Data-Driven State-of-Health Estimation by Reconstructing Virtual Full-Charge Segments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework for Virtual Capacity Reconstruction

- Quasi-static degradation: Within a sufficiently small mileage window , the lithiumion battery’s capacity degradation is considered negligible. For any two mileages and within this window,

- Consistency of polarization via clustering: Ideally, the capacity integration intervals should be defined based on the open-circuit voltage (OCV) to reflect thermodynamic equilibrium. However, real-world BMS data typically provides only terminal voltage (), which differs from OCV due to ohmic potential drop and polarization effects:Direct usage of for data splicing across heterogeneous operating conditions would introduce significant systematic errors, as the voltage drop would vary drastically. To validate the use of , we employ a strict clustering strategy based on the dominant operating factors, including current and temperature. By ensuring that all segments within a specific cluster share statistically similar current and temperature profiles, we impose a constraint where the polarization terms remain consistent across spliced segments:Under this condition, aligning segments based on becomes mathematically equivalent to aligning them based on with a constant offset . This effective alignment preserves the physical validity of the capacity integration within the standardized voltage intervals, despite the lack of OCV measurements. While internal resistance increases with long-term aging, the proposed method reconstructs capacity profiles locally within a narrow mileage window. Consequently, the impedance and polarization characteristics are considered distinct for each reconstruction instance but consistent within the splicing set, thereby isolating the aging effect from the reconstruction process.

