In Situ Estimation of Li-Ion Battery State of Health Using On-Board Electrical Measurements for Electromobility Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction and Motivation

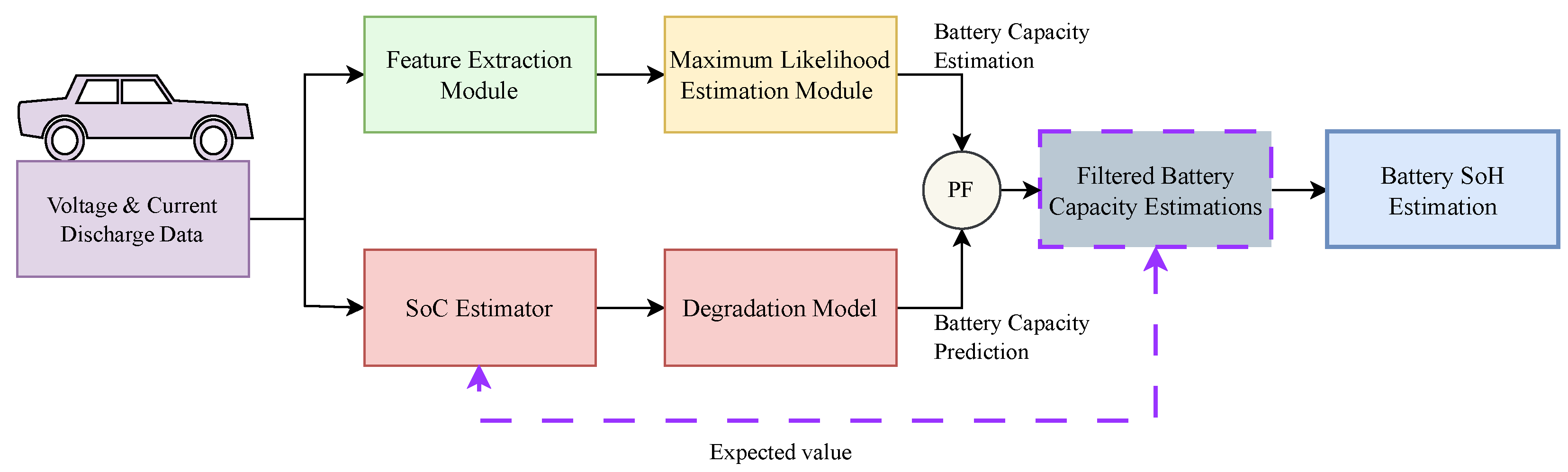

- A novel MLE-PF battery capacity estimation procedure is developed to obtain SoH estimates from an arbitrary current and voltage discharge profile.

- A PF algorithm is implemented to overcome model and estimation uncertainties and potential outliers during the degradation process.

- The addition of the PF enables the simultaneous online estimation of SoH and SoC without the need for time-intensive tests, which require battery disconnection.

- The proposed method is designed for use on a generic EV since current and voltage measurements are easy to obtain from a BMS or an OBD2 device.

- The proposed approach can be scaled to different types, modules, and lithium ion batteries since the parameters of the battery model can be adjusted with few operational data.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Definitions and Equivalent Circuit Battery Model

