Establishment of an Effective Gene Editing System for ‘Baihuayushizi’ Pomegranate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Vector Construction and A. tumefaciens Preparation

2.3. Evaluation of the Effects of Different Propagation Cycles on Callus Induction

2.4. Determination of the Upper Limit of Kanamycin Concentration

2.5. Screening of the Optimal Timentin Concentration

2.6. Orthogonal Array for Determining the Importance of Four Factors for Transformation System

2.7. Detection of Gene-Edited Plants

2.8. Data Statistical Analysis

3. Results

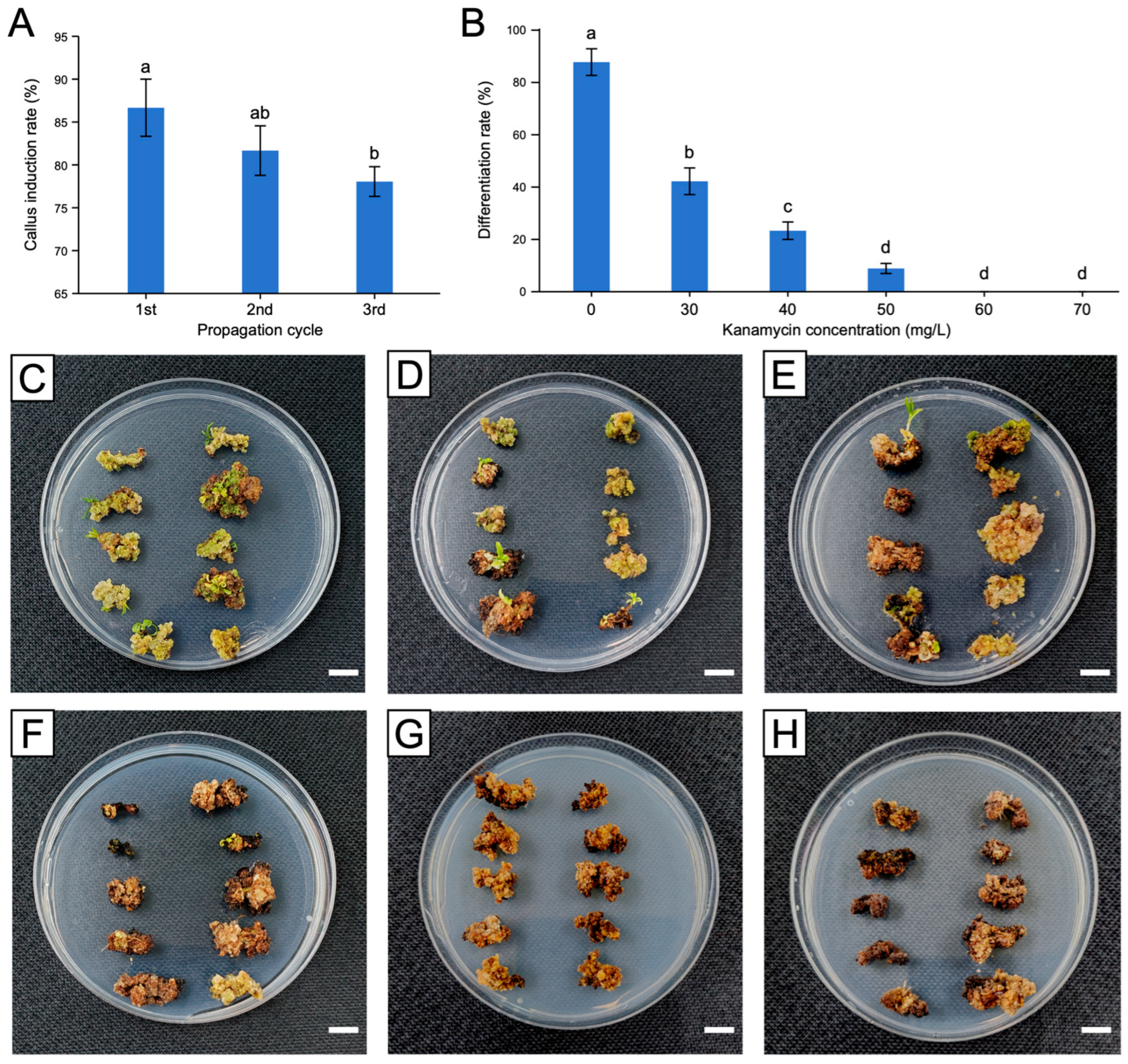

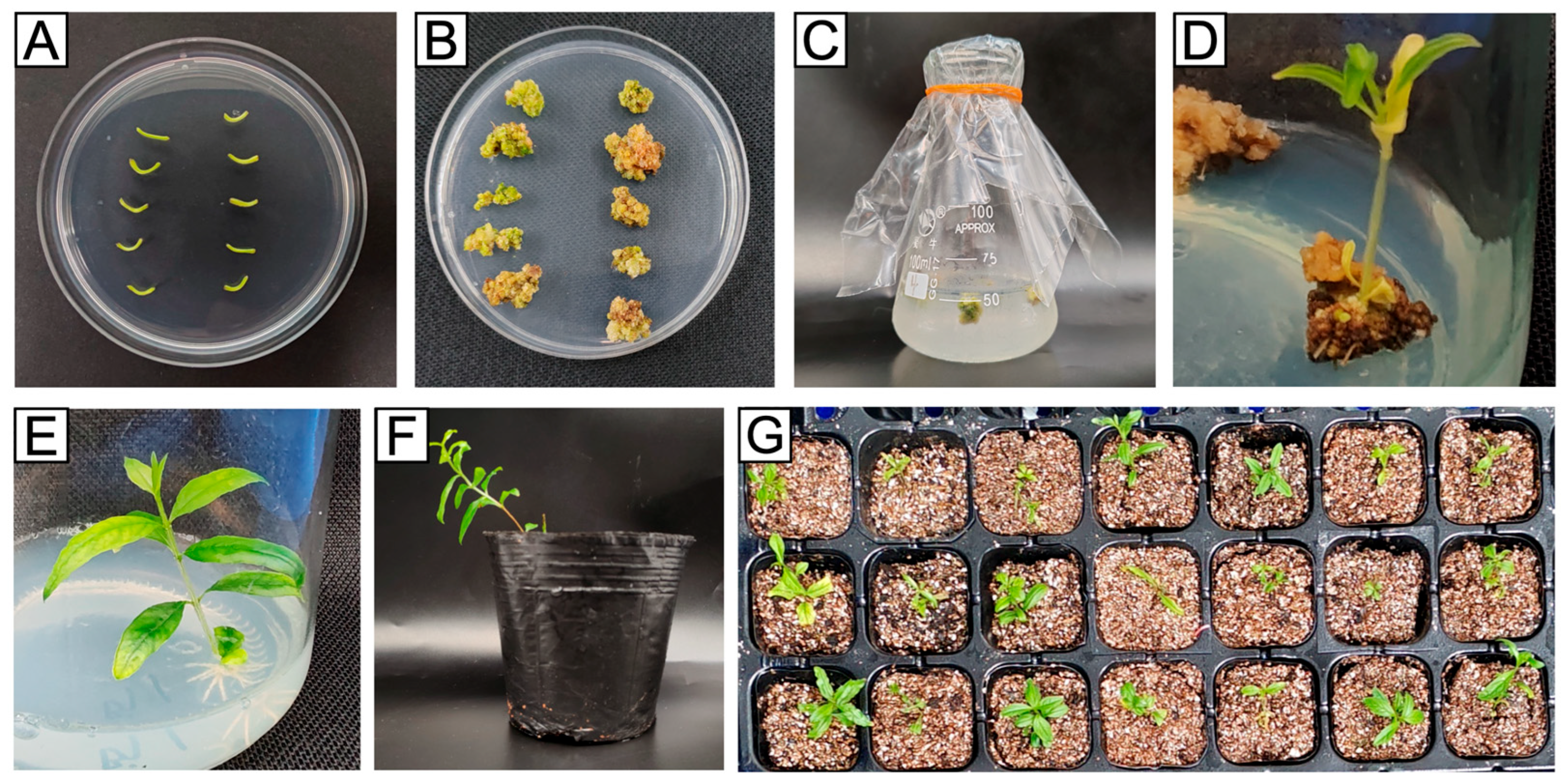

3.1. Optimal Propagation Cycle and Kanamycin Concentration for Callus Induction

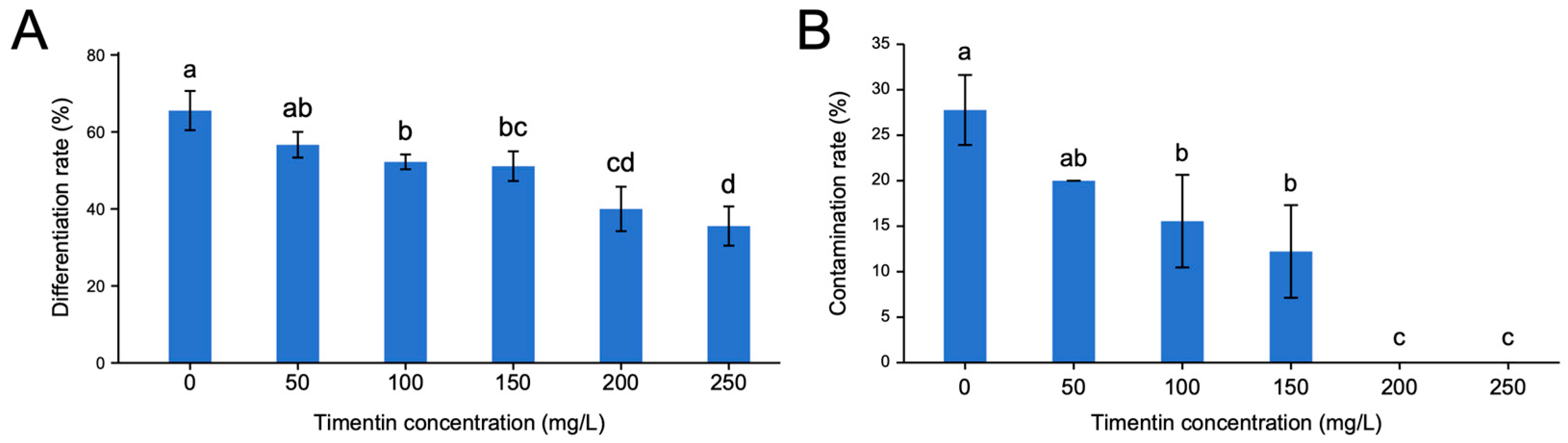

3.2. Effects of Different Timentin Concentrations on Adventitious Bud Differentiation

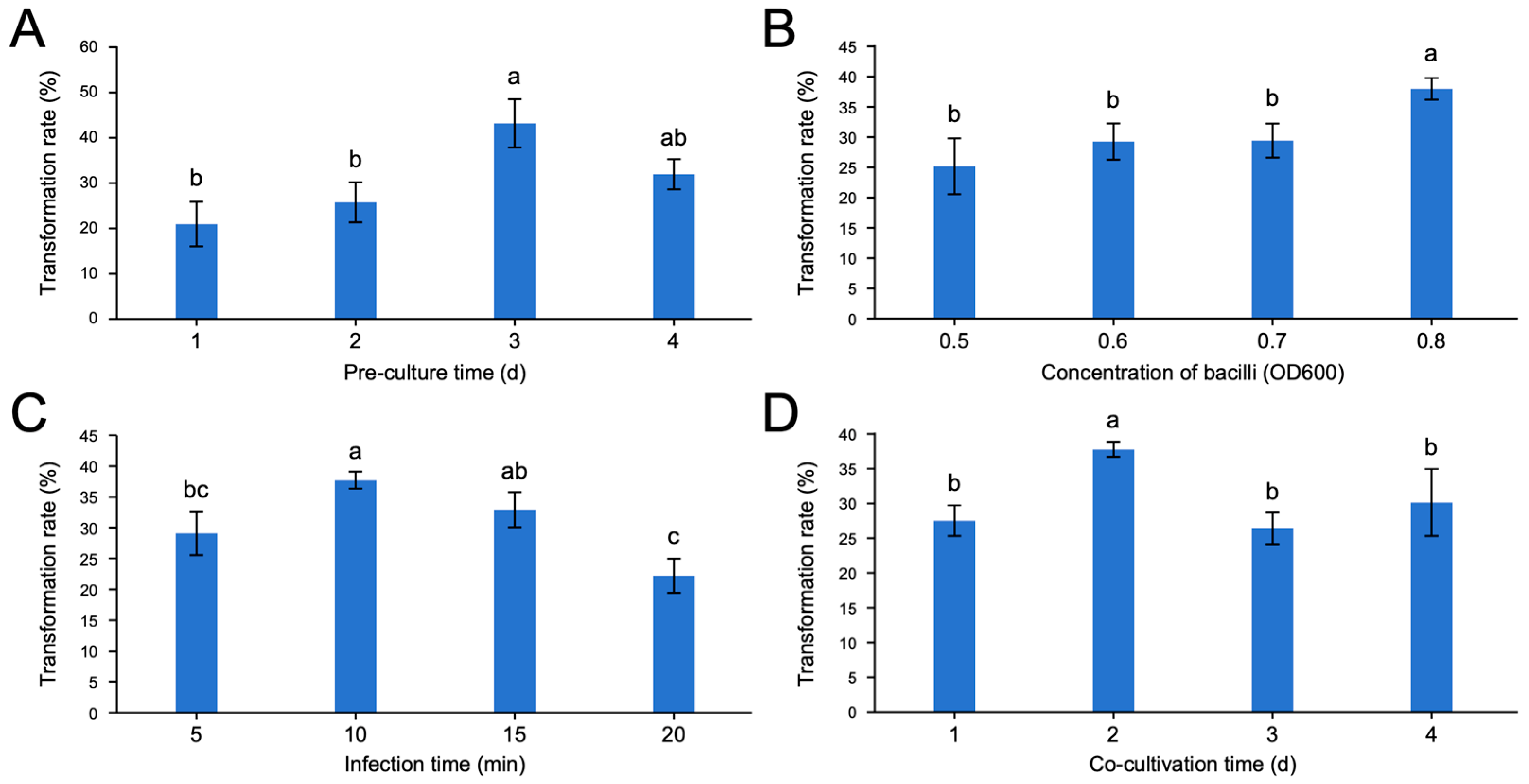

3.3. Optimal Levels of the Four Factors for Transformation System of ‘Baihuayushizi’ Pomegranate

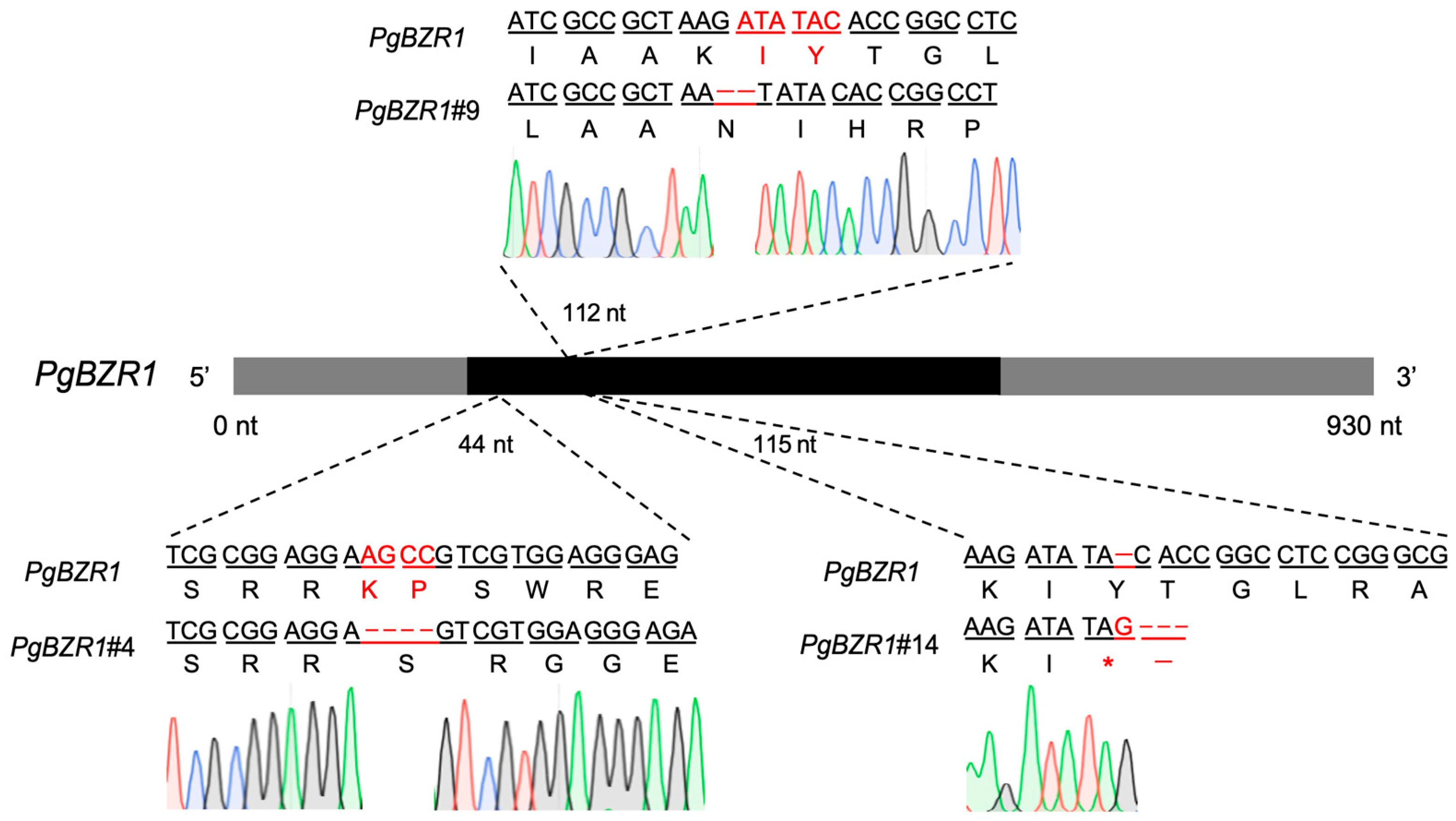

3.4. Sequencing Validation of Transgenic Pomegranate Plants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.C.; Qu, H.Z.; Zhang, X.W. Research advances of pomegranate in China. Hebei J. For. Orchard. Res. 2005, 20, 265–267, 272. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L.F.; Luo, H.; Bi, R.X.; Hao, Z.X.; Tan, W.; Zhang, L.H. Review and prospect of pomegranate breeding in China in the past 40 years. North. Hortic. 2022, 24, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, T.; Liu, R.