Abstract

Heteroleptic iron(III) complexes of formula [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙nMeCN have been synthesized; [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙MeCN, 1 and [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)], 2. The latter can be obtained by slow evaporation of solutions of compound 1 under ambient conditions, a rare occurrence in nonporous compounds. 1 interestingly shows a unique magnetic profile over the de-solvation temperature range, 300-350 K, in the first cycle, and becomes stable after the third cycle with a hysteresis width of about 20 K. Different de-solvation techniques used on compound 1 give rise to various stable de-solvated phases. Consequently, distinct magnetic profiles, with a larger hysteresis width of about 30 K, are present. Cl substitution on the qsal− ligand introduces C–H∙∙∙Cl and P4AE interactions into the structure which are absent in the related unsubstituted compound, [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.5MeCN, 3. Comparisons in structural packing, as well as spin crossover properties between unsubstituted and Cl-substituted ligand compounds, are discussed.

1. Introduction

Spin crossover (SCO) compounds continue to attract great interest from both a fundamental and a more applied, molecular (memory) device perspective. [1,2] Fundamental aspects include such features as multistep spin transitions, cooperativity, and, of relevance to the present study, the relationship between magnetic properties and supramolecular and intermolecular interactions occurring between the metal complexes, in the crystal, as well as between cationic metal complex and anion and/or solvated molecules. Mononuclear SCO complexes were the first to be reported, [1] those containing chelating ligands being largely of the homoleptic type, apart from iron(II) 2,2’-bipyridine/NCS combinations and Fe(III)(tetradentate)(L)2]+ species. While polynuclear SCO compounds have generated great interest in recent years, mononuclear species still yield surprises, particularly in their magnetic features and spin transition profiles.

In this context, we have recently reported one of the first examples of a heteroleptic iron(III) spin crossover compound, specifically containing two different meridional tridentate chelators viz. [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙solvent, in which qsal− = quinolylsalicylaldimine, thsa2− = thiosemicarbazone-salicylaldiminate, solvent = n-BuOH, THF, MeCN [3]. The ligand donor set is N3O2S. Of particular interest was the effect upon SCO that the degree of solvation produced, the parent materials having stoichiometries 0.4 solvent (n-BuOH), and 0.5 solvent (THF, MeCN), while the latter two retained their crystallinity to yield a phase containing 0.1 solvent upon warming. Full solvent removal produced a mixture of two polymorphs of [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]. These polymorphs resorbed liquid MeCN, but not MeCN vapour, to reform crystals of [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.1MeCN. Structurally, these compounds contain two structurally distinct Fe(III) centres that give rise, in the case of [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.5MeCN to the spin transition HS-HS to HS-LS below 250 K. The structural integrity around the Fe centres is maintained in the [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.5MeCN, [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.1MeCN, and [Fe(qsal)(thsa)] crystals with a site for the solvent molecule, occupied to varying degrees, clearly evident. Supramolecular interactions in the packing diagrams of the type π-π, C-H-π, C-H-N/S lead to 1D and 2D motifs and the interactions are influenced by the solvent molecule occupation in the MeCN series.

With all the above mentioned subtleties in mind, we have begun to explore the effects on SCO of ligand substitution in the aromatic salicylaldimine rings of both the qsal− and thsa2−moieties. Not only will this affect the ligand field strength at Fe(III) but also will allow new intermolecular interactions, such as halogen bonding, to be explored. Here we focus on the qsal− substitution in the form of the 5-chloro derivative, qsal-Cl−, within the complexes [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙MeCN, 1 and [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)], 2. Where relevant, comparisons to the unsubstituted analogue [Fe(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.5MeCN, 3 will be made.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structural Study

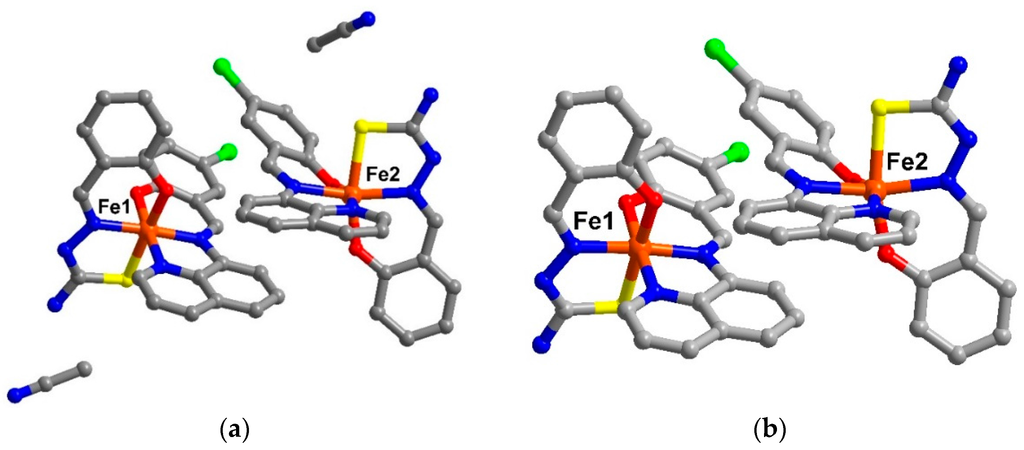

The crystal structure of [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙MeCN, 1 has been examined at 100 K. The data revealed that the structure crystallizes in the triclinic, P system and there are two neutral molecules of [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)] in the asymmetric units together with two molecules of MeCN solvent. There is, therefore, one molecule of MeCN per formula unit of the Fe(III) compound 1. After compound 1 had been left to dry under ambient conditions for 1 week, the crystal maintained its crystallinity and was still suitable to provide the crystal structure at 100 K of the de-solvated phase, [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)], 2. Compound 2 crystallized in the same crystal system as 1 with a slightly smaller cell volume by about 13 Å3. The crystallographic data are shown in Table S1. The asymmetric unit of compound 2 also shows two neutral molecules of [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)] but without any trace of solvent molecules (Figure 1). It results in a calculated accessible void of about 12% of the unit cell volume (307 Å3) which is larger than that in the unsubstituted related compound [Fe(qsal)(thsa)], 3 (10 %, 244 Å3) [3].

Figure 1.

The asymetric unit of (a) solvate form, compound 1 and (b) de-solvate form, compound 2 (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity).

Figure 1.

The asymetric unit of (a) solvate form, compound 1 and (b) de-solvate form, compound 2 (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity).

The Fe(III) centres in compounds 1 and 2 are coordinated to a qsal− and a thsa2− ligand in meridional fashion. For Fe1, the Fe-L bond lengths (Fe–O ≈ 1.87-1.91, Fe–N ≈ 1.93-1.97, Fe–S ≈ 2.22 Å) and low octahedral distortion parameters (Ʃ ≈ 40–44 and Θ ≈ 77–79) [4,5] are indicative of the LS state. Whilst at the Fe2 centre, the average bond lengths are longer than those of the Fe1 by about 0.04, 0.18, and 0.21 Å for Fe–O, Fe–N, and Fe–S, respectively. These are consistent with the larger distortion parameters (Table S2) and are typical for HS Fe(III). They, thus, define the mixture of LS and HS states of Fe(III) for compound 1 and 2 at low temperature.

