Abstract

This study investigates the plant diversity, ethnobotanical knowledge, and traditional uses of plants by the Lao Isan ethnic group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. A total of 109 plant species, representing 48 families, were identified, with the Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae families being the most prevalent. This study highlights the ecological and cultural significance of these plants, many of which serve multiple purposes, including food, medicine, and other purposes. A use value analysis revealed that plants such as Schleichera oleosa (Lour.) Oken, Trigonostemon reidioides (Kurz) Craib, and Vietnamosasa pusilla (A.Chev. & A.Camus) T.Q.Nguyen have high functional importance in local cultural and medical practices. The Relative Frequency of Citation indicated that these species are integral to the community’s plant knowledge, with Trigonostemon reidioides and Vietnamosasa pusilla being especially prominent. Additionally, 62 species were identified for medicinal use, emphasizing the community’s reliance on plant-based remedies. This study also discusses the Informant Consensus Factor and Fidelity Level, which reveal strong agreement on the effectiveness of certain plants, particularly for treating digestive, respiratory, and wound healing conditions. This research contributes to the documentation of ethnobotanical knowledge, emphasizing the importance of traditional plant use for cultural continuity and sustainable resource management.

1. Introduction

Throughout human history, plants have played an essential role in providing food, medicine, shelter, and clothing [1,2]. This knowledge of plant use has been passed down through generations and is deeply embedded in the cultures of various ethnic groups [3]. Over time, plant-based knowledge has evolved to meet the changing needs of each generation, particularly in rural and indigenous communities where modern healthcare may be limited [4]. The study of ethnobotany, which focuses on the relationship between people and plants, has gained increasing importance in documenting how different cultures use plants, especially medicinally, and understanding the ecological and cultural implications of this knowledge [5,6].

In many traditional societies, plant knowledge is transmitted orally from elders to younger generations [7]. While effective in maintaining cultural continuity, this method of knowledge transfer makes traditional plant knowledge vulnerable to loss [8]. As communities transition from rural to urban lifestyles and as external influences like globalization and technology impact local practices, the transmission of this vital knowledge is at risk [9]. Younger generations may no longer prioritize learning about plants and their uses, leading to the erosion of a cultural heritage developed over centuries [10].

Thailand is home to a rich diversity of ethnic communities, many of which possess extensive knowledge of plant use for food, medicine, and other practical purposes [11,12,13,14]. Similar concerns have been reported in other parts of Thailand, e.g., studies on Thai Karen and Lawa communities revealed that while traditional knowledge of wild food plants remains rich, younger generations exhibit declining interest in plant-based practices [11]. Likewise, a comparative study among Thai ethnic groups found significant variation in the use and retention of medicinal plant knowledge, with modernization influencing the younger cohorts’ engagement [12]. Among the Tai Yai people in Northern Thailand, traditional medicinal practices are still practiced but face gradual erosion as younger individuals favor modern healthcare approaches [13]. These findings highlight a consistent regional trend: the transmission of ethnobotanical knowledge is increasingly at risk as cultural and lifestyle shifts continue. One such group is the Lao Isan ethnic group, who reside predominantly in the northeastern region of the country [15]. The Isan region, with its rural landscapes and agricultural practices, has profoundly shaped the relationship between local communities and their environment [16]. The Lao Isan people, who constitute the majority population in Na Chueak District, were chosen as the focus of this study due to their strong cultural continuity and extensive traditional knowledge of plant use. Their ethnobotanical practices, deeply embedded in agricultural and domestic activities, have been carefully transmitted across generations. However, the increasing influence of modernization raises concerns about the gradual loss of this invaluable heritage. Thus, documenting and preserving the ethnobotanical knowledge of the Lao Isan community is crucial for maintaining their local wisdom for future generations.

Although numerous ethnobotanical surveys have been carried out in Thailand, large parts of the country—especially the rural areas of the northeast—remain insufficiently explored in terms of traditional plant use [17,18,19,20]. Maha Sarakham Province, located in northeastern Thailand, supports a significant Lao Isan population that continues to depend on natural resources for food, medicine, and cultural practices [18,19]. Despite limited forest cover, the province contains diverse ecosystems that sustain essential plant species [20]. In Na Chueak District, the Lao Isan people possess a profound understanding of their local flora, applying it in medicinal, nutritional, and cultural contexts. However, modernization—particularly among younger generations—has disrupted the transmission of this knowledge [21]. As urbanization spreads and modern healthcare systems take root, traditional plant knowledge and the sustainable practices associated with it face the risk of being forgotten [22,23,24].

The Lao Isan people of Na Chueak District have developed a rich ethnobotanical tradition, with plants being central to daily life. Despite the decline in plant use, these species remain vital to the community’s survival and well-being. The medicinal plants used by the Lao Isan people are a key aspect of their cultural heritage, but their continued use is threatened by changes in lifestyle and increasing reliance on modern medicine [25].

This study aims to address this gap by documenting the plant species used by the Lao Isan ethnic group in the Na Chueak District. By identifying these species and their traditional uses, this research aims to create a comprehensive record of the ethnobotanical knowledge of the community. This documentation will help preserve the valuable traditional knowledge, which is essential for cultural continuity and sustainable resource management. Furthermore, by promoting the use of local plant resources in a sustainable manner, this research will contribute to the long-term conservation of both the community’s cultural heritage and the biodiversity of the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

