1. Introduction

Pomegranates are a nutrient-rich fruit, abundant in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, and are known for their health benefits, including anti-cancer, antioxidant, and immune-boosting effects [

1,

2]. They are widely cultivated in temperate and tropical regions around the world, particularly in Asia, Europe, and North Africa. With the increasing recognition of their health value, commercial cultivation of pomegranates has expanded annually [

3,

4]. Detecting pomegranate fruits presents multiple challenges, especially when using deep learning models [

5]. First, complex orchard environments, such as direct sunlight and canopy shadows, lead to inconsistent image quality, affecting the diversity and accuracy of training datasets. Second, the color similarity between fruits and surrounding backgrounds, such as soil, leaves, and branches, complicates accurate fruit identification, particularly in densely planted orchards [

6,

7]. Third, pomegranates undergo significant changes in shape and size as they mature, requiring models to adapt to different growth stages to ensure accurate recognition. Finally, sensor data are often affected by environmental factors such as dust or weather changes, further impacting detection performance [

8,

9]. Therefore, optimizing data acquisition, image preprocessing, and model robustness is critical for improving the accuracy and efficiency of pomegranate detection.

With the continuous development of deep learning, object detection has achieved remarkable progress in agricultural applications [

10]. Fruit detection has become a crucial component of precision agriculture, especially in automated and intelligent farming systems [

11]. Single-stage object detection methods have gained popularity due to their simple structure and fast inference speed, making them suitable for real-time fruit monitoring systems [

12]. These methods directly regress the bounding box and class label, offering clear advantages in scenarios with limited computational resources. Wang et al. [

13] developed PG-YOLO, which integrates a ShuffleNetv2 backbone and a multi-head self-attention mechanism to enhance the detection of small pomegranate fruits while reducing model complexity. Both studies provide efficient solutions for real-time pomegranate detection. Deng et al. [

14] designed SE-YOLO, a lightweight tomato detection framework optimized for agricultural environments, employing explicit edge awareness and innovative network architectures to improve the detection of occluded fruits. Song et al. [

15] proposed LBSR-YOLO for blueberry monitoring, integrating BSRN with YOLOv10n and incorporating LKWSConv, PConv, FPConv, and ODConv to enhance efficiency and accuracy in low-resolution images. Li et al. [

16] developed a lightweight GP-DETR-based green pepper detection model, optimizing feature extraction, multi-scale detection, and near-color discrimination in complex backgrounds. You et al. [

17] presented VBP-YOLO-prune, an optimized YOLOv8n model integrating V7 downsampling, BiFPN feature fusion, and an improved PIOUv2 loss function, achieving high real-time detection accuracy and deployment efficiency in complex orchards.

Traditional two-stage object detection methods divide the detection process into two steps: first, generating candidate regions, and then performing classification and regression [

18]. Tian et al. [

19] proposed an improved Faster R-CNN model, integrating parallel convolutional neural networks, a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), and Progressive Non-Maximum Suppression (Progressive-NMS) to optimize oat spike detection and counting, achieving a 13.01% increase in mean average precision (mAP) and providing a reference for oat yield prediction. Anthony [

20] designed an efficient Mask R-CNN model, for instance, for the segmentation of strawberry fruits to enhance the efficiency of automated harvesting systems. By leveraging Detectron2 and the NVIDIA TAO Toolkit for training and optimizing the model with NVIDIA TensorRT, the optimized model achieved 83.17 mAP, 25.46 FPS, and a compact size of 48.2 MB, suitable for real-time applications. Li et al. [

21] proposed an improved Strawberry R-CNN model using a multi-stage network, RoIAlign, and bilinear interpolation to enhance strawberry recognition accuracy. Experimental results showed counting accuracies of 99.1% and 73.7% for mature and immature strawberries, respectively, with an average precision of 0.8733, demonstrating its suitability for automated strawberry monitoring and harvesting. While these methods achieve high detection accuracy, their computational complexity and slower inference speed require substantial resources, limiting their application in real-time scenarios.

In fruit detection, many studies have proposed lightweight single-stage models to improve real-time performance and reduce computational demands. However, their effectiveness in real-world agricultural environments is often underexplored. Challenges such as varying illumination and dense fruit clusters can limit the performance of lightweight models, especially for pomegranate detection. In this study, we design a lightweight single-stage detection model and conduct thorough real-world validation. The model architecture is optimized to reduce computational load while maintaining high accuracy. Field tests confirm its efficiency and stability on edge devices. These experiments demonstrate that the model can perform real-time pomegranate detection effectively and operate on resource-constrained hardware, highlighting its practical applicability.

This validated lightweight design offers a practical solution for smart agriculture, especially in pomegranate detection and intelligent harvesting systems. Our findings demonstrate the real-world applicability of lightweight detection models, advancing intelligent agricultural technologies and their use in automated fruit detection and harvesting. The key contributions of this study include the successful deployment of the FSA-DETR-P model on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano, enabling efficient real-time detection with limited computational resources and providing a viable solution for smart orchard automation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Environment and Configuration

To ensure fair comparison and expedite the model training, the enhanced experimental training process was conducted using an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB memory, paired with a 12th Gen Intel Core i5-12400F CPU running at 4.00 GHz. The software environment included CUDA 11.8, Python 3.8.18, and PyTorch 2.1.2, all integrated within the Ultralytics framework. This framework was used to implement the improved RT-DETR architecture and manage the overall training pipeline. To prevent overfitting, an early stopping mechanism was applied, with the patience parameter set to 50 epochs. The hardware configuration used for both training and testing is detailed in

Table 1, while the hyperparameters employed during training are presented in

Table 2.

In this study, we used several evaluation metrics to assess the performance of the proposed model, including mAP50, mAP95, Precision, Recall, the number of parameters, and GFLOPS. Specifically, mAP (Mean Average Precision) evaluates detection performance by calculating average precision at various Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds, with mAP0.50 and mAP0.95 computed separately. Formula (1) calculates mAP, where N represents the number of categories, and “AP(i)” denotes the Average Precision for category i. Precision is the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to all samples predicted as positive, calculated using Formula (2), where TP refers to True Positives and FP to False Positives. Recall is the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to all actual positive samples, calculated using Formula (3), with FN denoting False Negatives. The number of parameters refers to the total trainable parameters in the model, typically measured in millions (M). GFLOPS (Giga Floating Point Operations Per Second) quantifies computational complexity during inference, calculated with Formula (4), where “Total FLOPs” represents the number of floating-point operations required during inference. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s accuracy and efficiency.

3.2. Pruning Experiment

To verify the performance of the proposed improved model under structural compression, comparative experiments with different pruning strategies were conducted on the improved model based on RT-DETR R18.

Table 3 lists the detection performance, number of parameters, and computational complexity (GFLOPs) of four pruning methods (L1, Group Norm, Random, and Lamp) [

32,

33,

34]. As can be seen from the experimental results, the Lamp pruning method achieves the optimal comprehensive performance: its Precision (P) and Recall (R) reach 0.851 and 0.878, respectively, while mAP50 and mAP50–95 are improved to 0.928 and 0.632, all of which are higher than those of other pruning strategies. Meanwhile, the Lamp method effectively reduces model complexity while maintaining high detection accuracy—its number of parameters is reduced to 13.73 M and computational complexity to 34.6 GFLOPs, demonstrating a better performance-efficiency balance compared with the unpruned model or other strategies. In contrast, the L1, Group Norm, and Random pruning methods all experience varying degrees of accuracy degradation after compression, especially a significant drop in the mAP50–95 metric, indicating certain deficiencies in these methods in retaining feature expression capabilities. Overall, the Lamp pruning strategy can significantly reduce the model’s parameter count and computational cost while ensuring detection accuracy, proving its superiority in lightweight deployment scenarios.