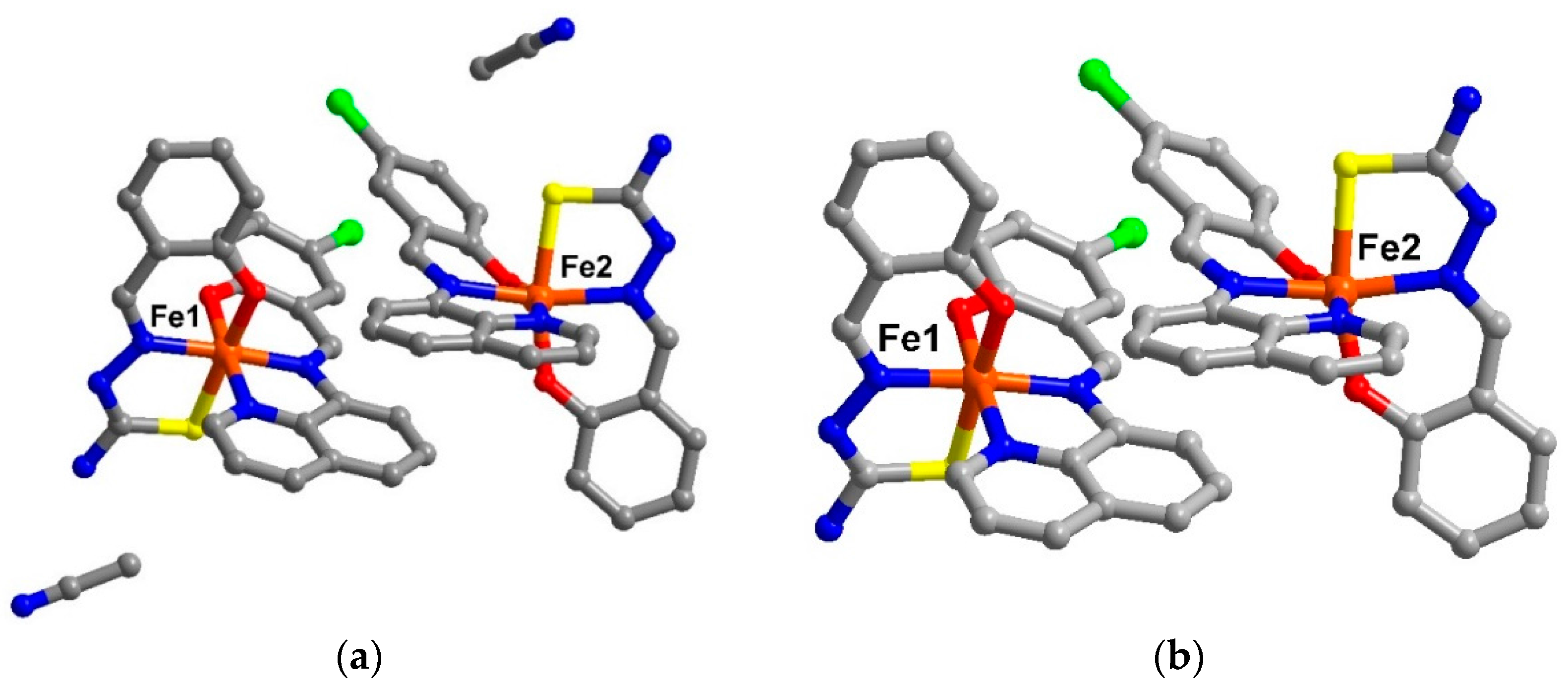

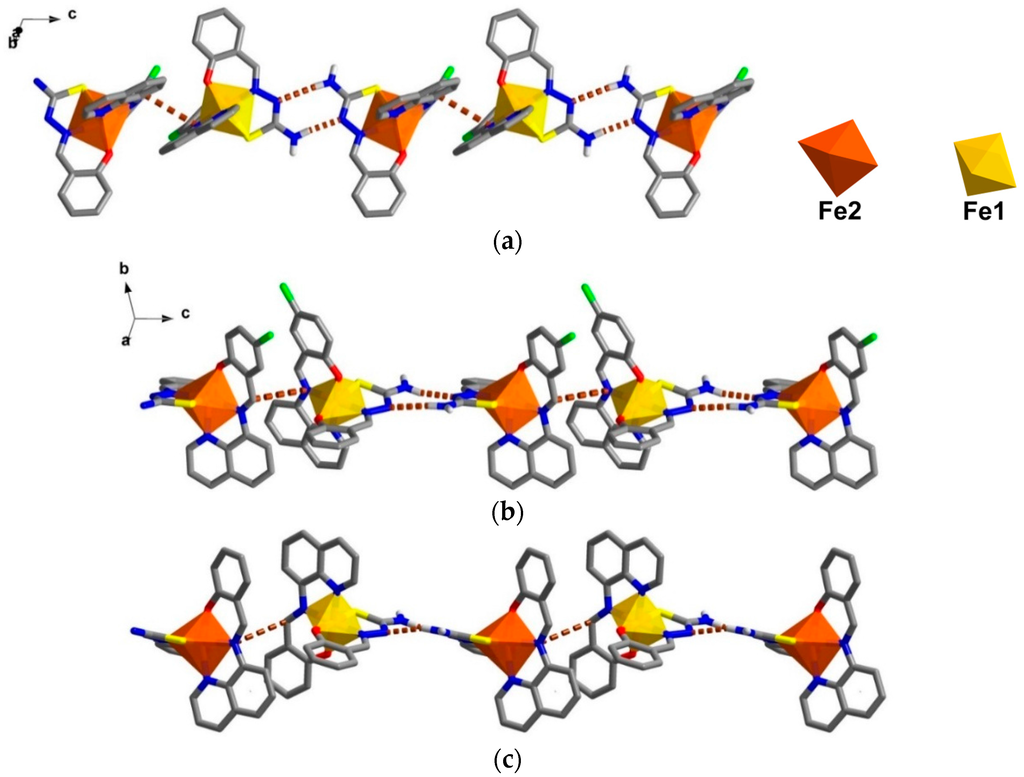

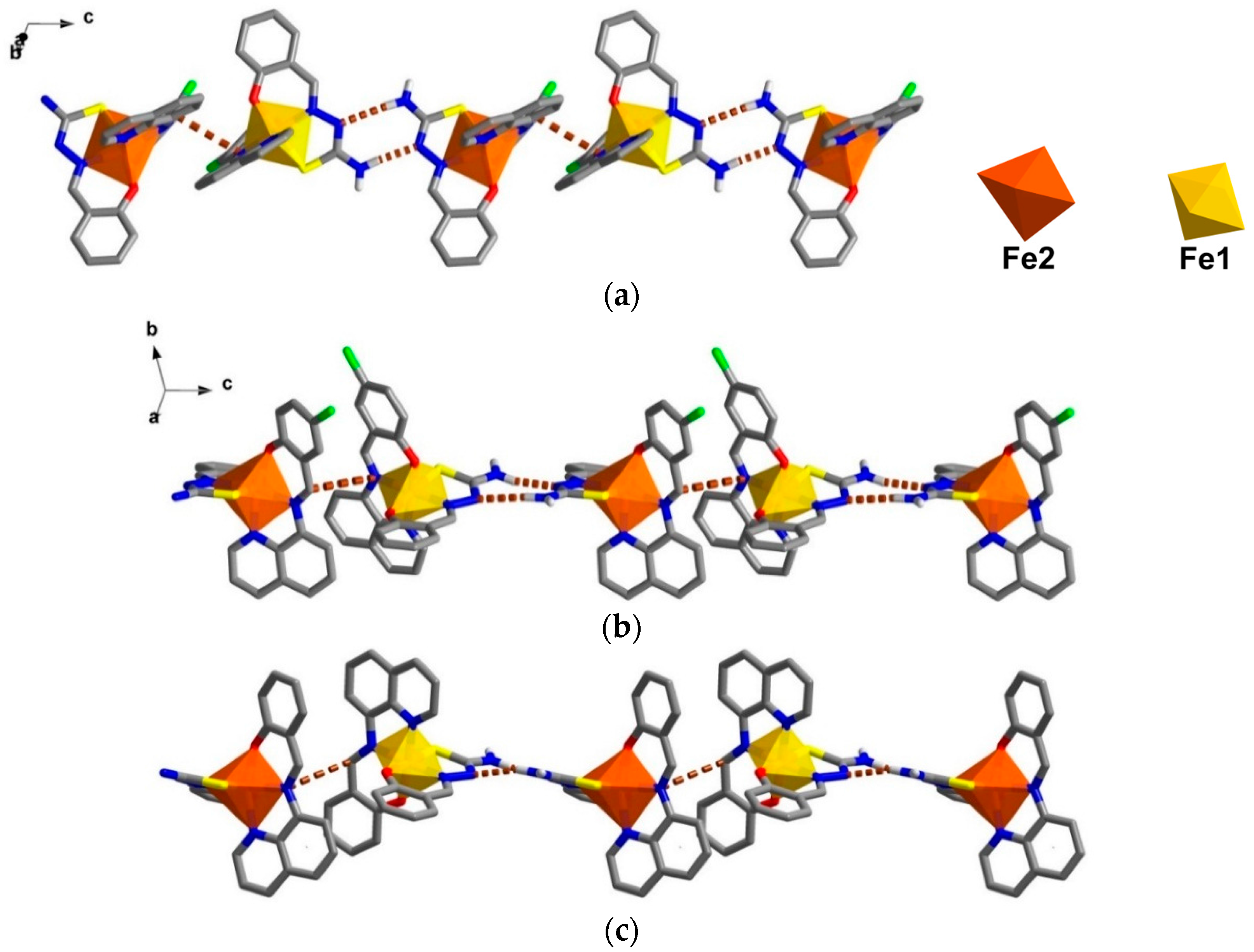

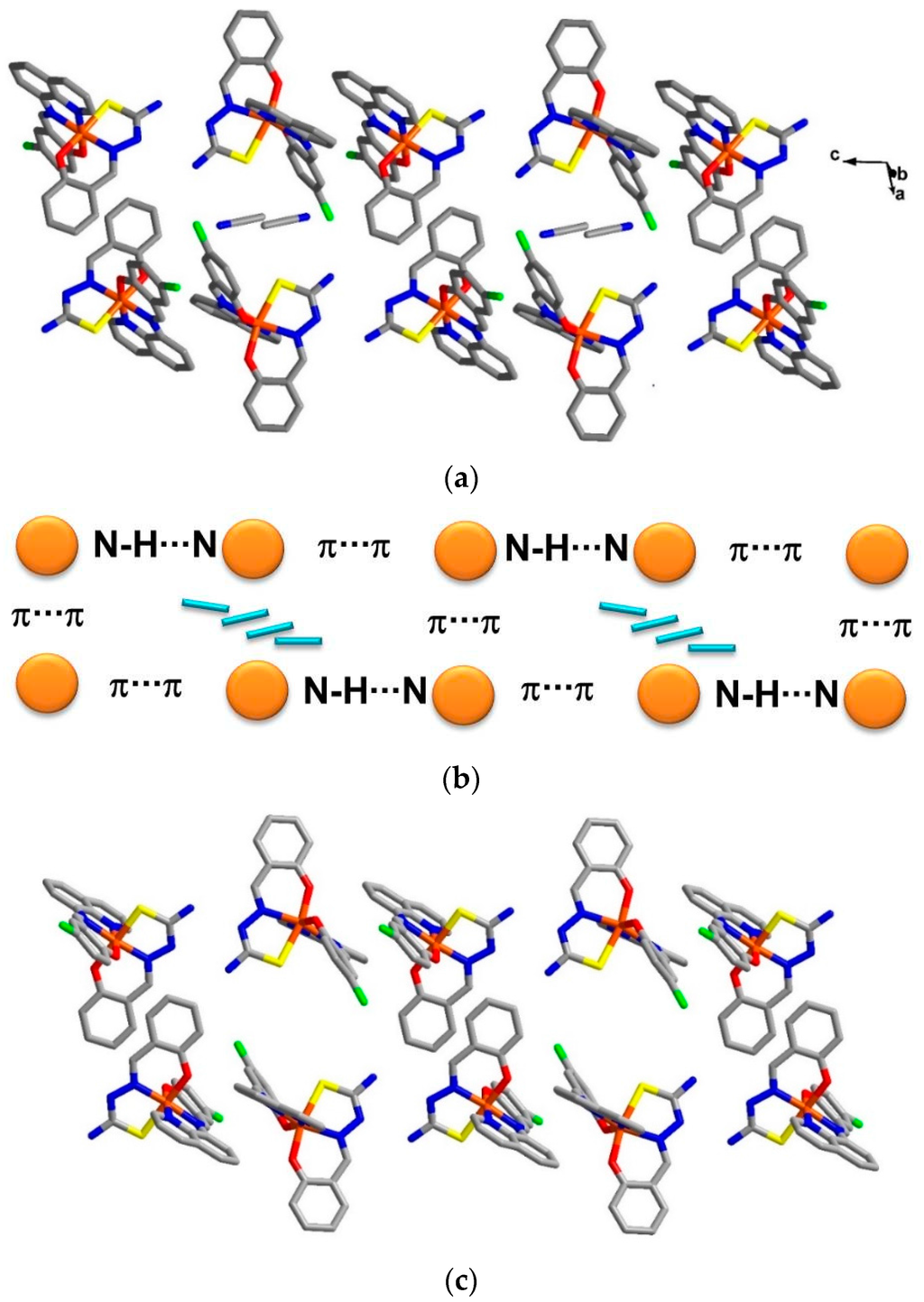

The crystal packing for the solvate, 1, and the de-solvated compound, 2, are intriguingly identical. A chain along the c axis connects through π-π and N-H∙∙∙N interactions resulting in a Fe1-Fe2-Fe1 chain connectivity which is a similar situation to that found in 3. However, the π-π interactions are different, since in 1 they connect the sal-sal and quin-quin rings but they connect sal-quin rings in the case of 3, as shown in Figure 2. Consequently, the different packing from 3 is observed in a higher dimension. These chains form double chains along the c axis through π-π interactions involving the thsa2− ligand. This gives rise to a free cavity for the MeCN solvent to occupy in compound 1 or be absent from in compound 2. Moreover, there are C–H∙∙∙Cl and two sets of P4AE (Parallel Four Fold Aryl Embrace) [6] interactions along the a axis that forms a double helix-like chain (Figure S1) and there are Fe1-Fe1 chains that connect through π-π interactions of qsal-qsal and thsa-thsa ligands along diagonal ab axes that mainly hold the sheet in a pseudo-3D structure (Figure S2). All detail of intermolecular