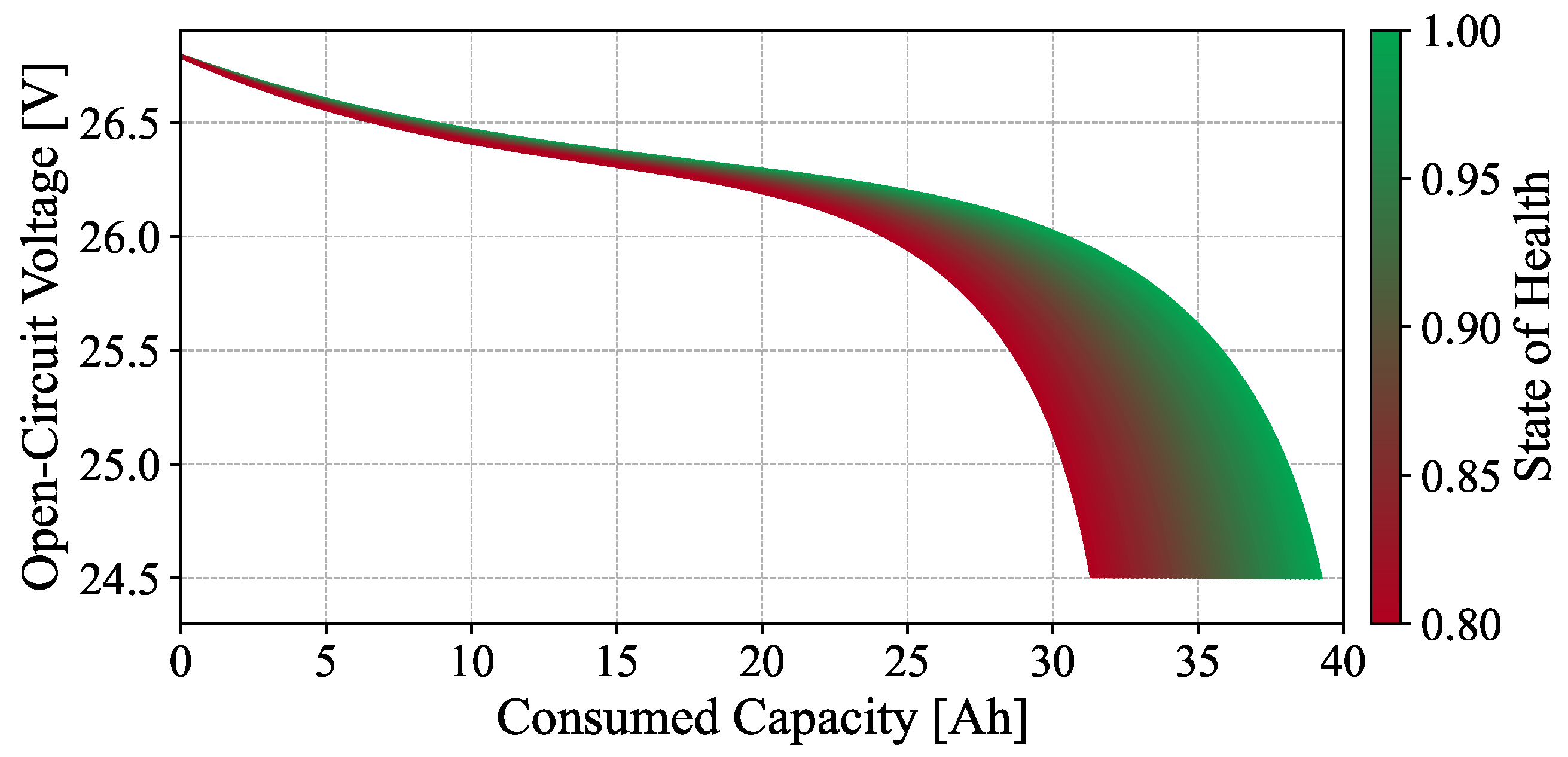

- The SoC represents the current capacity of the battery relative to its total current capacity, typically expressed as a percentage [30]. It indicates how much charge remains in the battery and its evolution in time can be mathematically formulated as:where and are the SoC and the current at the previous time step, respectively, is the sampling time interval, is the battery capacity at cycle k (i.e., the maximum charge the cell can store at that cycle), and represents the process noise accounting for uncertainties such as current sensor inaccuracies, unmodeled dynamics, and environmental variations. By incorporating noise, the model becomes more robust and can better capture the real-world behavior of batteries, enhancing the credibility and reliability of the SoC estimate. The SoC trend can vary over time depending on the discharge rate, which in practice is associated with different usage profiles [31].To connect the SoC concept with practical battery applications, it is essential to consider an equivalent circuit model that simulates the battery behavior under various operational scenarios. In this work, we use a Thévenin-equivalent model, which includes a controlled voltage source that represents the open-circuit voltage , integrated with a resistance to simulate real-world conditions [32].The open-circuit voltage is a nonlinear function of the SoC and is can be represented through a three-stage structure that reflects the dominant electrochemical mechanisms across different SoC ranges. Studies such as [33] have shown that, at high SoC values, a combination of partial redox reactions and increased charge accumulation near electrode saturation produces a pronounced curvature in the OCV–SoC relationship, effectively described by a shifted exponential function. In the mid-SoC region, the main intercalation and phase-transition reactions of the active materials proceed smoothly, yielding a nearly affine voltage response that can be captured by a linear term. Conversely, at low SoC values, redox activity is minimal and the voltage exhibits a sharp decline driven by surface charge-accumulation effects, which is well modeled by logarithmic or exponential behavior.Beyond these chemical considerations, it is also essential to account for the aging-induced voltage drift observed in the OCV curve as the battery degrades. As reported in [34], periodic OCV measurements exhibit a progressive leftward shift over the cell’s lifetime, reflecting both capacity loss and changes in the electrode equilibrium potentials. This systematic displacement indicates that a fixed OCV curve cannot accurately represent the evolving equilibrium voltage associated with different SoH levels, thereby motivating the use of a parametric formulation whose coefficients can be adapted to aging.Building on this structure and considering the proposed Thévenin-equivalent circuit, the five-parameter OCV model introduced in [35] is adopted in this work and expressed in Equation (2) where each term in corresponds to a distinct operational zone of the OCV curve. The offline procedure proposed in [36] allows the identification of model parameters using a single controlled-discharge experiment, whereas [37] extends this approach to data collected from an EV operating under real driving conditions. These formulations enable the OCV curve to adapt to different SoH levels, as illustrated in Figure 1.

- On the other hand, the SoH refers to the battery’s ability to deliver its total current capacity compared to its original (or nominal) capacity when new [30]. In the battery literature, SoH can be characterized through several degradation indicators (e.g., capacity loss, increase in internal impedance, power fade, or self-discharge rate) which contribute to describing the battery health state [3]. Nevertheless, many studies point out that the most widely adopted formulation in both research and practice remains the capacity-based definition [38,39]. That is why, in the context of this study, we adopt the most common and widely accepted formulation, and we define SoH solely on a capacity basis, as reported in Equation (3).where is the State of Health at cycle k, is the battery capacity at cycle k, and is the nominal (initial) capacity when the battery is new. The capacity decreases with each cycle due to degradation, affecting the duration and energy delivered in subsequent cycles. A common way to represent degradation over the battery operational cycles is by describing the maximum energy storage capability that the battery can deliver over time. One way to model this degradation is through the equation:where is the capacity at the current cycle, and are the capacity and the efficiency factor in the previous cycle, respectively. and represents the process noise capturing uncertainties such as degradation rate variability, measurement errors, and unmodeled aging effects. Similarly to , the term is introduced to model the inherent uncertainties and stochastic nature of battery operation to make SoH estimation more robust.The efficiency factor serves as an aggregate representation of the Loss of Lithium Inventory (LLI) induced by each duty cycle experienced by the battery [40]. As highlighted in [41], LLI is one of the dominant degradation modes in LIBs, arising primarily from SEI growth, lithium plating, and crack-assisted side reactions, all of which irreversibly trap cyclable lithium and reduce the amount of charge that can be reversibly stored. These mechanisms occur even under moderate operating conditions and accumulate over time, leading to measurable reductions in accessible capacity. By expressing the degradation of a given cycle as a multiplicative efficiency applied to the previous available capacity, the model effectively captures the fraction of lithium lost to these irreversible pathways, allowing the model to track the progressive depletion of cyclable lithium as the battery ages.Since the SoC is intrinsically linked to the SoH via the current maximum capacity, the SoH also influences the behavior of the curve [42] as an external parameter. Figure 1 illustrates this dependency by showing how the OCV curve shifts with different SoH values.In fact, a reduced battery capacity implies that the SoC will drop more quickly for the same amount of extracted charge, causing to decrease significantly faster. Starting from Equation (2), this relationship is expressed mathematically in Equation (5), where it is clear that is a function of the SoC. More specifically, represents the battery capacity at a given cycle k and the extracted charge. Note that a lower increases the impact of on .

