The CsBT1 Gene from Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Negatively Regulates Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.3. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of CsBT1

2.4. Vector Construction and Generation of Transgenic Arabidopsis Lines

2.5. Various Abiotic Stresses in Arabidopsis Plants

2.6. Histochemical Staining and Determination of Physiological Indexes

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sequence Analysis of CsBT1 and Its Deduced Amino Acid Sequences

3.2. Expression Analysis of CsBT1 in Cucumber

3.3. Obtaining of Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing CsBT1

3.4. Overexpression of CsBT1 Decreased the Salt Stress Tolerance of Transgenic Arabidopsis

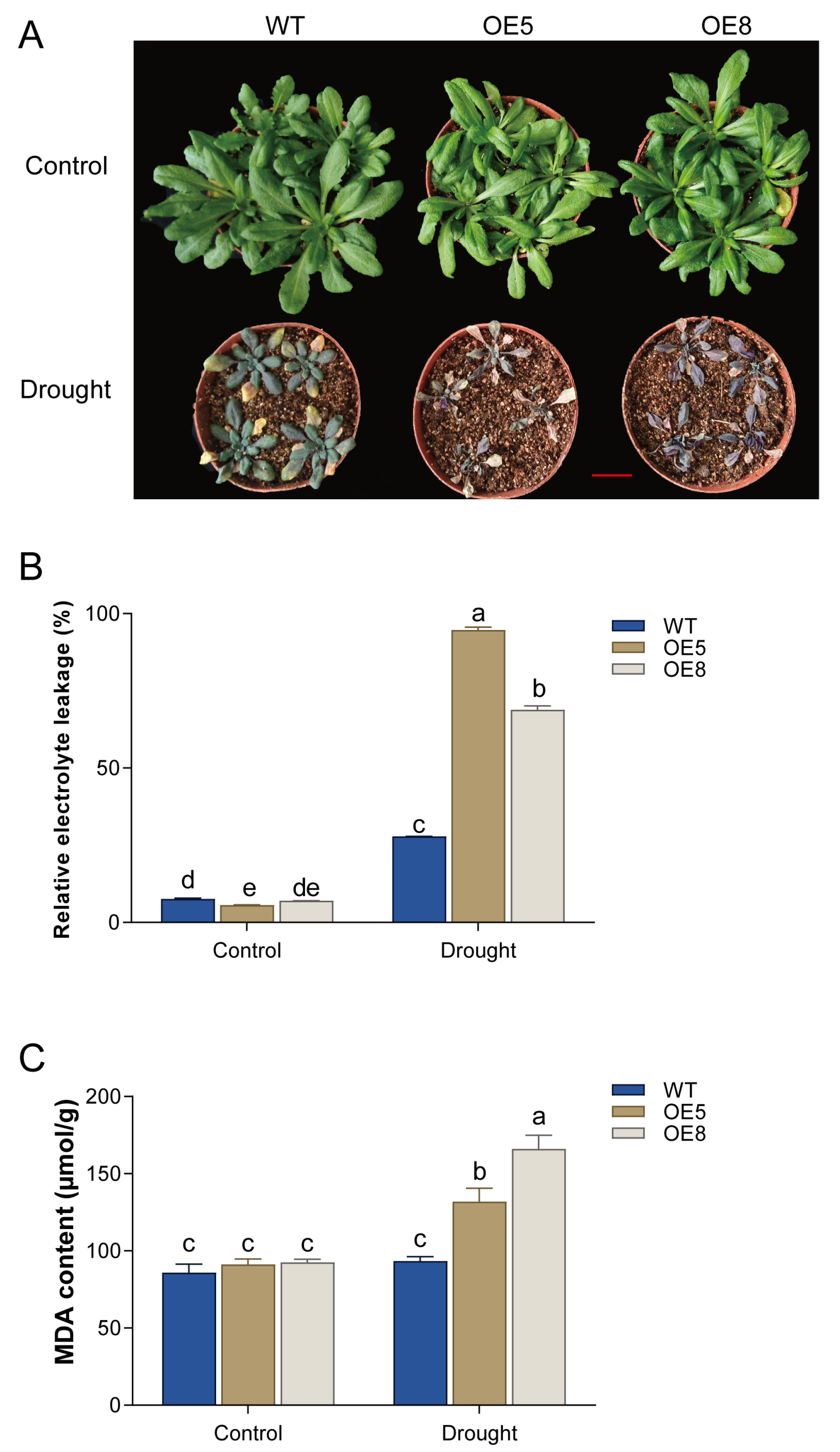

3.5. Analysis of Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing CsBT1

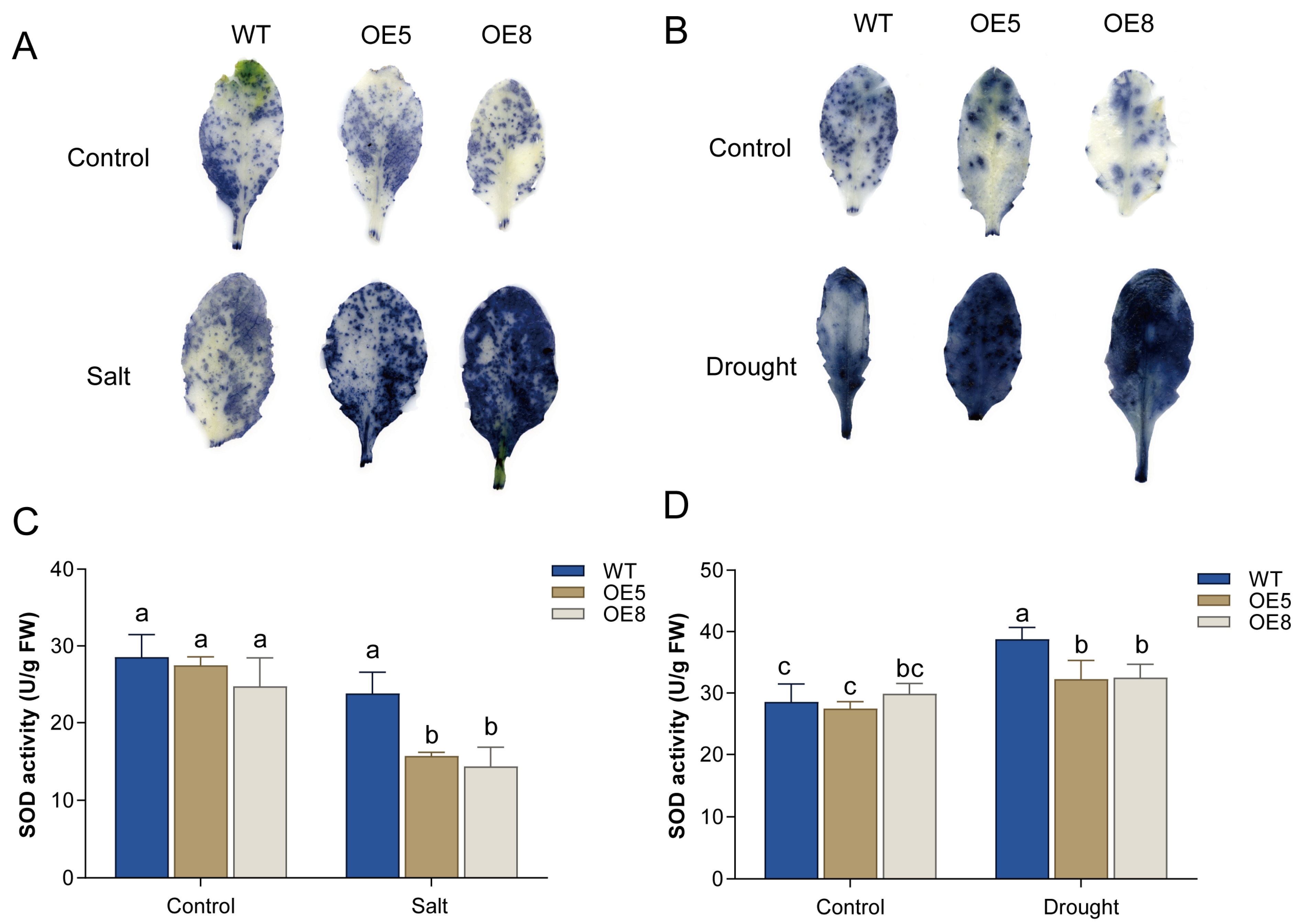

3.6. Overexpression of CsBT1 in Arabidopsis Increased ROS Accumulation Under Salt and Drought Stress

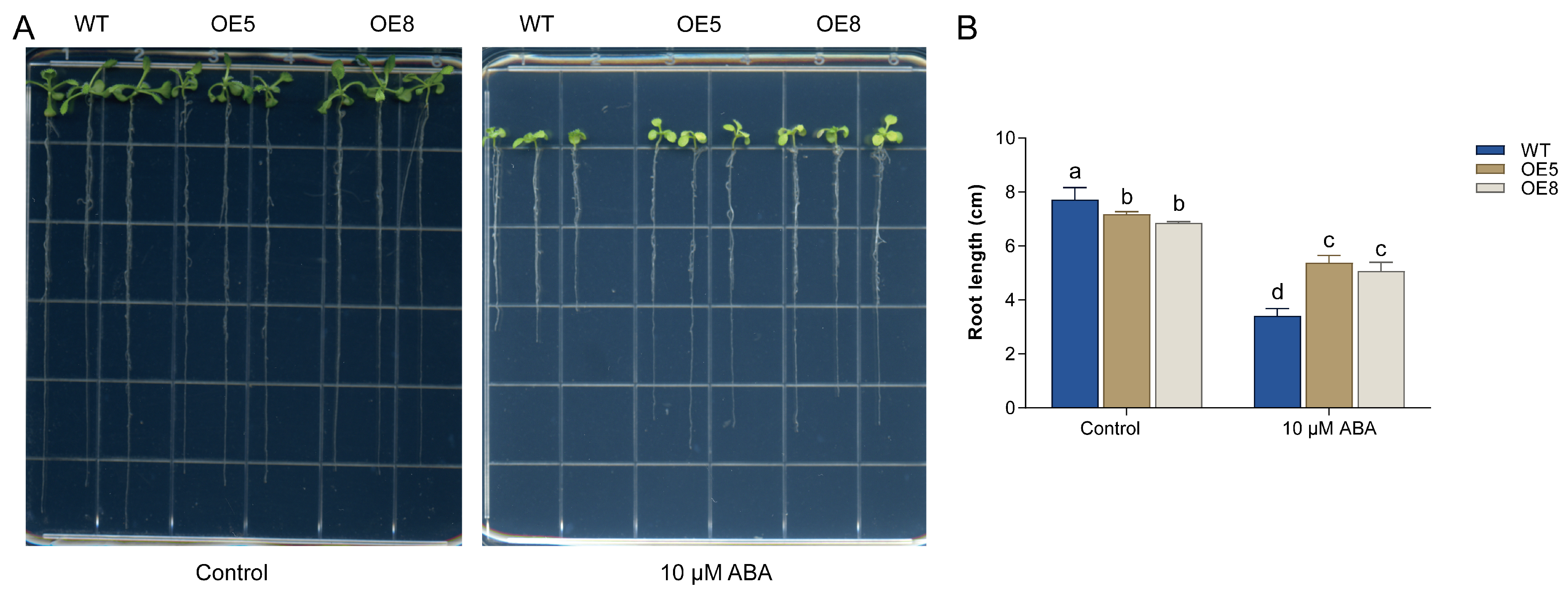

3.7. Overexpression of CsBT1 in Arabidopsis Increased Resistant to ABA Treatment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, L.; Ye, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, S. Genome-wide identification of glutathione peroxidase (GPX) gene family and their response to abiotic stress in cucumber. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Characterization of germin-like proteins (GLPs) and their expression in response to abiotic and biotic stresses in cucumber. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Nezames, C.D.; Sheng, L.; Deng, X.; Wei, N. Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase family in plant abiotic stress pathways(F). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Dai, X.; Li, Q.; Wei, M. Genome-wide characterization of the BTB gene family in poplar and expression analysis in response to hormones and biotic/abiotic stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsanosi, H.A.; Zhang, J.; Mostafa, S.; Geng, X.; Zhou, G.; Awdelseid, A.H.M.; Song, L. Genome-wide identification, structural and gene expression analysis of BTB gene family in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonchuk, A.; Balagurov, K.; Georgiev, P. BTB domains: A structural view of evolution, multimerization, and protein-protein interactions. Bioessays 2023, 45, e2200179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Mandadi, K.K.; Boedeker, A.L.; Rathore, K.S.; McKnight, T.D. Regulation of telomerase in Arabidopsis by BT2, an apparent target of TELOMERASE ACTIVATOR1. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Ma, W.; He, R.; Cao, H.; Xing, J.; Zhang, K.; Dong, J. Function of ZmBT2a gene in resistance to pathogen infection in maize. Phytopathol. Res. 2024, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Hu, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, S. Comprehensive genomic analysis and expression profiling of the BTB and TAZ (BT) genes in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed 2020, 56, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xie, Y.H.; Sun, P.; Zhang, F.J.; Zheng, P.F.; Wang, X.F.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. Nitrate-inducible MdBT2 acts as a restriction factor to limit apple necrotic mosaic virus genome replication in Malus domestica. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qi, C.H.; Gao, H.N.; Feng, Z.Q.; Wu, Y.T.; Xu, X.X.; Cui, J.Y.; Wang, X.F.; Lv, Y.H.; Gao, W.S.; et al. MdBT2 regulates nitrogen-mediated cuticular wax biosynthesis via a MdMYB106-MdCER2L1 signalling pathway in apple. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gingerich, D.J.; Hanada, K.; Shiu, S.H.; Vierstra, R.D. Large-scale, lineage-specific expansion of a bric-a-brac/tramtrack/broad complex ubiquitin-ligase gene family in rice. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2329–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Pan, Y.; Su, C.; Zhang, X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the BTB domain-containing protein gene family in tomato. Genes Genom. 2018, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Wen, B.; Li, S.; Xu, C.; Gai, Y.; Meng, X.; He, H.; Wang, N.; Li, D.; et al. BTB-TAZ domain protein PpBT3 modulates peach bud endodormancy by interacting with PpDAM5. Plant Sci. 2021, 310, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.D.; Guan, Z.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhu, H.D.; Sun, Q.; Hu, D.G.; Sun, C.H. The BTB/TAZ domain-containing protein CmBT1-mediated CmANR1 ubiquitination negatively regulates root development in chrysanthemum. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, H.S.; Quint, A.; Brand, D.; Vivian-Smith, A.; Offringa, R. BTB and TAZ domain scaffold proteins perform a crucial function in Arabidopsis development. Plant J. 2009, 58, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen, S.; Ramasamy, M.; Misra, A.; McKnight, T.D.; Mandadi, K.K. A BTB-TAZ protein is required for gene activation by Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S multimerized enhancers. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xing, J.; Zhang, K.; Pang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G.; Zang, J.; Huang, R.; Dong, J. Ethylene response factor ERF11 activates BT4 transcription to regulate immunity to Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1132–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.L.; Li, H.L.; Qiao, Z.W.; Zhang, J.C.; Sun, W.J.; Wang, C.K.; Yang, K.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. The BTB-TAZ protein MdBT2 negatively regulates the drought stress response by interacting with the transcription factor MdNAC143 in apple. Plant Sci. 2020, 301, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Ma, C.N.; Gu, K.D.; Wang, J.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; He, J.X.; Hu, D.G.; Sun, Q. The BTB-BACK-TAZ domain protein MdBT2 reduces drought resistance by weakening the positive regulatory effect of MdHDZ27 on apple drought tolerance via ubiquitination. Plant J. 2024, 119, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ren, Y.R.; Wang, Q.J.; Wang, X.F.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. Ubiquitination-related MdBT scaffold proteins target a bHLH transcription factor for iron homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Gu, K.D.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J.H.; Yu, J.Q.; Wang, X.F.; You, C.X.; Hu, D.G.; Hao, Y.J. BTB-TAZ domain protein MdBT2 modulates malate accumulation and vacuolar acidification in response to nitrate. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.R.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Y.Y.; Zhang, T.E.; Wang, X.F.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. The apple 14-3-3 protein MdGRF11 interacts with the BTB protein MdBT2 to regulate nitrate deficiency-induced anthocyanin accumulation. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Zhang, F.; Song, S.; Yu, X.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; He, H. CsSWEET2, a hexose transporter from cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), affects sugar metabolism and improves cold tolerance in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Liu, P.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, C.; Pang, H.; Zhang, Y. CsWRKY46 is involved in the regulation of cucumber salt stress by regulating abscisic acid and modulating cellular reactive oxygen species. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Shi, B.; Miao, M.; Zhao, C.; Bai, R.; Yan, F.; Lei, C. A B-Box (BBX) transcription factor from cucumber, CsCOL9 positively regulates resistance of host plant to Bemisia tabaci. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Xia, H.; Zhao, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, M.; Lin, Z.; Mao, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Overexpression of cucumber CsVQ12 gene modulates MeJA-mediated freezing tolerance and leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2025, 163, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Yan, X.; Wu-Zhang, K.; Qin, W.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, B.; et al. A high-efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system in the leaves of Artemisia annua L. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hu, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, S. Molecular cloning and characterization of an ASR gene from Cucumis sativus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017, 130, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Guo, J.; Dong, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, Q.; Cao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chen, C.; Jin, X. UDP-glycosyltransferase gene SlUGT73C1 from Solanum lycopersicum regulates salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Peng, L.; Wang, A.; Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. An R2R3-MYB FtMYB11 from Tartary buckwheat has contrasting effects on abiotic tolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 280, 153842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, L.; Jian, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C.-Z. Heterologous expression of MfWRKY7 of resurrection plant Myrothamnus flabellifolia enhances salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, X.; Luo, C.; Xia, L.M.; Mo, W.J.; Zhu, J.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Hu, W.L.; Liu, Y.; Xie, F.F.; He, X.H. Overexpression of mango MiSVP3 and MiSVP4 delays flowering time in transgenic Arabidopsis. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 317, 112021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Yao, A.; Niu, C.; Hou, R.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, D. Overexpression of Malus baccata WRKY40 (MbWRKY40) enhances stress tolerance in Arabidopsis subjected to cold and drought. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.T.; Hou, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J.M.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Wang, D.M.; Xu, Z.S.; Song, X.; et al. Foxtail millet SiCDPK7 gene enhances tolerance to extreme temperature stress in transgenic plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 207, 105197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Hu, D.; Gao, J.; Sun, C. Scaffold protein BTB/TAZ domain-containing genes (CmBTs) play a negative role in root development of chrysanthemum. Plant Sci. 2024, 341, 111997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yan, Z.