-rate operation, remains fundamentally constrained by interfacial charge-transfer inefficiencies where proton and ion transport become kinetically limited.

While non-aqueous electrolytes offer a broader electrochemical stability window, which is critical for enhancing energy density [

12], they often come with trade-offs. Organic electrolytes are limited by their lower ionic conductivity and larger solvent molecules, leading to sluggish intercalation kinetics [

14]. Ionic liquids, despite offering outstanding chemical and thermal stability, typically exhibit high viscosity and low ion mobility [

15]. To overcome these limitations and enhance energy density without sacrificing power, integrating redox-active electrolytes has become a key strategy. Ascorbic acid (AA), a water-soluble and biocompatible organic molecule, represents a highly promising candidate. It exhibits unique reversible redox activity via its enediol structure, undergoing reversible oxidation to dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) [

16]. Its low oxidation potential makes AA an ideal probe molecule for investigating charge-transfer behavior, conductivity, and catalytic activity on the surface of electrode materials [

17]. In electrochemical energy storage, AA can act as a functional electrolyte or additive, enhancing pseudocapacitive contribution [

18] and increasing the energy density of the storage device. However, the inherently larger molecular size of AA compared to simple protons, along with its susceptibility to surface-induced side reactions, frequently leads to diffusion bottlenecks and unstable reaction pathways when interfacing with MXene surfaces.

Surface modification is thus a critical strategy for precisely tuning the interfacial properties and electronic structure of MXenes [

2,

3]. Notably, when a molecular redox electrolyte such as AA is employed, the electrolyte is no longer a passive medium; instead, the electrode surface must be engineered to match the interfacial charge-transfer and mass-transport requirements of the redox-active molecules. In this context, nitrogen (N

2) plasma surface engineering has emerged as a powerful and low-damage route to reconstruct the outermost atomic layers. This treatment utilizes high-energy nitrogen species to interact with the MXene surface, effectively introducing the desired nitrogen-doped atoms or nitrogen-containing functional groups (e.g., –NH

2, O–Ti–N, Ti–O–N) while simultaneously removing detrimental fluorine-containing (–F) groups, thereby enhancing surface polarity and electronic structure [

19]. This chemical modification approach promotes interfacial affinity with electrolyte ions and enhances pseudocapacitive contributions. For instance, Zhang et al. reported that nitrogen-doped Ti

3C

2T

x exhibited a high specific capacitance of up to 415 F·g

−1 in 1 M H

2SO

4 and maintained over 90% capacity after 18,000 cycles [

20]. However, the key hypothesis of the present study is that, under AA electrolyte conditions, plasma duration functions as a kinetic dial that regulates the MXene–AA interfacial charge-transfer pathway and mitigates diffusion bottlenecks/side reactions that are more pronounced for molecular redox species than for simple ions. Accordingly, an optimized plasma duration is expected to actively modulate the complex MXene-AA interfacial environment, thereby accelerating charge transport and enhancing surface-controlled charge storage, which is necessary to suppress the side reactions and diffusion constraints typical in molecularly active electrolytes.

Based on the above background and hypothesis, this study aims to systematically explore the effects of N2 plasma treatment duration on the electrochemical performance of multilayer Ti3C2Tx electrodes and supercapacitors. The modified Ti3C2Tx films were evaluated in two different aqueous systems: a 3 M H2SO4 solution (as a reference benchmark), and a 500 μM AA solution (as the target redox-active electrolyte). Through a complementary approach utilizing electrochemical analysis, including cyclic voltammetry (CV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and kinetics assessment (b value analysis), along with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for surface composition confirmation, this work establishes a mechanistically explainable strategy. The resulting insights clarify why moderate plasma activation can simultaneously enhance interfacial kinetics in AA while preserving the conductive Ti–C framework, thereby informing the design of high-rate supercapacitors and electrolyte-sensitive electrochemical systems.

