Evaluation of Native Bacterial Isolates for Control of Cucumber Powdery Mildew under Greenhouse Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cucumber Powdery Mildew Pathogen Identification

2.2. Plant Materials

2.3. Fungal Inoculum and Inoculation

2.4. Isolation of Native Bacterial Bioagents

2.5. Screening of Certain Bioagents against Conidiospore Germination

2.6. Identification of Unknown Bioagents Isolates Using Polymerase Chain Reaction Nucleotide Sequence (PCR-Seq)

2.7. Efficacy of Tested Bioagent Culture Filtrates or Cell Suspension on Spore Germination of Podosphaera xanthii

2.8. Antagonistic Test against P. xanthii In Vivo

2.9. Biochemical Assays

2.10. Sample Collection

2.10.1. Determination of Peroxidase

2.10.2. Determination of Polyphenol Oxidase

2.10.3. Determination of Total Phenol Content

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screening of Bioagents against Conidiospore Germination

3.2. Identification of Unknown Bacterial Antagonist

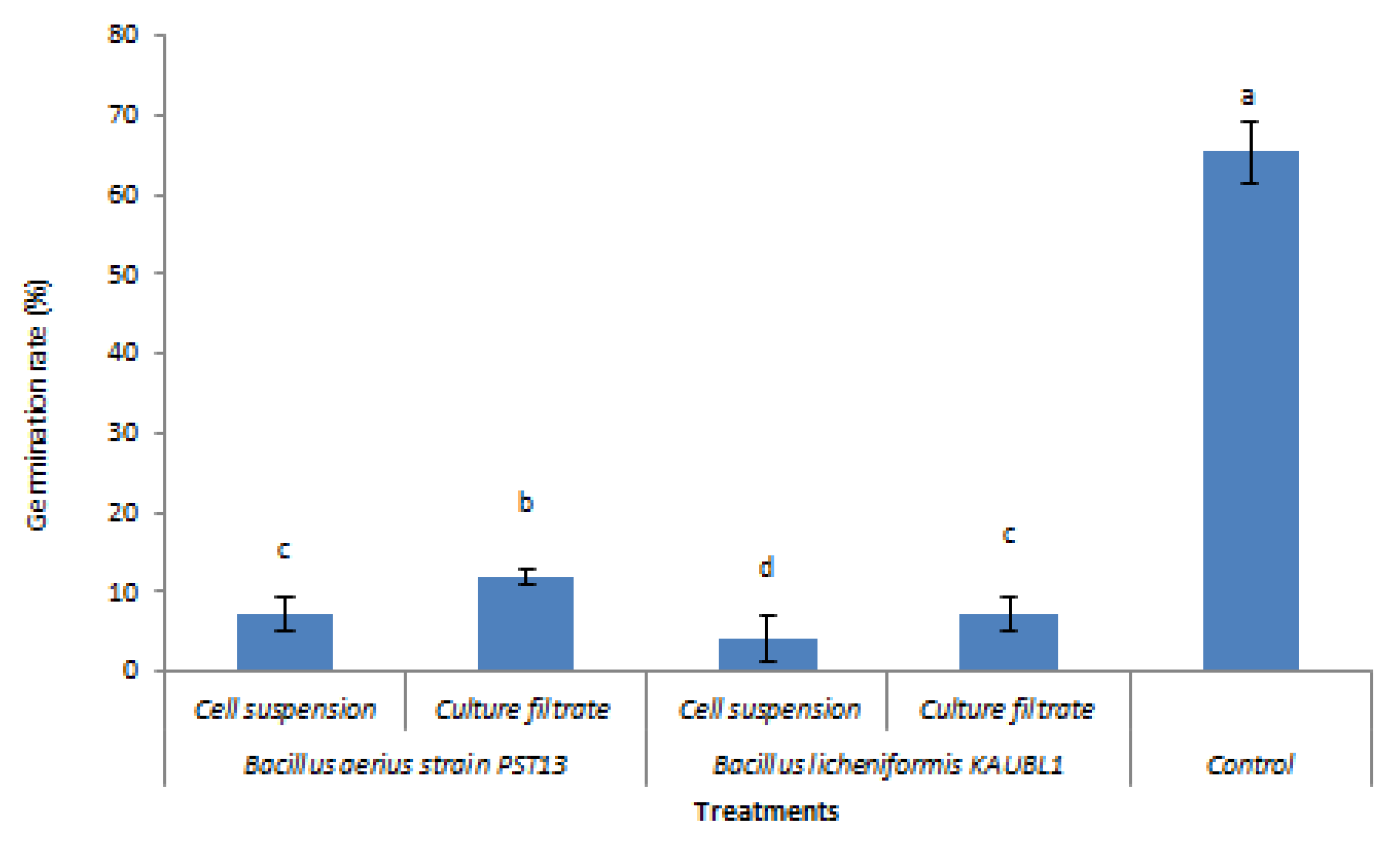

3.3. Effect of Bacillus licheniformis and B. aerius as Culture Filtrate or Cell Suspension on Conidiospore Germination

3.4. Enzymatic Activity of Effective Bacterial Bioagents

3.5. Effect of Bioagents on Disease Severity of Powdery Mildew

3.6. Effect of Bioagents on Vegetative Growth

3.7. Effect of Some Bioagents on Biochemical Changes in Cucumber Plants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mostafa, Y.S.; Hashem, M.; Alshehri, A.M.; Alamri, S.; Eid, E.M.; Ziedan, E.-S.H.; Alrumman, S.A. Effective management of cucumber powdery mildew with essential oils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, Y.A.A.; Magdi, A.A.M.; Hassan, S.A. Greenhouse-grown cucumber as an alternative to field production and its economic feasibility in Aswan governorate, Egypt. Assiut J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 47, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gamal, N.G. Usage of some biotic and abiotic agents for induction of resistance to cucumber powdery mildew under plastic house conditions. Egypt. J. Phytopathol. 2003, 31, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rur, M.; Rämert, B.; Hökeberg, M.; Ramesh, R.V.; Laura, G.B.; Erland, L. Screening of alternative products for integrated pest management of cucurbit powdery mildew in Sweden. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 150, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, M.; El-Deeb, H.; Ragab, S. Applied approach for controlling powdery mildew disease of cucumber under plastic houses. Pak. J. Agric. Agric. Eng. Vet. Sci. 2012, 28, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkara, A.; Akyıl, D.; Konuk, M. Pesticides, environmental pollution, and health. In Environmental Health Risk Hazardous Factors to Living Species; Larramendy, M.L., Soloneski, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Madbouly, A.K.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Ismail, M.I. Biocontrol of Monilinia fructigena the causal agent of brown rot of stored apple fruits using certain endophytic yeasts. Biol. Cont. 2020, 144, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Q.; Xiukang, W.; Haider, F.U.; Kučerik, J.