Plant Species Diversity and the Interconnection of Ritual Beliefs and Local Horticulture in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

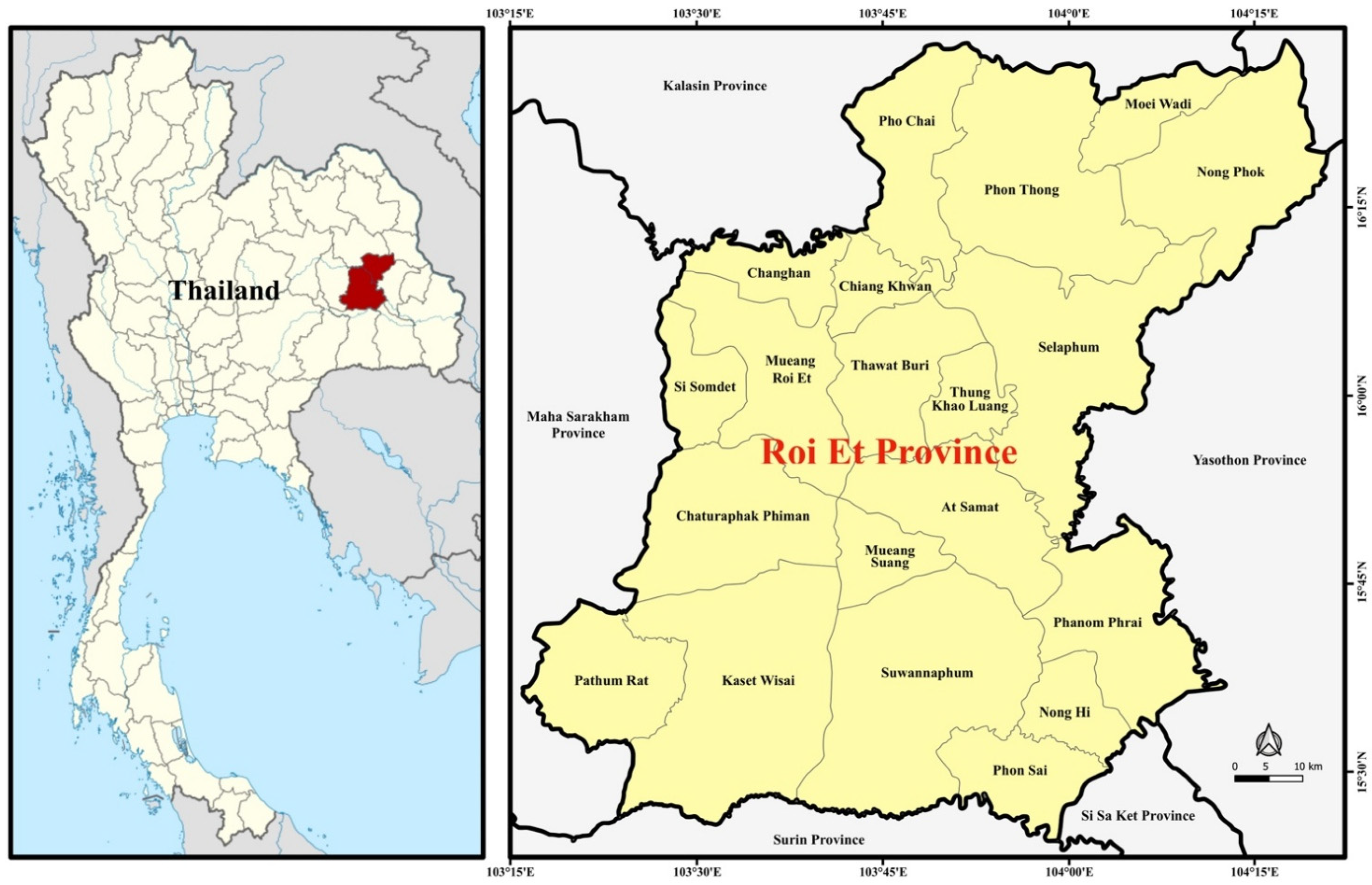

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Plants Identification

2.2.1. Plant Diversity Used in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies

2.2.2. Cultural Significance Index (CSI)

2.2.3. Species Use Value (SUV)

2.2.4. Genera Use Value (GUV)

2.2.5. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

2.2.6. Plants Used in the Heet Sip Song Ceremonies (Monthly Breakdown)

2.3. Conservation Status

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Cultural Significance Index (CSI)