2.2. Estimation

2.2.1. Maximum Likelihood Estimation

2.2.2. Bayesian Filtering

Particle Filter

3. MLE-PF Framework: A Simple and Reliable Estimation Method for Battery Capacity Using Operational Data

3.1. Theoretical Rationale for Battery Capacity Estimation

3.2. Framework Overview

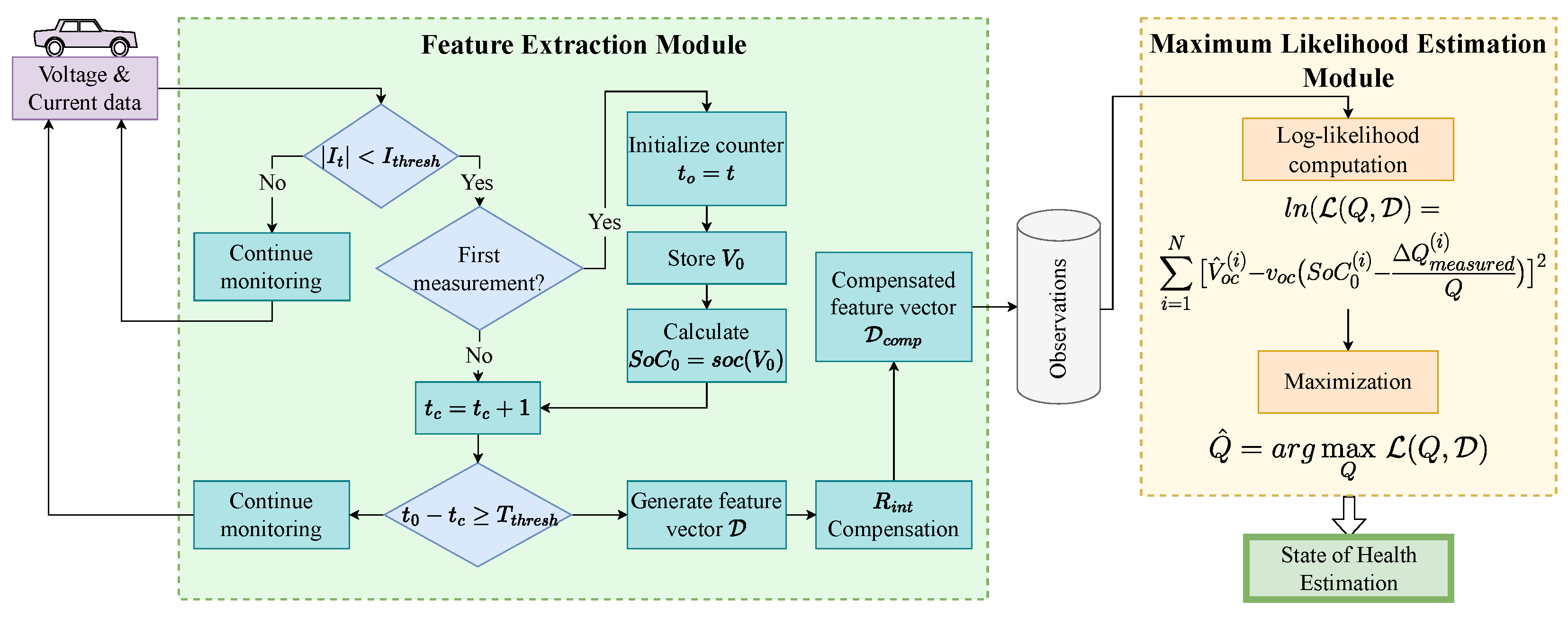

3.2.1. Feature Extraction Module

- First, the FEM identifies moments during the discharge process when the current values are low. This condition minimizes voltage drops caused by the internal impedance, ensuring a more accurate representation of the open-circuit voltage. This requirement is imposed by the threshold condition in (17):where is the current measurement and is the current low pass threshold.

- In addition, since the battery’s internal impedance might present transients, a second condition must be considered in series to the first one. The FEM checks if the low current measurements are consistent for a given amount of time to minimize the effect of voltage transients due to impedance. The expression in Equation (18) represents the logical operator that indicates that a voltage measurement is close to its corresponding and can be formulated as:where is a counter that indicates how much time with low current has passed, and represents the second control parameters that regulate how permissive the selector is. The combined condition can be formulated as:By applying this logical condition to the voltage and current signals, the FEM generates a set of observations .

- Despite the low stable currents, they might still alter the approximation of when multiplied by the internal resistance. For this reason, an internal impedance compensation module is added to the flow as explained in Section 3.2.2. The application of this additional module adjusts the observation to .

3.2.2. Resistance Effect Compensation

3.2.3. Maximum Likelihood Estimation Module

- During the feature extraction, capacity degradation is neglected.

- The extracted features are conditionally identically independent and identically distributed.

- The extracted open voltage features are affected by Gaussian additive noise with some variance .

4. Case Study

Dataset Description

- SoC: calculated for each experiment by integrating the current over time. This value is normalized with the SoC variation limits (20% and 100%).