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Holatko, J.; Naseem, M.; Kintl, A.; Ejaz, M.; Naveed, M.; et al. Rhizosphere bacteria in plant growth promotion, biocontrol, and bioremediation of contaminated sites: A Comprehensive review of effects and mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frem, M.; Nigro, F.; Medawar, S.; Moujabber, M.E. Biological approaches promise innovative and sustainable management of powdery mildew in Lebanese ssquash. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Kader, M.M.; El-Mougy, N.S.; Aly, M.D.; Lashin, S.M.; Abdel-Kareem, F. Greenhouse biological approach for controlling foliar diseases of some vegetables. Adv. Life Sci. 2012, 2, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghanam, A.; Rahhal, M.; Al-Saman, M.; Khattab, E. Alternative safety methods for controlling powdery mildew in squash under field conditions. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2018, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.A. Biological control of plant diseases. Austr. Plant Pathol. 2017, 46, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasannath, K. Plant defense-related enzymes against pathogens: A review. AGRIEAST J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 11, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsisi, A.A. Evaluation of biological control agents for managing squash powdery mildew under greenhouse conditions. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2019, 29, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Gaur, R. Evaluation of antagonistic and plant growth promoting activities of chitinolytic endophytic actinomycetes associated with medicinal plants against Sclerotium rolfsii in chickpea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.; Peres, N.A. Evaluation of biofungicides for control of powdery mildew of gerbera daisy. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 2008, 121, 389–394. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, U.; Takamatsu, S. Phylogeny of Erysiphe, Microsphaera, Uncinula (Erysipheae) and Cystotheca, Podosphaera, Sphaerotheca (Cystotheceae) inferred from rDNA ITS sequences–Some taxonomic consequences. Schlechtendalia 2000, 4, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Reuveni, R.; Dor, G.; Raviv, M.; Reuveni, M.; Tuzun, S. Systemic resistance against Sphaerotheca fuliginea in cucumber plants exposed to phosphate in hydroponics system and its control by foliar spray of mono-potassium phosphate. Crop Protect. 2000, 19, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Mousa, M.A.; Saad, M.M. Screening and biocontrol evaluation of indigenous native Trichoderma spp. against early blight disease and their field assessment to alleviate natural infection. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Morsi, A.M.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Abdel-Monaim, M.F. Management of cucumber powdery mildew by certain biological control agents (BCAs) and resistance inducing chemicals (RICs). Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Protect. 2012, 45, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.R.S.; Ellingboe, A.H. A method of controlled inoculations with conidio spores of Erysiphe graminis var. tritici. Phytopathology 1962, 52, 417. [Google Scholar]