2.4.2. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

2.4.3. Species Use Value (SUV)

2.4.4. Genera Use Value (GUV)

3. Results

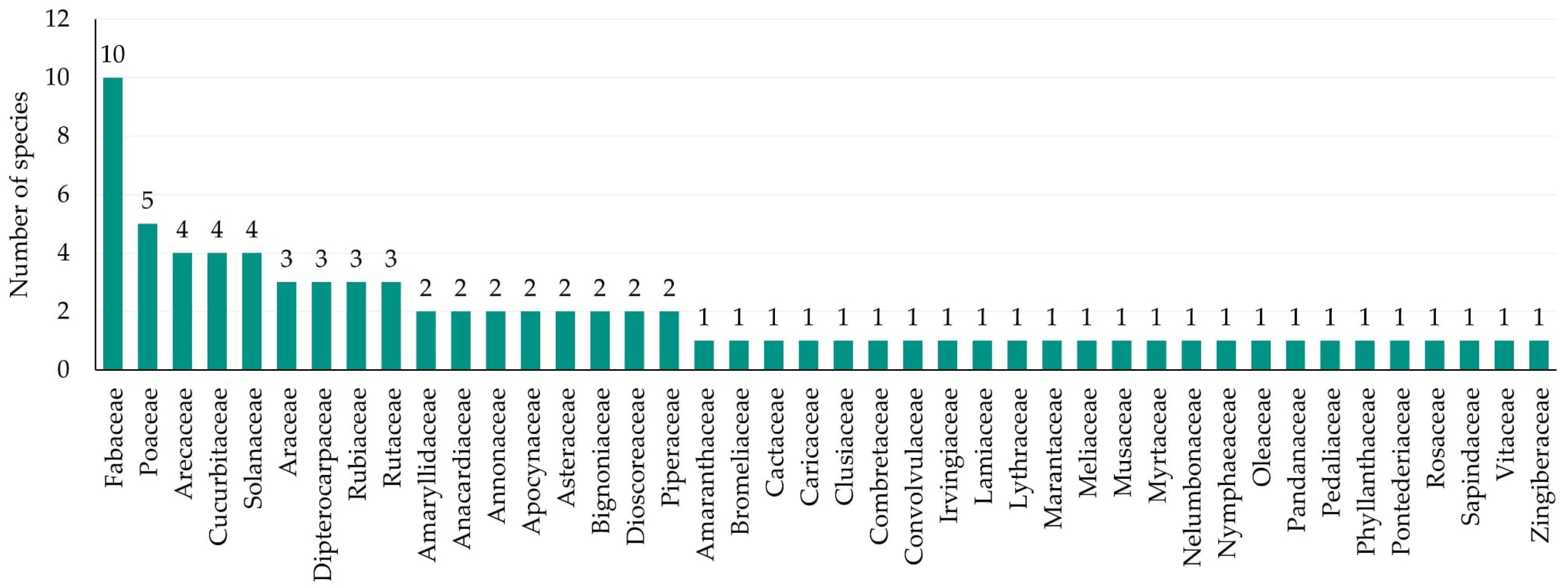

3.1. Plant Diversity Used in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies

3.2. Cultural Significance Index (CSI) of Plant Species Used in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies

3.3. Species Use Value (SUV) of Plant Species Used in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies

3.4. Genera Use Value (GUV) of Plant Species Used in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies

3.5. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of Plant Species Used in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies

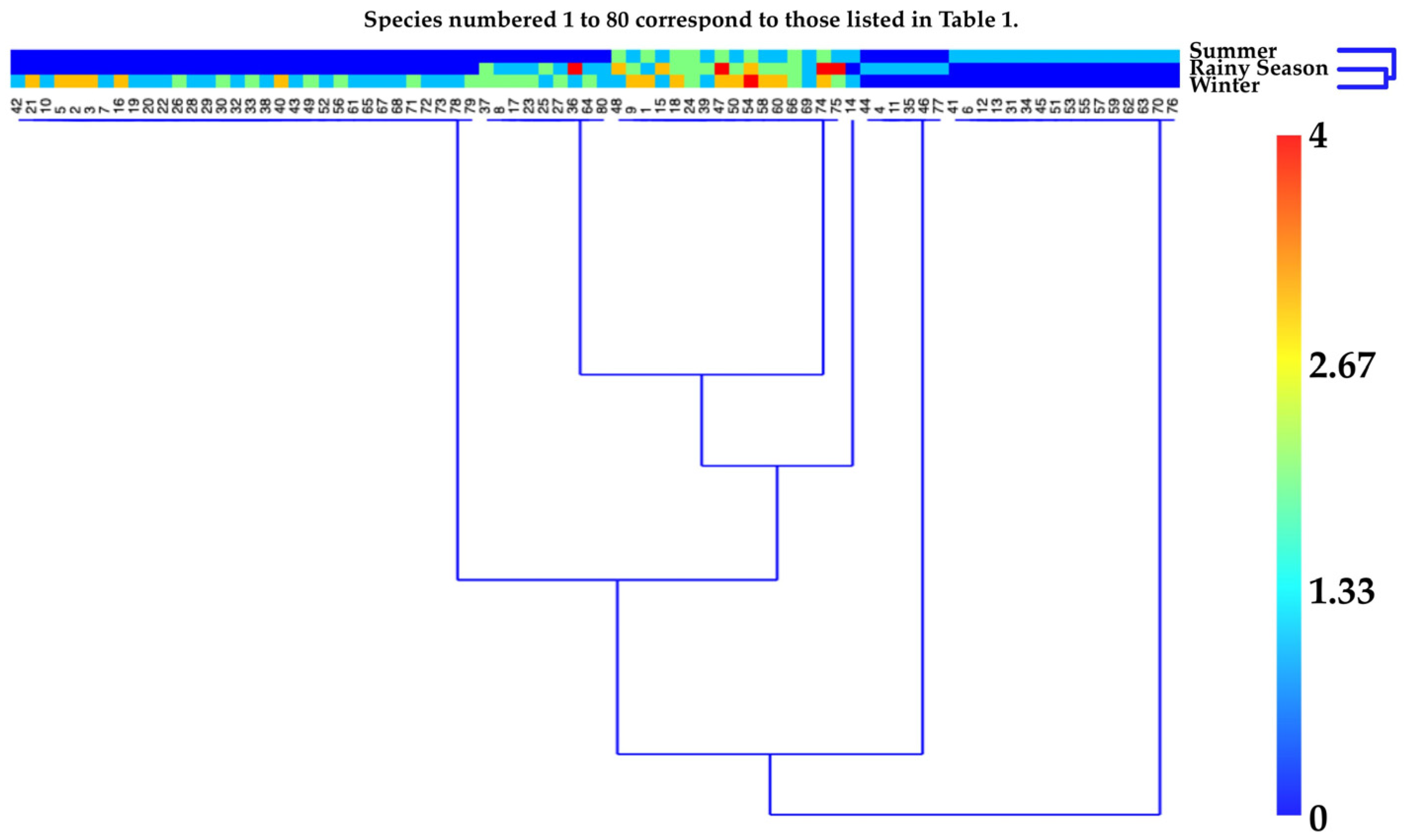

3.6. Plants Used in the Heet Sip Song Ceremonies in Roi Et Province

3.6.1. Plants Used in Bun Khao Kam (Month 1)

3.6.2. Plants Used in Bun Khun Lan (Month 2)

3.6.3. Plants Used in Bun Khao Jee (Month 3)

3.6.4. Plants Used in Bun Pha Wet (Month 4)

3.6.5. Plants Used in Bun Songkran (Month 5)

3.6.6. Plants Used in Bun Bang Fai (Month 6)

3.6.7. Plants Used in Bun Samha (Month 7)

3.6.8. Plants Used in Bun Khao Phansa (Month 8)

3.6.9. Plants Used in Bun Khao Pradap Din (Month 9)

3.6.10. Plants Used in Bun Khao Sak (Month 10)

3.6.11. Plants Used in Bun Ok Phansa (Month 11)

3.6.12. Plants Used in Bun Kathin (Month 12)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winkelman, M.J. An ethnological analogy and biogenetic model for interpretation of religion and ritual in the past. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2022, 29, 335–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakhun, P.; Mahakhun, N. Plants in Thai way of living: Plants in ceremonies related to life (house building, marriage, birth, topknot-cutting ceremony, novice and monk ordinations, and death). J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Phonpho, S. The relationship of lotus to Thai lifestyle in terms of religion, arts and tradition. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2014, 10, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, D.M. Landscapes of the law: Injury, remedy, and social change in Thailand. Law Soc. Rev. 2009, 43, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saihong, P. Storytellers and storytelling in Northeast Thailand. Storytell. Self Soc. 2008, 4, 20–35. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15505340701778530 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Ma, X.; Luo, D.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, G. Ethnobotanical study on ritual plants used by Hani People in Yunnan, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yan, C.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, R.; He, L.; Zheng, W. Ornamental plants associated with buddhist figures in China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfa, D.M.; Yudiyanto; Hakim, N.; Wakhidah, A.Z. Ethnobiology study of Begawi traditional ceremony by Pepadun Community in Buyut Ilir Village, Central Lampung, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 2768–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigme, Y.K. An ethnobotanical study of plants used in socio-religious activities in Bhutan. Asian J. Ethnobiol. 2022, 5, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S. Documentation of the plants used in different Hindu rituals in Uttarakhand, India. Asian J. Ethnobiol. 2022, 5, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambey, R.; Lubis, A.S.J. Ethnobotany of plants used in traditional ceremonies in Tanjung Botung Village, North Sumatra, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 977, 012098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonma, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P. Biogeography, conservation status, and traditional uses of Zingiberaceae in Saraburi Province, Thailand, with Kaempferia chaveerachiae sp. nov. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudchaleaw, S.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Sungkaew, S. Species diversity and traditional utilization of bamboos (Poaceae) by the Phu Thai Ethnic Group in Northeastern Thailand. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 2261–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamngon, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Junsongduang, A. Ethnobotany of the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Pho Chai District, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 8, 6152–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitpromma, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Boonma, T. Diversity, traditional uses, economic values, and conservation status of Zingiberaceae in Kalasin Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, I. Traditional ecological knowledge and its role in biodiversity conservation: A systematic review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1164900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Pumijumnong, N.; Hatano, R. Predicting local-scale impact of climate change on rice yield and soil organic carbon sequestration: A case study in Roi Et Province, Northeast Thailand. Agric. Syst. 2018, 164, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POWO. Plant of the World Online, Facillitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- IUCN. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria Version 16. 2024. Available online: https://nc.iucnredlist.org/redlist/content/attachment_files/RedListGuidelines.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Turner, N.J. “The Importance of a Rose”: Evaluating the cultural significance of Plants in Thompson and Lillooet Interior Salish. Am. Anthropol. 1988, 90, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural importance indices: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain)1. Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.; Gallaher, T. Importance indices in ethnobotany. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, A. Sacred plants and their miraculous or healing properties. Preprints 2024, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Hu, G.; Ranjitkar, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. The implications of ritual practices and ritual plant uses on nature conservation: A case study among the Naxi in Yunnan Province, Southwest China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.; Cross, R. The origins of botanic gardens and their relation to plant science, with special reference to horticultural botany and cultivated plant taxonomy. Muelleria 2017, 35, 43–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrhmoun, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Pieroni, A. Phylogenetic perspectives and ethnobotanical insights on wild edible plants of the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa. Foods 2025, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indra, G.; Mukhtar, E.; Syamsuardi, S.; Chairul, C.; Mansyurdin, M. Plant species composition and diversity in traditional agroforestry landscapes on Siberut Island, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2024, 25, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Hein, K.Z.; Appamaraka, S.; Maknoi, C.; Souladeth, P.; Koompoot, K.; Sonthongphithak, P.; Boonma, T.; Jitpromma, T. Diversity, ethnobotany, and horticultural potential of local vegetables in Chai Chumphol Temple Community Market, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Agarwal, R. Saccharum officinarum (Sweet Salt)—Invention to domestication. Shodhshauryam Int. Sci. Ref. Res. J. 2024, 7, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, N.L.; Tshisikhawe, M.P. Hierarchies of knowledge: Ethnobotanical knowledge, practices and beliefs of the Vhavenda in South Africa for Biodiversity Conservation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwu, M.C.; Ojo, A.O.; Osawaru, M.E. Quantitative Ethnobotany of Afenmai People of Southern Nigeria: An Assessment of Their Crop Utilization and Preservation Methods. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2024, 72, 5807–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazriah, A.T.N.; Hernawati, D.; Fitriani, R. Tradition and plants: Ethnobotany in the Perlon Unggahan ritual of the Bonokeling Lineage Indigenous People. Biosf. J. Pendidik. Biol. 2025, 18, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.C.; Karamura, D.; Kakudidi, E. History and conservation of wild and cultivated plant diversity in Uganda: Forest species and banana varieties as case studies. Plant Divers. 2016, 38, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silalahi, M.; Nisyawati; Pandiangan, D. Medicinal plants used by the Batak Toba Tribe in Peadundung Village, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2019, 20, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, H.; Qureshi, R.; Qaseem, M.F.; Amjad, M.S.; Bruschi, P. The cultural importance of indices: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Noorpur Thal Punjab, Pakistan. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2017, 12, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrhmoun, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Pieroni, A. What drives herbal traditions? The influence of ecology and cultural exchanges on wild plant teas in the Balkan Mountains. Land 2024, 13, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklesilassie, Y.; Lulekal, E.; Dullo, B.W. Human–forest interaction of useful plants in the Wof Ayzurish Forest, North Showa Zone, Ethiopia: Cultural significance index, conservation, and threats. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2025, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fongfon, S.; Pusadee, T.; Prom-u-thai, C.; Rerkasem, B.; Jamjod, S. Diversity of purple rice (Oryza sativa L.) landraces in Northern Thailand. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukaew, S.; Datta, A.; Shivakoti, G.P.; Jourdain, D. Production practices influenced yield and commercial cane sugar level of contract sugarcane farmers in Thailand. Sugar Tech 2016, 18, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moungsree, S.; Neamhom, T.; Polprasert, S.; Patthanaissaranukool, W. Carbon footprint and life cycle costing of maize production in Thailand with temporal and geographical resolutions. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 891–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Gomes, N.G.M.; Duangsrisai, S.; Andrade, P.B.; Pereira, D.M.; Valentão, P. Medicinal plants utilized in Thai traditional medicine for diabetes treatment: Ethnobotanical surveys, scientific evidence and phytochemicals. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shopo, B.; Mapaya, R.J.; Maroyi, A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants traditionally used in Gokwe South District, Zimbabwe. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 149, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiong, H.N.; Fils, P.; Guekam, K.; Martin, E.; Brull, G.; Fa, J.; Funk, S.; Fongnzossie, E.; Betti, J.; Guekam, P.; et al. Traditional use of medicinal plants confirmed by the Baka in Southern and Eastern Cameroon. J. Biosci. Med. 2024, 12, 76–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Komal; Ramchiary, N.; Singh, P. Role of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and indigenous communities in achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Rakarcha, S.; Boonma, T.; Jitpromma, T.; Sonthongphithak, P.; Ragsasilp, A.; Souladeth, P. Diversity and local uses of the Convolvulaceae Family in Udon Thani Province, Thailand, with notes on its potential horticultural significance. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitima, G.; Gebre, A.; Berhanu, Y.; Wato, T. Exploring indigenous wisdom: Ethnobotanical documentation and conservation of medicinal plants in Goba District, Southwest Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 2025, 27, e02571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Alan, H.; Wang, Y. Vital roles for ethnobotany in conservation and sustainable development. Plant Divers. 2020, 42, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathoure, A. Cultural practices to protecting biodiversity through cultural heritage: Preserving nature, preserving culture. Biodivers. Int. J. 2024, 7, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y. The role of Chinese folk ritual music in biodiversity conservation: An ethnobiological perspective from the Lingnan Region. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2025, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbelebele, Z.; Mdoda, L.; Ntlanga, S.S.; Nontu, Y.; Gidi, L.S. Harmonizing traditional knowledge with environmental preservation: Sustainable strategies for the conservation of indigenous medicinal plants (IMPs) and their implications for economic well-being. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, C.; Flores, B.; Campos-Silva, J.; Peroni, N.; Staal, A.; Padgurschi, M.; Dorshow, W.; Moraes, B.; Schmidt, M.; Kuikuro, T.; et al. Contributions of human cultures to biodiversity and ecosystem conservation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisnawati, E.; Sujatna, E.T.S.; Amalia, R.; Soemantri, Y.; Pamungkas, K. The farming ritual and the rice metaphor: How people of Kasepuhan Sinarresmi worship rice. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2024, 11, 2338329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congretel, M.; Pinton, F. Local knowledge, know-how and knowledge mobilized in a globalized world: A new approach of indigenous local ecological knowledge. People Nat. 2020, 2, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nche, G.C.; Michael, B.O. Perspectives on African indigenous religion and the natural environment: Beings, interconnectedness, communities and knowledge systems. Phronimon 2024, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritonga, M.A.; Syamsuardi, S.; Nurainas, N.; Damayanto, I.P.G.P. Ethnobotany of bamboo on Weh Island, Aceh, Indonesia. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurten, E.L.; Bunyavejchewin, S.; Davies, S.J. Phenology of a Dipterocarp Forest with seasonal drought: Insights into the origin of general flowering. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanazaki, N.; Zank, S.; Fonseca-Kruel, V.; Schmidt, I. Indigenous and traditional knowledge, sustainable harvest, and the long road ahead to reach the 2020 global strategy for plant conservation objectives. Rodriguésia 2018, 69, 1587–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Family | Scientific Name | Vernacular Name | Conservation Status | Distribution Status for Thailand | Plant Habits | Resource | Used Parts | Ceremony Months | CSI | SUV | RFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Amaranthaceae | Gomphrena globosa L. | Barn Mai Roo Roy | NE | Introduced | Shrub | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 1, 2, 8, 11, 12 | 20 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 2. | Amaryllidaceae | Allium cepa L. | Hohm Daeng | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Bulb | 7, 9, 10 | 60 | 0.75 | 0.30 |

| 3. | Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum L. | Gra Tiam | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Bulb | 7, 9, 10 | 60 | 0.78 | 0.28 |

| 4. | Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | Buk Muang | DD | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 8 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

| 5. | Anacardiaceae | Spondias mombin L. | Ma Gok | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 9 | 8 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| 6. | Annonaceae | Annona squamosa L. | Noi Na | LC | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 9, 10 | 24 | 0.45 | 0.35 |

