Abstract

Within Asia, imported fruits and vegetables are often considered as a delicacy and of high value, and are increasingly demanded compared to local products. There are numerous significant factors involved with consumers’ characteristics and their corresponding values towards these products. This study investigates potential consumers and their preferences towards imported fruits and vegetables in three Asian countries: Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia. A total of 1350 survey responses collected from Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia are examined by a best–worst scaling method with a latent class multinomial logit model. Results show that consumers tend to choose imported fruits that are not commonly provided by domestic producers. While a food safety certified label and freshness are consistently identified as the most and second most important food values for Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian consumers, price is still an important factor for certain consumer groups. The majority of Taiwanese and Japanese consumers (i.e., female, higher education, and from an urban area) prefer imported fruits and vegetables, while the majority of Indonesian consumers do not pay much attention to imported fruits and vegetables. While Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia are island countries, the novelty of this study shows that consumer preferences do not behave the same. The implications of this study should be of interest to producers and exporters who wish to positively impact the design of their international marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

Consumers are commonly concerned about product attributes when making choices to purchase food ingredients [1]. In particular, the varieties of imported fruits and vegetables affect consumer preferences when they purchase imported fruits and vegetables [2]. However, consumers are not only interested in the varieties, but also pay attention to the food safety of these imported agricultural products [3]. In addition, consumers’ individual differences and interests can influence their preferences concerning imported products [4]. Lusk and Briggeman (2009) [5] explored U.S. consumer preferences towards eleven food values—taste, naturalness, food safety, price, nutrition, convenience, product country of origin, tradition, appearance, fairness, and environmental impact. They found that, in general, food safety was the most significant food value followed by nutrition, taste, and price. While other food values such as tradition, product country of origin, fairness, and environmental impact were the least important food values among consumers in their study.

While these above-mentioned food values can be crucially important, in the following studies, price could still be ranked the second most important food value [6]. However, environmental impact, naturalness, appearance, and origin remained the least important food values [6]. Furthermore, consumers from different countries often use varying criteria to evaluate and buy goods based upon different attributes of product and upon their individual culture [7]. For example, Gracia and de-Magistris (2016) [3] found that consumers in Spain chose food labels regulated by EU law as the most important food values when they purchased food. Other cross-country studies have been done in order to obtain more understanding in the similarities and differences concerning consumers’ behaviors towards food purchasing [8,9,10,11]. Bazzani and Gustavsen (2016) [10] conducted research aimed at measuring and comparing U.S. and Norwegian consumers’ preferences by proposing the environmental impact, naturalness, animal welfare, taste, appearance, price, fairness, novelty, safety, convenience, nutrition, and product country of origin as the food values evaluated in the study. Their findings revealed that, compared to product origin, the food values of food safety, taste, and nutrition were typically chosen as the most important for U.S. consumers, while Norwegian consumers viewed food safety, taste, and naturalness as the most important food values [10]. As mentioned above, we can see that consumers do not treat food values in the same way. Food value preferences can clarify personal food choices for various food products [12]. Therefore, it is crucially important for food marketers to understand which aspect of food value (e.g., sensory properties, image, product origin, health concern, or price) is important to consumers [13]. In particular, international marketers may be devastated by consumers of importing countries if the products do not meet what they deem to be the most important food values. Thus, it is very important to identify consumer preferences concerning food values, so that food marketing strategies and policies can be more effective [14].

A further discussion about what types of imported foods are preferred and the characteristics of consumers willing to purchase imported food products would help marketers to target specific consumer groups. In particular, the multi-country comparison of consumer preference for imported foods is limited. Japan and Taiwan have two of the fastest growing economies in Asia [15]. Meanwhile, Indonesia is the country with the highest growth in imported agricultural products in Southeast Asia [16]. While Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia are island countries, the novelty of this study is to find out whether consumer preferences in these countries behave the same or not. As we would expect, the more understanding of consumer preferences in any country, the more success in developing marketing strategies for international trade [12,17]. Thus, the first objective is to identify what types of imported fruit products are preferred in these three countries. A second objective is to evaluate the importance of food values and to identify how socio-demographic factors might influence consumer preferences of imported fruits and vegetables in these three countries.

2. Literature Reviews

2.1. Imported Fruits and Vegetables in Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia

According to Nelson and Kashiwagi (2016) [18], the number one country from which Japan imported processed vegetables in 2014 (including fresh and frozen) was China, which occupied by value and volume with 57.1% and 51.4% market share, respectively. Further, the report points out that few countries dominate imported fresh fruits and vegetables in the Japanese market. From the report we can see that the main imported fruits in Japan in 2017 were bananas, kiwis, avocados, and pineapples with the shares 39.8%, 14.7%, 9.6%, and 5.9%, respectively. USDA (2018) [19] reported that fresh fruits imported to the Japanese market ranged from 1.55 to 1.65 million kilotons during 2012 to 2017. The volume of imported fresh fruits to the Japanese market was 1.62 million kilotons in 2017, valued at US$2.14 billion. In addition, it was also reported that the main exporters of imported fresh fruit to the Japanese market are the Philippines (37.7%), the United States (16.8%), New Zealand (14.4%), and Mexico (12.6%), by kiloton.

Regarding the imported fruit market in Taiwan, the imported fruits in 2017 amounted to 635,501 kiloton by volume and US$742 million by value. The biggest exporter of imported fruits to Taiwan was the United States, with about 35% market share, followed by New Zealand (23%), Chile (17%), Japan (11%), and South Korea (3%). Furthermore, the main imported fruits to Taiwan were apples, grapes, oranges, pineapples, jujubes, and peaches with 29%, 10%, 6%, 5%, 5%, and 3% market share in 2017, respectively [20]. The report also reports that Taiwan in 2017 imported vegetables amounting to about 551,730 kiloton by volume, which decreased by around 14% from 2016 [20]. The leading supplier was the United States and its exported fresh vegetables were potatoes, onions, broccoli, and lettuce [21].