- Reifschneider, F.J.B.; Boitexu, L.S.; Occhiena, E.M. Powdery mildew of melon (Cucumis melo) caused by Sphaerotheca fuliginea in Brazil. Plant Dis. 1985, 69, 1069–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies, J.G.; Ehret, D.L.; Glass, A.D.M.; Helmer, T.; Koch, C.; Seywerd, F. Effects of soluble silicon on the parasitic fitness of Sphaerotheca fuliginea on Cucumis sativus. Phytopathology 1991, 81, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidhyasekaran, P.; Muthamilan, M. Development of formulations of Pseudomonas fluorescens for control of chickpea wilt. Plant Dis. 1995, 79, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Saito, T.; Sakata, Y. Review: Powdery mildew resistance in cucumber. JARQ 2003, 37, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollage, M.D.; Rozycki, D.M.; Edelstein, J.S. Protein Methods; Wiley-Liss, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996; 413p. [Google Scholar]

- Biles, C.L.; Martyn, R.D. Peroxidase, polyphenoloxidase, and shikimate dehydrogenase isozymes in relation to tissue type, maturity and pathogen induction of watermelon seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1993, 31, 499–506. [Google Scholar]

- Allam, A.I.; Hollis, J.P. Sulfide inhibition of oxidase in rice roots. Phytopathology 1972, 62, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaaya, I. In the armored scale Aonidiella aurantii and observation on the phenoloxidase system Chrysomphalus aonidum. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1971, 39, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieslin, N.; Ben-Zaken, R. Peroxidase activity and presence of phenolic substances in peduncles of rose flowers. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1993, 31, 333. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, K.A.; Gomez, A.A. Statistical procedures for agricultural research. In Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1984; p. 187. 680p. [Google Scholar]

- Sarhan, E.A.D.; Abd-Elsyed, M.H.F.; Ebrahiem, A.M.Y. Biological control of cucumber powdery mildew (Podosphaera xanthii) (Castagne) under greenhouse conditions. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Cont. 2020, 30, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dov, P.; Llana, K. Regulation of natural resistance of avocado fruit for the control of post-harvest disease. In Proceedings of the Second World Avocado Congress, Orange, CA, USA, 21–26 April 1992; pp. 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, D.; de Vincente, A.; Zeriouh, H.; Cazorla, F.M.; Fernandez-Ortuno, D.; Tores, J.A.; Perez-Garcia, A. Evaluation of biological control agents for managing cucurbit powdery mildew on greenhouse-grown melon. Plant Pathol. 2007, 56, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punja, Z.K.; Tirajoh, A.; Collyer, D.; Ni, L. Efficacy of Bacillus subtilis strain QST 713 (Rhapsody) against four major diseases of greenhouse cucumbers. Crop Prot. 2019, 124, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.M.; Sagar, B.V.; Devi, G.U.; Triveni, S.; Rao, S.R.K.; Chari, D.K. Isolation and screening of bacterial and fungal isolates for plant growth promoting properties from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2017, 6, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, E.A.D.; Shehata, H.S. Potential plant growth-promoting activity of Pseudomonas spp. and Bacillus spp. as biocontrol agents against damping-off in Alfalfa. Plant Pathol. J. 2014, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, R.R.; Labbé, C. Control of powdery mildews without chemicals: Prophylactic and biological alternatives for horticultural crops. In The Powdery Mildews: A Comprehensive Treatise; Bélanger, R.R., Bushnell, W.R., Dik, A.J., Carver, T.L.W., Eds.; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2002; pp. 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, J.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Li, M.S.; Jin, B.R.; Je, Y.H. Bacillus thuringiensisas a specific, safe, and effective tool for insect pest control. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 17, 547–559. [Google Scholar]