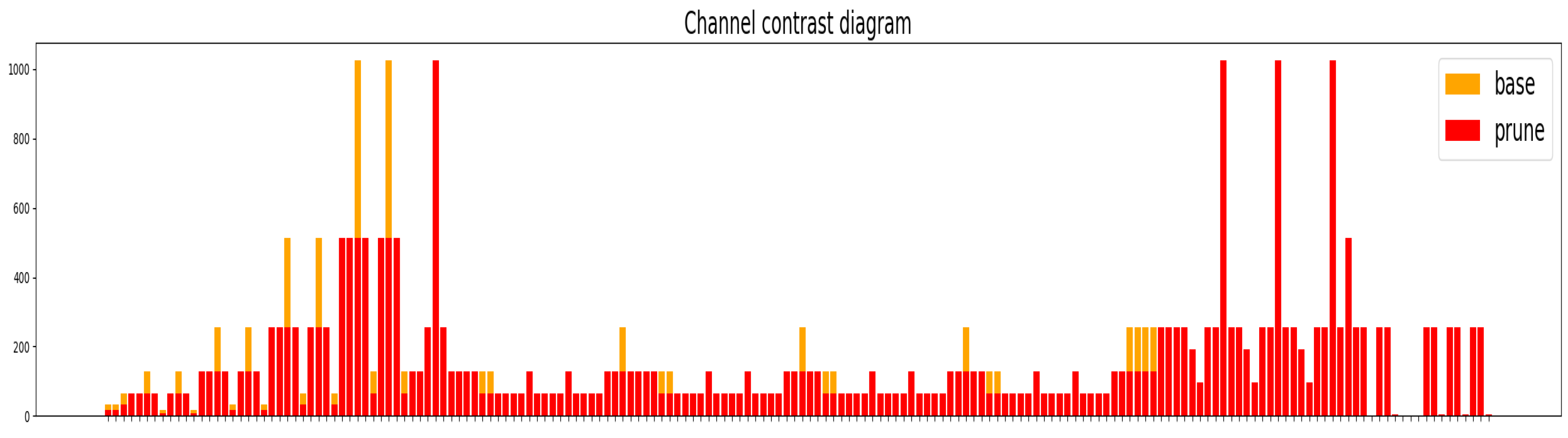

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the number of channels in each layer of the improved RT-DETR R18-based model before pruning (base) and after pruning (prune). It can be observed that the pruning operation has a significant non-uniform impact on different layers of the model: the number of channels in some convolutional layers is drastically reduced, while that in some key feature extraction layers changes slightly. This hierarchical channel retention reflects the adaptive selection mechanism of the pruning algorithm in structural optimization—prioritizing the preservation of channels that contribute significantly to feature expression while removing redundant or low-importance feature channels.

From the overall trend, the number of channels in the pruned model is significantly reduced in most layers, especially in the middle and high-level convolutional modules and the decoding head, where the channel reduction is relatively concentrated. This indicates that the pruning process effectively reduces redundant computations in the network and achieves a significant structural compression effect. Meanwhile, some feature fusion layers (such as cross-layer connections and decoding layers) still retain a relatively large number of channels, demonstrating that the model maintains the ability to transmit key semantic information while achieving structural compression, which is conducive to preserving detection accuracy.

Combined with the experimental results, the pruned model still maintains high detection accuracy (mAP50 = 0.928, mAP50–95 = 0.632) with the number of parameters and computational complexity reduced to 13.7 M and 34.6 GFLOPs, respectively. This verifies the effectiveness of the pruning strategy in balancing model lightweighting and performance. Overall, the pruning scheme can sufficiently reduce model complexity while maintaining stable detection performance, laying a solid foundation for the deployment of the model on edge devices.

3.3. Model Training and Comparison

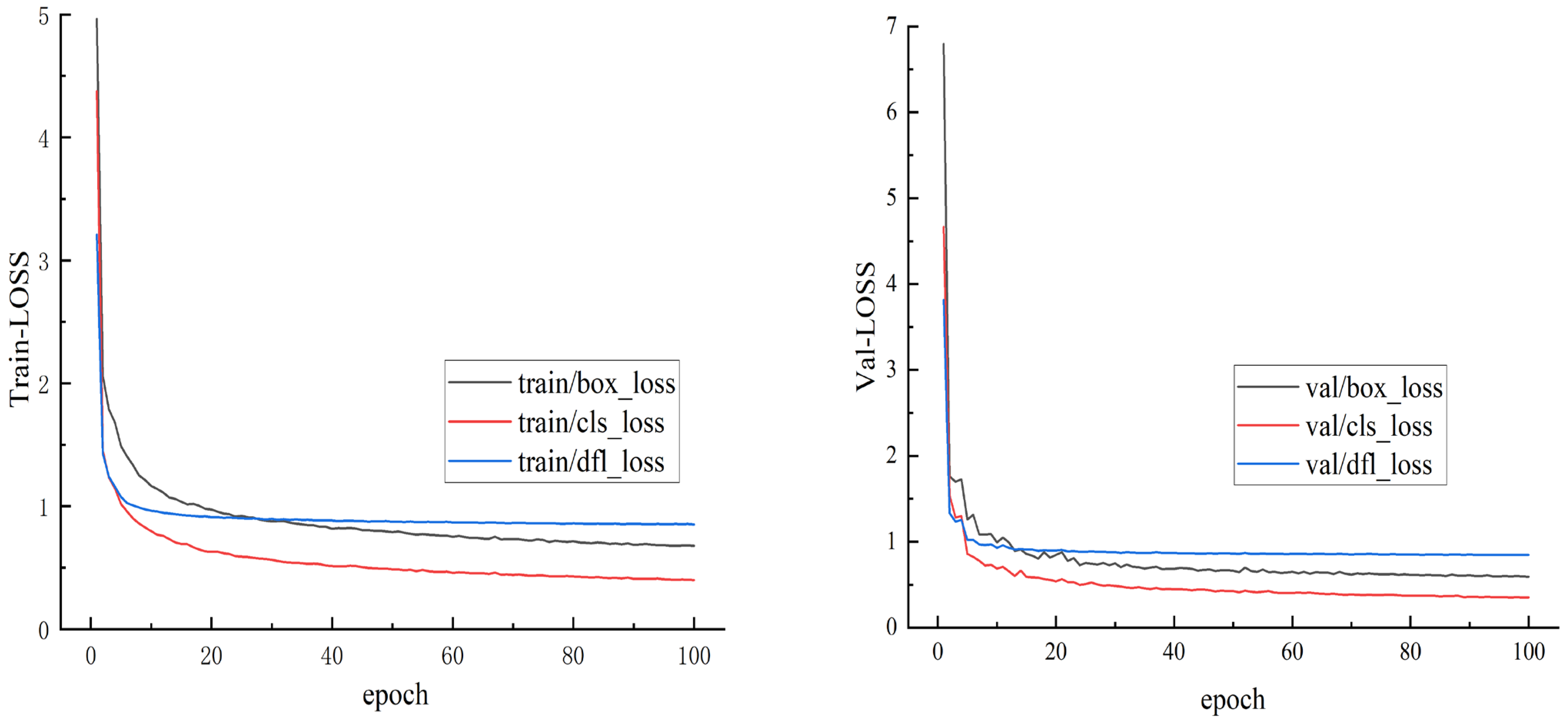

Figure 10 presents the convergence process of the model. Both training and validation losses decrease consistently and stabilize after 60 epochs, reaching a state of steady-state convergence. The high degree of synchronicity between the training and validation curves indicates excellent model generalization and confirms that the hyperparameter settings are appropriate for the task. No gradient explosion or overfitting was observed during the 100-epoch training duration.

