Review on Legal Supervision System of the Chinese Wine Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

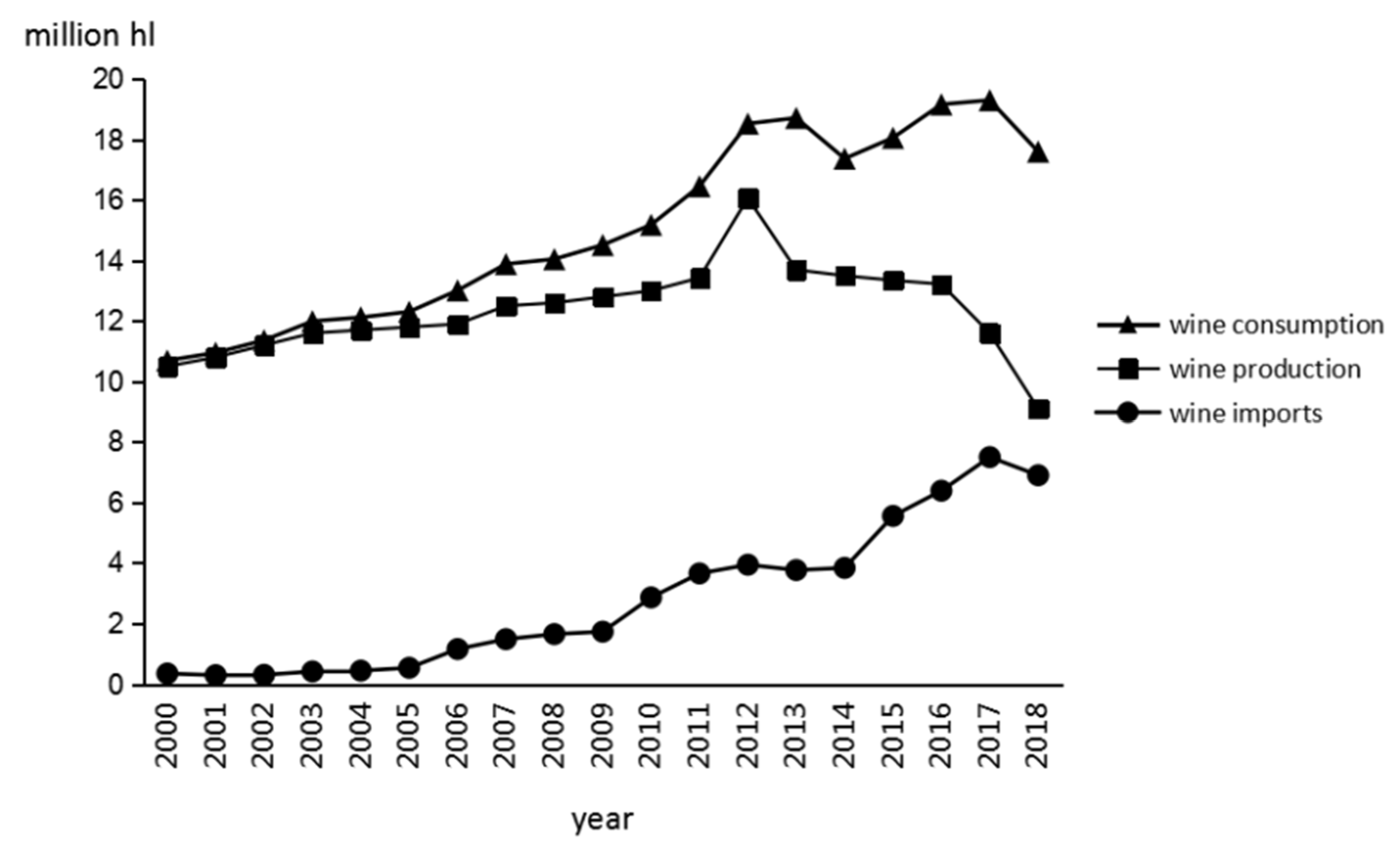

2. Development Process of China’s Wine Industry in the Past 20 Years

2.1. Production of Wine Grapes and Wine

2.2. Wine Consumption

2.3. Wine Trade

3. Chinese Laws Related to Wine

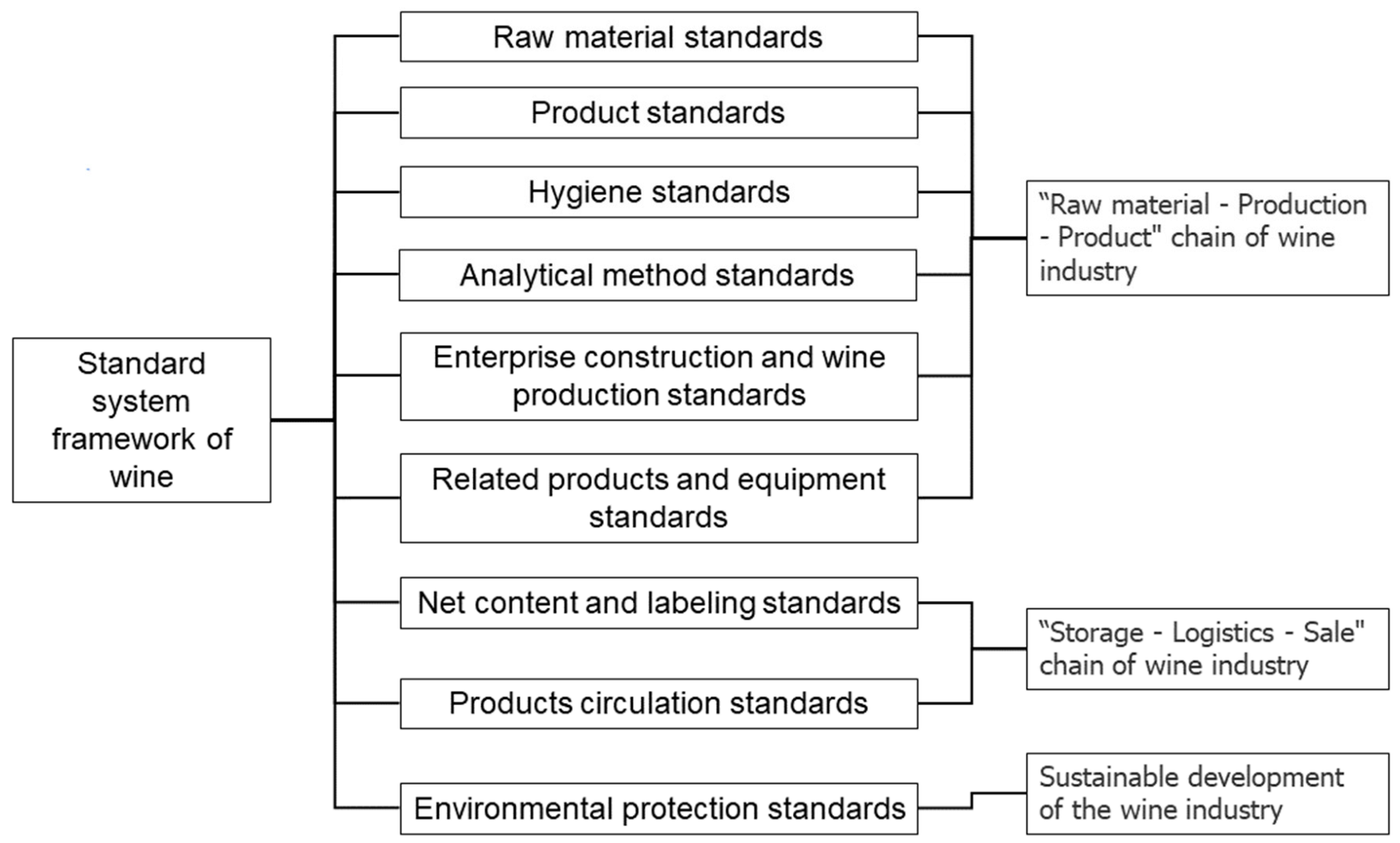

4. Wine Standard System in China

4.1. National Standards on Wine

4.1.1. Product Standards

4.1.2. Hygiene Standards

4.1.3. Analytical Method Standards

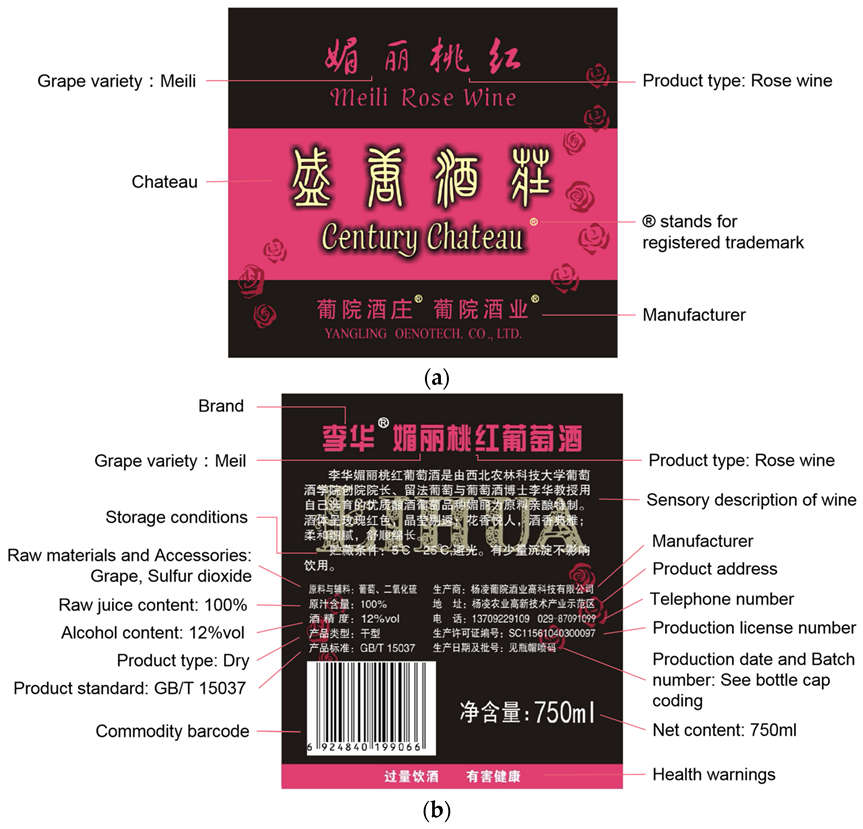

4.1.4. Net Content and Labeling Standards

4.1.5. Enterprise Construction and Wine Production Standards

4.1.6. Related Products and Equipment Standards

4.2. Sector Standards in Wine Related Industries

5. Regulations on Wine Production Management and Market Supervision

6. The Development of Wine Geographical Indications in China

7. The Proposal of Revising Chinese Wine Industry’s Supervision System

7.1. Suggestions on Brand Building of Domestic Wines

7.2. Suggestions on Testing Standard of Wine Making Process

7.3. Suggestions on Taxation of Domestic Wine

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Ning, X.; Yang, P.; Li, H. Ancient World, Old World and New World of Wine. J. Northwest A F Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 16, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y. The situation and development trend of wine standards and related regulations in China. China Brew. 2009, 8, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Yang, H. Review of Grape and Wine Industry Development in Recent 30 Years of China’s Reforming and Opening-up. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 25, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. The Development of Chinese Wine in Nearly 40 Years. Available online: https://new.qq.com/omn/20200117/20200117A0MI2400.650html (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Lu, Q.F. Research on the Development of Chinese Wine Industry in Modern Times; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Szolnoki, G. Chapter 2—Some Fundamental Facts about the Wine Market in China. In The Wine Value Chain in China; Roberta, C., Steve, C., David, M., Jingxue, J.Y., Eds.; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 15–36. ISBN 9780081007549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulia, M.; Johan, S. The Political Economy of European Wine Regulations. J. Wine Econ. 2013, 8, 244–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.X. Study