3. Algorithmic Implementation for SOH Calculation

3.1. Data Acquisition and Feature Engineering

3.2. Operating Condition Classification via K-Means Clustering

3.3. Virtual Capacity Reconstruction via Splicing

| Algorithm 1 Robust Statistical Filtering for Virtual Capacity Calculation |

| Require: List of incremental capacities for voltage interval j |

| Ensure: Robust average |

|

4. Results and Discussion

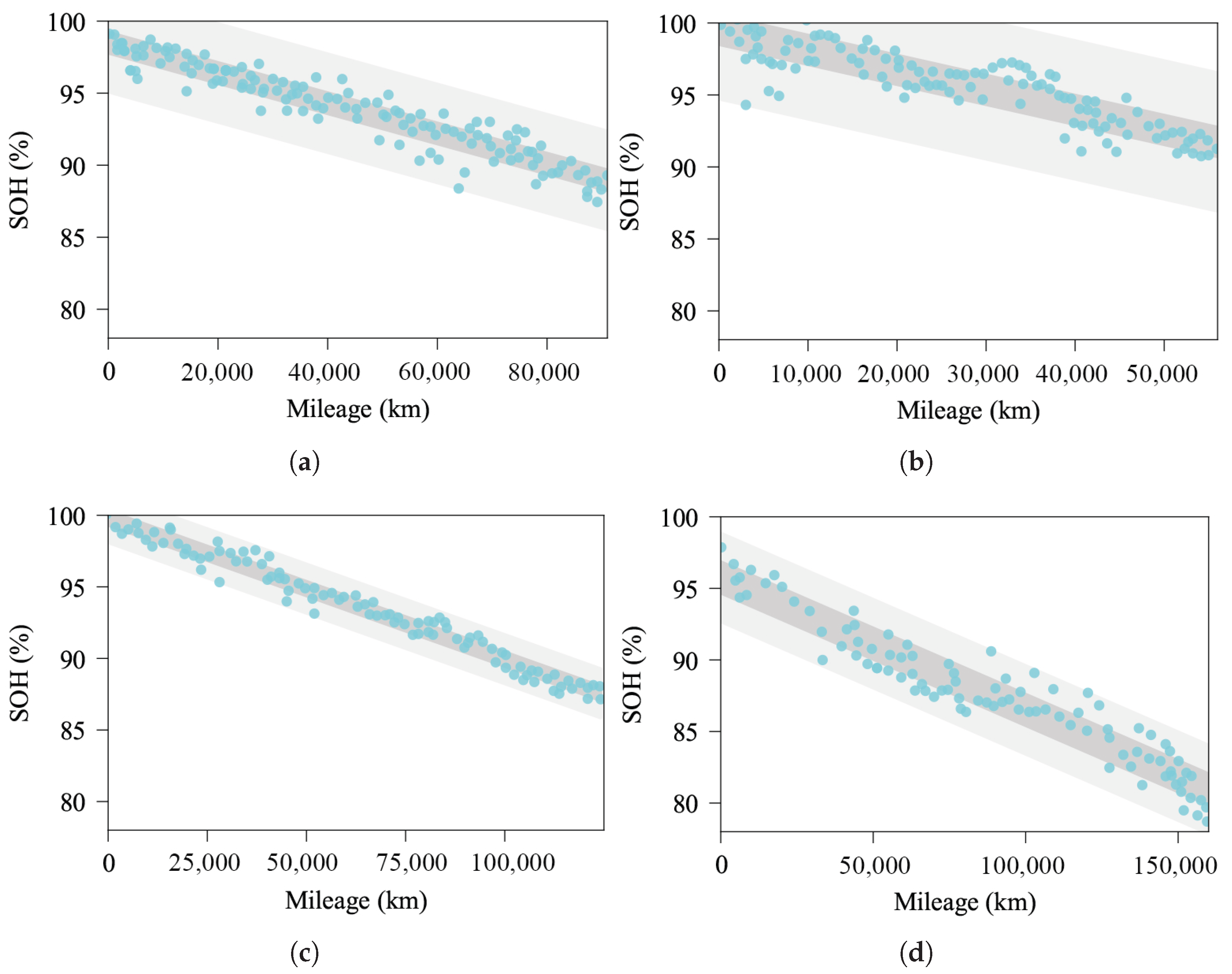

4.1. Experimental Dataset Overview

4.2. Operating Condition Clustering Results

4.3. Comparison with Industrial Baseline

4.4. SOH Estimation Performance on Randomly Selected Vehicles

4.5. Field Validation via Controlled Full-Charge Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMS | Battery management system |

| BOL | Beginning of life |

| ECM | Equivalent circuit model |

| EOL | End of life |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| NCM | Nickel–cobalt–manganese |

| NEV | New energy vehicle |

| OCV | Open-circuit voltage |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interphase |