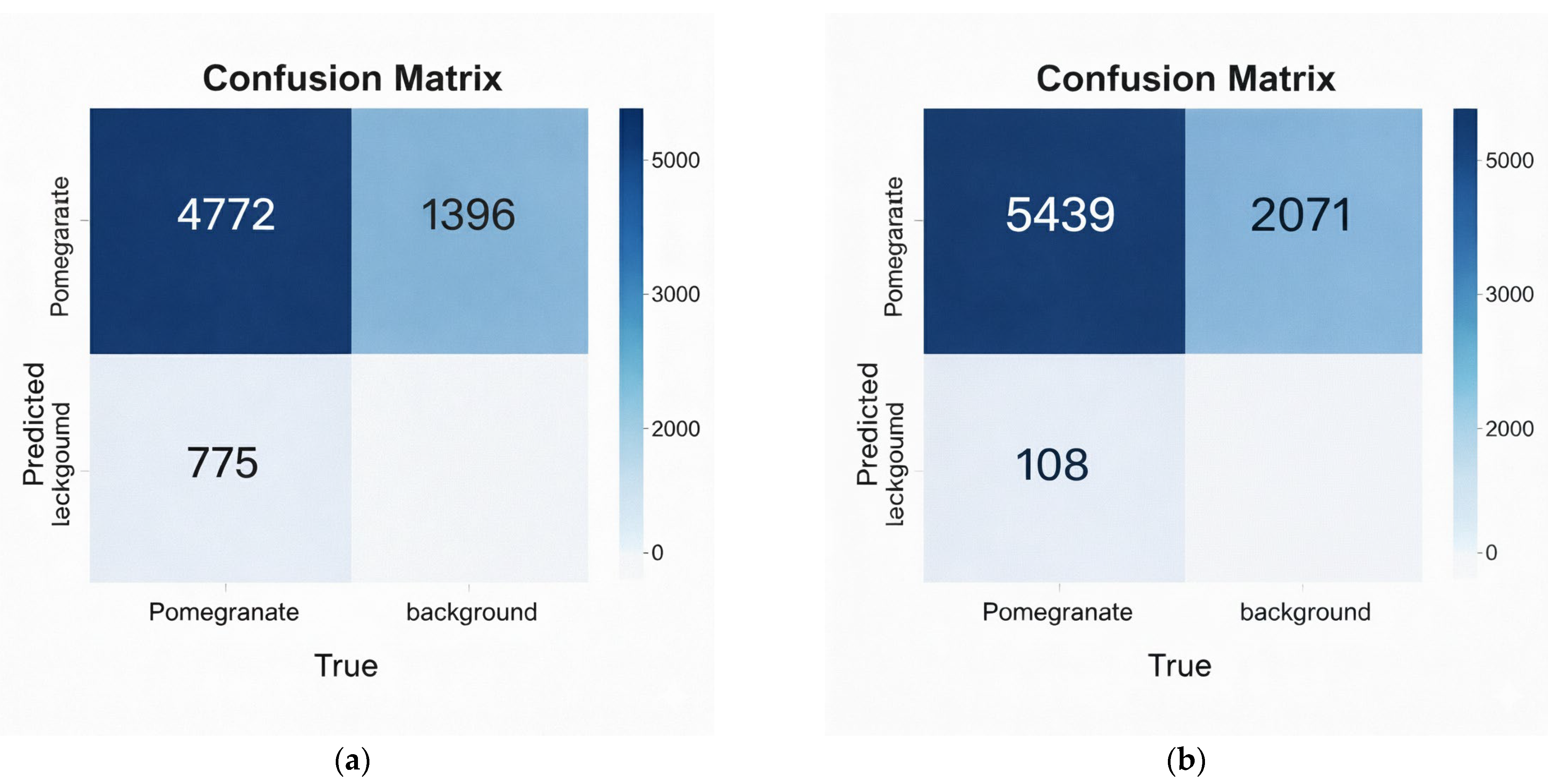

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed improvements, we compared the confusion matrices of the baseline model and the proposed method (

Figure 11). The results demonstrate a significant enhancement in the model’s ability to capture targets in complex environments. Specifically, the number of True Positives (TP) increased from 4772 to 5439, indicating a stronger feature extraction capability. More importantly, the proposed method achieved a decisive reduction in False Negatives (FN), dropping from 775 in the baseline to only 108. This represents an 86.1% reduction in the miss rate, proving that the improved model effectively resolves the issue of missed detections caused by occlusion or small target size. It is noted that the number of False Positives (FP) increased from 1396 to 2071. This shift reflects a strategic trade-off: the model was designed with higher sensitivity to ensure that obscure or ambiguous targets are not overlooked. In the context of agricultural applications, prioritizing Recall (minimizing False Negatives) is critical to guarantee accurate yield estimation and harvesting, making the acceptance of slightly higher False Positives a necessary and robust strategy.

3.4. Ablation Experiment

To verify the impact of each improved module on pomegranate detection performance, this study takes RT-DETR R18 as the base model and gradually introduces the FasterNet feature enhancement module, ASF (Adaptive Spatial Fusion) module, and Slimneck lightweight neck structure. The final model is combined with a pruning strategy for performance evaluation, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 4.