interactions and simplified packing schemes are presented in Table S3 and Figure S3. As mentioned ealier, the structural packing as well as the intermolecular interactions, in 1 and 2, are really alike (Figure 3) with small differences compared to those are found in 3. This confirms that the strong rigidity of the frameworks of [Fe(qsal-X)(thsa)] (where X = H, 3 and Cl , 1) is able to maintain the framework even during de-solvation processes. Such behaviour is rarely observed in isolated molecular systems.

Figure 2.

(a) π-π and N-H∙∙∙N interactions connecting Fe moieties along the c axis producing Fe1-Fe2-Fe1-Fe2 chains in compound 1; (b) π-π interactions connecting sal-sal and quin-quin moieties in 1; and (c) π-π interactions in 3 connecting sal-quin moieties.

Figure 2.

(a) π-π and N-H∙∙∙N interactions connecting Fe moieties along the c axis producing Fe1-Fe2-Fe1-Fe2 chains in compound 1; (b) π-π interactions connecting sal-sal and quin-quin moieties in 1; and (c) π-π interactions in 3 connecting sal-quin moieties.

Figure 3.

Double chains along the c axis in (a) compound 1; (b) a simplified scheme of related interactions and (c) compound 2.

Figure 3.

Double chains along the c axis in (a) compound 1; (b) a simplified scheme of related interactions and (c) compound 2.