Indonesian horticulture products have been significantly impacted by global free trade, resulting in the amount of imported fruits expanding fast over the previous 10 years [22]. According to the Indonesian Ministry of Trade, horticulture imports reached $600 million USD in 2006 and rose to $1.7 billion USD in 2011 [23]. Fresh fruit accounts for around 45 percent of such imports, namely apples ($153 million USD), oranges ($150 million USD), grapes ($99 million USD), and durians ($74 million USD). In terms of fruit imports, China supplies 55% of Indonesia’s needs, followed by Thailand with 28%, the United States with 10%, Chile with 4%, and Australia with 3% [23]. In 2011, imports of fresh vegetables climbed by 29%, with white onions ($242 million USD) and red onions ($74 million USD) accounting for the majority [23]. Moreover, China is also the major supplier of veggies in Indonesia, accounting for 67% of total imports, followed by Thailand and Myanmar at 10% each and India at 8%.

The Indonesian Central Bureau Statistics reported that the total volume of imported fruit in 2015 was 435,000 kilotons and increased by 10.46% in 2016 and 52.6% in 2017. In addition, it reported that the volume of imported vegetables in 2015 was about 0.73 million kilotons, and increased by 5% in 2016 to 23% in 2017. According to the Indonesian Central Statistics Agency, the total value of Indonesian vegetable imports hit US$67.91 million in 2017 with a volume of 83,637 tons [24]. Furthermore, China ranked first as a vegetable importer in Indonesia with a total import value of US$654.70 million, followed by Myanmar (US$40.94 million), India (US$32.96 million), New Zealand (US$23.62 million), Ethiopia (US$19.69 million), and other countries with a total import value of US$63.83 million [24]. Yet, according to the data from the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Indonesia in 2017, the major fruits imported to Indonesia were pears (32%), apples (29%), oranges (23%), and grapes (16%). China was the main exporting country of fruits and vegetables to Indonesia in 2017 with 51% and 62% market share by volume, respectively.

While the abovementioned records already imply the types of fresh fruit items that are the most preferred in each country, how consumers in each country pick their preferred imported fruit items should be further explored. In particular, Feng et al. (2021) [25] indicated that focusing on an appropriate strategy (i.e., clean green image) would effectively boost the willingness to buy for the imported fresh food from China. This implies that the potential hypothesis can be related to the factors that may influence the purchase. Therefore, the expected result in this study was further to understand the most important food values amongst Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian customers concerning imported fruit and vegetable purchasing. Moreover, we can investigate and understand how the socio-demographic characteristics might affect consumer preferences in these three countries.

2.2. Food Values

According to Bardi and Schwartz (2003) [26], value indicates what is important in our lives. Values specifically are “enduring beliefs that a specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state” [27]. Since values can affect consumers’ purchasing behaviors; they are often viewed seriously by marketers [28]. In addition, understanding values is key to developing effective marketing strategies and public policies [29]. By understanding a person’s values, we might understand what motivates an individual to make certain decisions [30]. Besides, every person has a different set of values; hence any specific value can be an important factor to one individual, but it may be not an important factor to another [26]. Dagevos and van Ophem (2013) [31] stated that product value is the characteristic of food products comprised of sensory properties (color, freshness, taste, flavor, and texture) and nutritional values (such as vitamin, mineral, and protein). Eleven food values [12,32], comprised of the environmental impact, naturalness, animal welfare, taste, appearance, price, fairness, novelty, safety, convenience, nutrition, and product origin, can help explain consumer behavior towards food. Dagevos and van Ophem (2013) [31] pointed out that the food values from Lusk’s research could be separated into two aspects, one involved with the product itself such as nutrition, taste, price, safety, appearance, and convenience and another one linked to the processing value such as product origin, tradition, fairness, naturalness, and environmental impact.

This study built upon the research of Lusk and Briggeman (2009) [5] and Bazzani and Gustavsen (2016) [10] in terms of the attributes of the food values. After pilot discussion meetings with the trading agents, a list of seven food values for this study were selected and the descriptions are explained as following:

- Product origin label refers to a label showing the origin of imported fruits or vegetables.

- Food safety certified refers to the safety certification of imported fruits or vegetables and confirms that the products were safe.

- High quality appearance indicates the imported fruits or vegetables have good appearance.

- Domestic rarity refers to the unavailability of the imported fruits and vegetables, which are not easy to find or not common in the country.

- Price refers to the amount of money that was spent to buy the imported fruits or vegetables.

- Plantations indicates how the imported fruit or vegetable products were grown.

- Freshness refers to the condition of the imported fruits and vegetables that were still fresh when consumers purchased them. Due to the long distance or long-distance distribution, freshness is challenging for the trading agents. The level of freshness is considered as a significant factor among consumers when purchasing the products. These seven food values are considered as the potential hypotheses to be examined.