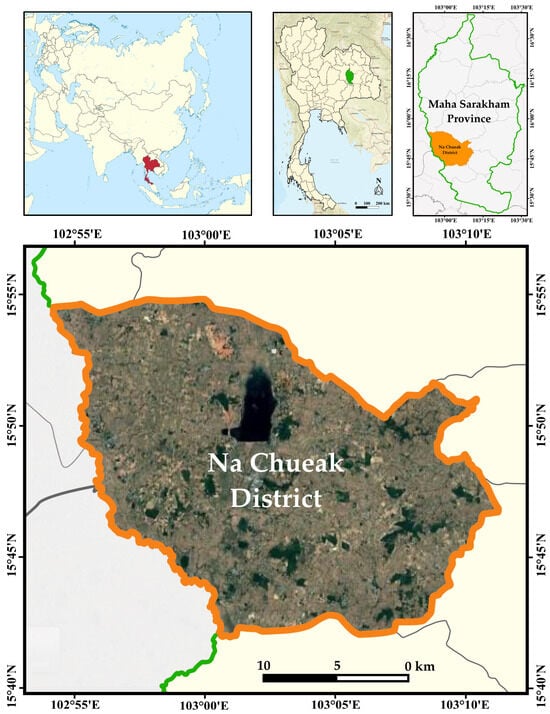

The research area is located in the Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province. This public land is accessible to local communities for a variety of uses (Figure 1). The surrounding communities maintain lifestyles that are closely connected to nature. The landscape is predominantly flat, covered with deciduous forest, and features plateaus and uplands primarily composed of sandy soil. The level terrain makes the area suitable for agriculture, while the higher plateaus are particularly well-suited for growing crops like cassava and sugarcane.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area: Left shows Maha Sarakham Province in green within Thailand. The center highlights Na Chueak District in orange within the province. The right shows the detailed boundary of Na Chueak District on a topographic map. Graphics designed using the Pixelmator Pro Program (Version 3.6.15 (Archipelago), 2025, Pixelmator Team, Vilnius, Lithuania, designed by T.B.

2.2. Data Collection

Plant surveys were carried out in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, from January to December 2022. The study involved interviews with experts, traditional healers, elders, and villagers from surrounding communities near the forest area. A total of 400 individuals were interviewed, with 40 individuals (20 males and 20 females) selected from each of the 10 subdistricts in Na Chueak District. This sampling strategy aimed to ensure comprehensive coverage of local knowledge while minimizing bias. Interviews were conducted using open-ended questions to gather information on local plant names, their uses, and the plant parts utilized in three main categories: food, medicine, and other purposes. To enhance data reliability and minimize potential information bias, the collected information was cross-validated with local experts, traditional healers, and elders. The plants identified were documented by their local names, photographed, and sampled for herbarium specimens, which were then deposited at the Vascular Plant Herbarium, Mahasarakham University (VMSU). Species identification was confirmed by comparing the specimens with original descriptions and reference materials from the Plant of the World Online (POWO) [26]. Additionally, a comprehensive review of the relevant taxonomic literature and research databases (such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) was conducted, along with comparisons to digital images from Kew Herbarium and the Kew Science website.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Use Value (UV)

The UV represents the importance of a plant species in a specific region, as described by Phillips et al. (1994) [27], and is determined using the following formula:

where UVs signifies the total use value of the species, UVis represents its specific use value, and ns indicates the number of informants interviewed for that species.

2.3.2. The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) is a method used to evaluate the significance of plant species mentioned by informants, as outlined in earlier research. The RFC is determined using the following formula [28]:

where FC stands for the frequency with which a species is cited, and N is the total number of informants in the study. This index does not consider the specific uses of the plants and ranges between 0 and 1. A value near 0 means very few informants have mentioned the species, while a value of 1 indicates that every informant has referred to it.

RFC = FC/N

2.3.3. The Informant Consensus Factor (Fic)

The Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) is used to measure the variation in the use of medicinal plants. It is calculated using the following formula [29]:

In this equation, nur represents the total number of use reports within a specific category, while nt denotes the number of plant taxa used in that category.

2.3.4. Fidelity Level (FL)

The Fidelity Level (FL) measures the percentage of informants who identified a particular plant species as a treatment for a specific illness in the study area. It is calculated using the following formula [30]:

In this equation, Ip represents the number of informants who associated the plant with a particular disease, while Iu refers to the total number of informants who acknowledged the plant’s medicinal use for any health condition.

3. Results

3.1. Plant Diversity in the Community of Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province

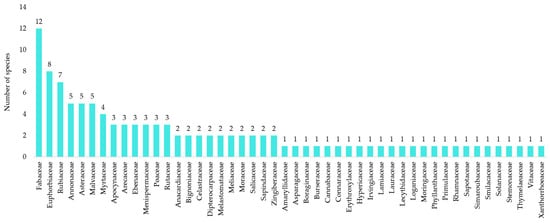

In total, we registered 109 plant species from 48 families of the Lao Isan Ethnic group from Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province (Table 1, Figure 2). The notable families frequently represented in the area included the Fabaceae family, with 12 species; the Euphorbiaceae family, with eight species; and the Rubiaceae family, with seven species. Additionally, the Annonaceae, Asteraceae, and Malvaceae families each contributed five species, while Myrtaceae had four species. The Apocynaceae, Arecaceae, Ebenaceae, Menispermaceae, Poaceae, and Rutaceae families were represented by three species each. Furthermore, Anacardiaceae, Bignoniaceae, Celastraceae, Dipterocarpaceae, Melastomataceae, Meliaceae, Moraceae, Salicaceae, Sapindaceae, and Zingiberaceae each had two species. The remaining families were represented by only one species each. Among these, 91 species are native to Thailand, with some native species illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 1.

The diversity of plant species found in Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, including their vernacular names, conservation status, distribution, utilization, used parts, UV, RFC, and specimen vouchers.

Figure 2.

Diversity of plants in the community of Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

Figure 3.

Some native plant species used by the Lao Isan ethnic group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province: (a) Buchanania lanzan Spreng.; (b) Microcos tomentosa Sm.; (c) Millingtonia hortensis L.f.; (d) Paederia linearis Hook.f.; (e) Peltophorum dasyrhachis (Miq.) Kurz; (f) Streptocaulon juventas (Lour.) Merr.; (g) Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels; (h) Uvaria rufa (Dunal) Blume; (i) Ziziphus oenopolia (L.) Mill. Photographs by T.J.

