Photosynthetic Performance and Gene Expression in Passiflora edulis Under Heat Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Determination of Chlorophyll Content in P. edulis Leaves

2.3. Determination of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

2.4. Determination of Photosynthetic Characteristics

2.5. RNA Extraction, Library Construction and Sequencing

2.6. Bioinformatics Analyses

2.7. Functional Enrichment Analyses

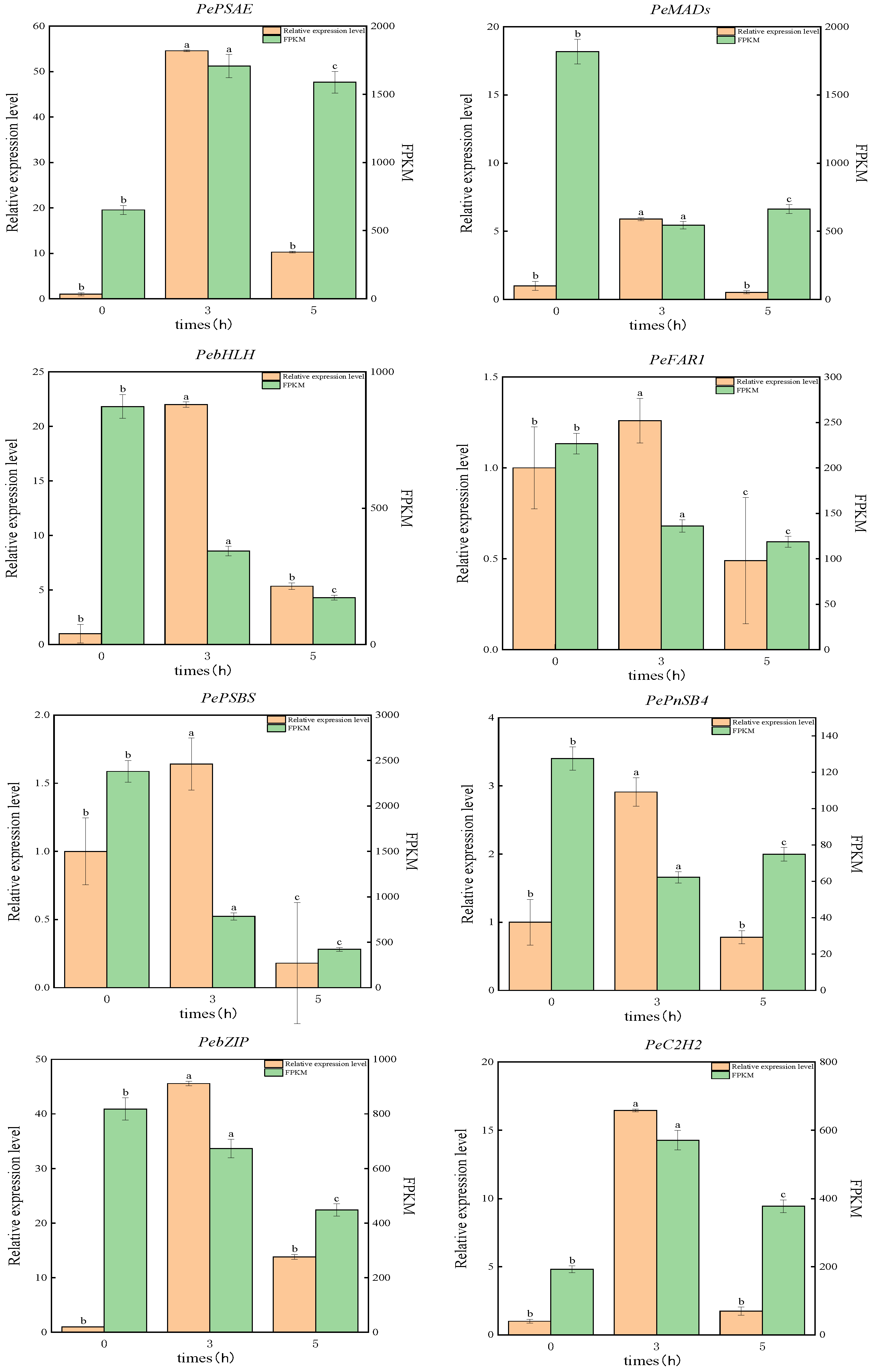

2.8. Screening of Genes Related to Photosynthesis and qRT-PCR Detection

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of High-Temperature Stress on Chlorophyll Content of P. Edulis