on the development strategy of Ningxia wine industry—Taking the eastern foothill of Helan Mountain as an example. Ind. Technol. Forum 2017, 16, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Liu, S. Review on China Wine Market in 2013. Liquor Making 2014, 41, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- OIV. OIV 2017 Report on the World Vitivinicultural Situation. PPT Presentation. 2017. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/oiv-life/oiv-2017-report-on-the-world-vitivinicultural-situation (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- OIV. OIV 2019 Report on the World Vitivinicultural Situation. PPT Presentation. 2019. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/oiv-life/oiv-2019-report-on-the-world-vitivinicultural-situation (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Zhu, X.; Zhu, J.; Mu, W.; Feng, J. Analysis of the industrial distribution of wine in China. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine 2019, 3, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, A.; Zhou, H. Deputy to the National People’s Congress and Chairman of Changyu: Abolish Wine Consumption Tax and Change Unequal Competition between Domestic and Foreign Enterprises. The Economic Observer. 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1693361927656086009&wfr=spider&for=pc. (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Gu, Y. Reducing Taxes and Strengthening Brand Building Will Help Chinese Domestic Wines Catch a Chance to Transcend Imported Wine in Market during the Epidemics of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: http://www.cnfood.cn/hangyexinwen156652.html (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- OIV. The Situation of Vineyard, Grapes and Wine in China. OIV Data, Country Profile. 2016. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/statistiques/?year=2016&countryCode=CHN (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- OIV. Analysis of Wine Consumption in China, UK, Spain, Russia, Argentina and Australia. OIV Data, Database. 2016. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/en/statistiques/recherche (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- China Industry Information Network. Analysis of the Chinese Wine Industry (Development Process, Industrial Chain, Import and Export, Competitive, etc.) in 2020: The Industry Has Entered a Period of Adjustment. 2020. Available online: https://www.chyxx.com/industry/202001/831009.html (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Yang, H.