3. Results and Discussion

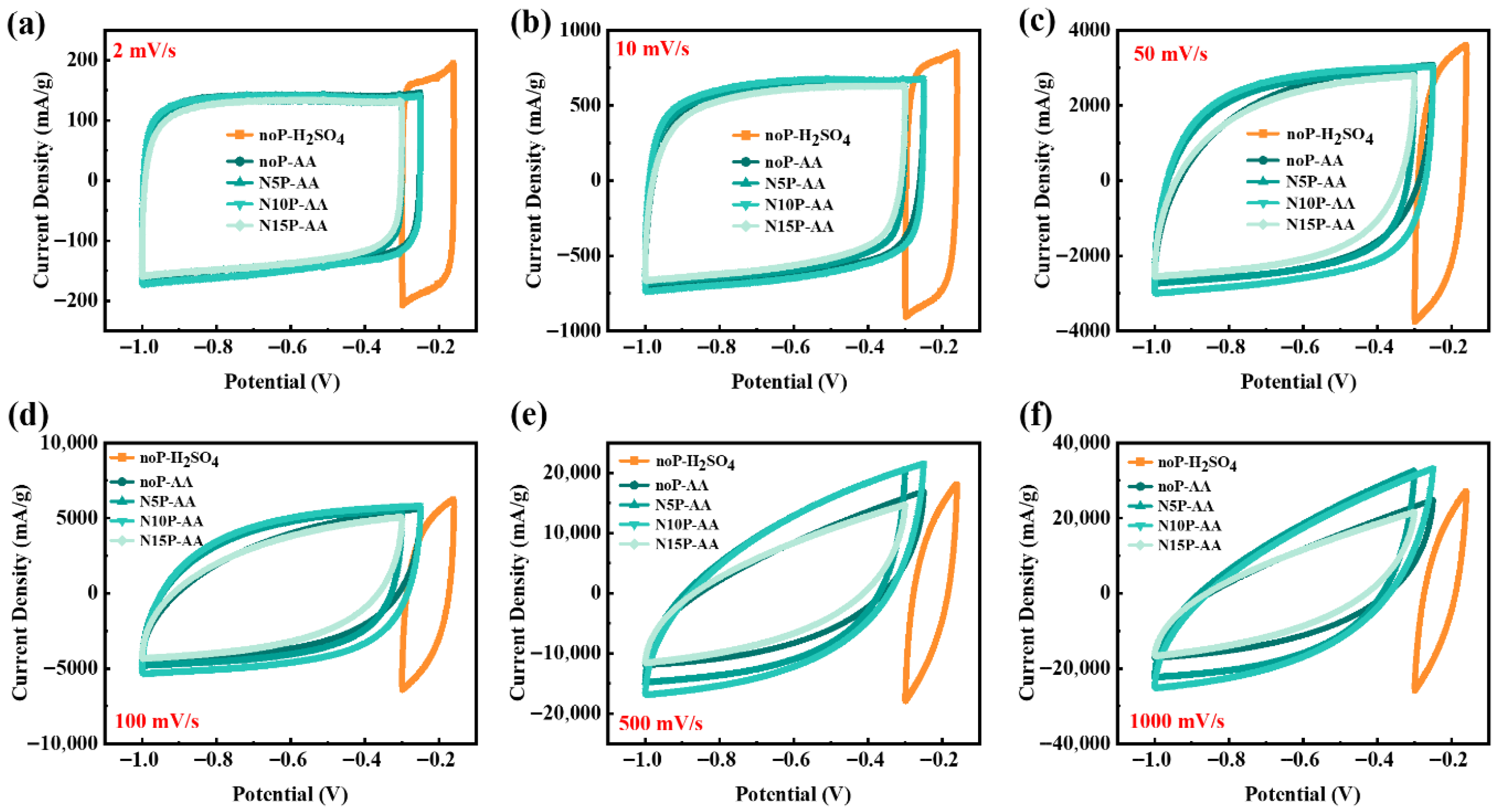

The electrochemical behavior of multilayer Ti

3C

2T

x electrodes with and without nitrogen plasma modification was compared and evaluated by CV in 3 M H

2SO

4 and 500 μM AA electrolytes at different scan rates. As shown in

Figure 1a, the unmodified Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitor in 3 M H

2SO

4 exhibits an extremely narrow stable potential window of approximately 0.14 V (−0.30 V to −0.16 V), which is likely restricted by hydrogen evolution and/or oxidation reactions. In contrast, owing to its neutral to weakly acidic nature and less stringent redox potential constraints, the AA electrolyte significantly extends the stable potential window to approximately 0.7 V. Although AA is redox-active, under our conditions (500 µM AA in 10× PBS on a multilayer Ti

3C

2T

x film), its faradaic contribution may not appear as distinct peak pairs. Instead, it can contribute as a broadened, pseudocapacitive-like current superimposed on electric double-layer capacitance (EDLC), leading to near rectangular CVs despite the enlarged current response and widened potential window relative to H

2SO

4. Although H

2SO

4 provides high ionic conductivity, the excessive proton concentration can accelerate oxidation or hydrogen evolution at the Ti

3C

2T

x surface, particularly when the applied voltage is close to the decomposition potential of water.

Figure 1a,b show that at the scan rates of 2 mV·s

−1 and 10 mV·s

−1, the CV curves of various Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitors treated under different plasma conditions all resemble blunt-rounded rectangles, indicating that charge storage mechanism is primarily EDLC accompanied by some surface pseudocapacitance contributions. At these low scan rates, both the device without plasma treatment (noP-AA) and the device treated with nitrogen plasma for 10 min (N10P-AA) display superior performance; even the unmodified electrode maintains sufficient ion/electron exchange, resulting in a CV area comparable to that of N10P-AA. With increasing scan rate, the CV curves gradually evolve from rectangular to spindle-like shapes, accompanied by larger current responses and more pronounced potential hysteresis, indicating that charge-transfer kinetics and ion diffusion become rate-limiting. As shown in

Figure 1e,f, at the high scan rates of 500 mV·s

−1 and 1000 mV·s

−1, the current difference between devices caused by different plasma treatment conditions becomes more pronounced. N10P-AA consistently retains the largest CV area and a faster ion response, demonstrating superior rate capability. In contrast, N15P-AA exhibits a performance decline under certain conditions, which can be attributed to over-etching that induces structural damage and conductivity loss. Meanwhile, noP-H

2SO

4 exhibits the smallest CV curve area with a different shape, reflecting the poorest rate performance.

Nitrogen plasma treatment introduces surface functionalities such as pyridinic N, pyrrolic N, and graphitic N, while simultaneously removing surface contaminants and altering oxide states. The modification increases the density of active sites, enhances pseudocapacitance contributions, and improves wettability and conductivity, thereby facilitating charge transport. The optimized nitrogen plasma duration of 10 min strikes a balance between the number of active sites and the integrity of the conductive network, enabling higher current output and a wide potential window even at high scan rates. Additionally,

Figure 1d–f reveal that electrolyte composition significantly influences electrochemical behavior. The devices operated in the 500 μM AA solution display markedly larger currents than those in H

2SO

4, presumably attributed to the participation of AA molecules in reversible Faradaic reactions and the enhanced surface pseudocapacitance. However, the chemical activity of AA may also trigger irreversible side reactions, potentially compromising long-term stability and necessitating further testing and verification. Based on the results in

Figure 1, it has been confirmed that nitrogen plasma modification is beneficial for improving the potential window and rate capability of Ti

3C

2T

x electrodes and supercapacitors, with N10P identified as the optimal plasma treatment condition. Notably, the performance enhancement does not scale linearly with plasma duration. Prolonged treatment can inhibit performance improvement, suggesting the need to optimize treatment parameters for optimal results in practical applications. An appropriate nitrogen plasma treatment balances introducing active sites and retaining conductivity, thus enabling higher energy storage performance over a wider potential window and at a high scan rate.