| 7. | Annonaceae | Uvaria siamensis (Scheff.) L.L.Zhou, Y.C.F.Su & R.M.K.Saunders | Lum Duan | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 4 | 4 | 0.15 | 0.30 |

| 8. | Apocynaceae | Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton | Ruk | NE | Native | Shrub | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 1, 4, 8, 11, 12 | 30 | 0.83 | 0.40 |

| 9. | Apocynaceae | Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult. | Put | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Leave and inflorescence | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12 | 72 | 0.88 | 0.33 |

| 10. | Araceae | Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | Pueak | LC | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Tuber | 2, 10, 11 | 18 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| 11. | Araceae | Lemna minor L. | Nae | LC | Native | Herb | Wild/AQ | Whole plant | 4 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| 12. | Araceae | Pistia stratiotes L. | Jok | LC | Native | Herb | Wild/AQ | Whole plant | 4 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| 13. | Arecaceae | Areca catechu L. | Mak | LC | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 10 | 48 | 0.88 | 0.23 |

| 14. | Arecaceae | Borassus flabellifer L. | Tarn | LC | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 4 | 6 | 0.55 | 0.25 |

| 15. | Arecaceae | Calamus caesius Blume | Wary | NE | Native | Shrub | Wild/TF | Fruit | 4, 6 | 8 | 0.48 | 0.38 |

| 16. | Arecaceae | Cocos nucifera L. | Ma Prow | NE | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12 | 96 | 0.88 | 0.33 |

| 17. | Asteraceae | Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M.King & H.Rob. | Sarb Suea | NE | Introduced | Herb | Wild/DA | Stem | 6 | 1 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| 18. | Asteraceae | Tagetes erecta L. | Down Rueang | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12 | 64 | 0.50 | 0.23 |

| 19. | Bignoniaceae | Millingtonia hortensis L.f. | Peeb Khow | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 4 | 4 | 0.48 | 0.25 |

| 20. | Bignoniaceae | Oroxylum indicum (L.) Kurz | Pe-ga | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 4 | 6 | 0.73 | 0.35 |

| 21. | Bromeliaceae | Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | Sapparod | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | 12 | 8 | 0.70 | 0.38 |

| 22. | Cactaceae | Selenicereus undatus (Haw.) D.R.Hunt | Gaew Mung Gorn | NE | Introduced | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 9 | 8 | 0.70 | 0.43 |

| 23. | Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Malagor | DD | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 9, 12 | 40 | 0.75 | 0.30 |

| 24. | Clusiaceae | Garcinia mangostana L. | Mung Kut | DD | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 10 | 16 | 0.63 | 0.28 |

| 25. | Combretaceae | Getonia floribunda Roxb. | Nguang Sum | NE | Native | Climber | Wild/DDF, DEF | Inflorescence | 4 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| 26. | Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | Mun Tade | DD | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Tuber | 2, 9, 10, 11 | 12 | 0.75 | 0.23 |

| 27. | Cucurbitaceae | Benincasa hispida (Thunb.) Cogn. | Fug | NE | Introduced | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 12 | 8 | 0.73 | 0.38 |

| 28. | Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis sativus L. | Taeng Gwar | NE | Native | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 10 | 24 | 0.70 | 0.43 |

| 29. | Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | Fug Tong | NE | Introduced | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 9, 10, 11 | 16 | 0.63 | 0.25 |

| 30. | Cucurbitaceae | Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai | Taeng Mo | NE | Introduced | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 24 | 0.50 | 0.28 |

| 31. | Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea hispida Dennst. | Gloy | NE | Native | Climber | Wild/DF, MDF, MEF | Tuber | 10 | 2 | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| 32. | Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea pseudotomentosa Prain & Burkill | Mun Nok | NE | Native | Climber | Cultivated | Tuber | 9, 10 | 4 | 0.28 | 0.20 |

| 33. | Dipterocarpaceae | Anthoshorea roxburghii (G.Don) P.S.Ashton & J.Heck. | Payom | NE | Native | Tree | Wild/MDF | Inflorescence | 4 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.40 |

| 34. | Dipterocarpaceae | Dipterocarpus intricatus Dyer | Sa Bang | EN | Native | Tree | Wild/DDF, MDF | Inflorescence | 4 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.30 |

| 35. | Dipterocarpaceae | Pentacme siamensis (Miq.) Kurz | Rung | NE | Native | Tree | Wild/DDF, DEF, MDF | Inflorescence | 4 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.45 |

| 36. | Fabaceae | Arachis hypogaea L. | Tour Li Song | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | 9, 10, 11 | 24 | 0.70 | 0.48 |

| 37. | Fabaceae | Butea monosperma (Lam.) Kuntze | Tong Kwarw | LC | Introduced | Tree | Wild/DF, GL | Inflorescence | 4 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| 38. | Fabaceae | Cassia fistula L. | Khoon | LC | Doubtful | Tree | Cultivated | Stem and inflorescence | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10 | 140 | 0.75 | 0.35 |

| 39. | Fabaceae | Erythrina variegata L. | Tong Lang | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 6 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.38 |

| 40. | Fabaceae | Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Tour Lueang | NE | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | 11 | 6 | 0.53 | 0.33 |

| 41. | Fabaceae | Pachyrhizus erosus (L.) Urb. | Mun Gaew | LC | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Tuber | 9, 10 | 6 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| 42. | Fabaceae | Samanea saman (Jacq.) Merr. | Chum Cha | LC | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Stem | 6 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.48 |

| 43. | Fabaceae | Sesbania javanica Miq. | Sa No | LC | Native | Herb | Wild/AQ | Inflorescence | 4 | 2 | 0.38 | 0.28 |

| 44. | Fabaceae | Vigna radiata (L.) R.Wilczek | Tour Keaw | LC | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | 11 | 3 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| 45. | Fabaceae | Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis (L.) Verdc. | Tour Fug Yown | NE | Introduced | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 8 | 0.85 | 0.25 |