2.2. Magnetism

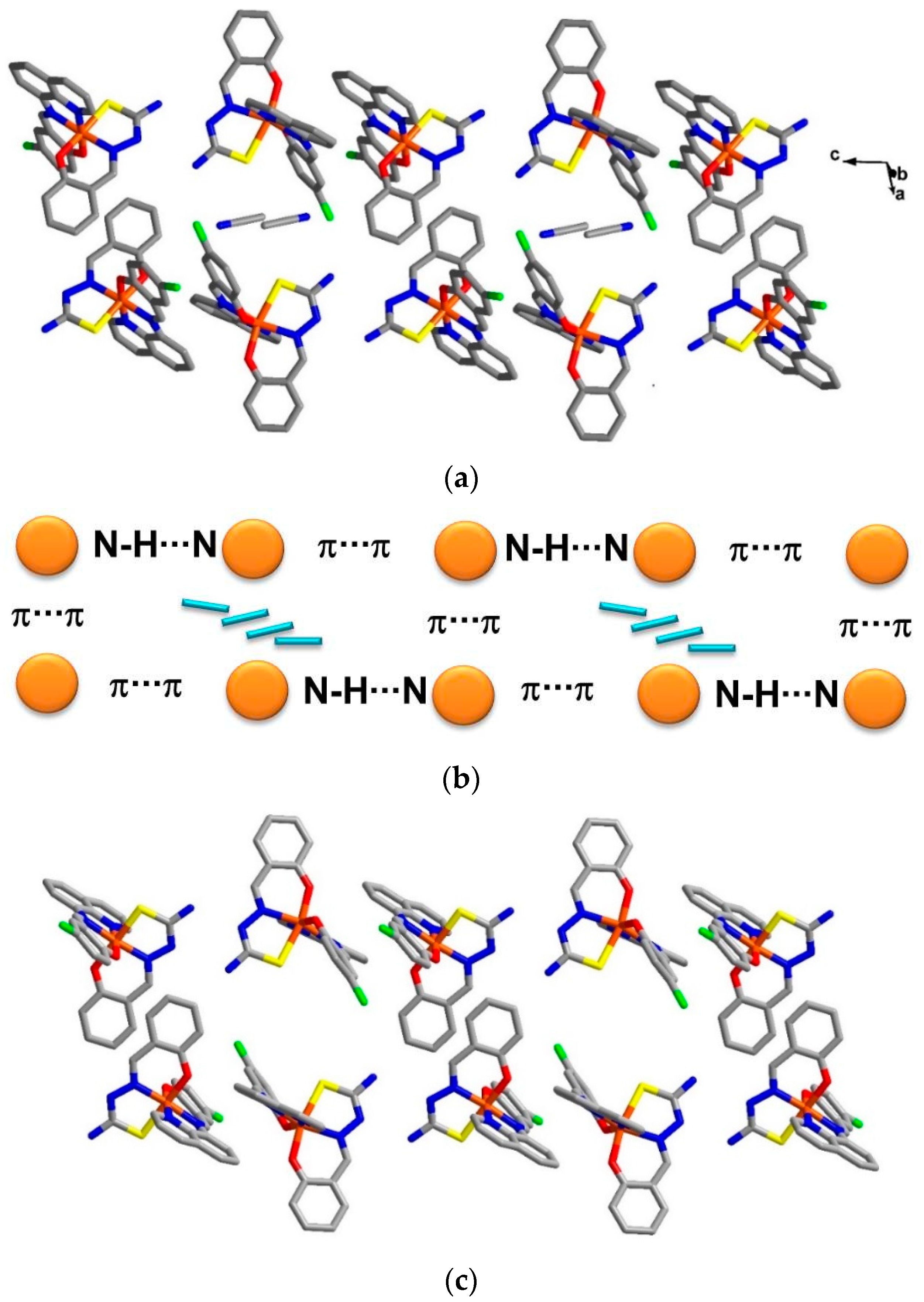

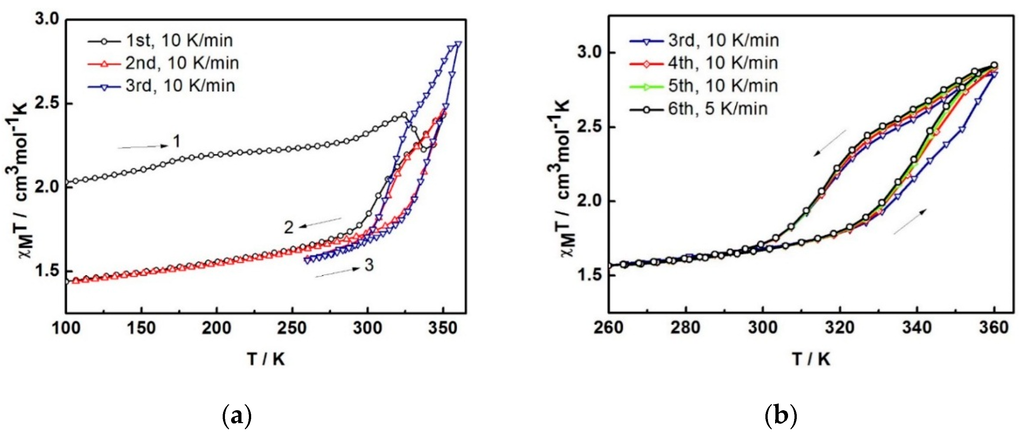

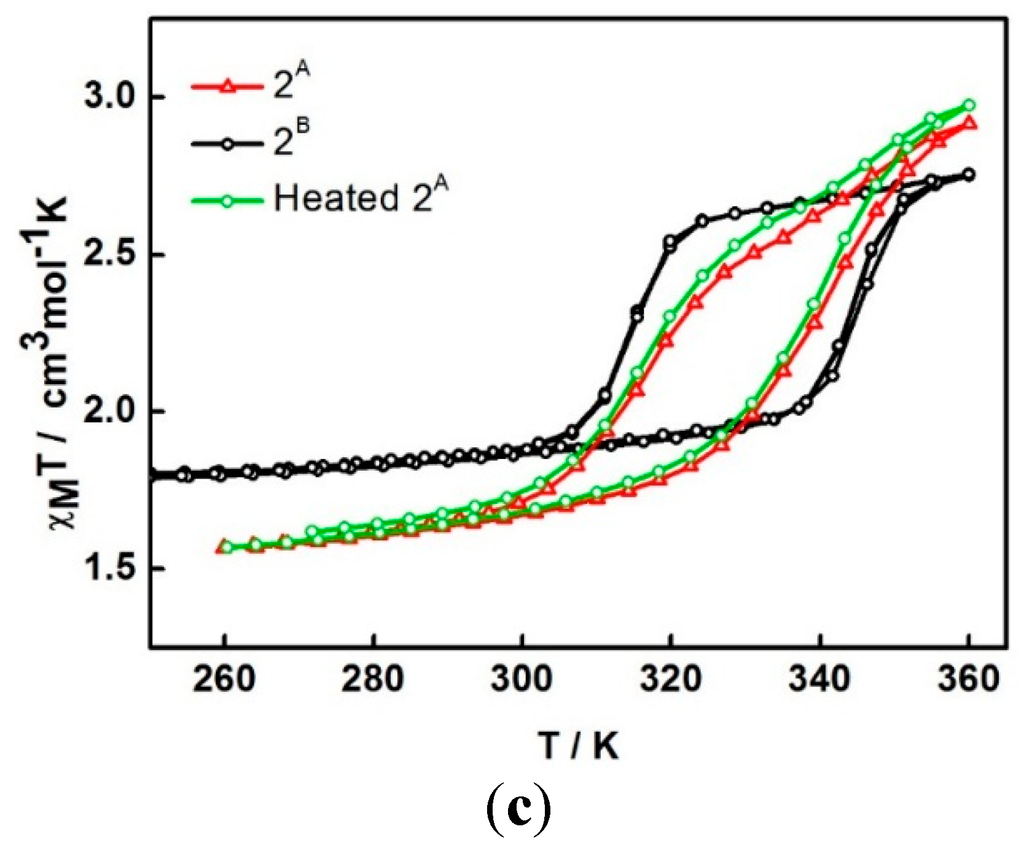

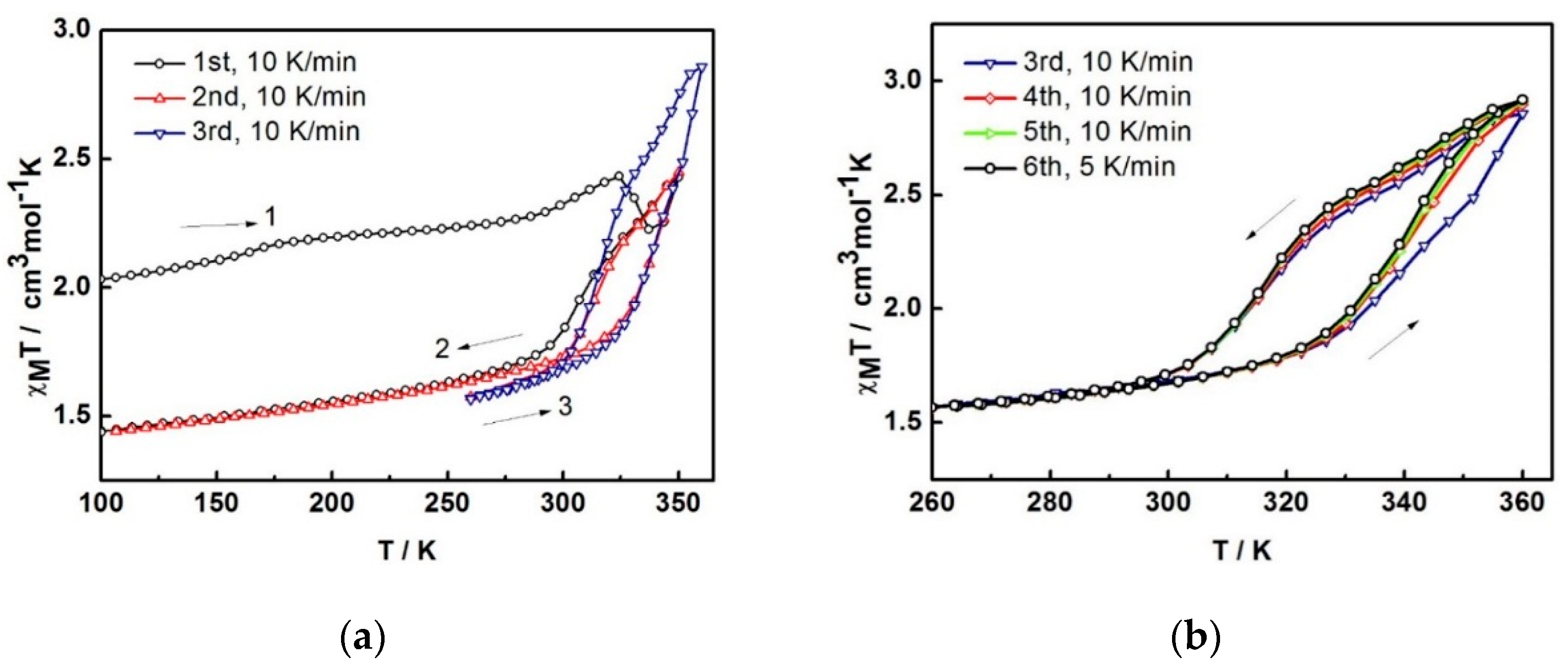

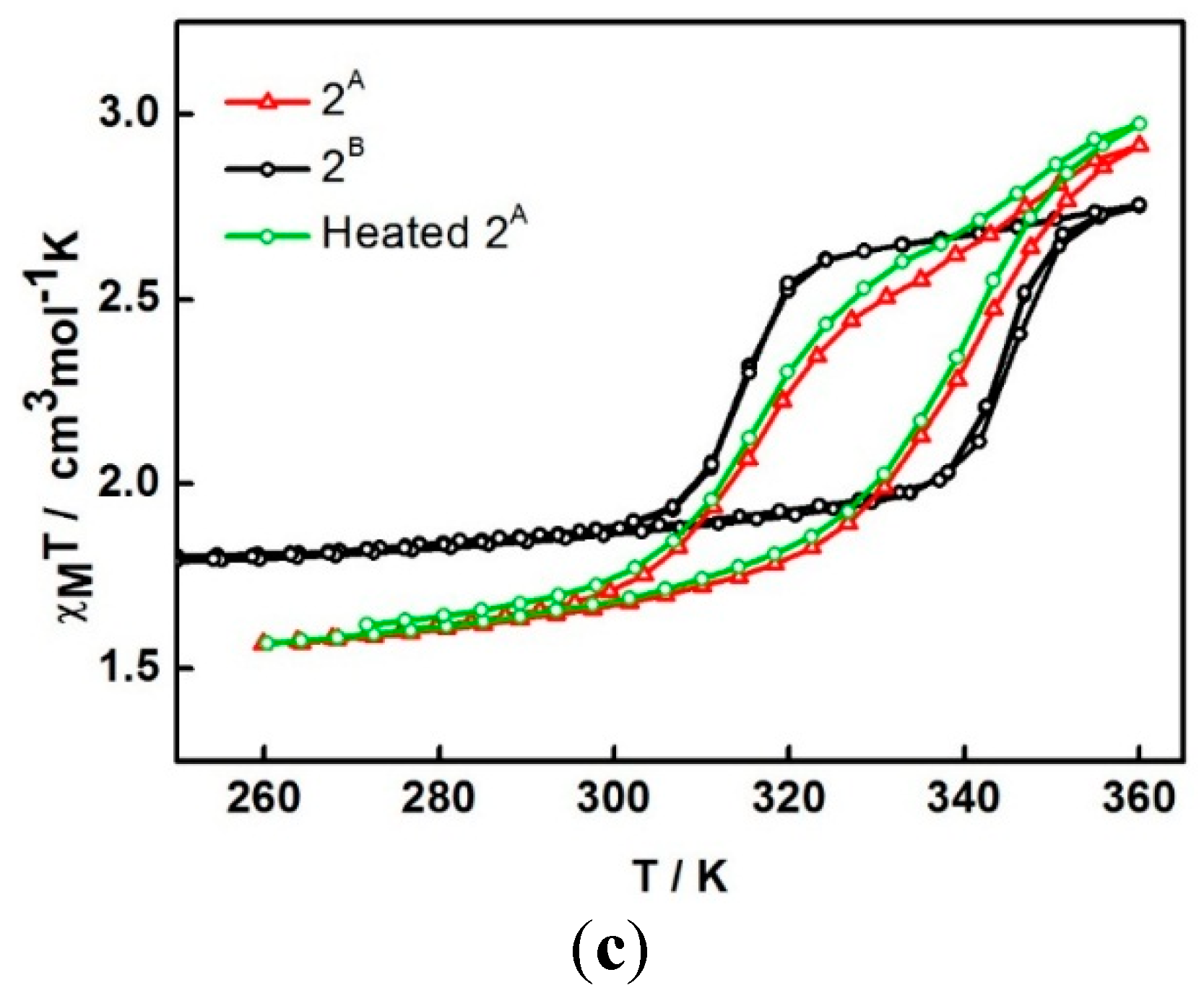

The variable-temperature magnetic susceptibility data for the compounds were measured between 100 and 360 K and are illustrated in Figure 4. The data are unusual and repeatable using freshly-prepared samples. Compound 1 was freshly removed from the mother liquor and held in an unsealed gel capsule without Vaseline coating. The sample was quench-cooled to 100 K and the measurements started at low temperature. In Figure 4a, at 100 K, the χMT of 2.03 cm3 K mol−1 is consistent with the single crystal structure that indicates the mixture of LS and HS states present at 100 K. Warming up to 324 K, the magnetic susceptibility slightly increases up to 2.43 cm3 K mol−1. After that, it unpredictably fluctuates, decreasing to 2.22 cm3 K mol−1 at 337 K and increasing back again to reach the maximum of 2.43 cm3 K mol−1 at 350 K. Upon cooling, the magnetic susceptibility drops to 1.74 cm3 K mol−1 at 288 K and gradually decreases to reach 1.44 cm3 K mol−1 at 100 K. For the second cycle, the profile repeats the cooling mode in the first cycle and faintly rise up to 1.86 cm3 K mol−1 at 324 K before increasing again to 2.45 cm3 K mol−1 at 350 K. Notably, the heating plot in the second cycle overlaps with the heating plot in the first cycle after solvent loss above 337 K. Cooling down to 260 K, the plot are also similar to the cooling mode in the first run and results in the small hysteresis of 20 K (T1/2↑ = 333 K and T1/2↓ = 313 K). The spin transition region has been explored in detail and cycles-measured between 260–360 K. For the following cycles, the hysteresis is also observed with 20 K width (T1/2↑ = 343 K and T1/2↓ = 323 K) but it approaches the maximum χMT of 2.9 cm3 K mol−1 at 360 K. The magnetic profile is repeatable after the third cycle, Figure 4b with a slightly smaller hysteresis width of 17 K (T1/2↑ = 339 K and T1/2↓ = 322 K) that is independent of the scan rate. Thus, it can be seen from the magnetic data of the sixth cycle, measured with a scan rate of 5 K/min, it is identical to the others measured at 10 K/min scan rate.

As the magnetic plot alters after the first heating run, we believe that this is a result of MeCN loss occurring in situ during the magnetic measurement. The fluctuation noted between 324 and 350 K is similar to the magnetic plots reported in the first cycle for [Fe(bpp)2][Cr(bpy)(ox)2]2∙2H2O and [Fe(bpp)2][Cr(phen)(ox)2]2∙0.5H2O∙0.5MeOH (bpp = 2,6-bis(pyrazol-3-yl)pyridine) [7]. We suggest that the Fe(III) centres in 1 are changing their spin state to the more stabilized LS phase after 1 has lost MeCN of solvation. However, it is immediately forced back to the