3.2. The UV of Plants Used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province

The high UV (≥2.5) category consists of plants that play significant roles in traditional and ecological practices and are frequently used for various medicinal, cultural, or industrial purposes. Among the highest-valued species are Schleichera oleosa, Trigonostemon reidioides, and Vietnamosasa pusilla (UV = 3.00), all of which are highly regarded for their medicinal and ecological importance. Other plants with high UVs (≥2.5) include Phyllanthus emblica (UV = 2.95), Peltophorum dasyrhachis, and Litsea glutinosa (UV = 2.90), reflecting their broad utilization across multiple sectors.

The medium-use value (2.0–2.49) category includes plants that have a moderate but important role in traditional medicine and other cultural practices. These species are widely used in various regions but are not as universally essential as those in the high-use category. Notable species in this category include Careya arborea (UV = 2.15), Annona squamosa (UV = 2.00), Uvaria ferruginea (UV = 2.00), and Amphineurion marginatum (UV = 2.00), all of which indicate their moderate yet significant presence in local applications. Other species, such as Phoenix acaulis (UV = 2.00), Gymnanthemum amygdalinum (UV = 2.00), and Cassia fistula (UV = 2.00), are valued for their roles in traditional practices, though they may not be as frequently used as the high UV species.

The low-use value (<2.0) category comprises species with relatively limited use in ecological or medicinal contexts. While these plants may hold local significance and be used for specific purposes, their overall contribution is less pronounced compared to those with higher UVs. Species in this category include Jatropha gossypiifolia (UV = 0.95), Elephantopus scaber (UV = 0.90), and Paederia linearis (UV = 0.80). Although these plants may have specialized uses in certain regions, their overall importance is limited when compared to species with higher use values.

The UV analysis underscores the varying levels of importance of plant species used for ecological, medicinal, and cultural purposes. The high UV category highlights species that are integral to local practices and industries, while the medium UV category contains plants with moderate utility. The low UV category indicates species with more specialized or region-specific uses, emphasizing the diverse roles plants play in different ecosystems and human activities [27].

3.3. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of Plants of Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province

Based on the collected data (Table 2), the results highlight the significant roles of certain plant species within local traditional and ecological practices. The RFC values reveal the most frequently mentioned species, while the UV reflects the extent of their applications across medicinal, cultural, and industrial uses.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Top 10 UV with the RFC of Plants of Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

Among the species recorded, Trigonostemon reidioides, Vietnamosasa pusilla, and Schleichera oleosa each had the highest UV (3.00) and demonstrated high RFC values (0.70–0.73), suggesting that these species are not only highly valued and frequently utilized in local practices but also culturally important. The consistently high UV and RFC rankings imply strong, shared traditional knowledge and widespread reliance on these species across the community. Their integral role in both medicinal and ecological applications further confirms their significance in sustaining community health and resource management.

Other species, such as Phyllanthus emblica (UV = 2.95, RFC = 0.68) and Litsea glutinosa (UV = 2.90, RFC = 0.70), also exhibited high UVs, coupled with substantial RFC values, indicating their widespread use in various sectors. These species are commonly cited for their multiple benefits, particularly in traditional medicine and local industry.

Species like Senna siamea (UV = 2.75, RFC = 0.65) and Urceola polymorpha (UV = 2.55, RFC = 0.63) were also frequently mentioned, albeit with slightly lower UVs, suggesting that while they are important in the community’s knowledge systems, their specific applications may be more specialized compared to the highest-ranking species. Similarly, Memecylon scutellatum (UV = 2.55, RFC = 0.60) and Ehretia aspera (UV = 2.50, RFC = 0.58) exhibit moderate presence in local practices with notable but slightly less versatile uses.

The results also revealed species with lower UV and RFC values, such as Jatropha gossypiifolia (UV = 0.95, RFC = 0.33) and Elephantopus scaber (UV = 0.90, RFC = 0.33), indicating that although these species are recognized within certain regions or communities, their uses are more limited in scope.

The findings underscore the diverse roles that plant species play in supporting both ecological balance and human well-being. The relationship between RFC and UV demonstrates that species with high RFC values are frequently mentioned in local knowledge systems, while those with higher UVs are recognized for their broader range of applications, reflecting their cultural, medicinal, and ecological significance.

3.4. Plants Utilization of Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province

3.4.1. Plants Used as Food

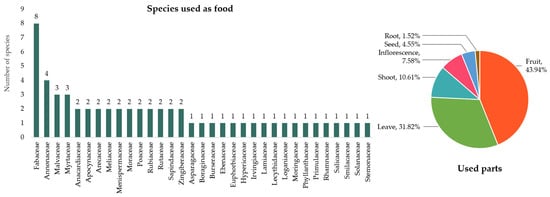

This study documented the diversity of plant species used as food by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province (Table 1, Figure 4). A total of 58 plant species were identified, distributed across 33 families. The diversity of plant species highlights the rich ethnobotanical knowledge of the community, showcasing a wide range of plants utilized for food, both for sustenance and for cultural practices.

Figure 4.

The diversity of plant species and the parts of plants used as food by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

The plant species identified belong to a variety of families, with the Fabaceae family contributing the largest number of species (eight species), followed by Annonaceae with four species. Other families with notable representation include Malvaceae, Myrtaceae, and Anacardiaceae, each contributing three species. A total of 14 families contributed only one species each, indicating a broad but specialized use of various plants across different ecological zones within the forest.

The primary parts utilized are the fruits, which constitute 43.94%, followed by the leaves at 31.82%. Shoots are used at a rate of 10.61%, while inflorescences contribute 7.58%. Seeds and roots are used less frequently, comprising 4.55% and 1.52%, respectively (Table 3, Figure 4).

Table 3.

The diversity of plant species and the methods of using them as food used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

3.4.2. Plants Used as Medicine

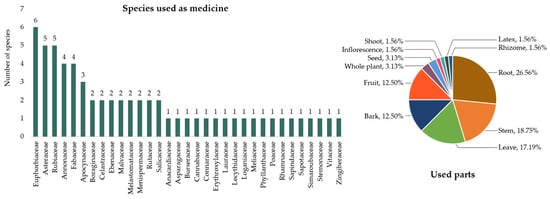

This study explored the diversity of plant species used for medicinal purposes (Table 1, Figure 5). A total of 62 species were identified, distributed across 33 distinct plant families. This diversity highlights the important role of plants in traditional medicine, demonstrating the wide range of therapeutic applications recognized by local communities.

