Exogenous Putrescine Application Mitigates Chill Injury in Melon Fruit During Cold Storage by Regulating Polyamine Metabolism and CBF Gene Expression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatment

2.2. Determination and Calculation of Chilling Injury Index

- Grade 0: No browning or chilling injury spots on the peel.

- Grade 1: Slight browning on the peel; affected area ≤ 10%.

- Grade 2: Obvious browning spots on the peel; affected area between 11% and 25%.

- Grade 3: Severe browning on the peel; affected area between 26% and 50%.

- Grade 4: Very severe browning on the peel; affected area ≥ 50%.

2.3. Determination of Endogenous Polyamine Content

2.4. Measurement of Key Enzyme Activity

2.5. Expression Analysis of CmCBF and CmPA Genes in Yellow Melon

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

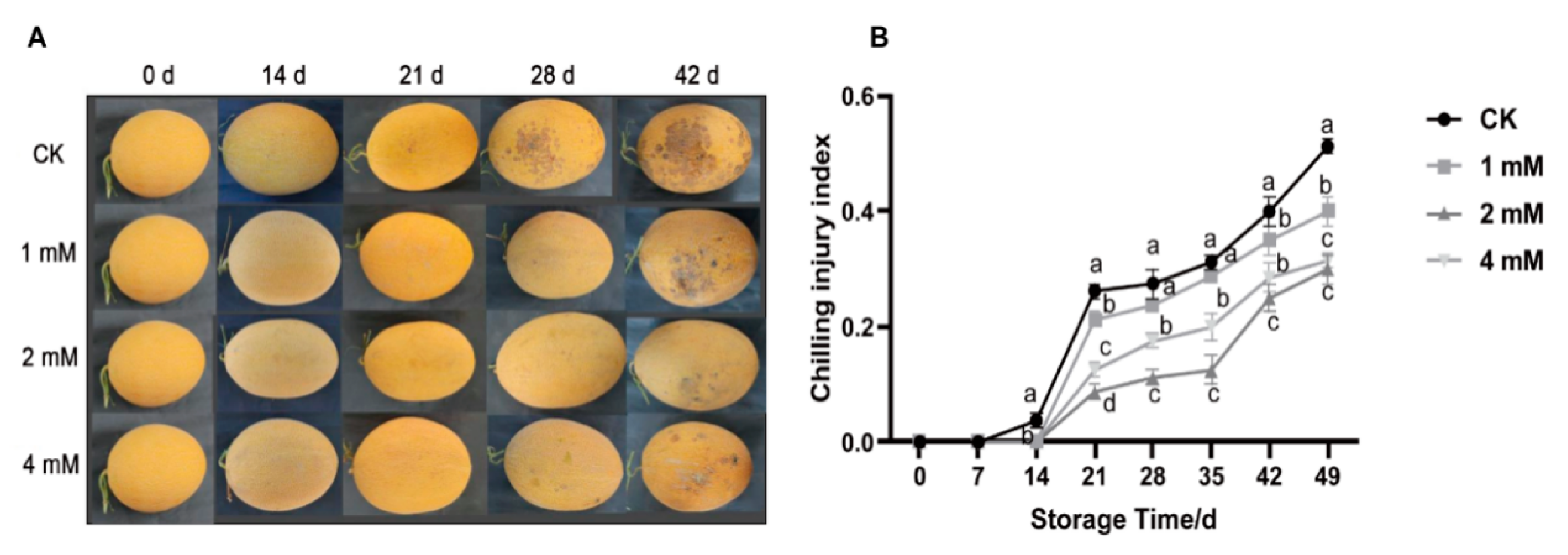

3.1. Effect of Put on Visual Quality and CI Index of Yellow Melon Fruit in Cold Storage

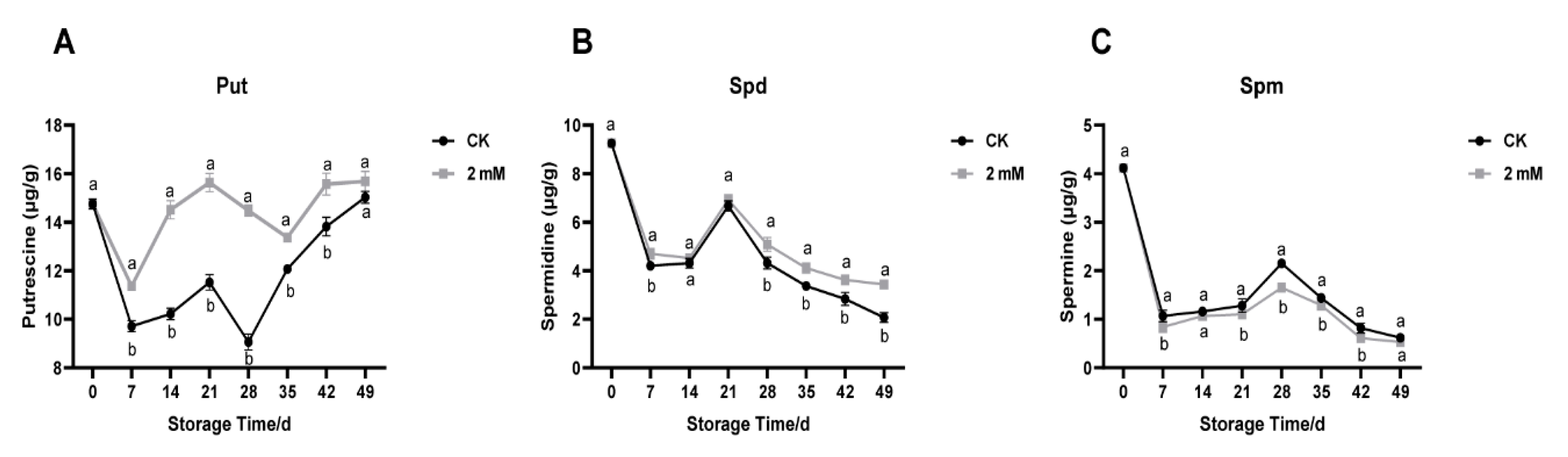

3.2. Temporal Changes in Endogenous Polyamine Levels in Stored Yellow Melon Fruit

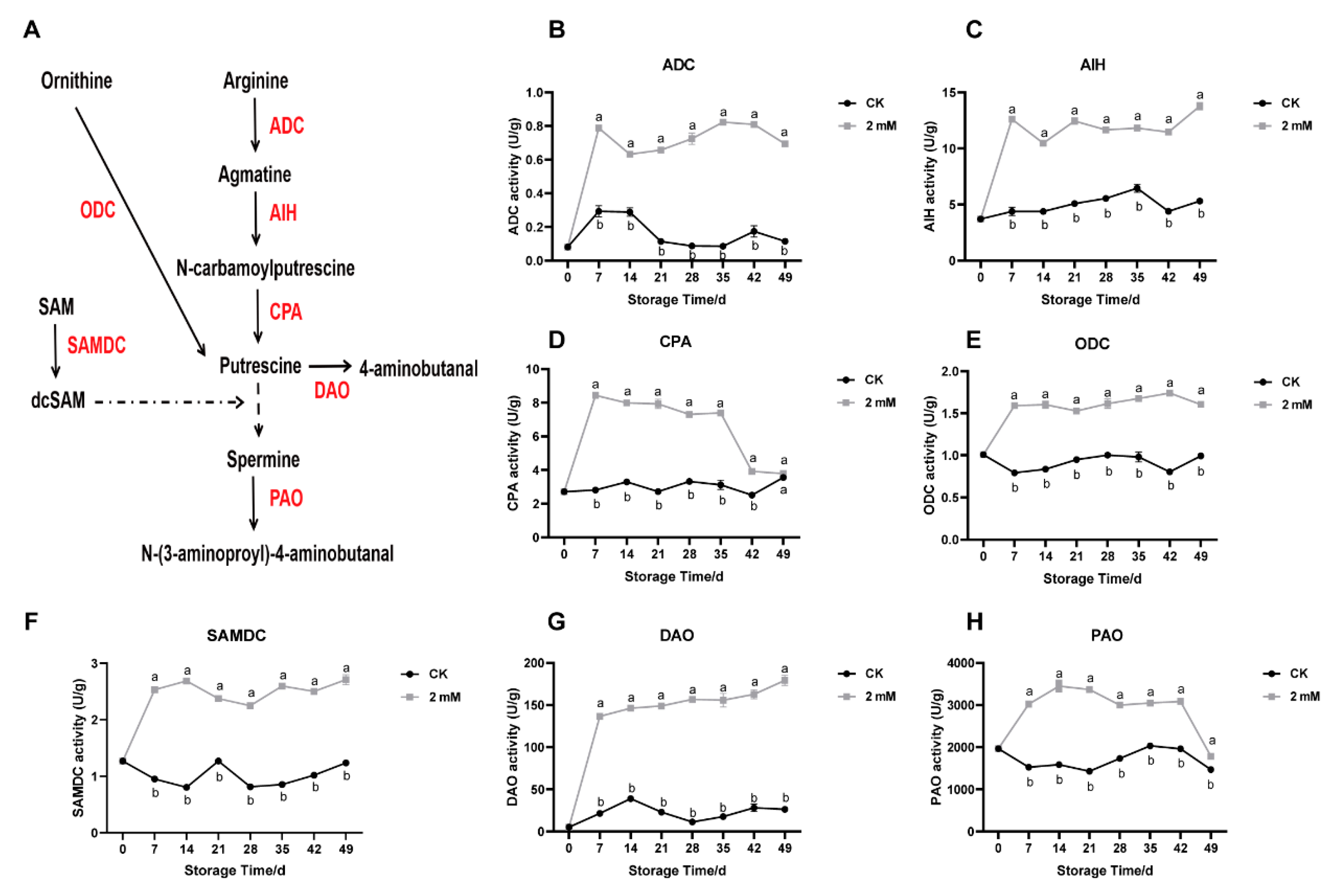

3.3. Polyamine Pathway Enzyme Activity Is Involved in Yellow Melon Fruit During Cold Storage

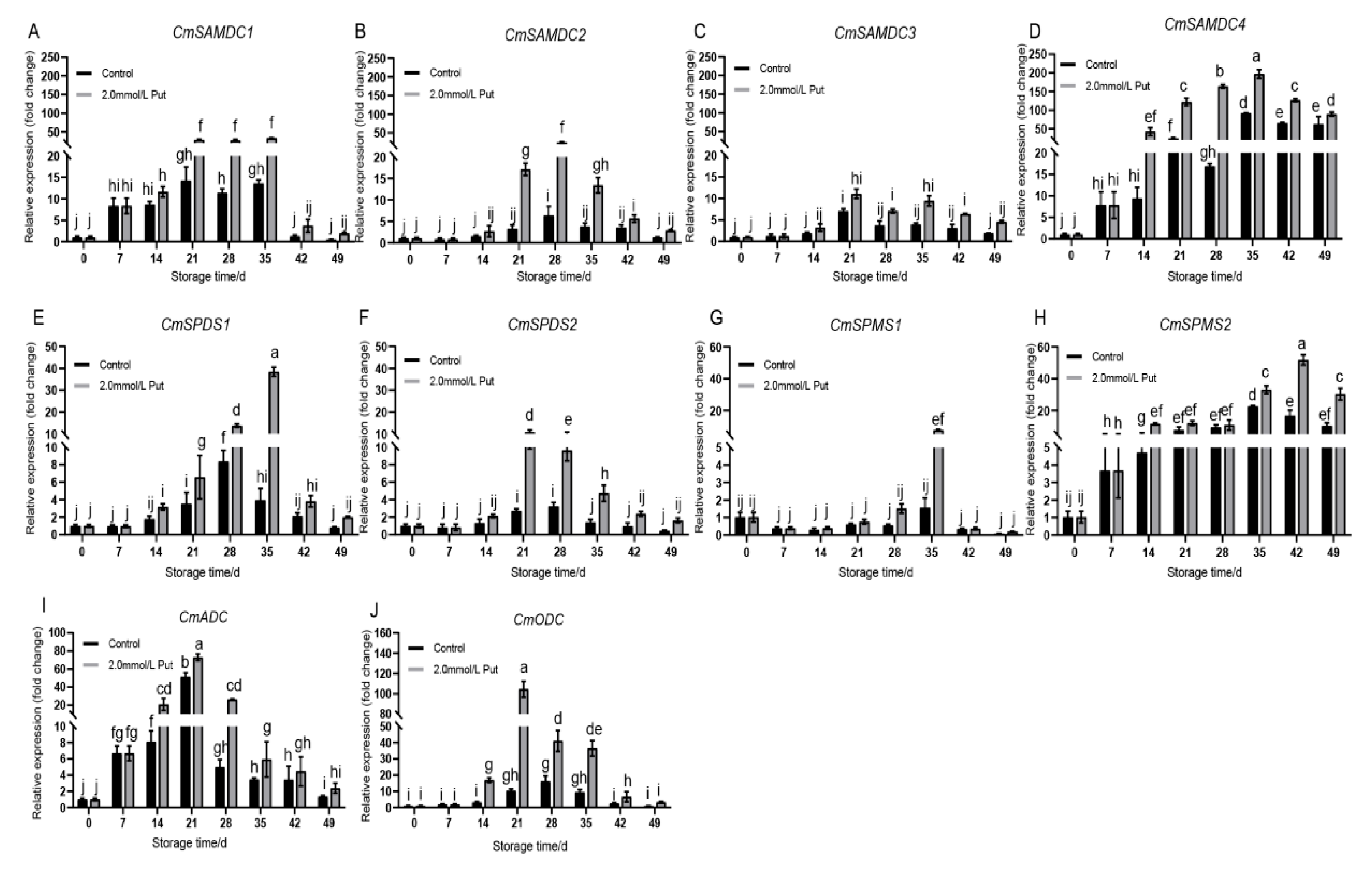

3.4. Put Treatment Induced the Expression of Genes Involved in the Polyamine Pathway

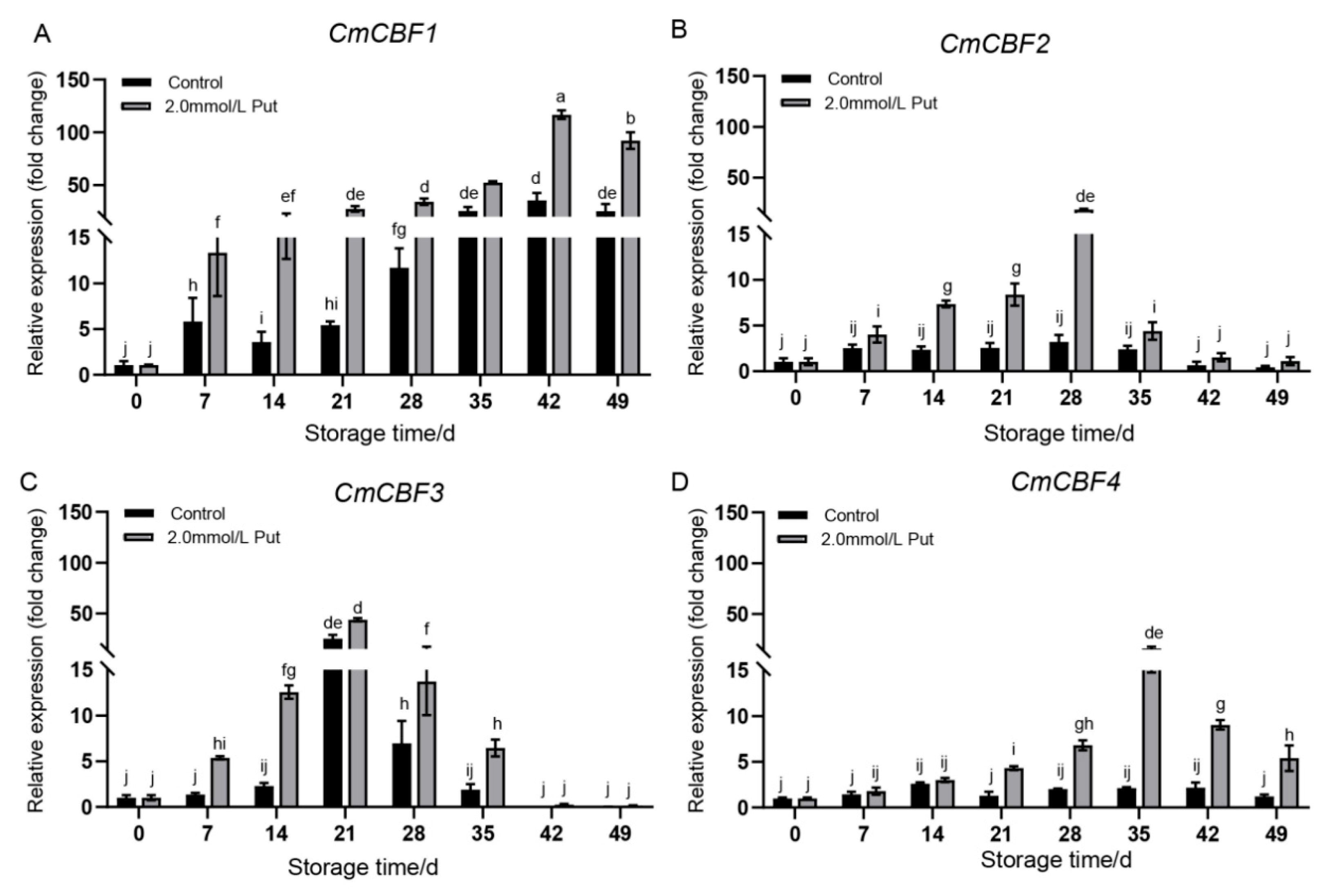

3.5. Expression of CmCBFs in Put-Treated Yellow Melon During Cold Storage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jayakodi, M.; Schreiber, M.; Mascher, M. Sweet genes in melon and watermelon. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1572–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Lv, B.; Feng, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chai, S. Gibberellin biosynthesis is required for CPPU-induced parthenocarpy in melon. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Che, F.; Zhang, H.; Pan, Y.; Xu, M.; Ban, Q.; Han, Y.; Rao, J. Effect of nitric oxide treatment on chilling injury, antioxidant enzymes and expression of the CmCBF1 and CmCBF3 genes in cold-stored Hami melon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 127, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallali, V.; Alhavi, N.; Gholami, H.; Mirazimi Abarghuei, F. Developmental and phytochemical changes in pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) using exogenous application of polyamines. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 183, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.; Gao, R.; Chen, Y.; Pang, J.; Liu, S.; Linghu, T.; Rui, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L. Exogenous putrescine and 1-methylcyclopropene prevent soft scald in ‘Starkrimson’ pear. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 193, 112035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, H.; Banakar, M.H.; Hemmati Hassan Gavyar, P. Polyamines: New Plant Growth Regulators Promoting Salt Stress Tolerance in Plants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 4923–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhi; Iqbal, N.; Khan, N.A. Polyamines Interaction with Gaseous Signaling Molecules for Resilience Against Drought and Heat Stress in Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Liu, D.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Kurtenbach, R. Polyamines conjugated to the bio-membranes and membrane conformations are involved in the melatonin-mediated resistance of harvested plum fruit to cold stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 204, 112480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pál, M.; Szalai, G.; Gondor, O.K.; Janda, T. Unfinished story of polyamines: Role of conjugation, transport and light-related regulation in the polyamine metabolism in plants. Plant Sci. 2021, 308, 110923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Nada, K.; Tachibana, S. Involvement of polyamines in the chilling tolerance of cucumber cultivars. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, J.C.; Lopez-Cobollo, R.; Alcazar, R.; Zarza, X.; Koncz, C.; Altabella, T.; Salinas, J.; Tiburcio, A.F.; Ferrando, A. Putrescine is involved in Arabidopsis freezing tolerance and cold acclimation by regulating abscisic acid levels in response to low temperature. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Huang, Y.; Mei, G.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H.; Zhao, T. Spermidine enhances chilling tolerance of kale seeds by modulating ROS and phytohormone metabolism. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phornvillay, S.; Pongprasert, N.; Wongs-Aree, C.; Uthairatanakij, A.; Srilaong, V. Exogenous putrescine treatment delays chilling injury in okra pod (Abelmoschus esculentus) stored at low storage temperature. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wu, H.; He, F.; Qu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, J.H. Citrus sinensis CBF1 Functions in Cold Tolerance by Modulating Putrescine Biosynthesis through Regulation of Arginine Decarboxylase. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022, 63, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.Q.; Shen, C.; Wu, L.H.; Tang, K.X.; Lin, J. CBF-dependent signaling pathway: A key responder to low temperature stress in plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2011, 31, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yang, S. Molecular Regulation of CBF Signaling in Cold Acclimation. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Song, C.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE2 Negatively Regulates the Stability of Transcription Factor ICE1 in Response to Cold Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2682–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Shen, L.; Fan, B.; Yu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, S.; Sheng, J. Ethylene and cold participate in the regulation of LeCBF1 gene expression in postharvest tomato fruits. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3329–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Qian, X.; Jiang, T.; Zheng, X. Effect of eugenol fumigation treatment on chilling injury and CBF gene expression in eggplant fruit during cold storage. Food Chem. 2019, 292, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, M.; Tang, F.; Chen, J.; Song, W.; Cai, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, X.; Shan, C.; Hao, G. Low-temperature adaptation and preservation revealed by changes in physiological-biochemical characteristics and proteome expression patterns in post-harvest Hami melon during cold storage. Planta 2022, 255, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, Y.; Che, F.; Wang, Q.; Meng, X.; Rao, J. Changes of polyamines and CBFs expressions of two Hami melon (Cucumis melo L.) cultivars during low temperature storage. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 224, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushesh saba, M.; Arzani, K.; Barzegar, M. Postharvest polyamine application alleviates chilling injury and affects apricot storage ability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8947–8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zuo, J.; Gu, S.; Gao, L.; Hu, W.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, A. Putrescine treatment reduces yellowing during senescence of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 152, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Dai, H.; Wang, S.; Ji, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q. Putrescine Treatment Delayed the Softening of Postharvest Blueberry Fruit by Inhibiting the Expression of Cell Wall Metabolism Key Gene VcPG1. Plants 2022, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.U.; Singh, Z. Improved fruit retention, yield and fruit quality in mango with exogenous application of polyamines. Sci. Hortic. 