Four food values including origin, food safety, appearance, and price were similar to the previous study, while the others including domestic rarity, plantations, and freshness were newly introduced in this study. Some food values such as convenience, tradition, fairness, naturalness, taste, nutrition, and animal welfare were not utilized in this research since these food values might only have a little relevance to the imported fruits and vegetables in various countries. In addition, the selected food values in this research ought to be easily recognizable and comparable by all respondents.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

Data were collected through online survey from 2016 to 2018 in these three countries. This study applied the services of the SurveyMonkey website, which is an online survey platform to collect the data. Due to the limitation of the research budget, it was not able to collect all the data at the same year. While the GDP growth of these three countries is relatively stable during 2016 to 2018 [33,34,35], the comparison of the three countries is still acceptable. The data from Taiwanese consumers were collected in August 2017, data were collected in Japan in August 2016, and data from Indonesian participants were collected in August 2018. First, the questionnaire was created in English (shown in Supplementary Material 1); then it was translated into Chinese for Taiwanese respondents, Japanese for Japanese respondents, and Bahasa Indonesian for Indonesian respondents. At the beginning of the questionnaire, a screening question was adopted to screen out those respondents who are not relevant to our study. If the respondents were responsible for purchasing fruits and vegetables for their family, they would be qualified to fill out the survey. Thus, respondents who chose “No, not at all” would be screened out, while respondents who either selected “Yes, but sometimes only” or “Yes, all the time” would be able to fill out the next question of the survey. In all, there were 1350 valid respondents in this study, including 333 Taiwanese, 500 Japanese, and 517 Indonesian respondents.

3.2. Best–Worst Scaling Method

The Best–Worst Scaling (BWS) method refers to an extension of the paired comparison method, where the respondents are asked to select the best option (more important) and the worst option (the least important) from a set of alternatives [5,10,36,37,38]. As noted by Finn and Louviere (1992) [39], “Best-Worst Scaling models the cognitive process by which respondents repeatedly choose the two objects in varying sets of three or more objects that they feel exhibit the largest perceptual difference on an underlying continuum of interest”. The BWS method has been utilized to examine the preferences of consumers in various products in previous studies, such as the preferences of consumers towards wine [40,41,42], the preferences of consumers towards beef [43], the preferences of consumers towards pork [44], the preferences of consumers towards fruit juice [45], cross-country study on ethical beliefs of consumers [7], the perceptions of consumers towards food safety [46], brand equity [46], consumers’ preferences towards rice [47], and the preferences of European consumers towards food labelling [3,48].

In addition, the BWS method could successfully solve numerous issues in the rating scale usage between different countries [7]. According to the preferences and experiences of consumers in buying imported fresh fruit and vegetable products, respondents were able to follow the BWS evaluation method to choose “most” and “least” important food values. This study used a balanced incomplete block design (BIBD) approach, which is a type of experimental design, and means that every attribute level (factor) equally replicates and has equal probabilities of selecting factors [7]. Each option repeated four times in all sets of questions and each pair of items appeared in the same question twice [49]. Therefore, each respondent was required to answer seven best–worst question sets. Each question set had four food values, and each food value randomly shows up four times across the seven best–worst question sets. If the respondent neglected to select one option for the most or the least important values, there would be a notice to notify them before they could continue onto the next question.

3.3. Latent Class Multinomial Logit Model

To elicit the heterogeneity of consumers, this research employed a Latent Class Multinomial Logit (LC-MNL) model. The R program was adopted to estimate the latent class model in accordance with the best–worst scores of each respondent. As the first step, we compared the mean of food values between Japanese and Taiwanese, Japanese and Indonesian, and Taiwanese and Indonesian consumers by using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Bonferroni correction was utilized in order to define the multiple comparisons [50].

Referring to Aizaki et al. (2014) [49], it is assumed that m is the total number of options in a choice set in the BWS questions, i is the best option, and j is the worst option. The number of possible pairs in which options i and j were chosen is m × (m − 1). The v is presumed to be the utility for respondents to choose each option. The probability of choosing item i as the best and item j as the worst options is shown in Equation (1).

The probability of the class assignment (wiq) is unknown. A common parameterization of wiq is the semi-parametric Multinomial Logit format [51]:

where is assumed as the socio-economic characteristics variables, which are used to specify the assignment to classes. However, the first-class parameters are normalized to be zero to specify the model. It is noted that the participant could neglect the socio-economic covariate variable as a determinant of the class assignment probability [51].

Some statistical criteria are suggested to ensure the model fit, for example, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Log Likelihood [42,52]. Herein, the model with a better fit is defined as the value of the decrease of BIC (closer to zero) and the increase of Log Likelihood [42]. In our research, we found the possible number of the latent classes of two to nine classes. Finally, we selected the latent class model with three classes due to the biggest difference in the model fit occurred between two and three classes.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Information

The total number of valid respondents was 1350 (333 Taiwanese, 500 Japanese, and 517 Indonesian respondents). The demographic information for each country is shown in Table 1. Demographic information was collected regarding gender (female), age (40 years old or younger), occupation (full-time employee), education (high level of education (16 years or above)), living place (urban area), having children in household (has children at home), number of people in household (1–2 people), and income (high income). Table 1 shows the basic socio-economic characteristics of Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian respondents. Most respondents were female for each country (75.0% Taiwanese, 85.0% Japanese, and 97.0% Indonesian). This indicates that females in Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia tend to have primary responsibility for buying fruits and vegetables for their family.

Table 1.

Descriptive Analysis of Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian Respondents.

In order to easily explain the outcomes of the LC-MNL model with socio-demographic variables, the variables of age, education, and income were set as the dummy variables. The percentages of younger age (40 years old or younger) for each county were Taiwanese, 67.5%; Japanese, 20.0%; and Indonesian, 96.4%. Furthermore, this age distribution for each country is compared through the median age with the Central Intelligence Agency [53], and the outcomes for each country are very close to each other. This means that our samples could generally represent the national population in each country. In general, respondents tended to have obtained a Bachelor’s degree (16 years or above) and be well educated (Taiwanese respondents about 75.7% and Japanese respondents about 59.2%); however, the value for Indonesian respondents who have a university degree or above (16 years of education or above) was only 14.1%.