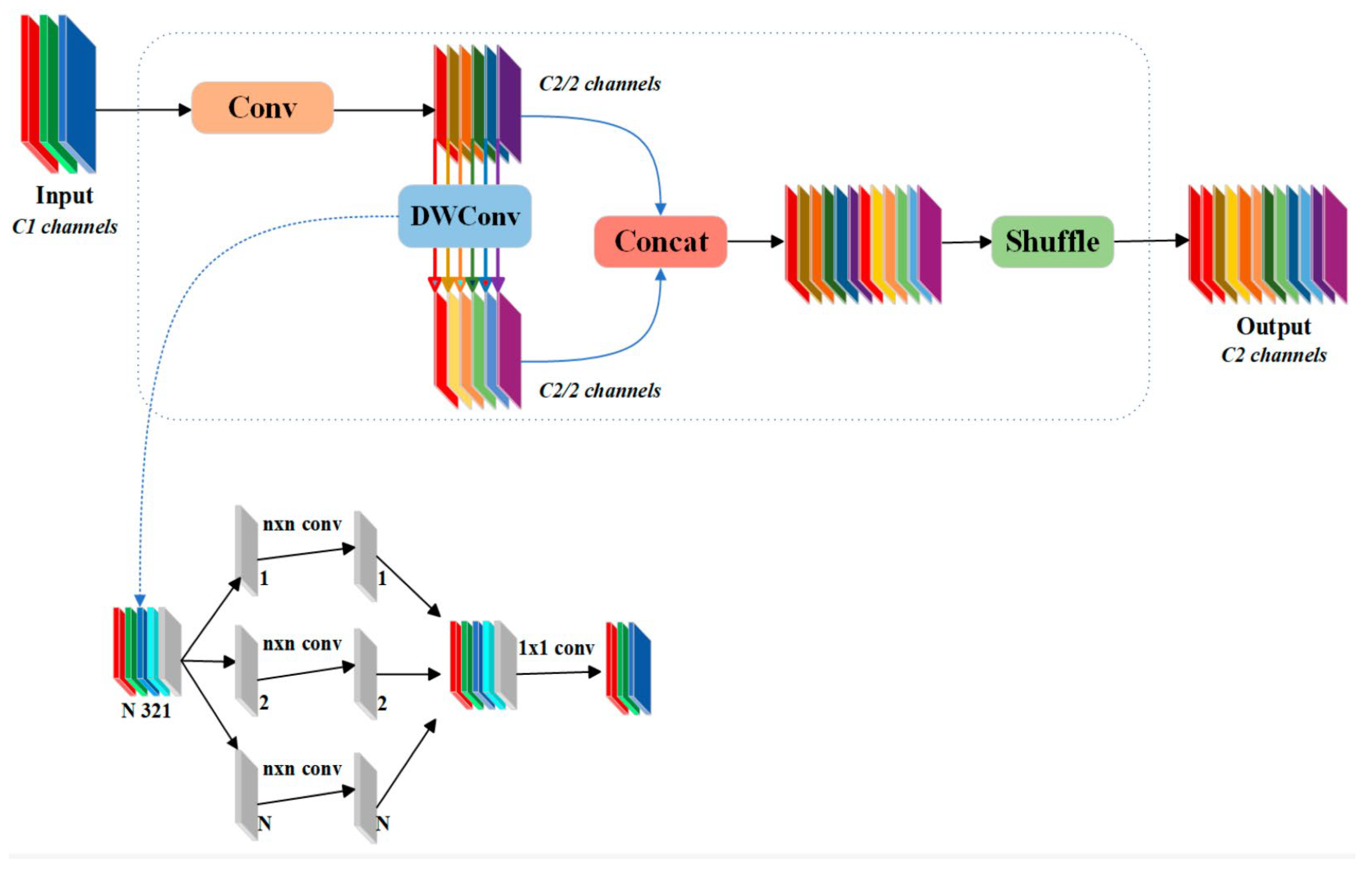

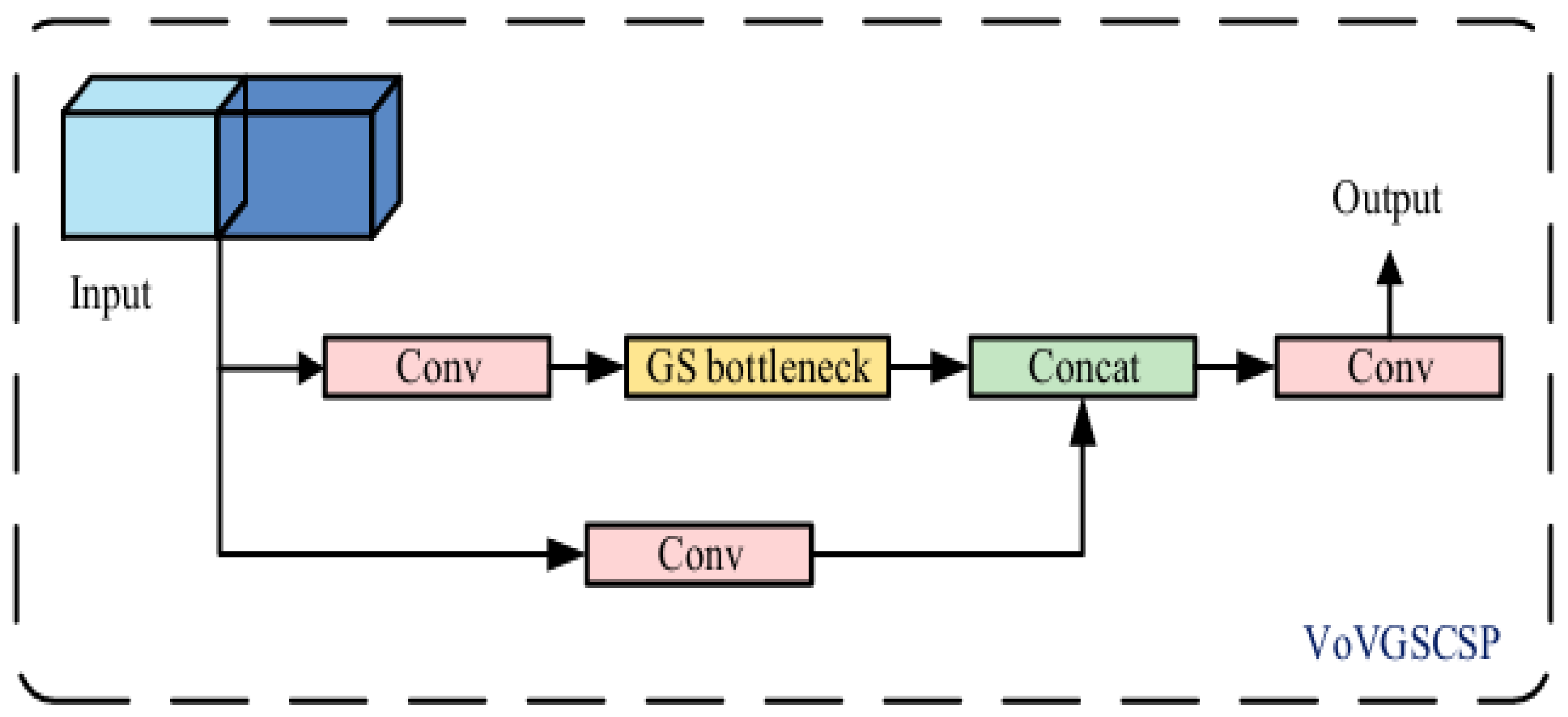

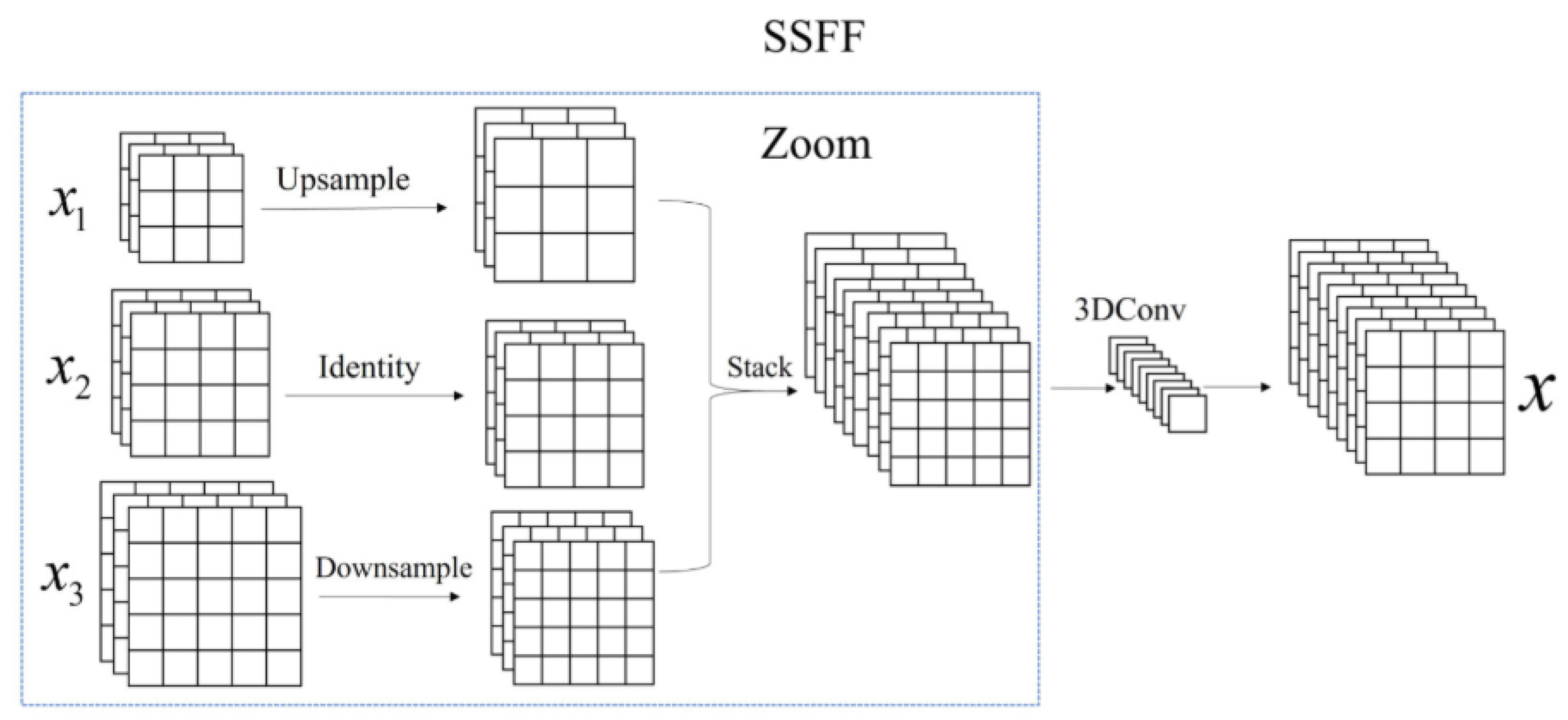

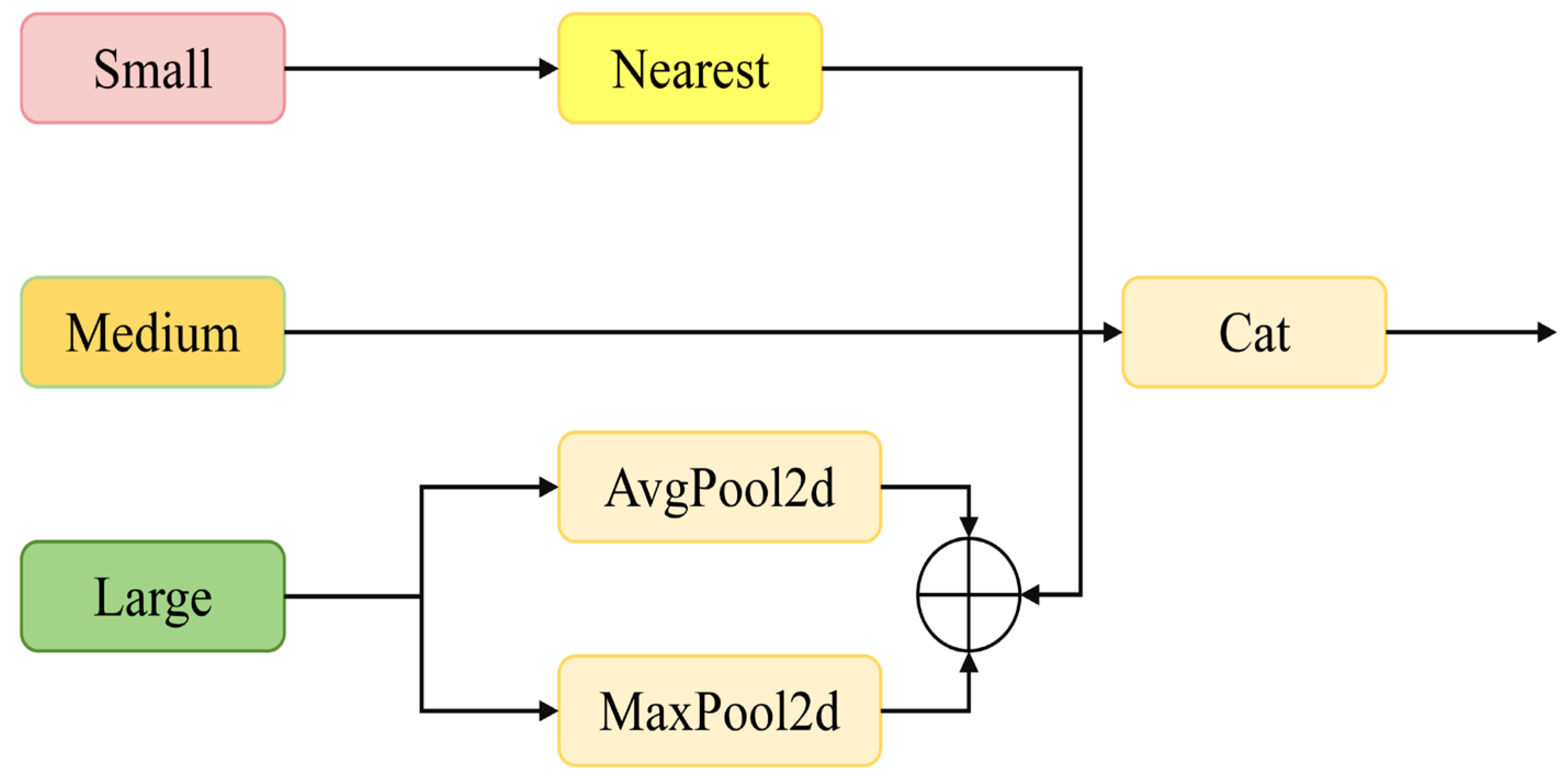

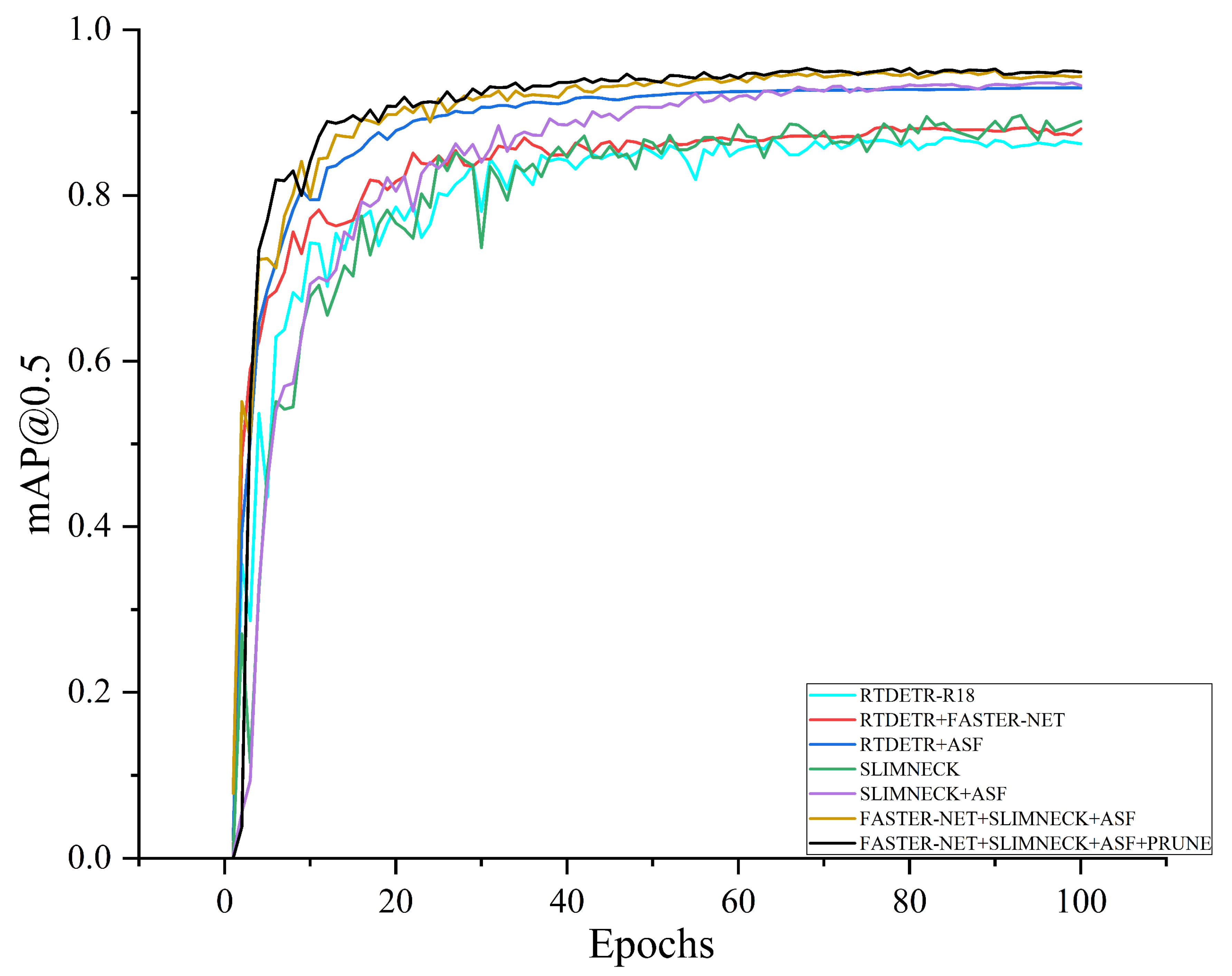

Starting with the base model RT-DETR R18, its mAP50 and mAP50–95 are 0.881 and 0.585, respectively. After introducing the FasterNet module, the detection accuracy is significantly improved (mAP50 increased to 0.905), mainly due to the multi-scale feature enhancement mechanism introduced by this module in the feature extraction stage, enabling the model to better capture key information of pomegranates under different sizes and occlusion conditions. On this basis, adding the ASF (Adaptive Spatial Fusion) module further improves the model performance (mAP50–95 increased from 0.589 to 0.620). The ASF module fuses multi-scale feature maps through adaptive weights, effectively enhancing the expression ability of spatial features and making the model more accurate in recognizing pomegranate contours and surface textures in complex backgrounds. However, the ASF module also leads to an increase in the number of parameters and computational complexity (to 20.15 M and 61.4 GFLOPs). In contrast, the Slimneck structure, through a lightweight feature aggregation and information compression mechanism, effectively reduces model complexity while maintaining detection performance (the number of parameters is reduced to 19.31 M, and GFLOPs to 53.6). Its ability to maintain a high mAP50 (0.904) while reducing computational overhead indicates that the Slimneck structure has excellent performance in terms of feature transmission efficiency. Furthermore, after combining Slimneck with the ASF module (Slimneck + ASF), the model’s mAP50–95 is increased to 0.615, demonstrating a complementary effect between the two in feature fusion and information compression: The ASF module strengthens spatial information, and the Slimneck optimizes information flow channels, working together to improve detection accuracy. After introducing the combination of FasterNet + Slimneck + ASF, the model maintains low complexity (50.1 GFLOPs) while mAP50 is increased to 0.921 and mAP50–95 reaches 0.625, indicating that this combination achieves a balance between performance and efficiency in feature extraction and fusion.

Finally, after applying the pruning strategy on this basis, the model’s number of parameters is significantly reduced to 13.73 M, and computational complexity to 34.6 GFLOPs, while mAP50 and mAP50–95 are further increased to 0.928 and 0.632, respectively. This shows that pruning removes redundant channels while retaining high-contribution features, effectively improving the model’s inference efficiency and generalization ability. In

Section 3.2, we have conducted experimental analysis on different pruning methods and ultimately selected the Lamp method.