Figure 5.

The diversity of plant species and the parts of plants used as medicine by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

The identified species belong to a broad array of families, with Euphorbiaceae contributing the largest number of species (six), followed by Asteraceae and Rubiaceae, each with five species. Other families with notable representation include Annonaceae and Fabaceae, each contributing four species, and Apocynaceae, with three species. Additionally, the families Boraginaceae, Celastraceae, Ebenaceae, Malvaceae, Melastomataceae, Menispermaceae, Rutaceae, and Salicaceae each contributed two species. In total, 19 families contributed only a single species, indicating a specialized use of particular plants for medicinal purposes. This pattern underscores the rich variety of medicinal plants utilized across different ecological regions and cultural practices. The primary parts utilized are the roots, which account for 26.56%, followed by the stem at 18.75%. Leaves are used at a rate of 17.19%, while the fruit and bark each contribute 12.50%. Seeds and whole plants each make up 3.13%. Latex, rhizomes, shoots, and inflorescences each account for 1.56% (Table 4, Figure 5).

Table 4.

The diversity of plant species, preparation, and ailments used as medicine by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

3.4.3. Plants Used for Other Purposes

This study documented the diversity of plant species used for various purposes by the local community in the region. A total of 44 species across 28 plant families were identified (Table 1, Figure 6). The diversity of plant species highlights the wide range of plants utilized for practical and cultural applications, reflecting the community’s profound knowledge of their local flora.

Figure 6.

The diversity of plant species and the parts of plants used for other purposes by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

The plant species identified belong to a variety of families, with the Fabaceae family contributing the largest number of species (eight species), followed by Anacardiaceae, Bignoniaceae, Dipterocarpaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Malvaceae, Meliaceae, Myrtaceae, Poaceae, and Rubiaceae, each contributing two species. A total of 18 families contributed only one species each, reflecting the specialized uses of certain plants for specific purposes, such as fabric drying, firewood, or agricultural equipment. These findings underscore the broad but focused application of diverse plant resources across different ecological zones within the study area. The most commonly used part is the stem, making up 84.44%, followed by the whole plant at 6.68%. The bark is utilized at 4.44%, while both the fruit and leaves are used at an equal rate of 2.22% each (Table 5, Figure 6).

Table 5.

The diversity of plant species and the methods of using them for other purposes used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

3.5. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) of Plants Used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province

This study assessed the Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) for various medical categories of the Lao Isan Ethnic group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, providing insight into the local community’s use of plant species for medicinal purposes (Table 6). The Fic values indicate the level of consensus among informants regarding the use of specific plant species for different health conditions. Higher Fic values suggest greater agreement among informants about the efficacy of particular plants in treating specific disorders.

Table 6.

Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) of medical categories Used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

A strong consensus was observed for conditions treated by a single plant species, such as Endocrine system disorders (Diabetes) and Genitourinary system issues (Diuretic), each with a Fic value of 1.000, indicating full agreement among informants on the use of one plant for these ailments. Similarly, other categories with high consensus included Other (Shampoo), which had a Fic of 0.974, and Skin disorders (skin nourishment, rashes), with a Fic of 0.973. These categories reflect widespread agreement on the use of specific plant species within the community.

The Muscular-skeletal system (Muscle pain, Sprain) and Pregnancy/Birth/ Puerperium (Lactation stimulant, Recovery after birth) categories, which involved a larger number of use reports (98 and 172, respectively), had slightly lower Fic values (0.948 and 0.947), indicating strong, but slightly less unanimous consensus. Nutritional disorders (Topic, Nutrients supplement) also showed a similar level of agreement, with a Fic of 0.947.

In contrast, the Digestive system category, including ailments like hemorrhoids, stomachaches, gastritis, constipation, and carminative uses, had the most extensive range of species (17 taxa) but still retained a notable Fic value of 0.937, reflecting a broad recognition of plants for treating these conditions.

Other categories, such as Poisonings (Sting, Parasite, Insect Repellent) and Infections (Fever, Diarrhea, Abscess, Gonorrhea, Conjunctivitis), had moderate Fic values of 0.936 and 0.929, respectively, indicating agreement on the medicinal uses of certain plant species, although with slightly more diversity in the plants used for these conditions.

This diverse pattern of consensus underscores the depth of local knowledge regarding plant-based remedies and the community’s extensive use of specific plants for treating a wide array of health issues across various systems of the body.

3.6. Fidelity Level (FL) of Plants Used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province

The Fidelity Level (FL) of medicinal plants of the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, shown in Table 7, represents the percentage of informants who reported using a particular plant for each corresponding medical category. Plants with a higher FL are those that are commonly used and highly trusted within the community for treating specific disorders.

Table 7.

Fidelity Level (FL) of medical plants Used by the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province.

For defined symptoms, both Ehretia aspera and Urceola polymorpha demonstrated a high fidelity level of 100%, suggesting these species are consistently used for treating these symptoms. Similarly, in the digestive system category, several species, including Careya arborea, Cissus repanda, Discospermum parvifolium, Ellipanthus tomentosus, and others, also exhibited a 100% fidelity level, indicating widespread use across the community for digestive ailments. Other plants, such as Kaempferia marginata (60% FL) and Tinospora crispa (30% FL), are used less frequently but still show some level of recognition within the community for digestive health.

In the endocrine system, Tinospora crispa is used by 50% of informants for treating relevant disorders, suggesting it is a commonly used plant, though not as universally relied upon as other species. For genitourinary system disorders, Grewia abutilifolia showed a high fidelity level of 100%, indicating it is a primary treatment for such issues. In the infection category, several plants, including Canarium subulatum, Helicteres angustifolia, and Lannea coromandelica, also had a 100% FL, suggesting they are considered essential for treating infections. However, plants such as Tinospora crispa (20% FL) are used less frequently for infections.

