Abstract

Black pepper (Piper nigrum) stands out as one of the most valued spices in the global market, with Brazil occupying a strategic position in production, especially in Espírito Santo, being the largest producing state in the country. This study analyzes the economic feasibility of implementing raffia in black pepper crops, focusing on reducing post-harvest losses and optimizing operational costs and environmental sustainability. Data were collected in black pepper crops, specifically at Fazenda Duas Barras, in the city of Pinheiros, ES, Brazil. Two cultivation systems were designed and compared: The traditional black pepper cultivation system without the implementation of raffia blanket, with an average production of 4000 kg ha−1 and harvest cost of USD 7433.63 ha−1; and the black pepper cultivation system with the implementation of raffia blanket, production increased to 4500 kg ha−1, with a 60% reduction in harvest cost. Using established financial indicators (NPV, IRR, and Payback), it is demonstrated that the investment presents a return in 2.4 years, with an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 51% and a Net Present Value (NPV) of USD 59,150.44 ha−1 year−1. The sensitivity analysis shows economic resilience even in adverse scenarios, consolidating the technology as a viable alternative for small and medium-sized producers.

1. Introduction

Black pepper (Piper nigrum) stands out as one of the most valued spices in the global market, with Brazil occupying a strategic position in its production (Food and Agriculture Organization) [1]. Black pepper is one of the most consumed condiments in the gastronomic culture of several countries. Brazil stands out among the largest producers and exporters of this spice, with the state of Espírito Santo being the largest producer in the country [2].

The black pepper production chain plays an important role in the employment of the workforce, income generation, and socioeconomic development of the northern region of the state [3]. These same authors highlight that the chain is composed of small and medium-sized farmers who sell their production to cooperatives or private companies, which in turn sell the product on the international market. However, challenges such as average losses of 10% during harvest [4] and high labor costs compromise the profitability of the sector.

In this scenario, innovative technologies, such as raffia, emerge as solutions to harmonize operational efficiency and environmental sustainability [5]. Mulching with plastic film in medium-textured soils provides a low water footprint, reduces the effect of irrigation level on soil water availability, and maintains available water at depletion levels suitable for irrigation management [6].

The application of soil mulch has been widely used to increase agricultural production; however, few research studies have comprehensively evaluated the use of blankets as soil mulch and its effects on water savings and crop coefficients [7].

Economic viability is one of the most important factors to be considered when making decisions for investments in irrigated agriculture. Thus, the assessment of the costs and benefits involved in the implementation and operation of innovative and technological systems can provide valuable information for farmers [8].

This study aims to economically evaluate the adoption of raffia implementation technology, provide support for strategic decisions, and contribute to the technical literature of the agricultural sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The data were collected from black pepper plantations in the northern state of Espírito Santo, the main black pepper-producing region in Brazil, specifically at Fazenda Duas Barras, in the city of Pinheiros, ES, at an altitude of 50 m. The soil has a medium sandy texture. According to the Köppen classification system, it is classified as “Am”, that is, a rainy tropical monsoon climate. This means that the region has an intense rainy season, usually in the summer, followed by a dry season, with high temperatures throughout the year.

Two cultivation systems were designed and compared: The traditional black pepper cultivation system without the implementation of raffia mulch, with an average production of 4000 kg ha−1, a harvesting cost of USD 7433.63 ha−1; and the black pepper cultivation system with the implementation of raffia mulch: Production increased to 4500 kg ha−1, 60% reduction in harvesting costs. Productivity data were obtained through: Direct Monitoring: Weighing of fruits harvested in 10 cultivation lines with raffia and 10 lines without raffia (same plot, soil, and management). Variable Control: All plots had 3-year-old pepper plants, spacing 2.5 m × 2.5 m, and drip irrigation.

The raffia mulch is made of woven polyethylene (canvas type), is resistant, and is 0.5 mm thick. It has been treated to resist ultraviolet (UV) rays. These rays are electromagnetic radiation emitted by the sun that can be harmful to the polyethylene in the mulch. This is why the surface of the mulch is treated chemically to increase its longevity. The manufacturer therefore provides a factory warranty of at least 8 years.