As displayed in

Figure 2a, all Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitors exhibit nearly 100% coulombic efficiency at low scan rates (2 mV·s

−1 to 10 mV·s

−1). This indicates a high charge utilization efficiency, as ions have sufficient time to react completely at the electrode surfaces under slow charge–discharge conditions. However, as the scan rate increases to 10,000 mV·s

−1, coulombic efficiency drops significantly. This reduction is most pronounced for the untreated device using the 3 M H

2SO

4 electrolyte (noP), where the efficiency sharply declines below 40%. In contrast, the nitrogen plasma-treated supercapacitors using the AA electrolyte (N5P, N10P, and N15P) maintain relatively high coulombic efficiencies (>72%) at high scan rates, demonstrating that nitrogen plasma treatment effectively improves the reversibility of the Ti

3C

2T

x electrodes during rapid charge–discharge cycles.

Figure 2b presents the rate capability for all Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitors. The nitrogen plasma-treated devices consistently outperform untreated ones, particularly in the medium to high scan rate range (100 mV·s

−1 to 1000 mV·s

−1), indicating their better electrochemical kinetics. The phenomenon can be attributed to introducing nitrogen-containing functional groups and surface defects during nitrogen plasma treatment, which enhances interfacial polarization and electronic conductivity, thereby reducing the ion transport impedance under high-rate conditions. Additionally, the rate capability curves of N10P-AA and N15P-AA are flatter than that of N5P-AA, suggesting that extending the nitrogen plasma treatment duration can further optimize surface chemical properties and pore structures, contributing to high-rate capability.

Figure 2c shows the corresponding specific capacitance results supporting the above observations. At low scan rates, the noP-H

2SO

4 supercapacitor exhibits the highest initial specific capacitance (approximately 120 F·g

−1), but it decays most rapidly with increasing scan rate. This indicates that while an acidic environment enhances the energy storage at low rates, it limits the cycling stability at high rates. Conversely, while N10P-AA and N15P-AA exhibit slightly lower specific capacitances at lower rates (approximately 100 F·g

−1), their capacitance retention at high rates is better, implying the effectiveness of nitrogen plasma treatment in enhancing both long-term cycling tolerance and high-rate charge and discharge adaptability. The results in

Figure 2 confirm that nitrogen plasma modification can improve the electrochemical stability of Ti

3C

2T

x under high rates and the overall performance across different scan rates.

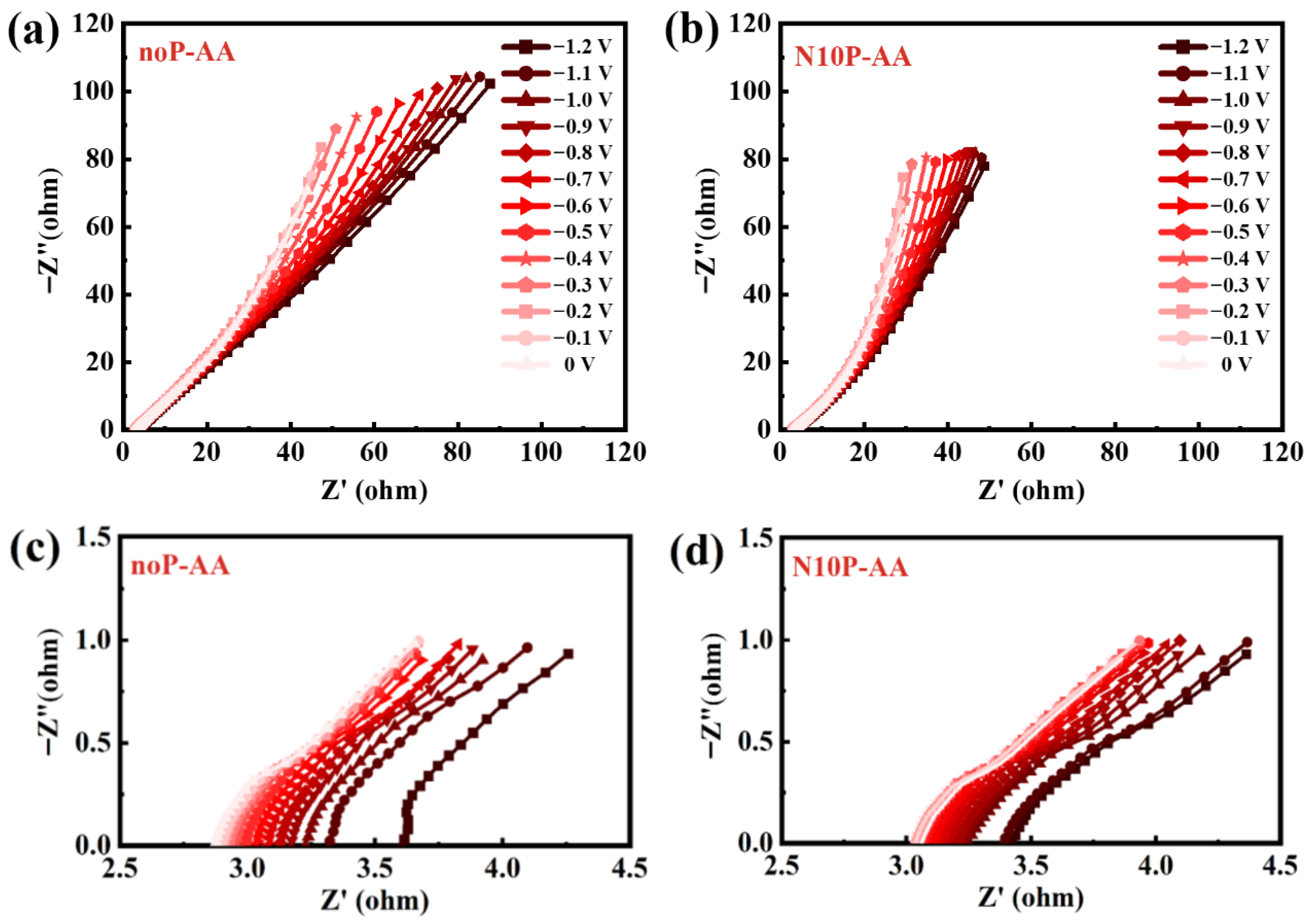

EIS results further elucidate the influences of bias potential and plasma treatment. As seen in