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Mu, C.; Yao, G.; Leng, B. Overexpression of maize expansin gene ZmEXPA6 improves salt tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Yan, X.; Zenda, T.; Wang, N.; Dong, A.; Yang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Xing, Y.; Duan, H. Overexpression of the peroxidase gene ZmPRX1 increases maize seedling drought tolerance by promoting root development and lignification. Crop J. 2024, 12, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Q.; Du, L.Y.; Ma, W.; Niu, R.Y.; Wu, B.W.; Guo, L.J.; Ma, M.; Liu, X.L.; Zhao, H.X. The miR164-TaNAC14 module regulates root development and abiotic-stress tolerance in wheat seedlings. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.L.; Li, H.L.; Qiao, Z.W.; Zhang, J.C.; Sun, W.J.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J.; Wang, X.F. The BTB protein MdBT2 recruits auxin signaling components to regulate adventitious root formation in apple. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, D.; Yi, R.; Ma, Y.; Dong, Q.; Mao, K.; Ma, F. Apple WRKY transcription factor MdWRKY56 positively modulates drought stress tolerance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 212, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, P.; Chen, H.; Zhong, J.; Liang, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Han, D. Overexpression of a Fragaria vesca 1R-MYB transcription factor gene (FvMYB114) increases salt and cold tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y. The CsBT1 Gene from Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Negatively Regulates Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010062

Huang W, Wang M, Zhou Z, Guo X, Hu Z, Zhou Y, Liu S, Zhou Y. The CsBT1 Gene from Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Negatively Regulates Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Weifeng, Meng Wang, Zuying Zhou, Xueping Guo, Zhaoyang Hu, Yuelong Zhou, Shiqiang Liu, and Yong Zhou. 2026. "The CsBT1 Gene from Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Negatively Regulates Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010062

APA StyleHuang, W., Wang, M., Zhou, Z., Guo, X., Hu, Z., Zhou, Y., Liu, S., & Zhou, Y. (2026). The CsBT1 Gene from Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Negatively Regulates Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants. Horticulturae, 12(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010062