2006, 110, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Pareek, S.; Sagar, N.A.; Valero, D.; Serrano, M. Modulatory Effects of Exogenously Applied Polyamines on Postharvest Physiology, Antioxidant System and Shelf Life of Fruits: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.M.; Maiale, S.J.; Rossi, F.R.; Marina, M.; Ruíz, O.A.; Gárriz, A. Polyamine Metabolism Responses to Biotic and Abiotic Stress. In Polyamines; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, I. Involvement of polyamines in the interacting effects of low temperature and mineral supply on Pringlea antiscorbutica (Kerguelen cabbage) seedlings. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, Q.; Song, Y.; Qi, H. Exogenous spermidine enhances chilling tolerance of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) seedlings via involvement in polyamines metabolism and physiological parameter levels. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, B.; Zheng, L.; Tan, J.; Chen, F. Physiological and transcriptome changes induced by exogenous putrescine in anthurium under chilling stress. Bot. Stud. 2020, 61, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L. Involvement of polyamines in the drought resistance of rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, Q.; Song, Y.; Shi, D.; Qi, H. Interaction of Polyamines, Abscisic Acid, Nitric Oxide, and Hydrogen Peroxide under Chilling Stress in Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahanger, M.A.; Qin, C.; Maodong, Q.; Dong, X.X.; Ahmad, P.