In the injuries category, both Streptocaulon juventas and Chromolaena odorata were highly regarded, with S. juventas reaching 100% FL and C. odorata showing an 80% FL, reflecting its high use for treating injuries.

Muscular-skeletal system issues were dominated by Catunaregam tomentosa, Croton persimilis, Ridsdalea wittii, and Xylia xylocarpa, all with 100% FL. Other plants like Trigonostemon reidioides (53% FL) and Kaempferia marginata (40% FL) are used, but less universally, for muscle and joint pain.

The nutritional disorders category saw a wide range of plants used, with Aporosa villosa, Asparagus racemosus, and others having a 100% FL, indicating broad acceptance within the community for treating these disorders. Other plants, such as Polyalthia debilis (50% FL), are less common but still play a role in addressing nutritional issues.

For the other category, Annona squamosa and Litsea glutinosa were highly favored, both with a 100% FL, showcasing their essential role in non-specific therapeutic uses. In the poisonings category, Canthium berberidifolium, Cassia fistula, and Strychnos nux-blanda all had a 100% FL, indicating that they are regarded as reliable remedies for poisonings. However, Diospyros martabanica (40% FL) shows a more limited use for this category.

Pregnancy/Birth/Puerperium treatments featured a wide range of plants with Amphineurion marginatum, Blumea balsamifera, and others, all showing a 100% FL, suggesting these plants are integral to postpartum recovery and lactation support. Diospyros ehretioides (59% FL) was also used, albeit to a lesser extent.

In the respiratory system, both Millingtonia hortensis and Phyllanthus emblica had a 100% FL, demonstrating their pivotal role in treating respiratory issues. Diospyros ehretioides (41% FL) was used less frequently for this purpose. Lastly, for skin disorders, both Bidens biternate and Stemona collinsae had a perfect 100% FL, making them key plants for addressing various skin conditions.

3.7. Conservation Status

Based on assessments from the IUCN Red List website [31], among the 109 species examined, 2 species are listed as Data Deficient (DD), 50 as Not Evaluated (NE), 2 as Near Threatened (NT), 52 as Least Concern (LC), and only a few are recognized under threatened categories, including 1 species each as Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), and Critically Endangered (CR). In contrast, the authors’ proposed conservation assessments, based on field observations, updated distribution data, and consideration of plant utilization reports, suggest a notable shift in threat levels: 77 species are categorized as Least Concern (LC), 28 as Vulnerable (VU), 3 as Endangered (EN)—including Buchanania lanzan, Pterocarpus macrocarpus, and Irvingia malayana,—and 1 species, Dalbergia oliveri, is proposed to be Critically Endangered. No species are placed under DD, NE, or NT in the authors’ assessment. During the field survey, it was observed that local communities tend to place greater value on and actively conserve plant species that are directly beneficial to them, as they recognize their long-term utility. As part of the research process, we engaged in knowledge exchange with local residents, particularly emphasizing the importance of sustainable harvesting practices. Fostering local awareness of the ecological and cultural value of native plant resources and encouraging community-led stewardship is often more effective and sustainable than imposing external conservation controls.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the plant diversity, ethnobotanical knowledge, and traditional uses of plants by the Lao Isan ethnic group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province. Our findings revealed a rich diversity of 109 plant species belonging to 48 families, with a notable prevalence of species from the Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae families. These findings not only contribute to understanding the ecological richness of the region but also provide a detailed account of the cultural significance and utility of these plants in local practices.

The results demonstrate a substantial diversity of plant families, with particular emphasis on the Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae families. These families are dominant in the local flora, and their high representation in the ethnobotanical survey points to their wide-ranging uses in food, medicine, and construction, consistent with ethnobotanical studies in other Southeast Asian regions [32,33,34]. The Fabaceae family, in particular, was found to be the most diverse, with 12 species identified, reflecting its ecological adaptability and significance in both natural ecosystems and human livelihoods. Fabaceae species are frequently used in traditional agriculture, medicine, and nutrition, serving as important sources of protein, fiber, and medicinal compounds [35].

Similarly, the Euphorbiaceae and Rubiaceae families also stood out for their medicinal properties. Euphorbiaceae species, such as Jatropha gossypiifolia, are traditionally used for treating ailments such as wounds, inflammation, and digestive problems [36,37]. The Rubiaceae family, represented by species like Coffee arabica and Morinda citrifolia, provides a range of uses from medicinal to dietary applications, demonstrating their versatility and value in local health systems [38,39].

The richness of plant families in the study area is indicative of the complex relationships between local communities and their environment [40]. The diversity of plant species in Thailand plays a critical role in sustaining local economies and traditional practices [19,41,42]. The Lao Isan people’s comprehensive knowledge of plant species highlights their ability to sustainably manage local resources, utilizing a wide variety of plants for multiple purposes [25].

One of the key elements of this study was the UV analysis, which provides insight into the functional significance of plants within the community [27]. The UVs are an indicator of how frequently and widely a plant is used, and the plants with the highest UVs were also found to be those with the most significant roles in local cultural and medical practices [43]. Schleichera oleosa, Trigonostemon reidioides, and Vietnamosasa pusilla were identified as particularly important species with high UVs, reflecting their multipurpose utility in areas such as food, medicine, and ritual practices [20].

The high UV of Schleichera oleosa and Trigonostemon reidioides aligns with their use in traditional medicine to treat a wide variety of ailments, such as respiratory and digestive issues, which has been reported in other ethnobotanical studies [44,45]. The plants’ high UV suggests they are essential to local healthcare systems, where they fulfill critical roles as herbal remedies. The use of Vietnamosasa pusilla in both medicinal and cultural contexts underscores its importance beyond utilitarian needs, highlighting how plants are also integrated into the cultural identity of Indigenous communities [46].

Medium-use value plants, such as Careya arborea and Annona squamosa, are also integral to the community’s knowledge system, though their uses are often more selective. Careya arborea, for instance, is used in traditional rites and as a food source during certain seasons, while Annona squamosa is used medicinally and for its nutritional benefits [47,48]. These species are important not only for their medicinal uses but also for their seasonal availability, reinforcing the importance of indigenous ecological knowledge and seasonal plant use.