- Emily, R.; Margaret, T.M.; Jacqueline, J. Biological control of powdery mildew on Cornusflorida using endophytic Bacillus thuringiensis. Canad. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 42, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkaway, M.M.; Kamel, S.M.; El-Khateeb, N.M. Biological control of powdery and downy mildews of cucumber under greenhouse conditions. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2014, 24, 407. [Google Scholar]

- Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Balabel, N.M. Induction of disease defensive enzymes in response to treatment with acibenzolar-S-methyl (ASM) and Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf2 and inoculated with Ralstonia solanacearum race 3, biovar2 (phylotype II). J. Phytopathol. 2012, 160, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N.I.; Br Ooks, S.; Lumyong, S.; Hyde, K.D. Use of endophytes as biocontrol agents. Fungal Biol. Rev. J. 2019, 33, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, Y.L.; Lou, Y.; Shi, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Y.; Xue, Q.; Lai, H. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Ba13 induces plant systemic resistance and improves rhizosphere microecology against tomato yellow leaf curl virus disease. Appl. Soil Ecol. J. 2019, 137, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongena, M.; Jacques, P. Bacillus lipopeptides: Versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. J. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.S.; Lee, K.D. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria effect on antioxidant status, photosynthesis, mineral uptake and growth of lettuce under soil salinity. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2005, 1, 210–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q.; Zhao, D.L.; Shen, L.L.; Jing, C.L.; Zhang, C.S. Application and mechanisms of Bacillus subtilis in biological control of plant disease. In Role of Rhizospheric Microbes in Soil; Meena, V.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.E.; Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M. Activation of tomato plant defence responses against bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum using DL-3-aminobutyric acid (BABA). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 136, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, R.; Shahzad, M.; Pengfei, H.; Huanwen, Y.; Yixin, W.; Junwei, W.; Pengbo, H.; Yongzhan, C.; Ge, W.; Yueqiu, H. Biocontrol potential of the endophytic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens YN201732 against tobacco powdery mildew and its growth promotion. Biol. Cont. 2020, 143, 104160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdarpour, F.; Khodakaramain, G. Endophytic bacteria suppress bacterial wilt of tomato caused by Ralstonia solanacearum and activate defense-related metabolites. Biol. J. Microorg. 2018, 6, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili, N.; Ebrahimzadeh, H.; Abdi, K. Correlation between polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity and total phenolic contents in Crocus sativus L. corms during dormancy and sprouting stages. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2017, 14, S519–S524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, F.; Pasqualone, A.; Mangini, G.; Tripodi, P.; Miazzi, M.M.; Pavan, S.; Montemurro, C. Polyphenol oxidases in crops: Biochemical, physiological and genetic aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Isolate | Reduction of Conidiospore (%) |

|---|---|

| PTS1 | 15 d |

| PTS2 | 30 c |

| PTS3 | 0 e |

| PTS4 | 35 c |

| PTS5 | 0 e |

| PPR6 | 0 e |

| PPR7 | 10 e |

| PPR8 | 0 e |

| PPR9 | 0 e |

| PPR10 | 0 e |

| PTS11 | 0 e |

| PTS12 | 0 e |

| PST13 | 85 b |

| KAUBL1 | 90 a |

| KAUBL2 | 0 e |

| KAUBL3 | 20 d |

| KAUBL4 | 0 e |

| KAUBL5 | 0 e |

| KAUBL6 | 0 e |

| Control | - |

| Bioagent Isolate | Maximum Score | Total Score | Query Cover | E Value | Percent Identity | Most Similar Organism | GenBank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAUBL1 | 1732 | 1732 | 100% | 0.0 | 100% | Bacillus licheniformis | KT758463.1 |

| PST13 | 1135 | 1143 | 99% | 0.0 | 99% | Bacillus aerius | NR_118439.1 |

| Bacterial Bioagents | Zone of Hydrolysis (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | Cellulase | Pectinase | Protease | |