Figure 3a,b, the slope of the low-frequency tail in the Nyquist plot gradually flattens and shifts toward 45° as the applied bias becomes more negative. This reflects that the real impedance (Z′) and imaginary impedance (Z″) become more equivalent, indicating that the system is gradually controlled by ion diffusion limitation. At more negative voltages (−0.8 to −1.2 V), a reduction reaction occurs on the Ti

3C

2T

x surface, rapidly oxidizing AA to DHA, resulting in a rapid depletion of AA and a steep concentration gradient between the electrode surface and the electrolyte. The system enters a diffusion-controlled regime since the diffusion rate cannot keep up. On the contrary, when a more positive voltage is applied (close to 0 V), the low-frequency tail of the Nyquist plot goes more vertical, signifying a more capacitive behavior with more efficient mass transport to the electrode surface. At this time, the reactants can more effectively diffuse and replenish the electrode surface, preventing the formation of a concentration gradient and thus avoiding a diffusion-limited regime. Thanks to the high conductivity and large specific surface area of Ti

3C

2T

x, the electrode exhibits supercapacitor-like behavior, and the interfacial electrochemical reaction is primarily surface-controlled.

Figure 3c shows that for the untreated Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitor noP-AA, the semicircle in the high-frequency region gradually increases as the bias sweeps from 0 V to −1.2 V, indicating a rise in charge-transfer impedance (R

CT).

Figure 3d demonstrates that N10P-AA obtained by 10-min nitrogen plasma modification exhibits a similar trend. However, its overall R

CT is lower than that in noP-AA, indicating that nitrogen plasma treatment can reduce R

CT and enhance electron transfer ability. This finding aligns with the aforementioned CV results, where N10P-AA caused a larger current and lower polarization potential, revealing its higher conductivity and more effective interfacial reaction kinetics compared to noP-AA. These also demonstrate that the appropriate nitrogen plasma modification promotes electrode surface activation and accelerates AA redox kinetics. The Nyquist plots in

Figure 3 obtained from EIS analysis have clearly shown that nitrogen plasma treatment effectively reduces R

CT across the entire bias voltage range and mitigates the impact of diffusion limitations at high bias voltages. These findings underscore the potential of nitrogen plasma-modified MXenes for future electrochemical energy storage and biosensing applications.

