Greenhouse Performance of Anemone and Ranunculus Under Northern Climates: Effects of Temperature, Vernalization, and Storage Organ Traits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Vernalization

2.2. Planting and Experimental Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

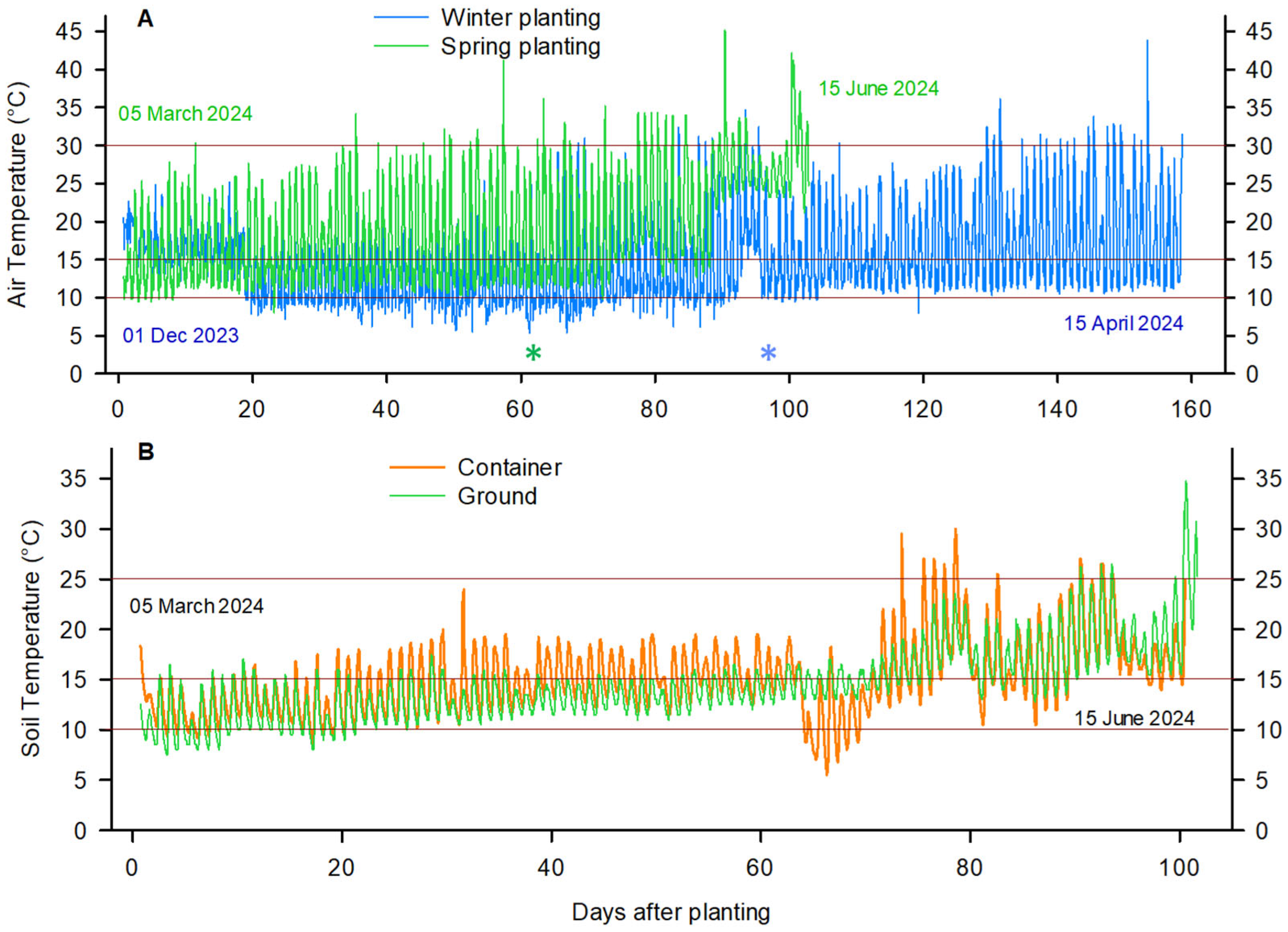

3.1. Recorded Temperatures During Plant Growth in the Greenhouse

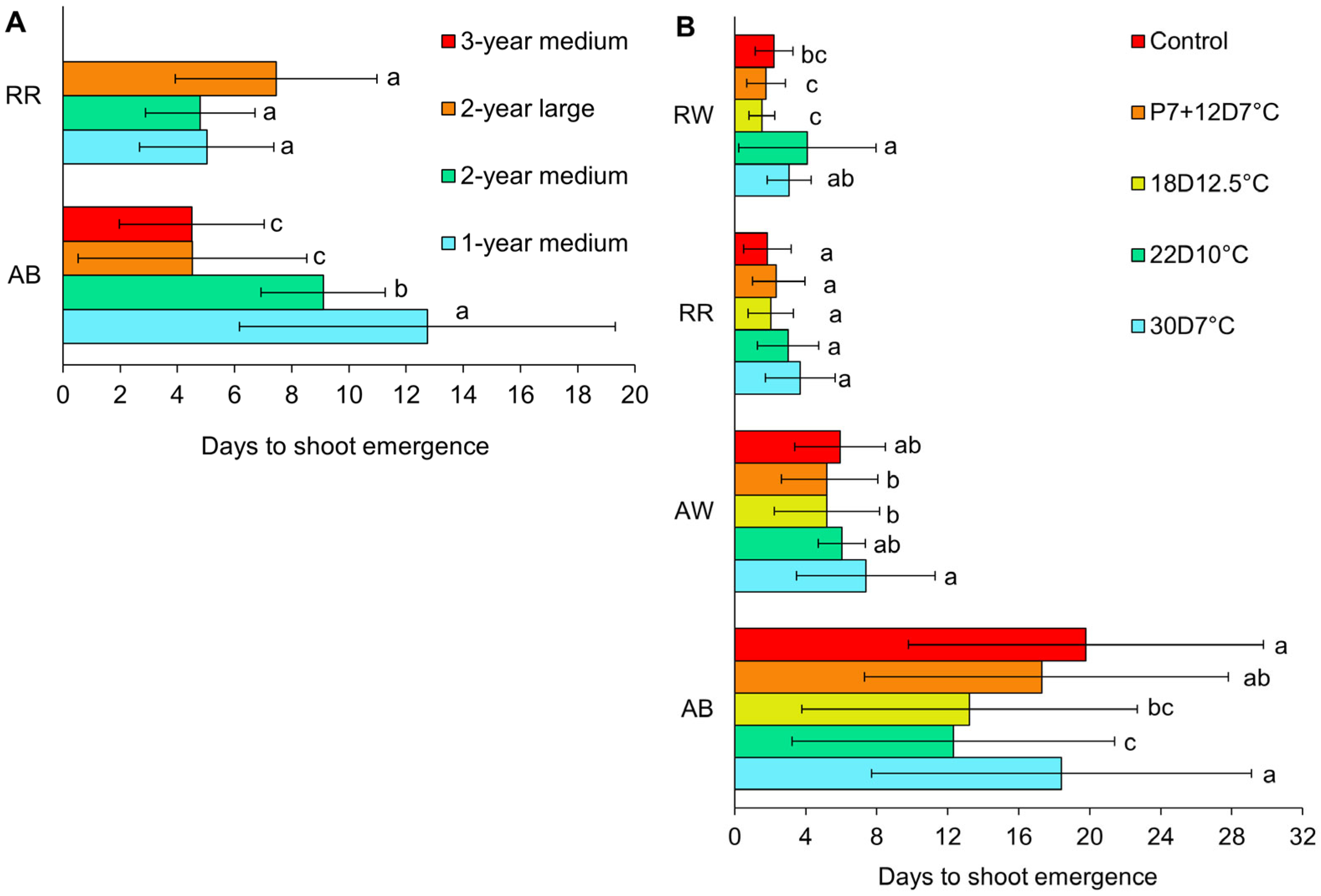

3.2. Shoot Emergence

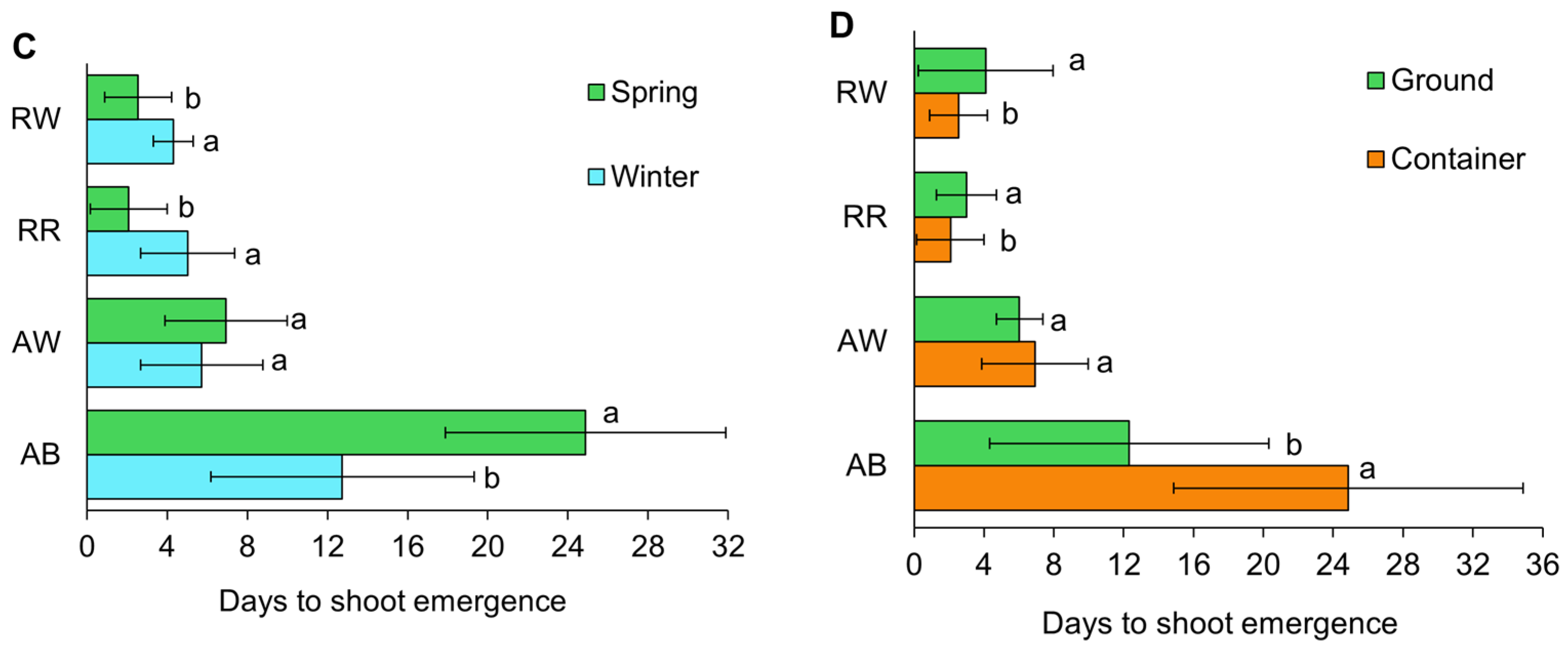

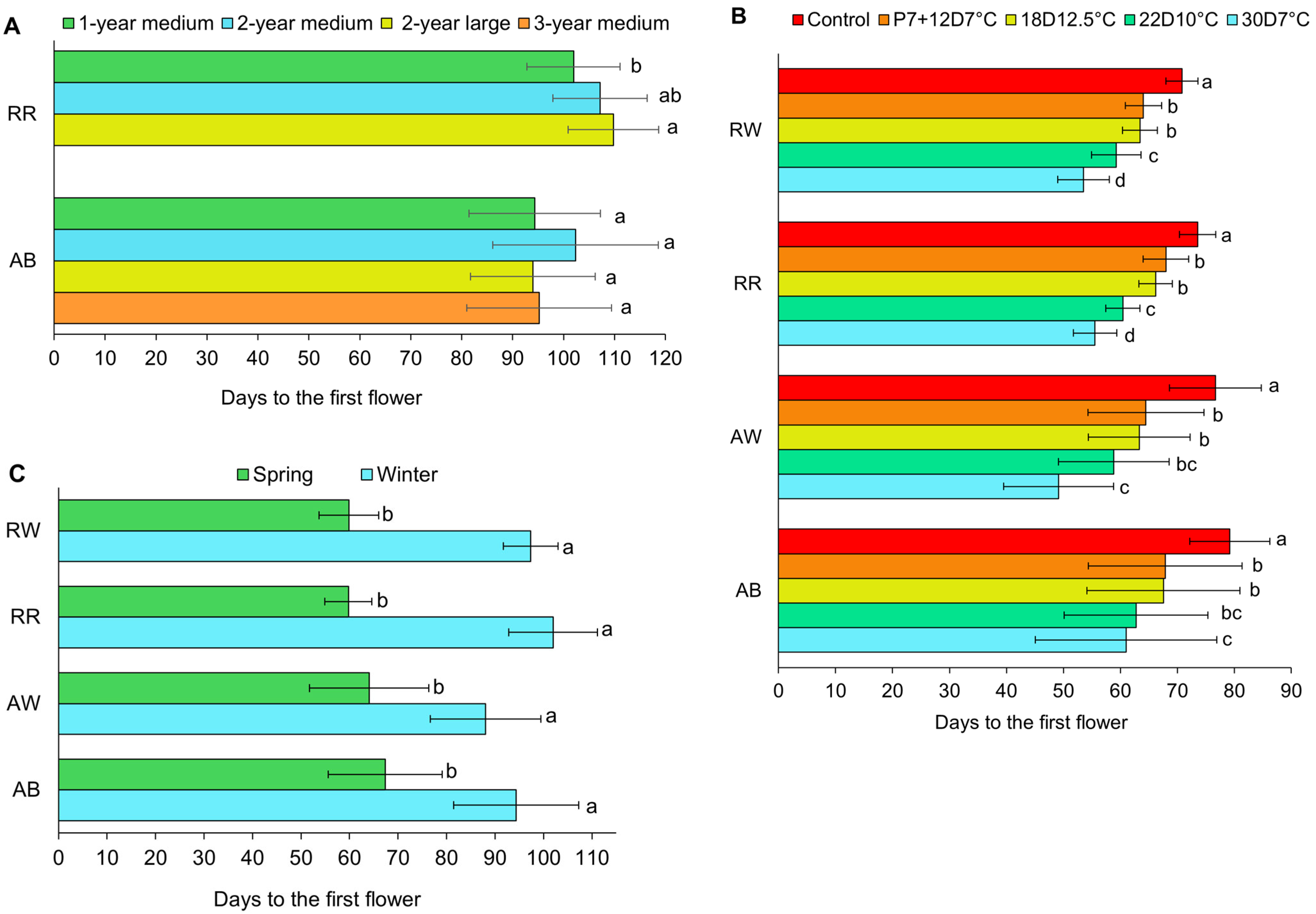

3.3. First Flower

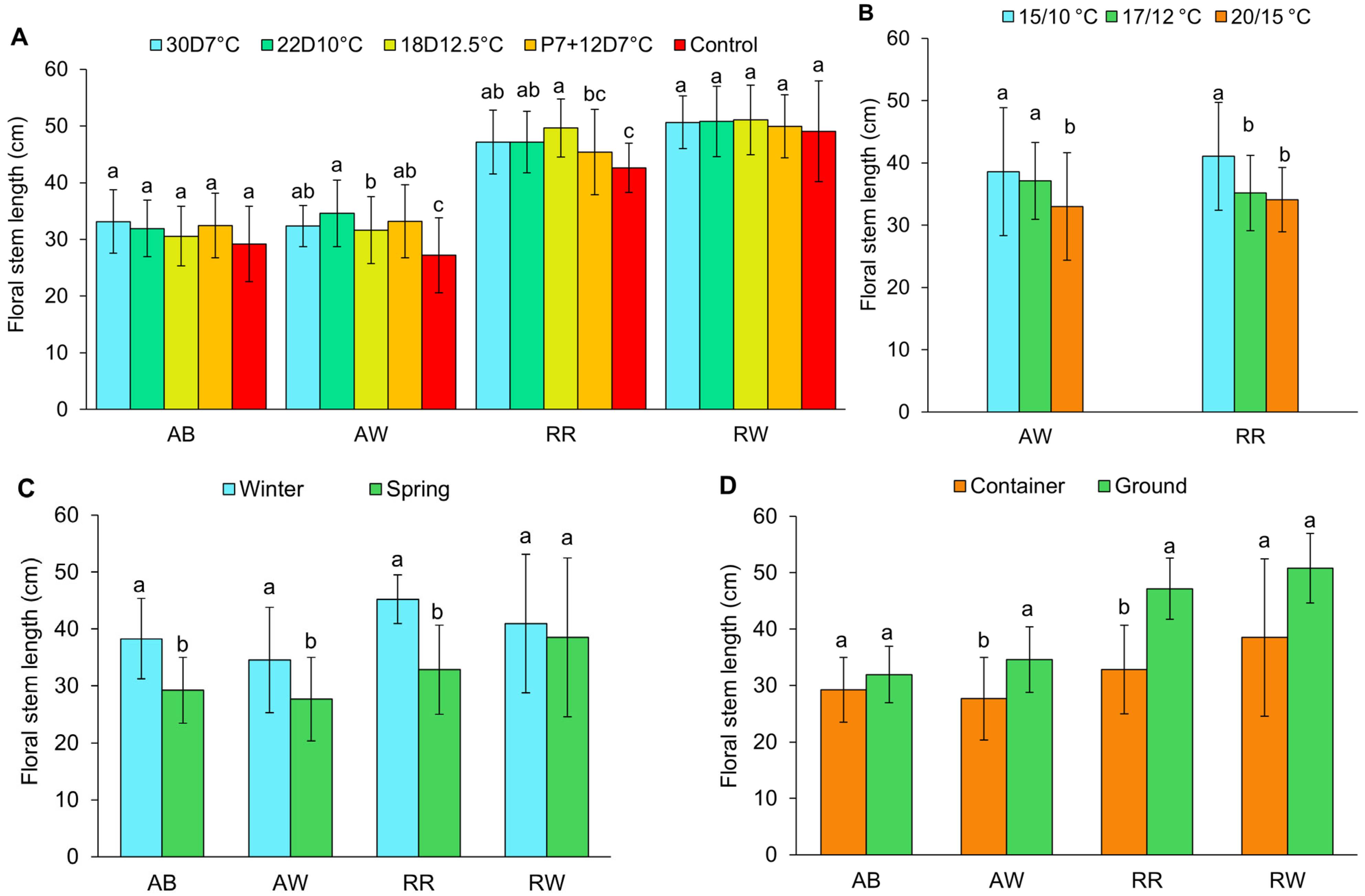

3.4. Floral Stem Length

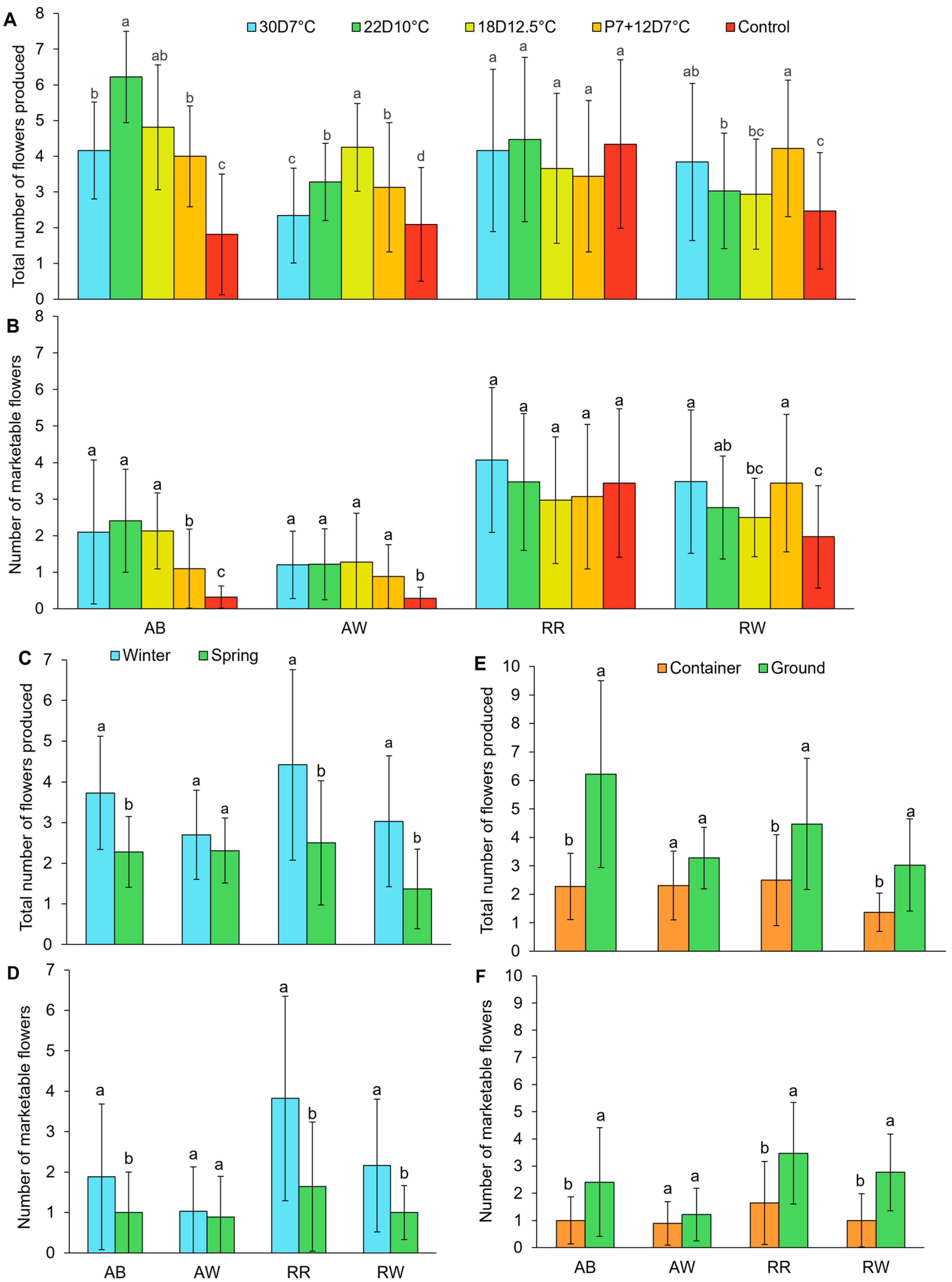

3.5. Total and Marketable Flower Production

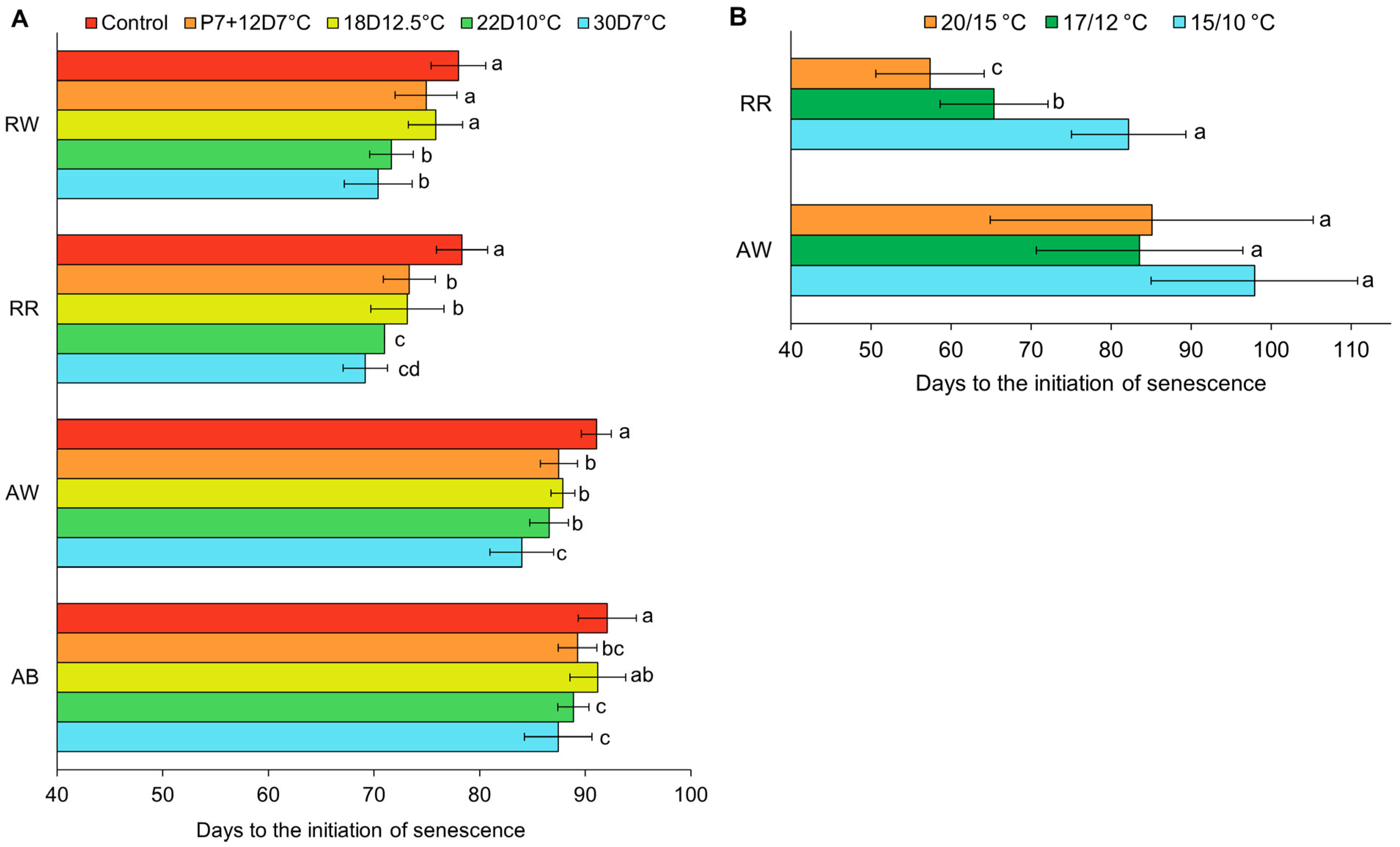

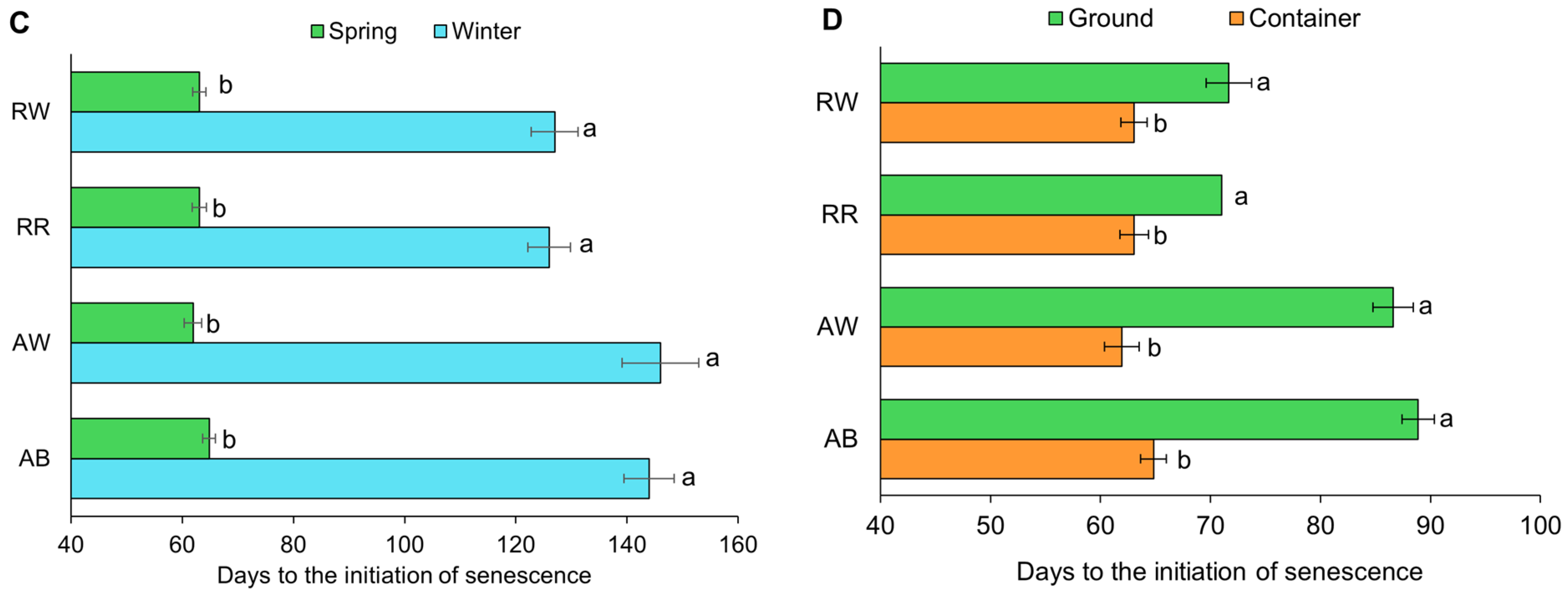