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Discomfort terms and adjustment suggestions of Chinese wine regulation system. Food Ferment Ind. 2015, 41, 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Standardization Law of the People’s Republic of China. 2017. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-11/05/content_5237328.htm (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- The State Council of China. The Regulations for the Implementation of the Standardization Law of the People’s Republic of China; Decree of State Council (No. 53); The State Council of China: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- National Health and Family Planning Commission of China (NHFPC); The Department of China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA). Announcement Related to the Publication of National Food Safety Standards-Food Additives-Calcium Hydrophosphate (GB 1886.3-2016) and Other National Food Safety Standards and Two Standard Modification Lists; Notice of NHFPC and CFDA (No. 11); The National Health and Family Planning Commission of China and The Department of China Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- General Administration of Quality Supervision; Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China (AQSIQ); Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAC). Announcement on the Abolition of the General Standard for the Labeling of Prepackaged Alcoholic Beverage and other 13 National Standards; Notice of AQSIQ and SAC (No. 31); The General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine and Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.C. Discussion on the development strategy of China’s wine industry. China Brew. 2008, 11, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Tie, J. Legislation to fill the gap of alcohol supervision in Our province. Jilin People’s Congr. 2008, 8, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Gao, J. Study on the Value and Protection of Chinese Wine Geographical Indication. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Fang, Y.L. Study on the mode of sustainable viticulture: Quality, stability, longevity and beauty. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2005, 23, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.M. Ningxia Wine “when shocking the world”. Int. Bus. Dly. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L.; Ouyang, S. The Chinese Wine Industry. In The Palgrave Handbook of Wine Industry Economics; Alonso Ugaglia, A., Cardebat, J.M., Corsi, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prospects Industrial Research Institute. Market Analysis of Chinese Wine Industry in 2021: Wine Market Downturn Reason Analysis, Market Still has the Opportunity to Pick Up. 2021. Available online: https://bg.qianzhan.com/trends/detail/506/210817-4dc59237.html (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Yu, J.; China Wine Industry Development Status and Import and Export Situation Analysis in 2020. Winesinfo. 2021. Available online: https://www.winesinfo.com/html/2021/4/12-84409.html (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Zhen, Y.X.; Two Sessions- Jiang Ming, NPC Deputy and Chairman of Tianming: It is Suggested to Increase the Support for Chinese Wine Brand Construction. Economic Observer Network. 2022. Available online: http://www.eeo.com.cn/2022/0305/524244.shtml (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Zhu, K.Z.; Wang, C.P.; Zhen, L. Analysis of applicable laws and regulation of wine estate and discussion on construction of standard system. Sino-Overseas Grapevine Wine 2021, 21, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.H.; Lin, Z.S. Research on existing problems and countermeasures of winery system in Ningxia. Commer. Econ. 2020, 2, 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- China Food Network. The Guidelines for the Development of China’s Wine Industry in the 14th Five-Year Plan are Released. 2021. Available online: http://food.china.com.cn/2021-04/09/content_77392532.htm (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluation of Certain Food Contaminants: Sixty-Fourth Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. WHO Technical Report Series No. 930; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2006. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_930_eng.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Liu, J.; Ren, J.; Sun, K.J. Research progress on the safety of biogenic amines in foods. Food Sci. 2013, 34, 322–326. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, T.M.; Zhong, Q.; Fan, S. What’s in a wine?—A spot check of the integrity of European wine sold in China based on anthocyanin composition, stable isotope and glycerol impurity analysis. Food Addit. Contam.-Part A Chem. Anal. Control. Expo. Risk Assess. 2021, 38, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| GB 15037-2006 | Wines | former General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China (AQSIQ) and Standardization Administration of China (SAC) |