For the calculations, the mulch was designed to be installed on an already established black pepper crop, 3 years old, with a 2.0% slope in the ground. The mulch, 105 cm wide, was stretched across the planting line. One mulch was installed on the right side of the planting line and another on the left side, glued to the stem of the black pepper plants and secured with 6 staples on each plant. In this way, a 210 cm wide strip of raffia mulch was installed in each black pepper planting line (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Black pepper: (A–C)—crop with raffia blanket implanted in the pantio line. (D–F)—cultivation with bare soil.

The costs of implementing the technology and infrastructure, inputs, labor costs, and electricity, among others, were obtained from specialized local commercial establishments, and price surveys were conducted on-site in the city of Pinheiros, ES. In addition, the data required for implementing the crop were obtained from the national reference website for production costs [9].

An economic feasibility analysis was performed by simulation, using the AmazonSaf spreadsheet [10]. Production costs were estimated using approximate values in dollars (USD). Value in reais converted to dollars on 29 April 2025, where the dollar was worth R$5.65. Considering a cultivated area of 1 ha of black pepper. The detailed production cost of black pepper in 2024 for the study region was based on values provided by CONAB [9].

2.2. Economic Modeling

For feasibility calculations, the methodology presented by Alves Sales [11] was used. The indicator that assessed the viability of the investment was the profitability indicator, referring to gross revenue (RE, USD), which was determined by Equation (1):

where PRO is the production in the study area (kg) and PRE is the sales price (USD). The net present value (NPV), defined as the difference between the present value of benefits and the present value of costs [12], was determined by Equation (2):

where ‘n’ is the longevity of the project; ‘j’, is the period in which the cash flow occurred; ‘CF’, is the cash flow balance; and ‘i’, is the interest rate of 12% per year.

The internal rate of return (IRR) determined by Equation (3) is the potential for the project to generate returns [12]:

where r is the IRR.

The payback period is the time it takes for the project to return the invested capital [13].

The sale prices of black pepper were calculated based on market value surveys from the last 10 years (between 2014 and 2024) [9]. The estimated average price of black pepper (or Piper nigrum) for 2025 may vary between USD 3.54 and USD 4.42 per kg. This value may be higher in some regions, depending on the quality of production and market conditions. An estimate was made of the average cost per hectare for herbicide and adjuvant, irrigation (cost of irrigated mm), harvesting labor, labor, and tractor operating cost to obtain the total cost of herbicide application per hectare and the cost of the initial blanket.

Fixed assumptions: Value of raffia blanket: (installation + material) of USD 4424.78 ha−1, with a useful life of 8 years. Production (with blanket) 4500 kg ha−1 year−1 of black pepper. Operating costs USD 5243.98 ha−1 year−1. Discount rate 12% per year. The assessment considers the raffia blanket as an isolated investment in already productive crops, with flows calculated by the difference between systems with and without the technology. For perennial crops, incremental analyses are the gold standard when the technology is not tied to the initial planting [8].

2.3. Weighted Average Capital Cost

Weighted Average Capital Cost (WACC) was calculated considering real financing conditions for small and medium-sized producers in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, where black pepper growers access subsidized rural credit at 8% per year (National Program for Strengthening Family Farming—Pronaf) [14]. The capital structure assumes 55% equity (cost of 15.5% per year) referring to the Selic rate (base year 2024) = 11.5% (Central Bank of Brazil Copom) [15] + Agricultural Risk Premium = 4% (Proagro) [16] and 45% debt (8% per year), with an effective income tax rate of 8% for family farming [14]. The resulting WACC is summarized in Equation (4):

where E/V = 55% (Equity (equity)), Re = 15.5% (cost of equity), D/V= 45% (debt), Rd= 8% (cost of debt before taxes), Tc= 8% (income tax rate).