Figure 12 presents the mAP50 performance curve for the RT-DETR R18 model with various combinations of improved modules in pomegranate detection tasks. The curve shows a steady improvement in detection accuracy as additional modules are integrated. Notably, after adding the FasterNet module, the mAP50 increases significantly, indicating enhanced multi-scale feature extraction. With the introduction of the ASF module, mAP50–95 further improves, demonstrating that the adaptive spatial fusion mechanism helps better integrate spatial feature information across levels. The Slimneck structure maintains high detection performance while achieving a lightweight design, proving its efficiency in feature aggregation and information transmission. When all three modules are combined, the model reaches its highest performance. After applying pruning, both the number of parameters and computational complexity are significantly reduced, yet the accuracy improves, suggesting that pruning removes redundant channels and boosts the model’s feature representation. Overall, the curve demonstrates the synergistic benefits of the proposed strategies in improving detection performance while ensuring model lightweighting.

3.5. Model Comparison Experiment

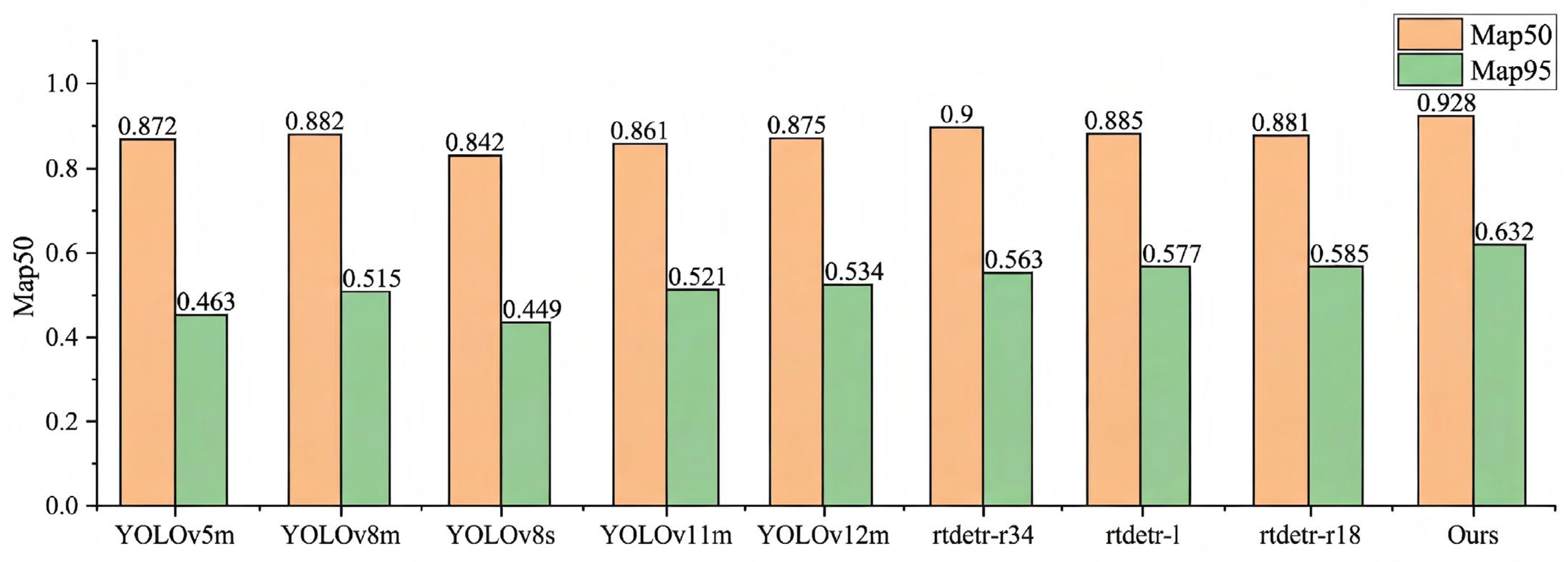

To evaluate the overall performance of the proposed improved model in the pomegranate detection task, we conducted comparative experiments with several mainstream object detection models, including different versions of the YOLO series (YOLOv5m, YOLOv8m, YOLOv11m, YOLOv12m) and the RT-DETR series (RT-DETR-R18, RT-DETR-R34, RT-DETR-L). The experimental results, presented in

Table 5, show that the proposed model (Ours) outperforms the others in both detection accuracy and model complexity. Specifically, our model achieves higher detection accuracy while maintaining lower computational complexity, making it more suitable for resource-constrained environments without sacrificing performance.

From the perspective of detection performance, the YOLO series models have certain advantages in terms of lightweight and real-time performance, but their detection accuracy in complex backgrounds is still insufficient. Among them, the mAP50–95 of YOLOv12m is 0.534, which is slightly higher than that of YOLOv8m, but the overall performance is still lower than that of the RT-DETR series models. In contrast, RT-DETR models, relying on their Transformer-based end-to-end detection structure, have more advantages in feature expression capability. The mAP50–95 of RT-DETR-R18 reaches 0.585, and the R34 and L versions are further improved to 0.563 and 0.577, indicating that they are more excellent in global modeling capability and spatial information fusion. However, although the RT-DETR-R18 is superior to the YOLO series in accuracy, its model parameter quantity and computational complexity are relatively high (up to 19.87 M parameters and 56.9 GFLOPs), which limits its application on resource-constrained devices. In contrast, after introducing the FasterNet feature enhancement module, ASF adaptive spatial fusion module, Slimneck lightweight structure and combining with pruning optimization, the improved model proposed in this paper (Ours) achieves the optimal detection performance: the precision (P) and recall (R) reach 0.851 and 0.878, respectively, and the mAP50 and mAP50–95 are improved to 0.928 and 0.632, respectively. At the same time, the parameter quantity and computational complexity are significantly reduced to 13.73 M and 34.6 GFLOPs, which are about 30.9% less in parameter quantity and 39.2% less in computational cost compared with RT-DETR-R18 (

Figure 13).

In summary, the proposed model achieves significant lightweight effects while ensuring high-precision pomegranate detection, balancing detection performance and inference efficiency, and demonstrating excellent comprehensive performance and strong potential for practical application.

Figure 13 is a bar chart comparison of the mAP index, which more intuitively reflects the gaps in the core index mAP among various models.