3.6. Onset of Senescence

4. Discussion

4.1. Shoot Emergence

4.2. First Flower Harvest

4.3. Onset of Senescence

4.4. Floral Stem Length

4.5. Flower Yield

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Létourneau, M.F. Dites-le avec des Fleurs... Cultivées au Québec. La Voix de l’Est. 2023. Available online: https://www.lesoleil.com/actualites/actualites-locales/2023/07/09/dites-le-avec-des-fleurs-cultivees-au-quebec-4RUP5CFZUJESHDG5YIRWPUTYTA/ (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Létourneau, M.F. Les Fermes Florales se Multiplient Dans la Région. La Voix de l’Est. 2019. Available online: https://www.lavoixdelest.ca/actualites/les-fermes-florales-se-multiplient-dans-la-region-af98315a6e8d42ade69349641fd5a216 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Gabellini, S.; Scaramuzzi, S. Evolving consumption trends, marketing strategies, and governance settings in ornamental horticulture: A grey literature review. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housley, E. A Bouquet of Benefits: Floriculture and Ecosystem Gifts in an Urban Industrial Zone. Master’s Thesis, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1773/46071 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- De Hertogh, A.; Scheepen, J.; Le Nard, M.; Okubo, H.; Kamenetsky, R. Globalization of the flower bulb industry. In Ornamental Geophytes from Basic Science to Sustainable Production; Kamenetsky, R., Okubo, H., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dole, J.M.; Wilkins, H.F. Floriculture: Principles and Species; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999; p. 613. [Google Scholar]