When compared to Taiwanese and Indonesian respondents, Japanese respondents were less likely to have children in their households. In other words, most respondents for Taiwanese and Japanese have no children in their household (52.5% Taiwanese and 70.0% Japanese). Table 1 displays the high-income level per month for each country. The high-income level for Taiwanese respondents is defined as NTD 75,001 or above, JPY 7,000,001 or above for Japanese respondents, and Rp 4,500,001 or above for Indonesian respondents. The high-income level for Taiwanese respondents is about 28.9%, for Japanese respondents 38.4%, and for Indonesian respondents 49.0%.

4.2. The Preference of Imported Fruit Products for These Three Countries

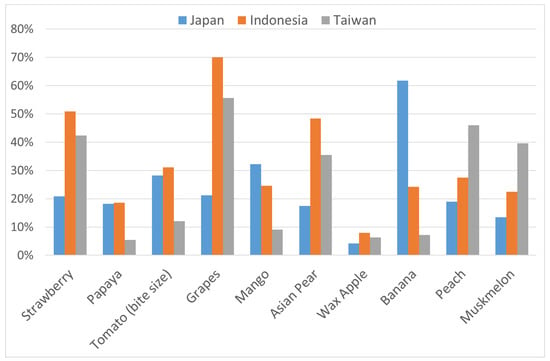

The respondents for these three countries were asked to choose the imported fruit items that they have most considered buying. Since the vegetable category varies by regions and eating behaviors, the vegetable category is not included in this comparison for simplicity. The comparison of imported fruit products in each country is exhibited in Figure 1. The percentages in Figure 1 reveal the percentage of respondents who choose any particular fruit as their preferred imported fruit product items. A higher percentage reveals a higher popularity in that country. This study found that the behavior of purchasing imported fruit products in these countries slightly differs.

Figure 1.

The Percentage of Consumer Frequently Preferred Choices on Imported Fruit Products for Each Country.

Imported strawberries, grapes, and Asian pears are particularly preferred by Indonesian and Taiwanese respondents. Note that these items are commonly grown in higher altitude or colder weather in each country. However, the terrain in Taiwan and Indonesia presents a lower scale of production, so these two countries rely on imports for these fruits. This also means that consumers may tend to buy the imported products which are not commonly domestically grown. Further, this point is supported by the Japanese consumer who prefers to buy bananas as their most preferred imported fruit product. Since banana production in Japan is limited, Japanese consumers would rely on banana imports. Moreover, Japanese consumers choose mangos as the second most preferred product to buy concerning imported fruit products. Mangos are similar to bananas as they both grow best in tropical areas. Therefore, we find that consumers in these countries tend to buy the imported fruit products that are not typically grown domestically.

4.3. Latent Class Multinomial Logit Model including Socio-Demographic Variables

The LC-MNL model is adopted to elicit the most important food values compared to price. This means that the price variable is treated as the baseline for the estimation of the LC-MNL model since price is commonly noticed to be negative by consumers [54]. The other variables of food values are considered to be normally distributed [54]. In order to see the effect of the heterogeneity and socio-demographic characteristics concerning food values, we grouped the Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian respondents into different sub-groups. In terms of gender, we categorized the respondents as female or male. While age was classified as below 40 or over 40 years old. In terms of the occupation, education, living place, having children in household, number of people in household, and income, they were grouped into full-time and not full-time employee, high and low education, urban and rural area, has children and does not have children, 1–2 family members and more than two family members, high and low income, respectively. The estimated results of the effects of the socio-demographic variables for Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian are shown in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. The reference group of the socio-demographic factors in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 followed the default setting in the R program. Further, the probability of socio-demographic characteristics for each country are shown in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 2.

The Results of LC-MNL Model with Socio-Demographic Variables (TAIWAN).

Table 3.

The Results of LC-MNL Model with Socio-Demographic Variables (JAPAN).

Table 4.

The Results of LC-MNL Model with Socio-Demographic Variables (INDONESIA).

Table 5.

Probability of Socio-Demographic Characteristics in Each Class (TAIWAN).

Table 6.

Probability of Socio-Demographic Characteristics in Each Class (JAPAN).

Table 7.

Probability of Socio-Demographic Characteristics in Each Class (Indonesia).

Table 2 shows (1) the overall comparison of food values based on each class share and (2) the effect of socio-demographic characteristics for Taiwanese consumers. Each class is distinguished as the minority group (Class 1), middle group (Class 2), or majority group (Class 3) based on the model statistics of the class shares. In comparison to the price factor, the characteristics of the majority group in Taiwan lean towards the following food values: Food safety certified, freshness, product origin label, high quality appearance, and plantations. However, the price factor is more important than domestic rarity in the majority group.

The socio-demographic factors within the LC-MNL model were compared between groups. Those who are older age (i.e., above 40 years old), 1–2 family members, and lower income (i.e., NTD75,000 or below) would tend to be in the majority. While the middle group only occupied about 23.2%, the food safety certified, the domestic rarity, freshness, and high-quality appearance are treated as important food values when compared to price. In particular, those who are male, not full-time employees, living in a rural area, and who have higher income would tend to be in the middle group. However, the price factor can still be a potential factor among food values for the middle group. Note that the price factor ranked as the second most important food value in the minority group. This means that price can still be an important factor in determining the purchasing preference for imported fruits and vegetables in Taiwan.