The presence of lower UV plants further illustrates the diversity of the Lao Isan ethnobotanical knowledge, where even less-utilized species contribute to the overall system of plant use. This mirrors findings from studies in other regions, where even species with limited use serve specialized roles in local ecosystems or cultural practices [49].

The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) is another critical metric used to understand the popularity and prominence of specific plants in local practices. High RFC values were observed for plants such as Trigonostemon reidioides and Vietnamosasa pusilla, both of which were consistently mentioned by informants. These plants are clearly central to the community’s plant knowledge, both in terms of their medicinal and ecological functions [45,50]. The high RFC of these species confirms that they play an indispensable role in the local healthcare system, being widely recognized and relied upon for the treatment of various illnesses [51]. Although the data collection spanned the entire year, we did not specifically analyze the seasonal variations in plant usage. However, it is important to acknowledge that some plant species may be used seasonally, which could influence the frequency of their citation. This is indirectly reflected in the Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) values, where species with more consistent year-round availability are likely to show higher RFC values compared to those that are used primarily during certain periods. While we did not specifically address the seasonal aspects, the overall RFC values still offer valuable insights into the general patterns of plant use within the community.

RFC is often associated with the perceived efficacy and cultural significance of plants within indigenous knowledge systems. The plants with high RFC values in this study are not only frequently used but also possess a high level of cultural and ecological relevance, reinforcing the argument that traditional knowledge systems are deeply intertwined with both health and environmental sustainability [52]. Conversely, plants with lower RFC values, such as Elephantopus scaber and Jatropha gossypiifolia, are mentioned less frequently, suggesting that their roles are more specialized or limited to certain individuals or contexts. Nonetheless, these plants may still play critical roles in specific rituals, medicinal practices, or agricultural settings, suggesting that even plants with low RFC values can have niche but important functions within the community [53].

One of the most significant aspects of the Lao Isan plant use is the diverse range of applications across different plant categories. As with many indigenous groups, plants are used for a broad spectrum of needs, including food, medicine, and various other utilitarian purposes. Of the 109 species identified, 58 were primarily used for food, highlighting the importance of plants in ensuring food security and dietary variety. The majority of these species were fruit-bearing trees, such as Durio zibethinus and Moringa oleifera, which are rich in nutrients and widely consumed in the Lao Isan diet. The consumption of these species aligns with studies showing that indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia rely heavily on local plants for nutrition, often incorporating a diverse range of edible plant species into their diets [11,17,19,20,25,33,41,42].

Medicinal plants played a prominent role, with 62 species identified for therapeutic uses. This reflects the community’s reliance on plant-based remedies for treating a wide variety of ailments, such as fever, digestive disorders, and skin conditions. The widespread use of plants like Andrographis paniculata and Plumbago zeylanica for their antimalarial and anti-inflammatory properties reinforces the growing recognition of traditional knowledge systems in addressing modern health challenges. Additionally, many of these plants are used as part of integrated healing systems, where medicinal practices are often intertwined with spiritual and cultural rituals [12,13,22,34,43,53]. However, the community’s reliance on traditional plants has been undergoing dynamic changes due to the increasing availability and popularization of modern medical facilities. While traditional plant-based remedies continue to play a significant role, particularly for common ailments and first-line treatments, there has been a gradual shift toward biomedical healthcare services for more serious or complex conditions. Younger generations, in particular, show a growing preference for hospital-based treatments, reflecting broader trends of modernization and globalization. Nevertheless, traditional knowledge remains resilient among older community members and in remote areas where access to hospitals and clinics may still be limited. This dynamic interaction between traditional practices and modern healthcare highlights a transitional phase, where both systems coexist and adapt in response to changing socio-economic conditions, accessibility, and perceptions of efficacy.

Beyond food and medicine, the Lao Isan people also use plants for a range of other purposes, such as crafting materials, firewood, and tools. Species such as Caryota mitis and Calamus rotang are used for making baskets and other woven items, while others, like Bamboo, are utilized in construction and agricultural tools. This diverse use of plants underscores the integrated relationship between local ecosystems and the cultural practices of the Lao Isan people. Similar patterns have been observed in other ethnobotanical studies, where local flora serves not just practical but also symbolic and cultural purposes [25,54].

The high Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) values for specific health categories, particularly for disorders related to the digestive system, respiratory conditions, and wound healing, reflect the shared knowledge within the community regarding the effectiveness of certain plants. The Fic value of 1 indicates complete agreement among informants, emphasizing the reliability and consistency of plant knowledge in the treatment of common ailments. This corroborates findings from other regions where traditional knowledge systems have been shown to possess a high degree of consensus, often developed over generations of practice [17,19].

Similarly, the Fidelity Level (FL) values also provide insight into the trust and dependence placed on specific plants. Plants such as Schleichera oleosa and Ehretia aspera, with FL values of 100%, are regarded as highly effective by all informants for treating particular ailments. These plants are seen as essential tools in the community’s healthcare system, contributing to the resilience of the community’s traditional medical knowledge. FL values also reveal that certain plants are more specialized in their use, with lower FL values indicating that some plants are less universally trusted for treating particular conditions [44].

To alleviate the loss of traditional plant knowledge, several strategies should be considered. Community education programs and workshops can engage both younger and older generations, ensuring that knowledge about the value and use of traditional plants is passed down. Additionally, documenting and sharing this knowledge through digital archives or printed materials can make it accessible for future generations. Encouraging intergenerational knowledge transfer, where elders directly teach younger members, can strengthen the continuity of traditional practices. Plant protection programs focusing on sustainable harvesting and legal protections for endangered species are also crucial. By combining these efforts, communities can preserve their traditional knowledge while ensuring sustainable use and conservation of plant resources.