HS state again, as the temperature increases. It, therefore, shows a rapid decrease followed by a rapid increase within about 25 K. The stable LS phase of the de-solvated compound is consistent with the lower magnetic susceptibility by about 0.6 cm3 K mol−1 in the following cycle at 100 K (2.03 cm3 K mol−1 and 1.44 cm3 K mol−1 for the solvated and desolvated phase, respectively). This contrasts with the behavior of compound 3 in which de-solvation gives rise to more stabilized HS phase and spin crossover concomitantly takes place from LS to HS [3].

For the second cycle, the structure packing is assumed to re-orientate until reaching a stable phase, 2A, and provide the steady plot in the third cycle. The magnetic properties of a dry form has been investigated in detail. A fresh sample of compound 1 was heated under vacuum at 100 °C for 2 h to obtain the dry sample (see TGA result below). The magnetic plot for this dry sample is shown in Figure 4c (2B). It surprisingly shows a distinctly different plot from sample 2A i.e., incomplete spin crossover (χMT = 1.8 cm3 K mol−1 and 2.75 cm3 K mol−1 at 250 and 360 K, respectively) with an abrupt hysteresis width of 29 K (T1/2↑ = 344 K and T1/2↓ = 315 K). It is surprising and rather unpredictable that the magnetic profiles from the two drying methods are different and suggests that another dry phase, 2B, is formed. In a further examination of the stability of the de-solvated sample, after sample 2A obtained from the SQUID measurement, it was treated in the same way as sample 2B (heating at 100 °C for 2 h under vacuum). The magnetic data do not change, red and green in Figure 4c are similar, i.e., do not mimic 2B. It is thus indicative of the stability of the sample after the de-solvation process.

In regard to the structural packing, Cl substitution has been introduced on the qsal ligand and expected to provide a variety of intermolecular interactions and enhanced cooperativities in the compounds to be reflected in the magnetism. Along this line, C–H∙∙∙Cl and P4AE interactions are present. In regard to P4AE interactions, it is believed they are responsible for hysteresis occurring in Fe(III) spin crossover. [8] Accordingly, the hysteresis width of about 30 K is observed in compound 1 but not in compound 3, the latter having an absence of P4AE interactions. This system, however, shows incomplete spin crossover. It is due to a difference in the core ligands of qsal− and thsa2− that do not support the symmetrically ordered packing originating from strong π-π interactions along the one-dimensional intermolecular chain [9].

Figure 4.

The χMT versus T plots for 1 in (a) first to third cycles and (b) third to sixth cycles and (c) comparison of the plots among different heating methods; 2A is in situ de-solvated sample, 2B is external heating sample.

Figure 4.