| 46. | Irvingiaceae | Irvingia malayana Oliv. ex A.W.Benn. | Gra Bog | LC | Native | Tree | Wild/FE, DEF, DF, MDF, RF | Fruit | 10 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| 47. | Lamiaceae | Ocimum × africanum Lour. | Ho Ra Pha | NE | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Leave and inflorescence | 10 | 16 | 0.88 | 0.20 |

| 48. | Lythraceae | Punica granatum L. | Tun Tim | LC | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 6 | 0.53 | 0.25 |

| 49. | Marantaceae | Maranta arundinacea L. | Mun Sa Khoo | NE | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Tuber | 11 | 2 | 0.48 | 0.18 |

| 50. | Meliaceae | Lansium domesticum Corrêa | Long Gong | NE | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 9, 10 | 42 | 0.60 | 0.15 |

| 51. | Musaceae | Musa acuminata Colla | Guay Hohm | LC | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit, leave, and stem | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 | 180 | 0.88 | 0.30 |

| 52. | Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L. | Fa Rung | LC | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 9, 10, 12 | 24 | 0.70 | 0.33 |

| 53. | Nelumbonaceae | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. | Bua Luang | NE | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 11 | 42 | 0.73 | 0.15 |

| 54. | Nymphaeaceae | Nymphaea nouchali Burm.f. | Bua Fuean | LC | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 4 | 4 | 0.63 | 0.13 |

| 55. | Oleaceae | Jasminum officinale L. | Ma Li | NE | Introduced | Shrub | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 1, 5, 8, 11 | 24 | 0.75 | 0.20 |

| 56. | Pandanaceae | Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl. | Toei Hom | DD | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Leave | 1, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 | 120 | 0.75 | 0.40 |

| 57. | Pedaliaceae | Sesamum indicum L. | Nga Dum | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Seed | 3, 9, 11 | 18 | 0.60 | 0.23 |

| 58. | Phyllanthaceae | Antidesma puncticulatum Miq. | Bak Mao | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 4 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| 59. | Piperaceae | Piper betle L. | Ploo | LC | Native | Climber | Cultivated | Leave | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 10 | 120 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

| 60. | Piperaceae | Piper sarmentosum Roxb. | Cha Ploo | NE | Native | Herb | Cultivated | Leave | 10 | 6 | 0.68 | 0.40 |

| 61. | Poaceae | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh | Phai Liang | NE | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Stem | 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10 | 120 | 0.75 | 0.35 |

| 62. | Poaceae | Bambusa burmanica Gamble | Phai Wahn | NE | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Stem | 6 | 12 | 0.80 | 0.30 |

| 63. | Poaceae | Oryza sativa L. | Khao | LC | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 | 180 | 0.98 | 0.53 |

| 64. | Poaceae | Saccharum officinarum L. | Oy | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Stem | 3, 4, 7, 9, 11, 12 | 96 | 0.93 | 0.45 |

| 65. | Poaceae | Zea mays L. | Khao Pod | LC | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Fruit | 10, 11 | 12 | 0.90 | 0.38 |

| 66. | Pontederiaceae | Pontederia hastata L. | Pug Tob Cha Wa | NE | Native | Herb | Wild/AQ | Whole plant | 4 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.45 |

| 67. | Rosaceae | Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh. | Apple | NE | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 6 | 0.43 | 0.33 |

| 68. | Rubiaceae | Morinda citrifolia L. | Yor | LC | Native | Shrub | Cultivated | Leave | 2 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| 69. | Rubiaceae | Oxyceros horridus Lour. | Kud Khao | LC | Native | Climber | Cultivated | Inflorescence | 4 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.43 |

| 70. | Rubiaceae | Paederia linearis Hook.f. | Tod Moo Tod Ma | NE | Native | Vine | Wild/DF, MDF | Leave | 3 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| 71. | Rutaceae | Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | Ma Now | NE | Introduced | Shrub | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 9, 10 | 60 | 0.88 | 0.38 |

| 72. | Rutaceae | Citrus × aurantium L. | Som | NE | Introduced | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 10 | 6 | 0.65 | 0.18 |

| 73. | Rutaceae | Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr. | Som-O | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 9, 10, 12 | 18 | 0.70 | 0.10 |

| 74. | Sapindaceae | Nephelium lappaceum L. | Ngor | LC | Native | Tree | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 10 | 16 | 0.68 | 0.48 |

| 75. | Solanaceae | Capsicum frutescens L. | Prig | LC | Introduced | Shrub | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 9, 10 | 60 | 0.88 | 0.15 |

| 76. | Solanaceae | Nicotiana tabacum L. | Yaa Soob | NE | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Leave | 1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 10 | 96 | 0.73 | 0.13 |

| 77. | Solanaceae | Solanum torvum Sw. | Ma Khuea Puang | NE | Introduced | Shrub | Cultivated | Fruit | 7, 9 | 12 | 0.68 | 0.20 |

| 78. | Solanaceae | Solanum virginianum L. | Ma Khuea Proa | NE | Introduced | Shrub | Cultivated | Fruit | 7 | 6 | 0.70 | 0.23 |

| 79. | Vitaceae | Vitis vinifera L. | A-ngun | LC | Introduced | Climber | Cultivated | Fruit | 9, 10 | 12 | 0.63 | 0.38 |

| 80. | Zingiberaceae | Curcuma longa L. | Khamin Chan | DD | Introduced | Herb | Cultivated | Rhizome | 7 | 6 | 0.73 | 0.25 |

| Genera | GUV | Genera | GUV | Genera | GUV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oryza | 0.98 | Ananas | 0.70 | Annona | 0.45 |