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Zhang, L. Spermine application alleviates salinity induced growth and photosynthetic inhibition in Solanum lycopersicum by modulating osmolyte and secondary metabolite accumulation and differentially regulating antioxidant metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 144, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeed, H.T.; Hassan, N.M.; Aljarani, A.M. Exogenous applications of Polyamines modulate drought responses in wheat through osmolytes accumulation, increasing free polyamine levels and regulation of polyamine biosynthetic genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 118, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Han, J.; Dong, Z.; Pan, R.; Guan, Y.; Alhaj Hamoud, Y.; Hu, J. Polyamine biosynthetic pathways and their relation with the cold tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1807722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamipour, N.; Khosh-Khui, M.; Salehi, H.; Razi, H.; Karami, A.; Moghadam, A. Role of genes and metabolites involved in polyamines synthesis pathways and nitric oxide synthase in stomatal closure on Rosa damascena Mill. under drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, S.; Maali-Amiri, R.; Kazemi-Shahandashti, S.-S.; López-Gómez, M.; Sadeghzadeh, B.; Sobhani-Najafabadi, A.; Kariman, K. Effect of cold stress on polyamine metabolism and antioxidant responses in chickpea. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 258–259, 153387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, M.; Yu, G.; Wang, D.; Xu, Z.; Liang, L.; Xiao, J.; Xie, Y.; Tang, Y.; Sun, G.; et al. CaSPDS, a Spermidine Synthase Gene from Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), Plays an Important Role in Response to Cold Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, F.; Mirzaghaderi, G.; Marashi, S.H.; Janda, T. Polyamines-Mediated amelioration of cold treatment in wheat: Insights from morpho-physiological and biochemical features and PAO genes expression analyses. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.T.; Zarka, D.G.; Van Buskirk, H.A.; Fowler, S.G.; Thomashow, M.F. Roles of the CBF2 and ZAT12 transcription factors in configuring the low temperature transcriptome of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004, 41, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Z.; Yang, S. The cbfs triple mutants reveal the essential functions of CBFs in cold acclimation and allow the definition of CBF regulons in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvallo, M.A.; Pino, M.T.; Jeknic, Z.; Zou, C.; Doherty, C.J.; Shiu, S.H.; Chen, T.H.; Thomashow, M.F. A comparison of the low temperature transcriptomes and CBF regulons of three plant species that differ in freezing tolerance: Solanum commersonii, Solanum tuberosum, and Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3807–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yue, C.; Yang, J.; Ye, N. Identification of CBF Transcription Factors in Tea Plants and a Survey of Potential CBF Target Genes under Low Temperature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, S.; Si, T.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Mutational Evidence for the Critical Role of CBF Transcription Factors in Cold Acclimation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2744–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Duan, X.; Gao, G.; Liu, T.; Qi, H. CmABF1 and CmCBF4 cooperatively regulate putrescine synthesis to improve cold tolerance of melon seedlings. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, S.; Che, H.; Djillali, Z.; Dumont, E.; Nankeu, J.; Danyluk, J.; Gulick, P. Wheat CBF gene family: Identification of polymorphisms in the CBF coding sequence. Genome 2012, 55, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Gene ID | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| QCBF1F | MELO3C006869 | CAGAGATATCCAGAAGGCGG |