| GB/T 11856-2008 | Brandy | |

| GB/T 27586-2011 | Vitis amurensis wines | |

| GB/T 25504-2010 | Icewines | |

| GB/T 18966-2008 | Product of geographical indication—Yantai wines | |

| GB/T 20820-2007 | Product of geographical indication—Tonghua amur-wine | |

| GB/T 19504-2008 | Product of geographical indication—Wine in Helan mountain east region | |

| GB/T 19049-2008 | Product of geographical indication—Changli wine | |

| GB/T 19265-2008 | Product of geographical indication—Shacheng Wine | |

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| GB 2758-2012 | National food safety standards—Fermented alcoholic beverages and their integrated alcoholic beverages | former Ministry of Health of China |

| GB 2757-2012 | National food safety standards—Distilled alcoholic beverages and their integrated alcoholic beverages | former Ministry of Health of China |

| GB 2760-2014 | National food safety standards— Use of food additives | former National Health and Family Planning Commission of China (NHFPC) |

| GB 2761-2017 | National food safety standards—Maximum levels of mycotoxins in foods | former NHFPC; former China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) |

| GB 2762-2017 | National food safety standards—Maximum levels of contaminants in foods | former NHFPC former CFDA |

| GB 2763-2021 | National food safety standards—Maximum residue limits for pesticide in food | National Health Commission of China; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs; State Administration for Market Regulation |

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| GB/T 15038-2006 | Analytical methods of wine and fruit wine | former AQSIQ; SAC |

| GB 5009.225-2016 | National food safety standards—Determination of ethanol concentration in alcoholic beverages | former NHFPC |

| GB 5009.266-2016 | National food safety standards—Determination of methanol in foods | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| GB 5009.28-2016 | National food safety standards—Determination of benzoic acid, sorbic acid, and saccharin sodium in foods | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| GB 5009.13-2017 | National food safety standards—Determination of copper in foods | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| GB 5009.96-2016 | National food safety standards—Determination of Ochratoxin A in foods | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| GB 5009.12-2017 | National food safety standards—Determination of Plumbum in foods | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| GB 4789.1-2016 | National food safety standards—General rules for microbiological testing of food | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| GB/T 4789.25-2003 | Microbiological examination of food hygiene—Examination of wines | former Ministry of Health of China; SAC |