- Rhin, A.L.; Yue, C.; Behe, B.K. Consumer preferences for longevity information and guarantees on cut flower arrangements. HortScience 2014, 49, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meynet, J. Anemone. In The Physiology of Flower Bulbs: A Comprehensive Treatise on the Physiology and Utilization of Ornamental Flowering Bulbous and Tuberous Plants; De Hertogh, A., Le Nard, M., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Meynet, J. Ranunculus. In The Physiology of Flower Bulbs: A Comprehensive Treatise on the Physiology and Utilization of Ornamental Flowering Bulbous and Tuberous Plants; De Hertogh, A., Le Nard, M., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 603–610. [Google Scholar]

- De Hertogh, A.A. Technologies for forcing flower bulbs. Acta Hortic. 1997, 430, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoot, S.B.; Meyer, K.M.; Manning, J.C. Phylogeny and reclassification of Anemone (Ranunculaceae), with an emphasis on austral species. Syst. Bot. 2012, 37, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola, C.E.; Dole, J.M.; Dunning, R. North American specialty cut flower production and postharvest survey. HortTechnology 2019, 29, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, S.; Stock, M.; Black, B.; Drost, D.; Dai, X.; Ward, R. Overwintering improves Ranunculus cut flower production in the US Intermountain West. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, S.; Stock, M.; Black, B.; Drost, D.; Dai, X.; Ward, R. Anemone cut flower timing, yield, and quality in a high-elevation field and high tunnel. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkawa, K. Growth and flowering of Anemone coronaria L. ‘de Caen’. Acta Hortic. 1987, 205, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horovitz, A. Anemone coronaria and related species. In Handbook of Flowering; Halevy, A.H., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1985; pp. 455–464. [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa, K. Growth and flowering of Ranunculus asiaticus. Acta Hortic. 1986, 177, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenetsky, R.; Zaccai, M.; Flaishman, M.A. Florogenesis. In Ornamental Geophytes from Basic Science to Sustainable Production; Kamenetsky, R., Okubo, H., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 197–224. [Google Scholar]

