Soilless Tomato Production: Effects of Hemp Fiber and Rock Wool Growing Media on Yield, Secondary Metabolites, Substrate Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation of Tomato Plants and Assessment of Crop Growth and Yield

2.2. Analysis of Substrate Characteristics Using Water Retention Curves (pF-Curves)

2.3. Determination of Substrate Decomposition during Cultivation Period

2.4. N-Immobilization

2.5. Analysis of Greenhouse Gases Released by Growing Media

2.6. Sample Preparation for Chemical Analyses and Determination of Dry Matter and Soluble Solid Content

2.7. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

2.8. Analysis of Carotenoids

2.9. Analysis of the Mineral Composition of Tomato Fruits and Leaves

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Substrate Characteristics

3.1.1. Water Retention Curves

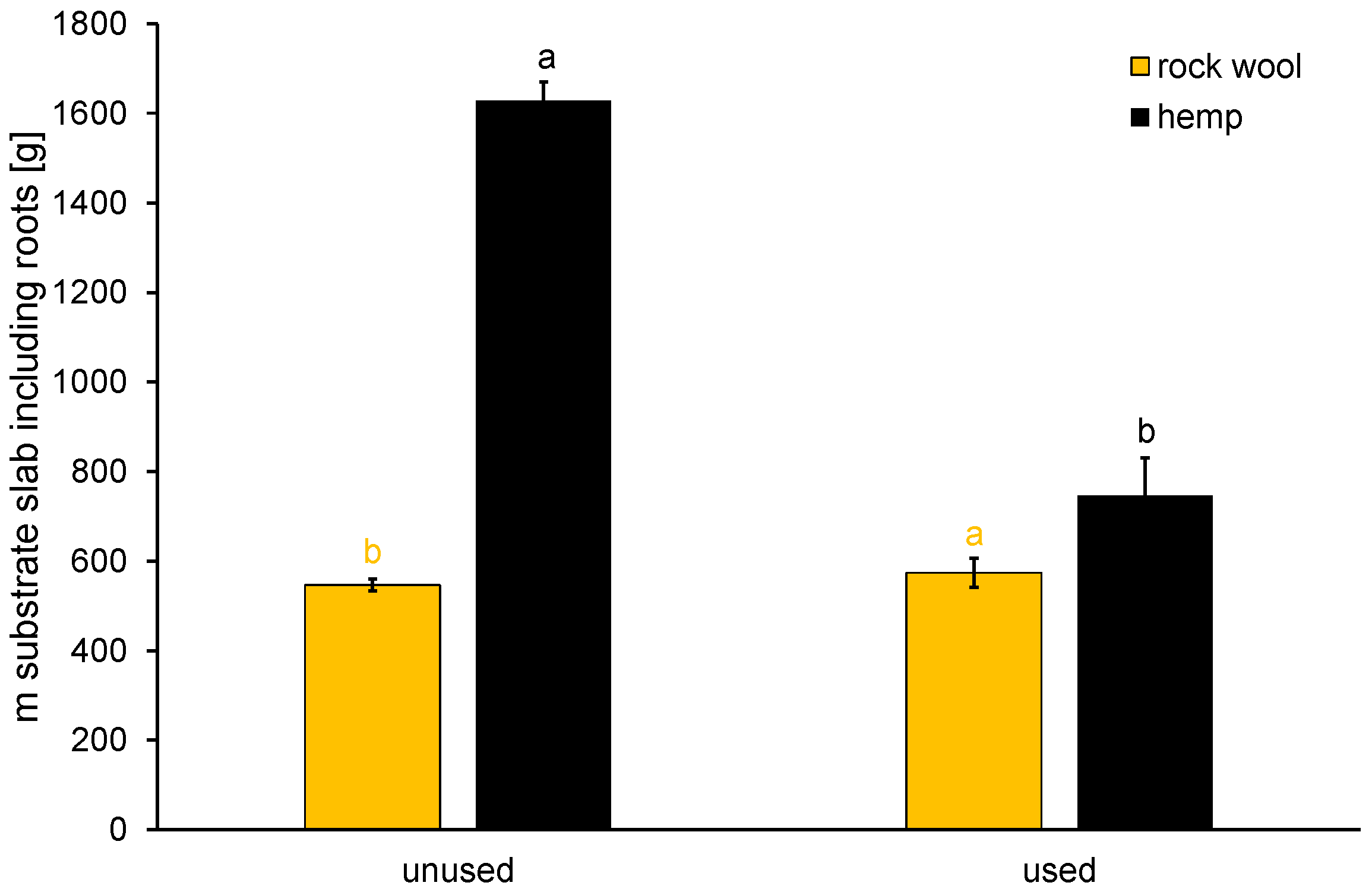

3.1.2. Stability of Hemp towards Decomposition

3.1.3. N-Immobilization in Hemp Fiber Bags

3.1.4. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Released by Hemp and Rock Wool