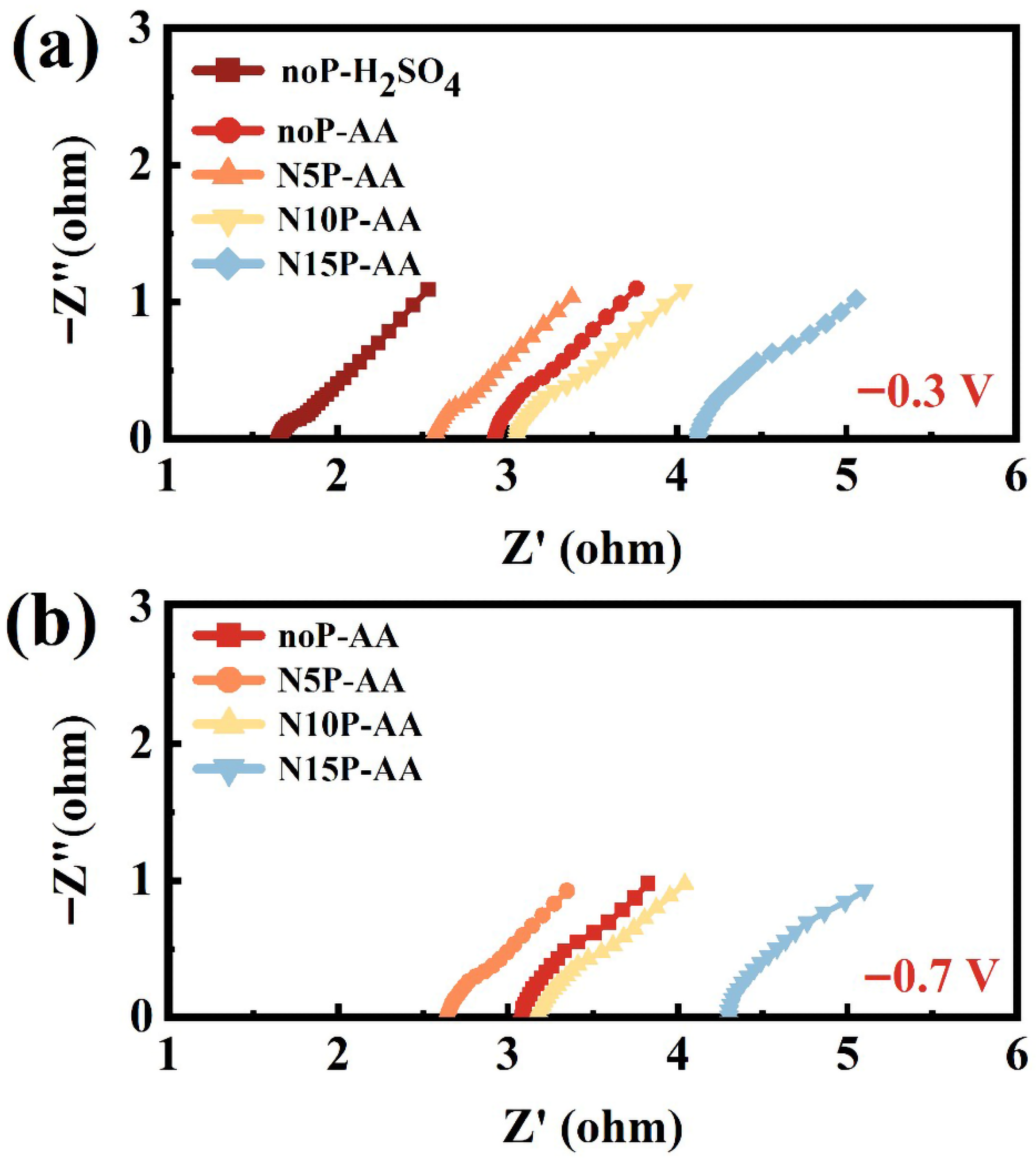

Figure 4 presents the magnified high-frequency regions of the Nyquist plots for Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitors under different plasma treatment conditions at the applied bias voltages of −0.3 V and −0.7 V. The intercept on the real axis corresponds to the series resistance (R

s), while the semicircle diameter reflects the magnitude of R

CT. As shown in

Figure 4a, under −0.3 V, the untreated device in H

2SO

4 (noP-H

2SO

4) exhibits the smallest R

s (approximately 1.8 Ω), primarily due to the high ionic conductivity of the protonic acid electrolyte. In comparison, the noP-AA device displays a larger R

s and a larger semicircle, indicating an increased R

CT.

Figure 4a,b show that with an increasing nitrogen plasma treatment duration, the Nyquist plot gradually shifts towards a higher real impedance, corresponding to an increase in R

s. As shown in

Figure 4b, under −0.7 V, the plots shift further to the right relative to those at −0.3 V in

Figure 4a, reflecting a more substantial polarization effect at a more negative potential, leading to increases in both R

s and v. N10P-AA maintains a relatively minor R

CT, highlighting its better interfacial charge-transfer capability across different operating bias voltages. By contrast, N15P-AA exhibits the largest R

s and R

CT, again confirming that excessive nitrogen plasma treatment can deteriorate charge transport. Collectively, N10P-AA achieves an optimal balance of Rs and a consistently low R

CT in the AA electrolyte across different operating bias voltages, thus delivering the most favorable energy-storage characteristics.

The magnitude of the bias voltage also pronouncedly influences diffusion behavior. As the applied bias shifts from negative to less negative (−1.0 V to −0.3 V), the Warburg slope consistently decreases for all Ti3C2Tx supercapacitors. This trend can be attributed to the physicochemical changes at the electrode/electrolyte interface. The variation in bias voltage alters the local electric field intensity and the structure of the electrical double layer near the electrode surface. Under a more negative potential (e.g., −1.0 V), more negative charges are on the electrode surface, exerting a stronger electrostatic interaction on the electrolyte ions and thereby increasing the diffusion resistance. As the potential becomes less negative, the electric field on the electrode surface weakens, reducing electrostatic hindrance, facilitating ion diffusion, and improving transport efficiency. During this process, the electrochemical behavior in the system gradually transits from being diffusion-limited towards being more surface-controlled, exhibiting a more capacitance-dominated behavior. Furthermore, the change in bias potential not only affects the diffusion process but also the activation energy of the electrochemical reactions. At more favorable potentials (e.g., −0.3 V), faster charge-transfer kinetics can more effectively sustain the concentration gradients at the interface and accelerate diffusion, reducing Warburg impedance.

The findings in

Figure 5 highly align with the preceding CV and EIS results. The relatively minor Warburg slope observed for N10P-AA indicates that ions can be rapidly replenished at the reaction interface during fast surface reactions, effectively avoiding diffusion bottlenecks. This explains its ability to maintain a larger CV curve area and high current density at high scan rates. In contrast, N15P-AA exhibits larger Warburg slopes across all potentials, in agreement with its larger R

CT observed in its Nyquist plots. These suggest that both electron transport and mass transfer are limited, accounting for its inferior CV performance. A particularly noteworthy observation is shown in

Figure 5c at −0.3 V, where the untreated noP-H

2SO

4 device exhibits the smallest Warburg slope among all Ti

3C

2T

x supercapacitors in this study, indicating that its interfacial behavior is closest to that of an ideal electric double-layer capacitor. This finding contrasts sharply with the large slope observed for noP-AA using the AA electrolyte. It is then inferred that while the pristine Ti

3C

2T

x surface possibly provides a highly efficient ion diffusion pathway in a simple proton (H

+) ion system, it is not conducive to ion transport when larger and more complex active species like AA are introduced. This underscores the critical role of nitrogen functionalities or microstructures, introduced by moderate nitrogen plasma treatment, in enhancing the diffusion efficiency of specific active species. Nevertheless, this optimization effect strongly depends on the electrochemical environment. Taken together, the analysis reconfirms that a nitrogen plasma treatment duration of 5 min to 10 min can be considered the optimal time window for Ti

3C

2T

x, as it strikes a balance between generating sufficient active sites and preserving the integrity of the conductive substrate. However, its practical benefits still need further verification for different application systems.