- Beruto, M.; Fibiani, M.; Rinino, S.; Lo Scalzo, R.; Curir, P. Plant development of Ranunculus asiaticus L. tuberous roots is affected by different temperature and oxygen conditions during storage period. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 57, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarelli, G.C.; Arena, C.; De Pascale, S.; Paradiso, R. The influence of the hybrid and the duration of vernalization of tuberous roots on photosynthesis and flowering in Ranunculus asiaticus L. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1296, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hod, G.; Kigel, J.; Steinitz, B. Dormancy and flowering in Anemone coronaria L. as affected by photoperiod and temperature. Ann. Bot. 1988, 61, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadman-Zahavi, A.; Horovitz, A.; Ozeri, Y. Long-day induced dormancy in Anemone coronaria L. Ann. Bot. 1984, 53, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.; Minchin, P.E.H.; Lapointe, L. Effects of temperature on the growth of spring ephemerals: Crocus vernus (L.) Hill. Physiol. Plant. 2007, 130, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccai, M.; Lazare, S.; Bar, R.; Nishri, Y.; Yasuor, H. De-vernalization—When heat erases flower induction. Acta Hortic. 2025, 1435, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, A.M.; Laushman, J.M. Planting date, in-ground time affect cut flowers of Acidanthera, Anemone, Allium, Brodiaea, and Crocosmia. HortScience 1990, 25, 1236–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, G.M.; Carillo, P.; Nicastro, R.; Modarelli, G.C.; Arena, C.; De Pascale, S.; Paradiso, R. Vernalization procedure of tuberous roots affects growth, photosynthesis and metabolic profile of Ranunculus asiaticus L. Plants 2023, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarelli, G.C.; Arena, C.; Pesce, G.; Dell’Aversana, E.; Fusco, G.M.; Carillo, P.; De Pascale, S.; Paradiso, R. The role of light quality of photoperiodic lighting on photosynthesis, flowering and metabolic profiling in Ranunculus asiaticus L. Physiol. Plant. 2020, 170, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchaa, S.; Lapointe, L. Do recently released cultivars of Ranunculus and Anemone still need vernalization? Acta Hortic. 2025, 1435, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umiel, N.; Hagiladi, A.; Ozeri, Y.; Elyasi, R.; Abramsky, S.; Kanza, M. A standard viability test for corms of Anemone coronaria and Ranunculus asiaticus. Acta Hortic. 1992, 325, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouillet-Ducharme, S. Cut-flower producer and owner of Fleurs de ferme, Ste-Christine, Quebec, Canada. Personal communication, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Benchaa, S.; Girouard, O.; Lapointe, L. Non-Structural and Structural Carbohydrates as Energy Reserves for Regrowth in Anemone coronaria and Ranunculus asiaticus: Insights from Storage Compounds, Histological Analysis, and Phenology. Department of Biology, Université Laval: Québec City, QC, Canada, 2026; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Kawata, J. Optimum temperature and duration of low-temperature treatment for forcing tulips. Acta Hortic. 1975, 47, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hod, G.; Kigel, J.; Steinitz, B. Photothermal effects on corm and flower development in Anemone coronaria L. Sci. Hortic. 1989, 40, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchaa, S.; Lapointe, L. Unpublished Work: Essay on Increasing Versus Constant Photoperiod Effects on Flower Production in Anemone and Ranunculus; Department of Biology, Université Laval: Québec City, QC, Canada.

- Lim, P.O.; Kim, H.J.; Nam, H.G. Leaf senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 58, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Ren, G.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Miao, Y.; Guo, H. Leaf senescence: Progression, regulation, and application. Mol. Hortic. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Osaki, M.; Takebe, M.; Shinano, T.; Wasaki, J. Endogenous hormones and expression of senescence-related genes in different senescent types of maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapointe, L. How phenology influences physiology in deciduous forest spring ephemerals. Physiol. Plant. 2001, 113, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamoto, K.; Nagasuga, K.; Yano, T.; Yamazaki, H. Influence of growing temperature on dry matter accumulation in plant parts of ‘Siberia’ oriental hybrid lily. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2013, 47, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, A.; Gutjahr, S.; Dizengremel, P.; Lapointe, L. Source-sink imbalance increases with growth temperature in the spring geophyte Erythronium americanum. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3467–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, G.A.; Mascarini, L.; Gonzalez, M.N.; Lalor, E. Sand mulching and its relationship with soil temperature and light environment in the cultivation of Lilium longiflorum cut flower. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage/Cultivar | Mean Daily Air Temperature (°C) | Daily Max. Air Temperature (°C) | Growing Degree Days Since Planting | Photoperiod (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergence 1 | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | |

| >AB | 16.8 ± 0.2 a | 16.2 ± 0.3 b | 20.3 ± 0.4 b | 22.4 ± 1.1 a | 152 ± 26 b | 281 ± 64 a | 8.6 ± 0.02 b | 12.8 b ± 0.3 a | |

| AW | 17.6 ± 1.0 a | 15.0 ± 0.5 b | 20.9 ± 1.0 a | 21.2 ± 1.5 a | 70 ± 18 a | 66 ± 27 a | 8.7 ± 0.04 b | 11.5 a ± 0.2 a | |

| RR | 17.9 ± 0.7 a | 14.9 ± 0.1 b | 21.5 ± 0.1 a | 20.3 ± 0.7 b | 64 ± 16 a | 21 ± 7 b | 8.7 ± 0.04 b | 11.4 a ± 0.02 a | |

| RW | 18.6 ± 0 a | 14.9 ± 0.1 b | 20.9 ± 0 a | 20.3 ± 0.7 a | 59 ± 4 a | 25 ± 6 b | 8.7 ± 0.01 b | 11.5 a ± 0.03 a | |

| Flowering 2 | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | |

| AB | 15.9 ± 0.8 b | 18.4 ± 0.1 a | 26.2 ± 0.7 b | 28.7 ± 0.2 a | 1025 ± 94 a | 904 ± 33 a | 11.3 ± 0.1 b | 14.9 ± 0.1 a | |

| AW | 14.8 ± 1.3 b | 18.2 ± 0.1 a | 23.8 ± 1.4 b | 28.5 ± 0.4 a | 870 ± 202 a | 854 ± 105 a | 11.0 ± 0.4 b | 14.8 ± 0.4 a | |

| RR | 16.2 ± 0.6 b | 18.5 ± 0.2 a | 24.2 ± 1 b | 28.3 ± 0.3 a | 1145 ± 24 a | 807 ± 22 b | 11.7 ± 0.3 b | 14.6 ± 0.3 a | |