The χMT versus T plots for 1 in (a) first to third cycles and (b) third to sixth cycles and (c) comparison of the plots among different heating methods; 2A is in situ de-solvated sample, 2B is external heating sample.

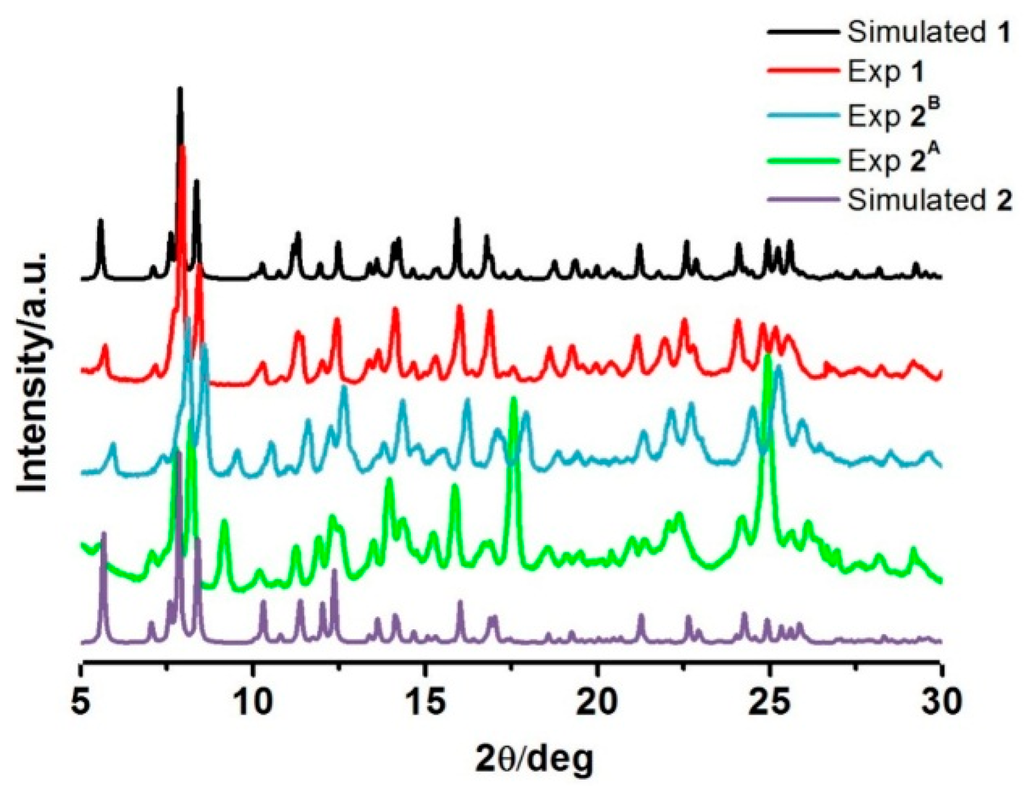

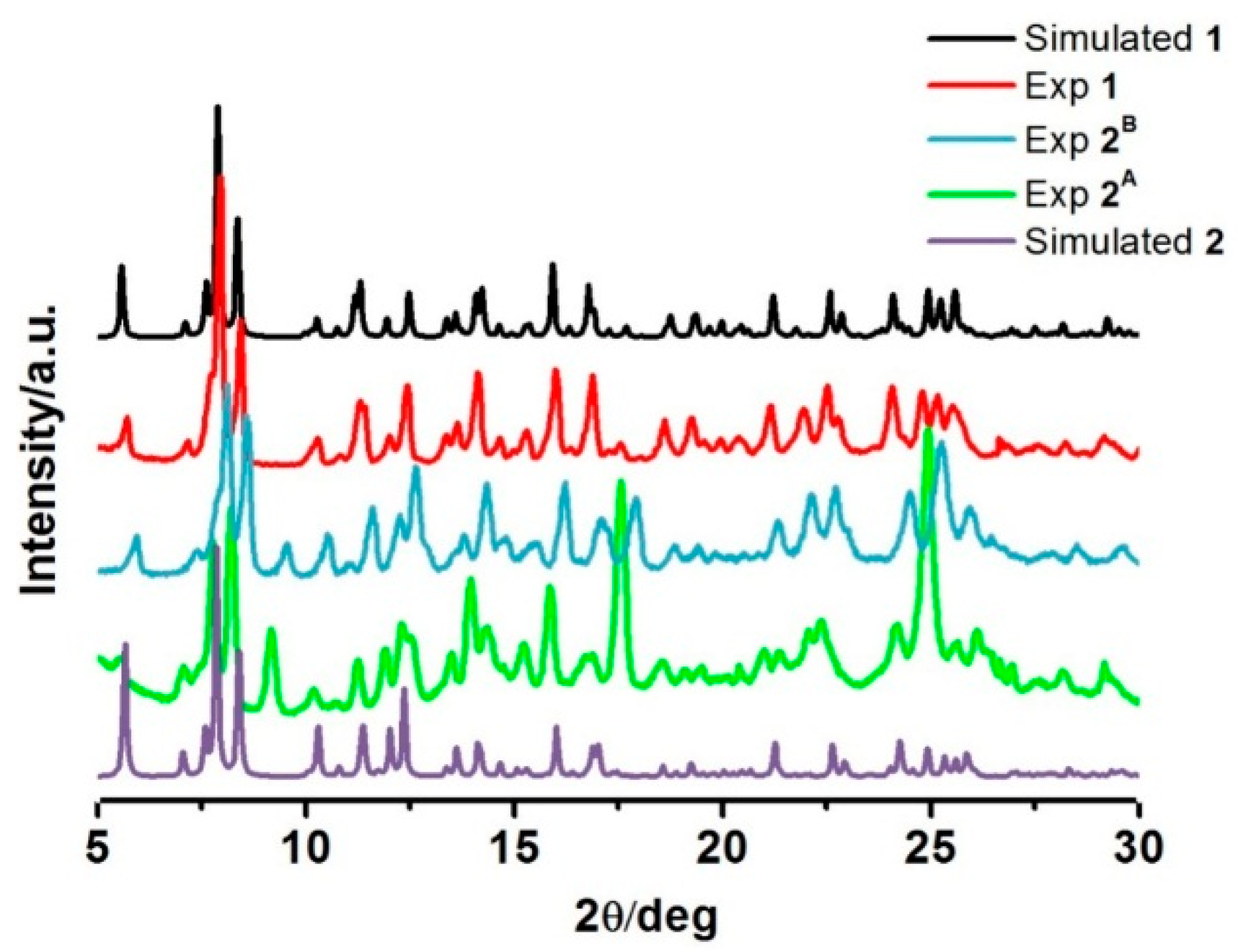

2.3. Powder Diffraction Data

As we have just seen, the magnetic properties of the two different drying-method samples, 2A and 2B, are different. PXRD was, therefore, examined to investigate the phase differences of the samples. All the experiments were performed at room temperature (Figure 5). The PXRD plot for the fresh sample of 1 agrees well with that simulated from single crystal data, suggesting the bulk sample is a pure phase. For sample 2A and 2B, the patterns are mostly similar, however there are some peaks and relative intensities at 2θ = 9°, 17°, and 25° that are distinct and pose questions about the phase resemblance/purity. However, it is understandable that the PXRD patterns of these two phases are largely identical as they are expected to maintain similar structures as the magnetic properties exhibit some similarities of the hysteresis shape. Moreover, FT-IR spectra of the compounds are also comparative (Figure S4). However, under various heating conditions, they possibly re-orientate during the de-solvation process in different fashions resulting in dissimilar structural packing. The simulated PXRD from single crystal data of de-solvated form 2 was created (Figure 5). It is interesting to note that those peaks over the abovementioned ranges in 2A and 2B are different from what was observed in this simulation pattern. This suggests that compound 1 gives rise to three de-solvated forms by different de-solvation methods i.e. under vacuum at 100 °C, dried in situ during SQUID measurement and slow evaporation in ambient conditions. Unfortunately, we do not have enough information to confirm this assumption and conclude about the structure of 2A and 2B as they all lost crystallinity after de-solvation. Thus, we are unable to get single crystal data for them. Rietveld refinements are planned to get a better understanding about the packing in 2A and 2B.

Figure 5.

PXRD patterns of the compounds in comparison with the simulated PXRD from single crystal data for 1 and 2.

Figure 5.

PXRD patterns of the compounds in comparison with the simulated PXRD from single crystal data for 1 and 2.