| SOC | State of charge |

| SOH | State of health |

| SSE | Sum of squares |

References

- Khan, F.M.N.U.; Rasul, M.G.; Sayem, A.; Mandal, N.K. Design and optimization of lithium-ion battery as an efficient energy storage device for electric vehicles: A comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage 2023, 71, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiong, R.; Meng, X.; Deng, X.; Li, H.; Sun, F. Battery degradation evaluation based on impedance spectra using a limited number of voltage-capacity curves. eTransportation 2024, 22, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Wang, S.; Cao, W.; Fernandez, C.; Blaabjerg, F. A comprehensive review of multiple physical and data-driven model fusion methods for accurate lithium-ion battery inner state factor estimation. Batteries 2024, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Wei, G.; Tang, X.; Lai, X.; Dai, H. Lithium-ion battery sudden death: Safety degradation and failure mechanism. eTransportation 2024, 20, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Ma, Z.; Li, L. Multi-scale heterogeneity of electrode reaction for 18650-type lithium-ion batteries during initial charging process. Batteries 2024, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xing, B.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, Q. How does room temperature cycling ageing affect lithium-ion battery behaviors under extreme indentation? eTransportation 2024, 20, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, P.; Tong, B.; Cheng, Z.; Cao, M.; Mei, W.; Wang, Q.; Sun, J.; Qin, P. Revealing the mechanism of pack ceiling failure induced by thermal runaway in NCM batteries: A coupled multiphase fluid-structure interaction model for electric vehicles. eTransportation 2024, 20, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ping, P.; Kong, D.; Peng, R.; He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, X.; Wen, J. Advances and challenges in thermal runaway modeling of lithium-ion batteries. Innovation 2024, 5, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Ziebert, C.; Vahdatkhah, P.; Sadrnezhaad, S.K. Recent progress of deep learning methods for health monitoring of lithium-ion batteries. Batteries 2024, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Wei, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, G.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Jiang, B.; Lai, X.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, H. Mechanism of battery expansion failure due to excess solid electrolyte interphase growth in lithium-ion batteries. eTransportation 2025, 25, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkes, M.; Demirci, A.; Gokalp, E. An evaluation of optimal sized second-life electric vehicle batteries improving technical, economic, and environmental effects of hybrid power systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keske, C.; Srinivasan, A.; Sansavini, G.; Gabrielli, P. Optimal economic and environmental arbitrage of grid-scale batteries with a degradation-aware model. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, O.; Link, S.; Schneider, J.; Wolff, S.; Lienkamp, M. Techno-economic cell selection for battery-electric long-haul trucks. eTransportation 2023, 16, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarzadeh, H.; Di Maria, F. Progress, Challenges and Opportunities in Recycling Electric Vehicle Batteries: A Systematic Review Article. Batteries 2025, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, F.; Resalati, S.; Babaie, M.; Henshall, P.; Morrey, D.; Yao, L. A review of the technical challenges and solutions in maximising the potential use of second life batteries from electric vehicles. Batteries 2024, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Jiang, B.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Enhancing capacity estimation of retired electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries through transfer learning from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. eTransportation 2024, 22, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machala, M.L.; Chen, X.; Bunke, S.P.; Forbes, G.; Yegizbay, A.; de Chalendar, J.A.; Azevedo, I.L.; Benson, S.; Tarpeh, W.A. Life cycle comparison of industrial-scale lithium-ion battery recycling and mining supply chains. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Li, L.; Tian, J. Towards a smarter battery management system: A critical review on battery state of health monitoring methods. J. Power Sources 2018, 405, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Han, D.; Lee, P.Y.; Kim, J. Transfer learning applying electrochemical degradation indicator combined with long short-term memory network for flexible battery state-of-health estimation. eTransportation 2023, 18, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yao, F. Multi-Timescale Estimation of SOE and SOH for Lithium-Ion Batteries with a Fractional-Order Model and Multi-Innovation Filter Framework. Batteries 2025, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, S.S.; Hébert, M.; Boulon, L.; Lupien-Bédard, A.; Allard, F. Comparative Analysis of ML and DL Models for Data-Driven SOH Estimation of LIBs Under Diverse Temperature and Load Conditions. Batteries 2025, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lin, J.; Guo, D.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; He, G.; Ouyang, M. Towards real-world state of health estimation, Part 1: Cell-level method using lithium-ion battery laboratory data. eTransportation 2024, 21, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Guo, D.; Xiong, G.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, M. Towards real-world state of health estimation: Part 2, system level method using electric vehicle field data. eTransportation 2024, 22, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, P.; Colicelli, A.; Saponara, S. Review on modeling and soc/soh estimation of batteries for automotive applications. Batteries 2024, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucinskis, G.; Bozorgchenani, M.; Feinauer, M.; Kasper, M.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Waldmann, T. Arrhenius plots for Li-ion battery ageing as a function of temperature, C-rate, and ageing state–An experimental study. J. Power Sources 2022, 549, 232129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Sauer, D.U.; Li, W. Large-scale field data-based battery aging prediction driven by statistical features and machine learning. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Xie, Y.; Wu, R.; Song, Z. Multi-modal framework for battery state of health evaluation using open-source electric vehicle data. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, S.; Lopes, A.M.; Li, H.; Bao, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, P. A new SOH estimation method for Lithium-ion batteries based on model-data-fusion. Energy 2024, 286, 129597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; et al. SOH estimation method for lithium-ion batteries based on an improved equivalent circuit model via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Luo, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, S.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Battery SOH estimation method based on gradual decreasing current, double correlation analysis and GRU. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2023, 2, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhai, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Di, Y.; Chen, X. Physics-informed neural network for lithium-ion battery degradation stable modeling and prognosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.; Horstkötter, I.; Bäker, B. State-of-health estimation by virtual experiments using recurrent decoder–encoder based lithium-ion digital battery twins trained on unstructured battery data. J. Energy Storage 2023, 58, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhu, J.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Semi-supervised deep learning for lithium-ion battery state-of-health estimation using dynamic discharge profiles. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Xu, S.; Tang, A.; Zhou, F.; Hou, J.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, Z. A review of lithium-ion battery state of health estimation and prediction methods. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yan, Q.; Lin, F.; Yu, C.; Jiang, B.; Wei, X.; Yan, W.; et al. Advances in battery state estimation of battery management system in electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2024, 612, 234781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.K.; Panchal, S.; Khang, T.D.; Panchal, K.; Fraser, R.; Fowler, M. Concept review of a cloud-based smart battery management system for lithium-ion batteries: Feasibility, logistics, and functionality. Batteries 2022, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Han, X.; Zheng, Y.; Ouyang, M. Enhanced few-shot state-of-health estimation for lithium-ion batteries via Masked Autoencoder. Energy 2025, 335, 138263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Inf. Sci. 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainggolan, R.; Perangin-angin, R.; Simarmata, E.; Tarigan, A.F. Improved the performance of the K-means cluster using the sum of squared error (SSE) optimized by using the Elbow method. J. Physics Conf. Ser. 2019, 1361, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutomo, F.; Muaafii, D.A.; Al Rasyid, D.N.; Kurniawan, Y.I.; Afuan, L.; Cahyono, T.; Maryanto, E.; Iskandar, D. Optimization of the k-nearest neighbors algorithm using the elbow method on stroke prediction. J. Tek. Inform. (Jutif) 2023, 4, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Huang, T.; Lu, B.; Zhang, S.; Xiaog, R. Silhouette coefficient-based weighting k-means algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 3061–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vehicle No. | Mileage (km) | Measured SOH | Estimated SOH | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X761 | 39,565 | 0.962 | 0.949 | 1.3% |

| X655 | 89,841 | 0.910 | 0.928 | 1.8% |

| X117 | 248,778 | 0.815 | 0.796 | 1.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, D.; Zou, Z.; Lai, X.; Zheng, Y. Data-Driven State-of-Health Estimation by Reconstructing Virtual Full-Charge Segments. Batteries 2026, 12, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12010010

Guo D, Zou Z, Lai X, Zheng Y. Data-Driven State-of-Health Estimation by Reconstructing Virtual Full-Charge Segments. Batteries. 2026; 12(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Dongxu, Zhenghang Zou, Xin Lai, and Yuejiu Zheng. 2026. "Data-Driven State-of-Health Estimation by Reconstructing Virtual Full-Charge Segments" Batteries 12, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12010010

APA StyleGuo, D., Zou, Z., Lai, X., & Zheng, Y. (2026). Data-Driven State-of-Health Estimation by Reconstructing Virtual Full-Charge Segments. Batteries, 12(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries12010010