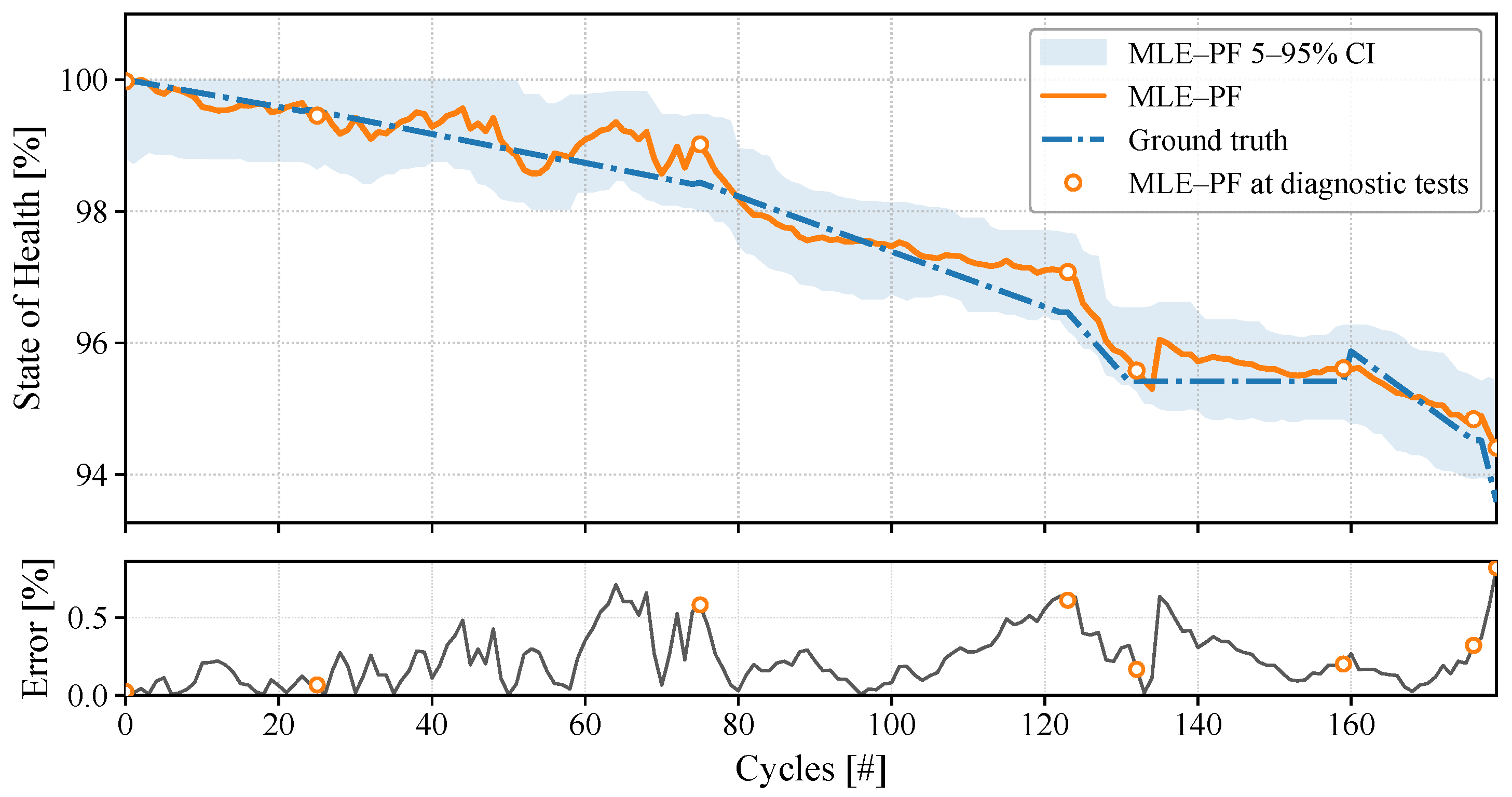

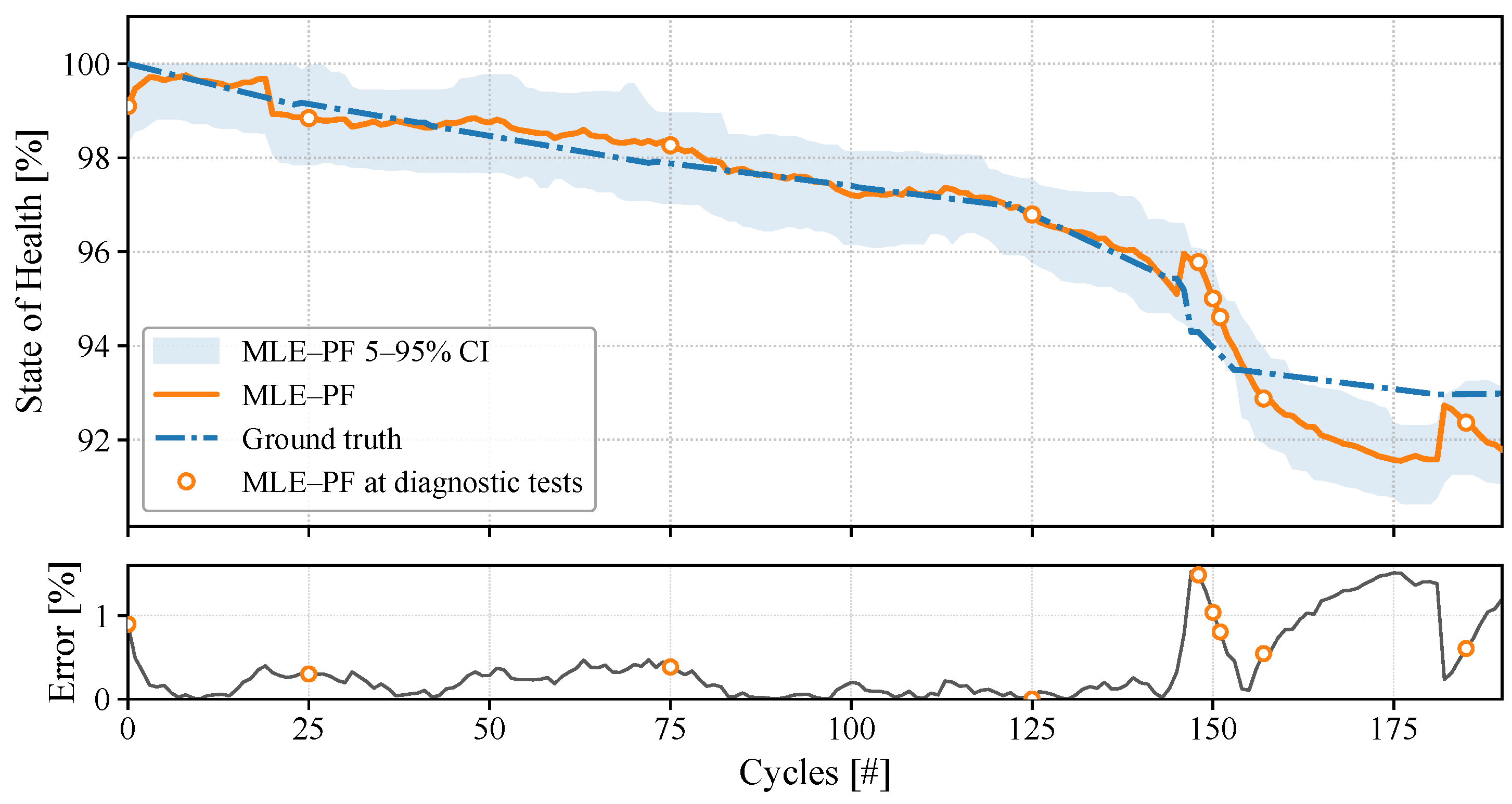

- SoH: It is important to note that this dataset does not directly provide the SoH values; instead, SoH has been derived from capacity measurements. Additionally, the current capacity data is not provided for each cycle but is available only at specific assessment intervals. To establish a continuous SoH trend with values at each cycle, linear interpolation has been employed to estimate capacity (and consequently SoH) between the reported data points. This interpolated data will serve as the reference for the cell SoH. This interpolated data will serve as the reference for the cell SoH. However, in Section 5 the MLE–PF estimates are also compared against the non-interpolated ground-truth capacity values at diagnostic cycles, and these errors are reported as the primary performance metrics.

5. Results

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Low-Current Detection Parameters