2.4. Mössbauer Spectroscopic Study

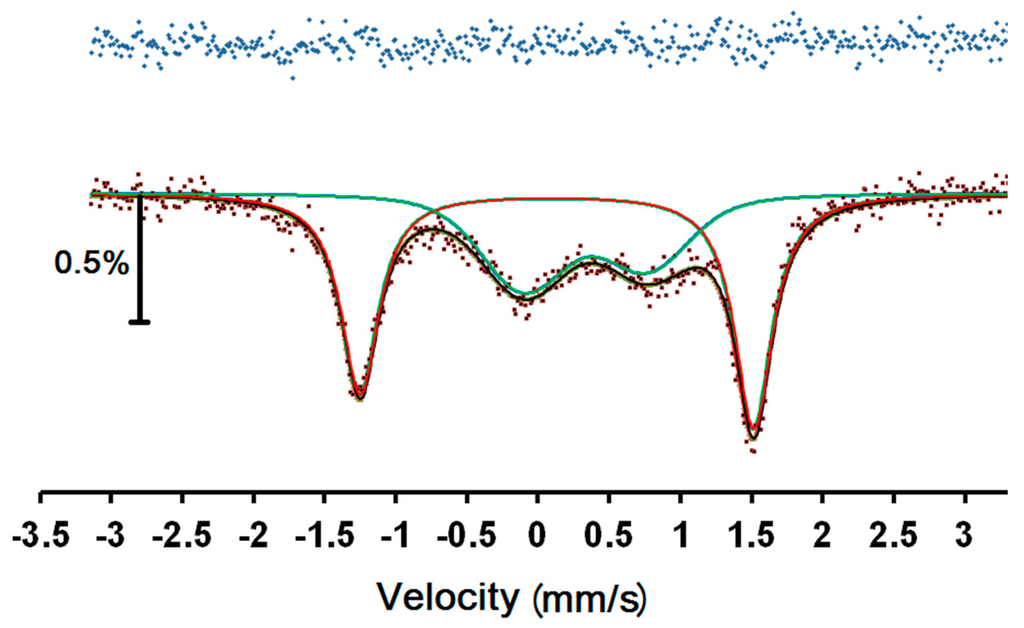

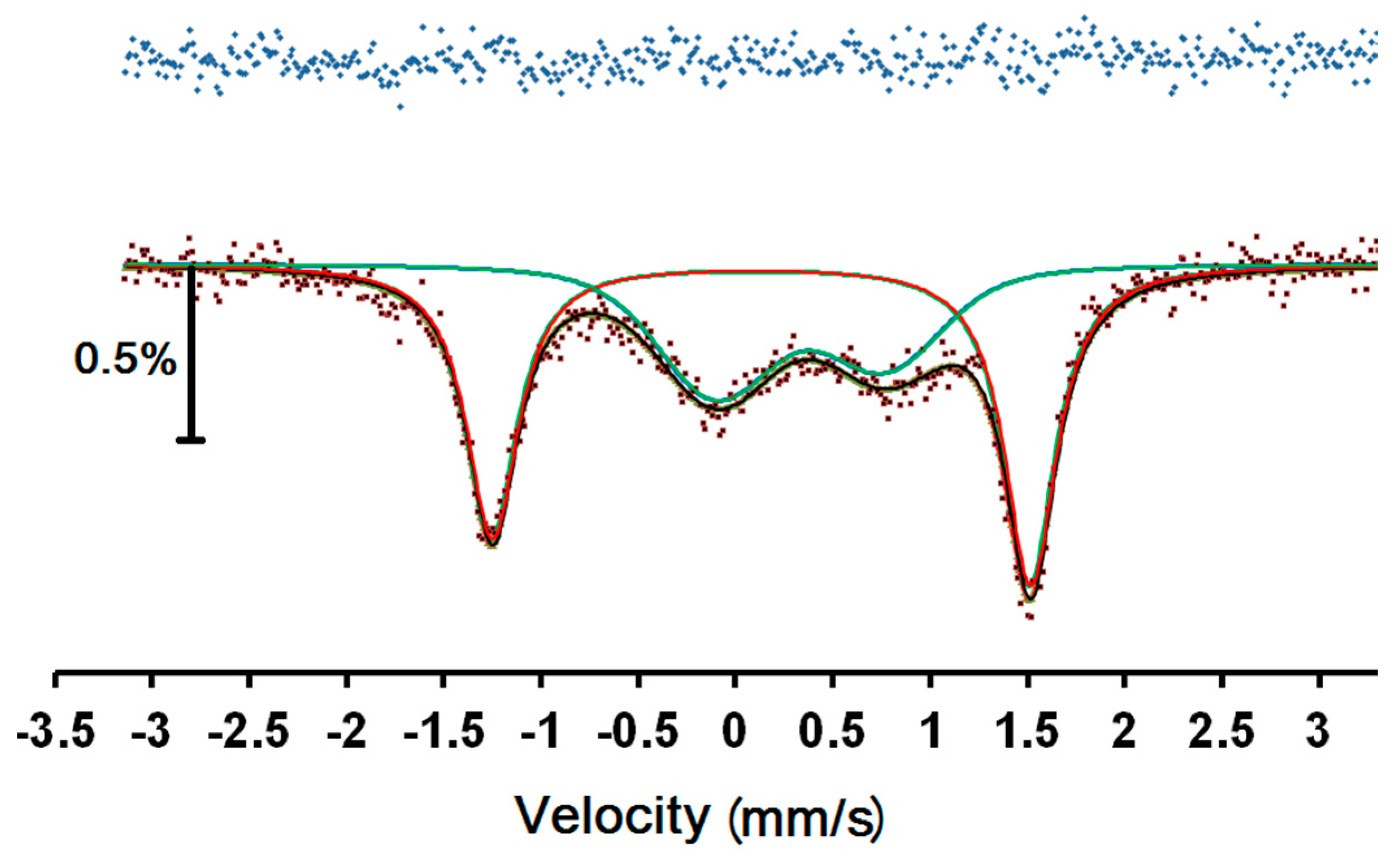

Room temperature Mössbauer spectra were taken of two fresh samples of compound 1. The first sample was allowed to drain on filter paper before being sealed in a perspex holder. The second was transferred quickly and a small drop of solvent added before sealing. The spectra were very similar consisting of two asymmetrical doublets with the inner doublet being considerably broadened.

An attempt to fit the spectra to two asymmetrical doublets showed notable misfit in the right hand outer peak. Fitting to a magnetic relaxation spectrum was much more successful and this is shown in Figure 6, with the parameters in Table 1. Since this is a magnetic spectrum, the quadrupole shift, ε, is listed, which is half the common quadrupole splitting, Δ, normally listed for doublets. The parameters are similar to those of other related Fe(III) complexes [10,11,12], with the outer doublet clearly attributable to a LS Fe(III) site and the inner doublet to a HS Fe(III) site. In Table 1, we see that the sign of the quadrupole shifts is opposite for the two sites, however the absolute value of the signs is undetermined and has been given relative to the positive value ascribed to the hyperfine magnetic field. The areas of the two sites are equal, within error, as expected from the magnetic data.

The uncertainties in both B and the relaxation frequency, f, are very large because there is very limited resolution in the slightly broadened lines. We note that the magnetic hyperfine field is much larger for the HS site, as expected. It can also be seen that the relaxation frequency of the HS site is much faster than for the LS site because of the larger magnetic moment. We note that, with the limited resolution, this determination of the relaxation frequency is not mathematically orthogonal to the determination of the linewidth, Γ, so that the considerably larger linewidth of the HS site may not necessarily be an indication of greater local disorder.

Figure 6.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of 1 at room temperature. Red and blue lines are the best fit sub-spectra for LS and HS, respectively, while the black line denotes the overall fit. The top line is the difference between the data and the fitted curve.

Figure 6.

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of 1 at room temperature. Red and blue lines are the best fit sub-spectra for LS and HS, respectively, while the black line denotes the overall fit. The top line is the difference between the data and the fitted curve.

Table 1.

57Fe Mössbauer spectral parameters for the compound 1. Values in brackets are the uncertainty in the last digit.

| Complex | Species | IS/mms−1 | ε/mms−1 | Γ/mms−1 | B/T | f/MHz | Area/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LS | 0.13(1) | −1.39(1) | 0.26(2) | 4(50) | 60(1300) | 52(2) |

| HS | 0.34(2) | 0.44(2) | 0.60(10) | 14(1500) | 310(8000) | 48(2) |

2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric (TGA) plots for the compounds have been carried out between 25 and 550 °C and are illustrated in Figure S5. For the fresh crystal of 1, it was firstly measured with the heating rate of 2 K/min. The curve shows a continuous weight loss of about 5% since the experiment started at 25 °C up to 65 °C which is believed to be the MeCN loss region. Another step mass loss takes place in the 220–280 °C region suggesting to be due to the decomposition of the compound. Another measurement with faster heating rate, 5 K/min, was performed with an expectation of gaining a better step of solvent loss. However, it still shows the continuous loss at the beginning, but with more reasonable weight loss (6.45%). This is in accordance with 0.9MeCN in the compound which is consistent with one MeCN solvent modelled from single crystal data. Heating compound 1 under vacuum at 100 °C for 2 h produces sample 2B. It is unsurprising that the data show a steady plot until 220 °C confirming the dryness of the sample.