5. Conclusions

This study documents the plant diversity, ethnobotanical knowledge, and traditional uses among the Lao Isan ethnic group in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province. We identified 109 species (48 families), with Fabaceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Rubiaceae as the most prevalent. Key species like Schleichera oleosa, Trigonostemon reidioides, and Vietnamosasa pusilla showed high Use Value (UV) and Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), underscoring their cultural and medicinal importance. Of 62 medicinal plants, a strong consensus (via Fic and FL) highlighted their efficacy for digestive, respiratory, and wound treatments. The findings stress the importance of fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer, promoting community-based education, and implementing sustainable harvesting and legal protection measures to conserve plant resources. Future research could focus on integrating traditional and modern healthcare systems, enhancing the conservation of valuable plant species, and supporting the continued relevance of traditional plant knowledge in a changing world, thereby safeguarding the cultural and ecological heritage of the Lao Isan community and similar groups across Southeast Asia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., S.S., T.B., A.J., S.A., K.K., K.C. and T.J.; methodology, P.S., S.S., T.B., A.J., S.A., K.K., K.C. and T.J.; software, T.B. and T.J.; validation, S.S., T.B. and T.J.; formal analysis, P.S., S.S., T.B., A.J., S.A., K.K., K.C. and T.J.; investigation, S.S. and T.J.; resources, S.S. and T.J.; data curation, S.S. and T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., T.B. and T.J.; writing—review and editing, P.S., S.S., T.B., A.J., S.A., K.K., K.C. and T.J.; visualization, T.B. and T.J.; supervision, P.S. and S.S.; project administration, P.S. and S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research project was financially supported by Mahasarakham University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the Lao Isan ethnic community in Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, for their warm welcome and essential contributions to this research. Our heartfelt thanks go to the local elders and knowledge keepers for generously sharing their ethnobotanical expertise. We also gratefully acknowledge the Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute for offering laboratory facilities and Mahasarakham University for their financial support throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schaal, B. Plants and people: Our shared history and future. Plants People Planet 2018, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidikia, F.; Lorigooini, Z.; Amini-Khoei, H. Medicinal plants: Past history and future perspective. J. HerbMed Pharmacol. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreau, A.; Ibarra, J.T.; Wyndham, F.S.; Rojas, A.; Kozak, R.A. How can we teach our children if we cannot access the forest? Generational change in Mapuche knowledge of wild edible plants in Andean temperate ecosystems of Chile. J. Ethnobiol. 2023, 36, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaoue, O.G.; Coe, M.A.; Bond, M.; Hart, G.; Seyler, B.C.; McMillen, H. Theories and Major Hypotheses in Ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 2017, 71, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Ma, Q.; Ye, L.; Piao, G. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules 2016, 21, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, A.; Motti, R.; Cartenì, F.; Magistris, A.D.; Gherardelli, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. Horticultural food plants in traditional herbal medicine in the Mediterranean Basin: A review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalu, G.; Nigussie, M.; Bezie, Y.; Fentahun, M.; Mulugeta, A.; Alemayehu, A.; Addisu, G. Use and conservation of medicinal plants by indigenous people of Gozamin Wereda, East Gojjam Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical approach. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 2973513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, R.; Pauli, G.; Soejarto, D. Factors in maintaining indigenous knowledge among ethnic communities of Manus Island. Econ. Bot. 2005, 59, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakes, V. The role of traditional knowledge in sustainable development. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 3, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet-Mir, L.; Riu-Bosoms, C.; González-Puente, M.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Reyes-García, V.; Molina, J.L. The transmission of home garden knowledge: Safeguarding biocultural diversity and enhancing social–ecological resilience. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punchay, K.; Inta, A.; Tiansawat, P.; Balslev, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P. Traditional knowledge of wild food plants of Thai Karen and Lawa (Thailand). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 1277–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phumthum, M.; Balslev, H. Use of medicinal plants among Thai ethnic groups: A comparison. Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuankaew, S.; Srithi, K.; Tiansawat, P.; Jampeetong, A.; Inta, A.; Wangpakapattanawong, P. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Tai Yai in Northern Thailand. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiadis, P. Ethnobotanical knowledge against the combined biodiversity, poverty, and climate crisis: A case study from a Karen community in Northern Thailand. People Nat. 2022, 4, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCargo, D.; Hongladarom, K. Contesting Isan-ness: Discourses of politics and identity in Northeast Thailand. Asian Ethn. 2004, 5, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heis, A. The Alternative Agriculture Network Isan and Its Struggle for Food Sovereignty—A Food Regime Perspective of Agricultural Relations of Production in Northeast Thailand. Austrian J. South-East Asian Stud. 2015, 8, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Rakarcha, S.; Boonma, T.; Jitpromma, T.; Sonthongphithak, P.; Ragsasilp, A.; Souladeth, P. Diversity and local uses of the Convolvulaceae family in Udon Thani Province, Thailand, with notes on its potential horticultural significance. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, J.; Garzoli, J.; Kamnuansilpa, P.; Lefferts, L.; Mitchell, J.; Songkünnatham, P. The Thai Lao—Thailand’s largest un-recognized transboundary national ethnicity. Nations Nat. 2019, 25, 1131–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Hein, K.Z.; Appamaraka, S.; Maknoi, C.; Souladeth, P.; Koompoot, K.; Sonthongphithak, P.; Boonma, T.; Jitpromma, T. Diversity, Ethnobotany, and Horticultural Potential of Local Vegetables in Chai Chumphol Temple Community Market, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisor, N.; Prathepha, P.; Saensouk, S. Ethnobotanical study and utilization of plants in Khok Nhong Phok forest, Kosum Phisai District, Northeastern Thailand. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 4336–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, T.D.; Dao, Q.T.; Nguyen, H.V. Planting seeds for the future: Challenges and solutions for Cham traditional medicine in the context of Vietnam’s rapid modernization. Socioling. Stud. 2025, 18, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona-García, C.; Blancas, J.; Beltrán-Rodríguez, L.; López Binnqüist, C.; Colín Bahena, H.; Moreno-Calles, A.I.; Sierra-Huelsz, J.A.; López-Medellín, X. How does urbanization affect perceptions and traditional knowledge of medicinal plants? J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beery, T.; Stahl Olafsson, A.; Gentin, S.; Maurer, M.; Stålhammar, S.; Albert, C.; Bieling, C.; Buijs, A.; Fagerholm, N.; Garcia-Martin, M.; et al. Disconnection from nature: Expanding our understanding of human–nature relations. People Nat. 2023, 5, 470–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapane, O.L.; Chanza, N.; Musakwa, W. Transmission of indigenous knowledge systems under changing landscapes within the Vhavenda community, South Africa. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 161, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamngon, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensou, P.; Junsongduang, A. Ethnobotanical of the Lao Isan Ethnic Group in Pho Chai District, Roi Et Province, Northeastern Thailand. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 8, 6152–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant of the World Online, Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Phillips, O.; Gentry, A.H.; Reynel, C.; Wilkin, P.; Galvez-Durand, B.C. Quantitative ethnobotany and Amazonian conservation. Conserv. Biol. 1994, 8, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural importance indices: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.; Yaniv, Z.; Dafni, A.; Palewitch, D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 16, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria Version 16. 2024. Available online: https://nc.iucnredlist.org/redlist/content/attachment_files/RedListGuidelines.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Lee, C.; Kim, S.-Y.; Eum, S.; Paik, J.-H.; Bach, T.T.; Darshetkar, A.M.; Choudhary, R.K.; Hai, D.V.; Quang, B.H.; Thanh, N.T.; et al. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants used by local Van Kieu ethnic people of Bac Huong Hoa nature reserve, Vietnam. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 231, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.; Fujikawa, K.; Moe, A.Z.; Uchiyama, H. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants with special emphasis on medicinal uses in Southern Shan State, Myanmar. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V.; Khun, S.; Sun, L.; Tan, S.; Kim, S.; Chhavarath, D.; Sena, C. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used for the treatment of headache, low back, and joint pains in three provinces in Cambodia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 4, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alrhmoun, M.; Sulaiman, N.; Pieroni, A. Phylogenetic perspectives and ethnobotanical insights on wild edible plants of the Mediterranean, Middle East, and North Africa. Foods 2025, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, I.; Rizwan, K.; Saber, F.R.; Munir, S.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Otero, P. Ethnotraditional uses and potential industrial and nutritional applications of secondary metabolites of genus Jatropha L. (Euphorbiaceae): A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F.; Sinan, K.I.; Ak, G.; Etienne, O.K.; Sharmeen, J.B.; Brunetti, L.; Leone, S.; Di Simone, S.C.; Recinella, L.; et al. Chemical composition and biological properties of two Jatropha species: Different parts and different extraction methods. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruse, G.; Jîjie, A.-R.; Moacă, E.-A.; Pătrașcu, D.; Ardelean, F.; Jojic, A.-A.; Ardelean, S.; Tchiakpe-Antal, D.-S. Coffea arabica: An emerging active ingredient in dermato-cosmetic applications. Pharmaceutics 2025, 18, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Castelazo, F.; Soria-Jasso, L.E.; Torre-Villalvazo, I.; Cariño-Cortés, R.; Muñoz-Pérez, V.M.; Ortiz, M.I.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Plants of the Rubiaceae family with effect on metabolic syndrome: Constituents, pharmacology, and molecular targets. Plants 2023, 12, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Cao, M. Relationships between plant species richness and terrain in middle sub-tropical Eastern China. Forests 2017, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengsanga, T.; Kaewthani, S.; Rattana, T. Plant diversity, traditional utilization, and community-based conservation of the small-scale Nong Sakae Community Forest in Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand. Forest Soc. 2024, 8, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitpromma, T.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Boonma, T. Diversity, traditional uses, economic values, and conservation status of Zingiberaceae in Kalasin Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, C.S.; Meve, U.; Alejandro, G.J.D. Ethnobotany and diversity of medicinal plants used among rural communities in Mina, Iloilo, Philippines: A quantitative study. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 2023, 16, 96–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.K.; Sinha, A.; Das, B.; Dhakar, M.K.; Shinde, R.; Chakrabarti, A.; Yadav, V.K.; Bhatt, B.P. Kusum (Schleichera oleosa (Lour.) Oken): A potential multipurpose tree species, its future perspective and the way forward. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, A. Trigonostemon Species in South China: Insights on its chemical constituents towards pharmacological applications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 281, 114504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyong, S.; Pongamornkul, W.; Panyadee, P.; Inta, A. Uncovering the ethnobotanical importance of community forests in Chai Nat Province, Central Thailand. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 2052–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambardar, N.; Aeri, V. A better understanding of traditional uses of Careya arborea Roxb.: Phytochemical and pharmacological review. TANG 2013, 3, 28–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safira, A.; Widayani, P.; An-Najaaty, D.; Rani, C.; Septiani, M.; Putra, Y.; Solikhah, T.; Khairullah, A.; Raharjo, H.M. A review of an important plant: Annona squamosa Leaf. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewsangsai, S.; Panyadee, P.; Panya, A.; Pandith, H.; Wangpakapattanawong, P.; Balslev, H.; Inta, A. Diversity of plant colorant species in a biodiversity hotspot in Northern Thailand. Diversity 2024, 16, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongleang, S.; Premjet, D.; Premjet, S. Physicochemical pretreatment of Vietnamosasa pusilla for Bioethanol and Xylitol production. Polymers 2023, 15, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, Y.; Lulekal, E.; Warkineh, B. Human-forest interaction of useful plants in the Wof Ayzurish Forest, North Showa Zone, Ethiopia: Cultural significance index, conservation, and threats. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2025, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, B.; Asiala, C.; Fernández Fernández, D. Relative importance and knowledge distribution of medicinal plants in a Kichwa community in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2017, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.; Ray, A. Medicinal practices of sacred natural site: A socio-religious approach for successful implementation of primary healthcare services. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 20, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapaya, R.J.; Shopo, B.; Maroyi, A. Traditional uses of plants in Gokwe South District, Zimbabwe: Construction material, tools, crafts, fuel wood, religious ceremonies and leafy vegetables. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2022, 24, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).