Table 3 presents (1) the overall outcomes of food value comparison based on each class share and (2) the effect of socio-demographic characteristics for Japanese consumers. In comparison to the price factor, the characteristics of the majority group in Japan lean towards the following food values: Food safety certified, freshness, product origin label, and plantations. Regarding the food values of high-quality appearance and domestic rarity, the price factor is more important for Japanese consumers. This means that the high-quality appearance and domestic rarity factors are not the most important factors for the majority of Japanese consumers.

The socio-demographic factors within the LC-MNL model were compared between groups. Those who are female, older age (i.e., older than 40 years old), not full-time employees, living in an urban area, have no children at home, and have higher income (i.e., JPY 7,000,001 or above) would tend to be in the majority group in Japan. While the class shares of the majority group in Japan has 46.6%, the middle group still held about 41.5% for the second big portion of the consumer group. The preference of food values in the middle group reveals a strong signal for the price factor. Note that Japanese consumers in the middle group treat the price factor as the most important food value. This implies that a big group of consumers show concern for the price factor in the purchase of imported fruits and vegetables in Japan. Only 12% of Japanese consumers are in the minority group. However, Japanese consumers in the minority group still show concern over freshness and price as the most and second most important food values in the purchase of imported fruits and vegetables. In particular, those who are younger, not full-time employees, have children at home, and only 1–2 people in a family tend to be in the minority group in Japan.

Table 4 presents (1) the overall outcomes of food value comparison based on each class share and (2) the effect of socio-demographic characteristics for Indonesian consumers. In comparison to the price factor, the characteristics of the majority group in Indonesia lean more on the following food values: Food safety certified, freshness, high quality appearance, and plantations. Regarding the food value of domestic rarity, the price factor is more important for Indonesian consumers of the majority group. This means that the domestic rarity factor is not the most important for the majority of Indonesian consumers if comparing to price. In other words, the attractiveness of the domestic rarity is not stronger than the price factor when Indonesian consumers are buying imported fruits and vegetables.

The socio-demographic factors within the LC-MNL model were compared between groups. Those who are living in rural areas would tend to be in the majority group. However, the class shares for the majority group in Indonesia held about 72.1%. This implies that we did not observe particular difference from their socio-demographic characteristics in the majority of Indonesian consumers. While the class shares of the minority group in Indonesia has only about 2.7%, the preference of food values of the minority group reveals a strong signal for domestic rarity, food safety certified, freshness, and high-quality appearance. In particular, those who are not full-time employees, lower education (i.e., 15 years or below), have children at home, and 1–2 people in their family would tend to be in the minority group. Note that Indonesian consumers in the middle group treat the price factor as the second most important food value, while freshness is the most important food value of the imported fruits and vegetables for this group in Indonesia.

Therefore, the price factor maintains a certain influencing level and a potential important food value among all three countries. There always are some consumers who care about the price of imported fruits and vegetables more than any other food values.

4.4. Probability and Share of Preferences of Socio-Demographic Characteristics

In order to examine the probability and the share of preferences of socio-demographic characteristics concerning imported fruit and vegetable purchasing in each class, the probability equation (i.e., Equation (1)) for the estimation is adopted. The results are exhibited in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

As mentioned before, the three classes of the latent class were named into majority group, middle group, and minority group. Table 5 exhibits the probability results of socio-demographic characteristics in each class for Taiwanese consumers. In this case, the majority group, middle group, and minority group had 60.35%, 23.21%, and 16.43% of baseline of the class share, respectively. The results indicate that Taiwanese consumers who were female tend to be in the majority group, because that item increases the baseline of the class share from 60.35% to 70.86%. On the other hand, Taiwanese consumers who had higher education, who were living in urban area, had children at home, and had 1–2 people in their household tended to be in the majority group. Older Taiwanese consumers tended to be in the minority and middle group. Taiwanese consumers who had a full-time job and were living in the urban area were inclined to be in the minority group, while those who had higher income were prone to be in the middle group in Taiwan. The overall outcomes in Table 5 reveal that many Taiwanese consumers with different socio-demographic characteristics would be potentially targeted to promote imported fruits and vegetables.

In terms of the Japanese respondents, Table 6 presents that the baseline of the class share for the majority, middle, and minority groups are 46.56%, 41.46%, and 11.98%, respectively. The results also show that female participants tend to be in the majority group because that factor increases the baseline of the class share from 46.56% to 59.34%. Furthermore, the Japanese consumers who had higher education, were living in the urban area, and had higher income tended to be in the majority group as well. On the other hand, the Japanese consumers who had a full-time job and had children at home were inclined to be in the middle group, whereas consumers who were older, had children at home, and had 1–2 people in the household tended to be in the minority group. While the majority and the middle groups are separated, the class shares of these two groups are very closed to each other. Thus, Japanese consumers in these two groups present a different set of socio-demographic factors. However, this further implies that there may not exist a dominant consumer group for Japanese consumers, since the highest class share is less than 50%.

Table 7 presents the probability of socio-demographic characteristics in each class of Indonesian consumers. In this case, the baseline of the class share for the majority, the middle, and the minority groups were 72.09%, 25.19%, and 2.71%, respectively. The results showed that Indonesian consumers who had 1–2 people in the household tended to be in the majority group because it increased the baseline of the class share from 72.09% to 72.43%. Further, the Indonesian consumers who were female, of older age, a full-time employee, had higher education, living in an urban area, had children at home, and had a higher income were inclined to be in the middle group. Moreover, the Indonesian consumers who were female, living in urban area, had children at home, had 1–2 people in the household, and had higher income tended to be in the minority group. It is important to note that the Indonesian consumers in the majority group only exhibit one particular socio-demographic factor to be identified as interesting for imported fruits and vegetables, while those who are in the middle and minority group reveal more than 10 particular socio-demographic factors interesting for imported fruits and vegetables. This shows that the imported fruits and vegetables in Indonesia will be interested in a smaller portion of consumer groups.