Adopting the corresponding values in Equation (4), we have:

* Value rounded to 12% as a conservative estimate.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Financial Indicators

The results show that, even with the large variation in the investment value in the implementation of raffia of USD 4424.78, there was a decrease in the average total production costs (Table 1) in the cost of harvesting, cost of herbicides, and cost of irrigation. This fact reveals the viability of the enterprise (Table 2), with an average profitability (NPV) of USD 59,150.44 ha−1 year−1.

Table 1.

Economic values of the investment in implementing Raffia in a black pepper crop.

Table 2.

Economic indicators of investment in different systems, with and without raffia, in a black pepper crop.

3.2. Sensitivity Analysis: Impact of Pepper Price on Project Viability

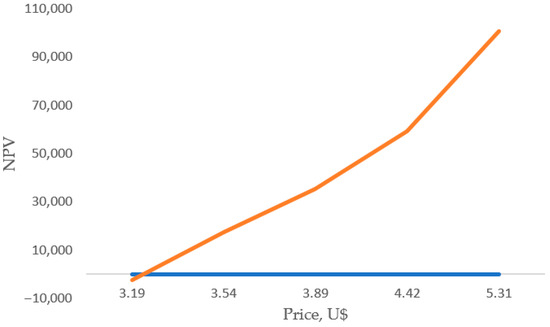

To assess the robustness of the raffia investment, a sensitivity analysis was performed by varying the price of black pepper while keeping the cost of the raffia fixed at USD 4424.78 ha−1. The results are presented below in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Variation in net present value (NPV) as a function of the price of black pepper.

According to the analysis of Figure 2, it is observed that if the price of black pepper drops to a level below USD3.22 kg−1 of product, the feasibility study becomes economically unfeasible.

The sensitivity of the NPV to variations in the price of black pepper is elastic. Increases in the price of black pepper have a positive and more than proportional impact on the value of the NPV, i.e., a 10% increase in the price of pepper results, on average, in a 57% increase in the NPV, as can be seen in Figure 1.

3.3. Payback Calculation

The calculation of the return on investment time for implementing raffia was carried out and is presented below in Table 3.

Table 3.

Payback indicator for the investment in implementing Raffia in a black pepper crop.

Table 3 shows that the raffia investment is viable and has a return in 2.4 years after the investment. To complement the study, a robust sensitivity analysis was presented, evaluating how variations in the price of black pepper and the cost of raffia impact the viability of the project. The results are summarized below in Table 4.

Table 4.

Economic indicators of investment with variations in the price of black pepper and the cost of raffia.

4. Discussion

Initially, the focus of this study was to explore the use of raffia in black pepper crops to reduce harvest losses. Field analysis was carried out, and an average loss of around 300 to 500 g of black pepper per plant was estimated. This is a considerable amount, a lot in terms of production per hectare. So, these harvest losses are around 10% of the pepper produced. Thus, with the high prices of black pepper in recent years, this has resulted in a very significant amount of losses. The financial return is very interesting with the implementation of raffia, as losses are reduced to practically zero during harvest. Figure 3 shows the cultivation of black pepper with dried fruits fallen on the raffia blanket implanted in the pantio line. Highlighting the ease of harvesting fallen pepper.

Figure 3.

Cultivation of black pepper with dried fruits falling on the raffia blanket implanted in the pantio line.

Post-harvest losses are becoming a major problem worldwide and are predominantly serious in developing countries [18]. This same author highlights that finding ways to control post-harvest losses is important, as losses reduce agricultural income by more than 15% for approximately 480 million small farmers in the world. In addition to the losses of pepper about the harvest, some other benefits of using raffia were discovered, related to the reduction in labor in the harvest. With the field surveys, there was a deficit in 33.3% less labor required for the harvest of black pepper crops with the implementation of raffia. These indicators point to an increase in profit in two ways: in labor and in the reduction in losses.