To further clarify the effect of nitrogen plasma treatment on the charge storage mechanism of Ti3C2Tx supercapacitors, the b values were calculated by fitting the logarithmic relationship between scan rate and peak current. A b value closer to 1 indicates more surface-controlled behavior, whereas a b value closer to 0.5 reflects more diffusion-controlled processes. Here, “surface-controlled” refers to the dominance of near-surface charge storage kinetics (i ∝ vb), rather than requiring rapid long-range diffusion of AA into deep MXene interlayers. Although AA is bulkier than protons, its contribution in this system is mainly interfacial/surface-mediated, and moderate N2-plasma activation lowers the interfacial electron transfer barrier by introducing polar terminations/active sites, thereby strengthening the surface kinetic contribution reflected by higher b values. The b values of noP-H2SO4, noP-AA, N5P-AA, N10P-AA, and N15P-AA were 0.71, 0.74, 0.81, 0.79, and 0.73, respectively. All are within the range of 0.7 to 0.8, indicating that their charge storage involves both surface- and diffusion-controlled contributions, with surface effects being dominant. The lowest b value of noP-H2SO4 suggests a greater reliance on proton diffusion at the electrode surface and between layers. The use of AA raises the b value to 0.74 (noP-AA), reflecting the contribution from the surface redox reactions of AA. Nitrogen plasma treatment further increases the b values to 0.81 (N5P-AA) and 0.79 (N10P-AA), demonstrating that nitrogen functional groups enhance surface polarity and electrolyte wettability, and generate more active sites, thereby strengthening surface-controlled behavior. In contrast, prolonged treatment reduces the b value to 0.73 (N15P-AA), likely due to structural degradation and defect accumulation from over-etching, which impede ion/electron transport and shift the mechanism toward diffusion control. Overall, AA combined with moderate nitrogen plasma treatment can effectively reinforce the surface-controlled properties of Ti3C2Tx electrodes, while excessive plasma treatment damages their electrochemical activity.

The b-value trend aligns well with the Warburg analysis of mass transport. Therefore, b value mainly reflects kinetic control near the interface, whereas the Warburg slope reflects mass transport limitation. noP-H2SO4 exhibits the smallest Warburg slope, indicating faster ion replenishment and minimal diffusion resistance in the protonic electrolyte. By contrast, noP-AA exhibits a larger b value and a markedly larger Warburg slope, reflecting hindered ion transport caused by the bulkier and more complex AA molecules. The large b values of N5P-AA and N10P-AA combine with their lowest Warburg slopes, confirming that nitrogen plasma treatment improves wettability and ion transport efficiency by introducing nitrogen functionalities and tailoring surface structure, thus increasing the contribution from surface-controlled processes. Conversely, N15P-AA exhibits a reduced b value and a larger Warburg slope, indicating accumulated defects and transport limitations that deteriorate its electrochemical performance. These results jointly provide quantitative evidence that moderate nitrogen plasma treatment can optimize the kinetic control mechanism of Ti3C2Tx electrodes, reaffirming its importance in achieving more efficient, surface-dominated charge storage.

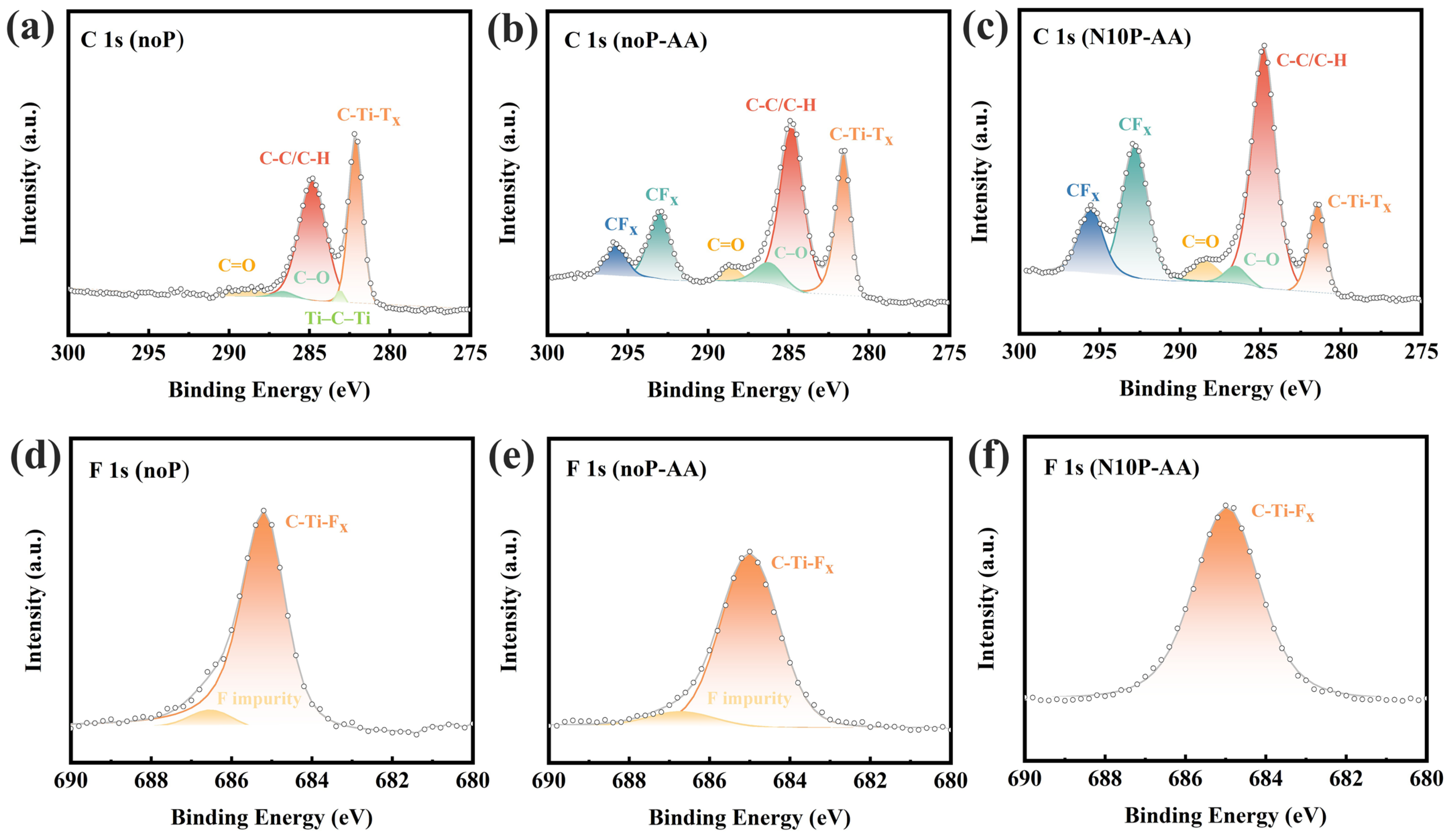

XPS analysis was also conducted to examine the C 1s, O 1s, F 1s, and Ti 2p spectra, aiming to elucidate the evolution of surface chemistry in Ti