5. Discussion

This study finds that the most important food value amongst consumers in Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia is the food safety certified. The null hypothesis in this study indicates that consumers in each country would not treat food safety certified as their purchasing reference. This finding is consistent with prior research, which discovered that food safety is the most important food value for market consumers in some countries such as the U.S. [10,12], in Thailand [55], in Norway [10], and in France [56]. According to the findings of these studies, most consumers around the world are highly concerned about food safety.

Product labeling not only includes the food safety certified information, but also comprises the information regarding the product country of origin, the harvest date, and the best-before date, which can be provided to consumers [57,58,59]. The null hypothesis in this study indicates that consumers in each country would not treat the product origin label as their purchasing reference. Indeed, it clearly shows in this study that the country-of-origin labelling ranks within the top three most important food values for Japanese and Taiwanese consumers. Most Indonesian people do not take an interest in the country-of-origin labelling. This finding is not in accordance with the previous work of Slamet and Nakayasu (2017) [59] who found that Indonesian respondents pay attention to the labelling information, including the harvest date, best-before date, content of nutrient, brand, and product origin, but they are not concerned with the sensory appeal (such as texture, color, smell, freshness, taste, and good appearance) when they purchase fruits and vegetables. One possible explanation of this may be because we are testing the preference of imported fruits and vegetables, and the Indonesian consumers may treat domestically grown and imported food products differently.

Furthermore, the majority group of Indonesian respondents choose freshness and high-quality appearance as the second and the third most important food value, respectively, after food value of food safety certified. The reason could be that they can choose various kinds of products from different brands, countries of origin, and nutrition in the market. Therefore, these factors are less significant in their perspectives. Those Japanese respondents choose the high quality appearance as the least important food value. This outcome might be due to the fact that related dates on the product packaging and the product appearance is less important compared to the actual condition of the product, specifically, if the product is still in good condition, whereas the majority and the minority group of Taiwanese respondents who choose domestic rarity and how the product is grown (for the middle group) as the least important food value might do so because the domestic products are more common and familiar.

The results show the similarities and differences in terms of socio-demographic characteristics of consumers in Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia. We consider the majority group of each country as the target consumer group for domestic marketers to promote imported fruits and vegetables. Consumers who are female, have higher education, who live in an urban area, and have high income belong to the majority group of Japanese buyers. Likewise, the majority group of Taiwanese consumers are female, full-time employee, have higher education, live in an urban area, have children at home, and have 1–2 people in the household. One cause could be that most Japanese and Taiwanese families are nuclear families with a small and steady in income; thus, they are dependent and can affordably buy those imported fruits. Nevertheless, for the majority of Indonesian groups, only those who have 1–2 people in a household (small family size) prefer imported fruits and vegetables. It is clear to see that the preferences of imported fruits and vegetables are much differentiated among these three countries, and imported fruits and vegetables in Indonesia might only be attractive for a small niche market.

Policy Implications

The outcomes of this study provide a series of policy implications that may be referred to for exporting and importing countries. The number one finding in this study shows that consumers incline to buy imported fruits that are not commonly provided by domestic producers. This shows that there is a market demand for imported fruit products, especially for those not commonly produced in a domestic market. The number two finding in this study reveals that food safety certified is the most important food value for these three countries. Therefore, the policy implication should focus on food safety certified regulations to maintain and protect consumer trust concerning imported fruits and vegetables. While freshness was found to be the second most important food value for consumers in these three countries, regulating the freshness as a food policy may not be so urgent as food safety certification, because consumers will automatically decrease the purchase of non-freshness products.

The number three important finding exhibits that the majority of Taiwanese and Japanese consumers (i.e., female, higher education, and from an urban area) prefer imported fruits and vegetables, while the majority of Indonesian consumers are not big fans of imported fruits and vegetables. This reveals that the implication of food safety regulation for these three countries may have a different orientation. The majority of consumers in Taiwan and Japan are identified for the imported fruits and vegetables in this study, which means that the majority of consumers will appreciate the food control of food safety regulation in these two countries. While the majority group of Indonesian consumers is not identified for the interests of imported fruits and vegetables, food safety control still remains a global trend nowadays.

6. Conclusions

Agricultural international trade has received great attention in recent years, while international trade marketers face a high threshold to be successful in their decision making regarding the different characteristics of targeted countries. Further, the preferences of imported fruits were explored. Results show that consumers may tend to purchase imported fruits that may have geographical limitation. Indonesian and Taiwanese consumers may tend to buy imported strawberries, grapes, Asian pears, and peaches, while Japanese consumers may be inclined to buy imported bananas and mangos.

The significance of this study was to explore how food values of imported fruits and vegetables are treated by Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian consumers. Food values, i.e., product origin label, food safety certified, high quality appearance, domestic rarity, price, plantations, and freshness, were identified, evaluated, and analyzed through the LC-MNL model. Results show that food safety certified and freshness factors are consistently rated as the most and second important food values amongst the majority of consumer groups in these three countries when compared to price. While other food values of imported fruits and vegetables in these countries do not rate at the same level, the price factor is considered as the most or second most important food value for the middle or minority consumer groups in these three countries. Thus, it implies that some potential consumer groups care about price as a factor in considering whether they would like to buy imported fruits and vegetables. According to these results, we can summarize that the majority group of Taiwanese, Japanese, and Indonesian consumers in this study are concerned with food safety certified and freshness. This suggests that fruit and vegetable exporters should pay attention to the safety certified label and the freshness of their products.