However, there were other benefits related to the better optimization of irrigation water, which came, so to speak, as a side effect of the implementation of raffia. The consumption of water to keep the soil moist for longer is lower with the raffia, preventing the soil from becoming exposed. This reduces the proliferation of weeds, thus reducing the number of weeds in the crop, consequently reducing competition for water. It also reduces or practically eliminates the incidence of direct sunlight on the soil. This causes the temperature of the soil, in general, to decrease and prevents the water that is on the surface of the soil, in the upper layers, from evaporating. It is a question of sustainability, using less water, and consuming less water resources in a region that has experienced drought problems in recent years. The use of black plastic mulch with drip irrigation in medium-textured soil saves up to 152 L of water per kg of fruit and increases productivity by up to 34%, replenishing crop evapotranspiration with each irrigation event [6].

Mulching is another promising practice to mitigate the effects of water stress in environments and protect bare soil, providing benefits such as weed control and deposition of organic matter, mitigating the impact of solar radiation, improving soil moisture distribution, and reducing water losses through evaporation [19,20,21].

Without a doubt, thinking from the point of view of sustainability and food safety, we are presenting a study of a pepper that will require much less use of pesticides, especially herbicides. In traditional black pepper planting, herbicide control is performed over the entire area. However, where there is a raffia blanket in the pepper planting line, where the pepper bunch will fall, where the pepper is, and where the pepper will be harvested, there was no herbicide application. There was no need for an application because there was no infestation of weeds growing in the 2.1 m wide strip of the raffia blanket. There is practically no competition from invasive plants with the crop.

This is a crop that is naturally more organic. It is a cleaner crop in this sense. It is difficult for the producer to find alternatives to be able to deal with the problems they have in the sanitary cultivation of black pepper. With the implementation of the raffia blanket, basically, the use of pesticides in the crop is biological pesticides, with biologically active ingredients, with biological microorganisms. In this sense, raffia also helps because it improves the performance of biological agents. Therefore, the producer, as an alternative, has biological products, which are living microorganisms, based on algae, fungi, or bacteria, that act in the soil in favor of the plant. They act in the soil and in the plant itself as well. These organisms need water and more suitable temperatures for them to grow and reproduce. So, when the producer applies this type of living being to the soil, it needs these ideal conditions to be able to grow and multiply. With the raffia blanket, you have better conditions for the microorganisms.

Bioinputs have gained prominence in agriculture due to their growth regulators (e.g., auxins, cytokinins) and bioactive compounds that stimulate germination and root development [22]. Seaweed extracts are very versatile in their forms of use and can be used in seed treatment, foliar application, fertigation, or various combinations of these methods [23].

The producer has more moisture in the soil, and the irrigation is distributed under the raffia blanket. You permeate more moisture into the soil in the most superficial layers, which is where the microorganisms will act, for a longer period. Therefore, you have more moisture and a lower and better-distributed temperature. Thus, there is a greater chance of the successful use of these biologicals having an effect. The rural producer has a cleaner crop in terms of sanitation, with less need for weeding, and also has a favorable condition for the harvester, who harvests not only the pepper that is stuck to the plant but also the pepper that falls to the ground. In crops without the installation of a raffia blanket, the crop has been applied with herbicide, and this will come into contact with the pepper that falls to the ground. In a way, there is a chance of contamination by these pesticide residues. Naturally, a harvest in a crop with raffia is more septic from the point of view of pesticide contamination, without a shadow of a doubt. In crops without raffia, it is recommended to collect separate fruits that have fallen to the ground, clean them, and remove excess moisture before mixing them with the others [24].

Studies have already addressed this issue. Considering the economic impact of contamination, the potential risk to public health, and the influence on the quality of black pepper, the authors, Vinha [25], aimed to evaluate the hygienic-sanitary quality of black pepper subjected to different methods and identified the causes of the loss of quality during processing on rural properties in northern Espírito Santo.

The adoption of raffia demonstrated economic superiority over the traditional system, with a 46% increase in profitability. The elimination of the use of herbicides and the 20% reduction in water consumption are in line with the principles of sustainable agriculture (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) [26]. Comparatively, studies on coffee crops recorded an IRR of 40% with similar technologies [17], validating the effectiveness of raffia.