| GB/T 5009.49-2008 | Method for analyzing the hygienic standard of fermented alcoholic beverages and their integrated alcoholic beverages | former Ministry of Health of China; SAC |

| GB 23200.14-2016 * | National food safety standards—Determination of 512 pesticides residues in fruit juice, vegetable juice, and fruit wine—Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry | former NHFPC; former Ministry of Agriculture; former CFDA |

| GB 23200.7-2016 * | National food safety standards—Determination of 497 pesticides and related chemicals residues in honey, fruit juice, and wine—Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry | former NHFPC; former Ministry of Agriculture; former CFDA |

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| JJF 1070-2005 | Rules of metrological testing for the net quantity of products in prepackages with fixed content | former AQSIQ |

| GB 7718-2011 | National food safety standards—General standard for the labeling of prepackaged foods | former Ministry of Health of China |

| GB/T 191-2008 | Packaging—Pictorial marking for the handling of goods | former AQSIQ; SAC |

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| GB 12696-2016 | National food safety standards—Hygiene specifications of production for fermented alcoholic beverages and their integrated alcoholic beverages | former NHFPC; former CFDA |

| GB 14881-2013 | National food safety standards—General Hygiene specifications for food production | former NHFPC |

| GB/T 23543-2009 | Good manufacturing practice for wine enterprises | former AQSIQ; SAC |

| GB 50694-2011 | Code for design of fire protection and prevention of alcoholic beverages factory | Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development; former AQSIQ |

| GB/T 36759-2018 | Implementation guidelines for traceability of wine production | State Administration for Market Regulation; SAC |

| GB/T 31280-2014 | Brand valuation—Alcohol, drink, and refined tea manufacturing industry | former AQSIQ; SAC |

| Standard | Issuing Unit | |

|---|---|---|

| GB/T 23778-2009 | Cylindrical cork stoppers for alcohol and another food packaging | former AQSIQ; SAC |

| GB/T 23777-2009 | Wine cooler | |

| GB/T 25393-2010 | Equipment for vine cultivation and winemaking—Grape harvesting machinery—Test method | |

| GB/T 25394-2010 | Equipment for vine cultivation and winemaking Mash pumps—Methods of test | |

| GB/T 25395-2010 | Equipment for vine cultivation and winemaking—Grape presses—Methods of test | |

| Sector | Standard | Issuing Unit | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | NY/T 2682-2015 Technical regulations for wine grape production | former Ministry of Agriculture | Raw material standard |

| NY/T 3103-2017 Grapes for processing | |||

| NY/T 274-2014 Green food—Wine | former Ministry of Agriculture | Product standard | |

| Certification and accreditation | RB/T 167-2018 Technical specification for processing of organic wine | Certification and accreditation administration of China | Enterprise construction and wine production standards |

| Work Safety | WS 710-2012 Technical requirement of dust and poison control for wine production enterprises | former State Administration of Work Safety | |

| Packaging | BB/T 0018-2000 Packaging containers-wine bottle | China National Packaging Corporation | Related products |

| Logistics | WB/T 1053-2015 Management requirements for information traceability in the logistics of alcoholic products | National Development and Reform Commission | Products circulation standards |

| Environmental Protection | HJ 452-2008 Cleaner production standard—Wine industry | former Ministry of Environmental Protection | Environmental protection standards |

| HJ 1028-2019 Technical specification for application and issuance of pollutant permit—Wine and beverage manufacturing industry | Ministry of Ecology and Environment | ||

| HJ 1085-2020 Self-monitoring technology guidelines for pollution sources—Alcohol products and beverage manufacturing industry | |||

| Domestic trade | SB/T 10391-2005 Management standard for alcohol commodities wholesale | Ministry of Commerce | Products circulation standards |