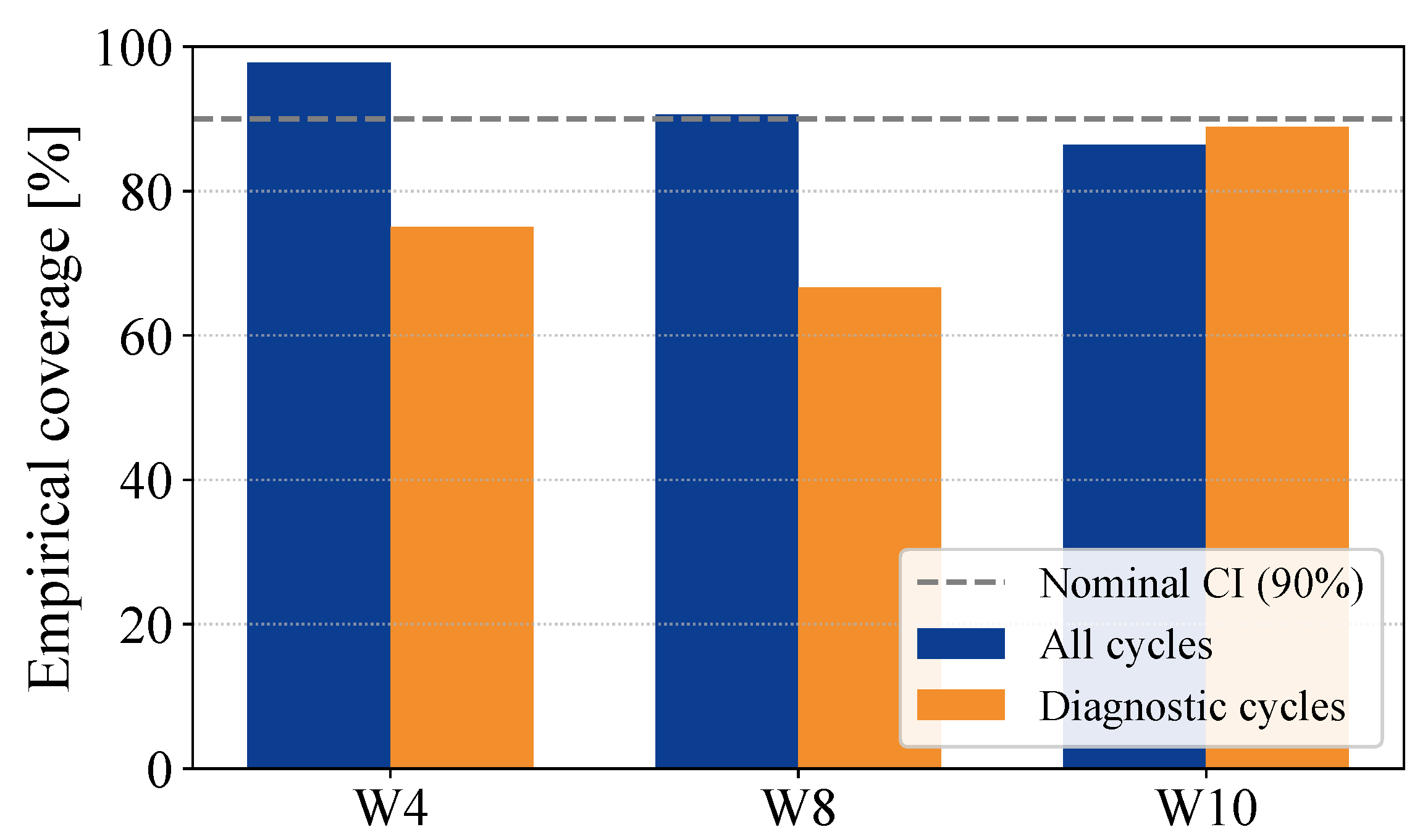

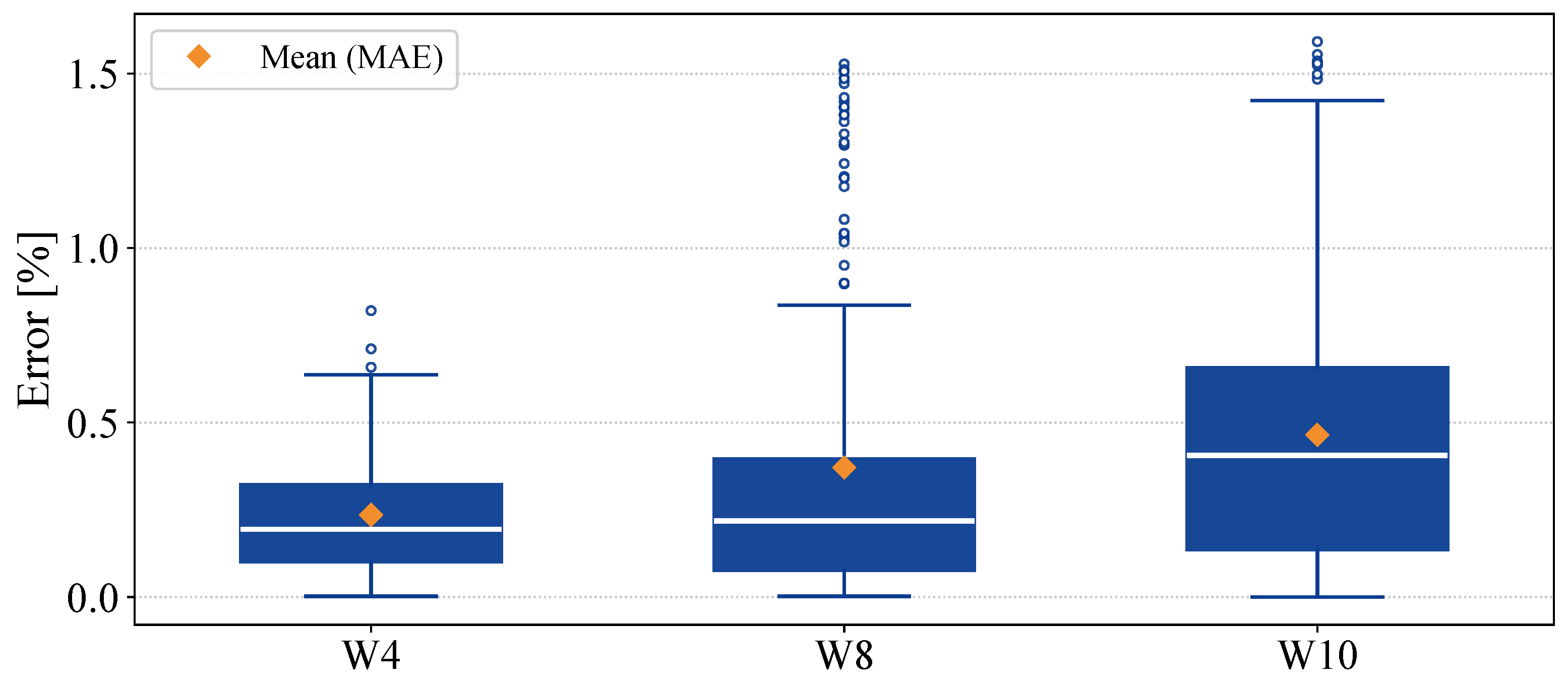

5.2. SoH Estimation Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| LIB | Lithium-Ion Batteries |

| DoD | Depth of Discharge |

| SoH | State of Health |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| PF | Particle Filter |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| RUL | Remaining Useful Life |

| SoH | State of Health |

| PHM | Prognostic and Health Management |

| CAN | Controller Area Network |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| MLE-PF | Maximum Likelihood Estimation-Particle Filter |