3.2. Determination of Plant Growth Parameters

3.3. Mineral Composition of Leaves and Fruits of Tomato Plants

3.4. Effects of Different Growing Media on Quality Parameters of Tomato Fruits

3.4.1. SSC and Dry Matter Content of Tomato Fruits

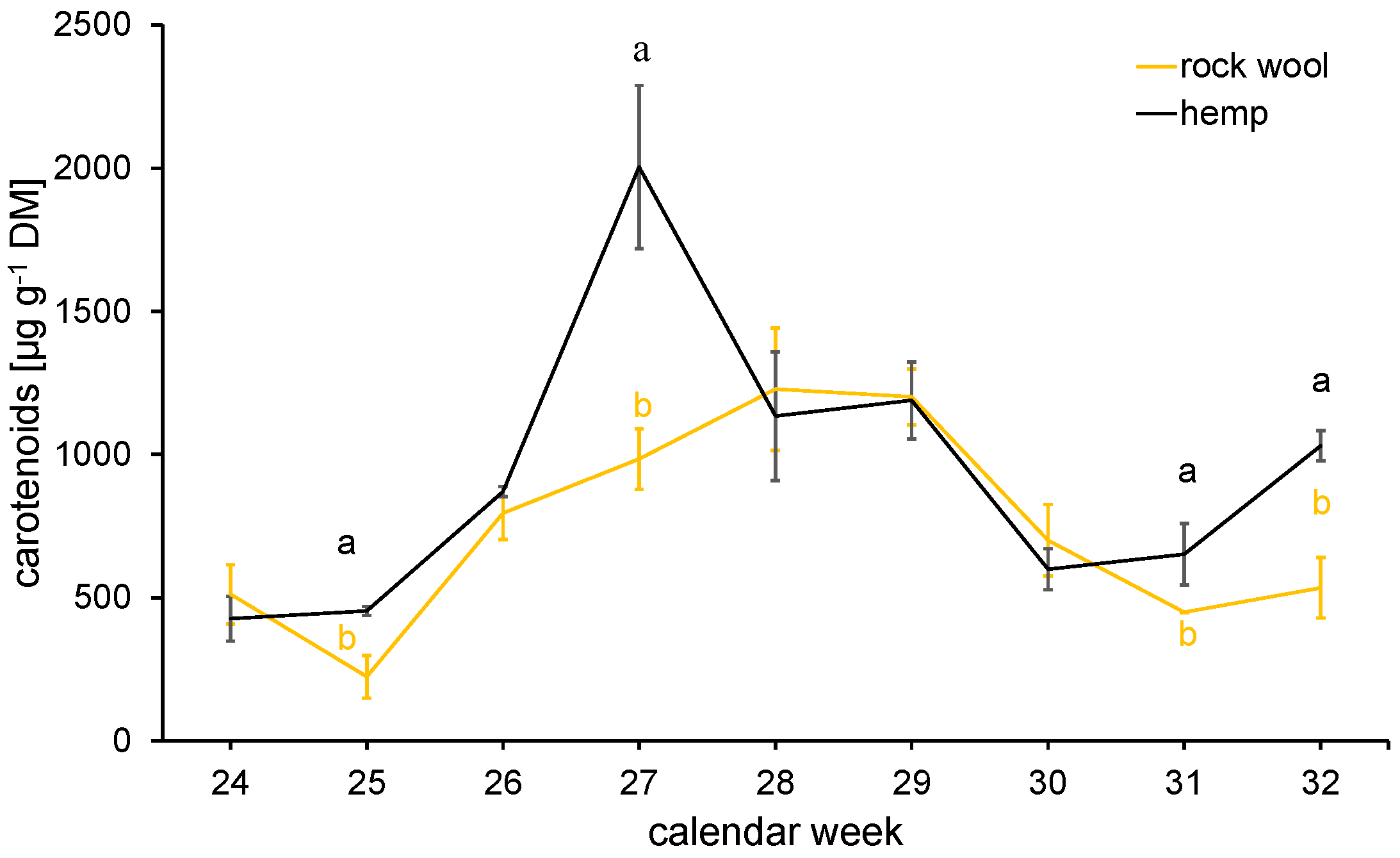

3.4.2. Secondary Metabolites—Contents of Carotenoids

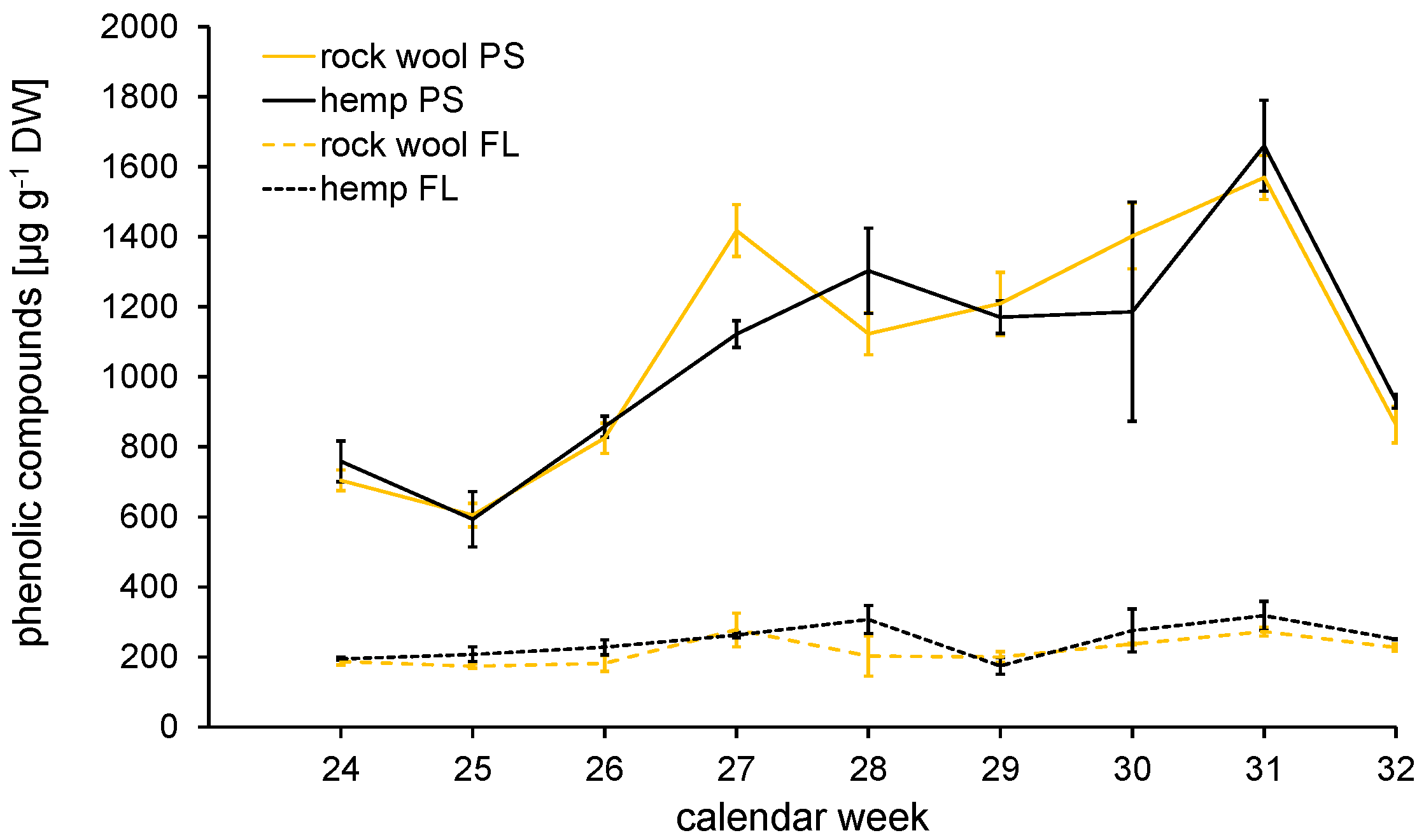

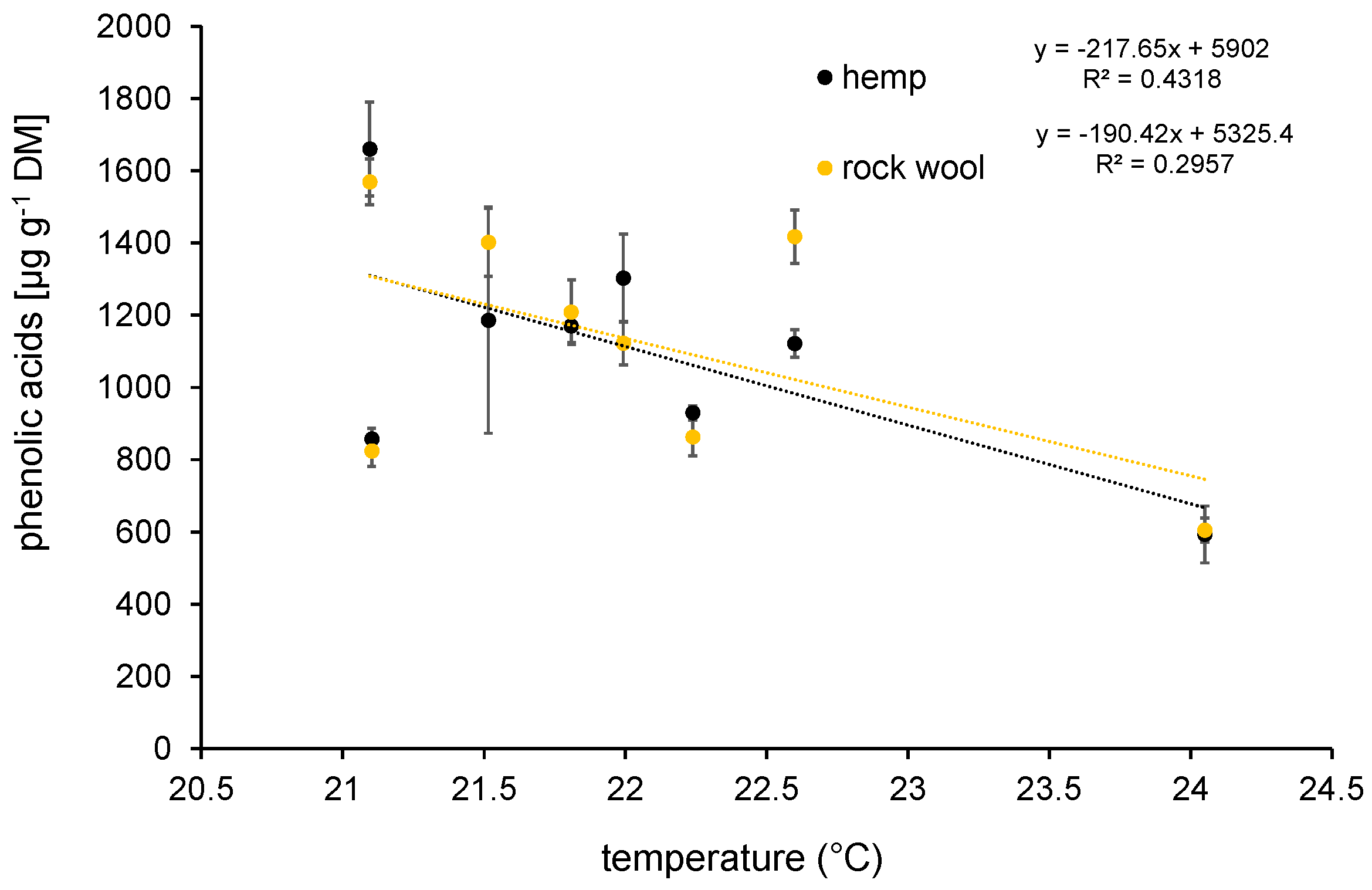

3.4.3. Secondary Metabolites—Contents of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNFPA. State of World Population 2011. People and Possibilities in a World of 7 Billion; Information and External Relations Division of the United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352); Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land. An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, G.W. International Greenhouse Vegetable Production-Statistics (2018 Edition); Cuesta Roble Consulting: Mariposa, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, A.Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, W.; Meyerson, L.A.; Gu, B.J.; Peng, C.H.; Ge, Y. Assessment of net ecosystem services of plastic greenhouse vegetable cultivation in China. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Harjunowibowo, D.; Cuce, P.M. Renewable and sustainable energy saving strategies for greenhouse systems: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2016, 64, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruda, N.; Bisbis, M.; Tanny, J. Impacts of protected vegetable cultivation on climate change and adaptation strategies for cleaner production—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruda, N.; Bisbis, M.; Tanny, J. Influence of climate change on protected cultivation: Impacts and sustainable adaptation strategies—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elings, A.; Kempkes, F.L.K.; Kaarsemaker, R.C.; Ruijs, M.N.A.; Van de Braak, N.J.; Dueck, T.A. The energy balance and energy-saving measures in greenhouse tomato cultivation. Acta Hortic. 2004, 691, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benoit, F.; Ceustermans, N. Horticultural Aspects of ecological soilless growing methods. Acta Hortic. 1995, 396, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussell, W.T.; Mckennie, S. Rockwool in horticulture, and its importance and sustainable use in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Crop. Hort. 2004, 32, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.R.; Hwang, S.J. Use of recycled hydroponic rockwool slabs for hydroponic production of cut roses. Acta Hortic. 2000, 554, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, Y.; Hata, T.; Maruo, T.; Hohjo, M.; Ito, T. Chemical and physical properties of the Coconut-Fibre substrate and the growth and productivity of Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) plants. Acta Hortic. 1999, 481, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, J.; Van Assche, B.; Buekens, A. Reducing solid waste streams specific to soilless horticulture. HortTechnology 1998, 8, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Destatis. Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Fischerei. Gemüseerhebung: Anbau und Ernte von Gemüse und Erdbeeren; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 2–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brandhorst, J.; Spritzendorfer, J.; Gildhorn, K.; Hemp, M. Dämmstoffe aus nachwachsenden Rohstoffen. In Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe e.V., 4th ed.; FNR, Ed.; Druckerei Weidner: Rostock, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, M.; Noguera, P. Los sustratos en los cultivos sin suelo. In Manual del Cultivo Sin Suelo; Urrestarazu, M., Ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones Universidad de Almeria, Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2000; pp. 137–183. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, M.; Martinez, P.F.; Martinez, M.D.; Martinez, J. Evaluacio´n agrono´mica de los sustratos de cultivo. Actas Hortic. 1993, 11, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- De Boodt, M.; Verdonck, O. The physical properties of the substrates in horticulture. Acta Hortic. 1972, 26, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boertje, G.A. Physical laboratory analyses of potting composts. Acta Hortic. 1983, 150, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.R.; Jarrell, W.M. Predicting physical and chemical properties of container mixtures. HortScience 1998, 24, 292–295. [Google Scholar]