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, L.; Jing, D.; Yang, X.; et al. A telomere-to-telomere gap-free assembly integrating multi-omics uncovers the genetic mechanism of fruit quality and important agronomic trait associations in pomegranate. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2852–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.G.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Orbović, V.; Xu, J.; White, F.F.; Jones, J.B.; Wang, N. Genome editing of the disease susceptibility gene CsLOB1 in citrus confers resistance to citrus canker. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varkonyi-Gasic, E.; Wang, T.C.; Voogd, C.; Jeon, S.; Drummond, R.S.M.; Gleave, A.P.; Allan, A.C. Mutagenesis of kiwifruit CENTRORADIALIS-like genes transforms a climbing woody perennial with long juvenility and axillary flowering into a compact plant with rapid terminal flowering. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Tu, M.X.; Wang, D.J.; Liu, J.W.; Li, Y.J.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, X.P. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated efficient targeted mutagenesis in grape in the first generation. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.X.; Zhang, Y.T.; Dong, J.; Zhang, L.X. Retrospection and Prospect of Strawberry Breeding in China. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2008, 9, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, S.K.; Pattnaik, S.; Chand, P.K. High frequency axillary shoot proliferation and plant regeneration from cotyledonary nodes of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2000, 85, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.J.; Wu, S.; Tian, L. Effective genome editing and identification of a regiospecific gallic acid 4-O-glycosyltransferase in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xia, X.; Qin, G.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W.; Qian, M.; Li, J.; Cui, G.; Yang, Y.; et al. Somatic Embryogenesis and Plant Regeneration from Stem Explants of Pomegranate. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; An, Y.; Huang, L.C.; Zeng, W.; Lu, M.Z. Establishment of A Transient Transformation System for Stem Segments of Poplar 84K. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 57, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q.; Shen, X.; He, Y.M.; Ren, T.N.; Wu, W.T.; Xi, T. An optimized freeze-thaw method for transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 and LBA4404. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 18, 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.Y.; Yu, W.X.; Zhao, Y.X.; Chen, Y.C.; Gao, M.; Wu, L.W.; Wu, S.Q.; Wang, Y.D. Establishment of Agrobacterium Mediated Genetic Transformation System of Litsea cubeba. For Res. 2022, 35, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.N.; Lu, J. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene editing in trees. Hereditas 2020, 42, 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.N.; Yao, F.G.; An, Y.; Jiang, C.; Chen, N.N.; Huang, L.C.; Lu, M.Z.; Zhang, J. Application of CRISPR/Cas genome editing in woody plant trait improvement. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2025, 70, 2509–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattapaglia, D.; Silva-Junior, O.B.; Resende, R.T.; Cappa, E.P.; Müller, B.S.F.; Tan, B.; Isik, F.; Ratcliffe, B.; El-Kassaby, Y.A. Quantitative genetics and genomics converge to accelerate forest tree breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Regulation of somatic embryogenesis in higher plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2010, 29, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri-Dehkordi, A.; Naderi, R.; Martinelli, F.; Salami, S.A. A robust workflow for indirect somatic embryogenesis and cormlet production in saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and its wild allies; C. caspius and C. speciosus. Heliyon 2020, 6, e5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral-Silva, P.M.; Clarindo, W.R.; Guilhen, J.H.S.; Passos, A.B.R.d.J.; Sanglard, N.A.; Ferreira, A. Global 5-methylcytosine and physiological changes are triggers of indirect somatic embryogenesis in Coffea canephora. Protoplasma 2021, 258, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alquézar, B.; Bennici, S.; Carmona, L.; Gentile, A.; Peña, L. Generation of Transfer-DNA-Free Base-Edited Citrus Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 835282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Stürchler, A.; Anjanappa, R.B.; Zaidi, S.S.; Hirsch Hoffmann, M.; Gruissem, W.; Vanderschuren, H. Linking CRISPR-Cas9 interference in cassava to the evolution of editing-resistant geminiviruses. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkonyi-Gasic, E.; Wang, T.; Cooney, J.; Jeon, S.; Voogd, C.; Douglas, M.J.; Pilkington, S.M.; Akagi, T.; Allan, A.C. Shy Girl, a kiwifruit suppressor of feminization, restricts gynoecium development via regulation of cytokinin metabolism and signalling. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1461–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Wu, S.; Dou, T.; Zhu, H.; Hu, C.; Huo, H.; He, W.; Deng, G.; Sheng, O.; Bi, F.; et al. Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system to create MaGA20ox2 gene-modified semi-dwarf banana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.G.; Wang, N. Targeted genome editing of sweet orange using Cas9/sgRNA. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Li, Y.F.; Wang, A.Q.; Wang, J.Y.; Deng, C.Y.; Lu, M.; Ma, J.Y.; Dai, S.L. Establishment of Regeneration and Genetic Transformation System for Chrysanthemum × morifolium ‘Wandai Fengguang’. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2025, 60, 597–610. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.L.; Cai, Z.J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, G.F. Establishment of agrobacterium-mediated transformation System for Populus simonii×P.nigra plants. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2009, 9, 196–199, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.H.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, Z.X.; Li, M.F.; Guo, S.J.; Cao, X.S.; Ji, L.S. Establishment of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation system of Capsicum annuum. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2019, 31, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, C.L.; Chen, H.M.; Liu, X.H.; Yang, K.K.; Chen, C. Optimization of the genetic transformation system for the ecotype cucumber ‘CU2’ in South China. J. China Capsicum 2024, 22, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Finer, J.J. Low Agrobacterium tumefaciens inoculum levels and a long co-culture period lead to reduced plant defense responses and increase transgenic shoot production of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2016, 52, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.F.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, R.R.; Qi, S.Z.; Kong, L.S.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, J.F. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of hybrid sweetgum embryogenic callus. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2021, 43, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Hu, R.; Yang, L.; Zuo, Z. Establishment of a Transient Transformation Protocol in Cinnamomum camphora. Forests 2023, 14, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Pre-Culture Time (d) | Concentration of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (OD600) | Infection Time (min) | Co-Culture Time (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | |||||