3.2. Effects of High-Temperature Stress on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters of P. edulis Leaves

3.3. Effects of High-Temperature Stress on Photosynthetic Characteristics of P. edulis Leaves

3.4. Characterization of the Heat-Treated P. edulis Transcriptome

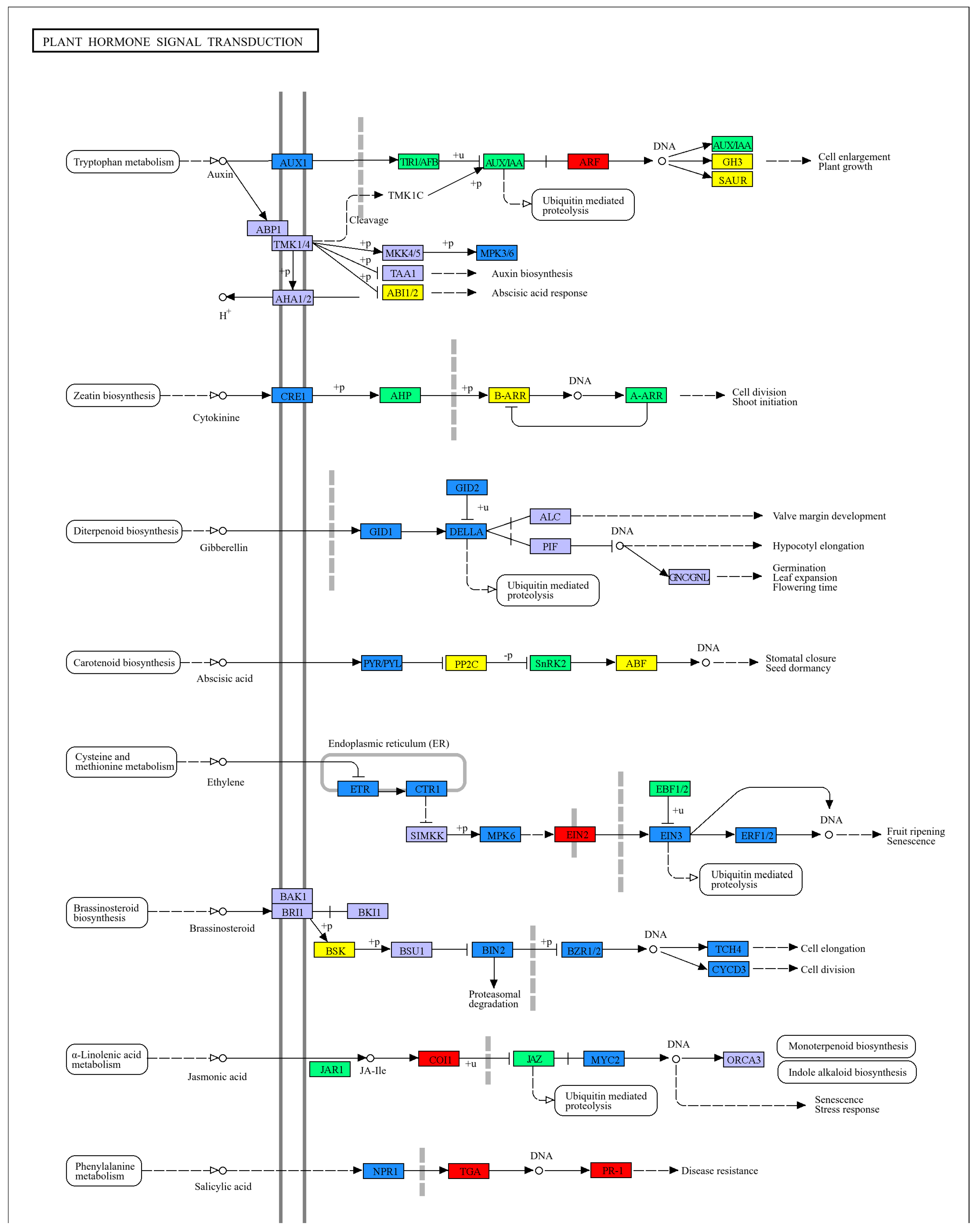

3.5. Differential Expression of Photosynthetic Related Genes in P. edulis Under High Temperature

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Tao, S.; Hou, G.; Zhao, F.; Meng, Q.; Tan, S. Phytochemistry, nutritional composition, health benefits and future prospects of Passiflora: A review. Food Chem. 2023, 428, 136825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S.G.; Vijayanand, P. Effect of extraction conditions on the quality characteristics of pectin from passion fruit peel (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa L.). LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Luan, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Fang, J.; Wang, M.; Zuo, M.; Li, Y. Passiflora edulis: An Insight Into Current Researches on Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Ali, M.M.; He, Y.; Ma, S.; Rizwan, H.M.; Yang, Q.; Li, B.; Lin, Z.; Chen, F. Flavonoids Accumulation in Fruit Peel and Expression Profiling of Related Genes in Purple (Passiflora edulis f. edulis) and Yellow (Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa) Passion Fruits. Plants 2021, 10, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, R.C.G.; Peralta, R.M.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Maciel, G.M.; Bracht, A.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. The past decade findings related with nutritional composition, bioactive molecules and biotechnological applications of Passiflora spp. (passion fruit). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 58, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, A.; Teng, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xu, M. Exploring the adaptive mechanism of Passiflora edulis in karst areas via an integrative analysis of nutrient elements and transcriptional profiles. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Hussain, M.D.; Hu, K.; Kamran, A.; Luo, L.; Yang, S.; Xie, X. First report of Gulupa baciliform virus A associated with passion fruit in China. Plant Dis. 2025, 109, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fang, Y.; An, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Aslam, M.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bHLH gene family in passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) and its response to abiotic stress. Int. J. Biol. 2023, 225, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, A.; Chen, C.; Cai, G.; Zhang, L.; Guo, C.; Xu, M. De Novo Transcriptome Sequencing in Passiflora edulis Sims to Identify Genes and Signaling Pathways Involved in Cold Tolerance. Forests 2017, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, S.; Chayut, N.; Nave, N.; Kafle, D.; Hegele, M.; Kaminetsky, R.; Wünsche, J.N.; Samach, A. Genetic variation in yield under hot ambient temperatures spotlights a role for cytokinin in protection of developing floral primordia. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 37, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, D.R.; Meehl, G.A.; Parmesan, C.; Changnon, S.A.; Karl, T.R.; Mearns, L.O. Climate Extremes: Observations, Modeling, and Impacts. Science 2020, 289, 2068–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khatib, K.; Paulsen, G.M. High-Temperature Effects on Photosynthetic Processes in Temperate and Tropical Cereals. Crop Sci. 1999, 39, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbot, V. How plants cope with temperature stress. BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.; Bjorkman, O. Photosynthetic Response and Adaptation to Temperature in Higher Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1980, 31, 491–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvucci, M.E.; Crafts-Brandner, S.J. Inhibition of photosynthesis by heat stress: The activation state of Rubisco as a limiting factor in photosynthesis. Physiol. Plant 2004, 120, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Fujita, M. Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms of Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9643–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, R.A.; Ort, D.R. Carbon assimilation in crops at high temperatures. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 2750–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Praat, M.; Pizzio, G.A.; Jiang, Z.; Driever, S.M.; Wang, R.; Van De Cotte, B.; Villers, S.L.Y.; Gevaert, K.; et al. Stomatal opening under high temperatures is controlled by the OST1-regulated TOT3–AHA1 module. Nat. Plants 2024, 11, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A.Y. Generation and Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species in Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11302–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Kreslavski, V.D.; Klimov, V.V.; Los, D.A.; Carpentier, R.; Mohanty, P. Heat stress: An overview of molecular responses in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 2008, 98, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, D.; Shekhar, S.; Agrawal, L.; Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, N. Cultivar-specific high temperature stress responses in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) associated with physicochemical traits and defense pathways. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inbal Neta-Sharir Tal, I.; Susan, L.; David, M. Dual Role for Tomato Heat Shock Protein 21: Protecting Photosystem II from Oxidative Stress and Promoting Color Changes during Fruit Maturation. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1829–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, M.; Matsuda, H. Soilless cultivation of ‘Ruby Star’ passion fruit: Effects of NO3-N application, pH, and temperature on fruit quality. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 306, 111462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Jiang, H.; Lv, Y.; Hu, S.; Sheng, Z.; Shao, G.; Tang, S.; Hu, P.; Wei, X. Chlorophyll deficient 3, Encoding a Putative Potassium Efflux Antiporter, Affects Chloroplast Development Under High Temperature Conditions in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018, 36, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesch, R.W.; Kang, I.H.; Gallo-Meagher, M.; Vu, J.C.V.; Boote, K.J.; Allen, L.H.; Bowes, G. Rubisco expression in rice leaves is related to genotypic variation of photosynthesis under elevated growth CO2 and temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, M.S.; Shi, Z.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, R.; El-Mogy, M.; Sun, J.; Shu, S.; Guo, S.; Wang, Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals gene network regulation of TGase-induced thermotolerance in tomato. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 12208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, H.; Takaragawa, H. Leaf Photosynthetic Reduction at High Temperatures in Various Genotypes of Passion Fruit (Passiflora spp.). Hortic. J. 2023, 92, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, A.; Kubo, T.; Tominaga, S.; Masashi, Y. Effect of Temperature on Photosynthesis Characteristics in the Passion Fruits ‘Summer Queen’ and ‘Ruby Star’. Hortic. J. 2017, 86, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Lai, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, W.; Li, Y.; Tu, H.; Ling, Q.; Fu, X. Differential gene expression analysis and physiological response characteristics of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) buds under high-temperature stress. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Chen, J.; Wei, X.; Hu, S.; Lu, L.; Chen, S.; Yao, Q.; Xie, S.; et al. Identification and characterization of GRAS genes in passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) revealed their roles in development regulation and stress response. Plant Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xing, W.; Wu, B.; Huang, D.; Ma, F.; Zhan, R.; Sun, P.; Xu, Y.; Song, S. Identification of the passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims) MYB family in fruit development and abiotic stress, and functional analysis of PeMYB87 in abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1124351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Tian, Q.; Huang, W.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Yang, X.; Mou, H. Identification and evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in Passiflora edulis under stem rot condition. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2951–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potters, G.; Pasternak, T.P.; Guisez, Y.; Jansen, M.A.K. Different stresses, similar morphogenic responses: Integrating a plethora of pathways. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smertenko, A.; Dráber, P.; Viklický, V.; Opatrny, Z. Heat stress affects the organization of microtubules and cell division in Nicotiana tabacum cells. Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, C.J.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Safeguarding crop photosynthesis in a rapidly warming world. Science 2025, 388, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didaran, F.; Kordrostami, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Pashkovskiy, P.; Kreslavski, V.; Kuznetsov, V.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. The mechanisms of photoinhibition and repair in plants under high light conditions and interplay with abiotic stressors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2024, 259, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, C. Sensitivity and Responses of Chloroplasts to Heat Stress in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Kong, F.; Chi, Z. The interplay between Ca2+ and ROS in regulating β-carotene biosynthesis in Dunaliella salina under high temperature stress. Algal Res. 2025, 88, 104023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafts-Brandner, S.J.; Salvucci, M.E. Rubisco activase constrains the photosynthetic potential of leaves at high temperature and CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13430–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez, C.; Capó-Bauçà, S.; Niinemets, Ü.; Stoll, H.; Aguiló-Nicolau, P.; Galmés, J. Evolutionary trends in RuBisCO kinetics and their co-evolution with CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Plant J. 2019, 101, 897–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.W.; Wang, G.Z.; Dou, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; He, Y.; Tang, Z.; Yu, J. Protective mechanisms of exogenous melatonin on chlorophyll metabolism and photosynthesis in tomato seedlings under heat stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1519950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, W.; Hong, E.M.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Lin, B.; Xia, X.; Li, T.; Song, X.; Jin, S.; Zhu, X. Photosynthetic and physiological responses of different peony cultivars to high temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 969718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monneveux, P.; Rekika, D.; Acevedo, E.; Merah, O. Effect of drought on leaf gas exchange, carbon isotope discrimination, transpiration efficiency and productivity in field grown durum wheat genotypes. Plant Sci. 2006, 170, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Gu, X.; Li, J.; Guo, J.; Lu, D. Leaf photosynthetic characteristics of waxy maize in response to different degrees of heat stress during grain filling. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Sehar, Z.; Fatma, M.; Umar, S.; Sofo, A.; Khan, N.A. Nitric Oxide and Abscisic Acid Mediate Heat Stress Tolerance through Regulation of Osmolytes and Antioxidants to Protect Photosynthesis and Growth in Wheat Plants. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Luo, W.; Niu, S.; Qu, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Yang, H.; Lu, D. Salicylic Acid Cooperates With Lignin and Sucrose Signals to Alleviate Waxy Maize Leaf Senescence Under Heat Stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4341–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Lin, Y.; Gan, Y.; Yang, C.; Liang, Y.; Qin, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, R.; Zhao, H.; Qiu, Z.; et al. Auxin promotes cucumber resistance to high ambient temperature by enhancing photosystem and activating DNA repair pathways. Hortic. Plant J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, H.; Yu, Y.; Mu, K.; Kang, Y. Research Progress on Responses and Regulatory Mechanisms of Plants Under High Temperature. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Dong, J.; Zhang, T.; Cao, H.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fu, A.; et al. Dimerization of immunophilin CYN38 regulates Photosystem II repair in Chlamydomonas. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5637–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.; Dong, B.; Chen, Z.; Hong, L.; Zhang, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, H.-B.; Jin, H.-L. HHL1 and SOQ1 synergistically regulate non—Photochemical quenching in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanjean, R.; Latifi, A.; Matthijs, H.C.P.; Havaux, M. The PsaE subunit of photosystem I prevents light-induced formation of reduced oxygen species in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 2008, 1777, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviv-Sharon, E.; Sultan, L.D.; Naveh, L.; Charuvi, D.; Kupervaser, M.; Reich, Z.; Adam, Z. The thylakoid lumen Deg1 protease affects non-photochemical quenching via the levels of violaxanthin de-epoxidase and PsbS. Plant J. 2025, 121, e17263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Li, X.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, C.; Jiao, C.; Zhao, S.; Kong, Y.; Yan, M.; Huang, J.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals distinct responses to light stress in photosynthesis and primary metabolism between maize and rice. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Kuijer, H.N.J.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Shen, C.; Shi, J.; Betts, N.; Tucker, M.R.; Liang, W.; Waugh, R.; et al. MADS1 maintains barley spike morphology at high ambient temperatures. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 1093–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Q.; Lyu, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, J. The NAT1–bHLH110–CER1/CER1L module regulates heat stress tolerance in rice. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Yao, H.; Ali, Z.; Xiao, M.; Ma, Z.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Cui, J.; et al. VvFHY3 links auxin and endoplasmic reticulum stress to regulate grape anthocyanin biosynthesis at high temperatures. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koae303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Shen, C.; He, Q.; Lei, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, L.; Lin, T.; Guo, Y.; et al. SlHSFB2b-mediated inhibition of jasmonic acid catabolism enhances tomato tolerance to combined high light and heat stress. Plant Physiol. 2025, 199, kiaf547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Primer Sequence | Purpose | Description of the Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PePSAE |