The high IRR (51%) reflects the combination of three main factors: a dramatic reduction in post-harvest losses (from 10% to ≈0%), savings of 60% in harvesting costs, elimination of herbicide expenses. These cumulative benefits justify the IRR above the Brazilian basic interest rate (12%), common in agricultural projects with high technological efficiency [17]. The 2.4-year payback period is below the average for conventional agricultural projects (3–5 years), but is expected for technologies that impact multiple production variables simultaneously. In comparison: Drip irrigation systems for fruit trees: Average payback of 3.8 years [8]. Mulching adoption for coffee: Payback of 2.1 years [17]. The rapid return is due to the synergy between direct (productivity) and indirect (reduced operating costs) gains.

Sensitivity analysis proves that even in scenarios with higher WACCs, given the high costs, the project’s IRR (51%) remains 3.6 times the cost of capital. It is noteworthy that more than 60% of black pepper producers in the state of Espírito Santo, Brazil, are classified as family farmers [27], accessing credit at 8% per year and an income tax rate of 8%, a scenario in which the WACC falls to 12.00%. This condition reinforces financial viability for most producers.

For raffia sizing, the investment of USD 4424.78 per hectare, already counting the cost of raffia and installation, represents a significant cost, but it is diluted within 2.4 years after the investment. Due to the benefits already mentioned, there is a reduction in pepper loss, water savings, a more sustainable product, of better quality, with less use of herbicides, increased profitability, and a reduction in labor costs in the field. Labor relations in the countryside are governed by the Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT) and Law No. 5889/73, which deals specifically with rural work [28]. Investment in technologies in the field that improve crop quality, increase the income of rural producers, and generate jobs in the field [8].

The difference in the crop planted with raffia blanket is huge because there is a reduction in labor costs, with a more optimized harvest, easier without the presence of weeds to get in the way, where the harvester will not have access to the ground, there will be no dirt, soil, stones, and less risk of poisonous animals. The worker performs his task more optimistically, more satisfied, and cleaner. Better quality for the consumer, a healthier pepper, to be placed on the consumer’s table. So the difference is huge, and it is very satisfactory.

Study Limitations

Volatility of pepper prices in international markets.

Difficulty in accessing credit for small producers for the initial purchase of raffia blankets.

The study does not adjust prices for inflation, as it focuses on real cash flows received by producers. Analyses with deflation may be useful for intertemporal comparisons, but are beyond the operational scope of this work.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of raffia in black pepper plantations is a viable investment, with a return in 2.4 years and significant environmental benefits.