| K1 | 83.85 | 100.7 | 116.41 | 110.06 | |

| K2 | 103.06 | 117.14 | 150.79 | 151.07 | |

| K3 | 172.75 | 117.67 | 131.59 | 105.75 | |

| K4 | 127.79 | 151.94 | 88.66 | 120.57 | |

| k1 | 20.96 | 25.18 | 29.1 | 27.52 | |

| k2 | 25.77 | 29.28 | 37.7 | 37.77 | |

| k3 | 43.19 | 29.42 | 32.9 | 26.44 | |

| k4 | 31.95 | 37.98 | 22.16 | 30.14 | |

| R | 22.23 | 12.81 | 15.53 | 11.33 | |

| Treatments | Pre-Culture Time (d) | Concentration of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (OD600) | Infection Time (min) | Co-Culture Time (d) | Transformation Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 | 1 | 14.18 e |

| 2 | 1 | 0.6 | 10 | 2 | 40.55 bc |

| 3 | 1 | 0.7 | 15 | 3 | 16.10 de |

| 4 | 1 | 0.8 | 20 | 4 | 13.02 e |

| 5 | 2 | 0.5 | 10 | 2 | 16.84 de |

| 6 | 2 | 0.6 | 5 | 1 | 20.63 de |

| 7 | 2 | 0.7 | 20 | 4 | 19.70 de |

| 8 | 2 | 0.8 | 15 | 3 | 45.84 ab |

| 9 | 3 | 0.5 | 15 | 3 | 46.24 ab |

| 10 | 3 | 0.6 | 20 | 4 | 32.50 c |

| 11 | 3 | 0.7 | 5 | 1 | 41.24 b |

| 12 | 3 | 0.8 | 10 | 2 | 52.77 a |

| 13 | 4 | 0.5 | 20 | 4 | 23.44 d |

| 14 | 4 | 0.6 | 15 | 3 | 23.41 d |

| 15 | 4 | 0.7 | 10 | 2 | 40.63 bc |

| 16 | 4 | 0.8 | 5 | 1 | 40.31 bc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, C.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qian, J. Establishment of an Effective Gene Editing System for ‘Baihuayushizi’ Pomegranate. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010064

Wu C, Xu Q, Wang Q, Ding W, Wang Y, Yang Y, Qian J. Establishment of an Effective Gene Editing System for ‘Baihuayushizi’ Pomegranate. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Chengcheng, Qingyang Xu, Qilin Wang, Wenhao Ding, Yuqing Wang, Yuchen Yang, and Jingjing Qian. 2026. "Establishment of an Effective Gene Editing System for ‘Baihuayushizi’ Pomegranate" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010064

APA StyleWu, C., Xu, Q., Wang, Q., Ding, W., Wang, Y., Yang, Y., & Qian, J. (2026). Establishment of an Effective Gene Editing System for ‘Baihuayushizi’ Pomegranate. Horticulturae, 12(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010064