- Allaire, S.E.; Caron, J.; Menard, C.; Dorais, M. Potential replacements for rockwool as growing substrate for greenhouse tomato. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2005, 85, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.K.; Davidson, E.A. Microbiological basis of NO and N2O production and consumption in soil. In Exchange of Trace Gases between Terrestrial Ecosystems and the Atmosphere; Andreae, M.O., Schimel, D.S., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 47, pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Karlowsky, S.; Gläser, M.; Henschel, K.; Schwarz, D. Seasonal nitrous oxide emissions from hydroponic tomato and cucumber cultivation in a commercial greenhouse company. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, M.E.; Daniell, T.J.; Baggs, E.M. Compound driven differences in N2 and N2O emission from soil; the role of substrate use efficiency and the microbial community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 106, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, N.; Baggs, E.M. Carbon and oxygen controls on N2O and N2 production during nitrate reduction. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mer, J.; Roger, P. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2001, 37, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannehl, D.; Suhl, J.; Ulrichs, C.; Schmidt, U. Evaluation of substitutes for rock wool as growing substrate for hydroponic tomato production. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2015, 88, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrestarazu, M.; Martinez, G.A.; Salas, M.D. Almond shell waste: Possible local rockwool substitute in soilless crop culture. Sci. Hortic. 2005, 103, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manios, V.I.; Papadimitriou, M.D.; Kefakis, M.D. Hydroponic culture of Tomato and Gerbera at different substrates. Acta Hortic. 1995, 408, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.F.; Abad, M. Soilless culture of Tomato in different Mineral Substrates. Acta Hortic. 1992, 323, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruda, N.; Rau, B.J.; Wright, R.D. Laboratory bioassay and greenhouse evaluation of a pine tree substrate used as a container substrate. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2009, 74, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Göhler, F.; Molitor, H.D. Erdelose Kulturverfahren im Gartenbau; Ulmer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dannehl, D.; Rocksch, T.; Schmidt, U. Modelling to estimate the specific leaf area of tomato leaves (‘Pannovy’). Acta Hortic. 2015, 1099, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDLUFA. Methodenbuch Band I-Die Untersuchungen von Böden, Method A 13.5.1, Stabilität N-Haushalt, 5th ed.; VDLUFA-Verlag: Darmstadt, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, N.; Ulrichs, C.; Schreiner, M.; Arndt, N.; Schmidt, R.; Mewis, I. Ecotype Variability in Growth and Secondary Metabolite Profile in Moringa oleifera: Impact of Sulfur and Water Availability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2852–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageney, V.; Baldermann, S.; Albach, D.C. Intraspecific variation in carotenoids of Brassica oleracea var. sabellica. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 3251–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. R Package Version 1.3-2. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Fuss, R. Gasfluxes: Greenhouse Gas Flux Calculation from Chamber Measurements, 0.4-4. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gasfluxes/gasfluxes.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Hothorn, T.; Hornik, K.; Wiel, M.A.v.d.; Zeileis, A. Implementing a Class of Permutation Tests: The coin Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veen, B.; Van Noordwijk, M.; De Willigen, P.; Boone, F.; Kooistra, M. Root-soil contact of maize, as measured by a thin-section technique. Plant Soil 1992, 139, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonck, O. New developments in the use of graded perlite in the horticultural substrates. Acta Hortic. 1983, 150, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Khan, S.; Ito, T.; Maruo, T.; Shinohara, Y. Characterization of the physico-chemical properties of environmentally friendly organic substrates in relation to rockwool. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2002, 77, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martius, C. Decomposition of wood. In The Central Amazon Floodplain; Junk, W.J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; Volume 126, pp. 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gruda, N.; Schnitzler, W.H. Suitability of wood fiber substrate for production of vegetable transplants-I. Physical properties of wood fiber substrates. Sci. Hortic. 2004, 100, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruda, N.; von Tucher, S.; Schnitzler, W.H. N-immobilization by wood fibre substrates in the production of tomato transplants (Lycopersicon lycopersicum (L.) Karst. ex Farw.). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2000, 74, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Daum, D.; Schenk, M.K. Gaseous nitrogen losses from a soilless culture system in the greenhouse. Plant Soil 1996, 183, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashida, S.-n.; Johkan, M.; Kitazaki, K.; Shoji, K.; Goto, F.; Yoshihara, T. Management of nitrogen fertilizer application, rather than functional gene abundance, governs nitrous oxide fluxes in hydroponics with rockwool. Plant Soil 2014, 374, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, T.; Tokura, A.; Hashida, S.