4. Discussion

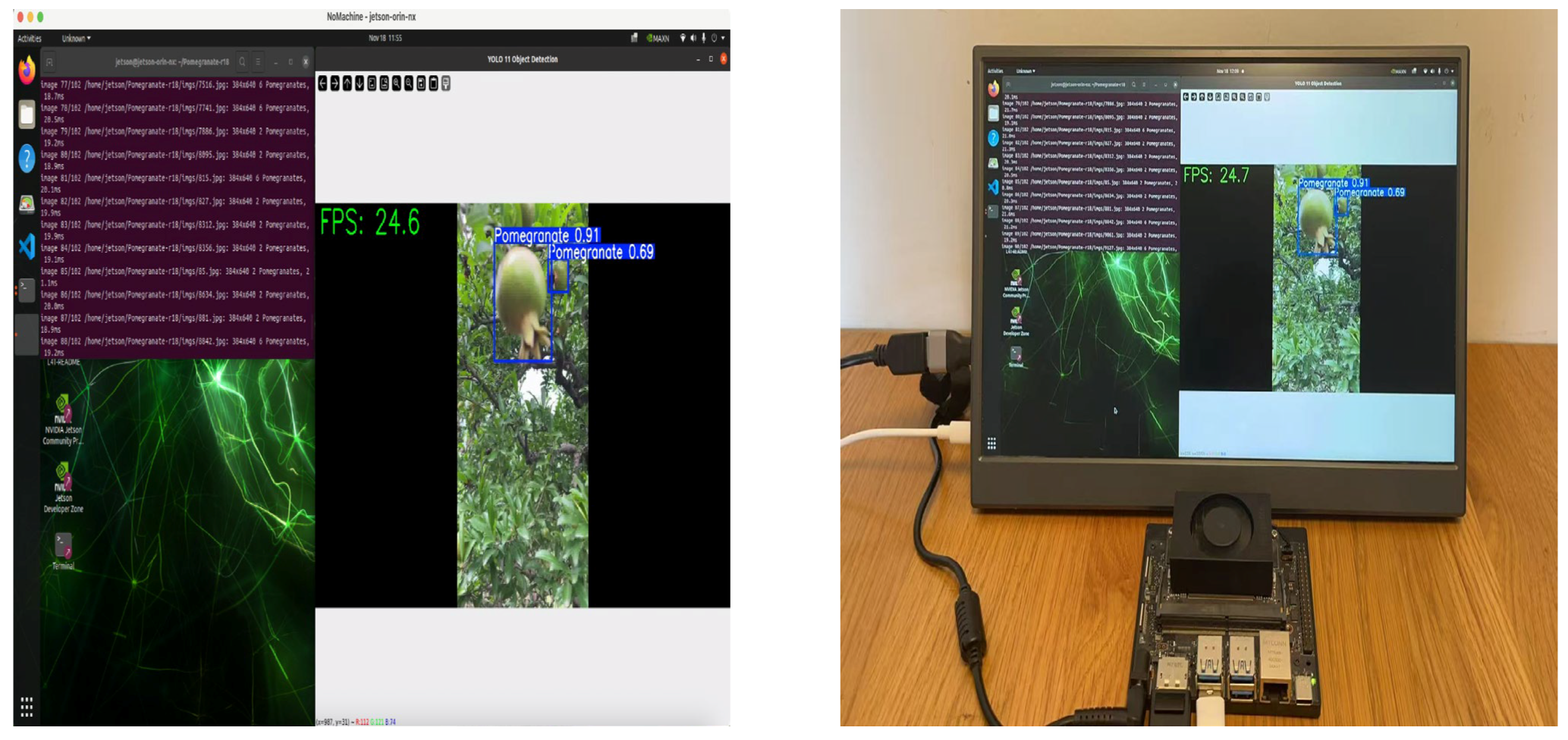

This study focuses on pomegranate detection in complex orchard environments. Experimental results confirm that the improved model, integrated with FasterNet, ASF, Slimneck modules, and Lamp pruning, outperforms mainstream models (YOLOv5, YOLOv8, RT-DETR) in mAP50/mAP50–95 with fewer parameters and GFLOPs. It also maintains stable real-time performance (24.6 FPS) on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano, addressing resource and latency constraints in agricultural automation. This section further discusses the model’s structural advantages, limitations, and future improvements.

In addition, the introduction of the pruning strategy further optimizes the network structure. Compared with traditional pruning methods such as L1, Group Norm, or random pruning, Lamp pruning is more targeted in channel selection. It can effectively remove redundant parts while retaining high-contribution feature channels, thereby significantly reducing the model’s parameter count and computational load with almost no loss in accuracy. This result indicates that after structural optimization, the model has stronger generalization ability and inference efficiency, making it particularly suitable for resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and edge computing.

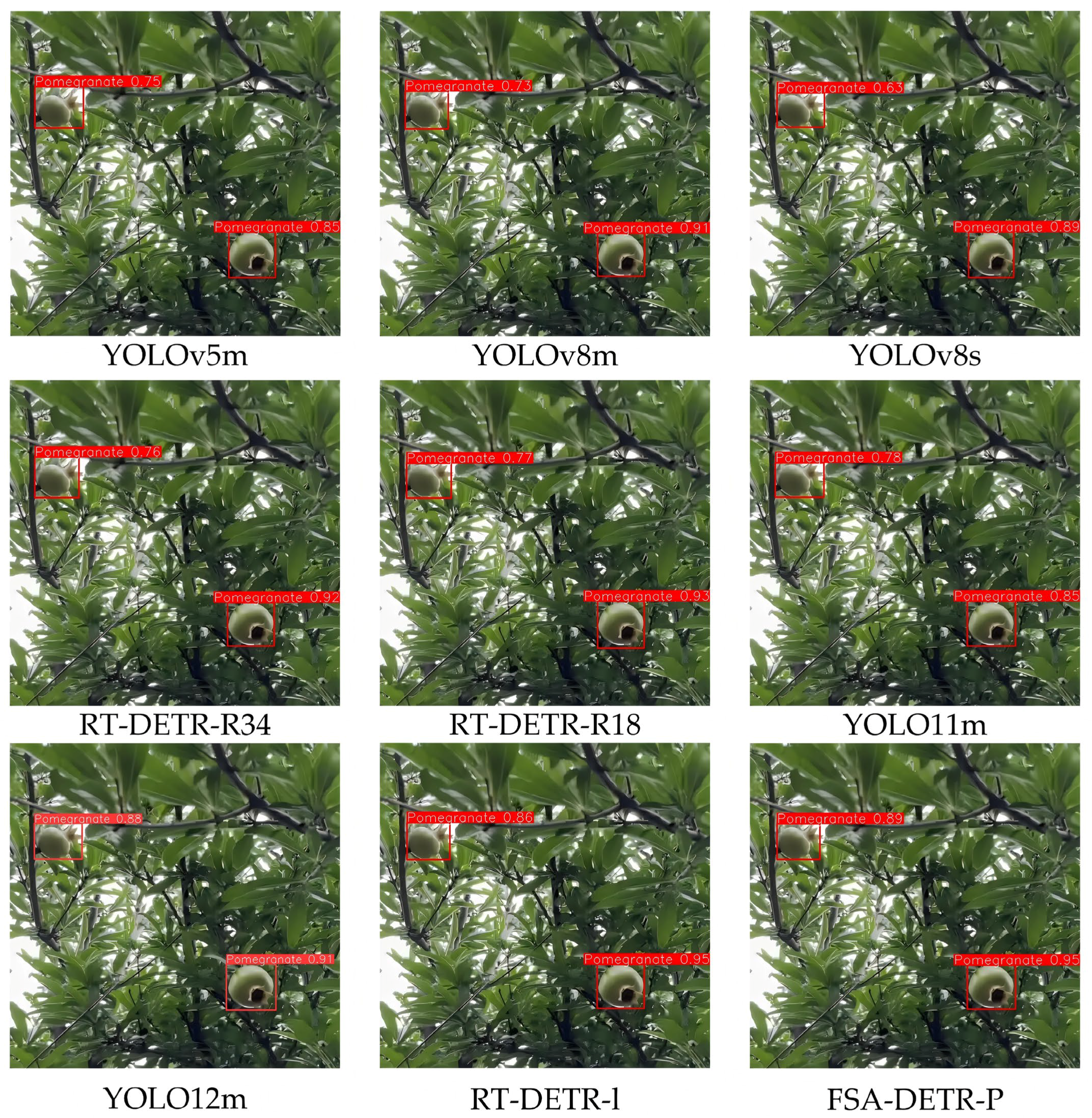

Based on the comprehensive comparison of experimental results, the proposed model in this paper outperforms the YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and RT-DETR series models in both mAP50 and mAP50–95 metrics, with a significant reduction in parameter count and GFLOPs. This demonstrates that this study has achieved efficient model compression and structural optimization under the premise of ensuring detection accuracy, verifying the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed improvement strategies. Structurally, the proposed model occupies a strategic position between the ultra-lightweight YOLO-n/s variants (which prioritize speed but often compromise on accuracy) and the heavier YOLO-m variants. While the parameter counts of FSA-DETR-P (13.73 M) are significantly lower than those of the YOLO-m series (e.g., YOLOv8m at 25.84 M), it delivers detection performance that exceeds these heavier models. This indicates that our model effectively bridges the gap between lightness and precision, offering a superior trade-off that maintains high accuracy with reduced complexity compared to the ‘m’ variants. As shown in

Figure 14, it presents the visualization results of pomegranate detection in complex natural environments for the YOLO series (YOLOv5m, YOLOv8m, YOLOv11m, YOLOv12m), RT-DETR series (RT-DETR-R18, RT-DETR-R34, RT-DETR-L), and the proposed model (Ours). Overall, there are significant differences in the detection performance of different models under conditions of occlusion, illumination changes, and background interference.

As shown in the figure, the YOLO series models often struggle with inaccurate detection box positioning or missed detections in certain scenarios. This is particularly evident in areas with leaf occlusions or similar background colors, where the models tend to blur target boundaries or miss smaller targets. On the other hand, the RT-DETR series models, which leverage the Transformer structure for global feature modeling, perform better in identifying partially occluded pomegranates. However, they still suffer from occasional false detections in complex backgrounds. In contrast, the improved model proposed in this study (Ours) demonstrates superior accuracy in detecting pomegranate targets. It achieves precise detection box placement, clear target boundaries, and almost no missed or false detections. This exceptional performance can be attributed to several enhancements: the FasterNet module’s ability to extract multi-scale features, the ASF module’s adaptive spatial fusion mechanism, and the Slimneck structure’s efficient feature aggregation. These improvements allow the model to distinguish pomegranates from complex backgrounds in vegetated environments more effectively. Additionally, the pruning strategy boosts the model’s inference efficiency, ensuring high-precision detection even under lightweight conditions.