3C

2T

x electrodes before and after nitrogen plasma treatment, and compare with the aforementioned electrochemical results for verification. As displayed in

Figure 6a, the pristine Ti

3C

2T

x exhibits mainly two characteristic peaks at approximately 282.0 eV (C–Ti–T

x) and 284.8 eV (C–C/C–H), indicating structural integrity with negligible contributions from C–O or C=O bonds [

21]. As shown in

Figure 6b, after electrochemical cyclings in AA, both the electrodes of noP-AA and N10P-AA exhibit CF

x peaks (290.0 eV to 298.0 eV) and intensified C–O (~286.9 eV) and C=O (~288.8 eV) signals, demonstrating surface oxidation and the participation of fluorine species in reactions during the cyclings [

21]. A comparison of the C–Ti–T

x peaks reveals the highest intensity for pristine Ti

3C

2T

x and the lowest intensity for N10P-AA, which can be attributed to high-energy ion bombardment during plasma treatment that disrupted Ti–C bonds, generated more adventitious carbon (C–C/C–H), and possibly induced passivation layer formation or altered oxidation kinetics, thereby suppressing excessive oxidation. As shown in

Figure 6c, nitrogen plasma treatment also introduces new carbonaceous structures on the electrode surface of N10P-AA. These changes are highly consistent with the aforementioned electrochemical results, that is, the passivation layer in N10P-AA protected its electrode surface. It enabled higher conductivity and rate capability, particularly at high scan rates. As shown in

Figure 6d, the F 1s spectra exhibit a dominant peak at approximately 685.0 eV corresponding to C–Ti–F

x bonds and a weak peak at 686.5 eV to 688.7 eV assigned to fluorine impurities [

21]. As seen in

Figure 6e,f, after electrochemical cyclings in AA, the impurity peak is markedly attenuated, suggesting the reductive effect of AA removes unstable fluorine species. Notably,

Figure 6f shows that the 10-min nitrogen plasma treatment effectively eliminates fluorine-containing impurities on the electrode surface of N10P-AA, helps reconstruct the surface, and reduces surface defects.