3. Experimental Section

General: All reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd., Castle Hill, Australia) and used as received. Infrared spectra were measured with a Bruker Equinox 55 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Pty. Ltd., Preston, Australia) fitted with a 71 Judson MCT detector (Teledyne Judson Technologies LLC., Montgomeryville, PA, USA) and Specac Golden Gate (Sietronics Pty Ltd. Mitchell, Australia) diamond ATR. TGA measurements were performed using a MettlerTGA/DSC 1 (Mettler-Toledo Ltd., Port Melbourne, Australia) thermal analysis instrument at a heating rate of 2 °Cmin−1. Microanalyses were performed by Campbell Microanalytical Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. Variable-temperature magnetic susceptibility data were collected with either a Quantum Design (Quantum Design Inc, San Diego, CA, United States) MPMS 5 superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer or a MPMS XL-7 SQUID (AALTO, Finland) magnetometer, with a scan speed of 10 K min−1 followed by a one minute wait after each temperature change. In cases in which steps were less than 10 K the target temperature was reached in less than 1 min; hence it takes longer to stabilise at the target temperature. The samples were freshly moved from mother liquor to make sure that they still maintain solvent at the start of the measurement. However, there was no Vaseline mixing with the samples to prevent solvent loss. X-ray powder diffraction patterns recorded with a Bruker (Bruker Pty Ltd., Preston, Australia) D8 Advance powder diffractometer operating at Cu Kα wavelength (1.5418 Å), with samples mounted on a zero-background silicon single crystal stage. Scans were performed at room temperature in the 2θ range 5–55°.

Mössbauer spectra were recorded by using a conventional constant acceleration spectrometer, calibrated with α-Fe and with isomer shifts quoted relative to α-Fe at 295 K. Fitting was carried out by using the Recoil® software (Ken Lagarec and D G Rancourt, University of Ottawa).

X-ray crystallographic measurements were collected at the Australian Synchrotron operating at approximately 16 keV (λ = 0.71073 Å). Single crystals were mounted on a glass fibre using oil. The collection temperature, 100 K, was maintained at specified temperatures using an open-flow N2 cryostream. Data were collected using Blue Ice software. [13] Initial data processing was carried out using the XDS package. [14] CCDC numbers are 1443005 and 1443006 for compound 2 and 1, respectively.

Synthesis of [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙MeCN 1

[Fe(qsal-Cl)2]Cl [8] (0.46 g, 0.71 mmol) was dissolved in n-BuOH (35 ml) giving a dark brown suspension. A suspension of Li[Fe(thsa)2] [15] (0.32 g, 0.71 mmol) in 12 ml of MeOH was then added dropwise. The mixture was refluxed at 100 °C overnight resulting in a black solution. A black powder was precipitated after the mixture was cooled down to room temperature. The powder was filtered and dried under ambient conditions overnight (0.30 g, 75%). The product was dissolved in MeCN giving a dark brown suspension which was filtered through celite to yield a dark brown solution. The tiny black bar-shaped crystals were obtained by slow evaporation of the solution under ambient conditions. ῦmax/cm−1 3293 (υNH2), 3049 (υAr-H), 2249 (υC≡N) free CH3CN solvent, 1592 (υC=N), 1290 (υC-O), 820 (υCS) cm−1. Calcd for [Fe(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙0.5MeCN (found %) C25H18.5FeClN5.5O2S: C, 54.46 (53.71); H, 3.38 (3.34); N, 13.97 % (13.60). Partial desolvation occurs during transport for analytical studies.

4. Conclusions

The structural, magnetic, and Mössbauer effect properties of the heteroleptic complex [FeIII(qsal-Cl)(thsa)]∙MeCN, containing a Cl-substituted Schiff base chelator, have yielded detailed information on supramolecular effects and how these influence the spin crossover and cooperativity features. P4AE interactions are observed and believed to result in the hysteresis width of about 20 K. However, the different core ligands of qsal− and thsa2− prevent an occurrence of complete spin crossover in this system. The magnetic plots of χMT vs. T are unusual and interpretable in terms of mixed HS and LS states on the Fe(III) centres, these states supported by crystallographic and Mössbauer spectra, combined, importantly, by formation of de-solvated forms at higher temperatures, 300–350 K. The compound is sensitive to de-solvation methods, subsequently various phases originate from different de-solvation techniques. The nature of the de-solvated forms has been further probed by PXRD and TGA studies. Comparisons of structure-magnetism relations have been made to the unsubstituted analogue, [FeIII(qsal)(thsa)]∙0.5MeCN

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Supplementary File 2Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery grant (to KSM). Access to the Australian Synchrotron is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Petra von Koningsbruggen for early discussions on Fe(III) thiosemicarbazone compounds and for access to the thesis of Eddy W. Yemeli Tido.

Author Contributions

The experimental work was performed mainly by W.P. and assisted by D.S.M. The magnetic measurements were made by B.M. and W.P. and J.D.C made the Mössbauer measurements and fitting. K.S.M supported the work and supervised the experimental work. The manuscript was written by K.S.M, W.P. and J.D.C. All authors have given approval for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Van Koningsbruggen, P.; Maeda, Y.; Oshio, H. Iron(III) spin crossover compounds. In Spin Crossover in Transition Metal Compounds, I; Gütlich, P., Goodwin, H.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 233, pp. 259–324. [Google Scholar]

- Halcrow, M.A. (Ed.) Spin-Crossover Materials; Properties and Applications; John Wiley and Sons: London, UK, 2013.

- Phonsri, W.; Davies, C.G.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Moubaraki, B.; Murray, K.S. Spin crossover, polymorphism and porosity to liquid solvent in heteroleptic iron(III) {quinolylsalicylaldimine/thiosemicarbazone-salicylaldimine} complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchivie, M.; Guionneau, P.; Letard, J.-F.; Chasseau, D. Photo-induced spin-transition: The role of the iron(II) environment distortion. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci. 2005, 61, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, J.K.; Rheingold, A.L.; Hendrickson, D.N. Variable-temperature studies of laser-initiated 5T2 → 1A1 intersystem crossing in spin-crossover complexes: Empirical correlations between activation parameters and ligand structure in a series of polypyridyl ferrous complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 2100–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, V.; Scudder, M.; Dance, I. The crystal supramolecularity of metal phenanthroline complexes. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-León, M.; Coronado, E.; Giménez-López, M.C.; Romero, F.M. Structural, thermal, and magnetic study of solvation processes in spin-crossover [Fe(bpp)2][Cr(L)(ox)2]2·nH2O complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 11266–11276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, D.J.; Phonsri, W.; Harding, P.; Gass, I.A.; Murray, K.S.; Moubaraki, B.; Cashion, J.D.; Liu, L.; Telfer, S.G. Abrupt spin crossover in an iron(III) quinolylsalicylaldimine complex: Structural insights and solvent effects. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6340–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phonsri, W.; Martinez, V.; Davies, C.G.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Moubaraki, B.; Murray, K.S. Ligand effects in a heteroleptic bis-tridentate iron(III) spin crossover complex showing a very high T1/2 value. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, D.J.; Phonsri, W.; Harding, P.; Murray, K.S.; Moubaraki, B.; Jameson, G.N.L. Abrupt two-step and symmetry breaking spin crossover in an iron(III) complex: An exceptionally wide [LS-HS] plateau. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 15079–15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujinami, T.; Koike, M.; Matsumoto, N.; Sunatsuki, Y.; Okazawa, A.; Kojima, N. Abrupt spin transition with thermal hysteresis of iron(III) complex [FeIII(Him)2(Hapen)]AsF6 (Him = imidazole, H2Hapen = N,N′-bis(2-hydroxyacetophenylidene)ethylenediamine). Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2254–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shongwe, M.S.; Al-Rahbi, S.H.; Al-Azani, M.A.; Al-Muharbi, A.A.; Al-Mjeni, F.; Matoga, D.; Gismelseed, A.; Al-Omari, I.A.; Yousif, A.; Adams, H.; et al. Coordination versatility of tridentate pyridyl aroylhydrazones towards iron: Tracking down the elusive aroylhydrazono-based ferric spin-crossover molecular materials. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 2500–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhillips, T.M.; McPhillips, S.E.; Chiu, H.-J.; Cohen, A.E.; Deacon, A.M.; Ellis, P.J.; Garman, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Sauter, N.K.; Phizackerley, R.P.; et al. Blu-ice and the distributed control system: Software for data acquisition and instrument control at macromolecular crystallography beamlines. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2002, 9, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemeli Tido, E.W. Synthesis of Li[Fe(thsa)2] developed from that of Cs[Fe(thsa)2].4H2O. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).