In summary,

Figure 14 intuitively verifies that the improved model proposed in this paper has stronger feature expression capability and robustness in pomegranate detection tasks and can achieve stable and accurate detection results under conditions of complex illumination, occlusion, and background interference.

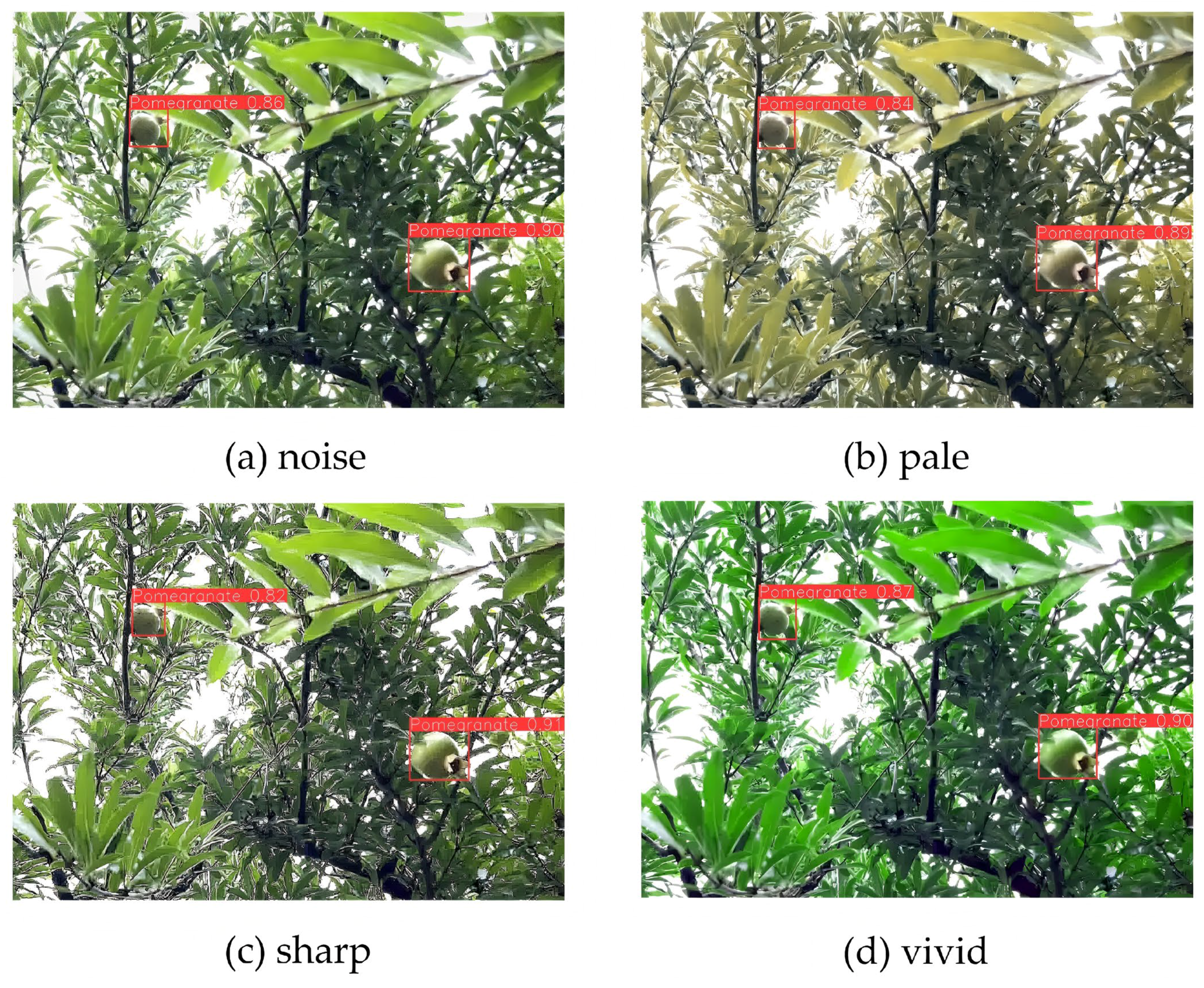

To assess the robustness and generalization capabilities of the FSA-DETR-P model, images were randomly sampled from the test set and subjected to a range of data augmentation techniques. These included noise injection, desaturation, sharpening, and saturation enhancement. The detection results, shown in

Figure 15, clearly demonstrate that the model maintains strong performance even under these altered conditions, effectively validating its robustness and generalization ability. The model consistently identifies pomegranate targets accurately, even when faced with various types of image distortions, indicating its adaptability to diverse real-world environments.

The improved RT-DETR-R18 model, deployed on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano, demonstrates its strong adaptability and efficiency on edge devices. The NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano was selected as the deployment platform because it offers an optimal balance between AI computing performance (up to 40 TOPS), power efficiency (7 W–15 W), and cost. This configuration represents a typical hardware setup for mobile agricultural robots, where maintaining high inference speed under limited battery and thermal constraints is critical. This model requires minimal computational resources while achieving high-precision detection of pomegranate fruits in complex orchard environments [

35,

36,

37]. Despite challenges such as dense fruit distribution and varying lighting conditions, it maintains stable performance. With its lightweight design and optimized detection algorithm, the model processes large volumes of image data in real time, achieving a frame rate of 24.6 FPS. This makes it highly suitable for practical applications in agricultural automation, meeting the demands for both efficiency and accuracy. As the model is applied in pomegranate orchards, it is expected to not only improve harvesting efficiency but also provide technical support for other intelligent orchard tasks, contributing to the advancement of smart agriculture. See

Figure 16 for details.

Although the proposed model achieves excellent performance in pomegranate detection and lightweight deployment, it has certain limitations. First, its performance degrades under extreme weather (heavy rain, fog), as the feature extraction modules are less robust to image contrast changes and noise. Second, it lacks adaptability to pomegranates in different growth stages (e.g., green young fruits), due to insufficient training samples covering diverse growth stages. Third, real-time performance drops slightly in dense target scenarios.

Future work will address these limitations: (1) Enhance robustness to extreme weather by introducing image preprocessing modules and expanding datasets with simulated extreme weather samples. (2) Collect multi-growth stage pomegranate data and optimize the network to improve cross-stage detection ability. (3) Optimize the ASF module to enhance real-time performance in dense target scenarios.

5. Conclusions

To tackle the challenges of insufficient detection accuracy and high model complexity in traditional object detection models for pomegranate detection, this paper presents an improved lightweight detection model based on RT-DETR R18. By incorporating the FasterNet feature enhancement module, the ASF adaptive spatial fusion module, the Slimneck lightweight structure, and the Lamp pruning strategy, the model achieves notable advancements in both detection performance and computational efficiency. Experimental results reveal that the proposed model achieves mAP50 and mAP50–95 scores of 0.928 and 0.632, respectively, marking a 4.7% improvement in both metrics compared to the original RT-DETR R18 model. Additionally, the parameter count and computational complexity are reduced by approximately 30.9% and 39.2%, respectively. These results demonstrate that the proposed enhancements successfully reduce the model’s size and complexity while maintaining high detection accuracy, underscoring its practical value and potential for broader deployment in real-world pomegranate detection tasks.

However, this study still has certain limitations. Firstly, the model is mainly trained and validated in pomegranate orchard scenes under natural lighting conditions, and its adaptability to extreme lighting, severe occlusion, or dense overlapping fruit scenarios needs further verification. Secondly, although the pruned model achieves a good balance between accuracy and efficiency, there may still be a risk of performance degradation when applied to larger-scale datasets or detection tasks of different fruit types. In addition, the model has not undergone actual deployment testing on mobile hardware or embedded devices, and its stability and latency performance in real-time detection scenarios require further evaluation.

Future research work will be carried out in the following directions: Firstly, further optimize the fusion mechanism between the Transformer structure and convolutional features, and introduce a dynamic feature selection module to enhance the model’s adaptive ability to complex scenes. Secondly, combine knowledge distillation with multi-modal information (such as RGB-Depth or hyperspectral data) to further strengthen the model’s feature expression capability. Thirdly, explore the embedded deployment of the model in actual orchard picking robots and intelligent grading systems, to realize a high-precision, low-latency, and implementable intelligent fruit and vegetable detection solution.