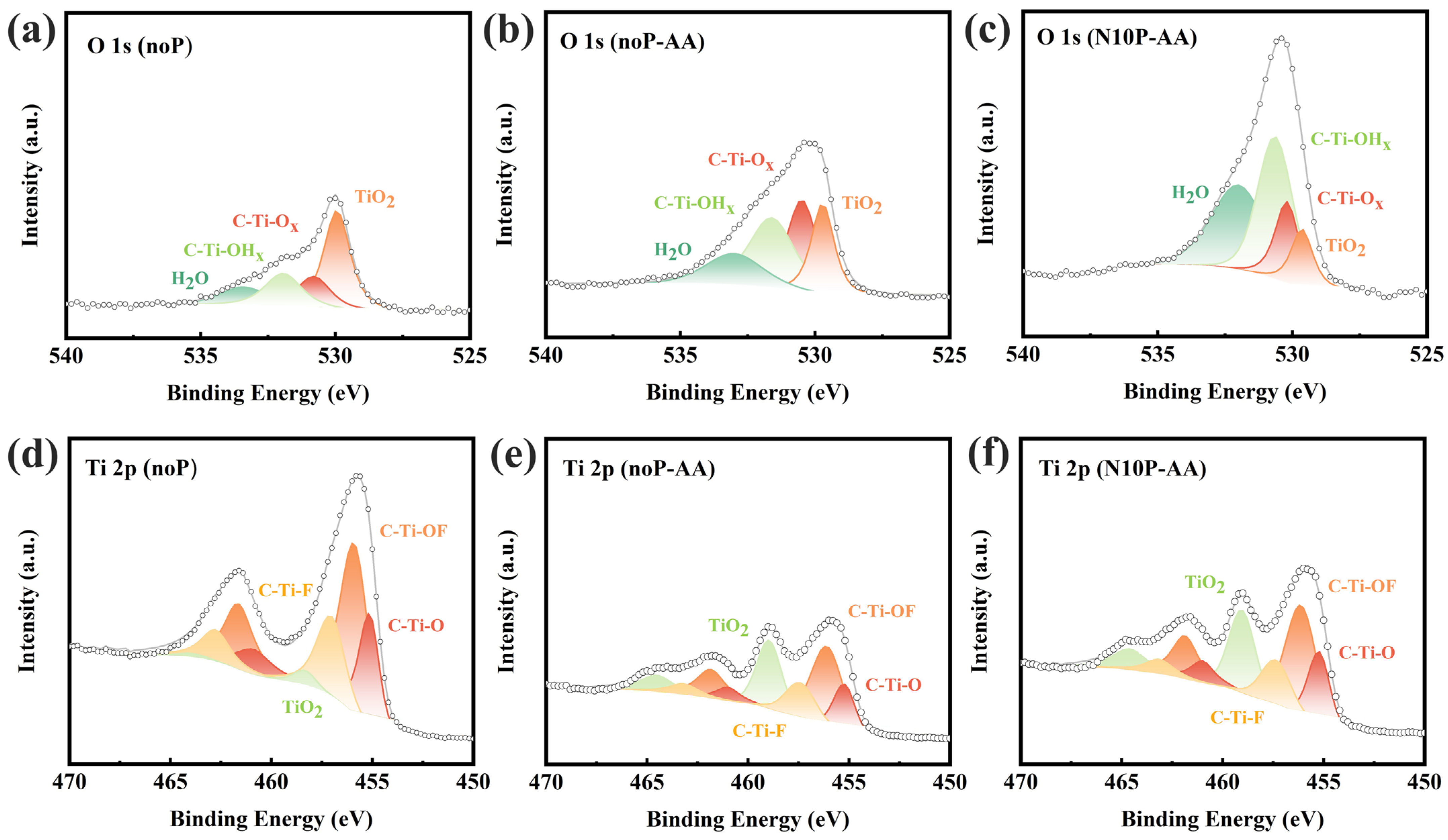

As displayed in

Figure 7a–c, the O 1s spectra comprising the peaks of TiO

2 (529.9 eV), C–Ti–O

x (530.8 eV), C–Ti–OH

x (531.9 eV), and H

2O (533.4 eV), provide more insights into the evolution of surface functional groups [

21].

Figure 7a reveals that the pristine Ti

3C

2T

x contains more TiO

2 on its surface. As shown in

Figure 7b, after electrochemical cyclings in AA, the peak intensity of TiO

2 on the electrode surface of noP-AA weakens while that of C–Ti–O

x slightly increases, indicating that AA, as a strong reducing agent, removes part of the unstable oxide layer and generates more stable hydroxyl terminal groups (C–Ti–OH

x and –OH). As revealed in

Figure 7c, the TiO

2 signal intensity on the electrode surface of N10P-AA is even smaller after 10-min nitrogen plasma treatment, and the C–Ti–OH

x signal intensity becomes relatively larger, strongly indicating that nitrogen plasma promotes surface hydroxylation and mitigates excessive Ti oxidation/passivation during cycling. The hydroxyl terminations impart excellent hydrophilicity and provide more adsorption and proton-buffering sites, contributing to enhanced capacitance and ion diffusion. The findings from

Figure 6d–f and

Figure 7a–c correlate well with those from CV, EIS, and Warburg analysis, confirming that the Ti

3C

2T

x electrode of N10P-AA possesses more stable and electrochemically favorable surface functional groups.

Figure 7d–f presents the Ti 2p spectra of Ti

3C

2T

x under different conditions. As seen in

Figure 7d, the pristine material exhibits four pairs of feature peaks corresponding to C–Ti–O, C–Ti–OF, C–Ti–F, and TiO

2, indicating that its surface has been partially oxidized during synthesis and exposure [

21]. As displayed in

Figure 7e, the peak intensity markedly decreases after electrochemical cyclings in AA, reaffirming the reductive role of AA in suppressing the formation of TiO

2. Meanwhile, the ratios of C–Ti–F and C–Ti–O increase, reflecting the redistribution of surface terminations. As shown in

Figure 7f, after 10-min nitrogen plasma treatment to achieve N10P-AA, the peak intensity of TiO

2 increases instead, suggesting that the plasma introduces more oxygen-containing groups. Compared with the electrode material in noP-AA, that in N10P-AA exhibits more prominent C–Ti–O and C–Ti–OF peaks, indicating that nitrogen plasma promotes oxygen affinity and also reinforces re-oxidation tendency on the surface. These results highlight the competing effect of AA and plasma: AA tends to suppress the formation of TiO

2, whereas nitrogen plasma inversely promotes the formation of TiO

2 and related oxygen-containing functional groups. The interaction between the two largely determines the chemical composition and stability of the Ti

3C

2T

x surface. To avoid ambiguity, it should be emphasized that XPS peak intensities mainly reflect the relative distribution of surface species within the probing depth, rather than a monotonic change in the absolute amount of a single phase. After electrochemical cycling in AA, the reducing nature of AA can attenuate unstable oxide-rich features, whereas N

2 plasma exposure can simultaneously promote the redistribution of surface terminations and expose additional Ti sites. Therefore, the increased Ti–O/TiO

2-related contribution observed in Ti 2p spectrum after plasma treatment is best interpreted as a reorganization toward oxygen-containing terminations (e.g., Ti–O/Ti–OH/Ti–OF), rather than the growth of a thick, insulating TiO

2-rich passivation layer. In this context, the apparently different Ti–O/TiO

2-related contributions in the O 1s and Ti 2p spectra can be reconciled within a unified framework of termination/oxidation-state reorganization, rather than contradictory oxidation behaviors.

Looking at

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the C 1s, F 1s, O 1s, and Ti 2p spectra obtained from different conditions show no significant chemical shifts in their respective peak positions, implying that the bonding environment and chemical states of Ti

3C

2T

x remain relatively stable. The effects of nitrogen plasma and using AA are primarily associated with regulating surface properties by changing the relative proportions of surface functional groups rather than altering the intrinsic bulk structure of Ti

3C

2T

x. The enhanced performance of N10P-AA over other devices is attributed to adjusting the number and distribution of surface functional groups rather than the difference in the intrinsic chemical state. The XPS results provide a surface chemistry foundation [

21], strongly supporting the aforementioned conclusions from electrochemical analysis. They clearly reveal that nitrogen plasma treatment (particularly 10 min) can effectively inhibit excessive oxidation of the Ti

3C

2T

x electrode during electrochemical cyclings while preserving the conductive framework. This protective effect is consistent with reduced R

CT and mitigated diffusion limitation for N10P-AA in the AA electrolyte, resulting in a larger b value and a smaller Warburg slope, and thus the overall best electrochemical performance among the AA-based devices. In contrast, noP-AA, which has not been treated with nitrogen plasma, suffers from severe oxidation and surface passivation, which impede both electron and ion transport, leading to inferior electrochemical performance.