While the significance of food values for imported fruits and vegetables is identified, identifying the food values with the socio-demographic factors of potential consumers would be the key step for targeting consumer groups. Results show that Taiwanese and Japanese consumers in the majority group are confirmed potential markets of imported fruits and vegetables. In particular, those who are female, have a higher education, and live in an urban area tend to be in the majority group, shopping for imported fruits and vegetables in Taiwan and Japan. However, it is somewhat surprising that the majority of Indonesian consumers who shop for imported fruits live in a small family (1–2 people in a household). Further, the majority Indonesian consumer group occupied over 72% in total, so this means that Indonesian consumers who are interested in imported fruits tend to be in a small niche market (i.e., the minority and middle consumer groups). The potential market of imported fruits for Indonesian consumers was surprisingly not as big as the Taiwanese and Japanese market. However, at a minimum, we are able to identify many food values with socio-demographic factors that are important to the minority and middle group for Indonesian consumers.

The contribution of this study is especially related to the preferred food values of imported fruits (and potentially vegetables) among consumers in Taiwan, Japan, and Indonesia. Finding potential consumers for purchasing imported fruits and vegetables assists producers and exporters in their international market penetration. Limitations are inevitable. The data from each country are not for the same year, while the survey question of the preferred fruit products only adopts the specific type of fruit and no vegetables. Future study is encouraged to increase the sample size to cover the entire country. Future studies may consider the elicitation of the willingness to pay for the imported fruits and vegetables since it may provide more pricing strategy for specific product alternatives [60].