| QCBF1R | MELO3C006869 | TATCCTCCAACAATCCAGGC |

| QCBF2F | MELO3C005367 | CTCATGATGTTGCTGCCATC |

| QCBF2R | MELO3C005367 | AGTACTCATGATCATCCGGC |

| QCBF3F | MELO3C009442 | CCCGATTTACAAAGGCGTTC |

| QCBF3R | MELO3C009442 | GTGGAAATGAGTGAGCGAAG |

| QCBF4F | MELO3C005629 | AGACATCCGGTTTACAGAGG |

| QCBF4R | MELO3C005629 | TTCCCTCTTAACGCTAGTGC |

| QCmADCF | MELO3C023359 | GATCCCCTCTACTGCTTTGC |

| QCmADCR | MELO3C023359 | GCAGCATACTCTTCGAGTCC |

| QCmODCF | MELO3C011335 | GGAAGTGGGGCTACTGAAAC |

| QCmODCR | MELO3C011335 | TTATGGCCGACTTTACTGCC |

| QCmSAMDC1F | MELO3C023787 | GAGAAGAAGACTCATCGGCG |

| QCmSAMDC1R | MELO3C023787 | CATCCTCTGGAGTAACGTGC |

| QCmSAMDC2F | MELO3C021386 | CATCAAGCTCGAAGTCTCGG |

| QCmSAMDC2R | MELO3C021386 | GAGGCTTTCCGGTAATGGAG |

| QCmSAMDC3F | MELO3C006580 | CTCTGAGGAAGTTGCTGTCC |

| QCmSAMDC3R | MELO3C006580 | TTCCAGGGTATAAACGGGGT |

| QCmSAMDC4F | MELO3C004110 | TCCATGAATGGAATCGACGG |

| QCmSAMDC4R | MELO3C004110 | GGTCGATACCGACACTTTCC |

| QCmSPDS1F | MELO3C012007 | TTTGAGTTCTGTTCCACCAGG |

| QCmSPDS1R | MELO3C012007 | GGAAACCAAAGGCTTTCTGC |

| QCmSPDS2F | MELO3C017103 | GCGTAGCTATTGGGTACGAG |

| QCmSPDS2R | MELO3C017103 | CATACAACACCTCCTGGTCG |

| QCmSPMS1F | MELO3C005877 | CACAAGAGCTGGTGGAGATG |

| QCmSPMS1R | MELO3C005877 | TGGATATGTTGGAACGCTGG |

| QCmSPMS2F | MELO3C008477 | CTGGTGGTGTCCTCTGTAAC |

| QCmSPMS2R | MELO3C008477 | AACAGGTTTCCCTTCGGTTG |

| EF1aF | MELO3C020441 | AAATACTCCAAGGCAAGGTAC |

| EF1aR | MELO3C020441 | TCATGTTGTCACCCTCGAAACCAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Kelimujiang, K.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yue, H.; Zheng, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, C. Exogenous Putrescine Application Mitigates Chill Injury in Melon Fruit During Cold Storage by Regulating Polyamine Metabolism and CBF Gene Expression. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010063

Li X, Kelimujiang K, Zhao Z, Zhang J, Yue H, Zheng P, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Chen C. Exogenous Putrescine Application Mitigates Chill Injury in Melon Fruit During Cold Storage by Regulating Polyamine Metabolism and CBF Gene Expression. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaoxue, Kelaremu Kelimujiang, Zhixia Zhao, Jian Zhang, Hong Yue, Pufan Zheng, Yinxing Zhang, Ting Zhang, and Cunkun Chen. 2026. "Exogenous Putrescine Application Mitigates Chill Injury in Melon Fruit During Cold Storage by Regulating Polyamine Metabolism and CBF Gene Expression" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010063

APA StyleLi, X., Kelimujiang, K., Zhao, Z., Zhang, J., Yue, H., Zheng, P., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., & Chen, C. (2026). Exogenous Putrescine Application Mitigates Chill Injury in Melon Fruit During Cold Storage by Regulating Polyamine Metabolism and CBF Gene Expression. Horticulturae, 12(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010063