| Saccharum | 0.93 | Arachis | 0.70 | Malus | 0.43 |

| Zea | 0.90 | Cucumis | 0.70 | Colocasia | 0.38 |

| Areca | 0.88 | Psidium | 0.70 | Sesbania | 0.38 |

| Capsicum | 0.88 | Selenicereus | 0.70 | Spondias | 0.35 |

| Cocos | 0.88 | Vigna | 0.70 | Butea | 0.30 |

| Musa | 0.88 | Solanum | 0.69 | Morinda | 0.30 |

| Ocimum | 0.88 | Nephelium | 0.68 | Dioscorea | 0.28 |

| Tabernaemontana | 0.88 | Cucurbita | 0.63 | Gomphrena | 0.25 |

| Calotropis | 0.83 | Garcinia | 0.63 | Erythrina | 0.23 |

| Bambusa | 0.80 | Nymphaea | 0.63 | Paederia | 0.23 |

| Allium | 0.76 | Vitis | 0.63 | Oxyceros | 0.15 |

| Carica | 0.75 | Lansium | 0.60 | Uvaria | 0.15 |

| Cassia | 0.75 | Sesamum | 0.60 | Anthoshorea | 0.13 |

| Ipomoea | 0.75 | Borassus | 0.55 | Dipterocarpus | 0.13 |

| Jasminum | 0.75 | Glycine | 0.53 | Lemna | 0.13 |

| Pandanus | 0.75 | Punica | 0.53 | Pentacme | 0.13 |

| Thyrsocalamus | 0.75 | Citrullus | 0.50 | Pistia | 0.13 |

| Citrus | 0.74 | Mangifera | 0.50 | Samanea | 0.13 |

| Benincasa | 0.73 | Pachyrhizus | 0.50 | Chromolaena | 0.10 |

| Curcuma | 0.73 | Tagetes | 0.50 | Irvingia | 0.08 |

| Nelumbo | 0.73 | Antidesma | 0.48 | Getonia | 0.05 |

| Nicotiana | 0.73 | Calamus | 0.48 | Pontederia | 0.05 |

| Oroxylum | 0.73 | Maranta | 0.48 | ||

| Piper | 0.71 | Millingtonia | 0.48 |

| Scientific Name | SUV | RFC |

|---|---|---|

| Oryza sativa L. | 0.98 | 0.53 |

| Saccharum officinarum L. | 0.93 | 0.45 |

| Zea mays L. | 0.90 | 0.38 |

| Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | 0.88 | 0.38 |

| Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult. | 0.88 | 0.33 |

| Cocos nucifera L. | 0.88 | 0.33 |

| Musa acuminata Colla | 0.88 | 0.30 |

| Areca catechu L. | 0.88 | 0.23 |

| Ocimum × africanum Lour. | 0.88 | 0.20 |

| Capsicum frutescens L. | 0.88 | 0.15 |

| Ceremonial | Plant Species |

|---|---|

| Bun Khao Kam (Month 1) | Areca catechu L., Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton, Cassia fistula L., Gomphrena globosa L., Jasminum officinale L., Musa acuminata Colla, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Nicotiana tabacum L., Oryza sativa L., Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl., Piper betle L., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Tagetes erecta L. |

| Bun Khun Lan (Month 2) | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh, Areca catechu L., Cassia fistula L., Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott, Gomphrena globosa L., Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam., Morinda citrifolia L., Musa acuminata Colla, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Nicotiana tabacum L., Oryza sativa L., Piper betle L., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Tagetes erecta L. |

| Bun Khao Jee (Month 3) | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh, Cocos nucifera L., Oryza sativa L., Paederia linearis Hook.f., Saccharum officinarum L., Sesamum indicum L. |

| Bun Pha Wet (Month 4) | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh, Anthoshorea roxburghii (G.Don) P.S.Ashton & J.Heck., Areca catechu L., Borassus flabellifer L., Butea monosperma (Lam.) Kuntze, Calamus caesius Blume, Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton, Cassia fistula L., Cocos nucifera L., Dipterocarpus intricatus Dyer, Getonia floribunda Roxb., Lemna minor L., Millingtonia hortensis L.f., Musa acuminata Colla, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Nicotiana tabacum L., Nymphaea nouchali Burm.f., Oroxylum indicum (L.) Kurz, Oryza sativa L., Oxyceros horridus Lour., Pentacme siamensis (Miq.) Kurz, Piper betle L., Pistia stratiotes L., Pontederia hastata L., Saccharum officinarum L., Sesbania javanica Miq., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Uvaria siamensis (Scheff.) L.L.Zhou, Y.C.F.Su & R.M.K.Saunders |

| Bun Songkran (Month 5) | Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Cassia fistula L., Jasminum officinale L., Musa acuminata Colla, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl., Tagetes erecta L. |

| Bun Bang Fai (Month 6) | Bambusa burmanica Gamble, Calamus caesius Blume, Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M.King & H.Rob., Erythrina variegata L., Oryza sativa L., Samanea saman (Jacq.) Merr. |

| Bun Samha (Month 7) | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh, Allium cepa L., Allium sativum L., Annona squamosa L., Areca catechu L., Capsicum frutescens L., Carica papaya L., Cassia fistula L., Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle, Cucumis sativus L., Curcuma longa L., Garcinia mangostana L., Lansium domesticum Corrêa, Musa acuminata Colla, Nephelium lappaceum L., Nicotiana tabacum L., Oryza sativa L., Piper betle L., Saccharum officinarum L., Solanum torvum Sw., Solanum virginianum L., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult. |

| Bun Khao Phansa (Month 8) | Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton, Gomphrena globosa L., Jasminum officinale L., Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Tagetes erecta L. |