-n.; Kitazaki, K.; Asobe, M.; Enbutsu, K.; Takenouchi, H.; Goto, F.; Shoji, K. A Precise/Short-interval Measurement of Nitrous Oxide Emission from a Rockwool Tomato Culture. Environ. Control Biol. 2014, 52, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dennis, P.G.; Miller, A.J.; Hirsch, P.R. Are root exudates more important than other sources of rhizodeposits in structuring rhizosphere bacterial communities? FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 72, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stucki, M.; Wettstein, S.; Mathis, A.; Amrein, S. Erweiterung der Studie Torf und Torfersatz-produkte im Vergleich: Eigenschaften, Verfügbarkeit, ökologische Nachhaltigkeit und soziale Auswirkungen; Institut für Umwelt und Natürliche Ressourcen, Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften: Wädenswil, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 3–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Gea, T.; Barrena, R.; Gabriel, D.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.Á.; Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L.; Mondini, C. Greenhouse gas emissions from organic waste composting. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2015, 13, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chérif, M.; Tirilly, Y.; Bélanger, R.R. Effect of oxygen concentration on plant growth, lipidperoxidation, and receptivity of tomato roots to Pythium F under hydroponic conditions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1997, 103, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.N.; Hobson, G.E.; McGlasson, W.B. The constituents of tomato fruit—the influence of environment, nutrition, and genotype. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 1981, 15, 205–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, N.; Guichard, S.; Leonardi, C.; Longuenesse, J.J.; Langlois, D.; Navez, B. Seasonal evolution of the quality of fresh glasshouse tomatoes under Mediterranean conditions, as affected by air vapour pressure deficit and plant fruit load. Ann. Bot. 2000, 85, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, C.; Logendra, L.; Lee, T.C.; Janes, H. Characteristics of 10 processing tomato cultivars grown hydroponically for the NASA Advanced Life Support (ALS) Program. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2004, 17, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, P.R.; Hartz, T.K.; LeStrange, M.; Nunez, J.J.; Miyao, E.M. Managing Fruit Soluble Solids with Late-season Deficit Irrigation in Drip-irrigated Processing Tomato Production. Hortscience 2005, 40, 1857–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verheul, M.J.; Slimestad, R.; Tjøstheim, I.H. From producer to consumer: Greenhouse tomato quality as affected by variety, maturity stage at harvest, transport conditions, and supermarket storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 5026–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guichard, S.; Bertin, N.; Leonardi, C.; Gary, C. Tomato fruit quality in relation to water and carbon fluxes. Agronomie 2001, 21, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, B.; Martinez-Garcia, J.F.; Stange, C.; Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. Illuminating colors: Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis and accumulation by light. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 37, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, Y.; Dadomo, M.; Di Lucca, G.; Grolier, P. Effects of environmental factors and agricultural techniques on antioxidant content of tomatoes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénard, C.; Gautier, H.; Bourgaud, F.; Grasselly, D.; Navez, B.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Weiss, M.; Génard, M. Effects of low nitrogen supply on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit yield and quality with special emphasis on sugars, acids, ascorbate, carotenoids, and phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4112–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanasca, S.; Colla, G.; Maiani, G.; Venneria, E.; Rouphael, Y.; Azzini, E.; Saccardo, F. Changes in antioxidant content of tomato fruits in response to cultivar and nutrient solution composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4319–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäckel, U.; Schnell, S.; Conrad, R. Microbial ethylene production and inhibition of methanotrophic activity in a deciduous forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q. Regulation of carotenoid metabolism in tomato. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marty, I.; Bureau, S.; Sarkissian, G.; Gouble, B.; Audergon, J.; Albagnac, G. Ethylene regulation of carotenoid accumulation and carotenogenic gene expression in colour-contrasted apricot varieties (Prunus armeniaca). J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1877–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lara, L.J.; Egea-Gilabert, C.; Niñirola, D.; Conesa, E.; Fernández, J.A. Effect of aeration of the nutrient solution on the growth and quality of purslane (Portulaca oleracea). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 86, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Li, C.; Ma, F.; Feng, F.; Shu, H. Responses of growth and antioxidant system to root-zone hypoxia stress in two Malus species. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rock Wool | Hemp | Rock Wool | Hemp | Optimum * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unused | used | ||||