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae7120578/s1, Supplementary Material 1: Survey for Imported Fruits and Vegetable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.Y. and B.P.P.; methodology, S.-H.Y. and B.P.P.; software, S.-H.Y.; validation, S.-H.Y.; formal analysis, S.-H.Y.; investigation, S.-H.Y. and B.P.P.; resources, S.-H.Y.; data curation, S.-H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-H.Y. and B.P.P.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.Y.; visualization, S.-H.Y.; supervision, S.-H.Y.; project administration, S.-H.Y.; funding acquisition, S.-H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [Council of Agriculture, grant number: 105 農科-13.4.2-企-Q1] and the APC was funded by [Council of Agriculture, grant number: 110農科-2.2.3-牧-U2].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this research may be accessible from the corresponding author upon request. The data are not publicly accessible because research participants did not consent to their data being released publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cummins, A.M.; Olynk Widmar, N.J.; Croney, C.C.; Fulton, J.R. Understanding Consumer Pork Attribute Preferences. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2016, 6, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Global Trade Patterns in Fruit and Vegetables; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, A.; de-Magistris, T. Consumer Preferences for Food Labeling: What Ranks First? Food Control 2016, 61, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Chen, C.I.; Sher, P.J. Investigation on Perceived Country Image of Imported Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Briggeman, B.C. Food Values. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Norwood, F.B. Animal Welfare Economics. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2011, 33, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M.; Louviere, J.J. Using Best-Worst Scaling Methodology to Investigate Consumer Ethical Beliefs across Countries. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Grunert, K.G. The Perceived Healthiness of Functional Foods: A Conjoint Study of Danish, Finnish and American Consumers’ Perception of Functional Foods. Appetite 2003, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J. A Choice Experiment Model for Beef: What US Consumer Responses Tell Us about Relative Preferences for Food Safety, Country-of-Origin Labeling and Traceability. Food Policy 2007, 32, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzani, C.; Gustavsen, G.W.; Nayga, R.M.J.; Rickertsen, K. Are Consumers’ Preferences for Food Values in the U. S. and Norway Similar? A Best-Worst Scaling Approach. In Proceedings of the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 31 July–2 August 2016; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chern, W.S.; Rickertsen, K.; Tsuboi, N.; Fu, T.-T. Nervous Disorders of Swallowing. AgBioForum 2002, 5, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.B.; Lusk, J.L.; Norwood, F.B. How closely do hypothetical surveys and laboratory experiments predict field behavior? Am. J. Agr. Econ. 2009, 91, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, J. Comparisons of Taste Perceptions and Preferences of Japanese and Australian Consumers: Overview and Implications for Cross-Cultural Sensory Research. Food Qual. Prefer. 1998, 9, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ Perceptions and Preferences for Local Food: A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndraha, N.; Hsiao, H.I.; Chih Wang, W.C. Comparative Study of Imported Food Control Systems of Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the European Union. Food Control 2017, 78, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Trade opportunities in Southeast Asia: Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/2018-07_iatr_se_asia_0.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Dekhili, S.; Sirieix, L.; Cohen, E. How Consumers Choose Olive Oil: The Importance of Origin Cues. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.; Kashiwagi, A. Gain Report—Global Agricultural Information Network: The Japanese Processed Vegetable Market—Changes and Opportunities. Available online: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- USDA. Japanese Fresh Fruit Market Overview 2018 (JA8706). Available online: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Japanese%20Fresh%20Fruit%20Market%20Overview%202018_Osaka%20ATO_Japan_10-30-2018.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Council of Agriculture Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (2017). Import by Food Groups. Available online: https://eng.coa.gov.tw/upload/files/eng_web_structure/2505521/BB_B04-2-01-B04-2-11_106.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- USDA. Taiwan Exporter Guide 2018 (TW18016). Available online: https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Exporter%20Guide%20_Taipei%20ATO_Taiwan_12-5-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Sinaga, A.M.; Yusnita, E.; Arifatus, A.; Hariantoko, H. Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Local and Imported Citrus. In Proceedings of the ICSAFS Conference Proceedings, 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security: A Comprehensive Approach, Jatinangor, Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia, 12–13 October 2015; Muhaemin, M., Hidayat, Y., Lengkey, H.A.W., Eds.; KnE Publishing: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Business Guide Indonesia. Overview of Indonesia’s Horticulture Sector-Fruit & Vegetables. Available online: http://www.gbgindonesia.com/en/agriculture/article/2012/overview_of_indonesia_s_horticulture_sector_fruit_vegetables.php (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Ariyanti, F. Daftar Negara Pemasok Buah Dan Sayur Terbesar Ke RI [in Indonesian]. Available online: https://www.liputan6.com/bisnis/read/3168268/daftar-negara-pemasok-buah-dan-sayur-terbesar-ke-ri (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Feng, N.; Zhang, A.; van Klinken, R.D.; Cui, L. An Integrative Model to Understand Consumers’ Trust and Willingness to Buy Imported Fresh Fruit in Urban China. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2216–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, A.; Schwartz, S.H. Values and Behavior: Strength and Structure of Relations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Manyiwa, S. Determining Linkages between Consumer Choices in a Social Context and the Consumer’s Values: A Means–End Approach. J. Consum. Behav. 2001, 2, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, D.; Fulponi, L. Emerging Public Concerns in Agriculture: Domestic Policies and International Trade Commitments. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 1999, 26, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Devine, C.M. Managing Values in Personal Food Systems. Appetite 2001, 36, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H.; vanOphem, J. Food Consumption Value: Developing a Consumer-Centred Concept of Value in the Field of Food. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L. External Validity of the Food Values Scale. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trading Economics. Taiwan GDP. Retrieved from Trading Economics. 2021. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/taiwan/gdp (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Trading Economics. Japan GDP. Retrieved from Trading Economics. 2021. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/gdp (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Trading Economics. Indonesia GDP. Retrieved from Trading Economics. 2021. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/indonesia/gdp (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Cohen, S.H. Maximum Difference Scaling: And Preference for Segmentation. Sawtooth Softw. Res. Pap. Ser. 2003, 98382, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.; Louviere, J. The Best-Worst Scaling Approach: An Alternative to Schwartz’s Values Survey. J. Pers. Assess. 2008, 90, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casini, L.; Corsi, A.M.; Goodman, S. Consumer Preferences of Wine in Italy Applying Best-Worst Scaling. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A.; Louviere, J.J. Determining the Appropriate Response to Evidence of Public Concern: The Case of Food Safety. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Applying Best-Worst Scaling to Wine Marketing. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-Magistris, T.; Gracia, A.; Albisu, L.M. Wine Consumers’ Preferences in Spain: An Analysis Using the Best-Worst Scaling Approach. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 12, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, L.; Cohen, E. Using Product and Retail Choice Attributes for Cross-National Segmentation. Eletronic Libr. 2011, 45, 1236–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Parker, N. Consumer Preferences for Amount and Type of Fat in Ground Beef. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Jørgensen, A.S.; Aaslyng, M.D.; Bredie, W.L.P. Best-Worst Scaling: An Introduction and Initial Comparison with Monadic Rating for Preference Elicitation with Food Products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Cardello, A.V. Direct and Indirect Hedonic Scaling Methods: A Comparison of the Labeled Affective Magnitude (LAM) Scale and Best-Worst Scaling. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menictas, C.; Wang, P.Z.; Louviere, J.J. Assessing the Validity of Brand Equity Constructs. Australas. Mark. J. 2012, 20, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K.; Akai, K.; Ujiie, K. A Choice Experiment to Compare Preferences for Rice in Thailand and Japan: The Impact of Origin, Sustainability, and Taste. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, C.J. Consumer Preferences for Food Labelling Attributes: Comparing Direct Ranking and Best-Worst Scaling for Measurement of Attribute Importance, Preference Intensity and Attribute Dominance. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 29, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizaki, H.; Nakatani, T.; Sato, K. Stated Preference Methods Using R; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassani, M.Z.; Locker, D.; Elmesallati, A.A.; Devlin, H.; Mohammadi, T.M.; Hajizamani, A.; Kay, E.J. Dental Health State Utility Values Associated with Tooth Loss in Two Contrasting Cultures. J. Oral Rehabil. 2009, 36, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrias, M.; Daziano, R.A. Multinomial Logit Models with Continuous and Discrete Individual Heterogeneity in R: The Gmnl Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 79, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Graff, L.E.; Howell, K.H.; Martinez-Torteya, C.; Hunter, E.C. Typologies of Childhood Exposure to Violence: Associations with College Student Mental Health. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIA. The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Lusk, J.L.; Roosen, J.; Fox, J.A. Demand for Beef from Cattle Administered Growth Hormones or Fed Genetically Modified Corn: A Comparison of Consumers in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaiyotin, P.; Ujiie, K.; Shuto, H. An Evaluation of Consumers’ Preference on Food Safety Certificate and Product Origins: A Choice Experiment Approach for Fresh Oranges in Metropolitan Bangkok, Thailand. Agric. Inf. Res. 2015, 24, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wange, E.P.; Gao, Z.; Heng, Y. Improve Access to the EU Market by Identifying French Consumer Preference for Fresh Fruit from China. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insch, A.; Jackson, E. Consumer Understanding and Use of Country-of-Origin in Food Choice. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Gao, Z.; Swisher, M.; Zhao, X. Consumers’ Preferences for Fresh Broccolis: Interactive Effects between Country of Origin and Organic Labels. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamet, A.S.; Nakayasu, A. Consumer Preferences for Traceable Fruit and Vegetables and Their Influencing Factor in Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Futur. Hum. Secur. 2017, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T.P.; Adamowicz, W.L.; Carlsson, F. Choice experiments. In A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 133–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).