| BF | Bayesian Filter |

| OCV | Open-Circuit Voltage |

| SIS | Sequential Importance Sampling |

| Probability Density Function | |

| FEM | Feature Extraction Module |

| CCCV | Constant-Current Constant-Voltage |

| UDDS | Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule |

| HPPC | Hybrid Pulse Power Characterization |

| t | time step index |

| k | Work cycle index |

| I | Current |

| Sampling time | |

| w | SoC process noise |

| Open-circuit voltage | |

| Pseudo-open-circuit voltage | |

| C | Battery capacity parameter (used in the MLE module) |

| Battery capacity at work cycle k | |

| Initial (nominal) battery capacity | |

| Efficiency factor | |

| v | Capacity process noise |

| L | Likelihood function |

| MLE parameters | |

| Probability density function of the data given the parameters | |

| T | Low current counter |

| Set of observations | |

| Battery internal resistance | |

| Extracted charge | |

| Low-current threshold used in the FEM | |

| Minimum low-current duration used in the FEM | |

| Total number of detected pseudo-OCV points | |

| Equivalent Series Resistance (internal resistance of the cell) |

References

- Velev, B.; Djudzhev, B.; Dimitrov, V.; Hinov, N. Comparative Analysis of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Urban Electric/Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Batteries 2024, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebiam, R.; Kannan, A.; Prado, F.; Manthiram, A. Comparison of the chemical stability of the high energy density cathodes of lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2001, 3, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, J.S.; O’Kane, S.; Prosser, R.; Kirkaldy, N.D.; Patel, A.N.; Hales, A.; Ghosh, A.; Ai, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Lithium ion battery degradation: What you need to know. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 8200–8221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ping, P.; Zhao, X.; Chu, G.; Sun, J.; Chen, C. Thermal runaway caused fire and explosion of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2012, 208, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, L.H.; Ye, Y.; Tay, A.A. Integration issues of lithium-ion battery into electric vehicles battery pack. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyoye, B.D.; Bhattacharya, I.; Anthony Dhason, M.V.; Banik, T. State of Charge and State of Health Estimation in Electric Vehicles: Challenges, Approaches and Future Directions. Batteries 2025, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, M.; Chen, Y.; Tao, Y. A novel health indicator for on-line lithium-ion batteries remaining useful life prediction. J. Power Sources 2016, 321, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiong, R.; Tian, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, F. Deep learning to estimate lithium-ion battery state of health without additional degradation experiments. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipu, M.H.; Hannan, M.; Hussain, A.; Hoque, M.; Ker, P.J.; Saad, M.; Ayob, A. A review of state of health and remaining useful life estimation methods for lithium-ion battery in electric vehicles: Challenges and recommendations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Akram, A.S.; Choi, W. Analysis of Aging and Degradation in Lithium Batteries Using Distribution of Relaxation Time. Batteries 2025, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Dai, H.; Liu, L. State-of-Health Estimation of LiFePO4 Batteries via High-Frequency EIS and Feature-Optimized Random Forests. Batteries 2025, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Shang, W.; Dai, H. A comparative study of different features extracted from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy in state of health estimation for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2022, 322, 119502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, N.; Boulon, L.; Jemeï, S. A review of battery state of health estimation methods: Hybrid electric vehicle challenges. World Electr. Veh. J. 2020, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuroldayeva, G.; Serik, Y.; Adair, D.; Uzakbaiuly, B.; Bakenov, Z. State of Health Estimation Methods for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 4297545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yuan, H.; Zou, C.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L. Co-Estimation of State of Charge and State of Health for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Fractional-Order Calculus. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 10319–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Ouyang, M.; Lu, L.; Li, J.; Feng, X. The Co-estimation of State of Charge, State of Health, and State of Function for Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. A comparative study of battery state-of-health estimation based on empirical mode decomposition and neural network. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Garg, A.; Panigrahi, B.; Kim, J. An Evolving Quantum Fuzzy Neural Network for online State-of-Health estimation of Li-ion cell. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 143, 110263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Weng, C.; He, X.; Han, X.; Lu, L.; Ren, D.; Ouyang, M. Online State-of-Health Estimation for Li-Ion Battery Using Partial Charging Segment Based on Support Vector Machine. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 8583–8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxandi-Santolaya, M.; Montes, T.; Casals, L.C.; Corchero, C.; Eichman, J. Data-Driven State of Health and Functionality Estimation for Electric Vehicle Batteries Based on Partial Charge Health Indicators. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 5321–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, P.; Duan, B.; Zhang, C. A hybrid data-driven method optimized by physical rules for online state collaborative estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Energy 2024, 301, 131710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Mao, L.; Qu, K.; Zhao, J.; Li, F.; Jiang, L. State of Health Estimation and Remaining Useful Life Estimation for Li-ion Batteries Based on a Hybrid Kernel Function Relevance Vector Machine. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 221135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhu, J.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Semi-supervised deep learning for lithium-ion battery state-of-health estimation using dynamic discharge profiles. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Su, Y.; Ye, J.; Xu, P.; Xu, E.; Ouyang, T. Enhanced state-of-charge and state-of-health estimation of lithium-ion battery incorporating machine learning and swarm intelligence algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bai, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Ding, M. SOH estimation for lithium-ion batteries: An improved GPR optimization method based on the developed feature extraction. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, S.; Crawford, C. Probabilistic lithium-ion battery state-of-health prediction using convolutional neural networks and Gaussian process regression. J. Energy Storage 2024, 76, 109799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Shen, F.; Sun, L.; Zhang, M.; Wei, J. A Bayesian Inferred Health Prognosis and State of Charge Estimation for Power Batteries. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1000312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Du, C.; Ren, Z. A Novel Method for Estimating the State of Health of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Physics-Informed Neural Network. Batteries 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Hu, J.; Peng, W. Bayesian calibrated physics-informed neural networks for second-life battery SOH estimation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264, 111432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Xia, X.; Zeng, X. State of charge and state of health estimation strategies for lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2023, 18, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulpuri, S.K.; Sah, B.; Kumar, P. Unraveling capacity fading in lithium-ion batteries using advanced cyclic tests: A real-world approach. iScience 2023, 26, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Quintero, V.; Pérez, A.; Jaramillo, F.; Burgos-Mellado, C.; Rozas, H.; Orchard, M.E.; Sáez, D.; Cárdenas, R. Particle-Filtering-Based Prognostics for the State of Maximum Power Available in Lithium-Ion Batteries at Electromobility Applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 7187–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Loh, P.C. A Generalized SOC-OCV Model for Lithium-Ion Batteries and the SOC Estimation for LNMCO Battery. Energies 2016, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzato, G.; Allam, A.; Onori, S. Lithium-ion battery aging dataset based on electric vehicle real-driving profiles. Data Brief 2022, 41, 107995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, J.E.G.; Baeza, C.; Schiele, B.B.; Rivera, V.; Masserano, B.; Orchard, M.E.; Burgos-Mellado, C.; Perez, A. A novel data-driven framework for driving range prognostics in electric vehicles. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 142, 109925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pola, D.A.; Navarrete, H.F.; Orchard, M.E.; Rabié, R.S.; Cerda, M.A.; Olivares, B.E.; Silva, J.F.; Espinoza, P.A.; Pérez, A. Particle-Filtering-Based Discharge Time Prognosis for Lithium-Ion Batteries With a Statistical Characterization of Use Profiles. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2015, 64, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Jaramillo, F.; Baeza, C.; Valderrama, M.; Quintero, V.; Orchard, M. A Particle-Swarm-Optimization-Based Approach for the State-of-Charge Estimation of an Electric Vehicle When Driven Under Real Conditions. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society, Virtual, 29 November–2 December 2021; Volume 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizi, G.; Canzanella, F.; Ciani, L.; Catelani, M. Towards a State of Health Definition of Lithium Batteries through Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Electronics 2024, 13, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Xu, S.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. A Review of Lithium-Ion Battery State of Health Estimation and Prediction Methods. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Goebel, K. Modeling Li-ion battery capacity depletion in a particle filtering framework. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the PHM Society, San Diego, CA, USA, 27 September–1 October 2009; Volume 1, pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- O’Kane, S.E.; Ai, W.; Madabattula, G.; Alonso-Alvarez, D.; Timms, R.; Sulzer, V.; Edge, J.S.; Wu, B.; Offer, G.J.; Marinescu, M. Lithium-ion battery degradation: How to model it. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 7909–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Han, X.; Dai, H.; Ouyang, M. Lithium-ion battery capacity estimation based on open circuit voltage identification using the iteratively reweighted least squares at different aging levels. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.L.; Ho, P.H.; Peng, L. Performance Analysis of Maximum Likelihood Estimation for Transmit Power Based on Signal Strength Model. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2018, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jin, M.; Dong, G.; Wei, S. Performance Analysis of the Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Signal Period Length and Its Application in Heart Rate Estimation with Reduced Respiratory Influence. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.J. Mathematical Statistics: An Introduction to Likelihood Based Inference; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Boughton, K.A. A Multidimensional Item Response Modeling Approach for Improving Subscale Proficiency Estimation and Classification. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2007, 31, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, A.; Pinasco, M.; Regazzoni, C.S. CHAPTER 9—Multi-Modal Data Fusion Techniques and Applications. In Multi-Camera Networks; Aghajan, H., Cavallaro, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, W.K. Monte Carlo Sampling Methods Using Markov Chains and Their Applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, M. Online fault detection of a mobile robot with a parallelized particle filter. Neurocomputing 2014, 126, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulampalam, M.; Maskell, S.; Gordon, N.; Clapp, T. A tutorial on particle filters for online nonlinear/non-Gaussian Bayesian tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paccha-Herrera, E.; Jaramillo-Montoya, F.; Calderón-Muñoz, W.R.; Tapia-Peralta, D.; Solórzano-Castillo, B.; Gómez-Peña, J.; Paccha-Herrera, J. A particle filter-based approach for real-time temperature estimation in a lithium-ion battery module during the cooling-down process. J. Energy Storage 2024, 94, 112413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, A.; Godsill, S.; Andrieu, C. On sequential Monte Carlo sampling methods for Bayesian filtering. Stat. Comput. 2000, 10, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, A.; Alonso, M.A. Chapter Seven—Maximum likelihood estimation in the context of an optical measurement. In A Tribute to Emil Wolf; Visser, T.D., Ed.; Progress in Optics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 65, pp. 231–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Q. A Maximum Likelihood Estimation Method for Underwater Radiated Noise Power. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, I.J. Tutorial on maximum likelihood estimation. J. Math. Psychol. 2003, 47, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, A.; Freitas, N.; Gordon, N. Sequential Monte Carlo Methods in Practice, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappé, O.; Godsill, S.; Moulines, E. An overview of existing methods and recent advances in sequential Monte Carlo. Proc. IEEE 2007, 95, 899–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Mellado, C.; Orchard, M.E.; Kazerani, M.; Cárdenas, R.; Sáez, D. Particle-filtering-based estimation of maximum available power state in Lithium-Ion batteries. Appl. Energy 2016, 161, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Tian, J.; Li, D.; Tian, Y. An Online State of Charge Estimation Algorithm for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using an Improved Adaptive Cubature Kalman Filter. Energies 2018, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Cho, B. State-of-charge and capacity estimation of lithium-ion battery using a new open-circuit voltage versus state-of-charge relationship. J. Power Sources 2008, 185, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, B.E.; Cerda, M.A.; Orchard, M.E.; Silva, J.F. Particle-Filtering-Based Prognosis Framework for Energy Storage Devices with a Statistical Characterization of State-of-Health Regeneration Phenomena. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2013, 62, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampier, C.; Pérez, A.; Jaramillo, F.; Quintero, V.; Orchard, M.E.; Silva, J.F. Lithium-Ion Battery End-of-Discharge Time Estimation and Prognosis based on Bayesian Algorithms and Outer Feedback Correction Loops: A Comparative Analysis. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society 2015, Austin, TX, USA, 18–24 October 2015; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito Schiele, B. Health Inference and Diagnostic Architecture Based on Bayesian Filtering and Maximum Likelihood Estimation for Electromobility and Structural Engineering. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2024. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/203347 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Baek, S.; Choi, W. Performance Comparison of Machine Learning-Based Static Capacity Estimation Technique with Various C-rate Partial Discharges. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific (ITEC Asia-Pacific), Xi’an, China, 10–13 October 2024; pp. 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, J.; Wang, B.; Luk, P.C.K. An improved Thevenin model of lithium-ion battery with high accuracy for electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell | T [°C] | Charge C-Rate | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W4 | 23 | C/4 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 123 | 132 | 159 | 176 | 179 | N/A |