| SB/T 10392-2005 Management standard for alcohol commodities retail | |||

| SB/T 10710-2012 Circulate terminology for alcohol products | |||

| SB/T 10711-2012 Technical regulation on circulation of bulk wines | |||

| SB/T 10712-201 Technical regulation on transportation and storage of wines | |||

| SB/T 11122-2015 Norm on the terminology of imported wines | |||

| SB/T 11000-2013 The standard of circulation and service for the alcohol industry | |||

| SB/T 11196-2017 Service standard for imported wine business | |||

| SB/T 11123-2015 Management specification of china enterprise alcoholic products distribution | |||

| Light industry * | QB/T 5299-2018 Determination of the 13C/12C isotope ratio of glycerol in wines—Method using liquid chromatography coupled to isotope ratio mass spectrometry | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology | Analytical method standards |

| Entry-exit inspection and quarantine * | SN/T 4675.31-2019 Determination of carbon stable isotope ratio of glycerol in wine for export—LC-IRMS method | General Administration of Customs, P.R.C |

| Regulation | Department | Entry into Force |

|---|---|---|

| Measures for food production licensing | State Administration for Market Regulation | 1 March 2020 |

| Rules for the implementation of food quality certification—Alcohol | Certification and Accreditation Administration of China | 13 September 2005 |

| Detailed rules of grape wine and fruit wine production license review | former AQSIQ | 1 January 2005 |

| Measures for the management of wine production (trial) | former State Light Industry Bureau | 19 December 2000 |

| Technical specification for grape wine making in China | former State Economic and Trade Commission | 1 January 2003 |

| Alcohol commodities wholesale business management practices | Ministry of Commerce | 1 July 2005 |

| Alcohol commodities retail business management practices | Ministry of Commerce | 1 July 2005 |

| Measures for the management of consumption tax on wine(trial) | State Taxation Administration | 1 July 2006 |

| Announcement on case-filing for anti-dumping investigation against wines | Ministry of Commerce | 1 July 2013 |

| Announcement on case-filing for anti-subsidy investigation against wines | Ministry of Commerce | 1 July 2013 |

| GI Protection Products | AQSIQ Question Mork | Announcement Time |

|---|---|---|

| ChangLi Wine | (2002) 73 (2005) 105 (extend the scope) | 6 August 2002 17 October 2005 |

| YanTai Wine | (2002) 83 | 28 August 2002 |

| ShaCheng Wine | (2002) 125 | 9 December 2002 |

| Helan Mountain East Region Wine | (2003) 32 (2011) 14 (extend the scope) | 11 April 2003 30 January 2011 |

| TongHua Amur-Wine | (2005) 186 | 28 December 2005 |

| HuanRen Ice Wine | (2006) 221 | 31 December 2006 |

| Hexi Corridor Wine | (2012) 111 | 31 July 2012 |

| DuAn Wild Amur-Wine | (2013) 167 | 12 December 2013 |

| Rongzi Winery Wine | (2013) 175 | 23 December 2013 |

| YanJing Wine | (2014) 136 | 11 December 2014 |

| Turpan Wine | (2015) 143 | 4 December 2015 |

| Pegatron Wine | (2015) 143 | 4 December 2015 |

| YunXi Amur-Wine | (2017) 39 | 31 May 2017 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, C.; Song, R.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Review on Legal Supervision System of the Chinese Wine Industry. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8050432

Yang C, Song R, Ding Y, Zhang L, Wang H, Li H. Review on Legal Supervision System of the Chinese Wine Industry. Horticulturae. 2022; 8(5):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8050432

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Chenlu, Rui Song, Yinting Ding, Liang Zhang, Hua Wang, and Hua Li. 2022. "Review on Legal Supervision System of the Chinese Wine Industry" Horticulturae 8, no. 5: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8050432

APA StyleYang, C., Song, R., Ding, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, H., & Li, H. (2022). Review on Legal Supervision System of the Chinese Wine Industry. Horticulturae, 8(5), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8050432