| TPV [vol%] | 90.4 ± 2.6 aB | 75.9 ± 2.9 bB | 95.6 ± 1.6 aA | 83.1 ± 2.8 bA | >85 |

| AV [vol%] | 18.9 ± 5.1 aA | 13.9 ± 3.3 aA | 17.7 ± 6.3 aA | 10.0 ± 2.9 aA | 20 to 30 |

| EAW [vol%] | 70.3 ± 5.2 aA | 41.4 ± 2.0 bA | 63.2 ± 4.1 aA | 12.5 ± 1.6 bB | 20 to 30 |

| BD [g cm−3] | 0.1 ± 0.01 bB | 0.1 ± 0.0 aB | 0.1 ± 0.02 bA | 0.2 ± 0.03 aA | <0.4 |

| Sample | ΔNO3-N20d | ΔNH4-N20d | ΔN20d | Evaluation of N Budget * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mg L−1] | ||||

| hemp | 183 | 418 | 601 | not stable |

| Rock Wool | Hemp | |

|---|---|---|

| [g-N (N2O) ha−1 d−1] | ||

| 15 October 2020 | 0.17 ± 0.07 a | 5.03 ± 4.79 a |

| 9 November 2020 | n.d. b | 31.02 ± 21.93 a |

| 1 December 2020 | 0.04 ± 0.05 b | 21.97 ± 10.76 a |

| [kg-CO2 ha−1 d−1] | ||

| 15 October 2020 | 0.75 ± 0.12 b | 32.38 ± 1.36 a |

| 9 November 2020 | 0.10 ± 0.44 b | 16.23 ± 3.85 a |

| 1 December 2020 | 0.29 ± 0.45 b | 17.60 ± 4.01 a |

| [g-CH4 ha−1 d−1] | ||

| 15 October 2020 | n.d. b | 8.11 ± 2.91 a |

| 9 November 2020 | n.d. b | 6.41 ± 4.83 a |

| 1 December 2020 | n.d. b | 24.49 ± 17.68 a |

| Rock Wool | Hemp | |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf area per plant [m2] 6 weeks after planting | 2.97 ± 0.19 a | 2.82 ± 0.22 a |

| Plant length [m] | 9.51 ± 0.43 a | 8.96 ± 0.38 a |

| Total yield per plant [kg] | 9.98 ± 0.72 a | 9.27 ± 0.16 a |

| SSC fruit [ g 100 g−1 FM] CW 25 | 6.60 ± 0.08 a | 7.07 ± 0.18 a |

| SSC fruit [ g 100 g−1 FM] CW 32 | 5.36 ± 0.04 a | 5.40 ± 0.24 a |

| DM fruit [%] CW 25 | 7.73 ± 0.34 a | 9.12 ± 0.56 a |

| DM fruit [%] CW 32 | 5.64 ± 0.26 a | 5.54 ± 0.16 a |

| Nutrients in Tomato Leaves | Nutrients in Tomato Fruits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock Wool | Hemp | Rock Wool | Hemp | |

| N [g kg−1] | 50.2 ± 6.0 a | 50.2 ± 6.1 a | 17.2 ± 2.6 a | 17.0 ± 2.8 a |

| P [g kg−1] | 4.4 ± 0.6 a | 4.0 ± 0.3 a | 4.0 ± 0.3 a | 3.9 ± 0.4 a |

| K [g kg−1] | 49.2 ± 10.8 a | 50.2 ± 9.7 a | 44.6 ± 3.6 a | 43.4 ± 3.8 a |

| Ca [g kg−1] | 19.2 ± 5.9 a | 17.2 ± 4.4 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | 0.7 ± 0.2 a |

| Mg [g kg−1] | 8.2 ± 1.2 a | 9.4 ± 1.6 a | 1.6 ± 0.3 a | 1.6 ± 0.3 a |

| Cu [mg kg−1] | 16.7 ± 1.5 a | 14.6 ± 1.8 a | 9.3 ± 3.8 a | 9.8 ± 4.0 a |

| Zn [mg kg−1] | 37.9 ± 7.2 a | 36.9 ± 9.0 a | 25.1 ± 4.6 a | 22.8 ± 4.8 a |

| Fe [mg kg−1] | 174.7 ± 10.5 a | 171.3 ± 35.8 a | 41.4 ± 15.3 a | 39.6 ± 16.3 a |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nerlich, A.; Karlowsky, S.; Schwarz, D.; Förster, N.; Dannehl, D. Soilless Tomato Production: Effects of Hemp Fiber and Rock Wool Growing Media on Yield, Secondary Metabolites, Substrate Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8030272

Nerlich A, Karlowsky S, Schwarz D, Förster N, Dannehl D. Soilless Tomato Production: Effects of Hemp Fiber and Rock Wool Growing Media on Yield, Secondary Metabolites, Substrate Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Horticulturae. 2022; 8(3):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8030272

Chicago/Turabian StyleNerlich, Annika, Stefan Karlowsky, Dietmar Schwarz, Nadja Förster, and Dennis Dannehl. 2022. "Soilless Tomato Production: Effects of Hemp Fiber and Rock Wool Growing Media on Yield, Secondary Metabolites, Substrate Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions" Horticulturae 8, no. 3: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8030272

APA StyleNerlich, A., Karlowsky, S., Schwarz, D., Förster, N., & Dannehl, D. (2022). Soilless Tomato Production: Effects of Hemp Fiber and Rock Wool Growing Media on Yield, Secondary Metabolites, Substrate Characteristics and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Horticulturae, 8(3), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8030272