Recommended: Implementation of public policies to subsidize the initial acquisition of the technology. Technical training programs to maximize operational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T.d.O. and C.H.A.A.; methodology, J.T.d.O. and S.C.T.; validation, J.T.d.O., K.B.G.S., F.F.d.C., S.C.T. and C.H.A.A.; formal analysis, J.T.d.O. and K.B.G.S.; investigation, J.T.d.O., K.B.G.S., F.F.d.C., S.C.T. and C.H.A.A.; resources, J.T.d.O.; data curation, C.H.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.T.d.O.; writing—review and editing, J.T.d.O. and F.F.d.C.; visualization, J.T.d.O., K.B.G.S., F.F.d.C., S.C.T. and C.H.A.A.; supervision, K.B.G.S.; project administration, J.T.d.O., K.B.G.S., F.F.d.C., S.C.T. and C.H.A.A.; funding acquisition, J.T.d.O. and F.F.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Brazil (CAPES), Finance Code 001, and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil (CNPq), Process 308769/2022-8.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Agriculture Engineering (DEA) and the Graduate Program in Agricultural Engineering (PPGEA) of the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) for supporting the researchers. UFMS—Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul. Fundect—Foundation for Supporting Education, Science and Technology of the State of Mato Grosso do Sul.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization. Statistical Yearbook 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; 380p, Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0c372c04-8b29-4093-bba6-8674b1d237c7/content (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Machado, T.M.F.; Piccolo, M.D.P.; Maradini Filho, A.M.; Silva, M.B.; Oliveira, M.D.V.; Santos Junior, A.C.; Santos, Y.I.C.D. Qualidade de pimenta-do-reino obtida de propriedades rurais do norte do Espírito Santo. Avanços Em Ciência E Tecnol. De Aliment. 2021, 4, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, P.; Lima, I.D.M.; Costa, N.; Vinha, M.; Cassini, S. Influência do Processo de Secagem na Qualidade Microbiológica da Pimenta-do-Reino. In Proceedings of the Anais 2021: Congresso Capixaba de Pesquisa Agropecuária [Recurso Eletrônico] (Incaper, Documentos, 289), Virtually, 17–19 November 2021; Incaper: Vitória, ES, Brazil, 2021. Available online: https://biblioteca.incaper.es.gov.br/digital/bitstream/item/4355/1/Anais-CCPA-205a208.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Souza, A.B.; Santos, C.D.; Lima, E.F. Perdas pós-colheita em pimenta-do-reino: Análise e mitigação. Rev. Agronegócios 2021, 18, 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, R.M.D.; Cunha, F.F.D.; Silva, G.H.D.; Andrade, L.M.; Morais, C.V.D.; Ferreira, P.M.O.; Oliveira, R.A.D. Evapotranspiration and crop coefficients of Italian zucchini cultivated with recycled paper as mulch. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, E.F.; Santos, D.L.; de Lima, L.W.F.; Castricini, A.; Barros, D.L.; Filgueiras, R.; da Cunha, F.F. Water regimes on soil covered with plastic film mulch and relationships with soil water availability, yield, and water use efficiency of papaya trees. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 269, 107709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, E.M.; da Silva, G.H.; Guimarães, G.F.C.; Vital, T.N.B.; Vieira, J.H.; da Silveira, F.A.; da Cunha, F.F. Evapotranspiration and crop coefficient of Physalis peruviana cultivated with recycled paper as mulch. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 320, 112212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, L.P.; Oliveira, J.T.D.; Baio, F.H.; Oliveira, R.A.D.; Cunha, F.F.D. Economic feasibility of center pivot irrigation with corn, cowpea, and soybean crops in sandy soils. Eng. Agrícola 2024, 44, e20230137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAB Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. Serie Histórica—Custos de Pimenta do Reino de 2008 a 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/conab/pt-br/atuacao/informacoes-agropecuarias/custos-de-producao/arquivos-custo-de-producao/agricolas/serie-historica-custos-pimenta-do-reino-2008-a-2024/view (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Arco-Verde, M.F.; Amaro, G. Cálculo de Indicadores Financeiros Para Sistemas Agroflorestais. Boa Vista: Embrapa Roraima, 2014. 36p. (Documentos/Embrapa Roraima, 57). CDD: 332. Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1033617/1/N57DOC159CORRIGIDO.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Alves Sales, J.; Alves Junior, J.; Pereira, R.M.; Rodriguez, W.D.M.; Casaroli, D.; Evangelista, A.W.P. Viabilidade econômica da irrigação por pivô central nas culturas de soja, milho e tomate. Pesqui. Agropecuária Pernambucana 2018, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzone, J.A.; Andrade Júnior, A.S. Planejamento de Irrigação: Análise de Decisão de Investimento; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2005; 627p, Available online: https://repositorio.usp.br/item/001653907 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Puccini, E.C. Matemática Financeira e Análise de Investimentos, 3rd ed.; Florianópolis: Departamento de Ciências da Administração/UFSC: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2016; 132p. Available online: https://educapes.capes.gov.br/bitstream/capes/643232/2/Matem%C3%A1tica%20Financeira%20e%20An%C3%A1lise%20de%20Investimentos.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Pronaf—Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar. Crédito Rural: Encargos Financeiros e Limites de Crédito. Financial Charges for Financing Under the National Program to Strengthen Family Farming—Pronaf (Res CMN 5.234 art 6º; Res CMN 5.235 art 3º). 2025. Available online: https://www3.bcb.gov.br/mcr/manual/0902177186865c4b.htm (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Copom—Comitê de Política Monetária. Taxas de Juros Básicas—Histórico. History of Interest Rates Set by Copom and Evolution of the Selic Rate. 2025. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/controleinflacao/historicotaxasjuros (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Proagro—Programa de Garantia da Atividade Agropecuária. Rural Credit and Proagro Bulletin. 2024. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/content/publicacoes/boletimderop/Boletim%20Derop%20-%20novembro2024.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Pereira, R.S.; Costa, J.M.; Alves, F.R. Viabilidade econômica do mulching em cultivos de café. Rev. Bras. Agric. Sustentável 2019, 12, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Osabohien, R. Soil technology and post-harvest losses in Nigeria. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2024, 14, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.N.; Pinto, J.R.; Ripoll, M.A.; Sánchez-Miranda, A.; Navarro, F.B. Impact of straw and rock-fragment mulches on soil moisture and early growth of holm oaks in a semiarid area. Catena 2017, 152, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.K.M.N.; Jardim, A.M.D.R.F.; Araújo Júnior, G.D.N.; de Souza, C.A.A.; Leite, R.M.C.; da Silva, G.I.N.; da Silva, T.G.F. Uma abordagem sobre práticas agrícolas resilientes para maximização sustentável dos sistemas de produção no semiárido brasileiro. Rev. Bras. Geogr. Física 2022, 15, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, R.L.S.; Nunes, J.A.; de Carvalho Leal, L.Y.; dos Santos, M.A.; de Assunção Montenegro, A.A.; de Souza, E.R. Dinâmica de trocas gasosas e potencial hídrico foliar em sorgo consorciado com palma e irrigado com água de reuso. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2024, 54, e79527. [Google Scholar]