| W8 | 23 | C/2 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 125 | 148 | 150 | 151 | 157 | 185 |

| W9 | 23 | 1C | 0 | 25 | 75 | 122 | 144 | 145 | 146 | 150 | 179 |

| W10 | 23 | 3C | 0 | 25 | 75 | 122 | 146 | 148 | 151 | 159 | 188 |

| [A] | [s] | Interpolated MAE [%] | MAE at Diagnostic Tests [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.025 | 47 | 0.235 | 0.349 | 1026 |

| 0.050 | 47 | 0.480 | 0.420 | 1512 |

| 0.025 | 23 | 0.573 | 0.487 | 4270 |

| 0.050 | 23 | 0.507 | 0.503 | 7835 |

| 0.075 | 23 | 0.937 | 1.040 | 7927 |

| 0.100 | 23 | 0.850 | 1.020 | 9387 |

| Cell | Interpolated MAE [%] | MAE at Diagnostic Tests [%] | Diagnostic Points Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| W4 | 0.235 | 0.349 | 8 |

| W8 | 0.369 | 0.686 | 9 |

| W10 | 0.465 | 0.517 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustos, J.E.G.; Schiele, B.B.; Baldo, L.; Masserano, B.; Jaramillo-Montoya, F.; Troncoso-Kurtovic, D.; Orchard, M.E.; Perez, A.; Silva, J.F. In Situ Estimation of Li-Ion Battery State of Health Using On-Board Electrical Measurements for Electromobility Applications. Batteries 2025, 11, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120451

Bustos JEG, Schiele BB, Baldo L, Masserano B, Jaramillo-Montoya F, Troncoso-Kurtovic D, Orchard ME, Perez A, Silva JF. In Situ Estimation of Li-Ion Battery State of Health Using On-Board Electrical Measurements for Electromobility Applications. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):451. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120451

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustos, Jorge E. García, Benjamín Brito Schiele, Leonardo Baldo, Bruno Masserano, Francisco Jaramillo-Montoya, Diego Troncoso-Kurtovic, Marcos E. Orchard, Aramis Perez, and Jorge F. Silva. 2025. "In Situ Estimation of Li-Ion Battery State of Health Using On-Board Electrical Measurements for Electromobility Applications" Batteries 11, no. 12: 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120451

APA StyleBustos, J. E. G., Schiele, B. B., Baldo, L., Masserano, B., Jaramillo-Montoya, F., Troncoso-Kurtovic, D., Orchard, M. E., Perez, A., & Silva, J. F. (2025). In Situ Estimation of Li-Ion Battery State of Health Using On-Board Electrical Measurements for Electromobility Applications. Batteries, 11(12), 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120451