F: ATCATATCGGGTCGGAAGGAAT

R: CTGGAGCATTAGGTGTCAATACG | qRT-PCR | photosystem I reaction center subunit IV B, chloroplastic-like |

| PeMADs | F: CCACAGGTCACCAGGTTACTA R: CTCTTCCAGCTCCTTCAACAC | qRT-PCR | ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain 1B, chloroplastic |

| PebHLH | F: ATGTCTGCTCTCAATCAAGAAGTG R: GAACCTGAACCTGAACCTGAAG | qRT-PCR | stromal 70 kDa heat shock-related protein, chloroplastic |

| PeFAR1 | F: GCTTCAATGTCTCAACTCACTCT R: CGAGCAGCCTCTCAGTAATATAAC | qRT-PCR | POPTRDRAFT_557296; chloroplast biogenesis family protein |

| PePSBS | F: GCATTGGGTCTGAAAGAAGGA R: TGAATAGCACAAGTGGCTCGA | qRT-PCR | photosystem II 22 kDa protein, chloroplastic |

| PePnsB4 | F: CGACAAGCAAGAGGATATTGAAGA R: AACAGTTGAGCAAGATACACAGT | qRT-PCR | photosynthetic NDH subunit of subcomplex B 4, chloroplastic-like |

| PebZIP | F: AGATATACGAGATGATGGCAATGG R: TCTGTCCTCACTTCTGATGGT | qRT-PCR | heat shock protein 90-5, chloroplastic |

| PeC2H2 | F: GCTATGTCTCCGAAGAAGAATCC R: GCGAGCCTTGTCTACATCAC | qRT-PCR | protochlorophyllide reductase, chloroplastic |

| EF-1α |

F: GGCCCAACTGGTCTGACTAC

R: TTGCGGGATCATCCTTGGAG | qRT-PCR | reference genes |

| Sample | Raw Reads | Clean Reads | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | Mapped on Reference | Unmapped | Total Reads After Filtered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QCK (1) | 51,287,788 | 44,193,090 | 0.9967 | 0.9773 | 40,547,199 (81.17%) | 9,405,605 (18.83%) | 49,952,804 |

| QCK (2) | 62,792,542 | 54,291,938 | 0.9965 | 0.9762 | 49,530,223 (80.65%) | 11,882,225 (19.35%) | 61,412,448 |

| QCK (3) | 53,266,446 | 45,808,688 | 0.9965 | 0.9756 | 41,675,714 (80.14%) | 10,329,000 (19.86%) | 52,004,714 |

| Q3 (1) | 49,532,218 | 41,958,066 | 0.9962 | 0.9738 | 37,168,483 (77.14%) | 11,014,853 (22.86%) | 48,183,336 |

| Q3 (2) | 50,657,456 | 43,267,352 | 0.9963 | 0.975 | 38,459,280 (78.0%) | 10,847,700 (22.0%) | 49,306,980 |

| Q3 (3) | 46,420,512 | 39,535,962 | 0.9963 | 0.9748 | 34,067,068 (75.4%) | 11,113,232 (24.6%) | 45,180,300 |

| Q5 (1) | 47,157,740 | 40,116,456 | 0.9964 | 0.9761 | 34,746,886 (76.12%) | 10,899,352 (23.88%) | 45,646,238 |

| Q3 (2) | 91,122,984 | 78,229,472 | 0.9964 | 0.9758 | 67,569,307 (76.05%) | 21,281,433 (23.95%) | 88,850,740 |

| Q5 (3) | 84,360,516 | 60,378,154 | 0.9884 | 0.9602 | 63,400,223 (78.56%) | 17,306,145 (21.44%) | 80,706,368 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niu, X.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Photosynthetic Performance and Gene Expression in Passiflora edulis Under Heat Stress. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010044

Niu X, Xu Y, Jiang L, Wang P, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Lin X, Du L, Zhang Y, Zhu Q, et al. Photosynthetic Performance and Gene Expression in Passiflora edulis Under Heat Stress. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Xianqian, Yunqi Xu, Li Jiang, Pengbo Wang, Zhenjie Zhang, Jiaqi Zhang, Xiuxiang Lin, Lijun Du, Yulan Zhang, Qingqing Zhu, and et al. 2026. "Photosynthetic Performance and Gene Expression in Passiflora edulis Under Heat Stress" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010044

APA StyleNiu, X., Xu, Y., Jiang, L., Wang, P., Zhang, Z., Zhang, J., Lin, X., Du, L., Zhang, Y., Zhu, Q., Zheng, G., & Li, Y. (2026). Photosynthetic Performance and Gene Expression in Passiflora edulis Under Heat Stress. Horticulturae, 12(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010044