| B. licheniformis KAUBL1 | 15 a | 63 b | 37 a | 16 a |

| Bacillus aerius PST13 | 10 b | 75 a | 20 b | 9 b |

| Treatments | Method of Application | 2 Days before Infection | 2 Days after Infection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Severity (%) | Reduction (%) | Disease Severity (%) | Reduction (%) | ||

| B. licheniformis | Cell suspension (CS) | 30.1 c | 45.3 | 39.4 c | 39.7 |

| Culture filtrate (CF) | 35.5 b | 35.6 | 40.2 b | 38.4 | |

| B. aerius | Cell suspension (CS) | 12.5 b | 77.3 | 19.7 b | 69.8 |

| Culture filtrate (CF) | 29.1 c | 47.2 | 39.2 c | 39.9 | |

| Control | 55.1 a | - | 65.3 a | ||

| Treatments | Method of Application | 2 Days before Infection | 2 Days after Infection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Fresh Weight FW (g/plant) | Plant Dray Weight DW(g/plant) | No. Leaves Plant−1 | Plant Fresh Weight FW (g/plant) | Plant Dray Weight DW (g/plant) | No. Leaves Plant−1 | ||

| B. licheniformis | Cell suspension (CS) | 287.9 a | 27.7 a | 25 a | 255.3 a | 29.3 a | 23 a |

| Culture filtrate (CF) | 198.5 b | 12.3 e | 14 d | 185.5 b | 10.3 e | 12 e | |

| B. aerius | Cell suspension (CS) | 165.3 b | 21.1 c | 18 c | 165.9 b | 20.1 c | 18 c |

| Culture filtrate (CF) | 250.3 a | 25.1 b | 21 b | 256.1 a | 29.2 b | 23 a | |

| Infected Control | 150.2 bc | 19.2 d | 12 e | 155.3 bc | 19.2 d | 15 d | |

| Treatments | Method of Application | Peroxidase (Enzyme Unit/mg Protein/min) | Polyphenol Oxidase (Enzyme Unit/mg Protein/min) | Total Phenols (μg GAE/g Fresh Weight) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Days before Inoculation | 2 Days after Inoculation | 2 Days before Inoculation | 2 Days after Inoculation | 2 Days before Inoculation | 2 Days after Inoculation | ||

| B. licheniformis | (CS) | 180.3 a | 121.2 a | 125.3 a | 113.8 a | 51.6 a | 45.3 a |

| (CF) | 98.3 d | 81.2 d | 101.5 d | 80.7 c | 35.6 b | 35.2 c | |

| B. aerius | (CS) | 134.2 c | 100.2 c | 119.3 b | 102.1.3 b | 44.6 b | 40.3 b |

| (CF) | 122.1 b | 108.1 b | 111.2 c | 101.8 b | 43.2 b | 39.6 b | |

| Infected Control | 51.7 e | 41.2 e | 85.2 e | 45.8 d | 30.7 c | 29.3 d | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abo-Elyousr, K.A.M.; Seleim, M.A.-S.A.A.-H.; Almasoudi, N.M.; Bagy, H.M.M.K. Evaluation of Native Bacterial Isolates for Control of Cucumber Powdery Mildew under Greenhouse Conditions. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121143

Abo-Elyousr KAM, Seleim MA-SAA-H, Almasoudi NM, Bagy HMMK. Evaluation of Native Bacterial Isolates for Control of Cucumber Powdery Mildew under Greenhouse Conditions. Horticulturae. 2022; 8(12):1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121143

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbo-Elyousr, Kamal Ahmed M., Mohamed Al-Sadek Abd Al-Haleim Seleim, Najeeb Marei Almasoudi, and Hadeel Magdy Mohammed Khalil Bagy. 2022. "Evaluation of Native Bacterial Isolates for Control of Cucumber Powdery Mildew under Greenhouse Conditions" Horticulturae 8, no. 12: 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121143

APA StyleAbo-Elyousr, K. A. M., Seleim, M. A.-S. A. A.-H., Almasoudi, N. M., & Bagy, H. M. M. K. (2022). Evaluation of Native Bacterial Isolates for Control of Cucumber Powdery Mildew under Greenhouse Conditions. Horticulturae, 8(12), 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae8121143