| Bun Khao Pradap Din (Month 9) | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh, Allium cepa L., Allium sativum L., Annona squamosa L., Arachis hypogaea L., Areca catechu L., Capsicum frutescens L., Carica papaya L., Cassia fistula L., Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle, Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr., Cocos nucifera L., Cucurbita maxima Duchesne, Dioscorea pseudotomentosa Prain & Burkill, Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam., Lansium domesticum Corrêa, Musa acuminata Colla, Nicotiana tabacum L., Oryza sativa L., Pachyrhizus erosus (L.) Urb., Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl., Piper betle L., Psidium guajava L., Saccharum officinarum L., Selenicereus undatus (Haw.) D.R.Hunt, Sesamum indicum L., Solanum torvum Sw., Spondias mombin L., Tagetes erecta L., Vitis vinifera L. |

| Bun Khao Sak (Month 10) | × Thyrsocalamus liang Sungkaew & W.L.Goh, Allium cepa L., Allium sativum L., Annona squamosa L., Antidesma puncticulatum Miq., Arachis hypogaea L., Areca catechu L., Capsicum frutescens L., Carica papaya L., Cassia fistula L., Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai, Citrus × aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle, Citrus × aurantium L., Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr., Cocos nucifera L., Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott, Cucumis sativus L., Cucurbita maxima Duchesne, Dioscorea hispida Dennst., Dioscorea pseudotomentosa Prain & Burkill, Garcinia mangostana L., Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam., Irvingia malayana Oliv. ex A.W.Benn., Lansium domesticum, Malus domestica (Suckow) Borkh., Mangifera indica L., Musa acuminata Colla, Nephelium lappaceum L., Nicotiana tabacum L., Ocimum × africanum Lour., Oryza sativa L., Pachyrhizus erosus (L.) Urb., Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl., Piper betle L., Piper sarmentosum Roxb., Psidium guajava L., Punica granatum L., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Tagetes erecta L., Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis (L.) Verdc., Vitis vinifera L., Zea mays L. |

| Bun Ok Phansa (Month 11) | Arachis hypogaea L., Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton, Cocos nucifera L., Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott, Cucurbita maxima Duchesne, Glycine max (L.) Merr., Gomphrena globosa L., Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam., Jasminum officinale L., Maranta arundinacea L., Musa acuminata Colla, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Oryza sativa L., Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. ex Lindl., Saccharum officinarum L., Sesamum indicum L., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Tagetes erecta L., Vigna radiata (L.) R.Wilczek, Zea mays L. |

| Bun Kathin (Month 12) | Ananas comosus (L.) Merr., Benincasa hispida (Thunb.) Cogn., Calotropis gigantea (L.) W.T.Aiton, Carica papaya L., Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merr., Cocos nucifera L., Gomphrena globosa L., Musa acuminata Colla, Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Psidium guajava L., Saccharum officinarum L., Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R.Br. ex Roem. & Schult., Tagetes erecta L. |

| Month (Lunar Calendar) | Name of Ceremony | Aim of Ceremony |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bun Khao Kam | To foster community gatherings, rituals, and offerings, enhancing cultural identity and communal ties. |

| 2 | Bun Khun Lan | To honor Mother Earth and Mother Rice, engage in merit-making for good fortune, and raise the rice spirit among farmers. |

| 3 | Bun Khao Jee | To offer gratitude and respect during the post-harvest season by preparing and offering Khao Jee (grilled sticky rice balls) to the Buddha. |

| 4 | Bun Pha Wet | To commemorate the story of Phra Maha Vessantara Jataka, illustrating the Buddha’s ten perfections, through elaborate rituals and offerings. |

| 5 | Bun Songkran | To symbolize a request for forgiveness and blessings by pouring perfumed water over Buddha images, monks, and elders, and to express deep respect for cultural and spiritual practices. |

| 6 | Bun Bang Fai | To worship the city pillar’s guardian spirit, make merit, and request timely rain from Phaya Taen (the rain god) for the upcoming agricultural season. |

| 7 | Bun Samha | To drive out evil spirits, ghosts, demons, and other malevolent entities from the village, fostering community solidarity and cultural identity. |

| 8 | Bun Khao Phansa | To mark the beginning of the three-month Buddhist Lent, make merit by offering alms and essential items to monks, cultivate spiritual merit, and reinforce community bonds. |

| 9 | Bun Khao Pradap Din | To make merit for the deceased and extend compassion to spirits, ghosts, and stray animals during a sacred time when the gates of hell are believed to open. |

| 10 | Bun Khao Sak | To make merit for deceased relatives by preparing and offering food trays (including sticky rice, dried foods, and small rice bags) at the temple. |

| 11 | Bun Ok Phansa | To mark the conclusion of Buddhist Lent, engage in merit-making (giving alms, offering food, listening to sermons), and show devotion to the Triple Gem and ancestors. |

| 12 | Bun Kathin | To foster unity within the community by offering new robes to monks, symbolizing renewal and support, and emphasizing communal harmony and collective merit-making. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Boonma, T.; Ragsasilp, A.; Junsongduang, A.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Jitpromma, T. Plant Species Diversity and the Interconnection of Ritual Beliefs and Local Horticulture in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11060677

Saensouk P, Saensouk S, Boonma T, Ragsasilp A, Junsongduang A, Chanthavongsa K, Jitpromma T. Plant Species Diversity and the Interconnection of Ritual Beliefs and Local Horticulture in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(6):677. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11060677

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaensouk, Piyaporn, Surapon Saensouk, Thawatphong Boonma, Areerat Ragsasilp, Auemporn Junsongduang, Khamfa Chanthavongsa, and Tammanoon Jitpromma. 2025. "Plant Species Diversity and the Interconnection of Ritual Beliefs and Local Horticulture in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand" Horticulturae 11, no. 6: 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11060677

APA StyleSaensouk, P., Saensouk, S., Boonma, T., Ragsasilp, A., Junsongduang, A., Chanthavongsa, K., & Jitpromma, T. (2025). Plant Species Diversity and the Interconnection of Ritual Beliefs and Local Horticulture in Heet Sip Song Ceremonies, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae, 11(6), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11060677