- Trovato, V.W. Qualidade de Mudas de Peltophorum Dubium (Spreng.) Taub.: Sombreamento, Extrato de Algas, Silício e Silicato de Potássio. 2022. Available online: https://files.ufgd.edu.br/arquivos/arquivos/78/MESTRADO-DOUTORADO-AGRONOMIA/Teses%20Defendidas/Tese_Viviane%20Wruck%20Trovato_Final.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Carvalho, R.S.; de Santana, J.O.; da Paz, C.D.; Oliveira, R.A.O.; da Cruz, A.R.; de Souza, M.J.; de Sena Gomes, M.C. Desempenho de mudas de tomate com diferentes doses de extrato de algas marinhas. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2024, 22, e8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundino, W.; Lima, I.D.M.; Ventura, J.; Dias, R.; Trevizani, J.; Vinha, M. Pimenta-do-Reino: Boas Práticas na Colheita e Pós-Colheita; Documentos n° 274; Incaper: Espírito Santo, Brazil, 2020; ISSN 1519-2059. Available online: www.incaper.es.gov.br (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Vinha, M.B.; Costa, N.S.; Lima, I.M.; Antunes, P.W.P.; Cassini, S.T.A.; Influência do Processo de Secagem na Qualidade Microbiológica da Pimenta-do-Reino. Congresso Capixaba de Pesquisa Agropecuária—CCPA 2021. 17 a 19 de Novembro de 2021—Congresso Online. Available online: https://www.sidalc.net/search/Record/oai:https:--biblioteca.incaper.es.gov.br:item-4355/Description (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- IPCC—Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Incaper—Instituto Capixaba de Pesquisa, Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural. Incaper Handles More than 60% of Registrations in the Family Farming Registry in Espírito Santo. 2024. Available online: https://incaper.es.gov.br/Not%C3%ADcia/incaper-faz-mais-de-60-das-inscricoes-no-cadastro-da-agricultura-familiar-no-espirito-santo (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- TRT-4—Tribunal Regional do Trabalho da 4ª Região-RS. Rural Labor Handbook. 4ª Edição. 40p. 2024. Available online: https://www.trt4.jus.br/portais/media/3020338/Cartilha%20Trabalhador%20Rural%20-%20atualizado%201%20ago.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).