| RW | 16.3 ± 0.6 b | 18.5 ± 0.1 a | 24.9 ± 1.3 b | 28.2 ± 0.3 a | 1107 ± 91 a | 809 ± 18 b | 11.5 ± 0.2 b | 14.6 ± 0.04 a | |

| Senescence 2 | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | Winter | Spring | |

| AB | 17.9 ± 0.01 b | 18.4 ± 0.1 a | 29.3 ± 0.01 a | 28.7 ± 0.2 a | 1875 ± 3 a | 866 ± 10 b | 13.9 ± 0.01 b | 14.8 ± 0.06 a | |

| AW | 17.9 ± 0 | 18.5 ± 0.11 | 29.3 ± 0.6 a | 28.3 ± 0.2 a | 1895 ± 5 a | 837 ± 15 b | 14.1 ± 0.03 b | 14.7 ± 0.05 a | |

| RR | 16.8 ± 0 | 18.5 ± 0.04 | 24.3 ± 0.1 b | 28.5 ± 0.3 a | 1485 ± 2 a | 851 ± 19 b | 12.9 ± 0.03 b | 14.7 ± 0.06 a | |

| RW | 16.8 ± 0 | 18.5 ± 0.02 | 24.7 ± 0.1 b | 28.4 ± 0.02 a | 1496 ± 0 | 849.7 ± 12 | 13.0 ± 0.01 b | 14.7 ± 0.04 a | |

| Stage/Cultivar | Mean Daily Soil Temperature (°C) | Daily Max. Soil Temperature (°C) | Growing Degree Days Since Planting | Photoperiod (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergence 1 | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | |

| AB | 13.5 ± 0.8 a | 11.1 ± 0.6 b | 17.3 ± 1.0 a | 14.6 ± 0.4 b | 215 ± 59 a | 77 ± 41 b | 12.8 ± 0.3 a | 12.0 ± 0.3 b | |

| AW | 11.9 ± 0.2 a | 10.5 ± 0.04 b | 14.3 ± 0.1 a | 14.2 ± 0.3 a | 48 ± 14 a | 34 ± 3 a | 11.5 ± 0.2 a | 11.6 ± 0.03 a | |

| RR | 14.6 ± 0.3 a | 10.9 ± 0.4 b | 17.6 ± 0.3 a | 14.5 ± 0.5 b | 20 ± 5 a | 18 ± 6 a | 11.4 ± 0.02 a | 11.5 ± 0.05 a | |

| RW | 14.6 ± 0.3 a | 11.5 ± 0.6 b | 17.6 ± 0.3 a | 14.6 ± 0.1 b | 25 ± 4 a | 26 ± 8 a | 11.5 ± 0.03 a | 11.5 ± 0.1 a | |

| Flowering 2 | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | |

| AB | 13.9 ± 1.2 a | 14.0 ± 0.3 a | 16.7 ± 0.8 a | 15.7 ± 0.3 a | 597 ± 57 a | 567 ± 46 a | 14.9 ± 0.1 a | 14.7 ± 0.17 a | |

| AW | 14.3 ± 1.0 a | 13.7 ± 0.4 a | 17.6 ± 0.5 a | 15.4 ± 0.4 b | 596 ± 37 a | 515 ± 68 a | 14.8 ± 0.4 a | 14.5 ± 0.3 a | |

| RR | 15.5 ± 0.04 a | 13.9 ± 0.2 b | 18.2 ± 0.1 a | 15.6 ± 0.2 b | 628 ± 13 a | 536 ± 24 b | 14.6 ± 0.03 a | 14.6 ± 0.1 a | |

| RW | 15.6 ± 0.6 a | 13.7 ± 0.1 b | 18.2 ± 0.1 a | 15.5 ± 0.1 b | 635 ± 13 a | 519 ± 23 b | 14.6 ± 0.04 a | 14.5 ± 0.1 a | |

| Senescence 2 | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | Container | Ground | |

| AB | 14.8 ± 0.3 a | 16.7 ± 1.5 a | 17.4 ± 0.2 b | 21.3 ± 0.5 a | 640 ± 18 b | 1039 ± 147 a | 14.8 ± 0.1 b | 15.6 ± 0.04 a | |

| AW | 15.7 ± 0.1 b | 17.5 ± 0.1 a | 18.2 ± 0.1 b | 21.0 ± 0.1 a | 662 ± 19 b | 1086 ± 2 a | 14.7 ± 0.05 b | 15.6 ± 0.02 a | |

| RR | 15.6 ± 0.3 a | 14.8 ± 0 b | 18.0 ± 0.3 a | 16.4 ± 0 b | 666 ± 18 | 697 ± 0 | 14.7 ± 0.06 b | 15.1 ± 0 a | |

| RW | 15.7 ± 0.04 a | 14.8 ± 0.1 b | 18.1 ± 0.1 a | 16.6 ± 0.2 b | 675 ± 12 a | 708 ± 23 a | 14.7 ± 0.04 b | 15.1 ± 0.04 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Benchaa, S.; Lapointe, L. Greenhouse Performance of Anemone and Ranunculus Under Northern Climates: Effects of Temperature, Vernalization, and Storage Organ Traits. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010043

Benchaa S, Lapointe L. Greenhouse Performance of Anemone and Ranunculus Under Northern Climates: Effects of Temperature, Vernalization, and Storage Organ Traits. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenchaa, Sara, and Line Lapointe. 2026. "Greenhouse Performance of Anemone and Ranunculus Under Northern Climates: Effects of Temperature, Vernalization, and Storage Organ Traits" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010043

APA StyleBenchaa, S., & Lapointe, L. (2026). Greenhouse Performance of Anemone and Ranunculus Under Northern Climates: Effects of Temperature, Vernalization, and Storage Organ Traits. Horticulturae, 12(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010043